1. Introduction.

Intensifiers, defined as devices that scale a quality upward or downward from an assumed norm (Bolinger Reference Bolinger1972:17, Quirk et al. Reference Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik1985:589–590, Biber et al. Reference Biber, Stig Johansson, Conrad and Finegan1999:554), can be used to impress, persuade, praise, and generally influence the interlocutor’s reception of a message (Partington Reference Partington, Baker, Francis and Elena-Bonelli1993:178). It therefore comes as no surprise that intensifiers are subject to perpetual renewal, recycling, and replacement (Ito & Tagliamonte Reference Ito and Tagliamonte2003, Tagliamonte Reference Tagliamonte and Méndez-Naya2008, D’Arcy Reference D’Arcy2015, Stratton Reference Stratton2020a, 2022) as overuse, diffused use, and long-time use leads to a diminishment in an intensifier’s ability to boost and intensify (Tagliamonte Reference Tagliamonte and Méndez-Naya2008:391). Several quantitative analyses have found that both linguistic (for example, syntactic function) and social factors (for example, gender, age, socioeconomic status) influence intensifier use (Ito & Tagliamonte Reference Ito and Tagliamonte2003, Macaulay Reference Macaulay2006, Tagliamonte Reference Tagliamonte and Méndez-Naya2008, Fuchs Reference Fuchs2017, Stratton Reference Stratton2020b). In general, intensifier frequency has been found to correlate with collo-cational width (Stratton Reference Stratton2022), women have been found to use intensifiers more frequently than men (Fuchs Reference Fuchs2017, Stratton Reference Stratton2020b), and younger generational cohorts have been found to use intensifiers more frequently than older generations (Ito & Tagliamonte Reference Ito and Tagliamonte2003, Barnfield & Buchstaller Reference Barnfield and Buchstaller2010, Fuchs Reference Fuchs2017, Stratton Reference Stratton2020b).

Crucially, however, the above studies focus predominantly on English (Peters Reference Peters and Kastovsky1994, Paradis Reference Paradis2000, Ito & Tagliamonte Reference Ito and Tagliamonte2003, Méndez-Naya Reference Méndez-Naya2003, Tagliamonte & Roberts Reference Tagliamonte and Roberts2005, Macaulay Reference Macaulay2006, Tagliamonte Reference Tagliamonte and Méndez-Naya2008, Barnfield & Buchstaller Reference Barnfield and Buchstaller2010, D’Arcy Reference D’Arcy2015, Fuchs Reference Fuchs2017, Stratton Reference Stratton2020a, 2020c, 2021), and so it is unclear whether the same linguistic and social constraints operate on the intensifier system in other Germanic languages. Crosslinguistic and cross-Germanic data are therefore neces-sary for a more comprehensive understanding of the social and linguistic constraints associated with intensifier variation and change.

While there is some work on Dutch (ten Buuren et al. Reference Buuren, van de Groep, Collin, Klatter and de Hoop2018, Richter & van Hout 2020) and Icelandic (Indridason Reference Indridason and Götzsche2018), other than recent work on German (Stratton Reference Stratton2020b), variationist studies on intensifier variation and change in Germanic languages outside of work on English are scarce. Norwegian in particular has received little attention. Of the previous studies (Skommer Reference Skommer1993, Livanova Reference Livanova1997, Ebeling & Ebeling Reference Ebeling and Ebeling2015, Westervoll Reference Westervoll2015, Wilhelmsen Reference Wilhelmsen2019, Fjeld Reference Fjeld2020), there is only one empirical analysis of sociolinguistic variation (Fjeld Reference Fjeld2020). The remaining studies are either descriptive in nature or have focused exclusively on written discourse, which is of little help. Given that intensification is primarily a dialogic phenomenon (D’Arcy Reference D’Arcy2015:451), the analysis of intensifiers in spoken vernacular Norwegian is of particular importance. The lack of research on intensifiers in Norwegian is also consistent with the general dearth of literature on intensification in other Scandinavian languages, especially with respect to the use of intensifiers in vernacular speech.

The present study uses variationist quantitative methods to provide a sociolinguistic analysis of intensifiers used in the Norwegian variety spoken in Oslo. Following the Labovian tradition, where analyses have typically been limited to specific speech communities (such as Labov Reference Labov1966, 1972), the present analysis focuses on the speech community of Oslo, the capital and most populous city of Norway. Using the Norsk Talespråkskorpus Oslodelen (Norwegian Speech Corpus Oslo part; henceforth, NoTa-Oslo), a spoken corpus stratified for gender and age, two research questions were formulated based on previous research. First, what is the distribution of intensifier variants in the Oslo speech community? In other words, are amplifiers (such as veldig ‘very’) used more frequently than downtoners (such as litt ‘a little bit’); are specific types of intensifiers (for instance, boosters) used more frequently than others (such as maximizers), and within these subsets, which are the most frequently used variants (such as svært, veldig ‘very’)? Second, which linguistic and social factors condition and constrain this system? Specifically, do the internal (for example, collocational width) and external factors (such as gender and age), which have been found to influence the English and German intensifier system, also affect the intensifier system in Oslo Norwegian? Does the observation that women have a statistical tendency to use intensifiers more frequently than men (for instance, Fuchs Reference Fuchs2017, Stratton Reference Stratton2020b) also hold true in the Oslo speech community, and is there a difference between the variants favored by younger speakers and older speakers? Answering these questions provides local insight into the quantitative makeup of the intensifier system of Oslo Norwegian while also contributing more broadly to our understanding of the factors that shape intensifier variation and change in general.

The paper is structured as follows. Section 2.1 starts with a terminological overview of intensifiers, followed by a review of the literature on Norwegian intensifiers in section 2.2. Section 2.3 discusses the linguistic and social factors that have been found to condition and constrain intensifier variation and change in English and German. The methodology is presented in section 3, which contains information about the corpus design in section 3.1, and the data coding process in section 3.2. The results are reported in section 4, divided into the distributional analysis in section 4.1 and the multivariate analysis in section 4.2. The results are subsequently discussed in section 5, followed by concluding and global remarks on intensifier variation and change in section 6.

2. Literature Review.

2.1. Terminology.

According to the Norsk referansegrammatikk (Faarlund et al. Reference Faarlund, Svein and Ivar Vannebo1997:806), degree adverbs are adverbs “som uttrykkjer mengd, intensitet eller grad” [which express quantity, intensity, or degree]. This definition is in line with the traditional terminology used to describe intensifiers in work on English, such as “degree words” (Bolinger Reference Bolinger1972:18), “degree modifiers” (Paradis Reference Paradis1997), and “degree intensifiers” (Allerton Reference Allerton, Steele and Threadgold1987). However, over the last two decades, the label intensifier has emerged as an umbrella term to describe different intensifying devices (Ito & Tagliamonte Reference Ito and Tagliamonte2003, Tagliamonte & Roberts Reference Tagliamonte and Roberts2005, Tagliamonte Reference Tagliamonte and Méndez-Naya2008, D’Arcy Reference D’Arcy2015, Fuchs Reference Fuchs2017, Stratton Reference Stratton2020a, 2020b, 2021, 2022). Although in the Norwegian literature intensifiers have been referred to as “gradsadverber” [degree adverbs] (Faarlund et al. Reference Faarlund, Svein and Ivar Vannebo1997:806, Livanova Reference Livanova1997:92), “intensifikatorer” [intensifiers] (Livanova Reference Livanova1997:111), “forsterkere” [amplifiers] (Westervoll Reference Westervoll2015), and “forsterkerord” [intensifying words] (Fjeld Reference Fjeld2020), in line with previous crosslinguistic work the present study uses the term intensifier, which refers to both amplifiers and downtoners.

