Introduction

One of the most surprising and infrequently discussed policy shifts in Japanese domestic politics took place during the long Prime Ministership of the late Shinzo Abe. Prime Minister Abe was beloved by the far right, and he had been a consistent opponent of immigration to Japan. Abe’s opposition to immigration was such that, in 2015, when a reporter asked him whether Japan would consider joining peer countries including Germany in admitting refugees from Syria and Iraq in the wake of the Syrian civil war, he replied “It is an issue of demography. I would say that before accepting immigrants or refugees, we need to have more activities by women, elderly people and we must raise our birth rate. There are many things that we should do before accepting immigrants” (Reuters 2015).

Within three years, however, Abe’s policy stance changed significantly. In December 2018, the Japanese Diet passed a law which established 14 new visa categories for foreign manual laborers (including construction workers, agricultural workers, and caregivers). This was the first time that foreign manual laborers would be admitted into Japan as laborers (rather than as technical, coethnics, or students), and it thus marked a substantial break with the way that Japan had treated immigration (especially immigration of manual laborers) in the past.Footnote 1 Shortly after the law passed, Abe issued a Cabinet Understanding that Japan would aim to have 345,150 foreign residents under these new visa categories in five years (Yomiuri Shimbun Reference Shimbun2018).

Was this change particular to Prime Minister Abe, or did it reflect a more widespread trend in Japanese politics? In this article, we answer this question by examining the changing views of Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) politicians and political candidates on the issue of immigration in recent years, as Japan’s labor shortages have intensified. We focus on the LDP because that party has controlled Japan since its creation in 1955 with only a few relatively short-lived exceptions (1993–1994 and 2009–2012), and because the LDP has been, up until recently, fairly opposed to immigration.

Most scholarship on the politics of immigration in Japan has focused on the role of bureaucratic rivalry (Kalicki Reference Kalicki2019), local government (Aiden Reference Aiden2011; Milly Reference Milly2014; Tsuda Reference Tsuda2006), international pressure (Gurowitz Reference Gurowitz1999), civil society and advocacy groups (Chiavacci Reference Chiavacci, Chiavacci, Grano and Obinger2020; Kremers Reference Kremers2014; Chung Reference Chung2010), civic legacies (Chung Reference Chung2020), fundamental beliefs about the appropriate role of foreigners (Skrentny, Gell-Redman, and Lee Reference Skrentny, Gell-Redman and Lee2012), and/or public opinion (Green Reference Green2017; Hamada Reference Hamada2008; Kage, Rosenbluth, and Tanaka Reference Kage, Rosenbluth and Tanaka2022; Yin Reference Yin2023; Otsuki Reference Otsuki2007) on immigration policy. Much less has been said about the role of the Diet in immigration policymaking.Footnote 2 This article proceeds in two parts. First, we examine the scholarship on the comparative politics of immigration control, focusing in particular on position taking by politicians and political candidates. Second, we examine the changing nature of position taking on immigration policy, particularly among LDP candidates to Japan’s House of Representatives, between 2009 and 2021. We limit the analysis period to 2021 since the data on candidates’ opinions for the most recent 2024 election have not yet been released.

In this analysis we ultimately identify three major trends in the Diet candidate opinion on foreign labor. First, Diet candidates, and LDP Diet candidates in particular, have become much more supportive of foreign labor. In the case of the LDP, this is due to both retirement of anti-foreign labor candidates and the fact that new and non-retirement candidates have moved their positions. Second, in the case of the LDP, candidates from rural areas have become even more pro-foreign labor than candidates from urban areas. This likely reflects the dire labor shortages in rural Japan. Third, despite the increasing number of political candidates in support of foreign labor, we have some reason to believe that the real number of political candidates in support of foreign labor is even higher than those that will publicly admit it—that is, there are likely some “shy foreign labor supporters” (Strausz Reference Strausz and Strausz2025) among candidates in recent elections.

The comparative politics of immigration control in Japan and beyond

Scholars have consistently shown that legislators are influenced by the demographic characteristics of their constituencies. Research on policy-making in the United States Congress has found that members are more likely to defer to their geographic constituency in policy-making when policies are likely to have a disproportionate impact—affecting some parts of the country differently than others—or when the issue is perceived as potentially salient to the public (Arnold Reference Arnold1992; Kingdon Reference Kingdon1989; Lee Reference Lee, Quirk and Binder2005; Sinclair Reference Sinclair1989). In the context of immigration to the United States, Gonzalez and Kamdar (Reference Gonzalez and Kamdar2000) have found that representatives from districts with more foreign residents were more likely to support immigration restrictions. However, Newman (Reference Newman2013) finds that growth in Hispanic populations in areas that had previously had small Hispanic population is associated with increases public opposition to immigration, while such growth in areas that had already had larger Hispanic populations is associated with decreases in public opposition to immigration.

In short, the US example suggests that incentives faced by politicians and political candidates to take positions on immigration vary with both the static and dynamic features of the demographic characteristics of their districts. The comparative politics of immigration have also been changing rapidly. Before the emergence of Donald Trump, Brexit, and other vocal anti-immigrant actors and forces throughout the advanced industrialized world, Freeman (Reference Freeman1995) famously argued that liberal democracies are converging on expansionist and inclusive policies because the benefits of immigration are concentrated—felt by, among other actors, labor intensive businesses—while the costs are diffuse. This means that “the interest group system around immigration issues is dominated by those groups supportive of larger intakes and, by implication, the organized public is more favorable to immigration than the unorganized public” (Freeman Reference Freeman1995, 885).

