A. Introduction

The European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR or the Court) is the supreme judicial authority on the interpretation of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR or the Convention). The Court supervises forty-seven signatory states (member states) for compliance with their human rights obligations under the ECHR. Although the Court cannot invalidate the domestic laws of the member states, it does have the power to award monetary compensation for breaches of Convention rights and it can invite offending states to change their laws accordingly. The Court’s case law is also an important influence on domestic human rights and constitutional law in the member states.Footnote 1

Given the importance of this role, it is no surprise that various stakeholders care about the composition of the Court. Indeed, the Council of Europe has implemented a series of reforms over the last two decades in an effort to improve the quality of the candidates that are nominated by member states for election to the Court. Before 1998, when Protocol 11 created a permanent ECtHR, the first nominee on a list in order of the state’s preference was usually elected. Accordingly, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE)Footnote 2 effectively rubber-stamped the choice of the states. Since 1998, the PACE and the Committee of Ministers (CM) have changed their working methods significantly. According to the new procedures, candidates are to be placed in alphabetical order,Footnote 3 a standardized CV is used,Footnote 4 all candidates are interviewed,Footnote 5 and specific competences—for example, expertise in human rightsFootnote 6—are expected. Furthermore, in 2010, the CM established an Advisory Panel on the election of judges to ensure that candidates possess the requisite qualities. In 2015, a permanent committee within the PACE was created to provide further scrutiny of candidates for election.Footnote 7

These efforts have received mixed reviews from the member states and academic commentators.Footnote 8 The surrounding debate raises, but does not answer, several questions about how to evaluate the quality of candidate Strasbourg judges: How important is legal practice experience? Should specialized human rights knowledge be a prerequisite? Does a scholarly academic or judicial background contribute something particularly valuable for the Court’s work?

We argue in this Article that the debate about the quality of judges elected to the Court is in need of a significant reconceptualization. The impetus for this reconceptualization is a relatively obvious, but insufficiently appreciated, point: The ECtHR is a “they,” not an “it.” The Court exercises its judicial functions in collegial panels of three, seven, or seventeen judges, depending on the nature of the case. The selection of judges for Strasbourg should therefore be evaluated in terms of how individual judicial profiles contribute to the overall team roster from which the Court’s panels are constituted. We contend here that an evaluation of this kind should include attention to the professional diversity of the bench.

The Article is structured as follows. Sections B and C set the stage for our main argument by showing how an individualistic approach to judicial selection dominates both worldwide and at the Council of Europe. In Section D, we argue for an alternative approach that focuses instead on diversity in the overall composition of the bench, particularly in relation to professional diversity. We explain why and how this more holistic approach to judicial selection is applicable to the ECtHR. In Section E, we draw on original interviews with Strasbourg judges to investigate judicial self-understandings of what qualities or merits are desirable in a judge at the ECtHR. Consistent with our normative theory, the interview data suggest that the judges themselves value diversity of experience and perspectives above any single professional background. In Section F, we continue in an empirical vein, presenting and analyzing original data on the qualifications of every judge elected to the Court since 1998. We find that the system in place since 1998 has generally delivered a bench that is varied with respect to the judges’ career backgrounds, but this result is more a lucky accident than the result of deliberate design. Efforts to reform the election of judges to the ECtHR have generally been driven by an overly individualistic model of the “good” judge and our analysis suggests that this model may be having a worrisome homogenizing effect on the bench. In Section G, we conclude and offer suggestions for how future reforms might be shaped to protect and encourage professional diversity at the ECtHR.

B. Criteria for Judicial Office on Regional and International Tribunals

To situate our discussion of the ECtHR in comparative perspective, we begin by considering the criteria for holding judicial office on other regional and international tribunals. For this purpose, we reviewed the key statutory documents of thirty tribunals, including international tribunals of general jurisdiction,Footnote 9 courts of regional integration unions,Footnote 10 and courts specializing in human rights,Footnote 11 economic matters,Footnote 12 and criminal law.Footnote 13 Several generalizations and critical observations emerged.

First, it is common for the founding treaties of these tribunals to articulate a moral standard for holding judicial office. In many cases, “high moral character” is specifically required. This criterion is listed in treaties establishing fifteen tribunals.Footnote 14 In a similar vein, many of the foundational treaties demand that candidate judges for the associated tribunals are independent and impartial. For example, Article 20 of the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA) Treaty provides that the judges of the Court of Justice should be chosen from among persons of impartiality and independence.Footnote 15 Practically speaking, however, it is hard to see how criteria of this kind can do much work. Indeed, the Venice Commission has recently criticized national legislation of one of the Central Asian countries for using such vague and imprecise language in domestic legislation on judicial selection. The Commission stated that “[r]eference to ‘immoral behaviour’ is open to overbroad interpretation and should be avoided”Footnote 16 and references to morality were called “imprecise and therefore unsatisfactory from the standpoint of legal standards.”Footnote 17 In short, the problem with morality requirements is that they are so vague or so broad that almost anyone can satisfy them, except perhaps in extreme and obvious cases. Likewise, it is difficult to imagine how criteria such as integrity, impartiality, or independence can be reliably evaluated at the time of appointment.

Second, in all the treaties we reviewed, candidates for the relevant tribunals are required to have some qualification or experience. Some treaties envisage that a candidate could be a person appointable to high judicial office at the national level. Others make judicial experience a pre-condition for appointment. For example, a candidate judge for the Special Tribunal for Lebanon should have “extensive judicial experience.”Footnote 18 In other cases, the requirement for experience is more flexible. For instance, a candidate for a judicial position at the International Criminal Court should have “extensive experience in a professional legal capacity which is of relevance to the judicial work of the Court.”Footnote 19 Although a requirement of previous judicial experience is perhaps justifiable in the case of criminal tribunals, where some area-specific experience is crucial, it is arguably less so in relation to human rights courtsFootnote 20 or tribunals of general jurisdiction.Footnote 21

Third, many international tribunals require prospective judges to be recognized specialists in a particular area of law. For example, expertise in international law is required for the International Court of Justice;Footnote 22 established competence in criminal law or international law is required for the International Criminal Court;Footnote 23 and recognized competence in the field of the law of the sea is required for the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea.Footnote 24 Similarly, the founding documents of some regional human rights tribunals attempt to set a standard of specialized human rights competence. The Statute of the African Court of Justice and Human Rights, for example, stipulates that judges should be “of recognized competence and experience in international law and/or, human rights law.”Footnote 25 Likewise, the American Convention on Human Rights provides that judges should be “of recognized competence in the field of human rights.”Footnote 26 Interestingly, of the documents we reviewed, only the Agreement on the Status of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) Economic Court specifically requires candidates to have a university law degree.Footnote 27

Finally, a handful of instruments encourage the bench to be gender balanced. For instance, Article 36(8)(a)(iii) of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court requires the parties to aim for fair representation of female and male judges.Footnote 28 Similarly, Articles 5 and 6 of the Statute of the African Court of Justice and Human Rights require the state parties to take into account equitable gender representation in the nomination and election processes. The concern for gender balance appears to be a relatively new trend; it is not reflected in older treaties. More importantly, at least for our purposes here, gender balance is the only criterion for judicial selection on these international and regional tribunals that refers to the composition of the bench as a whole. Otherwise, the qualities of individual candidates, as opposed to the overall bench, are always the focus in the relevant treaties.

