Introduction

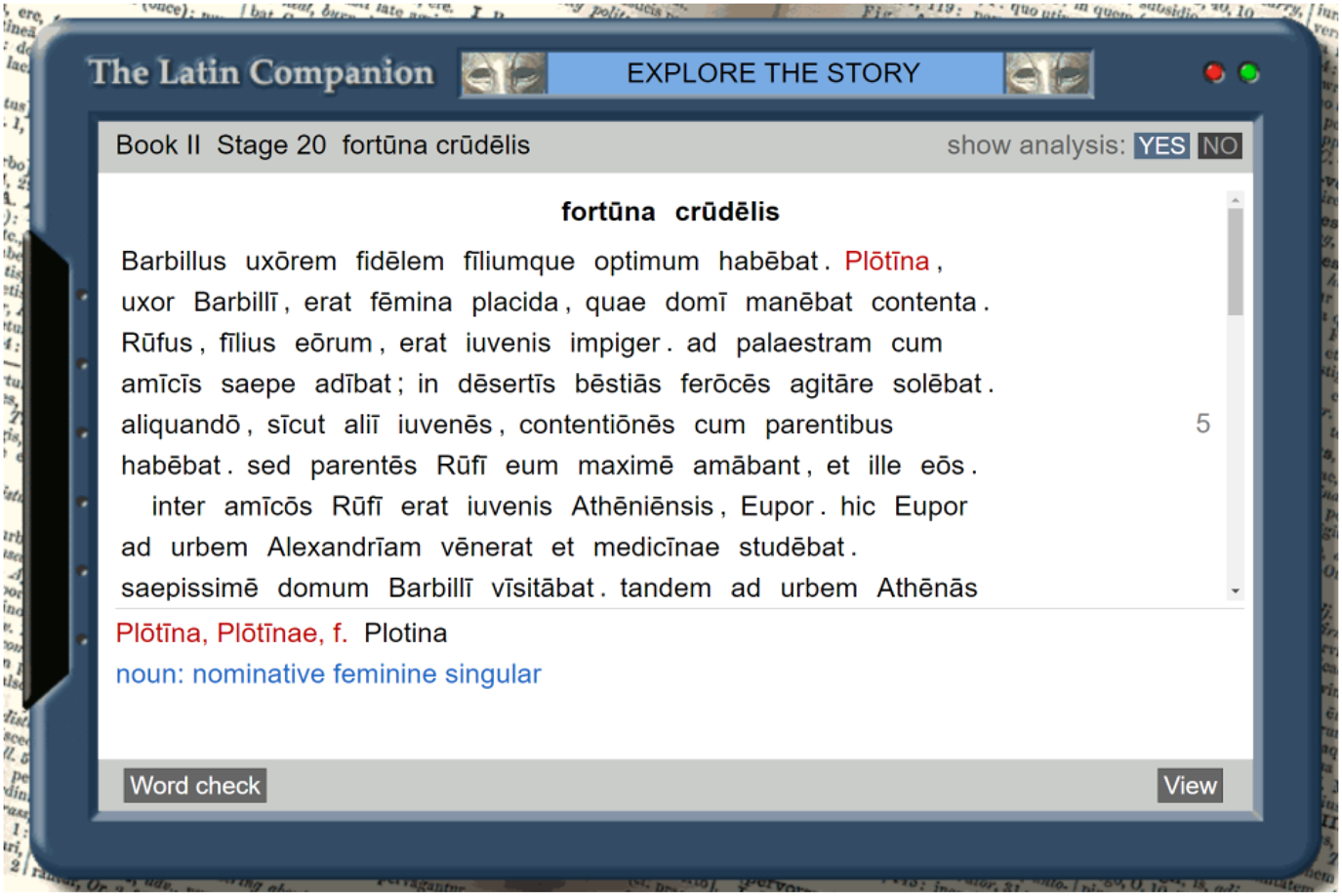

From the beginning of my school placement in January, I observed many lessons with two different Year 8 (age 12) Latin classes in which the pupils confidently used the online Cambridge Latin Course ‘explore the story’ (which will hereafter be referred to as the ‘Explorer Tool’) on iPads. Each table grouping had an assigned iPad so that the class teacher could monitor what the group of pupils was viewing, direct them to the correct webpages and lock the iPads if necessary. In my first Professional Placement, I had seen the Explorer Tool used by a class teacher and projected onto a whiteboard while going through a passage with the class. I was also aware that pupils were using the Explorer Tool when translating or completing comprehensions for homework. My second school placement was, however, my first experience of seeing pupils using the tool. The pupils are able to click on each word and are quickly provided with ‘its dictionary definition as given at the back of the textbook’ (Lister, Reference Lister2007, 112). I was able to witness the speed at which pupils were able to access this information about each word and could see how this was faster than having to look up each word in the back of their textbook. The tool can also provide more information than the physical textbook, in that for Book II onwards the analysis can be turned on as shown in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1. The ‘explore the story’ feature for the story fortuna crudelis, Stage 20, p. 136 (Cambridge School Classics Project, 2000). Taken from the CSCP website: www.cambridgescp.com.

From my observations, my concern was that the pupils were not using the tool to its fullest potential. They appeared to be using it in its role as a dictionary, in that they were using the tool to find out the meaning of the word, but I saw little evidence that they were considering either the morphology or the additional analysis provided by the tool. I was worried that they were simply clicking each word to find out its meaning and then creating a translation with these words that they thought made sense, rather than checking the word's function within the sentence to produce a translation. The Explorer Tool was intended to aid the development of ‘reading fluency’ by allowing them to ‘read much greater quantities of Latin than had previous been the case’ (Hunt, Reference Hunt2016, 103). The Cambridge Dictionary defines fluency as the ‘ability to speak or write a language easily, well, and quickly’ (Cambridge Dictionary, n.d.). I witnessed how the Explorer Tool aided the pupils in reading Latin quickly because they can check the meanings of words faster than using a dictionary or the physical textbook. However, the accuracy of their translations was not as clear.