Freeman’s model assumed the existence of “strong antipopulist norms that dictate that politicians should not seek to exploit racial, ethnic, or immigration-related fears to win votes” (Freeman Reference Freeman1995, 885). However, these norms have weakened in many liberal democracies. We can see this change in the electoral successes of xenophobic populist forces in countries including the United States, the United Kingdom, France, Germany, and Denmark. The case of Japan, however, is a bit different. Unlike many other liberal democracies, Japan has largely avoided large-scale immigration (Strausz Reference Strausz2019) despite labor shortages and a rapidly aging and declining population.Footnote 3 Moreover, and perhaps relatedly, the Japanese public is not particularly opposed to foreign labor. Japanese are more likely to perceive the economic benefits of immigration and less likely to agree that “culture is harmed by immigrants” than are residents of all but one of the 20 other countries and regions polled in the Comparative Study of Electoral Systems (CSES) Module 5 (Matsubayashi and Yamatani Reference Matsubayashi, Yamatani, Anderson and Turgeon2022, 249).Footnote 4

On the economic side, Japan has faced periods of intense labor shortages since the 1970s (see Figure 1 for an illustration of these trends). Demographically, Japan is facing a rapidly aging and declining population. While Japan’s birthrate had dipped below the replacement level of 2.1 children per women in the 1970s and had continued to fall, for many years Japanese government demographers continued to predict that the birthrate would rebound. This official demographic optimism finally ended in 2002, when government demographers “accepted that Japanese women had fundamentally changed their behavior,” and projected the birthrate to stabilize at 1.4 children per woman (Schoppa Reference Schoppa2006, 152).

Figure 1. Job seeker’s ratio in Japan, 1963–2022.

Unlike many Western countries, where anti-immigration political forces seem to be on the rise, Japan has made some moves in recent years to expand immigration. In response to the labor shortages of the 1980s, Japan revised the Immigration Control and Refugee Recognition Act to formalize “side doors” such as the long-term residency visa (for those with Japanese ancestry or those raising children with Japanese ancestry) and the trainee visa (which was later expanded into the technical internship program). More recently, the labor shortages of the 2010s led the Abe government to back a bill that created a new visa category called the “specified-skilled visa” in late 2018. This visa category was the first time in postwar Japan that manual laborers (in fields such as construction and agriculture) would be permitted to enter Japan as “laborers” rather than as trainees, coethnics, or students, or using some other kind of “side door.”

The Abe administration’s advocacy of this legal change was surprising because Abe had been clear about his opposition to immigration. Despite this opposition, it appears that Abe’s Chief Cabinet Secretary and successor as Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga persuaded him that the law was not truly an immigration policy and would help address labor shortages (Harris Reference Harris2020, 316). Consequently, Abe ended up supporting it while regularly emphasizing that it was not an immigration policy because most of those coming to Japan would have to leave after a few years. Additionally, most would not be permitted to be accompanied by non-working spouses and other non-working dependents (Strausz Reference Strausz, Schubert, Plümmer and Bayok2021).

Unlike Western Europe and the United States, Japan has not yet seen the emergence of a xenophobic populism in mainstream politics.Footnote 5 This is possibly because, despite the reforms of the late 1980s and 2018, the percent of Japan’s population that is composed of immigrants remains small compared to other advanced industrialized countries. Moreover, free trade has not hurt the blue-collar work force in Japan as much as it has in other advanced industrialized countries (Strausz Reference Strausz2019, 143).

While xenophobic populism has not entered mainstream politics in Japan, there are organized groups of far-right nationalists in Japan that define Japanese identity primarily in ethnic, rather than in civic, terms, and regularly argue that Japan belongs only to those with Japanese ethnicity (Smith Reference Smith2018).Footnote 6 For now, these groups focus much of their invective on Korean residents of Japan (most of whom are not labor migrants but are the descendants of those who came, or were forcibly brought, to Japan between 1910 and 1945, when Japan had colonized Korea). However, should Japan admit large number of labor migrants, it is certainly possible to imagine these groups shifting the focus of their ire to these new migrant populations instead.

Thus, Japanese politicians and political candidates find themselves in a difficult position with respect to immigration. On one hand, they are aware that Japan is facing intense economic and demographic pressures to admit immigrants. On the other hand, they fear backlash from organized xenophobic groups should they be seen as too “pro-immigration.” Moreover, they have reason to fear that, even though xenophobes are a minority among the Japanese public, they appear willing to be “one issue voters” on immigration in the way that immigration supporters do not (Asano, Nissen, and Strausz Reference Asano, Nissen and Strausz2019; Kustov Reference Kustov2023). In short, politicians face a dilemma where although voting to expand immigration might be in the economic best interest of their district, acting to expand immigration might nevertheless hurt their chances of being reelected.

Moreover, politicians from different kinds of districts are facing distinct kinds of challenges. The politics of urban and rural districts are notably different, and in response to this difference, party politics in Japan have developed what Scheiner has called

two parallel party systems—one rural and LDP dominant, one urban and competitive. Moreover, Japan’s internationally competitive businesses have become increasingly uncomfortable with the clientelism that dominates in rural Japan. (Scheiner Reference Scheiner2006, 228)

Immigration is an issue that is important to both of these kinds of districts. Internationally competitive businesses in urban districts are often interested in the kinds of immigration policies that allow them to recruit international talent for their business, but businesses in rural districts (including, but not limited to, the agricultural sector) are also facing intense labor shortages. As MacLachlan and Shimizu (Reference Maclachlan and Shimizu2016, 447) note, “while 23% of the population in 2010 was 65 or older, the corresponding rate for commercial farmers was a staggering 61.6%—nearly double that of 1990. By 2014, the figure for commercial farmers had risen to 63.6%.”

