Introduction

Chapters 10–15 in Tosefta Soṭah contain the longest, most elaborated aggadic unit in the Tosefta. It parallels m. Soṭah 9:9–15 but is ten times longer. It comprises various units that seem to be connected only loosely: the biblical righteous figures (chs. 10–12); various revelations and appearances of the holy spirit and divine echo (ch. 13); and the effects of the destruction and the calamities of the present (chs. 14–15).

In the following I argue that this text forms a coherent unit. It combines apocalyptic, priestly and wisdom themes in a manner that is unprecedented in rabbinic literature, but is similar to several Second Temple texts. Specifically, there is a meticulous resemblance between chapters 10–13 and Ben Sira’s “Praise of the Fathers” (chs. 44–50). Both texts begin with the prediluvian period, move chronologically through a series of biblical heroes, and end with an extensive unit which eulogizes Simeon the High Priest. The Tosefta, however, is further reworked so as to also include apocalyptic themes: mediated prophecy (bat qol), crisis, and, ultimately, an eschatological solution.

Since the literary structure of our text was not understood, its sharp exceptional message was not acknowledged. The redacted unit tells a tale of perpetual decline from the biblical golden age to the rabbis’ own age of destruction, together with its eschatological remedy. It combines priestly and apocalyptic themes to form an alternative to the standard rabbinic metanarrative of the transfer from prophecy to Torah.

The article advances as follows: the first section discusses chapters 10–13 and their meticulous connections with (and influence by!) Ben Sira; the second section compares the complete composite unit (chs. 10–15) to the parallel Mishnah; and the third section examines the apocalyptic themes found in our text and their significance. Along the way we discuss the history of various themes appearing in the Tosefta: the holy spirit, the rabbinic chain of transmission, the revelatory function of the Temple, and more. We will end with possible implications of our analysis for two larger issues: the relationship between rabbinic ethos and three major strands in Second Temple Judaism (priestly traditions, wisdom literature, and apocalypticism) and the literary relationship between the Mishnah and the Tosefta.Footnote 1

Chapter 10–13 and Ben Sira’s “Praise of the Fathers”

Chapters 10–12 in Tosefta Soṭah detail the deaths of the righteous biblical figures and the benefits lost with each of them.Footnote 2 It is made of various sources, as noted by scholars. Citations from Seder ‘Olam were detected by Chaim Milikowsky.Footnote 3 The two traditions about John Hyrcanus and Simeon the high priestFootnote 4 are similar to narratives found in Josephus, and Vered Noam argues that both stem from a shared priestly source.Footnote 5 There are also two lengthy passages on Moses and Samuel, analyzed by Yoav Rosenthal as appendices.Footnote 6 Lastly, there are various parallels to Tannaitic midrashim and barayitot, as noted by Saul Lieberman.Footnote 7

But all these traditions, I will argue, are joined together in a consistent and coherent manner, independently of their diverse sources. Let us then begin uncovering the overall structure of this unit. Chapters 10–12 narrate a series of biblical figures and the benefit each of them brought to the world. These chapters are ordered chronologically from Methuselah (10:1) to Haggai, Zechariah, and Malachi, the last prophets (13:3). But they also combine thematic subdivisions: the unit from Abraham to Moses (10:1–11:3) focuses on abundance and hunger;Footnote 8 from Joshua to Samuel (11:4–5), on victory and enslavement; whereas from Elijah (12:5) onwards, on the holy spirit and its loss.Footnote 9

Chapter 13 moves forward in time to the events of the Second Temple period— the destruction of the first Temple, the latter prophets at the beginning of the Second Temple, and then on to Simeon the righteous, and John “the high priest” (Hyrcanus) in the Hellenistic period. It thus continues the chronological sequence of chapters 10–12. The move from the latter prophets at the beginning of the Second Temple directly to the Hellenistic period is similar to what we find in book 11 of Josephus’ Antiquities, and is instigated by a shared historical conception about the shortness and insignificance of the Persian period.Footnote 10

