John Bentley was appointed Commissioner of Pensions in late March 1876. He was the fifth man appointed to the position by President Ulysses Grant, and the third in little over a year; indeed, his predecessor had resigned after little more than a month in office.Footnote 1 The new commissioner was, in many respects, an unusual appointment to this plum patronage position, a man with little political experience and no military credentials in an office that would come to be regarded as the preserve of pliant party operatives and prominent members of the veterans’ community. Since settling in Wisconsin in 1859, Bentley had established himself in the legal profession and made a name for himself in local political circles, but his only government experience had come during a single two-year term in the state senate toward the end of the Civil War. Since then, Bentley had worked in the railroad industry, serving for a time as the president of a local railroad company, the Sheboygan and Fond du Lac. While his 1872 campaign to return to the state senate met with defeat, however, his political career was far from over. When Commissioner of Pensions Charles Gill, himself a former Wisconsin state senator, announced his intention to resign due to his poor health, the state’s senators were determined to retain the position for Wisconsin, and their search led them to John Bentley.Footnote 2

The new commissioner confronted an unenviable task. By the time Bentley arrived in Washington, the U.S. Pension Bureau was plagued by problems. The Civil War had heralded a revolution in the nation’s system of military benefits. While the federal government had long provided pensions to the soldiers disabled in its wars, the sheer scale of the internecine conflict had demanded the creation of a new and more comprehensive system of benefits.Footnote 3 In July 1862, Congress established a new system of military pensions – the so-called general law system – which was unprecedented in its generosity and scope. Pensions were to be offered to any Union soldier who had been disabled by wounds incurred or diseases contracted in the line of duty, as well as to the widows and orphans of the war dead. While pension rates were initially modest – enlisted men were entitled to a maximum pension of just eight dollars a month – lawmakers soon began to pass laws that established higher rates of compensation for specific disabilities and extended entitlement to an array of noncombat troops and dependent relatives.Footnote 4 That Congress had passed such legislation before the end of the conflict, and thus anticipated the needs of men yet to be wounded, was, perhaps, just as significant as its more specific provisions; typically, lawmakers had passed military pension legislation only years after the intended beneficiaries had returned from the battlefield.Footnote 5

Yet although Congress had established a new and more generous system of veterans’ benefits, the administration of this system lagged behind. Despite a considerable expansion in its workforce, the Pension Bureau struggled to keep up with the surge of new pension claims from the wounded men who poured from the nation’s battlefields. Prior to the Civil War, there had been just 14,000 names on the pension rolls; by the time the conflict closed, there were 85,000, and the number doubled during the following two years.Footnote 6 The Pension Bureau ran a substantial backlog, and its work was characterized by inefficiencies and long delays; most claimants waited for months, if not years, to hear the fate of their claims.Footnote 7 The profusion of new pension laws, moreover, caused considerable confusion among the officials charged with assessing the incoming claims. By 1871, one Commissioner of Pensions calculated that there were no fewer than forty-four separate pension acts upon the statute books, creating a tangle of contradictions and cross-purposes. “In some there is contrariety of provision,” he complained, “not unfrequently there is ambiguity of expression; and in some cases, a strict construction would defeat the obvious intention of the law.”Footnote 8 To make matters worse, the Pension Bureau lacked appropriate accommodation. While the commissioner and his senior subordinates were stationed in the Patent Office Building in downtown Washington, most of the agency’s work was conducted several blocks away in a converted hotel where more than 200 clerks toiled in dim, cramped, and poorly ventilated rooms.Footnote 9 The Pension Bureau’s problems did little to ease public fears about the growing costs of the pension system; rather, they contributed to an increasing skepticism about the government’s ability to weed out fraudulent claims. “In no branch of the public service,” the Chicago Tribune informed its readers in 1871, “is there a greater degree of persistent and systematic fraud than in the Pension Office.”Footnote 10 Based less, perhaps, upon the revelation of fabricated or false claims than on contemporary concerns about the costs of government, the fear that former soldiers might be foisting themselves upon the pension rolls by exaggerating their injuries and taking advantage of public sympathies reflected a growing cynicism about the character of the nation’s public life and contributed to an increasing clamor for reform.

During his five years as Commissioner of Pensions, John Bentley mounted a concerted attempt to reform the pension system and to overhaul its administrative apparatus. By examining Bentley’s administration of the pension system, this article offers a more complex picture of its development, one that ponders the prospect of alternative political pathways and reassesses its place within the broader pattern of postwar political development. Most histories of the pension system have charted its development with reference to a series of specific legislative watersheds, each of which contributed to a considerable expansion in the nation’s pension rolls. Following the Civil War, this story usually goes, lawmakers enacted a series of measures that relaxed eligibility requirements, removed limitations, and extended the promise of a pension to ever more veterans and their families, and thus lavished ever-larger sums of money on a growing number of beneficiaries; indeed, between 1880 and 1910, according to one estimate, the federal government devoted approximately a quarter of its entire expenditure on this enormous system of military pensions.Footnote 11 Little wonder, then, that some scholars have identified in this military pension system the hallmarks of an incipient welfare state. By the end of the nineteenth century, Theda Skocpol has argued, the pension system had become, in effect, a de facto disability and old-age pension program that, at least in terms of its cost and coverage, rivaled the welfare systems then being established elsewhere in the industrializing world. The United States, Skocpol contended, was not therefore the welfare state “laggard” that we once thought; rather, it was a “precocious social spending state.”Footnote 12

Yet the development of this enormous system of military benefits was never quite as seamless or as straightforward as this story might seem to suggest. By the 1870s, the pension system was at a crossroads, as federal officials, politicians, veterans, and many others engaged in discussions about its administration and presented their proposals for the future of veterans’ benefits. By exploring these debates, this article aims to reassess the significance of the pension system for understanding broader patterns of state-building in the postwar period. First, it takes seriously the place occupied by administrative officials in late nineteenth-century political culture. The Pension Bureau and its officials have occupied a peculiarly peripheral place in most accounts of the pension system. Though a growing number of scholars have explored the inner workings of the pension system from the perspective of its beneficiaries, they have less commonly explored the pivotal role played by administrative officials in shaping it, at least beyond the basic tasks of assessing pension claims and distributing pension payments.Footnote 13 Yet as Richard John once reminded us, federal agencies – and the people who administered them – often played a determinative role as agents of change.Footnote 14 By placing Commissioner Bentley at the center of the story, this article thus contributes to a growing literature that considers the place of oft-unheralded bureaucrats, and the reactions they provoked, within the processes of political development.Footnote 15 Second, this article contributes to a scholarship that emphasizes the complex and contested character of state-building by considering the significance of suppressed political possibilities. Reexamining “alternative pathways,” as C. Joseph Genetin-Pilawa has argued, forces us to reconsider our assumptions about the trajectory of political development and, frequently, highlights the “stickiness” of prevailing political frameworks.Footnote 16 By approaching Bentley’s reform-minded administration of the Pension Bureau as one such moment of political possibility, this article builds on the work of those scholars who have emphasized the constraints that confronted would-be state-builders and which often impelled a “patchwork” pattern of political development, one that was achieved piecemeal and often only partially.Footnote 17

