Introduction

This year marks a decade since the England Riots of 2011 and the subsequent introduction of the Troubled Families Programme. In this article we look back to the inception of the Troubled Families Programme, and the survey data and methodology used by the government to identify how many ‘troubled families’ existed in the UK and should be targeted by the programme. We critique the approach used to measure the number of troubled families, using the same data and analysis employed by the government to show why that methodology was flawed. We argue that this is important for the following reasons. First, it draws attention to the need for the careful application of quantitative methods when conducting evidence-based policy making, which can have implications for the budget allocated to the policy programme (crudely put, the cost of the policy intervention multiplied by the target number of policy recipients), as well as how the targeted population (‘troubled families’ in this case) are defined and hence viewed by policy makers, the media and the public. A reminder of the importance of definitional and measurement precision in the evidence used in policy making is also timely; something that needs continuous consideration in the climate of reactive policy making (particularly relevant given the speed of social change in a pandemic).

The first phase of the Troubled Families Programme ran from 2011-2015, targeting 120,000 troubled families, which is the statistical estimate that is the focus of this article. The second phase of the programme was expanded, running from 2015-2021, to target 400,000 troubled families. As we go on to show, the government’s methodology was more appropriately detailed than that used in phase 1. Most recently, the next phase of the programme – renamed ‘Supporting Families’ – has been announced and will run from 2021 (MHCLG, 2021). It is not clear from government documentation how many families this new phase will target.

Background to the Troubled Families Programme (phase 1)

In December 2011, in the aftermath of the riots that had happened across cities and towns in England in August of the same year, David Cameron spoke about plans to improve services for ‘troubled families’, a group the government presented as the root cause behind the riots. In his speech he indicated that the government knew exactly how many troubled families there were:

Last year the state spent an estimated £9 billion on just…120,000 troubled families across the country…. We are committing £448 million to turning around the lives of 120,000 troubled families by the end of this Parliament… (Cameron, Reference Cameron2011)

Knowing how many troubled families there were implied that the government already had a working definition of a ‘troubled family’, which Cameron went on to explain in his speech:

That’s why today, I want to talk about troubled families. Let me be clear what I mean by this phrase. Officialdom might call them ‘families with multiple disadvantages’. Some in the press might call them ‘neighbours from hell’. Whatever you call them, we’ve known for years that a relatively small number of families are the source of a large proportion of the problems in society. Drug addiction. Alcohol abuse. Crime. A culture of disruption and irresponsibility that cascades through generations. (ibid.)

In actual fact, these 120,000 families had been identified as a target for policy intervention a year earlier, when the government introduced ‘Community Budgets’. This policy allowed local authorities to pool resources and offer multi-agency, joined-up solutions for tackling families with complex social needs such as education, health and housing (DCLG, 2010). Following the riots, the focus of Community Budgets changed and the government launched the Troubled Families Programme, overseen by the Troubled Families Unit. The programme aimed to help the 120,000 troubled families to ‘turn their lives around’ through reducing youth crime and anti-social behaviour; getting children back into school, putting adults on a path back to work; and, reducing the high costs these families placed on the public sector each year (DCLG, 2012a). The focus now was much more on the problems that these families caused rather than the problems they were experiencing. The government produced figures to argue that troubled families cost the tax payer an estimated £9 billion per year, with the majority of that being spent on ‘protecting the children in these families and responding to the crime and anti-social behaviour they perpetrate’ (DCLG, 2012b).

Background to the troubled families statistic

The 120,000 troubled families statistic was not created alongside the introduction of the Troubled Families Programme. In fact it was taken from government research conducted by the Social Exclusion Task Force in 2007 (SETF, 2007a, 2007b). SETF had morphed out of the Labour government’s Social Exclusion Unit in 2006 to provide the government with strategic and policy advice on service provision for the most disadvantaged members of society – specifically those with combinations of entrenched social and economic hardships, such as unemployment, poor skills, low incomes and family breakdown (Cabinet Office, 2010).

In 2007, SETF led a cross-Whitehall review on ‘families at risk’; a shorthand term for families (with children) that had multiple, entrenched and reinforcing social and economic disadvantages. As part of the background research to this review, SETF conducted in-house research to help identify how many multiply-disadvantaged families there were. The SETF research found that 2 per cent of families with children in Britain experienced multiple disadvantage – defined as having five or more from a list of seven social and economic disadvantages – which equated to around 120,000 families in England.

