Research on the large industrial enterprise and its role in individual countries goes back to the 1970s, when a group of doctoral students at the Harvard Business School (HBS) built on Chandler’s Strategy and Structure to examine the characteristics of these enterprises in the United States as well as several Western European economies.Footnote 1 Rumelt’s now-classic work was a path-breaking study on US enterprises, while Channon’s research focused on the case of Great Britain.Footnote 2 These publications were followed by similar work on France and Germany by Dyas and Thanheiser and on Italy by Pavan.Footnote 3 Other than Rumelt’s study, which included samples from Fortune 500, those on Western Europe were all based on identifying the 100 largest manufacturing firms in a country and then examining Chandler’s thesis about the relationship between diversification and multidivisional structure (the M-form).

Following the Visible Hand, again on big business in the United States, Chandler’s interest turned toward Western European advanced economies.Footnote 4 Then came his comparative study on the United States, Great Britain, and Germany.Footnote 5 Other researchers continued focusing on these countries to revisit and to update prior research along Chandlerian lines.Footnote 6 It was with the appearance of Big Business and the Wealth of Nations that Chandlerian concerns were extended not only to other countries in Western Europe (e.g., Spain) but also in Eastern Europe (e.g., Union of Soviet Socialist Republics [USSR]) as well as “late industrializers” in East Asia and Latin America (Japan, South Korea, and Argentina).Footnote 7

Despite the recognized significance of this line of research on the large industrial enterprise, similar investigations in late-industrializing countries have fallen behind, much like business history at large.Footnote 8 This lag has had to do mainly with difficulties in obtaining reasonably accurate historical or even recent data on individual enterprises in these countries. A major source of this hurdle has been the predominance of family ownership among large enterprises, which are not required to disclose financial and operational information. Available data are therefore often confined to firms that are listed on national stock exchanges.

Nevertheless, influential work, particularly on big business in East Asian countries began to emerge in the late 1980s and the 1990s, expanding further in the last couple of decades or so.Footnote 9 Diverging from the Chandlerian paradigm, these studies have consistently shown that “business groups” have been the predominant organizational form of big business in late-industrializing countries.Footnote 10 Defined typically as “consisting of legally independent firms operating in diverse industries,” the central concern in business group research has been the performance of affiliates relative to stand-alone firms, as well as the influence of institutional conditions on their prevalence, strategies, and structural features.Footnote 11 Descriptive studies have also appeared on large business groups in several Asian, Latin American, and Middle Eastern countries.Footnote 12 However, most of these surveys have been cross-sectional, relying on data for the recent past in listing the largest business groups in a country, and providing information on their characteristics such as age, size, number of affiliates, diversification, and family ownership. Only a few of these studies have included a temporal dimension.Footnote 13 More generally, longitudinal research on large enterprises in late-industrializing countries remains scarce. Chittoor and Aulakh’s review of the large Indian enterprises, though only covering a period of 20 years (1990–2010), and Lluch and Lanciotti’s historical study on big business in Argentina constitute the few recent examples in this tradition.Footnote 14

The present study aims to add to this scant international literature by providing the first systematic study of the large industrial enterprise in Turkey. Although some prior research does exist on Turkish business groups, no longitudinal research has appeared to date on the evolution of Turkey’s largest industrial enterprises.Footnote 15

Turkey presents a distinct case for several reasons. First, while achieving significant growth since the 1950s, the country has not developed into one of the “miracle economies” often attributed to East Asia, nor experienced the rapid economic transformations seen in parts of Southern Europe.Footnote 16 Second, although large businesses mainly in the form of diversified family business groups (FBGs) already emerged in the country in the 1960s and the 1970s, they lagged behind in becoming major international players.Footnote 17 Third, Turkey saw a return to a new form of state intervention led by the sociopolitical ideology of a government that rose to power during the later phase of its post-1980 shift from state-directed, import-substituting industrialization (ISI) toward economic liberalization and internationalization. The severe economic crisis of 2001 and the ensuing stabilization program further led to the creation of several autonomous regulatory bodies. The subsequent ascendance of the new political party to power ushered in a strong privatization drive. However, in the following years, reversals in pro-market reforms appeared, as the government increasingly exhibited centralist tendencies, reducing the independence of institutions such as the Central Bank and introducing selective state intervention, often favoring businesses aligned with its pro-Islamic ideology.Footnote 18

The present paper draws on data compiled from various archival sources on the 100 largest Turkish industrial enterprises over a 40-year period (1970–2010). We identify three stages in the politico-economic context of business activity during this timeframe: the late ISI era of the 1970s, the first phase of post-1980 liberalization, and a second phase following the 2001 economic crisis and the rise of a new government. In examining the trajectory of large enterprises, we focus on ownership, organizational form, and industry distribution.

Our study makes two main contributions: First, we demonstrate the outcomes of Turkey’s shift in the early 1980s toward greater economic liberalization and internationalization. Our central finding is that, with this shift, the composition of largest industrial enterprises in the country has evolved from the prior balanced presence of stand-alone family businesses, affiliates of FBGs, and state-owned enterprises (SOEs), toward a new configuration made up mainly of FBG affiliates and, to a lesser degree, subsidiaries of foreign firms. These findings highlight how not only economic but also political and societal factors have shaped the development of Turkey’s largest firms. Second, and more generally, we show that the family business group, which emerged as a main organizational form during state-directed, import-substituting industrialization has not only persisted but even expanded despite greater liberalization and internationalization. We account for the growing dominance of FBGs and their affiliates despite market-oriented reforms by pointing to liberalization- and privatization-driven opportunities, FBGs’ accumulated strengths, and the advantages given to entrepreneurs closely linked to the ruling government.

The article is structured as follows: In the next section we provide an historical overview of the politico-economic context of industrial activity from its origins in the late stages of the Ottoman Empire and through the initial three decades of the post-1923 Republican Turkey. The subsequent section begins with the 1950s and extends the review through the 1960s and into the period from 1970 to 2010. We then discuss and describe the three key dimensions (ownership, organizational form, and industry distribution) that we use to examine the composition of the largest industrial enterprises in Turkey during the 1970–2010 period. The following section details our archival sources and methodology for compiling the data. We then present the results of our analysis. The last section discusses our findings and concludes.

