‘Reading on a Kindle I forget I’m reading on a Kindle. It feels like I’m reading. Apart from the fact that it’s not as heavy, it feels like I’m reading a real book.’

‘Yes, [an e-book is real and] the same book, but not as pleasurable for all the senses.’

The e-book has been chosen. It has been obtained. A screen flickers to life – pixels on a smartphone app, or e-ink flowing into a new configuration of grey and lighter grey – and actual reading begins. The reading may be real, but is the book?

This chapter explores the actual reading event. Contrasting devices and platforms, it considers what kinds of pleasure readers seek from book reading and rereading (in different settings, and at different times), and the ways in which an e-book does or does not deliver such satisfactions. Examining aspects such as tactile dimensions of embodied reading, the role of the material object, convenience and access, optimisation and customisation, and narrative immersion, it contextualises original findings with recent empirical research on screen reading and offers insights into how, where, and when intimacy, sense of achievement, and the feeling of being ‘lost in a book’ can be found in e-reading.

The Pleasures of Paper

To the degree that scholarship can reach consensus on any point in the interdisciplinary field of reading studies, there is agreement that print remains the medium of choice for most readers. As Baron puts it, ‘the majority—sometimes the vast majority—say they prefer reading in print’.1 This preference is not the result of any overwhelming advantage in terms of comprehension. Pre-1990 studies using first-generation screens did find large differences, but experiments using more modern screens generally do not.2 In 2015, summarising late twentieth- and early twenty-first-century screen-reading research, Baron found that despite ‘nearly all recent investigations are reporting essentially no differences’ in terms of comprehension and speed,3 a broad conclusion more validated than challenged by later studies, including those employing newer technologies for data collection, such as eye tracking and electrodermal activity, that are undergoing constant and rapid advancement. Scrutiny is, rightly, constant. Fervour of debate on the comprehension question – meaningful to any reader, but an immediate and critical issue for teachers and governments making decisions about classroom technologies that affect an entire generation’s education – is such that even hints of potential new sources of data can trigger intense media interest.4 Meta-analyses of reading studies by Delgado, Vargas, Ackerman, and Salmerón (2018) and Clinton (2019) found some small advantages for paper over screen reading when it came to reference and educational texts, but not for narrative texts – the category that accounts for the majority of commercial e-books. Though advantages specific to particular groups (i.e. that older readers may read fractionally more quickly on tablet, or that readers with ‘poor vision’ may benefit from the high contrast of a backlit screen) are very real, the long-held dictum that most people, at most times, prefer print5 still stands. (Subtle differences can still be very important, as I will discuss later in the chapter.) This recognises the existence, and importance, of the minority who prefer digital. The question is what widespread and enduring enjoyment of the material print object means for readers’ experiences of the bookness and realness of digital book objects.

Enjoyment of the Material Print Object

In my own study, asking survey respondents ‘when you choose print, what are your reasons?’ elicited a wide range of responses, but among them many odes to the codex. As noted in Chapter 1, though materiality is not synonymous with realness, digital materiality offers powerful support for arguments regarding the realness of a digital object. Responses were varied and often poetic in their expression of enthusiasm for various aspects of the material object and the multisensory experience of interacting with it. (Not every respondent used the free-text boxes to deploy emotive language, but many did.) Common references to touch and the ‘tactile thing’, and abundant attention to book smell, emphasised what Mangen describes as ‘embodied’ experience inseparable from the ‘physicality of reading’ (and invite study via the holistic view that Hillesund, Schilhab, and Mangen embrace as an ‘embodied, enacted, and extended approach to the research on digital reading’).6 Many responses foregrounded the specific pleasure of lifting and holding a print book, as with ‘I feel more satisfied when holding a print book’, ‘the feeling and weight of paper in my hands feels good’, and ‘nothing for me will replace holding and reading a traditional book!’, a tether to one conception of realness summed up by ‘a real book is nicer to hold’.7 Respondents frequently used the words ‘hands’ and ‘hand’, but with a notable difference depending on medium. They conspicuously link the plural to print reading, as with ‘I much prefer to hold a real book in my hands’ and ‘Sometimes I just want the feeling of a book in my hands’,8 or measuring progress through a book by the weight in the left hand versus the right. They link the singular to digital reading, as with holding an e-reader in one hand on the beach, while distracted by children, or standing on a crowded Underground train.9

