Introduction

In recent years, affective polarization has become an increasingly ‘hot topic’ in public and academic debate, spurring widespread worries about its alleged detrimental impact on citizens’ democratic attitudes. Affective polarization is defined as citizens’ tendency to positively evaluate their preferred party and its supporters (i.e., in‐party favorability), whilst holding negative sentiments towards the political opponent (i.e., out‐party animosity) (Gidron et al., Reference Gidron, Adams and Horne2020; Iyengar et al., Reference Iyengar, Sood and Lelkes2012).Footnote 1 Dystopian accounts of the political consequences of affective polarization are widespread in the academic literature (see Broockman et al., Reference Broockman, Kalla and Westwood2023). Scholars have gone as far as to state that affective polarization could cause ‘a deterioration in the quality of democracy’ (McCoy & Somer, Reference McCoy and Somer2019, p. 258) or even the collapse of entire political systems (McCoy et al., Reference McCoy, Rahman and Somer2018). On the individual‐level, affective polarization is argued to fuel a range of undemocratic attitudes, including the rejection of unfavourable election results and the support for leaders with authoritarian tendencies (Janssen, Reference Janssen2024; Kingzette et al., Reference Kingzette, Druckman, Klar, Krupnikov, Levendusky and Ryan2021; Orhan, Reference Orhan2022; Ward & Tavits, Reference Ward and Tavits2019). Though speculation is rife, empirical evidence on the relationship between affective polarization and democratic support has yielded mixed results.Footnote 2 Whereas some studies report evidence that affective polarization erodes citizens’ support for democratic principles (e.g., Graham & Svolik, Reference Graham and Svolik2020; Harteveld et al., Reference Harteveld, Berntzen, Kokkonen, Kelsall, Linde and Dahlberg2023; Kingzette et al., Reference Kingzette, Druckman, Klar, Krupnikov, Levendusky and Ryan2021), others report null‐findings (e.g., Broockman et al., Reference Broockman, Kalla and Westwood2023; Voelkel et al., Reference Voelkel, Chu, Stagnaro, Mernyk, Redekopp, Pink, Druckman, Rand and Willer2023).

While these mixed findings could be driven by several relevant differences in countries, methods and measurements across these studies, we suggest that an additional contributing factor is that the relationship between affective polarization and democratic support follows a negatively curvilinear pattern (i.e., an inverted U‐shape), rather than the linear pattern that has implicitly been assumed in previous estimation strategies. In other words, we argue for the possibility that moderate levels of affective polarization can be beneficial for citizens’ democratic support as compared to a complete lack of polarization, but that there is a tipping point at which excessively high levels of affective polarization start to have an eroding impact. Recent work by Torcal and Magalhães (Reference Torcal and Magalhães2022) provides evidence that the relationship between perceived ideological polarization and democratic support indeed follows such a negatively curvilinear trend. In this research note, we build on their work and provide theoretical arguments for why the same dynamics apply to the concept of affective polarization.

Our assertion thus is that low affective polarization – though often considered normatively desirable – can erode citizens’ democratic support. When affective polarization is brought to a minimum, citizens do not feel positively or negatively towards any particular political party. We argue that without a sense of attachment or opposition to parties, citizens are likely to feel indifferent towards democracy. On the one hand, this is driven by a lack of party identification amongst the non‐polarized (Dias & Lelkes, Reference Dias and Lelkes2022; Orr et al., Reference Orr, Fowler and Huber2023), which is essential to make citizens feel represented by their democratic system and to spur broader democratic engagement (Efthymiou, Reference Efthymiou2018; Ypi, Reference Ypi2016). When citizens are unable to find ‘their crowd’ amongst the electoral options, this can drive a belief that the system is not responsive to their needs and should therefore not be supported particularly strongly. Indeed, prior evidence has shown that feeling connected to a party prevents political alienation, which refers to citizens’ estrangement from and rejection of the prevailing political system (Dassonneville & Hooghe, Reference Dassonneville and Hooghe2018). On the other hand, a certain degree of out‐party dislike in combination with party identification is crucial to foster a healthy level of political competition. In the absence of affective polarization, one is unlikely to attribute much importance to politics, electoral competition, or the democratic institutions that make such competition possible. In other words, ‘what is at stake in democratic elections from the citizens’ points of view cannot be so low as to render them – and democracy itself – irrelevant’ (Torcal & Magalhães, Reference Torcal and Magalhães2022). A certain degree of in‐party attachments and out‐party dislike are thus essential to raise the stakes of politics, spur citizens’ democratic involvement, and, importantly, make people feel represented (English et al., Reference English, Pearson and Strolovitch2019; Mason, Reference Mason2018; Ward & Tavits, Reference Ward and Tavits2019). Consistent with this argument, affective polarization has been shown to stimulate turnout and political participation (Harteveld & Wagner, Reference Harteveld and Wagner2023; Huddy et al., Reference Huddy, Mason and Aarǿe2015). Therefore, when kept within bounds, affective polarization can be a strengthening force for citizens’ democratic attitudes.