From Ottoman Times to the Mid-Twentieth Century

As the Ottoman Empire began to experience the adverse effects of the industrial revolution in Europe, there were some state-led initiatives in the 1840s to create manufacturing enterprises. However, these enterprises turned out to be short-lived, with only a few of them surviving by the end of the decade.Footnote 19 While some additional enterprises were established during the latter part of the nineteenth century, it was the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP; also known as the “Young Turks”), which rose to power after the restoration of the constitutional regime in 1908, that was set to create a “capitalist society” and a “Turkish entrepreneurial class” within a “national economy” framework.Footnote 20 Construction of a national business class during the reign of the CUP (1908–1918) centered around Muslim Turks at the expense of non-Muslim ethnic groups (mainly Armenians and Greeks) as well as foreigners. This ideology developed in response to the dominance of non-Muslim minorities in the ownership of relatively larger enterprises and commercial activity more generally in the Ottoman Empire, partially due to trade agreements with European powers and the capitulatory regime, which disadvantaged the Muslim population. A broad range of inducements were provided with the aim of creating an indigenous industry, such as tax and customs duty exemptions as well as free allocation of land and private–public partnerships in which CUP members took the opportunity to become involved as founders.Footnote 21 The CUP policy of creating an indigenous business class did pay off to some degree. Available data on industrial enterprises in Istanbul indicate that, right after the founding of the Turkish Republic in 1923 following the demise of the Ottoman Empire, ownership by Muslim and non-Muslim Turkish citizens were almost on par, and foreign ownership remained very limited.Footnote 22

Thus, the new Republic did inherit some industrial activity from the Ottoman Empire. In its early years, the single-party regime established with the founding of the Republic aimed to pursue a “liberal economic policy,” based on the belief that the private sector would take the lead in economic development.Footnote 23 Yet, private capital was scarce, and investment did not materialize at the scale that had been hoped for. Landowners were not particularly active either, partly because of lack of capital and partly owing to the lack of enthusiasm by the Republican elites in the involvement of landed entrepreneurs, as the latter were viewed as symbols of the old regime.Footnote 24 Neither was there any foreign direct investment forthcoming.Footnote 25 The onset of the Great Depression made matters worse, as it had dramatic adverse effects on Turkey’s foreign trade and economy at large.Footnote 26

It was within this context that there was a radical shift in economic policy, as the state again entered the picture in the early 1930s, taking over the lead within the framework of a “five-year industrialization program,” and the country moved toward what came to be referred as the “étatist” period.Footnote 27 This turn was not because of ideological reasons but as a pragmatic solution to the conditions at hand.Footnote 28 Several SOEs were formed initially in manufacturing and banking before expanding into various other sectors. Some of these enterprises in fact took the form of “business groups,” as they operated across a broad range of industries, including areas with little or no private-sector presence.Footnote 29 Altogether, the SOEs constituted the foundation of the country’s initial stage of import-substituting industrialization (ISI) and the development of what became known as a “mixed economy.”Footnote 30 The protectionist outlook also limited the entry of foreign direct investment.

Thus, it was during the étatist era that industry came to be seen as the key to modernization, marking the beginning of Turkey’s industrialization process. However, the prominence of state enterprises did not exclude private initiative; several private businesses were also established during this period, partly driven by state contracts.Footnote 31 Despite these advances, Turkey remained largely an agricultural country, much as it had been since Ottoman times. In 1950, 84% of the labor force was employed in agriculture, as in the previous 70 years or so. That same year, agriculture accounted for 54% of GDP, while industry contributed only 13%.Footnote 32

Étatism came under increasing challenge toward the end of the 1940s, not least due to inefficiencies of SOEs and their lack of autonomy from government intervention.Footnote 33 There had also been some further private accumulation during the World War II years because of high inflation, import restrictions, and goods shortages, which made business circles more vocal in demanding clearer delineation of private sector activity.Footnote 34 Moreover, in the immediate aftermath of the war, Turkey began seeking a place within the Western alliance and turned toward the United States for military and economic assistance. This shift led to US pressure for democratic reforms and economic liberalization, culminating in the first multiparty elections in 1946 and a change in government in 1950.Footnote 35

From Mixed Economy to Neoliberal Policies

Although the foregoing period had seen some development of the private sector, growth essentially began to occur with the advent of the pro-business, pro-liberalization Demokrat Parti (DP) to power in the 1950 elections. An immediate step by the DP was the passage of a law to encourage foreign direct investment (FDI), which, however, produced limited results.Footnote 36 While initially opposing the SOEs and promulgating privatization, the DP reversed its orientation in a few years. SOE investments continued to expand, as did the role of the state in the economy.Footnote 37 Nevertheless, private entrepreneurs were also encouraged to engage in industrial activity.Footnote 38 At the same time, the role of the state began to shift, as it retreated toward infrastructure and the production of “intermediate and capital goods for the private sector,” while the latter increasingly focused on consumer goods.Footnote 39 However, this liberal period under DP rule culminated in a major economic crisis toward the end of the decade, ending with a military intervention in 1960.

The ISI era: The coming of age of the private sector. In the aftermath of the military coup, the country adopted five-year development plans, as it turned toward economic planning. Throughout the 1960s and the 1970s, this shift remained grounded in import substitution and protectionist policies, once again under the banner of a “mixed economy.” While SOEs maintained a strong presence in manufacturing and banking, the state also supported the growth of private businesses through low-interest credits, incentives such as tax refunds, and subsidized inputs provided by SOEs.Footnote 40 Within this context of ongoing ISI policies and protection from international competition, private business flourished, the larger among them becoming organized in the form of diversified domestic business groups as in many other late-industrializing countries.Footnote 41 They became structured as “holdings” after the founder of the largest family-owned business group, Koç, successfully secured a legal change to avoid double taxation. This paved the way for the establishment of Turkey’s first formal holding company in 1963.Footnote 42 The holding form was swiftly adopted in the same decade as well as later by other businesspeople, making it the Turkish label for business groups. Although, as in the Koç example above, particularistic initiatives to influence public authorities had a large part in state-business relations, big business owners were also coalescing to become more vocal in policy matters, as signified by the creation of the Türk Sanayici ve İş Adamları Derneği (TÜSİAD; Association of Turkish Industrialists and Businessmen) in 1971, separate from the chambers of industry and commerce.Footnote 43

Thus, private big business, typically under family ownership, was joining the SOEs as a major economic actor in the country. Foreign direct investment again remained meager, largely owing to the restrictive protectionist context of the 1960s and the 1970s, which involved lack of credit incentives that were granted to domestic firms and elaborate bureaucratic procedures for setting up foreign subsidiaries.Footnote 44 Nevertheless, licensing arrangements and some joint ventures were established with multinational firms.Footnote 45 In all, significant growth as well as some degree of structural transformation occurred over this period, as relative to 1950 (see above), by 1980 the share of industry in GDP had risen to 21%, whereas that of agriculture had declined to 26%.Footnote 46

However, the inward orientation of ISI made it increasingly difficult to sustain, as exports did not grow and remained far below increasing imports. The outcome was a severe balance of payments deficit coupled with high inflation and a decline in growth rates during the late 1970s.Footnote 47 This acute economic crisis was accompanied by violent clashes among ideological factions as well as political turbulence with successive changes in government. Several stabilization attempts were made toward the end of the 1970s, eventually culminating in a structural adjustment program in early 1980, followed by a military coup later that year.