One aspect of pleasure frequently cited in relation to print, but not in relation to digital in this study, is aesthetic pleasure derived from the material object. Respondents found value in beauty (‘collector’s editions of print books have more aesthetic value than pixels’) and even requirement for beauty, as in ‘certain books are aesthetically necessary to me on paper—children’s picture books, art books, etc.’10 and noted that this appreciation was not just recognised intellectually, but felt. As one put it, ‘If the book has an aesthetic reason to be in print – such as format or pictures – I will always go with print. It’s more satisfying’.11 While some respondents noted that certain texts can be more beautiful and more artistically successful on screen, such as born-digital works like Emily Carroll’s graphic novel story Into the Woods, no one spoke of an e-reading device in terms approaching ‘printed books are a thing of beauty’ or ‘[hardcover books] are so pretty!’.12 Some noted particular pleasure in craftsmanship – ‘Print feels more indulgent, a luxury, particularly when reading well-produced hard backs – like sitting in a well crafted chair or wearing well tailored clothes – you feel the difference’;13 the enjoyment was not only from the object itself but also from appreciation of the effort and skill that its creation required, recalling how for some respondents, as discussed in Chapter 3, the effort of authors and editors is what makes e-books real. (While a parallel argument could be made for appreciation of the design of an electronic device, such as an iPhone, no one in this study made it – despite the intense feelings many of us have for our phones.)14 Some responses framed digital as an enemy of aesthetics, an assault on print, as with ‘digital alternatives ruin and take away the art of reading and the beauty of books’.15 But questions of aesthetics apply to print versus other print as well as to print versus digital, and other respondents noted that a print book can fail as an object: ‘small font size/tight layout/smudgy print on poor quality paper puts me off buying some print books’ or ‘I test out books in store and if the analogue is horrible, I buy an ebook’.16

While aspects of print books were sometimes noted as inconvenient, this did not necessarily detract from their desirability. Physical weight was simultaneously a cherished feature of print books and a primary reason to read digital instead. Few participants expressed any negative impressions of the sensory experience of reading print. Even if they considered elements such as beautiful endpapers17 as items they were willing to forgo as a trade-off with other affordances, participants were overwhelmingly likely to speak of such aspects in positive or at least neutral terms. When ‘materiality scepticism’ was aired in the focus groups, it often became one of the rare flashpoints of heated disagreement: disliking the smell of a new book, or the feeling of holding a hardcover edition, invited rebuke and scolding. Participants in my study are readers (as noted, nearly all survey respondents and all focus group and interview participants are regular readers of print books) and as readers are heirs to the traditions of print culture, including relationships to print as a material object. While they are not required to share the sentiments of ardent print admirers, they are inevitably in contact with discourse on the subject. (The formation and expression of bookish identity, of which acknowledgement and display of one’s appreciation for the material object is a part, is a thread I’ll continue to explore in Chapter 5.) One participant spoke for many in explicitly linking this form of pleasure to realness, as something print books have and e-books do not, can not: ‘when reading for pleasure, I need a real book in my hands, not just printed words on a screen’.18

