The literature on party competition has typically stressed long-term trends. However, change to the political agenda may also occur quickly, facilitated by extraordinary events: In 2013, immigration was a minor concern in the German elections with less than five percent of parties’ media statements dedicated to the issue. At the next election in 2017, 19 percent of such statements concerned immigration (Hutter and Kriesi, Reference Hutter and Kriesi2018). This can be interpreted in different ways. Was it the long-term transformation of the German party system and the rise of the immigration-critical Alternative for Germany (AfD)? Or was it events external to the party system such as the humanitarian crisis of 2015 and Merkel's handling of it that played a pivotal role here? In short: What determines the changing politicization of immigration in Germany and elsewhere?

We argue that events like the 2015 crisis play a crucial role in the short-term politicization of issues. We build on two findings: Among long-term trends, scholarly literature has established the role of radical right parties in increasing the salience of immigration (Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008; Alonso and da Fonseca, Reference Alonso and da Fonseca2012; Green-Pedersen and Otjes, Reference Green-Pedersen and Otjes2017; Dancygier and Margalit, Reference Dancygier and Margalit2019). However, research has also established that attention to issues few citizens have personal experiences with—like immigration—crucially depends on information through media and public discourse (Green-Pedersen, Reference Green-Pedersen2019, p. 83). Building on this, we argue that both factors interact: events like the humanitarian crisis of 2015 move an issue into the spotlight. This provides radical right parties with an opportunity to further politicize immigration (e.g. Mader and Schoen, Reference Mader and Schoen2018). Moreover, they increase the pressure on mainstream parties to respond to their radical right challengers—a crucial factor that previous research has highlighted (Bale, Reference Bale2003; Meguid, Reference Meguid2005, Reference Meguid2008; Bale et al., Reference Bale, Green-Pedersen, Krouwel, Luther and Sitter2010; Van Spanje, Reference Van Spanje2010; Meyer and Rosenberger, Reference Meyer and Rosenberger2015; Green-Pedersen and Otjes, Reference Green-Pedersen and Otjes2017). So how does the pressure of rising public attention to immigration change mainstream parties’ reactions to the radical right in terms of salience and positional change?

We test our argument with a dynamic analysis of party competition around immigration in the context of the 2015 refugee crisis in Austria, Germany, and Switzerland. For this, we compile a novel data set on parties’ immigration emphases and positions at the monthly level based on press releases. This allows us to disentangle the different mechanisms in very short time intervals and to study the interaction between the external shock of the crisis and the continued pressure by radical right parties. Most scholarly work on the politicization of immigration and the role of radical right parties has built on temporally coarse “snapshot data” coming from electoral manifestos and election campaign coverage that lack a more-fine grained, dynamic account of changes. Hence, we advance research on immigration politicization by zooming in on the refugee crisis. This is important for two reasons. First, events like the humanitarian crisis of 2015 rarely coincide with elections so that classical campaign-centered approaches to party competition (e.g., Green-Pedersen, Reference Green-Pedersen2007; Hutter and Kriesi, Reference Hutter and Kriesi2019; Volkens et al., Reference Volkens, Lehmann, Matthieß, Merz and Regel2016) cannot gauge the impact of the crisis. Second, studying salience in very close, i.e. monthly, intervals enables us to uncover more immediate dynamics of how parties react to developments internal and external to the party system.

Our empirical approach incorporates three steps. First, out of 120,000 press releases from all major parties published between 2013 and 2018, we identify those concerned with immigration through a novel dictionary. The proportion of these immigration-related press releases provides us with a monthly measure of the each party's immigration salience. Second, we estimate parties’ immigration positions using a Wordscores model. Finally, we use our measures for descriptive and time-series regression analyses.

We show that the crisis moved mainstream parties to address the immigration issue, regardless of its prior party-specific salience. Immigration salience increased for all parties with the beginning of the refugee crisis. In line with previous research, we show that radical right parties addressed immigration by far the most throughout the crisis period. However, increasing levels of salience by radical right parties are associated with an immediate rise in attention to immigration by mainstream parties. In contrast, we do not find the same for positions, where changes for mainstream parties are not clearly driven by radical right parties. We also qualify previous manifesto- and media-based studies’ findings (Grande et al., Reference Grande, Schwarzbözl and Fatke2019; Hutter and Kriesi, Reference Hutter and Kriesi2018) on the post-crisis period as we show that salience returns to the pre-crisis level for most parties toward the end of the crisis. Understanding the trend allows an interpretation of such snapshot data as part of a declining trend, rather than a sign of emerging politicization.

Overall, we contribute to the measurement of party positions on the immigration issue, as well as to the understanding of an important episode in European politics, the 2015 refugee crisis. We believe that studying parties’ strategic responses to events in the field of immigration is crucial—not only for understanding the specific moment but also for the radical right's broader impact on the politicization of immigration as mediated through mainstream parties.

1. Politics of immigration and the refugee crisis

Our analysis builds on the premise that the refugee crisis had a direct effect and radically changed the importance of the immigration issue in the short run.Footnote 1 We argue that highly salient public events like crises have important indirect and immediate effects that change the “rules of engagement” on an issue. They put topics on the party-system agenda and hence force other parties to address an issue, whether it is beneficial to them or not. As changes in the salience of an issue may lead parties to adapt their positions (Abou-Chadi et al., Reference Abou-Chadi, Green-Pedersen and Mortensen2020), crisis events have the power to reshape party strategies and may have long-lasting consequences.

We build our argument in several steps: First, we argue that the crisis increases the general salience of immigration due to parties’ quest to appear responsive. Second, we posit that the crisis also changes the “rules of engagement” since it affects the reactions of mainstream parties to right-wing challengers whom the crisis presumably benefits. Third, we claim that the established incentives of party competition cause heterogeneity in this reaction that leads center-right parties to respond more strongly.

1.1 The direct impact of the crisis

Multiple factors determine parties’ salience strategies (Green-Pedersen, Reference Green-Pedersen2019, pp. 24–40). While the literature has typically highlighted parties’ ideological profile and the structure of party competition, we focus on more variable determinants. Specifically, we argue that events like the 2015 crisis have a powerful role in shaping salience strategies by increasing the so-called “problem pressure” (Green-Pedersen, Reference Green-Pedersen2019, p. 22). The enormous news coverage of the refugee crisis (Greussing and Boomgaarden, Reference Greussing and Boomgaarden2017; Harteveld et al., Reference Harteveld, Schaper, De Lange and Van Der Brug2018) and the importance citizens attribute to the topic during this period (European Commission, 2018) force parties to address the issue.

Previous studies have shown that parties’ salience and positional strategies often depend on the public salience of issues and issue priorities of voters (Sides, Reference Sides2006; Klüver and Sagarzazu, Reference Klüver and Sagarzazu2016). Similarly, literature on election campaigns has argued that “riding the wave,” i.e. campaigning on issues that dominate the news cycle, provides politicians with an immediate opportunity to appear concerned and responsive (Ansolabehere and Iyengar, Reference Ansolabehere and Iyengar1994). Hence, we expect the salience of immigration in party competition to increase for all parties.

Hypothesis 1: Parties increase their attention to immigration with the start of the refugee crisis.

1.2 Changing responsiveness to challengers

However, our argument extends beyond a direct response to the crisis once we consider mainstream parties’ responses to challenger parties, one of the main drivers of change in party competition (Hooghe and Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2017; Hutter et al., Reference Hutter, Kriesi and Vidal2018). We build our theoretical model on Reference MeguidMeguid's seminal framework (Reference Meguid2005, Reference Meguid2008): She argues mainstream parties may respond to the electoral success of niche parties by (a) ignoring the issue, (b) actively mobilizing against the niche party's position with an adversial position, or (c) adopting the niche party's position to win back voters.