The year 1980 was a turning point for the politico-economic environment in Turkey. As in various other late-industrializing countries, a shift was taking place from the previous import-substitution and autarkic era toward economic liberalization and internationalization.Footnote 48

The first phase in economic liberalization and internationalization. The post-1980 transition in Turkey toward a more open market economy has been described as unfolding in two major phases, the first from 1980 to the 2001 economic crisis in the country and the second from 2002 onwards during which the new Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi (AKP; Justice and Development Party) emerged and remained as the ruling party.Footnote 49 The first phase was marked by the successive introduction of pro-market policies together with financial support by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in line with the so-called Washington Consensus. Financial, foreign trade, and foreign exchange regimes were liberalized. Measures were taken to stimulate exports, including the devaluation of the Turkish Lira. The power of labor unions was significantly curbed. Barriers to foreign investment were eliminated, also creating opportunities for joint ventures with foreign firms. After the passage of the Capital Market Law, the Istanbul Stock Exchange was established in 1986. Liberalization of the capital account followed toward the end of the decade.Footnote 50 In 1996, Turkey joined the Customs Union with the European Union (EU), creating an environment of increased international competition for domestic businesses and paving the way for its candidacy for EU membership in 1999. Although privatization had been on the agenda since the mid-1980s and a law to that effect was passed in 1994, not much was achieved during this first phase of Turkey’s liberalization experience. Similarly, levels of foreign direct investment remained low.Footnote 51 The decade of the 1990s also turned out to be characterized by economic as well as political instability, leading to the first crisis of the post-1980 liberalization era in 1994, followed by an even more severe one in the year 2001.Footnote 52

The second phase: Privatization and the turn toward state favoritism. The 2001 economic crisis marked the beginning of the second phase in Turkey’s transition to an open market economy and the start of a new stabilization program with the support of IMF and the World Bank, which aimed to implement major institutional reforms designed to limit government intervention. Several independent regulatory agencies were established soon after, together with enhancing the autonomy of the Central Bank.Footnote 53 As Öniş put it, the new program involved a shift toward “regulatory neo-liberalism” within a “post-Washington Consensus” framework.Footnote 54 The AKP, which came to power a year later, adhered to the requirements of the stabilization program throughout its first term of office from 2002 to 2007, also taking a pro-business stance.Footnote 55 The allegiance of the AKP to institutional reforms led to broadly congenial relationships with big business in the country represented by TÜSİAD, as over time the latter had gained autonomy from the state too and did not need state support.Footnote 56

With greater economic stability, ongoing negotiations for accession to the EU and the enactment of a new foreign investment law in 2003, flow of foreign direct investment increased significantly.Footnote 57 Unlike in the previous phase, the AKP also embarked on a massive privatization drive after 2004, in which both foreign and domestic investors took part, either individually or in partnership.Footnote 58

Yet, privatization not only served as a means for diminishing the role of the state in the economy along neoliberal lines but also laid the groundwork for an impending change in state-business relations, as the AKP’s rise to power brought support for businesses aligned with its pro-Islamic ideology.Footnote 59 Political Islam, defined, for example, by Cesari as “multifaceted religious nationalism,” has had a long history in Turkey, dating back to the post-World War II era.Footnote 60 It began to gain further strength after the military coup in 1980, as “Islam became a favorable ideology against communism and therefore was modestly promoted by the army and Turkey’s major allies.”Footnote 61 Various religious orders were becoming involved with or expanding business and commercial activities in this period.Footnote 62 Together with the post-1980 liberalization drive, pro-Islamic capital started making inroads into business with, for instance, the legalization of Islamic banking and the subsequent establishment of “special finance institutions” (SFIs) that operated on an interest-free basis in accordance with Islamic principles.Footnote 63 They were followed in the late 1980s and the 1990s by the emergence and expansion of what were referred to as “Anatolian holding companies.” These firms also claimed to operate in line with Islamic rules and attracted large numbers of pious investors, particularly among Turkish workers abroad.Footnote 64 The SFIs (renamed as “participation banks” in 2005) persisted, though their expansion and impact in the banking industry remained limited.Footnote 65 Many Anatolian holding companies, however, collapsed after the 2001 economic crisis, having already begun to suffer owing to financial and managerial problems, the absence of a solid legal basis in their relations with investors, and the loss of political backing from the Islamist Refah Partisi (Welfare Party), which was banned by the Constitutional Court in 1998.Footnote 66

Pro-Islamic businesses (including the Anatolian holding companies) had also begun to organize in the early 1990s under umbrella organizations such as Müstakil Sanayici ve İşadamları Derneği (MÜSİAD; Association of Independent Industrialists and Businessmen) and the precursors of what would become the Türkiye İşadamları ve Sanayiciler Konfederasyonu (TUSKON; Turkish Confederation of Businessmen and Industrialists), formally launched in 2005 and linked to the religious community led by the cleric Fethullah Gülen. Situated within the “constituency of political Islam,” these associations emerged as “rivals” to TÜSİAD, which was seen as representing the established big business sector that had benefited from state support during the ISI era and was associated with “secularist values.”Footnote 67 MÜSİAD supported the founding of the AKP in 2001, and this was followed by the development of closer relations between the party and firms connected to what later became the Gülenist TUSKON.Footnote 68 Although most of the firms in MÜSİAD and TUSKON networks were small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), the rise of the AKP to power set the stage for larger businesses to emerge—especially those with close ties to the party, a trend that intensified after its major victory in the 2007 elections.Footnote 69

With the AKP in power, political Islam was beginning to gain center stage. Privatization opened up opportunities in sectors such as mining and energy and served as a mechanism for preferential treatment of Islamic-oriented business circles supportive of the government.Footnote 70 Some of the older big businesses benefited too, as in the acquisition of state-owned TÜPRAŞ, the largest refinery in the country, by Koç Holding in 2005.Footnote 71 However, it was now businesses with Islamic leanings that were essentially securing government privileges and support through particularistic relationships as political Islam gained further ground. Large-scale central and local government infrastructure and construction projects as well as frequent changes in legal frameworks were playing a major role in such favoritism.Footnote 72 Moreover, affiliates of existing FBGs that had failed following the 2001 crisis, such as banks or media firms, were taken over by the Tasarruf Mevduatı Sigorta Fonu (TMSF; Savings Deposit Insurance Fund), some later transferred on favorable terms to businesses supported by the AKP.Footnote 73

The 2008 global crisis also took its toll, leading to a decline in FDI and to stagnation in the economy. The AKP government was now also shying away from EU membership, which led to strains with TÜSİAD, which had a strong commitment to the EU. This tension reached a peak ahead of the 2010 constitutional referendum.Footnote 74 By the end of the decade, it was clear that the post-2001 “regulatory neo-liberalism” phase was breaking down, as the independence of the new regulatory agencies as well as the Central Bank had become significantly impaired owing to increasing government pressure culminating in a case of “reversal” and “decline” in “pro-market reforms.”Footnote 75 There were also strong signs that the country was moving toward greater partisanship and authoritarian rule.Footnote 76

Tracing the Evolution of the Large Enterprise Sector

Drawing on Chandler and studies of big business on countries in Asia, Europe, and Latin America, we single out ownership, organizational form, and industry distribution as the three elements through which we examine the evolution of largest industrial enterprises in Turkey. In Chandler’s characterization of the “modern industrial enterprise” in the United States, ownership was dispersed and separated from management, although he acknowledged the presence of family control in earlier stages of development.Footnote 77 It was in Scale and Scope that Chandler explicitly distinguished among what he called “personal,” “entrepreneurial or family-controlled,” and “managerial” enterprise.Footnote 78

Studies on Western European countries previously carried out at HBS (see above) showed that in all those countries the top 100 industrial enterprises included foreign-owned subsidiaries as well as state-owned firms in France, Germany, and Italy, alongside considerable family ownership and management. Later studies confirmed the continued significance of foreign and state-owned enterprises in France, Italy, and Spain, with family ownership also remaining important in Italy and Spain.Footnote 79 Foreign firms have also been shown to be particularly important in Latin American countries such as Argentina and Chile as well as in countries such as Australia.Footnote 80 Additionally, state and family ownership of large enterprises has been particularly salient in many late-industrializing countries.Footnote 81