According to Quirk et al. (Reference Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik1985:589–590), amplifiers (Norwegian forsterkere) are intensifiers that “scale upwards from an assumed norm,” as in boka var veldig morsom ‘the book was very funny’, and down-toners (Norwegian dempere/forminskere) are intensifiers that scale “downwards from an assumed norm,” as in boka var litt morsom ‘the book was a little funny’. Amplifiers are further subdivided into maxi-mizers and boosters, according to the degree of amplification (ibid). Maximizers “denote the upper extreme of the scale,” as in han var helt syk ‘he was extremely/completely sick’, and boosters “denote a high degree, a high point on the scale,” as in han var så syk ‘he was so sick’. Boosters typically intensify scalar adjectives, which are adjectives that do not have clear minimum and maximum reference points, as in veldig kort ‘very short’ and veldig stor ‘very big’. In contrast, maximizers are thought to intensify adjectives that do have minimum and maximum thresholds, as in helt umulig ‘completely impossible’.

Downtoners are further divided into approximators, compro -misers, diminishers, and minimizers, according to the degree of moderation (ibid). Approximators “serve to express an approximation,” as in det er bortimot umulig ‘it is almost impossible’; compromisers “have only a slight lowering effect,” as in han er temmelig egoistisk ‘he is rather selfish’; diminishers “scale downwards and roughly mean ‘to a small extent’,” as in hun er litt trist ‘she is a little sad’, and minimizers are “negative maximizers” with the almost equivalence of “(not) to any extent’,” as in det er neppe interessant ‘it is hardly interesting’.

Previous quantitative analyses on English (D’Arcy Reference D’Arcy2015:460, Stratton Reference Stratton2020d:48–50) and German (Stratton Reference Stratton2020b:200) suggest that amplifiers are more frequent than downtoners, and within the subset of amplification, boosters are more frequent than maximizers. Whether this pattern holds true for Norwegian is one of the empirical questions that the present study aims to address. To facilitate crosslinguistic compar-isons, we operationalize the scalar taxonomy of Quirk et al. (Reference Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik1985:589–590). Classifying intensifiers according to this taxonomy is in line with work on English (Ito & Tagliamonte Reference Ito and Tagliamonte2003, Tagliamonte & Roberts Reference Tagliamonte and Roberts2005, Tagliamonte Reference Tagliamonte and Méndez-Naya2008, D’Arcy Reference D’Arcy2015) and German (Stratton Reference Stratton2020b), as well as with previous accounts of Norwegian (Bardas Reference Bardas2008, Ebeling & Ebeling Reference Ebeling and Ebeling2015, Westervoll Reference Westervoll2015, Wilhelmsen Reference Wilhelmsen2019). Moreover, our use of this scalar taxonomy is “in keeping with the principles of defining the envelope of variation” (Stratton Reference Stratton2020b:189).

2.2. Norwegian Intensifiers.

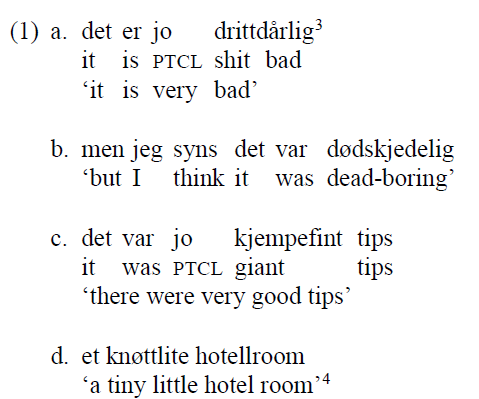

Although intensifiers can intensify several parts of speech, following previous work (Stratton Reference Stratton2020a, 2020b, 2021, 2022), the present study focuses on adjective intensification, which is thought to be most frequent (Bäcklund Reference Bäcklund1973:279, Androutsopoulos Reference Androutsopoulos1998:457–458, Westervoll Reference Westervoll2015:4). As in other Germanic languages (for example, for Dutch, see Klein Reference Klein1998:58–60; for Icelandic, see Indridason Reference Indridason and Götzsche2018:148; for German, see Stratton Reference Stratton2020b:186), adjectives in Norwegian can be intensified both morphologically, as in 1, and syntactically, as in 2.Footnote 1 For additional emphasis, Norwegian intensifiers can also be stacked, as in skikkelig skikkelig søt ‘really really cute’ (referred to as iteration); they can co-occur with other intensifiers, as in så veldig sulten ‘so very hungry’ (referred to as co-occurrence), and they can be used in conjunction with modal particles, such as jo, as in det er jo drittdårlig ‘it is really really bad’.Footnote 2

Relative to the number of studies on intensifiers in English, work on Norwegian intensifiers is underrepresented in research on language variation and change, and, to date, there have been no variationist sociolinguistic analyses of the Norwegian intensifier system. To the best of our knowledge, previous literature is limited to a small number of master theses (Bardas Reference Bardas2008, Westervoll Reference Westervoll2015, Wilhelmsen Reference Wilhelmsen2019), a recent corpus-based sociolinguistic analysis (Fjeld Reference Fjeld2020), and a limited number of descriptive and formal semantic works (Skommer Reference Skommer1993, Livanova Reference Livanova1997, Svenonius & Kennedy Reference Svenonius, Kennedy and Frascareilli2006, Ebeling & Ebeling Reference Ebeling and Ebeling2015). Skommer (Reference Skommer1993) examined the use of morphological intensification in Norwegian, focusing on semantic denotation. Ebeling & Ebeling (Reference Ebeling and Ebeling2015) carried out a comparative analysis of the downtoner mer eller mindre ‘more or less’, and Westervoll (Reference Westervoll2015) examined the grammaticalization of Norwegian intensifiers. In one of the most recent studies to date, Wilhelmsen (Reference Wilhelmsen2019) compared the use of intensifiers in English and Norwegian written fiction and nonfiction texts. He found that så ‘so’, for ‘too’, and helt ‘completely’ were the three most frequently used Norwegian variants. In a corpus-based analysis, which included both spoken and written data, Fjeld (Reference Fjeld2020) found that veldig ‘very’ and jævlig ‘very’ were the most frequent variants. However, because of the methodological decision to measure frequency by normalizing and comparing the absolute frequency with the number of words per corpus, the analysis was unable to determine whether women were more likely to intensify than men and whether intensifier choices differed by gender. Because the number of words in a corpus is not the envelope of variation (Stratton Reference Stratton2020b:207), to accountably examine the effect of social factors such as gender and age, it is important to follow the Principle of Accountability (Labov Reference Labov1969:737–738). Therefore, given the predominant focus on written genres, and the absence of variationist sociolinguistic work, it is clear that Norwegian intensifiers warrant further research.

