Studies investigating the impact of a mother's experiences of maltreatment in her own childhood (henceforth referred to as ‘maternal child maltreatment’) suggest an association with elevated rates of offspring emotional and behavioural difficulties across childhood and adolescence. Reference Myhre, Dyb, Wentzel-Larsen, Grogaard and Thoresen1–Reference Miranda, de la Osa, Granero and Ezpeleta10 Some of these studies have tested for mediating effects, with maternal mental health difficulties and maladaptive parenting practices most frequently observed to be significant mediators of the association between maternal child maltreatment and child emotional and behavioural difficulties. Reference Myhre, Dyb, Wentzel-Larsen, Grogaard and Thoresen1,Reference Min, Singer, Minnes, Kim and Short3,Reference Collishaw, Dunn, O'Connor and Golding5–Reference Roberts, O'Connor, Dunn and Golding7,Reference Miranda, de la Osa, Granero and Ezpeleta10 However, it is widely recognised that many factors that influence child well-being do not occur in isolation, but are often influenced by other factors, many of which commonly go unmeasured. Reference Thapar and Rutter11 For example, although much research has demonstrated a link between maternal mental health problems and child emotional and behavioural difficulties, Reference Sanger, Iles, Andrew and Ramchandani12–Reference Barker, Copeland, Maughan, Jaffee and Uher16 contemporary research suggests that maternal affective symptomatology during pregnancy increases risk for child psychopathology independently to risk conferred by later maternal affective problems, such as during the postnatal period and the child's later developmental years. Reference Pawlby, Hay, Sharp, Waters and Pariante17–Reference O'Donnell, Glover, Barker and O'Connor19 Although researchers have demonstrated an association between maternal child maltreatment and increased risk of maternal affective problems specifically in pregnancy, Reference Plant, Barker, Waters, Pawlby and Pariante4 the mediating effect of perinatal mental health in the association between maternal child maltreatment and preadolescent emotional and behavioural difficulties has not yet been examined. Similarly, child maltreatment is another factor that adversely affects psychological development and well-being, such that children who have experienced maltreatment have been observed to experience greater emotional and behavioural difficulties. Reference Appleyard, Egeland, van Dulmen and Sroufe20–Reference Thornberry, Ireland and Smith23 However, how offspring child maltreatment is related to the association between maternal child maltreatment and offpsing adjustment problems remains unclear. Reference Plant, Barker, Waters, Pawlby and Pariante4,Reference Thompson6,Reference Miranda, de la Osa, Granero and Ezpeleta9

The overarching aim of the present study was to characterise the pathways that underpin the association between maternal child maltreatment and child internalising and externalising difficulties in preadolescence. We tested a model of multiple parallel and serial mediation trajectories that assessed for the independent and cumulative mediating effects of maternal antenatal depression, maternal postnatal depression, maternal maladaptive parenting and child maltreatment. The following predictions were made: (a) maternal child maltreatment will predict child internalising and externalising difficulties separately; (b) maternal antenatal depression, maternal postnatal depression, maternal maladaptive parenting and child maltreatment will operate as independent mediators; (c) there will be an indirect effect of maternal antenatal depression through subsequent maternal postnatal depression, maladaptive parenting and child maltreatment demonstrating separate cumulative effects; (d) there will be an indirect effect of maternal postnatal depression through maladaptive parenting and child maltreatment demonstrating separate cumulative effects.

Method

Participants and design

The Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC) is a UK longitudinal birth cohort of mother-child dyads. All pregnant women resident in the former Avon Health Authority in southwest England having an estimated date of delivery between April 1991 and December 1992 were invited to take part; 14541 pregnant women were recruited. Reference Fraser, Macdonald-Wallis, Tilling, Boyd, Golding and Davey Smith24 For the present study, mother-child dyads were included if (a) the child was alive at 1 year, and (b) full data on the mother's history of childhood maltreatment were available. This resulted in a sample of 9397 mother-child dyads. Basic sociodemographic characteristics of this sample are presented in Table 1. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the ALSPAC Ethics and Law Committee and the Local Research Ethics Committees.

