Relatively free trade has long been a cornerstone of the liberal international order established after World War II.Footnote 1 Anchored by the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) and subsequently the World Trade Organization (WTO), the international trade system is designed to facilitate the cross-border movement of goods and services via low tariffs and a common set of rules. While countries have largely adhered to these rules so far, the second Trump administration, beginning in January 2025, has adopted a trade policy that upends these very principles. Not only did it impose duties on imports from the United States’ principal geopolitical rival, China, but traditional allies have also found themselves subject to both blanket and sector-specific tariffs. The resulting cycle of retaliation and renegotiation appears to imperil the system’s foundations. Has the postwar trading order, which underpinned decades of unprecedented globalization, eventually run its course?

Pundits indeed describe Trump’s trade policy as the “death knell of the ailing World Trade Organization”Footnote 2 and argue that the “world trading system is dying.”Footnote 3 This is in line with scholars’ warnings that the system was at risk even before 2025’s upheaval, especially because of declining US interest in upholding the rules of the game.Footnote 4 Goldstein and Gulotty, for instance, trace waning US support to inadequate social protections for workers displaced by trade.Footnote 5 In their view, US support for the international trade system has always been fragile because internationally oriented business interests were the sole bulwark of liberal trade. Given the importance of the United States in international trade, the entire regime could collapse without US political backing.

We contend, however, that predictions of a lasting US retreat from international trade—and, by extension, of the collapse of the international trading system—are premature. Our argument rests on the claim that, historically, US trade policy has never conformed to a single logic for a considerable period. The notion that the United States has consistently spearheaded free trade does not withstand scrutiny. Instead, at most times, US trade policy embodies an eclectic approach—a series of compromises and contradictions that defy easy labels of purely protectionist or liberal. This means that the international trading system has acquired resilience to withstand pressures and challenges from the United States as well as other trading entities. While acknowledging the unprecedented character of US trade politics under Trump, a historical perspective shows why the system’s demise is far from inevitable.

US Trade Policy Under Trump II

Immediately after taking office, the second Trump administration escalated tariffs across multiple partners and product lines.Footnote 6 Already on 20 January 2025, the president announced a 25 percent tariff on Canadian and Mexican imports. Less than two weeks later, on 1 February, he signed an executive order adding a 10 percent across-the-board tariff on Chinese goods. The announcement of a 25 percent surcharge on all foreign steel and aluminum followed soon after. On 2 April, the White House proclaimed “Liberation Day” and imposed a baseline 10 percent tariff on all imports plus country-specific “reciprocal” rates that could reach 50 percent. Within forty-eight hours, China mirrored those duties. As both countries escalated further, bilateral tariffs soon soared to unprecedented levels. On 9 April, amid market turmoil, the administration paused most of the new tariffs to allow for negotiations. As part of these negotiations, the European Union reached a deal that limited most US tariffs to 15 percent in exchange for some European concessions.

On 31 July, a new executive order replaced the blanket baseline from 2 April with revised country schedules. In parallel, the administration signaled further tariffs on furniture, pharmaceuticals, and semiconductors. In late August, the United States then ended the long-standing exemption for small parcels, extending tariffs to e-commerce packages. As a result of the various tariff increases, the United States’ estimated effective tariff rate increased from 2.3 percent in 2024 to 16 percent in August 2025.Footnote 7