Although Chandler’s early work on US enterprises was at the firm-level, already the follow-up studies at HBS (see above) have indicated that at the time some of the large firms in various European countries were parts of “holding” companies. According to Chandler, these holdings were a source of the ills of, for example, in the British economy, as they struggled to manage the transition to integrated enterprises as successfully as those in the United States.Footnote 82 Yet, as mentioned in the Introduction, emerging literature at the time showed that business groups, as a distinct organizational form, not only were preponderant in several East Asian countries but also contributed significantly to their economic growth. These groups then featured in Big Business and the Wealth of Nations, co-edited by Chandler, Franco Amatori, and Takashi Hikino, which included chapters on Japan and South Korea.Footnote 83 A voluminous literature followed, as business groups, typically family-owned and distinct from the Chandlerian managerial enterprise, were found to be the predominant form of big business organization in many late-industrializing countries.Footnote 84

Industry distribution of large enterprises has been part and parcel of studies on big business, starting with Chandler. Since then, this line of research has almost invariably probed into the industrial sectors in which the largest firms have been operating, and quite often, changes thereof, to portray the nature of the technologies and technological developments that they have been involved.Footnote 85

Methodology

Our study is based on a data set consisting of the 100 largest industrial enterprises in Turkey over the period from 1970 to 2010. The main source of this data is the annual rankings by the Istanbul Chamber of Industry (ICI). We accessed these lists in print form—the only available format until 1990—and the electronic versions thereafter through ICI archives. ICI began publishing this series in 1967 by listing the largest 100 industrial firms, continuing in the same way until 1977. It then extended its list to 300 firms until 1980, and from 1981 onwards to the top 500. The ICI list includes only manufacturing and mining firms. Businesses operating in sectors such as agriculture, retailing, construction, utilities, and finance are not included.

For analysis purposes, we extracted the data for nine benchmark years in five-year intervals from 1970 to 2010, using rankings based on total sales. While different criteria such as assets, employees, or market value of capital may be also useful for measuring the size of enterprises, we followed our primary source that used the total sales criteria at the start of our sample period.Footnote 86 We used the same criterion across all benchmark years to ensure consistency. We chose the starting year as 1970 because there were too much missing data and too many undisclosed firm names in the lists for the initial three years after the first time they were published in 1967. We ended in 2010, as the second phase of the Turkish liberalization experience was practically ending owing to the reversals, as we mentioned above, in the independence of regulatory agencies and the Central Bank. Since ICI data were available only for the largest 100 firms during the benchmark years of the 1970s, we confined the construction of our dataset and our analysis to the top 100 firms for the entire study period. This approach ensures comparability and aligns not only with the early HBS studies (see above) but also with more recent research.Footnote 87

After identifying the largest 100 firms for each of the benchmark years, we proceeded with collecting detailed firm information regarding ownership, organizational form, and industry sectors. As there are no readily available historical data for these firm attributes, all 100 firms in each benchmark year had to be investigated individually. We searched various primary and secondary sources, including publications by the Union of Chambers and Commodity Exchanges of Turkey, Trade Registry Gazette, company websites, and in some cases newspaper archives. Two research assistants conducted the search independently, and the results were cross-checked with each other for each firm and each benchmark year. When there was any discrepancy, the first author took the initiative to carefully re-examine multiple sources to obtain definitive information on the firm in question.

With respect to ownership, we classified firms into four categories according to their controlling owners, namely state-owned, family-owned, foreign-owned, and other forms of ownership, which included firms that were controlled by agricultural cooperatives or pension funds. We defined controlling ownership as ownership of 51% or more of shares in a firm, often directly and in some cases via cross-shareholdings in the case of affiliates of business groups. When there was no owner controlling more than 50% of the shares, we coded the firm’s ownership according to the owner-type holding the largest proportion of shares, provided it constituted a sufficiently large minority block. In the case of equal 50% (or in some cases less but equal) ownership by two different categories of large owners, we used 0.5 to divide ownership equally into the different types of owners.

For organizational form, we distinguished between stand-alone firms and those that were affiliated with a business group. Business groups were operationally defined as sets of three or more firms (not necessarily all included in the largest 100 list) in multiple industries that belonged to the same owner (often organized as a holding company) in each of the benchmark years. In our timeline, we coded a firm as an affiliate of a business group only when this criterion was met.

We determined the industrial sector in which a firm operated on the basis of the International Standard Industrial Classification (ISIC) at the two-digit level. While the ISIC codes were readily available for the post-1995 lists in the ICI database, for 1990 and earlier time periods, we had to search for individual firms in each benchmark year from the abovementioned data sources.

Largest Industrial Enterprises in Turkey, 1970–2010

We present our findings on the evolution of the 100 largest industrial firms in Turkey, based on total sales, in three parts according to the dimensions that we specified, namely ownership, organizational form, and industry distribution. In each part, we trace how the firms in the top 100 have evolved with respect to these dimensions along the three time periods identified in our post-World War II historical overview, namely the ISI era and the first and second phases of liberalization. The ISI era spans the decade of the 1970s, characterized predominantly by import-substituting industrialization (ISI) and an autarkic economy. The first liberalization phase includes the two decades following the introduction of the stabilization program and pro-market reforms in the year 1980. The second liberalization phase covers the decade of the 2000s, comprising the next stage in the Turkish liberalization experience, coupled with the advent of AKP governments.

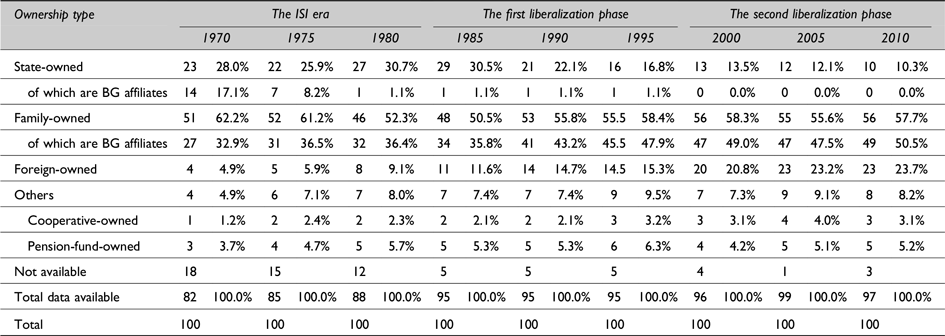

Ownership structure: Marked change but also notable continuity. Table 1 presents the ownership distribution of the 100 largest firms for each of the benchmark years according to state-owned, family-owned, foreign-owned, and other ownership categories. To start with, it shows that, at the beginning of our study period in 1970, midway through the post-1960 ISI era under a planned economy, a significant presence of SOEs persisted. However, the encouragement of private sector development since the post-World War II years began to bear fruit, with nearly two-thirds of the largest enterprises in private hands, typically family businesses. Foreign-owned enterprises were few, as were those owned by cooperatives and pension funds.

Table 1: Ownership Composition of the Largest Industrial Enterprises in Turkey, 1970–2010

Source: Data for this study were compiled from ICI Archives (1970-2010) and supplemented with sources listed in our Methodology section.