Table 1 Sociodemographic characteristics of the sample

| Characteristic | % |

|---|---|

| Maternal level of education | |

| O levels | 51.4 |

| Vocational qualification | 9.2 |

| A levels | 24.7 |

| Bachelor degree | 14.7 |

| Maternal partnering status | |

| Partner | 96.3 |

| Single | 3.7 |

| Child gender | |

| Male | 51.5 |

| Female | 48.5 |

| Child ethnicity | |

| White | 96.7 |

| Black | 0.2 |

| Asian | 0.2 |

| Mixed race | 2.7 |

| Other ethnicity | 0.1 |

A longitudinal design was employed. Maternal-and-child-based data were retrieved primarily from maternal-rated postal questionnaires sent at various time points between pregnancy and child age 13 years, as well as from child-rated questionnaires completed at age 8.

Measures

Maternal child maltreatment

Maternal experience of physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional abuse and neglect during childhood (< 18 years) was rated from maternal self-report questionnaire data collected at 12 and 32 weeks' gestation and 2 years 9 months. At 12 weeks' gestation mothers were asked if they had been sexually assaulted as a child (yes/no). At 32 weeks' gestation mothers were asked if they had been sexually abused as a child (yes/no), if they had experienced childhood physical cruelty (yes/no) or childhood emotional cruelty (yes/no). At 2 years 9 months, mothers were asked if they had been emotionally or physically neglected as a child (yes/no) as well as if they had been physically abused as a child (yes/no). As there was limited information on details such as duration or onset of maltreatment experiences, binary variables of each type of historical abuse and neglect as rated at any of the three time points of assessment were generated. These were used to generate a binary variable of maternal child maltreatment: mothers who answered ‘yes’ to any form of abuse or neglect were rated as having experienced child maltreatment (1), whereas mothers who reported no instances of abuse or neglect were rated as non-maltreated (0). A continuous variable was also generated that summed the number or types of maltreatment reported (0–4).

Maternal antenatal depression

Expectant mothers completed the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) Reference Cox, Holden and Sagovsky25 at 18 and 32 weeks of pregnancy. Expectant mothers were rated as ‘depressed’ (1) v. ‘non-depressed’ (0) using the advised cut-off of ⩾ 13 to identify women who were likely depressed, based on the highest score from the two time points.

Maternal postnatal depression

Mothers completed the EPDS at 8 weeks postnatal and 8 months postnatal. Mothers were also rated as ‘depressed’ (1) v. ‘non-depressed’ (0) based on a score of ⩾ 13 at either time point.

Maternal maladaptive parenting

At 3 years 11 months the mothers reported on their parenting practices. Mothers reported on their use of shouting and slapping and feelings of hostility towards their child. Shouting and slapping behaviour was rated separately and coded as present if mothers reported daily use of each of these behaviours (for example how often do you shout at/slap your child?). Mothers answered yes or no to questions about how often they got irritated with their child and having a battle of wills with them. A binary variable of maladaptive parenting (present (1) v. absent (0)) was generated in which maladaptive parenting was rated as presented if mothers were rated as expressing any of these types of behaviours/attitudes. A continuous variable was also generated that summed the number of reports of maladaptive parenting indices (0–4).

Child maltreatment

Mothers reported on their child's experience of physical (for example child was physically hurt by someone (yes/no)) and sexual abuse (for example child was sexually abused by someone (yes/no)) at 1 year 6 months, 2 years 6 months, 3 years 6 months, 4 years 9 months, 5 years 9 months, 6 years 9 months and 8 years 7 months. At 1 year 6 months the mothers were asked about their child's physical and sexual abuse experiences since the child was 6 months old, and at all further time points mothers rated abuse experienced for the time interval between the current and preceding assessment. At 8 months postnatal, 1 year 9 months, 2 years 9 months, 3 years 11 months and 6 years 11 months, mothers rated their child's experience of emotional abuse (for example mum or partner has been emotionally cruel to child? (yes/no)). The first rating was based on experiences since birth, with all subsequent rating based on the interval between successive assessment time points. Separate binary variables of physical abuse, sexual abuse and emotional abuse were generated based on ‘yes’ ratings for each abuse type at any time interval. At 8 years 6 months the children self-reported on their experiences of peer victimisation using the Bullying and Friendship Interview Schedule. Reference Wolke, Woods, Bloomfield and Karstadt26 A child was classed as having experienced peer victimisation if they were rated as having experienced at least one type (overt, relational) of peer victimisation. Finally, a binary variable (maltreated (1) v. non-maltreated (0)) was generated indicating a child to have been maltreated based on positive ratings of at least any one type of abuse (sexual, physical, emotional) or victimisation experience. A summed variable was also generated based on the number of counts of abuse and victimisation experienced by a child (0–4).