However, there is another side of the coin, as exemplified by the surge of worries and concerns about the alleged rising levels of affective polarization. When affective polarization takes on extreme forms, mutual tolerance erodes and voters come to view the political opponent as an existential threat to their way of life: ‘A normal political adversary with whom to engage in a competition for power transforms into an enemy to be vanquished’ (McCoy et al., Reference McCoy, Rahman and Somer2018, p. 19). In the face of this enemy, key democratic principles and processes become hard to uphold: Cooperation, compromise, and electoral defeat cease to be acceptable parts of politics (Janssen, Reference Janssen2024; Levitsky & Ziblatt, Reference Levitsky and Ziblatt2018). As a result, democracy may no longer be perceived as a desirable form of governance but, instead, as an obstacle that stands in the way of the in‐party's ability to exert political influence (Gidengil et al., Reference Gidengil, Stolle and Bergeron‐Boutin2022). Extreme affective polarization thus shifts citizens’ political priorities, compelling them to become ‘partisans first and democrats second’ (Graham & Svolik, Reference Graham and Svolik2020, p. 393). Likewise, scholars have theorized that affective polarization drives citizens to view the political world through a lens of emotion and contention (Armaly & Enders, Reference Armaly and Enders2022). Democracy becomes an intense battlefield over political power and a potential threat to the status of one's preferred party. This negative ‘perceptual screen’ can downstream the evaluations of democratic institutions, even of those that are generally considered apolitical (Armaly & Enders, Reference Armaly and Enders2022). As such, when taken to its extremes, affective polarization also has the potential to be an eroding force for citizens’ democratic support.

In sum, we hypothesize: The relationship between party affective polarization and democratic support follows a negatively curvilinear pattern.

We test the presence of such a curvilinear relationship using cross‐national survey‐data from three Western democracies (i.e., Germany, the United Kingdom, and the United States). Our findings reveal a clear negatively curvilinear pattern, indicating that citizens’ democratic support is indeed maximized at moderate levels of affective polarization. Substantively, these results suggest that there might be a ‘sweet spot’ at which there is enough affective polarization to foster democratic engagement, but not so much that it erodes democratic values. In doing so, this study provides a crucial methodological contribution by highlighting the importance of considering non‐linear estimation strategies when examining the relationship between affective polarization and democratic attitudes. Moreover, the results offer new insights into the normative evaluation of affective polarization, highlighting that a certain level of polarization could be beneficial in sustaining citizens’ democratic commitments.