Note: The proportions are due to the way we operationalized ownership, as we assigned 0.5 to each type of owner when there was equal ownership by two different categories of owners (see the text above)

Table 1 also demonstrates that there have been significant changes as well as considerable continuity over the three periods that involved major shifts in the economic policy environment. First, we see an overall decline in state ownership. Whereas SOEs constituted 28% of the largest firms in 1970, their presence fell to only 10.3% in 2010 (Table 1). The decline set in halfway through the first phase of liberalization in the economy, following a rise in the share of SOEs to its peak of around 31% in 1980 and 1985. Since 1990, however, state ownership lost ground at a rather steady pace, reaching its lowest level, as indicated above, by 2010, the end of the second phase of liberalization. This decline, as we shall see below, was preceded by and continued in the same manner in terms of how SOEs among the largest firms were organized.

Second, we see that the presence of family-owned firms among the largest enterprises stayed almost stable throughout the 40 years. It was at its peak in the ISI era under economic planning, with a 62.2% share at the beginning of our study period in 1970 (Table 1). A non-negligible drop did occur at the end of this era (i.e., to 52.3% in 1980), possibly owing to the economic crisis before the introduction of the stabilization program that marked the transition toward liberalization. There was a further decline during the initial shock years of the transition, resulting in a share of 50.5% in the year 1985. Since then, however, family-owned big business began to recover, reaching a 58.3% share at the end of the first phase of liberalization in the year 2000, and then settled around that level by 2010. Notwithstanding these minor fluctuations, paramount, of course, is the continuity that we observe in the dominance of family ownership in large private businesses in the country, though with changes in the way it was organized, again as we shall see below.

Third, we see an important increase in the share of foreign firms, as fully owned subsidiaries as well as joint ventures with Turkish partners. While they constituted only 4.9% of the largest firms in 1970, by the end of the two phases of liberalization in 2010, their share had gone up to almost a quarter (23.7%; Table 1). This growth occurred at a rather steady pace, beginning in the aftermath of the 1980 stabilization program, reaching a 20.8% share by the year 2000, and eventually culminating in the level of approximately a quarter mentioned above.

Although the country of origin is not explicitly listed in our primary dataset, a closer examination of our sources allowed us to identify the countries from which foreign-owned enterprises originated. In terms of the country of origin, US firms led the way into the 1990s among foreign-owned enterprises but were surpassed by German firms during the 2000s. Otherwise, firms from European countries, such as France and Italy, featured in all the benchmark years, while not exceeding two entries in any particular year. Swiss and Dutch firms also appeared in similar numbers, though mainly after the year 2000. The same was the case for firms from Asia, for example, from Japan and South Korea, however, with neither, again, going beyond two entries in any year. Overall, there was a marked increase over time in the diversity of countries from which firms were investing in Turkey. Whereas there were foreign subsidiaries from only four countries in 1970, in 2010 the range had gone up to 11 different countries.

Finally, firms owned by cooperatives and pension funds overall played a marginal role during the entire period that we examined, altogether not exceeding 10% within the top 100 in any benchmark year (Table 1). Nevertheless, as we shall see below, the two pension funds came to own diversified business groups, with indeed one having two or more firms among the top 100 throughout the entire 40 years covered by the study.

Organizational forms: Business group affiliates versus stand-alone firms. Table 1 also presents our findings concerning the organizational form of large enterprises appearing in the top 100, namely as affiliates of business groups or stand-alone firms. As the table shows, there have been changes in the relative share of these two forms of big business organization in both SOEs and family-owned businesses, though in divergent ways.

In the case of state-owned firms, in 1970 the majority of SOEs among the largest enterprises were part of what had turned into business groups, as pointed out in the review above. Yet, by 1975, they no longer constituted the majority, as their share relative to stand-alone state-owned firms dropped from about two-thirds in 1970 (14 firms among 23 under state ownership) to a third in 1975 (7 firms in a total of 22 state-owned firms; Table 1). From 1980 onwards, they became marginalized, and after 2000 what was left of SOEs were all stand-alone firms.

In contrast, organizational forms of large family-owned enterprises developed in the opposite direction. In 1970, FBG affiliates and stand-alone family firms were relatively close in number, at 27 and 24, respectively (Table 1). Yet, already by the end of the ISI period in 1980, there were more than twice as many FBG affiliates entering the top 100 list compared with stand-alone firms (32 versus 14; Table 1). As we pointed out above, overall, family-owned big business was negatively affected by the economic crisis of the late 1970s as well as the early shock years of the post-1980 shift to a liberalized economy. Table 1 suggests that stand-alone family firms were hit harder, as halfway through the first phase of the transition (i.e., 1990) there were more than three times as many family-owned business group affiliates in the top 100 list (41 firms as opposed to 12). The gap widened after that so that, by 2010, there were only 7 stand-alone family businesses as opposed to 49 FBG affiliates (Table 1)

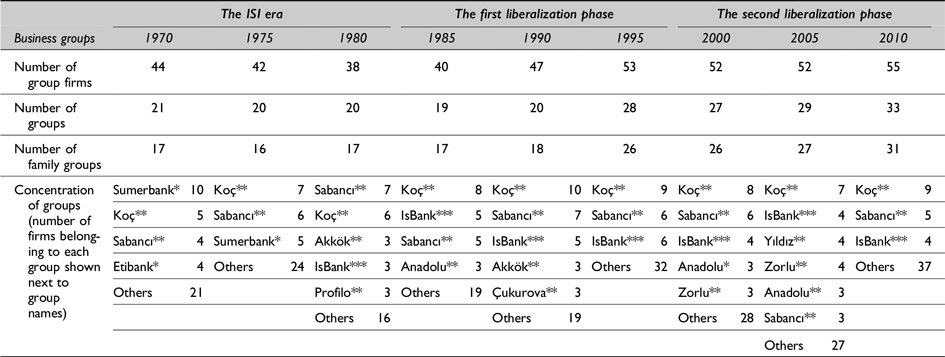

Table 2 provides further findings on how business groups and their affiliates have developed over the 40-year period. It shows that the number of business groups (of all kinds of ownership) that had affiliates among the largest enterprises remained stable throughout the ISI era as well as halfway through the first phase of post-1980 liberalization (i.e., until 1990). Starting with the year 1995, however, a notable increase emerged in the number of business groups with affiliates in the top 100 lists. The same pattern continued in the second phase of liberalization so that by 2010 there were 33 business groups that had affiliates among the largest enterprises as opposed to only 21 in 1970 (Table 2). Apparently as a result, the concentration ratio for business groups with more than three affiliates in the top 100 went down to around 33%, as opposed to about 52% at the beginning of our study (i.e., 1970).Footnote 88 This ratio remained above 50% until 1990 (except for the year 1975), falling to about 40% in 1995 and then oscillating around 47% in 2000 and 2005 until the rather abrupt drop, as mentioned above, to a 33% level at the end of the second liberalization phase (i.e., year 2010).

Table 2: Business Group Ownership of the Largest Industrial Enterprises in Turkey, 1970–2010

Source: Data for this study were compiled from ICI Archives (1970-2010) and supplemented with sources listed in our Methodology section.

Note: Only business groups with three or more affiliates among the top 100 at each benchmark year are shown. This table shows the absolute numbers of groups or group firms, without accounting for partial ownership.