Applying this model to gauge mainstream parties’ immediate reactions to challengers during a crisis, rather than long-term responses in the context of their electoral success, comes with important adaptations. Meguid's model assumes that reactions in terms of salience and positions are inherently tied. Extending her approach and applying it to shorter time intervals, we conceptualize mainstream parties’ responses as a two-step decision: Parties first need to decide whether to address an issue more, i.e. increase its salience. In a second step, parties decide whether an increase in salience is accompanied by a change in their issue position. Namely, they may accommodate the challenger's positions, stick to their previous position, or articulate an explicit counter-position. This allows for courses of action which Meguid's framework does not foresee, e.g. parties may decide to engage with an issue without altering their position at all. While in some cases altering both salience and positions might seem beneficial, other situations may require strategic action only regarding salience. Separating these two dimensions of reactions is key when mainstream parties respond to external events that relate to the core issues of a challenger rather than the electoral success of that challenger. In such a situation, mainstream parties respond to updated evidence on the importance of a challenger's issue rather than on the popularity of its issue position. Hence, position change may seem less pressing.

Applying this framework to the refugee crisis, we note that despite their diverse ideological appeals, radical right parties are united in their anti-immigration mobilization (Betz, Reference Betz2002; Fennema and Van Der Brug, Reference Fennema and Van Der Brug2003; Ivarsflaten, Reference Ivarsflaten2008). Given their strong emphasis on immigration, these parties have become associated with the issue in the minds of voters in Western Europe, i.e. they have developed a so-called “associative issue ownership” (Walgrave et al., Reference Walgrave, Lefevere and Tresch2012, p. 779; see also Mudde, Reference Mudde2010; Udris, Reference Udris2012).Footnote 2 We argue that the radical right's ownership of the immigration issue posits a dilemma to mainstream parties—particularly during times of heightened attention to the issue.

While we expect that all parties will pay increased attention to immigration in response to the crisis, we believe mainstream parties will additionally raise their responsiveness to radical right emphasis on immigration. As news coverage affects which issues voters base their choices on (Iyengar and Kinder, Reference Iyengar and Kinder1987), increased salience of an issue “owned” by a party may sway voters toward this party (Ansolabehere and Iyengar, Reference Ansolabehere and Iyengar1994; Geers and Bos, Reference Geers and Bos2017; Thesen et al., Reference Thesen, Green-Pedersen and Mortensen2017). Thus, increasing attention toward immigration may benefit radical right parties and thereby put additional pressure on mainstream parties. To counter this, mainstream parties have to challenge the radical right's issue ownership: They can strive to re-gain issue ownership through showing engagement with the issue (Walgrave et al., Reference Walgrave, Lefevere and Tresch2012, Reference Walgrave, Tresch and Lefevere2015). This signals to voters that the party takes a policy problem seriously and does not leave it up to radical right competitors to search for solutions. We think this dynamic—which has mostly been investigated for long-term strategies—should also guide short-term responses as parties struggle to stay on top of the news cycle that may otherwise give a stage to challenger parties.

Thus, a crisis, which naturally attracts media coverage, changes the incentives of mainstream parties and makes them more likely to respond to challenger emphasis on an issue by also engaging with it. Hence, we expect that mainstream parties react to pressure from the radical right by addressing the immigration issue. This should go beyond the general increase in the salience of immigration we outlined in Hypothesis 1 and be driven by radical right parties’ issue emphasis.

Hypothesis 2a: Mainstream parties’ emphasis on immigration increases when radical right parties emphasize immigration.

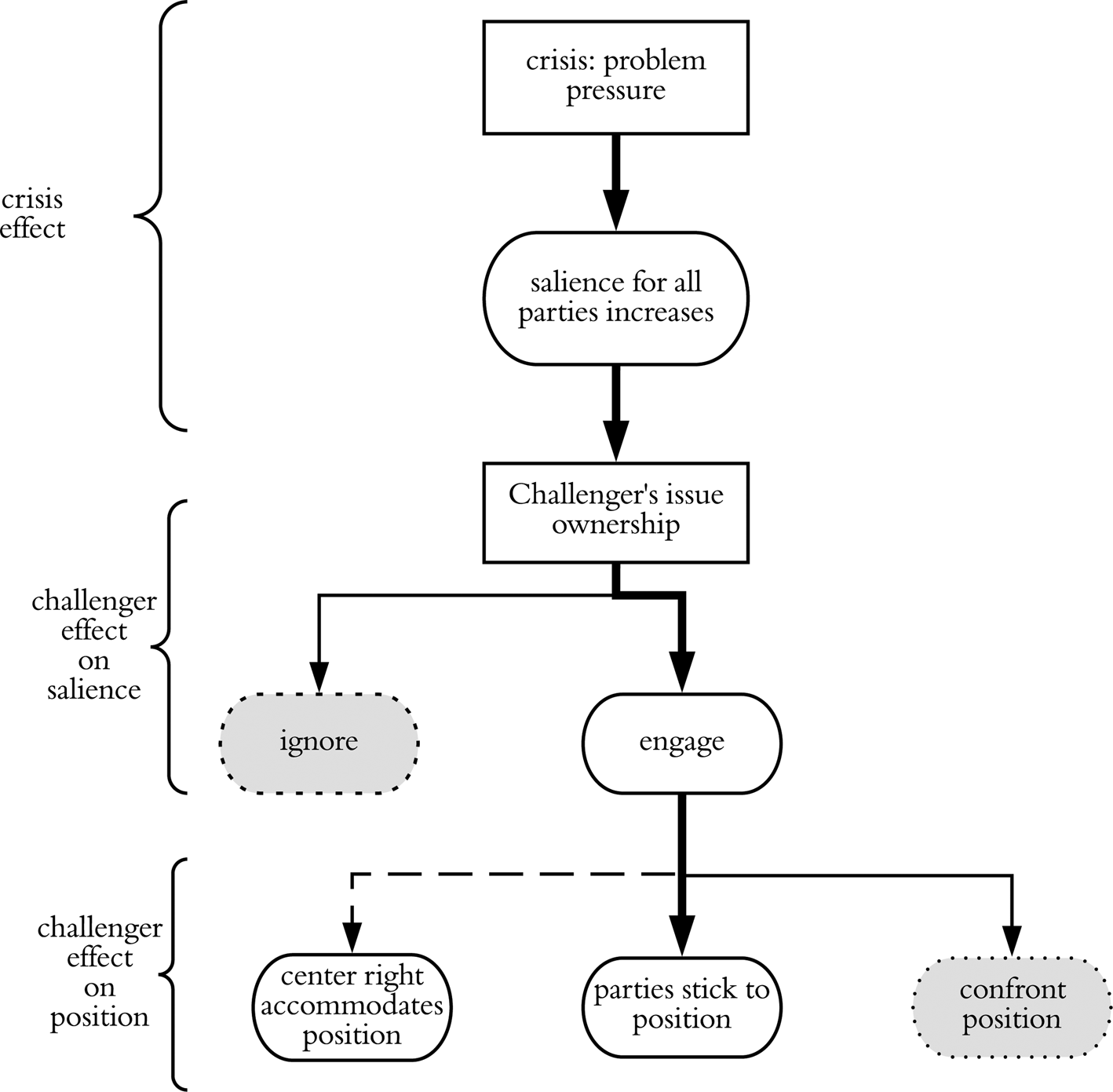

While we argue that parties can hardly afford to ignore the immigration issue in reaction to the refugee crisis and radical right pressure, our two-step interpretation of Meguid's (Reference Meguid2005) framework provides mainstream parties with more leeway regarding their positional reactions (see Figure 1). Hence, we inquire whether mainstream parties remain with their position, choose to actively mobilize against or adopt the radical right's position. While studies of party competition at large have emphasized the stability of party positions over time (Dalton and McAllister, Reference Dalton and McAllister2015), much of the theoretical and case-study literature on immigration focuses on so-called (positional) contagion. These studies suggest that mainstream parties are prone to adjust their position to radical right parties (Bale, Reference Bale2003; Bale et al., Reference Bale, Green-Pedersen, Krouwel, Luther and Sitter2010; Van Spanje, Reference Van Spanje2010; Schumacher and van Kersbergen, Reference Schumacher and van Kersbergen2016). However, results from quantitative, comparative research are inconclusive and show inconsistent effects (e.g., Meyer and Rosenberger, Reference Meyer and Rosenberger2015; Green-Pedersen and Otjes, Reference Green-Pedersen and Otjes2017).

Figure 1. Full model of theoretical expectations.

