1. Introduction

Heritage speakers are individuals who were exposed to a minority (home) language from birth, attain at least receptive competence in that language but grow up to be socially and educationally dominant in the majority language of the wider society (Montrul, Reference Montrul2015; Polinsky, Reference Polinsky2018). This distinction reflects differences in input quantity or amount of exposure as well as input quality or contextual variability (Unsworth, Reference Unsworth, Nicoladis and Montanari2016). Most psycholinguistic studies of heritage languages (HLs) focus on immigrant contexts where geographical barriers often hinder language maintenance (Argyri & Sorace, Reference Argyri and Sorace2007). Much less attention has been given to HLs in non-immigrant contexts, with a few exceptions (Backus, Reference Backus, Bhatia and Ritchie2006). We use the term in-situ/border-shift heritage community for historical minorities who remain on their ancestral territory but now lie within another nation-state after geopolitical realignment, with variable community and institutional support (cf. Ridanpää, Reference Ridanpää, Gartner and Ortag2021; Willemyns, Reference Willemyns2002). Such speakers retain local intergenerational ties while functioning as a minority in their homeland (cf. Fishman, Reference Fishman1991). On a sociolinguistic continuum, mainland monolinguals sit at one end (maximal support), immigrant-diaspora HLs sit at the other (minimal support) and in-situ communities occupy an intermediate, geographically close but variably supported position.

Input in in-situ communities shares features with immigrant settings (parental use, community networks) but also differs in key ways. Where integration and inclusive policies prevail, hybrid identities can support more balanced bilingualism (Blackledge & Pavlenko, Reference Blackledge and Pavlenko2004; Martinet & Weinreich, Reference Martinet and Weinreich1979). Dense institutional support in the form of schools, churches, associations, etc., bolsters HL transmission beyond the family (De Houwer, Reference De Houwer2007), whereas immigrant contexts often face isolation and assimilation pressures that accelerate shift (Aravossitas, Reference Aravossitas and Trifonas2019; Shin, Reference Shin2023). Overall, the literature converges that input amount and quality, shaped by institutional density, matters more than geographical distance for HL maintenance.

At present, there is not much clarity as to whether and to what extent the grammatical competences of speakers of in-situ HLs may be affected due to the border shift and the role of institutional support in this process (Brehmer, Reference Brehmer, Polinsky and Montrul2021). Border-shift populations let us test whether institutional density rather than geographical proximity drives grammatical competence and patterns of use of HL. They also put to the test the binary ‘weaker’/‘stronger’ language distinction commonly assumed in immigrant HL studies (Polinsky, Reference Polinsky2018; Putnam & Sanchez, Reference Putnam and Sánchez2013: 478; Rothman, Reference Rothman2009) and provide a unique lens to determine, among other things, whether HLs inevitably weaken under a new dominant language. Our findings indicate that proximity to the homeland is neither necessary nor sufficient for robust HL competence. Instead, the quality and density of local institutional support and the sustained availability of HL input across the lifespan are the principal determinants of comprehension outcomes. Cohesive in-situ communities with consistent homeland language access may approach balanced bilingualism, whereas weaker ties to the homeland language can lead to notable performance differences. The present study focuses on sentence comprehension to explore these aspects.

2. Slovene speakers in the Friuli Venezia Giulia region: A brief overview

This study examines heritage Slovene, a Slavic language underrepresented in HL research, targeting Slovene speakers in the Italian provinces of Udine, Gorizia and Trieste near the Italian-Slovenian border. These populations, though officially recognized as a minority, exhibit significant differences in Slovene use and representation due to historical, geographical and sociopolitical factors (see Supplementary Appendix A for a map and a historical note). The Gorizia and Trieste heritage communities benefit from stronger institutional and governmental support, fostering active use of Standard Slovene. Slovene-language schools up to the high school level offer instruction in Slovene across all subjects, including history, literature and cultural studies. They follow the Italian national curriculum and include the Italian language, history and culture but also incorporate additional content that focuses on Slovenian history, literature and cultural heritage. The Gorizia and Trieste provinces together feature over 70 preschools, primary, junior and senior secondary schools with Slovene as the language of education (Mezgec, Reference Mezgec2024; NIE, 2024; Vidau & Bogatec, Reference Vidau and Bogatec2020). This educational framework ensures that students receive comprehensive instruction in both the Italian and Slovene languages and cultures. In addition, a number of actively functioning Slovenian cultural organizations and public services sustain bilingualism as a vibrant cultural identity.Footnote 1 This dense institutional ecology predicts strong comprehension in Slovene despite the societal dominance of Italian.

In contrast, the Natisone Valley community in the Udine region faces limited institutional support, resulting in lower Slovene literacy and presence of the Slovene language in public domain. In the Natisone valley, language transmission depends largely on family and community networks. A bilingual Slovene-Italian school established in 1984 in San Pietro-al-Natisone/Špeter is the only institution offering a primary school education in both Italian and Slovene languages in an approximately equal proportion: for further education, only Italian-language schools are available. Given the weaker connections to Slovenia and limited language visibility in public life, many community members identify with both Italian and Slovenian cultures. Another consequence of the relative linguistic isolation of the Natisone speakers is the predominance of dialectal forms influenced by Italian, at the phonological, morphological and morphosyntactic levels (cf. Kumar, Reference Kumar2022). These dialects, while distinct from Standard Slovene, share similarities with those in Slovenia’s Kobarid region (Section 5.1). Overall, this disparity significantly impacts exposure to Slovene in the above communities, shaping distinct linguistic profiles across these regions, despite comparable geographical proximity.

3. Word order, relative clauses and cataphora: Selectively vulnerable domains

We compared three syntactic domains: (i) word order with case morphology, (ii) relative clauses (RCs) and (iii) cataphora, in Gorizia/Trieste and Natisone HL communities, which differ in Slovene exposure due to unequal institutional support. We selected these phenomena according to two recurring complementary motivations in the HL literature. First, sentences manipulating word order and overt case morphology tap the area where many heritage grammars of richly inflecting languages have proved most fragile: when the dominant language relies primarily on position, heritage speakers often revert to a ‘first-NP-as-subject’ heuristic and neglect case endings (Section 3.1). Second, RCs as well as referential dependencies impose high processing demands; both are late-acquired even in monolingual development and can therefore serve as good probes of whether sustained input can mitigate processing limitations (Sections 3.2 and 3.3). If the Gorizia/Trieste community truly benefits from denser input, we expect them to pattern with monolinguals in both grammatical as processing dimensions, while the Natisone group should show the classic heritage signature, namely reduced case sensitivity and greater difficulty with the resource-intensive structures.

3.1. Word order and case morphology

Slovene is a relatively free constituent order SVO language that marks grammatical categories such as subject and object with overt morphological case markers. Slovene speakers typically rely on two strategies for determining grammatical functions of the noun phrases (NPs): word order (first NP as subject, second as object) and morphological case markers (nominative for subject, accusative for object). To structure background and foreground information, Slovene allows displacement of an object in front of the sentence forming an OVS structure. In such cases, grammatical categories remain clear due to case markers on NPs. Comprehending the marked OVS order relies on morphological anchoring to indicate grammatical functions, making it more resource-intensive to process than the unmarked SVO order (Slioussar, Reference Slioussar2011). Slovene examples of both types used in our study are shown in (1):

Evidence consistently shows that unbalanced minority speakers often lose sensitivity to case morphology in marked word orders (Leisiö, Reference Leisiö2006; Polinsky, Reference Polinsky2006; Reference Polinsky2011; among others). In comprehension, these speakers tend to default to interpreting the first NP as the subject, irrespective of case marking, and struggle with marked orders where the object was fronted, though this phenomenon may be task dependent, as some studies reported no such differences in grammatical judgments (cf. Leal Méndez et al., Reference Leal Méndez, Rothman and Slabakova2015). Even more extensive evidence is available from production where unbalanced speakers show a preference for unmarked word orders (Isurin & Ivanova-Sullivan, Reference Isurin and Ivanova-Sullivan2008; Laleko, Reference Laleko2022; Song et al., Reference Song, O’Grady and Cho1997; among others; but see Laleko & Dubinina, Reference Laleko, Dubinina and Beliaeva2018). For instance, Laleko (Reference Laleko2022) tested adult English-Russian heritage speakers (n = 27) and L2 learners (n = 15) against monolingual controls (n = 15) using contextualized acceptability judgments on subject inversion across verb classes (unaccusative, unergative, and transitive) and information-structure contexts (broad vs. narrow subject focus). Bilinguals under-accepted inverted orders overall; advanced heritage speakers showed target-like sensitivity to unaccusativity and focus (e.g., more OVS under narrow-subject focus), whereas lower-proficiency heritage speakers and L2 learners showed no clear unaccusativity/focus effects. These results indicate reduced tolerance for non-canonical orders and attenuated cue integration, consistent with a shift toward canonical SVO when input is limited. Similarly, Hoot (Reference Hoot2019) and Hoot & Leal (Reference Hoot and Leal2023) found no significant differences in processing non-canonical word orders among Hungarian and Spanish heritage speakers. In short, research on word order in HLs demonstrates that while speakers are aware of both unmarked and marked orders, they often struggle to use marked word order variations within discourse contexts.