Child preadolescent emotional and behavioural difficulties

At 10 years 8 months and 13 years 10 months, mothers completed the Development and Well-being Assessment (DAWBA), Reference Goodman, Ford, Richards, Gatward and Meltzer27 and at 11 years 8 months they completed the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ). Reference Goodman28 At 10 years 8 months and 13 years 10 months, maternal ratings of child depressive symptoms in the past month were summed separately to generate two measures (10, 13 years) of DSM-IV depression symptoms (0–12) 29 Similarly, maternal ratings of symptoms of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), conduct disorder and oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), based on presence in the past 6 months for ADHD and ODD, and past 12 months for conduct disorder, were summed for each time point separately to generate a 10-year and 13-year measure of DSM-IV disruptive behaviour disorder (DBD) symptoms (0–34). Individual subscale scores of the SDQ at 11 years 8 months were used as measures of 11-year emotional and behavioural problems.

Confounding variables

Mothers reported on their partner status at 8 months (1, single; 0 partnered), their level of education at 32 weeks of pregnancy (non-completion of school, 0; O levels, 1; vocational qualification, 2; A levels, 3; and bachelor degree or greater, 5) and their smoking (number of cigarettes per day) and drinking (number of drinks per day) during pregnancy at 32 weeks' gestation. At 12 weeks' gestation mothers were asked if they had ever experienced severe depression, anorexia nervosa, schizophrenia, alcoholism or a drug addiction (yes/no). Mothers were rated with a psychiatric history if they answered yes to one form of psychiatric problem (history, 1; no history, 0). At 1 year 9 months the mothers reported on their perceived level of social support on a 10-item questionnaire, whereby higher scores indicated greater social support, and lower scores less perceived social support. Notably, many of these factors occurred in aggregation, suggesting cumulative risk. Child gender was coded 0, boy; 1, girl.

Data analysis

Data analysis proceeded in four main steps. First, univariate associations between study variables were analysed to determine the relationship between maternal child maltreatment and measures of child psychopathology, as well as to identify potential mediators and confounders to this association. At the second step, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was applied to evaluate whether a two-factor model of child internalising and externalising difficulties was appropriate. At the third step, structural equation modelling (SEM) was conducted through the estimation of structural regression models with the aim of testing the predictive effect of maternal child maltreatment on child internalising and externalising difficulties. Finally, mediation analysis was conducted to assess mediating pathways.

Statistical analyses were conducted in IBM SPSS Statistics Version 21 and Mplus Version 7.1. Reference Muthen and Muthen30 Data were assessed for normality using probability–probability plots and the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, and for homogeneity of variance using Levene's test. For data that did not satisfy tests of normality and homogeneity of variance, non-parametric statistical tests were applied. Multicollinerarity between variables was assessed using the variance inflation factor. Parameter estimates were computed using maximum likelihood estimation in all CFA and SEM models. Fit indices included the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), the standardised room mean square residual (SRMR) and the model chi-square (χ2 M)- A CFI ⩾0.95 is suggestive of a good fit and RMSEA values ⩽0.06 and SRMR values ⩽0.08 are suggestive of acceptable fit. Reference Kline31 Bootstrapping was applied with the generation of 95% bias-corrected bootstrap confidence intervals as an inferential test of the direct and indirect effects in all mediation analyses.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Maternal child maltreatment

Overall, 27.0% (n = 2536) of mothers were classed as having been maltreated during their childhood. In the whole sample, 6.2% (n = 586) of mothers reported sexual abuse, 7.1% (n = 665) reported physical abuse, 7.5% (n = 706) reported emotional abuse and 21.9% (n = 2058) reported neglect. Of the mothers who reported maltreatment, 62.0% (n = 1572) experienced one form of maltreatment, 22.4% (n = 569) experienced two forms of maltreatment, 10.8% (n = 275) experienced three forms of maltreatment and 4.7% (n = 120) experienced all forms of maltreatment.