Finally, this article suggests that conflicts over the nature of the American state during the late nineteenth century did not necessarily adhere to modern conceptions of big or limited government, or of a state that was weak or strong.Footnote 18 The Civil War pension system certainly supports the broader claims of the burgeoning scholarly literature on the American state. The United States, as scholars have documented during the past three decades, has always possessed a national state that was far more ambitious and assertive than we once believed; as William Novak has put it, conventional assumptions of nineteenth-century statelessness on the national level have been revealed to be little more than a “myth.”Footnote 19 Yet reconsidering Bentley’s administration of the pension system should also caution us against assuming the existence of a single pattern of state development or underestimating the bitterness of debates between opposing groups of would-be state-builders. Indeed, as this article will show, debates about the pension system did not simply recreate the ongoing conflict between advocates of so-called big government and proponents of limited government, but rather represented a clash between rival groups of would-be state-builders who articulated competing conceptions of what the government should look like and how it should work. Indeed, as Elizabeth Sanders has shown in her analysis of the farmers’ and workers’ movements of subsequent decades, debates about the form and function of the national state frequently centered upon the tension between competing state-building agendas – between, to use her terms, an incipient “administrative state” characterized by centralized administration, discretionary power, and a tendency toward bureaucratic policy making, on the one hand, and a “statutory state” that was carefully framed by statutes forged by elected lawmakers and possessed of a minimum of discretionary authority, on the other.Footnote 20 By exploring this putative period of reform, this article thus demonstrates that the pension system was not simply the precursor to subsequent social policies, nor was it an inevitable outcome of the human costs of conflict. Rather, it was the product of the particular preoccupations of postwar politics, one that reflected a state that was possessed of considerable potential power but was also, at the same time, something less substantial than some of its makers had in mind; not just a precocious social spending state but also a precarious one.

“A Wide Margin for Improvement”: The Bentley Plan and the Pursuit of Reform

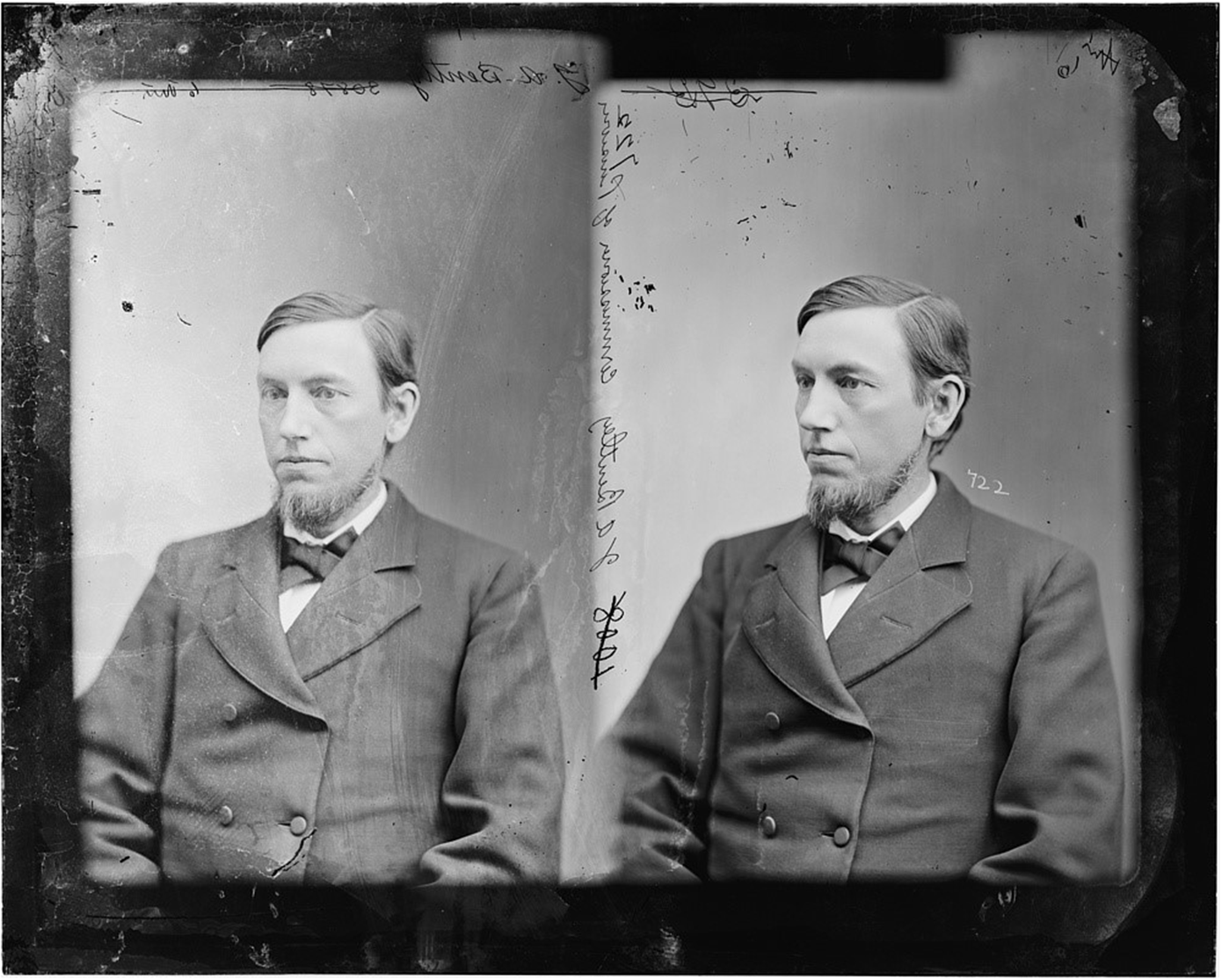

When John Bentley took charge of the Pension Bureau in March 1876, he found himself confronted with a multitude of problems. Not the least of these was the novelty of his new position. Writing to his superior, Secretary of the Interior Zachariah Chandler, in May, Bentley admitted that he had spent most of his first month in office “trying to learn something about pensions, and the duties devolving upon the Commissioner.”Footnote 21 As Bentley familiarized himself with his new responsibilities, he came to a concerning conclusion. “The doors of the Pension Office are wide open for the introduction and prosecution of fraudulent claims,” he warned Chandler just over a week later, “and it is believed upon the strongest grounds that the Government is annually paying out as pensions several millions of money to persons who are not entitled” (Figure 1).Footnote 22

Figure 1. John A. Bentley, Commissioner of Pensions. Brady-Handy Photograph Collection, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/item/2017894598

The Commissioner reiterated his views in his first annual report, issued later that year. The Pension Bureau was beset by delays in the settlement of claims, Bentley noted, which was “causing much complaint, and … undoubtedly working hardship, if not injustice, to the claimants.” The problem, Bentley believed, was the “radically defective and deficient” character of the administrative apparatus over which he now presided. Central to Bentley’s concerns was the way in which the government attempted to assess incoming pension claims. When the Pension Bureau received a new claim, it first forwarded it to a clerk who would determine whether the claimant had a prima facie case for a pension – whether, in short, they appeared to have a valid claim to a pension on account of injuries incurred, or disease contracted, during their military service, or, in the case of widows and other surviving family members, on account of the death of their soldier relative. Substantiating such claims, however, was rarely an easy proposition. The Bureau’s clerks often struggled to find firm evidence with which to support a claimant’s story. While the War Department would be asked to provide a veteran’s wartime military and medical records, such requests often took months to fulfill and, due to the limitations of wartime record keeping, rarely yielded much concrete information. Frequently, therefore, officials had to rely upon evidence submitted, ex parte, by the claimants themselves, supplemented by affidavits from their friends and former comrades. It was the Pension Bureau’s reliance upon such evidence, Bentley argued, that lay at the root of its problems: not only did it necessitate careful and time-consuming scrutiny of all new claims, but it also made the agency an easy mark for fraudsters who, by exaggerating or even fabricating their claims, might foist themselves upon the pension rolls.Footnote 23