Italian, the societally dominant language of our tested populations, provides little overt NP case and defaults to SVO. OVS is possible but pragmatically constrained. Thus, Italian input reinforces positional heuristics and does not supply robust case cues, a profile that reinforces greater vulnerability on Slovene OVS for heritage listeners with limited Slovene exposure.

3.2. Relative clauses

Studies on the syntactic competence of heritage speakers suggest that core syntactic knowledge remains relatively stable (Kim & Goodall, Reference Kim and Goodall2016). However, a notable trend is the simplification of syntactic complexity, such as a preference for local over long-distance dependencies. RCs exemplify this tendency. O’Grady et al. (Reference O’Grady, Lee and Choo2001) tested heritage (n = 16) and non-heritage learners (n = 45) on Korean RCs with a sentence–picture matching task. They found no significant group difference between heritage and non-heritage learners, but all groups showed a clear subject > object RC advantage with frequent reversal errors on object RCs, mirroring monolingual patterns. Similar findings were reported for American English-Mandarin (Jia & Paradis, Reference Jia and Paradis2020), American English-Turkish (Coşkun Kunduz & Montrul, Reference Coşkun Kunduz and Montrul2024) and German-Greek (Katsika et al., Reference Katsika, Lialiou and Allen2024) heritage children. Polinsky (Reference Polinsky2011) observed that Russian heritage children performed comparably to monolinguals on both types of RCs, while adult heritage speakers struggled with object RCs, performing randomly. Similarly, Italian uses head-initial RCs and shows processing asymmetries tied to maintenance/integration in RCs. Nothing in Italian removes the storage/integration cost that drives the object RC disadvantage cross-linguistically. Thus, transfer from Italian does not predict elimination of the object RC difficulty in Slovene; if anything, it leaves the asymmetry in place.

Structural simplifications in heritage speakers are often attributed to processing constraints. While subject and object RCs are syntactically comparable, object RCs impose greater processing demands on verbal working memory due to additional storage and integration requirements: the moving DP, as in the senator who John met, must be held active across the clause-internal subject, creating an additional rank of embedding in the dependency stack, compared to subject RCs such as the senator who met John (Ford, Reference Ford1983; Gordon et al., Reference Gordon, Hendrick and Johnson2001; Grodner & Gibson, Reference Grodner and Gibson2005; Levy et al., Reference Levy, Fedorenko and Gibson2013, among others). Polinsky (Reference Polinsky2018: 67) identifies a set of potential processing limitations in heritage speakers, including (i) insufficient access to world knowledge, (ii) inefficient information coordination, (iii) suboptimal resource allocation and (iv) limited processing resources such as short-term memory, attention or motivation (cf. Lohndal, Reference Lohndal, Montrul and Polinsky2021; Polinsky & Scontras, Reference Polinsky and Scontras2020). Indeed, the latter is the mechanism we probe with RCs as well as cataphora (as discussed later).

We used center-embedded rather than right-branching RCs because they have been shown cross-linguistically to magnify group differences in working memory-based tasks (Katsika et al., Reference Katsika, Lialiou and Allen2024). Because center-embedded RCs are maximally taxing, they provide the strongest chance of revealing any processing penalty that reduced input may induce in a heritage parser. Representative examples of subject and object RCs used in this study are shown in (2).

3.3. Referential dependencies: Cataphora

Cataphora refers to the type of referential dependencies when the referent of the pronoun linearly follows it (e.g., when he entered, the king sat on the throne). Processing cataphora involves activating a forward-looking search for an antecedent at the pronoun cue, taxing working memory in ways similar to filler-gap dependencies (Cowart & Cairns, Reference Cowart and Cairns1987; Van Gompel & Liversedge, Reference Van Gompel and Liversedge2003). In pro-drop languages like Italian or Slovene, the pronoun is silent, so the dependency must be established in the absence of an overt cue: this has been shown to be the case for Italian (Carminati, Reference Carminati2002; Fedele & Kaiser, Reference Fedele and Kaiser2014) as well as Slovene (Pavlič & Stepanov, Reference Pavlič and Stepanov2023). Previous studies explored strategies for establishing coreference with null pronominals in anaphoric dependencies in the bilingual context (Di Domenico et al., Reference Di Domenico, Baroncini and Capotorti2020; Serratrice, Reference Serratrice2007; Sorace & Filiaci, Reference Sorace and Filiaci2006; Tsimpli et al., Reference Tsimpli, Sorace, Heycock and Filiaci2004; among others). At the same time, research on processing cataphora in the bilingual context has been somewhat scarce. Serratrice (Reference Serratrice2007) tested three groups: English-Italian bilingual children, age-matched Italian monolingual children and Italian monolingual adults (n = 13 each) in a picture verification task. She found robust subject-antecedent preferences for null pronouns across child groups, with adults showing stronger subject choices in cataphora, with overt pronouns, both child groups, especially the bilinguals, over-accepted subject coreference relative to adults. These patterns were attributed to processing/strategy coordination and cross-linguistic influence rather than wholesale representational loss. As far as we are aware, no studies have compared how adult heritage speakers process cataphora in the pro-drop language compared to monolinguals.

For this study, we selected transitive clauses in the context of null pro cataphora in unmarked SVO (Cat.SVO) and marked OVS (Cat.OVS) word orders. Cat.OVS imposes greater processing demands than Cat.SVO due to the need to track the grammatical function of the referent to resolve the dependency (Section 3.1). Representative examples are shown in (3).

4. The present study

We asked whether border-shift heritage speakers exhibit similar comprehension vulnerabilities to those previously reported in immigrant-heritage populations (greater reliance on positional heuristics and higher costs for maintaining/reanalyzing dependencies) across specific syntactic domains, namely word order, RCs and cataphora, and if so, whether this sensitivity varies with the amount of cumulative Slovene input they receive. We hypothesized that the limited input and greater metropolitan isolation of Natisone Slovene speakers would more significantly impact their performance in case morphology, a vulnerable area of Slovene grammar, in comparison with monolingual controls, while the exposure-rich Gorizia/Trieste group would perform comparably to monolinguals. Additionally, the more limited input available to Natisone speakers was hypothesized to increase processing demands, particularly in long-distance dependencies in RCs and cataphora. Our specific predictions (P) were as follows:

P1. Because both heritage groups operate under dominant Italian, a language that uses SVO order and relies less on case endings, we predict an agent-first parsing bias when case cues conflict with position. Specifically, in OVS clauses, we expect some heritage listeners, especially in the Natisone group, to mis-assign the preverbal object as the grammatical subject/agent. In SVO clauses, no such conflict arises, so, all else equal, performance should approach ceiling in both groups.

P2. In line with previous work (Section 3.2), we predicted a SRC > ORC advantage in both heritage groups, in terms of higher accuracy and faster responses. Viewing this advantage as processing-based, we expected the extra cost of object RCs to be larger in Natisone, where Slovene exposure is lower, than in the input-rich Gorizia/Trieste group. Accordingly, Natisone should depart from the monolingual pattern, whereas Gorizia/Trieste should approximate it.

P3. Resolving cataphora involves establishing a dependency by linking a preverbal null subject to a later antecedent. We anticipate greater difficulty implementing this process in both heritage groups compared to monolinguals, especially in non-canonical word order in the main clause (Cat.OVS), with the difficulty again amplified in the Natisone group with more Italian-dominant exposure.Footnote 3

Because the two heritage communities are only about 30 km apart along the same border corridor, any performance gap can be attributed to the difference in exposure as modulated by institutional support rather than to physical distance from the homeland. For the present purposes, institutional density is reflected in schooling/organizations operating in Slovene (Section 2), while sustained input is operationalized via the cumulative exposure index and related measures (Section 5.3).

5. Method

We evaluated the predictions with the auditory sentence–picture verification task from the standardized JERA battery, an instrument that probes syntactic and processing aspects of sentence comprehension in Slovene (Stepanov et al., Reference Stepanov, Pavlič, Pušenjak Dornik and Stateva2024).

5.1. Materials

The materials included a set of sentence–picture stimulus blocks covering the six target sentence types described in Section 3, plus four additional types that served as fillers in the present study. Each trial involves a visual stimulus featuring four candidate images arranged in a 2 × 2 grid in a pseudo-random order, paired with an audio playback of the target sentence. All target sentences featured transitive verbs with animate subjects and objects (people or animals). The predicates were selected for reversibility of subject and object roles. Sentence–picture pairings were constructed so that only one of the four displayed images corresponded uniquely to the target sentence. The remaining three images served as distractors. The distractor images were constructed so that they each depicted a variation on the event of the target image and its respective actors, whereby either one of the actors (expressed by subject and/or object), both actors or the nature of the event(s) themselves was different. Examples and specific event schemes for each sentence type can be found in Supplementary Appendix D. Sentences were recorded by a native female speaker of Standard Slovene in studio-quality conditions, and pictures were color drawings. Each sentence type had 10 tokens (60 targets total) plus 40 fillers.