2.3. Linguistic and Social Constraints.

The extensive work on intensifiers in English has shown that intensifier use correlates with several linguistic and social factors (Ito & Tagliamonte Reference Ito and Tagliamonte2003, Tagliamonte & Roberts Reference Tagliamonte and Roberts2005, Tagliamonte Reference Tagliamonte and Méndez-Naya2008, Fuchs Reference Fuchs2017). With respect to the linguistic factors, several studies have found that intensifier frequency correlates with the syntactic position and semantic classification of the intensified head (Ito & Tagliamonte Reference Ito and Tagliamonte2003, Tagliamonte & Roberts Reference Tagliamonte and Roberts2005, Tagliamonte Reference Tagliamonte and Méndez-Naya2008, Tagliamonte & Denis Reference Tagliamonte and Denis2014, Stratton Reference Stratton2022). For instance, frequent collocation with predicative adjectives (as in det er veldig lett ‘it is very easy’) is argued to be indicative of a fully developed intensifier, whereas collocation with only attributive adjectives (as in en skikkelig bra film ‘a proper good movie’) is argued to be indicative of either an outgoing receding variant or the arrival of a novel but latent variant (Mustanoja Reference Mustanoja1960:326–327, Tagliamonte Reference Tagliamonte and Méndez-Naya2008:373, Tagliamonte & Denis Reference Tagliamonte and Denis2014:116).

The number of semantic classes an intensifier is compatible with, as defined by Dixon’s classification of adjectives (1977:31, 2005:484–485), has also been found to correlate with frequency (Stratton Reference Stratton2022): More frequently used intensifiers collocate with adjectives from a higher number of semantic categories, and receding and less frequently used intensifiers collocate with adjectives from a smaller number of semantic categories (Ito & Tagliamonte Reference Ito and Tagliamonte2003:268, Méndez-Naya Reference Méndez-Naya2003:377, Stratton Reference Stratton2020a:220–221).Footnote 5 Of the 11 categories laid out by Dixon (Reference Dixon2005:484–485), adjectives of value, physical propensity, and human propensity, are usually reported as the most frequently intensified due to the symbiotic relationship between intensifier use and emotional expressivity (Athanasiadou Reference Athanasiadou2007, Méndez-Naya Reference Méndez-Naya, Dury, Gotti and Dossena2008:44).

Studies have also used the polarity of an intensified head to provide insight into an intensifier’s development (Partington Reference Partington, Baker, Francis and Elena-Bonelli1993:183, Klein Reference Klein1998:25). For instance, an intensifier derived from a source of negative evaluation (such as terribly) is argued to have undergone semantic bleaching if it comes to intensify adjectives of positive evaluation (as in terribly funny). An example of semantic bleaching in Norwegian is kjempe ‘very’, which started out as the noun kjempe ‘giant’, but, in its use as an intensifier, has come to intensify adjectives such as liten ‘small’ (as in hun er kjempeliten ‘she was very small’). Similar develop-ments have also taken place in Swedish, with the noun jätte ‘giant’, which too became an intensifier, as in jättebra ‘very good’.Footnote 6

As for the social constraints, several social factors have been found to influence intensifier use, such as gender (Tagliamonte Reference Tagliamonte and Méndez-Naya2008, D’Arcy Reference D’Arcy2015, Fuchs Reference Fuchs2017, Stratton Reference Stratton2020b, 2020d), age (Ito & Tagliamonte Reference Ito and Tagliamonte2003, Tagliamonte Reference Tagliamonte and Méndez-Naya2008), and socioeconomic status (Macaulay Reference Macaulay1995, Reference Macaulay2002). Studies on both English (D’Arcy Reference D’Arcy2015, Fuchs Reference Fuchs2017) and German (Stratton Reference Stratton2020b) have found that women have a statistical tendency to intensify adjectives more frequently than men. While causation is speculatory, explanations for the higher frequency among women come from two principal schools of thought. On the one hand, women may use intensifiers more frequently to compensate for their potential suppression within society (Lakoff Reference Lakoff1975, Erikson et al. 1978, Holmes Reference Holmes1992:316). On the other hand, the higher frequency of intensifiers among women may be attributed to their higher sociability and expressivity when compared to men (Carli Reference Carli1990). However, some evidence from English and German suggests that although women use amplifiers more frequently than men, men employ downtoners more frequently than women (D’Arcy Reference D’Arcy2015, Stratton Reference Stratton2020b), suggesting that while women scale up the meaning of an adjective more frequently than men, men scale down the meaning of an adjective more frequently than women (Stratton Reference Stratton2020b:206). To confirm the crosslinguistic validity of these gender effects, additional analyses of other languages such as Norwegian are necessary. In line with the general principles of linguistic change (Labov Reference Labov2001:274–275), women have also been found to lead in the use of novel or incoming intensifier variants (see, among others, Tagliamonte & Roberts Reference Tagliamonte and Roberts2005). However, whether women spearhead changes in the intensifier system in Norwegian remains to be investigated.

As for age, apparent-time analyses generally indicate that younger speakers have higher intensification rates than older speakers (Ito & Tagliamonte Reference Ito and Tagliamonte2003:265, Barnfield & Buchstaller Reference Barnfield and Buchstaller2010:261–262, Stratton Reference Stratton2020b:207). Studies have also found age to correlate with intensifier choice (Ito & Tagliamonte Reference Ito and Tagliamonte2003, Tagliamonte Reference Tagliamonte and Méndez-Naya2008, Stratton Reference Stratton2020b), suggesting, based on the apparent-time construct, that if a variant is favored by young speakers but not by older generations, there is a change in progress (Bailey et al. Reference Bailey, Wikle, Tillery and Sand1991, Labov, Reference Labov1994). Given the absence of previous variationist work on Norwegian intensifiers, it is unclear whether the aforementioned linguistic and social constraints are applicable to Norwegian. It is for this reason that these factors are included in the present analysis.

3. Methodology: Corpus, Data Collection, and Coding.

The source of linguistic data for this study was the NoTa-Oslo corpus (Johannessen & Hagen Reference Johannessen and Hagen2008), which consists of audio-visual recordings of informal spoken interviews from 2004 to 2006. Following the practices of the sociolinguistic interview (Tagliamonte Reference Tagliamonte2006), interviews were carried out in speakers’ homes where possible. However, unlike traditional sociolinguistic interviews, the interviewees were asked to speak among themselves in pairs as opposed to interacting with the interviewer. This decision was made to maximize the input from native speakers, while minimizing the input from the interviewer.

