The lower Palaeozoic of Belgium has received relatively little attention in comparison to the Devonian and Carboniferous successions, which have been extensively studied since the 19th Century due to their great variety of facies and fossil content and that include classical standard sections of Middle–Upper Devonian and lower Carboniferous strata, with several global stage names still used at the global level by the International Commission on Stratigraphy (Frasnian, Famennian, Tournaisian, Visean). Although largely present in the subsurface, the lower Palaeozoic rocks of Belgium only occur in limited outcrop areas, usually beneath a Silurian–Devonian unconformity (Verniers et al. Reference Verniers, Herbosch, Vanguestaine, Geukens, Delcambre, Pingot, Belanger, Hennebert, Debacker, Sintubin and De Vos2002). Furthermore, the mostly sedimentary successions are tectonically disturbed by both the Caledonian and Variscan orogenies, making them incomplete and poorly preserved. Partly metamorphosed, the sediments provide a fossil content that is generally poor, sometimes absent, in most parts of the thick, monotonous siliciclastic successions present in the ‘massifs’ or ‘inliers’ (Verniers et al. Reference Verniers, Herbosch, Vanguestaine, Geukens, Delcambre, Pingot, Belanger, Hennebert, Debacker, Sintubin and De Vos2002).

The most complete succession displays Cambrian, Ordovician and Silurian siliciclastics in the Belgian part of the Anglo-Brabant Massif, with outcrops in river valleys on the southern border of the massif (e.g., Legrand Reference Legrand1968; Herbosch & Debacker Reference Herbosch and Debacker2018) (Fig. 1). A narrow (about 0.5–4 km) but long (about 65 km) tectonic inlier, historically known as the Bande de Sambre-et-Meuse, also named the Condroz Inlier, displays incomplete Ordovician and Silurian successions in at least four tectonic wedges transported along the Midi-Eifel Thrust Fault (e.g., Hance et al. Reference Hance, Steemans, Goemaere, Somers, Vandenven, Vanguestaine and Verniers1991; Verniers et al. Reference Verniers, Herbosch, Vanguestaine, Geukens, Delcambre, Pingot, Belanger, Hennebert, Debacker, Sintubin and De Vos2002; Belanger et al. Reference Belanger, Delaby, Delcambre, Ghysel, Hennebert, Laloux, Marion, Mottequin and Pingot2012). In addition, four inliers are present in the Ardenne Allochthon (southern Belgium, northern France and western Germany), classically referred to as the Ardenne inliers with siliciclastic successions of Cambrian and Ordovician rocks (Verniers et al. Reference Verniers, Herbosch, Vanguestaine, Geukens, Delcambre, Pingot, Belanger, Hennebert, Debacker, Sintubin and De Vos2002) (Fig. 1). The largest inlier is the Stavelot-Venn Inlier (Fig. 2), extending from southeastern Belgium to western Germany. Affected by both the Caledonian and Variscan orogenies, the Ardenne Allochthon lies just south of the Variscan northern front, thus representing the northwestern part of the Rheno-Hercynian domain (Herbosch et al. Reference Herbosch, Liégeois, Gärtner, Hofmann and Linnemann2020). In terms of palaeogeography, the Cambrian and Ordovician rocks (Fig. 3) in this inlier were deposited in the easternmost part of the Avalonian microcontinent (Domeier Reference Domeier2016; Herbosch et al. Reference Herbosch, Liégeois, Gärtner, Hofmann and Linnemann2020; Cocks & Torsvik Reference Cocks and Torsvik2021; Herbosch Reference Herbosch2021). Fossils are rare, and most of the biostratigraphical information was provided by organic-walled microfossils, mostly acritarchs (Vanguestaine Reference Vanguestaine1986).

Figure 1 Location and schematic geological map of southern Belgium and adjacent countries (modified from de Béthune Reference de Béthune and Fourmarier1954 and Mottequin Reference Mottequin2021). Abbreviations of the inset: G. = Germany; L. = Luxembourg; N. = the Netherlands. Abbreviations: F. = Fault; HSM OTS = Haine–Sambre–Meuse overturned thrust sheets (Belanger et al. Reference Belanger, Delaby, Delcambre, Ghysel, Hennebert, Laloux, Marion, Mottequin and Pingot2012).

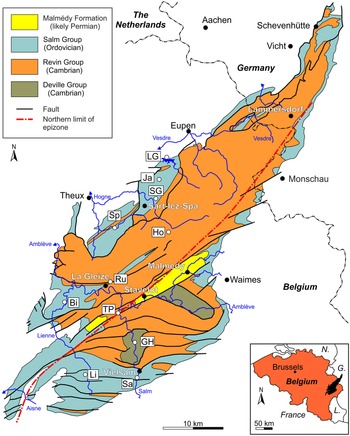

Figure 2 Geological map of the Stavelot-Venn Massif simplified from Geukens (Reference Geukens1986, Reference Geukens1999) and Herbosch et al. (Reference Herbosch, Liégeois, Gärtner, Hofmann and Linnemann2020) (adapted from Candela & Mottequin Reference Candela and Mottequin2023) with indication of the fossiliferous localities cited in text. Abbreviations of the inset: G. = Germany; L. = Luxembourg; N. = the Netherlands. Abbreviations: Bi = Bierleux; GH = Grand-Halleux; Ho = Hockai; Ja = Jalhay; LG = Lake Gileppe; Li = Lierneux; Ru = Ruy; Sa = Salmchâteau; SG = Solwaster (Gospinal); Sp = Spa; TP = Trois-Ponts.

Figure 3 Traditional geochronology and lithostratigraphy (with old subdivisions in italics) of the Stavelot-Venn Inlier (modified from Herbosch et al. Reference Herbosch, Liégeois, Gärtner, Hofmann and Linnemann2020) with indication of the documented reports of fossils and ichnofossils and the discarded/unconfirmed occurrences (except Nereites cambriensis? and Primitia sp. (see Lohest & Forir Reference Lohest and Forir1900) which are insufficiently documented in the literature; see text). The double arrows indicate boundaries between formations of uncertain age. It is important to note that the sedimentary succession is very incomplete and only few intervals provide acritarchs pointing out some age information; most of the age assignments need to be revised urgently. Abbreviations: Gp. = Group; P. = Period.