A well-defined theme emerges in chapter 13, however, apart from a continuation of the chronological sequence. It is a tractate about the holy spirit.Footnote 11 It continues (and amplifies) the appearance of this theme at the end of chapter 12 with regard to Elijah. It narrates a story of continual deterioration of the revelatory mechanisms: the biblical oracular mechanism of ‘urim and tummim (see Exod 28:30; Num 27:21) ceased immediately at the destruction of the First Temple,Footnote 12 and then, after the deaths of Haggai, Zechariah, and Malachi at the beginning of the Second Temple period, the holy spirit ended. This is also the context of the hiding of the Ark by King Josiah in 13:1, “so it not be exiled to Babylon,” for the ark was the locus of the revelation in the Holy of Holies.Footnote 13

But revelation itself does not end with the destruction. A divine voice, echo (bat qol),Footnote 14 emerges as the holy spirit’s replacement, while simultaneously serving as a testimony to the identity of those who still possess (or are worthy of possessing) that spirit. Here is the relevant text:Footnote 15

When the first Temple was destroyed, kingship ceased from the house of David, and ‘urim and tummim ceased, and cities of refuge came to an end, as it is said “And the Tirshatha said unto them, that they should not eat of the most holy things, till there stood up a priest with ‘urim and with tummim” (Ezra 2:63), like a man who says to his friend: Until Elijah will come, or: Until the dead will live.

When Haggai, Zechariah, and Malachi, the latter prophets, died, the holy spirit (ruaḥ haqodeš) came to an end in Israel, but even so, they made them hear through an echo (bat qol).

It happened that the sages entered into the house of Guria in Jericho and they heard an echo (bat qol) saying: There is a man who is worthy to [receive] the holy spirit (ruaḥ haqodeš), but his generation is unworthy for that, and they set their eyes upon Hillel the elder. And when he died, they said about him: Woe for the humble man, woe for the pious man, the disciple of Ezra.

Another time they were in sitting in Yavne and heard an echo (bat qol) saying: There is a man who is worthy to [receive] the holy spirit (ruaḥ haqodeš), but his generation is unworthy for that. They set their eyes upon Samuel the Little. And when he died, they said about him: Woe for the humble man, woe for the pious man, the disciple of Hillel the Elder. Also he said at the time of his death: Simeon and Ishmael [are destined] to [execution by] sword, and his associates [are destined] to death, and the remainder of the people will be for spoils, and much distress will come after that. And he said it in Aramaic.

Also concerning R. Judah b. Baba they ordained that they should say: Woe for the humble man, woe for the pious man, the disciple of Samuel the Small. But the times were turmoiled.

He who prophesizes on his deathbed, like Samuel the Little, is proven to be “worthy to receive the holy spirit,” just like John Hyrcanus and Simeon the Righteous who “heard” a voice from the Holy of Holies in 13:5–6. The bat qol identifying the worthy sages is thus both a testimony to the continuation of the holy spirit and the manner of its appearance in the post-prophetic times.

The holy spirit no longer appears to the collective (which is deemed “unworthy”) via prophecy, but it is not lost altogether either. Rather, it is “privatized,” appearing only to designated individuals. Thus, halakhot 3–4 in chapter 13 narrate Haggai, Zechariah, and Malachi and the ceasing of prophecy, but also its substitution, forming a chain of transmission of the holy spirit from Ezra to Hillel, “his student,” to Samuel the Little and then to Judah ben Baba; that is, from the beginning of the Second Temple all the way to Yavne. This is not a depiction of sages replacing prophets but, quite to the contrary, of rabbinic figures who are deemed worthy to continue the prophetic legacy.

What we have here is a kind of apocalyptic tradition, an alternative to the chain of transmission of sages in tractate ’Abot. Both chains find their origins at the beginning of the Second Temple period. But while in ’Abot this period is marked by “the men of the great assembly,” the forefathers of the rabbis, here it is associated with the period of the latter prophets, Haggai, Zechariah, and Malachi. In ’Abot the prophets were followed by the sages: from “the men of the great assembly” through the “pairs” of sages from the times of the Temple (see m. ḥag. 2:2) to the rabbis, while here prophecy is replaced (or is rather continued) by a lesser kind of prophecy. Both texts bridge the gap between the world of the Bible and that of the sages though intermediate figures, but the nature of the channels is very different: in ’Abot, Simeon the Righteous is “of the remnants of the great assembly,” thus continuing the world of Torah which this assembly is said to have initiated;Footnote 16 in our Tosefta there are no “men of the great assembly” and Hillel is “the disciple of Ezra,” thus marking a direct continuation with the end of the biblical period.

