1. Introduction

1.1. Floating bubbles: a prelude to bursting

Bubble dynamics (Magnaudet & Eames Reference Magnaudet and Eames2000; Prosperetti Reference Prosperetti2004; Mathai, Lohse & Sun Reference Mathai, Lohse and Sun2020; Marusic & Broomhall Reference Marusic and Broomhall2021; Cardoso & Cartwright Reference Cardoso and Cartwright2024) has long been one of the most fascinating problems in fluid flow research, captivating scientists for centuries. Bubbles are ubiquitous, appearing in diverse environments, from nanoscale (Lohse & Zhang Reference Lohse and Zhang2015; Zhu et al. Reference Zhu, Verzicco, Zhang and Lohse2018) and microfluidic lab-on-chip systems (Bertin et al. Reference Bertin, Spelman, Stephan, Gredy, Bouriau, Lauga and Marmottant2015; Li et al. Reference Li, Liu, Huang, Ohta and Arai2021) to oceanic wave breaking (Deane & Stokes Reference Deane and Stokes2002; Chan et al. Reference Chan, Mirjalili, Jain, Urzay, Mani and Moin2019). Beyond their rich physics, research into bubbles is heavily driven by their significance in real-world applications, including biomedical science (Dollet, Marmottant & Garbin Reference Dollet, Marmottant and Garbin2019), heat transfer augmentation (Gvozdić et al. Reference Gvozdić, Alméras, Mathai, Zhu, van Gils, Verzicco, Huisman, Sun and Lohse2018) and drag reduction (Ceccio Reference Ceccio2010), among others.

Multiphase flows containing suspensions of gas bubbles floating near the liquid–gas free surface arise through a variety of mechanisms in practice. For example, frequent wave-breaking events at the free surface of the ocean result in the production of multiscale gas bubbles through air entrainment in seawater (Deane & Stokes Reference Deane and Stokes2002; Chan et al. Reference Chan, Johnson, Moin and Urzay2021; Deike Reference Deike2022; Mostert, Popinet & Deike Reference Mostert, Popinet and Deike2022). These bubbles eventually rise to the free surface and burst, releasing seawater droplets – known as sea spray (Veron Reference Veron2015; Villermaux, Wang & Deike Reference Villermaux, Wang and Deike2022). Before bursting, however, these bubbles remain afloat at the free surface, supported by a thin water film that separates the bubble’s top from the free surface The nature of the ensuing bursting event and the resulting spray droplets are regulated by the equilibrium shape of floating bubbles, which is one of the focus points of this article. In addition to the formation of sea spray, the study of floating bubbles and how they burst is crucial for understanding the release of greenhouse gases such as methane (Shakhova et al. Reference Shakhova2013) and how oil disperses into seawater through reverse mass transport during an oil spill at the surface (Feng et al. Reference Feng, Roché, Vigolo, Arnaudov, Stoyanov, Gurkov, Tsutsumanova and Stone2014). Furthermore, understanding the geometrical arrangement of liquid-channel networks in thick foam layers is central to studying the transport of phytoplankton cells in marine foams (Roveillo et al. Reference Roveillo, Dervaux, Wang, Rouyer, Zanchi, Seuront and Elias2020), a process that strongly influences the dynamics of marine ecosystems. Bubbles formed through the effervescence process can also be observed floating in a glass of carbonated beverage, such as champagne (Liger-Belair, Polidori & Jeandet Reference Liger-Belair, Polidori and Jeandet2008). When liquid jets impact the free surface, they entrain gas bubbles into the liquid (Li, Yang & Zhang Reference Li, Yang and Zhang2024), which subsequently rise and may accumulate as floating bubbles at the interface. Thus, floating bubbles are omnipresent across various settings and have broader implications.

The geometry of a floating bubble in the equilibrium state is determined by the dimensionless Bond number

![]() $\textit{Bo}=\mathcal{O}{ (\text{gravitational forces} )}/\mathcal{O}{ (\text{surface tension forces} )}=4\rho _{l}gR^{2}_{0}/\sigma$

, where

$\textit{Bo}=\mathcal{O}{ (\text{gravitational forces} )}/\mathcal{O}{ (\text{surface tension forces} )}=4\rho _{l}gR^{2}_{0}/\sigma$

, where

![]() $\rho _{l}$

,

$\rho _{l}$

,

![]() $g$

,

$g$

,

![]() $R_{0}$

, and

$R_{0}$

, and

![]() $\sigma$

denote the density of the surrounding liquid, acceleration due to gravity, bubble radius in the spherical state, and surface tension of the bubble interface and free surface, respectively. As an illustrative example of typical Bond numbers in natural processes, we refer to bubbles entrained during breaking waves, whose subsurface size distributions have been rigorously characterised in prior studies and provide a useful reference. The bubble-size density

$\sigma$

denote the density of the surrounding liquid, acceleration due to gravity, bubble radius in the spherical state, and surface tension of the bubble interface and free surface, respectively. As an illustrative example of typical Bond numbers in natural processes, we refer to bubbles entrained during breaking waves, whose subsurface size distributions have been rigorously characterised in prior studies and provide a useful reference. The bubble-size density

![]() $\mathcal{P}$

of subsurface bubbles formed during the acoustic or active breaking phase follows two distinct scaling laws relative to the Hinze scale

$\mathcal{P}$

of subsurface bubbles formed during the acoustic or active breaking phase follows two distinct scaling laws relative to the Hinze scale

![]() $a_{h}$

(Deane & Stokes Reference Deane and Stokes2002; Deike Reference Deike2022; Di Giorgio, Pirozzoli & Iafrati Reference Di Giorgio, Pirozzoli and Iafrati2022; Mostert et al. Reference Mostert, Popinet and Deike2022), as shown in figure 1. For bubbles with radii

$a_{h}$

(Deane & Stokes Reference Deane and Stokes2002; Deike Reference Deike2022; Di Giorgio, Pirozzoli & Iafrati Reference Di Giorgio, Pirozzoli and Iafrati2022; Mostert et al. Reference Mostert, Popinet and Deike2022), as shown in figure 1. For bubbles with radii

![]() $R_{0}\lt a_{h}$

(sub-Hinze regime), surface tension dominates, preventing further fragmentation. In contrast, bubbles with

$R_{0}\lt a_{h}$

(sub-Hinze regime), surface tension dominates, preventing further fragmentation. In contrast, bubbles with

![]() $R_{0}\gt a_{h}$

(super-Hinze regime) can continue breaking into smaller bubbles due to turbulence. The super-Hinze regime accounts for

$R_{0}\gt a_{h}$

(super-Hinze regime) can continue breaking into smaller bubbles due to turbulence. The super-Hinze regime accounts for

![]() $95\,\%$

of the entrained air volume (Deike Reference Deike2022). Typically,

$95\,\%$

of the entrained air volume (Deike Reference Deike2022). Typically,

![]() $a_{h}$

ranges between

$a_{h}$

ranges between

![]() $1$

and

$1$

and

![]() $2$

mm (Deike Reference Deike2022). To translate dimensionless bubble sizes

$2$

mm (Deike Reference Deike2022). To translate dimensionless bubble sizes

![]() $R_{0}/a_{h}$

into corresponding Bond numbers in figure 1, we set

$R_{0}/a_{h}$

into corresponding Bond numbers in figure 1, we set

![]() $a_{h}=1.5$

mm and the capillary length

$a_{h}=1.5$

mm and the capillary length

![]() $\sqrt {\sigma /(\rho _{l}g)}=2.7$

mm for seawater. Each decade in either the sub- or super-Hinze regime corresponds to approximately two decades in the Bond number (see figure 1).

$\sqrt {\sigma /(\rho _{l}g)}=2.7$

mm for seawater. Each decade in either the sub- or super-Hinze regime corresponds to approximately two decades in the Bond number (see figure 1).

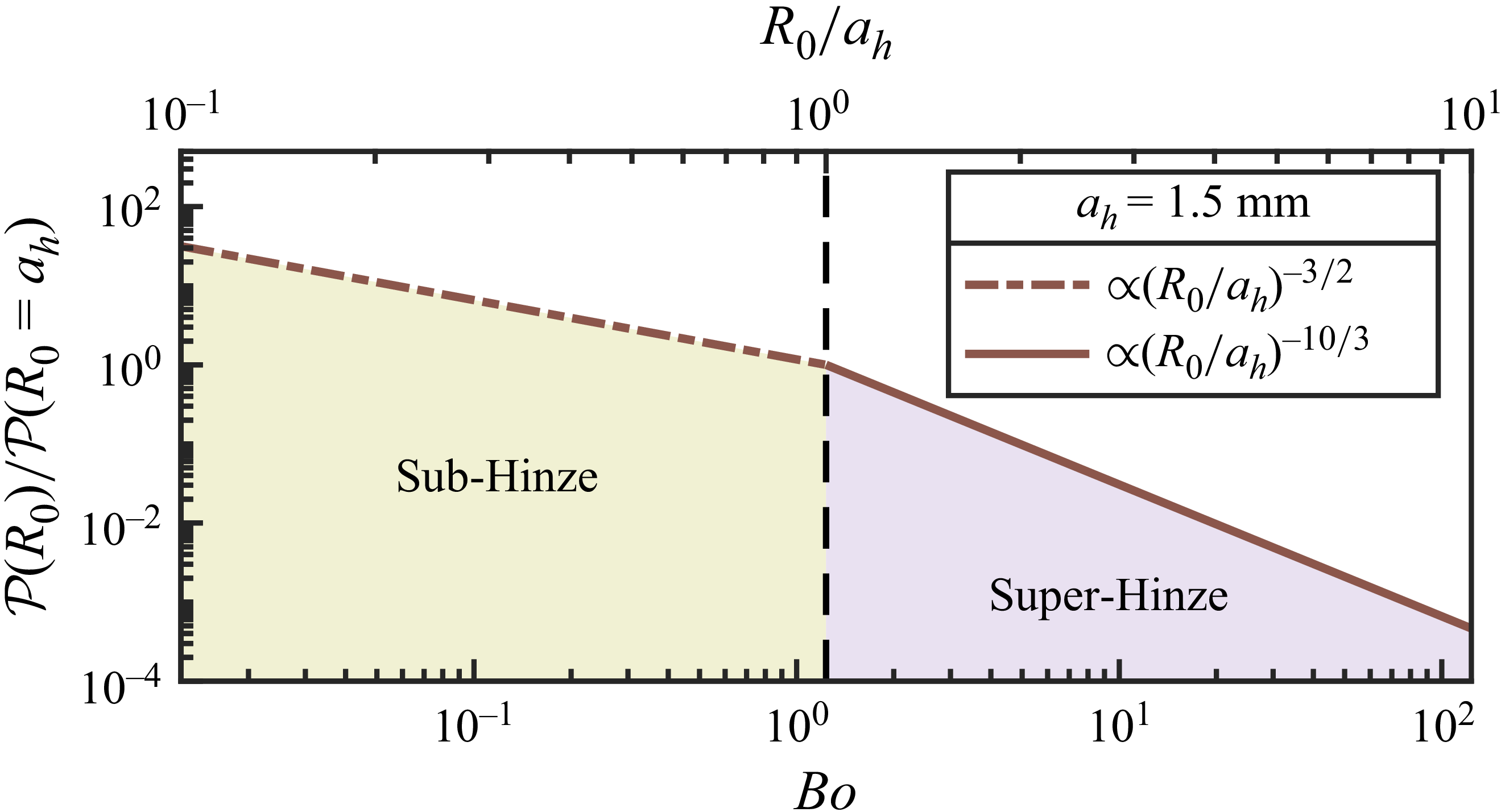

Figure 1. During the acoustic phase of wave breaking in the ocean, the bubble-size density