The Pension Bureau’s administrative machinery, meanwhile, presented its own problems. Though the final decision on each claim was made in Washington, the claims-making process was characterized by the dispersal of responsibilities among a hodgepodge of part-time and private actors. The Pension Bureau’s system of medical examinations, for example, was a longstanding cause for concern.Footnote 24 Veterans who, after initial consideration of their claim, were believed to have a case for a pension, were ordered to attend a medical examination with a surgeon who would verify the existence and assess the extent of their disability and who would forward their medical report, together with a recommended rate of pension, to the nation’s capital. By the time Bentley arrived, the Pension Bureau was connected to more than 1,500 such surgeons stationed in towns and cities across the country.Footnote 25 Yet what might look, at first glance, like an impressive administrative apparatus was in reality an awkward and unwieldy system that placed public responsibilities in the hands of local physicians who supplemented their private income with the fees they could earn by doing occasional work for the federal government – a classic example of “fee-based governance.”Footnote 26 Delegating public responsibilities to private physicians, Bentley argued, presented several problems. For one thing, the varied backgrounds and methods of these surgeons undermined the coherence and consistency of the pension system and resulted in a profusion of different pension rates. For another, it placed considerable responsibility in the hands of men whose business and reputations depended upon the continued patronage of their local communities; it was, therefore, in their “professional interest,” Bentley argued, to “please the claimant at the expense of the government.”Footnote 27

The Pension Bureau also relied, to a degree not always appreciated by historians, upon the work of private entrepreneurs. Since the Civil War, claim agents and pension attorneys had cemented themselves at the center of the pension system, and with good reason: claim agents not only provided claimants with an important service by helping them to collect evidence, contact former comrades, and fill out complicated forms; they also fulfilled a useful function for the federal government by completing a range of routine clerical tasks that would otherwise fall to the overworked clerks in the nation’s capital. Yet as Bentley saw it, claim agent participation in the pension system came at a cost to the government and its veterans alike. While Congress attempted to regulate the claim agency business by setting statutory limits on the fees agents could demand for their services – most recently fixed at a maximum of twenty-five dollars – claim agents were generally able to operate beyond the reach of official oversight.Footnote 28 Many, as Bentley had already discovered, brought suspicion down on their blameless clients simply by failing to follow the correct legal procedures, but many others knowingly turned their participation in the pension system to their pecuniary advantage by engaging in a profusion of petty graft and profit-seeking.Footnote 29 Moreover, Bentley worried that because claim agents were permitted to take their fees only after their clients’ claims had been approved, they might be tempted to exaggerate or fabricate claims in order to ensure their success. Combined with the Pension Bureau’s reliance upon ex parte evidence and its fee-based, localized system of medical examinations, the financial interests of the claim agency business meant that some degree of malfeasance seemed probable, and maybe even inevitable. “Not only is the door thrown wide open for the perpetration of fraud and deception,” Bentley concluded, “but every interest connected with the preparation of the case for adjudication … is adverse to the government.”Footnote 30

The commissioner was certainly not the only person to express such concerns about the pension system during these years. Many Americans worried about the wartime increase in the size of the federal government and the opportunities it seemed to hold out for corruption. In Congress, Democrats and not a few Republicans urged a policy of administrative retrenchment and fiscal restraint, while several well-heeled liberals sought honest government and moral improvement in the cause of civil service reform.Footnote 31 The Civil War pension system certainly presented plenty of worries to fiscally conservative lawmakers. Just weeks before Bentley arrived at the Pension Bureau, Kansas Senator John Ingalls, then Chairman of the Senate Committee on Pensions, had estimated that the federal government might be spending more than five million dollars every year on specious claims.Footnote 32 During the 1870s, therefore, lawmakers considered several proposals intended to cut costs and curb abuses in the pension system. Some suggested transferring the Pension Bureau to the War Department, which was believed to possess the federal government’s most efficient administrative apparatus; others suggested abolishing the federal pension agencies through which pension payments were distributed, and which were believed to exist solely to serve the demands of political patronage, and paying pensions out of a single central office instead. While Congress secured some proposed changes – such as the 1870 law that made pension payments quarterly rather than biannually – such suggestions rarely did more than provide a diversion during discussions of the yearly pension appropriation bills.Footnote 33

Yet Congress was not the only place in which the pension system might be shaped. Indeed, as Jerry L. Mashaw has highlighted, the way in which government work got done was generally a function of how agencies and departments organized themselves.Footnote 34 The Commissioner of Pensions, for example, enjoyed considerable influence over the day-to-day operation of his office, and his decisions exerted a powerful influence over the nature of the pension system as a whole. During his first year at the Pension Bureau, John Bentley made several modest adjustments in the work of his agency and oversaw the relocation of his workforce to a larger workspace which lawmakers had leased at his request.Footnote 35 The arrival of Rutherford B. Hayes at the White House in 1877, however, seemed to present the possibility of more substantial reform – especially after the new president pledged his administration to a “thorough, radical, and complete” reform of the federal civil service.Footnote 36 Not only did Hayes retain Bentley as his Commissioner of Pensions, but, by appointing Carl Schurz as Secretary of the Interior, he placed the pension system directly under the eye of one of the nation’s foremost advocates of civil service reform.Footnote 37 In Schurz, it seems, Bentley found a valuable ally. Following a meeting in April, Bentley wrote to Schurz to convey his support for his new superior’s reform-minded agenda. “The civil service is confessedly loaded down with many abuses,” Bentley asserted, “and by them rendered inefficient.” Despite the difficulties involved in creating “a system which will give this country anything like perfection in its civil service,” he believed there to be a “wide margin for improvement if apt measures are adopted to correct the acknowledged evils.”Footnote 38 During the following year, the Pension Bureau was reorganized according to new civil service rules, its clerks now being appointed, promoted, or replaced according to the quality and quantity of their work rather than their personal connections or political affiliations.Footnote 39 In May 1877, President Hayes himself enacted a significant change when he ordered that the number of federal pension agencies be reduced from fifty-eight to nineteen, a decision that he appears to have made in order to cut costs.Footnote 40 Whether Bentley regarded himself as a part of the wider movement for civil service reform is not clear, but he certainly heralded the success of these measures by appealing to the shibboleths of contemporary reformers: administrative economy and efficiency. Not only had the Pension Bureau acted on more claims during his first full year in office than it had done prior to his arrival, he explained in his second annual report, but it had done so with fewer employees and at a lower cost to the government.Footnote 41 Indeed, Bentley boasted the following year, the Pension Bureau appeared to provide a salutary case study for the “much-vexed question of reforming the departmental civil service.”Footnote 42

Digging deeper into Bentley’s administration of the pension system, moreover, suggests that these were not merely pragmatic adjustments to particular problems, but that they reflected a particular approach to the problems of governance. Many of the Gilded Age’s would-be reformers, as Richard White has noted, desired not simply a more economical and efficient administration of existing institutions, but an entirely different style of governance characterized by the centralization of authority, the removal of administration from political control, the placement of responsibility in the hands of professional experts, and the elimination of local and private influence from the business of government.Footnote 43 Certainly, Bentley seized upon the broad grants of administrative discretion contained within the pension laws. While Congress had always taken the lead in constructing the pension system, lawmakers had typically addressed the details of its administration only in the broadest strokes, thus leaving much to the discretion of administrative officials. Statutory silences on key aspects of pension law – the interpretation of the wording of the pension laws, the rating of veterans’ disabilities, the approach to be taken toward the claim agency business – meant that the commissioner could exert a considerable influence over the substantive policy.Footnote 44 Concerned about the Pension Bureau’s reliance on ex parte evidence, for example, Bentley seems to have adopted an increasingly legalistic and technically demanding approach toward the settlement of claims, effectively revising the procedures and rules of evidence involved in adjudicating claims. New claims were rejected if veterans could not specify the details of their injuries or prove they had been in the line of duty when they had received their wounds or contracted disease; hundreds of pensioners had their claims investigated and even removed from the pension rolls, whether because their injuries seemed to have originated before their enlistment or long after the war, because they were no longer believed to be disabled, or because their injuries were believed to be self-inflicted.Footnote 45 The Pension Bureau’s rates of approving claims reflected this increased scrutiny: between 1876 and 1880, the proportion of claims that were approved fell from 59 percent to 48 percent. The decline was especially pronounced in the approval rates for first-time pension claims – so-called original claims – which fell from 67 percent to 47 percent.Footnote 46