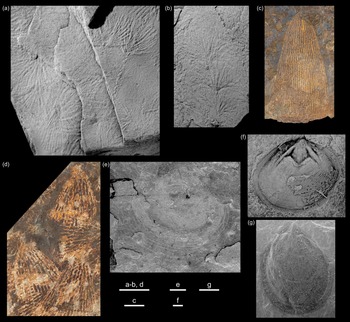

After the original studies in the first half of the 19th Century (e.g., Dumont Reference Dumont1847), more robust stratigraphical investigations with numerous descriptions of fossils followed in the last part of the 19th Century (e.g., Malaise Reference Malaise1866, Reference Malaise1873, Reference Malaise1881), allowing the attribution of some stratigraphic levels to the Cambrian and Ordovician. However, the age of several lithological units of the lower Palaeozoic of the Stavelot-Venn Inlier still remains poorly known, as most lithological units lack fossils. The first records of the enigmatic ichnofossil Oldhamia (Fig. 4a, b) in this inlier are those of Dewalque (Reference Dewalque1874a) and Malaise (Reference Malaise1876a, Reference Malaise1878a). Oldhamia indicated a possible early to middle Cambrian age in the lower part of the succession. This ichnofossil was thus of great importance for the identification of Cambrian rocks in Belgium, and its biostratigraphical use has benefitted from a revision by Herbosch & Verniers (Reference Herbosch and Verniers2011). Nevertheless, representatives of this ichnogenus from the Stavelot-Venn Inlier require taxonomic revision, as is the case for those from the Cambrian of the Rocroi Inlier. To our knowledge, only Corsin (in Waterlot et al. Reference Waterlot, Beugnies and Bintz1973, pl. 1, fig. 1) and Aceñolaza & Durand (Reference Aceñolaza and Durand1984, fig. 1c) illustrated them photographically. Another iconic fossil group is the ‘Dictyonema flabelliforme fauna’ that indicates an earliest Ordovician age in parts of the lower Palaeozoic succession. These planktic graptolites, now attributed to the genus Rhabdinopora (Fig. 4c, d), were recently reinvestigated in detail by Wang & Servais (Reference Wang and Servais2015), after earlier reports and revisions by Graulich (Reference Graulich1963), Bulman (Reference Bulman1970) and Erdtmann (Reference Erdtmann1986).

Figure 4 Ichnofossils (a, b), graptolites (c, d) and brachiopods (e–g) from Cambrian and Ordovician of the Stavelot-Venn Inlier. (a, b) Oldhamia isp., RBINS a14188 (a) and a14189 (b) (IG 9340); Grand-Halleux railway trench, Bellevaux Formation. (c) Rhabdinopora flabelliformis socialis, RBINS a12915; Lake Gileppe (northern bank), Jalhay Formation (Solwaster Member). (d) Rhabdinopora flabelliformis parabola, RBINS a12917; around Spa, Jalhay Formation (Solwaster Member). (e) Acrothele cf. bergeroni, PA.ULg 6464; Trois-Ponts, Wanne Formation (from Candela et al. Reference Candela, Marion, Servais, Wang, Wolvers and Mottequin2021) (SEM). (f) Broeggeria sp., RBINS a13489; Spa (route de Sart), Jalhay Formation (Solwaster Member) (from Candela et al. Reference Candela, Marion, Servais, Wang, Wolvers and Mottequin2021). (g) Lingulella lata, RBINS a13490; Solwaster (Gospinal), Jalhay Formation (Solwaster Member) (from Candela et al. Reference Candela, Marion, Servais, Wang, Wolvers and Mottequin2021) (SEM). Scale bars represent 10 mm, except e (0.5 mm), f and g (1 mm).

In addition to publications dedicated to Oldhamia and Rhabdinopora flabelliformis (formerly Dictynonema flabelliforme), a great number of papers have been published in the last two centuries concerning other fossil reports, including findings or simple reports of trilobites, brachiopods (Fig. 4e–g), phyllocarids, bivalves, sponges and other groups. Some of these reports date back from the first geological studies on the lower Palaeozoic of Belgium in the late 19th and early 20th Centuries. For many decades, most of these fossil groups have received little or no attention. Many of the reports have never been verified or revised, although part of the material has been deposited in public collections, such as those of the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences in Brussels, Belgium.

Regarding microfossils, acritarchs, chitinozoans and conodonts have been described (or only mentioned). Most of these published records also need a careful revision, because some of the data are currently outdated, and the biostratigraphical attributions, which are still used in modern literature, should be revised and updated. However, this necessary revision of the microfossils is out of the scope of the present paper.

In the frame of a systematic revision of all lower Palaeozoic inliers in Belgium initiated a few decades ago (e.g., André et al. Reference André, Herbosch, Louwye, Servais, Van Grootel, Vanguestaine and Verniers1991; Verniers & Van Grootel Reference Verniers and Van Grootel1991; Servais et al. Reference Servais, Vanguestaine and Herbosch1993), Verniers et al. (Reference Verniers, Herbosch, Vanguestaine, Geukens, Delcambre, Pingot, Belanger, Hennebert, Debacker, Sintubin and De Vos2002), Herbosch & Verniers (Reference Herbosch and Verniers2013, Reference Herbosch and Verniers2014) and Herbosch (Reference Herbosch2021) carefully revised and correlated all lithostratigraphic units from the Cambrian to the Silurian. In this context, some fossil records of the lower Palaeozoic units of Belgium have been revised in detail or are currently in the process of revision. Such revisions include Ordovician graptolites (e.g., Servais & Maletz Reference Servais and Maletz1992; Maletz & Servais Reference Maletz and Servais1998; Wang & Servais Reference Wang and Servais2015), rugose and tabulate corals (Servais et al. Reference Servais, Poty and Tourneur1997; Mottequin & Poty Reference Mottequin and Poty2025) and trilobites (e.g., Owens & Servais Reference Owens and Servais2007; Laibl et al. Reference Laibl, Servais and Mottequin2023) from the Brabant Massif and the Condroz Inlier, as well as the graptolites from the Stavelot-Venn Inlier (Wang & Servais Reference Wang and Servais2015). More recently the brachiopods from the Brabant Massif, Condroz and Stavelot-Venn inliers are also being revised (e.g., Candela et al. Reference Candela, Marion, Servais, Wang, Wolvers and Mottequin2021, Reference Candela, Harper and Mottequin2025; Candela & Mottequin Reference Candela and Mottequin2022, Reference Candela and Mottequin2023; Candela et al. Reference Candela, Harper, Servais and Mottequinin press; and further work in progress) and the revision of echinoderms of the lower Palaeozoic of Belgium, which were described by Malaise (Reference Malaise1873) and Regnéll (Reference Regnéll1951) (see partial reillustration in Mottequin Reference Mottequin2021), is in progress, although some preliminary work has already been published (e.g., Lefebvre et al. Reference Lefebvre, Candela, Nardin, Servais and Mottequin2024).