During my observation of both Year 8 classes, the pupils were using iPads in small groups. These groups were dictated by where the pupils were sitting and the number of iPads by how many were needed for every pupil to be able to see and interact with one. In anticipation of teaching the classes, I noticed that I was also focusing on the relationships between the pupils within these groups. The majority of the groups, and the individuals within them, appeared to have become accustomed to using the iPads during these group translation or comprehension sections of their Latin lessons. I was able to see the different personalities of individuals and the role they took within their group, as well as the different ways in which the groups were approaching having one iPad between four or five of them. There was a range of iPad usage by the individuals within groups, from a pupil who appeared to check the meanings of the words for the group to a group in which the pupils appeared to be working with very little collaboration and using the iPad for its speed.

Context setting

My research took place in a state-maintained selective secondary school with just over 1000 pupils on roll in Greater London. The school is boys' only between Years 7 and 11 (ages 11–16), with a mixed sixth form (ages 17–18). The number of pupils at the school with English as an additional language is higher than the national average (Ofsted, 2014), with the number of Pupil Premium pupils and pupils with Special Educational Needs being significantly below the national average. The school receives over 1,400 applications for the 128 places available in Year 7. Latin is compulsory in Year 7 and pupils follow Book I of the Cambridge Latin Course (hereafter referred to as ‘the CLC’) (Cambridge School Classics Project, 2000). All four classes tend to complete Book I of the CLC by Easter. Pupils continue with the CLC, moving on to Book II in the Summer term of Year 7 and continuing to use it into Year 8. Latin is chosen as an option alongside Modern Foreign Languages in Year 8 and pupils work through Book II and begin Book III. Pupils then go on to choose their GCSE options,Footnote 1 of which Latin is one, as they enter Year 9 (age 13).

The number of pupils with English as an Additional Language in the Year 8 Latin class that I chose as my case study is lower than the school average, but closer to the national average. There is one pupil receiving Pupil Premium funding in the class of 17.Footnote 2 None of the pupils had been identified as having Special Educational Needs. The iPads used in class are part of a bank of iPads belonging to the Humanities department. This means that the iPads have to be booked in advance and that for most lessons iPads are used in pairs or groups and not individually. I chose this Year 8 class because they are of mixed ability and they have experience with using the iPads and they are familiar with the Cambridge Latin Course.

Literature review

Classics teaching and information and communication technology (ICT)

One of the aims of my research was to investigate how effectively pupils are using ICT in the classroom and so I was interested to discover the advantages or difficulties found by others. The development of technology has resulted in its increased use in society and subsequently in the classroom. The devices that pupils use at home and outside of the classroom can now be brought into it. Reinhard (Reference Reinhard2012) believes that it has got to the point where the question about technological use is now when to use it and not whether to use it or not. Hardwick (Reference Hardwick2000) warns that serious consideration of the role of ICT in teaching and research is required for it to be fully integrated into both fields. In both areas, how it is used needs to be clear to both the planner and participants. Hardwick also argues that the use of ICT needs to be worthwhile and justifiable, that the ‘mere production on screen of what may already be perfectly easily accesses and used in print does not justify massive investment of time and resource’ (Hardwick, Reference Hardwick2000, 293). However, I do believe that there is a benefit to being able to display a copy of a physical textbook via projector or other means. The focus of all the pupils is then in the same place. They are all looking at the board and the teacher simultaneously, as opposed to looking down at their textbooks. Moreover, Hardwick believes that there is an obligation to ensure that those who would benefit from the technology being used have ‘the equipment and training to enable this’ (Hardwick, Reference Hardwick2000, 294). How effectively the pupils are using the Explorer Tool is a reflection of their understanding of how to use the tool and their choices about which information they read or use within their group.

Whilst planning a lesson that is going to involve ICT, teachers must consider that it takes time to acquire such skills and they must also consider how the use of the technology is going to affect the pupils. When planning my research, I took for granted that the pupils were already accustomed to using both the iPads and Explorer Tool and so assumed that my research would have a minimal effect on the pupils. Reinhard (Reference Reinhard2012) proposes using ICT as a reward for productive work and good behaviour and in a capacity that allows pupils to be creative. ICT can also be used as a learning tool throughout lessons and can allow pupils to work independently of the teacher, individually, in pairs or small groups. Gibson believes that this ‘discovery approach’ (Gibson, Reference Gibson2001, 42) puts the onus on the pupils. In addition, working with their peers encourages pupils to consider the provided information carefully and engage in ‘critical thinking, problem solving, discussion and communication’ (Gibson, Reference Gibson2001, 42). My aim was that allowing the pupils to work in small groups would facilitate the development of such skills. Regardless of how the ICT is used, Gibson (Reference Gibson2001) suggest that most teachers' aim would be that, over time, pupils are both excited to use the technology but also comfortable when using it. There is a fine balance between the novelty of ICT's use and pupils' ability to use it effectively. I had planned my research lessons to attempt to gain this balance of ICT use, so that it was regular enough for pupils to become accustomed to the Explorer Tool but not rely on it. I hoped that this would encourage group discussion and improved accuracy of translation.