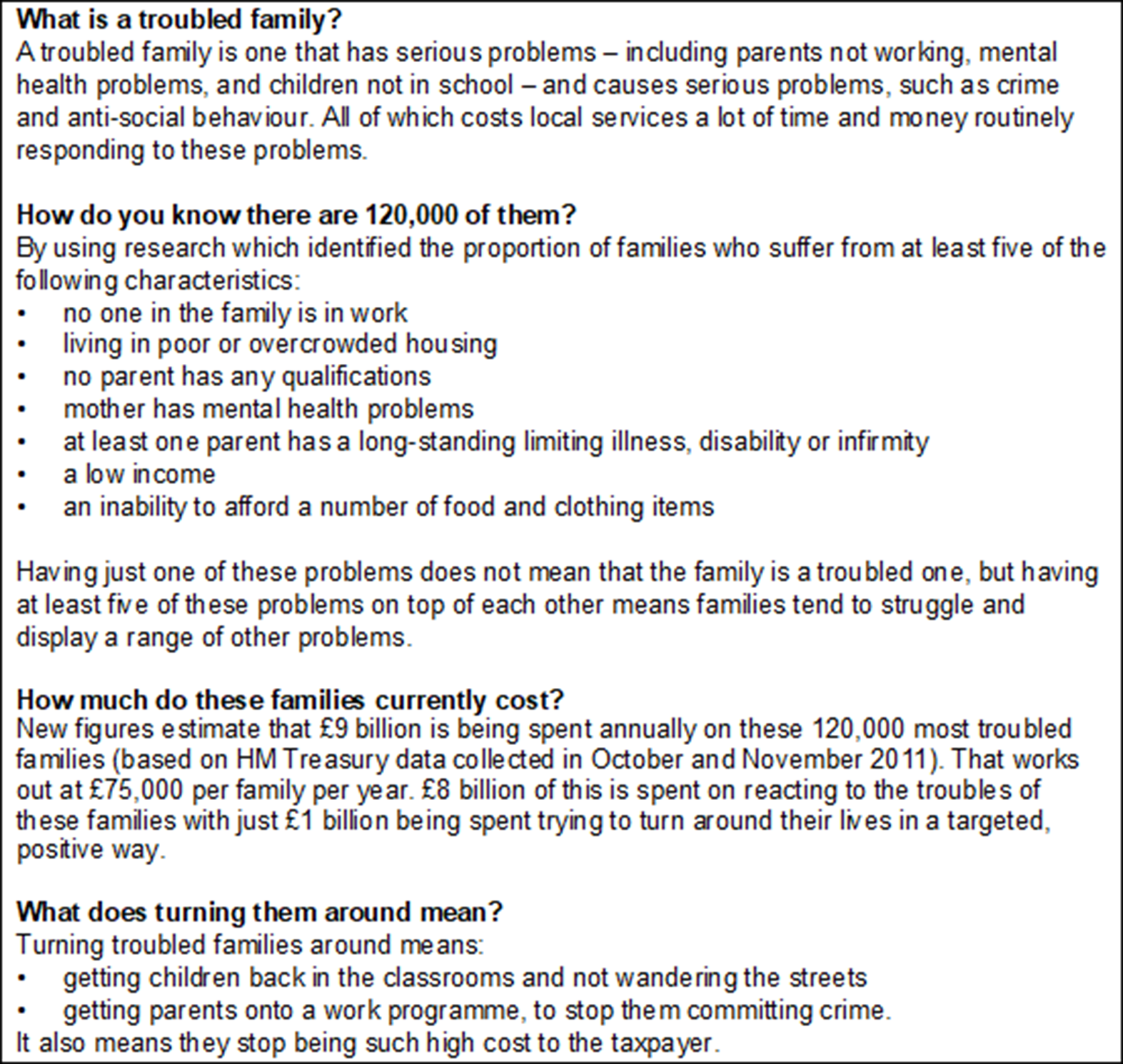

This statistic was then used by the Troubled Families Unit in 2012 to identify the number of troubled families. This can clearly be seen on the front page of the Troubled Families Unit website (Figure 1). It explained what a troubled family was and how many troubled families there were (Department for Education, 2011) – exactly replicating the methodology used in the SETF research.

Figure 1. Troubled families unit website front page

The Troubled Families Unit website explicitly stated that ‘A troubled family is one that has serious problems, including parents not working, mental health problems, and children not in school – and causes serious problems, such as crime and anti-social behaviour’ (bold text by authors for emphasis) (ibid.). However, there was no evidence from the SETF research to suggest that families experiencing multiple social and economic disadvantage were also displaying problematic behaviours such as crime and anti-social behaviour. Supplementary analysis by SETF did show that a range of poor child outcomes was more frequent for multiply-disadvantaged families but still only present for a minority of these families (Social Exclusion Task Force, 2007a). Even then the analysis only showed associations and not a causal relationship.

As is evident from the list of criteria used to characterise a troubled family on the Troubled Families Unit website, the measure identifies the number of families who experienced multiple social and economic disadvantage. It does not include any information about whether they are displaying problematic behaviours, such as crime and anti-social behaviour. Hence it does not match with the notion of what a troubled family is according to the Troubled Families Unit, and particularly the notion portrayed in government rhetoric associating troubled families with the causes of the riots. This apparent oversight has been discussed before, with the adoption of the SETF analysis by the Troubled Families Unit being widely condemned as a bad use of dataFootnote 1 (Crossley, Reference Crossley2016; Levitas, Reference Levitas2012; Portes, Reference Portes2012; Spicker, Reference Spicker2013).