Given mainstream parties are unlikely to benefit from a long-term politicization of immigration and reactions in terms of position require more intra-party consultation, we expect them to avoid anything that would increase conflict on the issue. In a multi-party system where only the radical right clearly opposes immigration (as predominant in Western Europe), this means other parties should stick to their previous positions and maintain distance from the radical right. We expect parties to instead focus on the pragmatic politics of crisis management. While increasing the salience of immigration, this limits the politicization of immigration and is thus attractive to mainstream parties.

Hypothesis 2b: Mainstream parties do not adjust their position in response to the radical right.

1.3 Partisan differences in responsiveness

Despite our emphasis on the crisis, we do not presume that its effect occurs independent of other factors. Rather, external events interact with the existing context of party competition. Hence, we expect differences between party families’ reactions which are grounded in their relation to the radical right and resulting different incentives to address immigration. Notably, an increasing strength of radical right-wing parties presents a more significant challenge for left-wing parties (Bale et al., Reference Bale, Green-Pedersen, Krouwel, Luther and Sitter2010; Abou-Chadi, Reference Abou-Chadi2016) than for the right.

While increasing importance of immigration as vote-deciding issue may primarily favor the radical right, the tripolar structure of political competition (Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008, Reference Kriesi, Grande, Dolezal, Helbling, Hoeglinger, Hutter and Wueest2012) means immigration can help right-wing parties more broadly. With heightened attention to immigration, radical right challengers may succeed at mobilizing so-called left-authoritarian voters (Van Der Brug and van Spanje, Reference Van Der Brug and van Spanje2009; Lefkofridi et al., Reference Lefkofridi, Wagner and Willmann2014) that might otherwise vote for center-left parties. Here, they do not work as competitors of mainstream right parties but help attract cross-pressured voters toward the right side of the party spectrum (Abou-Chadi, Reference Abou-Chadi2016). This means, even if center-right parties do not manage to gain voters, an increase in the strength of the parliamentary right may provide center-right parties with the opportunity to form a right-of-center coalition. These incentives for center-right parties should especially hold during crises when left-authoritarian voters may be more attentive to immigration. Hence, we expect the outlined salience-based contagion of the radical right to be stronger for center-right parties:

Hypothesis 3a: The radical right-driven increase in salience is stronger for center-right parties than for other mainstream parties.

We are more hesitant regarding positional contagion but suspect center-right parties may be tempted to adopt tougher stances on immigration. This may be driven by the risk of losing voters to intra-block competition: If voters choose depending on parties’ immigration stances during the crisis (Mader and Schoen, Reference Mader and Schoen2018), fear may drive right voters toward the radical right. This makes it more attractive for center-right parties to accommodate immigration-critical stances to prevent a restructuration within the right camp. Another reason is that if the radical right indeed gains in strength following a more permanent politicization of immigration, radical right parties become potential coalition partners whom center-right parties may want to appease (Abou-Chadi, Reference Abou-Chadi2016, p. 423; also Bale, Reference Bale2003). Thus, an increase in positional competition on immigration may broaden rather than limit coalition possibilities for the center-right. Hence, different from the stability we expected in Hypothesis 2b, we posit:

Hypothesis 3b: Center-right parties adjust their position in response to the radical right.

Figure 1 summarizes our expectations. In Hypothesis 1, we outline a “crisis-effect” which leads all parties to increase their immigration salience. Furthermore, we argue that the crisis forces mainstream parties to emphasize immigration in response to radical-right challengers to prevent the electoral success of these challengers (Hypothesis 2a). Despite this increased salience contagion, mainstream parties have little incentive to further politicize immigration by altering their issue positions (Hypothesis 2b). The crisis does, however, not overrule well-established incentives for particular party families. Hence, we expect stronger increases in salience for center-right parties (Hypothesis 3a). Additionally, center-right parties may accommodate their challengers’ positions during the refugee crisis (Hypothesis 3b).

2. Data and methods

2.1 Case selection

As text-based measures of party strategies depend on language, we take a pragmatic decision to focus on Swiss, German, and Austrian parties that publish their press releases in German. While this selection is partially motivated by our methodological approach, we also think the three countries are representative of broader developments in Europe. In what follows, we situate our cases within patterns of party competition in Europe regarding immigration salience, the role of the radical right, and their exposure to the crisis.

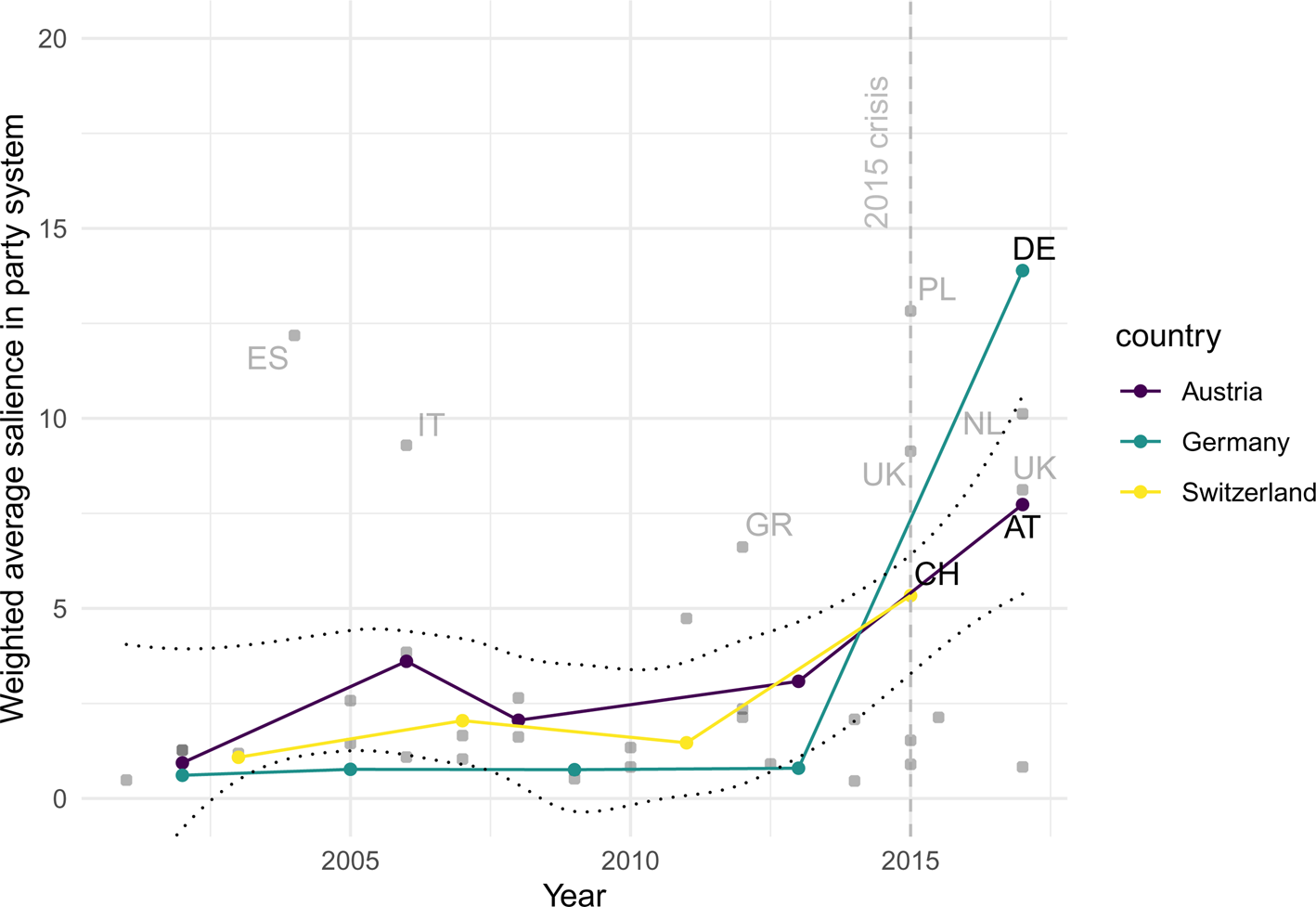

Previous research has established a general trend of rising immigration salience across Europe, mirrored by our three countries under study. Figure 2 shows the salience of immigration in election campaigns in 14 European countries (Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Hutter, Altiparmakis, Borbáth, Bornschier, Bremer, Dolezal, Frey, Gessler, Helbling, Höglinger, Lachat, Lorenzini, Malet, Vidal and Wüest2020). For Austria, Germany, and Switzerland we show patterned lines, while salience in the other countries is shown by grey dots with annotations for important outliers. The dotted area depicts the 95 percent confidence interval around the smoothed trend for all countries. Clearly, all three countries were typical rather than outlier cases compared to the European average, especially in the pre-crisis period.