Preference in Practice: Influence of Enjoyment of Print on Reading Choices

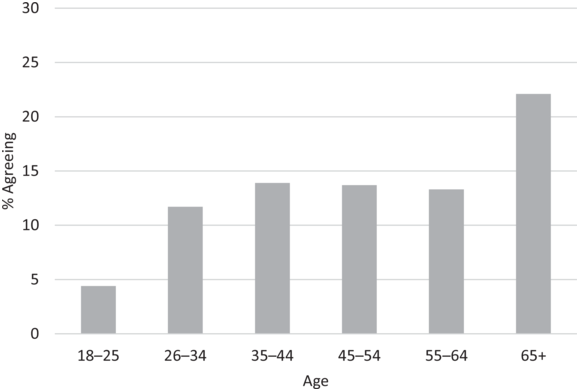

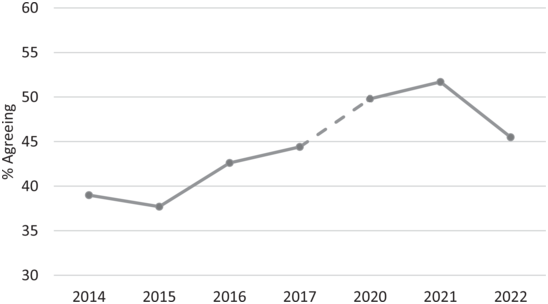

Taken on their own, these paeans to print could be dismissed as lip service. But survey results indicate that this appreciation for the physical object of the book is not a distant abstraction but a primary consideration in their reading choices: it is the single most important factor captured in the survey. More than two-thirds (67.9%) choose print because a print book is ‘more enjoyable to handle and use’. But younger respondents were even more likely to agree: 81.3% of those aged 18–25 versus 63.9% of those aged 65 or older (Figure 4.1).

Figure 4.1 Reasons for choosing print: ‘a print book is more enjoyable to handle and use’, by age.

A link between youth and enjoyment of print books is entirely plausible, particularly in light of younger respondents’ greater interest in print as a component of personal libraries (see Chapter 3), the continued dominance of print for children’s books,19 and signs of increased interest within mainstream publishing on the material object of a print book. James Daunt, CEO of Waterstones, speculated that the e-book option has forced publishers to stop ‘cutting back on production values’ and produce instead ‘proper books with decent paper and decent design’.20 Print-only readers (81.3%) were more likely to agree than those who read e-books (63.3%). But more than six out of ten e-book readers is still a large majority: most e-book readers still enjoy print, and choose print (when they do choose it) for the pleasure. This underscores the fact that avoidance does not necessarily mean dislike, or even indifference, as even the most devoted digital readers can still value the pleasures of print. It also underscores the fact that enjoyment of the material object of a print book is not by itself enough to make someone a print-only – or even a print-ever – reader.

Enjoyment and Book Buying

Enjoyment of print is not an isolated taste. Choosing print because a print book is more enjoyable to handle and use is strongly and positively correlated with obtaining print books from every source in the survey, including Amazon, libraries, and gifts. Of those who choose print for this reason and also read e-books, they were slightly more likely to have obtained them from Project Gutenberg. Links to Amazon, the main source of e-books, are more complex. Between 2014 and 2017, those who chose print for enjoyment were significantly more likely to obtain their e-books from Amazon (76.7% vs 56.3% of others, purchase and loan combined). But in 2020–22, splitting out purchases and loans reveals that those who enjoy print are completely ordinary in their Amazon purchases, but markedly less likely to borrow from Amazon (17.4% vs 30.0% of others). (This is not a blanket aversion to e-book subscription services: they were typical in their use of non-Amazon services such as Scribd.) Differences in device use were minimal: those who chose print for enjoyment of the physical object were slightly more likely to have read e-books on laptop computers (41.6% vs 30.6%), but otherwise typical in this regard.

Much more strikingly linked than reading behaviour are certain reading preferences and values (though not always the preferences and values one would expect). Unsurprisingly, choosing print books for enjoyment of the material object correlates with choosing print books because they are easier to read (58.4% vs 18.5% of others),21 but it is not the most dramatic correlation: these are a belief that print is better for keeping as part of a personal library (77.5% vs 36.5%)22 and a desire to support traditional bookshops (56.9% vs 16.5%).23 Other significant correlations are with choosing print because of identification as a bibliophile (44.8% vs 13.1%), because print books are better for giving as gifts (59.8% vs 29.3%), and because print is better for borrowing or buying secondhand (62.0% vs 32.0%) and, to a lesser degree, because print is better for privacy (14.0% vs 3.1%), print being easier to share (34.4% vs 18.7%), and print having better selection (16.5% vs 6.5%). (The unsurprising relationship between enjoyment of print and bibliophilia is discussed in greater detail in Chapter 5.)

This further emphasises a cluster of linked priorities. Placing a different variable in the centre offers a glimpse of a subtly different web of relationships, and examining print as enjoyable highlights particular closeness to what could be described as ‘book experiences’, but not all book experiences (e.g. gift-giving to a greater degree than book sharing).