The chosen figues in our Tosefta are marginal sages, unlike the dominant sages appearing in ’Abot (only Hillel appears in both lists). They are not marked by their Torah skills (contrast the merits ascribed to the sages in m. Soṭah 9:15) but rather by their piety (ḥasid) and humility (‘anav).Footnote 17 They are the recipients of a diluted prophecy, while Torah is not mentioned at all.Footnote 18 Both chains of transmission ultimately reach Yavne, the place of the rabbis, but the function of Yavne cannot be more different: in Mishnah ’Abot words of wisdom are transmitted;Footnote 19 in Tosefta Sotah, the holy spirit.Footnote 20 Our Tosefta elaborates on the priesthood and the Temple but fails to mention the pairs, meaning the sages’ leadership in Second Temple times, which occupies the central place in ’Abot’s chain of transmission. Since the first “pair” is mentioned in the parallel Mishnah (9:9), the absence from the Tosefta is significant. Lastly, Mishnah ’Abot narrates an optimistic story of the evolution of the oral Torah from individual sages (or couples of sages) to a session in the study house of Rabban Yoḥanan b. Zakkai.Footnote 21 Our Tosefta in contrast tells a gloomy saga of the ever-shrinking place of the holy spirit (ruaḥ haqodeš) from the days of the prophets to the rabbis.

The Tosefta’s answer to Ephraim E. Urbach’s famous question, “when did prophecy cease” and become supplanted by the Torah, is thus: never.Footnote 22 It was transformed, faded, and was replaced by lesser means of communication, but it did not cease.Footnote 23 The tradition did not end. The Tosefta takes pains to emphasize this in the subsequent narratives on the recurrent appearance of bat qol in the house of study.Footnote 24

The termination of the holy spirit is equated here with the ceasing of biblical prophecy (“Haggai, Zechariah, and Malachi”), as is also the case in Josephus (C. Ap. 1.41–42) and Seder ‘Olam (ch. 30). I thus believe that Urbach is right in emphasizing, in his aforementioned article, that the ceasing of prophecy is conceived in these sources as an institutional phenomenon, an indication of the end of the biblical period, and is not to be taken as a general metaphysical assertion.Footnote 25 Therefore, in contexts not connected to the canonization of scripture, the narrative regarding contemporaneous prophecy is more varied, and allows for more fluidity.Footnote 26 Our Tosefta, however, is exceptional in going out of its way to explicate the exact manner in which divine interaction continues via alternative channels.Footnote 27

In the parallel units in the Mishnah, prophecy and ‘urim and tummim appear in a completely different context. There, they are part of the loss of judicial institutions, and are thus juxtaposed to the high court (the Sanhedrin):

When the Sanhedrin ceased, singing was abolished at wedding feasts, as it is said “They shall not drink wine with a song” (Isa 24:9).

When the former prophets died, ‘urim and tummim ceased.

When the Temple was destroyed the Šamir and the honeycomb ceased, and faithful men came to an end, as it is said “Help, Lord, for the godly man ceased, for the faithful have vanished from among the sons of men” (Ps 12:2). (m. Soṭah 9:11–12)Footnote 28

The prophets (named here “former prophets” but referring probably to the same prophets as the Tosefta)Footnote 29 appear as part of the annulment of institutions— the Temple, the Sanhedrin, and so forth—whereas in the Tosefta they appear in relation to the holy spirit (absent from the Mishnah altogether!), worship and the presence of the divine presence (Šheḵinah) (14:3). The two compositions also differ in their contextualization of the Temple: the Mishnah connects it to the lost legal institutions, a well-managed world that has passed, while the Tosefta places it as part of the presence of the holy spirit. We will return to these differences below.

Chapter 13 concludes with an extensive section about Simeon the Righteous and the dire consequences of his death (13:6–8), lengthier than any of the accounts of the biblical figures in the previous chapters. Here are the beginning and the ending of this lengthy unit:

As long as Simeon the Righteous was alive the western candle was permanent. When he died, they went and found it extinguished. From then on it was sometimes extinguished and sometimes lighting….