Figure 2. Salience of immigration in 14 European countries over time.

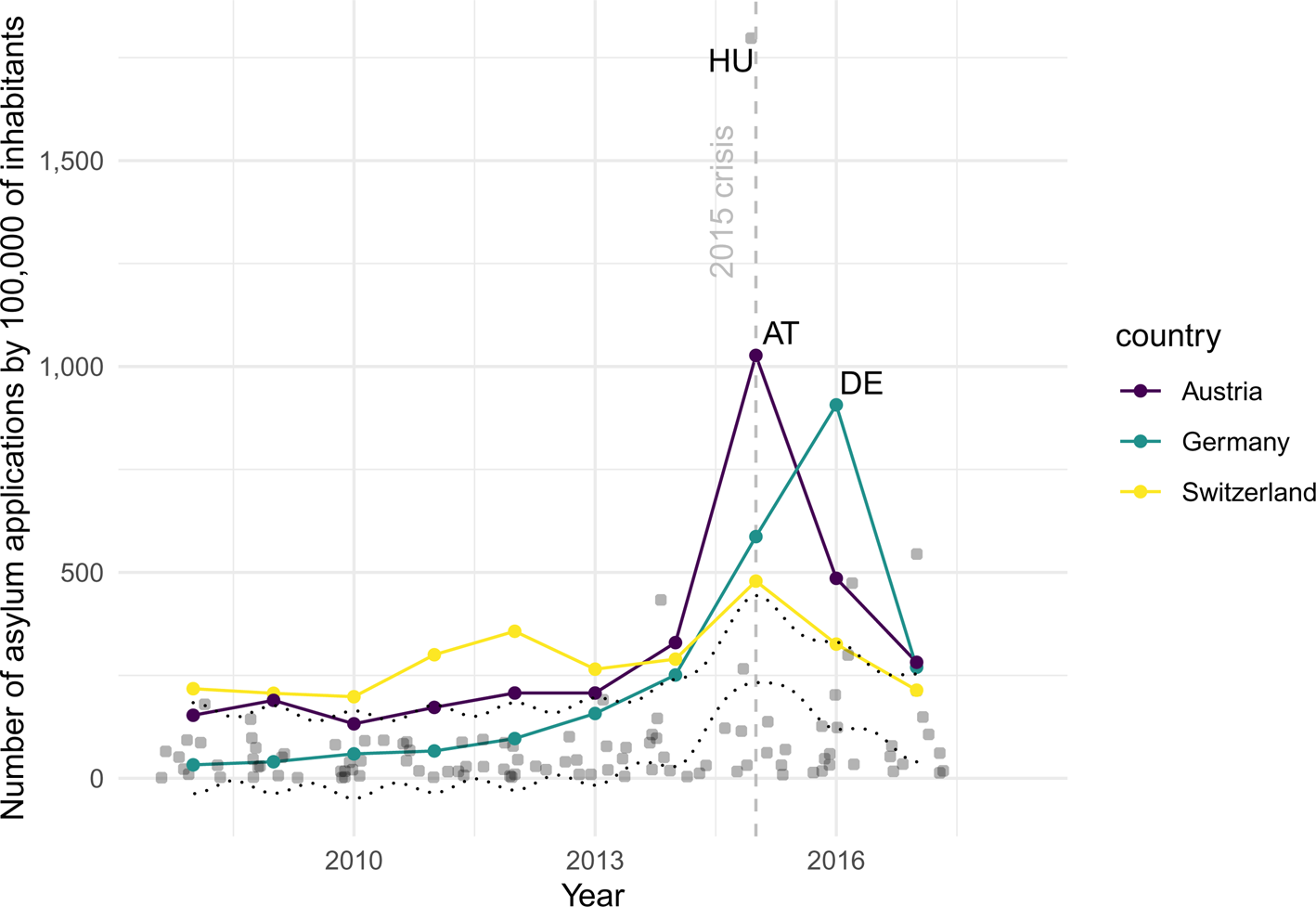

While the 2015 crisis was clearly unique in each country, the countries under study experienced the 2015 crisis at least as much as other European countries. Figure 3 shows the yearly asylum applications in the 14 countries discussed above standardized per 100,000 inhabitants. While public debate and media reporting presented the German case as exceptional, Figure 3 shows that most European countries experienced a peak in refugee arrivals.Footnote 3

Figure 3. Annual Asylum applications in 14 European countries.

Finally, since we argue that the crisis has generally empowered radical right parties to pressure their competitors, we shall emphasize the diverse histories of the radical right parties we treat as functional equivalents during the crisis: Both the Austrian Freedom Party (FPÖ) and the Swiss People's Party (SVP) were mainstream right parties that radicalized toward a nationalist, populist, and anti-immigration position during the 1990s (McGann and Kitschelt, Reference McGann and Kitschelt2005, p. 20; Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008, p. 20). Hence, both parties have also been included in government coalitions. Given the Grand Coalition in the Swiss Federal Council, the SVP has been in government almost without interruption since its foundation. In contrast, the first FPÖ government participation after its ideological turn (in coalition with the center-right ÖVP in 2000) caused domestic and international protest. Nevertheless, the ÖVP both prolonged this coalition and entered another coalition with the FPÖ toward the end of our period of study in 2017. In contrast, the AfD emerged only after 2013. Initially a neoliberal anti-EU party (Bremer and Schulte-Cloos, Reference Bremer and Schulte-Cloos2019), the AfD established itself as an anti-immigration and anti-Islam party already before the crisis and entered parliament in the 2017 election. However, none of its competitors considered the option of a coalition with the AfD, given its pariah status (Bräuninger et al., Reference Bräuninger, Debus, Müller and Stecker2019).

2.2 Research design

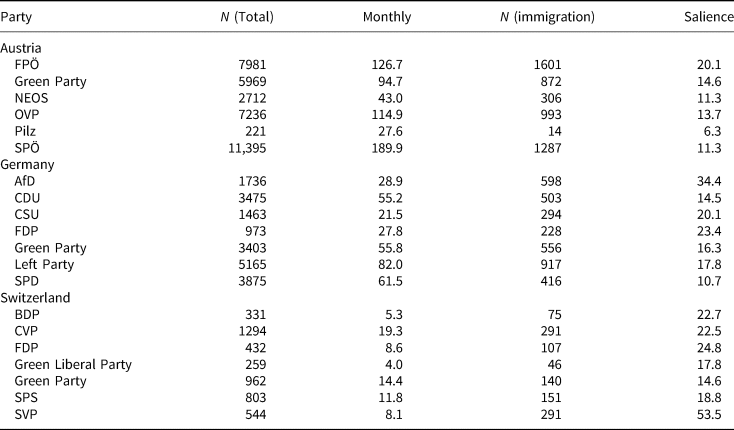

Previous scholarship has often relied on party manifestos, which are written in a complex multi-step process that involves diverse actors (Dolezal et al., Reference Dolezal, Ennser-Jedenastik, Müller and Winkler2012) and only published during election campaigns. We depart from this choice and introduce a novel data set of press releases from Swiss, German, and Austrian parties (see Table 1) which were published by party headquarters and parliamentary groups between January 2013 and March 2018. We collected releases from party web pages and national press release archives, resulting in up to 63 months per country and party. We include all parties that poll above the parliamentary threshold for most of our period of study.Footnote 4

Table 1. Number of press releases

We argue that press releases are highly suitable for the assessment of parties’ immediate and high-pace reactions to the crisis and radical right challengers, which might be missed by other more infrequent data sources. Press releases form a well-established and easily accessible routine tool for parties’ day-to-day communications (Hopmann et al., Reference Hopmann, Elmelund-Præstekær, Albæk, Vliegenthart and de Vreese2012) that has little “institutional and resource constraints” (Meyer and Wagner, Reference Meyer and Wagner2021). Thereby, they enable us to study immediate dynamics of agenda setting using empirical sources that are available continuously and mirror parties’ changing strategies throughout the electoral cycle (Grimmer, Reference Grimmer2013; Klüver and Sagarzazu, Reference Klüver and Sagarzazu2016).