‘Materiality’ of E-books: The Physical Object Trapped in Scare Quotes

Compared to the codex, the e-reader does not demonstrate the same capacity for inspiration. To participants in my study, the material object of an e-reader was not just an inferior object: in many exchanges, it barely registered its existence as an object. Study participants were not in any way confused about the fact that users only encounter e-books via some physical interface. They are entirely aware that while ‘texts displayed on screens’ can be described as ‘intangible and virtual’ and ‘are physically separable from their display medium’,24 this means that e-books can be moved between physical display media and stored apart from them, not that e-books could ever be read intangibly; it is self-evident, too obvious for them to mention. But much of the vocabulary of digital reading – virtual, cloud, file, download, and so on – foregrounds the untouchable storage or transfer stage rather than the reading stage; and in my focus groups and interviews e-books are often referred to in terms of their untouchable states as ‘just all, like…data’, ‘a big Word file’, or a ‘Word document’, or with characteristics like ‘tangibility’ linked with a definition of ‘book’ that excludes digital, as with ‘on a screen … it feels less tangible, like it’s not really there’ and ‘there is something wonderful about the tangibility of a book. I just don’t see myself switching to digital’.25 While print enjoyed its own rich vocabulary of sensory pleasures, the physical interface with digital was rarely praised, and compared to that of print rarely even mentioned. Very few comments touched in any way on the physical characteristics of the e-readers, and those that did, such as ‘I also like my kindle as a tactile object – it produces a certain kind of intimacy’26 often expanded on how that ‘tactile object’ is valued for what it does (in this case, foster closeness) rather than what it is. An exception, of course, is ‘screen’. This term carries enormous weight in discussions of e-reading, in part because it is almost the only term that has meaning across all devices (in contrast to words such as ‘e-ink’ or ‘app’ or ‘keyboard’ or ‘touchscreen’ that apply to some but not all common devices.) While there is no reason why an e-reading interface need be touched (e.g. the technology to project text onto a surface viewed but not held, and for actions such as turning pages, ‘flipping’ back to a previous passage, annotation, or starting or pausing an audiobook to be handled by voice commands is long since in the mainstream), the e-book reading interfaces common to the market and described by study participants are touched, and largely (excepting laptop and desktop computers) handheld.27 Exchanges in my focus groups and interviews demonstrate how discussion of e-reading and pleasure can flow around issues of e-book materiality, as participants respond to questions about the e-reading object by describing instead what they like, or do not like, about the book-object it is not. E-books are sometimes ‘light’ but more often ‘lighter’; sometimes ‘easy’ but more often ‘easier’.28 (To describe new reading technologies in relation to an ancient reading technology is logical and unsurprising, and the questions, asking about print and digital separately but side by side, were always likely to elicit direct comparisons, but the asymmetry is still striking. For more on narratives of revolution versus narratives of conservatism and continuity in technology adoption, please see Chapter 5.) Discussion of the materiality in relation to e-books is primitive, constrained by a self-evidently false yet highly persistent conception of e-books and other digital texts as bodiless; to return to Gitelman, signalling ‘a certain ambivalence about the bodies that electronic texts have’.29 But in the years since, discourse on e-book materiality remains thin and barren compared to the vivid complexity and sensory richness of discourse on print book materiality. (The study of textual materiality enjoys its own academic discipline, and as a theme in fiction and belles-lettres it is a genre in itself.) Readers are perfectly aware that e-books, like all electronic texts, have physical form, whether the form is as readable as projection of letter forms on a backlit screen or as unreadable as binary data inscribed on a hard drive.30 Yet electronic texts remain ‘elusive as physical objects’ and hence ‘digital texts can seem to have no body’ even if on an intellectual level the reader knows that this can’t be true.31 For participants in my study, personal accounts abound with descriptions of the tactile dimension of book appreciation, Dibdin’s ‘pleasures of sensual gratifications’ in the look, feel, smell, and sound of pages (though even the most enthusiastic admirers of print in my study drew the line at taste, rolling their eyes at a record collector’s belief that vinyl has a ‘flavour’ and dismissing concerns about used books and germs with ‘it’s not like you’re licking it’).32 At the same time, e-books frequently ‘seem to have no body’, even among those who enjoy digital reading and reading devices. Placed alongside the print book, the sometimes-disembodied e-book is experienced as less present, less complete because it is not entirely there.