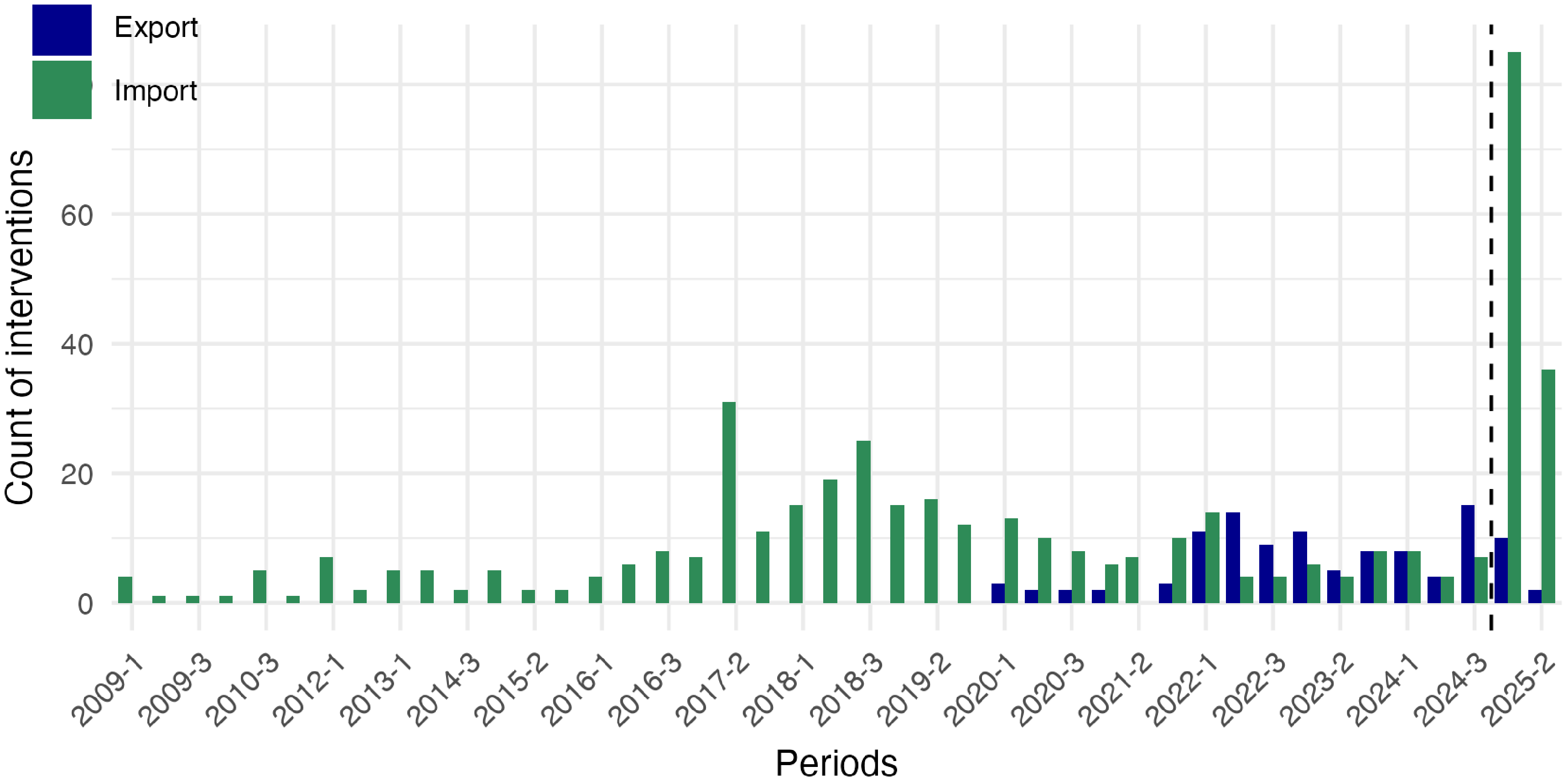

Figure 1 uses data from Global Trade Alert to put these measures into context.Footnote 8 It separately shows the number of import restrictionsFootnote 9 and export restrictionsFootnote 10 announced by the United States in the period from January 2009 to August 2025. We show only discriminatory measures, that is, measures that hurt foreign countries (“red measures” in the Global Trade Alert terminology). By aggregating measures into four-month terms, we can compare the numbers for the second Trump administration (reported under 2025-1 and 2025-2) to the numbers for the same periods in the previous years.Footnote 11 The resulting figure shows a clear spike in import restrictions in 2025, while export restrictions emerged only in 2020 and have remained relatively constant since 2022.Footnote 12

FIGURE 1. Import and export restrictions (United States, 2009–2025)

Notes: The dashed vertical line indicates the start of the second Trump administration. Periods: (1) January to April, (2) May to August, (3) September to December. (Source: Authors’ calculations based on global trade alert data ending in August 2025).

