Introduction

Limited availability of written records has been a blessing as well as a curse for the study of African history. The curse is clear. Answers to central historical questions, ranging from the region's long-run demographic development to transformations of its agricultural systems, processes of state formation, the rise of cities, practices of warfare, and ethnic identity formation, have been formulated with uncomfortable degrees of imprecision and long lists of caveats. Indeed, the scarcity of textual source materials has often precluded a settlement of scholarly debates on the basis of decisive historical evidence. However, the blessing — in disguise one may add — is that such constraints have made historians of Africa deeply aware of the need to combine different types of source materials, to adopt a variety of approaches, and to integrate the insights and expertise of adjacent academic disciplines such as archaeology, paleobotany, historical linguistics, anthropology, and ethnography into their reconstructions of the past.Footnote 1 In doing so, Africanist historians have repeatedly been at the fore of innovation in the history profession.

In light of the professional imperative for interdisciplinary approaches, we hope that the new quantitative approaches that have emerged in the field of economic history over the past fifteen years will become more ‘mainstream’ in African history. While certain strands of literature that explore dimensions of economic change and combine (some degree of) quantitative methods with qualitative analysis are well integrated in Africanist scholarship — for example, studies on the transatlantic slave trade — this is less true for the more quantitative- and economic theory-heavy work that has done by the ‘new’ African economic historians.Footnote 2 The reasons for this prolonged disconnect are clear: the institutional location of economic historians in the profession and the associated publication incentives, a general unfamiliarity and unease with quantitative methods among historians nowadays, as well as a profound skepticism about data from Western sources and the use of Eurocentric methods.Footnote 3 While such concerns are certainly not unfounded, we should be careful not to throw out the baby with the bathwater. If carried out diligently, there are great benefits to normalizing quantitative approaches in African history (again) and to bringing qualitative and quantitative research approaches into closer conversation with one another.

In this paper, we take a step towards strengthening this bridge, by surveying major developments in the ‘new’ quantitative economic history of Africa since Anthony Hopkins's last statement in this journal in 2009; most of which has been published in the leading economic history journals.Footnote 4 Our review highlights two main arguments. First, there is great variation in the types of quantitative methods and data that underpin the ‘new’ economic history of Africa, each with its own promises and pitfalls. For historians who are less familiar with the spectrum of quantitative methods, it may be helpful to recognize two distinct branches in the field and see how the methods of ‘economic historians’ are different from those adopted by ‘historical economists’, a distinction we will explain in the next section.

Second, we argue that the increased use of data and quantitative approaches have generated valuable insights into the historical contexts and material conditions that shaped the lives of millions of Africans, including aspects of demography, poverty, slavery, inequality, migration, state formation, and colonialism. To be sure, quantitative indicators are neither ‘neutral’ vantage points nor can they replace the breadth of qualitative methods that are needed to capture the full scope of human experiences and to place African voices center stage.Footnote 5 However, using numbers to obtain a better sense of comparative orders of magnitude, to explore the nature (direction, acceleration, volatility) of short and long-term developments, and to assess the distinctive features of African economies and societies in global comparative perspectives can be valuable complements to the insights from qualitative work.

Moreover, the ‘new’ economic historians share many of the concerns that Africanist historians have about the quality, assumptions, and purposes that underpin historical statistics; especially those created by colonial governments and other Western actors. The quality of historical data, however, does not neatly fit into binary categories of ‘good’ and ‘bad’. Data quality varies from one individual statistic to another, and their usefulness depends on the types of questions we seek to answer, the sensitivity checks we can perform, and the extent to which the conclusions would be affected by any biases that are introduced.Footnote 6 Economic historians are trained to asses, create, and analyze historical data, and thus have a particular skill-set that can maximize what we can learn from a limited and challenging source base; much like many other subfields in African history.

Our review is not meant to be comprehensive, and it cannot be for space-constraints alone. For one, our review focuses mostly on the twentieth century, and on the colonial period in particular; the era for which new quantitative sources have become widely available.Footnote 7 This, for example, means that recent work on the transatlantic slave trade falls outside the scope of our paper. Additionally, we will say little about developments in African financial history, business history, fiscal history, and several other sub-strands of historical research that touch on questions of economy, or that use statistics as part of their evidence base.Footnote 8 Instead, we will highlight a selection of widely used quantitative methods and discuss them in relation to some of the key questions that African (economic) historians have been working on.

Our article contains six sections, each of which explores different aspects of the ‘new’ economic history. We start by detailing how the ‘new’ quantitative African economic history has developed into two major branches, each with its own research aims and methods. We will then take readers through four major research topics that have received special attention from the ‘new’ economic historians over the last decade, and that we believe to be of interest to Africanist historians at large: long-term patterns of economic growth, trade, labor, and inequality. For each of these topics, we introduce readers to the data and quantitative methods that were used, discussing their strengths and limitations. We close our survey by drawing attention to a recent trend, which focuses on cross-continental comparisons. Our paper argues that the use of quantitative methods and comparative perspectives has sharpened views on the long-term economic trajectories within Africa, and that it has integrated the region more firmly into debates about the making of the global economic divide. We are hopeful that greater engagement between mainstream African history and the new economic history will generate valuable intellectual pay-offs in the decades ahead.

Two branches of the ‘new’ African economic history

The field of African economic history has gone through some remarkable cycles of expansion and contraction. Between the 1960s to 1980s, scholarly interest in questions regarding the demographic impact of the slave trades, the economic rationale and legacies of colonialism, and the spread of capitalism surged and sparked heated academic debate.Footnote 9 Dependency and Marxist perspectives dominated the literature in these days, while the influential ‘formalist-substantivist’ debate within economic anthropology scrutinized the validity of Western economic theories highlighting the role of ‘rationality’, ‘markets’, and prices in understanding problems of resource allocation in the context of African social relations and cultural practices.Footnote 10 By the late 1980s, however, the energy had seeped away from the field. With a handful of notable exceptions, leading scholars of the first wave either retired or branched off to other emerging fields, such as global history. Especially in the American academy, the ‘cultural turn’ dampened enthusiasm for quantitative methods and economic historical projects. Marxist perspectives lost ground with the collapse of the iron curtain. As a result, the study of questions about long-term African economic development had all but disappeared from the radar by the close of the twentieth century.Footnote 11

Paradoxically, this fading interest transpired at a critical time for the region, as it coincided with intense political and economic distress in many African societies. Global poverty shares, which had long been dominated by Asia, increasingly concentrated in sub-Saharan Africa. Economic historians, however, had their gaze on Asia and became preoccupied by the so-called Great Divergence debate.Footnote 12 The renewed attempt to explain why Britain industrialized before China took place in the context of China's impressive economic ‘re-awakening’, and inspired large empirical and comparative research agendas. While the Great Divergence debate generated new insights and methodological tools that would later be applied to African economic history (some of which we discuss below), African economies were dealt a marginal role in this conversation at best. Meanwhile, economists were turning their focus to the continent, interrogating the historical causes of what they implicitly framed as the ‘African exception’: the only world region that was plagued by persistent poverty.