The main aim of the present note is to provide a review of all macrofossil reports from the Stavelot-Venn Inlier with, in particular, a critical evaluation of some questionable records that have been published since the 19th Century.

1. Geological setting, litho- and chronostratigraphy of the Stavelot-Venn Inlier

The Stavelot-Venn Inlier (historically named ‘Stavelot Massif’) extends on both sides of the border separating Belgium and Germany and consists of a thick pile of siliciclastic sediments of Cambrian and Ordovician age (Verniers et al. Reference Verniers, Herbosch, Vanguestaine, Geukens, Delcambre, Pingot, Belanger, Hennebert, Debacker, Sintubin and De Vos2002). With a surface exceeding 1,000 km2 it is the largest among the four Caledonian massifs (or inliers) of the Ardenne Allochthon, namely the Stavelot-Venn, Rocroi, Serpont and Givonne inliers (Fig. 1). These underwent a complex palaeogeographic history as they belonged to Avalonia that drifted from Gondwana during the earliest Ordovician (e.g., Cocks & Fortey Reference Cocks, Fortey and Bassett2009; Torsvik & Cocks Reference Torsvik and Cocks2017). The Stavelot-Venn Inlier was carefully mapped in greatest detail for over more than five decades by Geukens (e.g., Reference Geukens1986, Reference Geukens1999). The German part of the inlier was also studied (for a summary see Ribbert et al. Reference Ribbert, Servais and Vanguestaine2002), including investigations during a geological mapping programme (Schmidt Reference Schmidt1954, Reference Schmidt1956) that also provided new fossil discoveries (Schmidt & Geukens Reference Schmidt and Geukens1959). More recently, the Belgian part was also geologically mapped, with additional fossil data (Marion et al. Reference Marion, Geukens and Lambertyin press a, b). A careful review of the geodynamic evolution of the Stavelot-Venn Inlier was provided by Herbosch et al. (Reference Herbosch, Liégeois, Gärtner, Hofmann and Linnemann2020) who, in addition to a literature review, focused on the study of detrital zircons from the Cambrian–Ordovician strata.

The age of the Cambrian–Ordovician succession (Fig. 3) of the Stavelot-Venn Inlier remains partly poorly known. The graptolites of the ‘Dictyonema flabelliforme fauna’ indicated an earliest Ordovician age for parts of the sequence (Solwaster Member, Jalhay Formation; Wang & Servais Reference Wang and Servais2015), whereas deeper in the succession, the enigmatic ichnofossil Oldhamia indicated a possible middle Cambrian age. However, the latter had also been considered previously to be indicative of an earlier Cambrian age (see revision of Herbosch & Verniers Reference Herbosch and Verniers2011). More detailed biostratigraphical information was provided in the frame of a doctoral study by Vanguestaine (Reference Vanguestaine1973). He carefully analysed the acritarch assemblages of the different sedimentary units of the Stavelot-Venn Inlier in the late 1960s and early 1970s, and was able to confirm the Cambrian and Ordovician age of the sediments (e.g., Vanguestaine Reference Vanguestaine1967, Reference Vanguestaine1974, Reference Vanguestaine1978, Reference Vanguestaine1986, Reference Vanguestaine1992).

Since the 19th Century, the succession in the Ardenne Allochthon was historically separated into three ‘groups’: the Deville and Revin groups attributed to the Cambrian and the Salm Group attributed to the Ordovician (for a history of the former terminologies, see Verniers in Dejonghe et al. Reference Dejonghe, Herbosch, Steemans and Verniers2006), with the Rhabdinopora levels at the base of the Salm Group (Fig. 3). Following stratigraphical revisions (e.g., Verniers et al. Reference Verniers, Herbosch, Vanguestaine, Geukens, Delcambre, Pingot, Belanger, Hennebert, Debacker, Sintubin and De Vos2002), the Deville Group is currently subdivided into the Hourt (formerly ‘Devillien a’, Dva) and Bellevaux (formerly ‘Devillien b’, Dvb) formations, whereas the Revin Group is represented by the Wanne Formation (formerly ‘Revinien 1 and 2’, Rv1 and Rv2), the La Venne Formation (formerly ‘Revinien 3 and 4’, Rv3 and Rv4) and the La Gleize Formation (formerly ‘Revinien 5’, Rv5). The overlying Salm Group (Sm) was divided into three formations (‘Salmien 1–3’), which, in accordance with the international nomenclatural standards, were renamed Jalhay Formation (including three members, in ascending order: Solwaster, Spa and Lierneux), Ottré Formation (including three members, from base to top: Meuville, Les Plattes, Colanhan) and Bihain Formation (including two members, in ascending order: Ruisseau d’Oneux and Salmchâteau). Note that the Petites Tailles Formation, defined by Verniers et al. (Reference Verniers, Herbosch, Vanguestaine, Geukens, Delcambre, Pingot, Belanger, Hennebert, Debacker, Sintubin and De Vos2002) and overlying the Bihain Formation, is most probably late Pridoli to earliest Lochkovian in age (Denayer & Mottequin Reference Denayer and Mottequin2024); therefore, it does not belong to the Stavelot-Venn Inlier, but to its ‘Gedinnian’ cover that yielded Pridoli brachiopods (e.g., Boucot Reference Boucot1960; Mottequin Reference Mottequin2019; Mottequin & Jansen Reference Mottequin and Jansen2025) on its southeastern margin. It thus lies above and not below the lower Palaeozoic/Lower Devonian unconformity.

The intervals providing the trace fossil Oldhamia (Fig. 4a, b) are located in the middle part of the Bellevaux Formation (tentatively correlated with Cambrian Series 2). International correlation of acritarch assemblages, found higher than the Oldhamia occurrences, allowed to confirm the late early to early middle Cambrian age of the Bellevaux Formation (e.g., Vanguestaine Reference Vanguestaine1992), while the underlying Hourt Formation did not provide any macrofossils or acritarchs and remains thus of unknown age. The Wanne Formation is probably of middle Cambrian age, based on acritarchs, whereas the La Venne Formation most probably correlates with the middle and upper Cambrian (Vanguestaine Reference Vanguestaine1992). The La Gleize Formation bears acritarchs that are clearly of Furongian age, most probably corresponding to Cambrian Stage 10. The single macrofossil record in the Cambrian of the Stavelot-Venn Inlier is the presence of two minute, poorly preserved specimens identified by Vanguestaine & Rushton (Reference Vanguestaine and Rushton1979) as linguliformean brachiopods attributed to Acrothele cf. bergeroni (Fig. 4e).

