Much of the literature on democratization focuses on structural variables, such as the level of economic development, institutions, geography, and culture. This literature has generated important insights that help explain some crucial aspects of the first wave of democratization in South America. Nevertheless, many structural theories, such as modernization theory, do not provide a very comprehensive or thick explanation of the emergence of democracy in the region. Although structural variables may explain cross-national variation in democracy, they cannot typically explain the precise timing of democratization because structural variables usually change only slowly over time. Moreover, structural approaches often do not indicate who the key actors in the democratization process were, why they supported or opposed democratization, and how advocates of democracy managed to prevail.Footnote 1

By contrast, this book develops a thick explanation for the origins of democracy in South America that not only identifies the key actors in the struggle for democracy and explains their preferences but also specifies the structures that constrain or empower them. It aims to illuminate the process of democratization, explaining why and how supporters of democracy prevailed over its opponents. I focus on two main actors – political parties and the military – and show how they shaped regime outcomes in ten South American countries from independence until 1929. I also explain what led to the emergence of strong militaries and parties in some countries of the region.

This chapter is structured as follows. The first section examines the role of the military in democratization. It suggests that the professionalization of the military in South America helped facilitate democracy by bringing an end to the widespread revolts that plagued the region in the nineteenth century. The second section discusses the causes of military professionalization, focusing on the export boom of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century and regional military conflict and competition. The third section explains why opposition parties typically support democratic reforms and ruling parties oppose them. It argues that the existence of strong opposition parties and splits within the ruling party helped bring about democracy in South America by providing the votes necessary to enact democratic reforms. The fourth section analyzes why strong parties emerged in some countries and not others, focusing on two main variables: the geographic concentration of the population and the existence of relatively balanced religious or territorial cleavages. The fifth section summarizes how the different explanatory variables interacted to produce regime outcomes in South America during the early twentieth century. The final section discusses some existing theories of democracy and shows that, while they contribute some important insights, they do not provide a comprehensive explanation of the first wave of democratization in South America.

The Military and the Emergence of Democracy

As the Introduction noted, many scholars have viewed the military as an impediment to democracy, especially in Latin America where the armed forces have frequently overthrown democratic governments and engaged in repressive practices that have violated the basic rights of the citizenry. Nevertheless, as we shall see, the military played a constructive role in the first wave of democratization in South America, helping to bring an end to the opposition revolts that had destabilized the region during the nineteenth century. After South American governments strengthened and professionalized their militaries, the opposition in these countries largely abandoned the armed struggle and began to concentrate on the electoral path to power.

Weber (Reference Weber, Gerth and Mills1946, 78, emphasis in original) claims that states must successfully claim a “monopoly of the legitimate use of physical force within a given territory,” but he does not address what impact the absence of such a monopoly means for democratic rule. This study argues that the failure of states to achieve a monopoly on violence will typically have deleterious effects on their prospects for democracy by encouraging the opposition to carry out armed revolts. I do not claim that a state monopoly on violence is a prerequisite for democracy since some democracies have arisen in the midst of serious challenges to the state’s monopoly on violence and a few have even survived civil wars (Mazzuca and Munck Reference Mazzuca and Munck2014). Nevertheless, as the South American experience illustrates, a state monopoly on violence can dramatically improve a country’s prospects for democracy by persuading the opposition to focus on the electoral path to power.Footnote 2

Much of the democratization literature has suggested that democracy arises as a mechanism to settle conflicts – the government provides the opposition with a share of power (or a chance to win it) and the opposition, in turn, refrains from revolting (Dahl Reference Dahl1971; Acemoglu and Robinson Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2006; Mazzuca and Munck Reference Mazzuca and Munck2014, 1224–1225; Przeworski Reference Przeworski2011; Przeworski, Rivero, and Xi Reference Przeworski, Rivero and Xi2015; Rustow Reference Rustow1970, 354–355). From this perspective, democracy is facilitated by military weakness: It emerges when the government concludes that it cannot suppress the opposition or that the costs of doing so are too high. Rustow (Reference Rustow1970, 352), for example, contends that “the dynamic process of democratization is set off by a prolonged and inconclusive political struggle.” Similarly, in Polyarchy, Dahl (Reference Dahl1971, 49) postulates that “the likelihood that a government will tolerate an opposition increases with a reduction in the capacity of the government to use violence or socioeconomic sanctions to suppress an opposition.” He goes on to suggest that democracy arose in Chile, New Zealand, Norway, and Switzerland in part because the geographies of these countries made it impossible for the state to achieve a monopoly on violence (Dahl Reference Dahl1971, 56). The class pressure model discussed in this chapter also rests on the assumption of state military weakness – it contends that the governing elites agree to democratize in order to prevent the masses from overthrowing them by force (Acemoglu and Robinson Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2006; Aidt and Franck Reference Aidt and Franck2015; 2014; Boix Reference Boix2003). According to Acemoglu and Robinson (Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2006, 25), for a real threat from the masses to exist, “the elites – who are controlling the state apparatus – should be unable to use the military to effectively suppress the uprising.”

Nevertheless, there is little evidence to suggest that democracy in South America emerged from military weakness or declining government capacity to suppress the masses or the opposition. South American militaries were weak during the nineteenth century and had a difficult time suppressing revolts, but democracy did not arise until the early twentieth century after many of the region’s armed forces professionalized and gained a monopoly on violence. Democracy in South America thus emerged not when the government’s capacity to suppress the opposition declined but rather when it increased. Moreover, the countries that democratized first in South America had some of the strongest militaries in the region and the greatest ability to suppress the opposition.Footnote 3 In three of these countries – Argentina, Colombia, and Uruguay – democracy arose during a period in which the opposition was demobilized after its resounding military defeat. In Chile, democracy emerged in the wake of a momentous opposition victory in a civil war in which the navy sided with the rebellious parliamentary opposition. In none of the four democratizing countries was there an ongoing armed conflict at the time of democratization; nor was there a high likelihood that the opposition would rebel in the near future.Footnote 4 To the contrary, in all four countries, the government had a clear monopoly on violence when it democratized.

Why would military dominance, rather than military weakness, lead to democratization? The answer to this question has to do with the impact of revolts on the prospects for democracy. As the civil war literature has shown, state weakness, especially low coercive capacity, will tend to foster revolts (Fearon Reference Fearon2010; Fearon and Laitin Reference Fearon and Laitin2003; Hendrix Reference Hendrix2010; Cederman and Vogt 1997; 2017). Where the state cannot easily suppress revolts, the opposition has an incentive to engage in them. The opposition may carry out these revolts because it believes it can overthrow the government or because it hopes to win concessions. In authoritarian regimes, these revolts may represent the opposition’s best chance of gaining power and influence, given the regimes’ control of the electoral process. Indeed, in the past 200 years, power worldwide has changed hands much more frequently through force than through elections (Przeworski, Rivero, and Xi Reference Przeworski, Rivero and Xi2015, 235).

Armed revolts, however, typically deepen authoritarian rule, undermining the prospects for democracy. Governments usually respond to such revolts with state repression, clamping down on the media, restricting civil and political liberties, and arresting, exiling, and even killing members of the opposition. These repressive measures often engender further revolts, thereby creating a vicious cycle. Such a cycle is unlikely to be broken if the opposition takes power in a revolt since victorious opposition rebels are typically reluctant to establish democracy. Governments that obtain power by force typically rule by force, concentrating power and repressing their opponents. They use authoritarian measures to concentrate their hold on power, fearing that other parties will seek to come to power in the same manner they did. Opposition parties that gain power by force not only violate the principle of constitutional succession but also encourage other parties to do the same.

