Introduction

As a result of the Mongol conquests, the kingdom of Georgia was under heavy Mongol influence from the 1230s until the reign of George V the Magnificent (r. 1314–46) (Nark'vevebi 1979: 623–9), who liberated Georgia from Mongol rule and created a very strong state. The most important source on this period of Georgian history is the anonymous fourteenth-century ასწლოვანი მატიანე Asc'lovani Mat'iane (Chronicle of One Hundred Years),Footnote 2 which, as a legacy of the Mongol domination, attests numerous Old Georgian transcriptions of Middle Mongol in its extant manuscripts. Some of these transcriptions were studied in 1917 by Boris Jakovlevič Vladimircov (1884–1931), but these transcriptions, and Vladimircov's pioneering work on them, have been nearly completely forgotten by Mongolistic scholarship. A new, modern study of this important data needs to be undertaken on the surviving manuscripts as Vladimircov dealt with only a small fraction of the Mongol data contained therein.

It is with this goal in mind that we began collaborating on a joint study examining the Georgian transcriptions of Middle Mongol contained in this important text and on the historical and cultural value of this source.Footnote 3 In this paper we present a small selection of our joint work – a preliminary analysis of the Georgian transcriptions of the Middle Mongol zodiac animal names from the point of view of Mongolian and Georgian philology and historical linguistics.

1. The data

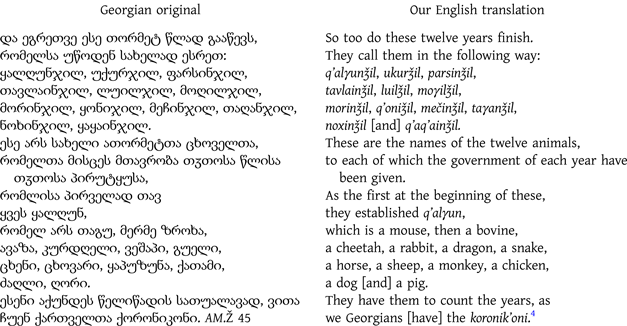

The glossed Georgian transcriptions of the 12 animals of the Middle Mongol zodiac occur in a complete list in the following passage:

1.1. The Middle Mongol names of the zodiac animals in Georgian transcription

In this section we shall deal with phonological, phonetic and morphological issues of how the author of the fourteenth-century anonymous Chronicle rendered Middle Mongol words and expressions into Georgian, and how to reconstruct the original Mongol forms.

1.1.1. Morphological structure of the animal years

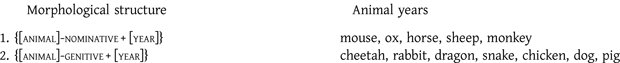

The Georgian transcriptions of the Middle Mongol animal years of the zodiac are attested in the following two morphosyntactic constructions:

The {[animal]-nominative + [year]} construction is attested throughout Middle Mongol records and in modern Mongolian. As we shall demonstrate below, the {[animal]-genitive + [year]} construction reflects non-native morphosyntactic order, undoubtedly influenced by Georgian syntax.

The Mongol word for “year” is consistently phonetically transcribed in Georgian script in these zodiac constructions as ჯილ ǯil “year”.Footnote 5 It is cognate to eastern MMgl 真勒 ~ 只勒 ǰil [ʧil] “year (年)” (SHM §141, §153, etc.), which is a loan from Turkic.Footnote 6 Mongol ǰ represents voiceless unaspirated [ʧ] or voiced [ʤ] depending on the dialect. In Georgian, the grapheme ჯ ǯ indicates a voiced post-alveolar affricate phoneme /ʤ/. The voicing of this initial consonant is interesting to note, since in most eastern varieties of Middle Mongol the corresponding consonant is transcribed in Chinese with a voiceless unaspirated consonant. In Persian and Arabic transcriptions of this segment, it is written with the Arabic letter ج ǰ, e.g. western MMgl جِيْل ǰil “year” (Leid. 71a-03-6), a consonant which in Arabic transcriptions of Mongol can render both Mongol ǰ and č.Footnote 7 Because of the rich consonant inventory of the Georgian language, which distinguishes three obstruent series, i.e. voiced, voiceless aspirated and voiceless unaspirated ejective,Footnote 8 the Georgian evidence confirms that western Middle Mongol was characterized by voiced consonants.Footnote 9