The former Salm Group is clearly of Ordovician age, but only few intervals are precisely dated. The graptolite-bearing horizons (Rhabdinopora) are found in the lower part of the Jalhay Formation (Solwaster and Spa members) providing precise age attributions (Time-Slice 1a, lower Tremadocian). The uppermost part of this formation provides acritarchs in some levels of the Lierneux Member (Vanguestaine & Servais Reference Vanguestaine and Servais2002), which clearly correspond to the uppermost Tremadocian (Time-Slice 1d), based on international correlations (Molyneux et al. Reference Molyneux, Raevskaya and Servais2007). The overlying Ottré Formation was long considered to provide neither macrofossils nor acritarchs, and therefore remained of unknown age. The discovery of a poorly preserved conodont fauna in greywacke levels at the transition between the Meuville and the Les Plattes members is therefore of interest (Vanguestaine et al. Reference Vanguestaine, Breuer and Lehnert2004). Attributed to the Early Ordovician, and most probably to the latest Tremadocian to earliest Floian (Paroistodus proteus Biozone), these conodont findings may imply that at least the lower parts of the Ottré Formation are also Tremadocian (pre-Floian) age. More recently, Candela & Mottequin (Reference Candela and Mottequin2022) and Candela et al. (Reference Candela, Harper, Servais and Mottequinin press) revised the questionable reports of macrofossils of this unit (attributed to a multitude of different fossil groups, including brachiopods and phyllocarids, but also annelids, crinoids and even plant fossils) concluding that only a few specimens, associated with conodonts described by Vanguestaine et al. (Reference Vanguestaine, Breuer and Lehnert2004), can be attributed to the brachiopod genus Celdobolus, providing no biostratigraphical information (however see below).

Vanguestaine (Reference Vanguestaine1986) mentioned without illustrations or further descriptions the presence in the overlying Bihain Formation (in the upper part of the Salmchâteau Member, i.e., in the youngest sediments of the entire Stavelot-Venn Inlier) of an acritarch association including the genus Frankea, but also the presence of chitinozoans. Unfortunately, the assemblage was not illustrated and the data remain unpublished. However, if the presence of Frankea is confirmed, these levels would clearly belong to the Middle Ordovician, as this acritarch genus has its first appearance only in the Dapingian (Servais et al. Reference Servais, Molyneux, Li, Nowak, Rubinstein, Vecoli, Wang and Yan2018). Vanguestaine’s (Reference Vanguestaine1986) report is the reason why in all stratigraphical schemes published for the Stavelot-Venn Inlier, the youngest sediments are considered to be of Middle Ordovician age. New palynological studies on both acritarchs and chitinozoans are thus needed to confirm or reject this hypothesis. Between the lower parts of the Ottré Formation (uppermost Tremadocian to lowermost Floian) and the upper parts of the Bihain Formation (possibly Middle Ordovician, but this needs to be confirmed), the upper parts of the Ottré Formation (Les Plattes and Colanhan members) and the lower part of the Bihain Formation (Ruisseau d’Oneux Member) remain completely undated; it is possible that the succession is far from being complete, although most stratigraphical reviews suggest so (e.g., Verniers et al. Reference Verniers, Herbosch, Vanguestaine, Geukens, Delcambre, Pingot, Belanger, Hennebert, Debacker, Sintubin and De Vos2002, fig. 3; Herbosch et al. Reference Herbosch, Liégeois, Gärtner, Hofmann and Linnemann2020, fig. 3). It is important to remember that the age of most of the lithological units of the Stavelot-Venn Inlier remains totally unknown.

Although the stratigraphical column (Verniers et al. Reference Verniers, Herbosch, Vanguestaine, Geukens, Delcambre, Pingot, Belanger, Hennebert, Debacker, Sintubin and De Vos2002, fig. 3 and subsequent papers) suggests that the Stavelot-Venn Inlier displays a continuous Cambrian–Ordovician succession of formations, it becomes evident that this succession is mostly incomplete, with patches of sedimentation from the early–middle Cambrian to the Early Ordovician, and possibly the Middle Ordovician, with very sporadic fossil occurrences (Fig. 3). The sedimentology of this thick siliciclastic succession was partly studied by Lamens (Reference Lamens1985, Reference Lamens1986), Lamens & Geukens (Reference Lamens and Geukens1985) and von Hoegen et al. (Reference von Hoegen, Lemme, Zielinski and Walter1985). Most stratigraphical intervals remain of unknown age. The findings of all fossil records, such as that of trilobites or sponges, as mentioned in the literature, are thus potentially of the greatest significance.

2. Material and methods

Almost all the illustrated specimens studied herein are deposited at the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences (prefixed RBINS), Brussels. Most of the pseudofossils are part of the Constantin Malaise collections acquired by the RBINS in July 1902 (IG (= General Inventory) 6887) and April 1930 (IG 9340) (see Mottequin & Poty Reference Mottequin and Poty2025), but a few specimens belong to the collection of Eugène Coemans (IG 3242) acquired by the RBINS in the early 1870s (Kickx Reference Kickx1871). Additional specimens are deposited in the palaeontological collections of Liège University (prefixed PA.ULg).

The samples were photographed using a Nikon D850 digital camera, equipped with a Nikon AF 50 mm F1.8 lens or a Sigma 70 mm macro lens. Some of them were coated with ammonium chloride and photographed using an Olympus OM-D E-M10 Mark IV digital camera equipped with the Olympus M.Zuiko Digital ED 60 mm macro lens. Small brachiopods selected for scanning electron microscopy were imaged with an ESEM FEI Quanta 200, under low vacuum; specimens were uncoated.

3. Trilobite records from the Stavelot-Venn Inlier

Although trilobites have been reported and/or partly revised from other parts of the lower Palaeozoic of Belgium (e.g., Lespérance & Sheehan Reference Lespérance and Sheehan1987; Dean Reference Dean1991; Owens & Servais Reference Owens and Servais2007; Laibl et al. Reference Laibl, Servais and Mottequin2023; Candela et al. Reference Candela, Harper and Mottequin2025; Mottequin et al. Reference Mottequin, Genard and Poty2025), trilobites from the Stavelot-Venn Massif have never been described in detail. Some reports have been published in the literature, but these have never been reviewed. Some of the specimens appear today to be lost, but a few are still available.