Maternal depression

Measures of a mother's depression during pregnancy (antenatal depression) and across her child's first year of life (postnatal depression) were calculated. Mothers were rated as ‘depressed’ (⩾13) v. ‘non-depressed’ for both time periods: 18.1% (n = 1704) of mothers met the threshold for antenatal depression and 12.8% (n = 1205) of mothers met the threshold for postnatal depression. There was a high degree of association between antenatal and postnatal depression: mothers who were depressed during pregnancy were significantly more likely to be depressed during their child's first year of life, 40.2%, compared with mothers not depressed during pregnancy, 6.7% (OR = 9.3, 95% CI 8.2–10.7, χ2(1) = 1356.9, P<0.001, n = 9029). The mean EPDS score across pregnancy was 6.70 (s.d. = 4.4, n = 9160), and 5.61 (s.d. = 4.2, n = 9259) across the first year of life.

Maladaptive parenting

Indices of maladaptive parenting comprised daily use of maternal shouting (23.7%, n = 2185) and slapping (1.1%, n = 103), and maternal reports of frequent irritation (33.8%, n = 3111) and disagreement (50.4%, n = 4638) with her child. Indices were summed to generate a maladaptive parenting score ranging from 0 to 4 (mean 1.6, s.d. = 1.1, n = 9197).

Child maltreatment

Maltreatment was rated if a child was reported to have experienced any type of abuse, neglect or bullying: 39.0% (n = 3665) of children were classified as having experienced maltreatment. Indices of child maltreatment included physical abuse (13.4%, n = 1259), sexual abuse (0.5%, n = 49), emotional abuse (9.8%, n = 920) and bullying by peers (24.3%, n = 2286). A summed score of number of maltreatment types was also generated which ranged from 0 to 4 (mean 0.5, s.d. = 0.7, n = 9397). Of the children classed as having experienced maltreatment, 79.7% (n = 2922) experienced one form of maltreatment, 17.6% (n = 645) experienced two forms of maltreatment, 2.7% (n = 98) experienced three forms of maltreatment and 0.05% (n = 2) experienced all forms of maltreatment.

Child emotional and behavioural difficulties

Maternal ratings of child DSM-IV depressive disorder symptoms were summed at 10 (mean 0.3, s.d. = 1.0, n = 6207) and 13 years (mean 0.3, s.d. = 1.0, n = 5591). Mothers also reported on child internalising difficulties as defined by the SDQ at 11 years: emotional problems (mean 1.4, s.d. = 1.7, n = 6025) and peer problems (mean 1.0, s.d. = 1.5, n = 5791). Maternal ratings of child DSM-IV DBD (ADHD, conduct disorder, ODD) symptoms were summed at 10 (mean 5.6, s.d. = 8.4, n = 6599) and 13 years (mean 5.1, s.d. = 8.1, n = 6075). Mothers also reported on child externalising difficulties as defined by the SDQ at 11 years: conduct problems (mean 1.1, s.d. = 1.4, n = 5983) and hyperactivity problems (mean 2.7, s.d. = 2.2, n = 5981).

Group differences between maltreated and non-maltreated mothers

Group differences between mothers classed as maltreated v. non-maltreated were calculated. As presented in Table 2, analyses revealed that children of maltreated mothers had significantly greater emotional and behavioural difficulties at 10, 11 and 13 years, as evidenced by greater DSM-IV symptoms of depression (major depressive disorder, depression not otherwise specified) and DBDs (ADHD, conduct disorder, ODD), as well as greater emotional, peer, conduct and hyperactivity problems as captured by the SDQ. Significant positive associations were also observed between maternal child maltreatment and all four potential mediating variables: maternal antenatal depression, maternal postnatal depression, maladaptive parenting and child maltreatment. Furthermore, in comparison with non-maltreated mothers, mothers maltreated in childhood were significantly more likely to have a lower level of education, to have a psychiatric history, to drink and smoke more in pregnancy and to have lower social support.

Table 2 Group differences between mothers maltreated in childhood v. non-maltreated mothers

| Maternal child maltreatment | Group effect a | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NO (n = 6861) | Yes (n = 2536) | χ2(1) | z | |

| Maternal factors | ||||

| Post 16 years education, % | 61.3 | 58.7 | 5.2* | |

| Single, % | 47.1 | 49.1 | 2.3 | |

| Psychiatric history, % | 6.2 | 19.1 | 341.7** | |

| Antenatal depression, % | 14.6 | 29.4 | 260.4** | |

| Antenatal drinking, mean (s.d.) | 0.7 (0.8) | 0.8 (0.8) | 3.1** | |

| Antenatal smoking, mean (s.d.) | 1.6(4.4) | 2.6 (5.5) | 10.8** | |

| Postnatal depression, % | 9.7 | 22.0 | 244.9** | |

| Maladaptive parenting, mean (s.d.) | 1.1 (1.0) | 1.2 (1.0) | 5.4** | |

| Social support, mean (s.d.) | 21.6 (4.7) | 19.2 (5.5) | −17.7** | |

| Child factors | ||||

| Child maltreatment, % | 35.2 | 49.3 | 155.1** | |

| DSM-IV depression symptoms at 10 years, mean (s.d.) | 0.2 (0.9) | 0.4(1.2) | 6.0** | |