![]() $\mathcal{P}(R_{0})$

varies according to two distinct scaling laws:

$\mathcal{P}(R_{0})$

varies according to two distinct scaling laws:

![]() $\mathcal{P}\propto (R_{0}/a_{h})^{{-}3/2}$

for bubble sizes

$\mathcal{P}\propto (R_{0}/a_{h})^{{-}3/2}$

for bubble sizes

![]() $R_{0}$

smaller than the Hinze scale

$R_{0}$

smaller than the Hinze scale

![]() $a_{h}$

(sub-Hinze regime) and

$a_{h}$

(sub-Hinze regime) and

![]() $\mathcal{P}\propto (R_{0}/a_{h})^{{-}10/3}$

for larger bubbles (super-Hinze regime). The

$\mathcal{P}\propto (R_{0}/a_{h})^{{-}10/3}$

for larger bubbles (super-Hinze regime). The

![]() $x$

-axis shows the Bond numbers

$x$

-axis shows the Bond numbers

![]() $\textit{Bo}$

obtained from dimensionless bubble sizes

$\textit{Bo}$

obtained from dimensionless bubble sizes

![]() $R_{0}/a_{h}$

by setting

$R_{0}/a_{h}$

by setting

![]() $a_{h}=1.5$

mm.

$a_{h}=1.5$

mm.

In our simulations of floating bubbles, we probe bubble sizes in the range

![]() $10^{-1}\leqslant \textit{Bo}\leqslant 10^{2}$

, covering three decades. While relatively large floating bubbles can be realised under laboratory conditions (Lhuissier & Villermaux Reference Lhuissier and Villermaux2012; Kocárková et al. Reference Kocárková, Rouyer and Pigeonneau2013; Bartlett et al. Reference Bartlett, Oratis, Santin and Bird2023), they are less likely to be prevalent in natural settings. For instance, subsurface bubbles in the super-Hinze regime with

$10^{-1}\leqslant \textit{Bo}\leqslant 10^{2}$

, covering three decades. While relatively large floating bubbles can be realised under laboratory conditions (Lhuissier & Villermaux Reference Lhuissier and Villermaux2012; Kocárková et al. Reference Kocárková, Rouyer and Pigeonneau2013; Bartlett et al. Reference Bartlett, Oratis, Santin and Bird2023), they are less likely to be prevalent in natural settings. For instance, subsurface bubbles in the super-Hinze regime with

![]() $\textit{Bo}\gt 10$

in figure 1 often disintegrate into smaller bubbles due to background turbulence in the ocean while rising towards the free surface. Consequently, floating bubbles with Bond numbers exceeding

$\textit{Bo}\gt 10$

in figure 1 often disintegrate into smaller bubbles due to background turbulence in the ocean while rising towards the free surface. Consequently, floating bubbles with Bond numbers exceeding

![]() $10$

are generally not expected to persist at the ocean surface (Néel & Deike Reference Néel and Deike2021). Although our range of

$10$

are generally not expected to persist at the ocean surface (Néel & Deike Reference Néel and Deike2021). Although our range of

![]() $\textit{Bo}$

already includes the typical values observed for surface bubbles in the ocean, we extend beyond this range to investigate fundamental aspects of floating-bubble dynamics.

$\textit{Bo}$

already includes the typical values observed for surface bubbles in the ocean, we extend beyond this range to investigate fundamental aspects of floating-bubble dynamics.

Figure 2 illustrates an example of the equilibrium shape of a bubble resting beneath the free surface. When gravitational forces are relatively weak, the extent of the spherical-cap region depicted in figure 2 remains relatively small. In such scenarios, the rupture of the liquid film above the bubble leads to the collapse of the bubble cavity in figure 2 due to a sudden drop in pressure. This collapse triggers the formation of an unstable Worthington or Rayleigh jet, which ejects jet droplets through its pinch-off (Woodcock et al. Reference Woodcock, Kientzler, Arons and Blanchard1953; Blanchard Reference Blanchard1963). Conversely, for larger bubbles with significant free-surface deformation, the nucleation of a hole in the liquid cap results in the fragmentation of the film, producing film droplets (Knelman, Dombrowski & Newitt Reference Knelman, Dombrowski and Newitt1954; Spiel Reference Spiel1998). The droplet-size distribution resulting from the bursting process at the ocean surface has far-reaching consequences. For instance, smaller spray droplets drift into the atmospheric boundary layer for days, acting as cloud condensation nuclei, while larger droplets play a key role in regulating the momentum and enthalpy flux at the ocean–atmosphere boundary, influencing the intensity of tropical cyclones (Veron Reference Veron2015; Deike Reference Deike2022).

Figure 2. Schematic of an axisymmetric air bubble floating at the air–water interface. Here,

![]() $\alpha$

and

$\alpha$

and

![]() $R_c$

denote the contact angle and the radius of the spherical cap, respectively, while

$R_c$

denote the contact angle and the radius of the spherical cap, respectively, while

![]() $\beta$

is the angle between the local interface normal at position (

$\beta$

is the angle between the local interface normal at position (

![]() $r,z$

) and the negative

$r,z$

) and the negative

![]() $z$

-direction.

$z$

-direction.

Building upon the identification of bubble-bursting mechanisms, a plethora of research has been conducted on jet (Zeff et al. Reference Zeff, Kleber, Fineberg and Lathrop2000; Duchemin et al. Reference Duchemin, Popinet, Josserand and Zaleski2002; Ghabache et al. Reference Ghabache, Antkowiak, Josserand and Séon2014; Walls, Henaux & Bird Reference Walls, Henaux and Bird2015; Gañán-Calvo Reference Gañán-Calvo2017; Krishnan, Hopfinger & Puthenveettil Reference Krishnan, Hopfinger and Puthenveettil2017; Brasz et al. Reference Brasz, Bartlett, Walls, Flynn, Yu and Bird2018; Deike et al. Reference Deike, Ghabache, Liger-Belair, Das, Zaleski, Popinet and Séon2018; Gañán-Calvo Reference Gañán-Calvo2018; Lai, Eggers & Deike Reference Lai, Eggers and Deike2018; Blanco–Rodríguez & Gordillo Reference Blanco–Rodríguez and Gordillo2020) and film (Wu Reference Wu2001; Lhuissier & Villermaux Reference Lhuissier and Villermaux2012; Modini et al. Reference Modini, Russell, Deane and Stokes2013; Ke et al. Reference Ke, Kuo, Lin, Huang and Chen2017; Poulain, Villermaux & Bourouiba Reference Poulain, Villermaux and Bourouiba2018; Shaw & Deike Reference Shaw and Deike2024) droplets to better understand the breakup process, as well as the resulting counts and sizes of droplets generated by the burst of an isolated floating bubble. To link various dynamic phenomena occurring during the bursting process – such as film drainage, velocity of the Worthington jet and the quantity of aerosols released – with the bubble’s shape, Puthenveettil et al. (Reference Puthenveettil, Saha, Krishnan and Hopfinger2018) developed closed-form expressions for several geometrical parameters of an isolated floating bubble under conditions where

![]() $\textit{Bo}\leqslant 10$

. They also validated their theoretical bubble shapes through experiments. Moreover, various other semi-analytical and experimental studies on the geometry of a single bubble, either floating at the free surface (Nicolson Reference Nicolson1949; Toba Reference Toba1959; Medrow & Chao Reference Medrow and Chao1971; Howell Reference Howell1999; Teixeira et al. Reference Teixeira, Arscott, Cox and Teixeira2015) or resting on a substrate (Cohen et al. Reference Cohen, Texier, Reyssat, Snoeijer, Quéré and Clanet2017; Brubaker Reference Brubaker2021), have also been pursued as standalone problems.

$\textit{Bo}\leqslant 10$

. They also validated their theoretical bubble shapes through experiments. Moreover, various other semi-analytical and experimental studies on the geometry of a single bubble, either floating at the free surface (Nicolson Reference Nicolson1949; Toba Reference Toba1959; Medrow & Chao Reference Medrow and Chao1971; Howell Reference Howell1999; Teixeira et al. Reference Teixeira, Arscott, Cox and Teixeira2015) or resting on a substrate (Cohen et al. Reference Cohen, Texier, Reyssat, Snoeijer, Quéré and Clanet2017; Brubaker Reference Brubaker2021), have also been pursued as standalone problems.

To date, most studies in the literature have concentrated on the flotation and bursting of individual bubbles, which is justified considering the intricate nature of the problem. However, the effervescence of carbonated liquids and the breaking of free-surface waves in the ocean generate large swarms of bubbles, e.g. figure 1 in Liger-Belair et al. (Reference Liger-Belair, Polidori and Jeandet2008) and figure 2 in Deike (Reference Deike2022). As these bubbles rise to the free surface under buoyancy, they form layers of aqueous foam containing floating bubbles, commonly referred to as whitecaps in the context of ocean–atmosphere interface (see figure 1 in Néel & Deike Reference Néel and Deike2021). Thus, the floating state of bubbles and their subsequent bursting at the free surface are typically collective phenomena, influenced by interactions with surrounding bubbles within the foam.