By contrast, strengthening the coercive capacity of the state can bring an end to most opposition revolts, thereby terminating the cycle of rebellion and repression. I am not suggesting that strengthening the coercive capacity of the state will always be propitious for democratization. Indeed, some studies have suggested that increases in the coercive capacity of the state may undermine the likelihood of democracy by enabling authoritarian regimes to repress dissent (Albertus and Menaldo Reference Albertus and Menaldo2012; Hariri and Wingender Reference Hariri and Wingender2023). Nevertheless, where opposition revolts have been common, increasing the coercive capacity of the state may have a positive impact on the likelihood of democracy by encouraging the opposition to abandon the armed struggle. The opposition will not typically rebel if it expects any revolt to be quickly suppressed. Where armed struggle is foreclosed, the opposition will have incentives to pursue the electoral path to power. Under these circumstances, the opposition is likely to push for democratic reforms to reduce the government’s ability to manipulate elections and improve the opposition’s chances of winning. These include measures that establish the secret ballot, expand the franchise, prevent the police or military from intervening in elections, and mandate opposition party representation in the electoral commissions and the legislature.

The opposition, however, cannot always judge the strength of the military, nor can it necessarily assess its own military capabilities with any degree of reliability. As a result, it is difficult for the opposition to know what the costs of rebellion will be and what likelihood it has of prevailing in an armed revolt. Nevertheless, as the international relations literature has shown, warfare provides important information about the capabilities of both sides, which can shape decisions about whether to go to war (Slantchev Reference Slantchev2003; Wagner Reference Wagner2000). Recent conflicts can supply intelligence not only on the troops and weaponry both sides can mobilize but also on how effectively they will use these soldiers and equipment and how willing each side is to fight. Opposition groups are therefore likely to use recent experiences with rebellion to assess its costs and their prospects of capturing power through armed struggle.Footnote 5 If the opposition has triumphed in rebellions against the government in the recent past, then it is more likely to believe that it can do so again in the future. However, if the opposition has experienced repeated defeats, it is likely to conclude that future rebellions will yield the same outcome. The longer the time that has elapsed since an opposition victory in a rebellion, the more the opposition is likely to conclude that it will not prevail in the future. Similarly, where the opposition has experienced high casualties in recent uprisings, it is likely to believe that it will experience considerable casualties if it rebels again. Thus, repeated opposition defeats in costly rebellions may help to bring about democratization by pushing opposition parties to abandon the armed struggle and focus on the electoral path to power.

As Chapter 3 discusses, the coercive capacity of South American states was initially quite low (Johnson Reference Johnson1964; Lieuwen Reference Lieuwen1961; Rouquié 1987; Centeno Reference Centeno2002). For much of the nineteenth century, standing armies in the region were small and troops lacked training and sophisticated weaponry. South American armies also typically had poor leadership since political connections, rather than competence or training, determined officer recruitment and advancement. The weakness of the military encouraged the opposition to seek power through armed rebellions. Indeed, opposition revolts and other types of outsider rebellions were extremely common during the nineteenth century – they were much more frequent than insider revolts, such as military coups. These rebellions were occasionally successful, which undermined constitutional rule and encouraged further uprisings. Latin American governments, meanwhile, responded to the revolts by declaring states of siege, censoring the media, and repressing the opposition. These actions had profoundly negative implications for the prospects for democracy in the region.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, however, most Latin American governments took steps to strengthen the coercive capacity of the state by professionalizing their militaries with the assistance of foreign missions (Nunn Reference Nunn1983; Resende-Santos 2007). Military professionalization included: the acquisition of sophisticated weaponry such as artillery, repeating rifles, and machine guns; the establishment of military schools, including for noncommissioned officers; the adoption of more rigorous training for officers and soldiers; the enactment of merit-based criteria for advancement within the military; the creation of standardized requirements for military recruitment; and the formation of mass armies and military reserves. These measures made the military a larger, more disciplined, and more effective fighting force.Footnote 6

Military professionalization increased the costs of rebellion and made it less likely that the opposition could prevail in armed uprisings. Opposition rebellions in Argentina, Colombia, and Uruguay repeatedly failed in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and some of these rebellions, such as the Thousand Days War in Colombia, generated enormous casualties. As a result, opposition parties in these countries, along with Chile, which had developed a strong military even earlier, became reluctant to take up arms and increasingly focused on the electoral path to power. However, where the military remained weak, opposition parties and politicians continued to seek power by force, with negative implications for democracy.

But why didn’t authoritarian regimes in South America use their increasingly powerful militaries to repress the opposition and dispense with elections altogether? In a few cases, they did, but not typically for long. Repression was not costless. It could undermine the legitimacy of the regime and antagonize the citizenry who had come to expect elections, legislative representation, and a degree of civil liberties. Members of the ruling elite also frequently opposed any move to dispense with representative institutions since these institutions provided them with positions and patronage. The suppression of elections or the repression of the opposition could also lead to rebellions, which were disruptive even if the opposition had little chance of prevailing against a professionalized military. In addition, the military was sometimes reluctant to engage in repression. It was one thing to employ repression temporarily in response to a rebellion, but it was quite another to use it against a peaceful population and to maintain it indefinitely.

Moreover, as the literature on authoritarian regimes has shown, authoritarian leaders benefit in some ways from elections, civil liberties, and representative institutions, which can make the leaders reluctant to eliminate them (Brancati Reference Brancati2014; Gandhi and Lust-Okar Reference Gandhi and Lust-Okar2009). Elections can be used to signal the degree of strength and popular support of an authoritarian regime, which may deter the opposition from challenging it (Magaloni Reference Magaloni2008; Simpser Reference Simpser2013). Elections, the media, and legislatures also provide forums for the voicing of discontent, thereby providing useful information to leaders about political problems or disaffected constituencies, which the government can then seek to address (Gandhi Reference Gandhi2008; Brownlee Reference Brownlee2007; Geddes, Wright, and Frantz Reference Geddes, Wright and Frantz2018). Representative institutions may also be used to share power and to co-opt potential opponents by providing them with posts, patronage, and policies that they prefer (Blaydes Reference Blaydes2011; Svolik Reference Svolik2012). Finally, the media, civil liberties, and representative institutions may enable elites to monitor dictators and the dictators to monitor elites, ensuring that neither engages in excessive corruption or undertakes other actions that could undermine the authoritarian regime (Blaydes Reference Blaydes2011; Geddes, Wright, and Frantz Reference Geddes, Wright and Frantz2018; Svolik Reference Svolik2012).

For all these reasons, South American countries generally held elections and maintained representative institutions from independence through the early twentieth century.Footnote 7 Indeed, even when leaders took power by force during this period, it was common for them to subsequently call elections to consolidate their hold on power. Rather than eliminate elections and representative institutions, South American leaders typically preferred to maintain them and intervene regularly in these institutions to ensure they maintained control. This strategy provided the regimes with a degree of legitimacy as well as the other political benefits mentioned earlier without jeopardizing their hold on power.