| DSM-IV DBD symptoms at 10 years, mean (s.d.) | 5.1 (7.7) | 7.2 (10.0) | 8.6** | |

| SDQ emotional problems, 11 years, mean (s.d.) | 1.3 (1.6) | 1.7 (1.8) | 7.1** | |

| SDQ peer problems at 11 years, mean (s.d.) | 0.9(1.4) | 1.3 (1.7) | 6.4** | |

| SDQ conduct problems at 11 years, mean (s.d.) | 1.1 (1.3) | 1.3 (1.5) | 6.0** | |

| SDQ hyperactivity problems at 11 years, mean (s.d.) | 2.6 (2.1) | 3.0 (2.3) | 4.7** | |

| DSM-IV depression symptoms at 13 years, mean (s.d.) | 0.2 (0.9) | 0.4(1.3) | 4.8** | |

| DSM-IV dbd symptoms at 13 years, mean (s.d.) | 4.7 (7.6) | 6.2 (9.2) | 6.1** | |

| Gender, % female | 49.0 | 47.3 | 2.1 | |

DBD, disruptive behaviour disorder; SDQ, Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire.

a. Group effects are based upon Pearson's χ2 test for independence for associations with two dichotomous variables and the Mann–Whitney test for associations with a dichotomous and continuous variable that did not permit parametric analyses.

* P<0.05,

** P<0.01.

Testing a measurement model of child psychopathology: confirmatory factor analysis

A two-fector confirmatory solution was specified in which DSM-IV symptoms of depression at 10 and at 13 years, and SDQ emotional and peer problems scales at 11 years, were entered as indicators of an ‘internalising’ latent factor, whereas DSM-IV symptoms of DBD at 10 and 13 years, and SDQ conduct and hyperactivity problems scales at 11 years, were entered as indicators of an ‘externalising’ latent factor. This two-fector solution demonstrated good model fit (CFI = 0.95, RMSEA = 0.066, 90% CI 0.61–0.70, SRMR = 0.041, χ2 M(19) = 628.4, P<0.01, n = 7416). Standardised factor loadings ranged from 0.37 to 0.61 for internalising, and from 0.61 to 0.86 for externalising.