The commissioner’s authority was not limited merely to the adjudication of pension claims, however, and nor was this the only, nor the most significant, way in which he was able to determine the nature of pension policy. The Pension Bureau’s system of medical examinations was one area in which administrative action could lead to important changes. In May 1877, Bentley initiated a review of the medical examination system, ordering a trusted surgeon to reexamine almost five hundred approved claims and, without any prior knowledge of the existing rate of pension, to provide his own recommended rate. Following his examination, the surgeon recommended that almost 200 claims be reduced in value and that twenty-three be dropped from the rolls altogether. These results, Bentley argued, suggested not only that local examining surgeons were “unreliable,” but that many of them were excessively generous in their ratings; indeed, he asserted, many had used their positions “to serve their private interests … by seeking to draw to themselves, through advertisement and other means, for examination, as many pensioners as possible.”Footnote 47 Yet if Bentley initiated this investigation purely to justify his preconceptions about the liberality of localized examining surgeons, then it also reflected his ambition to establish greater central authority over the system of medical examinations. The Pension Bureau had already established some procedures for standardizing the rating of disabilities – such as appointing a Medical Referee to oversee all medical matters and issuing detailed instructions to all examining surgeons – but Bentley reinforced the authority of officials in the nation’s capital to review and revise the pension ratings recommended by local examining surgeons, even though they did not themselves attend such examinations.Footnote 48 In so doing, Bentley placed greater power in the hands of his salaried colleagues at the expense of the local examining surgeons, and, it seems, of the veterans themselves.

The commissioner reserved his most forceful interventions, however, for the claim agency business. While Congress set statutory limits on the fees that claim agents could demand, it provided little instruction on how these limits should be enforced. Bentley took a keen interest in the activities of the nation’s claim agents. While the Commissioner of Pensions was not himself vested with the power to suspend agents from practice, Bentley recommended, and secured, the suspension of scores of claim agents by referring them to his superiors for breaches of the pension laws.Footnote 49 In taking such action, Bentley was not atypical; his predecessors, too, had used the power to recommend suspension from practice as a means of regulating participation in the claim agency business. Yet Bentley intervened in the claim agency business to a much greater extent than they by taking seriously the legal requirement that claim agents submit for review all fee agreements in which they stood to receive a fee in excess of ten dollars. Indeed, Bentley asserted that, unlike his two immediate predecessors, who had generally waved through all fee agreements that did not exceed the twenty-five-dollar limit, he would exercise his “judgement and discretion” in determining the fee to be paid.Footnote 50 Frequently, he rejected fee agreements if he did not think that the claim agents’ services warranted the promised payment and returned them to the claim agent with the demand that they lower their fee.Footnote 51 Finding that such scrutiny resulted in a surfeit of paperwork, Bentley successfully lobbied Congress to pass a new law that, although removing his authority to revise claim agent contracts, also reduced the maximum legal claim agent fee to ten dollars, more than halving the profits they could hope to make.Footnote 52 While the Pension Bureau was beholden to the nation’s lawmakers to pass legislation and provide funding, therefore, Bentley’s approach to adjudicating claims, his attitude toward the medical examination of claimants, and his intervention in the claim agency business suggested that its officials still possessed some power to shape the pension system in significant, if sometimes subtle, ways.

Yet although Bentley secured considerable changes in the day-to-day administration of the pension system, he also believed that it needed something more than piecemeal and partial change. What was needed, Bentley argued, was a radical reorganization of the entire administrative apparatus – and he had just the idea. The Bentley Plan, as it might be called, was quite simple.Footnote 53 The country would be divided into several administrative districts – about sixty, he suggested – each of which would be assigned a surgeon and a clerk. Working together, these officials would oversee the entire claims-making process within their district, traveling across their assigned territory to conduct public hearings and medical examinations. Prospective pensioners would be invited to submit evidence and to call upon witnesses to support their claim, and the officials would be authorized to cross-examine them. The surgeon – a salaried official rather than a deputized local physician – would conduct medical examinations. Following the conclusion of these proceedings, the officials would send their reports to the nation’s capital, where an examining clerk would assess their findings and determine an appropriate rate of pension.Footnote 54

The commissioner advocated this idea throughout his administration. The Bentley Plan, he believed, would reconfigure the pension system in the name of administrative economy, efficiency, and expertise, benefiting both the government and its veterans alike. Countless savings would be made by adopting this new method of adjudication, Bentley explained, because of the elimination of fraudulent claims and, it followed, because there would no longer be the need to investigate such claims.Footnote 55 The Pension Bureau would also be marked by a new level of efficiency, he promised, as claims would be processed much faster by a professionalized and streamlined administrative apparatus. No longer would veterans need to employ claim agents, nor would clerks need to wrestle with the idiosyncratic ratings of local physicians; rather, the pension system would be overseen entirely by a corps of disinterested salaried officials possessed of appropriate legal and medical qualifications. Indeed, although the Bentley Plan promised to cut costs, it also anticipated a considerable extension of the federal government’s administrative capacity. As Theda Skocpol has noted, the plan represented “in effect, an effort to build up a stronger civil service organization able to conduct judicial-type proceedings,” capable of projecting the processes and standards of the federal government into communities across the country.Footnote 56

The Bentley Plan drew support from several lawmakers and would-be reformers. Both Carl Schurz and, it appears, President Hayes approved of the idea, and several legislators took a keen interest in its development.Footnote 57 In Congress, the Bentley Plan found favor among several lawmakers. When Bentley’s idea was introduced into the House of Representatives for the first time in February 1877, it came with the unanimous approval of the Committee on Invalid Pensions, and it was sent back to the committee, where it remained under active consideration. In the Senate, the Bentley Plan obtained the support of John J. Ingalls, Chairman of the Committee of Pensions, who introduced a bill based on the idea in October 1878, and which was returned to the committee for further consideration.Footnote 58 Yet there the Bentley Plan stalled. Why? Because just as Congress was considering the commissioner’s proposal, it was confronted with another plan that promised to reshape the pension system – this one from an energized and increasingly emboldened veterans’ movement.

“To Secure the Soldiers Their Rights”: The Veterans’ Rights Movement and the Statutory State

Just as John Bentley was attempting to reform the pension system from within, an incipient veterans’ movement was mobilizing to bring about changes of its own. The Union veteran was a conspicuous, if somewhat complicated, presence in the postwar United States. The federal government had mobilized more than two million men during the war, and although more than 300,000 of them had perished, most had returned to their communities in an ambiguous position; they were, as James Marten has put it, men “set apart,” not always easily assimilated back into the civilian society they had left behind, nor simply set aside at a conceptual distance alongside the honored war dead.Footnote 59 Yet far from slipping away into a decade-long “hibernation,” as Gerald F. Linderman once claimed, veterans were prominent participants in the nation’s public life almost from the moment they stacked their arms.Footnote 60 Veterans’ organizations sprang up across the length and breadth of the country in the aftermath of the war. While the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR), founded in Illinois in April 1866, would not reach its fullest extent for another two decades, it quickly established itself as the nation’s premier veterans’ organization; by 1868, it had established thirty-eight regional departments and almost three thousand local posts across the country.Footnote 61 Similar organizations emerged on a smaller scale almost wherever there existed a considerable community of former soldiers, dedicated to sustaining connections among the members of specific regiments, supporting their favored political parties, or pursuing particular political issues. Such groups took an active role in the nation’s social and political life: they were a driving force in the rituals of celebration and mourning that accompanied the war’s end; they participated in electoral contests at the local, state, and national levels; and they provided their members with the economic, social, and emotional resources with which to meet the myriad complications of readapting to civilian society. Though the GAR and many other veterans’ organizations went into decline during the long depression of the 1870s, they had already established a prominent place for the nation’s soldiers in postwar public life, and better circumstances, and perhaps particular political issues, might soon bring them back to life.Footnote 62