Ritacco, Kiefer & Langevin (Reference Ritacco, Kiefer and Langevin2007) previously investigated the bursting cascade triggered by the collapse of an interior bubble in the foam. Their study observed that such a cascade is realised only when the surrounding liquid has a sufficiently low viscosity. At higher values of viscosity, bubbles within the foam tend to burst independently, unaffected by other bursting events. Singh & Das (Reference Singh and Das2019) conducted numerical simulations to quantify the tilting of the Worthington jet during bubble bursting in the presence of up to six neighbouring bubbles arranged in different configurations. More recently, Néel & Deike (Reference Néel and Deike2021) performed controlled experiments on collective bursting involving multiple floating bubbles. Their experiments revealed that bubbles with surfactant-laden interfaces – mimicking the ocean surface partially covered with biofilm (Wurl et al. Reference Wurl, Wurl, Miller, Johnson and Vagle2011) – are able to sustain their floating state for an extended period by avoiding coalescence with neighbouring bubbles and the free surface, thereby producing raft-like structures at the free surface. Furthermore, spray droplets produced from bursting bubbles in these raft-like formations travel at lower vertical velocities than those predicted from single-bubble bursting experiments (Néel & Deike Reference Néel and Deike2022).

Based on our preceding discussion in this section, in the first part of our study, we numerically (computational details in § 2) investigate the geometry of a floating bubble pair in the state of equilibrium. When the free surface is already populated with floating bubbles in systems with lateral confinement, the fresh bubbles migrating at the surface accumulate below an already existing layer of floating bubbles. A glass of carbonated beverage provides one such of example, where stacked bubbles and foam layers can be realised. A simple home experiment shows that pouring a can of soda into a glass can produce a thick multilayer foam of bubbles, lasting several seconds. The formation and thickness of such foam layers, however, depend strongly on carbonation level, liquid temperature, glass cleanliness and pouring technique. For instance, figures 21 and 31 in Liger-Belair et al. (Reference Liger-Belair, Polidori and Jeandet2008) illustrate these configurations. Although such layered configurations of bubbles are often transient or short-lived in carbonated beverages, they may persist longer in the presence of surfactant-laden interfaces. As bubbles in the upper layer burst through film drainage and the stack gradually thins, the shape of the individual bubbles within the stack remains essentially unchanged during drainage because the film is several orders of magnitude thinner than the bubble itself. When a new interior layer becomes the top layer, its bubbles can adjust their shape long before their spherical cap drains. Thus, even though the foam evolves over time, the bubbles can be regarded as being in a geometrically quasi-steady state. In multilayer foams, bubbles within the top layer experience added force from bubbles beneath them, which may dramatically alter their shape in comparison with an isolated floating bubble. These shape changes can substantially impact how bubbles burst and the amount of spray produced. Motivated by this, we start with an axisymmetric pair of coaxial bubbles in § 3. We report various geometrical measurements for a Bond number range of

![]() $0.1\leqslant \textit{Bo}\leqslant 10$

and compare them with a single-bubble counterpart over the range of

$0.1\leqslant \textit{Bo}\leqslant 10$

and compare them with a single-bubble counterpart over the range of

![]() $0.1\leqslant \textit{Bo}\leqslant 100$

. We then connect the changes in shape parameters between single and coaxial floating bubbles to various aspects of the bursting process, including the onset of transition from jet to film droplets, spherical cap drainage and the velocity scaling of the Worthington jet. We also derive generalised analytical shape parameters that apply to both single and coaxial floating bubbles in the weak-deformation limit.

$0.1\leqslant \textit{Bo}\leqslant 100$

. We then connect the changes in shape parameters between single and coaxial floating bubbles to various aspects of the bursting process, including the onset of transition from jet to film droplets, spherical cap drainage and the velocity scaling of the Worthington jet. We also derive generalised analytical shape parameters that apply to both single and coaxial floating bubbles in the weak-deformation limit.

Subsequently, we focus on three-dimensional cases with two or more bubbles floating along the free surface. This is again motivated by the appearance of whitecaps in the ocean and foams in carbonated drinks. Bubbles, droplets and particles residing at the free surface are known to exhibit hydrodynamic attraction or repulsion (see figure 8 in Bush, Hu & Prakash Reference Bush, Hu and Prakash2007) as a consequence of the minimisation of surface and gravitational potential energies. When two or more bubbles are floating in close vicinity, the cylindrical symmetry of the spherical-cap region of individual bubbles and the surrounding meniscus breaks down, thereby inducing non-zero lateral capillary forces that lead to the self-organisation of floating bubbles into a bubble raft. This phenomenon is often referred to as the Cheerios effect (Vella & Mahadevan Reference Vella and Mahadevan2005), as also seen in a bowl full of floating breakfast cereals. Beyond floating objects, self-assembly is frequently observed in a wide range of settings and across different scales (Whitesides & Grzybowski Reference Whitesides and Grzybowski2002).

The capillary interaction between floating rigid objects has been extensively studied (Chan, Henry & White Reference Chan, Henry and White1981; Allain & Cloitre Reference Allain and Cloitre1993; Cavallaro et al. Reference Cavallaro, Botto, Lewandowski, Wang and Stebe2011; Dalbe et al. Reference Dalbe, Cosic, Berhanu and Kudrolli2011; Ho, Pucci & Harris Reference Ho, Pucci and Harris2019; Delens, Collard & Vandewalle Reference Delens, Collard and Vandewalle2023; Protière Reference Protière2023), whereas deformable objects such as bubbles (Nicolson Reference Nicolson1949), droplets (Karpitschka et al. Reference Karpitschka, Pandey, Lubbers, Weijs, Botto, Das, Andreotti and Snoeijer2016; Gauthier et al. Reference Gauthier, van der Meer, Snoeijer and Lajoinie2019) and capsules (Wouters et al. Reference Wouters, Aouane, Sega and Harting2020) have garnered relatively less attention. In particular, the clustering of floating bubbles in direct numerical simulations was only recently demonstrated by Karnakov, Litvinov & Koumoutsakos (Reference Karnakov, Litvinov and Koumoutsakos2022). In our numerical investigation discussed in § 4, we systematically examine the capillary attraction between two side-by-side floating bubbles by varying the Bond number

![]() $\textit{Bo}$

and their initial separation. We observe that, for a fixed initial spacing between bubbles, the assembly time required to form a two-bubble raft declines as the Bond number increases. However, the trend reverses beyond a critical Bond number. At a fixed Bond number, the assembly time increases exponentially with the initial spacing between two bubbles. We also construct a linear model following the work of Nicolson (Reference Nicolson1949) to recover the time variation of the bubble spacing during capillary migration in the low-Bond-number limit. The model shows good agreement with simulation results. Then, in § 5, we showcase the emergence of bubble rafts and chains through the self-organisation of multiple floating bubbles, starting from a random initialisation. In particular, we investigate how this collective behaviour unfolds in both monolayer and bilayer swarms. To quantify the self-organisation process, we measure the instantaneous migration velocity of each bubble, track the evolution of polar order in the system based on the direction of movement of each bubble, and calculate the

$\textit{Bo}$

and their initial separation. We observe that, for a fixed initial spacing between bubbles, the assembly time required to form a two-bubble raft declines as the Bond number increases. However, the trend reverses beyond a critical Bond number. At a fixed Bond number, the assembly time increases exponentially with the initial spacing between two bubbles. We also construct a linear model following the work of Nicolson (Reference Nicolson1949) to recover the time variation of the bubble spacing during capillary migration in the low-Bond-number limit. The model shows good agreement with simulation results. Then, in § 5, we showcase the emergence of bubble rafts and chains through the self-organisation of multiple floating bubbles, starting from a random initialisation. In particular, we investigate how this collective behaviour unfolds in both monolayer and bilayer swarms. To quantify the self-organisation process, we measure the instantaneous migration velocity of each bubble, track the evolution of polar order in the system based on the direction of movement of each bubble, and calculate the

![]() $6$

-fold bond orientational parameter. Finally, we close our discussion with concluding remarks in § 6.

$6$

-fold bond orientational parameter. Finally, we close our discussion with concluding remarks in § 6.

2. Multi-volume-of-fluid formulation

2.1. Implementation

One of the primary challenges in simulating floating bubbles is the high grid resolution required to resolve the thin liquid film in the spherical-cap region (as shown in figure 2). To alleviate this, the weight of the film can be neglected in determining the bubble shape since its thickness, typically a few microns for a millimetric bubble (Lhuissier & Villermaux Reference Lhuissier and Villermaux2012; Shaw & Deike Reference Shaw and Deike2024), is orders of magnitude smaller than the bubble radius

![]() $R_{0}$

. For the film weight to matter, the bubble would need to be much larger – of the order of metres (Cohen et al. Reference Cohen, Texier, Reyssat, Snoeijer, Quéré and Clanet2017) – which exceeds the bubble sizes examined in the present work. Assuming a weightless film (spherical cap) thus simplifies the problem significantly in terms of computational efforts.

$R_{0}$

. For the film weight to matter, the bubble would need to be much larger – of the order of metres (Cohen et al. Reference Cohen, Texier, Reyssat, Snoeijer, Quéré and Clanet2017) – which exceeds the bubble sizes examined in the present work. Assuming a weightless film (spherical cap) thus simplifies the problem significantly in terms of computational efforts.

The second bottleneck is particular to the use of interface capturing techniques in multiphase flow simulations, specifically the volume-of-fluid (VOF) method employed in this study. While we do not need to resolve the liquid film at the top of the bubble, we must prevent the bubble from coalescing with the free surface. Interface capturing methods such as VOF (Hirt & Nichols Reference Hirt and Nichols1981; Popinet Reference Popinet2009), level set (Osher & Sethian Reference Osher and Sethian1988; Gibou, Fedkiw & Osher Reference Gibou, Fedkiw and Osher2018) and phase field (Patel & Stark Reference Patel and Stark2023; Roccon, Zonta & Soldati Reference Roccon, Zonta and Soldati2023) are designed to allow fluid–fluid interfaces to break and coalesce naturally, which is undesirable in our set-up. To mitigate this, we employ a multi-VOF (MVOF) approach in which each phase boundary in the flow domain is captured by a unique volume-fraction field. For example, the configuration in figure 2 can be realised in simulations by utilising two separate volume-fraction indicators

![]() $C_{1}{ (\boldsymbol{x},t )}$

and

$C_{1}{ (\boldsymbol{x},t )}$

and

![]() $C_{2}{ (\boldsymbol{x},t )}$

– one for the free surface and another for the bubble interface. The central idea of our MVOF formulation is similar to recent works on non-coalescing fluid interfaces using VOF-based simulations (Karnakov et al. Reference Karnakov, Litvinov and Koumoutsakos2022; Sanjay et al. Reference Sanjay, Lakshman, Chantelot, Snoeijer and Lohse2023; Ray et al. Reference Ray, Han, Yue, Guo, Chao and Cheng2024; Gao et al. Reference Gao, Liu, Yang and Hu2025).