1.1.2. Transcriptions of the animal names

The Middle Mongol animal zodiac as attested in Georgian transcription follows the traditional order still employed in Mongolia today, i.e. mouse, ox, tiger or cheetah, hare or rabbit, dragon, snake, horse, sheep, monkey, chicken, dog and pig (quoted here not in their Chinese, but Mongolian values).Footnote 10 We follow this order in presenting the transcriptions of zodiac animals below. Headwords below are cited below first in romanization (in bold) of the Georgian transcription, followed by the Georgian script original, an English translation and original Old Georgian form of its accompanying semantic gloss, and attested page(s) in AM.Ž, followed by our discussion and reconstructions.

The Mouse

q'alγun ყალღუნ “mouse (თაგუ)”, attested in the word ყალღუნჯილ q'alγunǯil “Year of the Mouse” (AM.Ž 45).

Some manuscripts have ყურყუნ q'urq’un “mouse (თაგუ)” in the words ყურყუნიჯელ q'urq’uniǯel and ყურყუნიჯლ q'urq’uniǯl. Given these variants and the transcriptions of Middle Mongol attested in other sources, the original Georgian transcription was undoubtedly *ყულღუნ *q'ulγun “mouse”Footnote 11 + ჯილ ǯil “year (წელი)”, cognate to eastern MMgl 中忽![]() 中合納 ~ 中忽魯中合納 quluqana [qʊlʊqana], glossed as “mouse, rat (鼠)” (SHM §111 etc.; HYYY §1.06a7). In other sources on western Middle Mongol, the word appears as قُلقُنَا qulquna [qʊlqʊna] “mouse” (Leid. §66b-09-5) and in the Muqaddimat al-Adab by Abū 'l-Qāsim Maḥmūd ibn ʿUmar al-Zamaḫšarī (1074-1144) as قولغونه qulγuna “mouse” (MAA: Poppe 1938: 309). The Middle Mongol word is also attested as a loanword in New Persian in the form قولقنه qūlquna “Maus” and as a loanword in certain Ewenki and Turkic dialects (TMEN I: 440 §308).

中合納 ~ 中忽魯中合納 quluqana [qʊlʊqana], glossed as “mouse, rat (鼠)” (SHM §111 etc.; HYYY §1.06a7). In other sources on western Middle Mongol, the word appears as قُلقُنَا qulquna [qʊlqʊna] “mouse” (Leid. §66b-09-5) and in the Muqaddimat al-Adab by Abū 'l-Qāsim Maḥmūd ibn ʿUmar al-Zamaḫšarī (1074-1144) as قولغونه qulγuna “mouse” (MAA: Poppe 1938: 309). The Middle Mongol word is also attested as a loanword in New Persian in the form قولقنه qūlquna “Maus” and as a loanword in certain Ewenki and Turkic dialects (TMEN I: 440 §308).

Unlike the ambiguous Chinese gloss “mouse, rat (鼠)” in the Chinese sources on Middle Mongol, the unambiguous translation of Mongol qulquna into Georgian as თაგუ tagu, which only means “mouse” and not “rat”, makes it very clear that this Middle Mongol word – like its modern Khalkha Mongolian reflex хулгана [ˈχʊɮʁə̆n ~ ˈhʊɮʁə̆n] – denotes a “mouse” and not a “rat”. Thus, in the Mongolian zodiac, in both medieval and modern times, this is the “Year of the Mouse”.