The CLC and ICT

With this research focusing on the Explorer Tool, I felt it was important to establish its origins and intended function, considering the development of technology in recent years. The Cambridge Latin Course has an abundance of online resources that are easily accessible via the University of Cambridge School Classics Project website. There are online versions of the textbooks, activities and supplementary information about the cultural background material. Each story has an ‘Explore the story’ feature, which I will refer to as the Explorer Tool. This was developed from a ‘morphological analyser’ (Lister, Reference Lister2007, 109), which was initially designed to aid Classics undergraduates at the University of Cambridge ‘who were struggling to read and comprehend course texts in their first year of study’ (Hunt, Reference Hunt2016, 103). A small-scale study of these pupils found that they ‘spent approximately 70 per cent of their time when working on texts looking up words in the dictionary or grammar book and only 30 per cent reading the Latin’ (Lister, Reference Lister2007, 108). When the CLC was being revised for its fourth edition, the team working on this revision realised that this tool could be ‘a very powerful, time-saving tool’ for them (Lister, Reference Lister2007, 108). The team wanted to ‘shorten the stories to enable pupils to work through the course more quickly’ (Lister, Reference Lister2007, 109) and so needed to track the words they were removing. This was because the removal of individual words could affect the glossary of words for stories and the vocabulary lists throughout the book (Lister, Reference Lister2007). The tool's focus on aiding reading speed by providing vocabulary continues when it is developed into the Explorer Tool which pupils can use at home or in the classroom, individually, in pairs, in groups or in teacher-led whole class sessions. The Explorer Tool's ability to provide definitions of words so quickly aids pupils' efficiency when they are translating and so feeds into my interest in whether pupils are using the tool effectively. Additionally, the Explorer Tool and the other online features of the CLC work on all platforms, including smartphones. The Explorer Tool is a ‘quick-click’ feature which gives the CLC dictionary's definition of the word when it is clicked on (Lister, Reference Lister2007, 112). Lister clearly defines how the Explorer Tool aids pupils in that ‘what might have taken the learner 15–20 seconds to find in the textbook appears instantly on the computer screen’ (Lister, Reference Lister2007, 112). The advantage of this speed is in helping pupils to read and translate the Latin stories faster and so ‘develop reading fluency by providing them with the opportunity to read much greater quantities of Latin than had previous been the case’ (Hunt, Reference Hunt2016, 103). The increased speed of checking vocabulary also maintains pupils' interest and impetus when they are translating (Lister, Reference Lister2007). This interest in the work encourages detailed group discussion, enabling pupils to work together and improve on their answers. However, it does not necessarily encourage pupils to use the additional information provided about each word and so could affect their accuracy.

Research has previously been conducted about the use of the Explorer Tool in the classroom and was helpful in forming my research questions. Francis Hunt's Reference Hunt2018 case study of a Year 9 class using tablets allowed pupils to have their own tablet and use it periodically as they chose throughout the lesson (Hunt, Reference Hunt2018, 42). They were using Book II of the CLC and without the Explorer Tool were taking around two minutes to translate a line (Hunt, Reference Hunt2018) which can range between five and ten words. Francis Hunt's findings suggested that the tool was aiding the speed of pupils' translations because almost all the pupils read ‘over twice the amount’ of Latin with the Explorer Tool. However, he found evidence that this increased speed of translation was leading to a loss in accuracy and affecting pupils' understanding (Hunt, Reference Hunt2018, 46). Pupils seemed to be aware of this lack of understanding and Francis Hunt suggests that they were fitting the words together like a jigsaw. He also discovered evidence that would demonstrate that when using the Explorer Tool pupils consider the grammar less. The results of the survey conducted showed that pupils ‘generally believe that the Explorer Tool achieves its goal of increasing speed and aiding understanding’ (Hunt, Reference Hunt2018, 48), though one pupil admitted to clicking on every single word, simply because they could, regardless of whether they would have been able to recall the meaning. Such an admission means that not only do pupils need to be able to use the technology (Hardwick, Reference Hardwick2000), but that they also need to be taught how to use the technology appropriately. The Explorer Tool does allow pupils ‘to check the meaning and morphology of individual words without losing the momentum of the reading’ (Hunt, Reference Hunt and Lister2008, 110), but this is not necessarily what pupils are doing in practice. Pupils are given the advantage of being provided with this information but even then, are not necessarily using it or possibly not understanding it. Francis Hunt's study highlighted many of the issues I would need to be aware of and take into account throughout my own research.

ICT can be used in many capacities in the Latin classroom and depending on the teacher choice and/or availability of devices pupils do not necessarily have their own device and so must communicate with their peers. The choice to use one iPad for each small group within my study created such a situation and so allowed me to consider how pupils use talking in lessons. This group work allows for collaboration and discussion amongst pupils. Lindzey (Reference Lindzey2003) states that this discussion or ‘pupil talk’ can involve the reading aloud of Latin words and reinforces how important it is for pupils to learn noun endings. Lindzey follows this up by elaborating that reading of Latin can also be aided by ‘metaphrasing’ (Lindzey, Reference Lindzey2003, 9). ‘Metaphrasing’ is the idea that if pupils read the Latin in the order that is appears in the sentence, then they are able to make assumptions about what to expect next. Lindzey (Reference Lindzey2003) uses Quintus servo to demonstrate that after nouns in the nominative and dative a pupil might expect a verb of ‘giving’ for example. If, when using the Explorer Tool, pupils are clicking on the words in the order in which they appear, they will also be seeing the additional information provided about the word. It is then possible that pupils are making morpho-syntactic assumptions as shown in the example, if they are using this additional information. This information and possible assumptions could be discussed by pupils as they work through a piece of Latin. Francis Hunt (Reference Hunt2018) did not want discussion or pupils' confidence to be inhibited by the introduction of technology, which I hoped would be the case in my study as pupils had previous experience of using the Explorer Tool on iPads. However, he found that ‘ICT does not necessarily promote the sort of collaboration’ he had wished it would (Hunt, Reference Hunt2018, 111). Though technology can have its advantages, it is not an all-encompassing solution. Pupils are still able to choose when, what and how to contribute. Technology can facilitate collaboration but does not guarantee it.