* State-owned group

** Family-owned group

*** Pension-fund-owned group

The same table also indicates that the greater presence of business group affiliates among largest enterprises primarily resulted from increases in the number of FBGs. As shown in Table 2, this growth stemmed from a significant rise in the number of large FBGs in the country. While the number of FBGs remained stable between 1970 and 1980, it nearly doubled from 1980 to 2010, increasing from 17 to 31. Delving further into the data, we found that this rise was driven by the emergence of new FBGs during the first liberalization phase (i.e., the 1980s and the 1990s). In fact, by 2010, the majority of the FBGs with affiliates in the top 100 were those that had become organized as a business group (typically a “holding” in the Turkish context) during this liberalization period, rather than those formed in the ISI era.

Table 2 also presents our findings on how specific business groups and their affiliates fared from 1970 to 2010. To start with, while the two largest state-owned business groups (Sümerbank and Etibank, both established in the 1930s during the étatist period) had a relatively high number of affiliates in the top 100 list in 1970, already by 1975 they were in decline (Etibank with two affiliates in addition to Sümerbank’s five). As mentioned above, by 1980, their affiliates had all but disappeared, and by the end of the first phase of liberalization (i.e., 2000), none were left. The few that remained were only the stand-alone SOEs.

Turning to FBGs, Table 2 reveals both continuity and considerable turnover. Koç and Sabanci, already organized as “holdings” in the 1960s and with relatively long earlier histories, were the only FBGs to have three or more affiliates throughout the entire period covered by this study.Footnote 89 Three or more affiliates of the other long-established groups appear only once (Profilo and Çukurova) or intermittently (Akkök and Anadolu) in Table 2. Nevertheless, Profilo also had two affiliates in 1975 and from 1985 to 1995; Akkök in 1985, 1995, and 2005; and Çukurova in 1995 and 2005.Footnote 90 Zorlu and Yildiz, which appear in Table 2 toward the end of the study period, are the major newcomers organized as holdings halfway through the first liberalization phase, although the founder of the latter had entered business under the family name Ülker as early as the 1940s and the company had grown primarily in food and related sectors.Footnote 91 Both Zorlu and Yildiz also had two affiliates in the 2010 top 100 list. In addition, there are 14 other FBGs that had two affiliates either once or multiple times, consecutively or intermittently. Some of these are the older groups that dated back to the ISI era (e.g., Eczacıbaşı, Yaşar, Borusan) while others (e.g., Sanko, Doğan, Kibar, Boydak, Hayat) were organized as holdings during the first liberalization phase.

Apart from Koç and Sabanci, another case of continuity is the rather unique IsBank, whose affiliates appeared in all benchmark years from 1980 onward (Table 2), with two of its firms also entering the top 100 lists in 1970 and 1975. This is a bank-centered group, with controlling shares held by the bank’s pension fund for its current and retired employees.Footnote 92 A somewhat similar notable case, though not featuring in Table 2, is Ordu Yardımlaşma Kurumu (OYAK). OYAK, which was founded in 1961 following the 1960 military coup, is a pension fund for military personnel and civilian staff working in Turkish Armed Forces.Footnote 93

Of the FBGs in Table 2, a member of the family owning the Yildiz group, affiliates of which appear in the 2005 list with four firms, held membership both in TÜSİAD and the pro-Islamic association MÜSİAD (see above).Footnote 94 In addition, affiliates of Sanko, Boydak, and Hayat, which had developed into a business group in the latter part of the first liberalization phase (i.e., late 1980s and the 1990s) and had ties to MÜSİAD or Gülen community’s TUSKON (see above), also entered into the top 100 lists.Footnote 95 Sanko had two affiliates appearing consecutively between 1990 and 2005, while Boydak and Hayat each had two in 2010. All these three groups began to grow in their initial lines of business in the 1970s and the 1980s.Footnote 96 There were also other FBGs (e.g., Abalioğlu, Kazancı, and Tosyalı) that were formed as holdings in the 1990s and were linked to MÜSİAD or TUSKON, though each had only a single affiliate in the 2010 top 100 list.Footnote 97 In all, the number of firms belonging to pro-Islamic business groups increased from 5 in 2000 to 10 in 2010. Notably, although some of these FBGs also expanded internationally, foreign involvement in their home-based firms stayed limited, apart from the affiliates of the Yildiz group, which had several minority foreign partners.Footnote 98

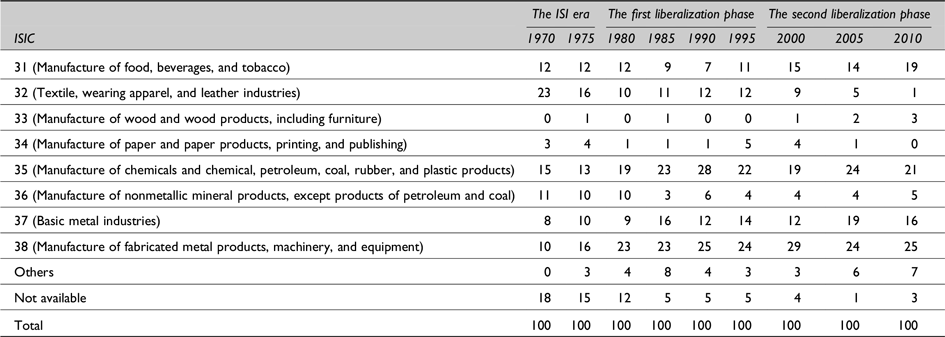

Industry sectors: From low to medium technology. Table 3 presents the industry distribution of the largest enterprises again for the entire 1970–2010 period. This table shows highly notable changes, as the number of firms in some industries declined sharply and became replaced by firms in several other industries, indicating some move from low technology to medium-low and medium-high technologies in line with the broader restructuring in manufacturing after the transition to a liberalized and internationalized economy.Footnote 99

Table 3: Industry Distribution of the Largest Industrial Enterprises in Turkey, 1970–2010

Source: Data for this study were compiled from ICI Archives (1970-2010) and supplemented with sources listed in our Methodology section.

To start with, there was a marked decline in textiles. Whereas more than a quarter of the largest enterprises (28.0% to be precise) operated in this industry in 1970, by 2010 this proportion dropped to only about 1% (Table 3). The decline had already begun during the ISI period, stabilizing around a level of 11–12% until the latter part of the first liberalization phase (i.e., the 1990s). Decline again set in toward the end of this stage, continuing further during the second phase of liberalization to result at the end in the negligible figure mentioned above.

Likewise, though it was not as drastic as in textiles, we also observe a decline in nonmetallic minerals. The share of this industry was rather stable at a level of 11–13% during the ISI period and the early shock years of the post-1980 transition. A rather abrupt drop to around 3% or so followed, which then remained with some recovery at a level of around a 5–6% share throughout the two phases of liberalization (Table 3).

Conversely, we see a notable increase in the share of firms in the machinery and equipment industry. The growth in the number of firms in this industry in fact occurred during the ISI period and has since settled, some fluctuations notwithstanding, slightly above the level that was reached in 1980 when the transition to a liberalized economy began. Despite some fall during the second phase of liberalization, by 2010 firms in these industries had the highest share, constituting a quarter of the largest enterprises (Table 3).