A total of 166 native speakers from the Oslo region were recorded, of which 144 were equally balanced for gender (f=72, m=72), age (16–25=48, 26–50=48, 51+ =48), and education (university educated=70, not university educated=70). This stratified design, in addition to the availability of part-of-speech annotation, makes this corpus particularly amenable to a sociolinguistic analysis. After the removal of the four speakers for whom there is no education information, 140 speakers remain. Each speaker spoke for approximately 30 minutes, amounting to approximately 957,000 orthographically transcribed words in total. Both audio and video recordings were taken of the initial conversations, which were subsequently transcribed orthographically and are now accessible through the corpus platform.

Following recent variationist work (Stratton Reference Stratton2020b), a random sample of 5,000 adjectives was extracted from the corpus using the appropriate part-of-speech annotation. Once downloaded, the envelope of variation was circumscribed to a functionally equivalent context, namely, intensifiable adjectives. In line with previous work (Ito & Tagliamonte Reference Ito and Tagliamonte2003, Tagliamonte & Roberts Reference Tagliamonte and Roberts2005, Tagliamonte Reference Tagliamonte and Méndez-Naya2008, D’Arcy Reference D’Arcy2015, Stratton Reference Stratton2020b, 2021), nonintensifiable adjectives, such as classifiers (for example, finansiell ‘financial’, daglig ‘daily’, utvendig ‘external’), as well as negative (for example, jeg er ikke så flink ‘I am not so good’, jeg er ikke så gammal ‘I am not that old’), comparative (for example, litt bedre ‘a little better’, litt smartere ‘a little smarter’), and superlative tokens (for example, viktigste ‘most important’) were manually removed from the pool of analysis. Negative contexts were removed because “negation alters the semantic-pragmatic thrust of intensification and creates non-equivalence of meaning in the context under examination,” and comparative and superlative tokens were removed because these contexts can block intensification (D’Arcy Reference D’Arcy2015:459). Further functionally nonequivalent contexts, such as comparative constructions, as in så [+adj] som ‘as…as’, adjectives occurring after hvor ‘how’ (for example, hvor mange ‘how many’ and hvor gammel er du? ‘how old are you?’), and fossilized nongradable collocations, such as så klart ‘of course’ and vær så snil ‘please’, were also not included in the envelope of variation. Special care was also taken to remove adverbial tokens, some of which were tagged as adjectives in the corpus and thus appeared in the random sample (for instance, det går bra ‘it is going well’, det gikk så fint ‘it went so well’).

After a qualitative weeding of the data, each adjective utterance was coded for the absence (for example, huset er ∅ stort ‘the house is big’) or occurrence (for example, huset er veldig stort ‘the house is very big’) of a preceding intensifier—a practice consistent with the Principle of Accountability. Each intensifier was also coded for scalar function, that is, whether it was an amplifier or a downtoner. Because emphasizers (such as særlig ‘particularly’) are not scalar and instead are used to “reinforce the truth value” of a clause or utterance (Quirk et al. Reference Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik1985:583), their presence did not count as an instance of intensification.

The variant utrolig ‘unbelievably’ presented a unique set of methodological challenges. While it started out as an emphasizer (u- ‘un’ + tro ‘believe’ + the adverbial/adjectival suffix -lig), it is not entirely clear whether, in its current use, it has developed a scalar interpretation. For instance, the English intensifier very, which entered English from Anglo Norman verray ‘true/real’ (from Latin verus ‘real’), was first used as an emphasizer prior to developing a scalar function, but this original meaning has been bleached semantically (Bolinger Reference Bolinger1972:18, Peters Reference Peters and Kastovsky1994:270, Stratton Reference Stratton2020b:191). While this may have happened with utrolig, it is unclear at which point an emphasizer becomes scalar. Even if its modern function is interpreted as scalar, it is unclear whether utrolig should be categorized as a booster or a maximizer. For these reasons, tokens of utrolig were also removed from the pool of analysis.Footnote 7

As for dritt- ‘very’ (lit. ‘shit’), it appeared in two orthographic forms in the corpus transcriptions: drit and dritt. When the NoTa-Oslo corpus was launched, the official spelling called for the adoption of the latter orthography (that is, dritt), both in the noun (dritt ‘shit’) and intensifier (dritt- ‘very’) form. However, it is unclear whether the orthographic transcriptions in the corpus reflect these variable spellings or whether they reflect perceived differences in pronunciation. Fjeld (Reference Fjeld2008:24–25) suggests that drit- and dritt- are pronounced differently and may therefore have different collocational patterns, but both can intensify adjectives of negative and positive evaluation. In listening to the audio recordings, we too noticed a vowel quality distinction, with a slightly longer vowel for drit- than dritt-. However, the difference was not always perceptually salient, sometimes caused by slightly poor audio quality and speakers talking over one another. A more full-scale acoustic analysis would provide some clarity on these possible temporal differences in vowel length, but given the overall low frequency of drit- and dritt- in the corpus (n=14), in this study they were treated as variable spellings of the same underlying intensifier. In fact, one speaker vacillated between the two forms in the same conversation, with dritfett ‘very cool’ pronounced with a slightly longer vowel and drittfett ‘very cool’ pronounced with a slightly shorter vowel. Of the 14 tokens, 13 were written together (for instance, dritvarm ‘very warm’, dritlang ‘very long’) and only one was written separately (var drit lei seg ‘was very sorry’). Because there were no notable perceptual differences between the two, meaning that the distinction between the morphological (as in dritvarm ‘very warm’) and the syntactic form (as in drit lei seg ‘very sorry’) may simply be an orthographic one, given the higher frequency of the bound form, in this study dritt- is used as the generic label for both.

Similarly, although kjempe can theoretically be used as both a morphological (as in det er kjempefint ‘it is very good’) and syntactic intensifier (as in kjempe ordentlig ‘very appropriately’), of the 22 tokens in the sample, all were written together. Even intensified instances of present (for example, kjempespennende ‘very exciting’) and past participial or deverbal adjectives (for example, kjempefornøyde ‘very satisfied’) were written together as one word. In the entire corpus, that is, beyond the sample, we found only two instances of the intensifier kjempe written separately. While it is possible that there are some prosodic differences between the morphological and syntactic use, with a potential differentiation in degree or meaning, of the few instances in the corpus, there were no perceptible differences between the two.

For the multivariate analysis, in line with variationist work, a mixed effects logistic regression model was run using Rbrul (Johnson Reference Johnson2009). Intensification was run as the dependent variable, that is, the absence or occurrence of a preceding intensifier. Both linguistic (syntactic position, semantic classification) and social factors (gender, age, education) were included as independent variables. The factor syntactic position had two levels: [attributive, predicative], and semantic classification had eleven levels: [dimension, physical property, speed, age, color, value, difficulty, volition, qualification, human propensity, similarity]. The factor gender had two levels: [male, female], age had three levels: [16-25, 26-50, 51+], and education had two levels [university educated, not university educated].Footnote 8 Speaker ID was also included as a random factor to account for any idiosyncrasies among the speakers.