The Ox

ukur უქურ “bovine (ზროხა)”, attested in the word უქურჯილ ukurǯil “Year of the Bovine” (AM.Ž 45),Footnote 12 parsable as უქურ ukur “bovine (ზროხა)” + ჯილ ǯil “year (წელი)”.Footnote 13

This word is cognate to eastern MMgl 忽客舌児 hüker [hukʰər] ~ 忽格児 hüger [hugər] “ox (牛)” (SHM §121 etc.; HYYY §1.05b1).Footnote 14 In the Muqaddimat al-Adab, a western Middle Mongol form اوكر üker is given (MAA 377). Other attested western varieties of Middle Mongol exhibit a phonological form similar to the eastern dialects, e.g. هُوْكَرْ hüker [hukər] “cow (گاوْ)” (Leid. §66b-03-1). The Georgian transcription is remarkable in its deletion of the initial laryngeal fricative /h/ in this word. As Georgian always maintains initial /h/ in native and loaned words, this transcription may indicate a dialectal Mongol form.Footnote 15 Examination of the other Mongol words in AM.Ž will help to determine whether this western Mongol dialect lost /h/. Another possibility is that the author was influenced by Literary Mongol orthography, as he was clearly both fluent and literate in Mongol (q.v. AM.Ž 44–5). In spoken Middle Mongol, this word has an initial /h/, but in Literary Mongol it is written üker as Literary Mongol is a borrowed script which offers no grapheme for the Mongol phoneme /h/.Footnote 16

The Middle Mongol word is also attested as a loanword in New Persian هوكر hǖkär ~ هوكار hǖkǟr ~ هوكير hǖker “Rind, Stier” (TMEN II: 538 §397) and as a loanword in Turkic and other languages (TMEN II: 539–40).

This word is widely attested in Mongolic daughter languages. In modern Literary Oirat, there are two reflexes of this word, üker and, with progressive rounding assimilation, ükür “ox” (IDWO 483). Note also Daur xukur, Shira Yoghor hogor, Mongghul fuguor and Hungarian ökör “id.” (Kara Reference Kara2009: 315), the latter of which is widely believed to be a loanword from an early variety of western Old Turkic, perhaps ultimately from Indo-European.Footnote 17

The Tiger/Cheetah

pars ფარს “cheetah, Acinonyx jubatus (ავაზა)”, attested in the word ფარსინჯილ parsinǯil “Year of the Cheetah” (AM.Ž 45).

The Georgian rendering of this Mongol phraseFootnote 18 is a non-native attempt to transcribe a phonologically progressive spoken western Middle Mongol dialectal *pars-in ǰil (cheetah-GEN year), which is a logically possible but unattested phrase.Footnote 19 Judging from the animal years attested in other Middle Mongol sources, this form is also stylistically non-native. In other Middle Mongol texts and in modern Mongolian, as mentioned above, the animal years are expressed as [animal]-nominative + ǰil “year”. As for this concrete case, in the Secret History of the Mongols, the Year of the Tiger is attested in the form 巴舌児思 只勒 bars ǰil (SHM §202) and in modern Khalkha Mongolian as бар жил “Year of the Tiger”, both literally “tiger year”. The non-native Mongol grammar of the Georgian rendering ფარსინჯილ parsinǯil indicates that the author of the Chronicle was a fluent, albeit non-native, speaker of Mongolian, and that most of the Mongolian words and expressions in this book were personally written down by him from memory. This particular error indicates that the author of the Chronicle had good grammatical knowledge of Mongolian (i.e. morphosyntactically correct grammar), but he seems to have been influenced by his native language here, which would use the genitive.Footnote 20

The transcription of ფ p /pʰ/ instead of the expected b (which would be easily represented in Georgian with the letter ბ b) is worth discussion. Comparison with Ottoman Turkish pars “leopard, panther”,Footnote 21 which is historically related to, although semantically and phonologically distinct from, the eastern Middle Mongol word bars “tiger”, suggests that the Georgian transcription of the western Middle Mongol dialect word pars “cheetah” is phonetically influenced by western Turkic pars or New Persian پارس pārs “leopard, panther”. Western Middle Mongol ფარს pars “cheetah (ავაზა)” can thus be seen as a then-recent Turkism (or less likely, a Persianism) in the Georgian transcriptions of Middle Mongol.Footnote 22