Because my research would involve analysing pupils' discussions, I considered what form this might take and how it would be beneficial to the pupils. Discussion amongst peers or ‘pupil talk’ can aid learning within the classroom and personal development of a skill that can be used throughout life. Language gives pupils the opportunity to express their own opinion and contribute to ‘joint thinking about a problem’ (Mercer, Reference Mercer2000, 12), though in some cases it may be language itself that needs resolution. Mercer considers language to be a crucial means by which we join the thoughts of individuals with those of others to establish ‘resources of knowledge and procedures for getting things done’ (Mercer, Reference Mercer2000, 15). Pupils are able to learn collective thinking from teachers and each other. If this is successful, it is demonstrated by ‘exploratory’ talk which involves individuals building on the thoughts of others to eventually come to a conclusion as a group (Mercer, Reference Mercer2000, 153). Mercer found that there are certain words (‘if’, ‘because’, ‘why’) that denote exploratory talk because these are words ‘words which speakers commonly use to account for their opinions’ (Mercer, Reference Mercer2000, 154). Mercer was aware that not all talk is as productive and that any talk which presents the decisions of an individual or a sense of competition can be labelled as ‘disputational’ (Mercer, Reference Mercer2000, 157). More focused on Latin, Wright's investigation of pupil discussion in pairs concluded that mixed-ability pairings can have a positive impact on Latin translations (Wright, Reference Wright2017, 21). The analysis of their discussions showed evidence of collaboration within the pairs, that the pupils were building on each other's ideas and progressing through the translation together. Wright (Reference Wright2017) also went on to analyse the language used in these discussions and found that it was not necessary for the pupils to use grammatical terminology. Pupils were able to translate accurately from Latin into English without orally clarifying which cases nouns are in or their role in the sentence. This suggests that there are processes occurring and assumptions being made by pupils that they are not expressing out loud.

I will go on to analyse how accurately the pupils in my study were translating the Latin and whether they used any grammatical terminology.

Research questions

RQ1: Are pupils using the Explorer Tool effectively in small groups?

RQ2: Do pupils translate accurately using the Explorer Tool?

RQ3: Do pupils use ‘pupil talk’ to aid the process of translation?

Teaching sequence

My first full lesson teaching the Year 8 class which would be the focus of my research was chosen as my starting point because the class had concluded Stage 19 of the CLC in the previous lesson. I did not record any of the pupils' discussions in this lesson as I was teaching them for an entire lesson for the first time and I did not want this to affect their discussions. I used this lesson to introduce myself, a new seating plan and my research to the pupils. I did however ensure that the lesson included elements that would be present in the following lessons: teacher-led class discussion, small group work, individual translation of Latin sentences. In the next lesson, three days later, I used the iPads to record pupils whilst they were translating part of a story in their groups in order to test the iPad's quality of sound recording. Having established that I would be able to place another iPad in the centre of each table to record the pupils' conversations, I decided to record their conversations in the next two lessons that I taught them. I was only able to record the first lesson before teaching moved online.