Elections in South America only became free and fair, however, once democratic reforms were enacted in the early twentieth century. The professionalization of the military helped bring about democratization by encouraging the opposition to desist from armed uprisings and push for democratic reforms. Nevertheless, even professionalized militaries proved to be a threat to democracy in some instances. Although opposition revolts declined dramatically in the twentieth century owing to the professionalization of the military, military coups continued to take place. On balance, however, the strengthening and professionalization of Latin American militaries had a positive impact on the prospects for democracy in the region.

The Origins of Military Professionalization

What leads to military professionalization? Why did many Latin American countries professionalize their armed forces during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries?

The strengthening of Latin American militaries in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries stemmed from three main developments. First, the export boom brought large inflows of foreign currency to Latin American governments, providing them with the resources to contract foreign military missions, establish military schools, create mass armies, and import sophisticated weaponry. Second, Latin American countries faced considerable regional military conflict during this period, including two major wars and numerous militarized interstate disputes. Regional competition and conflict triggered an arms race of sorts. Once some Latin American countries upgraded their militaries, their neighbors felt considerable pressure to do so as well. Third, the nations that emerged victorious in interstate wars tended to invest more in their militaries than the nations that were defeated. Victory in war typically strengthened state-building forces, whereas losses weakened them (Schenoni Reference Madrid and Schenoni2024).

The development of a strong military and the acquisition of a monopoly on violence is only one aspect of the state-building process, but it is an important one.Footnote 8 The literature on state building has long been dominated by the bellicist approach, which argues that war produces state building. European nations, for example, developed systems of taxation to fund the militaries that facilitated conquest and ensured their survival. In Tilly’s (1975, 42) famous words, “war made the state, and the state made war.” Working from this approach, Centeno (Reference Centeno2002) contended that state building in Latin America was undermined by the relative absence of large-scale interstate wars in the region.Footnote 9 As Centeno (Reference Centeno2002, 8) points out, no Latin American country disappeared after 1840 as a result of war. Because they did not face the same risk of annihilation as European countries, Latin American countries did not have the same incentives to invest in the military or engage in state building more generally. Although Latin America suffered from numerous internal conflicts during the nineteenth century, Centeno (Reference Centeno2002, 127–130) and others argue that internal wars do not promote state building.Footnote 10 Internal wars can, under some circumstances, lead to military buildups that strengthen the armed forces, but they do not consistently do so. Indeed, civil wars often destroy the economy, divide the armed forces internally, and deplete scarce resources.

Latin American countries during the nineteenth century experienced a significant degree of international conflict, however. Between 1820 and 1914, Latin American nations fought almost as many interstate wars as European countries did, and these wars lasted much longer and killed a significantly larger percentage of the population than they did in Europe (Schenoni Reference Schenoni2021, 408). The late nineteenth century witnessed two particularly lengthy and bloody conflicts in South America: the War of the Triple Alliance (1864–1870), which pitted Paraguay against Argentina, Brazil, and Uruguay; and the War of the Pacific (1879–1883), in which Chile fought Bolivia and Peru. In these conflicts, the losing sides suffered significant casualties and lost large amounts of their territory. In the War of the Triple Alliance, for example, Paraguay lost half of its territory and 60–70 percent of its population, according to some estimates (Whigham Reference Whigham2002; Whigham and Potthast Reference Whigham and Potthast1999).Footnote 11 Although wars became less frequent after the 1880s, countries in the region continued to have numerous border conflicts and militarized disputes.

The wars and militarized conflicts in Latin America during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century provided incentives for countries to strengthen and professionalize their militaries (Resende-Santos 2007; Arancibia Clavel Reference Arancibia Clavel2002; Fitch Reference Fitch1998; Philip Reference Philip1985; Wesson Reference Wesson1986; Grauer Reference Grauer2015; Johnson Reference Johnson1964; Lieuwen Reference Lieuwen1961; Loveman Reference Loveman1999; Nunn Reference Nunn1983; Rouquié 1987; Schenoni Reference Schenoni2020). Chile was the first country to professionalize its armed forces, bringing in a German mission in 1885 that dramatically overhauled and strengthened the Chilean military. Beginning with Chile’s neighbors, most other South American countries also hired foreign military missions in the decades that followed. Thus, regional conflict provided an impetus for state building in Latin America as well as in Europe (Schenoni Reference Schenoni2021; Thies Reference Thies2005).Footnote 12

War outcomes also shaped military strength and professionalization in South America. As Schenoni (Reference Schenoni2021; 2024) argues, victory in wars strengthened state-building efforts in nineteenth-century Latin America by empowering those elites who had supported a strong army and state-building efforts. By contrast, loss in war often brought to power peripheral elites who had opposed the war and were not supportive of state building. Moreover, defeat in war could destroy a country’s army, as it did to Paraguay during the War of the Triple Alliance, and occupying forces were typically reluctant to allow their subjugated foes to rebuild their military.

Military professionalization and other forms of state building are expensive, however. It is costly to hire foreign military missions, establish military schools, purchase foreign weaponry, and create a permanent mass army. To finance these armies, European countries expanded domestic taxation, which required state building, but it was initially difficult for Latin American states to extract similar levels of resources, given the poor economic performance of the region in the decades that followed independence. Meager economic growth severely constrained tax revenues, which in turn limited government spending. Thus, most Latin American governments could ill afford to spend large sums of money on their armed forces during most of the nineteenth century.Footnote 13

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, however, Latin American countries experienced an export boom, which was fueled by technological advances, infrastructure improvements, greater political stability, and growing worldwide demand for Latin American products. The real value of exports increased nearly tenfold between 1870 and 1929, dramatically strengthening the region’s economies. Latin America’s gross domestic product (GDP) grew from $29.1 billion in 1870 to $194.9 billion in 1929 in constant 1990 dollars (Bértola and Ocampo Reference Bértola and Ocampo2013, 97).

Commodity booms and the expansion of trade financed state building in the region, including the modernization of the military, which involved significant government expenditures (Mazzuca Reference Mazzuca2021; Saylor Reference Saylor2014). The converse was also true: State building contributed to the expansion of exports and the economy by delivering public goods, such as infrastructure and political stability. The expansion of trade also provided incentives to build up the military since the export boom depended on the ability of Latin American states to pacify the areas where export commodities were produced and transported.Footnote 14

In Latin America, as in other parts of the world, the more developed countries advanced furthest in terms of military professionalization (Toronto Reference Toronto2017). The wealthier Latin American countries, such as Chile and Argentina, could more easily afford to make large investments in their armed forces. Indeed, Chile and Argentina engaged in an arms race of sorts in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, with both countries importing increasingly sophisticated weaponry. The more developed countries also had higher literacy rates, which facilitated the training of troops and officers. Although the poorer Latin American countries also sought to upgrade their militaries during this period, they had a difficult time matching the investment of the region’s military powers and their troops continued to be mostly illiterate and poorly trained.

Thus, interstate wars and conflicts provided the incentives for military professionalization in Latin America, whereas the expansion of the region’s trade furnished the wherewithal. Latin American states lacked the revenues to make major investments in their armed forces for much of the nineteenth century, but the export boom of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century made new resources available. The most developed countries made the largest investments in their militaries, but all countries in the region took some steps to upgrade their armed forces.

Political Parties and Democratic Reform

Although the professionalization of the military paved the way for democratization in the region, political parties, especially opposition parties, played the central role in the enactment and implementation of democratic reforms. Opposition parties typically promoted democratic reforms to level the electoral playing field and improve their chances of winning elections. Ruling parties, by contrast, usually resisted democratic reforms for the same reasons and used their power to block the measures. As a result, meaningful democratic reforms typically only passed where there were relatively strong opposition parties and where the ruling party split. In the wake of splits, ruling party dissidents sometimes sided with the opposition and pushed through reforms that helped create free and fair elections.