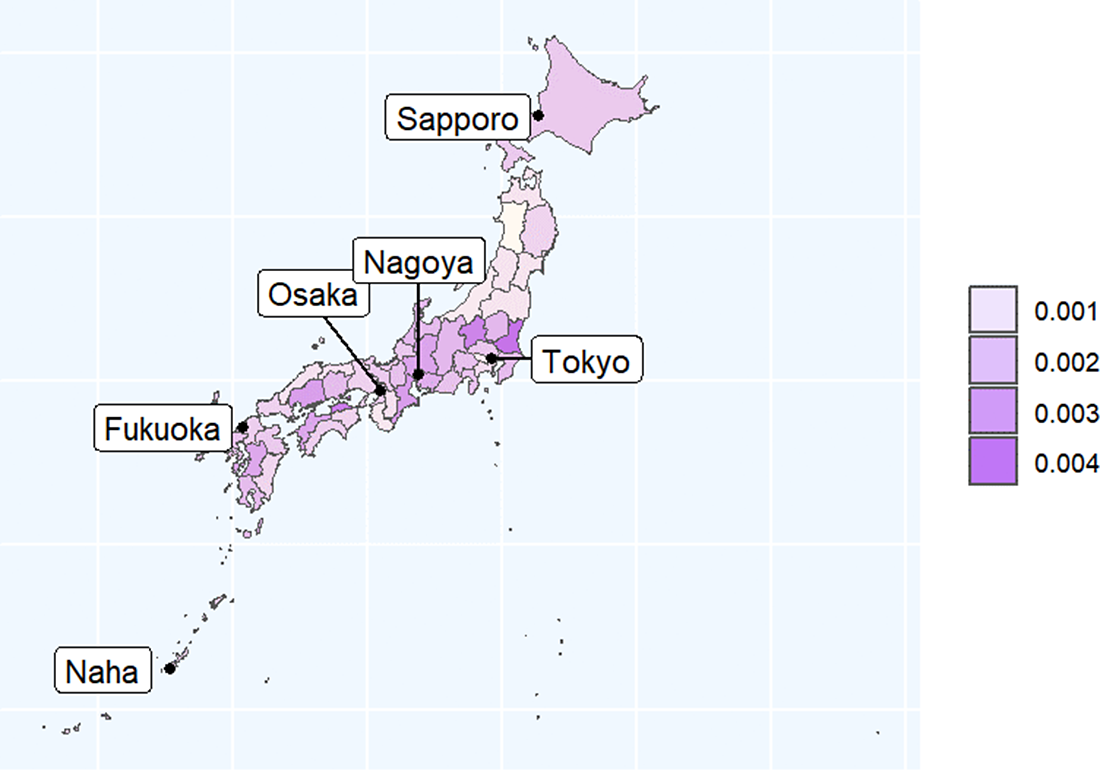

In the face of these frankly shocking demographic trends, rural Japan has increasingly turned to foreign labor. This is clear when looking at Figure 2, which depicts the prefectures where holders of “specified skilled visas” (the visa category for manual laborers that was established in 2018, discussed above) are located. Note that the prefectures and metropolitan areas that house Japan’s biggest cities have relatively small percentages of their populations composed of specified skilled visa holders. Tokyo, Kanagawa, and Osaka—three of Japan’s most populous prefectures—are all below the median in the proportion of population composed of specified skilled visa holders (the 3rd, 12th, and 18th smallest, respectively).

Politicians from districts with more and fewer candidates also might face difference sets of incentives with respect to immigration. In a study of municipal governments in the Osaka area, Sunahara, Hata, and Nishimura (Reference Sunahara, Hata, Nishimura, Oguma and Higuchi2020) find that LDP politicians that face more competition from Ishin no Kai and other LDP candidates are more likely to use words in their parliamentary speeches such as “Japanese,” “foreigner,” “welfare” and “human rights.” Sunahara, Hata, and Nishimura suggest that this could be because these politicians want to compete with conservative rivals on the immigration/human rights dimension that their rivals are invoking. While local elections in Osaka are based on SNTV rules, and thus the district magnitudes are much larger than national elections in Japan (with SMDs), it is possible that politicians from rural districts in safer seats are less likely to face many rivals than are politicians in urban districts with more competition.

The politics of immigration control in urban and rural Japan

Have these trends in rural Japan been accompanied by corresponding trends in politicians’ and political candidates’ opinions? To address this question, we first look at all candidates in lower-house elections in the last 15 years (since 2009). To measure candidates’ opinions on the foreign worker issue, we employ the UTokyo-Asahi Survey (UTAS), a joint project of Masaki Taniguchi of the University of Tokyo and the Asahi Shimbun, a national newspaper. The UTAS project surveys candidates at each national election and achieves very high response rates.Footnote 7 One of the questions asked is whether they agree with the following statement: “We should promote the acceptance of foreign workers.” The candidates are asked to answer by selecting one of the five following options: agree, somewhat agree, not sure, somewhat disagree, and disagree.