In his landmark article ‘New economic history of Africa’, Hopkins sounded the alarm-bell, pointing out that economists were producing ‘new’ narratives of African economic development which had largely escaped the attention of African historians.Footnote 13 He called for historians’ (re-)engagement with the new ‘truths’ that were being produced by scholars that used highly innovative, but very different types of research methods to explore questions of major historical importance, including the issue of African poverty. Hopkins's assessment of this literature was milder than Gareth Austin's, who warned that the principal methodological tools employed by economists risked producing superficial narratives at best, and flawed ones at worst.Footnote 14

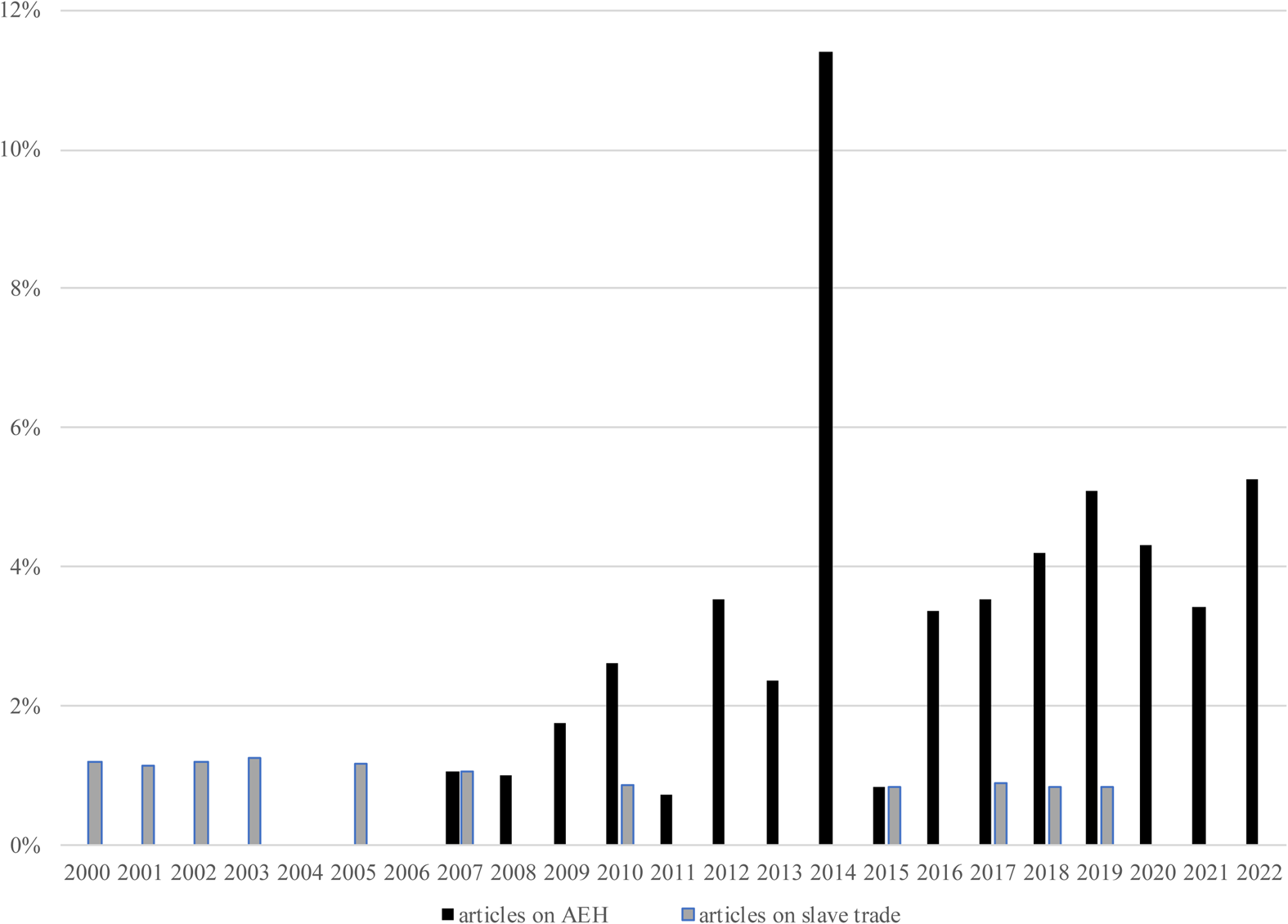

What Austin and Hopkins could not foresee is that the ‘new’ economic history of Africa would take such a steep flight (see Fig. 1) in the decade following their publications — 2008 and 2009, respectively. The African Economic History Network (AEHN) that was founded in 2011 by a group of 9 scholars from mostly European and South African universities (including Austin), currently has over 500 members worldwide and serves as a platform to foster communication, research, and teaching on long-term developments in African economies.Footnote 15 The AEHN has a well-read blog, a working paper series, a bimonthly newsletter, an open access textbook, and organizes an annual meeting which grew from 20 paper presentations in 2012 to over 90 presentations in 2019 (the last pre-COVID meeting). Other initiatives have blossomed as well, including the foundation of the research group ‘LEAP’ at Stellenbosch University in 2015.Footnote 16 Additionally, the journal African Economic History expanded its capacity to publish articles in 2017, going up from one to two issues per year.

Fig. 1. Share of articles published in the top four economic history journals on African economic history and the slave trade, 2000–21.

Sources: The top four include the Journal of Economic History, Economic History Review, Explorations in Economic History, and the European Review of Economic History.

Notes: The peak in 2014 reflects the special issue on the ‘renaissance’ in African economic history in the Economic History Review. The figure contrasts articles on African economic history with those on the slave trade to highlight that the presence of the latter category has been more consistent throughout the years, whereas the former shows a clear uptick. We exclusively counted full-length research articles for this table, and did not include comments or other types of reviews.

However, a shared definition of what was ‘new’ as opposed to ‘old’ failed to take root, and alternative labels were used, either referring to the ‘renaissance’ of African economic history, the birth of ‘causal history’, the ‘data revolution’, or the rise of ‘persistence studies’.Footnote 17 With the benefit of hindsight, we believe that it is useful to divide the ‘new’ quantitative economic history of Africa into two branches. For want of better labels, these may be referred to as African economic history and African historical economics.

This distinction not only captures a contrast in research methodologies and approaches between the two branches, but also, and more importantly, a contrast in knowledge objectives. Historical economists tend to frame history as a ‘laboratory’ stacked with ‘natural experiments’ that can be exploited to test social science theories, or (in)validate development narratives formulated by earlier generations of historians. Historical economists that work on Africa chiefly aim to identify to what extent historical events and ‘treatments’ (for example colonialism or the slave trade) can explain present-day variation in African socio-economic development (for example income levels, trust, or institutional ‘quality’).Footnote 18 The contributions of this strand of literature, which is largely nurtured by economists who apply cutting-edge econometric techniques and target the leading economics journals, was recently surveyed by Stelios Michalopoulos and Elias Papaioannou in the Journal of Economic Literature.Footnote 19

We instead, put the spotlight here on the work undertaken by scholars who self-identify as quantitative economic historians. This branch is primarily interested in understanding African history and conceptualizes historical development as an open-ended, multifaceted process of change. Moreover, where historical economists tend to view statistical results as the endpoint of their analyses, for economic historians, data are oftentimes a starting point to motivate and sharpen questions that are not easily — let alone exclusively — answered by quantitative evidence. Hence, unlike historical economists, whose work concentrates on econometric hypothesis testing, the quantitative approaches of African economic historians tend to be based on carefully constructed descriptive historical statistics that are interpreted with the use of qualitative analyses, and therefore more commensurable with traditional historical inquiry.Footnote 20 As a corollary, economic historians also tend to treat their primary sources with a more critical eye than many historical economists do. The ‘new’ African economic history thus operates more in a continuation of the older school that gained momentum in the 1960s, but it does so by applying and adapting a variety of quantitative and comparative methods to African contexts; methods that were often originally designed to study economic developments in other parts of the world. What do these methods have to offer and how well do they fit diverse African contexts?