C. What Does the ECHR Require?

Although the Convention’s requirements for appointment to the ECtHR are broadly consistent with the patterns discussed above, they are notably on the more minimalistic end of the spectrum. Article 21 of the Convention stipulates only two necessary requirements for being a judge on the Strasbourg court: The judges should be 1) of “high moral character” and 2) either possess the qualification required for appointment to high judicial office or be jurisconsults of recognized competence. The PACE and the CM have developed interpretations of the Article 21 criteria, and the ECtHR has confirmed that they are competent to do so.Footnote 29 The documents of the CM and PACE should therefore be viewed as authorities on the required qualities for candidate judges.

That being said, the guidance that the CM and PACE provide is uneven. In some cases, CM and PACE interpretations do not add much in the way of clarity. For example, the CM’s guidelines on the selection of candidates for the post of judge at the ECtHR merely reiterate that the candidates “shall be of high moral character.”Footnote 30 Some additional explanation of the meaning of high moral quality is provided in the explanatory report to the Resolution 1366 (2004),Footnote 31 later endorsed by the PACE.Footnote 32 Therein, particular indicia of high moral quality are mentioned: “[C]ourtesy and humanity, commitment to public service, and conscientiousness and diligence.” These indicia seem sound, but they are not much more concrete than the underlying criterion that they aim to elaborate. Resolution 1366 (2004) adds a little more substance by highlighting the importance of judicial independence and judicial impartiality: “Candidates should undertake not to engage, if elected and for the duration of their term of office, in any activity incompatible with their independence or impartiality or with the demands of a full-time office.”Footnote 33 The difficulty here, as noted earlier, is that independence and impartiality are not readily testable criteria at the time of a judge’s election. Furthermore, even post-election, there would be disagreement around the margins concerning how to interpret these qualities. In effect, independence and impartiality are forward-looking and aspirational criteria.Footnote 34

Other qualities receive a more concrete treatment. For instance, the length and quality of professional experience is frequently discussed in the documents of the CM and PACE. The Guidance on the selection of candidates singles out practical legal experience as especially desirable and Recommendation 1649 (2004) requires that the candidates have experience in the field of human rights.Footnote 35 Although there is no fixed length of experience required, the PACE report endorsed the view of Nina Vajic, the former chairperson of the Advisory Panel for election of judges:

[R]egarding candidates who are judges or prosecutors, the level (usually at the highest courts) and the length of their experience shall be decisive; jurisconsults (Article 21) are assessed in light of the depth and width of their consulting experience, how well-known in their fields of expertise they are (including through relevant publications) and how they combine both academic and practical legal experience.Footnote 36

Legal expertise and competencies of the candidates also feature prominently in the CM and PACE documents. The Guidance on the selection of candidates states that “candidates need to have knowledge of the national legal system(s) and of public international law.”Footnote 37 The explanatory report to Resolution 1366 (2004) further states that the candidates should have “knowledge and awareness of European Convention jurisprudence, general legal knowledge, intellectual and analytical ability, maturity and soundness of judgement, decisiveness and authority, communication and listening skills.”Footnote 38 This list suggests that the Council of Europe prioritizes knowledge and practical skills over formal education.

Another more concrete criterion is that candidates “must, as an absolute minimum, be proficient in one official language of the Council of Europe (English or French) and should also possess at least a passive knowledge of the other, so as to be able to play a full part in the work of the Court.”Footnote 39 This is not a trivial matter; there is anecdotal evidence that some candidates have had no knowledge of one or even both official languages of the Court at the moment of selection.Footnote 40 This criterion illustrates the limitations of using CVs to evaluate candidates, as the candidates might overestimate their linguistic abilities and this cannot be spotted by simply examining the CVs. That said, at least language proficiency might be tested during interviews with the candidates.

The age of the candidates is also featured in the documents of the CM and PACE. The Guidance on the selection of candidates states that “[i]f elected, candidates should in general be able to hold office for at least half of the nine-year term before reaching 70 years of age.” This requirement effectively prevents candidates older than 65 from being considered. The ECHR is silent on the issue of the minimal age required for a judge. Accordingly, the Council of Europe decided not to strictly regulate this issue out of concern that to do so might prevent younger but deserving candidates from applying.Footnote 41

Finally, an imperative to promote gender balance on the bench is reflected in a number of regulations adopted by the PACE and the CM. This is the most concrete of all recommendations. The Guidance on the selection of candidates provides that “[l]ists of candidates should as a general rule contain at least one candidate of each sex, unless the sex of the candidates on the list is under-represented on the Court (under 40 per cent of judges) or if exceptional circumstances exist to derogate from this rule.”Footnote 42 Another mechanism for ensuring gender equality is provided for in Resolution 1366 (2004), which states that “in the case of equal merit, preference should be given to a candidate of the sex under-represented at the Court.”Footnote 43

In sum, the approach taken by PACE and CM to the qualifications and background of nominees is, with the exception of gender, a decidedly individualistic one: Candidate judges are to be evaluated on a candidate-by-candidate basis, without reference to the overall composition of the bench. In what follows, we argue that this predominantly individualistic approach to judicial selection, though typical of international and regional tribunals more generally, is suboptimal and we theorize a more holistic alternative.

