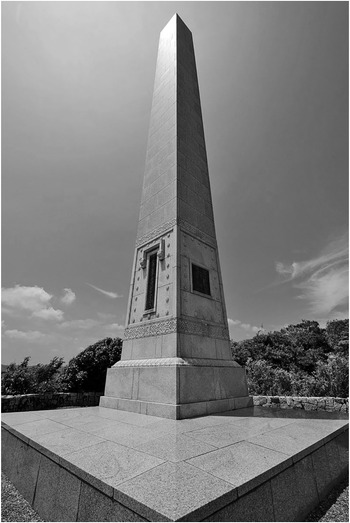

In 1928 a ‘friendship testimonial’ in the form of an obelisk was erected in the Japanese town of Onjuku in Chiba (see Figure P.1).Footnote 1 The obelisk stands at the presumed site where the Spanish colonial official Don Rodrigo de Vivero (1564–1636) stepped ashore after being rescued from a shipwrecked journey from the Philippines to Mexico in 1609. This Prefectural Historic Monument, known as the Mexico Commemorative Tower, manifests historical ties with Chiba’s sister city Acapulco across the Pacific.Footnote 2 A year after the construction of the obelisk, historian Murakami Naojirō (村上直次郎, 1868–1966) published a Japanese translation of Vivero’s memories of Japan.Footnote 3 Murakami, a prolific scholar and part of the Japanese academic establishment, had used Vivero’s report for the Spanish king and other sources from the Spanish archive a few years earlier to historicize Japan’s seventeenth-century transpacific exchange.Footnote 4 In this process, he moreover framed the encounter between the stranded Spanish nobleman and the Japanese ruler Tokugawa Ieyasu (1543–1616) as an act of friendly state relations and the beginning of Japan’s official diplomatic negotiations with Mexico and Spain. Hence, his research laid the foundation for the lavish trilateral commemorations in Japan, Mexico, and Spain between 2009 and 2014.

Figure P.1 Onjuku Japan–Spain–Mexico Commemorative Tower (日西墨三国交通発祥記念之碑). The monument was erected in 1928 to commemorate the rescue of the capsized Spanish galleon San Felipe on its way from Manila to Acapulco.

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/日西墨三国交通発祥記念之碑

Celebrating ‘four hundred years of friendship’ in 2009, Onjuku’s mayor Ishida Yoshiro stressed that the prosperity of both Pacific countries started with the encounter in the 1600s, while Mexican ambassador to Japan, Miguel Ruiz Cabañas Izquierda, emphasized that the Mexican people would never forget the heroic actions of local fishermen and female divers (ama) in rescuing the 317 shipwrecked passengers.Footnote 5 What most historians would intuitively debunk as myth-building was a powerful act of cultural diplomacy. Communities, nation-states, and civil actors use historical memory to engage target audiences and ultimately influence which aspects of the past are remembered and how.Footnote 6 As historical memory overlaps with tourism, new meanings enter globalized memory regimes.Footnote 7 In the case of the anniversary of bilateral friendship in 2009 and the 2013–14 biennial (año dual in Spanish official jargon), commemorative initiatives were approved by the heads of the Japanese and Spanish governments at an official meeting in Tokyo.Footnote 8 Hundreds of thousands visited museums and libraries in Seville, Madrid, Valladolid, Sendai, Mexico City, Osaka, and Tokyo, where diplomatic documents from the early 1600s were displayed. In addition, exhibition catalogs, online blogs, and stage performances contributed to the legacy of the past encounter and created new archives and sites for commemoration. Japanese policymakers encouraged visitors to study the history of friendship (yūkō, 友好) between Japan, Spain, Mexico, and the Philippines.Footnote 9 The language of ‘friendship,’ ‘relaciones diplomaticas,’ ‘relaciones amistosas,’ or heiwa gaikō (peaceful foreign relations) has become ubiquitous in this historicizing process. Yet, while seemingly source terms, none of these catchy phrases appeared in archival records of the seventeenth century. They were instead semantic and linguistic creations that originated in the mid-nineteenth century and were made available through archival diplomacy.