Data & method

Data & cases

To test our hypothesis, we build on the estimation strategy of Torcal and Magalhães (Reference Torcal and Magalhães2022) and leverage data from three nationally representative surveys from the Comparative National Election Project (CNEP) collected in Germany (2017, N = 2,984), the UK (2017, N = 1,912), and the US (2016, N = 1,587).Footnote 3, Footnote 4 Although the CNEP includes data from more Western democracies, we selected these countries based on the availability of the specific combination of measures required for our analysis (i.e., democratic support and like/dislike scores of parties).Footnote 5

By leveraging this cross‐national dataset, our study contributes to the understanding of the impact of affective polarization on democratic attitudes beyond the US (see also Berntzen et al., Reference Berntzen, Kelsall and Harteveld2024; Harteveld et al., Reference Harteveld, Berntzen, Kokkonen, Kelsall, Linde and Dahlberg2023). As stated in a recent literature review on affective polarization in Europe: ‘the research on the link between affective polarization and democratic stability is still in its infancy’ (Wagner, Reference Wagner2024, p. 7). Insights into this relationship are ‘crucial to know if the oft‐expressed worries about polarization harming democracies are warranted’ (Berntzen et al., Reference Berntzen, Kelsall and Harteveld2024, p. 945). As such, by examining Germany and the UK alongside the US, we allow for a broader test of the dynamics between affective polarization and democratic support. Though all three countries can be considered WEIRD countries, (i.e., Western, educated, industrialized, rich and democratic), various crucial cross‐national differences ensure relevant variation in the data.

Previous comparative work shows relatively similar scores on party affective polarization for these three countries (Reiljan, Reference Reiljan2020; Wagner, Reference Wagner2021) but a more pronounced increase in the US over time, whilst affective polarization levels seem to be declining in Germany and relatively stable, or slightly declining in the UK (Boxell et al., Reference Boxell, Gentzkow and Shapiro2024; Reiljan, Reference Reiljan2020). For all three countries, we document average affective polarization scores between 2 and 3, with the UK being most affectively polarized (M = 2.618, SD = 1.310) and Germany (M = 2.344, SD = 0.910) and the US (M = 2.300, SD = 1.663) both scoring approximately 0.3 points lower (see online Supporting Information B). This resonates with Reiljan (Reference Reiljan2020), who reports higher average polarization in the UK than in the other two countries, but who also shows that the scores of the countries lie very close together (between 4 and 4.4 on a 0–10 scale), a notion that is corroborated by Wagner (Reference Wagner2021).

While the average affective polarization levels across our cases are relatively comparable, there are relevant conceptual differences in how affective polarization manifests in two‐party versus multi‐party systems (Bantel, Reference Bantel2023; Wagner, Reference Wagner2024). In the two‐party system of the US, the vast majority of voters identify with a single party (Iyengar et al., Reference Iyengar, Lelkes, Levendusky, Malhotra and Westwood2019). Consequently, affective polarization can relatively easily be captured as the difference in citizens’ affect‐evaluations of the Republican and Democratic Parties (Reiljan, Reference Reiljan2020; Wagner, Reference Wagner2021). Germany, in contrast, is a multi‐party system where citizens can feel positively or negatively towards multiple parties simultaneously (Röllicke, Reference Röllicke2023). Scholars have argued that affective polarization in these contexts is better captured through camp‐based (i.e., left/right and centre/radical) rather than party‐based divides (Bantel, Reference Bantel2023). The UK falls somewhere in between Germany and the US: whilst often considered a de facto two‐party system, more than two parties take seat in the House of Commons, and smaller parties like Reform UK (formerly UKIP) have successfully left their mark in Britain's political sphere.

These relevant cross‐national variations allow us to test whether curvilinear patterns hold across substantively different contexts, thereby enhancing the generalizability of our results. Despite this variability, we expect negatively curvilinear patterns in all three countries based on the theoretical argument outlined in the introduction. Although cross‐national differences likely play a relevant role in the shape of the relationship between affective polarization and democratic support, the limited number of upper‐level cases (i.e., three) prevents us from formulating hypotheses about the impact of country‐level characteristics.

Measures

Dependent variable

To measure respondents’ support for democracy, we rely on the same four survey items as employed by Torcal and Magalhães (Reference Torcal and Magalhães2022) (see online Supporting Information A). First, we use an ‘overt support’ item that taps into respondents’ agreement with representative democracy as the preferable form of governance. Moreover, we rely on three items that measure respondents’ support for other and more autocratic ways of governing (i.e., ‘The army should govern the country’, ‘Only one political party should be allowed to stand for election and hold office’, and ‘Elections and the National Assembly should be abolished so that we can have a strong leader running this country’). The results of a principal component factor analysis indicate that these items measure one latent construct (see Supporting Information D) and can therefore be combined into one variable indicating respondents’ level of democratic support.