D. Theorizing Judicial Selection for the ECtHR

The recent reforms in the system for electing judges to the ECtHR are consistent with what appears to be a general global trend toward greater attentiveness to merit or quality in judicial appointments. In the Unites States, for example, there was a proliferation of “merit-plan” judicial selection systems in the twentieth century: Twenty-four of the fifty states now rely on some form of merit selection as opposed to pure election or political appointment.Footnote 44 A similar but more sudden change took place across the United Kingdom during the 2000s, as judicial appointment commissions were created in England and Wales,Footnote 45 Northern Ireland,Footnote 46 and Scotland.Footnote 47 Replacing traditional “tap-on-the-shoulder” political appointment regimes, the judicial appointment commissions have statutory mandates to select judges solely on merit.Footnote 48 More generally, constitutionally enshrined judicial councils—independent bodies responsible for the selection and governance of the judiciary—have grown in popularity over the last thirty years around the world.Footnote 49 Typically, these bodies also have an explicit mandate to vet candidates for judicial office on the basis of merit.Footnote 50

A greater critical awareness of the quality of judges is reflected also in the academic literature. In the US, the study of merit-based judicial appointment, together with the peculiar American practice of judicial elections, is so well-established that it is practically a research field unto itself.Footnote 51 More recently, scholars in the United Kingdom have turned their attention to the social construction of merit and have shed critical light on how the concept may operate to reproduce privilege and impede the inclusion of women and ethnic minorities on the bench.Footnote 52 There is also a sizable literature now on judicial appointments at international and supranational courts. Most of this literature is normative in orientation, addressing the question of how judges ought to be selected for these courts.Footnote 53 In particular, scholars have been critical of the system for electing judges to the ECtHR because it allegedly fails to select for the most legally competent candidates.Footnote 54

Despite the focus on the quality of judicial appointments, policy makers and academics alike often pay insufficient attention to the fact that judges on courts of appellate or apex-level adjudication typically decide cases together as a panel. The fact of collegial decision-making has important consequences for how we should think about judicial selection in general. Ideally, a collegial decision is not simply the aggregate of individual preferences about a case’s outcome. If judges engage in good faith deliberation, the resultant decision has the potential to reflect a collective wisdom that is greater than the sum of its constituent parts.Footnote 55 This enhanced result depends on the assumption that each judge can make a distinct epistemic contribution. It is therefore implicit in this practice that judicial decisions are, to some extent, a team effort. Judges will bring a diversity of perspectives to the case before them and, in the exchange between those perspectives, the ultimate decision is enriched.

Although this deliberative scenario may sound optimistic, it is well-grounded in empirical evidence. Numerous quantitative studies support the prediction that, whenever judges decide cases as a panel, there is likely to be some kind of “panel effect”: The decision of each individual judge will not only be influenced by their own legal knowledge and preferences, but also by the knowledge and preferences of the other judges they sit with.Footnote 56 To be sure, the apparent effects are not always benign. For example, panel homogeneity has been found to amplify the influence of political ideology on judicial behavior; conservative judges tend to decide cases in a more conservative way when they sit on a panel with other conservatives, but tend to decide cases in a more liberal way when sitting on a panel with more liberal judges. Comparable effects are applicable to liberal judges.Footnote 57 Nonetheless, panel diversity—in terms of ideology, gender, or ethnic/racial background—does improve decisions by counteracting biases and making judges more sensitive to alternative or minority perspectives.Footnote 58 More extreme ideological tendencies tend to be dampened by a panel’s ideological diversity.Footnote 59 Similarly, the presence of female judges on a panel causes male judges to be more sympathetic to claimants in sex-discrimination cases.Footnote 60 And in constitutional cases challenging affirmative action, for instance, randomly assigning a black judge to sit with two nonblack judges on a three-judge panel “nearly ensures that the panel will vote in favour of an affirmative action program.”Footnote 61

There is no scholarly consensus on the causal mechanism underlying panel effects.Footnote 62 The most straightforward explanation—favored by some leading scholars in the field—is that judges actually gain important insight or information from listening to and deliberating with their colleagues in an exchange that can enhance judicial decision making.Footnote 63 But it might also be that the presence of diverse judges creates potential whistle blowers who deter colleagues from taking especially extreme positions.Footnote 64 In either case, there is good reason to think that panel diversity will have a positive influence; other things being equal, a bench with a variety of different perspectives is probably better than a relatively homogenous, single-minded bench.Footnote 65

In addition to gender, one obvious potential source of valuable diversity for a court is the professional background of judges.Footnote 66 Different career paths will equip judges with different experiences and associated skills, knowledge, and perspectives, and these attributes will potentially enrich judicial decisions. There is substantial empirical evidence to support this prediction. Quantitative studies suggest that the professional background of judges influences judicial decisions across a broad range of domains, including criminal cases,Footnote 67 labor disputes,Footnote 68 racial discrimination,Footnote 69 and tax,Footnote 70 and in the propensity of judges to author dissenting opinions.Footnote 71 This body of evidence is mostly from the US context, but professional background has also been found to have a significant influence on judicial decision making on the ECtHR, specifically with respect to the judges’ varying inclinations toward relatively more activist—or more restrained—approaches to Convention rights.Footnote 72

Though often neglected, the importance of professional diversity in judicial selection has not been entirely lost on policy makers. President Barack Obama prioritized improving professional diversity in nominating judges to the US federal courts, succeeding in broadening the bench to some extent during his presidency.Footnote 73 In the United Kingdom, the Judicial Appointments Commission not only monitors and reports statistics on the career background of candidates for judicial office—alongside gender and ethnicity—but it also takes active steps to encourage candidates from underrepresented professional backgrounds to apply for judicial office.Footnote 74

In sum, an appreciation of how professional diversity and associated panel effects influence and potentially enrich judicial decision making should and can inform how we think about judicial quality and how to select for it. Where judges decide cases together, the proper unit of analysis is not the individual judge, but the bench from which the panels are constituted. Thus, the right question to ask is not: “Who is the ideal judge for adjudicating these cases?” Rather, the question is: “What is the ideal composition of the bench, such that the panel’s adjudication will benefit from an appropriately diverse range of knowledge, experiences, and perspectives?”

The ideal professional mix will depend on the specific context and jurisdiction of a given court. Some professional backgrounds will inevitably be less relevant—or totally irrelevant—depending on the context. In the case of the ECtHR, we think a healthy mix of professional backgrounds is one that will reflect the following three stylized ideal types: (1) The Technician; (2) the Philosopher; and (3) the Diplomat.Footnote 75

The case for the Technician is relatively straightforward. The ECtHR deals with complex legal questions that engage general principles of public international law and international human rights law, the Court’s own case law, as well as the law of forty-seven member states. Fluent knowledge of at least some of these areas is needed and this is what the Technician brings to the job. Judges that are especially likely to approximate this profile would include career judges, especially those with experience at the apex level of constitutional adjudication in their home jurisdiction or prior experience on another supranational court. Seasoned practitioners in human rights law might also approximate the Technician ideal-type profile.