To our knowledge the oldest account of trilobites in the Cambrian of the Stavelot-Venn Inlier is that of Davreux (Reference Davreux1833, pp. 232, 288), who reported the discovery of fragments of large trilobites by M. Maquinay in 1830 within the ‘ardoise de Solwaster’ (‘slate of Solwaster’, see also Dumont Reference Dumont1847, p. 37 and Gosselet & Malaise Reference Gosselet and Malaise1868, p. 112) in the Belgian part of this inlier (Fig. 2). Subterranean slate quarries were open in the past on the left bank of the Hoëgne River, between Solwaster and Sart-lez-Spa (Fig. 2); their entrances are still visible at the bottom of the hillside [coordinates of the northernmost one: 50°31′14.084″N, 5°57′14.950″E]. The quarried level (see Dumont Reference Dumont1847; Remacle Reference Remacle2007) was ascribed to the ‘Revinian Group’, i.e., the disused stratigraphical unit that represented the upper part of the Cambrian of the Ardenne Allochthon, according to d’Omalius d’Halloy (Reference d’Omalius d’Halloy1853, p. 487) and Dewalque (Reference Dewalque1868, p. 24, Reference Dewalque1880, p. 27). Today, these levels correspond to the La Gleize Formation, based on the new geological map of the area (Marion et al. Reference Marion, Geukens and Lambertyin press a), which can be attributed on the basis of acritarch biostratigraphy to the uppermost Cambrian, i.e., the upper part of the Furongian (e.g., Herbosch Reference Herbosch2021). Dewalque (Reference Dewalque1868, Reference Dewalque1880) indicated that Maquinay’s material was not traced in the palaeontological collections of Liège University, and thus in this report was not revised. Dewalque (Reference Dewalque1874a) reported a specimen identified as Agnostus from the ‘Revinian’ of the Ardennes (Stavelot Massif according to Gosselet Reference Gosselet1888, p. 124), but with no more details concerning its precise provenance. So far, the specimen has not been traced. It is thus not possible to revise the material and to provide evidence that the potential fossil is congeneric with Agnostus.

Malaise (Reference Malaise1866, Reference Malaise1881) announced the discovery of trilobite remains (thoraxes and pygidia) in an old quarry located to the NE of Spa in the Stavelot-Venn Inlier (Fig. 2). This quarry is still accessible [coordinates: 50°29′33.449″N, 5°52′12.187″E] and was opened to produce roofing slates and rubble stones; it exposes the Tremadocian Jalhay Formation, and more precisely the contact between the top of the Solwaster Member and the base of the Spa Member (Marion et al. Reference Marion, Geukens, Lamberty and Mottequinin press b). Dumont (Reference Dumont1847, pp. 37, 121) reported there traces that he thought belonged to plants, but which correspond to planktic graptolites (Malaise Reference Malaise1881), thus most probably from the Solwaster Member. Another disused quarry located nearby, to the east [coordinates: 50°29′33.601″N, 5° 52′20.150″E], displays the same succession and may have yielded pseudofossils. Malaise (Reference Malaise1866, Reference Malaise1881), Gosselet & Malaise (Reference Gosselet and Malaise1868) and Mourlon (Reference Mourlon and van Bemmel1873, Reference Mourlon1881) also reported, in the same lithostratigraphic unit, the presence of a trilobite pleura identified by Joachim Barrande as belonging to Paradoxides in an excavation located formerly at the intersection between the ‘old’ and the ‘new’ roads linking Spa to Sart-lez-Spa [approximate coordinates: 50°29′35.638″N, 5°52′21.788″E] (Fig. 2). Although the specimen from the latter locality has not been traced in the RBINS collections, the examination of the specimens from the Spa disused quarry and another unknown locality near Jalhay enables us to illustrate for the first time the so-called trilobites from the Jalhay Formation (Fig. 5a–d). Our investigation clearly indicates that it is obvious that the remains, identified as trilobites (Fig. 5a–c) or traces made by trilobites (Fig. 5d) according to Malaise’s handwritten labels preserved in RBINS collection, only vaguely resemble trilobite fossils, but a more precise identification and even a confident attribution to the trilobites are not possible. No fossil or ichnofossil can be identified based on these specimens that may actually only correspond to nonbiological traces produced by sedimentary processes and tectonics (Fig. 5).

Figure 5 Pseudofossils from the Cambrian and Ordovician succession of the Stavelot-Venn (a–g, j) and Rocroi (h–i) inliers. (a, b) RBINS a14170 (a) and a14171 (b) (IG 6887), formerly identified as pleurae of trilobites (Malaise in coll.); Spa (disused quarry), Jalhay Formation (Spa Member). (c) RBINS a14172 (IG 6887), formerly identified as pleurae of Paradoxides (Malaise in coll.); Jalhay (with no more information), Jalhay Formation. (d) RBINS a14173 (IG 6887), formerly identified as traces left by trilobites (Malaise in coll.); Spa (disused quarry?), Jalhay Formation (Spa Member). (e, f) RBINS a14174 (e) and a14175 (f) (IG 3242), nodules partly dissolved (e) and completed dissolved with remnants of quartzite venules; both were formerly identified as Caulerpites cactoides (in coll.); Lierneux (with no more information), Ottré Formation (Les Plattes Member). (g) RBINS a14176 (IG 6887), formerly identified as traces left by Lingulocaris lingulaecomes (Malaise in coll.); Lierneux (with no more information), Ottré Formation (Les Plattes Member). (h) RBINS a1186 (IG 9340), nodule previously identified as Actinodonta sp. by Barrois (in Malaise Reference Malaise1910c) and corresponding to the ‘type specimen’ of Modiolopsis? malaisii [sic] Fraipont Reference Fraipont1910; Fépin (Sainte-Marguerite slate mine), Rocher de l’Uf Formation. (i) RBINS a14177, concretion developed in slate, i.e., one of the two specimens discarded by Barrois (in Malaise Reference Malaise1910c); Fépin (France) (Sainte-Marguerite slate mine), Rocher de l’Uf Formation. (j) RBINS a14178 (IG 9340), claws probably handmade, formerly identified as spicules of Protospongia fenestrata; Ruy (La Gleize, Moulin du Ruy), La Gleize Formation. All scale bars represent 10 mm.