In this article we reanalyse the same dataset used in the SETF analysis, and add to the existing discussion of the troubled families statistic by incorporating indicators of problematic behaviour, such as crime and anti-social behaviour, which were not included in the original analysis. Our overarching aims are twofold. First, we explore the validity of that original estimate, and discuss how well the measure of 120,000 troubled families fits with the government definition of what a troubled family is. We discuss why the SETF analysis was used as the basis of the 120,000 troubled families statistic given its obvious methodological limitations. Secondly, we explore the overlap between families experiencing multiple social and economic disadvantage and families that display problematic behaviour, such as crime and anti-social behaviour. We seek to answer how many of the 120,000 troubled families (erroneously measured by government as families with multiple social and economic disadvantages) were actually displaying the kinds of problematic behaviour implied by government rhetoric.

Methodology

To explore the overlap between multiple social and economic disadvantage and problematic behaviour we revisit the same dataset used in the SETF research subsequently adopted as the 120,000 troubled families statistic – the Families and Children Study (FACS). Using this same dataset, we aim to illustrate the additional insights that further analysis could have provided the government when evidencing the number, and behaviours, of troubled families prior to the inception of the Troubled Families Programme.

The data: Families and Children Study (FACS)

The Families and Children Study (FACS) is a panel survey of the living standards of British families with dependent children. The study began in 1999 and interviewed approximately 7,000 familiesFootnote 2 annually until 2008. Information was mainly collected from the mother (or main carer) about herself, her partner (where present) and her children. Children aged ten to fifteen years were also asked to answer a self-completion questionnaire away from their parents’ gaze. The survey covered topics such as income, work, housing, health, education and child behaviours (Hoxhallari et al., Reference Hoxhallari, Conolly and Lyon2007). We use FACS data from the 2005 survey – the same dataset used in the SETF research.

Measuring multiple social and economic disadvantage – replicating the 120,000 troubled families statistic

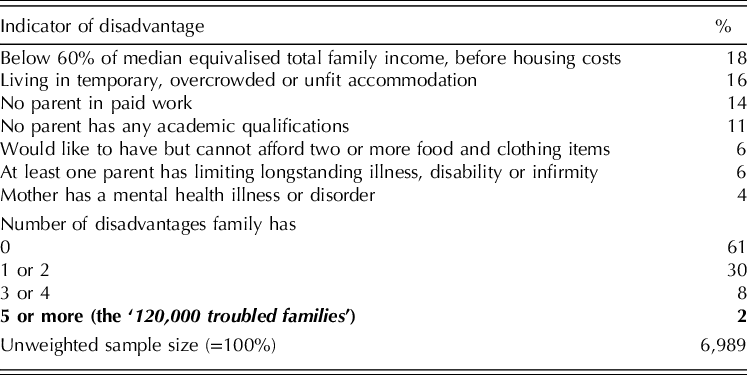

First, the seven indicators of social and economic disadvantage were reproduced to match the analysis produced by SETF (SETF, 2007a, pp.62-64). The percentage of families with each form of disadvantage varies from 4 per cent (mother had mental health illness or disorder) to 18 per cent (family living on low income) (Table 1). The 120,000 troubled families statistic is derived from the families that had five or more disadvantages (2 per cent). The total number of families with dependent children in Britain in 2005 was approximately 7 million (Hoxhallari et al., Reference Hoxhallari, Conolly and Lyon2007) and 2 per cent of this is 140,000, which provides an estimate of the number of families with five or more disadvantages in Britain. This number was recalculated for England as 117,000 families. When the Troubled Families Unit used this number it was rounded up to give the 120,000 troubled families statistic (Department for Education, 2011).

Table 1 Percentage of families with separate and multiple indicators of social and economic disadvantage

Base. Families with dependent children in Britain

Source. Families and Children Study (FACS) 2005, authors’ own calculations

Although the SETF analysis of families with multiple social and economic disadvantages was not designed to identify the number of ‘troubled families’, the methodology used was not without criticism. It provides no theoretical basis to the choice of the seven disadvantage indicators selected or the way they were constructed. Furthermore, the thresholds used to measure each of the disadvantage indicators were not explained; for example, why it is important to lack two or more food and clothing items rather than three or more. A similar argument can be made with the threshold used to identify multiple social and economic disadvantage. There is no justification as to why having five or more disadvantages is critical – rather than having, say, four, or six disadvantages. Additionally, a simple count assumes that each disadvantage has the same impact on the family, and that the compounding effect on the family is linear.

The SETF report claimed that this analysis helped underpin a focus on families facing a number of social and economic disadvantages such as poverty, bad housing and other forms of deprivation – which arguably it does. However, the report also suggests that these are families that displayed signs of ‘poor parenting’ and ‘poor models of behaviour that can have an impact on children’s development and wellbeing, with significant costs for public services and the wider community’ (SETF, 2007a, p1). However, no evidence was provided to support this claim.

Despite the criticisms of the SETF research, we have replicated their measure here, using the same FACS data, in order to examine how many of these families displayed problematic behaviour, particularly the types of behaviour used in government rhetoric to describe troubled families, such as criminal and anti-social behaviour.