But a knowledgeable court is not necessarily fit-for-purpose. The ECtHR’s cases cannot always be resolved simply by a formal analysis of the text of the Convention or a review of precedent. Human rights are often expressed in abstract and morally-loaded language and the resultant claims raise profound questions about the legitimacy of state power and the autonomy or dignity of human beings. Fundamental disagreements about the role and extent of human rights abound and are probably inevitable.Footnote 76 What is more, these questions arise in the diverse and ever-changing social environment of the forty-seven member states. Thus, the ECtHR developed the “living instrument” approach that treats the Convention as an evolving source of law to keep pace with changing circumstances and understandings.Footnote 77 Although only used in hard cases, evolutive interpretation requires more than just a technical application of rules that were previously developed by the ECtHR.

To grapple with these challenging aspects of human rights law, the Philosopher profile is needed. Taking inspiration from Ronald Dworkin’s ideal “Judge Hercules,” the Philosopher seeks to develop a deep theoretical understanding of human rights; each particular human rights norm is to be interpreted according to a moral theory that best justifies it as part of a coherent scheme of principles, taking into account the record of previous interpretations.Footnote 78 No particular career background has a monopoly on philosophical reflection, but we would submit that some backgrounds—particularly academic careers—are more likely to produce Philosopher judges. This ideal type will be best represented by judges who are well-versed in the intellectual history and philosophy of human rights and so it probably implies a doctorate-level education.

As admirable as the Philosopher might sound, she too has her limitations. Like all courts, the ECtHR only has as much authority as the relevant governments are prepared to tolerate.Footnote 79 Without the power of “the sword or purse,”Footnote 80 courts must mostly rely on governments to implement their decisions. Indeed, the authority of the ECtHR is especially tenuous. It stands outside the national systems it judges. It cannot interface directly with any municipal apparatus of enforcement—for example, police and public prosecutors—and cannot order punitive sanctions against member states for defying its judgments. Nor can the ECtHR draw on any sort of patriotism to legitimate itself, as a national high court might. Instead, the reach and legitimacy of the ECtHR is always mediated through the member state governments, themselves the subjects of its rulings. The Court must be mindful of how the various member states are likely to react to its decisions.Footnote 81 Compliance cannot be taken for granted. Furthermore, as many scholars of judicial politics have argued, conspicuous episodes of noncompliance may erode a court’s authority more generally by making subsequent episodes of noncompliance more likely.Footnote 82

Neither the Philosopher nor the Technician is particularly alert to these strategic considerations. This is where the Diplomat comes in.Footnote 83 The Diplomat knows the political context surrounding the disputes that come before the ECtHR. She has a rough but reliable sense of how far the Court can assert itself against the preferences of the member state governments before defiance becomes probable. She has a sense of what public opinion will accept in each member state. A Diplomat judge may well be literally a former diplomat, i.e., someone with experience representing her own country in international fora and negotiating with counterpart representatives from other countries.Footnote 84 Working within government or international organizations might also engender this sort of sensibility.

No actual real-life judge will perfectly conform to any of these three ideal types. What is more, professional background should not be understood as having a deterministic effect: A former judge or a former law professor might very well approximate the Diplomat, while a former government agent at the ECtHR might come to approximate the Philosopher more than any of the other ideal types. Our point, rather, is probabilistic in nature: Individual judges will tend to lean in one of these directions, partly because of career experience. Consequently, a court might be relatively homogenous, in the sense that it is composed entirely of judges with the same sort of disposition. This would be an impoverished bench. The best recipe for a bench that includes judges approximating each of these ideal types is professional diversity; a good mix of judges from different career paths will allow the Court to draw from the strengths of each, while preventing any one type from dominating.

E. Views from the Bench

So far, we have been considering judicial selection in relatively abstract terms. We now turn to consider what the Strasbourg judges themselves think are the desirable or necessary criteria for electing their would-be colleagues. Sixteen sitting judges of the Court were interviewed for this project (i.e., thirty-four percent of the forty-seven sitting judges of the full Court). The method of semi-structured interviews was used, allowing for some flexibility during the interviews. All interviewees were asked to explain what they understand to be the traits of an ideal ECtHR judge. In response, some judges admitted that they consciously or subconsciously described themselves.Footnote 85 It was difficult to mitigate this problem completely, but additional questions were asked if this kind of bias was obvious. We canvass the main themes that emerged from these interviews below.

I. Character and Personality

The first of the themes to emerge relates to matters of character or personality. As we noted above, the Convention requires the judges to be people of “high moral quality.” Nevertheless, the interviewed judges did not place much emphasis on morality, and this seemed to reflect a practical understanding that this criterion is too difficult to evaluate. Judge 6, for example, opined that we should “leave moral character aside because this is something that is difficult to assess in many cases except for some extreme instances.”Footnote 86 To be sure, a few judges said that an ideal judge should have some general characteristics of a good person. Judge 7 pointed out that “first of all this person has to be a good human being. We should not forget that we are all humans and we have to be human beings. And then ethical issues are important, moral, ethical values and the feeling of justice.”Footnote 87 Judge 10 explained that good judges should have “moral qualities, so that one can put a certain trust in them for deciding cases. The citizens do not know who the judges are but ideally a judge should be a person who is working consciously and who has the characteristics that apply to any judge.”Footnote 88 Judge 9 identified work ethic and optimism as being particularly important character traits: “It is a lot of work. You need to be optimistic, as you will find a difficult human rights situation in some countries. You can only change so much. If you wanted to change much more, you would get frustrated, and you would dislike the job after two years.”Footnote 89

With respect to judicial independence and impartiality, all the judges agreed that these qualities are absolute preconditions for election to the ECtHR. Judge 14, for instance, said that “independence is a crucial personal characteristic”Footnote 90 of a judge. Likewise, Judge 7 said that independence should be “self-evident.”Footnote 91 Nevertheless, the judges expressed different views as to how aloof the Court should be from the political context and consequences of decisions. Judge 15 explained the issue in the following terms:

This court is divided based on legal and philosophical principles, even political principles. Some judges can be called human rights fundamentalists, they do not only see human rights violation everywhere . . . [they] extend certain articles, Article 8 for example, to the language that it is not there. It goes over some limits and generates very sharp criticism of the Court. On the other side, there are a lot of lawyers who say that we have to be realistic that we have to connect our practice to the people, to the governments elected by the people. I consider these [people] not politically conservative but positivists in favour of restrictive interpretation.Footnote 92

Judge 5 went a step further and suggested that judicial independence was compatible with an explicitly realist sensibility:

[I]t is extremely important that you . . . have an independent judicial outlook. The Court is an extremely political institution. Why is it political — because of the nature of the conflicts. So, yes, we are judges; yes, we are dealing with cases as judges, but at the European Court of Human Rights you cannot be politically naïve. You need to understand the geopolitical consequences of what you are doing and you need to understand when you need to be strong on principle, when you are the last safeguard of a meaningful European Public Order and you have to enforce it and you have to do it independently, not being afraid of consequences. But also there are cases in which you need to know when to pick your battles, when [to] allow things to percolate domestically, so you have the maximum impact on the cases that really matter. If you are always in an ivory tower, if you always want to create the best possible outcome it will slowly erode trust.Footnote 93

In contrast, Judge 9 likened judicial independence and impartiality to the virtue of courage: “You need to be independent towards your national state, you need to be independent towards your colleagues in the Chamber, but also in the Grand Chamber. You need to have the courage to think: What do I have . . . to decide in the name of human rights?”Footnote 94

Judge 10 was the only judge to explicitly say that the personal political ideology of candidates for election to the ECtHR should be taken into account:

[T]he PACE could pay attention to the political and social views of the candidates. I do not know whether or to what extent they are doing it and I do not know whether they are doing it in a good way, but for me it would be legitimate for the Parliamentary Assembly to pay attention to such views. If the Parliamentary Assembly is sending a progressive or a conservative person to the Court, it should be aware of this person’s tendencies. And it should then be for the Assembly to make a choice. But again, these are concerns for the policy makers, for those who elect, and not for the judges themselves.Footnote 95

Interestingly, especially for our purposes here, there was broad agreement among the interviewees about the importance of collegiality as a personal character trait. For example, Judge 16 said:

It is very important to understand that this is a collegiate system, that you are prepared to work with colleagues for the institution and not simply for your personal interest, moving your personal career. For me it is absolutely critical that you do not place your personal interest above all.Footnote 96

Similarly, according to Judge 5, an ideal judge is a person “who has a reasonable attitude towards the law and his colleagues, a person who has an open mind. A person who does not have very strong instinctive reactions to judicial disputes. A person who has good social skills that can easily work in a multi-member composition.”Footnote 97 Judge 1 echoed this sentiment, saying that “the judge should be really open to listen. If we have only people who are absolutely convinced of the rightness of their belief then we would not have the best possible solution . . . .”Footnote 98 Judge 11 made the same point: “We are all different, and this is our strength. However, our strength is that we are taking collective decisions. The ability to take collective decisions and be able to listen to each other are very important.”Footnote 99 Judge 7 further explained the importance of being a good team player in the context of a multi-member panel:

If you want to be a judge here, you need to see a bigger picture and see what the impact of my court’s judgment is. Then you need to be collegiate. It is very important that you have this feeling of collegiality. Of course, it is good that judges bring their experiences with them here and they do not need to forget their experiences and knowledge, but they have a different hat now and they need to have this European hat now. They have to play a team game; it is a team game.Footnote 100

II. Knowledge and Skills

The second set of issues that emerged from the interviews relates to knowledge and skills. On the issue of the language requirements, the judges shared some important personal observations. Judge 1 maintained that:

There are obvious qualities like linguistic skills because otherwise the life is quite difficult for them and for the court. It is a trivial consideration, but it is an important one. All sections are bilingual and there are cases in which you have only English text which is in majority of cases but there are 35–40 percent of drafts which are only in French. As you can imagine the problem here is more with French than with English, but this is an important requirement.Footnote 101

Judge 10, however, suggested that knowledge of English and French, though important requirements, have the effect of excluding “some good people from becoming judges.”Footnote 102 Judge 12 pointed out that:

Speaking languages is good, but this aspect should not be overrated. There are judges who speak several languages fluently, including French, which sometimes appears to be a stumbling stone for a number of other judges (including myself). However, good knowledge of French does not, in and of itself, guarantee . . . the quality of the decision, nor the quality of the judicial reasoning substantiating that decision.Footnote 103

There was a range of responses on the importance of legal knowledge and skills. According to Judge 1, an ideal judge is someone who has “recognized authority, not necessarily an authority on Convention law, but someone who is recognized as an excellent lawyer.”Footnote 104 Indeed, the judges generally valued practical skills and expertise over and above formal education.Footnote 105 There was no clear consensus, however, among the interviewees as to what sort of skills or expertise are most valuable. Some judges focused on good lawyering skills; other judges emphasized expertise in particular areas of law. Judge 7 emphasized that in order to be a good ECHR judge “you should be very competent, you need to be an excellent lawyer. You need to be involved in your national law and also in European law.”Footnote 106

Interestingly, there was disagreement as to how important specialized knowledge of human rights is for the Court. Judge 15 emphasized the importance of particular domains of knowledge:

In my view in the courts the knowledge of human rights and public law is important as a base, as well as knowledge of political science and international law. This is so because I think that it is difficult to learn a field even if somebody was a good criminal or civil lawyer. If somebody was simply a criminal lawyer, I can see how the case lawyersFootnote 107 can cheat him as a single judge. They can put in the rubbish to be thrown out gigantic human rights violations which the judge does not realise if he is concentrating on criminal cases. Therefore, I think that certain human rights, political science, maybe international law would be necessary.Footnote 108

But Judge 16 expressed a contrasting view:

Human Rights is not rocket science. Most people would consider it as rather easy branch of law. I would much rather have someone who understands what it is to be a judge and who has a keen legal brain and also some political judgement as it is necessary rather than human rights activist because this is not what judges are being asked to do. This is one of the great mistakes that is always made that this institution is seen as an NGO whereas what it is doing in principle is applying the law. And it is applying the human rights law as it is defined by the Convention and the Court’s case law. Human Rights activism in itself I would say and at some point the PACE expressly recommended that the candidates should have human rights experience—that to my mind is not what we are looking for here.Footnote 109

Judge 10, although affirming that knowledge of the Convention was desirable, added that “it is more important to be a good lawyer than to be a Convention lawyer. If the candidate also knows the Convention, that is a plus.”Footnote 110 Similarly, Judge 12 warned against prioritizing legal knowledge above all qualities, stressing instead that personality and practical experience might be more important in some cases:

Because when you have someone who knows legal principles very well and is a great defender of human rights he or she as a judge might not necessarily understand the difficulties that the state can encounter. It is very easy to sit in this ivory tower and say please do this way or please do that way. And then say—you did not think of other tools or measures. And what are those other tolls and measures is nowhere specified . . . Very often the Court is right by finding against the state but sometimes—and this is very personality dependent, experience dependent—the Court should take into account the problems that the state encounters in a specific factual situation.

