Introduction

Populism is often cited as one of the most prominent challenges to pluralist democracy (Mudde & Rovira‐Kaltwasser Reference Mudde and Rovira‐Kaltwasser2012; Müller Reference Müller2014: 491; 2016: 10–11) but remains a disputed concept. While some research traditions consider populism an ideology (Mudde Reference Mudde2004; Stanley Reference Stanley2008), others define it as political strategy employed by some charismatic leaders to reach or exercise power (Weyland Reference Weyland2001: 14; Pappas Reference Pappas2012: 2) or focus on the discursive (Laclau Reference Laclau2005a; Jagers & Walgrave Reference Jagers and Walgrave2007) and/or performative nature of the phenomenon (Ostiguy Reference Ostiguy2009; Moffitt Reference Moffitt2016). This paper attempts to challenge some of the prevailing theoretical and methodological assumptions and suggests a different way to conceptualise and investigate this complex phenomenon, reconciling the efforts of different research traditions.

The first part of this article analyses the main challenges faced in the literature and how these have contributed to different research pathways. It shows the historical difficulties of disentangling populism from nationalism, as well as the tension between the study of populist movements and that of populist attributes. It briefly outlines four research traditions based on different ontological premises and suggests that they may be considered synergic and operating on different rungs of the ladder of abstraction. The paper proposes going beyond the minimal definition approach and embracing the empirical multidimensionality of the concept.

The second part of this paper develops a model which deconstructs populism into five dimensions: (1) antagonistic depiction of the polity, (2) moral interpretation of the people, (3) idealised construction of society, (4) popular sovereignty and (5) reliance on charismatic leadership. It proposes different avenues for its operationalisation to analyse both the ‘supply‐side’ – narratives, discourses and policy proposals by political parties and their leaders – and ‘demand‐side’ of populism – citizens’ attitudes and beliefs (Mudde Reference Mudde2007). Finally, it suggests the visualisation of the model as a multilayered network structure, and the need to better understand and map the interactions and intersections among different populist dimensions and attributes.

The complex nature of populism studies

Populism versus nationalism

The conceptual conflation of populism and nationalism is generally considered one of the major limitations to populism studies (Brubaker Reference Brubaker2020: 44–45). Already in the seminal conference ‘To Define Populism’, held at the London School of Economics (LSE) in May 1967, and which set the agenda in the field for the years to come, profound discrepancies emerged in how to conceptualise and operationalise this somewhat elusive concept (Berlin Reference Berlin1968; Ionescu & Gellner Reference Ionescu, Gellner, Ionescu and Gellner1969). Disentangling the terms ‘populism’ and ‘nationalism’ was one of the main problems encountered. Some claimed that nationalism transformed or corrupted populism (Andreski & Venturi cited by Berlin Reference Berlin1968: 162), others that populism was a type of nationalism which equated ‘the nation’ and ‘the people’ (Stewart Reference Stewart, Ionescu and Gellner1969: 183–185) or that populism often led to nationalism (Ionescu & Walicki cited by Berlin Reference Berlin1968: 169, 172). While the study of nationalism, from its earlier inception, had the ambition to provide comprehensive macro‐historical explanations of the world's social, economic and political transformations, populism literature initially adopted a regional and episodic focus, a more reactive than generative stance. This sharp contrast gradually dissipated as nationalism scholars increasingly prioritised lower levels of analysis and populism started to be considered as a ubiquitous phenomenon (Brubaker Reference Brubaker2020: 47–49). Populism and nationalism became increasingly intertwined in social sciences.

Usually nationalism articulates ‘the people‐as‐nation’ while populism considers ‘the people‐as‐underdog’ (De Cleen Reference De Cleen, Rovira‐Kaltwasser, Taggart, Ochoa‐Espejo and Ostiguy2017). However, unravelling these concepts continues to be a problem not only in the public sphere but also in academia. The confluence of nationalism and populism in certain policy areas and claims, such as the defence of sovereignty and the critiques of supranational elites, has further contributed to the association of both concepts (De Cleen Reference De Cleen, Rovira‐Kaltwasser, Taggart, Ochoa‐Espejo and Ostiguy2017: 349–355).

Unlike nationalism, populism is not a typology with an inclusive shared tradition to which individuals or movements voluntarily adhere to, but an analytical status attributed by external analysts (Worsely Reference Worsley, Ionescu and Gellner1969: 218–220; Freeden Reference Freeden2017: 9). In the left, a few politicians and scholars have embraced the term openly (Errejón et al. Reference Errejón, Mouffe and Jones2016) and in the right this label has been sometimes assumed by activists from a fascist tradition as a way to legitimise or ‘de‐demonise’ their movements (Mammone Reference Mammone2009: 183–187; Eatwell Reference Eatwell, Rovira‐Kaltwasser, Taggart, Ochoa‐Espejo and Ostiguy2017: 379–381). However, populism is mostly used in a pejorative sense and putative populists rarely acknowledge to be such. This limits the sources available to researchers in the process of identification and assessment of populism and creates a further incentive to use nationalist parties as proxy subjects of study in lieu of populist ones. To better understand some contemporary political movements, it is important to analytically disentangle their nationalist and populist components, each of which has its own inner logic (Bonikowski Reference Bonikowski2017: S206). The second part of this paper outlines some of the differences between populism and nationalism.

Focusing on populist movements rather than on populism?

The diversity of groups considered as populist is one of the main difficulties faced by those trying to establish a common definition for the concept of populism. Berlin (Reference Berlin1968: 138–155) identified five historical types of populism: Russian populism which was a nineteenth century reaction against the development of capitalism; North American populisms, a more individualistic type of populism which opposed financial interests in the late nineteenth century; Latin American populisms which were rural and urban movements against the traditional elites developed after the 1930s economic depression; African populisms which tended to be driven by government leaders and glorified the ordinary individual; and Asian populisms that included a series of less cohesive national populisms which usually idealised village life as an opposition to Western individualism.

Many movements emerging later in the twentieth century have also been associated with the phenomenon, such as American nationalism (Skocpol & Williamson Reference Skocpol and Williamson2012), a revival of Latin American populism (de la Torre Reference De la Torre2010), personalistic Indian populisms (Subramanian Reference Subramanian2007), Eurosceptic right‐wing parties (Wodak et al. Reference Wodak, Mral and KhosraviNik2013), far‐right secessionist parties (Jagers & Walgrave Reference Jagers and Walgrave2007; Zaslove Reference Zaslove2011) and Southern European left‐wing populism (Stavrakakis & Katsambekis Reference Stavrakakis and Katsambekis2014; Ramiro & Gómez Reference Ramiro and Gómez2017). The growing trend has accelerated since the early 1990s (Mudde Reference Mudde2004: 548–551; Roberts Reference Roberts2007) and cannot be consistently identified with a particular type of policies, political ideology or socio‐economic group (Müller Reference Müller2016: 11–19).