Measuring ‘problematic behaviour’

Despite the 120,000 troubled families statistic being based on a definition of multiple social and economic disadvantage that did not include any measure of problematic behaviour, such as crime and anti-social behaviour, the FACS survey did in fact collect such information. We align our approach to measuring problematic behaviour with that of the Troubled Families Programme itself. The Troubled Families Programme used a payment-by-results system to incentivise local authorities to ‘turn around’ troubled families. Local authorities were told how to identify ‘troubled families’ in their local area and given a list of expected numbers of families by the Troubled Families Programme (extrapolated from the 120,000 troubled families statistic). Troubled families were identified according to four criteria:

-

1. Involved in crime and anti-social behaviour

-

2. Had children not in school

-

3. Had an adult on out of work benefits

-

4. Caused high cost to the public purse

A troubled family should meet all of the first three criteria. However, if the number of troubled families identified was less than the number expected, a local authority was instructed to use their discretion to include other families who met any two of the first three criteria plus criteria four (DCLG, 2012c). In this article we attempt to measure the Troubled Families Programme definition (above) with the FACS data. Where there was no clear match between the Troubled Families Programme and FACS, we consider what was implied by government rhetoric, and reciprocated in certain elements of the media, as problematic behaviours: in other words, the Troubled Families Programme criteria 1 and 2 – crime and anti-social behaviour, and truanting.

Below we provide more detail of the criteria used by the Troubled Families Programme to identify troubled families along with its closest operationalisation using data from the FACS survey. As discussed earlier, the emphasis of the Troubled Families Programme, and the criteria used to define a ‘troubled family’, changed in later years as the programme expanded (DCLG, 2014). We use the initial definition of a ’troubled family’ from the inception of the Troubled Families Programme in 2012 (phase 1) as this was the definition used for the 120,000 troubled families statistic.

1. Involved in crime and anti-social behaviour

Troubled Families Programme criteria:

Identify young people involved in crime and families involved in anti-social behaviour, defined as:

– Households with one or more under eighteen-year-old with a proven offence in the last twelve months

AND/OR

– Households where 1 or more member has an anti-social behaviour order, anti-social behaviour injunction, anti-social behaviour contract, or where the family has been subject to a housing-related anti-social behaviour intervention in the last twelve months (such as a notice of seeking possession on anti-social behaviour grounds, a housing-related injunction, a demotion order, eviction from social housing on anti-social behaviour grounds – or comparable measure) (DCLG, 2012c, p.4)

‘Equivalent’ indicator in FACS:

-

Mother (main carer) reports child (aged eight to eighteen years) has had a formal warning, fine or conviction from the police within the last twelve months

2. Had children not in school

Troubled Families Programme criteria:

Identify households affected by truancy or exclusion from school, where a child:

– Has been subject to permanent exclusion; three or more fixed school exclusions across the last three consecutive terms;

OR

– Is in a Pupil Referral Unit or alternative provision because they have previously been excluded;

OR

– Is not on a school roll;

AND/OR

– A child has had 15% unauthorised absences or more from school across the last three consecutive terms (DCLG, 2012c, p.4)

‘Equivalent’ indicator in FACS:

-

Mother (main carer) reports child (aged five to fifteen years) has been suspended at least once, expelled, or played truant from school for at least half a day in the last twelve months

3. Had an adult on out of work benefits

Troubled Families Programme criteria:

Identify households which have an adult on Department for Work and Pensions out of work benefits

– Employment and Support Allowance (only introduced in 2008)

– Incapacity Benefit

– Carer’s Allowance (Invalid Care Allowance)

– Income Support

– Jobseekers Allowance

– Severe Disablement Allowance (DCLG, 2012c, p.5)

‘Equivalent’ indicator in FACS:

-

Family claims at least one out of work benefit (Income Support; Jobseekers Allowance; Incapacity Benefit; Severe Disability Allowance; Carer’s Allowance)

4. Cause high cost to the public purse

Troubled Families Programme criteria:

Use this local discretion filter to add families that meet any two of the above three criteria (1. Involved in crime and anti-social behaviour; 2. Had children not in school; 3. Had an adult on out of work benefits), and are a cause for concern. Those who are high cost and those with health problems could include:

Families containing a child who is on a Child Protection Plan or where the local authority is considering accommodating them as a looked after child

Families subject to frequent police call-outs or arrests or containing adults with proven offences in the last twelve months, such as those who have been in prison, prolific and priority offenders, or families involved in gang-related crime

Families with health problems. Particular priority health problems which you should consider include:

-

– Emotional and mental health problems

-

– Drug and alcohol misuse

-

– Long term health conditions

-

– Health problems caused by domestic abuse

-

– Under eighteen conceptions (DCLG, 2012c, p.4)

‘Equivalent’ indicator in FACS:

-

Family has used social/welfare servicesFootnote 3 in last twelve months OR Mother (or main carer) has mental health problem OR At least one parent has long-term limiting health problem OR Mother drinks more than thirty-five units of alcohol every week OR Teenage mother

The range of behaviours captured in FACS reflects, to some degree, the broad criteria targeted by the Troubled Families Programme. However it is clear that not all of the criteria are captured in the survey. For example, FACS does not ask parents about their own anti-social behaviour (criterion 1), and hence we can only consider the unlawful behaviours of children. Nevertheless this does reflect much of the government rhetoric after the riots and during the introduction of the Troubled Families Programme, which focused on the deviant behaviour of children and young people in particular (Churchill, Reference Churchill, Foster, Brunton, Deeming and Haux2015). Nor does FACS capture the more extreme high cost behaviours such as health issues caused by domestic abuse, and drug misuse (criterion 4).