A “general knowledge of society” was also viewed as important for the work of the ECtHR.Footnote 111 Judge 4 elaborated on this idea, linking it with knowledge of literature, sociology, and political science:

Literature precisely gives you an understanding of how the society is functioning and how human beings are functioning. It is very, very important. It is also important to know a little bit what is necessary for a society to develop, so, one needs some basic knowledge of sociology and political sciences—those sciences that study society and human beings. And the combination of this knowledge makes a judge, if not perfect (we do not live in the ideal world) but at least a good judge.Footnote 112

Judge 13 also highlighted the imperative that judges elected to the Court are culturally sophisticated: “The most important thing is to have a very good general culture which is not really taken into account. This would give the judge cosmopolitanism to understand other cultures.”Footnote 113

III. Professional Experience

The third and final theme that emerged from the interviews was professional experience. A few of the judges expressed a preference for judicial experience, favoring a more streamlined bench composed of mostly former judges. Judge 12 pointed out that “[i]n general, it is very important that the majority of the Court are with some judicial experience.”Footnote 114

Judge 16 expressed a similar sentiment:

You need people who sat as judges, who understand what judicial process is, who understand what the work of a judge at senior level is, have experience of weighing up competing interests. This is something which is completely different to the work of an academic . . . It is always going to be a much bigger transition for practicing lawyers and academics than it is for people who have already sat as judges.Footnote 115

Judge 6 reflected on how an absence of judicial experience can be a hinderance:

I know instances of judges who, as soon as they arrived at the Court, asked either the registrar or the president: “The first thing that I need to know is, what do you do as a judge? How do you become a judge? How do you behave as a judge? How do you judge?” They had never sat in a court, had never sat in a tribunal. They had no idea.Footnote 116

Judge 10 went one step further, hypothesizing that the authoritativeness of the Court’s rulings would increase if there were more career judges on the bench:

I would like to refer to the situation under the old Court, a lot of judges were retired judges or sitting judges, or retired professors, who all had high prestige. Which meant that after they handed down the judgment in Strasbourg they returned to their country and they said to their colleagues: listen, we decided this. And when that was said by the prosecutor general or by the president of the supreme court, then the national judges would normally follow it. This is inevitably missing now because none of us is actually sitting in the national court and the distance with the national judiciary is also much bigger. The Parliamentary Assembly can make the distance a little bit smaller by recruiting from the judiciary.Footnote 117

Judge 8 expressed a more ecumenical view: “It is important that you have your feet on the ground and have this practical background against which you test your own ideas.”Footnote 118

Most judges viewed academic career background as less important, though some judges did indicate that it was beneficial. Answering the question as to whether academic or judicial background is more preferable at the Court, Judge 15 said:

For me obviously academic. I say that some judicial background is very good but also the academic background. Although I do not see my work at this court as a substitute for academic work. So, I do not like these dissents that are full of quotations, hundreds [of] pages long. For me it is very strange—I can write it in my academic life if I want it. I do not need to use dissenting opinions as self-exhibition.Footnote 119

Notwithstanding comments that singled out judicial experience as particularly valuable, the majority of judges agreed that the Court benefits from a mixture of professional backgrounds. Judge 1 explained:

We have different professional backgrounds—there are colleagues who are academics, there are colleagues who are professional judges, there are judges who are former practicing lawyers. For me it is important to have a good mix of all relevant professional backgrounds of legal professions. We need the creative and speculative capacity of academics and we also need the practical approach of practitioners—judges and lawyers. They are more oriented towards finding solutions.Footnote 120

Judge 3 agreed that having a range of backgrounds on the bench is “extremely useful in order to arrive to something which is balanced, to solutions which are ripe for time.”Footnote 121 Judge 4 pointed out that “academics can show the destination and those who have practical experience can find the way of how to reach this destination.”Footnote 122 Judge 9 emphasized the value of both professional backgrounds on the bench: “Professors have the disadvantage to see, in each and every case, a human rights violation. The first strategy of those with judicial background is to get rid of the case. If you have both types of judges, it is a very good mixture.”Footnote 123

Interestingly, the judges expressed appreciation for other kinds of diversity as well. Although the practice of electing some particularly young judges has sometimes been criticized, the interviewed judges did not see relative youth as a real problem. Judge 1 explained:

We have judges who are elected when they are very young. These colleagues bring the freshness of youth and sometimes the vision of a younger person is necessary for us. Most judges, including me, are in the category of mature people. Of course, we are experienced but at the same time maybe we rely too much on our experience and sometimes a fresh view is useful to allow us to spot something that we do not see exactly because we are accustomed to a certain way of doing things. Sometimes you need [a] fresh view.Footnote 124

Judge 2 also shared a preference for a “good mixture”Footnote 125 when it comes to age, while Judge 9 said the voice of younger people should be heard at the Court, pointing out that “younger people would look at some questions differently than older people. Why should they not sit on this Court and raise their voice?”Footnote 126

Gender diversity was not emphasized to the same extent. Apparently, the judges have rarely discussed this issue. Judge 9 pointed out that “you cannot say that women are better judges than men.” Nevertheless, Judge 9 was very much in favor of diverse backgrounds on the bench and maintained that in a court of forty-seven members, the “society should be well represented. You should have women, you should have women with children, you should have men with children.”Footnote 127

Judge 14 explicitly made the link between diversity and collegial decision making:

From the institutional perspective, there is enough academic research saying that our experiences and our views, our backgrounds, feed into the decisions that we make . . . This is who we are and how we think. For that reason, having a diversity on the Court because it is a collegiate body—in terms of basic characteristics—professional, gender . . . Gender balance is an important thing.Footnote 128

Indeed, Judge 14 went on to suggest that the value of diversity is implicit in the design of the Court and is important for legitimacy:

When you are asking—what is a good judge. Not one person could be that. If that could be one person that we would not need 17. That is the whole point of being 17 of us because it takes different perspectives, different experiences, different knowledge and then reaching a decision on that. This is a big part of the legitimacy of the judicial power.