The large and increasing set of movements termed as populist, each of them with different characteristics, has contributed to the problem of conceptual stretching (Collier & Mahon Reference Collier and Mahon1993). The term populism has been sometimes used as a loose identifier without deep theoretical implications in some analyses. For instance, Rodrik (Reference Rodrik2018: 12) defines populism as ‘a loose label that encompasses a diverse set of movements’, and Ţăranu (Reference Ţăranu2012: 131) argues that this term ‘covers more political and social realities than one single term would normally concentrate from a semantic point of view’. In this context of conceptual indeterminacy, it is not surprising that many authors (e.g., Inglehart & Norris Reference Inglehart and Norris2017; Rodrik Reference Rodrik2018; Hopkin & Blyth Reference Hopkin and Blyth2019) have decided to study empirically the emergence and success of populist parties without putting excessive emphasis on the implications of their analyses in terms of the conceptualisation of populism.

However, circumscribing the study of populism to the success and trajectories of ‘populist parties’ is problematic in several ways. Firstly, the complex nature of the term itself makes it difficult to agree on a specific set of requirements and thresholds to consider a party as populist (Roberts Reference Roberts1995: 85–86). Secondly, party actions, proposals and ideologies may evolve over time, which implies that parties could become or cease to be populist according to a dichotomous classification of populism. Thirdly, if the analysis of populism is restricted to the study of the evolution of parties or movements, analysts may miss the evolution of populist attitudes and beliefs in the population and media sphere, or even the emergence of populism within traditionally non‐populist parties. Moreover, populist attitudes may not even be consistently associated with support for populist parties (Hawkins & Rovira‐Kaltwasser Reference Hawkins, Rovira‐Kaltwasser, Hawkins, Carlin, Littvay and Rovira‐Kaltwasser2017a: 7). The study of why populist parties grow and decline is very valuable but requires to be complemented with a more micro approach on the specific nature of populism, and on the mechanisms through which this phenomenon, or condition, is conveyed into politics.

Shifting the attention to populist attributes

While some scholars have scrutinised populist parties and leaders, others have paid more attention to the conceptualisation of the phenomenon and tried to establish the common essential attributes – ideas, components and/or motives – underpinning populism. Numerous attributes or defining features have been suggested in the literature. For instance, populism has been characterised as a ‘peculiar negativism’, often directed against the elites, but sometimes also against other social groups or minorities (Berlin Reference Berlin1968: 169; Canovan Reference Canovan1981: 294; Mudde Reference Mudde2004: 543). It has been identified with the impulse for socio‐economic change and the defence of traditional values (Touraine cited by Berlin Reference Berlin1968: 157). Populism is also commonly related to ‘crises of representation’ (Laclau Reference Laclau2005a: 137; Roberts Reference Roberts2019), idealisation of the people (MacRae cited by Berlin Reference Berlin1968: 172) and illiberal understanding of democracy (Pappas Reference Pappas2019). This is by no means a comprehensive list of populist features – more methodically developed in the second part of this article – but it serves to exemplify the multifaceted nature of the concept, and show why the interpretations and research pathways of different authors in the field have diverged considerably.

Given the variety of attributes associated with the term ‘populism’, agreeing on a universal all‐inclusive definition is recognised as an extremely difficult challenge. Berlin warns against a ‘Platonic populism’ and falling into the ‘Cinderella complex’ according to which ‘there exists a shoe – the word “populism”– for which somewhere there must exist a foot. The prince is always wandering about with the shoe; and somewhere, we feel sure, there awaits it a limb called pure populism’ (LSE 1967: 139). Berlin is concerned with excessively loose conceptualisations of populism, which would end up bundling together very dissimilar movements, however, he also rejects overly rich and fixed formulas which may set a too high bar and preclude the findings of empirical cases (LSE 1967: 140).

Inspired by the classical categorisation introduced by Sartori (Reference Sartori1970: 1038–1044), many scholars opted for identifying a lowest common denominator and creating ‘minimal definitions’ with the core components or shared defining attributes of populism (Mudde & Rovira‐Kaltwasser Reference Mudde and Rovira‐Kaltwasser2013: 7; Rooduijn Reference Rooduijn2014). Lessening the number of properties that are necessary and sufficient to be part of a category, such as ‘populism’, allows a concept to be applied to a variety of cases and contexts, without having to render it excessively vague or abstract.

Ontological disagreements

However, reaching agreement on the essential nature of populism – its overarching dimension or genus – has continued to be a challenge in the field. Significant ontological discrepancies were already evident in the 1967 LSE seminal conference, where many panellists considered populism primarily as an ideology, but others raised concerns and defined it as a movement or emphasised the utilisation or manipulation of certain ideas and discourses as a political tool (Berlin Reference Berlin1968: 167–179; Minogue Reference Minogue, Ionescu and Gellner1969: 198). Ever since, broadly four approaches to the study of populism can be distinguished: (1) an ideational approach which considers populism as a political ‘thin’ ideology; (2) a political‐strategic approach, which focuses on the actions of political leaders to reach and exercise power; (3) a discursive approach which focuses on how populist claims are articulated; and (4) a performative approach which includes a socio‐cultural dimension and focuses on political styles (Bonikowski & Gidron Reference Bonikowski and Gidron2016; Moffitt Reference Moffitt2016: 17–25, 41–43; Mudde Reference Mudde, Rovira‐Kaltwasser, Taggart, Ochoa‐Espejo and Ostiguy2017: 39–40).

Arguably the most influential approach today is the one defining populism as a ‘thin’, or ‘thin‐centred’, ideology that considers ‘society to be ultimately divided into two antagonistic and homogenous groups – “the pure people” and “the corrupt elite” – and that politics should be an expression of the volonté générale’ (Mudde Reference Mudde2004: 543). This conception, inspired by Freeden (Reference Freeden1996), suggests that populism does not offer a complete worldview and fails to exhibit the degree of consistency, depth and scope of other full developed, ‘thick’, ideologies such as socialism and liberalism. Nevertheless, populism understood as a ‘thin’ ideology, still provides a framework heuristically useful for the interpretation of a political reality (Stanley Reference Stanley2008: 99). This approach helps in connecting the supply‐side and the demand‐side of populism (Mudde & Rovira‐Kaltwasser Reference Mudde and Rovira‐Kaltwasser2012: 10) and explaining why populism is usually combined with other ideologies, such as socialism and nationalism, or why populist parties are so varied and flexible from programmatic, organisational and leadership points of view as comparative studies demonstrate (Roberts Reference Roberts2006; Judis Reference Judis2016).

However, not everyone finds the ideology perspective as the preferred basis for a long‐term research agenda. Kazin (Reference Kazin1998: 3) argues that populism should be understood as a ‘flexible mode of persuasion’ rather than as an ideology. He defines populism as ‘a language whose speakers conceive of ordinary people as a noble assemblage, not bounded narrowly by class, view their elite opponents as self‐serving and undemocratic, and seek to mobilize the former against the latter’ (Kazin Reference Kazin1998: 1). Similarly, Weyland claims that ‘populism is best defined as a political strategy through which personalistic leaders seek or exercise government power based on direct, un‐mediated, un‐institutionalized support from large numbers of mostly un‐organized followers’ (Weyland Reference Weyland2001: 14).