A natural approach would be to test both the Gorizia/Trieste and Natisone heritage groups under a single experimental setup. However, the Natisone group’s more limited access to Slovene leads to a lexical difference, with greater use of dialectal forms rather than Standard Slovene. In a pilot study using the standard JERA materials, Natisone speakers struggled with certain Standard Slovene lexical items in our target sentences, despite their high familiarity and corpus frequency (cf. Stepanov et al., Reference Stepanov, Pavlič, Pušenjak Dornik and Stateva2024). This lexical disparity could disadvantage the Natisone speakers in the original JERA materials, creating a confound for our study focused on sentence comprehension. To address this, we utilized Slovenia’s diglossic situation, where speakers use both the ‘high’ Standard Slovene in formal contexts and ‘low’ regional dialects, classified into at least seven major dialect groups (Podobnikar et al., Reference Podobnikar, Škofic, Horvat, Gartner and Ortag2009). We compared the Natisone speakers’ performance with that of Slovene speakers from the Kobarid region, which shares a similar lexical repertoire due to geographical proximity (cf. Kumar, Reference Kumar2022). This comparison allows for a more ecologically valid analysis of sentence comprehension patterns while maintaining the critical distinction in exposure: Kobarid speakers are exposed to both Standard Slovene and their regional variety, while Natisone speakers are not (Section 2).

For the Kobarid/Natisone manipulation, the lexically adjusted test sentences were pre-recorded by a native speaker of Standard Slovene who also spoke the Kobarid variety, using the same recording parameters. All other materials were identical to those used in the original test for the Gorizia/Trieste population.

The experiment was programmed on a stand-alone, offline instance of the Ibex Farm platform (Drummond, Reference Drummond2010), with the PennController module used for visual stimulus presentation (Zehr & Schwarz, Reference Zehr and Schwarz2018).

5.2. Participants

One hundred and thirty-eight adult participants took part in this study. Of those, 66 bilingual individuals were from the Gorizia and Trieste areas (51 female, age range = [18; 78], median = 32, median school years = 16) and 43 bilingual individuals were from Špeter/San Pietro al Natisone and the surrounding Natisone Valley area (33 female, age range = [18; 83], median = 39, median school years = 13). Both groups spoke Slovene as an HL. The control baseline for the Gorizia/Trieste group comes from the JERA standardization study: 517 monolingual Slovene speakers (316 female, age range = [18; 79], median = 38; see Stepanov et al. Reference Stepanov, Pavlič, Pušenjak Dornik and Stateva2024 for details regarding the standardization procedure). An additional control group comprised 29 monolingual Slovene speakers from the Kobarid region (13 female, age range = [18; 60], median = 34). They were age-matched to 31 heritage speakers from the Natisone group within the same 18- to 60-year range (median = 31) for comparative performance analysis.

The Gorizia/Trieste participants were local and first exposed to Slovene at home (95% at birth; the rest by age 3). Italian exposure was similarly early (86% at birth/by age 3; the remainder by age 6). Most (≈85%) attended Slovenian-medium schools, and 86% still lived in the area at testing. In adulthood, 45% (30 participants) had resided in Slovenia (mean 3.62 years).

The Natisone valley participants were born in that area and first exposed to Slovene at home (86% at birth; the remainder by age 3). Italian exposure was similarly early (86% at birth/by age 3; the rest by age 6). About one-third (34%) attended the bilingual primary school in Špeter before continuing in Italian-medium schools. The others were in Italian-medium schools from the start. In adulthood, 28% spent time in Slovenia (mean 2.06 years).

All participants maintained regular contact with both Slovene and Italian at the time of testing. They had normal or corrected-to-normal vision and hearing, were in good health and reported no neurological disorders. All participants provided informed consent. Participation was voluntary and anonymous. Bilingual participants received a small token of appreciation from the University as compensation for their time. The experimental procedure was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Nova Gorica (protocol no. 11/2020).

5.3. Participant survey on Slovene-language exposure

The bilingual participants completed a questionnaire specifically targeting contexts relevant to minority language exposure, in particular (i) home, (ii) schooling and (iii) peer/community interactions, in different time periods. The structure of the questionnaire is available in Supplementary Appendix B. For each context and period, a Likert scale (1–5) was used to quantify language use, where 1 and 5 indicated ‘only Slovene’ and ‘only Italian,’ respectively, and 3 indicated a balanced exposure. Time periods were broken down by age ranges 0–3, 3–6, 6–13 and 14–19 years, roughly corresponding to stages in the Italian education system. In addition, participants also indicated current exposure at the time of testing. For each participant, we calculated the life-time weighted Cumulative Exposure Index

![]() $ \boldsymbol{CE}{\boldsymbol{I}}_{\boldsymbol{W1}} $

as in the following equation:

$ \boldsymbol{CE}{\boldsymbol{I}}_{\boldsymbol{W1}} $

as in the following equation:

$$ CE{I}_{W1}=\frac{1}{Age}\ast \left[\sum \limits_{p=1}^{19}\left({\overline{L}}_p\ast {Y}_p\right)+{\overline{L}}_{now}\ast \left( Age-19\right)\right] $$

$$ CE{I}_{W1}=\frac{1}{Age}\ast \left[\sum \limits_{p=1}^{19}\left({\overline{L}}_p\ast {Y}_p\right)+{\overline{L}}_{now}\ast \left( Age-19\right)\right] $$

We first averaged the ratings across contexts within a period into the participant’s mean per-period coefficient

![]() $ {\overline{\boldsymbol{L}}}_{\boldsymbol{p}} $

, multiplied each

$ {\overline{\boldsymbol{L}}}_{\boldsymbol{p}} $

, multiplied each

![]() $ {\overline{\boldsymbol{L}}}_{\boldsymbol{p}} $

by the corresponding period’s length

$ {\overline{\boldsymbol{L}}}_{\boldsymbol{p}} $

by the corresponding period’s length

![]() $ {\boldsymbol{Y}}_{\boldsymbol{p}} $

in number of years until the age of 19 and added the similarly weighted coefficient

$ {\boldsymbol{Y}}_{\boldsymbol{p}} $

in number of years until the age of 19 and added the similarly weighted coefficient

![]() $ {\overline{\boldsymbol{L}}}_{\boldsymbol{now}} $

extrapolated up to the current age. The index is obtained by dividing the resulting sum by the speaker’s age, and it served as the main participant-level predictor of exposure in analyses of bilingual performance data (Section 5.6).Footnote 4

$ {\overline{\boldsymbol{L}}}_{\boldsymbol{now}} $

extrapolated up to the current age. The index is obtained by dividing the resulting sum by the speaker’s age, and it served as the main participant-level predictor of exposure in analyses of bilingual performance data (Section 5.6).Footnote 4

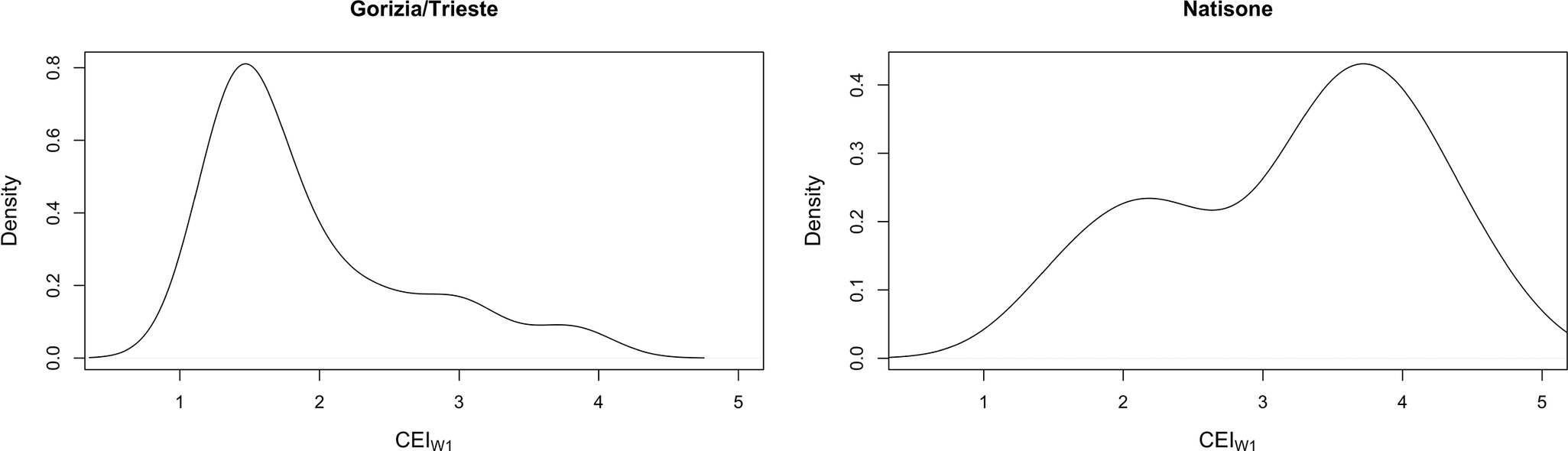

Figure 1 plots the density distribution of CEIW1 for both bilingual groups, showing a fairly consistent Slovene exposure bias of the Gorizia/Trieste speakers, while the Natisone group manifests a somewhat more heterogeneous distribution yet with a clear trend toward Italian.

Figure 1. Density plot for participant-level exposure index CEIW1 for the two HL groups.

