Introduction

Luxembourg, a small country with a population of 640,000 inhabitants, adopted a multifaceted strategy to mitigate the transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in 2020. This strategy included an initial lockdown period, followed by extensive testing and real-time reporting of laboratory-confirmed cases. People who tested positive were isolated and their high-risk contacts were quarantined. These measures were instrumental in controlling early waves of the pandemic [1].

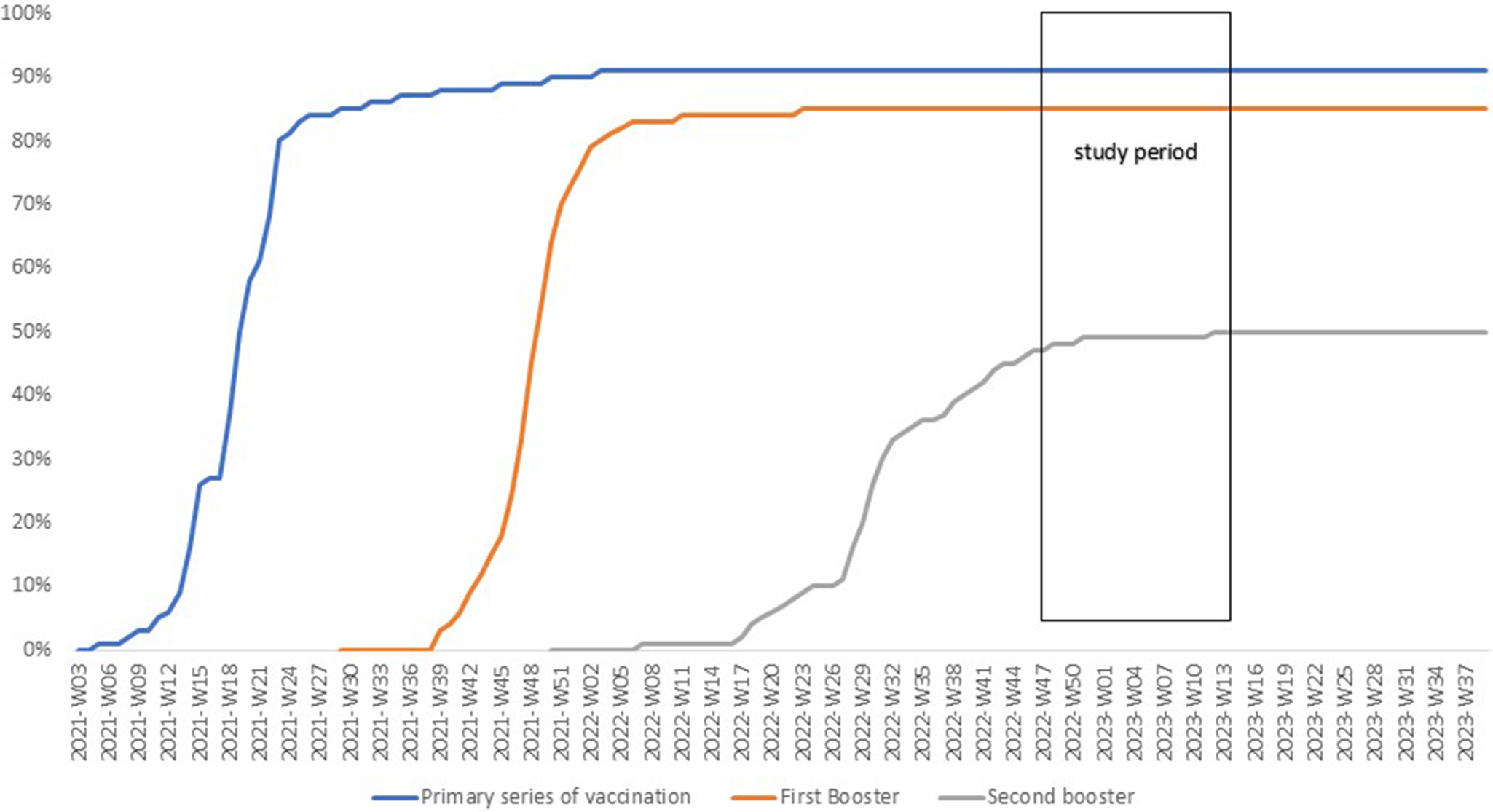

The introduction of COVID-19 vaccines in January 2021 marked a turning point in Luxembourg’s pandemic response. Prioritizing the most vulnerable populations, by the second week of June 2021, 79.5% of individuals aged ≥60 years had completed the primary series of vaccinations (PSV). In autumn 2021, the first booster doses using COVID-19 mRNA vaccines were administered. By the end of January 2022, 82.1% of ≥60 years old had received the first booster [2].

Initially, the COVID-19 mRNA vaccines were designed to target the spike protein of the original SARS-CoV-2 virus and were later referred to as monovalent vaccines [Reference Lopez Bernal3]. These vaccines provided cross-reactive immune protection against the Alpha and Delta variants of SARS-CoV-2. However, with the emergence of the Omicron variants and their sub-lineages in December 2021, the rates of reinfections and breakthrough infections increased. This trend was suggesting immune evasion and reduced protection against infection by monovalent vaccines [Reference Thompson4]. Therefore, in autumn 2022, bivalent vaccines adapted to target both the original SARS-COV-2 strains and Omicron variants (first BA.1, later BA.5) were approved for use, based exclusively on safety and immunogenicity studies [Reference Chalkias5, Reference Bennett6].

In September 2022, Luxembourg launched bivalent mRNA vaccines targeting BA.1 and later BA.4/BA.5, primarily for use as second boosters in individuals aged 60 and older. Monovalent vaccines also continued to be administered as second boosters. The epidemiological situation evolved in parallel with the genetic diversification of the virus, reflecting the emergence and replacement of dominant subvariants over time. From late September (week 38) to mid-November 2022 (week 46), Omicron BA.5 was the predominant subvariant, accounting for over 80% of sequenced cases. It was progressively replaced by BQ.1, which became dominant in mid-November and represented 75% of sequences by late December (week 52). In early January 2023, XBB.1.5-like recombinants emerged and rapidly increased. By early April 2023 (week 13), XBB.1.5 and XBB.1.9 accounted for 55.1% and 34.8% of cases, respectively [7]. Despite high booster vaccination coverage and the level of herd immunity suggested by a cumulative total exceeding 300,000 registered cases – approximately half of Luxembourg’s population – the incidence of new infections nevertheless increased during the last week of September 2022 and again in the first week of December 2022.

Real-world studies on the effectiveness of the bivalent vaccine have begun to emerge in 2023. A limited number of studies have assessed the effectiveness of bivalent vaccines against infection over short follow-up periods across various population groups, reporting mixed results ranging from no to moderate protection. Some of these studies highlighted that prior Omicron infection provides stronger immunity than the bivalent vaccine alone [Reference Kim8–Reference Mimura11]. A meta-analysis reported a pooled relative VE of 30.9% against infection. However, the included studies varied widely in terms of age groups, follow-up durations, and outcomes, with VE estimates ranging from no effect to as high as 83.0% [Reference Cheng12].

Natural immunity following SARS-CoV-2 infection varies in strength and duration and is influenced by the clinical severity of the initial infection. Symptomatic COVID-19, particularly moderate to severe cases, tends to elicit a stronger and more durable immune response, characterized by higher levels of neutralizing antibodies and more robust T-cell memory. In contrast, asymptomatic individuals still develop immunity – particularly T-cell responses – but of lower magnitude and with faster waning, especially in antibody levels [Reference Alshami13, Reference Havervall14].

Evidence on the effectiveness of bivalent vaccines as second boosters against Omicron is limited, particularly regarding how protection wanes over time and interacts with prior infection. Comparative data on their added benefit over monovalent boosters, are lacking and show heterogenous results in some cases, highlighting the need for further investigation. [Reference Bolormaa15].

We estimated absolute vaccine effectiveness against Omicron infection of being vaccinated with monovalent or bivalent as a PSV + 2 booster vaccines accounting for time since the second booster and natural immunity. We also estimated the relative vaccine effectiveness of a bivalent compared to a monovalent vaccine both administered as second boosters accounting for time since the administration and previous natural immunity.

Methods

We conducted a population-based test-negative case–control study utilizing Electronic Health Records from the Luxembourg Microdata Platform on Labour and Social Protection. In compliance with the specific COVID-19 legislation, we combined pseudonymized data from three national register-based sources, achieving complete (100%) population coverage [16]. The vaccination database contained detailed information about date and type of vaccines received. Luxembourg’s Social Security database contained sociodemographic information, including age group, sex, residency in long-term care facilities (LTCF). Data on positive and negative tests were extracted from the reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) SARS-CoV2 tests database that contained date and result of all tests performed in Luxembourg.