Long-run growth trajectories

Questions about why and how economies grow, contract, diversify, diverge, and converge are at the heart of the economic history discipline. Historical national income accounts (GDP estimates) form the basis for analyzing processes of economic change over the long run. While the World Bank and the IMF provide systematic national income estimates for the post-1960 era, series that span centuries rather than decades are typically constructed by economic historians.Footnote 21 African economies have long been absent from the largest historical national income databases, including the Maddison database and the Penn World Tables.Footnote 22 Not only has the lack of such comparable statistics made it more difficult to study African development pathways in global comparative frames, it has also allowed entrenched assumptions about the historically static nature African economies and persistent poverty in the region to last.

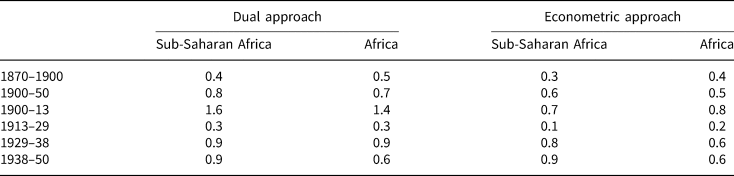

Leandro Prados de la Escosura and Morten Jerven were the first to remedy this void, picking up the thread of a handful of older studies.Footnote 23 To estimate continent-wide real per capita GDP growth for 1870–1950, Prados de la Escosura used two approaches: the ‘dual approach’ and the ‘econometric approach’.Footnote 24 The ‘dual approach’ exploits population estimates and trade data to make conjectures about long-term economic growth. The assumption here is that the export sector determines the pace of income growth (or decline), and that the domestic sector moves in line with population growth. The ‘econometric approach’ uses the statistical relationship between observed GDP per capita growth and income terms of trade growth in a period for which both series are available (that is to say, 1950–90), to then backward extrapolate GDP growth trends for 1870–1950 on the basis of colonial trade reports. The results of both methods are shown in Table 1, and essentially perform a sensitivity check on each other. They suggest that African economies have, on the whole, been expanding for 80 years between 1870 and 1950, with particularly strong rates of growth in the years before the First World War (1900–13), a modest rate of growth in 1913–29, and surprisingly strong growth during the Great Depression era (1929–38).Footnote 25 Jerven's growth estimates for the Gold Coast underscore this picture, albeit with somewhat higher growth rates for the interwar years.Footnote 26

Table 1. Annual GDP per capita growth rates in Africa, 1870–1950 (in per cents)

Source: Prados de la Escosura 2012, ‘Output per head’, 22, Table 2.

In a more recent study of economic growth in eight British African colonies, Stephen Broadberry and Leigh Gardner have applied a more thorough accounting method, taking a wider range of quantitative sources into account, including public sector expenditure, industrial output, real wages, and transportation.Footnote 27 They provide GDP estimates at a sector level, which are subsequently aggregated to ‘national’ levels of per capita GDP (that is to say, colonial levels). Their series reveal considerable cross-colony variation in income levels and growth rates, but their results corroborate the view that Africa experienced repeated episodes of economic growth before major parts of the continent underwent a protracted downturn in the 1970s–90s. Recent work by Denis Cogneau, Yannick Dupraz, and Sandrine Mesplé-Somps on Francophone Africa has also used complementary approaches to cross-check the findings. Their study is especially welcome as the initial push of the ‘new’ economic history of Africa had a disproportional focus on former British territories.Footnote 28

There are good reasons to be cautious about the accuracy of all of these estimates, as the construction of historical GDP series requires the use of an accounting framework that was originally designed to measure productivity growth in Western industrializing economies.Footnote 29 The fact that a significant — albeit in many countries declining — share of African income was either generated through non-marketed production within households, or produced within households and sold informally, suggests that this framework is especially ill-designed to capture African economic realities. In a similar vein, the income that was generated in the expanding informal sectors does not enter into official records, even though there are again ways to correct for this omission.

Additionally, these macroeconomic trends hide a lot of variation in the quality of the data that underpin these GDP series. One major concern is the fact that they are built on weak demographic data, especially before 1950.Footnote 30 To circumvent the systematic underestimations of colonial population censuses, these per capita figures of national output rely on new population series that are based backward projections of a reliable post-1950 population benchmark level. Patrick Manning has made conjectures about population trends for 1850–1960 by assuming ‘default rates’ of African population growth based on more reliable population censuses in that period from British India. He adjusted these default growth rates with a number of so-called ‘situational modifications’ to factor in the demographic effects of African slave trading, famines, epidemics, and colonial disorder. Manning's data and estimation procedure have been contested and revised by others.Footnote 31 As recently shown by Sarah Walters, an especially promising route to further fine-tune such series is that of ‘moral demography’: an approach that combines the quantitative techniques of demographers with culturally-informed readings of the context in which the statistics were produced and existed.Footnote 32 Nonetheless, the challenges of reliable population data illustrate how the results of national income studies are partly contingent on the choices made between competing demographic data series.

A second major concern is the reliability and/or availability of statistics for agricultural production. The lack of colonial bureaucratic capacity, combined with racist assumptions about the ‘unproductive’ nature of African farming, means that estimates for the less commercialized parts of the rural sector are either absent or based on misguided ‘guesstimates’. Africa's ‘new’ economic historians are well aware of these pitfalls and the assumptions that have to be made to compensate for such data limitations. A makeshift solution to the lack of consistent and reliable data on agricultural output and informal services is to assume that these sectors grew in line with the labor force, but did not grow on a per capita basis. While such assumptions still resonate with the notion of a fairly ‘static’ subsistence sector, they are generally regarded as ‘conservative’ for the purpose of national income accounting, as they do not inflate growth rates. In other words, early twentieth-century GDP growth may have been even stronger than has been documented by these conservative estimates. While these strong assumptions are thus defendable in light of the exercise at hand, such make-do solutions signal that more work needs to be done on the relationship between subsistence farming and commercial agriculture, and on the size, nature, and development of informal sector activities.Footnote 33

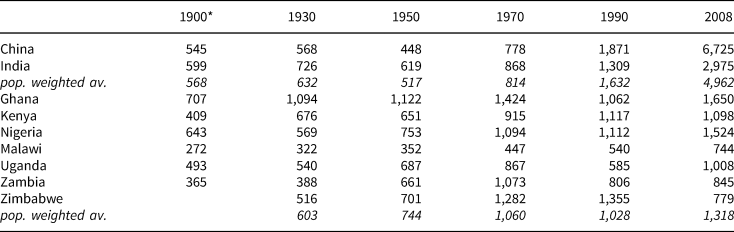

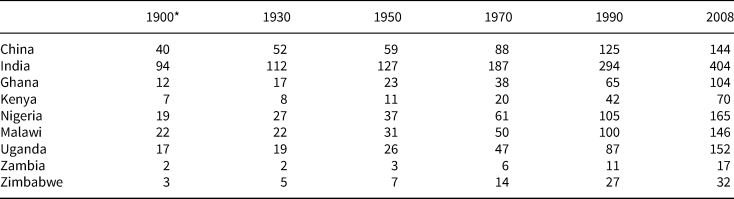

Despite the inevitably large margins of error, long-term national income series offer an indispensable reference framework for analyses of structural economic and social change. Only with these macro-data at hand can scholars begin to assess the opportunities for occupational mobility and living standard improvements at a more aggregate level, and how these in turn may have affected economy-wide distributions of income and wealth (more on this below). GDP series are also crucial to place African economic development in global comparative perspective. For example, one important insight from these new national accounts is that the Great Depression of the 1930s seemed to have had a milder impact on African economies than on Asian economies. Additionally, the extended GDP series have provided (much needed) pushback on the popular notion that sub-Saharan Africa has been the world's poorest region since time immemorial; an implicit assumption that still looms large among policy makers, media, and many social scientists. As shown in Table 2A, from a macroeconomic comparative perspective, many sub-Saharan African countries tended to be significantly wealthier than China or India by the mid-twentieth century. The table also reveals how African economic growth started to slow right at a time that Asian economic growth began to accelerate.