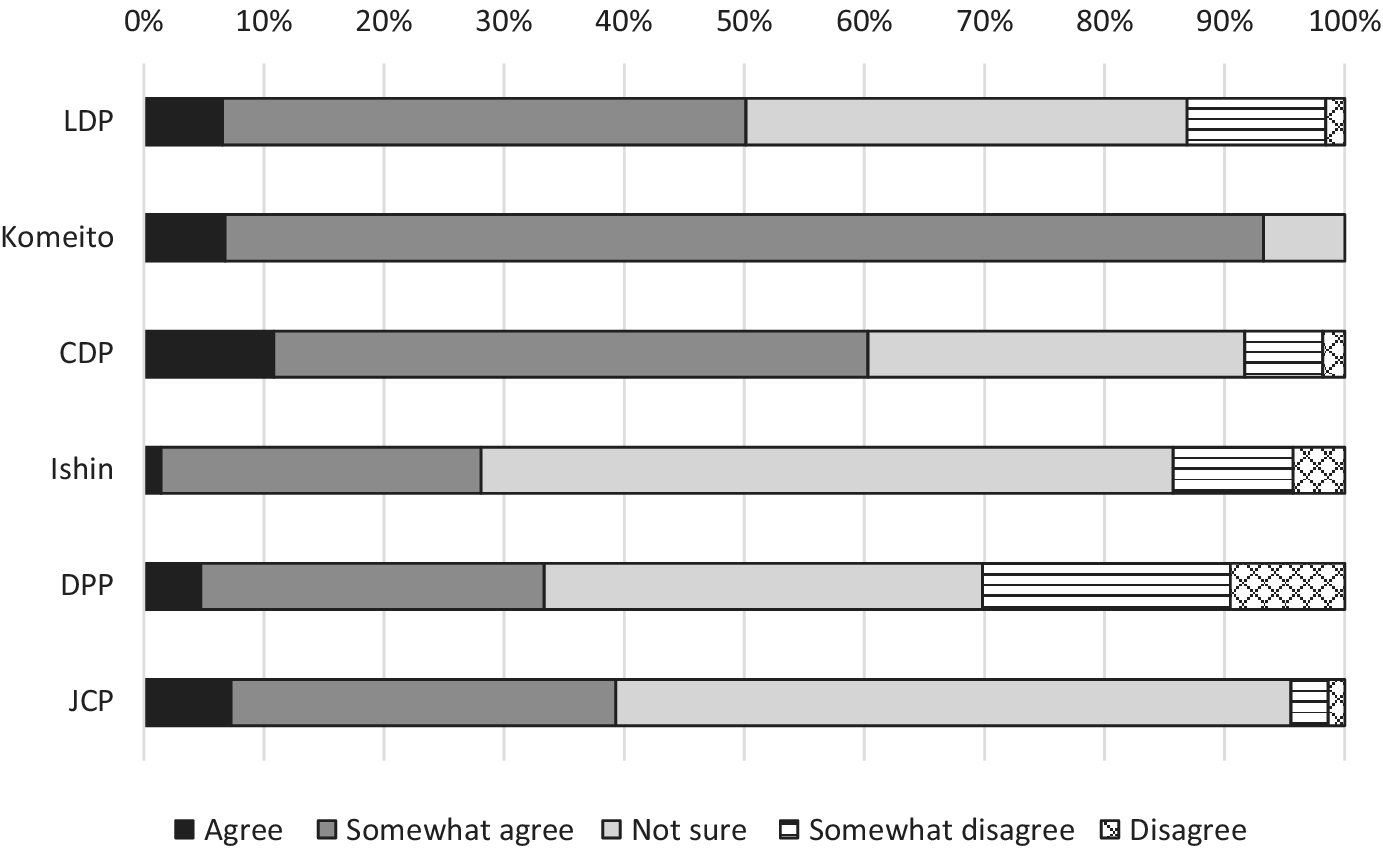

Before proceeding to a detailed analysis of LDP candidates’ opinions, let us first look at how LDP candidates’ opinions are different from other parties’ candidates. Figure 3 shows the distribution of the opinions of candidates of the six largest parties in the 2024 House of Representatives (1022 valid responses) and 2022 House of Councilors (273 valid responses) elections. The graph reveals that the opinions of LDP candidates are somewhat typical; they are less supportive of foreign workers’ acceptance than Komeito and the Constitutional Democratic Party but more supportive than Ishin and the Japanese Communist Party.

Figure 3. Candidates’ Opinions on Foreign Worker Intake, Broken Down by Parties.

Note: LDP=Liberal Democratic Party; CDP=Constitutional Democratic Party; Ishin=Nippon Ishin No Kai or Japan Innovation Party; DPP=Democratic Party for the People; and JCP=Japanese Communist Party.

Among the LDP candidates, as shown in Figure 3, about half of the candidates either agree or somewhat agree with the promotion of the acceptance of foreign workers. More specifically, 48.1 percent of the LDP’s House of Representatives candidates in 2024 and 58.9 percent of the House of Councilors candidates in 2022 either agree or somewhat agree.

