An unhealthy diet is estimated to be the second highest behavioural risk factor contributing to disability-adjusted life years lost worldwide and the highest risk factor for mortality in 2017(1). Unhealthy diets include those high in salt and sugar-sweetened beverages, and low in whole grains and fruits and vegetables(1). Contributing to these unhealthy diets is the food environments in which people live, work, play and learn(Reference Swinburn, Sacks and Hall2). Of particular concern is the increase in the consumption of foods from food service outlets (e.g. restaurants, cafes, fast-food chains and independent takeaways)(Reference Jones, Bentham and Foster3), which is associated with a greater total energy and fat intake(Reference Lachat, Nago and Verstraeten4), and higher body weight(Reference Bezerra, Curioni and Sichieri5).

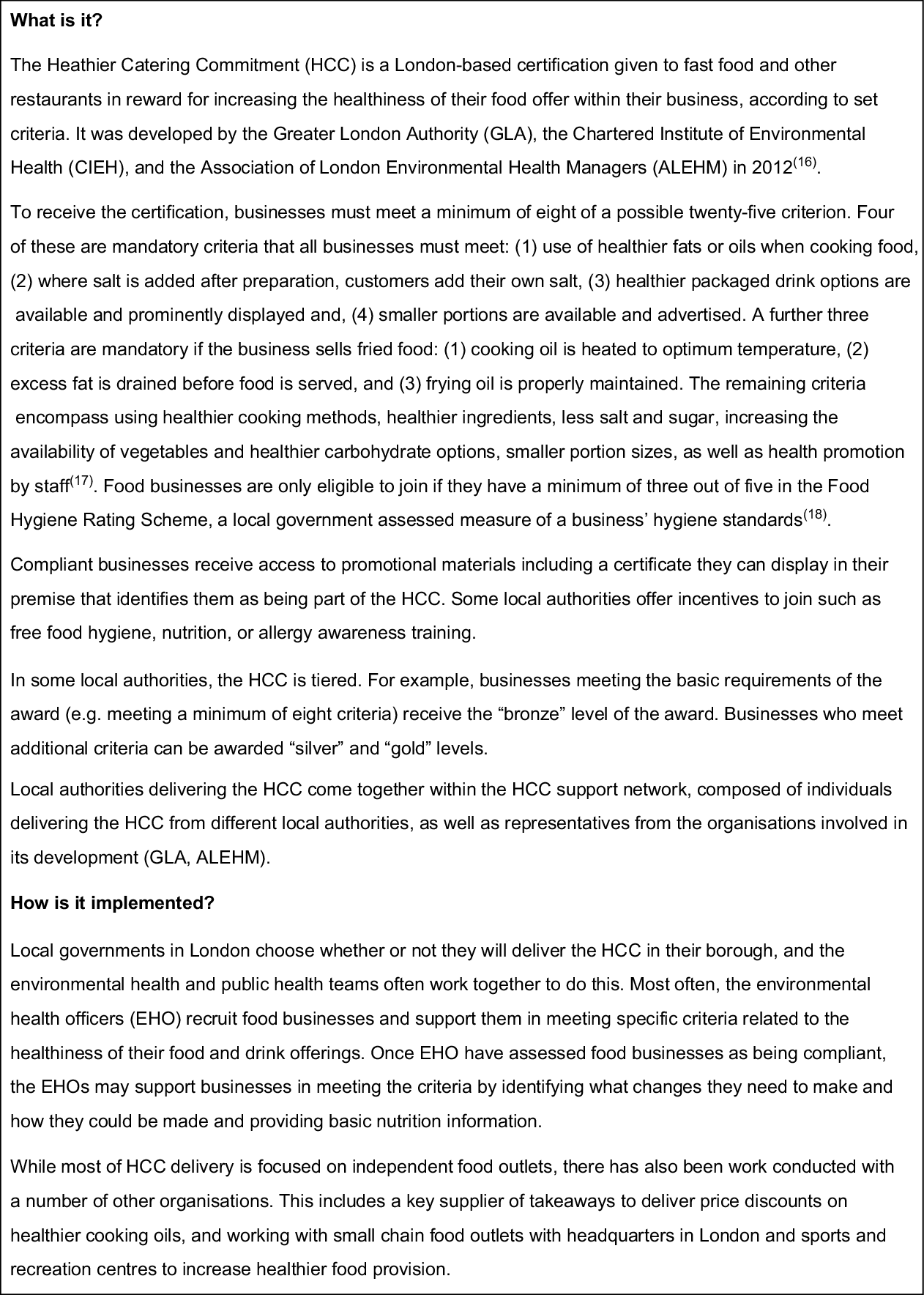

While comprehensive actions across sectors are required to address unhealthy diets(Reference Sacks, Swinburn and Lawrence6), local governments internationally have the potential to engage in innovative and impactful strategies aimed at improving food environments within their communities. Local governments have a historic role in promoting public health(Reference Dollery, Wallis and Allan7), have existing influence and relationships with food service outlets through the enforcement of food safety regulations(8–11) and have been identified as key settings in which to test innovative and progressive policies aimed at addressing obesity at a community level(Reference Reeve, Ashe and Farias12). Local governments are thus uniquely placed to impact local food environments, with previous examples of policy action including mandatory menu labelling(Reference Bleich and Rutkow13), limiting the development of new takeaway outlets through planning regulations(Reference Mitchell, Cowburn and Foster14) and giving tax credits to grocery stores that stock fruit and vegetables in low-income underserviced communities(15). The Healthier Catering Commitment (HCC) is an example of a voluntary London, UK initiative where local governments support food service outlets to create healthier food offerings. Local governments award food outlets a HCC certification once their food and beverage offerings have been assessed to meet specific, centrally defined nutrition criteria. HCC certification (a certificate and promotional materials) communicates to customers that the food outlet is providing healthier options. Figure 1 provides an in-depth description of the HCC criteria, and how it is implemented.

Fig. 1 Description of the Healthier Catering Commitment

While there are a plethora of policies and recommendations on how local governments can tackle obesity and unhealthy food environments(Reference Bleich and Rutkow13,Reference Mitchell, Cowburn and Foster14,Reference Freudenberg, Libman and O’Keefe19–24) , there is less evidence on the barriers and facilitators to doing so, and how these policies could be strengthened. One study examining local government-delivered initiatives aimed at creating healthier takeaways found that retailer engagement was a key challenge to policy uptake(Reference Goffe, Penn and Adams25). A further study examined the effects of a programme to incentivise grocery stores to stock healthier options in San Francisco – interviews with non-participating store owners revealed that some were unable to meet the eligibility requirements due to practical considerations such as space and fear of loss of profits(Reference McDaniel, Minkler and Juachon26). Yet, there is growing interest in initiatives aiming to improve the healthiness of food options in existing retail outlets. For example, the Healthier Oils Program in NSW, Australia, offers advice to food service retailers on how to switch to healthier cooking oils in order to reduce saturated fat in the food supply(27). In Singapore, food service operators that make healthy changes to their menus are eligible to apply for a grant that can be used to promote their healthier options, under the Healthier Dining Programme(28). If these types of healthy food service initiatives are to grow, more needs to be known about how local governments can facilitate their implementation and overcome barriers.

The current study aims to identify how local governments can facilitate implementation and overcome barriers to healthy food service initiatives, using the case study of the Healthier Catering Commitment, a voluntary initiative implemented in London (Fig. 1).

Methods

Overall method and theory

HCC was chosen to study through a document review of all accessible London local authority Local Plans, relevant Supplementary Documents and Health and Wellbeing documents, where it emerged as the most frequently mentioned initiative targeting the healthiness of options in food service outlets.

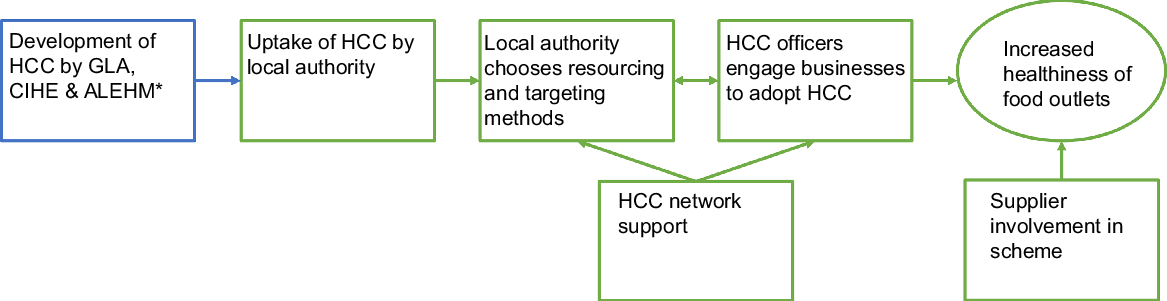

A qualitative descriptive method of enquiry was employed. The design of the study was based on a collective case study approach, in order to gain a broad understanding of the central phenomenon under study(Reference Crowe, Cresswell and Robertson29). A logic pathway of ideal implementation was used to guide interviews, analysis and presentation of results (Fig. 2). Logic pathways demonstrate the sequence of activities involved in a policy or programme and hypothesise the outcomes they are intended to achieve(Reference Pinnock, Barwick and Carpenter30). This allowed us to identify potential elements to strengthen the implementation of healthy food service initiatives delivered at a local authority level and to understand how elements may be adapted to other social systems. The terms ‘implementation’ and ‘delivery’ are both used within this study to describe the actions taken by local government staff towards the outcome of food service outlets obtaining HCC certification, including engagement of businesses, internal resourcing etc. The term ‘implementation’ is used in the context of policy theory(Reference Cairney31) and is therefore used when discussing theoretical implementation. ‘Delivery’ is the term favoured by the local authorities interviewed for this study and is therefore used in examination of the results.

Fig. 2 Logic pathway of ideal implementation of Healthier Catering Commitment (HCC). ![]() , Stages of HCC implementation;

, Stages of HCC implementation; ![]() , ideal outcome of implementation;

, ideal outcome of implementation; ![]() , factors explored in this study;

, factors explored in this study; ![]() , factors not explored in this study

, factors not explored in this study

Data collection

The lead author conducted key informant interviews using a semi-structured interview schedule. Participants were (1) those delivering or overseeing delivery of the HCC within local government or supporting organisations (e.g. that provide funding or technical expertise for HCC delivery) and were identified using a purposive sampling approach and (2) individuals who could give context to the HCC, for example, a supplier involved in the HCC, others involved in healthy food service initiatives, and were identified through snowball sampling and were invited to participate via email. Purposive sampling was employed in order to collect the perspectives of individuals with the most proximate knowledge of delivering HCC to businesses. Data triangulation was pursued through the inclusion of individuals at different levels of seniority and involvement (e.g. Environmental Health Officers delivering HCC and Public Health Leads overseeing delivery), from different departments (Environmental Health, Public Health), from different local authorities and the inclusion of individuals from supporting organisations. Local authorities were identified as participating in the HCC through the 2016 Good Food for London guide(32) and communication with the HCC network, a collection of individuals from local authorities who delivered the initiative. HCC coordinators were asked to participate by an email sent out by the HCC network coordinator and were reminded at an HCC network meeting. At the time of this study, there were twenty-four local authorities delivering the HCC(33), all of whom had a representative in the HCC network. Participant recruitment was conducted until data saturation was reached where no new themes emerged from the interviews, and the research questions had been sufficiently addressed.

An interview guide containing open-ended questions was developed prior to the interviews, developed based on existing experience with food policy implementation research by several authors. An interview guide was developed for each type of participant (e.g. local authority HCC coordinator, HCC-supporting organisation, supplier engaged in HCC etc.). See Appendix I for interview running sheets. Questions examined the participants’ role in delivering the HCC, challenges in engaging food businesses in the initiative and strategies for overcoming them, existing tools and resources used to deliver the HCC, and how the HCC could be improved.

Semi-structured interviews were conducted by the lead author either in person at a location and time convenient to participants (at their place of work, excepting one participant who attended the University of the lead author), or over the phone if no convenient time could be determined between the interviewer and interviewee to meet in person. Interviews lasted from 25 to 70 min. Interviews were audio-recorded and then transcribed by a professional transcription company. Participants were given the opportunity to review their transcripts over email, with two interviewees adding further details to their statements. The remainder of participants agreed with their transcripts in their entirety or did not respond to the communication.

Analysis

Thematic coding and organisation of themes arising from all interviews were conducted by the lead author using QSR NVivo version 11(34). An open coding approach was employed, with descriptive codes applied to blocks of text(Reference Liamputtong35). Deductive and inductive coding approaches were applied. Descriptive codes were organised into overarching deductive themes related to implementation stage (see Fig. 2; i.e. uptake of HCC by local authority, business engagement method, adoption by food business and effectiveness of changing food offer). If descriptive codes did not map onto any implementation stage, they were organised under emergent themes as arising from the text. Themes and sub-themes were identified by the consistent contribution of ideas across participants. Another researcher conducted thematic analysis of three of the interviews with HCC coordinators, with discrepancies resolved and final key themes consolidated through discussion with the lead author.

This study was conducted according to guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki(36), and all procedures involving study participants were approved by the Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee (reference 9076) and the City University of London Sociology Research Ethics Committee (reference Soc-REC/80025567). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Results

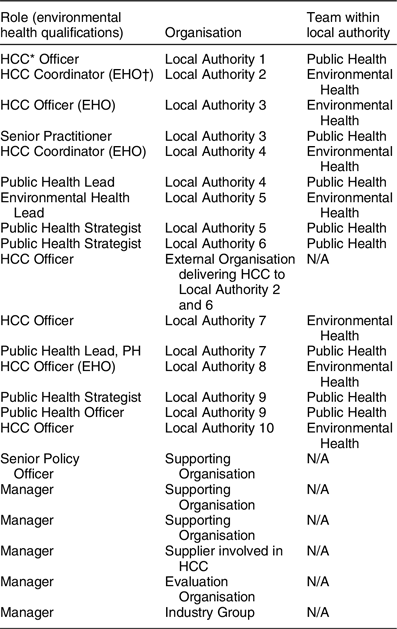

Forty-four individuals were invited to participate in an interview, of which twenty-two participated. Seventeen of these individuals were directly involved in, or supporting delivery of the HCC (representing ten of the potential twenty-four local authorities), and the remainder were individuals who could give context to the HCC. Table 1 describes participant details.

Table 1 Participant characteristics

* Healthier Catering Commitment.

† Environmental Health Officer.

Overview of results

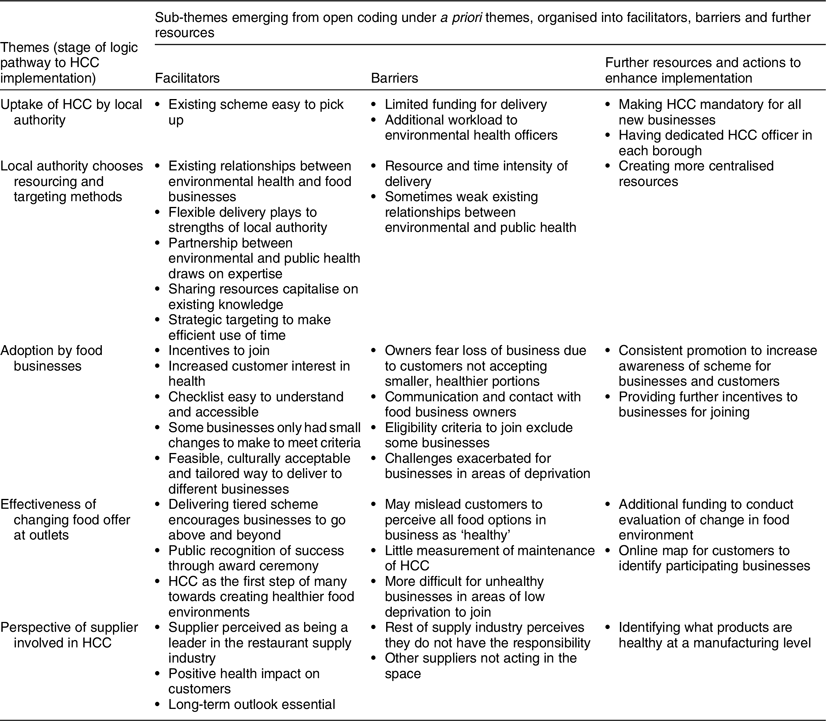

Results are reported according to the stage of implementation pathway: (1) the choice of local authorities to deliver HCC, (2) methods targeting food businesses, (3) the adoption of HCC by food businesses, (4) the effectiveness of the HCC at increasing the healthiness of the food environment within these contexts and (5) the supplier perspective. Within each stage, results are organised according to barriers, facilitators and participant recommendations (presented in matrix form in Table 2).

Table 2 Summary of barriers and facilitators emerging from participant interviews

Uptake of Healthier Catering Commitment by local authority

Facilitators

The local authorities interviewed perceived the HCC as a key part of a package of strategies designed to improve food environments to deliver on their commitments to improve diet-related public health in their communities. HCC officers reflected on many positives of the initiative, stating that it was easy to deliver, recruit and assess due to the existing resources and documents available.

‘…in terms of the actual package and the resources available, it’s quite easy to pick…I mean it’s not like myself or anybody in the council needs to develop it further’ HCC Officer, Local Authority 7

Barriers

Participants reflected on why other local authorities did not deliver the HCC, or stopped delivering it, noting that there had been limited or reduced funding to local authorities as a whole, and Environmental Health teams in particular. Funding for HCC was largely focused on employing HCC Officer/s.

‘…a lot of local authorities have faced funding cuts, so they just cannot dedicate the same resource and capacity to delivering the HCC.’ Project Officer, Supporting Organisation 1

Further resources and actions to enhance implementation

Participants spoke to the idea of making HCC mandatory for all new businesses and suggested that having a dedicated HCC Officer in each borough would enable them to deliver the initiative to more businesses.

‘I think it should be mandatory…because it’s not too hard to implement, especially if new premises are coming.’ HCC Officer, Local Authority 10

Choosing resourcing and targeting methods

Facilitators

Not only was the HCC seen as easy to deliver but also delivery could be tailored to the existing strengths and resources of the local authority. Among interviewed local authorities, delivery was done by (1) a dedicated Environmental Health Officer (EHO) who delivered HCC with the support of the public health team, (2) all EHO delivered the initiative as part of their normal duties or (3) delivery was contracted to an external organisation. Delivery of the initiative via an external organisation played to the strengths of this particular community; the organisation in question had existing ties to the community, experiences working in food environments and was able to assign more time to deliver the initiative than the EHO. In contrast, the benefit of using EHO was that in their role as a local authority representative, business owners were more familiar and responsive to their approaches to join. Delivery was usually enacted through both public health and environmental health teams through varying different means (as described above) and was seen to capitalise on the expertise of each department.

‘HCC is mainly driven by environmental health…[and] I borrow the nutritionist’s expertise from the health and wellbeing team’. HCC Officer, Local Authority 5

Resourcing of the HCC officer varied across councils, from a dedicated full-time position, to one with one day a fortnight, reflecting the different prioritisation of the local authorities. Some HCC officers had targets on how many businesses to sign up.

‘And, within each of the environmental health officers’ remit [they] are…given a target to sign up new business to Healthy Catering Commitment.’ Public Health Lead, Local Authority 5

There was divergence in how participants viewed the role of the EHO in relation to HCC delivery. EHO most commonly interact with businesses through the monitoring and enforcement of mandatory food safety regulations. This existing relationship gave them the opportunity to deliver the HCC initiative, but created a challenge in terms of differentiating between the mandatory (food safety) and voluntary (HCC) initiatives. Some participants viewed this factor as important in getting businesses to consider the HCC, while others reflected that they wanted to ensure the voluntary nature of the initiative was clear.

Participants drew heavily on shared resources to deliver the HCC, making efficient use of existing tools, and drawing on knowledge and expertise. These were drawn from three sources: (1) the HCC network, where HCC officers were able to share new techniques and resources (e.g. flyers), while coming up with solutions together; (2) resources shared across local authority, for example, drawing on nutrition expertise in another local authority and (3) resources shared within council, for example, relying on the environmental health officers to identify which food businesses may be more willing to sign up to the HCC, or the use of internal printing services.

‘… the [Healthier Catering Commitment] network is so great, when I drop an email…they would ask their nutritionist on my behalf.’ HCC Officer, Local Authority 7

Due to limited resources, HCC officers focused on being strategic, practical and effective with the delivery of the initiative. For example, one geographical location would be targeted at a time, chosen by areas of highest obesity rates, surrounding schools or being located on a busy high street. Types of cuisines were also targeted at the same time, allowing the HCC officers to understand what healthy changes were feasible and likely to be culturally acceptable, and used this approach for similar businesses. This approach enabled HCC officers to play on the competitive nature of the businesses, by noting that competitors had signed up to the initiative and would attract more customers as a result.

‘…we also found it quite useful to target one type of business at a time, for example, at one point we did most of the falafel shops in the borough and that was quite useful in terms of knowing how they prepare the food and that gives us - it makes us an expert in one area.’ HCC officer Local Authority 4

Barriers

The task of engaging owners and supporting changes was viewed as time and resource intensive, with varying rates of success. Getting in touch with the correct person, convincing them to join, and walking them through the changes often required several onsite visits to each business. HCC officers often completed HCC work as one aspect of their role in the local authorities and therefore had to balance competing demands. HCC officers were often required to seek nutrition information from other sources.

‘… it’s just been very difficult to get businesses to be interested because these are often people we can’t even get hold of. It’s difficult to get hold of owner, they’ve got staff working in these places and you can’t even get to the owner.’ Public Health Lead, Local Authority 7

For some local authorities, the cross-departmental relationship between Public Health and Environmental Health required to deliver the HCC could be strengthened, with inherent tensions existing that come from working across councils (e.g. competing or different priorities).

Further resources and actions to enhance implementation

There was ongoing resource and tool development that participants believed would aid further recognition, uptake and customer demand for HCC. This included promotional materials being developed by the Greater London Authority. These promotional materials were part of a larger movement towards centralised resources and greater involved of the Greater London Authority. Increasing the consistency of branding and awareness of HCC across London would improve the uptake of the initiative by businesses and raise awareness amongst customers.

‘And then as I said, the resources that they’re now creating, I don’t know how they’re going to work, but there’s never been any publicity at all ‘cause it’s all been disparate. Different boroughs have put different amounts of money into it, it’s all been very disparate, and different boroughs are doing different things. So to make it more unified, maybe, across London.’ HCC Officer, External Organisation delivering to Local Authority 2

Adoption by food businesses

Facilitators

Participants encouraged businesses to join by conveying the following potential benefits: a growing demand for healthier options; discounted products from a supplier; promotion by the local authority; offering discounted hygiene and allergy training and that it was free to join. Perseverance was key to engaging businesses, particularly in overcoming the challenge of getting in touch with owners and managers. HCC officers found that being persistent, flexible with visiting times, and taking the time to communicate with and address concerns of the owner were essential to engagement.

‘Publicity is a good offering. Any business would love to get free publicity. We offer free food hygiene training and obviously it’s the sticker and being able to be identified with being a healthier premises, or at least an award-winning premise. … And those sort of forward-thinking premises would love to jump on this.’ HCC Officer Local Authority 8

Another engagement method was highlighting the potential benefit the business could make to the health of the community, by reflecting on the high obesity rates of children in their local area, and how unhealthy food contributes to this phenomenon.

‘…I talk about sort of local, the fact that obesity is quite high in [Local Authority 7] compared to other parts of London or nationwide’. HCC Officer, Local Authority 7

“…I try to explain how, regarding their type of business, how we can contribute to the public health or the health of the population in [Local Authority 3]. HCC Officer, Local Authority 3

Some businesses were more open to joining the initiative: where the owner or chef has an existing interest in nutrition or had a personal experience with nutrition-related chronic diseases, and/or when they perceived a benefit in terms of attracting customers. Businesses that that were already selling some healthy food or that already met some requirements (e.g. kebab shops already served vegetables as sides) showed more interest. HCC officers capitalised on this by initially identifying what criteria the premise was already meeting. The HCC checklist enabled them to demonstrate what small achievable steps could be made, was a good talking point, and easy for business owners to understand. Furthermore, it did not require a dietitian to deliver.

‘We’re also recognising, in that process, premises that are already doing or that are already half-way there, perhaps they serve really healthy vegetables and vegetables are at the forefront of the display and that’s really positive. So we can work on the positives and suggest that they make one or two changes, in addition to that.’ HCC Officer, Local Authority 8

Across local authorities, HCC officers commonly reflected on having a tailored approach to each business, depending on the owner, location and type of food business. In particular, being cognisant of how the initiative could be delivered within different language and cultural contexts was essential in adoption by businesses. For example, creating language-specific information sheets was essential in communicating the correct information.

‘You have to understand their business or the culture around their business … to be able to assess how you can do the HCC or how they can do the HCC.’ HCC Officer, Local Authority 3

Barriers

Participants reflected on owners’ reluctance to join, citing a fear of negative business outcomes, prioritisation of selling high volumes of unhealthy food for as cheap as possible to maintain competitiveness and value for money, with the alternative driving customers elsewhere. Business owners were concerned that it would cost time and money to implement and were limited in some aspects of change, for example, had been given drink fridges or menu boards from food and beverage companies.

‘[Business owners] see it as something that’s going to cost them, and it’s difficult in some cases to see that they could benefit from that by serving smaller chip portions.’ HCC Officer Local Authority 2

Cultural differences meant that some healthier options would be unfamiliar to customers, or challenging to implement due to traditional cooking techniques. Access to healthier ingredients that met religious specifications was also challenge for some business owners (i.e. accessing low-fat dairy products for Jewish business owners). Owners often failed to see the advantage in joining, given there were limited incentives to offer. Low recognition of the initiative was also seen as an issue, while some owners did not understand the initiative or had little health knowledge. Language barriers often limited successful communication between HCC officers and business owners.

‘Another challenge is that there is sometimes language barriers, communication. A lot of businesses don’t have an email address or don’t answer the phone.’ HCC Officer, Local Authority 1

Maintaining HCC was a challenge, and without ongoing pressure, businesses could return to their old modes of operation and would automatically lose eligibility for the initiative if their hygiene rating fell below a certain level. Some local authorities addressed this by working with businesses to increase their hygiene rating while implementing HCC.

‘I’ve also gone back to some now to make sure they’re still maintaining, not fallen off, you know. And most of them have maintained the criteria. And sometimes… some have had to drop some of things.’ HCC Officer, Local Authority 4

Areas of deprivation experienced the aforementioned challenges more acutely and were harder to engage; they were more likely to be micro-businesses with low margins, more likely to drop in and out of meeting hygiene criteria and had a higher number of customers that were seeking value for money (i.e. large portion sizes at low costs).

‘There was the challenge of going to more deprived areas that the businesses that are located in the most deprived areas of the borough, they tend to have, as a whole, tend to have lower food hygiene so we were trying to target them.’ HCC Officer, Local Authority 1

There were also constraints where businesses that only sold a small number of products were ineligible to join. Some businesses found it harder to meet the requirements, particularly if they predominantly sold fried food – indicating that the least healthy businesses may remain so.

Further resources and actions to enhance implementation

Increasing the awareness and (consistency of) publicity of HCC was viewed as essential in both harnessing the existing desire for healthier options from customers, and in creating a ‘tipping point’ of enough food businesses joining HCC to influence others to do the same. Being able to provide further incentives was also seen as a method of encouraging businesses to adopt the initiative.

Effectiveness at changing the food offer

Facilitators

Respondents from four of the ten local authorities interviewed mentioned using a tiered version of the HCC initiative, where there were additional benefits to meeting more of the criteria, for example, having a bronze, silver and gold level. This was seen to encourage businesses to continue to make healthy changes above and beyond the minimum requirements for joining.

‘…it just encourages those businesses that are really keen to make further changes and those who are at - they have a very high nutritional standard of food can apply to go on silver and gold.’ HCC Officer, Local Authority 1

Three of the local authorities interviewed had award ceremonies where they would recognise businesses that had exemplified shifts to healthier food provision. An HCC twitter account that promoted new businesses that had joined the initiative was a useful way to encourage customers to engage in the HCC.

HCC was often viewed as a ‘foot in the door’ and starting point towards creating healthier food environments, by changing the expectation of what businesses could achieve, and customer demand for healthier options, and thus shifting the culture around healthy food service. Rewarding businesses for making small changes was a long-term investment that could pave the way for further changes to be made at a later stage.

‘Because the good thing about the scheme is that it does recognise small changes and therefore it gives more avenue for more changes in future.’ HCC Officer, Local Authority 8

Barriers

With more focus on recruitment over maintenance and evaluation of the changes, it was difficult to understand the impact of the initiative on customer behaviours and diets. Participants thought that more could be done to leverage recruited food business to make further changes in becoming healthier and that resources or funding specified for evaluations would help measure the impact of HCC implementation on the healthiness of food environments.

‘How do we monitor it afterwards to make sure that things are happening? So that it doesn’t become too costly for us to do it.’ Public Health Lead, Local Authority 6

‘I really do think that in general the HCC isn’t given enough leverage afterwards. It’s very easy to recruit and maybe do that assessment, and then what?’ HCC Officer, External Organisation delivering to Local Authority 2

In contrast with the benefit of recognising was the concern that HCC could create a ‘halo effect’ whereby takeaways that were still largely unhealthy food environments could be viewed as generally healthy because of the award.

‘… there’s a lot of things on that menu that aren’t healthy, especially in a take-away or a café that does fried food…’ HCC Officer, External Organisation delivering to Local Authority 2

This concern was particularly revealed in the approach taken by different authorities. Many HCC officers reported that they aimed to get as many businesses to sign up as possible, with some EHO having their yearly goals or Key Performance Indicators include having a specific number of businesses signed up. Other local authorities noted that there could be more benefit by maximising the healthiness of fewer businesses. Participants reflected that it was possible for all food businesses to be healthier.

Further resources and actions to enhance implementation

Participants considered that there would be greater impact of the initiative if customers were able to locate the businesses that had been awarded the HCC. There was also discussion of an online map being developed that would enable this to occur.

Perspective of supplier involved in HCC

Facilitators

The supplier involved in the HCC noted that their business had invested time and resources into the initiative, for example, offering a short-term discount on healthier products. They viewed their involvement as good for their long-term business and good for their customers, while creating a positive image of the company itself through favourable media pickup.

‘We are still being perceived in the marketplace as the leaders in what we are doing here.’ Manager, Food supplier

Barriers

While supportive of HCC, the supplier noted that not many food businesses had taken advantage of the discount available on healthier options. Part of the motivation to be involved was recognition of responsibility they played in supplying unhealthy products, and the potential role in promoting healthier options, while recognising that manufactures had a big part to play as well.

‘… if I was to put my business hat on for the amount of time and effort and money that we put into this, it hasn’t given us a return. But again, I default back to my earlier answer which is we still see it as a long-term investment. We still see it as the right thing to do and we intend to keep following this path.’ Manager, Food supplier

Further resources and actions to enhance implementation

The supplier noted that other businesses may not see it as their responsibility to contribute to the healthiness of the food supply. Making it clear which options were healthier at a manufacturer and/or supply level was recommended to further aid healthiness of food provision.

Discussion

This study offers a unique and in-depth examination of the barriers and facilitators to delivering the London Healthier Catering Commitment from the perspective of local authorities and offers key insights into how local governments in other contexts can facilitate successful implementation of food service initiatives.

There were many factors that supported the uptake of the HCC by local authorities, including the existence of a fully formed initiative, and the sharing of resources, networks and knowledge. Participants universally viewed the HCC network as an integral strength and resource that they relied upon to share knowledge and learn from each other. The flexibility of the initiative meant that it could be delivered differently across local authorities, a positive given their different structures, relationships and strengths. Strategic targeting of businesses and demonstrating culturally appropriate methods to meet the requirements engaged businesses; however, low recognition of the initiative and fear of customer loss were main obstacles in adoption. Participants identified a number of actions that would aid implementation, including consistent and London-wide promotion of the initiative to both businesses and customers to increase recognition and demand, making HCC mandatory for new businesses, increased funding for the role of HCC officers and towards evaluation of changes, and identifying healthier options at a manufacturing level.

There is a paucity of research that examines the implementation of local government-led healthy food service policies, reflecting perhaps a lack of these policies in the first place, and the lack of research literature that investigates them. Below we explore our results in the context of other local government delivered initiatives(Reference Goffe, Penn and Adams25,Reference Bagwell37,Reference Papadaki, Alventosa and Toumpakari38) as well as experiences of other implementors (e.g. researchers) who have partnered with small grocery stores(Reference Gittelsohn, Laska and Karpyn39) and restaurants(Reference Economos, Folta and Goldberg40–Reference Nevarez, Lafleur and Schwarte43).

In our study, the uptake and delivery of initiatives by local authorities were limited by reduced or restricted funding, a common finding in similar studies in local governments(Reference Goffe, Penn and Adams25,Reference Bagwell37) . Existing relationships between different parties, between environmental health and public health, and between HCC officers and business owners was seen to facilitate the delivery of the HCC; a finding echoed in previous literature(Reference Goffe, Penn and Adams25,Reference Hanni, Garcia and Ellemberg42) .

We found that there were many engagement strategies that were echoed in previous literature, including making small changes at a time(Reference Bagwell37,Reference Gittelsohn, Laska and Karpyn39) , offering incentives such as publicity and free training(Reference Goffe, Penn and Adams25,Reference Bagwell37) , considering the financial impacts(Reference Goffe, Penn and Adams25,Reference Bagwell37) , delivering tailored and intensive interventions(Reference Goffe, Penn and Adams25,Reference Gittelsohn, Laska and Karpyn39) , the importance of considering language and cultural language differences(Reference Goffe, Penn and Adams25,Reference Gittelsohn, Laska and Karpyn39) and highlighting the potential community benefit(Reference Gittelsohn, Laska and Karpyn39,Reference Hanni, Garcia and Ellemberg42) . Similarly, many of the challenges to business engagement had been previously discussed, such as the reluctance to change(Reference Bagwell37), the perception that healthy food was not popular with customers and would result in economic losses(Reference Bagwell37–Reference Gittelsohn, Laska and Karpyn39), working with limited resources(Reference Goffe, Penn and Adams25) and a lack of interest from food business owners(Reference Goffe, Penn and Adams25). This study highlighted that local authorities had difficulty in engaging businesses in areas of deprivation, citing lower hygiene ratings, lower profit margins and customers with more sensitivity to changes in price and portions. This echoes the findings of a survey of UK local authorities and food businesses implementing various healthy food service initiatives in areas of deprivation(Reference Bagwell37).

The supplier involved in the HCC viewed their involvement as contributing to social good and as a strategic short- and long-term investment. While little other research has explicitly examined the perspective of suppliers, other retailers have expressed that healthy food policies contribute towards community stewardship(Reference Blake, Backholer and Lancsar44) and make good business sense(Reference Boelsen-Robinson, Blake and Backholer45).

Participants identified that greater and more consistent promotion of the HCC would enhance uptake by businesses and increase customer demand, consistent with findings from Bagwell(Reference Bagwell37) where there was confusion over different food service initiatives.

Strengths of this study include that 10 boroughs were included in the research, and multiple participants were requested from each of these, although not all participated. This allows us to gain multiple perspectives, which is of importance when considering the joint public health and environmental health delivery and interest in the initiative. Furthermore, the inclusion of auxiliary interviews provides a deepened contextual view of the initiative, its challenges and the policy implications. A further strength is that one researcher conducted the interviews and analysis, thereby having a deep knowledge of the data.

This study is susceptible to selection bias, in that it is likely that local authorities who are succeeding and more invested in delivering the HCC would agree to participate. A further weakness is that not all local authorities delivering the HCC agreed to participate, however all were invited. Future research could also explore what is holding back local authorities that are not engaging with the HCC or other healthy food retailers to gain a deeper understanding of the barriers in the first step of choosing to take up the HCC. Business owner and customer perspectives were not captured in this study, which have been explored previously(Reference Bagwell46). It is valuable to capture perspectives from multiple stakeholders to further elucidate the potential of food service initiatives to increase the provision and purchase of healthier foods, and how they could be incentivised. Further research could explore the impact of the HCC on customer nutrition choices, to add to the existing literature demonstrating that increasing the availability of healthier options and decreasing unhealthy options in restaurants lead to increased healthiness of the food environment(Reference Lindberg, Sidebottom and McCool47,Reference Martinez-Donate, Riggall and Meinen48) and improved consumer choices(Reference Valdivia Espino, Guerrero and Rhoads49). Several HCC-specific recommendations arose from the current study which are in response to the identified barriers:

-

- Consider how further incentives could be provided to businesses for meeting HCC criteria in order to engage businesses and encourage adoption.

-

- Targeted strategies for deprived areas that focus on their specific barriers to eligibility and adoption (e.g. developing menu items that are low-cost healthier alternatives, providing methods to reduce food wastage, increasing their food safety rating).

-

- Consider how to further leverage participating businesses to make additional changes to increase the healthiness of food environments (e.g. through using tiered versions of the HCC).

-

- Consider the balance between a focus on the quantity of businesses recruited to the HCC, and quality (i.e. extent of change of healthiness of food environment, maintenance of changes, demonstrated impact on purchases) and take a unified approach throughout.

-

- Evaluate the sustainability and maintenance of HCC changes within different businesses to determine how the healthiness of options in food outlets is changing.

-

- Investigate if and how businesses are using supplier discounts, and how this impacts HCC maintenance and business outcomes (e.g. profit margin).

Reflecting on the strengths of the HCC and how they might function in other contexts, the current study elucidated lessons for other local governments exploring the potential of delivering healthy food service initiatives:

-

- Use the existing networks and relationships between local governments, community-based organisations and local food businesses to develop community-tailored delivery methods.

-

- Identify the strengths, reach and capacity within local governments and across departments (i.e. environmental and public health) to capitalise on existing expertise.

-

- Understand the density, cuisine and ownership of food outlets in order to develop practical, culturally relevant and efficient delivery methods (e.g. in areas of low food outlet density assign initiative delivery to all EHO who would be visiting these premises anyway).

-

- Reflect and revise the standards of entry to the initiative, or consider adding additional ‘tiers’ as more businesses become successful in their goal of creating healthier food environments to leverage already engaged businesses to become even healthier.

-

- Explore how to increase awareness of the initiative amongst businesses and create demand for customers (i.e. simultaneously work on supply and demand driven factors, such as customer demand for healthier options(Reference Gittelsohn, Laska and Karpyn39)).

Conclusion

In this study, we consider multiple aspects of local authority decision-making and involvement in the Healthier Catering Commitment initiative. Local governments and other organisations seeking to improve the healthiness of offerings in food service outlets in their jurisdictions should consider existing interactions with food service outlets as avenues for initiative engagement and delivery, and the use of personnel resources in a targeted manner. Working closely with food outlet owners and managers to implement healthy changes that are acceptable to their customers and which maintain business profits is likely to enhance the maintenance and sustainability of such changes. The exacerbated challenges of initiative engagement, delivery and maintenance in food outlets within areas of disadvantage means these businesses are likely to require additional support.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: We would like to thank the study participants for giving their time to this study. Funding support: T.B.R. is supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship and a National Health and Medical Research Council Centre for Research Excellence grant (APP1152968). A.P. is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council fellowship (GNT1045456) and Deakin University. A.M.T. is supported by the University of Sydney. C.H. is supported by City University, London. Funding sources had no involvement in the study design, the collection, analysis and interpretation of data, in the writing of the report, or in the decision to submit the article for publication. Conflict of interest: All authors report no conflict of interest. Author contributions: T.B.R., C.H. and A.P. designed the study. T.B.R. coordinated and conducted data collection. T.B.R. and A.M.T. conducted data analysis. T.B.R., C.H. and A.M.T. interpreted the data. All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving research study participants were approved by the Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee (reference 9076) and the City University of London Sociology Research Ethics Committee (reference Soc-REC/80025567). Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects/patients.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980020002323