It is also important to point out that some of the FACS indicators are far more lenient than the corresponding Troubled Families Programme definition. For example, the FACS indicator for criterion 2 ‘Had children not in school’ includes ‘truanting from school for a single half day in the past twelve months’, whereas the Troubled Families Programme focuses on children with more persistent or permanent records of not being at school. Consequently, our estimate of this from FACS is very likely to be an overestimate of that implied by the Troubled Families Programme.

Analytical approach

The analysis was carried out using FACS data on families with dependent children in Britain in 2005, where a dependent child was defined as any resident child aged sixteen or under, or aged seventeen or eighteen and in full-time education. We re-constructed the measure of multiple social and economic disadvantage used for the 120,000 troubled families statistic, along with indicators that approximate definitions used in the Troubled Families Programme. We explored the associations between multiple social and economic disadvantage and Troubled Families Programme criteria descriptively. Using logistic regression we specifically investigated the association between multiple social and economic disadvantage and problematic behaviours, such as crime and anti-social behaviour, when controlling for standard socio-demographic characteristics of families. The FACS data was downloaded from the UK Data Service (NatCen/DWP, 2011) and analysed with the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS).

Results

How many families matched the Troubled Families Programme criteria?

The number of families displaying behaviours that approximate the Troubled Families Programme conditions (either meets all of criteria 1-3, or meets two of criteria 1-3 and 4) was approximately 2 per cent of all familiesFootnote 4 (Table 2).

Table 2 FACS indicators of the Troubled Families Programme criteria

Base. Families with dependent children in Britain

Source. Families and Children Study (FACS) 2005, authors’ own calculations

Focussing more on problematic behaviours (criteria 1 and 2), just 1 per cent of families had a child that had a warning, fine or conviction from the police, and 5 per cent of families had a child who had been suspended, expelled or played truant from school (predominantly the latter, for at least half a day in the last twelve months). Higher proportions of families were claiming out of work benefits (16 per cent) or accessing social/welfare services (22 per cent), reflecting levels of disadvantage and the prevalence of families in scope of receiving such support in society.

It is also worth remembering that the FACS indictors do not map perfectly onto the Troubled Families Programme definitions. Often the indicators are a softer measure than the Troubled Families Programme proposed, meaning these are likely overestimates of the troubled families definition.

How many families experiencing multiple social and economic disadvantage (the 120,000 troubled families) were displaying problematic behaviours?

Putting aside measurement differences, the percentage of all families coming under the Troubled Families Programme definition was actually very similar to the percentage of families who experienced multiple social and economic disadvantages – 2 per cent. The question that we seek to answer here is whether, according to the FACS data, these are the same families – in other words, were the multiply-disadvantaged families used as the basis for the 120,000 troubled families statistic the same set of families implied as the perpetrators of problematic behaviour?

Table 3 shows that, according to the FACS data, only a small proportion (one in six, or 13 per cent) of the 120,000 troubled families actually matched our approximation of the Troubled Families Programme criteria. Furthermore, focusing on those behaviours that the government highlighted as particularly ‘problematic’, only 6 per cent of the 120,000 troubled families had children involved in crime and anti-social behaviour, and only 14 per cent had children not in schoolFootnote 5

Table 3 Percentage of families displaying Troubled Families Programme criteria according to the number of social and economic disadvantages families had, cell per cent

Notes.

1. Involved in crime and anti-social behaviour: Family with child (aged 8-18 years) who has had warning, fine or conviction from the police in the last 12 months

2. Had children not in school: Family with child (aged 5-15 years) who has been suspended, expelled or played truant on at least one half-day in the last 12 months

3. Had an adult on out of work benefits: Family claims at least one out of work benefit (Incapacity Benefit, Carer’s Allowance, Income Support/Jobseekers Allowance, Severe Disablement Allowance)

4. Caused high cost to the public purse: Family has used social/welfare services OR Mother (or main carer) has mental health problem OR At least one parent has long-term limiting health problem OR Mother drinks more than 35 units of alcohol in an average week OR Teenage mother

Base. Families with dependent children in Britain

Source. Families and Children Study (FACS) 2005, authors’ own calculations

This is not to suggest the absence of an association between multiple social and economic disadvantage and problematic behaviours such as crime, anti-social behaviour and truancy – families with more social and economic disadvantages were clearly more likely to be displaying these problematic behaviours. This finding holds for each of the four criteria identified by the Troubled Families Programme, and in particular for criteria 3 and 4 because they match closely with the types of social and economic disadvantage captured by the SETF definition. Workless and low income families are likely to be claiming out-of-work benefits (relevant to TFP criterion 3), and disproportionately likely to have long-term health issues (relevant to TFP criterion 4), and families with a number of social and economic disadvantages are likely to be using social or welfare services (relevant to TFP criterion 4). It is clear then that the Troubled Families Programme headline statistic – that there were 120,000 troubled families – was much more likely to be capturing families with multiple social and economic problems than families displaying problematic behaviours such as crime and anti-social behaviour. This point is supported by the government’s own independent evaluation of the Troubled Families Programme. Local authority data showed that just over one in ten families on the Troubled Families Programme had an adult or child with a police caution or conviction, and a similar proportion were involved in anti-social behaviour (DCLG, 2017).