Inclusion exclusion criteria

For the selection of cases, we considered all ≥60 years old residents with at least one RT-PCR positive test for SARS-COV-2 between 26 September 2022, through 2 April 2023. For the selection of controls, we considered all ≥60 years old residents with at least one RT-PCR negative but no positive test for SARS-COV-2 during the same period. The date of the first positive tests for the cases and the negative tests for the controls during this period was defined as the reference date. All cases and controls with at least one positive test <90 days before the reference date were excluded. Cases and controls were matched on the week of the test. They were included only if the test was ≥14 days from second booster dose or if they were unvaccinated, i.e. if no vaccination record was found in the vaccination data base. The post injection 14 days interval was used to allow enough time for biological protection [Reference Munro17, Reference Amirthalingam18]. Inclusion was limited to unvaccinated individuals or those who had received two booster doses, where the first booster was monovalent and the second was monovalent or bivalent.

Study variables

Reinfection was defined according to the World Health Organization criteria [19]. An individual was considered as reinfected if he had two consecutive positive tests at least 90 days apart [Reference Yahav20]. Participants were categorized into three groups: not previously infected if no prior positive test, one prior infection and two or more prior infections. The two last groups were further subdivided based on the time since the last infection. Since 27 December 2021, 9 months before the beginning of the study period, Omicron variants accounted for at least of 75% of sequenced cases. Therefore, all infections occurring 4–8 months before the reference date were considered as Omicron-related. Vaccination status was categorized as unvaccinated, PSV + 2 monovalent, and PSV + 2 bivalent booster vaccines. The latter two groups were further subdivided based on the time since receiving the second booster, ranging from one to 6 months or more for the monovalent boosters and up to 5 months or more for the bivalent boosters. The total number of SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR tests per participant, conducted from the start of the epidemic in March 2020 until the reference date, was categorized into four groups (1–5, 6–9, 11–15, and ≥ 16).

To assess the relative effectiveness of a bivalent booster, we excluded unvaccinated individuals, calculated the number of months since the last dose was administered and categorized vaccination status into two groups: PSV + 2 bivalent and PSV + 2 monovalent using the later as reference category.

Statistical analysis

Conditional logistic regression was used to estimate the crude and adjusted odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). The covariates adjusted for were, age group (60–69, 70–79, 80–89, and ≥90 years old), sex, natural immunity, number of tests, and long-term care facility residency. Departure from linear trend was tested using a likelihood ratio test. Sub-group analyses were conducted based on prior infection status, dividing participants into two groups: those with no history of infection and those who were previously infected. A sensitivity analysis was conducted by excluding participants with more than 15 tests and subsequently those with more than 10 tests from the start of the epidemic in March 2020 until the reference date.

VE was calculated with the following formula: [(1 − OR) × 100] (%) using the unvaccinated group as reference for the absolute VE and the PSV + 2 monovalent for the relative VE. Effectiveness of natural immunity was calculated using the same formula with never previously infected as reference. For the sub-group analysis among previously infected individuals the category ‘one previous episode of infection 15–25 months ago’ was used as reference. A positive estimate of vaccine- or naturally acquired-immunity effectiveness was considered statistically significant if its 95% CI did not include zero, which is equivalent to a p value <0.05, indicating evidence of protection relative to the reference category. Analyses were conducted using Stata (16.0, StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX).

Results

Characteristics of the study population

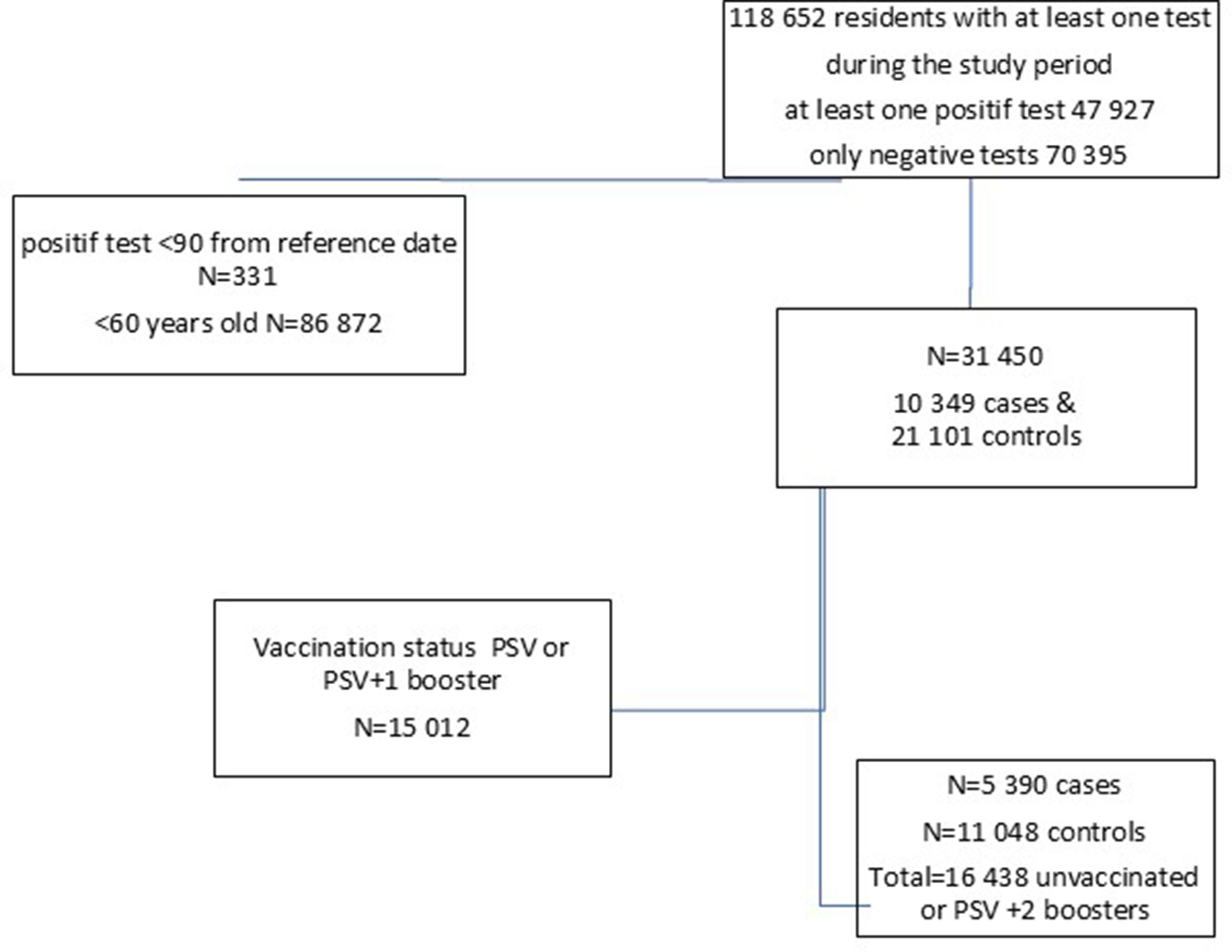

The vaccination coverage for PSV plus two boosters among individuals aged ≥60 years increased from 45% on 22 September 2022, to 50% by 7 December 2022, after which it remained stable, with 9% still unvaccinated (Figure 1). Between 22 September 2022, and 2 April 2023, a total of 118,652 residents underwent RT-PCR SARS-CoV2 testing with 47,927 (40.4%) testing positive at least once (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Cumulative vaccine uptake (%) among adults ≥60 years old in Luxembourg until April 2023.

Figure 2. Data flow with the number of cases and controls, included in the study, Luxembourg, 26 September 2022–2 April 2023.

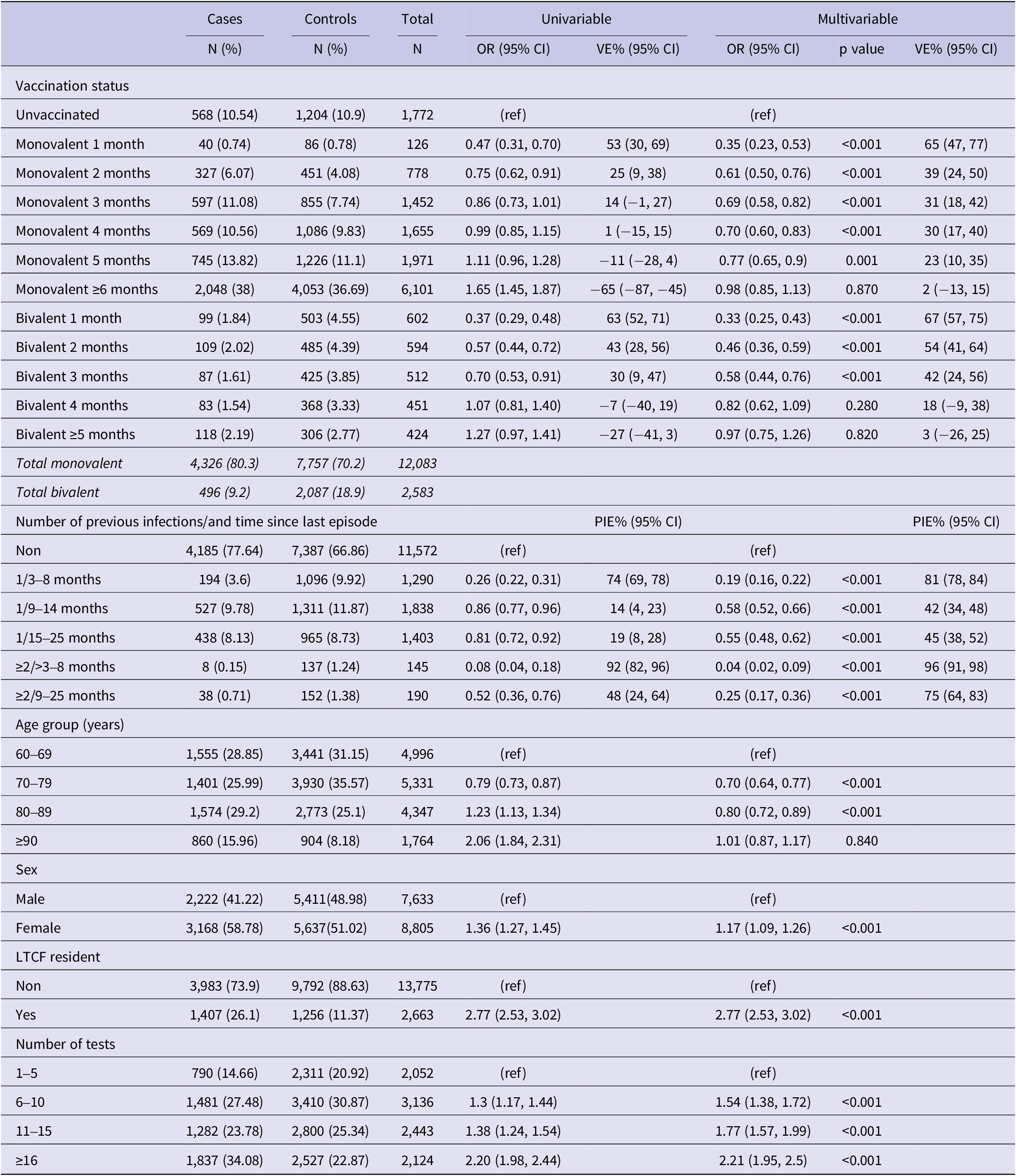

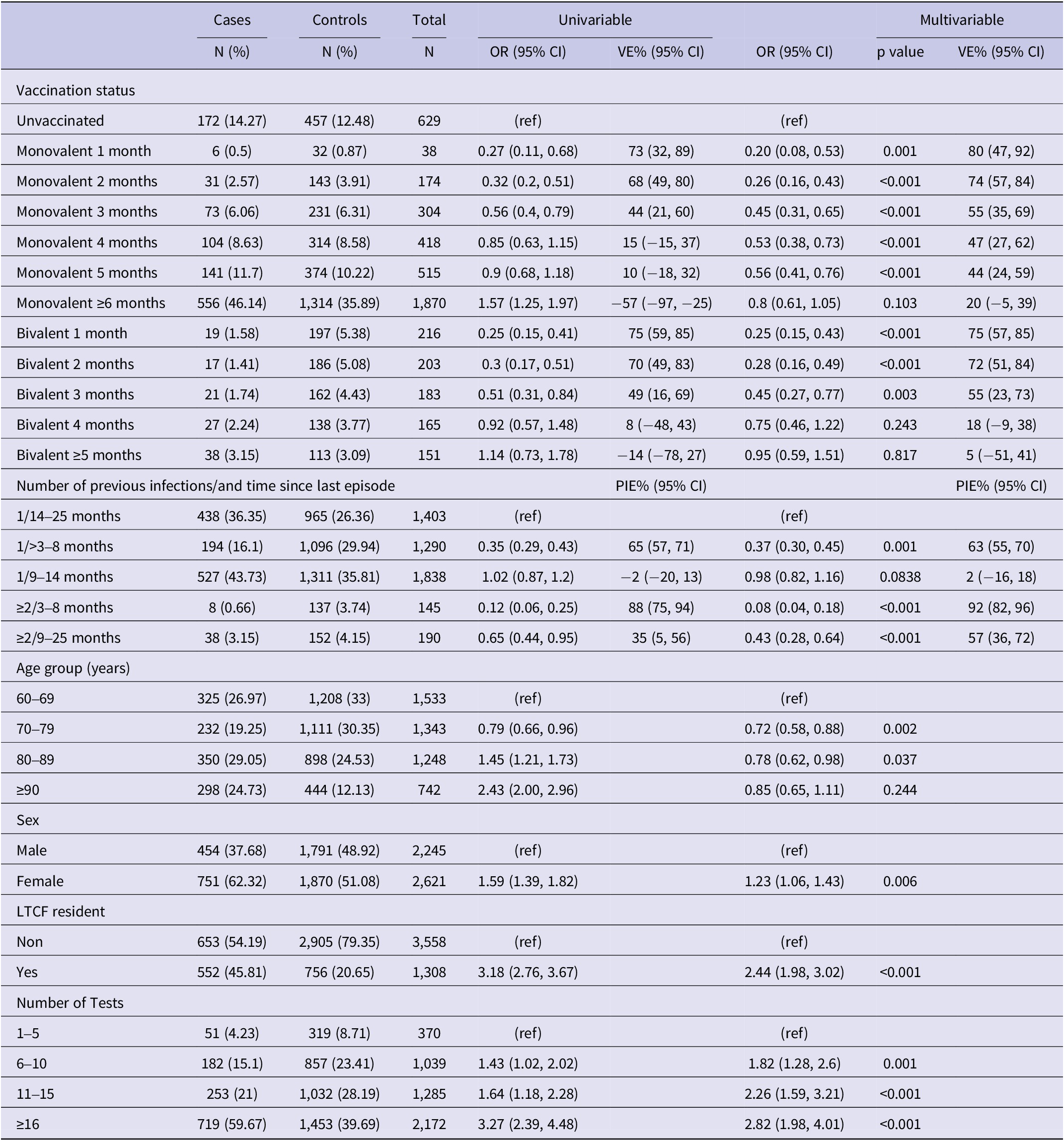

We excluded residents under 60 years of age (N = 86,872), those who tested positive within 90 days of the reference date (N = 331), and those with PSV or PSV + 1 (N = 15,012). A total of 16,438 individuals, 5,390 cases and 11,048 controls (Figure 2), with a median age of 77.5 (interquartile range (IQR): 67.5–82.5) years, and 53.6% females were included in the study. Among the study participants, 12,083 (75.3%) had received a monovalent PSV + 2 booster, 2,087 (12.7%) had received a bivalent PSV + 2 booster, and 11,572 (70.4%) had no prior history of infection. Among cases 4,326 (80.3%) had received a monovalent, 496 (9.2%) a bivalent PSV + 2 booster and 4,185 (77.4%) had no previous infection with respective figures being 7,757 (70.2%), 2,087 (18.9%), and 7,387 (66.9%) for controls (Table 1). Descriptive statistics and the results of the conditional regression for absolute VE are summarized in Table 1 for all participants, while Tables 2 and 3 provide the findings from the subgroup analyses.

Table 1. Results of univariable and multivariable conditional logistic regression for infection by vaccination status and natural immunity (N = 16,438), Luxembourg, 26 September 2022–2 April 2023

Note: Multivariable analysis adjusted for previous infection, age-group, sex, LTCF residency and number of tests, (ref) reference category.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; LTCF, long-term care facility; OR, odds ratio; PIE, previous infection effectiveness; VE, vaccine effectiveness.

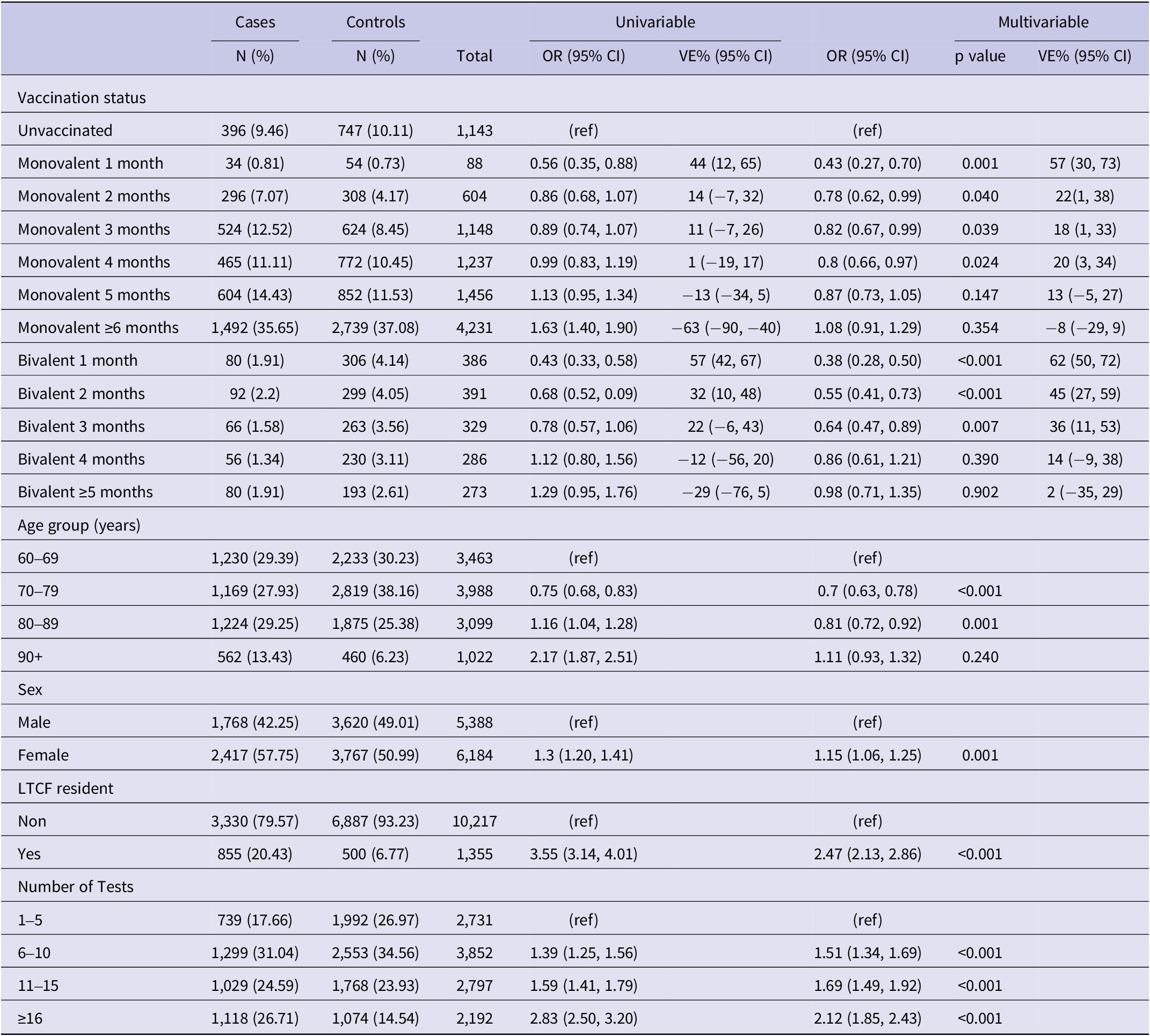

Table 2. Results of univariable and multivariable conditional logistic regression for infection by vaccination status among not previously infected individuals (N = 11,572), Luxembourg, 26 September 2022–2 April 2023

Note: Multivariable analysis adjusted for previous infection, age-group, sex, LTCF residency and number of tests.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; LTCF, long-term care facility; OR, odds ratio; VE, vaccine effectiveness, (ref) Reference category.

Table 3. Results of univariable and multivariable conditional logistic regression for infection by vaccination status and natural immunity among previously infected individuals (N = 4,866). Luxembourg, 26 September 2022–2 April 2023

Note: Multivariable analysis adjusted for previous infection, age-group, sex, LTCF residency and number of tests.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; LTCF, long-term care facility; OR, odds ratio; VE, vaccine effectiveness, (ref) reference category.

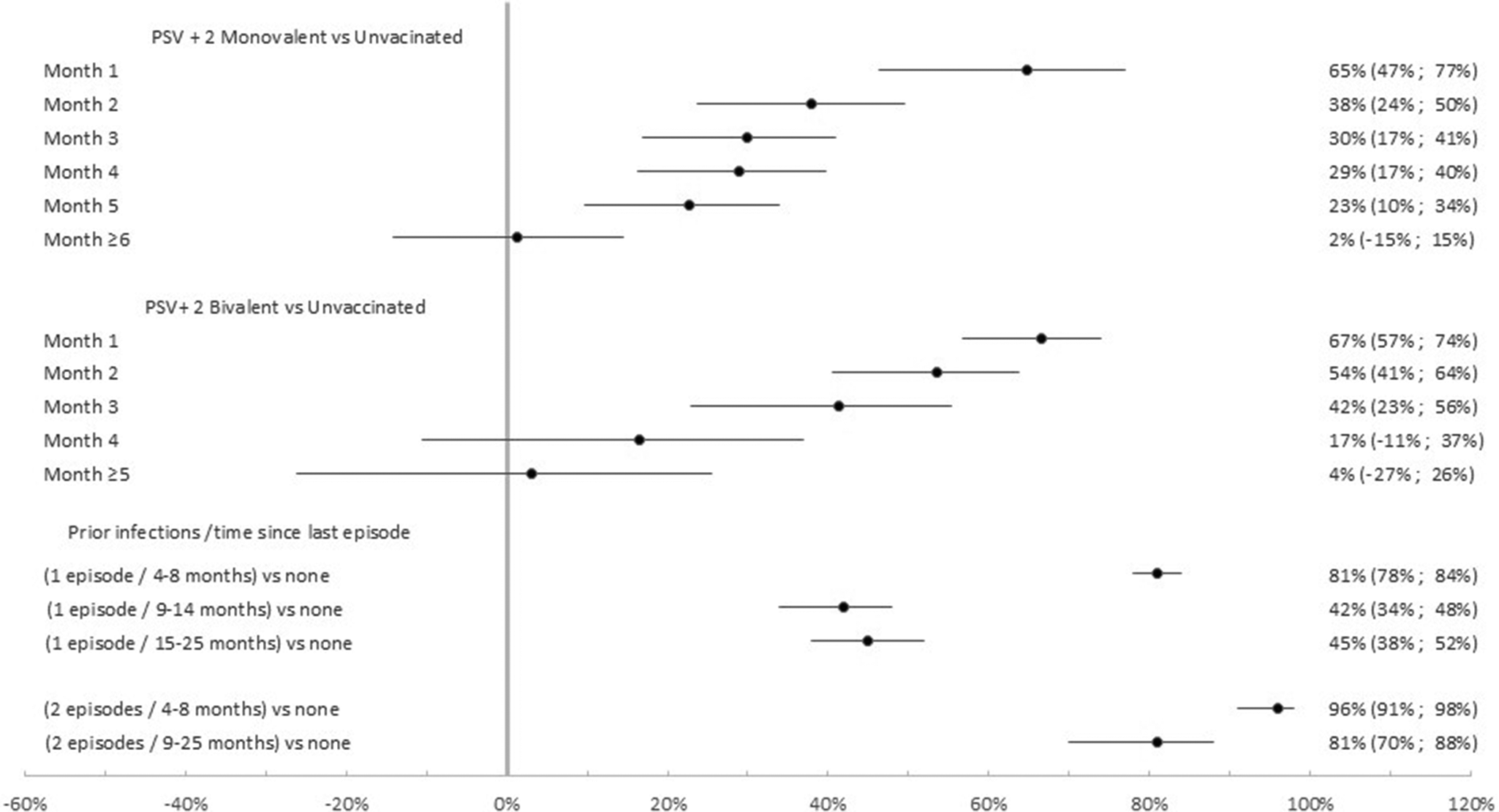

Absolute vaccine effectiveness

Compared to no vaccination, the effectiveness of the PSV + 2 monovalent boosters against Omicron infection were 64.8% (95% CI: 46.3%, 76.9%; p < 0.001) in the first month, 23.0% (95% CI: 10.0%, 34.1%; p = 0.001) in the fifth month, and 1.5% (95% CI: −14.7%, 13.8%; p = 0.87) six or more months after administration (Figure 3). The respective VE for the bivalent boosters was 66.6% (95% CI: 57.0%, 74.1%; p < 0.001) in the first month and 16.5% (95% CI: −10.5%, 36.9%; p = 0.82) five or more months after administration.

Figure 3. Monovalent and bivalent vaccine effectiveness and natural immunity protection against infection. All cases and controls (N = 16,438), Luxembourg, 26 September 2022–2 April 2023.

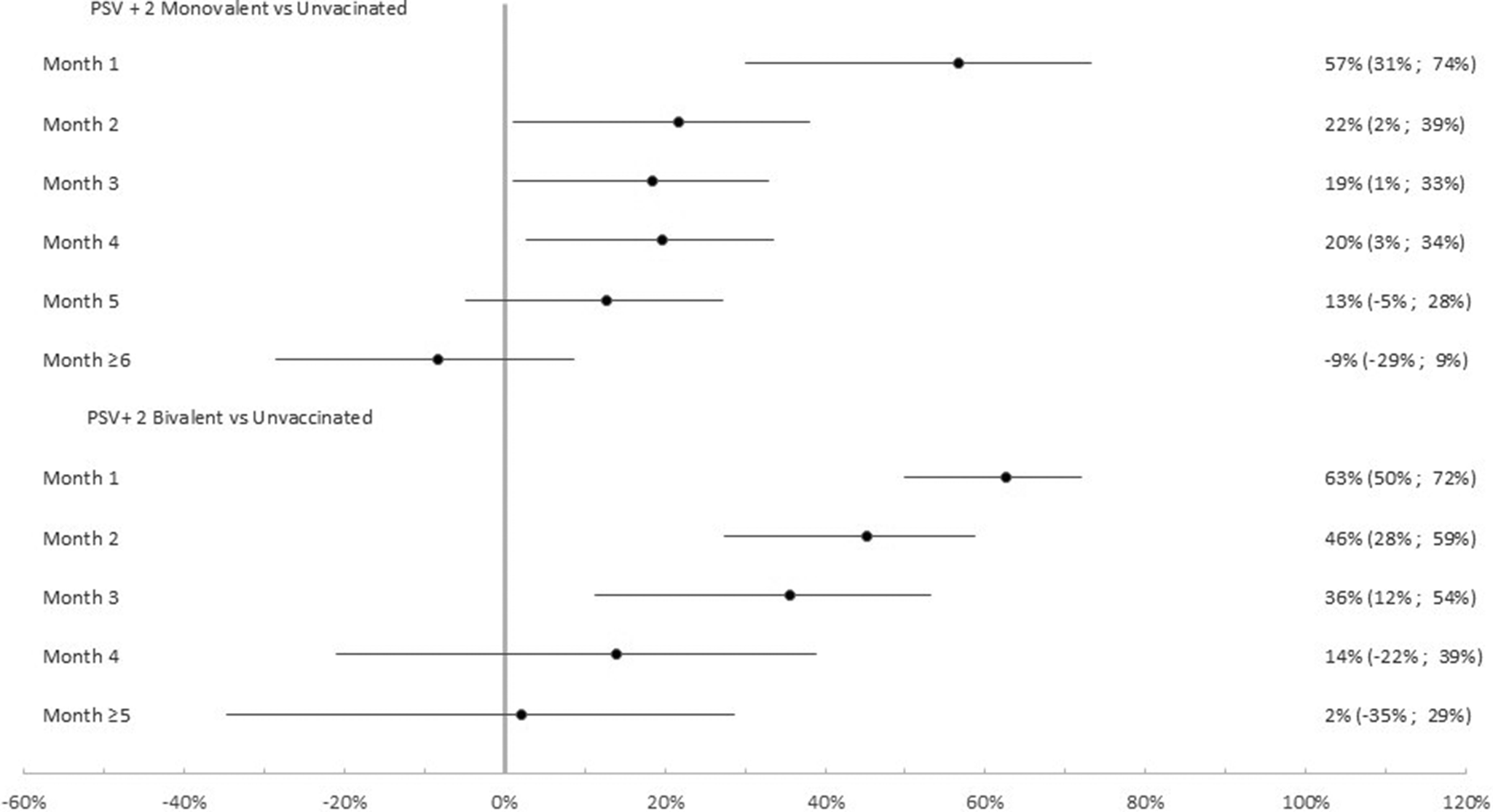

Among the 11,572 participants with no previous infection VE of the PSV + 2 monovalent boosters were 56.7% (95% CI: 30.2%, 73.2%; p < 0.01) in the first month, 21.8% (95% CI: 1.1%, 38.1%; p < 0.05) in the second month, 12.7% (95% CI: −4.9%, 27.3%; p = 0.15) in the fifth month after administration (Figure 4). The respective VE for the bivalent boosters was 62.5% (95% CI: 49.9%, 71.9%; p < 0.001), 45.3% (95% CI: 27.5%, 58.7%; p < 0.001), and 13.9% (95% CI: −21.1%, 38.8%; p = 0.39).

Figure 4. Monovalent and bivalent vaccine effectiveness against infection. Subgroup analysis among non-previously infected cases and controls (N = 11,572), Luxembourg, 26 September 2022–2 April 2023.

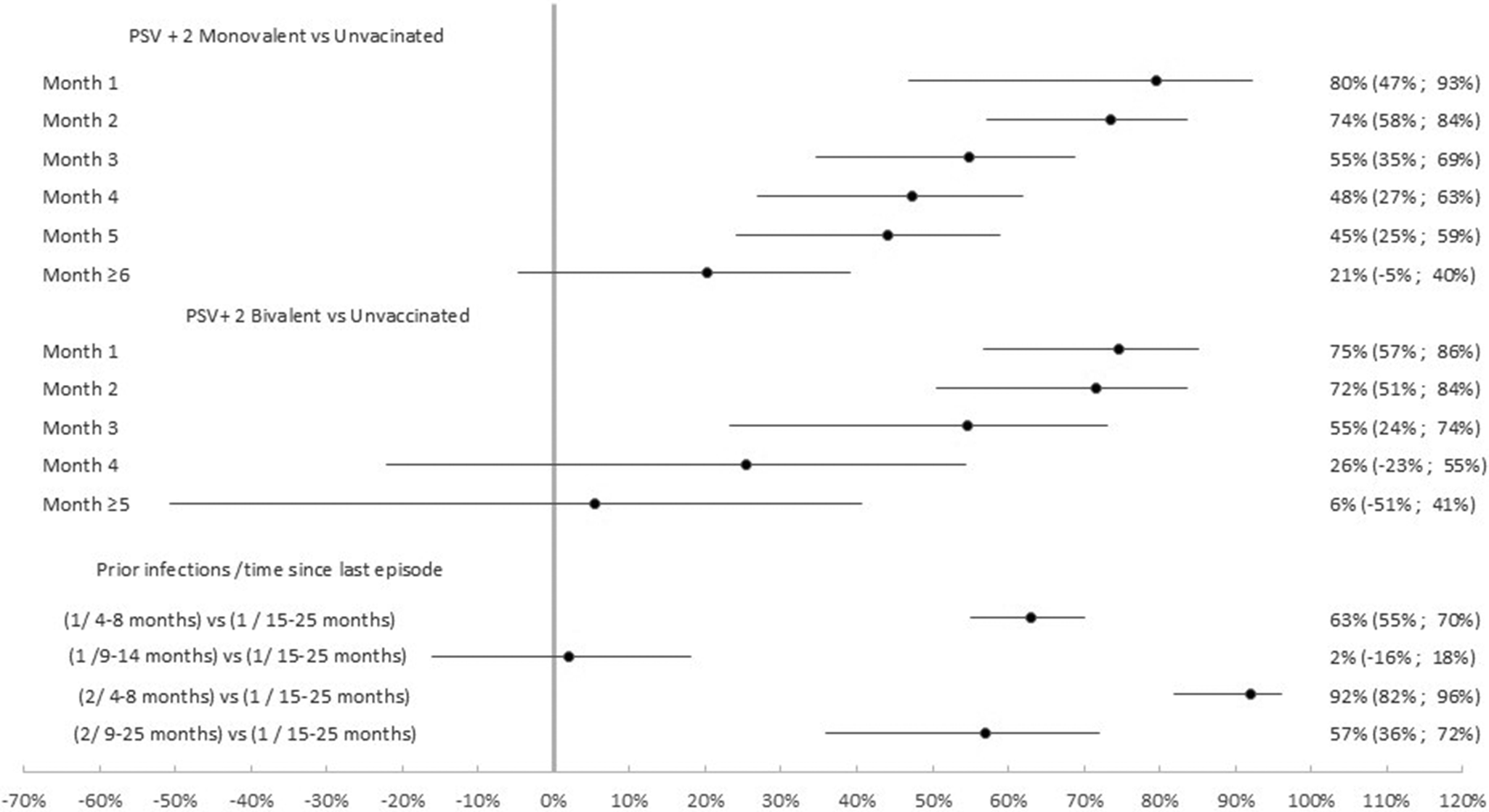

Among the 4,866 participants with at least one previous infection the effectiveness of the PSV + 2 monovalent boosters against Omicron infection was 79.6% (95% CI: 47.0%, 92.2%; p = 0.001) in the first month, 73.6% (95% CI: 57.2%, 83.7% p < 0.001) in the second month, and 20.2% (95% CI: −4.7%, 39.2% p = 0.10) ≥6 months after administration (Figure 5). The respective VE for the bivalent boosters was 74.7% (95% CI: 50.5%, 83.7%; p < 0.001), 71.6% (95% CI: 50.5%, 83.7% p < 0.001), and 5.3% (95% CI: −50.8%, 40.6% p = 0.82) ≥5 months after administration.

Figure 5. Monovalent and bivalent vaccine effectiveness and natural immunity protection against infection. Subgroup analysis among previously infected cases and controls (N = 4,866), Luxembourg, 26 September 2022–2 April 2023.

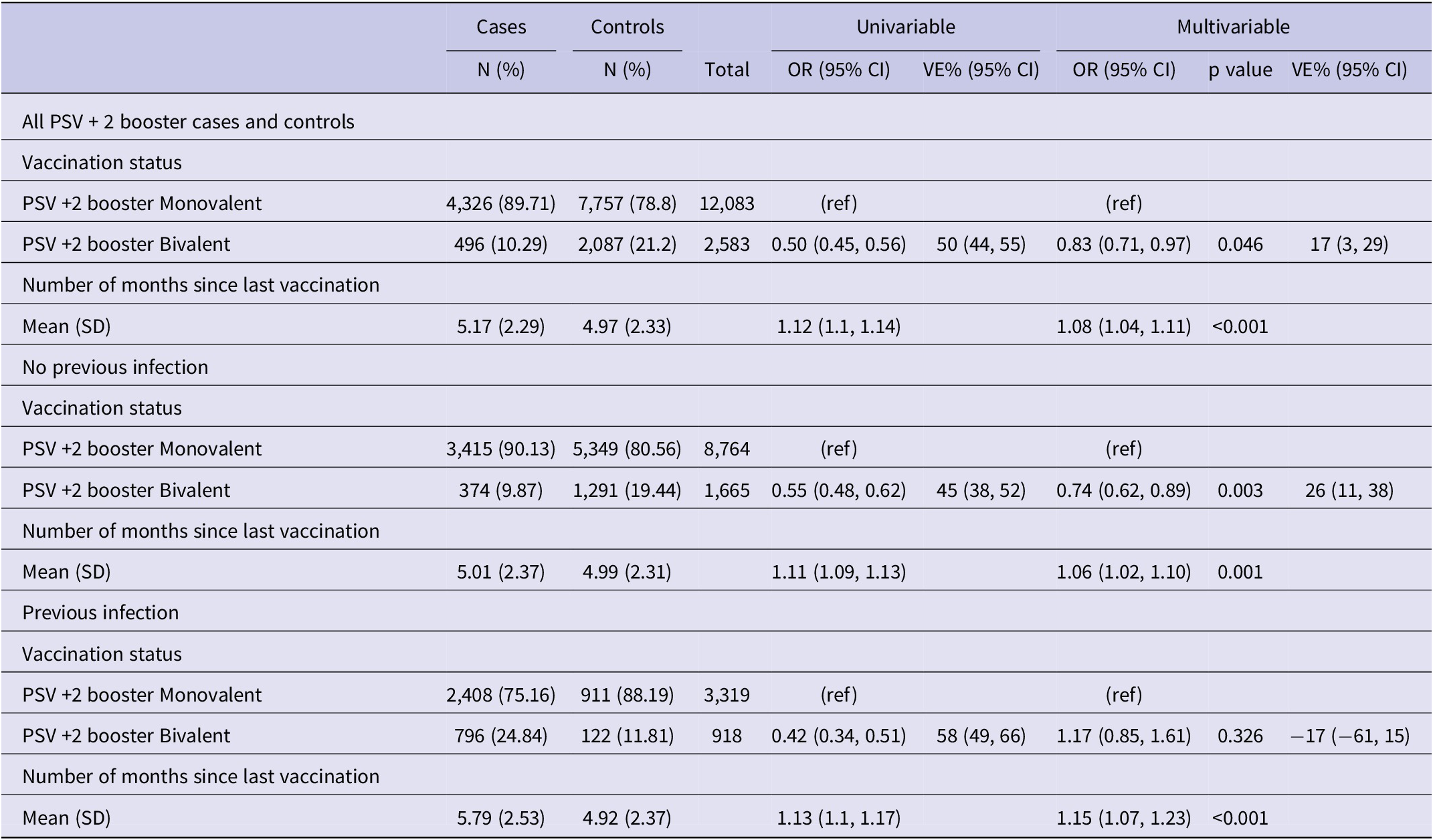

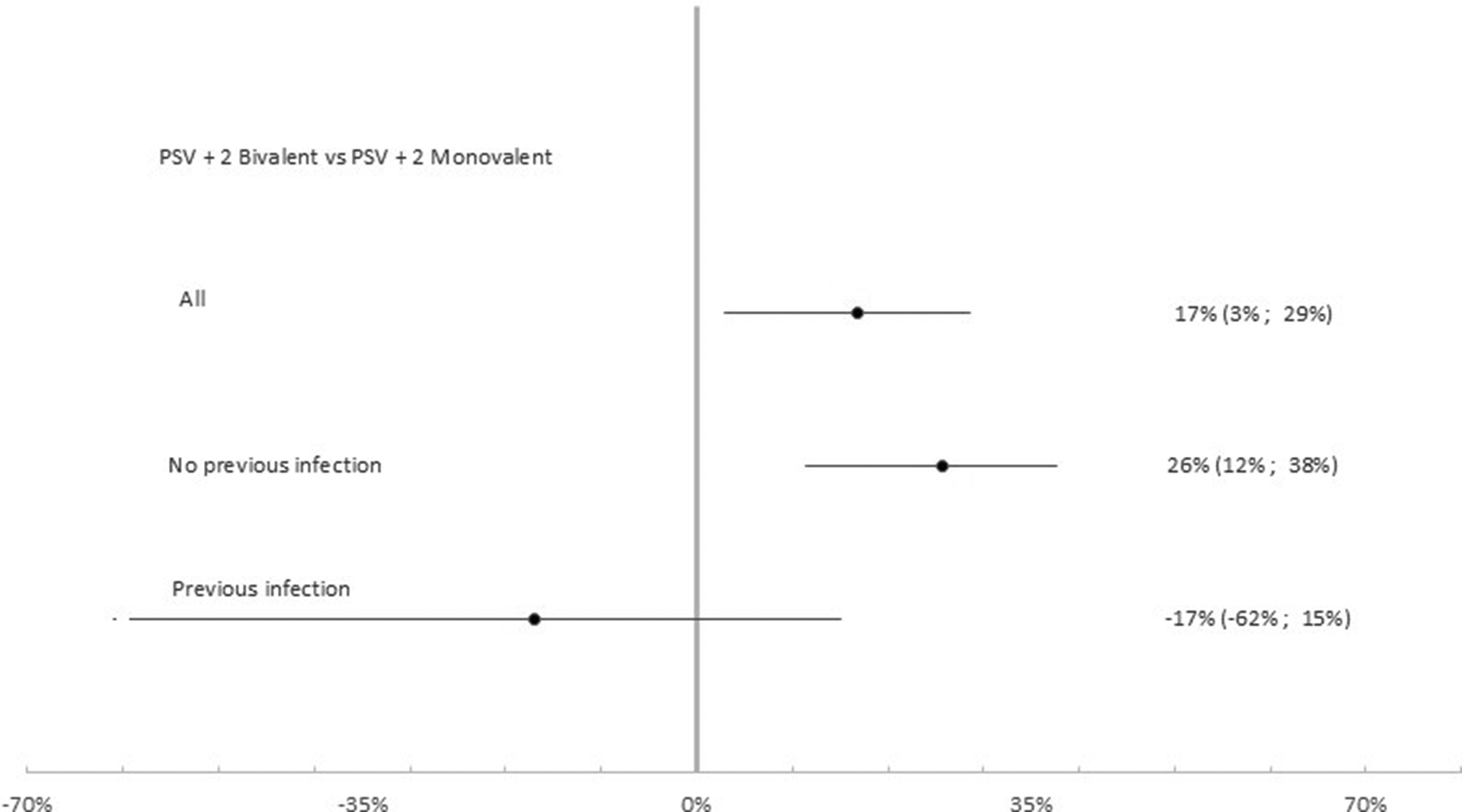

Relative vaccine effectiveness

Table 4 summarizes results for relative VE. Among the 14,666 participants that had received the second booster the effectiveness of the PSV + 2 bivalent compared to the monovalent booster was 16.8% (95% CI: 2.9%, 28.6%; p < 0.05). Relative VE was −16.9% (95% CI: −61.1%, 15.0%; p = 0.326) among the 4,237 previously infected and 25.7% (95% CI: 11.4%, 37.7%; p < 0.01) among the 10,429 participants that had never experienced a previous infection (Figure 6).

Table 4. Results of univariable and multivariable conditional logistic regression comparing PSV +2 booster bivalent versus PSV +2 booster monovalent against infection

Note: Subgroup analysis among previously infected (N = 4,237), not previously infected (N = 10,429) and all (N = 14,666) cases and controls. Luxembourg, 26 September 2022–2 April 2023. Multivariable analysis adjusted for previous infection, age group, sex, LTCF residency and number of tests.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; LTCF, long-term care facility; OR, odds ratio; PIE, previous infection effectiveness; VE, vaccine effectiveness, (ref) Reference category.

Figure 6. Relative vaccine effectiveness of PSV +2 booster bivalent versus PSV +2 booster monovalent against infection. Subgroup analysis among previously infected (N = 4,237), not previously infected (N = 10,429) and all (N = 14,666) cases and controls. Luxembourg, 26 September 2022–2 April 2023.

Natural immunity

Compared to uninfected individuals, natural immunity effectiveness was 80.7% (95% CI: 77.1%, 83.8%; p < 0.001) for only one infection occurring 4–8 months prior, 41.2% (95% CI: 38.6%, 48.0%; p < 0.001) for 9–14 months prior, and 44.9% (95% CI: 37.1%, 51.8%; p < 0.001) for 15–25 months prior (Figure 3). For individuals with two or more prior infections, the effectiveness rates were 95.4% (95% CI: 90.3%, 97.8% p < 0.001) if the last episode was 4–8 months previously and 80.8% (95% CI: 69.7%, 87.8%; p < 0.001) if 15–25 months previously.

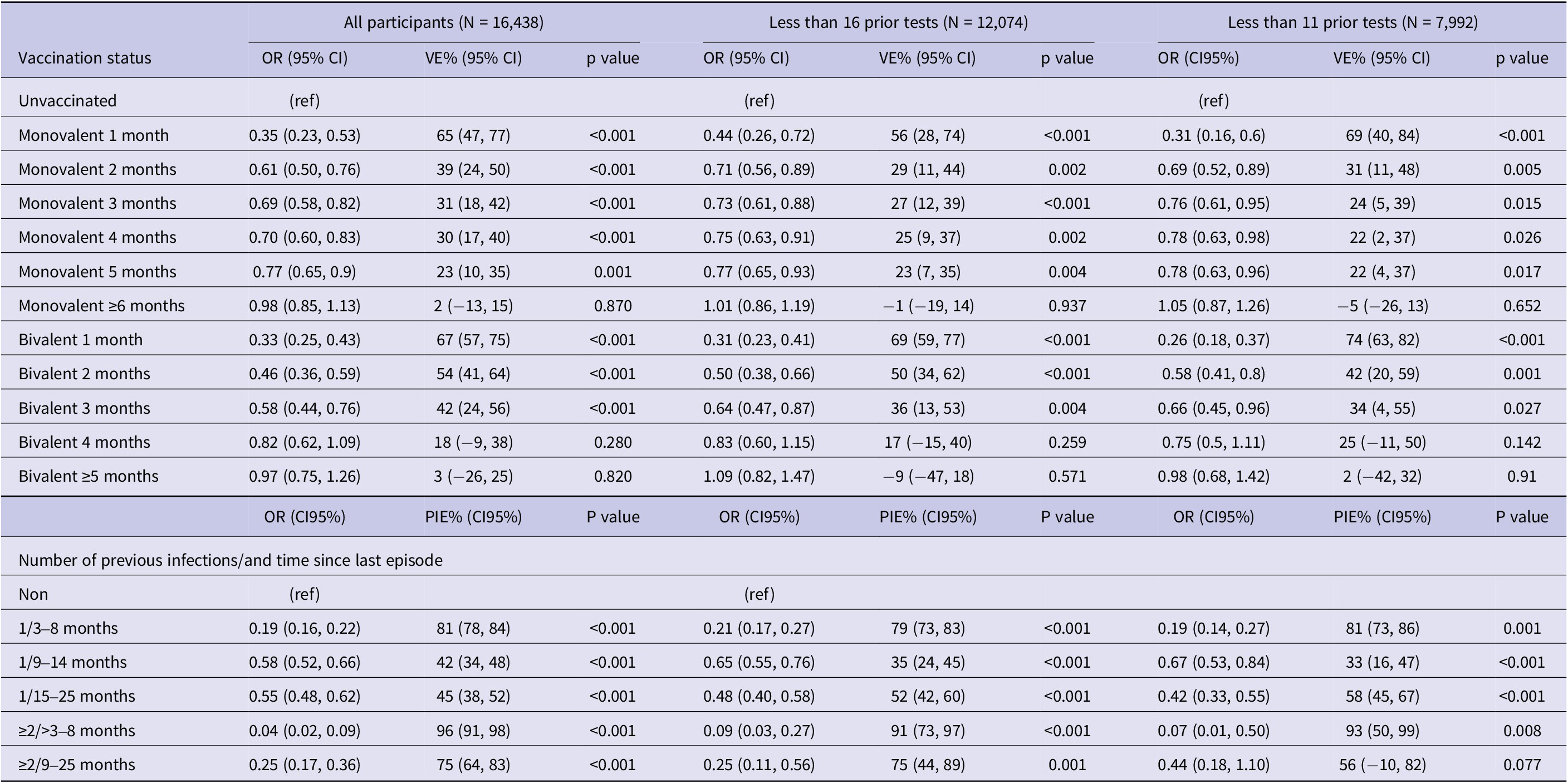

Sensitivity analysis

The results of the sensitivity analysis are summarized in Table 5. Among the 7,992 participants with less than 11 RT-PCR tests since the beginning of the epidemics the effectiveness of the PSV + 2 monovalent boosters against infection was 69.4% (95% CI: 40.5%,84.2%; p < 0.001) in the first month, 22.7% (95% CI: 4.5%, 37.5%; p = 0.017) in the fifth month, and −5.0% (95% CI: −25.9%, 13.4%; p = 0.65) six or more months after administration (Table 5). The respective VE for the bivalent boosters was 74.9% (95% CI: 63.1%, 82.9%; p < 0.001) in the first month and 2.1%% (95% CI: −41.1%, 32.0%; p = 0.91) five or more months after administration.

Table 5. Results of multivariable conditional logistic regression for infection by vaccination status and natural immunity, sensitivity analyses in the full sample (N = 16,438) and in subgroups with <16 (N = 12,074) and < 11 (N = 7,992) prior tests since the beginning of the pandemic, Luxembourg, 26 September 2022–2 April 2023

Note: Multivariable analysis adjusted for previous infection, age-group, sex, LTCF residency and number of tests.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; LTCF, long-term care facility; OR, odds ratio; VE, vaccine effectiveness, (ref) reference category.

Natural immunity effectiveness was 81.1% (95% CI: 73.1%–86.7%; p < 0.001) for individuals with a single infection occurring 4–8 months prior, and 58.2% (95% CI: 45.8%–67.7%; p < 0.001) for those whose infection occurred 15–25 months prior. For individuals with two or more prior infections, effectiveness was 93.4% (95% CI: 50.4%–99.1%; p < 0.001) if the last episode occurred 4–8 months previously, and 56.5% (95% CI: −9.3%–82.6%; p = 0.077) if 15–25 months previously (Table 5).

Discussion

Our study suggests that both monovalent and bivalent PSV + 2 boosters targeting Omicron variants BA.1 and later BA.4/BA.5 provided temporary protection against infection. Their effectiveness peaked within the first month following administration but declined over time, with protection lasting no longer than 4 to 6 months. Among not previously infected individuals the protection conferred by monovalent vaccines declined rapidly in the second month whereas bivalent vaccines provided marginally better protection. In contrast, natural immunity offered high levels of protection that persisted for more than 14 months, demonstrating both greater strength and longer duration compared to vaccine-induced immunity.