4. Results.

4.1. Distributional Analysis.

Of the 5,000 adjectives, 1,910 were intensifiable, of which 854 were intensified. Adjectives were therefore intensified at a rate of 44.7% (see table 1). The 854 adjectives were intensified by 32 variants (see table 2). The number one variant was the booster veldig ‘very’, which made up almost one third of the intensifier system (31%), followed by the downtoner litt ‘a little bit’ in second position (22%), and the maximizer helt ‘completely’ in third position (14%). The intensification of adjectives in apparent time shows that younger speakers intensified adjectives more frequently than older speakers (see figure 1).

Table 1. Overall intensification rate.

Table 2. Frequency of intensifiers.

Figure 1. Intensification rate of adjectives in apparent time.

Because not all variants in table 2 are functionally equivalent, the variants were classified according to the taxonomy of Quirk et al. (Reference Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik1985:589). The proportion of amplifiers to downtoners is reported in figure 2, and the proportion of boosters to maximizers is reported in figure 3. Figure 2 indicates that amplification (n=604/854, or 70.7%) was more common than moderation (n=250/854, or 29.3%), and figure 3 indicates that boosters (n=479/604, or 79%) were more frequent than maximizers (n=125/604, or 21%). The booster veldig ‘very’, which was one of 20 boosters in the sample, was used more frequently than the total of all maximizers, which further illustrates the preference for boosting over maximizing. The distribution of boosters is reported in figure 4. With the exception of the maximizer helt ‘completely’, maximizers were infrequent. The variant helt made up 96% of the maximizer system (n=120/125), the remaining 4% occupied by low frequency variants: ekstremt ‘extremely’ (n=2), absolutt ‘absolutely’ (n=1), komplett ‘completely’ (n=1), and enormt ‘enormously’ (n=1).

Figure 2. Proportion of amplifiers and downtoners.Footnote 10

Figure 3. Proportion of boosters and maximizers.

Figure 4. The distribution of the booster system.

The system of boosters was dominated by predominantly three variants, veldig ‘very’ (n=264/479, or 55%), så ‘so’ (n=89/479, or 19%), and skikkelig ‘proper’ (n=50/479, or 10%). Their distribution in apparent time (figure 5) indicates that although veldig was the number one variant in all three age groups, its frequency decreased among younger cohorts. In contrast, skikkelig was rarely used among older generations, but its use increased in apparent time among younger generations, suggesting a change in progress. Although similar trends were observable for jævlig and dritt-, which increased in apparent time toward use among younger speakers, they still made up a small share of the booster system. Distributional evidence also suggests that kjempe- ‘very’ is an outgoing variant, making up 3.4% of the system among the 51+ cohort versus 3% in the 26–50 cohort and 1.8% in the 15–25 cohort. Examples of use from the dataset are provided in 3.

Figure 5. The use of veldig and skikkelig in apparent time.

As for the factors education and gender, although speakers with a university education had similar intensification rates (n=506/1121, or 45%) to speakers without a university education (n=343/779, or 44%), gender did make a difference, with women intensifying more adjectives (n=472/987, or 48%) than men (n=382/923, or 41%). Specifically, women (n=350/987, or 35.4%) used amplifiers more frequently than men (n=254/1126, or 22.5%), whereas the proportion of downtoner use was fairly consistent for both men (n=128/1126, or 11%) and women (n=121/987, or 12%), albeit with a minor descriptive difference of 2%. As for the use of specific intensifiers, skikkelig made up a larger share of the female booster system (n=36/286, or 13%) than the male booster system (n=14/182, or 8%), suggesting that women are spearheading the use of skikkelig. Use of variants such as dritt- was largely stable across gender, with only a small descriptive difference between men (n=8/182, or 4%) and women (n=6/268, or 2%). The same was also true for taboo intensifiers (such as fordømt, jævlig, dritt-), which were used infrequently by both men (n=19/923, or 2%) and women (n=12/987, or 1%).

Figure 6. Intensification rate by gender.

With respect to the syntactic function, predicative adjectives were intensified more frequently than attributive adjectives. Predicative adjectives were intensified 50% of the time (n=750/1504) and attributive adjectives were intensified 26% of the time (n=104/406). Distributional evidence also suggests that different intensifiers have different syntactic preferences. For instance, veldig intensified predicative adjectives 89% of the time (n=236/264) and attributive adjectives only 14% of the time (n=38/264). The intensifier litt ‘a little’ intensified attributive adjectives only 10% of the time (n=19/186) but predicative adjectives 90% of the time (n=167/186). The third most frequently used variant helt ‘completely’ was rarely ever used to intensify attributive adjectives (n=10/121), and instead was used to intensify predicative adjectives 92% of the time (n=111/121). The intensifier skikkelig ‘proper’ also intensified predicative adjectives (n=39/50) more frequently than attributive adjectives (n=9/50). Frequently used intensifiers therefore had a tendency to collocate with predicative adjectives over attributive adjectives. In contrast, infrequently used variants, such as svært ‘very’, predominantly intensified attributive adjectives.

As for the semantic properties, with the exception of the category volition, all of Dixon’s (2005:484–485) semantic categories were intensified in the sample. The category human propensity was intensified most frequently (n=159/252, or 63%), followed by adjectives of value (n=351/654, or 54%), physical propensity (n=89/214, or 42%), and dimension (n=91/241, or 37%). The distributional evidence also suggests that frequently used intensifiers are associated with a wider collocational distribution. For instance, så ‘so’, the second most frequently used booster, intensified adjectives belonging to all ten semantic categories. The most frequently used booster, veldig, frontrunner skikkelig, and most frequently used downtoner litt, collocated with adjectives from nine of the semantic categories, followed by the most frequently used maximizer helt, which collocated with adjectives from eight semantic categories. In contrast, less frequently used or outgoing variants, such as svært ‘very’, intensified a fewer number of categories. Therefore, based on the number of semantic categories they collocate with, så and skikkelig appear to be increasing in popularity, whereas variants such as kjempe- ‘very’, which intensified only five of the ten attested categories, show evidence of a decline in collocational width. The collocational distribution of skikkelig in particular suggests that its collocational width is broadening because, despite being the third most frequently used booster, it collocated with adjectives from the same number of semantic categories as the number one variant veldig. Its frequency in apparent time also supports this hypothesis (figure 5).

Although value adjectives were intensified most frequently by veldig, adjectives of speed had a higher probability of being intensified by så. This finding is particularly interesting given that veldig was used three times more frequently than så. As for adjectives denoting a physical property, even though their collocation with veldig was the highest, så and skikkelig were on par with each other. The dividing parameter was age, with speakers in the 16–25 cohort preferring skikkelig when intensifying adjectives of physical property (as in skikkelig stygg ‘proper ugly’, skikkelig trøtt ‘proper tired’, skikkelig usun ‘proper unhealthy, skikkelig slitsom ‘proper exhausting’), whereas older speakers preferred veldig (as in veldig trygg ‘very safe’).