Enjoyment of E-reading Devices

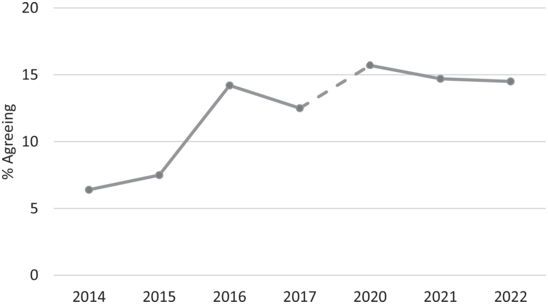

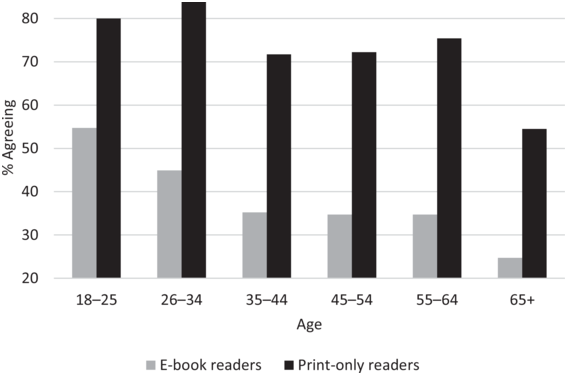

Enjoyment of e-reading devices is a minority taste. Asked about their reasons for choosing digital, ‘an e-reading device is more enjoyable to handle and use’ was cited by only 12.1% of e-book readers. It presents a near-mirror of the enjoyment of print profile, with enthusiasm rising rather than dropping with age (Figure 4.2). Respondents aged 65 and older were five times as likely as those aged 18–25 to choose digital for this reason.

Figure 4.2 Reasons for choosing digital: ‘a reading device is more enjoyable to handle and use’, by age.

Only continued monitoring will determine whether this is an enduring effect, and if so whether it is a matter of age or instead linked to generation. For now, the youngest respondents’ lesser agreement is likely to reflect the importance they place on the tactile dimension of print books, harmonising with their greater enthusiasm for print personal libraries (and correspondingly lesser interest in digital personal libraries). For the oldest respondents, reasons may be more practical. Survey and focus group respondents specifically linked the very commonly cited affordance of adjustable font size to age (‘I think digital books are very good for people with poor eyesight such as mature people’), as well as lighter weight and one-handed page turns; ‘Kindle works best when mobility is an issue because [of] arthritis’.33 (As I’ll discuss in greater detail later, in relation to convenience as a form of pleasure, older respondents were considerably more likely to choose digital because it is ‘easier to read’.)

Examining the values of the small minority that finds e-readers more enjoyable, one correlation stands out dramatically: 66.5% also find digital easier to read, compared with only 14.7% of others.34 If enjoyment of e-reading devices were strictly a matter of convenience, one might expect to see equally strong correlations with other convenience factors. However, ease and speed of obtaining e-books, like value and availability, have weak or no connections to enjoyment of e-reading devices. (The e-bookish values of finding digital better for keeping as a personal library and finding digital better for selection, in contrast, are more strongly correlated, though still in the shadow of ease of reading.) Other than being slightly more likely to have read an e-novel in the past twelve months, those who found e-readers more enjoyable to handle and use were not distinctive in their e-book genre choices or sources of e-books. Sources of print books were, in fact, more revealing than sources of e-books. Those who enjoy e-reading devices are less likely to have obtained print books from the typically in-person options of chain bookshops, independent bookshops, and secondhand bookshops. This indication that those who enjoy e-reading devices are less frequent consumers of print books, but generally ordinary consumers of digital books, contrasts with print enthusiasts (who are more active consumers of print but ordinary consumers of digital) is potentially quite telling: these enthusiasts may be not reading digital instead of print but reading less overall.