Laclau and other authors of the Essex School suggest shifting the focus of analysis away from movements and ideologies and concentrate on how discourses are constructed. This means a displacement of conceptualisation from the contents to the form (Laclau Reference Laclau and F.2005b: 44), and considering a subject as populist not because they have a specific ideology, but because they show a particular ‘logic of articulation’ of social, political or ideological content, whatever those contents are (Laclau Reference Laclau and F.2005b: 33–34; De Cleen Reference De Cleen, Rovira‐Kaltwasser, Taggart, Ochoa‐Espejo and Ostiguy2017: 345–347). Accordingly, populist discourses aim to construct and ‘de‐contest’ a certain meaning of ‘the people’ through the definition of a frontier which separates them from the ‘elite’ and, consequently, populism may be interpreted as the very logic of construction of political identities (Laclau Reference Laclau2005a: 18–19, 74, 83). Populist discourses follow a ‘logic of equivalence’ and unite the people by presenting their demands, fears and grievances against ‘the other’ as similar. This is achieved by the discursive creation of ‘empty signifiers’, which do not have clearly defined or fixed ‘signifieds’, but which symbolic power brings equivalential homogeneity to the heterogeneity of particular social demands (Laclau Reference Laclau and F.2005b: 40–44).

Ostiguy (Reference Ostiguy2009, Reference Ostiguy, Rovira‐Kaltwasser, Taggart, Ochoa‐Espejo and Ostiguy2017), the proponent of the socio‐cultural or performative approach, suggests the relational nature of the term and the importance of affects in populism. If ideologies are involved in processes of ‘de‐contestation’, as Freeden (Reference Freeden1996: 78) argues, populism could be identified with a process of creation and recreations of identities, shaped by the relations between ‘the people’ and the leader, as well as their relationships with the ‘nefarious other’. Ostiguy defines populism as the ‘flaunting of “the low”’, referring to an antagonistic, uninhibited and coarse style adopted by personalistic leaders (Ostiguy Reference Ostiguy, Rovira‐Kaltwasser, Taggart, Ochoa‐Espejo and Ostiguy2017: 73–74, 79). On a similar vein, Moffitt argues that populism is a political style which is embodied and performed across different cultural and political contexts, not specific to the left or right. He also refers to the role of ‘bad manners’ in populist appeal (Moffitt & Tormey Reference Moffitt and Tormey2014: 392; Moffitt Reference Moffitt2016).

Reconciling approaches

The disagreements concerning the nature of populism, its essential attributes and how to operationalise the concept, do not necessarily imply that scholars in the field are doomed to walk diverging research pathways. The above‐mentioned approaches are not mutually exclusive and there is room for synergic and cumulative work. Populist strategies, discourses and styles are usually grounded on certain populist ideological traits of political leaders or the people they try to influence. There are connections between the ideological, ‘believe in’, and attitudinal and performative aspects of populism, ‘live’ or ‘act as a populist’ (Venturi cited by Berlin Reference Berlin1968: 140; Ostiguy Reference Ostiguy, Rovira‐Kaltwasser, Taggart, Ochoa‐Espejo and Ostiguy2017: 74, 92). Even those who consider populism as a mere rhetorical device or performance by opportunist leaders without any particular ideology, would agree that the success of such political strategy relies on the existence of shared ideational frames or worldviews among the citizens they appeal to – which resonates with the concept of ‘thin ideology’. Similarly, some proponents of the ideational approach now acknowledge the influence from Laclau's discursive work and use the term ‘discourse’ and ‘ideology’ interchangeably (Hawkins & Rovira‐Kaltwasser Reference Hawkins and Rovira‐Kaltwasser2017b: 514).

Another source of disagreement comes from considering populism either as a matter of degree or of nature (Bonikowski & Gidron Reference Bonikowski and Gidron2016: 8–9). While researchers focusing on political discourses frequently document different degrees in populism (Deegan‐Krause & Haughton Reference Deegan‐Krause and Haughton2009: 822; Aslanidis Reference Aslanidis2016: 92–93; Bernhard & Kriesi Reference Bernhard and Kriesi2019: 17), those identifying populism with an ideology have often suggested binary assessments – ‘populist’/‘non‐populist’ – of parties and leaders (Mudde & Rovira‐Kaltvasser Reference Mudde and Rovira‐Kaltwasser2017). However, many researchers in the ideational camp (e.g., ‘Team Populism’) have also developed tools to capture populism degrees in political communication (Hawkins Reference Hawkins2009; Marcos‐Marne et al. Reference Marcos‐Marne, Plaza‐Colodro and Hawkins2020) and citizens’ attitudes (Hawkins et al. Reference Hawkins, Riding and Mudde2012; Akkerman et al. Reference Akkerman, Mudde and Zaslove2014; Van Hauwaert & Van Kessel Reference Van Hauwaert and Van Kessel2018; Castanho Silva et al. Reference Castanho Silva, Jungkunz, Helbling and Littvay2020).

Although at a theoretical level these different approaches reflect meaningful ontological discrepancies, at an empirical level these cannot always be captured in a reliable way (Mudde Reference Mudde, Rovira‐Kaltwasser, Taggart, Ochoa‐Espejo and Ostiguy2017: 31). While researchers may struggle to insulate the ultimate motives or principles driving populists, they can more easily analyse communication frames and claims articulated in speeches and written communications, as well as expressed preferences or attitudes via surveys, focus groups and interviews.

From the point of view of data collection, these approaches may not differ significantly and could be interpreted as working on a same socio‐political phenomenon but at different rungs of the ladder of abstraction.Footnote 1 Diverse units and levels of analysis may be used to scrutinise political ideologies, campaign strategies, leadership styles and discourses, yet these are mostly complementary efforts. There has also been a process of definitional convergence. Although different authors propose more or less restrictive requirements in their definitions, all these approaches coincide on a conceptual core of basic attributes or thematic elements associated with populism or its manifestations, such as a Manichean interpretation of politics, anti‐elitism, moral condemnation of adversaries and idealised conceptions of ‘the people’.

Embracing multidimensionality

Rather than focusing on a ‘minimal definition’ and using a classical categorisation with a small set of necessary and sufficient criteria (Sartori Reference Sartori1970), this paper proposes identifying a wider set of features which are part of the ideational or discursive repertoire populists draw from. In line with Wittgenstein's ‘family resemblances’ and Lakoff's ‘radial structure’ (Lakoff Reference Lakoff1987: 16–20, 83–84; Collier & Mahon Reference Collier and Mahon1993: 848–850), it suggests that not all ‘populists’ need to share all defining attributes of populism. Admittedly, such an approach makes it more difficult to classify subjects as ‘populist’ or ‘non‐populist’ since several thresholds, weights and rules concerning priority or necessity would be needed. However, if one seeks a deeper understanding of populism – and its diverse manifestations – and is interested in gathering data to analyse borderline cases and identify varieties within populism, a multidimensional approach is needed.