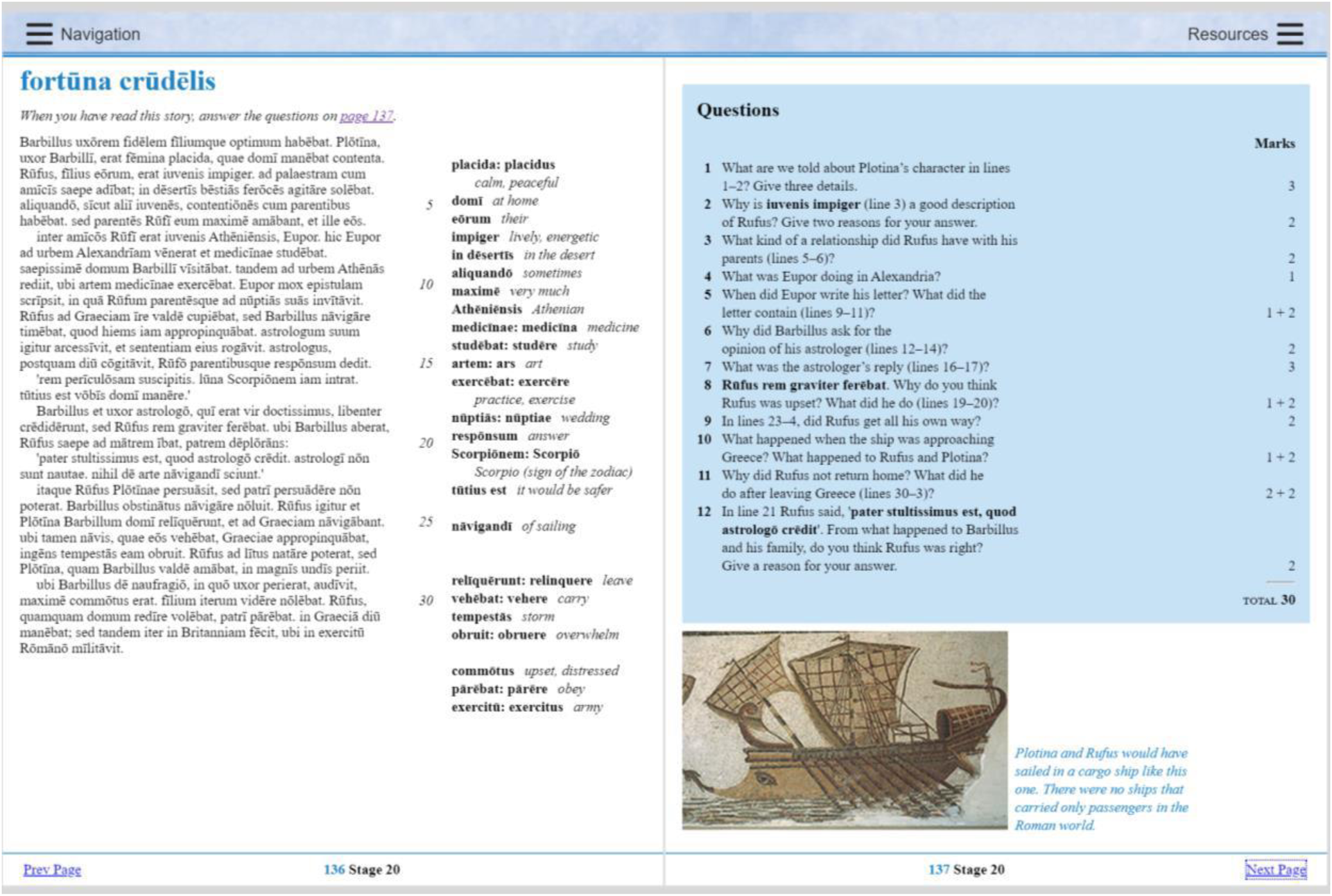

The first lessons took place two days later. The lesson began with directed questioning to revise present participles which had been covered in a previous lesson. The pupils then studied the sentences provided on p135 of the textbook (CSCP, 2000) and noticed the new form of the present participle with the accusative singular ending. This was then added to the pupils' existing note and I modelled how to translate the new form in the context of an example sentence. I then introduced the pupils to eam [her] and eum [him]. I chose to do this before the pupils encountered them in the upcoming passage. I gave them a note with the masculine and feminine forms in the accusative, dative and genitive cases, as well as the English translations of each form. The pupils were then given 15 minutes to begin the comprehension questions that accompany the story fortuna crudelis (CSCP, 2000, p. 136) (Figure 2). To finish the lesson, each group completed an iteration of online activity infinitive or participle on the iPads. The pupils also had two Latin lessons which I planned but were taught by another teacher. The second lesson that I would have recorded was planned for a few days later.

Figure 2. fortuna crudelis story and comprehension questions (CSCP website).

Methodology

I was ‘open and honest’ with the class (BERA, Reference British Educational Research Association2011, 16) when I introduced my research. I explained that I would be recording their discussions during parts of their next few Latin lessons, that they would not need to do anything out of the ordinary and that this would help me develop my teaching. I asked for their consent for their voices to be recorded, made it clear that their participation was entirely voluntary and informed them of their right to ‘withdraw from the research for any or no reason, and at any time’ (BERA, Reference British Educational Research Association2011, 18). It is difficult not to produce interpretivist research when an individual is interpreting qualitative data and so this must be taken into account when considering conclusions of qualitative case study research.

Methods

The aim of my research was to analyse how pupils talk during group translation using the Explorer Tool. Because I was interested in what they were saying during these discussions, I decided the best way to capture this was by recording their conversations. This was done using iPads as pupils were used to seeing these devices in class and the sound quality was good enough for me to differentiate between individuals in a group. Gibson poses questions about the effect of the introduction of technology into the classroom (Reference Gibson2001, 39). I intentionally chose a case study which allowed the pupils to continue using technology that they had become accustomed to on devices that they were capable of using and so did not have to consider many of the issues Gibson forewarns teachers of. As Reinhard advises, I considered the technological literacy of both myself and the pupils before commencing the study so that I could ‘find common ground and a shared comfort level’ (Reference Reinhard2012, 121). This sense of being on the same level allows technology to facilitate teaching and learning rather than hindering it (Reinhard, Reference Reinhard2012, 121).

The pupils worked in small groups and the grammatical analysis was turned on to aid their translation. The pupils completed a comprehension and though it is not a full translation, it does ‘require in detail reading to get full marks’ (Hunt, Reference Hunt2018, 46). Before analysing the pupils' discussions, I was aware that I may find talk that Mercer would categorise as ‘disputational’ (Reference Mercer2000, 157), which is talk that consists of ‘competitive activity and indiviudalized decision-making’ (Mercer, Reference Mercer2000, 157). I would like to consider the rest of the talk, that which can be considered to be ‘exploratory’ when pupils are doing the following:

engaging ‘critically but constructively with each other's ideas’

offering ‘relevant information…for joint consideration’

giving reasons and alternatives when challenging others' proposals

seeking ‘agreement … as a basis for joint progress’

(Mercer, Reference Mercer2000, 153).

Pupils may be using words such as ‘because’, ‘if’ and ‘why’ as these terms can be used by speakers to ‘account for their opinions’ (Mercer, Reference Mercer2000, 154).