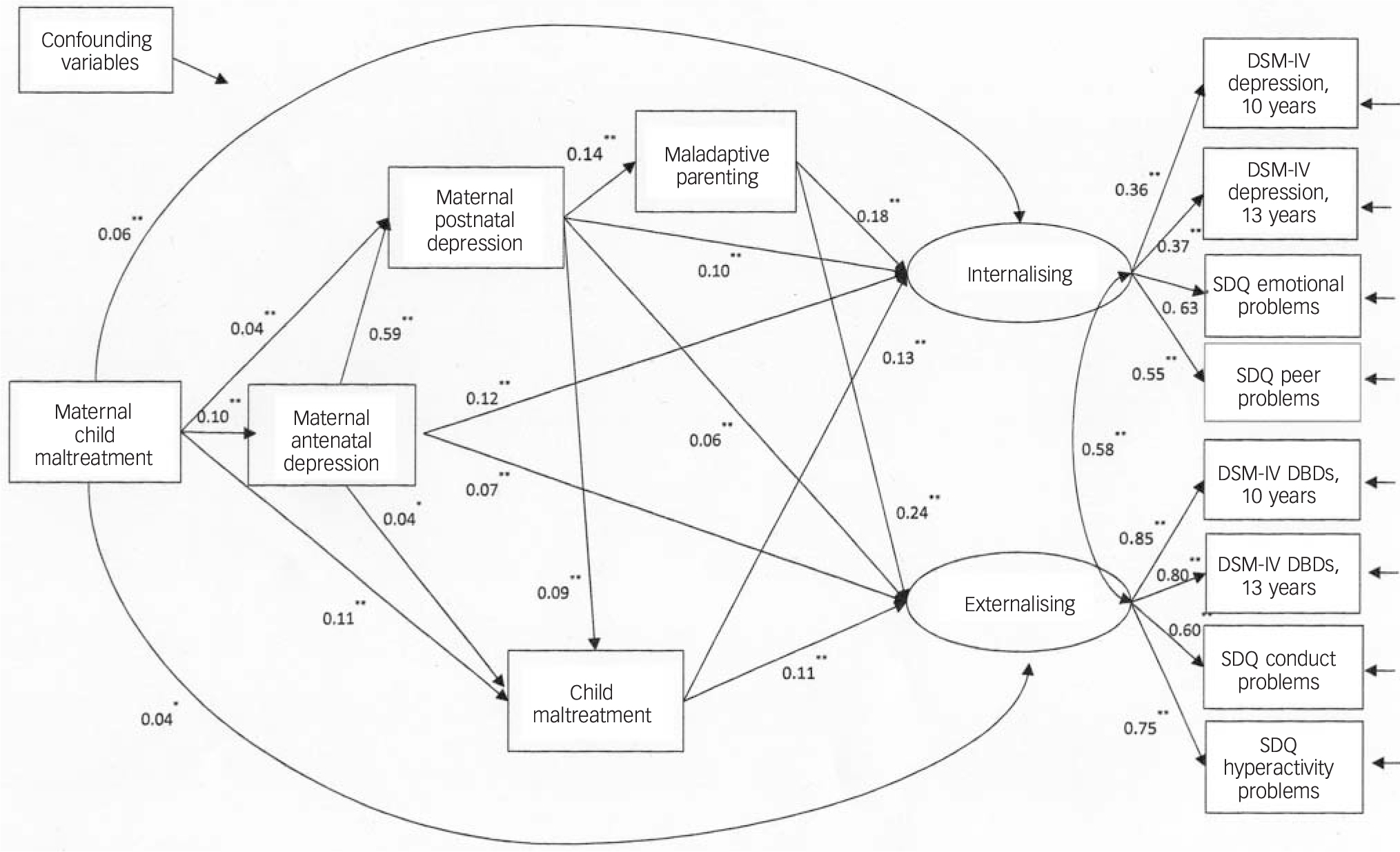

Testing mediating pathways: structural regression models

Maternal child maltreatment was entered as the predictor variable; internalising and externalising latent factors indicated by DSM-IV and SDQ symptoms and problems operated as the outcome variables; and maternal antenatal depression, maternal postnatal depression, maternal maladaptive parenting and child maltreatment were entered as mediator variables. Child internalising and externalising difficulties were regressed on maternal child maltreatment and all mediator variables. Maternal postnatal depression, maternal maladaptive parenting and child maltreatment were regressed on maternal antenatal depression. Additionally, maladaptive parenting and child maltreatment were regressed on maternal postnatal depression. Maternal education, partner status, psychiatric history, antenatal drinking and smoking, social support and child gender were entered as covariates. The model demonstrated good fit (CFI = 0.95, RMSEA = 0.037, 90% CI 0.035–0.039, SRMR = 0.025, χ2 M(94) = 1070.4, P<0.01, n = 7689). Path estimates (standardised regression coefficients (Ps)) are presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1 Structural regression model for the effect of maternal child maltreatment on child internalising and externalising difficulties mediated by maternal depression, maladaptive parenting and child maltreatment.

Presented estimates are beta coefficients, with only statistically significant paths shown. DBD, disruptive behaviour disorder; SDQ, Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire.

*P<0.05, **P<0.01.

Mediation analysis

There was evidence of significant mediation for both internalising (total indirect effect: β = 0.05, 95% bootstrap CI 0.04–0.05) and externalising difficulties (total indirect effect: β = 0.04, 95% bootstrap CI 0.03–0.04). Table 3 presents estimates of the specific indirect effects for each pathway. Analysis revealed that maternal child maltreatment significantly predicted child internalising difficulties directly (direct effect: β = 0.06, 95% bootstrap CI 0.03–0.08) and externalising difficulties directly (direct effect: β = 0.04, 95% bootstrap CI 0.006–0.07). The total effect of maternal child maltreatment on child internalising difficulties was β = 0.11 (95% bootstrap CI 0.08–0.13) and on externalising difficulties was β = 0.07 (95% bootstrap CI 0.03–0.11). As can be seen in Table 3, maternal antenatal depression, postnatal depression and child maltreatment, but not maladaptive parenting, were observed to mediate significantly the association between maternal child maltreatment and both internalising and externalising difficulties, in an independent manner. Maladaptive parenting only exerted an indirect effect when preceded by postnatal maternal depression. Notably, antenatal depression was observed to exert a mediated effect by directly increasing postnatal depression and child maltreatment. These data suggest that the timing of maternal depression is relevant, such that maternal antenatal depression increases the risk for child psychopathology through increasing the risk for not only postnatal depression, but also directly for child maltreatment.