The construction of our dependent variables (DVs) then follows a two-step logic drawing on quantitative text analysis (Benoit et al., Reference Benoit, Watanabe, Wang, Nulty, Obeng, Müller and Matsuo2018). First, we identify all immigration-related press releases using a dictionary. In a second step, we take these press releases and scale them from opposition to support immigration. The detailed approach is described below.

2.2.1 A dictionary approach to immigration salience

To measure attention to immigration, we develop a novel dictionary (see Appendix), based on a close reading of the press releases and drawing on previous approaches (Pauwels, Reference Pauwels2011; Ruedin and Morales, Reference Ruedin and Morales2017). In line with recommendations (Muddiman et al., Reference Muddiman, McGregor and Stroud2018), we restrict our dictionary to words that refer to immigration and integration, avoiding overly specific terms as well as frequently used concepts that might lead to a conflation with diversity or religious rights, e.g. “minaret” and “christian.”

We evaluated different approaches to identify immigration-related press releases based on more than 750 randomly-selected press releases which were hand-annotated by the authors. This procedure is considered to be the gold standard for our evaluation. The goal was identifying as many relevant press releases as possible without falsely including press releases on other topics. Our dictionary outperforms those used in previous research (Rooduijn and Pauwels, Reference Rooduijn and Pauwels2011; Ruedin and Morales, Reference Ruedin and Morales2017) and performs on par with a support vector machine classifier (see Tables A1–A3, online Appendix). Given the computational efficiency and clearer decision-rules of the dictionary solution, we opt for our small dictionary rather than the SVM classifier. Overall, this offers the best compromise in terms of accuracy, interpretability, and computational efficiency. Table 1 presents the results of this classification.

2.2.2 Measuring party positions with wordscores

In a second step, we use these immigration-related press releases to scale parties’ positions with Wordscores (Laver et al., Reference Laver, Benoit and Garry2003), a scaling technique that estimates political positions based on the similarity of word usage between a set of texts with known and unknown policy positions. Our pre-processing strategy follows standard recommendations (Lowe, Reference Lowe2008; Ruedin, Reference Ruedin2013): we remove frequently used words that lack substantive meaning, stem the words, and remove words occurring less than four times. We have tested several pre-processing steps, such as removing names or relying exclusively on nouns, based on a parts-of-speech tagging pipeline. As results were not substantively different, we used the full texts.

Slightly deviating from previous applications, we calculated wordscores only based on substantively meaningful words. For this, we compare immigration-related and other texts to calculate keyness-statistics for each word. For estimating the wordscores model, we only keep words with a $\chi ^2$![]() higher than zero. While this does not lead to systematically different results, it allows us to calculate party positions based on words that are substantively meaningful regarding immigration making human validation of our measures more credible.

higher than zero. While this does not lead to systematically different results, it allows us to calculate party positions based on words that are substantively meaningful regarding immigration making human validation of our measures more credible.

As input for our Wordscore model, we use data on party positions in national election campaigns (Hutter and Gessler, Reference Hutter, Gessler, Swen and Hanspeter2019; Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Hutter, Altiparmakis, Borbáth, Bornschier, Bremer, Dolezal, Frey, Gessler, Helbling, Höglinger, Lachat, Lorenzini, Malet, Vidal and Wüest2020). These data are particularly suitable since it covers party positions at a specific moment in time, rather than expert surveys where scores may be influenced by past positions of a party. We only include parties with more than 100 immigration-related press releases (see Table 1). As Wordscores are systematically biased if the word distribution across the different reference texts is insufficient, we assign our reference scores to the press releases of the entire election month, which is roughly the same period for which the reference scores are valid.

2.2.3 Modeling strategy

We use our measures (namely, monthly party-specific salience measures as the share of immigration-related press and estimates of positions based on wordscores) for descriptive and regression analyses. This section discusses our modeling strategy as well as control variables.

We employ Arellano-Bond models (Arellano and Bond, Reference Arellano and Bond1991), a dynamic panel model estimator which allows for including lagged DVs and thus accounts for autoregression. Arellano-Bond models use a Generalized Method of Moments which includes deeper lags of the DV as instruments for endogenous lags of the DV. The model assumes a serial correlation structure: while the first-order lag of the DV is serially correlated to the DV, there must not be second-order serial correlation, i.e. the second lag may not be correlated with the DV. We test the model assumptions for our measures of salience and position, i.e. the two DVs in our models, using the Arellano-Bond test for serial autocorrelation (see Table A4, online Appendix).

Since our regression models aim at assessing the impact of the refugee crisis and radical right parties on other parties’ salience and positions, we exclude radical right parties. In total, our sample consists of 209 party-months for Austria, 299 party-months for Germany, and 138 party-months for Switzerland. For both DVs, we could not reject H0 of no correlation for the first-order lags, while we could reject it for the second-order correlations. Hence, the model assumptions are satisfied.

We use our concurrent measures of radical right parties’ immigration salience and positions as main in DVs but also include the first lag of each of these measures in order to assess whether parties’ response occurs with a delay. We control for radical right parties’ electoral pressure and a country's exposure to the refugee crisis. As discussed, previous literature has often assumed the radical right's strength affects mainstream parties’ motivation to address immigration. Thus, we include radical right parties’ strength by using monthly polls of the FPÖ, AfD, and SVP.Footnote 5

We include several measures to capture the crisis: For severity, we use the monthly number of asylum applications as research assumes that refugee arrival and the state's capacity to react determines the problematization of immigration in public discourse. Alternatively, we also consider that what mattered could be the perception of a crisis rather than the extent of refugee arrivals. Given the scarcity of opinion data over time, we rely on Google Search Trends to measure public attention to immigration. Specifically, we use the Google Knowledge Graph technology to track the frequency of a search query topic rather than individual search strings (Siliverstovs and Wochner, Reference Siliverstovs and Wochner2018). In line with advice from previous applications (Granka, Reference Granka2013; Mellon, Reference Mellon2013; Chykina and Crabtree, Reference Chykina and Crabtree2018), we compare different search trends with Eurobarometer results for immigration salience as the most important problem in a country and select the Google trend for “refugee” as closest correlate to the Eurobarometer in Germany and Austria. To delimit the crisis period, we additionally calculate a binary measure based on this series. We determine as refugee crisis the period in which the searches for the refugee topic are above the country average. Thereby, we place the start of the crisis in July 2015 in Austria, and in August 2015 in Germany and Switzerland. This period of heightened attention ends in July 2016 in Austria, in November 2016 in Germany, and in February 2017 in Switzerland, the first month in which attention to the topic falls below the mean.Footnote 6