Data and findings

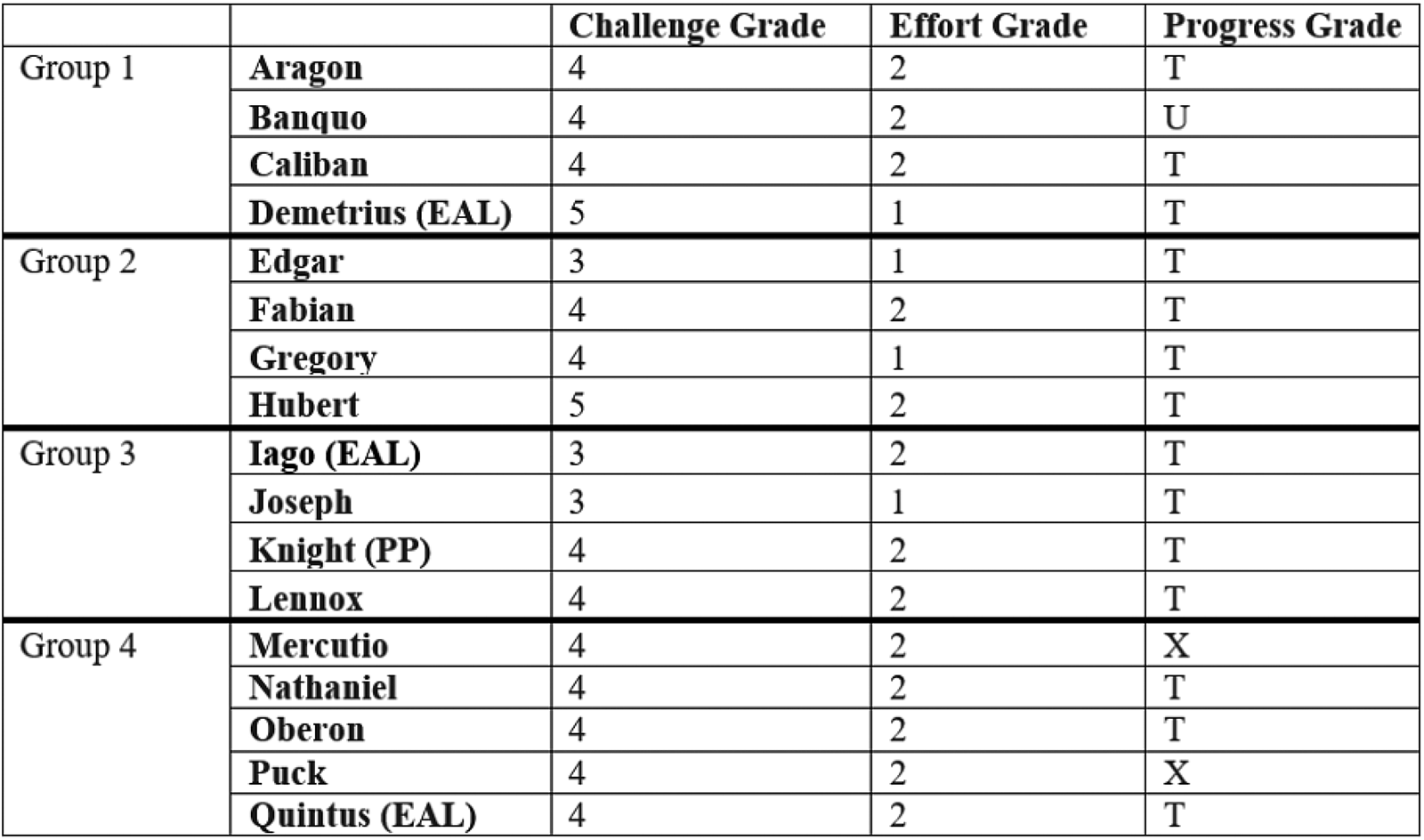

In order to record all pupils' contributions to the discussion, the pupils' seating arrangements were changed prior to the recording. In order to minimise the effect of this change in dynamic, I had intended to record the pupils across multiple lessons over a period of weeks to give them a chance to settle into new groupings. This longer time period would also have given the pupils time to become accustomed to being taught by myself. With a total of 17 pupils in the class, they were split into four groups, three groups of four and one group of five. I looked at three pieces of information about the pupils' academic record. The first of these is their challenge grade. This is the first step in predicting grades for GCSE and all the challenge grades in the class are 3, 4 or 5. The other two pieces of data are taken from their most recent year-wide Latin test. They indicate the effort the pupils are considered to have put into the assessment and if they are making the expected level of progress. The table below contains this information for each pupil. The groups the pupils were seated in is shown as well as their status with regards to EAL (English as an Additional Language) and PP (Pupil Premium). 5 is the highest challenge grade and 1 the highest for effort. Progress grades are assigned in relation to their challenge grades. T means that pupils are working towards their challenge grade, U means that they are working under their challenge grade and X means that they are exceeding it (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Information about the pupils recorded for this study, including their groupings, challenge, effort and progress grades, as well as their EAL and PP status.

In this section, to analyse the groups' discussion I will discuss the accuracy of the answers to the comprehension questions vocalised by the pupils. I will then consider if the pupils appear to be taking advantage of the ability to build up their translations and so the answers with their group. Finally, to analyse how effectively the pupils are using the Explorer Tool I will reflect on whether their pupil talk is exploratory and positively contributing to the collective aim. I decided not to collect the written evidence from this comprehension exercise as I was more interested in the process of the discussions than the output. Pupils may have all written down correct translations of the Latin and answers to the comprehension questions, but this would not necessarily have shown that they understood how their group has come to that conclusion or indeed that they had contributed. F. Hunt (Reference Hunt2018) found that the increased speed of translation enabled by the Explorer Tool sometimes led to a loss in accuracy, affected pupils' understanding and that some pupils were fitting the words together like a jigsaw. When I have observed this, it has involved pupils clicking on every single word in the Explorer Tool and then rearranging the English meanings to make a viable sentence without considering the grammar. Groups 1 and 2 both did exactly that. In both groups, a pupil clicked on the Latin words in the order they appear and read out the English meaning provided by the Explorer Tool. Now that they have the pieces of the puzzle, the next stage for the groups was figuring out how to fit them together. Both groups also appear to do this without vocalising their consideration of the grammar and the result is an interesting combination of the individual words. Caliban initially takes uxorem [wife] as the subject and so makes the verb plural, as well as attributing both adjectives to filium [son]. Gregory is also confused by the sentences and despite correctly agreeing optimum [best] with filium [son], changes his mind. Group 1 is the only group to use this technique in more than one instance, with no evidence of Groups 3 and 4 vocalising every word in order.

It is useful to know the meaning of all the words in the sentence before attempting a translation if one is going to then consider the grammar to translate the sentences. This could be beneficial for the groups as there are multiple people to remember the meaning of the words and help with the translation. However, the size of the groups allows for a loss of accuracy and understanding because success relies on communication within the group. At different points throughout all the groups' work, it is clear that one or more individuals have been left behind, either due to writing down their answer or because they do not understand the conclusion the group has come to. It is also possible that, if they do not understand the answer, it is because they were not involved in the discussion that led to that conclusion. These instances are most pertinent in Group 2 and there are multiple examples. When answering Question 5 about the contents and timing of Eupor's letter, Gregory and Hubert appear to be working independently of Edgar and Fabian, leaving them unsure of what their peers are doing. When Edgar attempts to contribute, this issue continues and he is shut down by Gregory. However, the communication between Gregory and Hubert deteriorates and they are both contributing their ideas independently with little connection or response to one another.

Example 1:

Gregory: [[Question] number 5, and then, and then he wrote a letter. When did he write his letter?

Hubert: Wait – he invited Rufus to what?

Gregory: To his wedding.

Fabian: Number 5 is he wrote his letter.

Gregory: At last

Fabian: What is he saying I? What is number 5?

Edgar: I don't know

Example 2:

Edgar: It says yesterday. It says scripsit.

Gregory: It says soon.

Hubert: Oh, that's right.

Gregory: Soon, he soon wrote his letter.

Hubert: No suas is him, her, their, their.