Firms in metals, food and beverages, and chemicals industries also expanded their presence over time among the top 100 lists. The increase in the number of firms in the metal industry is particularly notable. With some fluctuations during the two liberalization phases, by 2010 there were twice as many of these firms in the top 100 list compared with the year 1970 (Table 3). Firms in the food and beverage industry also recorded a 50% increase relative to the ISI era of the 1970s. Interestingly, there was some decrease in their share during the first decade of the liberal transition. There was a nascent increase after then, which led to the highest level of food and beverage firms in the year 2010. Although there were more chemical industry firms in 2010 than 1970 too, there were significant fluctuations during the two liberalization phases. Firms in this industry were on the rise from the year 1980, reaching their peak halfway through the first phase of the post-1980 transition, but then, with ups and downs, ended up in 2010 with 40% more firms than 1970 (Table 3).

We complement our findings about industry distributions across time by including the changes that have occurred in ownership and organizational forms. While the table is not shown here for brevity, our analysis of the data allows a comparison between the start (1970) and the end (2010) of our study period. For the year 1970, during the ISI period, we find that the dominance of textile firms among the largest enterprises was due to both state- and family-owned firms in comparable measure, many of which were affiliates of business groups. Both state and family firms featured in all industries (other than wood products in which neither existed) but fabricated metal products, machinery, and equipment, although there were in all cases more family-owned enterprises, most of them stand-alone. At that stage, family firms, mostly FBG affiliates, almost entirely dominated the fabricated metals, machinery, and equipment industry, apart from a single foreign firm. Otherwise, the few foreign-owned firms featured only in the chemicals industry. And the few cooperative- and pension-fund-owned firms were engaged with the nonmetallic minerals industry.

As would be expected from what has been reported above, a different panorama emerges for the year 2010. The major companion at that time to family-owned firms (mostly FBG affiliates) was foreign-owned firms instead of SOEs. Foreign firms were at that time concentrated primarily in chemical and petroleum products and the fabricated metals and machinery industry, accompanied at similar scales by private domestic businesses. The latter differ from foreign firms in their much higher presence in mineral products and the food and beverage industry.

Discussion and Conclusions

Our study was inspired by research on big business, which began with Chandler and was later extended, first to advanced economies in Europe and then to various other countries. In essence, our findings indicate that, with the shift from import-substituting industrialization to liberalization and internationalization, the composition of Turkey’s largest industrial enterprises evolved from a balanced mix of stand-alone family businesses, affiliates of FBGs, and SOEs to a new configuration dominated by FBG affiliates and, to a lesser extent, subsidiaries of foreign firms.

With these findings our study makes two major contributions to comparative research on big business in late-industrializing countries undergoing pro-market reforms. The first main addition to the literature relates to the impact of pro-market reforms on the largest industrial enterprises. To start with, our findings demonstrate that, in the case of Turkey as well, there are very limited signs that large domestic firms have been evolving toward the Chandlerian managerial enterprise, despite the shift to a liberalized economic environment. Family-owned businesses, typically characterized by family management, began to develop in the post-World War II years with the move away from state-led industrialization and have increasingly prevailed since then. Although a stock exchange was formally established in the early years of the first liberalization phase and some family businesses floated part of their shares, dispersed ownership failed to emerge. Nor did control by salaried managers become common. Although there has been some retreat on and off from executive management more recently among the larger family business groups, family control has persisted with the Chandlerian managerial enterprise not at all in sight.Footnote 100 Neither could the so-called Anatolian holding companies, which were initiated with the purported aim of dispersed “ownership” evolve into managerial enterprises and survive as such. In the Turkish context, therefore, it was only the businesses owned by the two pension funds (that of IsBank and OYAK) that turned out to be the exceptions in approximating the managerial enterprise, other than foreign-owned firms operating in the country.

Relatedly, our findings suggest, in line with earlier work not only on late-industrializing countries but also on “followers in Western Europe,” such as Italy and Spain, that large enterprises are shaped not merely by market forces and economic efficiency pressures.Footnote 101 Rather, the political and the societal context surrounding business activity serves as a major source of influence. While such “background institutions” were absent from Chandler’s “explanatory framework, even if not always from his narrative,” they appear to have played a central role in the evolution of Turkish big business during the three periods examined in this study.Footnote 102 In particular, the state has had paramount significance in Turkey. As our findings show, the private sector began to flourish after World War II within the protectionist ISI environment, benefiting from various forms of state support. Moreover, some of these family businesses developed into FBGs characterized by unrelated diversification, driven in part by the “market-forming role of the state.”Footnote 103 This influence has extended beyond the ISI era, as post-1980 pro-market reforms also opened new opportunities, initially through the liberalization of various service sectors, such as banking.Footnote 104

In addition to the role of the state, in broader societal terms, religion and Islamic politics also had a part to play, as they had been on the rise, gaining greater strength in the 1980s and the 1990s, which provided a basis for an alternative business community with Islamic leanings to develop. These businesses were initially very much in the form of export-oriented SMEs operating in low-technology sectors. With the advent of the AKP government in the early 2000s, the state again entered the picture, this time by creating opportunities for the favored pious businesspeople. Although the mechanisms of state involvement differed from earlier periods, the outcome was similar: the formation of state-sponsored family businesses. As our findings show, many of these emerged not as large stand-alone firms, but once again as part of business groups.

A significant outcome of the post-1980 liberalization and internationalization experience in Turkey has also been the rise of foreign-owned firms among the largest industrial enterprises in the country, as our findings indicate. This result is particularly notable in that foreign direct investment played virtually no role in Turkey’s earlier industrial history and remained marginal even during the ISI era. With the onset of the post-1980 pro-market reforms, there has been a steady growth in the number of foreign firms increasingly from a broader range of countries as fully owned subsidiaries or joint ventures. Notably, our findings also show that the Turkish subsidiaries of all these foreign multinationals have been single-line businesses. None of them have developed into business groups as in some countries such as Chile, where foreign multinationals, with a much longer investment history, have adopted this form.Footnote 105 Overall, the expansion of foreign-owned firms provides strong evidence of Turkey’s greater integration into the global economy as a major outcome of the post-1980 pro-market reforms.

The second major contribution of our study relates to the recent literature on the fate of business groups in late-industrializing countries, particularly in the aftermath of liberalization and internationalization. Several of our findings stand out in this respect. To start with, overall, we show that, after a setback immediately following the introduction of pro-market reforms, business group affiliates, particularly those of FBGs, have expanded their presence among the largest industrial enterprises. And this growth occurred despite political turbulence and severe economic crises, especially during the first phase of liberalization. Moreover, it unfolded within the context of an increasingly open economy that brought heightened international competition, marked by liberalized imports and the growing presence of foreign firms.

Even more importantly perhaps, findings of our study also indicate that the business group as an organizational form has expanded within this environment. Indeed, we found a significant rise mainly in the number of FBGs with affiliates in the top 100 in the latter half of the first liberalization phase (i.e., mid-1990s), followed by another notable increase at the end of the second phase. Thus, the growth of business group affiliates among the largest industrial enterprises stemmed not only from the older groups predating the 1980 shift to liberalization but also, and even more so, from new cohorts of post-transition FBGs. Thus, our findings are not only in line with studies that point to the persistence of business groups but also extend them by showing that, in the Turkish context, particularly FBGs have in fact proliferated under conditions of liberalization and internationalization.