To further investigate the per-period dynamics of language exposure, we ran a linear mixed-effects model with mean participant per-period coefficient

![]() $ {\overline{\boldsymbol{L}}}_{\boldsymbol{p}} $

as a dependent variable, population and exposure period as categorical fixed factors, and participant as a random factor, which revealed significant effects of population (χ2(1) = 74.66, p < .001), exposure period (χ2(4) = 58.99, p < .001) and their interaction (χ2(4) = 24.18, p < .001). Pairwise comparisons confirm consistent exposure differences across all periods, with the Natisone group showing a stronger Italian bias than the Gorizia/Trieste group, as reflected in the negative model estimates (Supplementary Appendix B, Table B1). Within-group comparisons confirm that the pattern of Slovene exposure is more stable for the Gorizia/Trieste group than for the Natisone group: the latter displayed an increasing Italian bias after age 3, which persisted until age 19 and became more balanced by the current period (Supplementary Appendix B, Table B2). We also calculated per-period coefficients broken down by specific contexts (home, education, peers/community) and plotted them in Supplementary Appendix B, Figure B1.Footnote 5 Institutional exposure, namely education, shows by far the largest mean separation, about 1.7 scale points, whereas home averages 1.1 and peers/community just under 1.0. The biggest single divergence occurs in the 14-19 window for education (Natisone 4.44 vs. Gorizia/Trieste 1.81, Δ = 2.63).

$ {\overline{\boldsymbol{L}}}_{\boldsymbol{p}} $

as a dependent variable, population and exposure period as categorical fixed factors, and participant as a random factor, which revealed significant effects of population (χ2(1) = 74.66, p < .001), exposure period (χ2(4) = 58.99, p < .001) and their interaction (χ2(4) = 24.18, p < .001). Pairwise comparisons confirm consistent exposure differences across all periods, with the Natisone group showing a stronger Italian bias than the Gorizia/Trieste group, as reflected in the negative model estimates (Supplementary Appendix B, Table B1). Within-group comparisons confirm that the pattern of Slovene exposure is more stable for the Gorizia/Trieste group than for the Natisone group: the latter displayed an increasing Italian bias after age 3, which persisted until age 19 and became more balanced by the current period (Supplementary Appendix B, Table B2). We also calculated per-period coefficients broken down by specific contexts (home, education, peers/community) and plotted them in Supplementary Appendix B, Figure B1.Footnote 5 Institutional exposure, namely education, shows by far the largest mean separation, about 1.7 scale points, whereas home averages 1.1 and peers/community just under 1.0. The biggest single divergence occurs in the 14-19 window for education (Natisone 4.44 vs. Gorizia/Trieste 1.81, Δ = 2.63).