He (Simeon the Righteous) said to them “in this year I will die.” They said to him: “How do you know?” He responded: “In every day of atonement there was an old man dressed in white and covered in white who would go in with me and come out with me. On this year he went in with me but did not come out with me.” After the holiday he became sick and died after seven days. His friends ceased blessing with the name. (t. Soṭah 13:7–8)

The first thing to note is that the idiom used with regard to Simeon is similar to the phrasing about biblical characters “so long as Simeon the Righteous was alive,” in line with “so long as Abraham/Moses/Samuel was alive.” Simeon’s image also concludes the entire section.Footnote 30 The picture of the Temple prospering as long as Simeon the Righteous was there, is related both to the blessing of affluence (“the Bread of Presence” sufficed for all the priests, etc.) characterizing the period between Abraham and Moses, and to the divine presence and prophecy (the “old man dressed in white” that is an angel, who entered with him every year into the Holy of Holies) of the period between Elijah and the latter prophets.Footnote 31 This unit thus summarizes the different types of blessings which the biblical righteous brought to the world.

What is the meaning of this odd configuration? A beginning of an answer may come from a surprisingly similar structure which appears at the end of the book of Ben Sira. There, too, the praise of the biblical forefathers, from Enoch to Nehemiah (chs. 44–49),Footnote 32 ends with the lengthy eulogy of Simeon the High Priest (ch. 50). Most scholars believe that “Simeon the Righteous” of our Tosefta is the same figure as “Simeon son of Yoḥanan the Priest” in Ben Sira, and that both are to be identified with Simeon II mentioned by Josephus as being active at the beginning of the second century BCE.Footnote 33 But it is the literary resemblance that interests us here. The thematic and structural similarities between the two texts—praise of the biblical forefathers which leads to a eulogy of Simeon, who is both righteous and a high priest—are simply too extensive and meticulous to be accidental.

In both instances the eulogy of Simeon shows strong ties to the praise of the forefathers preceding it, of which it is the telos.Footnote 34 In both, there is a special emphasis in the portraits of the biblical figures on the Temple and the priesthood,Footnote 35 as well as on prophets and prophecy.Footnote 36 Lastly, both Ben Sira and the Tosefta share a unique emphasis on the role of the prophet Elijah.Footnote 37

The similarity becomes even more apparent with regard to Simeon’s own praise. Like Ben Sira, the Tosefta narrates Simeon exclusively in terms of his priestly roles,Footnote 38 in contrast to other rabbinic sources, which present him as a proto-sage.Footnote 39 While m. ’Abot 1:2 depicts “Simeon the Righteous” as a teacher of Torah, “one of the last of the men of the great assembly,” our Tosefta presents him as an exemplary master of the Temple ritual. Furthermore, in both Ben Sira and the Tosefta, Simeon is connected specifically to divine fire and light in the Temple (“the western candle was permanent,” and so forth).Footnote 40

Scholars suggested that Ben Sira’s praise is part of a larger liturgical tradition, known as the ‘avodah poetry.Footnote 41 But the similarities, both thematic and structural, between Ben Sira and the Tosefta are too meticulous and specific to be ascribed to a shared priestly liturgical tradition. Specifically, the usage of the figure of Simeon does not appear in other ‘avodah poems. The simplest explanation of this phenomenon is therefore a direct literary influence of Sirach upon the Tosefta (or its source). To the best of my knowledge, previous scholars only identified local citations of—and allusions to—specific verses from Sirach,Footnote 42 but not an imitation and adaption of a whole unit.Footnote 43

Alternative Sequences: the Tosefta versus the Mishnah

So far we have discussed chapters 10–13 and argued that although they are made of various sources they form a coherent unit. One can further argue that this unit was redacted before it was planted in its present place in Tosefta Soṭah. It is formed independently of the parallel Mishnah, in which neither the biblical heroes and Simeon the Righteous nor the holy spirit and bat qol are mentioned. Only one clear reference to the Mishnah exists in these chapters—t. Soṭah 13:9–10 which interprets the “awakeners and knockers” mentioned in m. Soṭah 9:10—but it is placed at the very end of the unit, after the eulogy of Simeon the Righteous, and so is probably an addition.Footnote 44 In other words, the sequence in the Tosefta, which begins with Methuselah and ends with Simeon the Righteous, shows no literary dependency on the Mishnah, and so can be read as an independent, redacted literary unit.Footnote 45

But can we go further and suggest that different sources were combined, edited, and organized in the Tosefta according to some intrinsic logic or sequence while at the same time reacting to and commenting on the Mishnah? Can we assume, in other words, that our Tosefta preserves both vertical and horizontal orders side by side? To examine this, we shall survey the last two chapters of Tosefta Soṭah and their relationship to the previous chapters as well as to the parallel Mishnah.