$C_{2}{ (\boldsymbol{x},t )}$

– one for the free surface and another for the bubble interface. The central idea of our MVOF formulation is similar to recent works on non-coalescing fluid interfaces using VOF-based simulations (Karnakov et al. Reference Karnakov, Litvinov and Koumoutsakos2022; Sanjay et al. Reference Sanjay, Lakshman, Chantelot, Snoeijer and Lohse2023; Ray et al. Reference Ray, Han, Yue, Guo, Chao and Cheng2024; Gao et al. Reference Gao, Liu, Yang and Hu2025).

For a system comprising

![]() $\mathcal{N}_{b}$

floating bubbles and a free surface, we initialise

$\mathcal{N}_{b}$

floating bubbles and a free surface, we initialise

![]() $\mathcal{N}_{b}+1$

volume-fraction variables

$\mathcal{N}_{b}+1$

volume-fraction variables

![]() $C{ (\boldsymbol{x},t )}\in [0,1]$

, where

$C{ (\boldsymbol{x},t )}\in [0,1]$

, where

![]() $C=0$

for gas/air (inside all bubbles and above the free surface) and

$C=0$

for gas/air (inside all bubbles and above the free surface) and

![]() $1$

for liquid/water. The movement of individual bubbles and the free surface is captured by solving the VOF-advection equation for the corresponding volume-fraction indicator

$1$

for liquid/water. The movement of individual bubbles and the free surface is captured by solving the VOF-advection equation for the corresponding volume-fraction indicator

![]() $C_{i}$

:

$C_{i}$

:

with the subscript

![]() $i$

ranging from

$i$

ranging from

![]() $1$

to

$1$

to

![]() $\mathcal{N}_{b}+1$

. The advection velocity

$\mathcal{N}_{b}+1$

. The advection velocity

![]() $\boldsymbol{u}$

in (2.1) follows from the flow continuity equation

$\boldsymbol{u}$

in (2.1) follows from the flow continuity equation

and the momentum conservation equation

\begin{eqnarray} \rho \left (\frac {\partial \boldsymbol{u}}{\partial t}+\boldsymbol{u}{\boldsymbol{\cdot }}\boldsymbol{\nabla \!}\boldsymbol{u}\right )=-\boldsymbol{\nabla \!}p + \boldsymbol{\nabla }{\boldsymbol{\cdot }}\big [\mu \big (\boldsymbol{\nabla \!}\boldsymbol{u}+\big (\boldsymbol{\nabla \!}\boldsymbol{u}\big )^{\mathrm T}\big )\big ] + \rho \boldsymbol{g}+ \sum \limits ^{\mathcal{N}_{b}+1}_{i=1}\boldsymbol{\mathcal{F}}^{s}_{i}, \end{eqnarray}

\begin{eqnarray} \rho \left (\frac {\partial \boldsymbol{u}}{\partial t}+\boldsymbol{u}{\boldsymbol{\cdot }}\boldsymbol{\nabla \!}\boldsymbol{u}\right )=-\boldsymbol{\nabla \!}p + \boldsymbol{\nabla }{\boldsymbol{\cdot }}\big [\mu \big (\boldsymbol{\nabla \!}\boldsymbol{u}+\big (\boldsymbol{\nabla \!}\boldsymbol{u}\big )^{\mathrm T}\big )\big ] + \rho \boldsymbol{g}+ \sum \limits ^{\mathcal{N}_{b}+1}_{i=1}\boldsymbol{\mathcal{F}}^{s}_{i}, \end{eqnarray}

where

![]() $\rho$

,

$\rho$

,

![]() $\mu$

,

$\mu$

,

![]() $t$

,

$t$

,

![]() $p$

,

$p$

,

![]() $\boldsymbol{g}=\langle 0, g \rangle$

,

$\boldsymbol{g}=\langle 0, g \rangle$

,

![]() $\boldsymbol{\mathcal{F}}^{s}_{i}$

denote the density, dynamic viscosity, time, pressure, vector for the gravitational acceleration (see figure 2) and surface tension force per unit volume, respectively. The continuum surface force model (Brackbill, Kothe & Zemach Reference Brackbill, Kothe and Zemach1992; Popinet Reference Popinet2018) yields

$\boldsymbol{\mathcal{F}}^{s}_{i}$

denote the density, dynamic viscosity, time, pressure, vector for the gravitational acceleration (see figure 2) and surface tension force per unit volume, respectively. The continuum surface force model (Brackbill, Kothe & Zemach Reference Brackbill, Kothe and Zemach1992; Popinet Reference Popinet2018) yields

where

![]() $\sigma$

,

$\sigma$

,

![]() $\kappa$

,

$\kappa$

,

![]() $\delta$

,

$\delta$

,

![]() $\boldsymbol{n}$

represent the surface tension, interface curvature, interface delta function and interface normal, respectively. The fluid density

$\boldsymbol{n}$

represent the surface tension, interface curvature, interface delta function and interface normal, respectively. The fluid density

![]() $\rho$

in (2.3) is calculated using the weighted average,

$\rho$

in (2.3) is calculated using the weighted average,

whereas the dynamic viscosity

![]() $\mu$

follows the harmonic mean (Tryggvason, Scardovelli & Zaleski Reference Tryggvason, Scardovelli and Zaleski2011),

$\mu$

follows the harmonic mean (Tryggvason, Scardovelli & Zaleski Reference Tryggvason, Scardovelli and Zaleski2011),

The subscripts

![]() $l$

and

$l$

and

![]() $g$

correspond to liquid/water and gas/air, respectively. For the problem of floating bubbles, the quantity

$g$

correspond to liquid/water and gas/air, respectively. For the problem of floating bubbles, the quantity

![]() $\chi$

in (2.5)–(2.6) is defined as

$\chi$

in (2.5)–(2.6) is defined as

\begin{eqnarray} \chi =\prod \limits ^{\mathcal{N}_{b}+1}_{i=1}C_{i}. \end{eqnarray}

\begin{eqnarray} \chi =\prod \limits ^{\mathcal{N}_{b}+1}_{i=1}C_{i}. \end{eqnarray}

Essentially,

![]() $\chi$

combines all volume-fraction indicators

$\chi$

combines all volume-fraction indicators

![]() $C_{i}$

into a global phase indicator to compute the correct fluid density and viscosity for the flow field. This procedure couples all

$C_{i}$

into a global phase indicator to compute the correct fluid density and viscosity for the flow field. This procedure couples all

![]() $C_{i}$

and automatically prevents bubble interfaces and the free surface from coalescing when their separation approaches the size of a grid cell.

$C_{i}$

and automatically prevents bubble interfaces and the free surface from coalescing when their separation approaches the size of a grid cell.

We use the open-source finite volume flow solver Basilisk (Popinet & Collaborators Reference Popinet2013–Reference Popinet2024) to incorporate governing equations (2.1)–(2.3) into our numerical simulations. The volume-fraction field

![]() $C_{i}$

in (2.1) is advected using a piecewise-linear geometrical VOF scheme (Scardovelli & Zaleski Reference Scardovelli and Zaleski1999). The interface curvature

$C_{i}$

in (2.1) is advected using a piecewise-linear geometrical VOF scheme (Scardovelli & Zaleski Reference Scardovelli and Zaleski1999). The interface curvature

![]() $\kappa$

needed for the surface tension body force

$\kappa$

needed for the surface tension body force

![]() $\boldsymbol{\mathcal{F}}^{s}$

in (2.4) is determined using the height function method (Popinet Reference Popinet2009). Basilisk’s well-balanced implementation of the surface tension force minimises spurious currents in the simulations (Popinet Reference Popinet2018). For the numerical solution of the flow field, Basilisk relies on the classical time-splitting projection method (Chorin Reference Chorin1969) along with second-order schemes for the spatial gradients. The viscous term in the momentum conservation (2.3) is computed implicitly, while the second-order Bell–Colella–Glaz unsplit upwind scheme (Bell, Colella & Glaz Reference Bell, Colella and Glaz1989) is applied to the nonlinear velocity advection term

$\boldsymbol{\mathcal{F}}^{s}$

in (2.4) is determined using the height function method (Popinet Reference Popinet2009). Basilisk’s well-balanced implementation of the surface tension force minimises spurious currents in the simulations (Popinet Reference Popinet2018). For the numerical solution of the flow field, Basilisk relies on the classical time-splitting projection method (Chorin Reference Chorin1969) along with second-order schemes for the spatial gradients. The viscous term in the momentum conservation (2.3) is computed implicitly, while the second-order Bell–Colella–Glaz unsplit upwind scheme (Bell, Colella & Glaz Reference Bell, Colella and Glaz1989) is applied to the nonlinear velocity advection term

![]() $\boldsymbol{u}{\boldsymbol{\cdot }}\boldsymbol{\nabla \!}\boldsymbol{u}$

(Popinet Reference Popinet2009). All simulations in this study are conducted on dynamic quadtree grids (Popinet Reference Popinet2003, Reference Popinet2009). This is realised using the wavelet-based built-in adaptive mesh refinement functionality within the Basilisk library (van Hooft et al. Reference van Hooft, Popinet, van Heerwaarden, van der Linden, de Roode and van de Wiel2018). The local mesh resolution at each time step is adjusted based on the flow field

$\boldsymbol{u}{\boldsymbol{\cdot }}\boldsymbol{\nabla \!}\boldsymbol{u}$

(Popinet Reference Popinet2009). All simulations in this study are conducted on dynamic quadtree grids (Popinet Reference Popinet2003, Reference Popinet2009). This is realised using the wavelet-based built-in adaptive mesh refinement functionality within the Basilisk library (van Hooft et al. Reference van Hooft, Popinet, van Heerwaarden, van der Linden, de Roode and van de Wiel2018). The local mesh resolution at each time step is adjusted based on the flow field

![]() $\boldsymbol{u}$

, volume-fraction indicator

$\boldsymbol{u}$

, volume-fraction indicator

![]() $C_{i}$

and corresponding interface curvature

$C_{i}$

and corresponding interface curvature

![]() $\kappa$

. A mesh refinement tolerance of

$\kappa$

. A mesh refinement tolerance of

![]() $10^{-4}$

is applied in all cases (see van Hooft et al. (Reference van Hooft, Popinet, van Heerwaarden, van der Linden, de Roode and van de Wiel2018) for more details).

$10^{-4}$

is applied in all cases (see van Hooft et al. (Reference van Hooft, Popinet, van Heerwaarden, van der Linden, de Roode and van de Wiel2018) for more details).

2.2. Computational set-up, code validation and grid convergence study

The effectiveness of the MVOF approach in preventing interface coalescence compared with the traditional VOF implementation is demonstrated qualitatively in Appendix A by simulating the collision of two droplets. To further substantiate our MVOF solver, in this subsection, we simulate an axisymmetric isolated floating bubble using dual volume-fraction fields.