Scholars have long argued that political parties are central actors in the establishment of democracy (Collier Reference Collier1999; LeBas 2011; Capoccia and Ziblatt Reference Capoccia and Ziblatt2010; Gibson Reference Gibson1996; Middlebrook Reference Middlebrook and Middlebrook2000b; Rokkan Reference Rokkan1970; Schattschneider Reference Schattschneider1942; Ziblatt Reference Ziblatt2017; Valenzuela Reference Valenzuela1985; Lehoucq Reference Lehoucq2000). One branch of the literature has focused on conservative parties. Gibson (Reference Gibson1996), Middlebrook (Reference Middlebrook and Middlebrook2000b), and Ziblatt (Reference Ziblatt2017), for example, contend that traditional elites were more likely to tolerate democracy in countries that had strong conservative parties because these parties could protect elite interests. As a result, according to Gibson (Reference Gibson1996, 26), Latin American countries that developed strong conservative parties before the advent of mass politics experienced more years of democratic rule than countries where conservative parties were slow to emerge.Footnote 15

The arguments about conservative parties tend to focus on the role that these parties play in preserving, rather than creating, democracy. This begs the question of why conservative parties would support the establishment of democracy to begin with, given that the existing authoritarian regimes often represent the interests of conservative elites quite effectively. Bendix (Reference Bendix1969, 117) and Rokkan (Reference Rokkan1970, 32) argue that conservative parties have sometimes supported the enfranchisement of the lower classes (or women) because they have believed that they would vote for conservative parties. Nevertheless, this does not explain why conservatives would support other democratic reforms, such as the secret ballot, proportional representation, or the creation of independent electoral authorities. As we shall see, conservative support for democracy in nineteenth-century South America was contingent: Conservative parties tended to support democratic reform when they were in the opposition but not when they were in power.

Another branch of the literature has identified the ruling party more generally as the main proponent of democratic reform. Schattschneider (Reference Schattschneider1942), Rokkan (Reference Rokkan1970), and Collier (Reference Collier1999), for example, argue that ruling parties often extended the franchise in order to win votes among sectors of the population who did not yet have strong partisan attachments. According to Collier (Reference Collier1999, 55): “Incumbents extended the suffrage to the working class much less in response to lower-class pressures than in response to their own political needs as they jockeyed for political support.” Other studies contend that ruling parties enfranchised women in order to win their political support in the face of growing electoral competition (Przeworski Reference Przeworski2009a; Teele Reference Teele2018, 32). Some scholars maintain that ruling parties are especially likely to democratize when they believe that they can continue to win elections and hold on to power after the return to democracy (Riedl et al. Reference Riedl, Slater, Wong and Ziblatt2020; Miller Reference Miller2021; Slater and Wong Reference Slater and Wong2013).

The focus on ruling parties is understandable given that they are influential actors who have the power to enact democratic reforms and strengthen (or undermine) democracy. Moreover, strong ruling parties can serve as a check on personalism and executive overreach (Rhodes-Purdy and Madrid Reference Rhodes-Purdy and Madrid2020). Nevertheless, it is not clear why ruling parties would have supported democratization in Latin America during the nineteenth and early twentieth century. During this period, there were few, if any, international pressures to democratize, and the ruling parties typically controlled elections through a wide range of techniques, including fraud and intimidation, so they did not need to win votes by extending the suffrage. Moreover, suffrage expansion had risks since it could lead to a flood of new voters with uncertain loyalties who could destabilize the existing political system. Indeed, ruling parties often dominated elections by relying on the support of state employees and members of the military and/or national guard who typically represented a large share of the electorate before the expansion of the franchise. In addition, eliminating certain suffrage restrictions, such as income and literacy requirements, could make it harder for the ruling parties to disqualify opposition voters since selective application of these criteria was historically used to turn away supporters of the opposition.

Ruling parties had even fewer incentives to enact the other types of democratic reforms that helped bring democracy to Latin America during this period. These included measures that mandated the secret ballot, required the representation of minority parties, created more independent electoral authorities, and banned the police or military from intervening in elections. Ruling parties typically opposed these reforms because they weakened their control of government institutions and reduced their ability to intervene in elections. The creation of independent electoral authorities and the adoption of the secret ballot, for example, made it more difficult for ruling parties to monitor the voting process and to identify and sanction opposition voters. Laws that banned the police or military from intervening in elections hindered government efforts to intimidate voters or coerce state employees to support the ruling party (see Table 1.1).

Table 1.1 Opposition parties and democratic reform

| Type of reform | Benefits of the reform for the opposition and democracy | Examples of reforms |

|---|---|---|

| Elimination of some suffrage restrictions | Leads to an influx of new voters and reduces electoral weight of state employees; makes it harder to disqualify opposition voters | Chile 1874 Colombia 1910 Uruguay 1918 |

| Enactment of obligatory voting and/or registration | Leads to an influx of new voters and reduces electoral weight of state employees; makes it harder to disqualify opposition voters | Argentina 1912 Uruguay 1918 |

| Adoption or strengthening of the secret ballot | Reduces vote buying and government control of the electoral process | Chile 1890 Argentina 1912 Uruguay 1918 |

| Adoption of measures that mandate representation of minority parties | Increases legislative representation of opposition parties | Chile 1874 & 1890 Argentina 1912 Uruguay 1918 |

| Creation of independent electoral authorities | Reduces fraud and weakens the executive’s control of the electoral process | Chile 1874 Argentina 1912 |

| Changes to voter registration procedures | Makes it more difficult to disqualify voters; reduces government control | Chile 1890 |

| Participation of parties in the scrutiny of the vote | Reduces fraud and weakens the executive’s control of the electoral process | Chile 1890 |

| Ban on military/police participation in elections | Reduces voter intimidation; reduces the electoral weight of state employees | Uruguay 1918 |

| Strengthening of the attributions of Congress | Weakens executive dominance | Colombia 1910 |

Even leaders of liberal ruling parties were reluctant to support democratic reforms because they feared that such reforms might jeopardize their hold on power. As one Liberal politician in Brazil quipped: “nothing so much resembles a Conservative as a Liberal in power” (cited in Barman Reference Barman1988, 229). A desire to hold on to power also stymied the liberal impulses of leaders in other regions. In discussing Catherine the Great’s hesitance to enact democratic reforms, Gopnik (Reference Gopnik2019, 58) observes: “For the catch, of course, with all enlightened despots is that they feel about liberty for their subjects the way the young St. Augustine felt about chastity for himself: they want it, just not quite yet.”

This does not mean that ruling parties never supported democratic reforms in Latin America during this period. In some cases, ruling parties supported reforms that they believed would not jeopardize their control over elections. In other cases, ruling parties agreed to reforms because they had little choice, having lost control of the legislature or the constituent assembly. Finally, as we shall see, ruling party dissidents often supported democratic reforms. These ruling party dissidents typically represented a small minority of the members of the ruling party, but in a few cases, they gained control of the legislature (usually with the support of the opposition party) and pushed through democratic reforms to weaken the traditional ruling elites’ control of the political system. Nevertheless, for the most part, ruling parties resisted meaningful democratic reforms during this period and used their influence to block or water down proposed measures.Footnote 16

By contrast, opposition parties generally supported democratic reforms in Latin America during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. In fact, opposition parties were the main proponents of democratic reforms during this period in Latin America since there were no significant international pressures to establish democracy at the time and no other important domestic groups consistently supported democratic reform. Labor unions, for example, were still relatively weak during this period and were dominated by anarcho-syndicalist currents that rejected liberal democracy. The bourgeoisie was not well organized either; nor did it consistently support democratic reforms.