What is the association between multiple social and economic disadvantage and problematic behaviour, controlling for other characteristics of families?

In a final step we used logistic regression analysis to assess the relationship between multiple social and economic disadvantage and problematic behaviour, when controlling for some key socio-demographic and geographic variables. Here we focus on problematic behaviour of children because, as noted above, much of the rhetoric surrounding the 120,000 troubled families was concerned with these types of behaviours. Also, as previously discussed, these indicators were not included in the original government measure, and hence this analysis can be used to further explore the strength of the link between social and economic disadvantage and problematic behaviour

We ran a set of regression models where the outcome was one of:

-

Family had a child involved in crime and anti-social behaviour: Family with child (aged eight to eighteen years) who has had warning, fine or conviction from the police in the last twelve months (yes/no)

-

Family had a child not in school: Family with child (aged five to fifteen years) who has been suspended, expelled or played truant on at least one half-day in the last twelve months (yes/no)

-

Family had a child involved in crime and anti-social behaviour and family had a child not in school (yes/no)

Each outcome was regressed on a measure of the number of social and economic disadvantages a family had, defined as none, one or two disadvantages; three or four disadvantages; or, five or more. The models control for standard socio-demographic characteristics of families – family type, number of dependent children, age of youngest child, ethnic group of mother/carer, and geographic location. These models are not an attempt to identify the main drivers of problematic behaviour – many of which were not collected as part of FACS, such as low empathy, family conflict, associating with delinquent peers, and experiencing feelings of alienation (Ross et al., Reference Ross, Duckworth, Smith, Wyness and Schoon2011) – but are instead a further exploration of the relationship between social and economic disadvantage and problematic behaviour. Results are presented in Table 4.

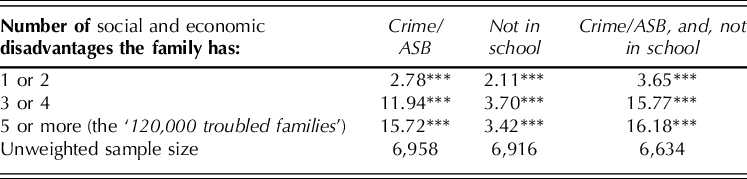

Table 4 Families with children involved in crime/anti-social behaviour, and/or children not in school, Logistic regression, Odds ratios

Notes. Models control for: family type, number of dependent children, age of youngest child, ethnic group of mother/carer, and geographic location

Crime/ASB: Family with child (aged 8-18 years) who has had warning, fine or conviction from the police in the last 12 months

Not in school: Family with child (aged 5-15 years) who has been suspended, expelled or played truant on at least one half-day in the last 12 months

***p<0.001

Base. Families with dependent children in Britain

Source. Families and Children Study (FACS) 2005, authors’ own calculations, full model outputs available from authors on request

The regression analysis confirms the descriptive analysis presented in the previous table, that, even when controlling for a standard set of socio-demographic characteristics of families, there is a statistically significant association between multiple social and economic disadvantage and forms of problematic behaviour. Having between one or two social and economic disadvantages increases the likelihood of having a child involved in crime or anti-social behaviour, and/or a child not in school (compared to having none of the disadvantages). The likelihood of a family having a child with problematic behaviour increases the more social and economic disadvantages a family had. In particular, the odds increase considerably for families with three or four (and five or more) disadvantages for the crime/anti-social behaviour outcomes. The odds of a child from a family with five or more disadvantages being involved in crime or anti-social behaviour (measured in FACS as who has had a warning, fine or conviction from the police in the last twelve months) is nearly sixteen times the odds of a child from a family with no disadvantages being involved in crime or anti-social behaviour.

However, despite large odds ratios suggesting sizeable associations between multiple social and economic disadvantage and problematic behaviours, it is important to remember that only a very small minority of families with five or more disadvantages displayed such behaviours – only 6 per cent had a child who had a warning, fine or conviction from the police, and only 14 per cent had a child who had been suspended, expelled or played truant (Table 3).