Chapters 10–13 are followed by two additional units: Chapter 14 which laments the depraved situation of the present with the refrain “When x [x being a negative phenomenon] multiplied” (mišerabu), and Chapter 15 which discusses the grave consequences of the destruction of the Temple. While these chapters too are made of several independent units, they also reveal clear affinities with the preceding chapters —as can be easily seen from the repeated format, which already appear in chapter 13: “when [or: since the time miše …] x happened, y happened”Footnote 46—thus espousing the strong hand of a redactor. But these last two chapters, unlike chapters 10–13, reveal also a literary dependency on the Mishnah in several places,Footnote 47 thus compelling us to read them horizontally as well as vertically.

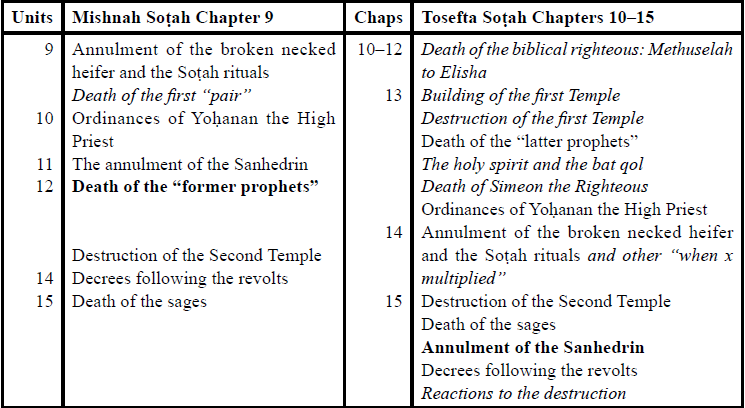

In order to evaluate the relationship between these two vectors, let us compare the Mishnah and the Tosefta’s different sequences along the whole unit: m. Soṭah 9:9–16 and Tosefta chapters 10–15, respectively (stages that have no parallel are italicized; bold text marks events that appear out of their chronological order).Footnote 48

The Mishnah opens with the annulment of the broken necked heifer,Footnote 49 and the cessation of the Soṭah ritual. A list of other cessations then follows: “when x died/ ceased … y ceased.” These cessations are of three types: direct consequences (“When the former prophets died, the ’urim and tummim ceased,” “When Rabban Yoḥanan ben Zakkai died, the splendor of wisdom ceased”); general calamities (“from the day the Temple was destroyed, there is no day without a curse”); and court decrees mandating mourning following the three failed revolts (“During the war … they decreed against …”). The material, collected from various sources,Footnote 50 is redacted chronologically: beginning with the first “pair” and ending (originally) with the sages at the time of the destruction of the Temple.Footnote 51

In the parallel Tosefta, different kinds of material were also introduced to create a uniform framework of decline. Note that chapters 10–12, in and of themselves, do not depict deterioration, but circular processes: “as long as Abraham was alive/ existed there was plenty, when Abraham died there was famine in the land. When Isaac came there was plenty [read: again].” Chapter 14 also does not describe a linear decline but a series of low points—“When x multiplied, y ceased”—with no hierarchy between them. But the introduction of these portions into the broader sequence, beginning with the biblical forefathers and ending with the loss of the Temple and its fatal effects, creates the overall impression of a chronological decline from Methuselah to Yavne. This Hesiodic-like narrative—a perpetual decline from the golden age to the age of iron—is unparalleled in Tannaitic literature.Footnote 52

And just as the Tosefta’s historical narrative is exceptional—a continuous deterioration of divine revelation—so also is its ultimate solution. The Torah has no place in curing this situation; in fact, it is part of the decline.Footnote 53 The antidote appears in the form of personal piety (like that of Simeon the Righteous) and the continuous existence of the holy spirit. It is in this context that the Tosefta displays an alternative to the normative rabbinic chain of the holders of Torah, a tradition of those who are worthy to receive the holy spirit.