The adoption of a minimal definition stance at the level of data collection generates some problems. If populism has a dynamic nature (Bonikowski Reference Bonikowski2016: 13) and subjects of study change their views, strategies and discourses overtime, they may end up being intermittently as populist and non‐populists. For instance, if we consider ‘anti‐elitism’ the unique essential attribute of populism, some populist parties when reaching office may stop being considered populist, even if the rest of their ideals, actions and discourses remain unchanged. Likewise, someone endorsing at large a pluralist conception of democracy could be classified as populist for displaying anti‐elitist views. Minimal definitions can be a very good fit for some types of populism but not for others. For instance, Mudde's definition (Reference Mudde2004) matches very well some European right‐wing parties but not so much Latin American populisms (De la Torre & Mazzoleni Reference De la Torre and Mazzoleni2019: 81–85, 90–91). Agreeing, and enforcing, a minimal standard definition with fixed necessary and sufficient conditions may not be possible or productive for this kind of high‐order concept (Gerring Reference Gerring1999: 360, 391–392).

By considering populist attitudes as a higher order latent construct, elicited from multiple lower order dimensions, such as those presented in the next section, we may avoid the problems above and provide a more fine‐grained description of the phenomenon (Schultz et al. Reference Schulz, Müller, Schemer, Wirz, Wettstein and Wirth2017: 318–319). A multidimensional approach which disaggregates populism into different attributes or components, may help to identify differences and nuances across cases that otherwise may remain muted (Wiesehomeier Reference Wiesehomeier, Carlin, Hawkins, Littvay and Rovira‐Kaltwasser2019: 105). Moreover, if populism is interpreted as a combination of several attributes, the resulting construct can be easily expressed as a gradient, which an increasing number of scholars recommend.Footnote 2 A multidimensional approach to data collection allows embracing the empirical complexity of the phenomenon without precluding other approaches, as the data it generates could be still filtered and used by proponents of a more restrictive definition and a classical categorisation.

Theoretically deconstructing populism into five dimensions

Despite the abovementioned discrepancies on the essence of populism, there is a wider consensus on several of the key features associated with populism (Moffitt Reference Moffitt2016: 26). Based on the most influential conceptualisations of the term, this section deconstructs populism into five dimensions: (1) depiction of the polity, (2) morality, (3) construction of society, (4) sovereignty and (5) leadership. Each of these thematic dimensions accommodates a variety of ideological and discursive attributes that could be studied at different levels of analysis, across left‐ and right‐wing movements, and in, both, the supply‐ and demand‐sides of populism. These dimensions also help disentangle populism from nationalism. This paper does not prescribe any of these dimensions – and features associated – as necessary requirements shared by all ‘populist’ subjects. However, it suggests the existence of an inner logic (Müller Reference Müller2016: 10) and that it is the combination of several of these populist elements that is characteristic of populism and that generates the variety and complexity observed empirically (Brubaker Reference Brubaker2017: 361).

The identification and refinement of dimensions combined a deductive process of examination of the most influential texts on populism, with an inductive process based on a pilot content analysis and repeated exchanges with key authors. These dimensions are set primarily at the content plane and try to capture ‘what’ is said or thought. Alternative dimensions and angles of this complex phenomenon were considered initially, but not included in this categorisation. Some of them – for example demagoguery, opportunism, persuasiveness, communication channels and articulation style (Kazin Reference Kazin1998; Ostiguy Reference Ostiguy, Rovira‐Kaltwasser, Taggart, Ochoa‐Espejo and Ostiguy2017) – pertain to the expression plane and focus on ‘how’ populist content is conveyed, while others – for example mobilisation strategies, crisis of trust and representation (Canovan Reference Canovan1999; Weyland Reference Weyland2001) – give analytical priority to socio‐political contexts and structural legacies. Although they are worth studying and complementary, they operate at parallel but separate levels and different methodologies would be required to analyse them.Footnote 3

Antagonistic depiction of the polity

One of the most widely agreed features of populism is the antithetical depiction of ‘the people’ versus ‘the other’, usually ‘the elite’ (Stavrakakis Reference Stavrakakis2004: 259; Laclau Reference Laclau and F.2005b: 39). Society in general, and the polity in particular, are symbolically divided. ‘The people’ are considered by populists as ‘the underdog’ and defined through their relation of antagonism with ‘the other’ who is not only a political opponent but an ‘enemy of the people’ (Panizza Reference Panizza2005: 3; Müller Reference Müller2016: 4). Populism is often characterised as a sort of reaction or negativism, usually anti‐elite and anti‐establishment but sometimes also anti‐capitalistic, anti‐intellectual, anti‐migrant or anti‐Semitic (Worsley and Ionescu cited in Berlin Reference Berlin1968: 168–169, Wiles Reference Wiles, Ionescu and Gellner1969: 167, Bonikowski Reference Bonikowski2017: 184–185).

Like nationalists, populists often rely on a post‐modern logic of inclusion and exclusion, according to which symbolic boundaries and belonging to the in‐group are grounded on specific notions of ‘national culture’ which are socially constructed and reconstructed (Lochocki Reference Lochocki2018: 23). Boundaries between groups, sometimes based on territory, language or biological traits, are justified following the logic of ‘cultural differentialism’ and the right of people to preserve their distinctive identity (Ritzer & Yagatich Reference Ritzer, Yagatich and Ritzer2016: 112–113).

However, not all forms of antagonism in populism are grounded on cultural, ethnic or territorial boundaries. The Manichean distinction between the common or ordinary people and the ‘elite’ is arguably the crucial form of antagonism shared by most populist movements both at the left and right of the political spectrum, from Latin American Bolivarian to Eurosceptic British populists. Thus, while in nationalism, antagonism is always based on a somewhat horizontal, or territorial, conception of the in‐group/out‐group divide, populists usually rely on a vertical or hierarchical distinction (De Cleen & Stavrakakis Reference De Cleen and Stavrakakis2017: 309–312). They are typically against those ‘on top’, ‘the elites’, but also sometimes against those ‘on the bottom’, ‘deviants’ and ‘underserving’ (Brubaker Reference Brubaker2020: 54). However, these vertical and horizontal oppositions may be construed as constitutively intertwined and populists often not only oppose ‘internal outsiders’ operating ‘within the polity’ but also ‘external outsiders’ such as the European Union, American Imperialism, the global capital, upcoming refugees or cultural threats (Brubaker Reference Brubaker2020: 54–58).

Antagonism often appears reflected in the utilisation of a simplistic hyperbolic rhetoric to disqualify the opponent and militaristic terms to describe political processes such as ‘lost battle’, ‘rendition’, ‘fifth columnists’ (Tanguieff Reference Tanguieff1984: 125–126). Populist movements usually idealise and aestheticise fighting and confrontation (Krasteva & Lazaridis Reference Krasteva, Lazaridis and Ranieri2016: 18–20).