Table 3 Specific indirect effects of maternal child maltreatment on child internalising and externalising difficulties via maternal antenatal depression, postnatal depression, maladaptive parenting and child maltreatment a

| internalising difficulties | Externalising difficulties | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | 95% CI | β | 95% CI | |

| Antenatal depression | 0.013 | 0.009 to 0.017 b | 0.009 | 0.005 to 0.012 b |

| Postnatal depression | 0.004 | 0.001 to 0.007 b | 0.002 | 0.001 to 0.004 b |

| Maladaptive parenting | 0.002 | −0.002 to 0.007 | 0.003 | −0.002 to 0.008 |

| Child maltreatment | 0.014 | 0.008 to 0.020 b | 0.012 | 0.009 to 0.016 b |

| Antenatal depression via postnatal depression | 0.006 | 0.003 to 0.009 b | 0.001 | 0.001 to 0.006 b |

| Antenatal depression via maladaptive parenting | 0.000 | 0.000 to 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.000 to 0.001 |

| Antenatal depression via child maltreatment | 0.001 | 0.0001 to 0.001 b | 0.001 | 0.0001 to 0.001 b |

| Postnatal depression via maladaptive parenting | 0.001 | 0.0001 to 0.002 b | 0.001 | 0.001 to 0.002 b |

| Postnatal depression via child maltreatment | 0.001 | 0.0001 to 0.001 b | 0.001 | 0.0001 to 0.001 b |

| Antenatal depression via postnatal depression via maladaptive parenting | 0.002 | 0.001 to 0.002 b | 0.002 | 0.001 to 0.003 b |

| Antenatal depression via postnatal depression via child maltreatment | 0.001 | 0.0001 to 0.001 b | 0.001 | 0.0001 to 0.001 b |

a. Presented estimates are beta coefficients.

b. Signifcant indirect effect (i.e. the 95% bias-corrected bootstrap confidence intervals do not cross zero).

Discussion

The present study used a 14-year longitudinal cohort design to investigate the impact of a mother's history of child maltreatment on her child's experience of internalising and externalising difficulties in preadolescence. The study reveals that maternal child maltreatment directly and indirectly predicts preadolescent internalising and externalising difficulties, while at the same time highlighting the crucial role of maternal depression during the antenatal period, which confers an increased risk of the children being exposed to maltreatment and developing psychopathology even in the absence of postnatal depression.

Independent mediating effects

Results indicated that maternal antenatal depression, postnatal depression and child maltreatment, but not maladaptive parenting, showed some level of independent mediation of the association between maternal child maltreatment and both internalising and externalising difficulties. These results corroborate existent findings in the literature that identify maternal psychological distress (regardless of timing) to be a key mechanism of vulnerability transmission from mother to child. Reference Myhre, Dyb, Wentzel-Larsen, Grogaard and Thoresen1,Reference Min, Singer, Minnes, Kim and Short3,Reference Collishaw, Dunn, O'Connor and Golding5–Reference Roberts, O'Connor, Dunn and Golding7,Reference Miranda, de la Osa, Granero and Ezpeleta10 In regard to existent mixed findings on the mediating effect of child maltreatment, Reference Plant, Barker, Waters, Pawlby and Pariante4,Reference Thompson6,Reference Miranda, de la Osa, Granero and Ezpeleta10 the current study shows that child maltreatment is indeed a specific mediating factor in the association between maternal child maltreated and child psychopathology.