It is well known that the Mongol Empire and its successor states were characterized by widespread bilingualism in Mongol and Turkic. In the western regions of the empire Turkic was even more actively used. This can be observed in the numerous Turkisms among the Mongol lexical data in the Jāmiʿ al-tawārīḫ (Compendium of Chronicles) by Rašīd al-Dīn Faḍl Allāh (1247–c. 1318) and in languages resulting from intense Mongol–Turkic language contact, such as Chaghatai Turkic and the Kipchak (Qïpčaq) languages.Footnote 23 Such Turkisms are also commonly found in the medieval Latin accounts of William of Rubruck, John of Plano Carpini, and Marco Polo.Footnote 24

The semantic value is also significant: in most Middle Mongol sources the word bars is glossed as “tiger”, but the Georgian transcription is glossed in Georgian as ავაზა avaza “cheetah”. Although the cheetah is now restricted to a small and dwindling population in Africa, in earlier times it had a vastly wider geographic distribution, including Georgia.Footnote 25

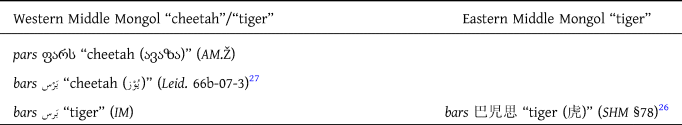

The geographic distribution of the “cheetah”/“tiger” vs. “tiger” glosses suggests a partial semantic isogloss: in the eastern Middle Mongol dialects, bars denoted only “tiger”, whereas in the western dialects, bars ~ pars indicated “cheetah” as well as “tiger” (in the variety documented by IM) as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Partial isogloss of “cheetah”/“tiger” and “tiger” in Middle Mongol dialects

The Georgian gloss of this Middle Mongol word as ავაზა “cheetah”, together with the phonological arguments discussed above, demonstrates that the anonymous Georgian author of the Chronicle had access specifically to a western dialect of Middle Mongol.

Doerfer identifies New Persian بارس bārs “Gepard, Cynailurus jubatus L.” as a borrowing from Turkic bars “Panther, Felis panthera, später auch ‘Gepard’” (TMEN II: 235). Note also Russian барс (bars) “leopard”, borrowed from a Turkic language.Footnote 28

The Hare/Rabbit

tavlai თავლაი “rabbit (კურდღელი)”, attested in the word თავლაინჯილ tavlainǯil “Year of the Rabbit” (AM.Ž 45).

The name of this year in some manuscripts is altered to თავლაინჯალ tavlainǯal, თვლა ინჯლ tvla inǯl, or თვალინჯალ tvalinǯal,Footnote 29 but the corruption of the Mongol word taulai could be considered as a kind of lectio facilior: it seems that the copyists did not understand the word თავლაი tavlai and replaced it in the second case with the Georgian verbal nounFootnote 30 თვლა tvla “to count” and in the third with the Georgian noun თვალი tvali “eye”. Moreover, in the expression თავლაინჯილ tavlainǯil we can observe the same type of error as in the case of pars ფარს “leopard” (see the entry for “The Tiger/Cheetah” above), in which the first noun of the compound word is declined in genitive case. The sequence av ავ in the Georgian transcription renders Middle Mongol au. Thus, the transcription indicates Middle Mongol taulai in Georgian phonetic transcription as თავლაი tavlai “rabbit (კურდღელი)”.

This word is cognate to eastern MMgl 討來 taulai [tʰaʊ̯lai̯] ~ 塔兀來 ta'ulai [tʰaɦʊlai̯] “rabbit, hare (兔, 兔児)” (SHM §257, §272, §239; HYYY §1.06a2). Note also western MMgl تَاولاَي taulai [taʊ̯lai̯] ~ تُولاَىْ tūlai [tʊːlai̯] (Ligeti Reference Ligeti1962: 68, 70) and in Armenian transcription as թուլայ t‘ulay (phonetically [tʰulay]) “id.” (Ligeti Reference Ligeti1965: 283.28).