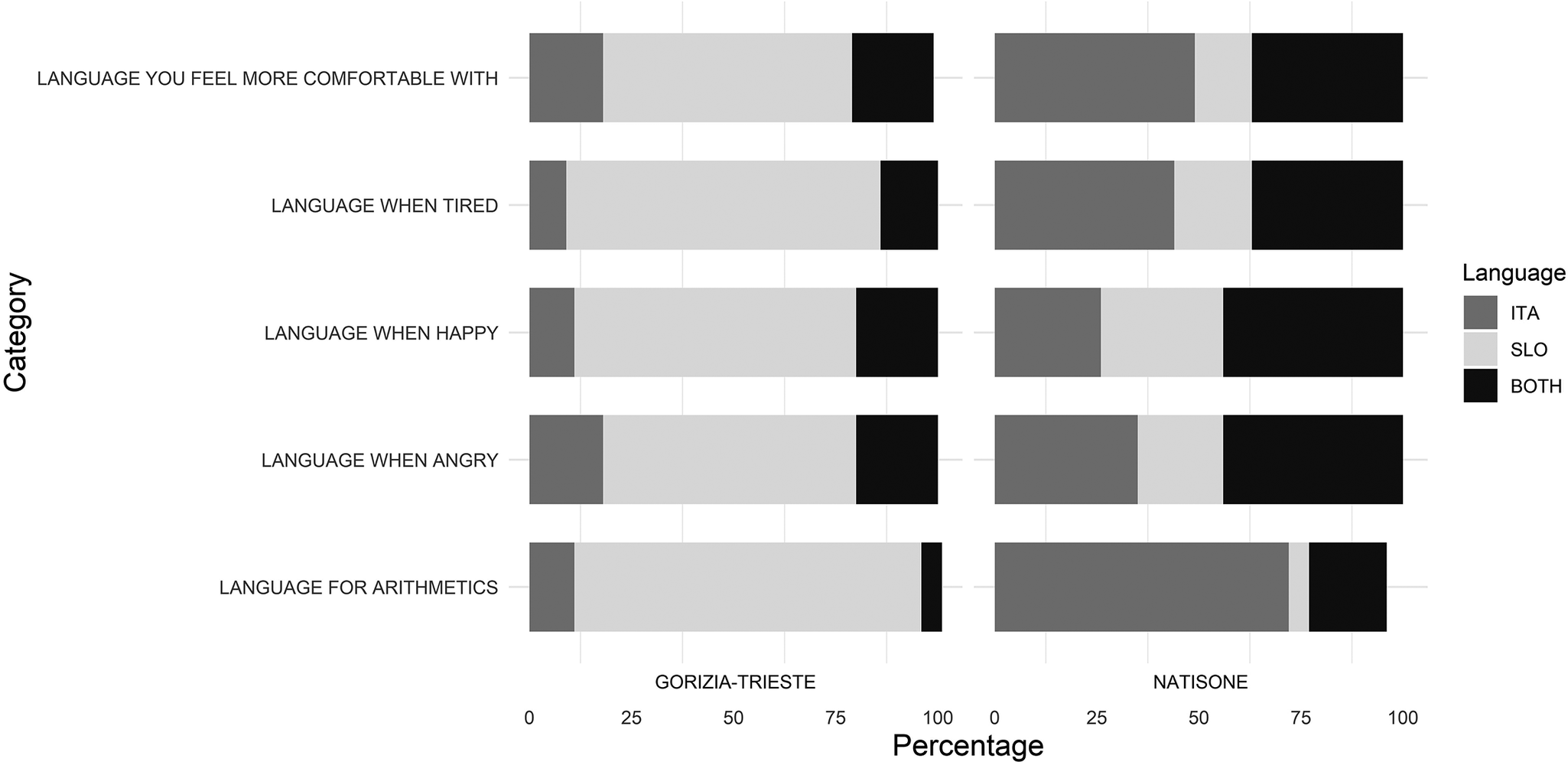

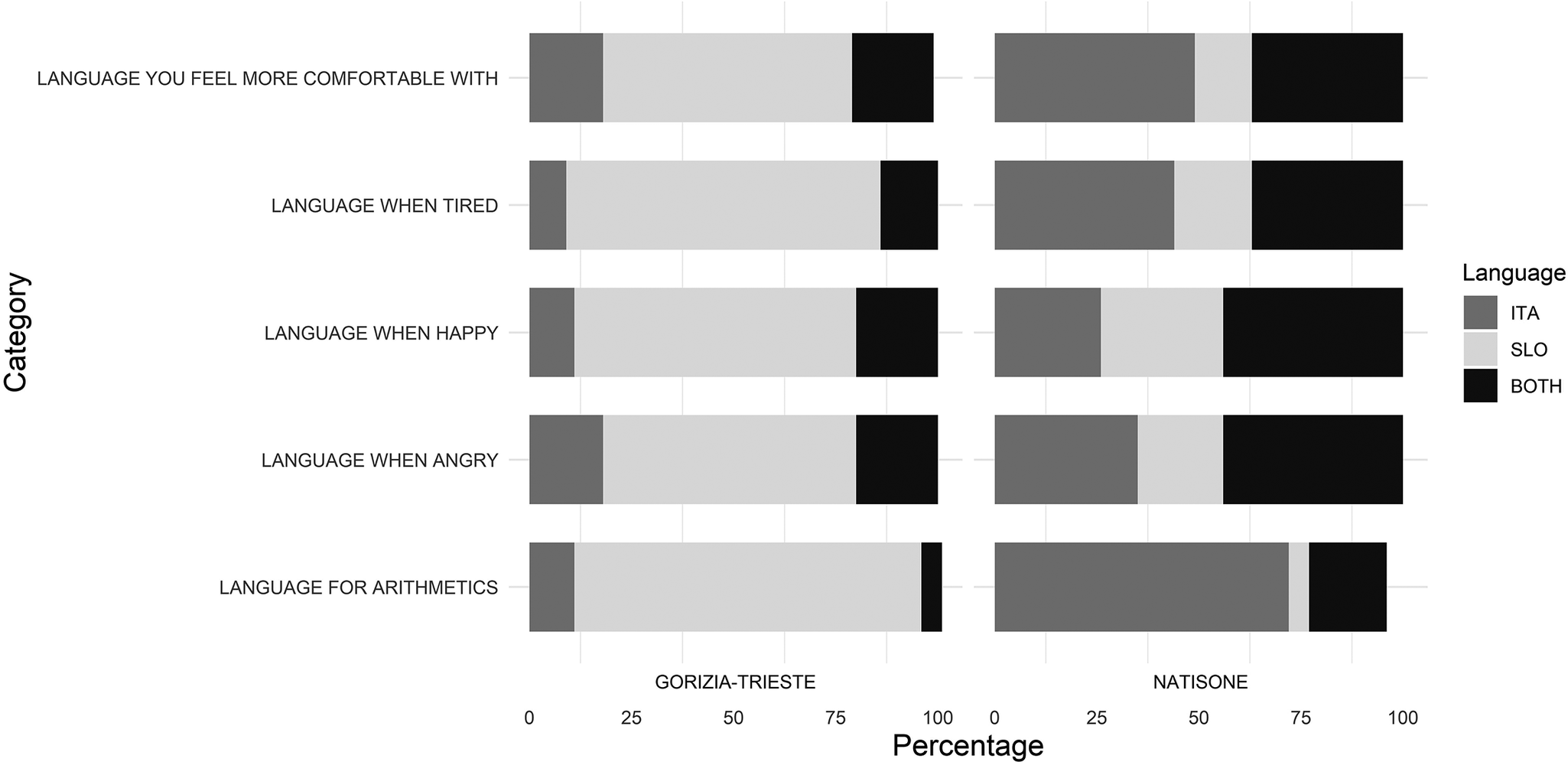

Figure 2 plots language use percentages in a number of functional and emotional contexts, showing a strong Slovene preference in the Gorizia/Trieste group. Notably, Slovene was also dominant in arithmetic tasks in this group, while Italian was preferred in the Natisone group, likely reflecting the language of schooling during early learning of numbers and arithmetic rules which become automatized in long-term memory (cf. Cerda et al., Reference Cerda, Suárez-Pellicioni, Booth and Wicha2024; Dehaene, Reference Dehaene1997).

Figure 2. Comparison of usage of the Slovene and Italian languages in specific circumstances, Gorizia/Trieste and Natisone Slovene speakers.

The overall picture that emerges from this comparison is that the Natisone population receives notably less input in the Slovene language than the Gorizia/Trieste group and is more isolated from the metropolitan influence in the sense explicated above. We did not collect a direct Italian proficiency measure in this study, a limitation that potentially constrains how sharply we can separate dominance/transfer effects from exposure per se. That said, as reviewed above, Italian is not expected to induce strong facilitative or distorting transfer for the specific contrasts we test (it lacks overt NP case and does not remove RC/cataphora integration costs), so the absence of an Italian proficiency covariate is unlikely to materially affect our core inferences.

5.4. Procedure

Testing was conducted in person (home, school or university) in quiet surroundings. Participants listened to sentences over headphones or loudspeakers at a comfortable volume. Each trial played the sentence while a central icon was shown. One thousand milliseconds after offset, four pictures appeared. Participants selected the matching image with one of four designated keys. An on-screen panel showed the key–corner mapping. After each response, a prompt (‘press any key to continue’) preceded the next trial. Trials were pseudo-randomized, and pauses were allowed only between trials. Three practice trials included feedback, whereas test trials did not. The task was self-paced with the experimenter present but non-intervening, and sessions lasted ca. 30 minutes.

5.5. Results

We compared the Gorizia/Trieste and Natisone heritage groups with their respective controls: the JERA normative sample and the Kobarid monolinguals (Section 5.1). We then modeled each heritage group’s performance as a function of demographic and exposure variables. Generalized logistic mixed-effects models for accuracy and linear mixed-effects models for response times (RTs) in R were constructed (Baayen, Reference Baayen2008; R Core Team 2022: version 4.2.2) using the lme4 package. Participant and stimulus item were always included in the random effects structure. The models were compared with respective null models by subtracting one of the fixed factors via a likelihood-ratio test using the anova function (χ2, α = .05) and reporting the respective χ2 and p values. Pairwise contrasts were estimated using the emmeans package with Tukey corrections for multiple comparisons.

5.5.1. The Gorizia/Trieste group

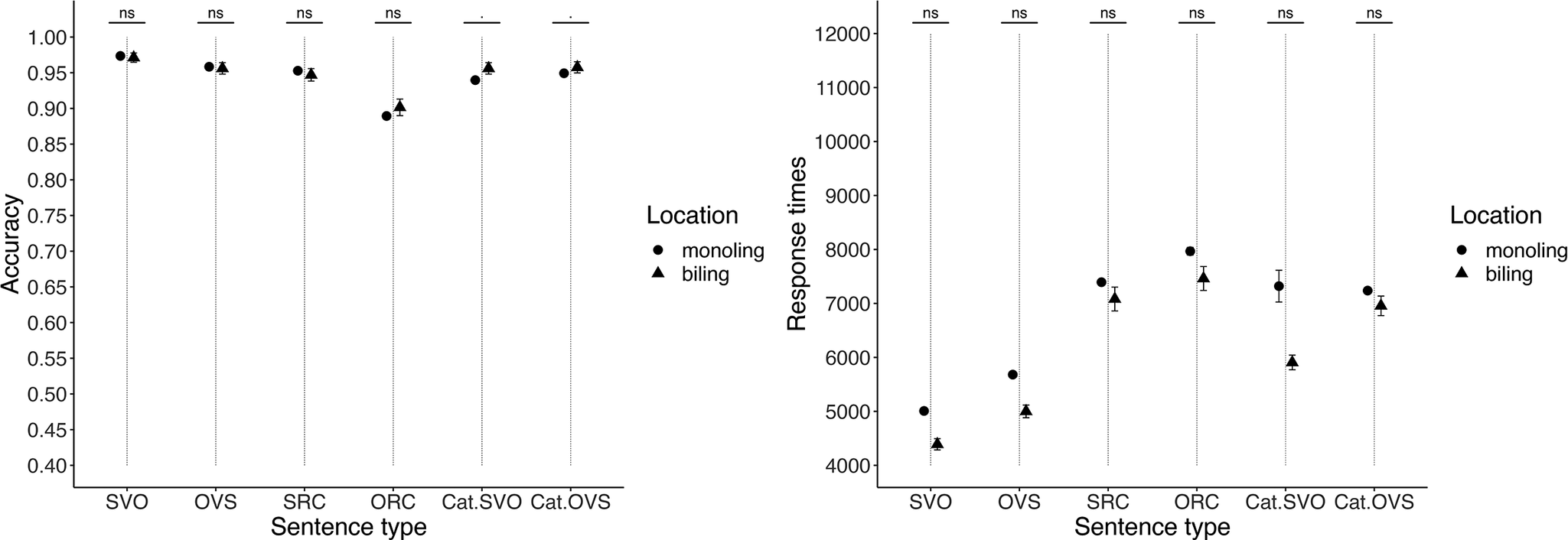

Accuracy. Performance was near ceiling: most participants scored 95–100%. One outlier (24% accuracy) was excluded, leaving 65 participants for analysis. Figure 3 (left) shows accuracy by sentence type relative to monolinguals; significance for the planned contrasts is indicated above the bars.

Figure 3. Accuracy (left) and response time (right) comparison, Gorizia/Trieste heritage speakers vs. monolingual controls. Error bars indicate standard errors.

The mixed-effects model (response ~ population [monolingual vs bilingual] + sentence type [6 levels] + random effects) showed no population effect (χ2(1) = 1.98, p = .15) and a main effect of sentence type (χ2(5) = 34.27, p < .0001), with no interaction (χ2(5) = 3.62, p = .60). Pairwise contrasts indicated broadly similar accuracy across types for bilinguals, with a marginal advantage on Cat.SVO and Cat.OVS (Supplementary Table C1). Across groups, accuracy was comparable for SVO vs. OVS and for cataphora items, and lower for ORCs than SRCs (for bilinguals, this was a trend; Supplementary Appendix C, Table C2). Note that items were not lexically uniform within each paired contrast (we balanced nouns/verbs across the whole test). Consequently, pairwise comparisons between sentence type pairs should be regarded as suggestive rather than definitive in our analyses.

Response times. There were very few responses under 200 ms (0.2%), and we imposed no upper RT bound; consequently, no participants were excluded on RT criteria. Figure 3 (right) plots RTs by sentence type relative to monolinguals. A linear mixed-effects model (RT ~ population + sentence type + random effects) showed no population effect (χ2(1) = 0.99, p = .31), a main effect of sentence type (χ2(5) = 28.29, p < .0001) and no interaction (χ2(5) = 1.72, p = .89). Bilingual RTs were comparable to those of monolinguals across types (Supplementary Table C3), and our planned contrasts (OVS–SVO; ORC–SRC; Cat.OVS–Cat.SVO) showed no reliable RT differences (Table C4); the omnibus effect is likely driven by pairs outside these contrasts (e.g., SVO vs. SRC).

5.5.2. The Natisone group

Accuracy. To ensure both groups are evaluated against a common baseline, we first compared the performance of the normative monolingual speakers used in the comparison with the Gorizia/Trieste group and that of the age/monolingual Kobarid group, on accuracy. Four participants in the Kobarid group had overall accuracy between 17 and 29% and were excluded from further analyses. The comparison revealed no effect of population (χ2(1) = 0.18, p = .67) and no significant contrasts across any of the target sentence types (all ps > .10).