Perhaps surprisingly, there are no meaningful relationships to device choice. This counterintuitive finding challenges current thinking: as the interfaces and affordances of various e-reading devices are so different, it was unexpected to find that the minority of readers who hold this view are relatively normally distributed. This finding suggested that what readers are responding to, what actually gives pleasure as they ‘handle and use’, was not necessarily something physically bound up in the reading device such as size of screen, location of buttons, or system of navigation, or even e-ink versus backlit screen (a very surprising result given that readers consistently find e-ink less fatiguing).35 (It is important to keep in mind that these populations of device users are not separate but overlapping: most e-book readers in my survey used more than one reading device over the past twelve months. Hence, their feelings about device usage are informed by experience with more than one interface, and their response to the question may refer to aspects of one interface or multiple interfaces.) This could indicate that readers are responding to some aspect common to different e-reading devices, such as adjustable font size. Another possibility, however, is that the appeal lies in a mode of reading where the physical object is temporarily forgotten. This possibility is one I’ll explore in greater detail later in the chapter, as we consider e-reading and immersion.

While there is an extremely small population of respondents who choose print because a print book is more enjoyable to handle and use and choose digital because it is more enjoyable to handle and use (1.3%), these are for the most part incompatible preferences.

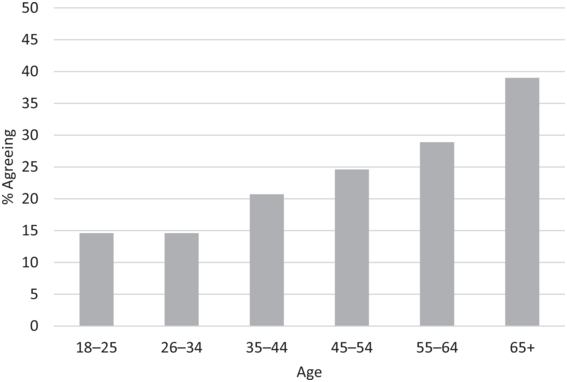

The Rise of Enjoyment of E-reading Devices

Enjoyment of e-reading devices did vary significantly by year: while remaining very low compared to enjoyment of print, enjoyment of e-reading devices doubled over the eight-year span of the surveys, leaping upwards between 2015 and 2016 (Figure 4.3). There was a dramatic increase, but not one obviously linked to increased e-reading during the pandemic.

Figure 4.3 Reasons for choosing digital: ‘a reading device is more enjoyable to handle and use’, by year.

Given the general lack of relationships to most demographics, sources of e-books, most genres of e-books, and choice of device, it is reasonable to conjecture that this is a genuine increase. Since February 2014, e-reading technologies have developed (though nothing to rival e-ink breakthroughs of the 2000s), and Amazon, the primary source for e-books in my survey, has introduced new functionality for both Kindle devices and Kindle apps. Pew Research Centre estimates that although Americans’ laptop/desktop computer ownership was approximately stable (at roughly three-quarters of adults) between 2014 and 2021, tablet (to roughly half by 2021) and particularly smartphone (to more than five out of six in 2021) ownership increased.36