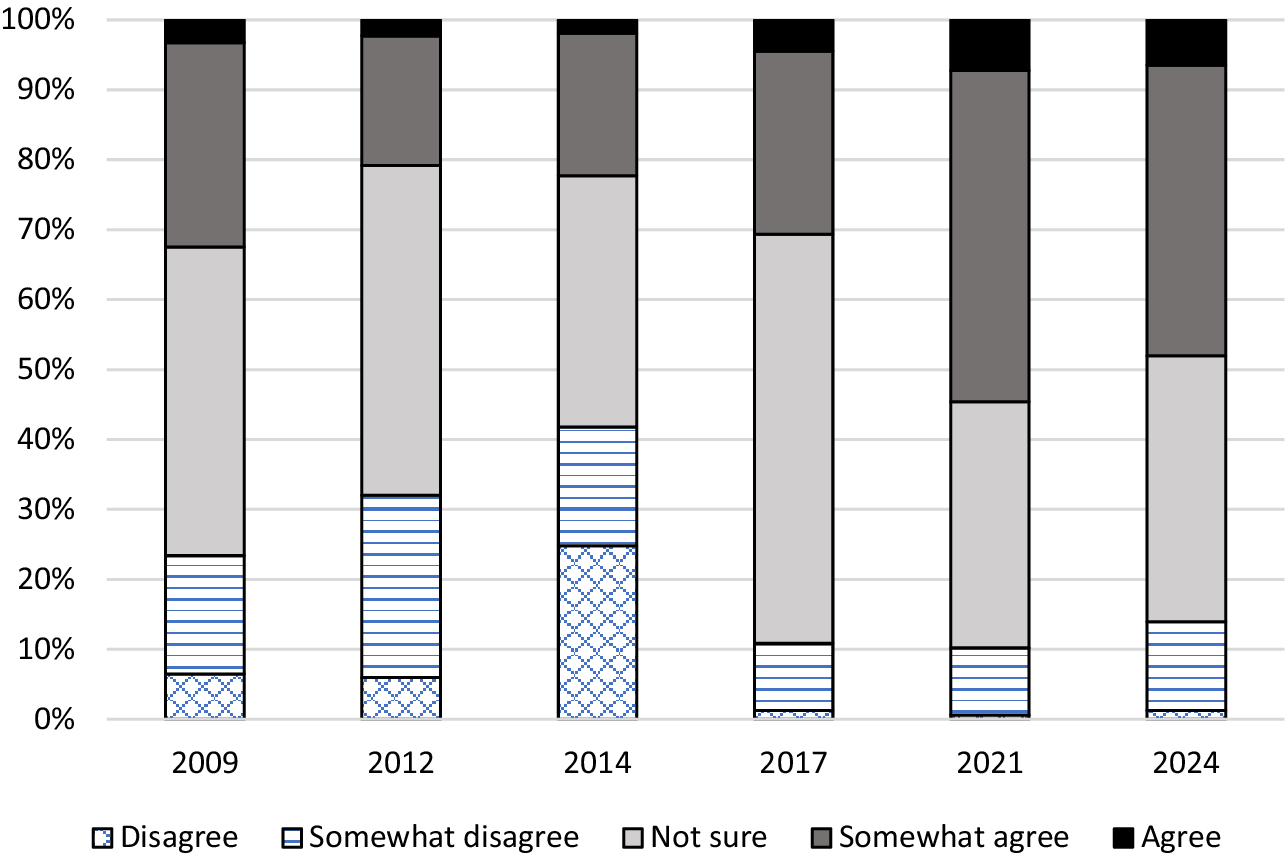

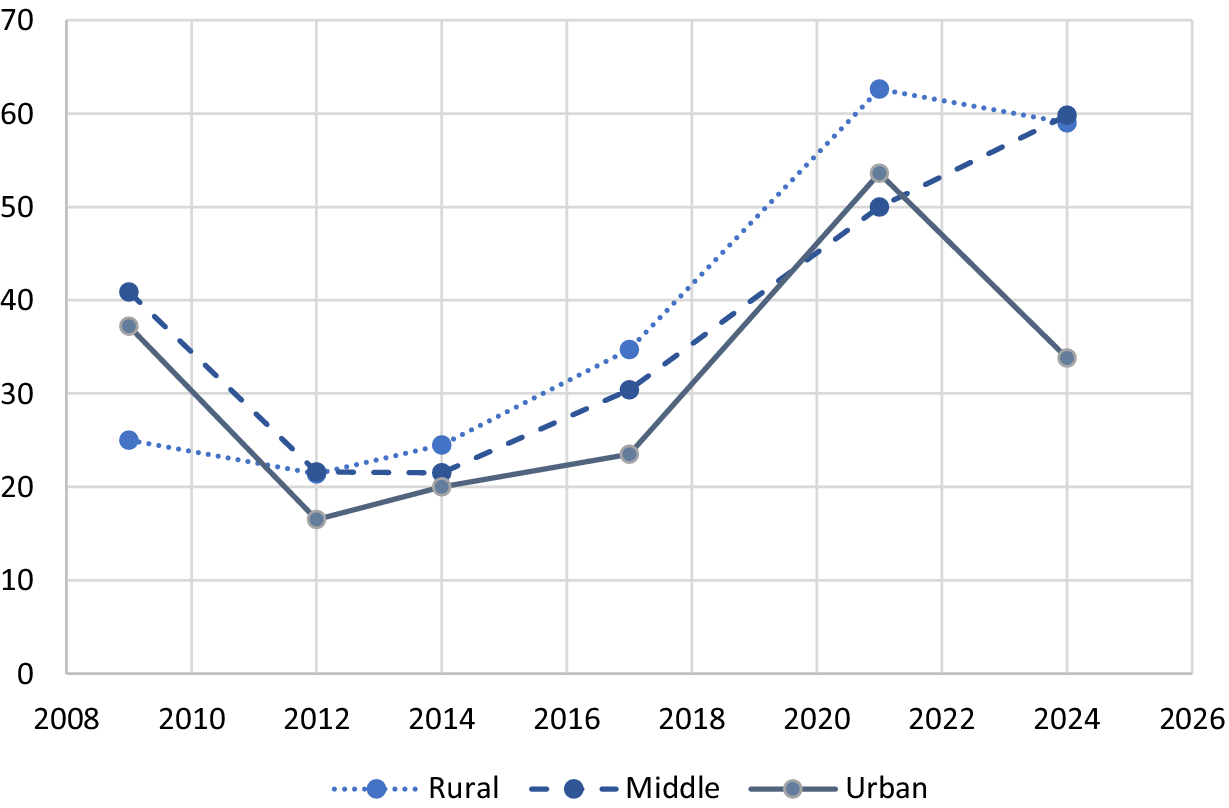

How have LDP candidates changed their positions over time? To address this, we look at candidates for the House of Representatives in every election since 2009, the first year in which a foreign labor question was included in the UTAS survey. As is clear in Figure 4, support for increased foreign workers dropped while the party was out of power between 2009 and 2012, which is consistent with the narrative provided by Nakakita and Owada (Reference Nakakita, Owada, Oguma and Higuchi2020) that the LDP made a rightward move then to establish its policy-level identity. The support then went up and surpassed 50% in 2021 for the first time, before dropping somewhat in 2024. In the House of Councilors, the first year that the majority of LDP candidates supported expanding foreign labor was 2019 (Strausz Reference Strausz and Strausz2025). These 2019 and 2021 elections were the first elections in each house after the December 2018 Abe-led creation of the Specified Skilled Visa.

Figure 4. LDP House of Representatives candidates’ positions on foreign worker.

Note: The distribution of the candidates’ opinions is shown in percentages at each election.

In the case of the House of Councilors, LDP Dietmembers who were not up for election in 2019 were more likely to support increasing foreign labor than were those that were up for election. Moreover, there was a correlation between the percentage of candidates that did not take a position on foreign labor in a given prefecture and the overall average score that candidates from a prefecture gave to the foreign labor question, with candidates from prefectures with few other candidates taking a position on foreign labor being more likely to oppose foreign labor. Together, these two trends suggest that there are likely what Strausz (Reference Strausz and Strausz2025) calls “shy foreign labor supporters”—candidates that support foreign labor but are afraid of a voter backlash if they take that position publicly. In other words, candidates are reluctant to talk about foreign labor if they don’t feel like they have to (because other candidates in their prefecture are talking about foreign labor, and/or because they are up for election and want to seem transparent to their voters), but once they feel compelled to talk about foreign labor they are more likely than not to support foreign labor.

