…birds act as barometers for planetary health,

allowing us to ‘take the pulse of the planet’.

(BirdLife International 2022:15)

…what appears depends on one’s point of view.

(Sara Ahmed Reference Ahmed2006:12)

Introduction

Halfway up Jebel Shams, the highest mountain in the Sultanate of Oman, the ground drops suddenly away in a great cleft of rock and tumbling slope. The vast canyon is a cross-section of forty-five million years of tectonic shift and a dramatic testament to the power of running water, today found in ever-shrinking quantities throughout the Arabian Peninsula. It is also an increasingly popular tourism destination. Visitors from other parts of Oman and around the world hike the Balcony Walk, a trail that proceeds below the canyon rim to an abandoned village and—if one knows where to look—a cave overlooking a pool of water, the immense silence of the landscape broken only by the occasional bleating of domestic goats (Figure 1). As Oman attracts more tourists than ever, the canyon has earned the moniker—repeated by Omanis, residents, and tourists, and canonized in Lonely Planet (Walker, Lee, Bremmer, Hussain, & Quintero Reference Walker, Lee, Bremmer, Hussain and Quintero2019:316)—of the ‘Grand Canyon of Arabia’.

Figure 1. A goat stands on an outcrop at the ‘Grand Canyon of Arabia’, Sultanate of Oman (author’s photo, September Reference Sultana2022).

I have returned to this canyon many times over the course of a long-term research project on changing relations with nature. On one visit, in March 2023, I met with Ibrahim. We stood chatting as I drank the coffee he sold me from his trailside café, located on a level stretch of rocky slope next to the Balcony Walk trail and a few meters from where the ground pitches suddenly downward, not leveling again until the canyon’s nadir one thousand meters below. A resident of the nearby village from which the trailhead starts, Ibrahim launched his café that season, part of the rapidly expanding tourism trade in the region. Yet while tourism is about two decades old, people have been living in the canyon for centuries. They used to farm of course, Ibrahim told me, and his father used to hunt birds as well.

‘Did he stop because it’s prohibited?’ I asked.

‘No,’ Ibrahim shrugged. ‘Now there aren’t any birds.’

The immense silence of the canyon was not, it turns out, indicative of high-mountain nature. In alerting me to the absence of birds, Ibrahim drew my attention to a sign that changed the landscape. Rather than the redoubt of ‘pristine’ nature that most visitors interpret it to be, the Grand Canyon of Arabia was transformed into a space just as riddled with the complexities and troubles of any other in this era of planetary crisis. With the population of most bird species shrinking and one in eight faced with extinction (BirdLife International 2022), declining avian biodiversity indexes a global change that has left no landscape untouched in a time perhaps most comparable to the five great extinction events in Earth’s history. The world is witnessing what is likely the sixth (Kolbert Reference Kolbert2014) due to the Euro-American development of extractive systems that, beginning in the 1500s (Koch, Brierley, Maslin, & Lewis Reference Koch, Brierley, Maslin and Lewis2019), have become caught in planetary feedback loops of climate regulation resulting in a period of crisis widely described as the Anthropocene: the era in which human activity has altered planetary systems.Footnote 1

But how does one see the absence of birds? And why, like so many visitors to the Grand Canyon of Arabia, did I first interpret silence as a sign of remote nature?

As sociolinguistics confronts planetary crisis, the absence of birds provides a lens for two problems. The first concerns the planetary, or how Anthropocene-era changes urge new domains of sociolinguistic analysis. The study of discourse in space which has coalesced as semiotic landscape studies has been broadly concerned with ‘human intervention and meaning making’ (Jaworski & Thurlow Reference Jaworski and Thurlow2010:2), and the analysis of so-called ‘natural’ landscapes has generally been regarded as belonging to different fields of study. Recognizing that biodiversity decline is not ‘natural’ but indeed a human-made intervention in the landscape undercuts the modern bifurcation of society from ‘Nature’, revealing a relational entanglement with spaces typically regarded as separate from humans. Taking this and other posthuman provocations seriously invites semiotic landscape studies to understand space in ‘planetary’ terms, decentering humans as the sole agents of meaning-making (Chakrabarty Reference Chakrabarty2021).

The second problem is how the absence of birds or other more-than-human signs are noticed or become objects of attention. That signs of planetary crisis go so readily unmarked demands examination of how multiple interpretations of a landscape can arise, as attention is shown to be directed by signs and focused through discourse. This article follows recent sociolinguistic work reflecting the importance of attention (Borba, Fabrício, & Lima Reference Borba, Fabrício and Lima2022; Volvach Reference Volvach2024) to further demonstrate that the interpretation of signs in space hinges on semiotic ideology (Keane Reference Keane2018) and orientation (Ahmed Reference Ahmed2006), suggesting the grounds through which a sociolinguistics of attention might take shape.

After developing theoretical perspectives on the planetary and on attention, I turn to the case of the Balcony Walk, a tourism site that is widely interpreted as ‘natural’ yet upon closer inspection is revealed to be replete with indexes of the Anthropocene. Drawing on ethnographic fieldwork including participant observation and interviews as well as public digital inscriptions from Google Maps and Instagram, the production of a semiotic ideology is demonstrated to focus attention on signs that confirm an ideological formation of ‘Nature’ separated from human society. The article’s final section considers what happens when this formation breaks down, and the ‘natural’ landscape is shown to be produced by both humans and more-than-human agents. The resulting disorientation in space presents a way forward into planetary crisis, as attunement to more-than-human signs and processes holds potential for generating relational alignments in a restive future.

Landscapes in crisis: From posthumanism to the planetary

The conviction that semiosis is something that only humans do rests on an ideological separation of Homo sapiens from other forms of life and ecologies, as ‘society’ is paradigmatically dichotomized from a non-human ‘Nature’ in modernity (Latour Reference Latour1993). Nature/society discourse (henceforth ‘Nature’) operates as a regime of truth which excludes its counterfactuals (cf. Foucault Reference Foucault and Rabinow1984). While still a hegemonic norm, this discourse is critically contested. ‘Nature’ has always been at odds with Indigenous concepts of relationality (Whyte Reference Whyte, Heise, Christensen and Niemann2017), which are becoming more widely recognized even as theories proliferate which reflect relationality without crediting Indigenous thinkers (Todd Reference Todd2016). In sociolinguistics, a turn to posthumanism ‘decenters’ humans as the sole protagonists of language analysis, recognizing that humans are connected to living and ostensibly non-living things in ways that shape languaging practices (Pennycook Reference Pennycook2017). Posthumanism informs the ‘assemblage’ concept of dispersed connection through the metaphor of the rhizome (cf. Deleuze & Guattari Reference Deleuze and Guattari1988), illustrating how each part in a heterogeneous whole is connected to the other in a subversion of paradigmatic dualism (Pennycook Reference Pennycook2024; Pietikäinen Reference Pietikäinen2024). Recent other-than-human sociolinguistic work has investigated the languaging practices of animals (Cornips Reference Cornips2022; Lamb Reference Lamb2024a) and spirits (Deumert Reference Deumert2022) and considered how human semiosis is shaped by material waste (Thurlow Reference Thurlow2022) and digital infrastructures (Gonçalves Reference Gonçalves2024).

While the study of linguistic and semiotic landscapes has largely focused on human-made signs in space, recent studies have pointed to how humans and ostensibly ‘natural’ landscapes are mutually implicated. Placards on nature trails have been shown to invoke the ‘presence’ of unseen fauna (Soica & Metro-Roland Reference Soica and Metro-Roland2024), while municipal signage is demonstrated to cultivate relations with more-than-human landscapes (Baiqi Reference Baiqi2025). Further unsettling ‘Nature’ is Gavin Lamb’s study of sea turtles and monk seals in Hawai‘i, where these animals’ meaning-making transforms the beachscape and alters how humans emplace signs. As he asks, ‘what human meaning-making has not been inscribed by the (more-than-human) landscape?’ (Lamb Reference Lamb2024b:372–73, emphasis in original). The interdependence of meaning-making and transformation between humans and other-than-humans is further illustrated by Máiréad Moriarty (Reference Moriarty2025), whose ‘seascape’ study reveals oceans and humans as mutually constituted, and by Bal Sharma (Reference Sharma2025), who highlights how multispecies landscapes are entangled with commodity relations.

These theoretical advances suggest a new perspective for semiotic landscape scholarship: that all space, including supposedly ‘natural’ landscapes, may be a focus for semiotic analysis. The absence of birds at the Grand Canyon of Arabia provides a case for testing this claim. Nominally, birds or their absence is not a sign, but a non-human feature in a ‘natural’ landscape—a concern for local residents or biologists rather than for sociolinguists or semioticians, whose focus is relegated to meaning-making resources produced by humans. The absence of birds, however, is human-made. Ibrahim and his father both told me separately that they cannot say for sure what happened to the birds, as did a British ornithologist who has lived in Oman for five years working in environmental consultancy. Such a large-scale drop in the avian population, the ornithologist explained, is difficult to pinpoint given the context; while habitat loss, hunting, overgrazing, and climate change are all impacting the region (Ibn-az-Zubair, Mershen, & Al Saqri Reference Ibn-az-Zubair, Mershen and Saqri2019), many species of birds in the Arabian Peninsula are migratory, so a regional population can be decimated by events taking place thousands of kilometers away. While the disappearance of birds from Jebel Shams is likely some combination of many such factors, the agency of humans is unmistakable, and is merely another instance of a process being witnessed around the world (BirdLife International 2022).

The argument can nonetheless be made that biodiversity decline is not a ‘deliberate’ way of making meaning in the landscape (cf. Jaworski & Thurlow Reference Jaworski and Thurlow2010:2). Yet this argument echoes a position taken by fossil fuel corporations, who claim that by having historically proceeded in ignorance of industry impacts they are not culpable in seeking redress for climate change—even as ample evidence has now accrued that, as far back as the 1980s, scientists working for Exxon and Shell had alerted industry leaders that burning carbon was heating the atmosphere (Franta Reference Franta2018). What can be seen instead is that fossil fuel corporations have engineered ignorance, deploying it as a resource in the agnotological production of acquiescence to their operations (cf. Proctor Reference Proctor, Robert and Schiebinger2008); we may wonder, similarly, whose interests are served in maintaining focus only on those landscapes which are deemed to be ‘deliberately’ constructed.

In any case, it is not always clear what actions will produce meaningful inscriptions in the landscape. One has only to look to David Karlander’s (Reference Karlander2019) study of the municipal erasure of graffiti, in which the lingering smears alluding to its former presence communicate not ‘clean’ upmarket spaces but a regime of control—hardly an intended outcome by city authorities, and another example of silence speaking magnitudes (see Jaworski Reference Jaworski1992). For students of environmentalism, the ‘silence’ produced by an absence of birds at the Grand Canyon of Arabia likely sounds familiar: it is, after all, the same human-made sign identified by Rachel Carson in Silent Spring (Reference Carson1962), which linked pesticides to biodiversity decline and launched the modern environmental movement in North America. As Bernard Perley & Henrietta Black (Reference Perley, Black, Kosatica and Sean2025) go on to show, this ‘silence’ is emblematic not just of chemical-driven avian death, but of the centuries of settler colonialism that silenced Indigenous languages and lifeways. Planetary crisis, in other words, is deeply rooted in coloniality (cf. Quijano Reference Quijano2007).

It is this critical understanding of what many call the Anthropocene that ultimately disenfranchises the argument that sociolinguistics and semiotic landscape studies can only evaluate the human: there is, in effect, no space without human imprint. As Farhana Sultana (Reference Sultana2022) describes in her formulation of ‘climate coloniality’, the catastrophic floods, heatwaves, and fires that are mushrooming amidst rising global temperatures are signifiers of extractive capitalism. That the planet is itself a meaning-making actor comes into view through its responses to human activity, as the systems regulating climate entangle with burning fossil fuels. What Dipesh Chakrabarty (Reference Chakrabarty2021:67) calls ‘the planetary, a perspective to which humans are incidental’ underscores that all landscapes are semiotic, and humans and even ostensibly non-living things are agents of semiosis. Yet as the conversation with Ibrahim at the beginning of this article discloses, these ubiquitous signs of planetary crisis are often unmarked. The next section considers why.

A sociolinguistics of attention: Space, semiotic ideology, and attunement

Signs in space are interpreted through an interaction of ideology and power. As Doreen Massey (Reference Massey2005) observes, space is a sphere of possibility as multiple ‘trajectories’ coexist with others, yet globalized capitalism narrates a single and unified trajectory that excludes multiplicity. Power also circumscribes the emplacement of signs, further impacting how space is experienced. As Jackie Lou (Reference Lou2016) shows, the linguistic landscape comprises a fundamental dimension to the materiality of space, and it intersects with how space is ‘conceived’; it is this nexus of materiality and conception that produces the social space of interaction and experience (Lefebvre Reference Lefebvre1991). In the trajectory of modernity, ‘Nature’ in discursively conceived space is separated from human society, a condition further produced by ‘uneven development’: capitalism’s inherent logic in which capital is differentially invested and continually relocated in the pursuit of accumulating exchangeable goods. While the absence of capital ostensibly signifies ‘Nature’, ‘[h]uman beings have produced whatever nature became accessible to them’ (N. Smith Reference Smith2010:81).

Even as capitalism’s production of nature undercuts Nature/society dualism, it is through capitalism that this discourse persists, and that so many signs of the Anthropocene go unmarked. Signs not only represent something, but ‘can and must be interpreted’ (Eco Reference Eco1986:46). As the case of ‘Nature’ indicates, axes of interpretation hinge on hegemonic ideologies. The interpretation of a sign can be understood as a function of ‘semiotic ideology’: a collection of shared assumptions about ‘what signs are’, and what they are doing in a landscape (Keane Reference Keane2018:69). A semiotic ideology appoints ‘sign vehicles’, or an identified author or mobilizer of a given sign. Semiotic ideologies come into existence through representational economies, in which interrelated facets of a context—ranging from technology, to media, to practice—collaboratively produce a rationale for the why and how of signs in a landscape. The circulation of discourse through mediatory practices and technologies produces a semiotic ideology, even as discourse produces the landscape which this ideology interprets.

Yet discourse shapes the way entire landscapes are interpreted. While different semiotic ideologies foster shifts in how landscapes are perceived as ‘semiotic aggregates’ (Scollon & Wong Scollon Reference Scollon2003), a perceiver of a landscape also does not identify and interpret every sign possible to be sensed. What signs draw human attention is also a function of ideology. As Sara Ahmed’s work on phenomenology illustrates, signs are marked through ‘orientations’, which shape how individuals ‘inhabit’ and understand the space around them. Building on her thesis that emotions are ‘directed’ at objects in space (Ahmed Reference Ahmed2014), she argues that directional ‘lines’ of orientation bring some objects closer to one’s body while others remain obscured or marginal. Individuals ‘line up’ according to sedimented ‘lines of social reproduction’, as orientations ‘around’ hegemonic ideologies gather force and enlist others to join the same directional line in space (Ahmed Reference Ahmed2006:141). Resultant schemas of attention emerge out of more fundamental orientations in sociocultural and political life, such that ‘what appears depends on one’s point of view’ (Ahmed Reference Ahmed2006:12).

Attention is a key staging ground in the interpretation of landscapes, guiding an interaction with space that is informed by discourse. As attention orients which signs are identified in space, one landscape out of multiple possible interpretations comes into focus. Recent sociolinguistic studies of landscape have also marked the importance of attention for understanding space, and especially spaces of crisis. In her examination of contested Crimean landscapes, Natalia Volvach (Reference Volvach2024) shows that the sensitivity toward space—that is, the ability to pay attention—delivers essential insights into what is present only as barely discernible traces. Following Rodrigo Borba and colleagues (Reference Borba, Fabrício and Lima2022:799), grasping longer and often repressed histories demands ‘attending both to…semiotic materiality and to the immaterial dimensions’ of potential meanings in a landscape. As the unmarked absence of birds likewise indicates, the study of planetary crisis demands a sociolinguistic theory of attention.

Such a theory might draw insights from Anna Tsing’s (Reference Tsing2015:128) call to develop ‘arts of noticing’, which in multispecies studies alludes to paying attention to non-charismatic forms of life and other lively elements in a landscape against which modernity conditions ignorance (Kirksey & Chao Reference Kirksey, Chao, Chao, Bolender and Kirksey2022). Developing new attentional repertoires can unveil an entirely different landscape, as assemblages of formerly unnoticed and unseen life draw into focus (Du Plessis Reference Du Plessis2022). Leonie Cornips, Ana Deumert, & Alistair Pennycook’s (Reference Pennycook2024) proposition of a sociolinguistics of ‘attunement’, in which human interrelations with more-than-human agencies and temporalities are brought to attention (also see Brigstocke & Noorani Reference Brigstocke and Noorani2016), may thus offer a way forward for semiotic landscapes in planetary crisis. As the following analysis shows, attunement to signs of the Anthropocene undercuts ‘Nature’ discourse and suggests new relationalities that are not oriented around extractive capitalism.

Methodology

This article emerges from an ethnographic and discourse-analytic study empirically grounded in eighteen weeks of fieldwork in Oman.Footnote 2 Between March 2022 and March 2024, I engaged in participant observation at numerous tourism sites and recorded forty-three interviews in English and Arabic with citizens, residents, and tourists. Many more conversations were not recorded but rather written up in field notes, as many of the people who helped in this research preferred to not be formally interviewed. Also, during this two-year period, I maintained an active digital presence within local networked communities on Instagram, interacting with users, collecting screenshots, and making my own posts. This ‘hybrid’ ethnographic material (see Przybylski Reference Przybylski2020) was systematically coded and analyzed in a recursive process, developing a grounded approach to yield insights that are not anticipated by the researcher (LeCompte & Schensul Reference LeCompte and Schensul2013). The material presented here represents only one focus in this project, the development of the Jebel Shams Balcony Walk as a tourism destination.

The Balcony Walk is likely the most famous hike in Oman, first gaining popularity as a destination around the year 2000 among migrant workers (locally termed ‘expats’) and then becoming increasingly prominent as international tourism began to grow in the 2010s. Today, the Balcony Walk is part of ‘the standard tourist route’ in Oman, as a Quebecois tourist described it to me in February 2024. The hike begins from Al Khataym (الخطيم), a small village about 1000m up Jebel Shams (جبل شمس ‘Sun Mountain’) at the edge of the Grand Canyon of Arabia, with the trail proceeding more or less horizontally for 6km along the edge of the canyon until the abandoned village of Saab Bani Khamis (ساب بني خميس) is reached. As suggested by the Arabic name ‘Saab’, colloquially meaning steep slopes on high mountains, the village is nestled beneath concave walls of rock at the edge of a cliff which plunges to the bottom of the canyon, called Wadi Ghul (وادي غول). I first visited the Balcony Walk in March 2022, and have returned during each of my five visits to Oman, sleeping at a homestay in Al Khataym or camping above the canyon rim, hiking the trail six times, conducting recorded interviews with tourists, and holding many more off-record conversations with both tourists and area residents. Discussions were always foregrounded by my explaining that I am a university researcher studying and writing about tourism development. In a setting where most residents do not speak English, many conversations were enabled by my conversational level of spoken Arabic.

In order to collect a broader sample of tourist perspectives than interviews alone would allow, I have further drawn upon public digital data in another ‘hybrid’ ethnographic strategy. On 18 March 2024, I collected 482 Google reviews from the ‘W6 – Balcony Walk Hike’ listing on Google Maps, which has an overall rating of 4.8 out of 5. Of the 482 reviews posted between 13 October 2017 and 3 March 2024, 308 contained text written in one of fourteen languages, the most common of which being Arabic, English, French, German, and Polish. I used Google Translate to create an English text of all non-English reviews, and then manually coded all 308 reviews using a combination of open and selective coding based upon the questions, ‘How is the Balcony Walk dominantly perceived by reviewers?’ and ‘How is “nature” brought into relation with the canyon?’. The themes that emerged from this process can be grouped under the keywords: view, landscape/geography, light, tourism, development, nature, abandoned village, waterfall/water, goats, and Grand Canyon. The term ‘Grand Canyon’ featured in fifteen reviews, while ‘the view’—or similar terms, such as ‘scenery’—was mentioned in ninety-five reviews. The following analysis is informed by these reviews and fieldwork data.

‘Nature’ and ‘the view’: An orientation at the Balcony Walk

Visitors come to the Balcony Walk from around Oman, the Gulf, and abroad as day-trippers and as international tourists. Ethnographic and digital data reveal a profound orientation around ‘Nature’ discourse among visitors, supporting a shared semiotic ideology that frames interpretation of the canyon and generates an attentional line in which signs that contradict ‘Nature’ are typically unmarked. This orientation around ‘Nature’ is grounded by a way of seeing (cf. Berger Reference Berger2008) that concretizes in a discourse of ‘the view’, in which facets of the landscape are ideologically linked to an enregistered value for the ‘pristine’ and ‘untouched’ (S. P. Smith Reference Smith2025a); in this discourse, sign vehicles are not human-authored but rather ‘natural’. Hiking the Balcony Walk, visitors collocate ‘the view’ with ‘Nature’, as one reviewer wrote in German: Einmalige Aussichten und tolle Natur ‘Unique views and great nature’.

Repetition of ‘the view’ and ‘nature’ suggest a fungibility in terms. One reviewer wrote in Dutch that is het een fantastische wandeling met waanzinnige uitzichten naast een imposante canyon ‘it is a fantastic walk with amazing views next to an impressive canyon’, while another, in English, reported:

The magnificence of nature humbles humans… We were mesmerized by the awesomeness of the canyon formation.

The emphasis on visual consumption of a landscape that is separate from human social life reprises the primary form of interaction with more-than-human environments that has characterized tourism since the nineteenth century (Urry Reference Urry1992). The separation of humans from the allegedly ‘natural’ landscape can also be seen in an Arabic-language review, which emphasizes ‘feeling’ yet highlights distinctly visual elements in the canyon. These impressive features are ascribed to the work of God, with attention to the pool of water indicative of a more localized interest in a region where water is scarce:

بحيرة ماء كبيرة جدا تكونت… التي تحتفظ بالماء طوال العام حتى في فترة انقطاع الأمطار. ويوجد ايضا كهف كبير بالقرب من البحيرة تتساقط منه المياه على شكل قطرات… ويشعر الزائر لمنطقة ساب وادي بني خميس بالرحة وبجمال المكان ومفردات الطبيعة التي ابدعها الخالق عزوجل

‘A very large water lake was formed… that retains water throughout the year, even during periods of interruption of rain. There is also a large cave near the lake from which water falls in drops… The visitor to the region of Sab Wadi Bani Khamis feels the comfort, the beauty of the place, and the vocabulary of nature created by the Almighty Creator’

Across cultural contexts, however, the Grand Canyon of Arabia is interdiscursively linked to an orientation around the Grand Canyon in the United States. The global circulation of Grand Canyon imagery supports the development of a hermeneutic circle, as tourists at the Balcony Walk seek an image of what has ‘already been seen’ (Urry & Larsen Reference Urry and Larsen2011:179). On one occasion, at a guesthouse in a town below Jebel Shams in February 2023, a Polish tourist described his Balcony Walk experience: ‘I don’t know the Grand Canyon…?’ he said, looking expectantly to me. He was disappointed when I told him I had not seen the famous site in Arizona: ‘Oh. Well, I think it is like that.’ So too did many Google reviewers, such as one writing in Czech:

Opravdu úžasný zážitek. Nemusíte na Grand Canyon, tady je druhý největší. Adrenalin a nádherné výhledy.

‘A truly amazing experience. You don’t have to go to the Grand Canyon, here is the second largest. Adrenaline and wonderful views.’

The Grand Canyon is repeatedly linked to the discourse represented across languages as the ‘view’. In September 2022, as I approached the Balcony Walk trailhead, a pair of French tourists stopped to tell me about ‘the view’ I was about to experience. ‘It’s like the Grand Canyon’, one said. As another Google reviewer wrote in English,

This is probably by far the most picturesque walk I’ve ever taken. I couldn’t help myself and had to make stops every few meters or so just to admire these monumental views. Truly grand canyon of the east, no doubt.

As a reviewer put it simply, in Spanish: El gran cañón de Arabia, merece la pena por las vistas ‘The grand canyon of Arabia, worth it for the views’. The ‘worth’ of this ‘view’ orients the interpretation of space through a shared semiotic ideology, in which the ‘canyon formation’ is the focus of attention as it indexes the broader discursive formation of ‘Nature’. Yet this interpretation is merely one among many possible framings of the canyon, as the history of the US’s Grand Canyon reveals.

The Grand Canyon: From ‘altogether valueless’ to an enregistered imaginary

The Grand Canyon is one of the largest geologic formations of its kind in the world, developing over two billion years into a vast canyon 1,857m deep. Today, it is the third-most popular National Park in the United States, with 4.9 million visitors in 2024 (National Park Service 2024). Yet its popularity is comparatively recent, even within the roughly 250-year tourist practice of consuming ‘natural’ landscapes. Prior to European conquest and settlement, the Grand Canyon region was home to numerous peoples including the Havasupai, the Hualapai, and the Southern Paiute, for whom the canyon and its surrounds was defined by interwoven relations between humans and more-than-human animals, plants, and geography (Stoffle, Halmo, & Austin Reference Stoffle, Halmo and Austin1997). In 1540, Spanish soldiers led by Indigenous Hopi guides were the first Europeans to see the canyon, and they possessed few frameworks for interpreting or ascribing value to the region as anything more than an obstacle to overland travel; as recently as 1858, the canyon was described as ‘altogether valueless’ by its first American visitor (Nye Reference Nye, Joan and James2020:75).

The identification of the Grand Canyon as a site of visual value began with the arrival of European and American artists and photographers in the latter half of the nineteenth century. Of these, Thomas Moran contributed most to recognition of the canyon as an extraordinary sight and marker of national pride (Stein Reference Stein2019). In Moran’s 1873–1874 painting, Chasm of the Colorado, the continuation of a Romantic legacy prefigured by JMW Turner is evident in the sheets of rain tumbling past the vertiginous clefts of the mesa’s escarpment, locating the canyon as a new site for encountering sublime nature (Figure 2). This most famous early depiction of the canyon seems to anticipate the site’s uptake as a discourse to which reality is secondary; the perspective Moran creates is a composite of views onto the canyon, enabling an upward-tilting gaze which no actual place could provide (Nye Reference Nye, Joan and James2020). The proliferation of ‘views’ like Moran’s was essential in cultivating a value for such rugged desert landscapes, which had formerly not fallen within the purview of the tourist gaze.

Figure 2. Chasm of the Colorado, Thomas Moran, 1873–1874, oil on canvas, US Department of the Interior Museum.

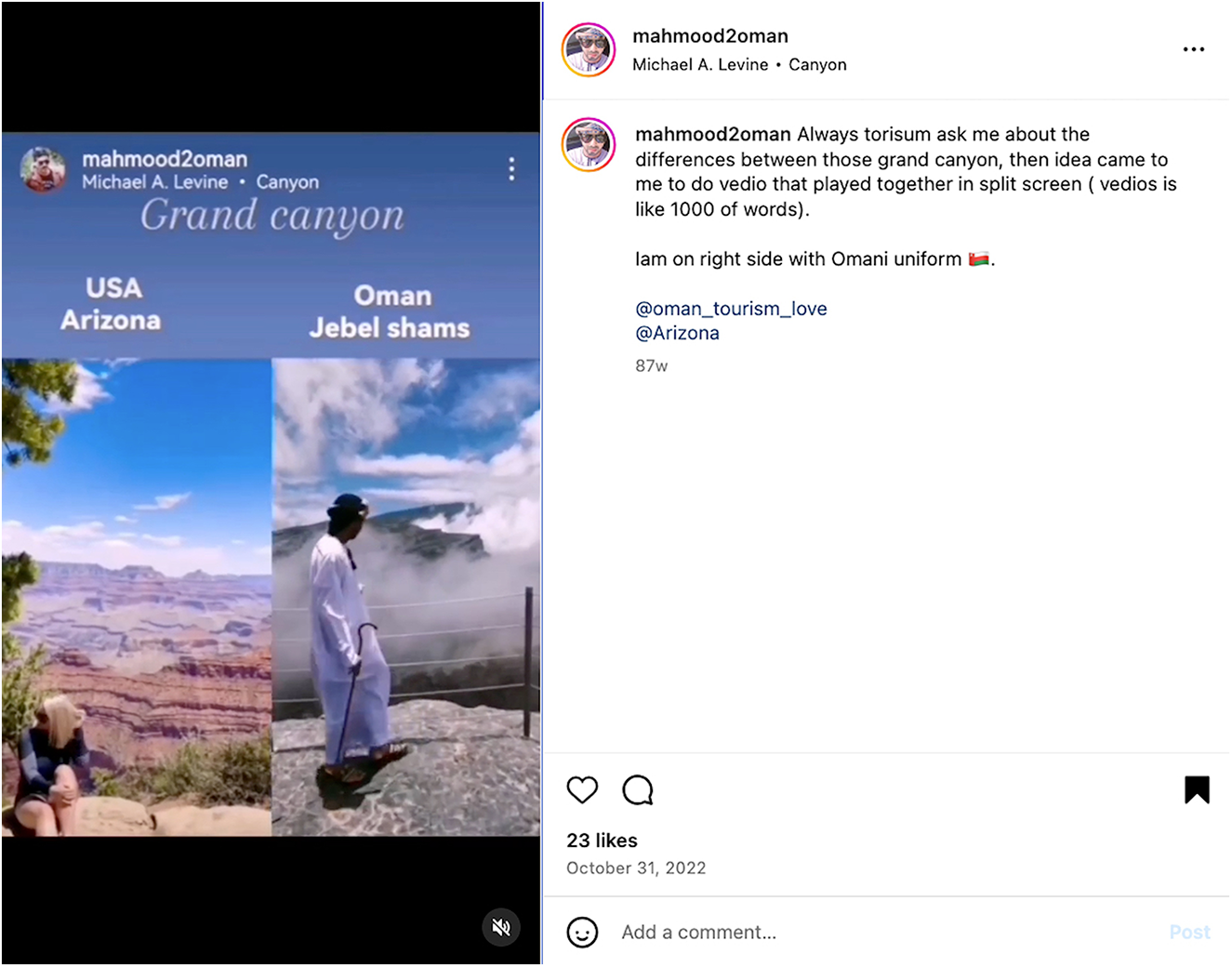

The inauguration of Grand Canyon National Park in 1919 represents the culmination of a process of enregisterment, as the canyon became the source of a visual and affective semiotic register that circulates through linked discourse events in a ‘semiotic chain’ (Agha Reference Agha2006:205). The discursively produced Grand Canyon US forms a globally circulating template for how both international tourists and residents encounter the ‘Grand Canyon of Arabia’, illustrated in a post by Mahmood, an Omani tour guide (Figure 3). With the juxtaposition of videos from Arizona and Oman, the two Grand Canyons are dialogically interlinked in both visual and—as Mahmood’s caption recounts of the questions tourists ask him—spoken discourse. As the next section describes, the enregisterment of the Grand Canyon as a source of value entrenches the orientation around ‘Nature’ and a shared semiotic ideology.

Figure 3. Instagram post by @mahmood2oman (reprinted with permission).

‘For the view’: How value produces ‘Nature’

As of my last visit to the Balcony Walk in February 2024, relatively few human-emplaced signs mark the landscape. At the parking area in the village of Al Khataym, a sign in Arabic and English demarcates the path as the W6 trail, marked in red on a relief map. Yet visitors must ask about the trailhead or simply wander, walking past a souvenir stall and a few newly built accommodations to find the red, white, and yellow flags painted on rocks that signpost trails in Oman. Aside from two cafes serving coffee, created in the 2022–2023 season, there is no other signage until one has passed most of the ruins of the abandoned village, where Saab Bani Khamis is spray-painted in Arabic and English on a rock next to the mosque (Figure 4). Most of these markers were not present when I first visited the Balcony Walk in March 2022, so the emplacement of further signage is likely—but, to date, most visitors instead navigate the trail through digital inscriptions.

Figure 4. ‘Saab Bani Khamis’ spray-painted in Arabic alongside ruins of the now-abandoned village (author’s photo, September 2022).

In Oman, the most important platforms through which both locals and tourists acquire information are Instagram and Google Maps, with one respectively providing inspiration and the second logistics. As one Omani tour guide who has visited the Balcony Walk many times explained to me, ‘Most people see pictures, then they go to Google Maps then go’. A tourist from India who lives in Dubai followed a similar route to arrive at the trail:

[My friend] was visiting Oman and I saw Balcony Walk on her Instagram Story, and it looked quite cool… Balcony Walk was just one of those random things I Googled, the pictures looked good…

The link between a visual pretour narrative, Google Maps, and arriving at the Balcony Walk trailhead suggests a mediatized online/offline nexus (cf. Androutsopoulos Reference Androutsopoulos, Blackwood, Tufi and Amos2024), supporting a continuous landscape informing practice as tourists are not just motivated to visit the Balcony Walk but are instructed in how to take their own photos when they arrive. As one Google Reviewer writes,

Gorgeous hike! Easy park at the start and Google maps is accurate. The hike can be done in a few hours, but leave extra time for a serious amount of photos.

Similar to the interaction with tourism sites around the world, the encounter with ‘mediatized representations’ of the Balcony Walk subsequently orient the ‘mediated actions’ of visitors as they navigate the space—actions which are subsequently digitally remediated (Thurlow & Jaworski Reference Thurlow and Jaworski2014). What Lamb (Reference Lamb2024a) calls ‘circuits of representation’ disseminate semiotic ideologies and enlist shared orientations to space, not least due to the marketized worth of high-value ‘views’ such as Grand Canyons afford. Sociolinguistic studies of tourism document the value of ‘symbolic’ goods such as photographs and the narration of experience (Thurlow & Jaworski Reference Thurlow and Jaworski2010; Heller, Jaworski, & Thurlow Reference Heller, Jaworski and Thurlow2014), which support the commodification of places, identities, and visual perspectives (Sharma Reference Sharma2018; Gonçalves Reference Gonçalves2020; S. P. Smith Reference Smith2021). Recent studies illustrate how ‘Nature’ itself has become not only an object of symbolic value but a semiotic register for branding destinations and the self (Wilson Reference Wilson2022; Nilsson Reference Nilsson2024), consonant with an increasing interest in nature tourism witnessed around the world (S. P. Smith Reference Smith2025b). The exchange value of nature images, so easily created at the Grand Canyon of Arabia, focuses attention to the signs of ‘Nature’.

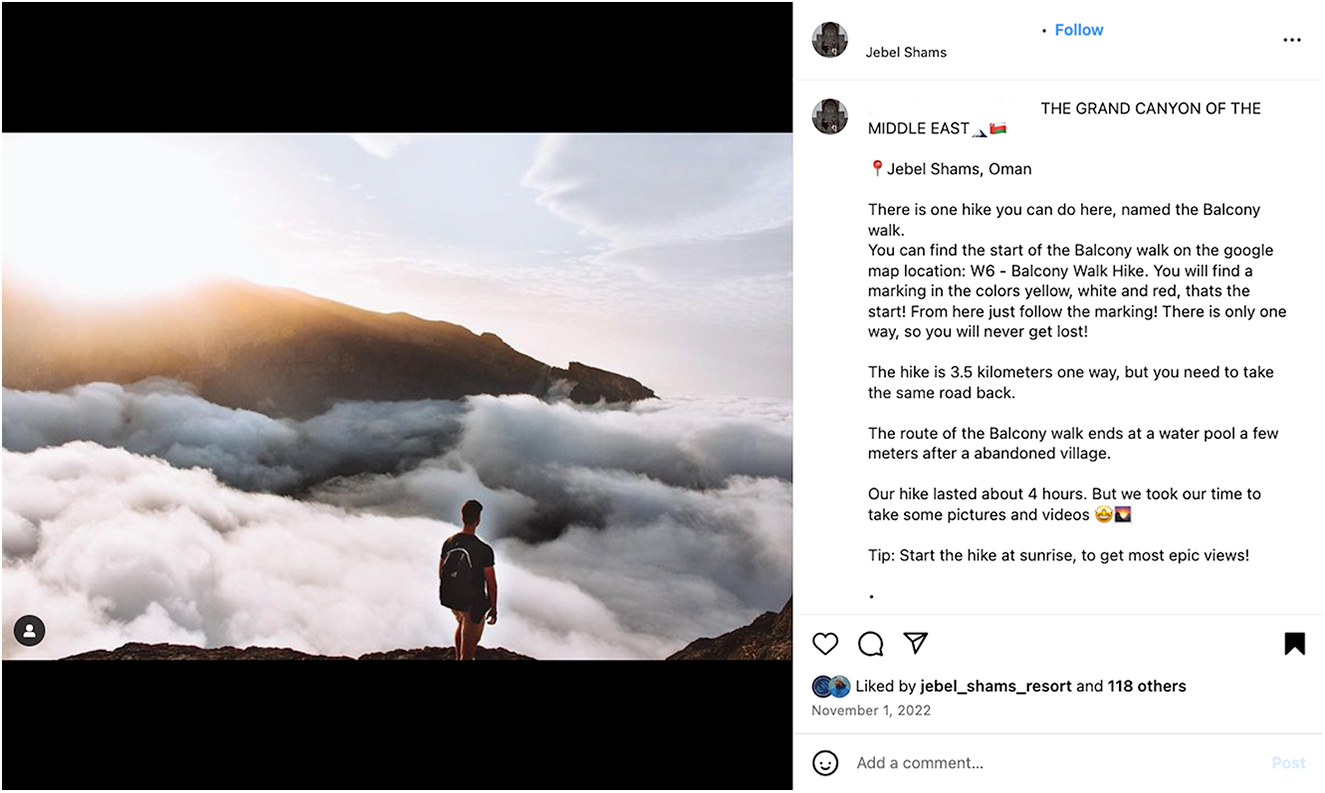

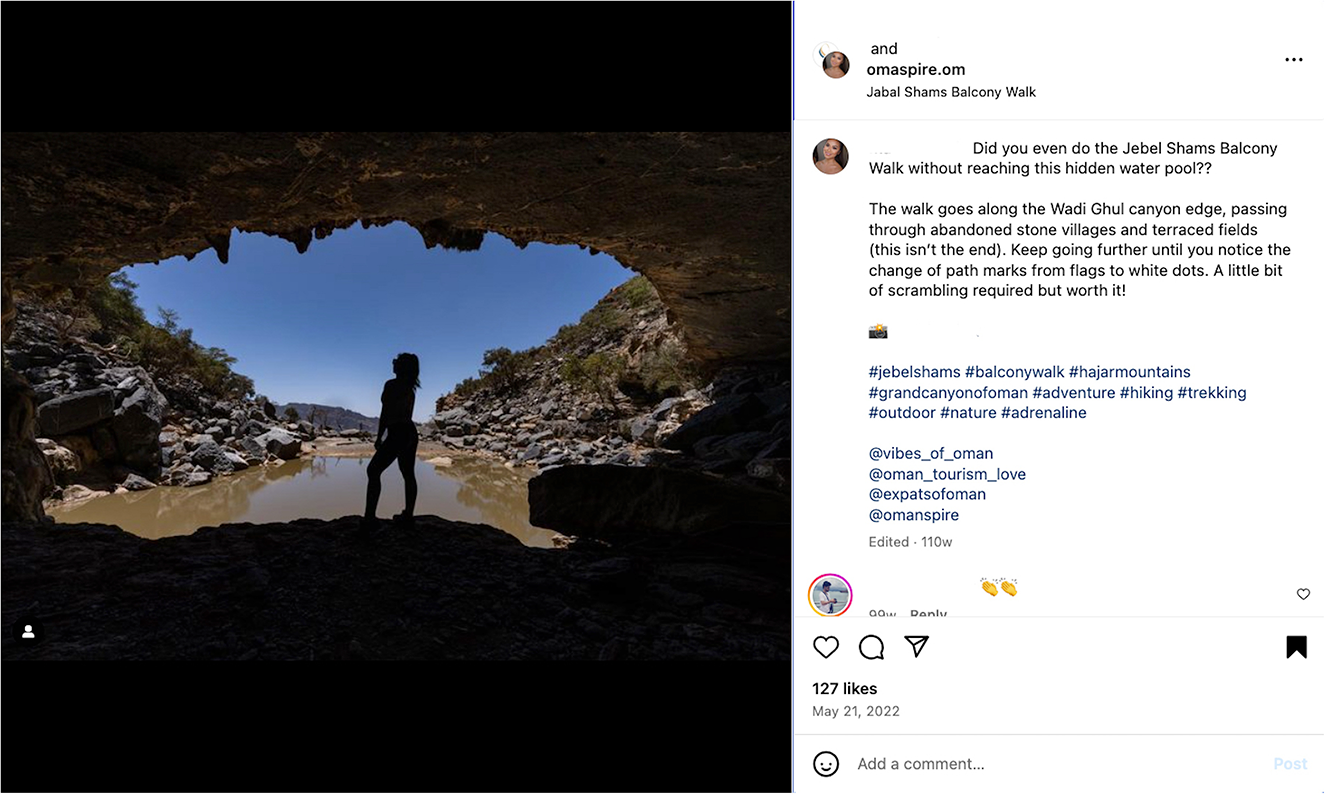

In one Instagram post, entitled ‘THE GRAND CANYON OF THE MIDDLE EAST’, the caption provides instructions for how an online audience can arrive at the canyon themselves: ‘You can find the start of the Balcony walk on google map location: W6 – Balcony Walk Hike’. One of the ‘pictures and videos’ the user took features a lone hiker standing silhouetted by clouds over the canyon at dawn (Figure 5), the promontory witness composition citing a mediatized visualization of human interaction with landscape that is generative of (symbolic) capital. Such a distinction-making move aligns the canyon with global economies of value in which landscapes are accumulated as a symbolic good, as experiencing the canyon according to hegemonic ways of seeing promises social return (S. P. Smith Reference Smith2021). A similar post featuring a lone hiker silhouetted by the ‘hidden water pool’ offers instructions for following the obscure path, which, despite the challenge, is ‘worth it’ (Figure 6).

Figure 5. An anonymized tourist’s Instagram post at ‘THE GRAND CANYON OF THE MIDDLE EAST’ (reprinted under fair use).

Figure 6. An anonymized tourist’s Instagram post at the ‘hidden water pool’ (reprinted under fair use).

The circulation of images representing ways of seeing landscapes as a source of value, as well as the invocation of language ‘shaped by the market’ (Graeber Reference Graeber2011:18), entrenches semiotic ideologies of ‘Nature’ and also produces economic geographies. Over the two years I visited the canyon, development could be seen in the construction of cafes on the rim overlooking the Balcony Walk trail and in the rapid expansion of tourist accommodation in the village of Al Khataym, where landowners are building rooms themselves and also leasing to a national resort chain. This accommodation is expensive, averaging around 50 OMR (€125) a night. ‘Why is it so expensive?’ Ibrahim posed to me, rhetorically, that day we stood chatting by the trail. He pointed to the canyon’s rim: ‘للمنظر’ ‘For the view’, he said simply. Yet as the next section indicates, despite this emphasis on the view—or rather, because of it—there is much that goes unseen by visitors to the canyon.

Disorientation in planetary crisis

Before Saab Bani Khamis was abandoned, during the warm months around twenty people lived in the village, tending goats and farming crops including apricot, figs, olives, and garlic on terraces carved out from the plunging slopes, while in winter they descended a vertiginous trail to Ghul village in the canyon below. Villagers traded these crops at markets in nearby towns, making the three-day journey by donkey to obtain goods which they could not produce for themselves. Life on the mountain was abundant; not only birds, but animals such as the endangered Arabian tahr and the now regionally extinct Arabian wolf were common. This began to change when oil was discovered in Oman in 1962. After Sultan Qaboos took the throne in 1970, the country entered a period of development in which the predominantly rural and agrarian population became urbanized. Residents of remote villages began to migrate to urban centers connected to infrastructure in order to access healthcare and education, moving into houses given to them by the state using newfound oil wealth. The last residents of Saab Bani Khamis left around the year 2000, when a dam was constructed above the canyon and the water upon which the village depended was substantially reduced. Abu Ibrahim, now nearly ninety years old and the father of the man I spoke with in the introductory vignette, was the last resident of Saab Bani Khamis. As he told me, ‘Everyone has gone down, to [the town of] Al Hamra, other places. What do I want with the farm?’.

This history enables a very different understanding of the canyon. Rather than an object of picturesque fascination, the abandonment of the Saab Bani Khamis is closely entwined—as theories of assemblage would confirm—with the discovery of oil in Oman and with the heating of the planet. The canyon’s ‘Nature’ is shown to have been drastically changed over the ensuing decades, as the burning of fossil fuels and entrenchment of modernity not only vanquished many of the birds but also other fauna and flora, as well as human lifeways centuries if not millennia old. The pool of water, widely noted by tourists, is but a remnant of the waterfall that used to stream down from the canyon rim even without great rains—and yet not a single tourist, online or who I met in person, mentioned or seemed to know of the dam (Figure 7). While this deeper history is largely unseen, its signs are nonetheless evident—if only one knows how to interpret them.

Figure 7. The dam (upper circle) above the water pool (lower circle). Google Earth, screenshot March 2024 (reprinted under fair use).

What prevents these interpretations is the dominance of a semiotic ideology in which signs are not indexically linked to non-‘natural’ sign vehicles. An orientation around the discursive formation of ‘Nature’, in other words, ideologically uncouples anthropogenic signs in a landscape from their signified. As during my conversation with Ibrahim, however, the revelation of a sign vehicle—in this case, that the absence of birds was not ‘Nature’ but anthropogenic change—can destabilize an ideological formation. This interpolation exemplifies what Ahmed (Reference Ahmed2006:158) terms ‘disorientation’, when one’s extension into space fails. When the space one inhabits no longer fits one’s body or one’s expectations, a ‘perspective’ is lost; as she puts it, ‘disorientation shatters our involvement in a world’ (Reference Ahmed2006:177). The absence of birds is but one example of how disorientation from ‘Nature’ reveals signs indexing the Anthropocene, disrupting anthropocentrism and spurring understandings that humans are ‘in the same position as any other creature’ in a long and turbulent earthly history spanning four billion years (Chakrabarty Reference Chakrabarty2021:90). The realization of the ‘planetary’ may be a given for most other-than-modern ways of perceiving the world, but for colonial modernity it is shattering.

Rather than resisting such destabilization, however, disorientation offers a way forward into planetary crisis:

Moments of disorientation are vital. The point is what we do with such moments of disorientation, as well as what such moments can do—whether they can offer us the hope of new directions, and whether new directions are reason enough for hope. (Ahmed Reference Ahmed2006:157)

Amidst the gloom of climate prognoses, Anthropocenic disorientation holds a potential for disrupting the ideological frameworks that have caused the climate crisis. Writing in a different yet seemingly prescient context, Massey (Reference Massey, Christophers, Lave, Peck and Werner2018:171) describes disorientation as a kind of vertigo, ‘when the geography of social relations forces us to recognize our interconnectedness’. Nature, conceived in modernity as separate from humans, can no longer be imagined as anything but fundamentally shaped by and shaping of humans. The shocks this entails can give birth to new alignments, new ‘lines’ into the restive future which are not oriented through human-centered extraction. This is not a liberal ‘hope’ that the threats we face in the era of planetary crisis will be mitigated using established methods; rather, this is a hope which can mobilize new frameworks (cf. Perley Reference Perley2021; Silva & Borba Reference Silva and Borba2024).

Attunement suggests one such new framework, in which attention is turned to the relational interconnection of humans and other forms of life and matter. This may first entail an understanding of the landscape as fundamentally semiotic, produced by the sign-based interventions of humans, other-than-human life, and other-than-living processes. Orientating around relationality and entanglement rather than ‘Nature’ presents sociolinguistic problems that have been identified in other recent studies which may be broadly termed ‘posthuman’. Attunement challenges the linearity of modern space-time (Borba, Fabrício, & Lima et al. Reference Borba, Fabrício and Lima2022; Deumert Reference Deumert2022), as apprehending an entangled sign-vehicle often demands a view towards histories that are not immediately legible or are even excised from the landscape. As an individual interacting with a landscape, the researcher’s subjectivity and sensitivity to space—that is, their ability to pay attention—delivers insights into what is absent, or what is present only as barely discernible traces (Volvach Reference Volvach2024). While attention circulates in a political economy and for structural reasons is available to some more than others (Ahmed Reference Ahmed2006:32), a posthuman sociolinguistics of attention would not put the agency of attunement entirely within human hands. Whether it is through the absence of birds or a catastrophic weather event, the interventions in space of more-than-human life and the planet itself are making some signs impossible to miss.

Conclusion

How does one see the absence of birds? This article posits that such indexes of planetary crisis as declining biodiversity demand sociolinguistic study, consonant with recent perspectives on posthumanism. This is first advanced through a planetary perspective on semiotic landscapes, in which allegedly ‘natural’ landscapes are revealed to be produced through both human and more-than-human semiotic interventions. A second approach is developed through a sociolinguistic theory of attention, which reveals the interpretation of space to be formed through discourse and power. A planetary perspective and attention are examined through a case study of the Balcony Walk, a hiking trail and popular tourist site at the ‘Grand Canyon of Arabia’ in Oman. Drawing on ethnographic fieldwork as well as digital meaning-making on Google Maps and Instagram, I trace how an orientation around dualistic ‘Nature’ discourse shapes the semiotic ideologies through which visitors interpret the canyon. Yet following the conversation with Ibrahim recounted at the beginning of this article, the disruption of this ideological experience of space is described as disorientation, when planetary crisis ‘shatters’ the imagined separation of humanity from ‘Nature’ (cf. Ahmed Reference Ahmed2006).

Rather than resisting such destabilization, planetary crisis calls for embracing disorientation. This is achieved through attunement, or a sensitization to the more-than-human lifeways, histories, and processes that modern frameworks do not recognize as legible signs. Acknowledging that capitalist modernity and the spaces it has produced does not enclose all worlds calls into question for whom and to what end spaces are produced, and what human and more-than-human worlds are being stymied or violently erased. This recognition supports an awakening to how humans are but one form of life in a planetary history in which they are not centered (Chakrabarty Reference Chakrabarty2021), positioning sociolinguistics as a means of discerning an expanding semiotics of the Anthropocene.

Acknowledgments

My thanks go first to Ibrahim, Abu Ibrahim, and the many others in Al Khataym who generously shared their time with me and endured my many questions. I am also grateful to David Karlander, Kellie Gonçalves, and Gavin Lamb for helping me think through key elements of this article, and to everyone who attended its first incarnation at the 2023 Linguistic Landscape 14 Workshop in Madrid as part of the colloquium, ‘Anthropocenic landscapes: The semiotics of a dystopian future’. I am further indebted to Natalia Volvach and Caroline Kerfoot, who invited me to present a draft in their ‘Spectral landscapes’ panel at Sociolinguistics Symposium 25, and for their and other panelists’ constructive comments. Fieldwork for this project was supported by the Research Foundation—Flanders (FWO) and the Tilburg School of Humanities and Digital Sciences.