For all subsequent axisymmetric simulations of floating bubbles (including § 3), we set the domain size to

![]() $40R_{0}$

in both the radial (

$40R_{0}$

in both the radial (

![]() $r$

, horizontal) and axial (

$r$

, horizontal) and axial (

![]() $z$

, vertical) directions. Equivalently, we employ a cubic domain of size

$z$

, vertical) directions. Equivalently, we employ a cubic domain of size

![]() $40R_{0}$

for three-dimensional simulations in §§ 4–5. The free surface is initially defined as a horizontal plane positioned at

$40R_{0}$

for three-dimensional simulations in §§ 4–5. The free surface is initially defined as a horizontal plane positioned at

![]() $z=0$

, centred midway through the domain height in the

$z=0$

, centred midway through the domain height in the

![]() $z$

-direction. One or multiple spherical bubbles are placed beneath this free surface and allowed to float and settle into their equilibrium shapes determined by the Bond number

$z$

-direction. One or multiple spherical bubbles are placed beneath this free surface and allowed to float and settle into their equilibrium shapes determined by the Bond number

![]() $\textit{Bo}$

. Unless stated otherwise, the density and viscosity ratios in this study are fixed at

$\textit{Bo}$

. Unless stated otherwise, the density and viscosity ratios in this study are fixed at

![]() $\rho _{l}{/}\rho _{g}=\mu _{l}{/}\mu _{g}=100$

, providing large enough property contrasts to mimic a liquid–gas system similar to water and air (Reichl, Hourigan & Thompson Reference Reichl, Hourigan and Thompson2005; Patel et al. Reference Patel, Sun, Yang and Zhu2025). In axisymmetric cases (including § 3), the free-slip boundary condition is imposed at domain edges corresponding to

$\rho _{l}{/}\rho _{g}=\mu _{l}{/}\mu _{g}=100$

, providing large enough property contrasts to mimic a liquid–gas system similar to water and air (Reichl, Hourigan & Thompson Reference Reichl, Hourigan and Thompson2005; Patel et al. Reference Patel, Sun, Yang and Zhu2025). In axisymmetric cases (including § 3), the free-slip boundary condition is imposed at domain edges corresponding to

![]() $r=40R_{0}$

and

$r=40R_{0}$

and

![]() $z={\pm }20R_{0}$

, and at

$z={\pm }20R_{0}$

, and at

![]() $\{x,y,z\}={\pm }20R_{0}$

for three-dimensional cases in §§ 4–5.

$\{x,y,z\}={\pm }20R_{0}$

for three-dimensional cases in §§ 4–5.

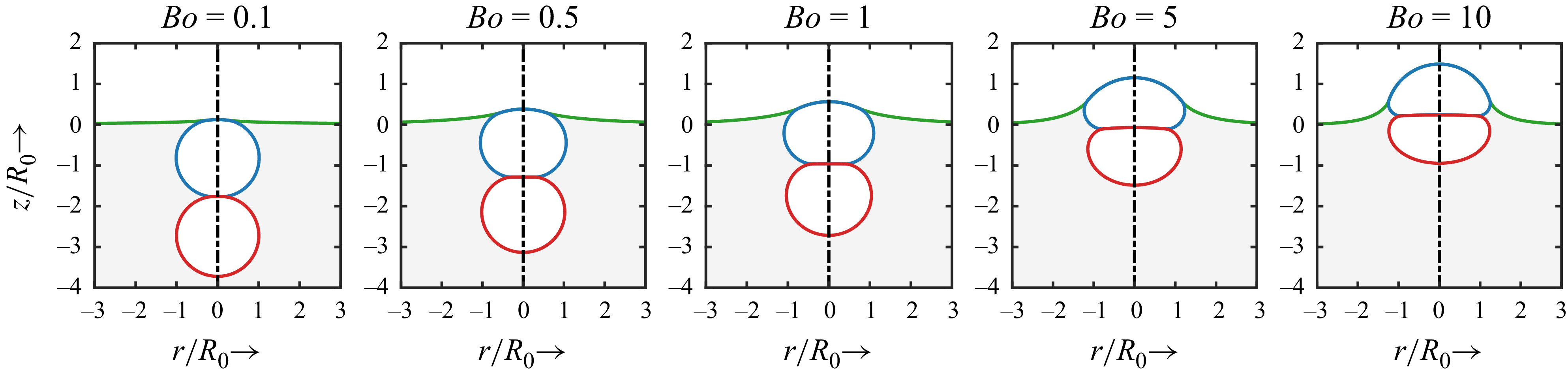

Figure 3 illustrates the equilibrium shapes generated by our MVOF simulations for various Bond (

![]() $\textit{Bo}$

) numbers. As

$\textit{Bo}$

) numbers. As

![]() $\textit{Bo}$

increases, the deformation of the bubble interface and the free surface becomes more noticeable. At a high Bond number of

$\textit{Bo}$

increases, the deformation of the bubble interface and the free surface becomes more noticeable. At a high Bond number of

![]() $\textit{Bo}=100$

, the bubble adopts a hemispherical shape, consistent with experimental observations (Lhuissier & Villermaux Reference Lhuissier and Villermaux2012; Poulain et al. Reference Poulain, Villermaux and Bourouiba2018; Bartlett et al. Reference Bartlett, Oratis, Santin and Bird2023; Shaw & Deike Reference Shaw and Deike2024). Note that the thickness of the spherical cap above the bubble is not resolved in MVOF simulations following the assumption of a weightless liquid film § 2.1. Bubble shapes from MVOF simulations in figure 3 are computed with the highest mesh refinement level of

$\textit{Bo}=100$

, the bubble adopts a hemispherical shape, consistent with experimental observations (Lhuissier & Villermaux Reference Lhuissier and Villermaux2012; Poulain et al. Reference Poulain, Villermaux and Bourouiba2018; Bartlett et al. Reference Bartlett, Oratis, Santin and Bird2023; Shaw & Deike Reference Shaw and Deike2024). Note that the thickness of the spherical cap above the bubble is not resolved in MVOF simulations following the assumption of a weightless liquid film § 2.1. Bubble shapes from MVOF simulations in figure 3 are computed with the highest mesh refinement level of

![]() $\mathcal{L}_{h}=12$

, equivalent to

$\mathcal{L}_{h}=12$

, equivalent to

![]() ${\approx} 102$

uniform grid cells per bubble radius

${\approx} 102$

uniform grid cells per bubble radius

![]() $R_{0}$

, with each cell having a size of

$R_{0}$

, with each cell having a size of

![]() $\varDelta =R_{0}{/}102.4$

.

$\varDelta =R_{0}{/}102.4$

.

Figure 3. Comparison of the steady-state axisymmetric floating bubble shapes obtained using the Young–Laplace (YL) model and MVOF simulations for different Bond (

![]() $\textit{Bo}$

) numbers.

$\textit{Bo}$

) numbers.

We compare our MVOF simulation results with shapes derived from the YL law. The solution procedure, as discussed in Toba (Reference Toba1959) and Lhuissier & Villermaux (Reference Lhuissier and Villermaux2012), involves iteratively solving the balance equations for pressure and surface tension across distinct interfacial regions: the bubble cavity, spherical cap and meniscus (see Appendix B for further details). The interface profiles from both methods, MVOF and YL, exhibit excellent agreement across different Bond numbers, as demonstrated in figure 3. The shape of the spherical cap in the YL model is captured by imposing the appropriate Laplace pressure jump, as outlined in Appendix B. On the other hand, MVOF simulations allow the bubble to press against the free surface by preventing the coalescence (i.e. keeping the bubble interface and the free surface separated), thereby producing the correct deformation of the spherical cap. While the YL model provides an appealing alternative to the MVOF approach for computing bubble shapes, it becomes impractical for scenarios involving two or more floating bubbles, which is the primary focus of our study.

Finally, figure 4 demonstrates that a lower refinement level of

![]() $\mathcal{L}_{h}=11$

also yields accurate results, albeit with minor deviations in the regions highlighted by rectangles. These discrepancies amplify upon further lowering the refinement level (not shown here). The deviation in the interface position at the top of the bubble between MVOF and YL is

$\mathcal{L}_{h}=11$

also yields accurate results, albeit with minor deviations in the regions highlighted by rectangles. These discrepancies amplify upon further lowering the refinement level (not shown here). The deviation in the interface position at the top of the bubble between MVOF and YL is

![]() $2.6\,\%$

at

$2.6\,\%$

at

![]() $\mathcal{L}_{h}=11$

and

$\mathcal{L}_{h}=11$

and

![]() $1.4\,\%$

at

$1.4\,\%$

at

![]() $\mathcal{L}_{h}=12$

, while the interface height between

$\mathcal{L}_{h}=12$

, while the interface height between

![]() $\mathcal{L}_{h}=11$

and

$\mathcal{L}_{h}=11$

and

![]() $\mathcal{L}_{h}=12$

differs by

$\mathcal{L}_{h}=12$

differs by

![]() $1.2\,\%$

relative to

$1.2\,\%$

relative to

![]() $\mathcal{L}_{h}=12$

. Based on these observations, we use an adaptive mesh with

$\mathcal{L}_{h}=12$

. Based on these observations, we use an adaptive mesh with

![]() $\mathcal{L}_{h}=12(\varDelta =R_{0}{/}102.4)$

in our subsequent two-dimensional axisymmetric simulations of coaxial bubbles in § 3, as the interface deformation in these cases is more pronounced than in the single-bubble scenario. For three-dimensional simulations involving bubbles distributed along the free surface in §§ 4–5, we implement a refinement level of

$\mathcal{L}_{h}=12(\varDelta =R_{0}{/}102.4)$

in our subsequent two-dimensional axisymmetric simulations of coaxial bubbles in § 3, as the interface deformation in these cases is more pronounced than in the single-bubble scenario. For three-dimensional simulations involving bubbles distributed along the free surface in §§ 4–5, we implement a refinement level of

![]() $\mathcal{L}_{h}=11(\varDelta =R_{0}{/}51.2)$

.

$\mathcal{L}_{h}=11(\varDelta =R_{0}{/}51.2)$

.

Figure 4. Axisymmetric floating bubble shapes obtained from MVOF simulations using different mesh resolutions and their comparison with the shape derived from the YL equations for a Bond number

![]() $\textit{Bo}=100$

.

$\textit{Bo}=100$

.