Naturally, the views expressed by the judges about their own court are not objective or infallible perspectives; the judges may, at least in some respects, misapprehend how different professional backgrounds affect their decisions. Furthermore, as was noted earlier, the judges may be strongly biased in favor of their own backgrounds or may support profiles that are familiar to them over those that are less common.

All of that being said, it is striking just how consistent the judges are in affirming both the value of collegiality and the view that professional diversity can enhance the quality of the Court’s deliberations. Indeed, the quotes from Judge 14 above express the gist of the theory we espoused earlier. It is also notable that several of the judges volunteered comments on the political aspects of their work, one of them even noting the need for strategic sensitivity to “geopolitical consequences” so as to maximize the Court’s influence “on the cases that really matter.”Footnote 129 It seems then that, in addition to acknowledging the important roles played by practical legal experience—the Technocrat—and more elevated academic perspectives—the Philosopher—some judges also acknowledge a role for realpolitik—i.e., the Diplomat. In sum, the interviews suggest that those who have first-hand experience on the ECtHR tend to agree that professional diversity is a valuable asset for their bench.

F. Evaluating Professional Diversity on the Strasbourg Bench

How, then, does the ECtHR bench actually fare with respect to professional diversity? To answer this question, we collected biographical data on all judges appointed to the Court since 1998. In most cases, standardized CVs were publicly available online. Some CVs were kindly supplied by the Council of Europe staff. In a few instances, other publicly accessible biographical material was used to fill in the gaps.

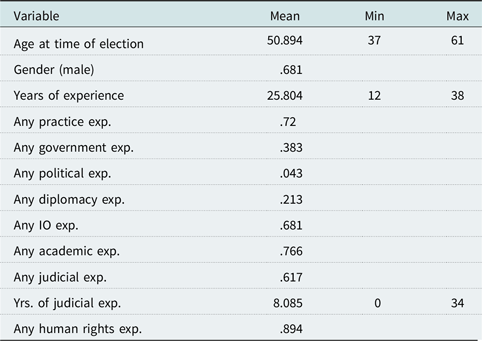

Table 1 summarizes statistics for the current Court for the variables we collected data on. These statistics are based on observations of the full population of the forty-seven judges as of the end of 2018. The mean, minimum, and maximum values are displayed for the continuous variables: Age at time of election, Years of pre-election experience, and Years of prior judicial experience. The remaining variables are qualitative or categorical and are coded “1” if the judge belongs to the category and “0” if not. Consequently, reported means for these variables should be interpreted as the percentage of the population having the quality or belonging to the category of interest. The professional experience categories were coded according to the following scheme:

1. Practice—this includes both private and public work as a lawyer, advocate, or, in the case of the ECHR, an “agent”;

2. Government—this refers to bureaucratic positions, as opposed to judicial, legal, or political positions;

3. Political—this category is for experience in legislative or executive political office;

4. Diplomacy—this is for experience representing a member state as an ambassador or in some international forum;

5. NGO—this category refers to experience in non-governmental organizations;

6. IO—this category refers to experience working for international or supra-governmental organizations;

7. Academic—this includes university teaching and/or research positions, but excludes ad hoc guest lectures;

8. Judicial—this category is for experience as judge of a court of some kind, but excludes private arbitration.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics on the Strasbourg Bench (as of the end of 2018)

These raw numbers show that professional experience on the bench is varied, but they do not tell the full story. Although many of the judges in our dataset have had experience spanning several areas, typically only small fractions of that experience are in areas outside of their dominant career background. Ultimately, we think it is the predominant career of each judge that will tend to be the most important feature of a judge’s professional background; it is this career experience that would seem most likely to shape a judge’s perspective in ways that approximate one of the ideal-type profiles outlined earlier. For this reason, we categorize the judges according to the professional area in which they spent the bulk of their pre-election career. To do this, we use the same categories and coding scheme as was outlined above but we include an additional category—“mixed”—for those judges whose careers have been so varied that there is no clearly predominant professional background.

Figure 1 charts the proportion of judges who belong to each of the main career categories. Legal practice careers are reasonably represented, accounting for 19.5 percent of the judges’ backgrounds. A sizeable proportion of the judges come from what we have categorized as a mixed career background—that is, their career was spread across several professional fields, with no predominant concentration in any one. Nevertheless, the most well-represented backgrounds, by a comfortable margin, are judicial and academic careers. Each of these accounts for about thirty-two percent of the judges—together accounting for about sixty-four percent of the current bench. A much smaller proportion come from government careers. None of the 2018 Court come from predominantly political or diplomatic career backgrounds.

Figure 1. Main Career Backgrounds of ECtHR Judges (2018).

It is probably good for the Court that much of the bench are former career judges; intuitively, this is the background that is most relevant to the job and the interview material we presented earlier support this intuition. Furthermore, the consequences of this for the Court’s decision-making tendencies are also probably relatively benign. The discussion surrounding judicial elections often boils down to expectations about who is going to be more state-friendly on the bench, and empirical research shows that are indeed at least some predictable tendencies. According to measures of the ECtHR developed by Erik Voeten, career backgrounds engender significantly different approaches to adjudication.Footnote 130 In contrast to previous private practice careers, which are strongly associated with subsequent judicial “activism” at the ECtHR—presumably because this background encourages an applicant-centered perspective on human rights disputesFootnote 131—prior judicial experience is associated with a slight tendency of judicial restraint.Footnote 132

The high proportion of judges coming from academic careers—especially relative to those with backgrounds in government, international organizations, and diplomacy—is more striking. One might plausibly worry that this imbalance would incline the Court to an overly idealistic “ivory-tower” approach to the Convention, privileging the Philosopher ideal-type while underrepresenting the more realist Diplomat ideal-type. There are some reasons, however, to think that this concern, though perhaps plausible in the abstract, might be misguided. Mikael Rask Madsen suggests that it was precisely the prevalence of a “legal-political elite of law professors” on the early bench—as opposed to judges from more technical backgrounds—that allowed the Court to appreciate and strategically navigate the structural challenges faced by key member states.Footnote 133 Moreover, according to Voeten’s measures, academic judges are not especially “activist” in their orientation relative to other career backgrounds.Footnote 134 Voeten’s data may be out-of-date—the data include only judges appointed before 2007—but there is no reason to think that career academics have become more “ivory tower” in the interim.