Unlike the House of Councilors, all House of Representative seats are contested in every election, so we are not able to compare those candidates that are up for election with those that are not. However, in the 2017 House of Representative election there was a similar result to what we saw when looking at candidates from the same prefecture in the 2019 House of Councilors election. Candidates from the same prefecture were less likely to support foreign labor when a larger percentage of candidates answered that they neither agree nor disagree on foreign labor (Strausz Reference Strausz, Pekkanen, Reed, Scheiner and Smith2018). There is a similar pattern when looking at the 2021 House of Representatives Election.

Aside from the presence or absence of “shy foreign labor supporters,” what explains the movement of LDP candidates toward supporting foreign labor? Did this happen because older candidates retired and the younger candidates that replaced them brought pro-foreign labor stances, or because the same candidates changed their positions during their careers? The answer appears to be “both.”

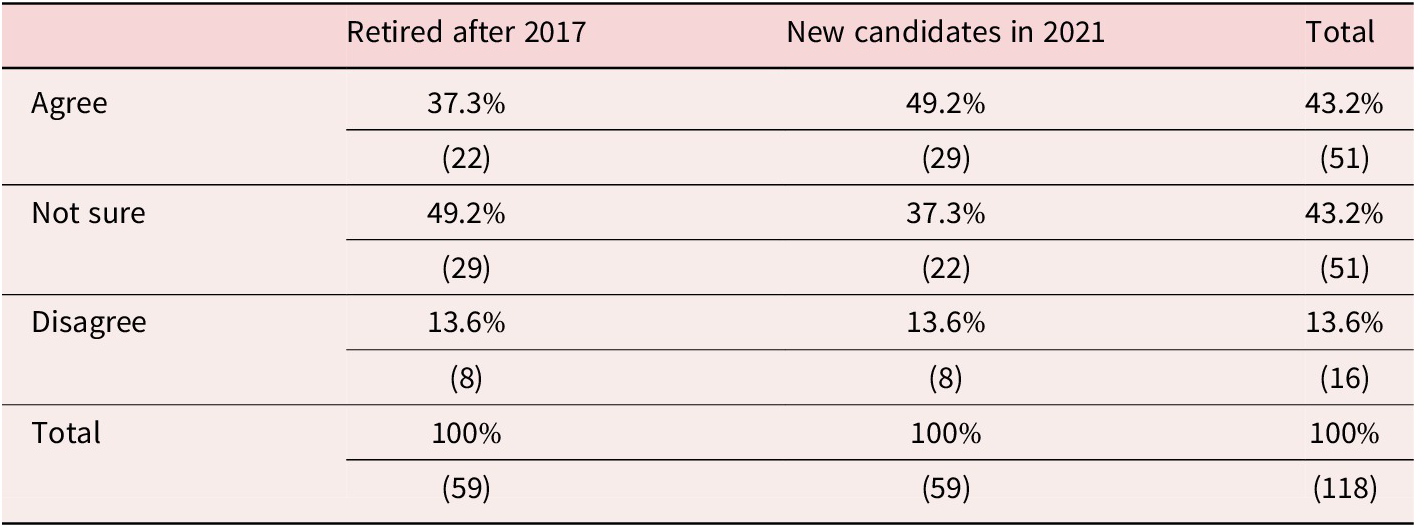

Let us first examine if the change in candidate lineups due to retirements and new entries contributed to the increased support for foreign labor among LDP candidates. Table 1 shows the opinions of the LDP candidates who retired after 2017 and the new candidates in 2021. We focus on this 2017–2021 period because it was when the largest change in LDP candidates’ opinions took place (see Figure 4). Out of the 335 LDP candidates who ran in 2017, 70 did not run in 2021. Among them, 11 did not answer the foreign worker question. Among the remaining 59 candidates, 37.3 percent support expanding foreign workers.

Table 1. Positions on foreign workers among the LDP House of Representatives candidates who retired after 2017 and the new candidates in 2021

Note: The numbers in parentheses are raw numbers. “Agree” and “Disagree” include those who somewhat agree and disagree, respectively.

The next column of the Table shows the opinions of the new LDP candidates in 2021. Out of the 338 LDP candidates who ran in the 2021 election, 73 were new candidates who did not run in the previous 2017 election, 59 of whom answered the foreign worker question. The percentage of pro-foreign worker candidates among them is 49.2 percent—much higher than the percentage among the retired candidates in 2017. Of those new candidates in 2021, the support for foreign labor was particularly higher (57.2 percent) among the ones who only ran in the proportional representation (PR) tier of the election (not shown in the Table). This possibly means that the LDP’s leadership in 2021, with Fumio Kishida as the newly elected party leader, had a preference to nominate such candidates in the election because the lineup of PR-only candidates more strongly reflects the party headquarters’ preferences than the candidates in the single-member district (SMD) tier who typically have strong local ties to their districts.

Now let us shift our attention to the candidates who ran in both 2017 and 2021. There were 265 such candidates, 239 of whom answered the foreign worker question in both years. How did their opinions change from 2017 to 2021? Table 2 is a cross-tabulation that shows those candidates’ opinions in both years. The Table shows that there was a clear trend in the candidates’ opinions moving toward the direction of supporting foreign labor expansion. About a half of those who answered “not sure” in 2017 and about a third of those who disagreed or somewhat disagreed in 2017 moved to the “agree or somewhat disagree” category in 2021.

Table 2. Positions on foreign workers among the LDP House of Representatives candidates who ran in both 2017 and 2021

Note: The numbers in parentheses are raw numbers. “Agree” and “Disagree” include those who somewhat agree and disagree, respectively.