Independent variable

Based on respondents’ like‐dislike scores of the political parties (0–10 scale), their party affective polarization levels were calculated using the commonly employed spread‐measure from Wagner (Reference Wagner2021). Previous studies on the relationship between affective polarization and democratic support have relied on either horizontal measures highlighting respondents’ warm or cold feelings towards other partisans (e.g., Broockman et al., Reference Broockman, Kalla and Westwood2023; Voelkel et al., Reference Voelkel, Chu, Stagnaro, Mernyk, Redekopp, Pink, Druckman, Rand and Willer2023), or vertical measures focusing on parties (e.g., Kingzette et al., Reference Kingzette, Druckman, Klar, Krupnikov, Levendusky and Ryan2021; Orhan, Reference Orhan2022). Especially in cross‐national research, the reliance on vertical like/dislike items is common due to their widespread availability (Wagner, Reference Wagner2021). Given the focus on party affective polarization in our theoretical framework, we deem a vertical approach appropriate. Nonetheless, since recent work highlights the importance of scrutinizing the employed measures of affective polarization (Areal & Harteveld Reference Areal and Harteveld2024; Druckman & Levendusky, Reference Druckman and Levendusky2019), we also show that our results remain robust across a horizontal measure in Supplementary Materials M.

Our models control for extremism, respondents’ left‐right placement, economic satisfaction, political interest, education level, gender, and age. Supporting Information A, B and C provide further information on descriptive statistics, question‐wording and correlations.

Analysis

To test whether the relationship between party affective polarization and democratic support is negatively curvilinear, we employ generalized additive models (GAMs). GAMs capture the effects of the independent variable through smooth nonparametric functions (i.e., splines) that can be nonlinear or linear, depending on the underlying pattern in the observations (Hastie & Tibshirani, Reference Hastie and Tibshirani1986). GAMs thus relax the assumption of linearity and offer a more flexible approach to capture nonlinear patterns that conventional linear models would overlook (Beck & Jackman, Reference Beck and Jackman1998). As such, the smooth relationships that are estimated with GAMs can take on a wide variety of shapes that are fully determined by the data (Wood, Reference Wood2017). We fit the GAMs for each country separately with the residual maximum likelihood method and include smooth functions for party affective polarization and extremism in the models.

Results

Generalized additive models

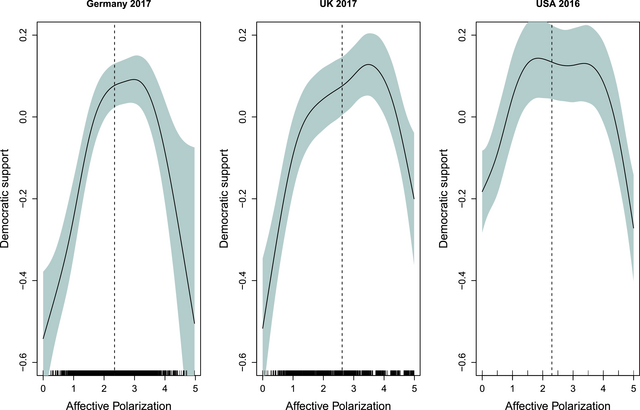

The results of the GAMs are visualized in Figure 1, which illustrates the shape of the relationship between party affective polarization and democratic support (see Supporting Information E for the corresponding table). In line with our hypothesis, we see that the relationship between party affective polarization and democratic support in Germany forms an inverted U‐shape. The figure shows that there is a tipping point at which the effect of party affective polarization on democratic support changes direction and turns negative. More concretely, the figure reveals that a certain degree of party affective polarization is associated with higher levels of democratic support as compared to the complete absence of polarization, which is illustrated by the initial ascending line in the figure. The curve reaches a peak at approximately the value of 2.5 on the party affective polarization scale, after which democratic support declines as party affective polarization further increases.