The move toward more protectionism visible in Figure 1 represents an unprecedented challenge to the international trading system. The current US administration has abandoned even rhetorical commitment to open markets. US commitments made within the WTO framework are being systematically ignored. The US policies also undermine the most-favored-nation (MFN) principle, which has served as the cornerstone of the multilateral trading system since its inception. But also less central norms, such as the development principle of special and differential treatment—which calls for nonreciprocal market access arrangements for least developed countries—are being disregarded. This comprehensive assault on established trade norms represents a qualitative shift compared to what we have seen since World War II.

The Trump administration has offered multiple rationales for its approach to trade policy. These include using tariffs as bargaining tools to secure concessions from foreign countries on specific issues such as fentanyl trafficking, bringing manufacturing operations back to the United States, reducing the trade deficit, increasing tariff revenue to ease the federal budget deficit, and addressing national security concerns. However, these justifications often contradict each other. For instance, if tariffs are primarily intended as temporary bargaining instruments, they cannot simultaneously achieve the goal of permanently reshoring manufacturing. Similarly, when tariffs are set so high that they severely limit imports, they will hardly generate government revenue. And tariffs that hit allies generally do not enhance national security. These logical inconsistencies suggest that these rationales cannot be used to assess the long-term implications of current developments for the international trading system.

Two Trade Policy Dimensions

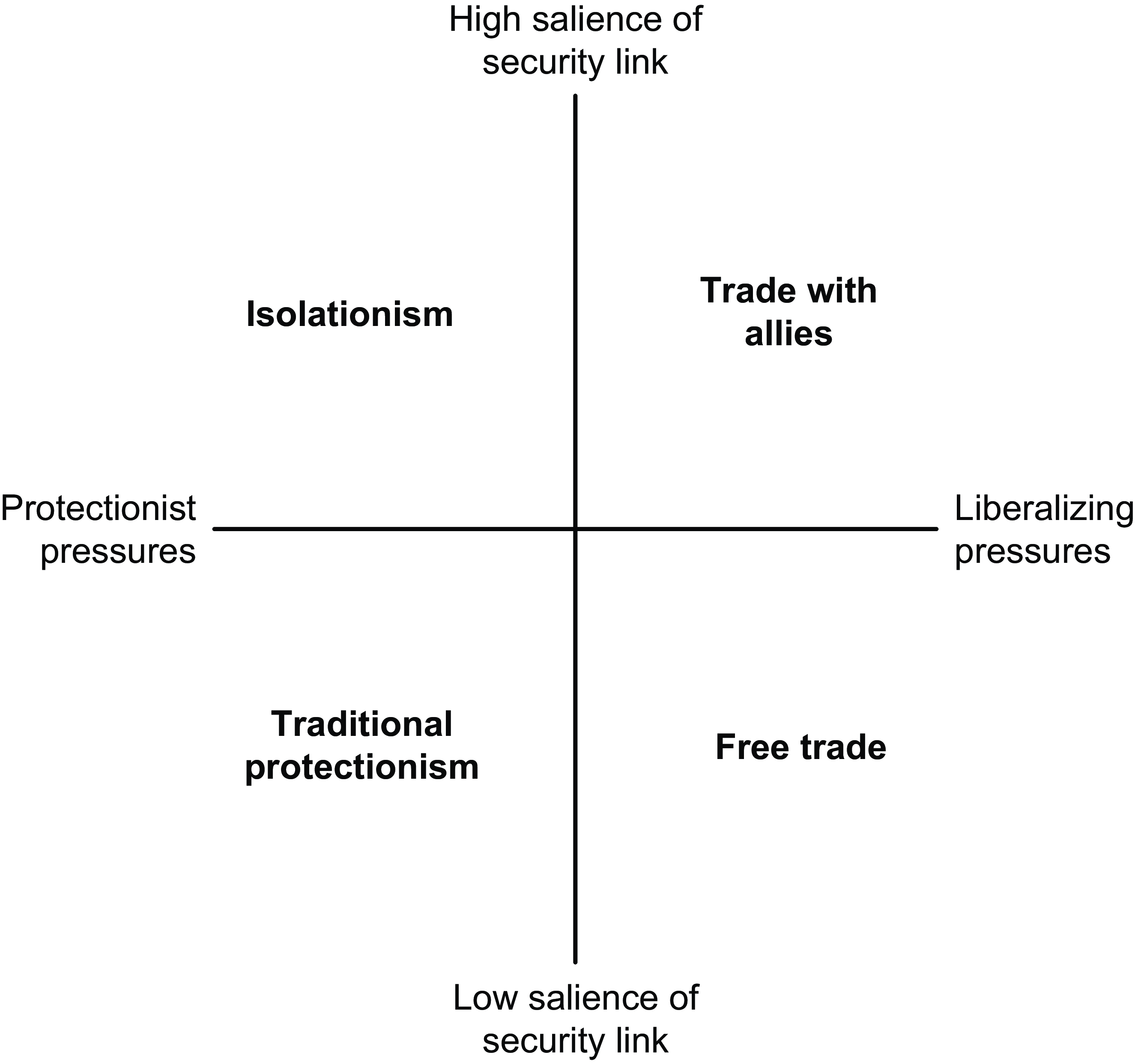

Instead, in Figure 2 we present a framework that locates different trade policy choices in a two-dimensional space to make sense of recent US trade policy. The framework focuses on two dimensions: the relative strength of protectionist and liberalizing pressures, and the salience of the trade-security linkage. The first dimension captures the relative support for closed versus open markets by citizens, interest groups, and political decision makers. In democratic systems, citizen preferences should dominate policy outcomes if it were not for often poorly informed voters and a lack of public salience of trade policy.Footnote 13 This creates opportunities for interest groups to exert influence through lobbying.Footnote 14 Political decision makers also retain some discretion to implement policies that align with their preferences. All of these actors may be motivated by economic considerationsFootnote 15 or ideological factorsFootnote 16 to support protectionism or liberalization.

FIGURE 2. The trade policy space