3. Results

3.1 The rising salience of immigration

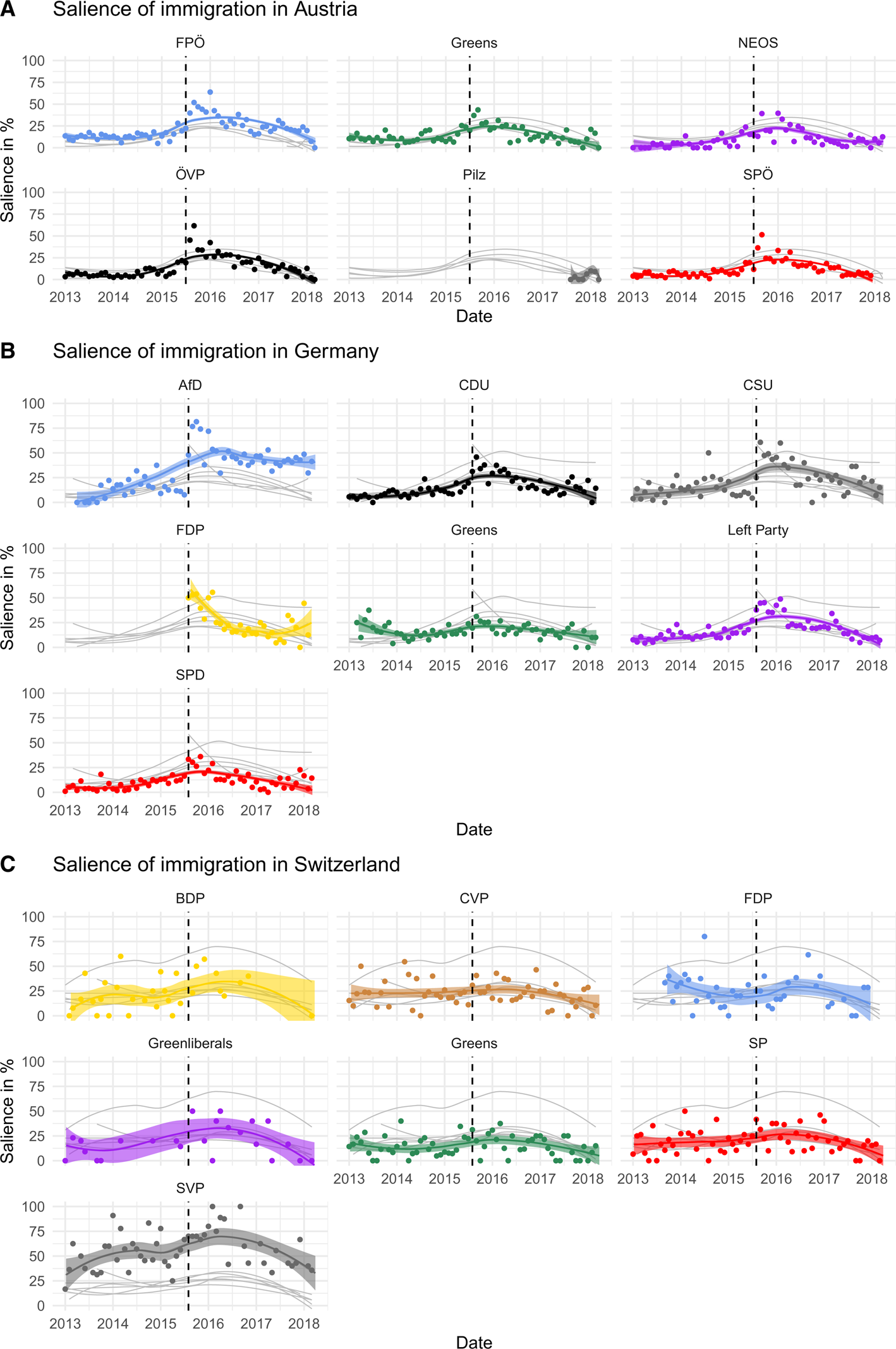

We first address how much the salience of immigration has in fact risen during our period of observation. We start by presenting our measures of salience for each party in the three countries. Figure 4 visualizes our results in two ways: The points represent monthly averages of salience while the curves represent the trend using locally smoothed daily estimates. The gray lines in the background show the smoothed lines for the other national parties and the dashed vertical line the start of the refugee crisis.

Figure 4. Estimated salience of immigration in three countries.

The first set of plots in Figure 4 shows the salience in Austria. Clearly, all parties react to the crisis with increasing attention to immigration. This increase is most pronounced for the right-wing FPÖ, which already addressed the issue most before the crisis. In line with our expectations, ÖVP becomes the party with the second highest salience of immigration during the crisis, while previously the Greens primarily competed with the FPÖ on the issue. Nevertheless, the increase is relatively similar for all Austrian parties, except for a short period of divergence at the start of the crisis visible only in the point estimates.

In Germany, depicted in the second set of plots in Figure 4, the initial increase is steeper for several parties compared to Austria. Notably, differences between the parties are more pronounced: The right-wing AfD clearly stands out for its strong emphasis on immigration, especially compared to the Greens and Social Democrats that maintain a limited salience. We also find an interesting contrast between the strong increase of salience for the Bavarian CSU which differs from its federal-level sister party CDU. Generally, the sudden impact of the crisis in August is more apparent in Germany, as even AfD's emphasis on the issue was rather low in the months before the crisis. This is primarily visible in the distribution of monthly averages.

The third set of plots in Figure 4 shows the estimated salience in Switzerland. The baseline level of immigration salience is higher compared to most parties in the other countries. Overall, we only see a slight increase during the refugee crisis, and a slow decrease from mid-2016 onward. The SVP clearly stands out regarding its attention toward this issue. However, this is not a product of the crisis as the SVP emphasized immigration already beforehand, including a previous peak in early 2014 related to a popular initiative against so-called “mass immigration.” A second period of increased emphasis for the SVP includes the period of the refugee crisis and continues throughout the 2015 Swiss elections, which gave the SVP an ideal opportunity to campaign on immigration.

Generalizing to the party system-level, the salience of immigration increased in all three countries. The difference between the radical right and its mainstream competitors is most notable in Switzerland where, comparing the general level of immigration salience, we also find a more steady attention to the issue. We suspect this difference is due to Switzerland's internal political dynamic with the importance of popular votes as well as the relevance of immigration beyond forced migration, e.g. in the context of migration from the EU.

While the general increase in salience is certainly interesting, it is also important that the salience did not only increase drastically, but it also faded almost entirely after the crisis for most mainstream parties. This suggests that parties might have changed their strategy and tried to de-emphasize immigration once the immediate problem pressure decreased. Competing findings based on media reports, e.g. during election campaigns (Grande et al., Reference Grande, Schwarzbözl and Fatke2019; Hutter and Gessler, Reference Hutter, Gessler, Swen and Hanspeter2019), suggest that the media might still have reported parties’ immigration-related statements disproportionately, even though parties had started to avoid the issue.

3.2 Dynamics of salience

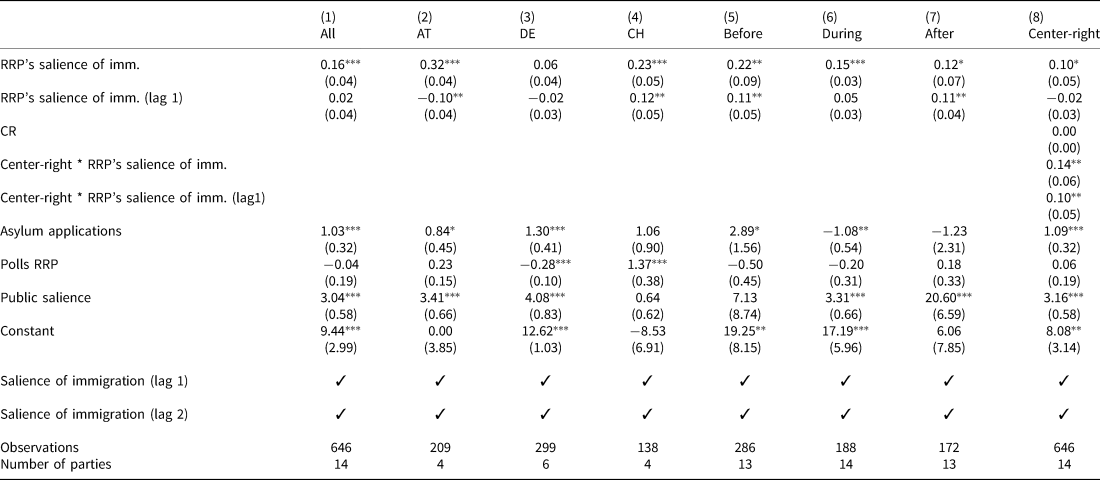

We now proceed to explicitly test our salience hypotheses in a regression framework. Table 2 presents eight models, first including all mainstream parties in our sample, then splitting the sample by country, time period, and finally including an interaction term for center-right parties. All models include the monthly number of asylum applications, public salience of immigration, and radical right parties’ polls as control variables.

Table 2. Regression results for mainstream parties’ salience of immigration

Robust standard errors in parentheses.