Figure 1. The shape of the relationship between party affective polarization and democratic support based on GAMs (95 per cent confidence intervals, dashed vertical line indicates country sample's average level of party affective polarization).

A very similar trend is observed in the UK (2017), where the relationship between affective polarization and democratic support also follows a negatively curvilinear trend. This again indicates that the democratic support of respondents is maximized when their level of polarization is neither very low nor very high. Yet, it should be noted that the tipping point in the UK is situated at a slightly higher level of party affective polarization (i.e., approximately 4) as compared to Germany. Nonetheless, similar to Germany, this tipping point surpasses the country's average level of affective polarization (indicated by the dashed vertical line), meaning that the country's mean polarization is not associated with a downward trend in citizens’ democratic support.

The US also portrays a negatively curvilinear pattern but with a flatter top of the curve. In accordance with Germany and the UK, we document an initial increase in citizens’ democratic support as party affective polarization increases, followed by a steep decrease when polarization takes on extreme forms. Citizens’ associated level of democratic support, however, is rather uniform between the values of 1.5 and 3.5 on the affective polarization scale, meaning that there is a less clear ‘peak’ of the curve. As such, in the US, citizens’ democratic support is maximized when party affective polarization falls within this range.

Overall, these results indicate that, while a certain degree of party affective polarization can be beneficial for citizens’ democratic support, there exists a point after which further increases are associated with lower democratic support. These findings support our hypothesis that the relationship between party affective polarization and democratic support follows a negatively curvilinear rather than a linear pattern. Notably, we find very similar effect sizes across all three countries.

Quadratic regressions

We test the robustness of our findings with a more conventional analytical approach: OLS regressions with quadratic transformations of party affective polarization (see Supporting Information F). First, we ran a regression model in which affective polarization is solely included as a linear term in order to illustrate how these findings deviate from models that do acknowledge patterns of non‐linearity. These results suggest that there is indeed no significant linear relationship between party affective polarization and democratic support in the US. In Germany and the UK, however, we document a modestly positive and statistically significant effect: higher levels of party affective polarization are associated with higher levels of democratic support (b = 0.087 in Germany and b = 0.075 in the UK).

Next, we include a quadratic term for party affective polarization in the models. A Likelihood Ratio test indicates that the fit of the models in all countries significantly improves when this quadratic term is added. Additionally, the effect of party affective polarization on democratic support now turns highly statistically significant and substantively increases in effect size in all countries. This already indicates that the linear models overlooked a relationship between affective polarization and democratic support that does exist in the data, particularly in the US.

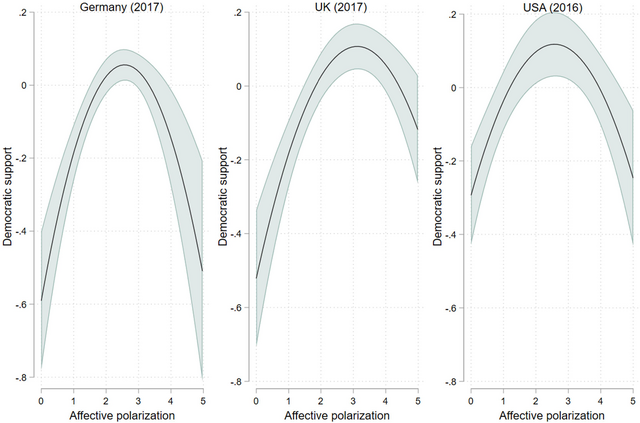

The results of the quadratic regressions are visualized in Figure 2. The figure shows fundamentally similar findings as the GAMs: we observe a negatively curvilinear trend across all cases.