The second dimension concerns the salience of the trade-security linkage. Trade can generate significant security externalities,Footnote 17 allowing states to use it as a means of economic statecraft. Countries can become dependent on imports from or exports to particular trading partners, creating vulnerabilities. Trade also enhances national income, providing economic and physical resources that can be converted into military means or used to pursue broader geopolitical aims. Furthermore, trade facilitates the diffusion of technological innovations that may have security implications. The importance of these considerations varies over time and across trading relationships.Footnote 18 When the security externalities of commerce become prominent in policymaking, however, they influence the trade policies that countries pursue. Crucially, security concerns do not automatically dictate protectionist policies; they may equally support open markets.Footnote 19 Illustratively, security considerations arguably played a role in the decision to liberalize trade among Western allies at the onset of the Cold War. Accordingly, in Figure 2 we show the two dimensions as orthogonal.

Depending on where a country is positioned along the two dimensions, it will arrive at different trade policy outcomes. When support for open markets is strong and the security implications of trade are not salient, a country is likely to pursue policies that approximate free trade. As the salience of security concerns increases, trade policy shifts toward preferential exchange (in terms of both exports and imports) with geopolitical allies. In contrast, countries experiencing strong protectionist pressures will adopt more restrictive policies: if security concerns are low, this typically results in traditional protectionism, with import barriers often targeting specific sectors. If the security dimension is highly salient, however, such countries pursue an isolationist strategy, which likely entails import barriers, export restrictions, and sanctions, reflecting a combination of protectionism and economic statecraft.

The history of US trade policy offers examples for at least three of the four quadrants of Figure 2. The Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930 is a clear case of traditional protectionism: the United States imposed high tariffs on most imports without any significant discussion of security-related implications.Footnote 20 In the post–World War II era, both liberalizing pressures and the salience of the security link were higher, leading the United States to favor trade with allies as part of the broader Cold War strategy.Footnote 21 Following the end of the Cold War and up until the 2008 financial crisis, US policy loosely resembled the free trade ideal. Business interests with global value chain linkages dominated trade policy debates,Footnote 22 and security considerations played a negligible role. This period witnessed major liberalization efforts, including the establishment of the WTO and China’s accession to it.

Although certain orientations predominate at times, however, US trade policy rarely adheres to a single, coherent model. For instance, while the United States agreed to cut tariffs in GATT negotiations throughout the 1950s, protectionist pressures also remained strong.Footnote 23 Similarly, in parallel to the implementation of the Kennedy Round tariff cuts, President Nixon imposed a 10 percent tariff surcharge in 1971.Footnote 24 In the 1980s, the United States experienced renewed protectionist pressures driven by slow economic growth and intensified competition from Japan,Footnote 25 but still pushed for the start of a new multilateral round of trade negotiations from 1982 onwards.