Table 2A. GDP per capita in African and Asian economies, 1900–2008 (benchmark years, in 1990 Geary-Khamis dollars)

Source: GDP for China and India: Maddison Project Database v. 2010. GDP for African countries: Broadberry and Gardner, ‘Economic growth’. Population estimates before 1950 for China and India: Maddison Project Database v. 2010. Population estimates before 1950 for Africa: Frankema and Jerven, ‘Writing history backwards’. Population estimates for 1950 and beyond from the UN Population Division.

Notes: *The year 1900 refers to 1904 for Kenya and Malawi, and to 1906 for Uganda and Zambia.

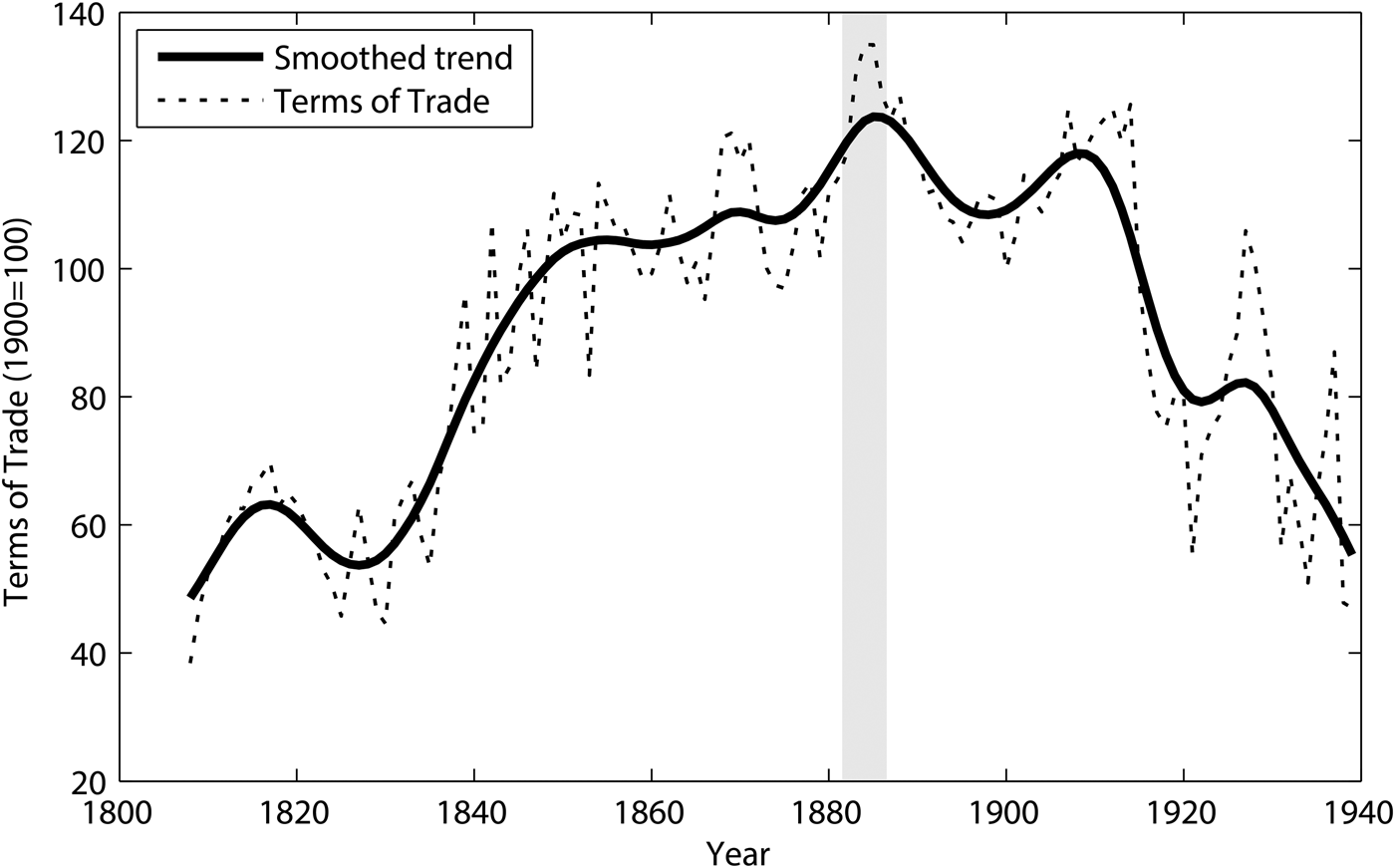

Fig. 2. Terms of trade for British and French West Africa, 1808–1939

Source: Frankema, Williamson, and Woltjer, ‘An economic rationale’, 247, Fig. 4.

Notes: This figure shows the pattern for West Africa. A similar pattern was found for East Africa.

Estimates of per capita GDP, however, can only get us so far when making comparisons between different economies. For one, these aggregate national income statistics mask significant regional variation in economic activity within economies. Second, since GDP per capita levels by definition present economic output per head of the population, they do not reflect the overall ability of an economy to sustain human populations. In this light, the income estimates of Table 2A obscure the much higher population densities in India and China (Table 2B), which corresponded with more intensive forms of agriculture, higher rates of urbanization, and greater occupational diversification. Third, national income estimates in and by themselves give few insights into the drivers of economic growth, and the sustainability of it. Finally, while GDP per capita estimates are a rough proxy for comparative living standards, they do not tell us anything yet about the distribution of economic surpluses. We will return to some of these aspects in the next two sections.

Table 2B. Population densities in African and Asian economies, 1900-2008 (benchmark years, people per squared km)

Source: Population estimates before 1950 for China and India: Maddison Project Database v. 2010. Population estimates before 1950 for Africa: Frankema and Jerven, ‘Writing history backwards’. Population estimates for 1950 and beyond from the UN Population Division. Land area from the World Bank, World Development Indicators, ‘Land area (sq. km)’.

Notes: *The year 1900 refers to 1904 for Kenya and Malawi, and to 1906 for Uganda and Zambia. Ideally the geographical measure would be land that is suitable for human settlement, but using overall land area as a rough approximation does not meaningfully alter the orders of magnitude (of comparatively low historic population densities in most parts of Africa) in this table.

Trade and investment

Gareth Austin's ‘Resources, techniques, and strategies’ may be considered as the landmark study on the drivers of long-term economic growth in Africa south of the Sahara. In this article, Austin redefines the logic of the land-extensive path of growth that characterized much of sub-Saharan Africa between 1500 and 2000.Footnote 34 He argues that ecological and demographic conditions have posed severe constraints on the exploitation of surplus land, but that growth was nevertheless possible because of cumulative possibilities to shift local production possibility frontiers outwards. First, seasonal variation in the demand for labor allowed for expanding production in the low (dry) season (for example, handicraft production). Second, the introduction of new cultigens from Asia and the Americas resulted in more secure food supplies and possibilities to reap ‘forest rents’ from new cash crops such as cocoa, rubber, or tobacco. Third, Austin points to the much-neglected role of fixed capital formation, which mostly resulted from labor investments in land improvement. Ultimately, the high land-labor ratios that shaped African production strategies and choice of technology in agriculture and handicrafts, were upended by this long-term process of economic and demographic expansion. Indeed, by the start of the twenty-first century, labor was no longer the scarce production factor.