Of the 264 adjectives intensified by veldig, 72% were adjectives of positive evaluation (n=190/264) and 28% were adjectives of negative evaluation (n=74/264). This finding is consistent with its most frequent collocations, which were with adjectives of positive evaluation: veldig fint ‘very good’ (32 tokens), veldig bra ‘very good’ (20 tokens), and veldig glad ‘very glad’ (17 tokens). In contrast, skikkelig had the opposite preference. Of the 50 intensified adjectival heads, 30 could be categorized as denoting positive or negative semantic prosody, of which 62% (n=24/39) were adjectives of negative evaluation (such as dårlig ‘bad’, sur ‘angry’) and 38% (n=15/39) were adjectives of positive evaluation. Interestingly, the proportion of positive and negative evaluation adjectives intensified by så was equal: 52% (n=46/89) were positive evaluation adjectives and 48% (n=43/89) were negative evaluation adjectives.Footnote 11

The intensifier dritt- was used most frequently among younger speakers. Although it collocated with adjectives from only four semantic categories (value, human propensity, value, age), the fact that it occurred more frequently with more informal and colloquial adjectives (such as dritttaz ‘really dull/boring’), suggests, on the one hand, that its use may be constrained by register, but, on the other hand, that it is becoming common in Oslo Norwegian.Footnote 12 Given that dritt- intensified adjectives of both positive (for instance, dritgod ‘very good’ [lit. ‘shit good’]) and negative semantic evaluation (for instance, dritstreng ‘very strict’ [lit. ‘shit strict’]), it is clear that, in its use as an intensifier, its lexical meaning has been bleached semantically.

4.2. Multivariate Analysis.

To examine the statistical significance and relative weight of the linguistic (syntactic position, semantic type) and social factors (gender, age, education), a logistic regression was run in Rbrul (Johnson Reference Johnson2009). This model was chosen because of its ability to rank the factor constraints, as well as the individual levels within each factor by relative weight, and because of its ability to include each speaker (speaker ID) as a random factor of variation. Similar models have been run in previous studies (D’Arcy Reference D’Arcy2015, among others), and such analyses are therefore in line with the quantitative practices of modern variationist sociolinguistics (Tagliamonte Reference Tagliamonte2012, among others).

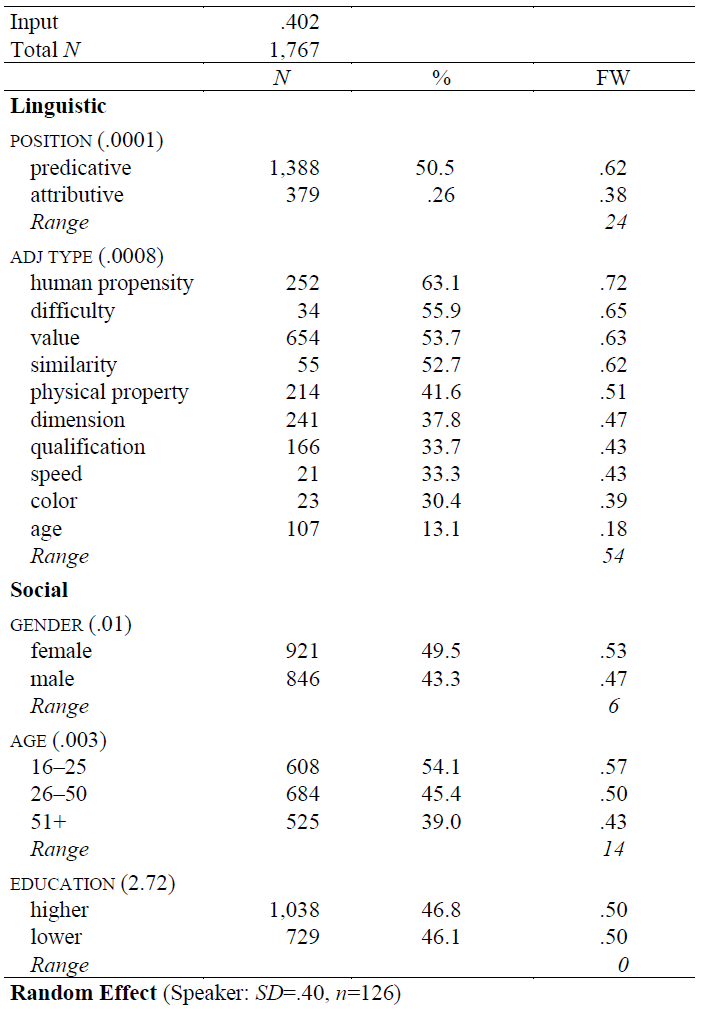

The output for the model is reported in table 3.Footnote 13 Four of the five factors were statistically significant. With respect to the linguistic constraints, predicative adjectives were intensified more frequently than attributive adjectives, and adjectives of human propensity, difficulty, value, similarity, and physical property were intensified more frequently than adjectives from semantic categories such as age and color. As for the social constraints, women intensified adjectives more frequently than men, and younger speakers intensified adjectives more frequently than older speakers. The range for the factor group semantic type (.54) indicated that of the four factors, semantic type had the strongest effect on the intensification of Norwegian adjectives, followed by the factor syntactic position (.24). The range for the factor group age (.14) indicated that of the three social factors, it contributed most to the observed variation.

Table 3. Logistic regression of the factors conditioning intensification.

In the next section, we discuss the results of the distributional and multivariate analyses. In particular, we focus on crosslinguistic findings with respect to the relative frequency of different types of intensifiers, their co-occurrence with adjectives belonging to different semantic categories, and the role that linguistic and social factors play in intensifier use.

5. Discussion.

To address the lack of sociolinguistic scholarship on Norwegian intensifiers, the present study used variationist quantitative methods to examine the intensifier system in Oslo at the onset of the 21st century. In doing so, several crosslinguistic findings emerged. First, as in English (D’Arcy Reference D’Arcy2015:460, Stratton Reference Stratton2020d:48–50) and German (Stratton Reference Stratton2020b:200), in Oslo Norwegian, amplifiers were more frequent than downtoners, and boosters were more frequent than maximizers. This quantitative evidence therefore suggests that speakers prefer to scale up the meaning of an adjective than scaling down its meaning, but boosting meaning is preferable to maximization.

Second, as in work on English and German (Ito & Tagliamonte Reference Ito and Tagliamonte2003, Tagliamonte Reference Tagliamonte and Méndez-Naya2008, D’Arcy Reference D’Arcy2015, Fuchs Reference Fuchs2017, Stratton Reference Stratton2020b), linguistic and social factors were found to have a significant effect on the use of intensifiers. Predicative adjectives were intensified more frequent-ly than attributive adjectives, and certain semantic categories (such as value and human propensity) favored intensification more than others (such as color and age). The fact that predicative adjectives were intensified more frequently than attributive adjectives is in line with work on English (Stratton Reference Stratton2022). In general, collocation with predicative adjectives is thought to be indicative of a developed as opposed to latent intensifier. Distributional evidence from Oslo Norwegian seems to support this claim given that highly frequent delexicalized intensifiers, such as veldig, intensified predominantly predicative adjectives. In fact, this tendency was true for all scalar subsets, as the most frequently used maximizer, the most frequently used booster, and the most frequently used downtoner appeared more frequently with predicative adjectives.