As we noted above, the urbanization of an electoral district, the percentage of foreign residents in an electoral district, and the change in percentage of foreign residents in an electoral district are all factors which other studies have suggested have a big influence on the candidate positions and candidate strategy. How have changes in those factors influenced the nature of LDP candidates in electoral districts since 2009? This is a particularly interesting and important question as the demographic gap between the rural and urban districts continues to grow.

Figure 5 shows the trends in the percentage of LDP candidates in SMDs since 2009 who either agreed or somewhat agreed with foreign worker expansion, broken down by the levels of urbanization. Urbanization is measured by the percentage of residents who reside in census-designated “densely inhabited districts” (DID), which is a common urbanization indicator in the study of Japanese elections.Footnote 8 In the graph, “Urban” refers to the candidates in SMDs where DID% was higher than 90, “Middle” is the candidates in SMDs of 50 to 90 DID%, and “Rural” is the candidates in SMDs with less than 50 DID%. The three categories include roughly the same numbers of SMDs. Overall, the candidates’ support for foreign labor dropped from 2009 to 2012 but has since been increasing. Urban candidates in 2024 show an anomalous pattern which may or may not reflect the fact that many LDP candidates in urban districts had competing candidates from Sanseito, a new far-right party. It is striking that rural candidates had the lowest levels of support in 2009, but the pattern has flipped since. Rural LDP candidates have shown the highest levels of support from 2014 to 2021. Something seems to have significantly changed in rural Japan and rural LDP candidates after 2009.

Figure 5. Percentage of LDP candidates in SMDs who agreed or somewhat agreed with foreign worker expansion, broken down by the levels of urbanization.

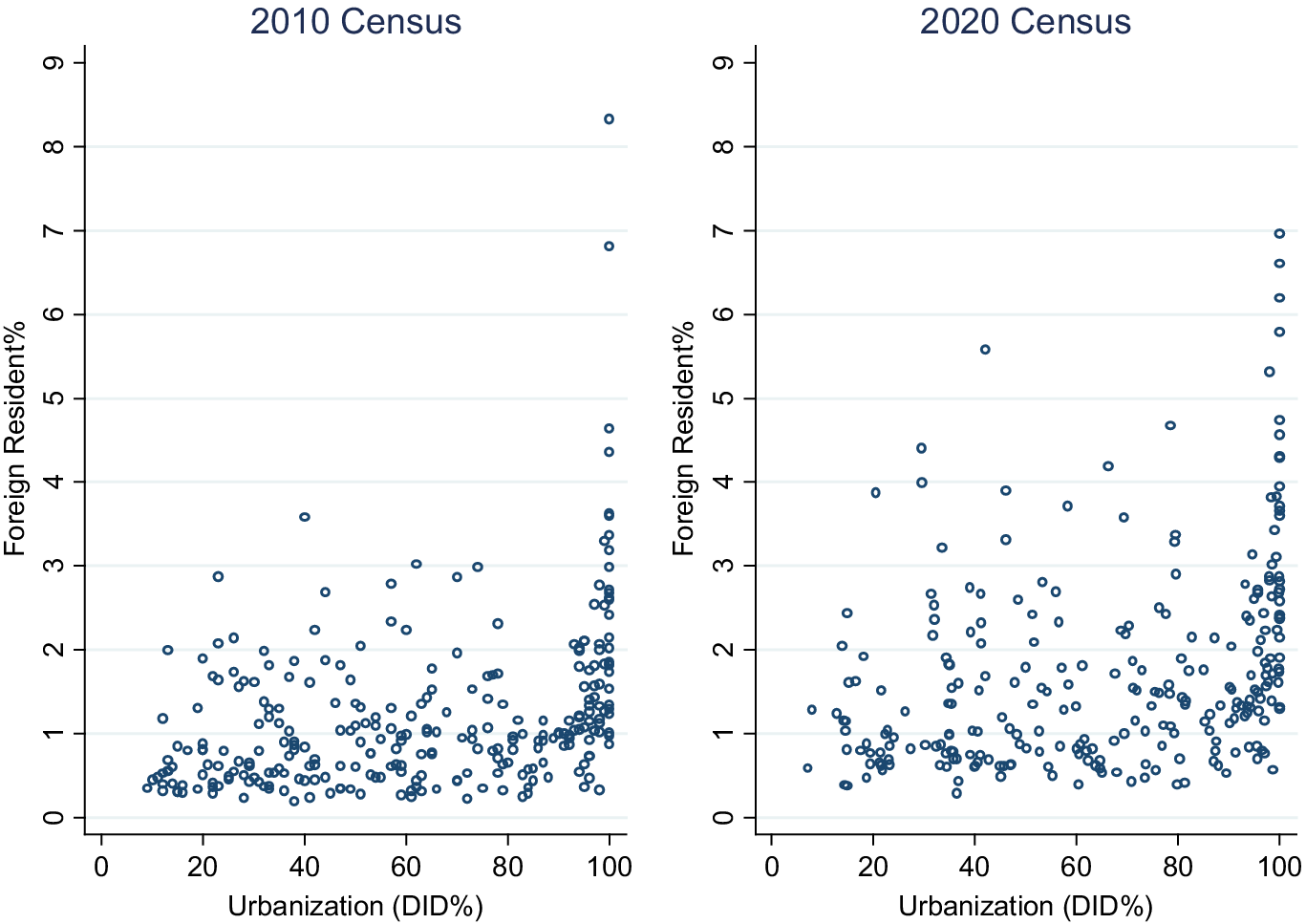

A major change that took place in rural Japan recently is a sudden increase in foreign population. The number of foreign residents in Japan doubled in the last quarter century, and the rate of increase has been particularly fast in some rural municipalities where agricultural and manufacturing sectors struggled with worker shortages (Koike Reference Koike2022). In Figure 6, the levels of urbanization (x-axis) and foreign resident percentages (y-axis) of SMDs based on the 2010 and 2020 censuses are plotted.Footnote 9 Naturally, urban SMDs have many foreigners in both years. What stands out in comparison of the two years is that some of the rural SMDs (DID%<50) saw a noticeable increase in foreign population during this period although a majority of the rural SMDs remained below the 1% line. While there was only one rural district above the 3% line in 2010, there were seven in 2020. The number of rural districts above the 2% line increased from six in 2010 to 19 in 2020.