In contrast, there are instances when pupils clearly try to incorporate the contributions of others into the group or their own translation. The communication between Gregory and Hubert improves and Gregory adds Hubert's suggestion to his existing translation. This does unfortunately result in the word ‘soon’ being translated with the incorrect clause. In other groups, pupils also continue to use incorrect translations provided by others, for instance Group 1 become convinced that saepe [often] means ‘sometimes’. Often, pupils are using more than one of the options provided as a meaning by the Explorer Tool and continue to do so in their final answer or translation. This can be seen in the discussions of Groups 1, 2 and 3. In Group 1, Banquo initially provides peaceful and calm as two separate options of the translation of placida [peaceful/calm/faithful] as provided by the Explorer Tool, but after further discussion by the group and the addition of the adjective ‘faithful’, the two options have become two separate terms. Similarly, when Group 3 collate the information that they have about Plotina in order to answer the first question, they do not include ‘faithful’ and repeat ‘peaceful’ and ‘calm’ as two separate attributes, having established this premise in earlier discussion. Group 4 appear to be the exception here and instantly clarify the one opportunity for them to make this mistake:

Example 3:

Gregory: Going back, he sent the letter after going back to Athens.

Hubert: No, it says soon, though.

Gregory: Yeah; he went back to Athens soon, then he, he then…

Example 4:

Caliban: Plotina is peaceful, calm, and what did you say?

Banquo and Caliban (simultaneously): Faithful.

Banquo: No; peaceful and faith.

Caliban: Peaceful, faithful and calm.

Example 5:

Iago: Woman, yeah, is a calm and peaceful woman.

As well as correcting others, pupils are able to use talk to lead the group through their own thoughts and correct themselves simultaneously. Simply being able to express their ideas aloud to others helps them process their thoughts. Caliban adjusts his translation from ‘Barbillus sailed’ to ‘was afraid to sail’ in the same sentence, and does the same again when translating line 4 of the passage. In addition to this self-correction, pupils are able to discuss ideas (Gibson, Reference Gibson2001, 42) and often repeat information in order to reassure others that they agree with what that have and to confirm that they have heard them correctly.

There are also times when pupils speak more slowly in the recording where I believe they are repeating the translation or answer as they write it down. In Group 1, Banquo repeats what Aragon has said exactly, as if in consolidation, and the same occurs in Group 4 between Mercutio and Quintus. In Group 2, this process is slightly more staggered. Hubert has to feed Fabian the information in sections. In Group 3, though there are instances of exact repetition, and the group's tendency is to repeat information as more details are added. This occurs when they discuss Eupor's letter and when they culminate their answer regarding Plotina's character.

In addition to this process of collaboration, group work can be a great opportunity for pupils to read Latin aloud (Lindzey, Reference Lindzey2003, 9). Pupils say Latin words aloud to the group to share the meaning of a work or to ask others for the meaning. Question 2 of the comprehension asks ‘Why is iuvenis impiger (line 3) a good description of Rufus?’, resulting in pupils repeating the question aloud and so speaking Latin. Iago and Joseph in Group 3 use reading the Latin aloud as part of their translation process. They read every word and check the meanings of them in the order they appear, but also work together and correct each other. This reading of the Latin aloud is used to even greater effect by Group 4 when discussing the first sentence Barbillus uxorem fidelem filiumque optimum habebat [Barbillus had a faithful/loyal wife and a very good/excellent/best son]. The -que and adjectival agreement caused issues with all of the groups and Oberon asks if the optimum agrees with the uxorem [wife] or filium [son]. He says, ‘is it the best wife or best son?’ Mercutio decides that they are going to figure it out and check. Though the group checks the meaning of every word, they also state the Latin word as they do so. Multiple options are given and when Oberon gives the translation as ‘faithful wife and best son’ it is accepted by the group, although it appears that Oberon has taken the final step to come to this conclusion alone:

Example 6:

Iago and Lennox: Barbillus uxorem fidelem…

Iago: uxorem is wife, right?

Joseph: Barbillus habebat had

Example 7:

Iago: So Barbillus' wife fidelem filiumque optimum habebat.

Joseph: So Barbillus had…

Example 8:

Oberon: Is it the best wife or best son?

Mercutio: Er, I don't know. No; actually, we can work this out. It's the best wife, it's the best wife, fidelem optimum…

Puck: Huh?

Mercutio: fidelem optimum, best wife.

Puck: uxorem is wife.

Oberon: fidelem means loyal. optimum means best.

Mercutio: uxorem optimum.

Oberon: But you also have uxorem fidelem.

Nathaniel: Let's write down what we know about them.

Oberon: Faithful wife and best son.

Though pupils spoke the Latin aloud and discussed the meaning of the Latin words, there is very little use of grammatical terminology or even terms such as subject and object. Wright found that the use of such terminology was not necessary for pupils during translation (Reference Wright2017, 19) and Francis Hunt's study found that pupils simply considered the grammar less when using the Explorer Tool (Reference Hunt2018, 47). I would agree that in my case study it was not necessary for pupils to discuss grammar or use grammatical terminology. There is little evidence for pupils' consideration of the grammar beyond adjectival agreement, but when they do consider the grammar closely, they are using grammatical terminology. It is not clear whether Joseph is referring to Rufus or impiger given the context, but either way his statement ‘nominative masculine. Rufus is lively and energetic’ would be correct. At another point, Lennox asks if amicis is singular or plural. Knight points out that although the Explorer Tool translates the word as friend it has not taken the ending into account. This example shows how the pupils are using their groups to engage in critical thinking and problem solving by considering the information provided (Gibson, Reference Gibson2001, 42).

Example 9:

Lennox: That's what it translates to. With his friend. Wait is it friend or friends?

Knight: Look it translates as friend, but amicis is plural.