The Union veteran certainly represented a potentially powerful political force. Such was the number of soldiers who survived the war that their views on the federal government’s obligations to its defenders were almost certain to become a more consequential issue than ever before. Prior to the Civil War, as Brian Matthew Jordan has noted, most lawmakers were “too riveted to republicanism and its scorn for standing armies to embrace anything that approached a fixed ideology of veterans’ rights,” but the postwar period gave rise to a distinct culture of veterans’ advocacy that focused upon an incipient theory of veterans’ rights and entitlements.Footnote 63 Veterans flooded their representatives with demands for an array of benefits during the immediate aftermath of the war. “I can scarcely take up a paper,” marveled Republican Senator Benjamin Wade during the summer of 1866, “in which I do not find that the soldiers of the late army are gathering themselves together in conventions and forming leagues for the purpose of inducing the government to do them some measure of justice and equality for the services they have rendered.”Footnote 64 As Wade recognized, veterans’ organizations played a key role in advancing the peremptory claim of their members upon federal munificence. The GAR, for example, used its first annual meeting to demand an ambitious program of benefits and privileges, including land grants, preferential treatment in government hiring, and the equalization of the varied bounty payments given to recruits during the war. “Our object is not to mingle in the strifes of parties,” explained its commander-in-chief, Illinois congressman John Logan, at the organization’s fourth National Encampment in May 1869, “but, by our strength and numbers to … extract from all a recognition of our rights.”Footnote 65 The rhetoric of veterans’ rights also took root in a burgeoning number of newspapers and periodicals written by or for former soldiers. The Grand Army Journal, established in 1870, assured its readers that it would give “special attention … to all questions affecting the interests and rights of discharged soldiers and sailors,” and many other similar journals attested their devotion to veterans’ interests.Footnote 66 By seeking to enshrine an array of benefits and privileges in statute, this burgeoning veterans’ movement articulated a capacious conception of governmental responsibility and an incipient theory of veterans’ rights that would, over time, underpin the creation of an expansive veterans’ welfare state.

The Civil War pension system was the centerpiece of this expansive vision of the government’s obligations to its defenders. To many veterans, a pension carried not simply an economic significance but an ideological – even a spiritual – one. More than simply a payment for services rendered, a pension provided recognition of a soldier’s sacrifices on behalf of the nation-state; a pension was “not a gratuity,” as one veteran put it, but “a debt of honor.”Footnote 67 Veterans frequently appealed for the passage of more liberal pension legislation, whether by demanding more generous rates of pension for particular disabilities or by appealing for the rights of a wider range of service men and family members. During the 1870s, however, veterans rallied to one cause in particular: arrears legislation. Since the Civil War, the pension laws had typically included provisions that specified a period during which veterans must file their claims if they wished to receive back payments. Veterans who filed their claim within this time would, upon the approval of their claim, receive a lump-sum first payment that included back payments dating from the time of their military discharge; those who did not would receive only their regular pension payment commencing from the date their claim was approved. Veterans frequently protested the injustice of these provisions, describing a range of issues that had prevented them from filing their claims and appealing to their political representatives for help.Footnote 68 While Congress frequently granted such requests and periodically extended the deadline applied to all claims, the approach of yet another cutoff point in the middle of the decade stimulated renewed demands for legislation that would remove it altogether.

Prospective pensioners, however, were not the only ones with an interest in arrears legislation. Claim agents were especially prominent participants in this campaign. During the 1870s, the number of new pension claims had begun to slow down, and many claim agents seemingly joined the clamor for arrears legislation in the hope that it would stimulate new business.Footnote 69 The New York veteran and claim agent Robert Dimmick, for example, conducted a lengthy lobbying campaign, during which, he later estimated, he had circulated more than one hundred thousand petitions advocating for arrears legislation.Footnote 70 Most influential of all was George Lemon, another New York veteran, who had, since the war, established himself as the most successful claim agent in the nation’s capital. In October 1877 Lemon established his own newspaper, the National Tribune, primarily for the purpose of advocating for his former comrades – although it also afforded him abundant opportunities to advertise his claim agency business. “The objects of this journal,” Lemon informed the readers of his first edition, “are to secure the soldiers and sailors their rights.”Footnote 71 In his introductory editorial, Lemon declared that he intended to throw his weight into the campaign for arrears legislation, which he included as one of the “five great measures” to which his paper was dedicated, and he devoted much of his earliest front pages to an explanation of the need for such a measure (Figure 2).Footnote 72

Figure 2. “Captain George E. Lemon. From recent Photograph.” Chaplain Ezra D. Simons, A Regimental History: The One Hundred and Twenty-Fifth New York State Volunteers (New York: Ezra Simons, 1888), 258.

The campaign for arrears legislation encountered an encouraging political climate. The Democratic Party’s resurgence after 1874, as Skocpol has noted, ushered in a period of close political competition in which neither party could afford to alienate the electorally significant “soldier vote.” Despite Congressional concerns about government expenditure, therefore, the movement for arrears legislation received bipartisan support from lawmakers, who approved several proposals before they finally passed an arrears bill by overwhelming majorities in January 1879.Footnote 73 Surprisingly, however, Congress had devoted little time to discussing the likely costs of the measure, and this omission caused consternation among many journalists who accused lawmakers of imperiling the country’s financial health in order to please the increasingly vociferous veterans’ movement. “The strongest practical argument in favor of the measure,” the New York Times posited, “was, doubtless, that it was a ‘soldier bill.’”Footnote 74 When President Hayes received the bill for his signature, he immediately ordered Commissioner Bentley, Schurz, and Secretary of the Treasury John Sherman to investigate its potential costs, and, according to newspaper reports, devoted two special meetings of his cabinet to a discussion of their widely varying estimates.Footnote 75 While Hayes eventually signed the bill into law after more than a week of consultation, subsequent congressional debates over the annual pension appropriation bill revealed that the nation’s lawmakers, too, had belatedly developed their own concerns about the potential costs of the measure.Footnote 76 The Arrears Act thus heralded not simply a renewed expansion of the pension system after a period of decline, but also, as historians have recognized, reflected the growing power of the nation’s veterans to secure their special status in statute, even at a time of concern over the nation’s finances.Footnote 77

Yet if the Arrears of Pension Act represented a watershed moment for this burgeoning veterans’ movement, it was not the only way in which they made their political power felt. In addition to fighting for the statutory recognition of their rights, veterans also rallied to the defense of those rights when they seemed to be withheld or under threat. Indeed, to an extent not often appreciated by historians, the growth of the veterans’ movement during this period was driven by a politics of protest. The Pension Bureau’s difficulties in keeping up with the press of business were a constant source of frustration among veterans and their associates throughout the postwar period, and veterans frequently protested the delays involved in settling their claims, the meagerness of their pension payments, and the behavior of the unseen clerks in the nation’s capital who scrutinized their claims.Footnote 78 Just as vociferous were veterans’ responses to legislative proposals intended to reorganize the pension system in the name of administrative economy or efficiency. When Congress considered transferring the Pension Bureau to the War Department, for example, It received a flurry of protests from veterans who dismissed the necessity of any such change; in March 1876, New York Senator Roscoe Conkling declared that he had received more than two thousand petitions from veterans opposing the proposal.Footnote 79 Though they were unable to prevent President Hayes from finally taking such a step, the long-discussed proposal to reduce the number of federal pension agencies elicited a similar response. “We don’t know in whose interest the proposed change is made,” one group of veterans wrote their representative, “but we the pensioners are very sure it is not devised for our benefit.”Footnote 80 Even after Hayes ordered the reduction of the number of agencies, veterans continued to express their dismay. “There are causes and places whereby the United States can study the art of economy,” one group complained, “but they should not commence on the poor cripples of the late war.”Footnote 81