As for the semantic classification, the fact that adjectives of value and human propensity were intensified most frequently is consistent with findings from English (Méndez-Naya Reference Méndez-Naya, Dury, Gotti and Dossena2008:44). Although difficulty was the second most frequently intensified semantic category, unlike the categories human propensity and value, the distribution of adjectives of difficulty might not be particularly representative since there were only 32 tokens versus the 200–600 tokens for other categories. Because intensifiers allow speakers to express subjectivity (Athanasiadou Reference Athanasiadou2007), it is not surprising that the adjectives that express subjectivity (that is, adjectives of value and human propensity) are the ones that are most frequently intensified.

The social factors gender and age also conditioned the use of intensifiers in Oslo Norwegian. Younger speakers had higher intensi-fication rates than older speakers, and women intensified adjectives more frequently than men. The higher intensification rate among younger speakers is consistent with findings from apparent time analyses in work on English (Ito & Tagliamonte Reference Ito and Tagliamonte2003:265, Barnfield & Buchstaller Reference Barnfield and Buchstaller2010:261–262) and German (Stratton Reference Stratton2020b:207). As for women’s tendency to use intensifiers more frequently than men, this finding also corroborates work on English (Fuchs Reference Fuchs2017) and German (Stratton Reference Stratton2020b), pointing toward a possible crosslinguistic and cross-cultural tendency. While it is not clear whether women use intensifiers more frequently to compensate for gender inequalities (Lakoff Reference Lakoff1975, Erikson et al. 1978) or because women are more expressive (Carli Reference Carli1990), the evidence that they use intensifiers more frequently than men is largely consistent across the three languages. It is clear that some linguistic features are associated with men and others with women (Weatherall Reference Weatherall, Nancy, Renee, Wickramasinghe and Wong2016), and this may explain the differences in intensifier use. Even a century ago, reference to women’s predilection for intensification was known (Stoffel Reference Stoffel1901:101, Jespersen Reference Jespersen1922:250). For instance, Stoffel (Reference Stoffel1901:101–102) wrote that “women are notoriously fond of hyperbole” and if men overuse intensifiers they are “ladies’” men. Therefore, the fact that women are the most frequent users of intensifiers is not unexpected. Interestingly, work on German (Stratton Reference Stratton2020b) and diachronic work on English (D’Arcy Reference D’Arcy2015) suggests that while women scale up the meaning of adjectives more frequently than men, men scale down their meaning more frequently than women. However, the present study was not able to confirm this finding. Although the use of downtoners among men was descriptively higher than its use among women, there was only a minimal difference of 1%. Additional work is therefore necessary to confirm or dispute this specific crosslinguistic trend.

As for the makeup of specific boosters, veldig, så, and skikkelig were the most frequent. Although veldig was the number one variant in all three age groups, apparent time analyses indicated that, at the time of the recordings, veldig was falling in popularity among younger speakers and was being replaced by the incoming variant skikkelig. Based on the assumptions of the apparent time construct, there is an observable change in progress. Not only was skikkelig used predominantly by younger speakers, it was also used more frequently among younger women, a finding that is consistent with the general principles of linguistic change (Labov Reference Labov2001:274–275).

The intensifier skikkelig is interesting for a number of reasons. First, diachronic evidence suggests that it has been around for quite some time. According to Norsk Ordbok (the Dictionary of Norwegian), skikkelig has had an intensifying function since at least the mid-18th century (as in han er skikkeleg galen ‘he is proper crazy’ attested in 1743), yet the apparent time distribution from the data at the beginning of the 21st century suggests that its use in Oslo was restricted to use among younger speakers (figure 5). One interpretation of this finding is that skikkelig was once used as an intensifier, but it may have later dropped out of vogue and declined in frequency and has only recently been co-opted back into the system by younger speakers. This hypothesis is supported by the fact that there were no instances of its use as an intensifier in Talesmålsundersøkelsen i Oslo (TAUS; the Spoken Language Investigation in Oslo), a corpus consisting of informal interviews from 1971–1973. This cycle of ebb and flow is characteristic of intensifier use in general (Stratton Reference Stratton2020a), as overuse, diffused use, and long-time use leads to a diminishing of an intensifier’s ability to boost and intensify (Tagliamonte Reference Tagliamonte and Méndez-Naya2008:391), which leads to the popularity of different intensifiers waxing and waning over time (Stratton Reference Stratton2020a). For instance, well was used as an intensifier in Old English (Stratton Reference Stratton2022), but by the mid-14th century, its use decreased in frequency to the point where, according to traditional scholarship, it was thought to have disappeared (Stratton Reference Stratton2020a:220). However, recent analyses indicate that it was picked up again in 20th and 21st century British English (Stratton Reference Stratton2018, Reference Stratton2020a). Therefore, the fact that skikkelig was used previously but seems to have dropped out of use for a period of time before being revived is in line with previous work on the diachronic waxing and waning of the popularity of intensifiers (Tagliamonte Reference Tagliamonte and Méndez-Naya2008, D’Arcy Reference D’Arcy2015, Stratton Reference Stratton2020a).

Second, skikkelig is interesting because its pathway of change appears to be one that is common crosslinguistically. Like the intensifier proper in British English (Stratton Reference Stratton2021), skikkelig appears to have developed from the adjective meaning ‘decent/appropriate/proper’, as in en skikkelig løsning ‘an appropriate solution’.Footnote 14 Similar patterns can be observed in Dutch (as in behoorlijk ‘proper/decent’ ![]() behoorlijk schoon ‘very clean’) and German (as in richtig ‘correct’

behoorlijk schoon ‘very clean’) and German (as in richtig ‘correct’ ![]() richtig schön ‘very nice’), where several adjectives of decency and appropriateness later developed into degree adverbs. In fact, the synonym of the Norwegian adjective skikkelig, namely, ordentlig ‘orderly’, has also developed an intensifying function, as in det ser ordentlig spennende ut ‘it looks really exciting’. Although ordentlig was not as frequent as skikkelig, which had 11 tokens of its use as an intensifier of adjectives in NoTa-Oslo, its intensifying use has been documented for a half a century. For instance, ordentleg god mat ‘really good food’ is attested in Norsk Ordbok from 1976. In becoming a marker of degree, these derived adverbs appear to first function as manner adjuncts prior to developing an intensifier function. For instance, Norwegian skikkelig first became an adverb of manner (as in å være skikkelig kledd ‘to be properly dressed’) and then developed into an adverb of degree (as in skikkelig irritert ‘very irritated’). The same is true for ordentlig (as in være ordentlig dekorert ‘to be properly decorated’