Populism can be construed as a counter‐hegemonic endeavour to cultivate the aspirations of ordinary people and challenge the status quo (Panizza Reference Panizza2005: 3–4; Grattan Reference Grattan2016: 10–11, 14–18). Populism tends to be fuelled by the anger and frustration of citizens (Müller Reference Müller2016: 9, 15–17) and seeks a sort of rebellion of the common people against the political and socio‐economic elites who exploit or oppress them. The political and economic establishment is challenged by the construction of a collective ‘underdog’ (Laclau Reference Laclau and F.2005b: 44). Populists usually ask for drastic changes in the political system or in the most important institutions. This scepticism is based on the idea that they have become the instruments of the ‘corrupt elite’ and obstacles to the expression of the ‘will of the people’. Moreover, populist movements tend to gain strength from the perceived crises and system breakdowns and favour swift actions over gradual change and long deliberation (Moffitt Reference Moffitt2016: 45). Nationalists are usually not as keen as populists at introducing radical change.

However, populists are more anti‐establishment than anarchist in principle (Wiles cited by Berlin Reference Berlin1968: 159) and they are not opposed to the utilisation and adaptation of institutions as instrument to achieve their ideals. When in power, populists tend to abuse state institutions and engage in corruption and mass clientelism (Müller Reference Müller2016: 4). Populist leaders such as Orbán, Kaczynski and Chávez tend to ‘occupy’ and reshape institutions for their personal or party interest (Arato Reference Arato2013: 157; Müller Reference Müller2016: 44‐49). The distinction between the people and the elite is moral, not situational, which allows them to maintain an anti‐establishment discourse even when they are in government (Mudde & Rovira‐Kaltwasser Reference Mudde and Rovira‐Kaltwasser2017: 12). Populism can be, therefore, a sort of ‘elitist anti‐elitism’ (Berlin Reference Berlin1968: 70, 140).

Moral interpretation of political actors

Populism is associated with a moral or normative interpretation of ‘the people’ as opposed to an empirical one, with an emphasis on distinction between the ‘pure’ or ‘virtuous people’ and the ‘corrupt elite’ (Mudde Reference Mudde2004: 543; Laclau Reference Laclau and F.2005b: 4; Arato Reference Arato2013: 156). Populists consider themselves as part of a moral community (Kazin Reference Kazin1998: 34), the exclusive defenders of the common good and representatives of ‘the people’ (Müller Reference Müller2016: 3). Most populist movements express the necessity of a moral regeneration too (Berlin Reference Berlin1968: 174). This moralistic interpretation of politics is also the basis for the abovementioned antagonistic depiction of ‘the people’ and the ‘elite’.

Wiles (Reference Wiles, Ionescu and Gellner1969: 167) argues that populism is ‘moralistic rather than programmatic’ and that logic and effectiveness are not as highly valued as righteousness. Using Aristotle's rhetoric terminology (Braet Reference Braet1992), populism would imply that judgments on the value of policy proposals would be based not so much on the logos – that is data, facts or rational argumentation, but on the ethos of the proponent – that is. their credibility and ethical appeal, and pathos – that is the emotional appeal of the speaker's words. Hence, ad hominem arguments aiming to arouse emotions – such as prejudice (diabole), pity (eleos), or anger (orge) – tend to supersede criticisms on the substance of opponents’ policy proposals. Populists usually claim a higher moral ground and try to disqualify, ridicule and delegitimise the political rival rather than unpack their arguments (Tanguieff Reference Tanguieff1984: 118). Rejecting the legitimacy of political opponents is a consequence of the moral distinction populists make, as well as a tool to consolidate a sense of moral superiority vis‐à‐vis the other. Whoever competes with populists, opposes their claims or criticises their abuses is excluded from ‘the people’, vilified and treated as a traitor to the people (Müller Reference Müller, Rovira‐Kaltwasser, Taggart, Ochoa‐Espejo and Ostiguy2017: 593).

The moral dimension is also reflected in populists’ blame (Vasilopoulou et al. Reference Vasilopoulou, Halikiopoulou and Exadaktylos2014) and victimisation discourses, which are constitutive of, and constituted by, their antagonistic depiction of the polity. Besides, the political psychology of populism is associated with the feeling that conspiracies against the ‘people’ are at work (Berlin Reference Berlin1968: 169). Populists tend to believe in global conspiracies involving ill‐intentioned small powerful groups controlling world events and information (Castanho Silva et al. Reference Castanho Silva, Vegetti and Littvay2017: 437). In their narratives, ‘the people’ are victims of the establishment, a sort of David fighting against Goliath, the exploitative and oppressive elites (Mouffé Reference Mouffé and Panizza2005: 64).

Although some nationalists also rely on moral arguments to delegitimise ‘the other’, that is not an intrinsic feature of nationalism. Nationalists tend to rely on a more horizontal and less hierarchical way of articulating divides and do not need to delegitimise the opponent but simply to recall that the ‘other’ has conflicting interests, as for instance, the realist tradition in international relations would suggest.

Idealised construction of society

Another common feature of populism is the ahistorical and anti‐pluralist idealisation of society, which tends to focus on a homogenous collective identity. Most populist accounts root their conception of ‘the people’ in a romanticised ‘heartland’, an idolised community, usually associated with a specific territory, retrospectively constructed. Mudde (Reference Mudde2004: 546) compares the populist ‘heartland’ to Anderson's (Reference Anderson1983) ‘imagined community’ concept. However, this idealised community does not need to be grounded on the concept of nation, as in the case of nationalism.

Populist constructions of the ‘heartland’ are usually based on an emotional and ahistorical conception of the past (Taggart Reference Taggart2000: 3–5). Populist movements engage in strategies of re‐elaboration of the past to shape collective memories, for instance to contribute to self‐victimisation narratives or cancellation of inconvenient past events or processes (Caramani & Manucci Reference Caramani and Manucci2019: 1163–1165). Nevertheless, populism cannot be considered exclusively backward looking. Worsley (cited in Berlin Reference Berlin1968: 168) referred to the Janus syndrome: populists look back in order to look forward. They usually defend some traditional values and, at the same time, are oriented towards economic and social change (Touraine cited by Berlin Reference Berlin1968: 157).

Homogeneity and exclusion are also key elements of populists’ interpretation of society (Jagers & Walgrave Reference Jagers and Walgrave2007: 323). Theirs is a monist conception of ‘the people’ as a good and homogeneous group opposed to the ‘corrupt other’ ( Mudde Reference Mudde2004: 543; Müller Reference Müller2014: 491; Mudde & Rovira‐Kaltwasser Reference Mudde and Rovira‐Kaltwasser2017: 7). This poses a challenge to modern notions of democracy which are largely based on diversity and plurality. ‘The people’, as understood by populists, do not encompass the entirety of the population. It is an idealisation of a people, or Volk, rather than the people (MacRae cited by Berlin Reference Berlin1968: 172).

This (re‐)construction of society is only possible thanks to the production of ‘empty signifiers’. These are vague and malleable symbols or conceptualisations of universal ideals, with a homogenising function in a highly heterogeneous reality (Laclau Reference Laclau and F.2005b: 39–40). Laclau and Mouffe argue that populists use these ‘empty signifiers’ to create ‘chains of equivalence’ and bring together people with different, but comparable, fear, concerns, resentment and grievances. These ‘chains of equivalence’ cut across different social sectors and particular interests and help construct ‘the people’ as the union of those who oppose the elites and struggle against different, but equivalent, forms of subordination (Laclau & Mouffe Reference Laclau and Mouffe2001: xviii—xix; Laclau Reference Laclau and F.2005b: 38, 44—46; Mouffe Reference Mouffé and Panizza2005: 69). They are tools of mutual recognition and inclusion but also contribute to a process of ‘othering’ and exclusion, through the dichotomisation of the social around an internal frontier separating ‘the underdog’ from ‘the power’.