By taking indigenous resources, techniques, and strategies as his point of departure, Austin's synthesis avoids overly Eurocentric accounts of long-term African economic development that have become popular among some historical economists.Footnote 35 At the same time, his endowments-oriented thesis offers a clear economic logic for the prevalence of slavery and other forms of labor coercion without denying the impact of external forces on the contraction (for example, slave exports) and expansion (for example, imported crops and mechanized transportation) of African economies over time.

New studies on African trade patterns have shed further light on the intensity and nature of the continent's land-extensive growth path. Compared to GDP, commodity trade analyses offer a narrower lens on long-term economic development, but have the advantage that they can be extended further back in time and are likely to be more accurate.Footnote 36 Recent work that has quantified terms of trade — the ratio of export to import prices — for large parts of Africa since 1800, has revealed two major insights.Footnote 37 First, the scramble for Africa occurred at a moment when export prices for African commodities reached a peak after decades of rapid increases (Fig. 2). While the rising profitability of African export commodities was certainly not the only motivation for formal imperial control over Africa, this new dataset sharpens our understanding of the economic context in which the transition to colonization took place.

Second, right after 1885, a sharp and prolonged decline of the terms of trade set in, which — interrupted by a short-lived recovery in 1900–13 — continued until the eve of the Second World War. As declining relative prices were compensated for by raising export volumes, Africa's colonial economies became entrenched in a specialization pattern of agricultural and mineral commodity production that ran counter to global price movements. To what extent this path of primary commodity specialization was logical in view of prevailing land-labor ratios, remains up for debate.Footnote 38 We do know, however, that the sharp decline in the terms of trade in the interwar period were felt in other parts of the global South as well.Footnote 39

Klas Rönnbäck and Oskar Broberg have underlined this picture by analyzing the direction, composition, and profitability of capital investments in Africa by companies listed at the London stock exchange for the century 1869–1969.Footnote 40 Their book offers detailed insights into the flows of foreign capital that poured into Africa, as well as the profits that were extracted. The authors show that roughly three-quarters of (predominantly British) investments went into mining activities in Southern Africa, and especially South Africa. Their calculations reveal a real average annual rate of return on investment of 5.9 per cent, which is not extraordinarily high compared to returns that were made outside Africa, but given the long span of time such rates of return were substantial nonetheless.Footnote 41 The gap between success and failure was large, however. Only 16 per cent of the companies that invested in Africa and were once listed on the London stock exchange were still present in 1969; the great majority went bankrupt before that date.Footnote 42 Investors in West and East Africa were, on the whole, confronted with net losses while a handful of big conglomerates in South and North Africa (for example, respectively, De Beers and the Suez Canal Company) harvested significant profits. This geographical gap also reflects the high profitability of investments in mining (7.1 per cent), as opposed to investments in plantation agriculture and other consumer commodities (1.9 per cent).Footnote 43

Colonial states and European trade companies, however, did benefit from African engagement in cash crop production and sought to promote it with varying combinations of coercion and assistance. Several scholars have made new attempts to set up systematic comparative analysis within or beyond Africa, in order to explain why particular crops such as rubber, cocoa, coffee, and cotton failed to develop in some areas or in some periods of time, while being a ‘success” in other areas or periods. Explanations have emphasized the subtle combinations of seasonal labor constraints in relation to climatological conditions, land-tenure institutions, the (limited) capacities of the colonial state, and the competition or complementarity between food security and export crop dependence.Footnote 44

Federico Tadei has estimated the rates of extraction that were generated by state-backed trade monopolies. Even though trade tariffs were modest and most charges were on imports rather than on exports, European trade companies were able to manipulate buyer prices and extend their profit margins. By measuring the gap between prices that monopsonist trade companies paid to mostly indigenous cultivators in French Africa and the prices that would prevail in a hypothetical competitive market, Tadei has estimated an annual 2 per cent loss of GDP between 1898–1959.Footnote 45 An annual loss of 2 per cent implies that, had prices not been manipulated to growers’ disadvantage, the size of the economy in 1959 would have been 3.3 times larger. In another study that includes British trade companies, he showed that these monopolies were more effective in West Africa than in (British) East Africa, which he suggests is due to the political influence of settler farmers in the latter region that limited the possibilities of price manipulation.Footnote 46

All in all, studies of GDP, trade, and capital investment help us understand how African economic growth was intertwined with colonial extraction, and how these processes were contingent on market interventions by states, companies, and settlers. The main shortcoming of these analyses though, is that they offer a one-sided perspective on the process of economic growth. Trade records typically only contain sea-bound trade, and exclude internal movements of commodities and people. The internal trade in slaves, and the mobilization of food and non-food commodities as part of export specialization processes, have to be explored via alternative historical sources that are less comprehensive and require a more eclectic research strategy. While stock exchange data reveal a great deal about the operations of big successful companies and the profits they were after, they have little to say about African entrepreneurship, or the reasons why colonial enterprises failed when their expectations met with African realities. Perspectives from within are thus essential to complement these quantitative approaches.

Quantitative approaches to labor history

Labor and the scarcity of labor in relation to land have long been a central theme in African history.Footnote 47 Perhaps more than any other subfield, labor history intersects with a plethora of forces that shaped the lived experiences of Africans. Historical labor relations in African societies have been diverse and fluid, and have long been characterized by various forms of labor coercion, including the raiding and trading of enslaved people. The recent volume on the General Labour History of Africa — a joint publication by editors Stefano Belluci and Andreas Eckert with the International Labor Organization in light of its centennial — is a good illustration of the vibrant and multifaceted nature of African labor history.Footnote 48 The over 700-page volume touches on several central subthemes, including the nature and sector of work, the social and family systems in which work was embedded, and the position of workers vis-a-vis the state and international governance bodies. Yet, the integration of recent work done on labor issues by Africa's ‘new’ economic historians is notably small, and underlines the ongoing gap between qualitative and quantitative approaches to labor history. This is unfortunate, as the topic of labor has numerous measurable components, in relation to, for example, production and transportation costs, living standards, human capital formation, gender inequalities, and labor migration. Indeed, the economic and social implications of historical labor scarcity, as well as the ongoing transition to labor abundance (Table 2B), can in part be revealed through quantitative and comparative approaches.

One central question that economic historians across regional specializations have been working on concerns the extent to which historical GDP growth translated into purchasing power increases of wage workers. The development of ‘real wages’ (nominal wages corrected for price levels) in nineteenth-century Britain has been one of the most fiercely debated topics in the scholarship on the Industrial Revolution.Footnote 49 Yet, the large variation in consumption patterns across and within world regions long inhibited spatial and temporal comparisons of real wage levels and trends. In the early 2000s (in the context of the Great Divergence debate), a new method was developed to facilitate large-scale comparative research on real wages, which was subsequently applied to African countries a decade later.Footnote 50 At the core of this new real wage method is the construction of a hypothetical consumption basket that contains the bare necessities for human survival, but allows for dietary variations over time and across space. With these baskets standardized at a baseline level of per capita caloric and protein consumption, the purchasing power of wage income is expressed as a ‘welfare ratio’: the total number of family subsistence baskets that can be purchased from an average annual wage income, sufficient to maintain two adults and three children.