Middle Mongol taulai was borrowed in New Persian, attested as taulai “Hase”, and as a loanword in Tibetan, Russian dialects and in certain Tungusic languages.Footnote 31

The ვ v in the Georgian transcription deserves discussion. In late Middle Mongol, including other western sources contemporaneous to the Georgian transcriptions, the first syllable in the Mongol word was a diphthong [aʊ̯] or vowel + glide sequence [aw].Footnote 32 Accordingly, the Georgian transcription of Mongol au as ავ av assumes an intermediate step *აჳ aw. The now-obsolete Georgian letter ჳ was created to render Greek ὖ ψιλόν. Although Greek υ denotes the front rounded vowel [ü], Georgian ჳ renders its Georgian phonetic approximation [wi] (Gamkrelidze Reference Gamkrelidze1990: 146). As for Greek diphthongs such as αυ or ɛυ, the letter υ signifies a [w] glide. An analogous use of ჳ is observed in Old Georgian texts as early as the fifth to seventh centuries, where [w] is sometimes transcribed in Georgian with ჳ w and sometimes with ვ v (Sarǯvelaʒe Reference Sarǯvelaʒe1984: 292; Gamkrelidze Reference Gamkrelidze1990: 147). Thus, by replacing the letter ჳ w with ვ v, on the one hand, the copyist attested the existence of the diphthong in the Mongolian archetype and on the other hand, he did justice to Georgian phonology by recording the letter corresponding to the phoneme that was actually pronounced in Georgian.

The earliest attested Serbi-Mongolic cognate of this word is Middle Kitan *tawlya “rabbit, hare”.Footnote 33 Old Turkic tabïšγan “rabbit, hare” is widely believed to be related, although by convergence (LASM 5–6).

The Dragon

lu ლუ “dragon (ვეშაპი)”, attested in the phrase ლუილჯილ luilǯil “Year of the Dragon” (AM.Ž 45).

The word has no variants in the manuscripts. This is clearly a copyist's error for *ლუინჯილ *luinǯil,Footnote 34 undoubtedly another non-native attempt to write the year name as [animal] + *-(y)in “spoken genitive case suffix” + ǰil “year”, i.e. ლუ lu “dragon” + *-ინ *-(y)in “spoken genitive case suffix” + ჯილ ǯil “year” (see entries for “The Tiger/Cheetah” and “The Hare/Rabbit” above for discussion of a similar error). This year name is attested in other Middle Mongol sources as 祿 丁真 lu ǰil “dragon year (龍年)” (e.g. HYYY 3.04b3) and in spoken modern Khalkha as луу жил [ɮʊː ʧiɮ] “dragon year”, i.e. “dragon” + “year”.

Western Middle Mongol ლუ lu “dragon” is cognate to eastern MMgl 祿 lu [lʊ] “dragon (龍)” (HYYY §1.05a3) and western MMgl لو lu “dragon” (Golden Reference Golden2000: 199c.12). It is ultimately a loanword into Old Turkic lu ~ ulu ~ lü ~ lüi “dragon” and Mongolic from a Middle Chinese dialect form of 龍 “dragon” (Kara Reference Kara2009: 170). The word is attested in Serbi-Mongolic as early as Middle Kitan *lu “dragon”Footnote 35 (LASM 86, 433).

The Snake

moγi მოღი “snake (გუელი)”, attested in the word მოღილჯილ moγilǯil “Year of the Snake (AM.Ž 45).Footnote 36

In some manuscripts, the phrase is given as მოღიჯილ moγiǯil, which has been interpreted by the editors of the Chronicle Footnote 37 as a corruption, but from the Mongolistic point of view, this is clearly the correct form, as the usual form of this year name in other Middle Mongol sources is 抹中孩 丁真 moqai ǰil “Year of the Snake (蛇児年)” (literally: “snake year”, e.g. HYYY 3.14a5). As Georgian phonotactics do not usually allow diphthongs, Middle Mongol ai is reduced to Georgian ი i in this Georgian transcription.

Alternatively, based on the pattern above, we may hypothesize that the Chronicle recorded the expression with the structure {[animal]-genitive + [year]}. In this case, as with *ლუინჯილ *luinǯil “year of the dragon” (see entry for “The Dragon” above), the expression *მოღინჯილ *moγinǯil (rendering spoken MMgl dial. *moγ(a)i-n ǯil “snake-GEN year”) would have been altered by the copyists to მოღილჯილ moγilǯil.