The feet that maladaptive parenting practices were not observed to function as an independent mediator, but that they were observed to operate in serial mediation following postnatal depression, speaks to the literature detailing associations between maladaptive parenting and the other measured mediator variables, namely maternal depression and child maltreatment, Reference Lovejoy, Graczyk, O'Hare and Neuman32–Reference Lereya and Wolke34 and highlights issues of aggregation and confounding of risk when accounting for multiple associated risk factors. Given that maternal depression, maladaptive parenting and child maltreatment frequently co-occur, the present study's findings therefore highlight that the intergenerational transmission of vulnerability conferred by maladaptive parenting, as reported by previous research, Reference Rijlaarsdam, Stevens, Jansen, Ringoot, Jaddoe and Hofman2,Reference Collishaw, Dunn, O'Connor and Golding5–Reference Roberts, O'Connor, Dunn and Golding7 is likely better explained by the influence of maternal (postnatal) depression and child maltreatment, which is evident when these additional intergenerational risk factors are taken into account.

Timing of maternal depression

Findings relating to the indirect effects of maternal antenatal and postnatal depression were similar for both internalising and externalising disorders. The data indicate indirect effects of maternal child maltreatment on preadolescent psychopathology through maternal antenatal depression and child maltreatment, as well as through postnatal depression and child maltreatment and maladaptive parenting. This former finding suggests a specific vulnerability link between maternal depression during pregnancy and child maltreatment that is not necessarily explained by depression after birth – a finding that we first demonstrated in the South London Child Development Study. Reference Pawlby, Hay, Sharp, Waters and Pariante17,Reference Plant, Pariante, Sharp and Pawlby35 These data therefore highlight the putative role of maternal depression specifically during pregnancy in conferring risk for child vulnerability to psychopathology through directly increasing vulnerability as well as through increasing risk of exposure to further vulnerability factors such as child maltreatment and postnatal depression. Proposed explanations of this association between maternal antenatal depression and child maltreatment include a reduced capacity for care and a poorer mother–child attachment relationship, the influence of exposure to aggregated environmental risk factors and fetal programming of fetal brain changes leading to enhanced sensitivity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, which confer risk for emotional lability. Reference Talge, Neal and Glover36–Reference Feldman, Weller, Zagoory-Sharon and Levine40

Strengths and limitations

Although the study has several strengths, including investigation of mediation pathways using a 14-year longitudinal design of a very large community-based sample and the measurement of child psychopathology at the level of both clinical disorder and problem symptomatology, there are methodological issues that warrant consideration. First, measures of a mother's history of child maltreatment were made through self-report retrospectively using a non-validated scale, thereby increasing the likelihood of recall and measurement error, although recent research has reported good convergent validity between adult patients' self-reports of child maltreatment with clinical case notes and a psychometric self-report measure. Reference Fisher, Craig, Fearon, Morgan, Dazzan and Lappin41 Although the study benefited from a large sample size and thereby good levels of power to detect mediating effects over long time periods, using a non-experimental design has its drawbacks. Chiefly, natural aggregation of the occurrence of factors, such as maternal depression during pregnancy and after birth, cannot be prevented. Whereas advanced statistical procedures were applied to deal with issues of natural confounding and uneven group sizes, quasi-experimental designs that recruit groups based on the factor of interest would likely allow for greater control of error variance among the data. Other issues include the wide range of variance encompassed in factors such as maternal psychiatry history, as well as the feet that assessments of insults, such as maladaptive parenting, were measured at discrete intervals, which provides only a basic measure of perseveration.

Implications

Findings suggest a need for early identification of, and provision of support to, mothers with traumatic childhoods as a means to protecting their own and their children's psychological well-being. Specifically, interventions for expectant women with a maltreatment history and/or depression could include offering high-quality social support, improved access to psychological therapies, as well as parenting programmes aimed at promoting sensitive and warm caregiving practices. It is important that vulnerable women are identified as early as possible, such as during pregnancy when they routinely come into contact with healthcare services, and that support and interventions are offered on an ongoing and regular basis going forward. Future research would benefit from exploring cognitive vulnerabilities of affected children alongside affect regulation capacities as means to informing possible child-based intervention strategies.

Funding

The UK Medical Research Council and the Wellcome Trust (grant ref: ) and the University of Bristol provide core support for ALSPAC. The study was further supported by the Medical Research Council Project (grant no. ), the Psychiatry Research Trust, the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR)/Wellcome Trust King's Clinical Research Facility, the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and the Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology & Neuroscience, King's College London and Surrey and Borders Partnership NHS Foundation Trust.

Acknowledgements

We are extremely grateful to all the families who took part in this study, the midwives for their help in recruiting them, and the whole ALSPAC team, which includes interviewers, computer and laboratory technicians, clerical workers, research scientists, volunteers, managers, receptionists and nurses. We thank Dr Helen Fisher for her research consultation.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.