For comparative purposes, the wages usually refer to male unskilled urban workers. This method has been criticized for its imposition of a ‘male breadwinner’ model on historical comparisons of household income.Footnote 51 To be sure, economic historians know that not all families typically consist of two adults and three children, that many did not exclusively rely on male wage income, and that few consumed the precise standardized basket.Footnote 52 Moreover, it is not strictly necessary to focus on urban unskilled male wage workers, for comparisons of female or rural wage workers can also be made with the same approach. What makes the methodology especially valuable is that it follows a similar logic to that of present-day poverty indices, in which nominal daily incomes are also adjusted for the relative price levels of primary consumer commodities to see how they relate to a specific threshold (for example, the US$1.90 a day benchmark). In other words, this method can help to determine the relative purchasing power of any specific category of income earners, as long as the historical data are available to make the estimates.

Uncovering nominal and real wage trends for African workers is especially interesting in the context of the continent's history of labor scarcity (which should create upward pressure on wages) and the pervasiveness of labor coercion practices (which should generate downward pressure on wages). Fig. 3 shows some of the ‘welfare ratios’ (that is to say, globally comparable real wage levels) that have been constructed over the last decade for various African cities and mining areas for the period 1900–65.Footnote 53 While it should be kept in mind that these figures refer to an initially small but growing section of the labor force that was employed in urban economies, these series corroborate the view that aggregate welfare growth was real and fairly widespread in different parts of colonial Africa. The series also point to growing spatial inequalities in real wage levels across the region, with purchasing power sticking to subsistence levels in some places, while clearly rising elsewhere. Where initial real wages in Accra and Freetown (West Africa) were substantially above those in Kampala and Nairobi, those of mine-workers in the Central African Copperbelt eventually overtook all. When placed in a global comparative perspective, West African real wage levels were up to three times higher than those in many Asian cities at the time.Footnote 54

Fig. 3. Welfare ratios of unskilled workers in African capitals and mines, 1900–65

Sources: Frankema and van Waijenburg, ‘Structural impediments’; and Juif and Frankema, ‘From coercion to compensation’.

How have these rapidly rising African real wages been explained? In the context of growing demand for labor by expanding export sectors and cities in a context of endemic labor scarcity, African workers were — at least in theory — able to secure higher wages than workers in more densely populated parts of Asia, such as India and China. However, such upward pressure on wages only translated in actual higher incomes in places where colonial interventions in land and labor markets were relatively mild.Footnote 55 Indeed, in much of (British) East Africa, high land-labor ratios did not translate into high real wages. Part of the observed ‘East-West divide’ in African welfare ratios may also have to do with the lower market value and higher transportation costs of the ‘mass-export’ crops produced in Uganda (such as cotton) which would have rendered higher wages economically unfeasible, or the absence of such crops in Tanganyika which resulted in lower demand for wage workers to begin with.Footnote 56

While the trends shown in Fig. 3 are mainly based on data from the British colonial Blue Books, other sources such as population censuses, agricultural surveys, and local newspapers have also been used to construct new series and double-check existing ones.Footnote 57 This real wage method has been further adapted to the African context to gauge developments in the non-wage incomes of rural households, by making various assumptions about land productivity and opportunities to sell part of the harvest against prevailing market prices.Footnote 58 Such estimates for Uganda reveal that smallholders were, in good times, mostly better off (materially) than the wage workers that flocked into the expanding urban economy of Kampala, including many Rwandese immigrants. Real incomes were thus not only shaped by relative factor proportions and the institutions governing land and labor markets, but also by the political economy of urban development, the opportunities of commercial agriculture, and the presence or absence of a severely deprived immigrant population.

Comparative analyses of wage differentials have shed light on a range of other long-run trends and patterns in African labor markets as well, including the movement of millions of Africans during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries during the so-called age of ‘intra-African migration’ (c. 1850–1960). Building on earlier strands of economic historical research into wage gaps between sending and receiving regions, new work on labor migration has shown how it made economic sense for African labor migrants to travel large distances, even in contexts where the margins were razor-thin. Wage differentials can explain the seasonal movements of Burkinabe to the cocoa belt of Ghana, of Rwandan migrants into the cotton fields of Buganda, and of rural dwellers in different corners of Southern Africa to the major mining areas of the Rand and the Copperbelt.Footnote 59 While income gaps are of course not the sole component of the ‘opportunity gaps’ that migration scholars focus on, these data are a major step forward in understanding the drivers between the ebb and flow of voluntary labor migrations.Footnote 60

While economic historical research on African real incomes and mobility have expanded our knowledge base, quantitative approaches clearly have limitations in what they can capture. This is especially evident in the dearth of economic historical work on the emergence of the precariat and the related decline of organized labor in the closing quarter of the twentieth century.Footnote 61 The development towards formal wage labor as the dominant form of labor relations came to a halt with growing numbers of African men and women toiling in the rapidly expanding (urban) informal sectors. This had major implications for the development of occupational structures, labor skills, and household revenue portfolios. Collecting standardized quantitative information on informal sector labor, however, has been challenging, let alone data that is continuous and reliable enough to explore patterns with the aid of statistical analyses. If the ‘new’ African economic history ultimately proves to be more data-driven than question-driven, it will fail to grasp important aspects of long-term African labor dynamics.

Inequality and social mobility

The ‘new’ economic history of Africa has also probed into questions of income and wealth distribution and social mobility. Studies of long-term income inequality have mostly adopted a so-called social tables approach. A social table ranks the various social classes (or groups) in a particular society (or population) from rich to poor. For each group that has been distinguished, scholars estimate its percentage share in the total population and combine this with the estimated mean annual income of the members of each group. These data then allow for the computation of Gini-coefficients and Theil-coefficients, which express the level of inequality in society on a scale of 0 to 1.Footnote 62 The social tables approach has been around for long and is particularly helpful to explore the distribution of income in preindustrial societies that were characterized by low degrees of social stratification and have limited historical sources on individual/household income levels.

The construction of social tables for African societies has taken a steep flight in recent years.Footnote 63 Fig. 4 show that simple narratives of colonial capitalism spurring inequality are difficult to maintain. Even in the small sample of countries for which long-term trends in inequality have now been documented, the trends diverge dramatically. The rising levels in inequality that are observed in the social tables for colonial Ghana and Botswana have been interpreted as the effect of increasing export revenues from cocoa and cattle, the mainstays of indigenous capitalist expansion. The structural gap in inequality levels between Kenya and Uganda, in turn, appear to reflect the impact of different colonial institutions. While African entrepreneurship in Kenya was long curbed by a politically influential class of European settlers, Uganda was ruled (indirectly) through a dominant ethnic group (the Ganda) that stimulated indigenous farmers to engage in the commercial production of coffee and cotton. Different inequality levels in Ghana and Uganda also show how varying capitalist systems generated different levels of income concentration at the top. Whereas cotton farmers in the Ugandan regions of Busoga, Teso, and Lango were virtually all smallholders, the cocoa planters in Ghana were more stratified, with some elite farmers having accumulated considerable wealth through palm oil and cocoa production.

Fig. 4. Income inequality estimates based on social tables for Botswana, Côte d'Ivoire, Ghana, Kenya, Senegal, and Uganda, 1920–70

Source: E. Hillbom, et al., ‘Measuring historical inequality in Africa: What can we learn from social tables?’, African Economic History Network Working Paper, No. 63 (2021); which is, in turn, based on social tables for Botswana from Bolt and Hillbom, ‘Long-term trends in economic inequality’; Côte d'Ivoire and Senegal from Alfani and Tadei, ‘Income inequality in French West Africa’; Ghana from Aboagye and Bolt, ‘Long-term trends in income inequality’, and Uganda from De Haas, ‘Reconstructing income inequality’.