For dedicated reading devices, the trajectory has not been ever upward, or ever closer to any one idea of ideal screen reading – or whether that ideal includes emulation of the codex. Pew Internet has not asked about e-ink reader ownership since 2016, but it is interesting to note that the last data, collected in November 2016, found that ownership had rebounded from 17% in spring 2016 to 22% in autumn 2016, calling into question the dominant story of plummeting e-ink reader ownership.37 Further iterations of the Kindle introduced new features, some of which address (or are meant to address) kinesthetic dimensions of interaction with the text. The PagePress haptics of the 2014 Kindle Voyage offered tactile feedback in the form of a very slight push-back on the reader’s fingertips when transferring to a new page.38 This feedback was very different from the tactile experience of turning a paper page, but is timed to offer some sensory input that coincides with the same action, punctuating the reading experience at a similar pace, and presumably to give readers some of the ‘whole process of turning the page’39 that many in my own study value highly. Wired described PagePress to its audience of technology enthusiasts as, alongside the ‘grit’ of the very slightly textured screen, ‘tactile qualities that approach actual paper’.40 However, other new Kindle features were not designed to emulate paper but to introduce enhancements impossible in a traditional print book. The Kindle Oasis, the model following the haptic-feedback Voyage, abandoned PagePress and added, instead, additional ways to navigate, interrogate, and share the text. These included image-navigation systems, links to Goodreads, features such as Timeline, which promise a new way to keep track of and navigate between key points in a narrative, and X-ray, which promises the chance to ‘see all the passages across a book that mention relevant ideas, fictional characters, historical figures, and places or topics of interest’41 (a perspective familiar in the early 2020s to viewers of Amazon Prime Video, where paused programmes sprout links to the Internet Movie Database [IMDb]). For non-fiction books, the X-ray feature frequently appears alongside a traditional index as well as the more mundane Kindle search function, and might not represent a meaningful augmentation in terms of searchability, but for novels any indexing offered participants in my study a degree of pleasing novelty (the long history of indexing fiction notwithstanding).42 Some focus group respondents had tried X-ray, and reported that it ‘tells you about the characters’ in a way that was genuinely new to them; the resource was often primitive and trivial (‘quite often it’s just a few sentences from when they first appeared’), but sometimes detailed and useful (‘in some books, you get a huge amount of information’).43 This opening up of the text to elements from outside, institutional or crowdsourced, are the kinds of ‘word-based enhancements’ that McCracken considers to be ‘centripetal trajectories’, forces drawing the reader more deeply into the text44 but into the text via avenues impossible for print. And in an advance that offered a desirable but profoundly ‘unbookish’ (or at least unpaperish) shift, the Voyage fulfilled the dream of generations of beach- and bath-readers: it is, at least to a depth of two metres, waterproof. (Though no participants in my study mentioned this Kindle feature, their enthusiasm for beach reading and avoidance of digital near water, for example, ‘read in the bath – don’t want to drop electronic devices in the water!’45 confirm that waterproofing would counter one key objection to e-reading. Amazon’s later decision to incorporate waterproofing into not only its then flagship model, the Oasis, but its midrange Paperwhites,46 attests not only to the feature’s value to readers but also its value as a luxury add-on: something that, like freedom from advertising, that differentiates the plus model from the basic model.) More recently, the 2022 Kindle Scribe introduced limited forms of written annotation. The stylus allowed for scribbling notes in the margins of PDFs, though not yet in the margins of reflowable .AZW or .EPUB files. Annotations in e-books required creating virtual sticky notes: these handily translate between different devices and the cloud, preserving one’s personalised text in a way unimaginable before digital platforms, but are very far from faithfully replicating the experience of jotting down thoughts in a print book.47

Amazon’s decision to quietly discontinue the haptic-feedback Voyage in 2018 did not represent a wholesale rejection of the bookness strategy. Rather, it indicates continued experimentation with emulation of print, adding and removing features in a search for combinations that tempt – for the lowest possible cost – the greatest number of customers, and advance Amazon’s broader agenda of folding users ever more deeply into the Prime membership ecosystem.48 Designers began the Kindle project ‘“pushing for the subconscious qualities that made it feel like you were reading a book”’ and continue to do so – while still serving Bezos’s reported directive to ‘“proceed as if your goal is to put everyone selling physical books out of a job”’.49

The Incomplete Book

This rich experience of materiality for print books, and thin, oblique, elusive experience of materiality for e-books, means that when it comes to enjoyment of the physical object, e-books do not function for readers as real: a piece is effectively missing (at least part of the time), leaving a void in its place. This is a form of unrealness very different from the unrealness of a digital proxy or ersatz book. The incomplete book is not so easy to present as an inferior replacement; it is only a real book chopped (by no fault of its own) into pieces, more to be pitied than feared. And the metaphor of the incomplete book suggests at least the theoretical possibility of ascension to realness. If it could by some means be reunited with the rest of itself, the incomplete book would become a real book, in a way that an ersatz book or proxy never could.

Convenience as Pleasure

Convenience is its own form of pleasure. To participants in this study, it is more than removal of barriers to enjoyment; they ‘enjoy the convenience’ itself.50 Noted explicitly by a great many participants as a reason for choosing digital, the term encompasses a wide range of practical concerns and emotional responses, from the brisk ‘it saves me having to drive all over town’ to the emotive ‘love the accessibility and convenience of digital’ and ‘embrace’ of certain conveniences as ‘godsend[s]’.51 Convenience can mean luxury, but also freedom, equal access, intimacy, and power. The beneficiary, however, is not always the reader.