Another trilobite record was mentioned more recently by Vanguestaine et al. (Reference Vanguestaine, Breuer and Lehnert2004). Besides the conodonts belonging to the Paroistodus proteus Zone, Vanguestaine et al. (Reference Vanguestaine, Breuer and Lehnert2004) also illustrated other fossil fragments, including a ‘long hollow spine most probably of a trilobite’ (Vanguestaine et al. Reference Vanguestaine, Breuer and Lehnert2004, pl. 1, fig. 18) from the Early Ordovician of the basalmost part of the Les Plattes Member of the Ottré Formation. It is impossible to confirm or infirm this speculative identification of such a minute, poorly preserved specimen deposited in the palaeontological collections of Liège University, even if such hollow spines are known in Ordovician trilobites (e.g., Vannier et al. Reference Vannier, Vidal, Marchant, El Hariri, Kouraiss, Pittet, El Albani, Mazurier and Martin2019). More material is required to confirm this identification.

In conclusion, the revision of the literature and of the available fossil material in the public collections does not yet confirm the presence of trilobites in the Stavelot-Venn Inlier. Vanguestaine et al.’s (Reference Vanguestaine, Breuer and Lehnert2004) identification of a possible trilobite spine remains questionable.

4. Brachiopod and arthropod records from the Stavelot-Venn Inlier

Most of the brachiopods described from the lower Palaeozoic of Belgium have not been revised for several decades, with the exception of a few faunas from the Condroz Inlier (Lespérance & Sheehan Reference Lespérance and Sheehan1987; Sheehan Reference Sheehan1987). Nevertheless, our knowledge of these faunas is currently improving as a review of the different brachiopod faunas of the Ordovician is ongoing (Candela et al. Reference Candela, Marion, Servais, Wang, Wolvers and Mottequin2021, Reference Candela, Harper and Mottequin2025; Candela & Mottequin Reference Candela and Mottequin2022, Reference Candela and Mottequin2023). Similar to the trilobites, a number of authors published reports of brachiopods from the Cambrian and the Ordovician of the Stavelot-Venn Inlier, from both the Belgian and the German outcrop areas (e.g., Schmidt & Geukens Reference Schmidt and Geukens1959; Graulich Reference Graulich1963; Geukens in Bulman Reference Bulman1970). Candela et al. (Reference Candela, Marion, Servais, Wang, Wolvers and Mottequin2021) and Candela & Mottequin (Reference Candela and Mottequin2022) taxonomically documented the brachiopods from this inlier, mostly on the basis of the material collected by M. Vanguestaine and deposited at the University of Liège, and complemented by specimens housed at the RBINS and at the Geological Survey of Nordrhein-Westfalen (Germany). Unfortunately, the material collected by F. Geukens could not be traced in the collections at Leuven University.

The revised material confirms the presence of brachiopods at least in the Lower Ordovician of the Stavelot-Venn Inlier, from both the Jalhay (Solwaster Member) and Ottré (Les Plattes Member) formations (Fig. 3). The Solwaster Member of the Jalhay Formation provides linguliformeans that were identified as Lingulella lata (Fig. 4g), Lingulella? sp., Lithobolus, sp., Broeggeria sp. (Fig. 4f), Acrotreta? sp. and different undetermined species of Linguloidea. The only taxon recognised in the Les Plattes Member was Celdobolus sp. from the locality Bierleux in the Lienne River valley (Fig. 2).

Dewalque (Reference Dewalque1874a) reported the presence of fossil traces made by the phyllocarid Hymenocaris vermicauda in the Cambrian (‘Revinian’) of the Ardenne Allochthon. Van Straelen (Reference Van Straelen1933) excluded this species from the list of phyllocarids recognised in the Palaeozoic of Belgium due to the lack of descriptions and illustrations. Moreover, he noted that the specimen was not found in the collections of Liège University.

Candela et al. (Reference Candela, Harper, Servais and Mottequinin press) provide further insights into the alleged faunas of the Les Plattes Member and point out that the examination of the ancient (over a century ago) Belgian literature mentioned interpretations of various kinds of dubious structures ‘traces’, with specimens attributed to crinoids (Dumont Reference Dumont1847), plants (e.g., Caulerpites cactoides) (Dewalque Reference Dewalque1868; Crépin Reference Crépin and van Bemmel1873), annelids (Malaise Reference Malaise1876b, Reference Malaise1877), brachiopods (Malaise Reference Malaise1878b, Reference Malaise1878c) and phyllocarids (Lingulocaris lingulaecomes) (e.g., Malaise Reference Malaise1911). None of these determinations is justified (Fig. 5e–g) as it appears that they most probably have an abiotic origin. They seem to correspond to the traces left by the dissolution of nodules that may have coalesced, and which have been frequently affected by the presence of numerous quartz veins (Fig. 5e, f). Lohest (Reference Lohest1899) pointed out the resemblance of some of these nodules with brachiopods. So far, only brachiopods (Celdobolus sp.) are recovered from the greywacke beds of the basalmost part of the Les Plattes Member of the Ottré Formation (see above).

Another interesting discovery was made by M. Vanguestaine, who collected two brachiopod specimens which were published by Vanguestaine & Rushton (Reference Vanguestaine and Rushton1979). These authors attributed the two specimens to Acrothele cf. bergeroni. These specimens, housed in the palaeontological collections of Liège University, are from the Wanne Formation of the Trois-Ponts locality (middle–upper Cambrian) (Figs 2, 3). One of them has been reillustrated by Candela et al. (Reference Candela, Marion, Servais, Wang, Wolvers and Mottequin2021, fig. 3), who confirmed the identification, and this specimen is figured here for completeness (Fig. 4e). So far, these are the oldest brachiopods recognised in Belgium.

There are thus a few confirmed brachiopod occurrences in the Stavelot-Venn Inlier, with an exceptional occurrence of two poorly preserved acrotretide specimens in the Cambrian, and a moderately diverse assemblage in the Lower Ordovician of both the Belgian and German parts of the inlier (Candela et al. Reference Candela, Marion, Servais, Wang, Wolvers and Mottequin2021; Candela & Mottequin Reference Candela and Mottequin2022).

5. Questionable bivalve remains from the Rocroi Inlier

Another dubious occurrence of an alleged bivalve from the Cambrian of the Ardenne Allochthon was reported by Malaise (Reference Malaise1910c). Three specimens were submitted to Charles Barrois for identification, who considered one of them as a representative of the genus Actinodonta (Fig. 5h) whereas the other two were discarded (Fig. 5i). Malaise (Reference Malaise1910c) claimed that it was the oldest bivalve in Belgium but also in the world. Although from the Rocroi Inlier (Fig. 1), and thus not from the Stavelot-Venn Inlier, this discovery of ‘bivalves’ is interesting in the frame of the critical revision of questionable fossil occurrences from the Ardenne inliers.