The annulment of the broken necked heifer and of the Soṭah rituals opens chapter 14 of the Tosefta—nestled between the regulations of John Hyrcanus at the end of chapter 13 and the destruction of the Temple at the onset of chapter 15—as part of the “when x multiplied” series that deals with the end of the Second Temple period. This seems to be the original context of the narrative of the annulment of these rituals, whereas the Mishnah tore them from this list (and from their chronological order at the end of the Second Temple period) and placed them as a heading for the whole narrative of decline.Footnote 54 This replacement radically transformed the meaning of the annulment of the broken necked heifer and of the Soṭah rituals, altering it from criticism into an elegy.

The deaths of the “latter prophets” (as in MS Erfurt) are properly situated in the Tosefta (13:3) after the destruction of the first Temple, whereas in the Mishnah the death of the “former prophets” are adjacent to the destruction of the Second Temple. Whether or not these “former prophets” are but another name for the “latter prophets,” as I believe is the case, they are certainly not related to the Roman period. That means that the Mishnah’s logic here was thematic rather than chronological; it placed the cessation of prophecy as part of the annulment of the judicial authorities.

Conversely, the Tosefta delays the annulment of the Sanhedrin (15:6) to after the destruction of the Second Temple (15:1–2), together with other responses to the present distress (ṣarah).Footnote 55 I suspect that it is not a mere chance that the Tosefta “fails” to put the annulment of the Sanhedrin in its historical place, while the Mishnah makes a similar “mistake” with regard to the prophets (see the bold lines in the table above). The Tosefta does not care to put the Sanhedrin in its historical place, as the history it tells is that of the deterioration of prophecy. The Mishnah, on the other hand, did not place the death of the prophets properly, as its history is that of judicial institutions.

The deaths of the sages (all operating still in the times of Temple)Footnote 56 conclude the entire section in the Mishnah, whereas the Tosefta places these deaths in their chronological order between the destruction and the wars, as most of the sages mentioned belong to the Yavne generation. The Tosefta then ends with the calamities which multiplied “from the day on which Temple was destroyed.”

The Mishnah and Tosefta units in their entireties are thus two very different accounts, each coherent in and of itself, with a few cases of direct literary dependency of the Tosefta on the Mishnah.Footnote 57 Let us trace these two alternative narratives: Following the narration of the ceasing of the broken necked heifer and the Soṭah rituals, the Mishnah presents a series of annulled institutions, which together amount to a narrative of an orderly world—with Sanhedrin, prophets, Temple and sages—that was lost. This is a saga of a gradual process of deterioration, from the first “pair” in the Hasmonean period up to the destruction of the Second Temple and the death of the sages. The Tosefta, on the other hand, presents a longue durée historiographical account of a perpetual decline, from the beginning of humanity. And whereas the Mishnah’s organizing principles are judicial authorities—formed in light of the cessation of the two rituals destined to overcome judicial doubt—the Tosefta concentrates on the holy spirit.Footnote 58

These differences account for the various changes between the parallel portions in the two compositions: The Mishnah’s narrative begins with the “pairs,” whereas the Tosefta, which begins with the creation of the world, opens its detailed description from the destruction of the first Temple. The Tosefta skips the “pairs” altogether, probably because they play no role in the context of the holy spirit. In the Mishnah the cessation of prophecy and of the ’urim and tummim appear alongside that of the Sanhedrin, as the organizing principle is the termination of judicial authorities. The holy spirit (ruaḥ haqodeš), which is not part of this narrative, is absent altogether. Conversely, the Tosefta place the cessation of the ’urim and tummim in its chronological order at the end of the first Temple. On the other hand, the cessation of the Sanhedrin is not found in the Tosefta in its place, but rather as part of the courts’ decrees following the troubles accompanying the revolts, as its linear decline narrative focuses on the holy spirit.

To recapitulate this excess of details: the most important judicial institutions, the “pairs” and the Sanhedrin are either misplaced in—or altogether missing from— the Tosefta, which concentrates on the history of revelation. At the same time, the Mishnah, which does not mention ruaḥ haqodeš and bat qol at all, reorganizes the major institutions related in the Tosefta to the holy spirit, the prophets, and ’urim and tummim, so as to tie them to its central theme, the loss of judicial institutions, the prime example of which is the Soṭah ritual which opens the whole passage.