Discussion

This research has reaffirmed that the 120,000 troubled families statistic was actually taken from government research designed to measure families with multiple social and economic disadvantages (SETF, 2007a; SETF, 2007b) rather than families that fit the original Troubled Families Programme criteria. As others have pointed out, the government research contained none of the indicators of problematic behaviour that were seen to be at the forefront of the rhetoric surrounding the Troubled Families Programme – namely, families displaying criminal and anti-social behaviour (Crossley, Reference Crossley2016; Levitas, Reference Levitas2012; Portes, Reference Portes2012; Spicker, Reference Spicker2013). Our reanalysis of the same dataset has also shown that although families with multiple social and economic disadvantages were at an increased risk of displaying problematic behaviours, such as crime and anti-social behaviour, only a small minority did so. Not only did the government analysis used to estimate the number of troubled families not include indicators of problematic behaviour, such as crime and anti-social behaviour, when the measure is recalibrated to better reflect that definition, it shows that only a small number of families that experienced multiple social and economic disadvantage also displayed problematic behaviour. For example, only 6 per cent of families with five or more social and economic disadvantages had children involved in crime and anti-social behaviour, and only 14 per cent had children not in school. As only a minority of families with multiple social and economic disadvantages displayed problematic behaviours, it is difficult to argue that multiple disadvantage is a key driver of these behaviours. As Sayer (Reference Sayer2017: 160) states, ‘…(multiple) difficulties do not necessarily lead to the pathologies highlighted in the TFP discourse: the relationship is probabilistic rather than deterministic’.

Given the relatively small overlap between multiple social and economic disadvantage and problematic behaviour, we have to consider other reasons why the SETF research was used as the headline statistic for the Troubled Families Programme. One argument is that the use of the SETF research is an example of ‘policy-based evidence’ (Cairney, Reference Cairney2019). The government’s strategy to tackle crime and anti-social behaviour, using research that underpinned family policy making, represents the continuation of a long history of government interest in the monitoring and regulating of families that are perceived to be the source of a number of social problems in society (Gregg, Reference Gregg2010). In relatively recent times governments have labelled these families as ‘problem families’, ‘the underclass’, examples of ‘broken Britain’, ‘chaotic families’ (Macnicol, Reference Macnicol2017; Lambert, Reference Lambert2019), and more recently, ’families with complex needs’ and ‘troubled families’ (Cameron, Reference Cameron2010). Many of the philosophies underpinning the labelling of these families have had a similar focus; that of poverty, worklessness, delinquency, unworthiness, inter-generational continuities, and the social and economic cost to society (Welshman, Reference Welshman2013; Lambert and Crossley, Reference Lambert and Crossley2017). This vision was continued into the Conservative-led coalition government’s family policies, with troubled families characterised as dysfunctional parents negatively impacting on their children’s outcomes. Consequently these families were targeted in an attempt to change behaviour and get families ‘back on track’ (Eisenstadt and Oppenheim, Reference Eisenstadt and Oppenheim2019).

This perspective is supported when referring back to the policy report from which the SETF research was taken. Whilst the focus of that report, which predated the Troubled Families Programme, was on the complex needs of a small minority of families who faced multiple and entrenched social and economic problems, elements of it hinted at a recognition of a group of ‘problematic’ families (SETF, 2007a). The narrative described the outcomes for children growing up in families with multiple social and economic disadvantages, some of which included ‘problematic behaviours’ such as school exclusion, and being in trouble with the police (the SETF report drew on evidence from HMT/DfES, 2007).

Linking multiple social and economic disadvantage to problematic behaviour, such as crime and anti-social behaviour, risks distorting and stigmatising the actions of the poor (Levitas, Reference Levitas2012; Hoggett and Frost, Reference Hoggett and Frost2018). Welshman (Reference Welshman2013) has raised the issue of the Troubled Families Programme problematising certain family conditions, such as mental health and worklessness, in particular. As Butler (Reference Butler2014: 420) says ‘It is what the Troubled Families Programme has contributed to our thinking about those in troubled families that matters, not what it has done for the families concerned, nor even what it has done to make savings from the public purse’. Conflating data on families with multiple social and economic disadvantages with rhetoric about problematic behaviour led to the stigmatising of these families in both policy and media circles (Crossley, Reference Crossley2018).

Another, albeit more practical, reason that the SETF research was used as the estimate of the number of troubled families is that the government did not have time to undertake, or commission, a new piece of analysis to calculate this number. The Troubled Families Programme was established in 2012 as a reaction to the England riots which began in early August 2011. Just days later David Cameron spoke about the government ‘fightback’, and the first public mention of the government’s commitment to ‘turn around the lives of the 120,000 most troubled families in the country’ (Cameron, Reference Cameron2011). Given that there was only very limited time for new research, the statistic had to be taken from existing evidence. The 120,000 statistic was ready-made, having been previously used by government to identify families with complex needs for the ‘Community Budgets’ intervention – one of the suite of family policies used to target social problems such as health and housing, but which did include mention of anti-social behaviour (DCLG, 2010).

A headline statistic on the number of troubled families may have been seen to strengthen the government’s response to the riots at a time when the public were looking for an authoritative reaction. It enabled the government to take control of the narrative surrounding the riots and its causes, particularly given the existence of competing narratives, some of which represented a significant threat to the government (for example, that the riots were a natural response to the government’s austerity programme). The government located the cause as external to current government policy, and by evidencing the exact number of ‘troubled families’ gave significant credibility to this claim. It was an acknowledgement that the government not only knew that these troubled families existed, but also that they knew how many of them there were.