Notes: All Gini-coefficients are calculated for the income distribution of individuals active in the workforce. For discussion of using different ranking populations, see De Haas, ‘Reconstructing income inequality’ and Hillbom, et al., ‘Measuring historical inequality’.

There are two major drawbacks to the social tables methodology. First, the inequality level estimates are driven by income differences between social groups or classes, and assumes that intra-group inequality is limited. This assumption can be problematic if income pyramids are in flux in moments of rapid economic diversification and structural change. The assumption can also be problematic for societies where farmers form a large proportion of the working population, while their income differences are hard to assess. Intricate knowledge of farmers’ household subsistence strategies, including migratory incentives, and how these have changed over time are crucial to address this issue.Footnote 64 Second, and not exclusive to social tables, colonial and postcolonial sources often fail to offer consistent data on incomes and labor force composition. All of this is not a reason to abandon attempts at quantification of inequality, but it does oblige economic historians to be transparent about the assumptions they make and to discuss the possible impact such unknowns may have on their conclusions. This growing strand of literature in particular would benefit from closer dialogue with social and cultural historians of Africa.

In the study of inequality too, diverse quantitative approaches allow for a variety of perspectives. Measures of top-income or top-wealth shares, which are usually derived from historical tax records, have recently been constructed to gauge long-term trends in inequality in parts of sub-Saharan Africa (Fig. 5). One advantage of this approach is that this indicator is easy to interpret: the share of the top-10, top-1, or top-0.1 per cent of income earners (or asset-owners) in total income precisely reveals the part of the pie appropriated by the rich or even the super-rich. This approach to inequality was originally advanced by Anthony Atkinson, and has been popularized by Thomas Piketty, after having been successfully applied to a large range of Western economies.Footnote 65

Fig. 5. 0.1 per cent top-income share in 10 African countries, 1930–84

Sources: South Africa from F. Alvaredo and A. Atkinson, ‘Colonial rule, apartheid and natural resources: top incomes in South Africa 1903-2005’, OxCarre Working Paper, No. 46 (2010); Ghana, Kenya, Malawi, Nigeria, Tanganyika, Uganda, Zambia, Zanzibar, and Zimbabwe from A. Atkinson, ‘The colonial legacy: Income inequality in former British African colonies’, WIDER Working Paper, No. 45 (2014).

The usefulness of a top-income approach hinges on the reliability of estimates of ‘total income’ and the completeness of tax records. In cases of large-scale tax evasion, top income shares can easily be underestimated. Yet, that the declining trends observed in the 0.1 per cent top-income shares between 1930 and 1970 (Fig. 4) appear to run opposite to the rising trends observed in the social tables (Fig. 5) is not necessarily underscoring data problems. It is precisely the confrontation of such varied approaches and data that incentivizes economic historians to dig deeper to tease out what causes these trends and how they may be reconciled.

Beyond the more technical aspects, one can and must debate the meaning of such measures in contexts in which private ownership is not necessarily the norm, or when part of the wealth is stored in people (including the income derived from control over labor power).Footnote 66 Studies that explore the changing cultural meaning of wealth within different African societies have argued, in line with Polanyi, that historically giving gifts was a better marker of status than their receipt, and that there has been a shift away from economic relations based on reciprocal obligation towards those based on the retention and accumulation of wealth.Footnote 67 Clearly, these are issues that warrant mutual engagement. In addition, studies on culturally embedded forms of elite corruption can also be helpful in historicizing the degree and nature of kleptocratic behavior and pervasiveness of systems of patronage.Footnote 68

While social tables and top-income shares allow scholars to explore inequality and social mobility at the macro-level, new research on the basis of micro-level data — taken from population censuses, household surveys, and church registers — has taken off too. Felix Meier zu Selhausen has used marriage registers collected from Protestant churches in Ghana and Uganda to shed light on gender differences in age, literacy, and numeracy at the time of marriage. Additionally, these marriage registers contain valuable information on the degree of occupational mobility of brides and grooms in relation to their reported fathers’ occupation.Footnote 69 Although church members cannot be taken as representative for the population at large, this type of sample-data does offer opportunities to compare recorded literacy rates in rural parishes with urban parishes, and to trace the evolution of intergenerational changes in the occupational structure of church members.Footnote 70 Such micro-level data are also a rich source to study Christian movements in their own right, including the health and educational institutions that were part of the missionary wave.

In the historical economics literature, there has been a surge in studies that relate the diffusion of mission stations to specific development outcomes today. In an article that criticizes much of the evidence for the supposed long-term effects of missionary activity, Remi Jedwab, Felix Meier zu Selhausen, and Alexander Moradi have listed over 50 published papers since 2010.Footnote 71 One of the points that this vast literature in historical economics agrees on is that Protestant missions were more inclined to promote literacy and gender equality than Catholic or Islamic missions. More contested, however, are interpretations of the origins and long-term effects of missionary movements. Many studies have unduly framed missionary schooling as a ‘European’ or ‘colonial’ legacy, using maps of mission stations compiled by Western church organizations to argue that places with early missionary involvement are today still characterized by higher levels of social and economic development.Footnote 72 Revisionist studies have, in contrast, highlighted how colonial governments invested very little in private mission schools, and that the Africanization of the mission in terms of initiative, spatial diffusion, labor input, teaching capacity, and school maintenance was of critical importance for the spread of mass education in Africa. Moreover, when many of the smaller African-run missions that are excluded in many of the European sources (mainly missionary atlases), are included in the econometric analysis, it appears that the statistical relation between missionary schooling and economic development may very well be driven by the fact that mission stations were primarily established in healthier (malaria-free), more accessible (railroads), and richer places (cash-crop producing areas) to begin with.Footnote 73 In econometric parlance, this renders such analyses subject to problems of endogeneity, which is another way of saying: in need of further investigation.Footnote 74

African economic development in global perspective

Despite the fact that African labor supplies have grown enormously over the last century, and labor costs have declined relative to many other parts of the world, African economies did not become the ‘workshop of the world’ in ways that several of their Asian counterparts did. So far, economic historical research on Africa's development patterns and potential in the postcolonial era has remained limited. First-order questions on the drivers of the deep and protracted depression that characterized African economies in the closing decades of the twentieth century, and the more recent economic boom years have been largely left to development economists and political scientists. What does it mean to be economically ‘behind’ in a context of on-going globalization, accelerated demographic growth, and technological change? Are the forces of global market integration, international competition, and technology diffusion working in favor of African economies or have they instead closed windows of opportunity? Why has Africa not been able to replicate Asia's development model of agricultural intensification and export-led industrialization?