Figure 6. Levels of urbanization and foreign resident percent of SMDs in the 2010 and 2020 censuses.

The fact that some rural SMDs saw a major spike in the number of foreigners while most of the rural districts did not hints that there were some underlying factors that promoted the influx of foreigners in some areas, most likely worker shortages. Rapid increase in foreign population in those cities and towns may then have brought some social and economic changes to the areas. Did those conditions and changes influence the opinions of LDP candidates in those areas? Are they the reason behind the shift in rural LDP candidates’ opinions toward foreign workers, shown earlier in Figure 5?

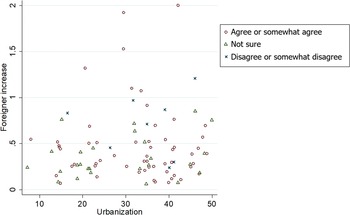

In Figure 7, LDP candidates in rural SMDs in 2021 are plotted based on the percentage point increase in foreign residents in their districts since the 2010 census (Y-axis) and their districts’ levels of urbanization. Since we are interested in candidates in rural districts, only the SMDs with less than 50% DID are shown. The symbols of the candidates represent their opinions toward foreign labor expansion: circle=agree or somewhat agree, triangle=not sure, and x=disagree or somewhat disagree. It is immediately noticeable that candidates located near the top of the graph are mostly pro-foreign worker. In the SMDs where foreign residents increased by one percentage point or more, six out of seven of the LDP candidates in 2021 agreed or somewhat agreed with foreign labor expansion. Perhaps, candidates in the areas where foreign workers were needed and thus increased realize the acute needs of workers in their home districts and took positions accordingly. (See the Appendix for a multivariate analysis.)

Figure 7. Rural LDP candidates’ positions on foreign worker increase and district characteristics.

Conclusion

Priscilla Lambert (Reference Lambert2007) finds that, in the face of intense labor shortages, the LDP has agreed to expand access to parental leave and childcare despite the LDP’s normative commitment to the idea of a traditional family with a male breadwinner and a female homemaker. It seems like the intense labor shortages that Japan has been facing in recent years are having a similar effect on politicians and political candidates, particularly those from rural Japan. Voters in rural areas and their representatives have historically been more socially conservative, and that includes being more opposed to foreign residents. However, the problems of labor shortages and a rapidly declining population seem to have become more difficult to ignore, and even those political candidates from rural areas are more willing to indicate support for the increases in foreign labor that, in many cases, are already occurring in the districts that they are campaigning to represent.

Despite this trend, there is evidence that some political candidates still fear a backlash for being seen as the politician from their region that is supportive of immigration, as in prefectures where larger percentages of political candidates “neither agree nor disagree” with the foreign labor question, the overall candidate opinion on foreign labor is less supportive than in prefectures where larger percentages of candidates are willing to take a position.

As discussed above, Abe seems to have been convinced to support the Specified Skilled Visa because he was not convinced it is an “immigration policy,” because most of the work visas offered would be temporary, and workers would be required to return to their countries of origin after the completion of their visa. So far, this has been the case. As of June 2024, there were 251,594 foreign workers in Japan on the Type 1 Specified Skilled Visas that have a definite end point while there were only 153 foreign workers on the Type 2 Specified Skilled Visas that include a legal path to permanent residency (these are the workers that Prime Minister Abe would have considered “immigrants.”). Should these numbers change, it is certainly possible to imagine a backlash among political candidates that have historically been reluctant to use what Glenda Roberts (Reference Roberts2012) calls “the I word” (“immigration,” or “imin,” in Japanese). Given the intense labor shortages that a rapidly aging Japan is facing throughout the country, but especially in rural areas, there will continue to be intense economic pressure for foreign laborers to be admitted to Japan. However, the question of how these laborers will be admitted and how they will be legally treated once they get to Japan will be worked out by politicians that are ultimately guided by a drive for reelection rather than a drive for economic efficiency.

Competing interests

The authors declare none

Appendix

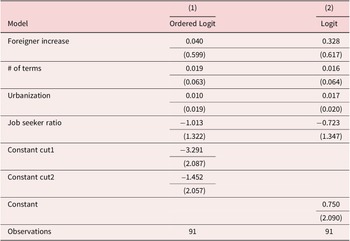

In Figure 7, we observed that candidates who ran in areas where foreign residents greatly increased were more likely to support foreign worker expansion. We also ran maximum likelihood estimation to analyze the pattern.

In the Table A1, Model 1 employs the ordered logit model where LDP candidates’ positions on foreign worker intake at the time of the 2021 election are coded as Agree (2), Not sure (1) and Disagree (0). In Model 2, the dependent variable is re-coded as Agree (1) or Not (0), and the logit model is used. The main independent variable is the percentage point change in foreigner population in the candidates’ districts from the 2010 census to the 2020 census. In addition, the number of previous terms the candidates have served, the districts’ levels of urbanization, and the job seeker ratio are added as control variables. (Since job seeker ratio is not available at the district level, prefecture-level data are used.)

In both models, the “Foreigner increase” variable has a positive sign, which is consistent with our argument. Yet, the variable is not statistically significant in either model—perhaps due partly to the small sample size. Further investigation into this pattern is an important topic for future research.

Table A1. Determinants of LDP Candidates’ Opinions on Foreign Worker Intake

Standard errors in parentheses

**p<0.01, *p<0.05