The processes that allow for these skills to be developed can involve exploratory pupil talk. The problem, in this case the Latin text, does not need to be solved alone and can be discussed aloud in a safe environment with peers. Exploratory talk can be demonstrated by specific words or by pupils improving on one another's ideas and eventually coming to a group consensus (Mercer, Reference Mercer2000). Alternatively, pupils may become competitive and make decisions as individuals. Mercer classes this kind of talk a ‘disputational’ (Reference Mercer2000, 157). To assess whether the pupils were using the Explorer Tool effectively in small groups, the final part of my analysis of their discussions will focus on these aspects of pupil talk. A more effective use of the Explorer Tool would be to work together to answers the comprehension question and translate the necessary Latin, bouncing ideas off one another and improving answers collaboratively. I assumed this would be partially orchestrated by the iPad to pupil ratio (1:4/5) but it seems to have been more dependent on the attitudes of the individuals in the group. All groups show positive aspects of collaborative discussion and teamwork but not throughout the entire exercise. From their conversations, at different points the groups split into pairs, individuals move ahead of the group and the group relies on an individual. Group 1 construct their answer to Question 3 about Rufus' relationship with his parents as a group. Aragon and Caliban supply the information from the text and Banquo amalgamates it, showing his understanding of what his peers have said, However, this team effort was not there continuously. Prior to this, Aragon and Caliban appear to have moved onto the next question and are ignoring Banquo's pleas for help:

Example 10:

Caliban: Parents, Rufus…

Aragon: But Rufus most of all loved…

Caliban: But Rufus' parents loved him most of all.

Aragon: Yeeess -

Banquo: It's a love hate relationship.

Caliban: Yes; because he has arguments with his parents.

Example 11:

Banquo: Wait; we need another reason for number 2.

Caliban: In the desert, the wild beasts, the ferocious wild beasts, chased, were accustomed to chase…

Banquo: Wait! What did you put for number 2? I got…

Caliban: I got ‘because he sometimes exercises with his friends.’

Banquo: Yeah, but that's only one reason.

Aragon: Ferociously, be accustomed.

In Group 2, Edgar and Gregory manage to reach the correct translation of the first line of the passage but only as a pair. The pair continue onto the next line. but Edgar takes the reins and then Fabian contributes. This fluid movement in and out of the discussion is apparent in all the groups, but manifests negatively in Group 3. Fabian realises that Gregory is answering question 6 when the rest of the group is still answering question 3. The repercussion of this is that Gregory attempts to guide the group through the questions but ends up giving them the answers. A similar series of events occurs at the end of Group 4's discussion where Mercutio provides all of the information required to answer question 3 and Nathaniel appears not to have listened. This group is capable of effective exploratory talk as they answer question 2 successfully as a group prior to this:

Example 12:

Mercutio: He studied medicine and he had arguments with his family, but he loved them. He was studying medicine and he had arguments with his family but he didn't actually fall out with them. He was just quite energetic and had arguments, but he still loved them – which is always nice, you know, and then – yeah…

Nathaniel: What have you got for question 3 so far? So he argued with his parents and what else?

Example 13:

Mercutio: Okay! Right! Is an energetic man because he likes to hunt…

Nathaniel: Er, we need two reasons, though.

Oberon: Sometimes argue with his parents.

…

Nathaniel: He likes to hunt – and what else?

Puck: He plays with his friends.

Disputational, individual, competitive work is less effective than exploratory group work and can in turn contribute to how efficiently a group function. Though the speed the groups were working at was not my main focus, I thought it would be interesting to make a comparison to Francis Hunt's Reference Hunt2018 study. He found that Year 9 pupils, working individually, were able to translate a line in two minutes without the Explorer Tool and that they worked at twice the speed when they had access to the Explorer Tool (Hunt, Reference Hunt2018, 45). I did not collect data when the pupils were not using the Explorer Tool, so cannot make a comparison. However, all groups (1–4) completed four questions which required the analysis of eight lines in 13 minutes. F. Hunt found that the Explorer Tool increased the speed of translation and here, the discussion that comes with group work can slow the speed of translation. On reflection, if I had been able to continue my research, I would not have asked the pupils to write down the answers to the comprehension questions as this appears to take up a large proportion of their discussion as they make sure they have written down the correct answer. One of the emerging patterns in their discussions was this repetition as approval, confirmation or as they were writing. However, this repetition is not always exact and can build on the ideas of others, as well as repeating their mistakes. It is possible that many of these mistakes are carried because the proposed English translation does not necessarily sound wrong. It may be incorrect, but it makes sense to the pupils, for instance it is plausible that Barbillus' son was faithful and his wife excellent. If pupils were taught how to use the Explorer Tool effectively, they might be more likely to spot these mistakes for themselves.

Conclusion

Pupils could use the Explorer Tool more effectively in small groups if given the time to settle in and given guidance about how best to use the tool. The Explorer Tool allows pupils to check the meaning of individuals words more quickly and though it provides grammatical analysis, pupils are not necessarily using it effectively. Pupils appear to pay little attention to grammar, and this can result in inaccuracies in translation and understanding. The format of group work ensures that in some respect pupils are engaged in pupil talk. However, it is then up to the pupils how and how much they contribute. Their interactions with their peers care unpredictable and sometimes ineffective.

The greatest limitation in this study was that it was only possible to conduct it in one lesson with one class. The confines of my situation having already limited it to an individual school. In addition to this, my study only considers what pupils choose to say aloud (Taber, Reference Taber2013, 97). It can in no way take into consideration the thoughts of the pupils that remained private. If similar research were to be carried out in the future, I would suggest the following improvement. Pupils should not be asked to write down the answers to questions where the focus is their discussion. This would increase the amount of qualitative data produced and improve the pupils' skills such as teamwork and communication. In practice, I feel that group work using the Explorer Tool could be productive if used over a considerable length of time as groups would become used to working with each other. Despite there only being one device within the group, it is still possible for pupils to work individually. It would be interesting to see if this still occurred when pupils worked in pairs.

Future improvements in the use of the Explorer Tool in Latin classrooms hinge on the improvement of pupils' use of the tool. This in turn is largely dependent on teachers. As the facilitators of learning in schools, we need to take the time to ensure that pupils are using the Explorer Tool effectively and efficiently so that it can be a useful tool in the classroom. This would mean explicit instructions, expectations and continued monitoring of pupil usage as well as their output.