This Middle Mongol moγ(a)i “snake” is cognate to eastern MMgl 抹孩 moqai [mɔqai̯] “snake (蛇)” (HYYY §1.06b4, §3.14a5), western late Middle Mongol موغاي moʁay “snake” and to Middle Kitan *mɔʁɔ “snake”,Footnote 38 all ultimately from Common Serbi-Mongolic *mɔga ~ *mɔgɔ “snake” (LASM 353 and n. 307).

The Mongol word was borrowed into New Persian as موغاى mōγāi ~ موغا mōγā “Schlange” and was also borrowed into certain Turkic languages and Russian dialects.Footnote 39

The Horse

morin მორინ “horse (ცხენი)”, attested in the word მორინჯილ morinǯil “Year of the Horse” (AM.Ž 45).Footnote 40

This word is cognate to eastern MMgl 秣舌驎 morin [mɔrin] “horse (馬)” (e.g. SHM §31) and western MMgl مُوري mori (Leid. 66a-13-1) ~ مُوريْن morin “horse” (Leid. 75a-10-3-1, 75a-12-1-1), also attested in Armenian phonetic transcription as մօրի mori “horse” (Ligeti Reference Ligeti1965: 281.21). The Mongol forms are cognate to Middle Kitan *mir “horse”,Footnote 41 from Common Serbi-Mongolic *mɔrɪ “horse” (LASM 352–3), itself a culture word with comparanda in Old Chinese, Koreanic, Tungusic, Japanese-Koguryoic, Old Tibetan, Nivkh, and other languages.Footnote 42

The Sheep

q'oni ყონი “sheep (ცხოვარი)”, attested in the word ყონიჯილ q'oniǯil “Year of the Sheep” (AM.Ž 45).Footnote 43

In the Letter of Il-Khan Abaga (1271), this calendrical formula is attested as qonin ǰil “Year of the Sheep”, with the expected attributive suffix -n. The lack of this suffix in the Georgian transcription is noteworthy.Footnote 44

This word is cognate to western MMgl قُنيْ qoni “sheep”Footnote 45 (Leid. 66b-03-3) and eastern MMgl 中豁紉 qonin [qɔnin] “sheep (羊)” (SHM §19 etc.; HYYY §1.05b1), i.e. qoni-n at the morphological level.Footnote 46 The Mongol forms are cognate to Late Kitan 昬 (probably rendering *qɔñ) “sheep”, all ultimately from Common Serbi-Mongolic *kʰɔnɪ “sheep” (LASM 365), undoubtedly related to Old Turkic qoñ “sheep” via a loanword relationship (LASM 365 n. 425).Footnote 47

The Monkey

mečin მეჩინ “monkey, ape (ყაპუზუნა)”, attested in the word მეჩინჯილ mečinǯil “Year of the Monkey” (AM.Ž 45).Footnote 48

This word is cognate to MMgl *meči-n “monkey, ape”, attested not on its own, but as a component morpheme of western MMgl سُرمجى sormeči “monkey, ape” in the glossary of Ibn Muhannā (Poppe 1938: 446), a blend of *sor, from Late Old Chinese 猿 *zuar “monkey, ape” and *meči-n “monkey, ape”, the latter ultimately a loanword from Old Turkic bičin “monkey, ape” (the alternation between m ~ b in early Turkic-Mongolic loanwords is well known).Footnote 49 The Old Turkic word in turn is likely to be a borrowing from Iranic, perhaps related to New Persian بوزينه būzīna “monkey, ape” (EDT 295b). The modern Khalkha reflex of this Middle Mongol word is мич [miʧʰ] “monkey, ape” (almost exclusively in its calendrical usage), sometimes also бич [piʧʰ] “id.”Footnote 50

The Middle Mongol phrase is also attested in Preclassical Literary Mongol in the form bičin ǰil “year of the monkey” in the Fragments of a Letter of Abū Sa’īd (1320).Footnote 51

The Turkic form was borrowed into New Persian (see TMEN II: 382–3 §821).