Figure 2. Predicted values of democratic support for varying levels of party affective polarization (95 per cent confidence intervals)

Robustness checks

Since Torcal and Magalhães (Reference Torcal and Magalhães2022) have established that the relationship between perceived ideological polarization and democratic support also forms an inverted U‐shape, we ran an additional analysis in which we include a smooth function for perceived ideological polarization in the GAMs (Supporting Information I). The results indicate that the relationship between party affective polarization and democratic support remains negatively curvilinear when perceived ideological polarization is controlled for, though the effect sizes decrease slightly. Moreover, in the US, the initial ascending line in the figure becomes less pronounced, suggesting that the initial increase in democratic support is partially driven by perceived ideological polarization in this country.

To further ensure the robustness of our findings, we also re‐estimate the original models (1) excluding respondents who score zero on the affective polarization scale,Footnote 6 (2) using the mean‐distance measure of affective polarization following Wagner (Reference Wagner2021), and (3) controlling for internal and external efficacy (see Supporting Information H, J and K). These supplementary analyses lead to fundamentally similar findings, again underlining the existence of a negatively curvilinear pattern. In addition, Supporting Information L provides an overview of the descriptive statistics for different affective polarization levels, indicating that citizens’ average democratic support, democratic satisfaction, and external political efficacy are highest when they are situated in the middle category of affective polarization.

Additional analysis

To test whether these non‐linear dynamics hold across different measurements of affective polarization and democratic support, we also ran GAMs on the publicly available data from an experimental study by Voelkel and colleagues (Reference Voelkel, Chu, Stagnaro, Mernyk, Redekopp, Pink, Druckman, Rand and Willer2023). In their seminal work, the authors test various interventions that reduce affective polarization across three different data‐collections and examine the extent to which these successfully enhance democratic commitments. The authors do not document significant treatment effects, driving their conclusion that reducing affective polarization is not an effective strategy to strengthen pro‐democratic attitudes amongst the American citizenry.

Independent variable

Within this study, affective polarization is measured with a feeling‐thermometer on which respondents indicate how cold they feel towards out‐partisans. This 101‐point scale is reverse‐coded, so that higher values indicate colder feelings. In contrast to the measure that we employ with the CNEP data, this variable represents a horizontal measure of affective polarization that focuses on citizens’ feelings towards other partisans rather than parties. Moreover, in line with various existing studies (Röllicke, Reference Röllicke2023; Vanagt, Reference Vanagt2024), this measure only captures out‐group dislike as the core tenet of affective polarization and thus omits the in‐group component from the equation. This allows us to test whether our findings remain robust across a different but commonly employed measurement of affective polarization.

Dependent variable

Respondents’ democratic attitudes are measured in two main ways by Voelkel and colleagues (Reference Voelkel, Chu, Stagnaro, Mernyk, Redekopp, Pink, Druckman, Rand and Willer2023). First, the authors tap into respondents’ support for undemocratic practices that prioritize partisan ends over democratic means with the use of five items. One example of an item is ‘[Democrats/Republicans] should redraw districts to maximize their potential to win more seats in federal elections, even if it may be technically illegal’. Second, the authors capture respondents’ support for undemocratic candidates with items like: ‘How likely would you be to vote for the [Democratic/Republican] candidate if you learned that they support a proposal to reduce the number of polling stations in areas that support the [Republican/Democratic] party?’. For more details on the wording of the items, control variables, and estimation strategy, see Supporting Information M.