Opposition parties had strong electoral incentives to support democratic reforms. Measures such as the establishment secret ballot, the creation of independent electoral authorities, and prohibitions on police and military involvement in elections improved the opposition’s electoral prospects by weakening the government’s control of the electoral process. Other reforms, such as the adoption of electoral rules that mandated the representation of minority parties, typically boosted the number of legislative seats held by opposition parties. Even suffrage expansion and obligatory voting measures often benefited the opposition because they made it more difficult to disqualify opposition voters and led to an influx of new voters with unclear loyalties to whom the opposition could appeal.Footnote 17

Opposition parties would typically support democratic reforms only while they were in the opposition, whereas ruling parties would often oppose democratic reforms only while they held power. For example, opposition Liberals in Chile generally supported democratic reform during the mid-nineteenth century, whereas the ruling Conservatives opposed it. However, when the Liberals gained control of the government in the late nineteenth century, they began to resist democratic reform, while the Conservatives who moved into the opposition began to support it.

Although the opposition generally supported democratic reforms, it was difficult for it to enact or enforce these measures during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, given that the ruling party typically controlled the legislature as well as the executive branch of government. In some countries, however, the opposition developed relatively strong parties, which enhanced the likelihood of democratic reform. These parties had widespread and enduring ties to the electorate and permanent national organizations with broad networks of affiliated local associations.

Strong opposition parties facilitated democratic reform for several reasons.Footnote 18 First and most importantly, the more powerful the opposition party, the more likely it was to control significant numbers of seats in the legislature, which made it easier to pass democratizing electoral reforms. In addition, strong opposition parties tended to have higher rates of party discipline, which also increased the likelihood that they could enact democratic reforms. Second, strong opposition parties could coordinate efforts to push for democracy and they could negotiate more effectively with the ruling party. Where opposition parties were strong, they could put greater pressure on the regime and they could make and enforce bargains, which facilitated negotiations over democratic reform. Third, strong opposition parties were more likely to believe that they could triumph in fair elections, which gave them greater incentives to push for democratizing reforms. Fourth and finally, strong opposition parties tended to have longer time horizons since they were likely to endure. Thus, they could afford to be patient and to agree to democratic reforms that might not give them access to power immediately but would benefit them in the long run.

Some might object that the relationship between strong opposition parties and democracy is endogenous since democratization might have led to powerful opposition parties rather than vice versa. However, the rise of strong opposition parties clearly predates the emergence of democracy in the region. As Chapter 4 discusses, parties first emerged in Latin America in the middle of the nineteenth century, and by the last quarter of the century some of them had developed into tightly organized national institutions that selected candidates, drafted platforms, maintained memberships, and developed ties to the electorate (Sabato Reference Sabato2018, 62–64). Particularly strong opposition parties emerged in Chile, Colombia, and Uruguay, even though they were governed by authoritarian regimes during this period. It is certainly true that the existence of regular elections in which the opposition could compete was necessary for strong opposition parties to emerge, but all South American countries met this criterion for most of the late nineteenth century.

Nevertheless, even strong opposition parties could not typically enact democratic reforms on their own. Splits within ruling parties, however, sometimes weakened the incumbent parties’ control over the legislature and provided opportunities for the opposition. Party splits took place frequently in South America during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, but the critical splits were those that led key members of the ruling party or coalition to defect and ally with the opposition.Footnote 19 Together, the ruling party dissidents and the opposition sometimes controlled enough votes to enact democratic reform.

Various studies have argued that splits within authoritarian regimes played a key role in the third wave of democratization, but splits clearly played a key role in the first wave as well (O’Donnell and Schmitter 1986; Przeworski Reference Przeworski, Mainwaring, O’Donnell and Valenzuela1992; Madrid Reference Madrid2019a; 2019b). Ruling party splits represented a serious threat to authoritarian regimes during this period because the dissidents often had considerable resources and political networks. Not only did the ruling party dissidents frequently hold legislative seats but they also often had the financial resources and following necessary to win elections. As Schedler (Reference Schedler and Lindberg2009, 306) argues: “if anyone is capable of defeating the incumbent [in competitive autocracies], it is someone from the inner ranks of the ruling elite.”

A wide range of factors can lead to ruling party splits, including differences over ideology or policy issues, but in electoral authoritarian regimes, internal leadership struggles are typically the main cause of divisions. Elections create intense competition for key nominations. When prominent politicians do not earn their desired nominations, they sometimes decide that they can improve their political prospects by joining the opposition (Ibarra Rueda Reference Ibarra Rueda2013; Langston Reference Langston2002). Defections of minor politicians are unlikely to have much impact on the ruling party in electoral authoritarian regimes, but the exit of major leaders can have significant repercussions because they frequently take many of their supporters and allies with them. Moreover, the defections of major leaders can have a snowball effect since other politicians may also be tempted to defect if they see that their party is weakening. Of course, major political figures in electoral authoritarian regimes are often reluctant to defect from the ruling party because they fear that they will not be able to win elections in the face of opposition from the ruling party. Nevertheless, ruling party dissidents who are marginalized within their parties sometimes conclude that defection is the best way to achieve their professional aims and policy goals.

Once dissidents break with the leadership of the ruling party, they, like opposition parties, have strong incentives to enact democratic reforms. Without democratic reforms, ruling party leaders are likely to use their control of the electoral process to try to prevent the dissidents, as well as members of the opposition, from winning elections. Thus, ruling party dissidents will seek to enact democratic reforms to weaken the ruling party leaders’ control of the electoral process.

Ruling party splits sometimes bring about democratic reform by leading to divided government. In the wake of splits, dissident members of the ruling party at times leave the governing coalition and join forces with the opposition, providing them with a majority in the legislature. As a result, the dissidents and the opposition sometimes have enough votes to push through democratic reforms over the objections of the ruling party. Under these circumstances, the ruling party may seek to negotiate reforms with the opposition, rather than risk the imposition of such measures. As we shall see, this was the path to democratic reform taken in Chile and Uruguay in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century.

Where the defecting faction is particularly large, the ruling party dissidents may gain control of the executive as well as the legislative branch of government. Even where the dissidents occupy the executive branch, however, they will still have incentives to enact democratic reforms if their hold on power is threatened by the traditional ruling elites. In some countries, particularly those with federal systems, regional or local officials, such as governors and mayors, have a great deal of influence over the electoral authorities and the electoral process. Ruling parties that govern for a long time typically control these regional and local officials and they frequently hang on to this influence even after they lose the presidency. Indeed, many ruling parties build important local-level political machines while in office. Thus, once they gain control of the executive branch, ruling party dissidents may support democratic reforms to weaken the traditional leaders’ control of the electoral process. As we shall see, this is what occurred in Argentina and Colombia in the early twentieth century.

Thus, a combination of strong opposition parties and ruling party splits helped lead to democratization in some Latin American countries during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. Strong opposition parties aggressively promoted democratic reform during this period, but they did not have the votes to enact democratic reforms on their own, given the resistance of ruling parties. Splits, however, weakened the ruling party’s control of the legislature in some countries, and provided an opportunity for the opposition to push through reforms with the assistance of ruling party dissidents.