The Chicken

taγa თაღა “chicken (ქათამი)”, attested in the word თაღანჯილ taγanǯil “Year of the Chicken” (AM.Ž 45).Footnote 52

This word is cognate to eastern MMgl 塔乞牙 takiya [tʰakʰija] “chicken (雞児)” (SHM §141, §264) ~ 塔乞牙 “chicken (雞)” (HYYY §1.07a7) and western MMgl طاقيه taqi'a [taqija] “chicken” (MAA 341). The Georgian transcription perfectly matches western MMgl taγa “chicken” in Persian and Arabic phonetic transcription, attested in the plural form تاغااوُتْ taγa-wut “hens” ~ “roosters” (Leid. 68b-12-5, 68b-13-2-2). Also note the Armenian phonetic transcription թախեա t‘axea (phonetically [tʰaxea]) “chicken” (Ligeti Reference Ligeti1965: 285.29).

The Mongol forms are cognate to Middle Kitan *taqa “chicken, hen”Footnote 53 (LASM 372). These forms are related to Middle Turkic takagu “hen”, undoubtedly as a loanword, the directionality of which remains to be determined (LASM 372 n. 472). Certain neighbouring languages, such as Korean, Hungarian, and Jurchen-Manchu, exhibit phonetically similar words for “chicken” (see LASM 372 n. 472; Ligeti Reference Ligeti1986: 43; Kara Reference Kara and Krueger2005: 13–14; Kane Reference Kane2009: 88; Aisin Gioro 2004: 96 §50).

The Dog

noxi ნოხი “dog (ძაღლი)” attested in the word ნოხინჯილ noxinǯil “Year of the Dog” (AM.Ž 45),Footnote 54 rendering spoken MMgl dial. *nox(a)i-n ǯil “dog-GEN year”.Footnote 55

This word is cognate to eastern MMgl 那中孩 noqai [nɔqai̯] “dog (狗)” (SHM §78 etc.) and western MMgl نوُقَايْ noqai “dog”Footnote 56 (Leid. 66b-09-3). In Armenian script, this Mongol word is phonetically transcribed նուխա nuxa “dog” (HNA), suggesting a Middle Mongol dialect form *[nɔχa] “dog”. Other Armenian sources give the transcription նօխայ noxay “dog” (Ligeti Reference Ligeti1965: 282.24), i.e. MMgl [nɔχai̯] “dog”. The Middle Mongol word was borrowed into New Persian as نوقاي nōqāi ~ نوقا nōqā “Hund” (TMEN II: 520 §386) and was also borrowed into Turkic and possibly Samoyedic (TMEN II: 520–21 §386). The Mongol forms are cognate to Middle Kitan *ñaq “dog”Footnote 57 and to Taghbach *ñaqañ “dog”, ultimately going back to Common Serbi-Mongolic *ñɔkʰañ “dog” (LASM 356).

The Pig

q'aq’ai ყაყაი “pig (ღორი)”, attested in the word ყაყაინჯილ q'aq’ainǯil “Year of the Pig” (AM.Ž 45).Footnote 58

This word is cognate to eastern MMgl 中合中孩 qaqai [qaqai̯] “pig (豬児)” (SHM §166, §268) and western MMgl غَاقَايْ γaqai “pig (خُوك)” (Leid. 66b-07-5) and غاقاى γaqai “id.” (MAA: Poppe 1938: 175).

The Middle Mongol form was also borrowed in New Persian, attested as قاقا qāqā “Schwein”, and in certain Turkic languages (TMEN I: 382 §259).

1.2. Reconstructed Middle Mongol genitive case morphemes in Georgian transcription

The animal zodiac constructions above provide evidence of two allomorphs of the Middle Mongol genitive case suffix:

*-in -ინ (Geo -in)Footnote 59 ~ *-n -ნ (Geo -n)Footnote 60 “genitive case suffix allomorph”, cognate to eastern Middle Mongol -yin “id.”.