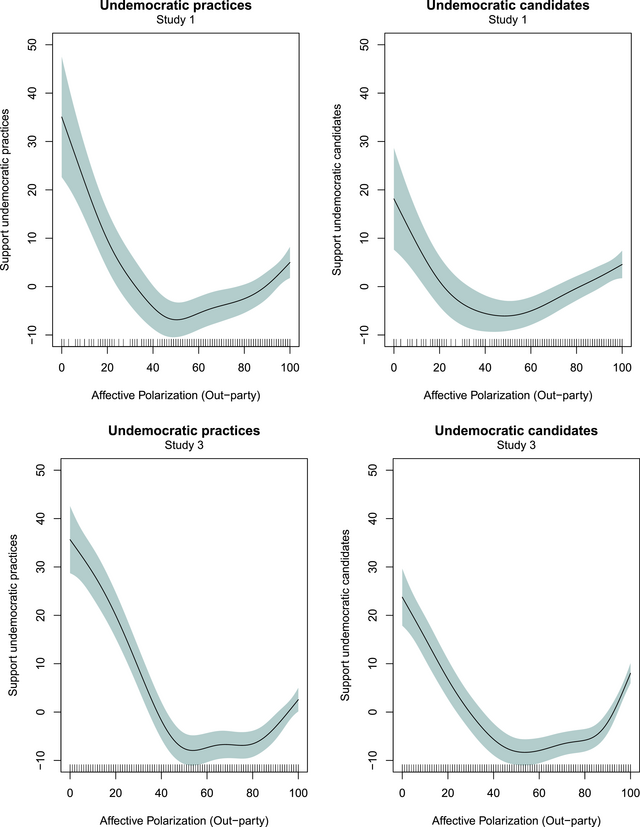

We again ran GAMs to test for non‐linear patterns between horizontal affective polarization and the support for undemocratic practices and candidates. The results of these models are presented in Figure 3.Footnote 7 We document a curvilinear trend across both study 1 and study 3, and across both measures of democratic support. These findings are fundamentally similar to our results of the CNEP‐data and illustrate that citizens are least likely to support undemocratic practices and candidates when they do not feel too warm or too cold towards out‐partisans. This additional analysis further speaks to the robustness of our findings, showing that non‐linear trends are also documented when relying on different measures of affective polarization and democratic support.

Figure 3. The shape of the relationship between affective polarization and support for undemocratic practices and candidates based on GAMs (95 per cent confidence intervals).

Conclusion

Many scholars warn that affective polarization undermines citizens’ support for basic democratic principles and ideals. Surprisingly, however, most of these concerns are voiced in the absence of clear empirical evidence: to date, research on the relationship between affective polarization and democratic support has yielded mixed results. We posit that these inconsistent findings could partially be explained by a non‐linear relationship between affective polarization and democratic support. Theoretically, we argue that, while a certain amount of affective polarization could be beneficial for citizens’ support by stimulating a feeling of in‐group belonging and democratic representation, extreme levels of polarization may in turn have an eroding impact by driving a negative view of the political opponent as an existential threat to one's way of life. As such, we hypothesized that the relationship between affective polarization and democratic support follows a negatively curvilinear pattern.

Drawing on the empirical approach of Torcal and Magalhães (Reference Torcal and Magalhães2022), we employed GAMs on CNEP‐data collected in Germany, the UK and the US. The results of the GAMs showed support for our hypothesis that the relationship between party affective polarization and democratic support is negatively curvilinear. We thus demonstrate that the democratic support of citizens is maximized when their level of affective polarization is neither very low nor very high. These results suggest that there may be a ‘sweet spot’ at which citizens are affectively polarized enough to be democratically involved and feel represented, whilst not being so polarized that they prioritize their preferred party (or the demise of the opposing party) over democratic principles.

Our results have important implications for the normative assessment of the phenomenon of affective polarization. Although dystopian accounts of the consequences of affective polarization are widespread in the academic literature, we theorize that there might be another side of the coin: A certain degree of affective polarization could be beneficial – possibly even indispensable – for citizens’ democratic attitudes. We demonstrate that party affective polarization is not as straightforwardly related to the erosion of democratic principles as scholars have previously assumed. While our research design precludes causal claims, our findings question the belief that rising levels of party affective polarization invariably have negative implications for democracy. Rather, it might be the number of citizens positioned at the extremes – that is, those with extremely low or extremely high levels of affective polarization – that warrant attention. Hence, in line with recent European work (Berntzen et al., Reference Berntzen, Kelsall and Harteveld2024; Harteveld et al., Reference Harteveld, Berntzen, Kokkonen, Kelsall, Linde and Dahlberg2023; Wagner, Reference Wagner2024), we advocate for a more nuanced discussion about the normative assessment of affective polarization in which both alarmism and complacency are avoided.