Social scientists have interpreted the remarkable post-1970 divergence between sub-Saharan Africa and major parts of southern and eastern Asia along three main (continent-level) lines. First, they have emphasized how Africa lacked the phase of rapid agricultural productivity growth that preceded Asian industrialization. Put differently, Africa did not have its own version of a ‘Green Revolution’.Footnote 75 Second, they have argued that African labor forces were insufficiently educated for a transition to competitive, market-driven industrialization. Scarce supplies of high-skilled workers made the adoption of new technologies costly, and conversely, lowered the potential efficiency gains.Footnote 76 Third, social scientists have drawn attention to a range of institutional barriers that would have smothered the private entrepreneurship needed to build up a competitive edge in global markets. Typical examples that are often referred to are insecure property rights, a weak rule of law, corruption, and redistributive pressures following from deeply ingrained ‘sharing cultures’.Footnote 77

Economic historians have only recently joined these conversations, in part building on Alexander Gerschenkron's classic thesis that ‘late’ industrialization poses a distinctly different challenge than ‘early’ industrialization.Footnote 78 While late industrializers do not need to invent new technologies as they can adopt most of it from abroad, they do have to overcome the barriers to technology adoption that delayed their industrial take-off in the first place. Such barriers may range from financial and infrastructural conditions, to education and labor skills, and well-designed and executed industrial policies. In removing such barriers, the literature on the ‘developmental state’ sees an enlarged role for state intervention of the kind observed in Japan, the Asian ‘Tigers’, and more recently in China.Footnote 79 When it comes to the role of the state in Africa's postindependence industrial policy, or more generally, in relation to companies, banks, and different types of industries, there is ample scope for further research that can move beyond one-sided impressions of endemic corruption and kleptocracy.Footnote 80

Austin has argued that the core ideas of ‘late development’ and the role of the state are valuable, but that this needs to be combined with Kaoru Sugihara's framework on how particular factor endowments shape historical development paths.Footnote 81 Sugihara's framework starts from the premise that there are multiple routes towards sustainable growth, rather than just the path taken by the West. Whereas the West's growth path was characterized by capital-intensive industrialization, that of many Asian economies started under a path of labor-intensive industrialization and only became more capital-intensive in a later stage. By seeing both of these different paths as successful adaptations to different factor proportions, Sugihara's view moves beyond traditional Eurocentric interpretations of ‘successful’ development. As most of Africa was historically land-abundant and labor-scarce, specialization in land-extensive commodity production was a logical adaptation to prevailing endowment structures, but it also meant that a direct transition from handicrafts to modern manufacturing was less likely. With land-labor ratios shifting dramatically in recent decades, however, and combined with rapid increases in years of schooling, Austin concludes that labor-intensive, state-led industrialization is now much more likely to occur — at least in some African economies.

Related economic historical work has employed a diachronic comparison to assess whether Asia's rise has made export-led growth more difficult for Africa, by raising global competition for labor-intensive industrial commodities.Footnote 82 What did the global competitive landscape look like for earlier industrializers? Comparing the labor cost gap that existed between Japan and Britain in 1900 — a period in which Japan started to make major inroads into global export markets that were long dominated by the West — reveals that Japan enjoyed a significant labor cost advantage: real wages of unskilled workers in Tokyo were only 10–15 per cent of the rates paid in London.Footnote 83 Present-day wage gaps between African countries and their Asian competitors, in contrast, are much smaller. Ethiopia may be the exception where industries can benefit indeed from even lower wages than those paid in India, Vietnam, or Bangladesh. This means that unless African states are willing and able to engage in significant domestic wage repression — a step at odds with poverty alleviation objectives — most African economies will have to look for other competitive advantages. An alternative and possibly more promising development route would be to focus on Africa's growing domestic markets instead of global export markets, fostering them through investments in infrastructure projects that connect rural areas with urban centers, lowering intra-African trade barriers, and possibly using some targeted protectionist policies to build up infant industries. Recent moves towards the establishment of an African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) are major steps towards that end.

Gazing ahead

Over the last decade, the quantitative study of Africa's economic past has enjoyed an impressive revival among (historical) economists and (economic) historians. Both groups have brought new statistics and methods to the study of long-term African economic development, but with markedly different knowledge objectives and degrees of data sensitivity. The work done by the branch of the ‘new’ economic historians is more in line with the research objectives of readers of this journal, and may in some ways be regarded as the continuation of an older strand of work that flourished in African history in the 1960s to 1980s. The application of new quantitative methods and comparative perspectives by this branch over the last decade and a half has mostly confirmed, partly refined, and at points modified the views that were held some three to four decades ago, but it has also generated two larger pay-offs.

First, new work on historical datasets that are comparable over time and across space have supported the embedding of ‘African paths’ in debates about the making of global economic inequality; debates that have taken steep flight over the past two to three decades. As such, the ‘new’ quantitative African economic history has been a major step forward to anchor Africa in increasingly globally oriented economic historical research agendas, in part through methodological integration. Moreover, the rising output on Africa has also inspired new types of global comparisons, most notably that of ‘South-South’ evaluations.Footnote 84 Such trends help further decenter long-standing conversations in global economic history.

Second, the systematic adoption of comparative analyses has sharpened our understanding of the similarities and differences in the economic experiences of African countries and peoples. Evidence on relative orders of magnitude, whether on demography, income, trade, investment, inequality, or mobility, have revealed both how varied such experiences have been, as well as how certain shared traits underscore Africa-specific development trajectories. The new quantitative and comparative methods that have been used by economic historians are thus valuable complements to the more qualitative and/or more place-, time- and event-specific research approaches that characterize the work of many Africanist historians. These broader economic patterns as well as the different trajectories within Africa, provide new frameworks to situate more intimate accounts of Africans’ lived experiences.

As is, however, the connections between the quantitative approaches of the ‘new’ economic historians and the qualitative research designs of social and cultural historians are — with some notable exceptions — still limited.Footnote 85 This is unfortunate, because major themes in African history such as poverty, agricultural development, capitalism, labor, education, health, and demography, stand to benefit from combined quantitative and qualitative approaches. While this disconnect in part reflects hesitation among Africanist historians, it is also driven by self-imposed restrictions among economic historians, who have hesitated to touch on questions for which no quantitative datasets can be constructed. Not only does this tendency narrow the scope of the topics they research, it also skews the emphasis to the colonial period, and the source base to European records. Such self-induced limitations on the types of questions that can be explored stands in contrast with the long tradition of methodological exploration and innovation that has characterized the field of African history.

That said, the potential for methodological cross-fertilization and moving past such restrictions has grown significantly since Hopkins's wake-up call in 2009. We have sought in this article to bring the historically-minded branch of the new quantitative economic history of Africa to the notice of Africanist historians, because we are excited about the potential opportunities for greater scholarly integration and collaboration in decades to come. Indeed, there are many more African economic historians that have a keen interest in research cooperation than there were a decade ago. While far from exhaustive list, we see several ‘frontier areas’ where collaborative work could deepen our understanding of the long-run transformations that have taken place in African economies.

For one, there is great value in connecting the insights from economic history with those of environmental history.Footnote 86 Whereas certain topics — especially that of fuel and energy — loom large in European economic history, much has yet to be learned about the intersections between African economies, energy management, and the impact on the environment.Footnote 87 Collaborations between economic and social historians, in turn, could deepen our understanding of changing family systems and gender,Footnote 88 the intricacies of colonial and postcolonial bureaucracies,Footnote 89 transportation networks,Footnote 90 or informal economies.Footnote 91 Partnerships with cultural historians could not only elucidate how patterns of consumer behavior and urban lifestyles intersected with larger macroeconomic trends, but also enrich the impersonal accounts of economic historians with ways in which people understood economic change and shaped it in turn. Finally, research on African economies could venture further back in time and explore longue-durée questions on topics such as the evolution of labor relations, urbanization, and state formation, or changing agricultural practices and crop diffusion by expanding cooperation with archaeologists, paleobotanists, and historical linguists. Such collaborations with different methodological branches of African history may prove vital to sustain the ‘new’ branch for a longer period than the ‘old’ branch of African economic history.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Rachel Taylor, two anonymous reviewers, and the editorial board for their comments and guidance. Ewout Frankema gratefully acknowledges support from the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research for the project ‘South-South Divergence: Comparative Histories of Regional Integration in Southeast Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa since 1850’ (NWO VICI Grant no. VI.C.201.062).