3. Geometry of axisymmetric coaxial floating bubbles

3.1. Numerical findings

Figure 5 presents a series of bubble shapes obtained through axisymmetric MVOF simulations, spanning a wide range of Bond numbers across two decades. In the surface-tension-dominated regime (

![]() $\textit{Bo}\lt 1$

), interface deformation remains minimal, with bubbles retaining an almost perfect spherical shape and showing only slight perturbations in the contact region of two bubbles and at the free surface. This behaviour is consistent with the case of an isolated floating bubble shown in figure 3 at

$\textit{Bo}\lt 1$

), interface deformation remains minimal, with bubbles retaining an almost perfect spherical shape and showing only slight perturbations in the contact region of two bubbles and at the free surface. This behaviour is consistent with the case of an isolated floating bubble shown in figure 3 at

![]() $\textit{Bo}=0.5$

. As the Bond number increases beyond

$\textit{Bo}=0.5$

. As the Bond number increases beyond

![]() $\textit{Bo}=1$

, gravitational forces dominate, leading to pronounced interface deformations. At

$\textit{Bo}=1$

, gravitational forces dominate, leading to pronounced interface deformations. At

![]() $\textit{Bo}=5$

and

$\textit{Bo}=5$

and

![]() $\textit{Bo}=10$

, the bottom red-coloured bubble starts pressing against the top blue-coloured bubble, adopting an oblate shape. The introduction of an additional bubble in the current case produces significant deformation of the free surface and the top bubble compared with cases involving isolated bubbles, even at relatively low

$\textit{Bo}=10$

, the bottom red-coloured bubble starts pressing against the top blue-coloured bubble, adopting an oblate shape. The introduction of an additional bubble in the current case produces significant deformation of the free surface and the top bubble compared with cases involving isolated bubbles, even at relatively low

![]() $\textit{Bo}$

values. We can already notice the hemispherical shape of the top bubble at

$\textit{Bo}$

values. We can already notice the hemispherical shape of the top bubble at

![]() $\textit{Bo}=10$

in figure 5, which was previously observed for an isolated bubble at a 10 times larger Bond number of

$\textit{Bo}=10$

in figure 5, which was previously observed for an isolated bubble at a 10 times larger Bond number of

![]() $\textit{Bo}=100$

in figure 3.

$\textit{Bo}=100$

in figure 3.

Figure 5. Equilibrium shapes of axisymmetric floating bubble pairs at various Bond (

![]() $\textit{Bo}$

) numbers. Interface profiles captured with different volume-fraction indicators are shown in distinct colours.

$\textit{Bo}$

) numbers. Interface profiles captured with different volume-fraction indicators are shown in distinct colours.

Previous studies (Georgescu, Achard & Canot Reference Georgescu, Achard and Canot2002; Walls et al. Reference Walls, Henaux and Bird2015) on isolated floating air bubbles in water identified a critical Bond number of

![]() $\textit{Bo}^{\star }=\rho _{l}gR^{2}_{c}/\sigma \approx 3$

based on the radius of the spherical cap

$\textit{Bo}^{\star }=\rho _{l}gR^{2}_{c}/\sigma \approx 3$

based on the radius of the spherical cap

![]() $R_{c}$

(see figure 6 for the definition of

$R_{c}$

(see figure 6 for the definition of

![]() $R_{c}$

), marking the onset of transition from the production jet to film droplets during bubble bursting. No jet droplets are generated once the critical Bond number

$R_{c}$

), marking the onset of transition from the production jet to film droplets during bubble bursting. No jet droplets are generated once the critical Bond number

![]() $\textit{Bo}^{\star }$

is reached (corresponding to

$\textit{Bo}^{\star }$

is reached (corresponding to

![]() $R_{c}\approx 4.2\, \rm { mm}$

for the air–water combination) due to the dominant effects of gravitational forces (Georgescu et al. Reference Georgescu, Achard and Canot2002; Walls et al. Reference Walls, Henaux and Bird2015). However, the formation of Worthington (or Rayleigh) jets persists (Krishnan et al. Reference Krishnan, Hopfinger and Puthenveettil2017). For bubbles with

$R_{c}\approx 4.2\, \rm { mm}$

for the air–water combination) due to the dominant effects of gravitational forces (Georgescu et al. Reference Georgescu, Achard and Canot2002; Walls et al. Reference Walls, Henaux and Bird2015). However, the formation of Worthington (or Rayleigh) jets persists (Krishnan et al. Reference Krishnan, Hopfinger and Puthenveettil2017). For bubbles with

![]() $\rho _{l}gR^{2}_{c}/\sigma \gt \textit{Bo}^{\star }$

, the size of the spherical cap at the top of the bubble strongly influences the bursting process.

$\rho _{l}gR^{2}_{c}/\sigma \gt \textit{Bo}^{\star }$

, the size of the spherical cap at the top of the bubble strongly influences the bursting process.

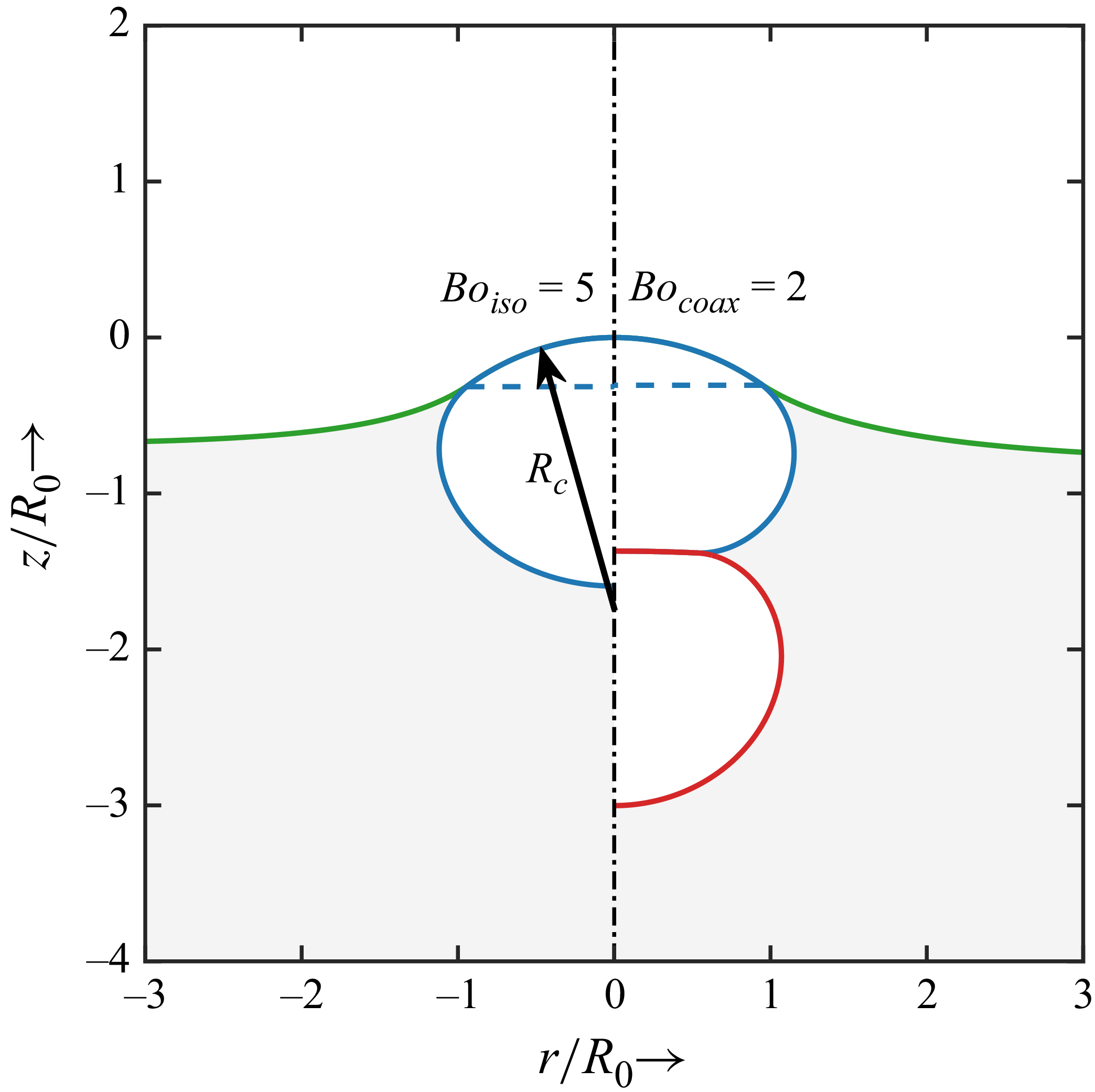

Figure 6. Comparison of axisymmetric equilibrium shapes: an isolated floating bubble at

![]() $\textit{Bo}_{\textit{iso}}=5$

(

$\textit{Bo}_{\textit{iso}}=5$

(

![]() $\rho _{l}gR^{2}_{c}/\sigma =3.8$

) versus a pair of coaxial floating bubbles at

$\rho _{l}gR^{2}_{c}/\sigma =3.8$

) versus a pair of coaxial floating bubbles at

![]() $\textit{Bo}_{\textit{coax}}=2$

. Here,

$\textit{Bo}_{\textit{coax}}=2$

. Here,

![]() $R_{c}$

denotes the radius of the spherical cap.

$R_{c}$

denotes the radius of the spherical cap.

Figure 6 compares an isolated floating bubble at

![]() $\textit{Bo}_{\textit{iso}}=5$

(equivalently

$\textit{Bo}_{\textit{iso}}=5$

(equivalently

![]() $\rho _{l}gR^{2}_{c}/\sigma =3.8$

, slightly larger than

$\rho _{l}gR^{2}_{c}/\sigma =3.8$

, slightly larger than

![]() $\textit{Bo}^{\star }$

) with a pair of coaxial floating bubbles at

$\textit{Bo}^{\star }$

) with a pair of coaxial floating bubbles at

![]() $\textit{Bo}_{\textit{coax}}=2$

. Interestingly, both configurations exhibit spherical caps with nearly identical shapes (see the region above the dashed blue line in figure 6). This similarity suggests the possibility of an early onset of the transition from jet to film droplets at a Bond number as low as

$\textit{Bo}_{\textit{coax}}=2$

. Interestingly, both configurations exhibit spherical caps with nearly identical shapes (see the region above the dashed blue line in figure 6). This similarity suggests the possibility of an early onset of the transition from jet to film droplets at a Bond number as low as

![]() $\textit{Bo}_{\textit{coax}}=2$

for a pair of coaxial floating bubbles (

$\textit{Bo}_{\textit{coax}}=2$

for a pair of coaxial floating bubbles (

![]() ${\approx} 36\,\%$

smaller bubble sizes), as the size of the spherical cap already exceeds the critical threshold. Prior experimental studies (Lhuissier & Villermaux Reference Lhuissier and Villermaux2012; Poulain et al. Reference Poulain, Villermaux and Bourouiba2018; Shaw & Deike Reference Shaw and Deike2024) have shown that the rupture of large, dome-shaped spherical caps, like that shown in figure 3 at

${\approx} 36\,\%$

smaller bubble sizes), as the size of the spherical cap already exceeds the critical threshold. Prior experimental studies (Lhuissier & Villermaux Reference Lhuissier and Villermaux2012; Poulain et al. Reference Poulain, Villermaux and Bourouiba2018; Shaw & Deike Reference Shaw and Deike2024) have shown that the rupture of large, dome-shaped spherical caps, like that shown in figure 3 at

![]() $\textit{Bo}=100$

, generates film droplets. Given this, for a floating bubble pair at

$\textit{Bo}=100$

, generates film droplets. Given this, for a floating bubble pair at

![]() $\textit{Bo}=10$

in figure 5 with a similarly shaped spherical cap, the atomisation of the spherical cap can generate spray droplets in quantities comparable to those produced by the burst of a much larger isolated floating bubble with

$\textit{Bo}=10$

in figure 5 with a similarly shaped spherical cap, the atomisation of the spherical cap can generate spray droplets in quantities comparable to those produced by the burst of a much larger isolated floating bubble with

![]() $\textit{Bo}=100$

.