The Origins of Strong Parties in South America

What led to the emergence of strong opposition parties in South America during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century? And why did strong parties arise in some countries and not others?

Parties emerged throughout South America during the nineteenth century, but two factors helped shape whether they developed strong organizations. First, strong parties tended to arise in those countries where the population was concentrated in a relatively small area with no major geographical obstacles dividing them. This made it easier for politicians and party leaders to build and manage national organizations and communicate with most of the population. Second, strong parties were more likely to emerge in those countries that had relatively balanced religious or territorial cleavages – that is, where neither side of a cleavage clearly dominated the other. These types of cleavages often gave birth to strong parties on both sides of the cleavage, which was good for democracy because at least one of the parties was typically in the opposition where it would push for democratic reform.

Most South American countries were internally fragmented during the nineteenth century so that there was little communication among people living in different regions. Seven of the ten countries in the region spanned more than 750,000 square kilometers, and Brazil alone covered more than 8.5 million square kilometers. The population of these countries was overwhelmingly rural in the nineteenth century and citizens were frequently located at a great distance from one another. Moreover, the territories of these countries were divided by often impenetrable mountains, forests, and swamplands. In some countries, such as Bolivia, Colombia, and Ecuador, the capital and other major cities were located far inland, which complicated internal travel. To make matters worse, transportation and communications infrastructure was quite primitive in the nineteenth century. Railroads did not penetrate Latin America until the late nineteenth century, and even then, they generally linked together only a small area of the country. As a result, in some countries it could take weeks to travel from one major city to another. Even communication was often difficult because the telegraph also came late to South America and telegraph lines were frequently out of service even where they existed.

The high level of geographic fragmentation of many countries in the region made it difficult to form strong national parties. Politicians could not easily campaign throughout their countries. Nor could party leaders manage branches and affiliated organizations nationwide. In addition, the large, geographically fragmented South American countries tended to be quite culturally diverse, which further complicated efforts to form national parties. Many Latin Americans had stronger attachments to their region than their nation. These attachments led to the emergence of numerous regional parties, but most of these parties failed to transcend their regional bases, creating a plethora of small and weak regional organizations (Gibson Reference Gibson1996). Indeed, Colombia was the only large, geographically fragmented, and culturally diverse country to develop strong national parties during this period.

Nevertheless, a few South American countries, namely Chile, Paraguay, and Uruguay, had relatively low levels of geographic fragmentation, which facilitated party building.Footnote 20 In these countries, the bulk of the population was concentrated in relatively small areas that were not divided by major geographic barriers. In Uruguay and Paraguay, most of the population lived within a relatively short distance of the capital. Although Chile was much longer and more mountainous than Paraguay or Uruguay, the vast majority of its population in the nineteenth century resided in the Central Valley, which was easily traversable. The concentration of the population in the three countries made it easier for national politicians and party leaders to campaign and build party organizations in all the major towns and cities during the nineteenth century. The lack of geographic fragmentation also reduced cultural diversity and weakened regional identities, which made it easier to form national party platforms that had broad appeal.Footnote 21

Balanced social cleavages also fostered the emergence of strong parties in Latin America during the nineteenth century. The literature on political parties has long emphasized the role that class, ethnic, religious, and territorial cleavages have played in the formation of party systems (Lipset and Rokkan Reference Lipset, Rokkan, Lipset and Rokkan1967; Caramani Reference Caramani2004; Bartolini and Mair Reference Bartolini and Mair1990; Rokkan Reference Rokkan1970). Lipset and Rokkan (Reference Lipset, Rokkan, Lipset and Rokkan1967), for example, argue that various international developments, including the Protestant reformation, the French Revolution, the process of state formation, and the Industrial Revolution, generated strong center–periphery, church–state, land–industry, and owner–worker cleavages that formed the basis of party systems in Europe. Caramani (Reference Caramani2004), meanwhile, shows how the emergence of strong class and church–state cleavages in the nineteenth and early twentieth century helped nationalize European party systems, enabling the most important parties to build support throughout their territories. As many scholars have noted, however, social cleavages do not automatically give birth to parties. Political entrepreneurs must translate the cleavage into the political arena by developing parties that represent voters on each side of a cleavage.

For a cleavage to translate into the political arena, elites with sufficient resources to develop and sustain such parties must be present on both sides of the cleavage. Not all cleavages present in Latin America during the nineteenth century translated themselves into the political arena, in part because they did not have elites in large numbers on both sides. Neither class nor ethnic cleavages, for example, played an important role in the emergence of parties in Latin America during the nineteenth century. Most Latin American nations had significant ethno-racial diversity, but in the nineteenth century only the European-origin population had the resources to create political parties. In many countries, large sectors of the indigenous and Afro-Latino population were not even eligible to vote during the nineteenth century because they were illiterate, did not meet the income requirements, or were not considered independent citizens. Nor could class cleavages easily serve as the basis for strong parties in Latin America because neither the working classes nor the middle classes were well organized. A few working-class parties emerged during the nineteenth century, but none survived for very long. The middle classes participated in some of the parties that formed during this period, but none of the major parties were dominated by members of the middle class or were created to defend middle class interests.Footnote 22 Indeed, the only important parties to emerge in the region during the nineteenth century were created by and catered to elites.

The two most intensely felt cleavages that divided South American elites during the nineteenth century were territory and religion. Territorial cleavages did not give birth to national parties in most countries, however, because territorial divisions were numerous and fragmented the electorate. In most countries, various regional parties emerged, but none of these parties could unite large sectors of the electorate. Territorial cleavages only gave birth to strong parties in Uruguay where the population was relatively balanced between people living in or near the capital and those residing in the provinces. In Uruguay, the population surrounding Montevideo was of sufficient size to sustain a major party, and the provinces were sufficiently compact to stitch together a party representing peripheral areas. In most South American countries, however, the population in the provinces far outnumbered the population in the capital, which made it difficult for a party based in the urban center to compete. Moreover, the provincial areas were so dispersed and heterogenous that it was difficult to forge a party that could unite them.

During the nineteenth century, religious (church–state) cleavages played the most important role in the formation of party systems. Even before independence, Latin American elites were divided between liberals who were critical of the Catholic Church and conservatives who defended it, but their differences deepened over the course of the nineteenth century. Both conservative and liberal politicians created parties to promote their causes and advance their personal ambitions. Conservative parties tended to represent the interests of the Catholic Church in the political arena, whereas liberal parties tended to attack the Church, calling for freedom of religion and the separation of church and state. Conservative and Liberal parties often differed on other issues, such as federalism or free trade, but none of these other issues were able to mobilize their supporters with the same level of passion as did the religious issue. As a result, the religious cleavage came to be reflected in most of the region’s party systems.

The parties became strongest where the cleavage was sharp and relatively balanced – that is, where there was a rough parity between conservative and liberal forces and where both sides fought vigorously to advance their goals. This occurred in Chile and Colombia where the Catholic Church was traditionally strong, but where liberals gradually gained power and implemented sweeping reforms, prompting a conservative backlash (Middlebrook Reference Middlebrook and Middlebrook2000a, 10). By contrast, where one side clearly had the upper hand, the parties that emerged from the cleavage tended to be weaker and more ephemeral. In countries where the Church was strong and the liberal impulse was weak, such as Bolivia, Ecuador, and to a lesser extent Peru, conservatives had few incentives to invest in party building because of the absence of a significant liberal threat. Politics in these countries was often more personalistic than programmatic, and parties had shallow roots in part because they failed to establish issue-based linkages to the electorate. In countries where the Church was weak, such as Brazil, Paraguay, Uruguay, and Venezuela, conservative parties also tended to be weak and ephemeral, and the religious cleavage failed to provide the basis for the emergence of a strong and programmatic party system (Middlebrook Reference Middlebrook and Middlebrook2000a, 15–22).Footnote 23

Thus, balanced religious or territorial cleavages, along with the concentration of the population in relatively small areas, contributed to the formation of strong parties in some Latin American countries. Balanced cleavages typically created strong parties on both sides and, as a result, countries that had strong opposition parties typically had strong ruling parties as well. As we have seen, democratic reforms were typically only enacted when the ruling party split. Under these circumstances, strong opposition parties could take advantage of a moment of ruling party weakness to push through reforms.

Regime Outcomes in South America

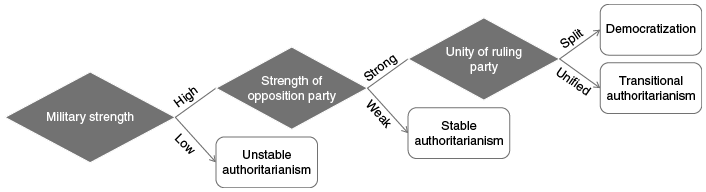

As the preceding discussion makes clear, regime outcomes in South America during the nineteenth and early twentieth century were shaped by three main variables: the strength of the military, the strength of opposition parties, and the unity of ruling parties (see Figure 1.1). These three variables did not change in a strict sequence, nor were they closely causally related to each other. The strengthening and professionalization of the military did not cause strong opposition parties to emerge, nor did it necessarily precede the rise of strong opposition parties. In fact, in two of the cases, Colombia and Uruguay, strong opposition parties arose before the professionalization of the military and the establishment of a state monopoly on violence. Similarly, the emergence of strong opposition parties did not necessarily cause or precede ruling party splits, but it did increase the likelihood that such splits brought about democratization.

Figure 1.1 Determinants of regime outcomes in South America before 1930

Each of these variables was driven mostly by exogenous factors. Regional military competition, international conflicts, and export wealth, for example, shaped the likelihood that countries would strengthen and professionalize their militaries, whereas the geographic concentration of the population and the existence of balanced cleavages influenced the strength of parties. Party splits were typically caused by intraparty leadership competition, although ideological and programmatic differences sometimes gave birth to party splits as well. For the sake of simplicity, the figure depicts only the three main variables and their associated outcomes.

Where the military was weak, the most common outcome was unstable authoritarianism, which I define as authoritarian regimes characterized by frequent outsider revolts that occasionally overthrow the government. As Chapter 3 discusses, most South American countries were unstable authoritarian regimes during the nineteenth century and a few countries remained in this category during the early twentieth century in large part because they were slow to professionalize their militaries. In these countries, military weakness encouraged the opposition to resort to armed revolts, especially given the meager likelihood of defeating the ruling party at the ballot box. These revolts sometimes succeeded, but even where they did not, they were destabilizing and deepened authoritarian rule. Regimes often responded to the revolts with repression, which created cycles of violence that led to greater political instability and authoritarianism.

Where the military was relatively strong, the regime outcome depended in large part on the strength of opposition parties. If the opposition parties were weak, the most common outcome was stable authoritarianism, which I define as authoritarian rule in which outsider revolts are uncommon and do not typically endanger the government.Footnote 24 In these cases, the opposition rarely, if ever, revolted because it had minimal prospects of defeating a strong military, but it sometimes called on the military to overthrow the government. Weak opposition parties also had little chance of prevailing in elections, particularly given government intervention on behalf of the ruling party. As a result, the opposition often chose to abstain from elections, but when it competed, it fared poorly. Thus, authoritarian rule was stable because the opposition did not pose a military or an electoral threat to the regime.

By contrast, if the military was professionalized and the opposition was organized into a strong party, the fate of the regime depended in large part on the unity of the ruling party. As long as the ruling party remained united, it could use its control of the electoral process to tilt the playing field in its favor, ensuring that it gained consistent victories at the polls.Footnote 25 The strength of the opposition party would enable it to win some legislative seats, but the prospects for democratic reform remained meager since the opposition had little chance of winning a majority of the legislature or capturing the presidency. Nevertheless, the opposition typically refrained from revolts, given the scarce prospects of defeating a professional military. Although these regimes resemble stable authoritarian regimes, given their absence of revolts, I refer to them as transitional authoritarian regimes because they represent at best a temporary equilibrium since splits within ruling parties were relatively frequent.

If the ruling party split, the prospects for democratization would increase considerably. Under these circumstances, ruling party dissidents would often join forces with the opposition to enact democratic reforms to weaken the ruling party’s control of elections. As we shall see, this is what occurred in Chile in 1890, Colombia in 1910, Argentina in 1912 and Uruguay in 1918.

Table 1.2 scores the countries on two of the key independent variables – military and party strength – and shows how these two variables influenced regime outcomes in the early twentieth century. (I omit the variable on ruling party splits from the table because it explains the precise timing of democratization, which is not the focus here.) I count as having relatively strong militaries or parties any case that is scored as medium or high in terms of military or party strength. As the table indicates, democracy arose in the early twentieth century in those South American countries that had developed strong militaries and parties by this time, namely Argentina, Chile, Colombia, and Uruguay. By contrast, relatively stable authoritarian regimes emerged in those countries that had strong militaries but had failed to develop strong parties, specifically Brazil, Peru, and Venezuela. Finally, those South American countries that failed to produce strong militaries (Bolivia, Ecuador, and Paraguay) remained unstable authoritarian regimes, regardless of the strength of their parties.

Table 1.2 Scoring regime outcomes in South America during the early twentieth century

| Countries | Military strength | Party strength | Early twentieth-century regime outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chile | High | High | Democracy |

| Uruguay | Medium | High | Democracy |

| Argentina | High | Medium | Democracy |

| Colombia | Medium | High | Democracy |

| Brazil | High | Low | Stable authoritarian regime |

| Peru | Medium | Low | Stable authoritarian regime |

| Venezuela | Medium | Low | Stable authoritarian regime |

| Bolivia | Low | Low | Unstable authoritarian regime |

| Ecuador | Low | Low | Unstable authoritarian regime |

| Paraguay | Low | Medium | Unstable authoritarian regime |

As we shall see, the most robust democracies arose in Chile and Uruguay. Chile was the first South American country to professionalize its armed forces, and by the late nineteenth century it had perhaps the strongest military in the region. As a result, the Chilean opposition largely abandoned the armed struggle after the 1850s and began to focus on the electoral path to power.Footnote 26 Strong opposition parties also developed in Chile during the late nineteenth century and these parties began to promote democratic reforms to level the electoral playing field. Thanks in part to splits within the ruling party, the opposition managed to push through electoral reforms in 1874 and 1890 that significantly expanded the suffrage and established the secret ballot, paving the way for the emergence of democracy in Chile.