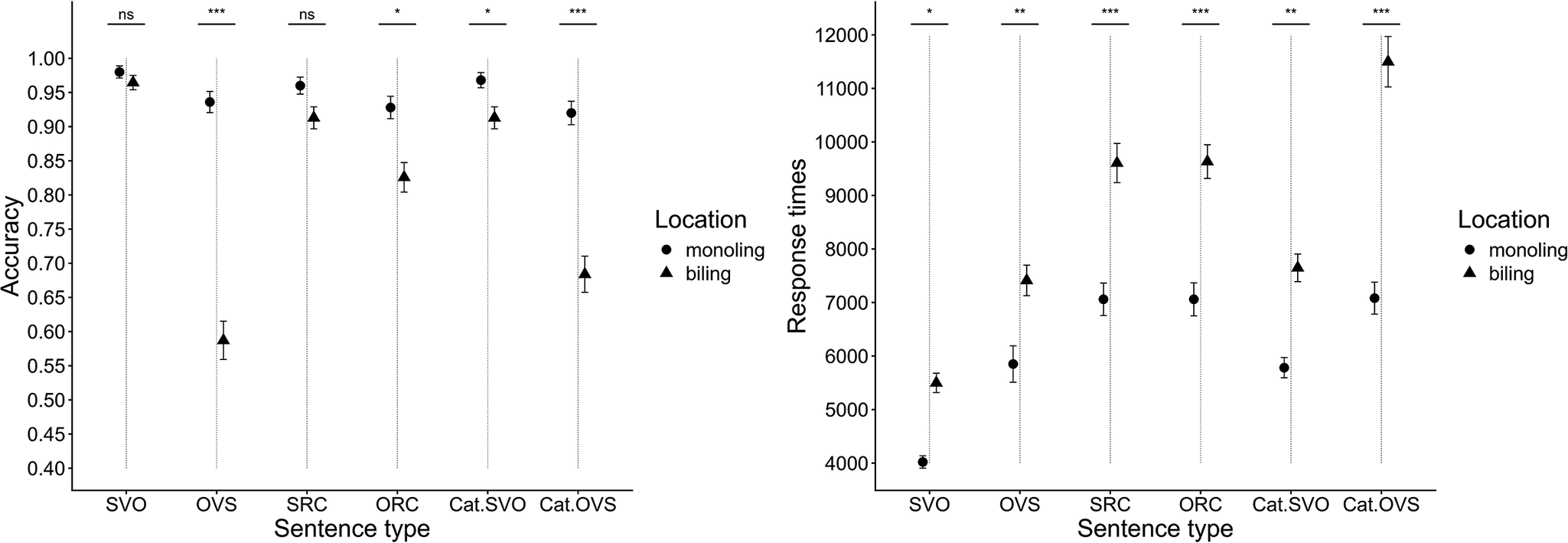

All participants in the Natisone group showed above-chance overall accuracy; no participants were excluded based on this criterion. The aggregated results are plotted in Figure 4 (left).

Figure 4. Accuracy (left) and response time (right) comparison, Natisone heritage speakers vs. monolingual controls. Error bars indicate standard errors.

The model of accuracy including population and sentence types as the fixed factors revealed strong effects of population (χ2(1) = 24.57, p < .0001), sentence type (χ2(5) = 65.15, p < .0001) and their interaction (χ2(5) = 29.51, p < .0001). Pairwise comparisons indicated that the Natisone speakers were less accurate than the monolingual controls on all types except SVO, the basic type, and SRC (Supplementary Table C5). Across sentence type pairs, the Natisone group performed notably worse on OVS compared to SVO and on Cat.OVS compared to Cat.SVO. The SRC vs. ORC contrast was not significant (Supplementary Table C6).

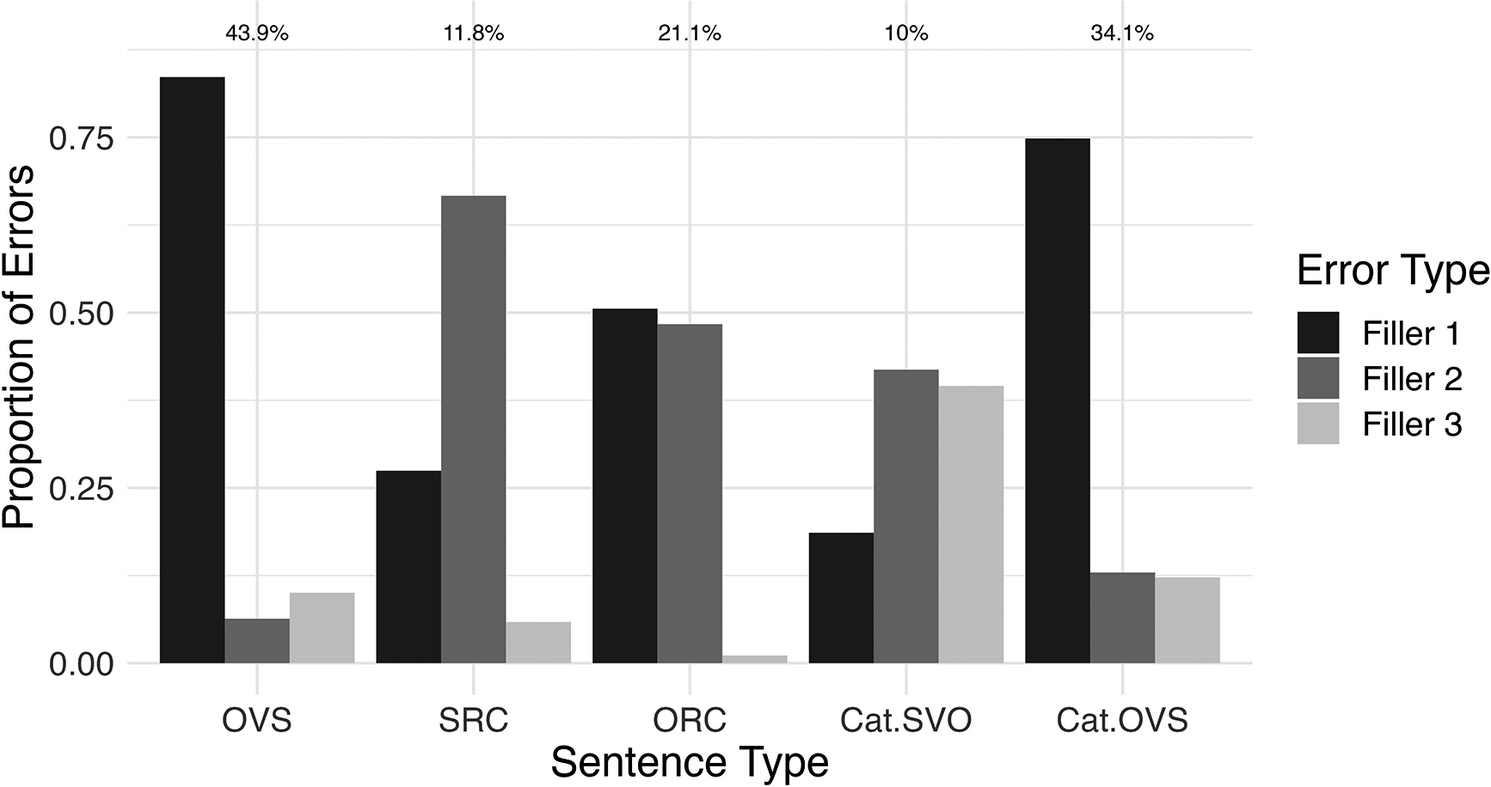

Analysis of errors. A breakdown of errors by sentence type is plotted in Figure 5, where ‘Filler#’ refers to one of the three erroneously selected non-target pictures.

Figure 5. Distribution of errors per sentence type by Natisone heritage speakers. On top are percentages of overall errors. See Supplementary Appendix D for an explanation of the event schemes in nontarget pictures (‘fillers’).

Non-target responses on marked OVS word orders manifested an overwhelming bias for Filler 1 (about 80% all responses) that encoded a reversal of actor roles in an argument structure (target event scheme: [A V1 B], Filler 1 scheme: [B V1 A]). Participants often treated the object in the initial position as the sentence’s subject and, conversely, interpreted the final-position subject as the object. A similarly robust proportion of Filler 1 responses is also found in Cat.OVS (about 75% responses), which involves a marked OVS order in the context of cataphora. Performance on SRC was biased toward Filler 2. SRC sentences involve two argument structures in the event scheme: [A V1 B, A V2 C], one in the RC and the other with the main verb and object. Filler 2’s event structure is [C V1 B, A V2 C], so it includes one of them, namely [A V2 C], identical to the target ones, whereas the other two fillers, Filler 1 and Filler 3, share no common argument structure (Supplementary Appendix D). Responses to ORC (target event scheme: [A V1 B, B V2 C]) included Filler 1 and Filler 2 equally. Filler 1 (event scheme: [B V1 A, A V2 C]) includes role reversal in the RC and object-to-subject substitution in the main clause, whereas Filler 2 (event scheme: [A V1 C, B V2 C]) retains the target argument structure in the main clause [B V2 C] while substituting the subject in the RC (similarly to Filler 1 in SRC). The observed biases preserving the main-clause argument structure but not the RC suggest reliance on main-clause cues with a reduced chance of integrating the RC. Comparable tendencies were also reported in production, in particular, simple juxtaposition in heritage Turkish avoiding RC structure (cf. Backus, Reference Backus, Bhatia and Ritchie2006). Finally, Cat.SVO, cataphora sentences with unmarked word order, manifested no statistically significant bias toward any of the three fillers (ps > .10 on all pairs).