$\textit{Bo}=100$

.

To further our discussion, we analyse various geometrical parameters of both an isolated bubble and a pair of floating bubbles. First, we examine the variations in cap height

![]() $h_{c}$

, rim radius

$h_{c}$

, rim radius

![]() $R_{r}$

, bubble position along the axis

$R_{r}$

, bubble position along the axis

![]() $Z_{b}$

and the bubble aspect ratio

$Z_{b}$

and the bubble aspect ratio

![]() $\Delta r/\Delta z$

, as shown in figures 7 and 8. Two schematics illustrating these geometrical parameters are provided in figure 7(a) for an isolated bubble and figure 8(a) for a bubble pair. Measuring different geometrical features is crucial because they are key to various scaling relations that describe dynamic processes tied to bursting bubbles (Puthenveettil et al. Reference Puthenveettil, Saha, Krishnan and Hopfinger2018). For example, the cap height and rim radius are needed to calculate the surface area of the spherical cap, which helps estimate the drainage time of the liquid within the spherical cap. Conversely, comparing the bubble position

$\Delta r/\Delta z$

, as shown in figures 7 and 8. Two schematics illustrating these geometrical parameters are provided in figure 7(a) for an isolated bubble and figure 8(a) for a bubble pair. Measuring different geometrical features is crucial because they are key to various scaling relations that describe dynamic processes tied to bursting bubbles (Puthenveettil et al. Reference Puthenveettil, Saha, Krishnan and Hopfinger2018). For example, the cap height and rim radius are needed to calculate the surface area of the spherical cap, which helps estimate the drainage time of the liquid within the spherical cap. Conversely, comparing the bubble position

![]() $Z_{b}$

and aspect ratio

$Z_{b}$

and aspect ratio

![]() $\Delta r/\Delta z$

in figures 7 and 8 enables a more direct measurement of shape changes caused by the additional buoyancy force from the second bubble in a bubble pair.

$\Delta r/\Delta z$

in figures 7 and 8 enables a more direct measurement of shape changes caused by the additional buoyancy force from the second bubble in a bubble pair.

Figure 7. Effect of the Bond number

![]() $\textit{Bo}$

on various equilibrium shape parameters of axisymmetric isolated floating bubbles: (a) cap height,

$\textit{Bo}$

on various equilibrium shape parameters of axisymmetric isolated floating bubbles: (a) cap height,

![]() $h_{c}/R_{0}$

; (b) rim radius of the spherical cap,

$h_{c}/R_{0}$

; (b) rim radius of the spherical cap,

![]() $R_{r}/R_{0}$

; (c) axial location of the bubble,

$R_{r}/R_{0}$

; (c) axial location of the bubble,

![]() $Z_{b}/R_{0}$

; and (d) bubble aspect ratio,

$Z_{b}/R_{0}$

; and (d) bubble aspect ratio,

![]() $\Delta r/\Delta z$

. All shape parameters are illustrated in the inset of (a). Insets in (d) compare equilibrium bubble shapes obtained using the YL model (left) and MVOF simulations (right). Experimental data in (a) and (b) are from Puthenveettil et al. (Reference Puthenveettil, Saha, Krishnan and Hopfinger2018). Note that the origin

$\Delta r/\Delta z$

. All shape parameters are illustrated in the inset of (a). Insets in (d) compare equilibrium bubble shapes obtained using the YL model (left) and MVOF simulations (right). Experimental data in (a) and (b) are from Puthenveettil et al. (Reference Puthenveettil, Saha, Krishnan and Hopfinger2018). Note that the origin

![]() $z=0$

for axial measurements is defined at the unperturbed free surface. The legends in (b) apply to all plots.

$z=0$

for axial measurements is defined at the unperturbed free surface. The legends in (b) apply to all plots.

Figure 8. Effect of the Bond number

![]() $\textit{Bo}$

on various equilibrium shape parameters of a pair of coaxial floating bubbles: (a) cap height,

$\textit{Bo}$

on various equilibrium shape parameters of a pair of coaxial floating bubbles: (a) cap height,

![]() $h_{c}/R_{0}$

; (b) rim radius of the spherical cap (blue circles) and the film in the contact region of two bubbles (red circles),

$h_{c}/R_{0}$

; (b) rim radius of the spherical cap (blue circles) and the film in the contact region of two bubbles (red circles),

![]() $R_{r}/R_{0}$

; (c) axial location of the top (blue circles) and bottom (red circles) bubbles,

$R_{r}/R_{0}$

; (c) axial location of the top (blue circles) and bottom (red circles) bubbles,

![]() $Z_{b}/R_{0}$

; and (d) aspect ratios of the top (blue circles) and bottom (red circles) bubbles,

$Z_{b}/R_{0}$

; and (d) aspect ratios of the top (blue circles) and bottom (red circles) bubbles,

![]() $\Delta r/\Delta z$

. All shape parameters are illustrated in the inset of (a). Note that the origin

$\Delta r/\Delta z$

. All shape parameters are illustrated in the inset of (a). Note that the origin

![]() $z=0$

for axial measurements is defined at the unperturbed free surface.

$z=0$

for axial measurements is defined at the unperturbed free surface.

For an isolated bubble, the cap height

![]() $h_{c}$

in figure 7(a) increases with the Bond number

$h_{c}$

in figure 7(a) increases with the Bond number

![]() $\textit{Bo}$

and reaches a plateau at a value approximately equal to the bubble radius

$\textit{Bo}$

and reaches a plateau at a value approximately equal to the bubble radius

![]() ${\approx} R_{0}$

for

${\approx} R_{0}$

for

![]() $\textit{Bo}\gt 10$

. The present YL and MVOF solutions show good agreement with the experimental results of Puthenveettil et al. (Reference Puthenveettil, Saha, Krishnan and Hopfinger2018). In contrast to isolated bubbles, a pair of bubbles in figure 8(a) exhibits a distinct trend in cap height variation. For

$\textit{Bo}\gt 10$

. The present YL and MVOF solutions show good agreement with the experimental results of Puthenveettil et al. (Reference Puthenveettil, Saha, Krishnan and Hopfinger2018). In contrast to isolated bubbles, a pair of bubbles in figure 8(a) exhibits a distinct trend in cap height variation. For

![]() $\textit{Bo}\lt 1$

,

$\textit{Bo}\lt 1$

,

![]() $h_{c}$

increases more rapidly than in the single-bubble case, after which a sharp transition occurs at

$h_{c}$

increases more rapidly than in the single-bubble case, after which a sharp transition occurs at

![]() $\textit{Bo}=1$

, characterised by a subdued growth of

$\textit{Bo}=1$

, characterised by a subdued growth of

![]() $h_{c}$

for

$h_{c}$

for

![]() $\textit{Bo}\gt 1$

. The slower rise in cap height for bubble pairs with

$\textit{Bo}\gt 1$

. The slower rise in cap height for bubble pairs with

![]() $\textit{Bo}\gt 1$

, relative to

$\textit{Bo}\gt 1$

, relative to

![]() $\textit{Bo}\lt 1$

, is due to part of the work done by buoyancy contributing to the radial expansion of the upper bubble. This effect is evident through the oblate bubble shapes observed in figure 5 at

$\textit{Bo}\lt 1$

, is due to part of the work done by buoyancy contributing to the radial expansion of the upper bubble. This effect is evident through the oblate bubble shapes observed in figure 5 at

![]() $\textit{Bo}=5$

and

$\textit{Bo}=5$

and

![]() $10$

. Notably, at

$10$

. Notably, at

![]() $\textit{Bo}=10$

, the dimensionless cap height

$\textit{Bo}=10$

, the dimensionless cap height

![]() $h_{c}/R_{0}$

of a bubble pair already surpasses that of an isolated bubble at

$h_{c}/R_{0}$

of a bubble pair already surpasses that of an isolated bubble at

![]() $\textit{Bo}=100$

.

$\textit{Bo}=100$

.