Even during the post–Cold War “free trade” era, contradictions in US trade policy persisted. The debate over the ratification of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and the 1999 Seattle WTO protests revealed deep domestic divisions over globalization.Footnote 26 Protectionist sentiment reemerged visibly in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis.Footnote 27 This came to the fore under the Obama administration, which blocked the reappointment of WTO Appellate Body members who had ruled against the United States.

During his first term, Donald Trump imposed a wide range of tariffs, mostly targeting China, but refrained from full-blown protectionism. While the subsequent Biden administration changed its rhetoric and focused more on industrial policy and trade with allies, it retained many of these trade barriers. Overall, therefore, despite occasional swings to a dominant orientation (for example, today’s protectionist turn), at most times, US trade policy is eclectic. The aggregation of diverse positions situates it near the centre of Figure 2, reflecting a blend of protectionist and liberalizing as well as security- and non-security-motivated trade measures.

Toward Isolationism?

As of 2025, US trade policy might come close to the “isolationism” ideal type set out in Figure 2. This is the result of the convergence of protectionist pressures and an increasingly salient security dimension in trade policy. A substantial literature demonstrates that the “China shock”Footnote 28—the rapid surge in Chinese exports following its WTO accession—combined with technological changeFootnote 29 has intensified protectionist sentiment. As China transitions toward exporting sophisticated high-technology goods such as electric vehicles and semiconductors, we are likely witnessing the emergence of a “China shock 2.0” with potentially even more profound effects on trade policy preferences.Footnote 30 Simultaneously, some evidence indicates that the trade-security linkage is salient.Footnote 31 There are growing concerns about economic dependence, supply chain vulnerabilities, and the strategic implications of technological transfer. The simultaneous intensification of both protectionist pressures and security-driven trade considerations renders the current challenge to the multilateral trading system emanating from the United States so severe and potentially transformative.

To get an indication of whether the United States is actually located in the isolationist quadrant in Figure 2, we again rely on data from Global Trade Alert. To capture the salience of the security dimension, we disaggregate the data shown in Figure 1 in two ways. On the one hand, we separate measures aimed at strategic rivals (China, Russia, and Cuba) from those aimed at allies (Canada, Germany, and the United Kingdom).Footnote 32 For a country in the isolationist quadrant, we would expect a large number of import and export restrictions for both allies and rivals, although the latter should still dominate over the former. On the other hand, we use the rationales provided by the US administration and included in brief descriptions of the various measures on the Global Trade Alert website to find out which ones are legitimized on national security grounds. In our coding, we classify interventions as having a “security rationale” if at least one of a series of security-related terms (for example, “national security,” “sovereignty,” “foreign policy”) appears in the descriptions (see the appendix for a full list of the terms used).

Figure 3 presents these data. The emerging pattern is one of strong protectionism and a modest uptick in the importance of the trade-security linkage. Notably, as in the first Trump administration, also in the second presidency, we observe an increase in the number of discriminatory trade measures, consistent with substantial protectionist pressures.Footnote 33 The data also show that allies and rivals are similarly affected, though export restrictions are more prominent for rivals. Moreover, security rationales have gained salience over the past few years, especially for rivals and export restrictions.Footnote 34 Yet two factors suggest that current US trade policy does not fully align with the isolationist quadrant in Figure 2: measures without a security rationale still outnumber those with a security rationale, and the number of security-motivated export restrictions has actually declined since 2022 (when many sanctions were imposed against Russia). Overall, therefore, we conclude that contemporary US trade policy sits far on the protectionist side with a moderate link to security considerations. This is good news for the international trading system, because, as we argue next, protectionist pressures are likely less sticky than security concerns.

FIGURE 3. Trade restrictions by security rationale, alignment, and measure (United States, 2009–2025)

Notes: We show data for only three rivals (China, Russia, and Cuba) and three allies (Canada, Germany, and the United Kingdom). We display only the interventions between January and August for each year to ease comparability, because the data ends in August 2025. (Source: Authors’ calculations based on Global Trade Alert data).