Response times. Comparing normative monolinguals to Kobarid showed no population effect (χ2(1) = 0.02, p = .89) and no significant contrasts across the target sentence types (all ps > .10), indicating homogeneous RTs between these monolingual groups. Figure 4 (right) plots mean RTs by sentence type for Kobarid vs. Natisone. In the RT model (RT ~ population + sentence type + population × sentence type + random effects), we found main effects of population (χ2(1) = 20.56, p < .0001) and sentence type (χ2(5) = 40.10, p < .0001), and a population × sentence type interaction (χ2(5) = 38.27, p < .0001). The Natisone speakers were slower than monolinguals across all types (Supplementary Table C7) and, within sentence types, showed a selective cataphora-OVS > cataphora-SVO slowdown. Other planned contrasts were not significant.

5.6. Bilingual performance: Effects of exposure and demographic variables

For both heritage populations, we ran additional mixed-effects models to probe which demographic and exposure-related variables may have affected performance. Beside the sentence type (experimental factor), the CEIW1 index (Section 5.3), age, gender, highest education level, age of first exposure to Italian and, given the geographical proximity of our populations to the mainland, a separate parameter, RSL, reflecting the overall time of residence in Slovenia (in number of years), were included as fixed predictors.Footnote 6

5.6.1. The Gorizia/Trieste group

The model again showed near-ceiling performance (intercept ≈ 99% correct). Beside sentence type, two factors reached or approached significance: age, whereby each additional year trimmed accuracy by roughly .03 percentage points (β = –0.027, p = .01), and education level, whereby upper-secondary graduates scored about 2.7 points lower (β = –2.71, p < .001) and university graduates 1.7 points lower (β = –1.71, p = .003) than the primary school level. Because accuracy is already compressed at the top of the scale, we interpret these negative slopes as a small ceiling-related squeeze rather than a real proficiency loss. Neither the participant’s CEIW1, gender, age of first Italian exposure nor potential residence in Slovenia significantly affected the participants’ ceiling-like accuracy, likely due to restricted variance in the data. The RT model tells a complementary story: age slows responses by about 70 ms per year (β = 70, p < .001), while no other demographic or exposure factors affected the latency of responses.

5.6.2. The Natisone group

The Natisone heritage bilinguals showed a different pattern. In the accuracy model, sentence type again drove the largest contrasts, but CEIW1, our proxy for sustained input, showed a main effect in the expected direction: a one-SD shift in the coefficient toward Italian dominance predicted a 4–5 percentage-point drop in accuracy (β = –0.55, p = .051). Furthermore, university graduates outperformed the baseline by about 2.4 points (β = 2.42, p = .012); the upper-secondary contrast was positive but non-significant. Age, gender, first exposure to Italian and residence in Slovenia did not reach conventional significance, although chronological age showed a weak negative trend (β = –0.024, p = .08). Processing speed reinforces these patterns, whereby a one-SD increase in Italian-dominant exposure slows decisions by ~2 s (β = 1976, p = .009). In addition, there is a marginal effect of exposure to Italian, indicating that each year’s delay in first exposure to Italian adds ~0.8 s to the participants’ responses (β = 548, p = .09).

6. Discussion

The Gorizia/Trieste speakers, surrounded by dense Slovene-medium institutions, performed on a par or even better than the monolingual speakers of Slovenia across sentence types. In contrast, the Natisone speakers whose institutional networks are weaker were significantly less accurate and slower in responding than the monolingual controls. The complementary profiles of the two in-situ heritage communities support the view that community support modulates performance independent of the geographical proximity to the mainland. We first report results by sentence type against the predictions (Section 4) before outlining some wider theoretical repercussions of our findings.

6.1. Word order and morphology

As predicted in P1 (Section 4), the Natisone group showed reduced sensitivity to nominal morphology, leading to difficulties with marked OVS word order. The Natisone speakers seem to rely more on the word order strategy than on the case marking strategy in determining grammatical functions of NP, interpreting clause-initial objects as subjects. In this aspect of morphosyntactic knowledge, the Natisone speakers pattern similarly to heritage speakers in immigrant settings (de Groot, Reference De Groot and Fenyvesi2005; Leisiö, Reference Leisiö2006; Polinsky, Reference Polinsky2006). Whether this reflects divergent acquisition under reduced input or later attrition of an originally full paradigm cannot be determined from the present cross-sectional data, but in either scenario, the reduced nominative–accusative contrast limits the heritage group’s ability to override first-position heuristics.

Conversely, the Gorizia/Trieste speakers showed no difficulty with case marking. Despite similar sociopolitical factors, they exhibited a comprehension pattern similar to monolingual Slovene speakers, indicating a strong grasp of nominal morphology regardless of word order. Models that included the CEIW1 index show that input quantity is a reliable predictor of performance in the Natisone group. No such effect emerges in the Gorizia/Trieste group, whose Slovene exposure is near ceiling. These results confirm that sustained formal and informal exposure, rather than mere geographical proximity, underpins the maintenance of the case system: where input is reduced, the paradigm remains only partially acquired or undergoes attrition.

6.2. Relative clauses

The Gorizia/Trieste speakers processed subject and object RCs similarly to monolinguals, indicating their sentence processing system is equally sensitive to the structural properties and complexity of these sentence types. In contrast, the Natisone speakers showed lower accuracy on object RCs and longer RTs on both subject and object RCs compared to monolinguals, suggesting a broader processing limitation than was predicted in P2 (Section 4). This finding aligns with the literature suggesting that limitations in processing resources and the added cost of handling a less proficient language affect HL acquisition and use (Grodner & Gibson, Reference Grodner and Gibson2005; Kaltsa et al., Reference Kaltsa, Tsimpli and Rothman2015; Keating et al., Reference Keating, VanPatten and Jegerski2011; Levy et al., Reference Levy, Fedorenko and Gibson2013; Lohndal, Reference Lohndal, Montrul and Polinsky2021; Polinsky, Reference Polinsky2018; Polinsky & Scontras, Reference Polinsky and Scontras2020). The analysis of errors further indicated that the Natisone speakers tended to interpret ORCs as SRCs, in line with the previous findings (Section 3.2).

One potential source of the Natisone group’s difficulty may lie in the center-embedded structure of RCs used in our stimuli: listeners must keep the relativized noun active until they reach the main verb, and reduced exposure may leave them with fewer resources for maintaining that dependency. This account meshes with evidence that bilinguals co-activate lexical items from both languages (Costa et al., Reference Costa, Caramazza and Sebastián-Gallés2000) and that the dominant language can interfere with lexical selection (Green, Reference Green1998). Thus, for the Natisone speakers, an Italian competitor may intrude while the Slovene head noun is being held in working memory, increasing the load at the point of integration. This would account for the greater latency on both types of RCs. Another, complementary, possibility is rooted in morphology. Earlier studies show that heritage speakers are less reliable at using nominative–accusative endings once input is reduced (Polinsky, Reference Polinsky2011; Putnam & Salmons, Reference Putnam and Salmons2013). In an object RC, the accusative head precedes a nominative embedded subject, so linear position and weakened case cues point in opposite directions; subject relatives place the nominative head first, allowing word order to reinforce the expected case pattern. The Natisone accuracy gap can therefore be read either as a storage-and-integration burden, as a morphology-by-position conflict or, plausibly, as a combination of both factors. Further work that manipulates case transparency independently of embedding depth will be needed to decide which component is primary.

Finally, we found no reliable SRC–ORC differences in RTs in any group, including the monolingual baselines, and no SRC–ORC accuracy differences within the two heritage groups. We surmise that the absence of contrasts reflects the combination of center-embedding in our RCs and the specifics of the task. In a sentence–picture verification paradigm, the end-of-trial decision latency is a coarse, late measure involving post-interpretive picture matching, which often fails to register the SRC advantage typically seen in online paradigms (Section 3.2). Prior work shows that, in this task, decision latencies are driven by RC position (center-embedded vs. right-branching) and that no global SRC–ORC RT advantage emerges in typical or dyslexic adults, even when accuracy asymmetries do (Wiseheart et al., Reference Wiseheart, Altmann, Park and Lombardino2009). A similar consideration applies to accuracy: detecting this asymmetry in such a coarse task requires larger samples (as in our monolingual group), whereas the smaller bilingual samples limit power. Accordingly, we do not interpret the null RT and accuracy contrasts as evidence against an underlying SRC advantage in this paradigm.

6.3. Cataphora

The Gorizia/Trieste group performed exceptionally well on this sentence type. In contrast, the Natisone speakers, although above chance, were slower and less accurate, in line with P3. Successful resolution of a pro-drop cataphoric dependency involves several key steps: (i) identifying the silent pro, (ii) initiating an active search for an antecedent and (iii) establishing coreference with the pro while maintaining its trace in working memory, subject to reanalysis (Kazanina et al., Reference Kazanina, Lau, Lieberman, Yoshida and Phillips2007; van Gompel & Liversedge, Reference Van Gompel and Liversedge2003). While steps (i) and (ii) are not likely to be affected, especially given that Slovene and Italian are both pro-drop languages (cf. Section 3.3), step (iii) is not trivial even for monolinguals who show a consistent preference for selecting the NP that comes first as the antecedent of the null pronoun in cataphora even if that NP is the object, leading to erroneous coreference as in Cat.OVS (Carminati, Reference Carminati2002; Fedele & Kaiser, Reference Fedele and Kaiser2014; Pavlič & Stepanov, Reference Pavlič and Stepanov2023; Sorace & Filiaci, Reference Sorace and Filiaci2006). Because of that, the Natisone speakers might require additional processing resources to verify the antecedent for the silent pro in Cat.SVO, which could explain their slower RTs. The bias toward Filler 1 with reverse argument structure in Cat.OVS also supports this interpretation.