Tosefta Soṭah 10–15 and Apocalypticism

These two narratives are also very different in their affiliation with the ethos found in rabbinic literature in general. While the Mishnah’s judicial narrative, into which the sages, the Sanhedrin, and the Temple fit, characterizes the Tannaitic world view,Footnote 59 the Tosefta’s storyline is highly exceptional. It displays several clear apocalyptic traits: continual mediated revelation (bat qol; an old man dressed in white), explicitly distinguished from classical prophecy (“the holy spirit ceased”), revealing hidden knowledge (“there is a man among you …”), with a sense of crisis (destructions, persecution, “When x multiplied,” “when y died,” decrees), leading to explicit eschatological hope (“rejoicing with her [Jerusalem]”).

Two of these themes are especially characteristic of apocalyptic texts: 1) The emphasis on a continual revelation throughout history, leading to and culminating in the author’s own time and setting (in our case: the study house in Yavne). Present revelation, however, is diluted and mediated (bat qol).Footnote 60 2) Eschatology appears as a solution to the dire conditions of the present.Footnote 61 While explicit eschatological statements appear only at the very end of the tractate (“whoever mourns for Jerusalem merits rejoicing with her”),Footnote 62 the whole unit points toward this direction, as it presents an ever-worsening situation, peaking in the destruction of the Temple, with no outlet other than eschatology.Footnote 63 Indeed, a later interpolator felt the need for a similar outlet in the Mishnah, thus adding an eschatological unit there, too.Footnote 64

Those who are zealous about precise definitions will notice that I am careful to use the adjective “apocalyptic” rather than the noun “apocalypse.” The former term is used by scholars to mark a set of ideas and motifs characterizing apocalypses but not confined to apocalyptic works per se (like Daniel or Revelation).Footnote 65 Rather it can be found in compositions, or parts of compositions, from various genres (such as the Damascus Document or Paul).Footnote 66

Our Tosefta is probably not an apocalypse according to accepted scholarly definitions, not only due to formal, generic differences (the mediated revelation is not responsible for the narrative), but also because apocalyptic ideas are combined here with themes taken from wisdom and priestly contexts. Ben Sira famously combines priestly and wisdom-centered world views,Footnote 67 blended with a few “Enochic” allusions.Footnote 68 Our Tosefta frames these conventional themesFootnote 69 in a strong apocalyptic context. One can point to precedents for all these combinations in pre-rabbinic texts.Footnote 70 But this specific amalgamation—which blends in also the rabbis, thus creating a chain of transmission of sages and priests who are worthy of possessing the holy spirit, in a context of destruction and crisis—is unique.Footnote 71

And so even if it might be a bit of a stretch to designate our text “a rabbinic apocalypse,” one must admit that such a narrative of revelation in the wake of the destruction is more reminiscent of the apocalypses of 4 Ezra and 2 Baruch than of Tannaitic compositions.Footnote 72

This is the picture painted from a successive reading of the Tosefta, and I believe that it is sufficiently coherent—that is, the same motifs are repeated in different sections —to point to a guiding redactor’s hand, over and above the discrete units. The Tosefta’s various materials, both the independent ones and those correlating with the Mishnah’s parallel text, are collected and designed according to a clear Tendenz, different from, but no less coherent than, that of the Mishnah. Thus, the fact that the Tosefta’s material was adapted to complement the Mishnah, and that it has a few direct exegetical notes on the Mishnah’s statement, does not refute a continuous reading of this unit on its own, independent terms.

We have thus made two arguments regarding the sources of our Tosefta: one concerns the structural dependence of our Tosefta on Ben Sira’s “praise of the fathers,” and the other concerns apocalyptic themes found in our Tosefta. These, however, relate to two congruent but not identical units. The first argument relates to chapters 10–13, which were probably redacted before they were placed parallel to the Mishnah. The second argument relates to the composite unit of chapters 10–15. This unit as a whole was redacted in a manner that emphasizes apocalyptic themes, both through the appearance of the bat qol material in chapter 13, and through its juxtaposition with chapters 14–15, which deal with the destruction of the Temple and the dire conditions of the present.