$^{\ast \ast \ast }{\rm p}< 0.01$![]() , $^{\ast \ast }{\rm p}< 0.05$

, $^{\ast \ast }{\rm p}< 0.05$![]() , $^{\ast }{\rm p}< 0.1$

, $^{\ast }{\rm p}< 0.1$![]() .

.

Our main independent variable of interest—radical right parties’ concurrent immigration attention—is highly positively associated with increasing mainstream party attention toward the issue. This lends support to our hypothesis 2a as the direction of the effect is consistent across all models and, except for model 3 (Germany), statistically significant. Generally, radical right parties’ salience contagion on mainstream parties remains positive and significant throughout the three time periods (models 5–7). The effect sizes vary across the models. In Austria, each 1 percent increase in radical right parties’ salience accounts for an average increase of 0.32 percent for other parties, while the effect size is only 0.12 percent for all parties after the crisis. These findings indicate that radical right parties can pressure mainstream parties to increase their immigration salience. We note, however, that this effect is strongest in the period before the crisis: While the impact of contagion may be bigger during the crisis period, given the higher salience of the immigration issue, the radical right actually held most agenda setting power before the crisis. The first-order lag of RRPs’ salience is only significant and positive in Switzerland, as well as for the combined model in the period before and after the crisis, which points toward a more immediate effect of RRPs’ immigration politicization during the refugee crisis.

We test our expectation Hypothesis 3a that center-right parties react more strongly to radical right parties’ increased issue emphasis by including an interaction term in model 8. While the zero-finding of the center-right dummy shows that these parties do not generally dedicate more attention to immigration than other parties, the coefficient of the interaction term—positive and highly significant—suggests that center-right parties react more strongly to the behavior of radical right partiesFootnote 7 —both in terms of the concurrent and the first order lag of the radical right immigration salience. We find mixed results for our control variables, i.e. the monthly number of asylum applications, the public salience of immigration, and radical right parties’ polls.

Overall, despite the stronger effect size before the crisis, we think the findings match our theoretical expectations and the descriptive results. The regression analyses show—even controlling an upward trend during the refugee crisis—that radical right parties’ emphasis on immigration is positively related to mainstream parties’ salience. In the next section, we move to parties’ positions on immigration and assess their change during the refugee crisis.

3.3 Party positions on immigration over time

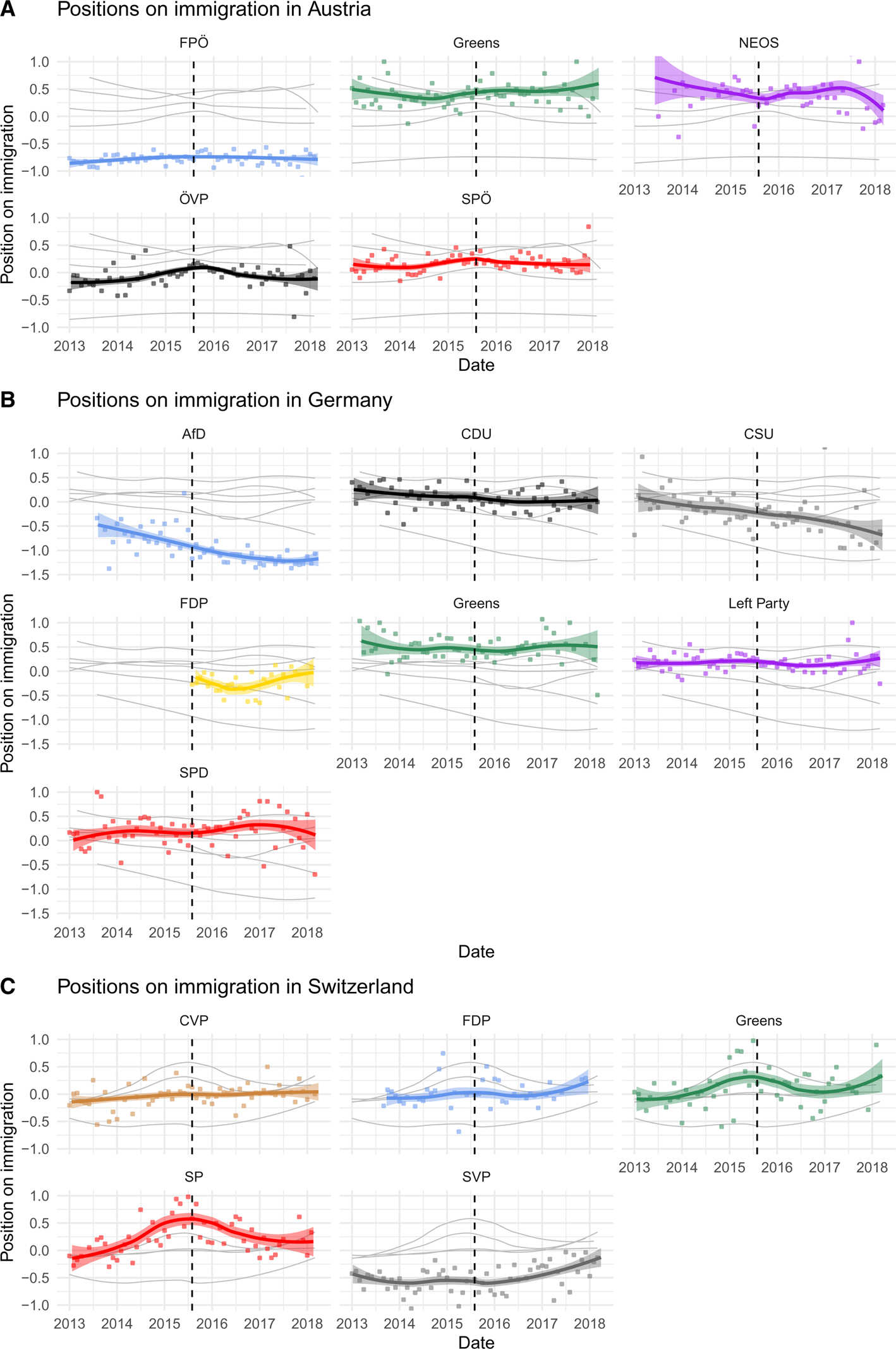

As parties have incentives to avoid increasing political conflict around immigration, we expect party positions to be more stable than the salience of the issue. We present the development of party positions in Figure 5 before we analyze their determinants with regression analyses. The first set of plots in Figure 5 shows the development of party positions in Austria. Most parties’ positions are rather stable. Notably, we see a small shift in the positions of ÖVP and the Greens during the refugee crisis. SPÖ's and FPÖ's positions are rather stable, while our estimates for NEOS during 2017 are inconsistent. Overall, we do not see similar changes as observable for salience.

Figure 5. Estimated party positions on immigration in 3 countries.

The second set of plots in Figure 5 depicts the position estimates for Germany. Compared to Austria, shifts are more pronounced. Most notably, AfD increasingly radicalizes its anti-immigration stance. This finding is in line with previous research on the party (Arzheimer and Berning, Reference Arzheimer and Berning2019). Additionally, CSU progressively takes an anti-immigration position, more and more diverging from its sister-party CDU. This mirrors a growing and heated conflict during the refugee crisis: Horst Seehofer, the by-then CSU party leader, and his sharp criticism of Chancellor Merkel filled the headlines for weeks. The Greens’ pro-immigration stance only shows small changes that do not seem to be systematically related to the refugee crisis. The positions of CDU, SPD, and the Left are very stable throughout the whole period, although individual estimates for SPD deviate considerably.

Our results for Switzerland in the third set of plots in Figure 5 show the clearest position shifts of mainstream parties. While CVP and FDP remain stable, the Greens and the Social democrats alter their position notably to a more positive stance for a prolonged period. This development begins in early 2014 and might hence be related to the popular votes on immigration taking place in February and November 2014. Interestingly, this trend continues until fall 2015, the beginning of the refugee crisis. Since then, the Greens and the Social democrats again turned more negative regarding immigration. Unsurprisingly, SVP holds the most anti-immigration stance. While the smoothed line is relatively stable until early 2016, more extreme monthly scores are present throughout the period. From mid-2016 onward, SVP moderates its position, moving toward the other parties’ position. This temporally coincides with a decline of SVP's emphasis on immigration as shown in Figure 4 and may show a re-orientation of the party: After a long period of mobilization against immigration using popular votes, the defeat of its “Durchsetzungsinitiative” marked a turning point for SVP.