2. Reconstructed western Middle Mongol words in Georgian transcription

The tentative reconstructions of western Middle Mongol forms discussed above are presented in alphabetical order below:

Concluding remarks

As our analyses above indicate, the fourteenth-century anonymous Georgian author, conventionally known as Žamtaaγmc'ereli, demonstrates surprising accuracy in the phonetic transcription of Mongol phonemes. This Georgian source proves very important for the history of the Mongolian language, because a careful examination of the Georgian transcriptions of medieval Mongol zodiac calendrical terms in it allows us to:

1) identify the specific Mongol dialect of the transcriptions as a western dialect of Middle Mongol exhibiting certain phonetic similarities to other varieties of Middle Mongol in Persian, Arabic and Armenian phonetic transcription;

2) reconstruct Middle Mongol dialect forms which are phonetically distinctive from other sources (e.g. western Middle Mongol *taʁa “chicken” and *qʊlʁʊn “mouse”);

3) clarify the precise semantic values of certain Middle Mongol words which are ambiguously glossed in Chinese (e.g. *qʊlʁʊn, glossed as “mouse” in Georgian, but ambiguously glossed in Chinese as “rat, mouse”);

4) uncover an informative semantic gloss providing insight on cheetahs in Georgia at the time of Mongol domination and thereby also identify a partial semantic isogloss between eastern and western Middle Mongol dialects (i.e. western Middle Mongol pars ~ bars “cheetah, tiger” vs. eastern Middle Mongol bars “tiger”); and

5) attest an early example of the spirantization of the intervocalic plosive q > χ (e.g. earlier eastern MMgl noqai “dog” corresponds to noxi “dog” in Georgian transcription).

The Chronicle offers a wealth of data on other aspects of medieval Mongol language, culture and history which we plan to address in future studies.

Abbreviations and sigla

- AM.Ž

Žamtaaγmc'ereli, Asc'lovani mat'iane (1987, edited by R. K'ik’naʒe)

- BYV

Vladimircov (1917)

- corr.

correction of

- CPG

Clavis Patrum Graecorum, 1–5, cura et studio M. Geerard. (Corpus Christianorum). Turnhout: Brepols, 1974–87; Supplementum, cura et studio M. Geerard and J. Noret. (Corpus Christianorum). Turnhout: Brepols, 1998

- EDT

Clauson, Etymological Dictionary of Pre-Thirteenth Century Turkish (1972)

- Geo

Georgian

- HNA

Blake et al., History of the Nation of the Archers (Reference Blake, Frye and Cleaves1954)

- HYYY

Hua-Yi Yiyu (Kuribayashi Reference Kuribayashi2003)

- IDWO

Integrated Dictionary of Written Oirat (Kuribayashi Reference Kuribayashi2017)

- KAS

Kitan Assembled ScriptFootnote 74

- KLS

Kitan Linear ScriptFootnote 75

- IM

Ibn Muhannā (Poppe 1938, Gül Reference Gül2016)

- LASM

Shimunek (Reference Shimunek2017)

- Leid.

The Leiden Manuscript, i.e. Kitâb Majmû‘ Turjumân Turkî wa-‘ajamî wa-Muğalî (Saitô Reference Saitô2006, Poppe Reference Poppe1928)

- MAA

Muqaddimat al-Adab [by Abū ’l-Qāsim Maḥmūd ibn ʿUmar al-Zamaḫšarī] (Poppe 1938)

- MMgl

Middle Mongol

- ms.

manuscript

- mss.

manuscripts

- RÉGC

Revue des études géorgiennes et caucasiennes

- SHM

Mongqol-un Niuča To[b]ča'an (Secret History of the Mongols, quoted from Kuribayashi Reference Kuribayashi2009)

- TMEN

Doerfer, G. Reference Doerfer1963; Reference Doerfer1965; Reference Doerfer1967. Türkische und mongolische Elemente im Neupersischen.

Symbols

- *

Scientific reconstruction based on mainstream historical–comparative linguistic methods

- ✘

Erroneous form or scribal error

- / /

Phonemes

- [ ]

Phonetic transcription (in IPA or other writing systems)

- ‐

Morpheme boundary

- ~

Linguistic variation between two or more forms (free or conditioned)