Importantly, this research note challenges the prevalent assumption of linearity in the study of the political consequences of party affective polarization. Our findings indicate that by (implicitly) assuming linear patterns, scholars may overlook important nuances and dynamics in the relationship between affective polarization and democratic support that are crucial to our understanding of these phenomena and how they relate to one another. Hence, we recommend future studies to acknowledge and incorporate the possibility of non‐linear trends – and more specifically negatively curvilinear trends – in their estimation strategies. Concretely, we recommend the incorporation of quadratic terms in regressions or the use of GAMs. Moreover, scholars examining the moderating effects of affective polarization can benefit from the recommendations of Hainmueller and colleagues (Reference Hainmueller, Mummolo and Xu2019) on estimating non‐linear interactions. These statistical approaches are better equipped to capture the complex interplay between affective polarization and democratic support, thereby mitigating the risk of drawing inaccurate conclusions.

Despite these relevant contributions, this research note is not without its limitations. First, our study alone cannot resolve the mixed findings in earlier research. The contradictory results across prior studies can be attributed to several factors beyond mis‐estimated non‐linearity, including differences in the countries examined, the methods employed and the measurements used. Importantly, whilst a curvilinear pattern emerged in all three cases studied here, affective polarization can manifest in different ways across (institutional) contexts with varying boundary conditions (e.g., Bantel, Reference Bantel2023; Bernaerts et al., Reference Bernaerts, Blanckaert and Caluwaerts2023). Disentangling the impact of country‐level characteristics, such as the degree of proportionality, warrants further theorizing and testing. Therefore, future research that relaxes linearity assumptions is essential to gain a more comprehensive understanding of how affective polarization impacts democratic attitudes and the contexts in which these effects are most pronounced.

Second, given the cross‐sectional nature of the data, we are unable to make causal inferences. Though we theoretically argue that party affective polarization influences democratic attitudes, other scholars have argued for the possibility of reversed causality (Guedes‐Neto, Reference Guedes‐Neto2023). One could, for instance, posit that citizens with limited pro‐democratic attitudes are more inclined to start loathing political opponents or make less effort to affectively differentiate the political parties. As a result, endogeneity resulting from reversed causality cannot be ruled out. Future work is needed to shed light on the causal effect of affective polarization on democratic support (or vice versa) while simultaneously accounting for non‐linear patterns. Another promising avenue for future research is to examine the determinants of the positioning of the ‘tipping point’ in the curve. The exact level at which party affective polarization starts to erode democratic support is likely not an immovable, stable given. Gaining insights into country‐ and individual‐level characteristics that explain when and why affective polarization starts to undermine citizens’ democratic support is pivotal for developing effective strategies that counteract its possible adverse political consequences. Moreover, longitudinal work may prove useful to assess how such a tipping point evolves over time in different contexts.

Implicit assumptions of linearity are prevalent in many research fields, extending beyond the topics of affective polarization and democratic support (see also Hainmueller et al., Reference Hainmueller, Mummolo and Xu2019). We hope this research note stimulates a critical reflection amongst researchers about the established norm of linearity in our research practices.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Anna Kern and Hannah Werner for their valuable advice and input on this study. Previous versions of this paper were presented at the EPSA Annual Conference in Glasgow, as well as the Ghent University GASPAR seminar. We thank all participants for their insightful suggestions and helpful feedback. Finally, we extend our gratitude to the editors and four anonymous reviewers for their comments and suggestions.

Funding

This study was supported by the Belgian FNRS‐FWO EOS project NOTLIKEUS (project no. 40007494). In addition, the study has received funding from the Research Foundation Flanders (FWO) through a personal PhD fellowship under the grant 11P7Y24N.

Conflict of interests

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Data availability statement

An anonymized replication package, including instructions for downloading the publicly available datasets and the full syntax, is available at: https://osf.io/hu6f3/?view_only=dcf2f301b9c7491db8d7cf5c3b02466e

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article: