1. Introduction

Jet noise is an environmental challenge that the aerospace industry must face today and for years to come. High-speed aircraft and space launchers commonly feature multi-jet engines to supply the required levels of thrust, with twin-jet configurations being the most common. Twin-jet flow fields present a number of challenges in comparison to single jets, which have been widely studied in the past. When close to each other, the jets may interact at the hydrodynamic and acoustic levels, yielding complex physical mechanisms that remain to be understood. Early experiments studying twin-jet configurations (Bhat Reference Bhat1977; Kantola Reference Kantola1981) identified mechanisms that result in a reduction of the far-field noise with respect to an equivalent isolated jet, due in part to an acoustic shielding of one jet by the other. In contrast, recent experimental observations by Bozak & Henderson (Reference Bozak and Henderson2011) have revealed enhanced noise levels in the plane contained between the two jets, which are above those corresponding to two linearly superposed incoherent jets.

The development of jet-noise reduction and control technologies requires understanding and appropriate simplified models for the mechanisms of sound generation. This has motivated study of the dynamics of turbulent shear flow. In this regard, the importance of ordered motions (today known as coherent structures) in turbulent planar mixing layers and jets has been recognised since the pioneering experimental observations by Mollo-Christensen (Reference Mollo-Christensen1967), Crow & Champagne (Reference Crow and Champagne1971) and Brown & Roshko (Reference Brown and Roshko1974). Since then, the connection between the sound radiated by high-speed jets and the coherent structures has been the focus of significant research, as reviewed by Jordan & Colonius (Reference Jordan and Colonius2013). Coherent structures were found to be reminiscent of linear instability waves growing in harmonically forced supersonic jets, a finding that prompted the use of linear stability theory for their modelling (Crow & Champagne Reference Crow and Champagne1971; Crighton & Gaster Reference Crighton and Gaster1976; Michalke Reference Michalke1984; Tam & Morris Reference Tam and Morris1985) and established the term ‘wavepacket’ to refer to them. Since those studies, the presence of wavepackets in unforced high-speed jets and their relationship with mixing-noise emission has been demonstrated both from experimental analyses (Juvé et al. Reference Juvé, Sunyach and Compte-Bellot1980; Guj et al. Reference Guj, Carley, Camussi and Ragni2003) and large-eddy simulations (Cavalieri et al. Reference Cavalieri, Daviller, Comte, Jordan, Tadmor and Gervais2011), together with the finding that the radiated sound is highly directional both for subsonic and perfectly expanded supersonic jets (Crighton & Huerre Reference Crighton and Huerre1990; Tam Reference Tam1995; Cavalieri et al. Reference Cavalieri, Jordan, Colonius and Gervais2012). In parallel, several works consolidated the ability of linear stability calculations to model wavepackets correctly, both in subsonic (Suzuki & Colonius Reference Suzuki and Colonius2006; Piot et al. Reference Piot, Casalis, Muller and Bailly2006; Gudmundsson & Colonius Reference Gudmundsson and Colonius2011; Cavalieri et al. Reference Cavalieri, Rodríguez, Jordan, Colonius and Gervais2013) as well as supersonic jets (Sinha et al. Reference Sinha, Rodríguez, Brès and Colonius2014). Although wavepackets constitute a relatively small fraction of the total fluctuation energy of the turbulent flow (Cavalieri et al. Reference Cavalieri, Rodríguez, Jordan, Colonius and Gervais2013), they nevertheless are known to be acoustically significant owing to their high spatio-temporal coherence with respect to the small turbulent scales (Jordan & Colonius Reference Jordan and Colonius2013).

Among the different linear stability theories employed for wavepacket modelling in single jets, the parabolised stability equations (PSE) have been broadly used. PSE were found to deliver a satisfactory agreement with both high-fidelity simulations and experiments for subsonic and supersonic jets at a small computational cost (Yen & Messersmith Reference Yen and Messersmith1999; Piot et al. Reference Piot, Casalis, Muller and Bailly2006; Ray, Cheung & Lele Reference Ray, Cheung and Lele2009; Gudmundsson & Colonius Reference Gudmundsson and Colonius2011; Rodríguez et al. Reference Rodríguez, Sinha, Brès and Colonius2012; Cavalieri et al. Reference Cavalieri, Rodríguez, Jordan, Colonius and Gervais2013; Rodríguez et al. Reference Rodríguez, Sinha, Brès and Colonius2013; Sinha et al. Reference Sinha, Rodríguez, Brès and Colonius2014; Breakey et al. Reference Breakey, Jordan, Cavalieri, Nogueira, Léon, Colonius and Rodríguez2017; Sasaki et al. Reference Sasaki, Cavalieri, Jordan, Schmidt, Colonius and Brès2017). These works have also served to identify and address some limitations of the PSE model for jet noise, which may be overcome by more computationally expensive approaches such as the one-way Navier–Stokes equations (Towne & Colonius Reference Towne and Colonius2015; Towne et al. Reference Towne, Rigas, Kamal, Pickering and Colonius2022) or resolvent analysis (Garnaud et al. Reference Garnaud, Lesshafft, Schmid and Huerre2013; Jeun, Nichols & Jovanović Reference Jeun, Nichols and Jovanović2016; Schmidt et al. Reference Schmidt, Towne, Rigas, Colonius and Brès2018; Cavalieri, Jordan & Lesshafft Reference Cavalieri, Jordan and Lesshafft2019). On the one hand, difficulties have been found in predicting the wavepacket properties at low frequencies and low azimuthal wavenumbers, conditions at which recent studies based on resolvent analysis have found non-modal growth to be important through the Orr and lift-up mechanisms (Tissot et al. Reference Tissot, Lajús, Cavalieri and Jordan2017; Schmidt et al. Reference Schmidt, Towne, Rigas, Colonius and Brès2018; Lesshafft et al. Reference Lesshafft, Semeraro, Jaunet, Cavalieri and Jordan2019; Nogueira et al. Reference Nogueira, Cavalieri, Jordan and Jaunet2019; Pickering et al. Reference Pickering, Rigas, Nogueira, Cavalieri, Schmidt and Colonius2020). Similarly, discrepancies have been encountered in the PSE description of wavepackets downstream of the region at which the growth of Kelvin–Helmholtz instabilities saturates, where locally parallel transient growth calculations and resolvent analyses reveal non-modal phenomena to be important and point to the role of nonlinear interactions in their activation (Jordan et al. Reference Jordan, Zhang, Lehnasch and Cavalieri2017; Tissot et al. Reference Tissot, Lajús, Cavalieri and Jordan2017; Schmidt et al. Reference Schmidt, Towne, Rigas, Colonius and Brès2018; Lesshafft et al. Reference Lesshafft, Semeraro, Jaunet, Cavalieri and Jordan2019). On the other hand, an underprediction of the amplitude of Mach-wave radiation has been observed, which can be attributed to the inherent limitations of the regularised marching problem, as described by Towne, Rigas & Colonius (Reference Towne, Rigas and Colonius2019). Despite these shortcomings, coherent structures in supersonic jets at the frequency range of interest in the study of mixing noise are dominated by Kelvin–Helmholtz instabilities (Pickering et al. Reference Pickering, Rigas, Nogueira, Cavalieri, Schmidt and Colonius2020), which are well modelled by PSE owing to their modal convective nature. For supersonic mixing layers featuring Kelvin–Helmholtz waves with high (supersonic) phase speed, the error in the PSE representation of Mach-wave radiation is found to be small (Towne et al. Reference Towne, Rigas and Colonius2019). These conditions are satisfied for most wavepacket calculations considered in this work.

Compared with single round jets, studies of wavepackets and their modelling in twin-jet systems are scarce in the literature, mainly due to the increased complexity of the flow field. The twin-jet mean flow is no longer axisymmetric, which prevents the introduction of azimuthal Fourier modes in both the modelling approaches and the experimental postprocessing techniques, and in turn requires inhomogeneity in at least two spatial directions. From the modelling point of view, Sedel’nikov (Reference Sedel’nikov1967) was the first to derive dispersion relationships for multi-jet configurations employing vortex sheets, although no solutions were determined. After this, only three works addressed the parallel-flow linear instability problem for twin jets before the last decade (Morris Reference Morris1990; Du Reference Du1993; Green & Crighton Reference Green and Crighton1997), making use of vortex sheet and finite-thickness models based on bipolar coordinate systems to study the inviscid instability of two axially homogeneous parallel jets. Morris (Reference Morris1990) established the classification of twin-jet fluctuations into four possible families according to the natural symmetries of the system. More recently, cross-plane local linear stability theory (Rodríguez et al. Reference Rodríguez, Jotkar and Gennaro2018; Nogueira & Edgington-Mitchell Reference Nogueira and Edgington-Mitchell2021; Rodríguez et al. Reference Rodríguez, Stavropoulos, Nogueira, Edgington-Mitchell and Jordan2023), along with plane-marching parabolised stability equations (PM-PSE) (Rodríguez et al. Reference Rodríguez, Jotkar and Gennaro2018; Rodríguez Reference Rodríguez2021) have enabled characterisation of the three-dimensional structure of the Kelvin–Helmholtz instabilities associated with mixing noise in the round twin-jet system. Rodríguez et al. (Reference Rodríguez, Jotkar and Gennaro2018) computed wavepacket models for subsonic twin jets employing local stability analyses and plane-marching PSE on a tailored twin-jet mean flow, consisting of the linear superposition of two single-jet analytical velocity fields fitted from hot-wire measurements. Similarly, Rodríguez (Reference Rodríguez2021) obtained wavepacket models for perfectly expanded supersonic twin jets via PM-PSE, once again using a tailored twin-jet mean flow fitted from large eddy simulation (LES) calculations. Nogueira & Edgington-Mitchell (Reference Nogueira and Edgington-Mitchell2021) characterised Kelvin–Helmholtz instabilities in a supersonic twin-jet system operating at underexpanded conditions via a locally parallel Floquet stability analysis, featuring a twin-jet mean flow obtained from planar particle image velocimetry (PIV) measurements revolved around the nozzle axes. Lastly, Rodríguez et al. (Reference Rodríguez, Stavropoulos, Nogueira, Edgington-Mitchell and Jordan2023) revisited the locally parallel stability of perfectly expanded twin jets using a vortex sheet and a finite-thickness model based on a tailored analytical mean flow, revealing that the coupling between the fluctuation fields of the two jets favours flapping motions over helical ones. These works employed simplified mean-flow models that account for linear interaction between the two jets. However, experimental mean-flow measurements and high-fidelity simulations indicate that the interaction is nonlinear, particularly in the case of closely spaced jets.

The aforementioned modelling efforts have predicted wavepackets analogous to those in single round jets, although with observable deviations in their spatial structure from the exact azimuthal Fourier modes characteristic of single round jets. The few experimental works aimed at their identification and characterisation in round twin-jet systems are very recent and focused on conditions at which screech is dominant (Kuo, Cluts & Samimy Reference Kuo, Cluts and Samimy2017; Knast et al. Reference Knast, Bell, Wong, Leb, Soria, Honnery and Edgington-Mitchell2018; Bell et al. Reference Bell, Cluts, Samimy, Soria and Edgington-Mitchell2021; Nogueira & Edgington-Mitchell Reference Nogueira and Edgington-Mitchell2021; Nogueira, Stavropoulos & Edgington-Mitchell Reference Nogueira, Stavropoulos and Edgington-Mitchell2021; Wong et al. Reference Wong, Stavropoulos, Beekman, Towne, Nogueira, Weightman and Edgington-Mitchell2023). Therefore, while the previously described investigations have provided physically sound wavepacket models for mixing noise, an assessment of their validity is still missing. Significant work has also focused on the study of the coupling and control of twin rectangular jets under screech conditions (Raman, Panickar & Chelliah Reference Raman, Panickar and Chelliah2012; Esfahani, Webb & Samimy Reference Esfahani, Webb and Samimy2021; Yeung, Schmidt & Brès Reference Yeung, Schmidt and Brès2022; Samimy et al. Reference Samimy, Webb, Esfahani and Leahy2023; Jeun, Wu & Lele Reference Jeun, Wu and Lele2024; Karnam et al. Reference Karnam, Ahn, Mihaescu, Saleem and Gutmark2025). However, no quantitative comparison between wavepacket models and experimental measurements currently exist for such rectangular configurations either.

A reduced number of recent works employed LES to study the flow dynamics in round twin jet configurations. Brès et al. (Reference Brès, Bose, Ham and Lele2014) and Gao, Xu & Li (Reference Gao, Xu and Li2016) simulated twin jets at under-expanded conditions with exit Mach number 1.36 and centre-to-centre spacing of

![]() $s=2.625D$

and

$s=2.625D$

and

![]() $2.25D$

, respectively; however, Brès et al. (Reference Brès, Bose, Ham and Lele2014) considered heated jets and fully turbulent boundary layers, while Gao et al. (Reference Gao, Xu and Li2016) simulated an isothermal jet with initially laminar shear layers. These differences lead to clear impact on the turbulent flow dynamics and radiated noise. Goparaju & Gaitonde (Reference Goparaju and Gaitonde2018) simulated a twin-jet system with

$2.25D$

, respectively; however, Brès et al. (Reference Brès, Bose, Ham and Lele2014) considered heated jets and fully turbulent boundary layers, while Gao et al. (Reference Gao, Xu and Li2016) simulated an isothermal jet with initially laminar shear layers. These differences lead to clear impact on the turbulent flow dynamics and radiated noise. Goparaju & Gaitonde (Reference Goparaju and Gaitonde2018) simulated a twin-jet system with

![]() $s = 2D$

at perfectly expanded conditions, Mach number 1.23 and initially laminar shear layers. Finally, Muthichur et al. (Reference Muthichur, Vempati, Hemchandra and Samanta2023) simulated two configurations, with

$s = 2D$

at perfectly expanded conditions, Mach number 1.23 and initially laminar shear layers. Finally, Muthichur et al. (Reference Muthichur, Vempati, Hemchandra and Samanta2023) simulated two configurations, with

![]() $s = 1.1D$

and

$s = 1.1D$

and

![]() $2D$

, Mach number 0.9, comparatively low Reynolds number and initially laminar shear layers. Similar to the case of experiments, the relative scarcity and sparsity of LES data for supersonic round twin jets has precluded a complete validation of the wavepacket models based on linear calculations.

$2D$

, Mach number 0.9, comparatively low Reynolds number and initially laminar shear layers. Similar to the case of experiments, the relative scarcity and sparsity of LES data for supersonic round twin jets has precluded a complete validation of the wavepacket models based on linear calculations.

This work contributes to the modelling of wavepackets in supersonic round twin jets in two new ways: (i) by employing a more accurate mean-flow representation based on the compressible RANS equations, which is used as an input for the plane-marching parabolised stability equations, and (ii) by performing the first quantitative comparisons of twin-jet wavepackets against coherent structures educed from experimental measurements. The three-dimensional RANS flows account for the nonlinear interactions between the mean flows of the two jets. By using them to inform the plane-marching PSE, the impact of the jet-to-jet mean flow interactions is incorporated in the wavepacket predictions. Here, RANS solutions are computed for perfectly expanded twin jets and validated by means of PIV measurements of the mean flow.

The validation of twin-jet wavepackets computed by PSE against experimental data is realised by application of spectral proper orthogonal decomposition (SPOD) to high-speed schlieren visualisations. Recent investigations focused on the study of screech in single (Edgington-Mitchell et al. Reference Edgington-Mitchell, Li, Liu, He, Wong, MacKenzie and Nogueira2022; Karnam, Saleem & Gutmark Reference Karnam, Saleem and Gutmark2023) and twin jets (Esfahani et al. Reference Esfahani, Webb and Samimy2021; Nogueira et al. Reference Nogueira, Stavropoulos and Edgington-Mitchell2021; Prasad et al. Reference Prasad, Gaitonde, Esfahani, Webb and Samimy2022; Wong et al. Reference Wong, Stavropoulos, Beekman, Towne, Nogueira, Weightman and Edgington-Mitchell2023; Karnam et al. Reference Karnam, Ahn, Mihaescu, Saleem and Gutmark2025) have educed organised structures at resonant frequencies by means of SPOD applied to schlieren measurements. In this case, the dynamics of the resonant mechanism feature a strong low-rank behaviour and a highly organised structure that is contained in the most energetic SPOD mode. The eduction of coherent structures from schlieren visualisations in perfectly expanded twin-jet systems is more challenging, as the schlieren images under non-screeching conditions are dominated by highly energetic, high-azimuthal wavenumber, small-scale vortical structures localised in the turbulent shear layer (Cavalieri et al. Reference Cavalieri, Rodríguez, Jordan, Colonius and Gervais2013). These structures dominate the fluctuation energy of the turbulence and complicate the use of techniques like proper orthogonal decomposition in obtaining a low-rank representation of wavepackets.

In this work, recent improvements (Prasad & Gaitonde Reference Prasad and Gaitonde2022; Padilla-Montero et al. Reference Padilla-Montero, Rodríguez, Jaunet and Jordan2024) that facilitate the extraction of mixing-noise-related coherent structures from schlieren images are adopted. These consist in performing spectral proper orthogonal decomposition on a filtered quantity derived from the schlieren images, instead of applying it to the schlieren fields directly. The quantity used is intimately related to the irrotational momentum potential field introduced by Doak (Reference Doak1989), which does not feature small-scale vortical fluctuations present in the schlieren visualisations. Through this methodology, coherent structures are extracted from the experimental datasets in the form of SPOD modes which can be compared with the PM-PSE wavepackets. To quantify the agreement between both, an alignment metric based on the projection of one SPOD field into one PM-PSE fluctuation field is proposed and evaluated for different frequencies and jet separations. Due to the line-of-sight integration implicit in the schlieren visualisations, only those fluctuations which are symmetric with respect to the plane containing both jets can be realised from the employed experimental set-up. The analysis and validation of wavepackets which are antisymmetric with respect to this plane are thus not considered in this work.

The remainder of this paper is organised as follows. Section 2 describes the twin-jet geometry and conditions considered for study. Section 3 presents the adopted modelling strategy for twin-jet wavepackets, formulating the governing equations as well as providing details on the numerical methodology employed for the computations. In § 4, the twin-jet experimental set-up is reported, including a description of the method employed for extracting coherent structures from the experimental data. Section 5 presents the obtained mean-flow solutions and wavepacket models. Particular characteristics of the twin-jet fluctuations for closely spaced jets are discussed, and their comparison against the experimentally educed structures is reviewed. Finally, concluding remarks are summarised in § 6.

2. Twin-jet configuration

Figure 1. Sketch representing the twin-jet configuration and the associated geometrical parameters:

![]() $(a)$

cross-stream plane (constant

$(a)$

cross-stream plane (constant

![]() $x$

);

$x$

);

![]() $(b)$

streamwise plane containing both jets axes at

$(b)$

streamwise plane containing both jets axes at

![]() $z = 0$

.

$z = 0$

.

The twin-jet configuration considered is sketched in figure 1. The jets are generated by two round convergent–divergent nozzles. The centre of each of the nozzles is located along the

![]() $y$

-axis, with

$y$

-axis, with

![]() $y = 0$

denoting the symmetry plane between the jets. Each nozzle exit is located at

$y = 0$

denoting the symmetry plane between the jets. Each nozzle exit is located at

![]() $x = 0$

and the spacing between the nozzles axes is denoted by

$x = 0$

and the spacing between the nozzles axes is denoted by

![]() $s$

. The interior nozzle geometry follows a truncated ideal contour (TIC) profile with an exit diameter of

$s$

. The interior nozzle geometry follows a truncated ideal contour (TIC) profile with an exit diameter of

![]() $D = 0.025$

m and an exit-to-throat area ratio of

$D = 0.025$

m and an exit-to-throat area ratio of

![]() $A_e / A_t = 1.225$

. The nozzle geometry is shown in figure 3.

$A_e / A_t = 1.225$

. The nozzle geometry is shown in figure 3.

The jets are generated under a fixed nozzle pressure ratio (NPR) corresponding to the perfectly expanded condition and a fixed total temperature of

![]() $T_{0} = 300$

K. The nozzle pressure ratio, defined as the ratio of the total pressure in the reservoir

$T_{0} = 300$

K. The nozzle pressure ratio, defined as the ratio of the total pressure in the reservoir

![]() $p_{0}$

to the ambient pressure

$p_{0}$

to the ambient pressure

![]() $p_\infty$

, is expressed in terms of the isentropic jet-exit Mach number

$p_\infty$

, is expressed in terms of the isentropic jet-exit Mach number

![]() $M_{\kern-1pt j}$

through the isentropic relation

$M_{\kern-1pt j}$

through the isentropic relation

![]() $p_{0} / p_\infty = [1 + 0.5(\gamma - 1) M_{\kern-1pt j}^2 ]^{\gamma /(\gamma - 1)}$

, where

$p_{0} / p_\infty = [1 + 0.5(\gamma - 1) M_{\kern-1pt j}^2 ]^{\gamma /(\gamma - 1)}$

, where

![]() $\gamma = 1.4$

denotes the ratio of specific heats. The jets are unheated and the flow acceleration within the nozzles results in jet static temperatures lower than the ambient temperature. The operating condition closest to the perfectly expanded regime has been calibrated experimentally by means of flow visualisation and corresponds to

$\gamma = 1.4$

denotes the ratio of specific heats. The jets are unheated and the flow acceleration within the nozzles results in jet static temperatures lower than the ambient temperature. The operating condition closest to the perfectly expanded regime has been calibrated experimentally by means of flow visualisation and corresponds to

![]() $M_{\kern-1pt j} = 1.54$

(NPR = 3.89). This operating condition is considered throughout the study. Two different nozzle separations are investigated:

$M_{\kern-1pt j} = 1.54$

(NPR = 3.89). This operating condition is considered throughout the study. Two different nozzle separations are investigated:

![]() $s/D = 1.76$

and

$s/D = 1.76$

and

![]() $s/D = 3$

. The first corresponds to the minimum distance allowed between the nozzles’ axes due to the size of the outer nozzle diameter. A strong interaction between jets is expected for

$s/D = 3$

. The first corresponds to the minimum distance allowed between the nozzles’ axes due to the size of the outer nozzle diameter. A strong interaction between jets is expected for

![]() $s/D = 1.76$

, while a weak interaction is expected for

$s/D = 1.76$

, while a weak interaction is expected for

![]() $s/D = 3$

. The system exhibits two symmetry planes: the plane that contains both jets (the

$s/D = 3$

. The system exhibits two symmetry planes: the plane that contains both jets (the

![]() $xy$

plane located at

$xy$

plane located at

![]() $z = 0$

) and the plane between the jets (the

$z = 0$

) and the plane between the jets (the

![]() $xz$

plane located at

$xz$

plane located at

![]() $y = 0$

).

$y = 0$

).

3. Modelling strategy

3.1. Mean flow

In the past, twin-jet mean-flow descriptions have been obtained using large eddy simulations (Brès et al. Reference Brès, Bose, Ham and Lele2014; Gao et al. Reference Gao, Xu and Li2016; Goparaju & Gaitonde Reference Goparaju and Gaitonde2018; Brès et al. Reference Brès, Yeung, Schmidt, Isfahani, Webb, Samimy and Colonius2021; Troyes & Vuillot Reference Troyes and Vuillot2022; Muthichur et al. Reference Muthichur, Vempati, Hemchandra and Samanta2023) or simplified approaches such as the axisymmetric revolution of twin-jet planar PIV measurements (Nogueira & Edgington-Mitchell Reference Nogueira and Edgington-Mitchell2021) or via a tailored twin-jet model, in which the twin-jet flow field is constructed by linearly superposing the velocity fields of two single jets. In the latter, the single-jet mean fields may come either from analytical models such as hyperbolic tangent profiles (Stavropoulos et al. Reference Stavropoulos, Mancinelli, Jordan, Jaunet, Weightman, Edgington-Mitchell and Nogueira2023; Rodríguez et al. Reference Rodríguez, Stavropoulos, Nogueira, Edgington-Mitchell and Jordan2023) or analytical Gaussian fittings to single-jet PIV measurements (Gudmundsson & Colonius Reference Gudmundsson and Colonius2011), hot-wire measurements (Rodríguez et al. Reference Rodríguez, Jotkar and Gennaro2018) or LES calculations (Rodríguez Reference Rodríguez2021).

One of the goals of this work is to model wavepackets in supersonic twin-jets by means of linear parabolised stability equations based on an accurate mean-flow representation. A mean-flow description that properly accounts for the nonlinear interactions between the jets at a mean-flow level is thus preferred. A LES calculation of the twin-jet configuration would provide one of the most accurate mean-flow predictions, as the actual jet dynamics and their mutual interactions are captured explicitly by LES and their imprint in the mean flow is retained by the time averaging operation. However, the computational cost of a properly resolved LES of the flows considered in this work, comprising complex geometries and very high Reynolds numbers, are considerable: of the order of thousands of cores and millions of CPU hours in a supercomputer (Brès et al. Reference Brès, Bose, Ham and Lele2014). Instead, three-dimensional compressible RANS calculations are used here to compute the mean flows, including the mean-flow jet interaction, with a good accuracy at a significantly reduced computational cost. The accuracy of the RANS solutions is assessed in § 5.1 by comparison to PIV measurements.

3.1.1. Governing equations

The twin-jet mean flow is modelled using the compressible RANS equations (also known as Favre-averaged Navier–Stokes equations), see e.g. Wilcox (Reference Wilcox2006):

\begin{align} \frac {\partial }{\partial t} \left ( \bar {\rho } \tilde {E} + \frac {\overline {\rho u_i'' u_i''}}{2} \right ) & + \frac {\partial }{\partial x_j} \left ( \bar {\rho } \tilde {u}_j \tilde {H} + \tilde {u}_j \frac {\overline {\rho u_i'' u_i''}}{2} \right ) = \frac {\partial }{\partial x_j} \left [ \tilde {u}_i \left ( \bar {\tau }_{\textit{ij}} - \overline {\rho u_i'' u_{\kern-1pt j}''} \right ) \right ]\\\nonumber & + \frac {\partial }{\partial x_j} \left ( \overline {\tau _{\textit{ij}} u_i''} - \frac {\overline {\rho u_i'' u_i'' u_{\kern-1pt j}''}}{2} \right ) - \frac {\partial }{\partial x_j} \left (-\bar {\kappa } \frac {\partial \tilde {T}}{\partial x_j} + c_p \overline {\rho T'' u_{\kern-1pt j}''} \right )\!, \\[-4pt] \nonumber \end{align}

\begin{align} \frac {\partial }{\partial t} \left ( \bar {\rho } \tilde {E} + \frac {\overline {\rho u_i'' u_i''}}{2} \right ) & + \frac {\partial }{\partial x_j} \left ( \bar {\rho } \tilde {u}_j \tilde {H} + \tilde {u}_j \frac {\overline {\rho u_i'' u_i''}}{2} \right ) = \frac {\partial }{\partial x_j} \left [ \tilde {u}_i \left ( \bar {\tau }_{\textit{ij}} - \overline {\rho u_i'' u_{\kern-1pt j}''} \right ) \right ]\\\nonumber & + \frac {\partial }{\partial x_j} \left ( \overline {\tau _{\textit{ij}} u_i''} - \frac {\overline {\rho u_i'' u_i'' u_{\kern-1pt j}''}}{2} \right ) - \frac {\partial }{\partial x_j} \left (-\bar {\kappa } \frac {\partial \tilde {T}}{\partial x_j} + c_p \overline {\rho T'' u_{\kern-1pt j}''} \right )\!, \\[-4pt] \nonumber \end{align}

where

![]() $u_i$

is the velocity component along the

$u_i$

is the velocity component along the

![]() $i$

th direction (with

$i$

th direction (with

![]() $i = 1,2,3$

),

$i = 1,2,3$

),

![]() $\rho$

is the density,

$\rho$

is the density,

![]() $p$

denotes pressure and

$p$

denotes pressure and

![]() $T$

the temperature. For a given instantaneous flow variable

$T$

the temperature. For a given instantaneous flow variable

![]() $q$

, the following decompositions are applied:

$q$

, the following decompositions are applied:

![]() $q = \bar {q} + q' = \tilde {q} + q''$

. The symbol

$q = \bar {q} + q' = \tilde {q} + q''$

. The symbol

![]() $\bar {\boldsymbol{\cdot }}$

indicates time averaging, whereas

$\bar {\boldsymbol{\cdot }}$

indicates time averaging, whereas

![]() $\tilde {\boldsymbol{\cdot }}$

denotes Favre averaging, defined as

$\tilde {\boldsymbol{\cdot }}$

denotes Favre averaging, defined as

The quantity

![]() $\bar {\tau }_{\textit{ij}}$

is the viscous stress tensor, given by

$\bar {\tau }_{\textit{ij}}$

is the viscous stress tensor, given by

where

![]() $\delta _{\textit{ij}}$

is the Kronecker delta. The quantity

$\delta _{\textit{ij}}$

is the Kronecker delta. The quantity

![]() $-\overline {\rho u_i'' u_{\kern-1pt j}''}$

denotes the Favre-averaged Reynolds stress tensor, which is modelled by means of the Boussinesq eddy-viscosity approximation. Here,

$-\overline {\rho u_i'' u_{\kern-1pt j}''}$

denotes the Favre-averaged Reynolds stress tensor, which is modelled by means of the Boussinesq eddy-viscosity approximation. Here,

![]() $\tilde {E}$

refers to the Favre-averaged total energy, defined as

$\tilde {E}$

refers to the Favre-averaged total energy, defined as

where

![]() $c_v$

represents the specific heat at constant volume, while

$c_v$

represents the specific heat at constant volume, while

![]() $\tilde {H}$

is the Favre-averaged total enthalpy, given by

$\tilde {H}$

is the Favre-averaged total enthalpy, given by

![]() $\tilde {H} = \tilde {E} + \bar {p}/\bar {\rho }$

. The quantity

$\tilde {H} = \tilde {E} + \bar {p}/\bar {\rho }$

. The quantity

![]() $(1/2) \overline {\rho u_i'' u_i''} = \bar {\rho } k$

denotes the kinetic energy of the turbulent fluctuations per unit volume. The transport coefficients representing the dynamic viscosity and thermal conductivity are respectively denoted by

$(1/2) \overline {\rho u_i'' u_i''} = \bar {\rho } k$

denotes the kinetic energy of the turbulent fluctuations per unit volume. The transport coefficients representing the dynamic viscosity and thermal conductivity are respectively denoted by

![]() $\bar {\mu }$

and

$\bar {\mu }$

and

![]() $\bar {\kappa }$

. The evolution of viscosity with temperature follows Sutherland’s law and

$\bar {\kappa }$

. The evolution of viscosity with temperature follows Sutherland’s law and

![]() $\bar {\kappa }$

is obtained from the assumption of a constant Prandtl number. Finally, the averaged perfect gas equation of state reads

$\bar {\kappa }$

is obtained from the assumption of a constant Prandtl number. Finally, the averaged perfect gas equation of state reads

where

![]() $R_g = 287$

J kg−1 K−1 is the specific gas constant.

$R_g = 287$

J kg−1 K−1 is the specific gas constant.

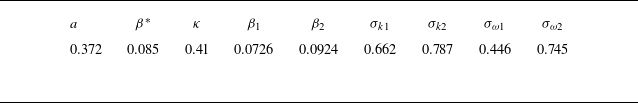

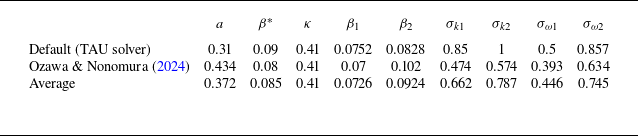

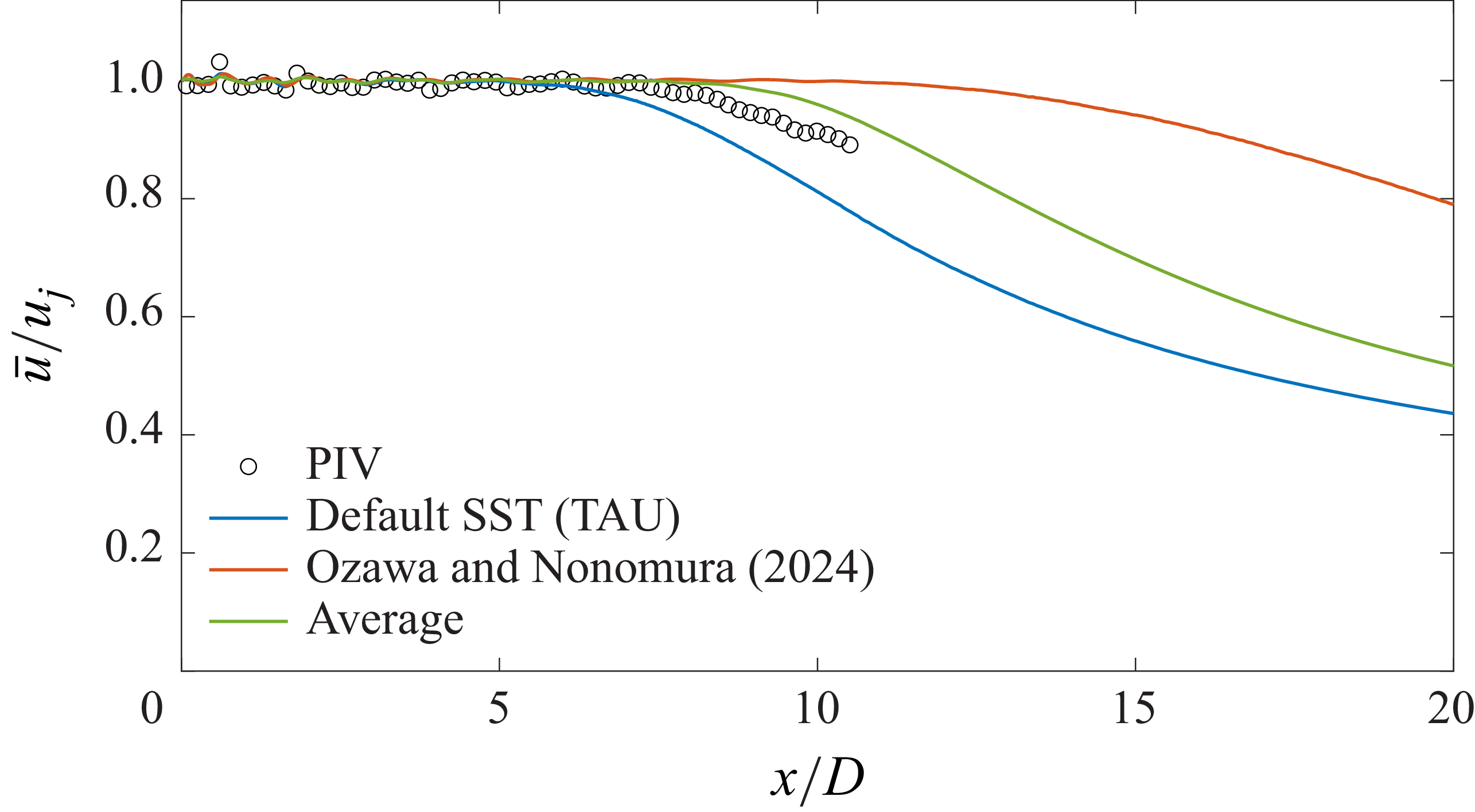

The two-equation shear stress transport (SST) turbulence model introduced by Menter (Reference Menter1994) is considered, together with the compressible mixing-layer correction proposed by Wilcox (Reference Wilcox2006, (5.83)). Modified values of the empirical constants of the turbulence model have been employed and are listed in table 1. These values were obtained by manual calibration following a linear interpolation between the original SST constants provided by Menter (Reference Menter1994) and the optimised constants recently obtained by Ozawa & Nonomura (Reference Ozawa and Nonomura2024) via data assimilation for a perfectly expanded jet. The selected values were found to yield a small mean squared error with respect to PIV mean-flow measurements with the employed solver. Appendix A provides a comparison between the mean-flow results obtained with the three different sets of empirical constants, which justifies the choice of parameters for this work.

Table 1. Employed values for the parameters of the Menter SST turbulence model. The same nomenclature as in Menter (Reference Menter1994) is followed.

The reference quantities employed for non-dimensionalisation are the nozzle-exit diameter

![]() $D$

and the free stream (ambient) flow conditions. The flow velocity components are non-dimensionalised with the free stream speed of sound

$D$

and the free stream (ambient) flow conditions. The flow velocity components are non-dimensionalised with the free stream speed of sound

![]() $c_\infty$

; the density with the respective free stream value

$c_\infty$

; the density with the respective free stream value

![]() $\rho _\infty$

; the pressure is made dimensionless with

$\rho _\infty$

; the pressure is made dimensionless with

![]() $\rho _\infty c_\infty ^2$

and the temperature with

$\rho _\infty c_\infty ^2$

and the temperature with

![]() $(\gamma - 1) T_\infty$

. The transport properties

$(\gamma - 1) T_\infty$

. The transport properties

![]() $\mu$

and

$\mu$

and

![]() $\kappa$

are non-dimensionalised with their respective free stream values.

$\kappa$

are non-dimensionalised with their respective free stream values.

3.1.2. Numerical methodology for the RANS calculations

Figure 2. Computational domain employed for the RANS calculation of the twin-jet flow field, including boundary conditions:

![]() $(a)$

cross-stream plane at a fixed streamwise location;

$(a)$

cross-stream plane at a fixed streamwise location;

![]() $(b)$

$(b)$

![]() $xy$

symmetry plane plane at

$xy$

symmetry plane plane at

![]() $z = 0$

. The dashed lines mark the nozzle exit geometry.

$z = 0$

. The dashed lines mark the nozzle exit geometry.

The RANS calculations are performed using the CFD solver TAU, developed by the German Aerospace Centre (DLR) (Schwamborn, Gerhold & Heinrich Reference Schwamborn, Gerhold and Heinrich2006). The numerical solution employs a second-order finite-volume method with an upwind discretisation scheme based on Roe’s approximate Riemann solver. A steady RANS solution is targeted, which is approached using a backward Euler implicit scheme for time integration.

Figure 2 shows the computational domain employed for the three-dimensional RANS calculations. Only one quarter of the twin-jet system is simulated, taking advantage of the two symmetry planes inherent in the geometry. The size of the domain is

![]() $L_x = 35D$

in the streamwise direction. In the

$L_x = 35D$

in the streamwise direction. In the

![]() $z$

direction, a size of

$z$

direction, a size of

![]() $L_z = 8D$

is used at the domain inflow, which extends linearly until

$L_z = 8D$

is used at the domain inflow, which extends linearly until

![]() $L_z = 14D$

at the domain outflow. Similarly, in the

$L_z = 14D$

at the domain outflow. Similarly, in the

![]() $y$

direction,

$y$

direction,

![]() $L_y = 9D$

is employed at the inflow, while

$L_y = 9D$

is employed at the inflow, while

![]() $L_y = 15D$

is used at the outflow. The inflow is located at the nozzle exit plane (

$L_y = 15D$

is used at the outflow. The inflow is located at the nozzle exit plane (

![]() $x/D = 0$

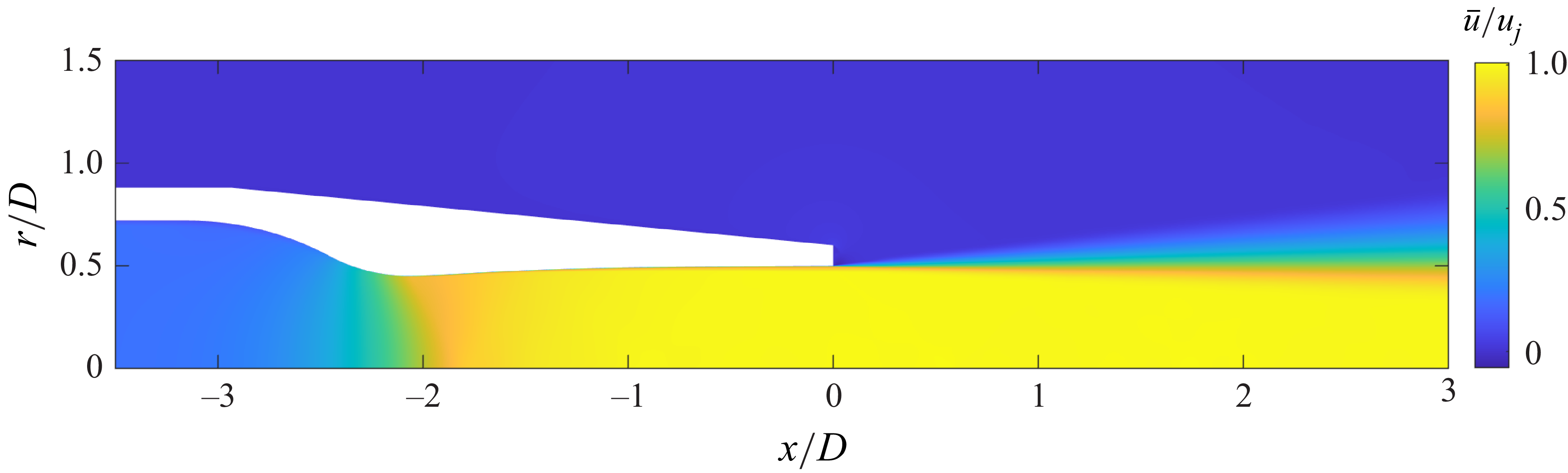

), where the nozzle exit flow field is imposed as a Dirichlet boundary condition. The flow at the nozzle exit is computed by means of an axisymmetric compressible RANS calculation of the entire nozzle flow field, including the boundary layer developing on the nozzle inner walls. This solution is shown in figure 3, which shows contours of the streamwise velocity field inside the nozzle and in the vicinity of the nozzle exit, and in figure 4, which illustrates the mean velocity and temperature profiles at the nozzle exit (

$x/D = 0$

), where the nozzle exit flow field is imposed as a Dirichlet boundary condition. The flow at the nozzle exit is computed by means of an axisymmetric compressible RANS calculation of the entire nozzle flow field, including the boundary layer developing on the nozzle inner walls. This solution is shown in figure 3, which shows contours of the streamwise velocity field inside the nozzle and in the vicinity of the nozzle exit, and in figure 4, which illustrates the mean velocity and temperature profiles at the nozzle exit (

![]() $x/D = 0$

) and slightly downstream of it (

$x/D = 0$

) and slightly downstream of it (

![]() $x/D = 0.05$

and

$x/D = 0.05$

and

![]() $0.1$

). The profile corresponding to

$0.1$

). The profile corresponding to

![]() $x/D = 0$

is the one imposed at the inflow of the twin-jet calculation.

$x/D = 0$

is the one imposed at the inflow of the twin-jet calculation.

Figure 3. Contours of mean streamwise velocity for the axisymmetric (single) jet calculation.

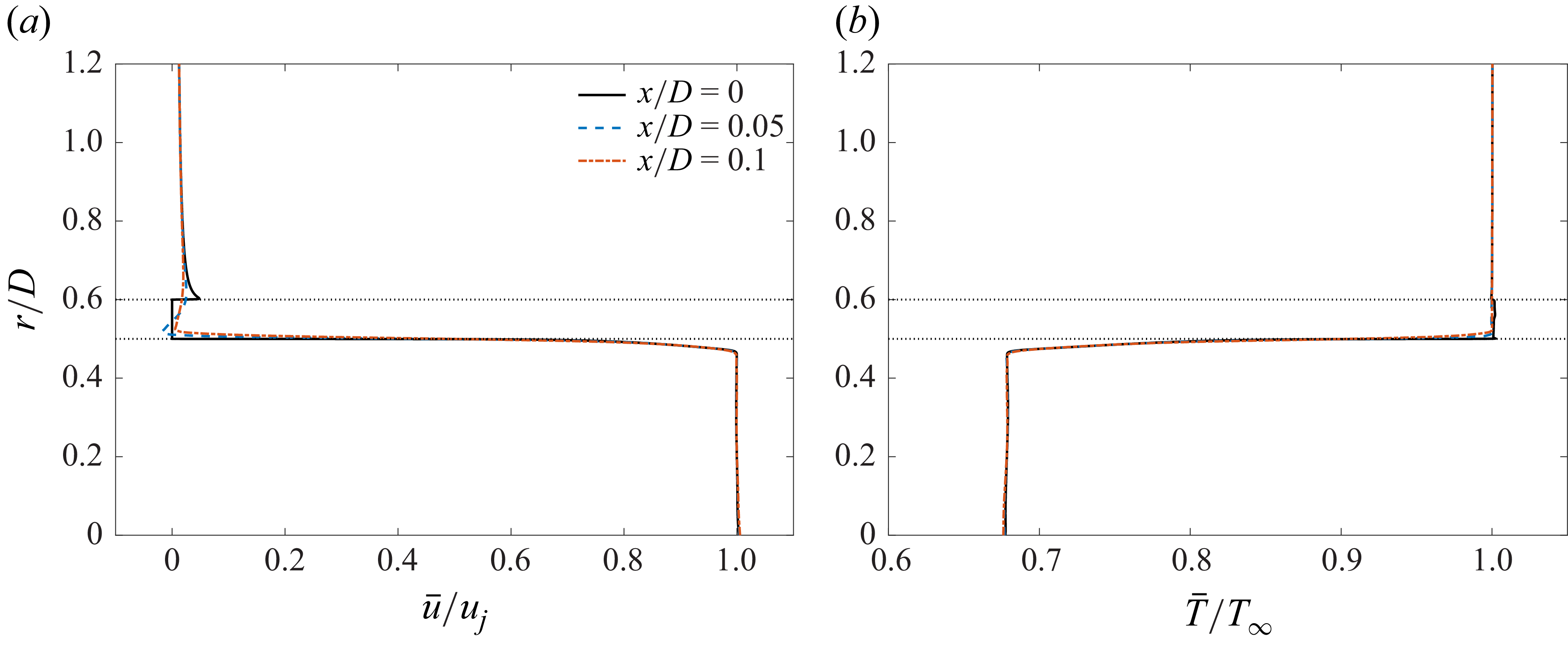

Figure 4. Mean flow profiles extracted at the nozzle exit (

![]() $x/D = 0$

) and slightly downstream of the nozzle exit (

$x/D = 0$

) and slightly downstream of the nozzle exit (

![]() $x/D = 0.05$

and

$x/D = 0.05$

and

![]() $x/D = 0.1$

) from the axisymmetric (single jet) calculation:

$x/D = 0.1$

) from the axisymmetric (single jet) calculation:

![]() $(a)$

streamwise velocity;

$(a)$

streamwise velocity;

![]() $(b)$

static temperature. The black dotted horizontal lines indicate the radial position of the nozzle lip walls.

$(b)$

static temperature. The black dotted horizontal lines indicate the radial position of the nozzle lip walls.

The single-jet axisymmetric RANS calculation uses a two-dimensional computational domain with a hybrid mesh mainly consisting of triangular cells, together with a structured region of quadrilateral cells located at the nozzle boundary layer. The cell size is calibrated such that

![]() $y^+ \approx 1$

to resolve the boundary layer developing on the nozzle walls, which feature an adiabatic thermal boundary condition. The resulting number of grid points across the boundary layer thickness is 50. A small co-flow of

$y^+ \approx 1$

to resolve the boundary layer developing on the nozzle walls, which feature an adiabatic thermal boundary condition. The resulting number of grid points across the boundary layer thickness is 50. A small co-flow of

![]() $M_{\textrm {co}} = 0.01$

is included in the far-field to replicate the experimental conditions.

$M_{\textrm {co}} = 0.01$

is included in the far-field to replicate the experimental conditions.

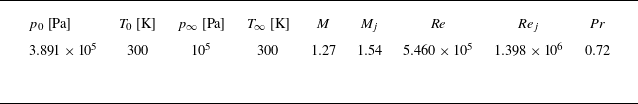

Table 2 reports the total and the ambient flow conditions employed for both the single-jet and the twin-jet RANS calculations. In addition to the jet-exit Mach number

![]() $M_{\kern-1pt j} = u_{\kern-1pt j}/c_{\kern-1pt j}$

, the acoustic jet Mach number is also reported, defined as

$M_{\kern-1pt j} = u_{\kern-1pt j}/c_{\kern-1pt j}$

, the acoustic jet Mach number is also reported, defined as

![]() $M = u_{\kern-1pt j}/c_\infty$

. Here,

$M = u_{\kern-1pt j}/c_\infty$

. Here,

![]() $u_{\kern-1pt j}$

is the jet-exit velocity and

$u_{\kern-1pt j}$

is the jet-exit velocity and

![]() $c_{\kern-1pt j}$

is the speed of sound corresponding to the jet-exit temperature (

$c_{\kern-1pt j}$

is the speed of sound corresponding to the jet-exit temperature (

![]() $T_{\kern-1pt j}$

), which is determined assuming an isentropic expansion. Two different Reynolds numbers are considered, the reference, acoustic Reynolds number used for non-dimensionalisation,

$T_{\kern-1pt j}$

), which is determined assuming an isentropic expansion. Two different Reynolds numbers are considered, the reference, acoustic Reynolds number used for non-dimensionalisation,

![]() $ \textit{Re} = \rho _\infty c_\infty D / \mu _\infty$

, and the jet-exit Reynolds number,

$ \textit{Re} = \rho _\infty c_\infty D / \mu _\infty$

, and the jet-exit Reynolds number,

![]() $ \textit{Re}_j = \rho_{\kern-1pt j} u_{\kern-1pt j} D / \mu_{\kern-1pt j}$

, where

$ \textit{Re}_j = \rho_{\kern-1pt j} u_{\kern-1pt j} D / \mu_{\kern-1pt j}$

, where

![]() $\rho_{\kern-1pt j}$

and

$\rho_{\kern-1pt j}$

and

![]() $\mu_{\kern-1pt j}$

respectively denote the density and the dynamic viscosity of the jet at the nozzle exit, which are also determined based on the isentropic flow relations. The Prandtl number is defined as

$\mu_{\kern-1pt j}$

respectively denote the density and the dynamic viscosity of the jet at the nozzle exit, which are also determined based on the isentropic flow relations. The Prandtl number is defined as

![]() $ \textit{Pr} = c_p \mu _\infty / \kappa _\infty$

, where

$ \textit{Pr} = c_p \mu _\infty / \kappa _\infty$

, where

![]() $c_p$

is the specific heat at constant pressure.

$c_p$

is the specific heat at constant pressure.

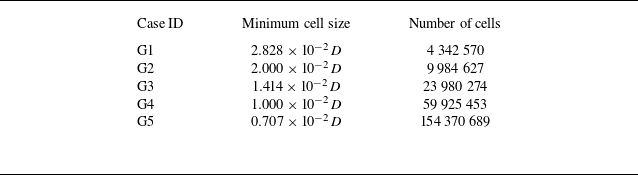

For the three-dimensional calculations, a fully unstructured tetrahedral mesh is used. It comprises successive refinement regions downstream of the nozzle exit following the growth of the mixing layers. A total of 154 million tetrahedral cells are employed for the case

![]() $s/D = 1.76$

and 174 million cells for

$s/D = 1.76$

and 174 million cells for

![]() $s/D = 3$

. The impact of the grid resolution of the RANS calculations on the predicted wavepackets is discussed in Appendix B. At the symmetry planes

$s/D = 3$

. The impact of the grid resolution of the RANS calculations on the predicted wavepackets is discussed in Appendix B. At the symmetry planes

![]() $z = 0$

and

$z = 0$

and

![]() $y = 0$

of the domain, symmetry boundary conditions are imposed. At the domain outflow, a subsonic outflow boundary condition is used, which imposes the ambient pressure

$y = 0$

of the domain, symmetry boundary conditions are imposed. At the domain outflow, a subsonic outflow boundary condition is used, which imposes the ambient pressure

![]() $p_\infty$

and extrapolates the other flow variables from the interior of the domain. At the far-field boundaries, a far-field inflow/outflow boundary condition is imposed that evaluates boundary fluxes via a characteristics method.

$p_\infty$

and extrapolates the other flow variables from the interior of the domain. At the far-field boundaries, a far-field inflow/outflow boundary condition is imposed that evaluates boundary fluxes via a characteristics method.

3.2. Formulation of the plane-marching parabolised stability equations

The PSE constitute one approach for studying the growth of linear and nonlinear disturbances in shear flows, and are well adapted when there exists a slow divergence of the mean-flow properties in the streamwise direction. They have been shown to deliver results comparable to direct numerical simulations for convectively unstable laminar and transitional flows (Bertolotti, Herbert & Spalart Reference Bertolotti, Herbert and Spalart1992; Chang et al. Reference Chang, Malik, Erlenbacher and Hussaini1993). PSE has been extensively used as a model for the spatial evolution of coherent structures in single round turbulent jets (wavepackets), yielding good agreement with coherent structures educed either from experiments or large eddy simulations (Yen & Messersmith Reference Yen and Messersmith1999; Piot et al. Reference Piot, Casalis, Muller and Bailly2006; Gudmundsson & Colonius Reference Gudmundsson and Colonius2011; Cavalieri et al. Reference Cavalieri, Rodríguez, Jordan, Colonius and Gervais2013; Rodríguez et al. Reference Rodríguez, Sinha, Brès and Colonius2013; Sinha et al. Reference Sinha, Rodríguez, Brès and Colonius2014; Sasaki et al. Reference Sasaki, Cavalieri, Jordan, Schmidt, Colonius and Brès2017). For perfectly expanded supersonic jets, screech does not occur and the sound generated at this condition is largely dominated by downstream-propagating Kelvin–Helmholtz waves. Owing to its lower computational cost and complexity compared with alternative techniques, PSE remains an attractive simplified modelling framework for this problem.

Following recent investigations (Rodríguez et al. Reference Rodríguez, Jotkar and Gennaro2018; Rodríguez Reference Rodríguez2021), wavepackets associated with mixing noise in perfectly expanded supersonic twin jets are modelled here using linear plane-marching parabolised stability equations (PM-PSE). This model is a direct extension of the classical PSE approach that accounts for mean flows featuring a strong inhomogeneity in the cross-stream planes, i.e.

![]() $y$

and

$y$

and

![]() $z$

(Broadhurst & Sherwin Reference Broadhurst and Sherwin2008).

$z$

(Broadhurst & Sherwin Reference Broadhurst and Sherwin2008).

Table 2. Flow conditions employed for the RANS calculations and resulting dimensionless parameters.

The plane-marching parabolised stability equations employed in this study are derived from the compressible Navier–Stokes equations. To formulate the PM-PSE linear stability problem, first, the instantaneous turbulent flow field is separated into a stationary mean-flow component

![]() $\bar {\boldsymbol{q}}$

and an unsteady fluctuation component

$\bar {\boldsymbol{q}}$

and an unsteady fluctuation component

![]() $\boldsymbol{q}'$

:

$\boldsymbol{q}'$

:

where

![]() $\boldsymbol{q} = [u,v,w,p,T]^{\mathrm{T}}$

is the vector of primitive flow variables, with

$\boldsymbol{q} = [u,v,w,p,T]^{\mathrm{T}}$

is the vector of primitive flow variables, with

![]() $u$

,

$u$

,

![]() $v$

and

$v$

and

![]() $w$

representing the velocity component along

$w$

representing the velocity component along

![]() $x$

,

$x$

,

![]() $y$

and

$y$

and

![]() $z$

, respectively. Next, the fluctuating component is expressed as a sum of discrete modes in frequency:

$z$

, respectively. Next, the fluctuating component is expressed as a sum of discrete modes in frequency:

where

![]() $\omega = 2\pi f$

denotes the angular frequency and

$\omega = 2\pi f$

denotes the angular frequency and

![]() $\textrm{c.c.}$

stands for the complex conjugate. The Fourier-transformed fluctuations in time

$\textrm{c.c.}$

stands for the complex conjugate. The Fourier-transformed fluctuations in time

![]() $\hat {\boldsymbol{q}}_\omega$

are then decomposed into a shape function (

$\hat {\boldsymbol{q}}_\omega$

are then decomposed into a shape function (

![]() $\tilde {\boldsymbol{q}}_\omega$

), which is assumed to undergo a slow variation along the streamwise direction

$\tilde {\boldsymbol{q}}_\omega$

), which is assumed to undergo a slow variation along the streamwise direction

![]() $x$

, and a wave function (

$x$

, and a wave function (

![]() $A_\omega$

), which is allowed to vary rapidly with

$A_\omega$

), which is allowed to vary rapidly with

![]() $x$

:

$x$

:

where the complex quantity

![]() $\alpha _\omega = \alpha _r + \mathrm{i} \alpha _i$

is the streamwise wavenumber for frequency

$\alpha _\omega = \alpha _r + \mathrm{i} \alpha _i$

is the streamwise wavenumber for frequency

![]() $\omega$

, for which a slow variation with

$\omega$

, for which a slow variation with

![]() $x$

is also required. The streamwise coordinate

$x$

is also required. The streamwise coordinate

![]() $x_0$

is the location where the PSE integration is initialised. In the context of this work, this is typically a cross-section close to the nozzle exit. The quantity

$x_0$

is the location where the PSE integration is initialised. In the context of this work, this is typically a cross-section close to the nozzle exit. The quantity

![]() $A_\omega (x_0)$

refers to the initial disturbance amplitude, which is arbitrary in a linear problem. Introducing (3.9) and (3.10) into the linearised Navier–Stokes equations and performing an order of magnitude analysis to neglect terms of order

$A_\omega (x_0)$

refers to the initial disturbance amplitude, which is arbitrary in a linear problem. Introducing (3.9) and (3.10) into the linearised Navier–Stokes equations and performing an order of magnitude analysis to neglect terms of order

![]() $1/Re^2$

, the following linear system is obtained:

$1/Re^2$

, the following linear system is obtained:

where the linear operators

![]() $\boldsymbol{L}$

and

$\boldsymbol{L}$

and

![]() $\boldsymbol{R}$

depend on the mean flow quantities and their first and second spatial derivatives, the complex spatial wavenumber

$\boldsymbol{R}$

depend on the mean flow quantities and their first and second spatial derivatives, the complex spatial wavenumber

![]() $\alpha _\omega$

and real frequency

$\alpha _\omega$

and real frequency

![]() $\omega$

, and the non-dimensional parameters

$\omega$

, and the non-dimensional parameters

![]() $ \textit{Re}$

,

$ \textit{Re}$

,

![]() $ \textit{Pr}$

and

$ \textit{Pr}$

and

![]() $\gamma$

. Additional details on the derivation of the operators

$\gamma$

. Additional details on the derivation of the operators

![]() $\boldsymbol{L}$

and

$\boldsymbol{L}$

and

![]() $\boldsymbol{R}$

can be found from Rodríguez et al. (Reference Rodríguez, Jotkar and Gennaro2018).

$\boldsymbol{R}$

can be found from Rodríguez et al. (Reference Rodríguez, Jotkar and Gennaro2018).

The ansatz (3.10) allows the spatial disturbance growth to be accounted for by either the shape function or the wave function, making the solution non-unique. To solve this ambiguity, a normalisation is imposed to eliminate the exponential dependence from

![]() $\tilde {\boldsymbol{q}}_\omega$

, which takes the form (Herbert Reference Herbert1997):

$\tilde {\boldsymbol{q}}_\omega$

, which takes the form (Herbert Reference Herbert1997):

where the superscript

![]() $^*$

denotes the complex conjugate and

$^*$

denotes the complex conjugate and

![]() $\varOmega$

is the cross-stream spatial domain in which the shape functions are defined for a given streamwise location.

$\varOmega$

is the cross-stream spatial domain in which the shape functions are defined for a given streamwise location.

3.2.1. Initial condition: locally parallel linear stability analysis

The PM-PSE system takes the form of a downstream-marching problem in the streamwise coordinate

![]() $x$

, which requires initial conditions at a given location

$x$

, which requires initial conditions at a given location

![]() $x_0$

. To obtain a consistent set of initial conditions for the PM-PSE problem, a locally parallel stability problem is derived from the PSE formulation following that of Rodríguez et al. (Reference Rodríguez, Sinha, Brès and Colonius2013). This is achieved by assuming that

$x_0$

. To obtain a consistent set of initial conditions for the PM-PSE problem, a locally parallel stability problem is derived from the PSE formulation following that of Rodríguez et al. (Reference Rodríguez, Sinha, Brès and Colonius2013). This is achieved by assuming that

![]() $\mathrm{d} \alpha _\omega / \mathrm{d} x = 0$

,

$\mathrm{d} \alpha _\omega / \mathrm{d} x = 0$

,

![]() $\partial \hat {\boldsymbol{q}}_\omega / \partial x = \mathrm{i} \alpha _\omega \tilde {\boldsymbol{q}}_\omega$

, and that, for a given streamwise station

$\partial \hat {\boldsymbol{q}}_\omega / \partial x = \mathrm{i} \alpha _\omega \tilde {\boldsymbol{q}}_\omega$

, and that, for a given streamwise station

![]() $x$

, the mean flow is locally parallel:

$x$

, the mean flow is locally parallel:

![]() $\partial \bar {\boldsymbol{q}} / \partial x = 0$

. These assumptions yield a generalised eigenvalue problem of the form:

$\partial \bar {\boldsymbol{q}} / \partial x = 0$

. These assumptions yield a generalised eigenvalue problem of the form:

For a given cross-stream plane at an initial location

![]() $x_0$

and a given frequency

$x_0$

and a given frequency

![]() $\omega$

, the solution of the eigenvalue problem (3.13) delivers a set of complex eigenvalues and their corresponding two-dimensional eigenfunctions (defined on the cross-stream plane). For unbounded mean flows like the present ones, classical linear stability theory (Mack Reference Mack1984; Balakumar & Malik Reference Balakumar and Malik1992) shows the existence of a fixed number of continuous branches, related to the uniform flow surrounding the jets, in addition to an indefinite number of discrete eigenmodes associated with localised mean-flow shear. For a single round jet, the different eigenmode families are described by Rodríguez et al. (Reference Rodríguez, Sinha, Brès and Colonius2013, Reference Rodríguez, Cavalieri, Colonius and Jordan2015). Identification of the discrete modes of interest (Kelvin–Helmholtz instabilities in this case) from the local stability spectrum is achieved by visual inspection of the corresponding two-dimensional amplitude functions.

$\omega$

, the solution of the eigenvalue problem (3.13) delivers a set of complex eigenvalues and their corresponding two-dimensional eigenfunctions (defined on the cross-stream plane). For unbounded mean flows like the present ones, classical linear stability theory (Mack Reference Mack1984; Balakumar & Malik Reference Balakumar and Malik1992) shows the existence of a fixed number of continuous branches, related to the uniform flow surrounding the jets, in addition to an indefinite number of discrete eigenmodes associated with localised mean-flow shear. For a single round jet, the different eigenmode families are described by Rodríguez et al. (Reference Rodríguez, Sinha, Brès and Colonius2013, Reference Rodríguez, Cavalieri, Colonius and Jordan2015). Identification of the discrete modes of interest (Kelvin–Helmholtz instabilities in this case) from the local stability spectrum is achieved by visual inspection of the corresponding two-dimensional amplitude functions.

3.2.2. Numerical methodology for the plane-marching PSE calculations

The numerical solution of both the marching problem and the local stability problem require the spatial discretisation of the two-dimensional linear operators

![]() $\boldsymbol{L}$

and

$\boldsymbol{L}$

and

![]() $\boldsymbol{R}$

. Following the studies by Gennaro et al. (Reference Gennaro, Rodríguez, Medeiros and Theofilis2013) and Rodríguez & Gennaro (Reference Rodríguez and Gennaro2017), finite-difference stencils of variable number of points are used in both

$\boldsymbol{R}$

. Following the studies by Gennaro et al. (Reference Gennaro, Rodríguez, Medeiros and Theofilis2013) and Rodríguez & Gennaro (Reference Rodríguez and Gennaro2017), finite-difference stencils of variable number of points are used in both

![]() $y$

- and

$y$

- and

![]() $z$

-directions. A seven-point stencil is used in the inner points. The stencil size is gradually reduced towards the boundary points to preserve the banded structure of the differentiation matrices. At the boundary points on each coordinate direction, four-point forward and backward stencils are used. This approach, employing high-order finite differences with banded differentiation matrices, leverages on the sparse storage and algebra employed, offering a good trade-off between convergence of results and computational cost. According to the mean-flow symmetries, only a quarter of the domain needs to be discretised. Consequently, a rectangular domain

$z$

-directions. A seven-point stencil is used in the inner points. The stencil size is gradually reduced towards the boundary points to preserve the banded structure of the differentiation matrices. At the boundary points on each coordinate direction, four-point forward and backward stencils are used. This approach, employing high-order finite differences with banded differentiation matrices, leverages on the sparse storage and algebra employed, offering a good trade-off between convergence of results and computational cost. According to the mean-flow symmetries, only a quarter of the domain needs to be discretised. Consequently, a rectangular domain

![]() $\varOmega = [0,y_{\infty }]\times [0,z_{\infty }]$

is used for the cross-stream planes. Two independent coordinate transformations (mappings) are used to concentrate grid points in the jet mixing regions. The following transformation is used in both

$\varOmega = [0,y_{\infty }]\times [0,z_{\infty }]$

is used for the cross-stream planes. Two independent coordinate transformations (mappings) are used to concentrate grid points in the jet mixing regions. The following transformation is used in both

![]() $y$

and

$y$

and

![]() $z$

directions:

$z$

directions:

where

![]() $\eta$

is the mapped coordinate in the physical domain (

$\eta$

is the mapped coordinate in the physical domain (

![]() $y$

or

$y$

or

![]() $z$

),

$z$

),

![]() $\xi$

is the associated coordinate in the computational domain (

$\xi$

is the associated coordinate in the computational domain (

![]() $\xi \in [0,1]$

);

$\xi \in [0,1]$

);

![]() $\eta _c$

is the location of the jet axis, where the discretisation is refined;

$\eta _c$

is the location of the jet axis, where the discretisation is refined;

![]() $\eta _\infty$

is the maximum coordinate and

$\eta _\infty$

is the maximum coordinate and

![]() $a$

is a real number that controls the intensity of the clustering of points. The remaining parameter

$a$

is a real number that controls the intensity of the clustering of points. The remaining parameter

![]() $b$

must be determined for each combination of

$b$

must be determined for each combination of

![]() $\eta _c$

,

$\eta _c$

,

![]() $\eta _\infty$

and

$\eta _\infty$

and

![]() $a$

so that

$a$

so that

![]() $\eta = 0$

for

$\eta = 0$

for

![]() $\xi = 0$

. In the present calculations, a square domain

$\xi = 0$

. In the present calculations, a square domain

![]() $\varOmega = [0,10] \times [0,10]$

is used, discretised with a spatial resolution of

$\varOmega = [0,10] \times [0,10]$

is used, discretised with a spatial resolution of

![]() $N_y \times N_z = 201 \times 201$

points. For each case, the values

$N_y \times N_z = 201 \times 201$

points. For each case, the values

![]() $a = 5$

,

$a = 5$

,

![]() $y_c/D = s/(2D)$

and

$y_c/D = s/(2D)$

and

![]() $z_c/D = 0.5$

are used. Mesh convergence tests, not reproduced here, ensure the numerical consistency of the results using these parameters.

$z_c/D = 0.5$

are used. Mesh convergence tests, not reproduced here, ensure the numerical consistency of the results using these parameters.

The Cartesian coordinate system allows for the use of standard finite differences for the independent differentiation on

![]() $y$

and

$y$

and

![]() $z$

, resulting in the differentiation matrices

$z$

, resulting in the differentiation matrices

![]() $\mathcal{D}_y$

and

$\mathcal{D}_y$

and

![]() $\mathcal{D}_z$

for first-order derivatives, and

$\mathcal{D}_z$

for first-order derivatives, and

![]() $\mathcal{D}_{\textit{yy}}$

and

$\mathcal{D}_{\textit{yy}}$

and

![]() $\mathcal{D}_{zz}$

for second-order derivatives. The same stencil is used for first- and second-order differentiation matrices, allowing for the control of the matrix structure required for efficiency of the sparse implementation. Explicit finite-difference formulae are employed for the second-order derivatives in

$\mathcal{D}_{zz}$

for second-order derivatives. The same stencil is used for first- and second-order differentiation matrices, allowing for the control of the matrix structure required for efficiency of the sparse implementation. Explicit finite-difference formulae are employed for the second-order derivatives in

![]() $\mathcal{D}_{\textit{yy}}$

and

$\mathcal{D}_{\textit{yy}}$

and

![]() $\mathcal{D}_{zz}$

. The cross-differentiation matrix is then obtained as

$\mathcal{D}_{zz}$

. The cross-differentiation matrix is then obtained as

![]() $\mathcal{D}_{yz} = \mathcal{D}_y \times \mathcal{D}_z$

.

$\mathcal{D}_{yz} = \mathcal{D}_y \times \mathcal{D}_z$

.

For a given cross-stream plane, four possible sets of boundary conditions can be imposed, leading to four solution families (Morris Reference Morris1990; Rodríguez et al. Reference Rodríguez, Jotkar and Gennaro2018, Reference Rodríguez, Stavropoulos, Nogueira, Edgington-Mitchell and Jordan2023): (i) symmetry conditions with respect to both

![]() $z = 0$

and

$z = 0$

and

![]() $y = 0$

(denoted by SS); (ii) symmetry with respect to

$y = 0$

(denoted by SS); (ii) symmetry with respect to

![]() $z = 0$

and antisymmetry with respect to

$z = 0$

and antisymmetry with respect to

![]() $y = 0$

(denoted by SA); (iii) antisymmetry with respect to

$y = 0$

(denoted by SA); (iii) antisymmetry with respect to

![]() $z = 0$

and symmetry with respect to

$z = 0$

and symmetry with respect to

![]() $y = 0$

(denoted by AS); (iv) antisymmetry conditions with respect to both

$y = 0$

(denoted by AS); (iv) antisymmetry conditions with respect to both

![]() $z = 0$

and

$z = 0$

and

![]() $y = 0$

(denoted by AA). The symmetry imposition is accomplished through appropriate sets of symmetry and antisymmetry boundary conditions on the perturbation quantities, which are implemented through the corresponding Neumann and Dirichlet conditions. These are summarised as follows (refer to figure 2):

$y = 0$

(denoted by AA). The symmetry imposition is accomplished through appropriate sets of symmetry and antisymmetry boundary conditions on the perturbation quantities, which are implemented through the corresponding Neumann and Dirichlet conditions. These are summarised as follows (refer to figure 2):

\begin{eqnarray} \begin{array}{ll} \mbox{Symmetry on } y=0, & \dfrac {\partial \hat {u}}{\partial y} = \dfrac {\partial \hat {w}}{\partial y} = \dfrac {\partial \hat {p}}{\partial y} = \dfrac {\partial \hat {T}}{\partial y} = \hat {v} = 0; \\ \mbox{Antisymmetry on } y=0, & \hat {u} = \hat {w} = \hat {p} = \hat {T} = \dfrac {\partial \hat {v}}{\partial y} = 0; \\ \mbox{Symmetry on } z=0, & \dfrac {\partial \hat {u}}{\partial z} = \dfrac {\partial \hat {v}}{\partial z} = \dfrac {\partial \hat {p}}{\partial z} = \dfrac {\partial \hat {T}}{\partial z} = \hat {w} = 0; \\ \mbox{Antisymmetry on } z=0, & \hat {u} = \hat {v} = \hat {p} = \hat {T} = \dfrac {\partial \hat {w}}{\partial z} = 0. \\ \end{array} \end{eqnarray}

\begin{eqnarray} \begin{array}{ll} \mbox{Symmetry on } y=0, & \dfrac {\partial \hat {u}}{\partial y} = \dfrac {\partial \hat {w}}{\partial y} = \dfrac {\partial \hat {p}}{\partial y} = \dfrac {\partial \hat {T}}{\partial y} = \hat {v} = 0; \\ \mbox{Antisymmetry on } y=0, & \hat {u} = \hat {w} = \hat {p} = \hat {T} = \dfrac {\partial \hat {v}}{\partial y} = 0; \\ \mbox{Symmetry on } z=0, & \dfrac {\partial \hat {u}}{\partial z} = \dfrac {\partial \hat {v}}{\partial z} = \dfrac {\partial \hat {p}}{\partial z} = \dfrac {\partial \hat {T}}{\partial z} = \hat {w} = 0; \\ \mbox{Antisymmetry on } z=0, & \hat {u} = \hat {v} = \hat {p} = \hat {T} = \dfrac {\partial \hat {w}}{\partial z} = 0. \\ \end{array} \end{eqnarray}

The local stability problem is solved by means of a parallelised sparse implementation of the shift-and-invert Arnoldi algorithm (Arnoldi Reference Arnoldi1951), which employs the MUMPS library (Amestoy et al. Reference Amestoy, Duff, L’Excellent and Koster2001) for solution of the linear systems of equations. The implicit Euler scheme is used to march the PM-PSE solution downstream. The resulting linear system of equations at each streamwise station is also solved via a parallel implementation using MUMPS. To adjust the value of

![]() $\alpha$

so that the normalisation condition (3.12) is satisfied, the solution of the linear system is iterated together with the following relation:

$\alpha$

so that the normalisation condition (3.12) is satisfied, the solution of the linear system is iterated together with the following relation:

\begin{align} \alpha ^{(k+1)}_{\omega , j+1} = \alpha ^{(k)}_{\omega , j+1} - \frac {\mathrm{i}}{\Delta x} \frac {\iint _{\varOmega } \tilde {\boldsymbol {q}}_{\omega , j+1}^* (\tilde {\boldsymbol {q}}_{\omega , j+1} - \tilde {\boldsymbol {q}}_{\omega , j}) \,\mathrm{d}y \,\mathrm{d}z}{\iint _\varOmega \tilde {\boldsymbol {q}}_{\omega , j+1}^* \tilde {\boldsymbol {q}}_{\omega , j+1} \,\mathrm{d}y\, \mathrm{d}z}, \end{align}

\begin{align} \alpha ^{(k+1)}_{\omega , j+1} = \alpha ^{(k)}_{\omega , j+1} - \frac {\mathrm{i}}{\Delta x} \frac {\iint _{\varOmega } \tilde {\boldsymbol {q}}_{\omega , j+1}^* (\tilde {\boldsymbol {q}}_{\omega , j+1} - \tilde {\boldsymbol {q}}_{\omega , j}) \,\mathrm{d}y \,\mathrm{d}z}{\iint _\varOmega \tilde {\boldsymbol {q}}_{\omega , j+1}^* \tilde {\boldsymbol {q}}_{\omega , j+1} \,\mathrm{d}y\, \mathrm{d}z}, \end{align}

where

![]() $k$

is the iteration index,

$k$

is the iteration index,

![]() $j+1$

refers to the solution at the next downstream streamwise position,

$j+1$

refers to the solution at the next downstream streamwise position,

![]() $j$

refers to the current streamwise station and

$j$

refers to the current streamwise station and

![]() $\Delta x = x_{j+1} - x_j$

is the streamwise step size. The iteration continues until

$\Delta x = x_{j+1} - x_j$

is the streamwise step size. The iteration continues until

![]() $\alpha _\omega$

is converged up to a relative error

$\alpha _\omega$

is converged up to a relative error

![]() $|\alpha ^{(k+1)}_\omega -\alpha ^{(k)}_\omega |/|\alpha ^{(k+1)}_\omega | \lt 10^{-4}$

.

$|\alpha ^{(k+1)}_\omega -\alpha ^{(k)}_\omega |/|\alpha ^{(k+1)}_\omega | \lt 10^{-4}$

.

For all the calculations presented in this work, the locally parallel stability problem is solved at

![]() $x_0 = 0.75 D$

. This is an arbitrary location relatively close to the nozzle lip where robust results are obtained. Computing the initial marching conditions in the close proximity of the nozzle lip would be influenced by the sharp gradients of the mean flow, as shown in figure 4, requiring a more refined cross-plane mesh. The streamwise step size

$x_0 = 0.75 D$

. This is an arbitrary location relatively close to the nozzle lip where robust results are obtained. Computing the initial marching conditions in the close proximity of the nozzle lip would be influenced by the sharp gradients of the mean flow, as shown in figure 4, requiring a more refined cross-plane mesh. The streamwise step size

![]() $\Delta x \approx 0.2 D$

is used for all cases. This value was determined empirically as the smallest one for which the PSE marching does not present instability issues for the most critical

$\Delta x \approx 0.2 D$

is used for all cases. This value was determined empirically as the smallest one for which the PSE marching does not present instability issues for the most critical

![]() $St=0.1$

cases. Stabilisation procedures, such as the one introduced by Andersson, Henningson & Hanifi (Reference Andersson, Henningson and Hanifi1998), are not employed.

$St=0.1$

cases. Stabilisation procedures, such as the one introduced by Andersson, Henningson & Hanifi (Reference Andersson, Henningson and Hanifi1998), are not employed.

4. Experimental set-up

Figure 5. Experimental set-up and elements of the high-speed schlieren measurement system.

High-speed schlieren visualisations and low-speed PIV measurements of the twin-jet flow field have been performed at the T200 wind tunnel facility of the PROMETEE platform of Institut Pprime (CNRS – Université de Poitiers – ISAE-ENSMA), France. The set-up is shown in figure 5. The flow is generated using a

![]() $200$

bar compressed air network that can reach operational conditions up to an isentropic Mach number

$200$

bar compressed air network that can reach operational conditions up to an isentropic Mach number

![]() $M_{\kern-1pt j} = 2$

for the twin-jet configuration. A heating system based on a series of tanks with heated nickel balls is used to increase and maintain the total temperature of the air reaching the nozzles. The left image of figure 5 shows the twin-jet system situated in an anechoic chamber.

$M_{\kern-1pt j} = 2$

for the twin-jet configuration. A heating system based on a series of tanks with heated nickel balls is used to increase and maintain the total temperature of the air reaching the nozzles. The left image of figure 5 shows the twin-jet system situated in an anechoic chamber.

Schlieren visualisations are obtained using a classical Z-type set-up, for which some components are also illustrated in figure 5. A continuous light source is generated by a 60 W LED, which passes through an aperture that prevents direct light from the source to enter the test section. Two parabolic mirrors, each 30 cm in diameter and with a 3 m focal length, produce a collimated light beam that travels through the test section in the

![]() $z$

direction, according to the reference frame in figure 1. To form a Z-shaped optical path that allows for a more compact experimental set-up, two additional flat mirrors, each 12 cm in diameter, are incorporated. A vertical knife edge is positioned at the focal length of the second parabolic mirror, making the resulting light intensity field recovered in the schlieren images proportional to the streamwise density gradients in the flow.

$z$

direction, according to the reference frame in figure 1. To form a Z-shaped optical path that allows for a more compact experimental set-up, two additional flat mirrors, each 12 cm in diameter, are incorporated. A vertical knife edge is positioned at the focal length of the second parabolic mirror, making the resulting light intensity field recovered in the schlieren images proportional to the streamwise density gradients in the flow.

A Phantom v2640 high-speed camera was used to record the images. For the current datasets,

![]() $N_s = 30\,000$

instantaneous snapshots were recorded at a sampling frequency of

$N_s = 30\,000$

instantaneous snapshots were recorded at a sampling frequency of

![]() $f_s = 68$

kHz (

$f_s = 68$

kHz (

![]() $\Delta t = 1.47 \times 10^{-5}$

s) and a spatial resolution of

$\Delta t = 1.47 \times 10^{-5}$

s) and a spatial resolution of

![]() $352 \times 512$

pixels. The Strouhal number corresponding to the recording Nyquist frequency is

$352 \times 512$

pixels. The Strouhal number corresponding to the recording Nyquist frequency is

![]() $St_{\textit{Ny}} = f_s D / (2 u_{\kern-1pt j}) = 1.93$

(

$St_{\textit{Ny}} = f_s D / (2 u_{\kern-1pt j}) = 1.93$

(

![]() $2 \Delta t u_{\kern-1pt j} / D = 0.52$

), which is high enough to resolve the coherent structures associated with mixing noise, which develop in the range

$2 \Delta t u_{\kern-1pt j} / D = 0.52$

), which is high enough to resolve the coherent structures associated with mixing noise, which develop in the range

![]() $St \approx [0.1, 1]$

for supersonic jets (Sinha et al. Reference Sinha, Rodríguez, Brès and Colonius2014). The total number of convective time units spanned by the recording is

$St \approx [0.1, 1]$

for supersonic jets (Sinha et al. Reference Sinha, Rodríguez, Brès and Colonius2014). The total number of convective time units spanned by the recording is

![]() $\tau c_{\textit{KH}} / D \approx 5440$

, where

$\tau c_{\textit{KH}} / D \approx 5440$

, where

![]() $\tau = \Delta t N_s = 0.44$

s denotes the total recording time and

$\tau = \Delta t N_s = 0.44$

s denotes the total recording time and

![]() $c_{\textit{KH}} = 0.7u_{\kern-1pt j}$

is the estimated convective velocity of Kelvin–Helmholtz structures. Figure 6

$c_{\textit{KH}} = 0.7u_{\kern-1pt j}$

is the estimated convective velocity of Kelvin–Helmholtz structures. Figure 6

![]() $(a{,}b$

) illustrates two instantaneous schlieren snapshots respectively recorded for

$(a{,}b$

) illustrates two instantaneous schlieren snapshots respectively recorded for

![]() $s/D = 1.76$

and

$s/D = 1.76$

and

![]() $s/D = 3$

. The mean schlieren fields resulting from averaging all the instantaneous snapshots are also shown in figure 6

$s/D = 3$

. The mean schlieren fields resulting from averaging all the instantaneous snapshots are also shown in figure 6

![]() $(c{,}d$

). Due to the high sensitivity of the perfectly expanded condition to imperfections in the nozzle geometry, weak residual shock and expansion waves remain in the flow. A small discrepancy is present between the two jets, which originates from small machining inaccuracies between the two nozzles. The weak asymmetry introduced by this difference between both jets has not been found to have a meaningful impact on the coherent fluctuations supported by the system and their eduction based on their symmetric and antisymmetric behaviour, and hence does not affect the validation process of the wavepacket models.

$(c{,}d$

). Due to the high sensitivity of the perfectly expanded condition to imperfections in the nozzle geometry, weak residual shock and expansion waves remain in the flow. A small discrepancy is present between the two jets, which originates from small machining inaccuracies between the two nozzles. The weak asymmetry introduced by this difference between both jets has not been found to have a meaningful impact on the coherent fluctuations supported by the system and their eduction based on their symmetric and antisymmetric behaviour, and hence does not affect the validation process of the wavepacket models.

PIV measurements are performed to obtain a mean velocity field to validate the RANS calculations. The PIV measurement system consists of two side-by-side LaVision Imager LX 16 M cameras which record 500 instantaneous, high-resolution images (dual frames) at a sampling frequency of 4.4 Hz and at a resolution of 16 megapixels each, employing a time delay between frames of 1.5

![]() $\unicode {x03BC}$

s. The flow is seeded with pressurised glycerine vapour in the settling chamber, prior to nozzle expansion, while the ambient region is seeded with a fog generator employing a glycerine–water mixture. A double-pulse Nd-YAG laser operating at 532 nm is used, which illuminates the seeded particles in the

$\unicode {x03BC}$

s. The flow is seeded with pressurised glycerine vapour in the settling chamber, prior to nozzle expansion, while the ambient region is seeded with a fog generator employing a glycerine–water mixture. A double-pulse Nd-YAG laser operating at 532 nm is used, which illuminates the seeded particles in the

![]() $z = 0$

plane, enabling measurement of the mean-flow velocity in the symmetry plane containing the two jets. The PIV measurement window covers the region

$z = 0$