Uruguay was slower to professionalize its military than Chile and, as a result, the Uruguayan opposition continued to carry out major armed revolts into the first decade of the twentieth century. At the turn of the century, however, the Uruguayan government took steps to strengthen and professionalize its military, which led to the opposition Blancos’ devastating defeat in the 1904 civil war. Subsequently, the main opposition leaders abandoned the armed struggle and concentrated on the electoral path to power, although some members of the opposition participated in a final revolt in 1910. Strong parties arose in Uruguay during the late nineteenth century, but it was not until the second decade of the twentieth century, after the opposition Blanco Party abandoned the armed struggle, that democracy emerged. In 1917–1918, the Blancos took advantage of the split within the ruling Colorados to push through a new constitution that instituted universal male suffrage, established the secret ballot, mandated proportional representation, and set Uruguay on a democratic path.

Democracy also arose in Argentina and Colombia during the early twentieth century, but it proved weaker there than in Chile and Uruguay, although the weakness of the Argentinian and Colombian democracies only became evident after 1929. Argentina, like Chile, strengthened and professionalized its military in the late nineteenth century, which led to a dramatic decline in the revolts that had plagued the country throughout most of the century. After the military easily squashed a final revolt in 1905, the opposition abandoned the armed struggle, although it initially refused to participate in elections to protest continued government electoral manipulation. Parties were slower to develop in Argentina than in Chile and Uruguay, but by the end of the nineteenth century, a strong opposition party, the UCR, had emerged. The Radicals pushed for democratic reforms that would ensure free and fair elections, but these measures were not passed until 1912 after a split within the ruling party led to the election of a dissident faction led by President Roque Sáenz Peña. These reforms, in turn, helped lead to the election of a Radical president, Hipólito Yrigoyen, in the country’s first free and fair presidential election in 1916. Once the Radicals took power, however, Argentina lacked a strong opposition party to compete effectively with the ruling party or to prevent it from intervening in elections and concentrating power. This led the opposition to call on the military to intervene in 1930, a process that would be repeated in subsequent years.

Colombia also professionalized its armed forces at the outset of the twentieth century, although to a lesser degree than Argentina and Chile. The strengthening of the Colombian military, along with the bitter memory of the bloody Thousand Days War (1899–1902), discouraged the opposition from carrying out revolts after 1902, and led it to focus increasingly on elections. Colombia, like Chile and Uruguay, had developed strong parties in the nineteenth century, and the opposition Liberal Party used its influence to push for democratic reforms. Nevertheless, as in Argentina, major reforms were not passed until the ruling party split in the early twentieth century and a dissident faction came to power. This faction, which was composed of both Liberals and dissident Conservatives, pushed through constitutional reforms that expanded suffrage rights, strengthened horizontal accountability, and guaranteed minority representation, which helped bring democracy to Colombia. However, the failure of the military to achieve a nationwide monopoly on violence led to periodic outbreaks of regional violence throughout the twentieth century, which undermined the country’s democracy.

Relatively stable authoritarian regimes arose in Brazil, Peru, and Venezuela because the countries had strong militaries but weak parties during the early twentieth century. Brazil was the first of these countries to develop a strong military: It modernized its armed forces during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, which helped reduce the revolts that had plagued Brazil during the early nineteenth century. The weakness of parties in Brazil, however, meant that the opposition had little chance of prevailing in elections, particularly given governmental electoral manipulation. As a result, the opposition often abstained from presidential elections or offered token candidates, enabling the candidates chosen by the ruling elites to win overwhelming victories during the first three decades of the twentieth century.

Venezuela also developed a relatively stable authoritarian regime during this period, but it differed significantly from that of Brazil. In Venezuela, the government of Cipriano Castro, which came to power through armed revolt in 1899, modernized and strengthened the military. This gradually brought an end to the frequent opposition revolts that had plagued Venezuela throughout the nineteenth century. In 1908, Castro’s right-hand man, General Juan Vicente Gómez, seized power and then governed with an iron hand until his death in 1935. Because Venezuelan parties were weak, they could offer little opposition to Gómez’s regime, enabling him to manipulate elections and consolidate his rule.

A relatively stable authoritarian regime also arose in Peru during this period, although it experienced some instability in the 1910s. With the assistance of a French military mission, Peru modernized its armed forces at the turn of the century, which helped bring an end to the frequent opposition revolts that had plagued it during the nineteenth century. The Civil Party used its control of the electoral authorities to win repeated elections in the early twentieth century, which opposition parties were too weak to resist. An opposition candidate, Guillermo Billinghurst, did manage to gain power in 1912 thanks to the support of urban workers who disrupted the elections in Lima, but he was deposed in a 1914 military coup, and the Civil Party subsequently returned to power. In 1919, however, former President Augusto Leguía seized power with the assistance of the military and the police. Leguía then manipulated Peruvian political institutions to remain in office until 1930.

The three other South American countries – Bolivia, Ecuador, and Paraguay – failed to strengthen their militaries significantly during the early twentieth century and, as a result, they remained plagued by revolts and political instability. Of the three countries, Bolivia undertook the greatest efforts to professionalize its military during this period, bringing in a French and then a German military mission at the outset of the twentieth century. These missions appeared to have initially made progress in strengthening the army, but the outsider revolts that had disappeared in the first two decades of the twentieth century resumed in the 1920s and the military struggled to suppress them. Indeed, the opposition successfully overthrew the government in 1920. The weakness of Bolivian parties also undermined the prospects for democracy during this period. Opposition parties were too feeble to enact democratic reforms or resist government electoral manipulation, and, as a result, the ruling party consistently won presidential elections by large margins.

Ecuador made even less progress than Bolivia in modernizing its military in the early twentieth century. The small Chilean mission that Ecuador hired during this period failed to make much of an impact and the military remained heavily politicized and underfunded. As a consequence, Ecuador continued to suffer frequent revolts – there were five major outsider revolts as well as two military coups between 1900 and 1929 – and the rebellions in 1906 and 1911 overthrew the government. The weakness of parties in Ecuador also hindered the prospects for democracy since it made it difficult for the opposition to enact democratic reforms or prevent the government from manipulating elections. Thus, the opposition often abstained from elections or offered only token opposition.

Finally, Paraguay also failed to professionalize its military during the early twentieth century, and as a result, its armed forces remained small, highly politicized, and poorly trained and equipped. This encouraged the opposition to seek power through armed rebellions. Paraguay suffered fourteen revolts between 1900 and 1929, and eight of these rebellions overthrew the government. Although the country began to develop strong parties in the early twentieth century, the political opposition viewed armed revolts as the most effective means of gaining power, given government manipulation of elections, so it typically abstained from presidential elections. The one exception was the relatively free and fair 1928 presidential elections, but even in this contest, the opposition candidate was unable to overcome the advantages of the ruling party.

Thus, the strength of the military and parties shaped regime outcomes in South America during the first three decades of the twentieth century. Democracy emerged in some countries and stable or unstable authoritarian regimes in others, depending on their configurations of military and party strength. As the Conclusion discusses, these variables would continue to shape political outcomes in the decades that followed, albeit to a lesser degree.

Alternative Explanations

Existing theories shed light on certain aspects of the democratization process in South America, but they offer at best a partial explanation for the emergence of democracy in the region. Structural theories, for example, offer explanations for the cross-national variance in democracy, but they struggle to explain the precise timing of democratization. Moreover, neither structural theories nor existing actor-based theories correctly identify the key actors behind democratic reforms in South America or explain why they prevailed over opponents of reform. This study builds on these theories but seeks to offer a thicker and more complete explanation for the birth of democracy in the region.