A Return to Eclectic Trade Policy

If the United States were to occupy the isolationist quadrant in Figure 2 persistently, this would be very costly for both the United States and the world. Countries worldwide—many having themselves experienced a China shockFootnote 35 and now confronting a “China shock 2.0”—might find it difficult to sustain a relatively open trading system in this situation. Chinese exports redirected from the United States to Europe could further fuel protectionist pressures within the European Union. While some member states might initially resist, maintaining open markets would grow increasingly difficult. These dynamics threaten to weaken the liberal, rules-based trading system, potentially accelerating its erosion or collapse—especially harming smaller economies lacking bargaining power and fiscal capacity. By contrast, a return to the United States’ traditional eclectic trade approach would facilitate the preservation of the system.

We expect the trading system to remain resilient as US protectionist pressures ease through three channels: a turn in public opinion against protectionism, declining protectionist pressures from import-competing companies, and stronger mobilization by companies that benefit from international trade.Footnote 36 First, current US protectionism reflects the preferences of a part of the American electorate, which holds a decisive role in presidential elections. We expect these preferences to shift, as public opinion often functions like a “thermostat.”Footnote 37 In response to relatively free trade, which gave rise to the increase in Chinese imports that resulted in the China shock, public attitudes toward trade became increasingly less supportive.Footnote 38 In April 2024, for example, 59 percent of respondents to a survey approved of the statement that “the US has lost more than gained from increased trade.”Footnote 39 Now that protectionism has advanced, public opinion is likely to swing back toward open markets, especially as trade barriers cause inflation and slower growth.

Indeed, in August 2025, even among Republicans or Republican-leaning independents, only a minority thought that the newly imposed tariffs would have positive consequences for them or their families.Footnote 40 Moreover, in a national poll conducted in March 2025, 58 percent of respondents said tariffs hurt the economy, up from 45 percent in 2019 (see Figure A3 in the appendix). Similarly, in April 2025 a survey found that tariffs are widely regarded as harmful: 72 percent of respondents judged Trump’s tariff policies detrimental in the short term, and even when asked about the long-term effects, a majority (53 percent) expected them to hurt the economy (see Figure A4 in the appendix).

Second, Trump’s push for protectionism has also been supported by a range of business interests, including steel and aluminum producers, the textile industry, and segments of the broader manufacturing sector. However, much of this backing is issue-specific rather than ideological. Once these actors are satisfied with product-specific or sectoral protectionism, enthusiasm for across-the-board protectionism is likely to decline. Indeed, many of these industries are already internally divided: while some benefit from tariffs on Chinese imports, they rely on tariff-free inputs from Mexico. Even the aluminum industry, which staunchly supported tariffs in the past, has recently come out against the blanket tariffs imposed by the Trump administration.Footnote 41 In its crudest form, therefore, the current protectionism will retain only limited business support.

Finally, and most importantly, protectionism entails costs for many US firms. This concerns importers of finished goods and companies dependent on foreign intermediate goods in their production process. Moreover, although retaliation from foreign countries has been limited, US exporters may still face impaired foreign market access, as foreign countries increasingly trade among themselves to compensate for lost market access in the United States. These negative consequences for firms directly engaged in international trade likely also have repercussions for domestic suppliers. Not surprisingly, then, a survey of 331 Texas business executives from August 2025 shows that only 2 percent reported positive impacts from tariffs, while 48 percent reported negative effects.Footnote 42

These negative effects are likely to drive lobbying efforts against protectionism.Footnote 43 As I.M. Destler put it: “It is the embattled losers in trade who go into politics” and not “firms with expanding markets and ample profits.”Footnote 44 Indeed, there is evidence that losers from the US–China trade war turned against Republican candidates in the 2018 midterm elections.Footnote 45 Moreover, the public consultation launched in February 2025 on “harm from non-reciprocal trade arrangements” already saw strong participation of business interests opposing the tariffs.Footnote 46

We expect that the mobilization by these losers of the current trade war, together with the shift in public opinion and the buying off of at least some of the protectionist business interests, will push US trade policy rightward on the horizontal axis in Figure 2. This mechanism does not hinge on a change in partisan control of the administration or Congress, even if the current Democratic Party adopts a more liberal stance on trade policy. As long as trade is salient for the public (or at least swing voters) and organized interests, and opposition to full-blown protectionism dominates, either party has incentives to move away from the most egregious elements of current trade policy.