The dissonance between the ‘empirical’ or ‘actual people’, and their ‘ideal people’ pushes populists to request the extraction of part of the people from within the people (Müller Reference Müller2014). Populists not only antagonise ‘the others’, who they recognise as morally inferior, but they also try to exclude them altogether (Müller Reference Müller2016: 4). The underserving and corrupt minorities; ‘the elite’, ‘the caste’, ‘the colonisers’, ‘the immigrants’, do not really belong to the demos or the ‘heartland’ and, therefore, the ‘true’ or ‘authentic’ people must fight to achieve plenitude and ‘have their country back’ (Panizza Reference Panizza2005: 3—4; Reference Panizza, Rovira‐Kaltwasser, Taggart, Ochoa‐Espejo and Ostiguy2017: 409–411). The populist logic produces sometimes the dehumanisation of the enemy and becomes a justification for authoritarianism in the process of extrication of ‘the people’ from its empirical form (Arato Reference Arato2013: 167).

Absence of limits to popular sovereignty

The ideal of ‘popular sovereignty’ is central to populism (Panizza Reference Panizza2005: 4—5; Jagers & Walgrave Reference Jagers and Walgrave2007: 323) and largely derives from the dimensions presented above. Populism entails an ‘exaltation of and appeal to “the people”’ (Canovan Reference Canovan1981: 294). It suggests the supremacy of the people over any political or legal institution, and an unmediated relationship between the people and the government (Shils Reference Shils1956: 98–104). The mass of individuals, ‘the people’, is the rightful sovereign and it can ascertain what is best for the collective (Hawkins Reference Hawkins2009: 1043). Following this logic, ‘the will of the people’ should not be constrained by legal or political institutions. Populists understand ‘democracy’ as the government by the sovereign people not as that of politicians and civil servants (Canovan Reference Canovan, Mény and Surel2002: 33–37).

This logic emanates from the dualistic and moral interpretation of society. Populists are suspicious of laws and institutions which could limit the ‘will of the people’ and which probably have been created or corrupted by the ‘elites’. They are often hostile to the discourses of rights as these may shield minorities from the ‘will of the majority’. Populists often perceive expressions of institutionalised pluralism such as public contestation or political competition as hindrances to popular sovereignty (Roberts Reference Roberts2019: 191). Theirs is often an extreme conception of majoritarian rule (Mudde Reference Mudde2013: 4).

This majoritarian conception of politics nurtures a reliance on direct democracy instruments, such as referendums, public consultations and popular initiatives. These instruments are also perceived by populists as an opportunity to bypass politicians and institutions, which they distrust (Canovan Reference Canovan1981:177; Taggart Reference Taggart2000: 103–105). The preference for direct democracy also resonates with populists’ dichotomisation and simplification of social and political realities. For them, the usual legal and institutional procedures of decision making associated with representative democracy require legitimation and need to be submitted, at least symbolically, to the authority of the people. The association between populist attitudes and support for direct democracy has been recently confirmed by empirical studies (Jacobs et al. Reference Jacobs, Akkerman and Zaslove2018; Mohrenberg et al. Reference Mohrenberg, Huber and Freyburg2019). This preference for direct democratic tools and praise for people's ability to make decisions are features that can help distinguish populism from nationalism.

Populists’ exaltation of popular sovereignty may contribute to enfranchise citizens by widening political participation and grasping their attention on policy issues (Canovan Reference Canovan1999: 14–16; Reference Canovan, Mény and Surel2002: 42–43). Populism would be a sort of empowering ideal or discourse, and an avenue to promote democratic inclusiveness (Mény & Surel Reference Mény, Surel, Mény and Surel2002). However, the assumption that the common good is easily discernible by ‘the people’ underpinning many populist arguments leads to simplistic policy solutions based on ‘common sense’, often at odds with the opinion of experts (Müller Reference Müller2016: 25–31; Mudde & Rovira‐Kaltwasser Reference Mudde and Rovira‐Kaltwasser2017: 16–17, 68). Moreover, this conception of popular sovereignty is not only a corrective but also a threat for a liberal interpretation of democracy, as it clashes with the principle of separation of powers, and could lead to bypassing minority rights (Mudde & Rovira‐Kaltwasser Reference Mudde and Rovira‐Kaltwasser2012: 18–22, 205–222) and a potential tyranny of the majority (Stavrakakis Reference Stavrakakis2004: 239).

Reliance on charismatic leadership

Finally, the reliance on charismatic leaders has also been considered an important feature in populism (Taggart Reference Taggart2000: 100–103; Laclau Reference Laclau2005a: 99–100). Populist movements often emerge when personalistic leaders mobilise and receive support from a large and un‐institutionalised mass of people (Weyland Reference Weyland2001: 4–18). Sometimes the name of the movement is associated with that of the leader, such as French Poujadisme, Argentinian Peronismo and Venezuelan Chavismo. Those leaders are considered by populists as a sort of incarnation of ‘the people’ who are capable of discerning and articulating the ‘will of the people’ (Kriesi Reference Kriesi2014: 363; Müller Reference Müller2016: 32–38). Populist leaders may even become messianic and transcendental saviours of the people and end up superseding the authority of the usual representative political institutions (Finchelstein Reference Finchelstein2017: xxxvi, 183).

This is a somewhat unmediated relationship between ‘the people’ and the ‘leader’, who can feel their wishes and voices them, without the need of conventional party structures and traditional institutional channels of communication.Footnote 4 This idealised unmediated connection between populist leaders and their people resonates with the concept of sovereignty and the idealised understanding of society described above. Arato (Reference Arato2013: 156–166) argues that populism can be considered as a ‘disguised political theology’ following the ‘king's two‐bodies’ metaphor in which the leader embodies the popular subject and contributes to prevent ‘the people’ from falling into disunity.

The nature of the populist leadership is nonetheless diverse. There are charismatic strongmen or strongwomen, entrepreneurs and ‘ethnic leaders’. Some of them are relatively new to politics and their leadership may have been constructed ‘bottom‐up’ while others have been members of pre‐existing political parties or state institutions for years (Müller Reference Müller2016: 32–36; Mudde & Rovira‐Kaltwasser Reference Mudde and Rovira‐Kaltwasser2017: 62–78). Sometimes, charismatic leaders do not formally lead the party or run for elections, such as Grillo in Italy. In other cases, these leaders are replaced without deep consequences to the movement, such as the case of the leadership of the Danish People's Party. However, some authors argue that the presence of a charismatic leader is a facilitating element, rather than a requirement (Zúquete Reference Zúquete, Rovira‐Kaltwasser, Taggart, Ochoa‐Espejo and Ostiguy2017: 455) and that personalist leadership is not a phenomenon exclusive to populism (Panizza Reference Panizza, Rovira‐Kaltwasser, Taggart, Ochoa‐Espejo and Ostiguy2017: 412).