In a previous study, we found that PSV + 2 boosters were 71.6% effective in preventing hospital admission and 76.2% effective in preventing death [Reference Bejko21]. These findings were based on data from a cohort of 187,143 SARS-CoV-2-infected cases between December 2021 and March 2023, with adjustments for the variant predominance period, including the post-BA.5 era relevant to this study. Even though the monovalent and bivalent Omicron BA.1 and BA4/BA5 PSV + 2 boosters provide protection against infection that declines with time and lasts no longer than 6 months, they shield infected individuals from severe illness. Furthermore, this protection benefits not only individuals but also the broader population. Other studies have reached similar conclusions, with some highlighting the additional protection provided by bivalent vaccines against severe disease among elderly individuals [Reference Stecher22, Reference Surie23] and some estimating that the protection effect is similar for bivalent and monovalent boosters [Reference Grewal24, Reference Chatzilena25].

Our estimates align with a Dutch study, which reported a relative VE of 14% against infection in individuals aged 60–85 for the bivalent BA.1 vaccine [Reference Huiberts9]. However, they are lower than the 42.4% VE reported in a South Korean study focusing on individuals aged 18 and older without prior infection. This discrepancy may be attributed to differences in follow-up duration, as the South Korean study assessed protection only up to 68 days post-vaccination [Reference Kim8]. Both studies documented waning immunity over time. Similarly, a recent U.S. study found that BA.4/BA.5 bivalent vaccines provided short-term protection against BA.4/BA.5 and XBB Omicron variants, with effectiveness declining significantly after 2 months and nearly absent beyond 4 months [Reference Ackerson26]. It is important to note that in these studies reference groups for relative VE estimates mainly included individuals previously vaccinated with PSV or PSV + 1, with only a limited number receiving PSV + 2 monovalent boosters. A Japanese cohort study estimated a 56% relative VE among 65+ years but used a follow-up time of no longer than 2 months (11,12). A French study comparing the concomitant use of monovalent and bivalent boosters among older adults estimated a relative VE of 8%, which is comparable to our estimate of 16%. The study also reported that prior infection with recent variants conferred strong protection, estimated at 74%, but it did not provide relative VE estimates stratified by prior infection status [Reference Auvigne10].

Additionally, it has been reported that BA.1 and BA.5 bivalent vaccines increased neutralizing antibodies and T-cell responses for up to 3 months post-booster but exhibited poor cross-neutralization against the XBB.1.5 variant [Reference Zaeck27]. Genomic surveillance data from Luxembourg, covering over 10% of community RT-PCR-positive cases, revealed that circulating variants between November 2022 and March 2023, were predominantly BQ1 and XBB recombinants (https://lns.lu/revilux; accessed on 26 July 2023).

The superior and longer-lasting protection against infection and severe disease provided by natural immunity compared to vaccination has been widely reported [Reference Uusküla28, Reference Nordström, Ballin and Nordström29]. Natural immunity has been associated with a 95% reduction in reinfection risk and an 87% lower risk of COVID-19 hospitalization, with protection lasting up to 20 months [Reference Nordström, Ballin and Nordström29]. Our findings similarly indicate that individuals previously infected during the Omicron era maintained high levels of protection for up to 8 months during the BQ1 and XBB recombinant predominance period. Although protection from natural immunity gradually declined 9 to 25 months following a single infection, it remained strong after the most recent episode of multiple infections.

This durable protection can be attributed to the broader and more robust immune response elicited by natural infection. Unlike vaccination, which primarily targets the spike protein, natural infection exposes the immune system to the entire virus, thereby stimulating antibodies and T-cells directed at multiple viral antigens. It also induces stronger T-cell memory, particularly CD8+ cytotoxic T-cells, which are crucial for long-term protection and less susceptible to immune escape from spike protein mutations. Additionally, symptomatic infections typically involve higher and longer antigen exposure, leading to stronger and more durable immune responses. Natural infection also triggers mucosal immunity, including IgA production in the respiratory tract, which contributes to blocking viral entry at the site of infection [Reference Sette and Crotty30–Reference Russell32]. Neutralizing antibodies generated by prior COVID-19 infections persist for up to 16 months, though their activity diminishes over time. On the other hand, antibodies generated by vaccines wane within 5 to 7 months (26).

We observed negative relative VE among previously infected individuals although this finding was not statistically significant. Behavioural confounding could explain the observation, since previously infected individuals who received a bivalent booster might have engaged in higher-risk behaviours.

There are limitations to this study that must be acknowledged. As an observational, real-world study on vaccine effectiveness, residual confounding remains a concern [Reference Obel33]. Individuals who were immunocompromised or had other comorbidities were prioritized for vaccination. However, we lacked information on comorbidities, introducing potential confounding by indication, which may have led to an underestimation of vaccine effectiveness. We lacked symptom data in our testing database but given the absence of widespread contact tracing or large-scale testing initiatives and the availability of antigenic tests during the study period, it is reasonable to assume that most individuals tested in a laboratory by RT-PCR exhibited respiratory symptoms [34]. However, comparable estimates of vaccine effectiveness (VE) against hospitalization have been reported using test-negative symptomatic and test-negative asymptomatic controls (17). The potential for misclassification bias due to testing asymptomatic individuals may still persist and could be differential among vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals if the vaccine reduces symptoms of the disease [Reference Lewnard35].

Vaccinated individuals who become infected are more likely to experience mild or no symptoms and, as a result, may not seek testing and be included in the study as a case, potentially leading to a VE overestimation. Additionally, prior infections may go undiagnosed, resulting in misclassification of exposure. This misclassification may bias comparisons and further contribute an overestimation of VE. We expect limited effect on the estimate of the protection conferred by natural immunity, given that symptomatic COVID-19 infection induces a stronger and longer-lasting immune response – both in antibodies and T-cell memory – compared to asymptomatic infection (10,11).

Since all individuals included were alive at the time of testing, we may have missed infected individuals who died before they could be tested. Considering protection against death conferred by the vaccine [Reference Bejko21, Reference Tenforde36], unvaccinated infected individuals would be more likely to be excluded from the study sample, potentially leading to an underestimation of VE. Individuals with high health-seeking behaviours are more likely to be vaccinated and less likely to develop severe disease. Furthermore, they are also more likely to undergo frequent testing and to be diagnosed if infected, which may bias vaccine effectiveness (VE) estimates. We anticipate that by including only individuals who were tested, health-seeking behaviour is similar between cases and controls. Furthermore, we adjusted the analysis for the number of SARS-CoV-2 tests conducted during the three-year period since 2020 to control for residual confounding. In a separate sensitivity analysis, participants with more than 15 tests and subsequently those with more than 10 tests were excluded. Both analyses yielded estimates of protection conferred by natural immunity and vaccination that were consistent with the primary analysis [Reference Shi, Li and Mukherjee37].

Finally, the number of participants was relatively low in certain subcategories, including those who received the bivalent booster four or more months earlier in the subgroup analyses or those with two or more prior infections in the sensitivity analyses. As a result, the corresponding confidence intervals were wide, suggesting that the study may have been underpowered to detect statistically significant differences for these subgroups.

Strengths

Our study was based on COVID ad-hoc comprehensive data base that during the study period captured all vaccinations, tests, and severe outcomes at national level.

We matched cases and controls on the week of the test to control for circulating levels of the virus in the community that in its turn affects both vaccination and testing.

Conclusion

Among adults aged 60 years and older, both monovalent and bivalent COVID-19 boosters provided temporary protection against Omicron infection. Natural immunity provided longer-lasting and more robust protection. Compared to monovalent, bivalent boosters provided marginally better protection for not previously infected individuals. These findings should be considered in light of conclusions from studies on effectiveness against severe COVID-19, including ours, which showed that booster regimens – particularly PSV + 2 boosters – offered strong protection [Reference Bejko21]. Further work needs to identify the role and the target groups for any additional booster doses tailored to the emerging variants in the future.

Data availability statement

Data were provided by the General Inspectorate of Social Security through the Luxembourg Microdata Platform on Labour and Social Protection. Information on data access modalities can be found at the following link: https://igss.gouvernement.lu/fr/microdata-platform.html.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the General Inspectorate of Social Security for providing data for analysis through the Luxembourg Microdata Platform on Labour and Social Protection. During the preparation of this work the authors used artificial intelligence (AI), specifically OpenAI’s ChatGPT to improve scientific writing in English. After using this tool, the author(s) reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Author contribution

DB, AV, JM, SS, and MZ contributed to the conception and design of the study. DB led the data analysis and was supported by JM, AV, SS, and MZ in interpretation. All authors contributed to the study recommendations, to drafting the article, and provided final approval for the submitted version.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.