Indeed, the liberalized environment has been conducive both to the expansion of older business groups and the rise of new FBGs by creating novel opportunities.Footnote 106 These possibilities have originated in early stages through the liberalization of some sectors, as mentioned above, and later from the privatization drive that ensued. These emerging opportunities were actively seized by both established and emerging business groups, which adapted swiftly to the evolving regulatory and market landscape.Footnote 107 The liberalization process not only facilitated growth in traditional sectors such as food and beverages but also spurred diversification into those such as chemicals and basic metal industries. Subsequent privatization efforts opened further avenues for expansion, especially by enabling business groups to acquire formerly state-owned assets and enter industries that had previously been off-limits to private enterprises, such as telecommunications, energy, alcohol, and tobacco.

Furthermore, older FBGs in particular are likely to have benefited from their organizational and financial capabilities in maintaining their diversified portfolio during liberalization, as well as entering new industries together with some degree of streamlining.Footnote 108 Organizationally, they possess not only “functional” capabilities such as marketing, distribution, and research and development in technology but also “trans-product capabilities at the group level” through repeated entries into new businesses.Footnote 109 Competitive advantages that accrue owing to “management practices” that have been created internally together with recent moves, despite ultimate family control, toward a greater role for salaried managers have likely contributed as well.Footnote 110 In addition, the reputations these groups have built over time have likely played a significant role.Footnote 111 Reputation enhances credibility with potential partners and foreign investors, which can be particularly critical in international expansion and joint ventures. Financially, older groups have also benefited from accumulated internal capital and relatively easier access to credit, both through banks under their control and through broader financial networks.Footnote 112

Although not endowed with these capabilities to the same degree at the beginning, new business groups were also able to emerge by capitalizing on the opportunities provided by the liberalized environment as well as acquiring other firms. These initiatives were possibly motivated by older FBGs serving as a model for becoming big business and the view that adopting this organizational form could be the way to compete with the established ones that dominated the economy.Footnote 113 Some of the new ones could benefit too from reputational effects of their initial lines of business or the financial resources that they accumulated over time. Nevertheless, as our findings show, despite the increase in new FBGs since the latter part of the first phase of liberalization, affiliates of only a few could measure up particularly to those of the leading old FBGs among the largest industrial enterprises.

While perhaps unique to Turkey in recent years, post-2000 political change turned out to be a significant factor in the expansion of the population of FBGs in the country as well as the growth of some in size.Footnote 114 Major beneficiaries of this political change were businesspeople who had Islamic leanings and who were close to the AKP government that had come to power. Privatization and large-scale public projects were used as mechanisms for creating opportunities for this alternative business community. The preferential treatment of favored entrepreneurs did not always lead to the development of big business, but in some cases it did, as our findings show for less than a decade after the advent of the AKP government.

However, our data also indicate that, throughout the second phase of liberalization (i.e., the 2000s, mostly under AKP rule), the number of FBGs with ties to the two pro-Islamic business associations (MÜSİAD and TUSKON) that managed to place affiliates among the largest industrial enterprises has remained somewhat limited.Footnote 115 Only a few achieved this, with the Yildiz group standing out as the sole case that could rival established FBGs such as Koç, Sabanci and the pension fund-owned IsBank group by the mid-2000s. Otherwise, most firms with ties to MÜSİAD and TUSKON have remained SMEs, operating in low-technology sectors such as small-scale construction and retail, characterized by relatively low capital requirements.Footnote 116 Yet, although some pro-Islamic businesses also benefited from privatization in sectors such as mining, the fact that not many affiliates of these politically connected groups could appear among the largest industrial enterprises appears to do with the business opportunities created by the AKP government and local authorities being concentrated in energy utilities, housing, and infrastructure.Footnote 117

Although we do not have data on the period after 2010, some of the earlier studies have argued that, as the AKP stays in power, pro-Islamic FBG firms may find further opportunities to challenge the established old group firms.Footnote 118 However, the 2010s have also shown that political connections and mutual support between businesses and government do not necessarily develop in a linear fashion. This is best exemplified by the fall out between the Gülen community and the AKP, which began in late 2013 and came to a head after the failed coup attempt in 2016. Hundreds of organizations of various kinds were closed, their leaders were purged, and some were brought to court. A particularly notable case from business is the Boydak group mentioned above, which was accused of having ties with the Gülen movement, leading to the arrest of key executives, including members of the Boydak family. All the companies of the group were transferred to the TMSF (see above) and were brought under trusteeship.Footnote 119 Notably, relations between the AKP government and the Yildiz group also became lukewarm in this period, leading the latter to move some of its investments abroad.Footnote 120

Before concluding, two limitations of the study need to be mentioned. First, as we noted above, the ICI lists that we used as our main data source do not include firms in sectors such as agriculture, retailing, construction, utilities, and finance. That firms in these sectors have had to be excluded in our study likely led to an underestimation of the growth of pro-Islamic businesses, as they (including noticeable “holdings” such as Cengiz, Limak, Kalyon, and Koloğlu) have been particularly active in some of these sectors. As mentioned above, this is because those pro-Islamic groups have been prominently favored in public tenders related to energy utilities, housing, and infrastructure projects.Footnote 121 Secondly, the ICI data are collected through questionnaires, and businesses are free not to disclose their names when the lists are constructed. Although the latter seems to be of little concern, particularly for later benchmark years, since we have close to a full sample as shown in the tables above, it is not possible to know how many and which firms have not responded to the questionnaires, as this information is not publicly available.

Our point about the exclusion of nonindustrial sectors also indicates a possibility for future research, though access, especially to historical data, is likely to be daunting. Likewise, although there has been considerable discussion in the literature, probing further into why large businesses in Turkey have not been able to match those of some other late-industrializing countries both in scale and global impact awaits further research, which, if it could be done, would be no mean task.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the editors and two anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments. We also wish to express our thanks to those who contributed to gathering the data in the early stages of this paper, including Prof. Baris Tan, as well as research assistants Mingze Ma and Aytuna Barkcin. The first author would also like to express her gratitude to the late Prof. Takashi Hikino for his encouragement in pursuing this topic.

Author Biography

Asli M. Colpan is Professor of Corporate Strategy at the Graduate School of Management and Graduate School of Economics, Kyoto University, Japan. She is also the Assistant Executive Vice President of Kyoto University. Her work has been published in such journals as Industrial and Corporate Change, Journal of Management Studies, Strategic Management Journal, Strategic Organization, Journal of Business Ethics, Business History, International Business Review, and Corporate Governance: An International Review. She is also the co-editor of the Oxford Handbook of Business Groups, with Takashi Hikino and James Lincoln (2010); Business Groups in the West: Origins, Evolution, and Resilience, with Takashi Hikino (2018); and Business, Ethics and Institutions: The Evolution of Turkish Capitalism in Global Perspectives, with Geoffrey Jones (2020).

Behlül Üsdiken is a professor at Özyeğin University and an emeritus professor at Sabanci University, both in Istanbul, Turkey. His work has appeared in Academy of Management Annals, Academy of Management Learning & Education, British Journal of Management, Business History, Journal of Management Inquiry, Journal of Management Studies, Management & Organizational History, Management Learning, Organization Studies, Scandinavian Journal of Management, Strategic Management Journal, and Strategic Organization as well as in several edited collections and Turkish journals. He is co-author, with Lars Engwall and Matthias Kipping, of Defining Management: Business Schools, Consultants, Media (2016) and, with Matthias Kipping, History in Management and Organization Studies: From Margin to Mainstream (2021).