To the Editor—Hospital-acquired infections (HAIs) impact many hospitalized patients, and they have a high mortality rate. HAIs cost the US healthcare system billions of dollars every year. Active resistors and organizational constipators are in leadership positions and resist change. They often block and delay the adoption of best practices, which save money and lives.Reference Bearman and Stevens1

A strategy to overcome active resistors is to present scientific evidence supporting new practices. The use of standardized central-line bundle kits (SCLBKs) is an infection prevention program that has proven to reduce central-line bloodstream infections (CLABSIs).Reference McMullan, Propper and Schuhmacher2 Bathing patients with a 2% chlorhexidine gluconate (CHG) solution reduces annual CLABSIs and catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTIs).Reference Reagan, Chan and Vanhoozer3 We have shown that delays in implementing and increasing CHG compliance results in additional HAIs and costs.Reference Reagan, Chan and Vanhoozer3 Here, we focus on the delay of implementing SCLBK and CHG bathing on CLABSI and CAUTI infections. We calculated the impact of active resistors and organizational constipators on these infections over 5 years, and we present a cost analysis.

Methods

Model structure

A discrete-time Markov chain model was implemented in MATLAB to simulate patients moving through different patient classes. We defined 4 classes: patients with a central line, patients with a Foley catheter, and patients with both, and patients with neither. Patients with central lines may acquire CLABSIs, and patients with Foley catheters may acquire CAUTIs. The distribution of patients depends on the class they were in previously. The next day’s distribution was calculated using the following formula:

where B is a transition matrix that represents the probability of getting CHG bathed or obtaining a SCLBK, I is a transition matrix that represents the probability of getting an infection, P is a transition matrix that represents the probability of obtaining a catheter or central line, and D is a transition matrix that represents the probability of being discharged. Patients with CLABSI or CAUTI may develop a secondary infection of the other type. Each day, if a patient does not acquire an infection or an intervention, the patient moves to the i + 1 version of the same class.

The patient’s average length of stay, 1/δk, differs for each class k. The daily probability of getting an intervention p, ρ p , was calculated using the following formula:

where K represents the percentage of hospitalized patients with intervention p.

The infection rate, r, was calculated based on a compliance rate of 60% for CHG bathing and by number of days since last intervention. Here, η and κ are the reduction of incidence of CAUTI and CLABSI due to CHG bathing and CLABSI due to SCLBK, respectively, and were pre- to postintervention incidence.

Model inputs

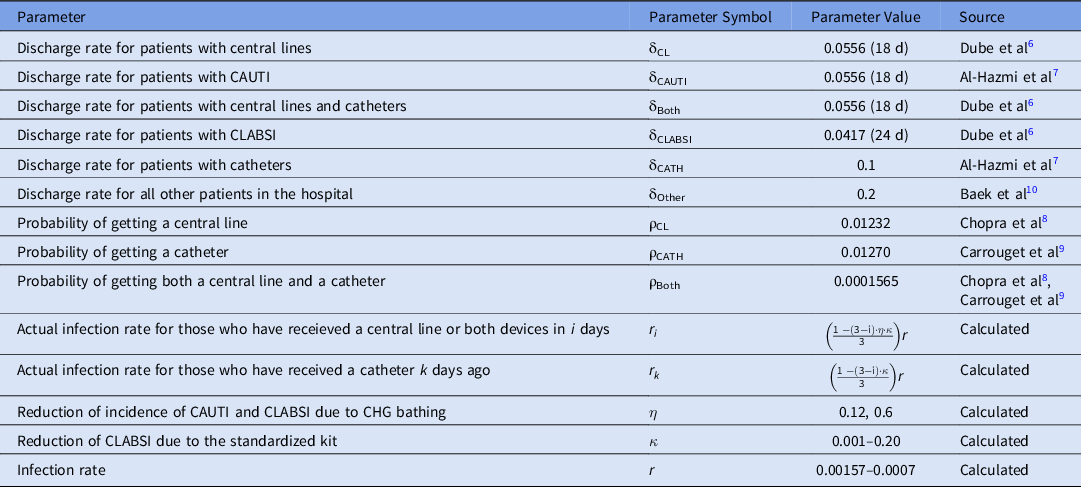

Virginia Commonwealth University Health System is an 865-bed academic medical center with 65,000 patient discharges estimated annually. Prior to SCLBK and CHG bathing interventions, there were 80 CLABSIs and 39 CAUTIs annually. The daily number of patients used in the simulations was 850 patients.Reference Reagan, Chan and Vanhoozer3 The probability of a patient developing a CAUTI was 0.1257 per 1,000 patient days and 0.2579 per 1,000 patient days for a CLABSI. Simulation results were calculated at steady state. Parameter values are listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Parameters Used in the Simulations

One CHG bath costs $8.47. Patients who do not receive a CHG bath on a given day are assumed to receive a bath with non-CHG wipes that cost $2.47 per bath. The noncentralized central-line bundle costs $0.04 more due to the compilation of necessary supplies needed to insert a central line compared to the SCLBK. On average, a CAUTI infection costs $13,7934 and a CLABSI infection costs $70,696.5 The total cost calculation included costs related to CHG bathing materials for CAUTI, the SCLBK for CLABSI, and the costs associated with HAIs.

Results

Implementation of CHG bathing and SCLBK, and the associated costs, were simulated to be initiated in increments of 6-month delays and were compared no implementation over 5 years. Overall, as the delay in implementation for the infection intervention programs increased, the number of HAIs increased, and the associated savings in healthcare costs by implementation decreased.

Every 6-month delay in improvement of CHG bathing compliance resulted in ∼11 preventable CAUTIs and an additional cost of $11,000. Every 6-month delay in implementing the SCLBK resulted in ∼10 CLABSIs and an additional $715,000 in costs. Overall during the 5-year period, 102 CLABSIs and 105 CAUTIs could have been prevented, with a savings of ∼$7.2 million through CLABSI prevention and $115,000 through CAUTI prevention.

Discussion

Delaying implementation of infection prevention initiatives leads to increased HAIs and total associated healthcare costs. If there are better intervention strategies that are more expensive, they may end up saving money in the end. When the SCLBK and CHG bathing are immediately implemented, healthcare systems can prevent ∼200 HAIs per year. Each monthly delay leads to decreases in total associated healthcare savings. Lower overall savings for CAUTIs was due to the $6.00 difference with the implementation of CHG compared to a $0.04 difference for SCLBK. Also, the healthcare costs dealing with a CAUTI were lower than for CLABSI.

The role of active resistors and organizational constipators in implementing CHG bathing and the SCLBK has a dramatic impact on hospital costs and patient outcomes. Our model was limited by assumptions, such as not including educational and monitoring costs, but it allowed for predictions and quantitative analysis of immediate or delay in implementation of CHG bathing and SCLBK and their effects.

Financial support

No financial support was provided relevant to this article.

Conflicts of interest

All authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.