Overall, radical right parties exhibit by far the most critical stances on immigration. While some mainstream parties like CSU adjust their position, most do not. Moreover, some parties like ÖVP take more positive stances on immigration during the refugee crisis. In the following section, we shed light on the factors that drive mainstream parties’ positions on immigration using regression analyses.

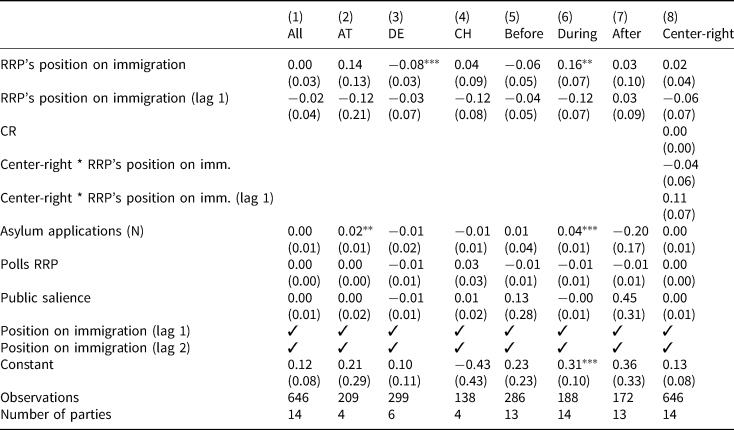

3.4 Dynamics of positional change

Following the same research design as for salience, we carry out regression analyses for party positions using Arellano-Bond estimators. We again present models with split-samples and use the same control variables. Considering the three different options for mainstream parties presented in our theoretical model, i.e. sticking to positions, being adversarial, or accommodating the radical right, we find mostly null results in line with our expectations in Hypothesis 2b. The only exceptions are German parties which take more positive positions when radical right parties become more critical, as the negative and significant coefficient in model 3 suggests. Additionally, we find a positive association of radical right parties’ concurrent position with mainstream parties’ immigration stances during the crisis. This differs from our expectation set out in Hypothesis 2b, although the negative (but not significant) lagged effect suggests such shifts may not be permanent.

Concerning center-right parties, we cannot confirm our hypothesis that these parties will adjust their positions following radical right parties (Hypothesis 3b). The coefficient of the interaction term in model 8 presents a null finding of no such effect. Note, however, that this differs by country (see Table 3): we can confirm the expectation of a (statistically significant) effect for Switzerland both regarding the concurrent and the lagged effect. In contrast, the concurrent effect is negative for Austria and Germany but positive for the lagged effect. For Austria, this finding is statistically significant. Overall, these findings for center-right parties indicate slower responses in terms of positions, which cannot be adjusted as easily as salience and are more dependent on party-internal consultations.

Table 3. Regression results for mainstream parties’ positions on immigration

Robust standard errors in parentheses.

$^{\ast \ast \ast }{\rm p}< 0.01$![]() , $^{\ast \ast }{\rm p}< 0.05$

, $^{\ast \ast }{\rm p}< 0.05$![]() , $^{\ast }{\rm p}< 0.1$

, $^{\ast }{\rm p}< 0.1$![]() .

.

Beyond the lack of a significant effect in almost all models, we want to highlight the small effect sizes in most specifications, as party positions are overall rather stable. Additionally, all control variables have no effect. Only the monthly asylum applications show a small positive effect on mainstream parties’ positions for the crisis-period in models 2 and 6.

4. Conclusion

In this paper, we studied how crises shape party competition, specifically short-term responsiveness to challengers. We did so based on the impact of radical right parties on mainstream parties’ emphasis and positions on immigration in the context of the refugee crisis in Austria, Germany, and Switzerland. We proposed that—next to the direct effect of the crisis—mainstream parties’ reactions are based on a two-step decision model that we derived from Meguid's seminal framework for mainstream party strategies. Our results show that parties were forced to increase their immigration emphasis but mostly maintained their previous positions. That is, mainstream parties’ attention to immigration was not only affected by the crisis itself but also driven by radical right parties’ emphasis on the topic.

By drawing attention to short-term dynamics, our approach departs from much of the existing research. We believe these dynamics are complementary to the long-term changes which have been the primary focus of existing scholarship. Our findings suggest that a high-paced short-term contagion for salience exists and primarily occurs within the same month. This implies that beyond the long-term strategies outlined in party manifestos, parties also react to their competitors within days or weeks in their press releases. This supports similar research on short-term agenda setting on social media (Gilardi et al., Reference Gilardi, Gessler, Kubli and Müller2021). Notably, our results hold for all three time periods, i.e. also before and after the crisis when we can assume that there are fewer migration-related events that might confound our analyses.Footnote 8

In contrast, with regard to positions, our findings point to a diminished responsiveness toward the radical right. Namely, most parties’ positions on immigration are rather stable and we find little evidence that parties took more negative stances during the refugee crisis (with the important exceptions of FDP and CSU). In a regression framework, the radical right's impact on parties is rather limited and we only find evidence for such an effect during the immediate crisis period and in Germany—where most parties have seemingly taken a more adversarial stance toward the radical right. A key reason for this limited reaction may be that positional change occurs at a slower pace which we miss with our model specification. As our study constitutes the first empirical analysis of these immediate dynamics for positions, it complements previous research that mostly studied contagion from one election to the next but cannot provide definite answers. This holds especially as our results depend on the cases we study. We suspect the adversarial reaction in Germany may be due to the specifics of the case: Unlike the well-established radical right parties in Austria and Switzerland, the AfD constituted a new challenger and hence sparked a different reaction. This may be a result of coalition considerations. As the AfD was considered a pariah party, none of its competitors considered the option of a coalition in the near future (Bräuninger et al., Reference Bräuninger, Debus, Müller and Stecker2019). This allowed parties to be less responsive both in terms of salience, where contagion effects are not significant for Germany, and in terms of positions, where parties may have found it easier to confront the AfD.Footnote 9

While we do find short-term contagion in terms of salience, our findings also speak to limitations regarding the broader effect of crises: After a short period, most parties’ attention to immigration peters out, despite the leap in salience at the beginning of the crisis. This decline provides important context for the interpretation of any changes found in research focused on changes from one election to the next. Moreover, we find that the crisis affects the level of attention to immigration but does not alter the logic of party competition: Salience contagion is already in place before the refugee crisis and continues to exist in the post-crisis period. Nevertheless, the higher baseline salience of immigration during the crisis makes this contagion all the more powerful in terms of its substantive effect.

Regardless of the time interval researchers choose to analyze, an important take-away from our findings is the importance of expanding Meguid's model by assessing changes in salience and positions separately. It seems that both the presence and pace of mainstream parties’ responses may be different for salience and positions. This might be explained by a higher degree of flexibility in terms of salience, compared to positions. Empirically, our research suggests that the refugee crisis provided momentum for radical right parties, as they consistently managed to exert pressure on other parties, even in a situation of high immigration salience. However, this did not apply to positions to the same extent. As the effect for salience plays out quite similarly in all three countries, we conclude that—despite the differences between our cases—radical right parties (and potentially challengers more broadly) play a functionally equivalent role during crises in different contexts. When they are provided with a favorable political opportunity structure, they will increase attention to their agenda and seem to move their competitors to do so, too.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2021.64.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Anja Neundorf and the anonymous reviewers for their comments and guidance. We are greatful to Tarik Abou-Chadi, Raffaele Grotti, Elisabeth Ivarsflaten, Heike Klüver, Hanspeter Kriesi, Giorgio Malet, Stefan Müller and Gijs Schumacher for their help and feedback on previous versions of this paper. Additionally, our paper was greatly improved by feedback from participants and discussants at ECPR, EPSA, MPSA and SISP as well as a workshop on parties in the electoral cycle organized by Alexandra Feddersen and Thomas Meyer and a seminar at the University of Zurich.