Such protests also suggest that this burgeoning veterans’ movement was shot through with ambivalence about, or even antipathy toward, administrative officials. When John Bentley took charge of the pension system, for example, his narrow interpretation of the pension laws, his demanding evidentiary standards, and his legalistic approach to the adjudication of claims drew a heated response from veterans who challenged the legitimacy of administrative rulings that they saw as an abrogation of the rights they had won on the battlefield. In the National Tribune, George Lemon excoriated the “dominion of red tape” by presenting poignant examples of veterans – including survivors of the notorious Confederate prisoner of war camp at Andersonville – whose claims had foundered due to their inability to provide sufficient evidence, or who had died before their cases had been settled. Such examples, Lemon informed his readers, highlighted the “cruelty” of the Pension Bureau’s “miserable slavery to routine.”Footnote 82 Many veterans expressed their concerns by complaining to their congressmen about the administrative rulings that seemed to defeat the purposes of the pension laws. The Commissioner of Pensions, one veteran wrote, had “manifested a desire to wrong the soldier who is duly and justly allowed a pension under our pension laws by his unwarranted actions.”Footnote 83 Writing from Michigan, a trio of veterans complained that they knew of many claimants who had been waiting for upward of three years for the settlement of their cases, but who had suffered as a result of the new scrutiny being applied to claims. “There is many that wants and needes their pension and feel as if the Solgers who fought for our country and for their rites should have them,” they informed their congressman, demanding that he uphold “the rites of the solgers and not mr Bentleys [sic].”Footnote 84 While such criticisms doubtless expressed the personal frustrations of aggrieved and desperate claimants, they also reflected an abiding antipathy toward a style of administration that seemed arbitrary, excessively technical, and unresponsive to the needs of its intended beneficiaries. Writing to Carl Schurz following the rejection of one client’s claim, one claim agent warned that there existed “very general and, certainly in many cases, well-grounded complaints by soldiers and their heirs at the arbitrary and autocratic rulings” then being issued from the Pension Bureau.Footnote 85

The commissioner’s most vocal critics, in fact, came from among the ranks of the nation’s claim agents. Throughout Bentley’s administration, George Lemon and his fellow claim agents chafed against the commissioner’s intervention in their affairs, especially the new scrutiny to which their fee agreements were subjected. The Commissioner’s intervention in matters of private contract between claim agents and their clients, one wrote, represented “a usurpation and a violation of the clearest principles in law.”Footnote 86 Many claim agents turned their frustration at the scrutiny of their personal businesses into a broader argument about this new demonstration of administrative discretion. Writing to Carl Schurz in June 1877, the New York attorney Ernest Brook protested Bentley’s refusal to sanction one recently submitted fee agreement by describing the problems presented by his “assumption of discretionary powers.” Though each Commissioner had taken his own approach to administering the pension system “under the fancied discretion vested in him by law,” Brook argued, Bentley’s interpretation of his duties was “erroneous,” and had led him to assume responsibilities that lay “outside of the duties of his office.” The Pension Bureau, Brook suggested, now seemed to be administered according to “no law but the ungoverned, unlimited will of one individual.” Rather than simply administering the pension laws, Brook argued, Bentley seemed to have assumed the power to make the laws for himself. “It resolves itself into a simple conjecture,” he concluded, “as to whether the Commissioner makes the law, or the law makes the Commissioner.”Footnote 87

Protests against Bentley’s administration thus reflected not simply the grievances of veterans and claim agents but also revealed their ideas about how the pension system should be administered. George Lemon captured the essential elements of this vision in a May 1878 editorial titled, “What is the Object of the Pension Bureau?” Presenting his own interpretation of the pension laws and the agency tasked with their administration, Lemon revealed his belief in a style of governance that was characterized by the rote distribution of benefits set in statute. The Pension Bureau, Lemon asserted, had been “instituted solely for the benefit and advantage of the soldiers and sailors of the Republic,” founded in order to implement the laws forged by the nation’s legislators and not to make laws of its own; rather, it was simply supposed to administer the pension system according to the “natural intent and meaning” of the pension laws as they had been constructed by the “generous and sympathetic legislative bodies who recognized the obligations of the nation.” Yet Commissioner Bentley, Lemon argued, had grafted his own administrative rules upon the laws without any legislative oversight. “Day after day his rulings become more arbitrary and unreasonable, more technical and less equitable,” Lemon argued, and, as a result, “the avenue to the national bounty” had been “closed … by limitations not in the law.” The Commissioner’s attempts to overhaul the Pension Bureau’s administrative apparatus epitomized his refusal to confine himself to the rote fulfillment of the pension laws and revealed that he had policymaking pretensions of his own. The commissioner was not “content to do common-sense business in a common-sense way,” Lemon argued, “but wants to be considered an originator.” Indeed, he went on, Bentley’s administration reflected a worrying tendency toward centralized, personalized power, showing that he wanted to “superintend, determine, control, and decide, from headquarters in Washington, all matters which pertain to his duties.”Footnote 88

While Lemon’s criticisms reflected his own opposition to Bentley’s administration of the pension system, therefore, they also reflected his broader conception of how the pension system, and indeed, the federal government, should operate. Whereas Bentley seemed to stand for a style of governance characterized by centralized authority, discretionary power, and a tendency toward bureaucratic policymaking, Lemon stood for an alternative style of governance that secured the rights of the nation’s soldiers in statutes forged in the national legislature.Footnote 89 The Pension Bureau, he seemed to suggest, should be almost entirely clerical in function, confined to the rote – or, as he put it, common sense – assessment of pension claims, the distribution of pension payments, and the approval of claim agents’ contracts. In 1880, the conflict between these two visions would come to a head.

What is the Object of the Pension Bureau? The Select Committee on the Payment of Pensions, Bounty, and Back Pay

By 1880, the Civil War pension system was at a crossroads. Just two years earlier, it had seemed to be in decline, as the number of names on the pension rolls had gradually begun to go into reverse. The Arrears Act, however, had triggered an explosion in the number of new claims from men and women who were desperate to receive the considerable lump-sum first payments held out by law. The Pension Bureau received more than twenty thousand claims for arrears of pension during the month following the passage of the act, and, as Commissioner Bentley wrote later that year, veterans’ claims had come in at an “unprecedented rate” – more than double the rate, in fact, of any year since 1873. By 1880, the number of names on the pension rolls had exceeded a quarter of a million for the very first time, and the total cost of the pension system was more than double what it had been two years earlier.Footnote 90 This sudden influx of new claims, however, had also underlined the problems that had long since plagued the administration of the pension system. The Pension Bureau’s workers struggled to keep pace with the growing backlog of claims, its filing system broke down, and officials worried about their inability to catch the claims of fraudsters who were motivated by the prospect of receiving a significant lump-sum first payment.Footnote 91 While the Arrears Act seemed to herald the renewed expansion of this veterans’ welfare state, therefore, it also shone new light upon its uncertain administrative foundations.Footnote 92

The Pension Bureau’s problems soon drew the attention of the nation’s lawmakers. In January 1880, the House of Representatives established the Select Committee on the Payment of Pensions, Bounty, and Back Pay in order to conduct a comprehensive review of the pension system. During the following year, seven representatives investigated almost every aspect of the pension system. They assessed the methods involved in adjudicating claims, the nature of evidence required to establish a claim, and the measures taken to combat fraud. They also held hearings with those who had firsthand experience with the pension system, including officials and claim agents, and attended to a mass of correspondence from disgruntled pension claimants. While some Republicans suggested that the Select Committee was nothing more than a political ploy instigated by the Democratic-dominated House for the purpose of digging up material for use in that year’s presidential campaign, the representatives were also tasked with considering the necessity of change in the pension system, both with recommending “such additional legislation as may correct existing defects” in its administration and with considering any measures that “may be deemed necessary to protect the pensioners and soldiers of the government in their rights.”Footnote 93 More than merely a response to recent developments or a political ploy, therefore, the Select Committee could be considered a culmination of the twin trends that had driven debates about the pension system throughout the previous decade: between those who asserted the need for reforming its administrative apparatus, on the one hand, and those who sought to secure the soldiers’ rights, on the other.