Figures 7(b) and 8(b) show the trends in the rim radius

![]() $R_{r}$

. For a bubble floating near the free surface,

$R_{r}$

. For a bubble floating near the free surface,

![]() $R_{r}$

denotes the radial distance from the axis to the contact point where the spherical cap, meniscus and bubble cavity meet. In the case of bubble pairs, an additional rim radius is defined to account for the size of the contact area between the top and bottom bubbles. In practice, this contact region contains a thin liquid film that is not resolved in the simulations. For isolated floating bubbles, the qualitative variation of

$R_{r}$

denotes the radial distance from the axis to the contact point where the spherical cap, meniscus and bubble cavity meet. In the case of bubble pairs, an additional rim radius is defined to account for the size of the contact area between the top and bottom bubbles. In practice, this contact region contains a thin liquid film that is not resolved in the simulations. For isolated floating bubbles, the qualitative variation of

![]() $R_{r}$

in figure 7(b) resembles the cap height

$R_{r}$

in figure 7(b) resembles the cap height

![]() $h_{c}$

in figure 7(a). The rim radius

$h_{c}$

in figure 7(a). The rim radius

![]() $R_{r}$

converges towards the theoretical upper bound of

$R_{r}$

converges towards the theoretical upper bound of

![]() $2^{1/3}R_{0}$

as isolated bubbles approach a hemispherical shape for

$2^{1/3}R_{0}$

as isolated bubbles approach a hemispherical shape for

![]() $\textit{Bo}$

exceeding

$\textit{Bo}$

exceeding

![]() $10$

(see figure 3 and the bottom inset of figure 7

d). As before, our results in figure 7(b) are in excellent agreement with the experimental observations of Puthenveettil et al. (Reference Puthenveettil, Saha, Krishnan and Hopfinger2018). For bubble pairs in figure 8(b), the rim radius

$10$

(see figure 3 and the bottom inset of figure 7

d). As before, our results in figure 7(b) are in excellent agreement with the experimental observations of Puthenveettil et al. (Reference Puthenveettil, Saha, Krishnan and Hopfinger2018). For bubble pairs in figure 8(b), the rim radius

![]() $R_{r}$

of the spherical cap exceeds that of the single-bubble counterpart at a given

$R_{r}$

of the spherical cap exceeds that of the single-bubble counterpart at a given

![]() $\textit{Bo}$

, but in the limit

$\textit{Bo}$

, but in the limit

![]() $\textit{Bo}\rightarrow 10$

it asymptotically approaches the same upper bound of

$\textit{Bo}\rightarrow 10$

it asymptotically approaches the same upper bound of

![]() $2^{1/3}R_{0}$

as isolated bubbles. With increasing

$2^{1/3}R_{0}$

as isolated bubbles. With increasing

![]() $\textit{Bo}$

, the top and bottom bubbles in a pair spread against each other, forming a contact region with a radius

$\textit{Bo}$

, the top and bottom bubbles in a pair spread against each other, forming a contact region with a radius

![]() $R_{r}$

nearly as large as

$R_{r}$

nearly as large as

![]() $R_{0}$

at

$R_{0}$

at

![]() $\textit{Bo}=10$

. Our results in figure 8(a,b) demonstrate that the presence of an additional bubble substantially modifies both the cap height

$\textit{Bo}=10$

. Our results in figure 8(a,b) demonstrate that the presence of an additional bubble substantially modifies both the cap height

![]() $h_{c}$

and the rim radius

$h_{c}$

and the rim radius

![]() $R_{r}$

, and thereby the surface area of the spherical cap. The cap area of single and coaxial bubbles will be examined in detail later in this subsection.

$R_{r}$

, and thereby the surface area of the spherical cap. The cap area of single and coaxial bubbles will be examined in detail later in this subsection.

We point out that the saturation

![]() $R_{r}/R_{0}=2^{1/3}$

for the upper bubble in a floating pair (figure 8

b) may not persist in the limit

$R_{r}/R_{0}=2^{1/3}$

for the upper bubble in a floating pair (figure 8

b) may not persist in the limit

![]() $\textit{Bo}\rightarrow \infty$

. At sufficiently large Bond numbers, both bubbles can rise above the undisturbed free surface and form a larger spherical cap of volume

$\textit{Bo}\rightarrow \infty$

. At sufficiently large Bond numbers, both bubbles can rise above the undisturbed free surface and form a larger spherical cap of volume

![]() $8\pi R^{3}_{0}/3$

, representing the energetically favourable configuration. This state would instead yield

$8\pi R^{3}_{0}/3$

, representing the energetically favourable configuration. This state would instead yield

![]() $R_{r}/R_{0}=4^{1/3}$

. Probing the asymptotic regime to verify this hypothesis would require simulations extending to much higher Bond numbers, together with finer grid resolution to accurately resolve the resulting interface curvature, and is therefore left for future investigation.

$R_{r}/R_{0}=4^{1/3}$

. Probing the asymptotic regime to verify this hypothesis would require simulations extending to much higher Bond numbers, together with finer grid resolution to accurately resolve the resulting interface curvature, and is therefore left for future investigation.

Figure 7(c,d) illustrates the bubble’s position

![]() $Z_{b}/R_{0}$

along the axis and its aspect ratio

$Z_{b}/R_{0}$

along the axis and its aspect ratio

![]() $\Delta r/\Delta z$

for isolated bubbles. At low Bond numbers (

$\Delta r/\Delta z$

for isolated bubbles. At low Bond numbers (

![]() $\textit{Bo}\lt 1$

), the position of an isolated bubble shows a slow rise with

$\textit{Bo}\lt 1$

), the position of an isolated bubble shows a slow rise with

![]() $\textit{Bo}$

due to dominant surface tension forces that resist its ascent against the free surface. As the Bond number increases (

$\textit{Bo}$

due to dominant surface tension forces that resist its ascent against the free surface. As the Bond number increases (

![]() $1\leqslant \textit{Bo}\leqslant 10$

), the deformation of the free surface, caused by the bubble’s buoyancy, allows the bubble to reach a higher elevation. Notably, at

$1\leqslant \textit{Bo}\leqslant 10$

), the deformation of the free surface, caused by the bubble’s buoyancy, allows the bubble to reach a higher elevation. Notably, at

![]() $\textit{Bo}=7$

, the bubble centre surpasses the unperturbed free-surface level corresponding to

$\textit{Bo}=7$

, the bubble centre surpasses the unperturbed free-surface level corresponding to

![]() $z=0$

, marking the transition from subsurface floating bubbles immersed mainly within the liquid to those significantly exposed to the outer gas phase. At the largest Bond number of

$z=0$

, marking the transition from subsurface floating bubbles immersed mainly within the liquid to those significantly exposed to the outer gas phase. At the largest Bond number of

![]() $\textit{Bo}=100$

, the bubble centre is positioned

$\textit{Bo}=100$

, the bubble centre is positioned

![]() $0.5R_{0}$

above the free surface. The variation in aspect ratio

$0.5R_{0}$

above the free surface. The variation in aspect ratio

![]() $\Delta r/\Delta z$

shown in figure 7(d) also follows a trend similar to

$\Delta r/\Delta z$

shown in figure 7(d) also follows a trend similar to

![]() $Z_{b}/R_{0}$

in figure 7(c). Between

$Z_{b}/R_{0}$

in figure 7(c). Between

![]() $\textit{Bo}=1$

and

$\textit{Bo}=1$

and

![]() $10$

, the bubble undergoes significant elongation. However, for Bond numbers below unity or beyond

$10$

, the bubble undergoes significant elongation. However, for Bond numbers below unity or beyond

![]() $10$

, changes in aspect ratio become relatively marginal, forming two plateau branches that connect the

$10$

, changes in aspect ratio become relatively marginal, forming two plateau branches that connect the

![]() $1\leqslant \textit{Bo}\leqslant 10$

transition range in the middle. The aspect ratio of an isolated bubble peaks at a value of

$1\leqslant \textit{Bo}\leqslant 10$

transition range in the middle. The aspect ratio of an isolated bubble peaks at a value of

![]() $1.8$

, corresponding to highly stretched, hemisphere-like floating bubbles (see bubble shapes in figure 3 and the bottom inset of figure 7

d).

$1.8$

, corresponding to highly stretched, hemisphere-like floating bubbles (see bubble shapes in figure 3 and the bottom inset of figure 7

d).

We now compare position

![]() $Z_{b}/R_{0}$

and aspect ratio

$Z_{b}/R_{0}$

and aspect ratio

![]() $\Delta r/\Delta z$

of isolated bubbles with our observations of a pair of floating bubbles in figure 8(c,d). The centre position

$\Delta r/\Delta z$

of isolated bubbles with our observations of a pair of floating bubbles in figure 8(c,d). The centre position

![]() $Z_{b}/R_{0}$

of the top bubble in figure 8(c) rises significantly faster with increasing

$Z_{b}/R_{0}$

of the top bubble in figure 8(c) rises significantly faster with increasing

![]() $\textit{Bo}$

compared with an isolated bubble. This is attributed to the additional buoyancy force exerted by the bottom bubble in a floating pair. Notably, the centre of the top bubble in a pair reaches the free surface at a relatively low Bond number of

$\textit{Bo}$

compared with an isolated bubble. This is attributed to the additional buoyancy force exerted by the bottom bubble in a floating pair. Notably, the centre of the top bubble in a pair reaches the free surface at a relatively low Bond number of

![]() $\textit{Bo}=2$

, which is approximately one-third of the Bond number required for an isolated bubble. For

$\textit{Bo}=2$

, which is approximately one-third of the Bond number required for an isolated bubble. For

![]() $\textit{Bo}\gt 2$

,

$\textit{Bo}\gt 2$

,

![]() $Z_{b}/R_{0}$

continues to increase and reaches a value as large as

$Z_{b}/R_{0}$

continues to increase and reaches a value as large as

![]() $R_{0}$

at

$R_{0}$

at

![]() $\textit{Bo}=10$

(see the corresponding bubble shape in figure 5), nearly twice the maximum centre height observed for an isolated bubble at

$\textit{Bo}=10$

(see the corresponding bubble shape in figure 5), nearly twice the maximum centre height observed for an isolated bubble at

![]() $\textit{Bo}=100$

in figure 7(c). In such cases, where the top bubble penetrates significantly into the gas phase, the stability of the spherical cap may become susceptible to perturbations arising from the external flow within the gas phase (e.g. wind near the free surface in the ocean). This could, in turn, affect the dynamics of the bursting process. The bottom bubble in a floating pair also rises towards the free surface due to buoyancy as

$\textit{Bo}=100$

in figure 7(c). In such cases, where the top bubble penetrates significantly into the gas phase, the stability of the spherical cap may become susceptible to perturbations arising from the external flow within the gas phase (e.g. wind near the free surface in the ocean). This could, in turn, affect the dynamics of the bursting process. The bottom bubble in a floating pair also rises towards the free surface due to buoyancy as

![]() $\textit{Bo}$

increases.

$\textit{Bo}$

increases.

The centre position

![]() $Z_{b}/R_{0}$

of the bottom bubble rises at a relatively faster rate with

$Z_{b}/R_{0}$

of the bottom bubble rises at a relatively faster rate with

![]() $\textit{Bo}$

than that of the top bubble, particularly in the range

$\textit{Bo}$

than that of the top bubble, particularly in the range

![]() $1\leqslant \textit{Bo}\leqslant 10$

. This behaviour can be explained by the variation in the bubble aspect ratio

$1\leqslant \textit{Bo}\leqslant 10$

. This behaviour can be explained by the variation in the bubble aspect ratio

![]() $\Delta r/\Delta z$

. Since the bottom bubble resides at greater depth, it can sustain larger meridional curvatures, compensating for reduced azimuthal curvature from radial elongation and thereby maintaining the Laplace pressure balance. On the other hand, at higher Bond numbers, free-surface deformation reduces the radial surface-tension force at the contact line and enhances the vertical component, which counteracts the net buoyancy force acting on the top bubble. Following this,

$\Delta r/\Delta z$