richtig schön ‘very nice’), where several adjectives of decency and appropriateness later developed into degree adverbs. In fact, the synonym of the Norwegian adjective skikkelig, namely, ordentlig ‘orderly’, has also developed an intensifying function, as in det ser ordentlig spennende ut ‘it looks really exciting’. Although ordentlig was not as frequent as skikkelig, which had 11 tokens of its use as an intensifier of adjectives in NoTa-Oslo, its intensifying use has been documented for a half a century. For instance, ordentleg god mat ‘really good food’ is attested in Norsk Ordbok from 1976. In becoming a marker of degree, these derived adverbs appear to first function as manner adjuncts prior to developing an intensifier function. For instance, Norwegian skikkelig first became an adverb of manner (as in å være skikkelig kledd ‘to be properly dressed’) and then developed into an adverb of degree (as in skikkelig irritert ‘very irritated’). The same is true for ordentlig (as in være ordentlig dekorert ‘to be properly decorated’ ![]() det var ordentlig stillig ‘it was really quiet’); similar diachronic sequences appear to have taken place in German with richtig (as in er macht das richtig ‘he is doing that correctly’

det var ordentlig stillig ‘it was really quiet’); similar diachronic sequences appear to have taken place in German with richtig (as in er macht das richtig ‘he is doing that correctly’ ![]() das war richtig geil ‘that was really cool’) and in British English with proper (as in we do things proper[ly] in this house

das war richtig geil ‘that was really cool’) and in British English with proper (as in we do things proper[ly] in this house ![]() that is proper interesting).Footnote 15 The development from adjective to adverb of manner to degree adverb is consistent with previous observations in the history of English (Nevalainen & Rissanen Reference Nevalainen and Rissanen2002, Méndez-Naya Reference Méndez-Naya2003).

that is proper interesting).Footnote 15 The development from adjective to adverb of manner to degree adverb is consistent with previous observations in the history of English (Nevalainen & Rissanen Reference Nevalainen and Rissanen2002, Méndez-Naya Reference Méndez-Naya2003).

The use of skikkelig is also interesting because, like the use of proper (Stratton Reference Stratton2021), its use appears to be led by younger generations, suggesting a possible reanalysis or reinterpretation of the function of these lexical items in language acquisition. However, its collocational distribution and syntactic preferences suggest that skikkelig is no longer a latent variant among younger cohorts. For instance, skikkelig intensified the same number of semantic categories as the most frequent booster veldig despite being three times less frequent. Moreover, skikkelig collocated more frequently with predicative adjectives than attributive adjectives. Because collocational width and frequent use with predicative adjectives are attributes of a frequently used and developed intensifier (Tagliamonte & Denis Reference Tagliamonte and Denis2014, Stratton Reference Stratton2022), skikkelig appears to be a versatile and established variant. We found no differences in the use of skikkelig according to the data from a location within Oslo, even though the East Oslo variety is generally thought to be influenced by local spoken dialects and the West Oslo variety is thought to be more influenced by the written standard/Dano-Norwegian (Hagen & Simonsen 2014). Forty-eight percent of the tokens (n=24/50) came from East Oslo and 52% (n=26/50) came from the rest of Oslo.Footnote 16 Similarly, no notable differences were observed for other intensifiers. For instance, half of the tokens of dritt- (n=7/14) came from East Oslo and half of the tokens (n=7/14) came from the remaining parts of Oslo. However, whether the intensifying use of skikkelig is generalizable to other Norwegian speech communities outside of Oslo is a question for future research. Given the correlation between lexical variation and sociogeographical belonging, it is reasonable to hypothesize that different speech communities would favor different variants, the use of gysla, kjøle, and fette ‘very’ being recent examples. Gysla (as in det er gysla varmt ‘it is very warm’) is an intensifier that seemingly indexes Southwest Norwegian speech; kjøle (as in det er kjøle varmt ‘it is really warm’) is an intensifier that indexes Central Norwegian speech, and fette (as in det er fettevarmt ‘it is very warm’), which has caused recent debate in Norwegian media, is indexical of North Norwegian speech.Footnote 17

In addition to skikkelig, the intensifier dritt- ‘very’ was constrained by age. Although it occurred only 13 times, its use was almost exclusive-ly restricted to the 16–25 cohort. A search for dritt- in the larger corpus, that is, beyond the sample of the 5,000 adjectives, confirms that in 2004–2006 its use was more common among younger speakers. Tokens of its use also illustrate that young speakers use dritt- to intensify novel adjectives (for example, den er egentlig dritfunny ‘it is actually really funny’, dritsjpa ‘really good’, dritkeen ‘really keen’, drittaz ‘really dull/boring’), many of which are loanwords. Its use by predominantly young speakers, its original denotation (as in drit ‘shit’, å drite ‘to shit’), as well as the types of adjectives it intensified suggests that its use is also restricted to informal registers. Its use as an intensifier of both adjectives of positive (as in dritkul ‘really cool’, dritgod ‘really good’) and negative semantic prosody (as in dritstreng ‘really strict’) also shows that dritt- has clearly undergone semantic bleaching and grammaticalization.

6. Conclusion.

Given the predominant focus on English intensifiers in previous research, the present study carried out a variationist sociolinguistic analysis of Norwegian intensifiers based on data from the Oslo speech community. While several local findings were uncovered about the sociolinguistic makeup of the Oslo intensifier system, such as the change in progress toward the use of skikkelig, the present study also provided cross-linguistic support for several findings about intensifier variation and change. Given the consistent methodology (that is, variationist socio-linguistic methods), a number of comparisons with work on English and German can be made to make some broader generalizations about intensifier variation and change in Germanic languages. First, younger speakers appear to be more prone to intensification than older speakers. Second, women have a statistical tendency to use intensifiers more frequently than men. Third, amplifiers are more frequent than down-toners, and within the subset of amplification, boosters are more frequent than maximizers. Fourth, frequently used intensifiers are usually ones that collocate most widely. Fifth, predicative adjectives are more prone to intensification than attributive adjectives. Finally, adjectives that are part of the semantic field of decency and appropriateness appear to have a propensity to develop an intensifying function: First, they become adverbs where they function as manner adjuncts and then become degree markers.

There are, however, a number of issues beyond the scope of the present study that remain to be investigated. This study focused on the Oslo speech community, and although the present findings can be used to make inferences about the larger Norwegian system, since each speech community is different, it is important to examine the intensifier system and the associated variable constraints in other speech communities across Norway. Similarly, given the lack of sociolinguistic work on Danish and Swedish, the study of intensifier variation and change would also benefit from future work on other Scandinavian languages. Therefore, in the interest of uncovering emerging patterns associated with intensifier variation and change in Germanic languages, the authors encourage future sociolinguistic work, particularly variationist socio-linguistic work, on different Norwegian speech communities as well as other Scandinavian languages in general. Given the time depth of the data (that is, 2004–2006), another question open for future research is whether the momentum of intensifiers such as skikkelig is maintained across new generations in Oslo or whether its use has been subject to age-grading. The authors hope to have created an impetus to investigate these topics and research questions.