The Select Committee certainly dedicated considerable time to considering the necessity for reform. As Commissioner of Pensions, John Bentley appeared before the Select Committee on several occasions, and just as he had in each of his annual reports, he declared that his administration had brought about a considerable improvement in his agency’s “industry, diligence, and efficiency.”Footnote 94 The Chiefs of the Pension Bureau’s adjudicating divisions were unanimous in their support. The Chief of the Pension Bureau’s Ohio Division, who had worked at the bureau for more than a decade, assured the committee that the agency was “in better working condition today and is doing more work than at any time since I have been in the office.”Footnote 95 Yet as Bentley acknowledged, the Arrears Act had presented a whole host of problems. The Pension Bureau had been “swamped” by new claims, he explained, and he had been forced to establish a relay of clerks, working around the clock, to overhaul the agency’s creaking filing system. The expansion of business, Bentley went on, had also exacerbated the problems that he had identified in the administration of pension claims, especially as the significant lump-sum first payments now promised in law seemed to incentivize the presentation of speculative or even fraudulent claims.Footnote 96 Once again, therefore, Bentley advocated the need for an overhaul of the existing administrative apparatus – and he had some reason to hope for success. Not long after the Arrears Act had passed, Kansas Senator and Chairman of the Committee on Pensions John Ingalls had again introduced a bill modeled on the Bentley Plan as “an effort in the direction of economy and reform,” and although it had been deemed too radical to consider in the few days then remaining of the session, it had generated interest among his colleagues and had remained under active consideration by his committee ever since.Footnote 97 The Select Committee thus provided Bentley not only with an opportunity to justify his administration of the pension system but also to make the case for his far-reaching reforms.

The commissioner’s claims, however, were offset by the arguments advanced by others with experience of the pension system, and not least by its intended beneficiaries. The Select Committee received hundreds of letters from men and women across the country, almost all of them complaining about their experiences with the pension system. Most held Bentley himself to blame, suggesting that he had been swayed by the demands of his superiors to cut costs and purge the pension rolls. Many drew attention to the significant delays in settling cases. Writing from Ohio, one veteran complained that he had first applied for a pension more than six years earlier but had, since then, heard nothing about the condition of his claim. “I have furnish all the profe I have bin cold on for as yet,” he explained, and the lack of further action must be “the folt [fault] of the department or the folt of J.A. Bentley.”Footnote 98 Many complained about the Pension Bureau’s demanding evidentiary standards, especially given the difficulties of proving definitively that their disabilities had been incurred in the line of duty. The complaint of one New York veteran, O. B. Scott, was characteristic; he had, he lamented, “struggled, toiled, and labored with all my faculties” to assemble enough evidence to support his claim, but it had all been to no effect. The Commissioner of Pensions, he complained, “evades, wriggles round – perverts and misconstrues testimony which is plain … There is no lack of law nor testimony,” he concluded; “the lack is in the head and brains of the Comm[issione]r.”Footnote 99 Many correspondents couched such complaints in the language of veterans’ rights. According to one Ohio veteran, Bentley’s administration represented a “gross insult to … veterans,” and constituted “an effort to rob them of their rights.” The Select Committee, he urged, should take immediate steps to “protect the pensioner in his rights.”Footnote 100 Some perceived Bentley’s administration as an example of an emerging and worrisome style of governance that threatened the nation’s political principles. The Pension Bureau, one New Yorker asserted, reflected the extent to which “bureaucracy has established its thorn here in this our Republic by injustice, arbitrariness, and despotism.”Footnote 101

The Select Committee heard the most passionate denunciations, however, from the claim agents it invited to share their views. Perhaps inevitably, George Lemon, as the most successful claim agent in the capital, was invited to give evidence, and he seized upon the opportunity to share his opinion of the man he had taken to calling, in the pages of his newspaper, the “arch-enemy of the soldier.”Footnote 102 Together, Lemon and some of his erstwhile business rivals – including the New York claim agent George Van Buren and the Washington agent Charles King – advanced a comprehensive critique of Bentley’s administration. Since Bentley had taken charge of the Pension Bureau, they all agreed, it had become harder than ever to secure the passage of their clients’ claims. “The Commissioner cannot settle cases,” asserted Van Buren, “does not intend to settle cases, and will not settle cases.”Footnote 103 When Lemon spoke before the assembled representatives, he recited what was, by now, a familiar litany of complaints. The commissioner, he asserted, had “piled rule upon rule and regulation upon regulation” until the process of making a claim had become “difficult, involved, and insecure” than ever before. The Pension Bureau’s problems, he insisted, were, in short, “defects of administration, not of the law – faults of the officer, not of the system.”Footnote 104

Yet as Lemon and his fellow claim agents criticized John Bentley’s administration of the pension system, they also spoke to broader antipathies rooted deep in the nation’s political culture. The commissioner was behaving like an autocratic monarch, they argued, running his agency as a kind of “star chamber” by issuing arbitrary and unjust rulings and suppressing the rights of individual citizens by dropping pensioners from the rolls without warning and intervening in matters of private contract. The New York claim agent George Van Buren drew a more contemporary parallel, informing his audience that many of his clients believed themselves to be victims of a “species of lynch law.”Footnote 105 The Commissioner of Pensions, Lemon reminded his audience, already possessed “wonderfully large” powers. He was able to “allow or reject any claim, he can postpone, delay, require new evidence, and repeat his requisition without limit. He can wear out all human patience by substantial or frivolous objections. He can fix, alter, change, and modify the character of proof he will require, and the classes of witnesses to make such proof, at his simple whim or caprice. He can find good excuses for any amount of delays, or he can decline to give any excuse. He can send agents with secret instructions, whose reports are confidential, and cut off pensions when he likes. He can strike from the rolls of practicing attorneys any one who deals falsely with his client or the government, and at his will can purge the practitioners before his court.” “These,” Lemon concluded, “would seem to be powers enough for any one man to possess.” Yet still, he went on, Bentley was not content. The commissioner’s policymaking pretensions, Lemon suggested, represented nothing more than an attempt to consolidate and institutionalize his authority. Through the Bentley Plan, Lemon alleged, Bentley was endeavoring to “increase his jurisdiction, patronage, and power, and make him[self] more completely master of the situation.”Footnote 106 In so doing, Lemon and the other claim agents argued, Bentley was far exceeding the powers vested in him under law. Stressing the “great importance of confining officials strictly within the limits laid down in statute,” Charles King urged the assembled representatives to rein in the Commissioner or risk undermining the liberal principles that purposefully divided and dispersed power. “There is a great danger to this whole government,” King warned, “from the disposition inherent in mankind to overstep the boundaries of their jurisdiction.”Footnote 107 The Commissioner’s administration, the claim agents thus warned, comprised not simply an insult to the nation’s veterans, but a danger to its entire system of government.