And yet this distinction should not be overemphasized. As seen above, chapters 10–13 also incorporate various sources and adapt existing material, and the apocalyptic material is intertwined in chapter 13 with the praise of the fathers’ unit (both in the narration of the bat qol tradition and in the prophecies of Simeon the Righteous and Yoḥanan the High Priest). And so we are dealing here with a multi-layered process of formation. We suggested above some traces of the older layers, but only with regard to the redacted unit can a clear, well-crafted narrative be observed. In its final, redacted form, our narrative combines wisdom, priestly, and apocalyptic themes in a manner that is unprecedented in rabbinic literature.

Let us end with marking two wider implications of our reading. One relates to the possibility of reconstructing the social history behind our redacted text, and the other to the composition of the Tosefta and the nature of the Tosefta as a composition.

First, the Tosefta adopts Ben Sira’s structure, and inserts into it an apocalyptic narrative: a mediated prophecy which professes eschatology in a time of crisis. This framework is foreign not only to Ben Sira but to the rabbis as well. As Moshe Simon-Shoshan notes, in all Tannaitic literature there is no other narrative of a bat qol appearing to sages.Footnote 73 What kind of social history might stand behind this combination? What kind of rabbinic group could be responsible for the formation of this unit in the Tosefta? Who might have fused priestly, wisdom, and apocalyptic elements together?

A priestly circle would be the usual suspect, for in these circles we usually find similar combinations of wisdom, Temple traditions, and apocalypticism.Footnote 74 Priestly material was indeed identified in these chapters.Footnote 75 But without any positive evidence, and notwithstanding the notorious difficulties to extract specific historical settings from rabbinic texts, I will have to leave these questions open for future research.Footnote 76

I will note, however, that this is not a solitary case. In another article, I identify apocalyptic themes in the scapegoat ritual in Mishnah Yoma chapter 6. I argue there that the Mishnah combines two types of rituals: a priestly one, which ends, as in Lev 16, with the expulsion of the goat to the desert, and an “Enochic” one, in which the goat/Azazel is thrown from a rock.Footnote 77 One can only hope that tracing additional cases like these will lead to further hints as to the possible social realm(s) behind them.

But even without pointing to the exact source of our unit, it can be used to problematize some conventional stories we tell. The unique nature of our unit should give pause to attempts to use it as a source for reconstructing “rabbinic” theology tout court.Footnote 78 At the same time, it also complicates the traditional narrative about the decline of apocalyptic thought after the destruction of the Second Temple (with 4 Ezra as the last exemplar) to be revived only in the Islamic period.Footnote 79

Second, our unit manifests two types of relationships between the Mishnah and the Tosefta. In chapters 10–13 we encountered an independent unit, with a reference to the Mishnah appended to it, while in chapters 14–15 the references to the parallel Mishnah are an integral part of the original making of the text. These chapters, however, also form a coherent unit, thus making their editing double in nature, demanding that they be read both in relation to the Mishnah and independently, vertically as well as horizontally.

The question of how the Tosefta relates to the Mishnah has troubled interpreters ever since the epistle of Rav Sherira Gaon.Footnote 80 Modern scholarship of the Tosefta, too, when not purely philological in nature, focuses mainly on its correlation to—and dependence upon—the Mishnah.Footnote 81 Attempts to read the Tosefta as a composition are always connected to the question of its dependence on the Mishnah. And yet the possibility of reading segments of the Tosefta in sequence should be evaluated independently of the question of its relation to the Mishnah. For, in whatever manner we imagine the Tosefta’s connections to the Mishnah, there is no doubt that it underwent some form of redaction, as can be easily shown by the literary constructs, repetitions and set structures found in it (some examples were discussed above). Thus, we must ask, regardless of the much-debated issue of Tosefta-Mishnah relations, whether the Tosefta can also be read consecutively? Footnote 82 After all, such a phenomenon of a double text, which refers to another text while at the same time preserving its own coherence,Footnote 83 is well known in literature, old and new.Footnote 84

In a previous article I have argued for a similar double reading with regard to the end of tractate Berakhot. Chapter 6 in the Tosefta comments on the parallel Mishnah (ch. 9) while at the same time preserving an independent agenda.Footnote 85 These examples call for further research into this phenomenon, which will allow a reevaluation of the strategy of the double, vertical as well as horizontal, reading of the Tosefta.