Using this comparative framework and challenges ahead

The call to go beyond minimal definitions and adopting a multidimensional framework seeks to incentivise the collection of data on a wider set of attributes which could help to better understand the structure of the concept and distinguish varieties of populism, such as right‐wing and left‐wing populisms, region or country‐specific populisms, and so on. Each of the five dimensions above can be construed as lower order constructs composed of several attributes or subdimensions. For instance, anti‐elite and anti‐system attitudes can be considered aspects of the ‘antagonistic depiction of the polity’, while preference for direct democracy and majoritarianism are features of the populist conception of sovereignty. Typically, the operationalisation of this framework requires the identification and analysis of a set of narrower indicators in each of these dimensions.

This paper suggests moving away from the dichotomisation of populism and the assumption that objects can only be compared if they possess the same attributes (Sartori Reference Sartori1970: 1036–1038). Attributes can also be treated as conceptual continuums between negative (‘populist’) and positive (‘anti‐populist’) poles (Goertz Reference Goertz2006: 27–35, Figure 1).

Figure 1. Five‐dimensional framework with examples of dimensions and typical populist and anti‐populist features.

This approach helps incorporate a gradient conception of populism and identify varieties within populism. It is not incompatible with Sartori's ‘ladder of abstraction’ and allows setting thresholds if researchers wish to dichotomise attributes and pursue a classical categorisation. The framework does not prescribe a specific level of abstraction, some studies may adopt a more micro‐approach and focus on analysing specific features within one or several subdimensions, while others may assume a more macro‐angle and compare broader patterns in discourses or actions. Similarly, the five dimensions suggested here for their theoretical grounding and heuristic value, may be simplified, expanded or replaced depending on analytical needs and data availability.

‘Anti‐populist’ features are worth coding as they provide additional elements for comparison. Although ‘elitism’ is sometimes considered the opposite to populism (Bell Reference Bell1992; Mudde & Rovira‐Kaltwasser Reference Mudde and Rovira‐Kaltwasser2013: 152–153), its value as negative pole is methodologically limited within this framework, because ‘elitists’ usually embrace the antagonism ‘elite vs the people’, as well as utilise moral justifications and distorted depictions of society (Hawkins & Rovira‐Kaltwasser Reference Hawkins and Rovira‐Kaltwasser2017b: 515). Therefore the ‘anti‐populist’ categories proposed are closer to ‘pluralist’ or ‘liberal democratic’ standpoints (Hawkins Reference Hawkins2009; Pappas Reference Pappas2019).

Different research traditions may adapt this framework to the type of data and level of analysis they consider appropriate. It can be used, for instance, to study the supply‐side of populism via classical content analysis (Bauer Reference Bauer, Bauer and Gaskell2000) or discourse analysis (Van Dijk Reference Van Dijk1985) of manifestos, speeches and other political communications (Table 1). Coding rules and keywords may be defined to capture ‘populists’ and ‘anti‐populists’ features associated with each of the dimensions according to the specific context. For instance, the density of populist features in communications – number of references/1,000 words – can be analysed statistically (Figures A1–A4, Figures A7 and A8, Tables A1 and A2 in online Appendix). Qualitative methods may be used to assess the specific nature and intensity of populist discourses – themes, tone, usual tropes, and so on. The dimensions of this framework could be also used as basis for ‘holistic grading’ of texts (Hawkins Reference Hawkins2009).

Table 1. Example of adaptation of framework to discourse analysis

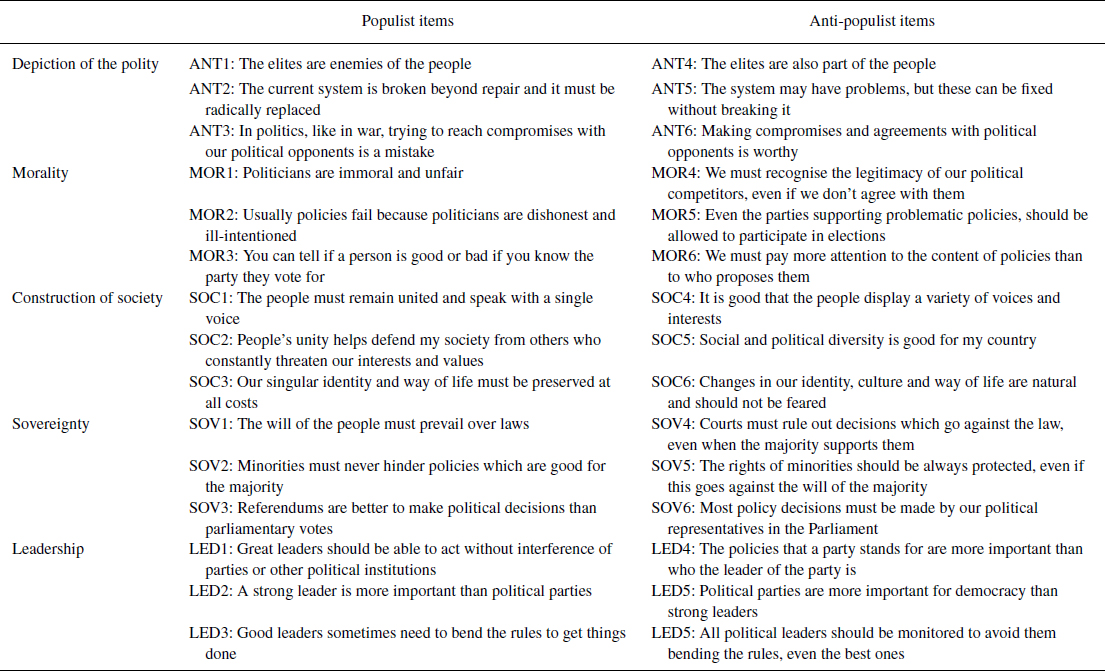

This framework can also be used to measure the demand‐side of populism via survey data (Akkerman et al. Reference Akkerman, Mudde and Zaslove2014; Castanho Silva et al. Reference Castanho Silva, Jungkunz, Helbling and Littvay2020). For example, citizens can be asked to rate their level of agreement with certain statements to capture and compare the intensity of certain ‘populist’ and ‘anti‐populist’ attitudes and beliefs (Table 2). These studies can help identify interactions between items, dimensions and other psychological, socio‐demographic or political variables. Such instruments require a previous check of content validity – expert panel analysis, internal consistency – Cronbach's alpha, latent structure – confirmatory factor analysis – and criterion‐related validity – regression analysis, t‐test, ANOVA, Pearson correlation.