The ongoing debate about the Pension Bureau spilled over into that year’s presidential election. During the 1880 campaign, Republicans and Democrats hoped to appeal to the soldier vote, and the furor over Bentley’s administration meant that the pension system was an important issue. Many Republicans feared that the controversy might lose them the votes of a significant number of Union soldiers. Writing to the Republican candidate James A. Garfield in July, Edward McPherson, Secretary of the Republican National Committee, warned that “the soldiers” had become certain “that Bentley is [against] them” and would be “resentful at the Administration which retains him,” as would several prominent claim agents, one of whom had already “gone over, body and breeches” to the Democratic Party.Footnote 108 Yet Garfield did not need to be told. Throughout 1880, he received scores of letters from veterans and claim agents urging him to declare his intention to dismiss Commissioner Bentley or risk losing their support. Writing from Michigan, one member of the local Soldiers and Sailors Association asked whether Garfield could promise to remove Bentley from office should he be elected, suggesting that there were “eleven thousand soldiers” in the state whose vote depended upon his answer; “there is not a soldier in this town,” another veteran wrote, “that would vote for any man that would keep him [Bentley] in office.”Footnote 109 The Democratic Party did its best to capitalize upon such sentiment, devoting a portion of its campaign textbook to the investigation of the pension system, highlighting the continued delays in settling pension claims, the dismissal of claimants from the pension rolls, and the downward revision of the disability ratings recommended by local examining surgeons. “The Union soldiers need only read the record evidence of this investigation,” they concluded, “to be convinced that a change of administration is needed to give them the tardy justice they have been so vainly striving to obtain.”Footnote 110

The narrow Republican victory at the polls might have suggested that the rumors of veterans’ widespread defection from the party had been overstated, but it did not ease the pressure on the embattled Commissioner of Pensions. While Garfield prepared to enter the White House in early 1881, he continued to receive letters urging him to appoint a new man, preferably a soldier, to administer the pension system.Footnote 111 Before Garfield could act, however, the Select Committee issued a judgment of its own. Having scrutinized the Pension Bureau for more than a year, the committee had come to conclude that its management depended “largely upon the personality of its chief.” It would be “vigorous and efficient, or unsatisfactory and weak,” they suggested, “according to the energy and capacity of the Commissioner.” Indeed, because the commissioner was vested with a “wide discretion and [an] abundance of power,” they explained, the officeholder had “the special and serious responsibility” of ensuring that his duties were “well and faithfully performed and that the law regulating the subject of pensions be honestly and fairly administered” – and Bentley, they implied, had failed in both respects. More than merely censuring Bentley, the Select Committee proposed that measures be taken to oversee the administration of the pension system, suggesting that the committee be made permanent and that a board of appeals be established to review the commissioner’s rulings. Though the latter proposal was rejected, such recommendations represented an attempt to dilute the commissioner’s powers by hedging the office with more robust forms of administrative oversight and legislative review.Footnote 112

Despite Bentley’s insistence on the need for wholesale reform, moreover, the Select Committee concluded that no major changes were necessary to ensure a “full, fair, and expeditious” administration of the pension system.Footnote 113 In fact, their Congressional colleagues had already dismissed any major changes to the pension system. By 1881, the Bentley Plan had lingered in committee rooms for almost five years, and although it found favor among committee members, the bills they presented based upon the idea rarely came up for debate; indeed, just a few weeks earlier, the Senate Committee on Pensions had reported favorably on a bill that embodied its essential elements, but the proposal was swiftly tabled, and a last-ditch attempt to rescue the proposal by attaching it to the annual pension appropriation bill was flatly rejected, as it turned out, for the very last time.Footnote 114

Despite the Select Committee’s assessment and the pressure on Garfield, Bentley remained in office – for a time. Yet although Bentley earned Garfield’s respect for his administration of the pension system, and although he enjoyed the enduring support of his state’s congressmen, political considerations made his departure seem almost inevitable.Footnote 115 Writing to Senator Philetus Sawyer of Wisconsin in June 1881, Garfield explained that, despite his high regard for the Commissioner, the “state of public feeling” meant that it seemed likely that “the opposition will keep the office in turmoil until a change is made.” Later that day, Garfield requested the Commissioner’s resignation, and Bentley reluctantly complied.Footnote 116

Conclusion

When John Bentley departed the Pension Bureau, the prospect of significant structural change in the pension system seemingly went with him. Though Bentley regarded his administration with pride, he was pessimistic about the possibility of future reform. Writing to Carl Schurz, Bentley expressed his regret that it had become “necessary to imperil the early consummation … of the reforms in the pension service which seem to be demanded both in the interests of the meritorious claimants and of the government.”Footnote 117 Some would-be reformers lamented the departure of an official who had administered the pension system with an eye to administrative economy and efficiency, attributing his removal to the political imperatives of the patronage system and the power of private interests. The liberal Springfield Republican assured its readers that Bentley had earned “an enviable reputation” in an “onerous and difficult office,” and lamented that the failure of his most ambitious proposals for the pension system had all but ensured the extension of its anachronistic administrative apparatus. “With the usual happy-go-lucky methods of American administration,” the Republican explained, “the pension office is still in theory and system what it was in fact before the war: a small subordinate bureau engaged in paying off, as mere clerical work, the sums due pensioners on the rolls.”Footnote 118 Many others, however, were delighted at Bentley’s resignation. In the National Tribune, George Lemon rejoiced at his adversary’s departure and proclaimed his optimism about the future of the pension system. “The reign of bitterness and prejudice is over,” he crowed, “the reign of justice and fulfilment of the law … has begun.”Footnote 119

While Bentley might be almost unknown to modern historians of the late nineteenth century, therefore, contemporaries were in little doubt that his administration of the pension system represented a constitutive period in the history of the pension system. Following the Arrears Act, the pension system assumed new proportions as the pension rolls expanded and its costs soared upward; by 1889, there were almost 500,000 names upon the federal pension rolls, and the cost of the system had risen to almost $90 million.Footnote 120 Yet almost as significant as what did happen during this period was what did not. The Arrears Act certainly represented an important turning point for the pension system, but it was not the only path it might have followed during these years. The Bentley Plan, for example, proposed a radical reworking of the pension system, one that would have transformed its existing administrative apparatus. That it failed underlines the keenly contested character of postwar state-building and the coexistence of competing conceptions of political authority and expansive governance: one that demanded a centralized and professionalized administrative apparatus vested with broad grants of discretion, the other holding out federal largesse through a widely spread but loosely woven tapestry of localized, fee-based governance. Indeed, far from representing a footnote in the story of an insistently expanding veterans’ welfare state, this story of suppressed state-building underlines the paradoxical significance of the pension system. Despite its considerable size and scope, the pension system was significantly shaped by the constraints of nineteenth-century political culture, reflecting not only the federal government’s power to distribute resources into the hands of politically powerful interest groups but also an abiding antipathy toward centralized administrative power; the pension system, as Brian Balogh has identified, came to reflect a “tension between popular support for a vaguely defined sense of obligation to the nation’s veterans and the limited administrative apparatus Americans were willing to construct in order to fulfill that obligation.”Footnote 121 The pension system was not, therefore, simply the symbol of an increasingly generous and powerful postwar state, but rather the product of postwar debates about what that state should be; debates that produced, in the words of one historian, a transitional “second state,” between the republican state of the nation’s early decades and the administrative state of the twentieth century.Footnote 122 Indeed, if the pension system symbolized the new and expanded responsibilities assumed by the federal government in the wake of war, then it also offered a striking example of the government’s enduring administrative ambivalence.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Gary Gerstle, Lewis Defrates, David Schley, Emma Teitelman, Kevin Waite, and the members of the North American History Research Group at Durham University, as well as the anonymous reviewers of JGAPE, for their close reading and comments on an earlier version of this article. Research for this article was supported by funding from the Arts and Humanities Research Council (Grant Reference AH/L503897/1).

Data access statement

No new data were generated.

Competing interests

The author declares none.