Fraipont (Reference Fraipont1910) was in charge of the description of the specimen collected by Malaise (Reference Malaise1910c). Astonishingly, he erected a new large-sized bivalve species based on the specimen identified as Actinodonta sp. by Barrois (in Malaise Reference Malaise1910c), namely Modiolopsis? malaisii [sic] (Fig. 5h) from the ‘middle’ Cambrian of ‘Belgium’. Malaise (Reference Malaise1910c) noted that three specimens were found in the slate mine of Sainte-Marguerite in the ‘Revinian’ (Rocher de l’Uf Formation (‘b3a’ in Beugnies & Waterlot Reference Beugnies and Waterlot1965); see Verniers et al. Reference Verniers, Herbosch, Vanguestaine, Geukens, Delcambre, Pingot, Belanger, Hennebert, Debacker, Sintubin and De Vos2002 and Herbosch Reference Herbosch2021), i.e., in the middle–upper Cambrian of the Rocroi Inlier; see Beugnies & Waterlot (Reference Beugnies and Waterlot1965). This slate mine was located between Haybes and Fépin, in the Meuse River valley, and thus in the French part of the Rocroi Inlier, and not in Belgium, as wrongly noted by Fraipont (Reference Fraipont1910) and Babin (Reference Babin1994). Lohest (Reference Lohest1910), in his report on Malaise’s (Reference Malaise1910c) discovery, expressed serious doubts about the attribution of these specimens. This ambiguous record has since fallen into oblivion, and rightly so, but Babin (Reference Babin1993) stressed the problematic attribution of the specimens to the bivalves from the Rocroi Inlier.

Finally, in the frame of a reinvestigation of the palaeogeographical distribution of lower Palaeozoic bivalves, Babin (Reference Babin1994) restudied the three specimens and identified two of them as simple ‘concretions’ (Fig. 5i) and the third one, which he reillustrated by a photograph, as a ‘pseudofossil’. The specimen actually only represents a nodule with a strange shape and some striations that make it look vaguely like a bivalve fossil (Fig. 5h).

There are thus so far no true bivalve records in the lower Palaeozoic of the Ardenne inliers, but bivalves are known from the Ordovician of the Brabant Massif (Malaise Reference Malaise1873) and the Condroz Inlier (Maillieux Reference Maillieux1939). However, their revision is long overdue.

6. Other questionable fossil occurrences from the Stavelot-Venn Inlier

The Belgian literature includes reports of alleged sponge remains, which were identified by Dewalque (Reference Dewalque1874a) and Malaise (Reference Malaise1909, Reference Malaise1910a, Reference Malaise, Mourlon and Malaise1910b) as Protospongia fenestrata, from the middle–upper Cambrian (formerly ‘Revinian’) siliciclastic succession of the Stavelot-Venn Inlier, but also of the Brabant Massif. Although Maillieux (Reference Maillieux1922, Reference Maillieux1933) rightly expressed some doubts about the identification made by these authors, this species was still cited in the subsequent literature (e.g., Graulich Reference Graulich and Fourmarier1954) without investigation of the alleged fossils. The material present in the collection of the RBINS indicates ‘Protospongia fenestrata’ specimens from the Malaise collections (IG 6887 and 9340). The collection bearing the IG 9340 exhibits one specimen from the ‘Revinian’ (thus probably Cambrian), whereas the IG 6687 collection displays one sample from the ‘Salmian’ (thus probably Ordovician) of the locality of Ruy (La Gleize; Moulin du Ruy), although all samples show the same sedimentary facies. Close examination of the limited material available at the RBINS (Fig. 5j) demonstrates that these traces consist of scratches, probably handmade for some of them! There is thus so far no evidence of sponge remains in the Stavelot-Venn Inlier and the previous identifications should be considered as fictitious.

Dewalque (Reference Dewalque1874b) reported but did not illustrate Eophyton linneanum from the Revinian of Stavelot, without more information. The RBINS collection (IG 6887) includes two slabs (Fig. 6a, b) from Jalhay recovered from the ‘quartzophyllades’ of the La Gleize Formation and identified as such by Malaise. They bear furrows (sensu Savazzi Reference Savazzi2015) developed on upper surfaces of bedding planes (hyporelief) that might be superficially similar to Eophyton; its origin (tool mark or ichnofossil) is a matter of controversy (e.g., Jensen Reference Jensen1997; Savazzi Reference Savazzi2015). However, additional material from the Stavelot-Venn Inlier is required to reach a better interpretation of these structures which could be linked to sedimentary processes.

Figure 6 (a, b) Furrows identified as Eophyton linneanum by Malaise (in coll.), RBINS a14190 (a) and a14191 (b) (both IG 6887); Jalhay, La Gleize Formation. (c) Possible sedimentary load structures (arrows) identified as Arenicolites didymus by Malaise (in coll.), RBINS a14192 (IG 6887); Grand-Halleux, Bellevaux Formation. (d) Probable bioturbation identified as Scolithus (recte: Skolithos) by Maillieux (in coll.), RBINS a14193; Hockai, La Gleize Formation. (e) Probable burrows identified as Scolithus (recte: Skolithos) by Malaise (in coll.), RBINS a14194 (IG 6887); Hockai, La Gleize Formation. Scale bars represent 10 mm.

Malaise (Reference Malaise1877) mentioned the presence of tubes or burrows (‘perforations’) made by annelids (Arenicolites or Scolithus (recte: Skolithos)) in the Cambrian–Tremadocian of the Stavelot-Venn Inlier. He thought he had recognised Arenicolites didymus from the Cambrian (Bellevaux Formation) of Grand-Halleux. Two slabs from this locality, bearing minute positive pustules arranged on the upper surface of a bedding plane, have been recovered from the RBINS collection (IG 6887) and are accompanied by a label handwritten by Malaise with this identification. They are markedly different from Salter’s (Reference Salter1856) original material (see discussion in Callow et al. Reference Callow, McIlroy and Brasier2011) as they are not developed in pairs and could be simply sedimentary load structures (Fig. 6c). The RBINS collection includes two slabs of ‘Revinian’ black slate of the La Gleize Formation from the locality of Hockai, which displays probable bioturbations. They were tentatively identified as Scolithus (sic) by Maillieux (in coll., label dated of 1930) (Fig. 6d) and Malaise (in coll.) (Fig. 6e).