It is important to note that the operational definition of a troubled family has changed since the inception of the Troubled Families Programme. In June 2013 the Government announced plans to administer the Troubled Families Programme for a further five years from 2015/16 (DCLG, 2013)Footnote 5 . To be eligible for phase 2 of the programme a family needed to have at least two of the following six problems:

-

1. Parents and children involved in crime or anti-social behaviour

-

2. Children who have not been attending school regularly

-

3. Children who need help: children of all ages, who need help, are identified as in need or are subject to a Child Protection Plan

-

4. Families affected by domestic violence and abuse

-

5. Adults out of work or at risk of financial exclusion or young people at risk of worklessness

-

6. Parents and children with a range of health problems (including but not exclusively drug or alcohol abuse)

This approach used an expanded definition of a troubled family which included domestic violence and ‘children in need’, as well as identifying families with health problems. Given that only two of the six criteria are needed to be characterised as a troubled family, the likelihood of labelling as ‘problematic’ families with multiple social and economic disadvantages remains – for example, workless families with health problems (criteria 5 and 6). The definition therefore continues to suggest that social and economic disadvantage should be viewed as problematic behaviours in the same way as crime and anti-social behaviour is.

As part of this plan the Government calculated that an additional 400,000 families across England were in scope of the programme. This involved a new calculation of the number of troubled families, using a more detailed methodology than was used to identify the original 120,000 troubled families. This time indicators of problematic behaviour such as crime and anti-social behaviour were incorporated into the derivation of the headline statistic that identified how many troubled families the programme was targeting. The calculation incorporated analysis of FACS data, using some of the measures we have included in our research. Where FACS did not contain data to measure particular criteria – for example, criterion 4 ‘Families affected by domestic violence and abuse’ – the gaps were filled using other surveys and administrative data (DCLG, 2014). This raises the question as to why this more detailed methodology was not used for the initial estimation of the number of troubled families when the Troubled Families Programme was announced in 2011. Instead the SETF research on families with multiple social and economic disadvantages was used, which sparked the criticisms that followed.

Conclusion

This article has reiterated how the 120,000 troubled families statistic was taken from government research on families with multiple social and economic disadvantages. As others have pointed out previously, as a consequence of this, the methodology behind the 120,000 troubled families statistic included no indicators of problematic behaviours such as crime and anti-social behaviour.

Our reanalysis of the data behind the 120,000 troubled families statistic has shown that although families with multiple social and economic disadvantages were at an increased risk of displaying problematic behaviour – such as crime and anti-social behaviour, and truancy – only a small minority did so. Louise Casey, Head of the Troubled Families Programme, acknowledged that the 120,000 troubled families statistic was ‘about families with multiple and complex needs rather than families that caused problems’ (Casey, Reference Casey2013) and at the Public Accounts Committee hearing into the evaluation of the Troubled Families Programme, Casey defended the government’s use of the 120,000 troubled families statistic, saying:

…The 120,000 figure – which a number of critics, but not too many, have a problem with – was the starting point of some of the difficulties for people involved in criticising the programme.…In fairness to the Government, I would say the best proxy they had was the old Social Exclusion Unit data – the family survey data – which I think was then owned by the Department for Education, which gives you, more or less, this figure of 120,000 across a load of cohorts. I do not think it is unreasonable that when we were developing with them what they wanted to evidence by ‘turned around’, they took the 120,000 figure. We then went out to local authorities and said, ‘In terms of kids who aren’t in school, families that are committing antisocial behaviour, and worklessness, as well as another high-cost indicator should you need it, can you stack that number up?’ – and they could. The criticism that has sometimes come in is that we were criminalising troubled families. (House of Commons, 2016b)

The government could have staved off some methodological criticism of the use of the 120,000 troubled families statistic if they had incorporated measures of ‘problematic behaviour’ into their calculation of the number of troubled families. Our analysis has shown that a more thorough analysis of the FACS data prior to the introduction of the Troubled Families Programme would have provided the government with evidence of the relatively weak link between ‘multiple disadvantage’ and ‘problematic behaviour’. This in turn may well have changed the basis of economic calculations that underpinned the programme, and some of the misleading rhetoric around ‘troubled families’.

The SETF research should not have been used by the government to quantify the number of troubled families that were the focus of the original Troubled Families Programme. The statistic does not capture the definition it implies. Furthermore it implies an association between multiple social and economic disadvantage and problematic behaviours that evidence from that same dataset suggests is weak at best. Nor should the troubled families statistic have been the basis for which local authorities were told how many troubled families to ‘turn around’. Nor should that number have been used to help cost the funding required for the Troubled Families Programme. The 120,000 troubled families statistic was not a good foundation for policy making.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by a British Academy/Leverhulme Small Research Grant. The research benefited from the advice of a small advisory group comprised of Professor Dick Wiggins, Dr Stephen Crossley, Matt Ford and Jonathan Portes. We are very grateful for their helpful input. We would also like to thank the reviewers for their careful, constructive and insightful comments.