A potential objection and a caveat merit consideration. First, some observers expect the United States to move down a path toward competitive authoritarianism, possibly making shifting public opinion and interest group pressures irrelevant. Even in a competitive authoritarian country, however, public opinion and lobbying are likely to shape trade outcomes. Authoritarian incumbents require a degree of societal consent, and easing discontent by recalibrating trade policy is cheaper and safer than coercion. Because performance legitimacy looms large in such systems, economic outcomes carry extra weight. Moreover, even if the federal tier is partly insulated from mass sentiment via gerrymandering and the Electoral College, subnational officeholders who depend on voters will transmit local pressures upward when trade policies bite.

Second, we argue that there are inbuilt mechanisms that push US trade policy toward the middle on the protectionism-liberalization dimension. The same does not apply to the security dimension. A further rise in the importance of the trade-security link (for example, caused by a war over Taiwan), therefore, could independently threaten the system. During the Cold War, security concerns were high, but the US rival, the Soviet Union, was outside the trading regime. A geopolitical conflict with China—deeply embedded in the global economy—has no historical precedent, and it is unclear whether the system could withstand such a shock. The probability of such a disruptive geopolitical event occurring at any specific point in time is, however, relatively small.

Thus we expect a shift from across-the-board tariffs on goods from all countries toward targeted industrial policy, sectoral carve-outs, exemptions, selective protection, and security-framed export controls. Put differently, departures from liberal commitments will persist, but the current storm will pass.

The Future of the International Trading System

History demonstrates that the international trading system has considerable resilience to departures from liberal commitments: the postwar trading order weathered the creation of the European Economic Community, which initially caused alarm among excluded countries,Footnote 48 endured the protectionist turn of the 1970s and 1980s, coped with the failure of the Doha Development Agenda that was started in 2001, and rebounded after the 2008 financial crisis. When the United States decided to block the WTO’s Appellate Body, other WTO members created an alternative among themselves. Moreover, since 2000, the system has accommodated China’s state-driven mercantilism, which conflicted with both its letter and spirit.

It is no wonder, then, that despite current US protectionism, countries around the world remain reluctant to abandon the basic rules of the international trading system. Consequently, they continue to justify their trade-policy choices within the WTO framework. The European Union, for example, argues that its promised preferential tariff cuts for US goods are a step toward a WTO-compatible trade agreement,Footnote 49 and the Chinese President Xi Jinping called for the maintenance of a “multilateral trading system centred on the World Trade Organization.”Footnote 50 Other countries launch plurilateral cooperation to keep markets relatively open.Footnote 51 Taken together, these moves help sustain the international trading system’s resilience until—as we expect—protectionist pressures in the US abate.

This is not to say that the current disruptions are without costs. When major economies like the United States impose tariffs or bypass multilateral mechanisms, smaller countries are disproportionately negatively affected. Therefore, while outright disintegration is unlikely, the unequal impacts of US protectionism emphasize the need to address distributive justice within the evolving trade regime.

In essence, therefore, the international trading system has never hinged on perfect, uninterrupted liberalization or flawless rule compliance. Its architects deliberately incorporated mechanisms for flexibility and adjustment.Footnote 52 As long as the alternative to this imperfect yet functional order is outright disintegration, governments worldwide have strong incentives to preserve it and will tolerate deviations by their partners—especially powerful ones like the United States—in the expectation that such departures will prove temporary or represent adjustments in direction rather than a break with the system. In the absence of a major geopolitical shock, today’s disruptions, then, may ultimately serve to reinforce the system’s adaptive capacities. Reports of the death of the international tradin g system, hence, appear to be greatly exaggerated.

Data Availability Statement

Replication files for this essay may be found at <https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/AAH5VU>.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material for this essay is available at <https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818325101112>.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge comments from Manfred Elsig, Gemma Mateo, Frank Schimmelfennig, David Steinecke, Aydin Yildirim, two anonymous reviewers, and the editors on an earlier version of this paper.

Funding

Funded by the European Union (ERC, GEOTRADE, 101140687). Views and opinions expressed are, however, those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Research Council. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.