Other questionable records in particular include those in the early years of the description of the lower Palaeozoic faunas of Belgium and surrounding areas (Germany for the Stavelot-Venn inlier, France for the Rocroi inlier) (e.g., Malaise Reference Malaise1912). Some of these are listed in Candela & Mottequin (Reference Candela and Mottequin2022) and Candela et al. (Reference Candela, Harper, Servais and Mottequinin press). Some specimens were even described as plant remains (Crépin Reference Crépin and van Bemmel1873; Mourlon Reference Mourlon1880, Reference Mourlon1881; see discussion in Candela et al. Reference Candela, Harper, Servais and Mottequinin press). On the other hand, Forir (Reference Forir1897), for example, reported the hyolith Theca cf. arata from the ‘Salmian’ of the left bank of Lake Gileppe (Stavelot-Venn Inlier) (Fig. 1). According to Forir (Reference Forir1897), it comes from an outcrop where Dewalque (Reference Dewalque1881) reported the presence of graptolites (Rhabdinopora) and located near the contact with the Lochkovian conglomerate, thus within the Solwaster Member of the Jalhay Formation (Laloux et al. Reference Laloux, Dejonghe, Geukens, Ghysel and Hance1996). This discovery, if verified, would be the first find of a hyolith specimen in the Belgian Tremadocian. However, like many other fossil and ichnofossil records, this record is questionable due to the lack of illustrations, as is the case of the fragments of possible orthoconic cephalopods and Chondrites antiquus var. minor reported from the Tremadocian of Spa by Malaise (Reference Malaise1866) and Gosselet & Malaise (Reference Gosselet and Malaise1868), respectively, and of Nereites discovered by M. Lohest in the Tremadocian of Salmchâteau which was reported by Malaise (Reference Malaise1912); the last report could perhaps correspond to the ‘traces de vers’ cited by Lohest & Forir (Reference Lohest and Forir1905, p. B131). Note that Lohest & Forir (Reference Lohest and Forir1900, p. 381) mentioned the presence of Nereites cambriensis? and Primitia sp. based on Dewalque and Malaise’s research in the ‘Devillian’ of the Stavelot-Venn Inlier, at least according to these authors. Nevertheless, to our knowledge, the first report only concerns discoveries made in the Rocroi Inlier (Dewalque Reference Dewalque1877) whereas Primitia sp. is from the ‘Devillian’ of the Ardenne with no more geographical indication (Dewalque Reference Dewalque1874a). Unfortunately, these specimens cannot be currently located in public collections and are thus possibly lost.

7. Some considerations on the rarity of Cambrian–Ordovician faunas of the Stavelot-Venn Inlier

A striking characteristic of the Cambrian–Ordovician succession of the Stavelot-Venn Inlier is the extreme rarity of fossils that cannot be explained only by the metamorphism inherited from the Caledonian and Variscan orogenies (see references in Herbosch et al. Reference Herbosch, Liégeois, Gärtner, Hofmann and Linnemann2020), which is more developed in its southeastern part (low-grade – epizone – metamorphism). Malaise (Reference Malaise1910a) suggested that the development of the cleavage was responsible for the disappearance of fossils. Besides the ichnofossils reported from the Cambrian (Oldhamia) and those that remain to be studied in the Ordovician, the very restricted fauna strongly suggests a basin suffering from poor oxygenation conditions (anoxia-dysoxia), and this for very long periods, in comparison with contemporaneous basins developed around Belgium, where faunas are much more diverse. The presence of planktic graptolites (e.g., Erdtmann Reference Erdtmann1986; Wang & Servais Reference Wang and Servais2015) and that of the minute and possibly epiplanktic linguliformean brachiopods (see discussion in Candela et al. Reference Candela, Harper, Servais and Mottequinin press), which were recovered from the graptolitic horizons, may suggest temporary dysoxic episodes in the upper part of the water column. Moreover, the absence of pelagic faunas such as trilobites and orthoconic cephalopods clearly reflects unfavourable environmental conditions.

8. Conclusion

The revision of the macrofossil record of the Stavelot-Venn Inlier indicates that only few reports and occurrences in the literature, which have mostly been recorded about a century ago, can be confirmed. As the largest of the four inliers of the Ardenne Allochthon in southern Belgium, the succession of the Stavelot-Venn Inlier is considered as the standard sedimentary sequence of the lower Palaeozoic of the Ardenne. However, the mostly siliciclastic rocks remain largely undated, with only few levels providing age-diagnostic fossils, although the rocks have been traditionally assigned to the lower Cambrian to Middle Ordovician, often represented in a continuous succession of formations.

Macrofossils are extremely rare, and all occurrences mentioned in the literature are revised in the present paper. The microfossil records, mostly acritarchs, which have mostly been published almost half a century ago, also need a careful revision, in particular in the Cambrian part of the succession, but this is out of the scope of the present review.

Only the trace fossils of the genus Oldhamia indicate a lower/middle Cambrian age for the lower (but not lowest) part of the succession, whereas the recently revised graptolites of the Rhabdinopora fauna clearly point out the presence of the Tremadocian (Early Ordovician).

Trilobites, sponges, phyllocarids and other fossil groups have been mentioned in the literature, which generally dates back from the late 19th and the early 20th Centuries (e.g., Lohest & Forir Reference Lohest and Forir1900), and were subsequently reported without examining the original material (e.g., Graulich Reference Graulich and Fourmarier1954; Waterlot Reference Waterlot and Rodgers1956; Mortelmans Reference Mortelmans1970). None of these findings can be confirmed. For many of the old records the fossils are lost or cannot be traced in public collections. From all macrofossils mentioned in literature, only a few brachiopod levels can be confirmed in the (? middle–upper) Cambrian and in the Lower Ordovician.

Last but not least, ichnofossils from the Belgian Caledonian inliers deserve detailed study in the future in order to better document the Cambrian–Ordovician palaeoenvironments.

9. Acknowledgements

We are grateful to A. Folie and J. Lalanne (RBINS) for curatorial support, and V. Fischer (ULiège) for access to the collections under his care. We thank Thierry Hubin (RBINS) for part of the photographic work. This is a contribution to IGCP project 735 ‘Rocks and the Rise of Ordovician Life: Filling knowledge gaps in the Early Palaeozoic Biodiversification’. LL was supported by the institutional support RVO 67985831 of the Institute of Geology of the Czech Academy of Sciences. This paper benefitted from the thorough reviews of B. Lefebvre (CNRS, Lyon 1 University, France) and E. Poty (ULiège, Belgium), and the careful editing of David Harper.

10. Competing interests

The authors declare none.