Table 2. Examples of items for populist attitudes surveyFootnote 8

A major research challenge ahead is to better understand and map the network of interactions and intersections among these dimensions and the attributes which underpin them (e.g., online Appendix, Figure A5). Some of the characteristics of the model presented here resonate with a radial structure (Lakoff Reference Lakoff1987). For instance, populism may have a consensually accepted, but underspecified central core, which is inspired by prototypes and given meaning in context (Ostiguy Reference Ostiguy2010: 18–19). Subcategories or variants of populism may share some but not all the defining attributes of this core. However, this model does not fully match traditional radial structures from cognitive studies and could be better represented by a multilayered network structure. Subcategories may share defining attributes with each other and different dimensions and attributes may reinforce each other – as suggested in the description of dimensions.

Empirical research will help establish the relative intensity or prevalence of these dimensions/attributes and to what extent different varieties of populism rely on specific combinations or bundles of attributes. A hierarchy of dimensions and attributes may be also established; some may end up as considered jointly necessary or essential and others simply present in certain types of populism or specific contexts. Further research should be conducted to investigate the inner logic of articulation of the dimensions and attributes of populism. These may be independent dimensions and attributes that co‐variate due to other underlying factors (Figure 2(1)) or overlapping and mutually constitutive ones (Figure 2(2)).Footnote 5

Figure 2. Alternative visualisations of a multilayered network conceptualisation of populism.Footnote 9 [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Finally, it may be worth exploring to what extent the interactions between dimensions and attributes constitute a populist inner logic which underpins and gives consistency to the latent construct. Figure 3 provides some examples of how synergic interactions of these five dimensions can be observed empirically in attitudes and discourses of populist leaders and have been often reflected in theoretical characterisations of populism.

Figure 3. Examples of interactions between populism dimensions.

Typically, scales measuring populist attitudes are based on the analysis of ‘pure’ variables which try to capture a single attribute (Figure 4(1). However, some of these attributes associated with populism – for example ‘anti‐elitism’ and ‘preference for direct democratic tools’ – are also displayed by ‘non‐populist’ individuals or movements. Considering populism simply as the sum (or average) of its dimensions is methodologically problematic (Wuttke et al. Reference Wuttke, Schimpf and Schoen2020: 372). The utilisation of ‘intersection’ variables which articulate more than one of the attributes associated with populismFootnote 6 may be an operationalisation strategy to overcome this problem (Figure 4(2) and (3)).Footnote 7 These variables could increase the discriminatory capacity of the model and, from a theoretical standpoint, be closer reflections of the ‘logic of articulation’ of political ideas and discourses which sets populists’ subjects apart.

Figure 4. Alternative models based on use of intersection variables.

Concluding remarks

This article is an invitation to shift efforts from categorising subjects as ‘populists’ or ‘non‐populists’, into reaching a better understanding of what populism is, its multiple dimensions and the interactions among the components that underpin this latent construct. The first part of the article outlines some of the hindrances to cumulative progress in the literature. The field was from its inception plagued with sharp theoretical discrepancies and the term populism has been often stretched and conflated with the concept of nationalism. Many authors prioritised the analysis of specific populist parties and leaders, without a clear comparative angle or concern for conceptual travelling. Those who engaged more directly with the conceptualisation effort often disagreed on the true essence of the concept. Ontological disputes on whether populism is a thin ideology, a strategy, a discourse or a political style became recurrent.

This paper argues that these competing research approaches are complementary and could benefit from a concerted data generation effort. It proposes to shift the focus away from minimal definitions and classical categorisations and to embrace a multidimensional stance on populism. Populism can be construed as a higher order latent construct, made up from multiple lower order attributes. Although minimal conceptualisations of populism – focusing on one or a small set of attributes – facilitate the classification of subjects, they often fail to capture the empirical diversity in terms of populist ideas, discourses and practices, as well as the mutable nature of this phenomenon. A multidimensional approach, on the other hand, allows a better understanding of the phenomenon and its multiple manifestations or varieties.

Accordingly, the second part of this paper theoretically develops a new comparative framework based on five thematic dimensions: antagonistic depiction of the polity, morality, idealised construction of society, popular sovereignty and leadership. These dimensions, which synthetise the most influential conceptualisations in the field, can be considered interconnected lower order constructs composed of other subdimensions. This paper also suggests many interactions between populist attributes across these dimensions and some ways to disentangle populism and nationalism. For instance, while nationalists’ antagonism is always based on a horizontal or territorial conception of the in‐out group divide, populists usually, but not exclusively, adopt a vertical one. Nationalists may not seek radical change as populists do. Populists customarily rely on moral arguments to delegitimise ‘the other’ while nationalists may or not do it. Nationalist leaders have frequently justified their opposition to other countries as a matter of conflicting rational self‐interest, as realism in international relations suggests. Populists do not necessarily ground their conception of ‘heartland’ on national identity as nationalists do. Moreover, nationalists often do not share populists’ maximalist conception of sovereignty or their preference for direct democracy tools.

Finally, this framework implies moving away from a dichotomous consideration of subjects of analysis as ‘populists’ or ‘non‐populists’, to a research agenda which acknowledges the existence of degrees and varieties in populism. The multidimensional framework introduced here provides a heuristic template that can be adapted to various needs. The paper proposes some operationalisation avenues and examples of indicators for the analysis both of the supply‐side (via content and discourse analysis) and demand‐side of populism (via surveys). Although this model shares some similarities with a radial categorisation logic – populist attributes are not considered as jointly necessary conditions – the interaction observed among attributes suggest a multilayered network structure to be a more appropriate representation of the framework. Future research is needed to confirm whether these are independent attributes that co‐variate due to other underlying factors or mutually constitutive ones. Datasets generated following this or similar multidimensional approaches may be used in a variety of quantitative and qualitative studies, and contribute to conceptual debates, for instance, to create typologies and narrow down or expand existing definitions.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank all those who provided feedback on earlier versions of this paper and on the presentations of the multidimensional framework at the ECPR, APSA, ASEN and CES annual conferences. Special thanks to Francisco Panizza, Kenneth Roberts, Andrej Zaslove, Oscar Mazzoleni, José Antonio Olmeda, Encarna Hidalgo‐Tenorio and Martin Bull for their valuable insights on and advice. I also want to express my gratitude to the three anonymous reviewers and editors whose constructive comments have helped to refine several aspects of the manuscript.

This work is supported by the Autonomous Community of Madrid Talento Program.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Figure A1: Density of populist and anti‐populist references (per thousand words) in the political manifestos of Vox, Brexit Party, UKIP and RN.

Figure A2: Density of populist references of each of the five dimensions (per thousand words).

Figure A3: Evolution of density of populist features (per thousand words). Spanish Congress Speeches on Covid19 (24 March and 3 June 2020).

Figure A4: Evolution of density of populist features (per thousand words). Spanish Congress Speeches on Covid19 (March–June 2020).

Figure A5: Map of intersection (one‐line proximity) of codes in transcriptions of Spanish Parliamentary Speeches on the COVID19 crisis (25 March and 3 June).

Figure A6: Short texts: populist references per 1,000 words (all texts included).

Figure A7: Manifestos: populist references per 1,000 words (all texts included).

Figure A8: Populist references per 1,000 words and dates of publication.

Table A1: Short texts Catalan nationalist parties and SNP.

Table A2: Long texts analysed Catalan nationalist parties and SNP.