Related to this point, Kaltsa et al. (Reference Kaltsa, Tsimpli and Rothman2015) found that heritage Greek speakers and L1 attriters in Sweden had higher RTs than monolingual Greek controls when resolving anaphoric dependencies with both overt and null pronouns. As they note, ‘…in cases of extensive attrition or early bilingualism of heritage speakers the processing (but probably not the representation) of null subjects is affected causing more delay in choosing the appropriateness of a subject antecedent than in the monolingual grammar’ (p. 283).

However, in the case of Cat.OVS, we believe it is only part of the explanation. The literature suggests that morphological information in cataphora resolution is used after coreference relations are computed in monolingual speakers (Pavlič & Stepanov, Reference Pavlič and Stepanov2023; van Gompel & Liversedge, Reference Van Gompel and Liversedge2003). Thus, even if case morphology were fully functional in the Natisone speakers, the erroneous assignment of pro to the object in Cat.OVS would not be ruled out by the non-matching accusative case. We suggest that a different sort of difficulty arises because of the need for reanalysis, which requires additional processing resources, thereby limiting the Natisone speakers’ performance. This hypothesis is supported by the RT data: the effect size of the difference between the two groups on Cat.OVS is greater than on OVS, with the Natisone speakers taking nearly twice as long to respond. At the same time, we also cannot exclude a representational contribution. Given their reduced and discontinuous input, Natisone listeners may never have fully consolidated the syntactic constraints on silent pronouns (cf. Montrul, Reference Montrul2015, Reference Montrul2023). Further studies should be able to tease apart these two possibilities.

6.4. Differential input in in-situ contexts

In sum, the Natisone speakers face at least three different kinds of difficulties in the sentence comprehension domain: (i) vulnerability of case morphology, (ii) processing limitations and (iii) the combination of both. In contrast, the Gorizia/Trieste speakers exhibited no deficiencies in these areas.

Heritage speakers’ poor performance on nominal case morphology is commonly attributed to (i) insufficient input, especially in the later stages of language development, leading to incomplete acquisition and/or attrition of the morphological case system, especially in the context of a dominant language with impoverished morphology (Polinsky, Reference Polinsky2011; Uygun & Clahsen, Reference Uygun and Clahsen2021); and (ii) limited processing resources, whereby heritage speakers have to operate in a non-dominant language, which places a higher cognitive load on their processing abilities (Polinsky Reference Polinsky2018; Uygun & Clahsen, Reference Uygun and Clahsen2021). These factors promote reliance on word order for role assignment, especially in Italian-dominant contexts where SVO is the default, yielding ‘first-NP = subject’ as the default or prioritized parsing strategy (cf. Section 3.1). This also likely accounts for the Natisone speakers’ difficulties with center-embedding structures (Section 6.2) and establishing cataphoric links (Section 6.3).

These findings suggest that border-shift contexts may lead to reduced sensitivity to overt morphology and a smaller pool of resources for processing complex syntax. The magnitude of these effects depends on the amount and quality of HL exposure across development and adulthood, which in in-situ settings is shaped primarily by local circumstances. In practice, institutional support, especially schooling in Slovene, drives exposure more than linguistic factors. Limited support in Natisone reduces exposure and depresses performance, whereas stronger support in Gorizia/Trieste sustains exposure and yields monolingual-like outcomes. The amount of exposure then is a fraction of the regular exposure available to the monolingual speakers in the mainland. Taken together, the parallel analyses show that the quality and density of local institutional support rather than geopolitical realignment explains the divergent outcomes in these two neighboring in-situ communities.

Cross-linguistic influence from Italian could offer an alternative account of some, but not all, of the patterns observed. For word order, Italian’s comparatively more position-dependent SVO canon aligns with the ‘first-NP=subject’ heuristic. OVS word orders can occur as well under certain conditions of semantic-pragmatic nature. Crucially, however, case morphology does not serve as a reliable cue to disambiguate grammatical functions (e.g., Bates et al., Reference Bates, MacWhinney, Caselli, Devescovi, Natale and Venza1984), thus predicting the OVS errors in Slovene seen in the Natisone speakers. This overlap reinforces rather than contradicts our input-based explanation. For case morphology, the absence of overt case in Italian NPs would indeed predispose heritage speakers to ignore Slovene endings (cf. Polinsky, Reference Polinsky2011; Putnam & Salmons, Reference Putnam and Salmons2013). We may treat this as a contributing factor. In RCs, however, Italian does not ease the specific load of center-embedding, so Italian input would facilitate SRCs equally in the two groups but would not add the extra accuracy penalty for ORCs or increased response latencies for both types that we observe in the Natisone speakers. Finally, cataphoric null subjects are grammatical in Italian (Section 6.3), so transfer should help rather than hinder Slovene cataphora. The slowdown we find in Natisone thus cannot be attributed to negative transfer. Taken together, Italian influence can account for the word order bias and part of the case difficulty, but it does not explain the structure-specific disadvantages that emerge only when Slovene exposure is scarce.

Our results can be framed within two sociolinguistic accounts of HL development, which offer some relevant benchmarks characterizing language input and exposure in the case of HL. We draw in particular on Paradis (Reference Paradis2023), which distinguishes child-internal factors (e.g., age of acquisition, cognitive abilities, socioemotional well-being) from child-external factors, the latter split into proximal (cumulative HL exposure, home use, richness of HL environment) and distal (literacy/education in the HL, parent HL proficiency, family socioeconomic status, attitudes/identities). Proximal factors pertain to direct input, output and interaction, while distal factors describe broader environmental characteristics influencing proximal factors.

Although Paradis focuses on childhood, the model isolates three exposure sources that remain diagnostic for adult HL competence: (i) parent proficiency, (ii) HL use at home and (iii) education/institutional support. Our findings underscore the weight of these input characteristics, especially education/institutional density (see also Unsworth, Reference Unsworth, Schmid and Köpke2019), and provide a basis for classifying in-situ communities by the amount and quality of HL input their members receive across development.

Bickerton’s (Reference Bickerton1973) model of creolization explains how creoles arise from language contact in contexts with limited access to a full linguistic system, using the concepts of acrolect, mesolect and basilect. The acrolect is spoken by those with greater exposure to the dominant language, while the basilect represents the most ‘creolized’ form, with minimal exposure. Mesolects occupy an intermediary position. Polinsky and Kagan (Reference Polinsky and Kagan2007) propose adapting this framework to characterize different varieties of HL, where retention of baseline grammatical features varies. In their adaptation of Bickerton’s model, varieties resembling the baseline are akin to acrolects, while those with substantial divergence align with basilects, forming a continuum based on exposure and isolation. This approach incorporates relative distance as a measure of isolation or remoteness from the baseline and organizes varieties on a continuum from closest to farthest from the baseline. Applied to the in-situ context, this model has potential to capture this relative distance as correlating with differing input quality and quantity. For instance, the Gorizia/Trieste Slovene variety, supported by extensive formal and informal input, would qualify as an acrolect in this system. In contrast, the Natisone variety, marked by reduced performance in case morphology and word order, would likely fall into the mesolect or basilect category. Other HL communities can enter this typology as well, depending on the degree of retention of relevant grammatical features from Standard Slovene in their respective varieties.

The two models and their adaptations emphasize different aspects of HL exposure and input. Paradis’ model highlights sociolinguistic indicators of HL exposure to gauge distance from the baseline, while Bickerton’s creolization model, adapted to HL, focuses on grammatical and performance indicators that define placement on the baseline-referenced continuum. Together, these frameworks provide possible lines of exploration in linking the patterns of heritage speakers’ performance to sociolinguistic indicators of input and exposure that affect the shape of their grammatical competence and its everyday use.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://osf.io/hd74w/.

Data availability statement

The experimental stimuli, raw data and R scripts used in the analyses will be made available upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Penka Stateva, Agata Koren and three anonymous reviewers for their useful feedback, Mira Tavčar and Maja Melinc Mlekuž for their valuable assistance with data collection and Živa Gruden for her help with participant recruitment. The authors also warmly acknowledge the Landscape and Narrative Museum SMO in Špeter Slovenov/San Pietro al Natisone and the editorial board of Novi Matajur magazine in Čedad/Cividale del Friuli for hosting our data collection. Their support greatly contributed to the completion of this study.

Funding statement

This work has been financially supported by the Slovenian Research and Innovation Agency (ARIS) under project no. J6-3130. Portions of this material have been presented at the RUEG 2023 conference on Linguistic Variability in Heritage Language Research at Humboldt University, Berlin, and at the 16th European Conference on Formal Description of Slavic Languages at the University of Graz.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.