All of that being said, there may well be a more compelling cause for concern when it comes to the trajectory of professional backgrounds on the ECtHR. Figure 2 shows how the percentage of career profiles elected to the bench has changed since 1998, grouping the elections into four batches: (1) The initial thirty-five elections of new judges in 1998; (2) thirty-five elections from 1999 through 2009; (3) twenty-four elections following the 2010 reforms, but before the 2015 reforms; and (4) twenty-three elections following the 2015 reforms and through to the end of 2018.

Figure 2. Changes in Judges’ Main Career Background since 1998.

The graph tells three important stories. First, the proportion of career academics elected to the bench since 1998 has consistently been high. With the exception of the five-year period following the 2010 reforms, over thirty percent of elected judges have come from predominantly academic careers. Second, the proportion of judges elected with mixed career backgrounds—though fluctuating—has trended downwards over time. Third, the proportion of career judges elected to the bench has been trending upwards since 1998.

The trend favoring judicial backgrounds is even more evident in Figure 3, which charts the elected judges’ years of judicial experience as a fraction of their total pre-election experience. The graph shows a clear and quite dramatic shift towards judges with more judicial experience.

Figure 3. Changes in Prior Judicial Experience Since 1998.

The causal explanation for these changes is beyond the scope of the present discussion. It may simply be that some member states—particularly the newer Eastern and Central European constitutional democracies—now have a greater number of judges with experience in adjudicating human rights to draw from and so the pool of nominees has changed accordingly. It may also be that the 2010 reforms have tended to benefit career judges more than other backgrounds—Figure 3 certainly suggests as much. In any case, it is clear that changes in election patterns, particularly over the last ten years, have favored those candidates with relatively more judicial experience.

Some may see these changes as cause for celebration. Indeed, media and political elites have sometimes complained of a dearth of “real” judges on the Court. For instance, in 2015, Philip Davies MP said in UK Parliament that the ECtHR “is no more than a joke. It is full of judges, many of whom are not even legally qualified—they are not actually real judges; they are pseudo-judges—who are political appointees from the member states who have been sent to make political decisions, not legal decisions.”Footnote 135 In the same vein, some critics have called for the appointment of more life-long career judges to the ECtHR, arguing that the bench is “lacking experience in the realities of law.”Footnote 136

All that being said, we would sound a strong cautionary note about any trend toward electing more—or mostly—career judges to the ECtHR. The example of the US Supreme Court is instructive in this respect. Lee Epstein, Jack Knight, and Andrew Martin find, on the basis of a comprehensive quantitative analysis, that the emergence of a norm of prior judicial experience for appointment to the Supreme Court resulted in a “highly problematic level of career homogeneity” on the bench.Footnote 137 They lament this result, mostly for the reasons we outlined earlier: Professional diversity is an important epistemic resource in a collegial decision-making body. In addition, Epstein, Knight, and Martin observe that that women and members of racial/ethnic minorities “are less likely than White men to hold the positions that are . . . steppingstones to the bench,” and so the norm of prior judicial experience also works to limit other kinds of diversity.Footnote 138

The data suggest that a shift towards a streamlined and professionally homogenous bench, similar to what occurred at the US Supreme Court, may be emerging at the ECtHR and this development may create similar risks. Unlike the US Supreme Court, the ECtHR is an inherently diverse institution; with judges coming from forty-seven member states, there is a great deal of variance in the judges’ experiences and outlooks. Having said that, beyond national and cultural diversity, which are inevitable by the design of the ECtHR, professional diversity is a more delicate commodity; it is vulnerable to the ascendency of a particular profile of the ideal career judge. As in the US context, this model may also be a barrier to other kinds of diversity on the ECtHR. As Koen Lemmens points out, the only female candidate in the most recent election of a Belgian judge was not put on the list because she did not have any judicial experience.Footnote 139 Incidents like this are warning signs that the Council of Europe’s efforts to improve the gender balance of the ECtHR may inadvertently be counteracted by well-meaning efforts to raise the professional qualifications of nominees for the Court.

G. Conclusion

Professional diversity should be understood as one important potential resource for enhancing the overall quality of the ECtHR. Much like a sports team, the Court can benefit from various skillsets and specialisms. The interview data we presented support this view; the Strasbourg judges themselves would seem to broadly agree that professional diversity is a valuable asset for the Court. In addition to stressing the importance of collegiality, they welcome the enhanced range of expertise and perspectives that a variety of professional profiles can bring to the bench. These views should be taken seriously, even if the judges do not formally take part in the selection process; only the Strasbourg judges themselves have firsthand insight into what helps or hinders judicial decision-making on the ECtHR.

Unfortunately, with the notable exception of gender diversity, the overall composition of the bench, including its professional diversity, has never been in the forefront of the reform of judicial selection to the ECtHR. Instead, reforms have mostly focused on ensuring that the best individual candidate is elected. In the absence of a clear strategy at the Council of Europe bodies about the overall composition of the bench, any professional diversity on the ECtHR is left to chance. This is a precarious situation. The quantitative evidence we presented in this Article suggests that the Court’s professional diversity may be under threat by a growing tendency to elect career judges or to favor judicial experience above all other kinds of professional experience.

These concerns are not purely academic; they can and should inform the working methods of the panels selecting and interviewing the candidates, as well as the policymakers reforming the system of s/election of judges. Strategic reform of ECtHR s/election system could include the following three innovations: First, the importance of professional diversity could be mainstreamed in the nomination process in much the same way as gender balance has already been. That is to say, the Council of Europe could actively encourage the member states to submit a list of nominees of various career backgrounds. Second, and as an important complement to the first reform, the Council of Europe could adjust its own procedures to reflect the need for professional diversity. The Committee for the election of judges, which interviews candidates and publishes suggestions, could explore the composition of the Court to determine which professional backgrounds are relatively under- or over-represented on the bench, much like what the Judicial Appointments Commission in the UK does with respect to barrister and solicitor backgrounds on the bench. Third, a representative of the Court could participate in an observatory capacity during the interviews and express the preferences of the Court to the Committee. No doubt, the logistics of these or similar reforms would need to be examined and fleshed out in more detail by the relevant stakeholders. We hope, however, that the evidence and argument we have presented in this Article will shift the debate about the composition of the ECtHR, putting the hitherto neglected issue of professional diversity squarely on the agenda for scholars and policymakers alike.