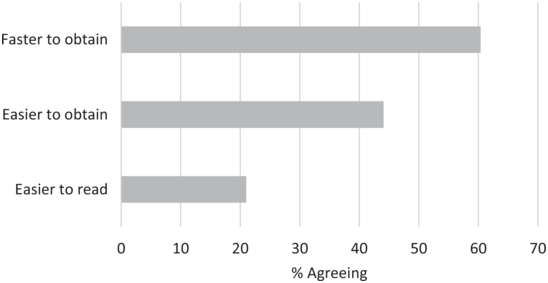

Relative Value of ‘Ease’: More Important for Obtaining E-books Than Reading E-books

Looking at all survey respondents, just under half (45.6%) choose print because it is easier to read. But even for those who read e-books, optimising for ease is not as simple as a direct swap: only 36.7% of those respondents choose print because it is easier to read, and only 21.0% choose digital because it is easier to read (Figure 4.4). This figure of one in five might on the face of it seem low, but convenience plays a greater role earlier in the process. More than twice as many (44.1%) choose digital because it is easier to obtain, and three times as many (60.4%) because it is faster to obtain: one 2015 survey respondent spoke for many in choosing digital because it is ‘faster to buy e-books’.

Figure 4.4 Reasons for choosing digital: ‘convenience’ factors (e-book readers only).

‘Faster to obtain’ and ‘easier to obtain’ were closely correlated,52 but still separate. Fewer respondents were motivated by ease than speed, perhaps in part because some found e-book purchasing and borrowing to be a finicky process (see Chapter 3).

The appeal of speed is widely shared and largely stable: agreement with ‘faster to obtain’ did not vary significantly by year (though it peaked at 68.6% in 2020, during the first lockdown) or according to any demographic measure. A number of survey respondents noted that work reading was often particularly time-sensitive (and, in fact, the connection for laptop but not desktop computers may indicate that it is working outside the office, e.g., on business trips, research days, or out-of-hours work, when print copies are not always to hand, that speed is a higher priority). The key word is ‘sometimes’: they frame it as a strictly emergency measure. ‘Sometimes, if I need to start something quickly as research, getting [e-books] is immediate’, or ‘sometimes, I need a play script for use at an audition…when that’s the case, I tend to need it quickly (no time to wait for shipping)’, or ‘sometimes, when I need to read something quickly for learning, I opt for the ebook’.53 The link to work reading is unsurprising: Buchanan, McKay, and Levitt’s 2015 study of academic e-book usage indicated that even where print was preferred, digital was often the choice for speed (and that while academics in the study tended to use laptop computers for quick reference when off campus, students often turned to smartphones for academic purposes ‘when the phone is the “to-hand” device’).54 To take advantage of such an affordance is not described as luxury so much as failure; admission of guilt for having been caught short, as with ‘I have my paper to write, and there was this one book… I needed it quite urgently, because it was a bit late? I was procrastinating a bit…that’s why I bought it. From Amazon’.55 But obtaining books quickly and easily offers its own kind of satisfaction. Participants explain that they enjoy the ‘instant gratification’, and like the ‘instant access to many books’, especially at the height of the pandemic, when ‘the instant accessibility [of e-books], especially during lockdown, was a huge boon’.56

‘Easier to obtain’ did rise during the pandemic, peaking in 2021 at over half (51.7%) of respondents who read e-books. Qualitative data from 2020 to 2022 underscores how many pandemic-specific issues made e-books more obtainable and print books less, from the extremely frequent mentions of library and bookshop closures (such as ‘I began reading ebooks when my library closed down due to covid. Even once they opened back up for borrowing, ebooks are more available than print’), to new and/or temporary sources (as with the ‘Internet archive pandemic library’),57 to safety concerns not only with bookish settings but also the books themselves (‘borrowing an e-book from the public library is safer, no bedbugs or Covid’).58 Agreement in 2022 had already fallen to near-pre-pandemic levels (Figure 4.5).

Figure 4.5 Reasons for choosing digital: ‘easier to obtain’, by year.

Non-UK residents valued it somewhat more highly; this group included a number of expats, some of whom used free-text comments to underscore how e-books are the ‘only cost-effective’59 means of obtaining desired English-language titles in some parts of the world. Those who choose digital because digital is easier to obtain were more likely to have obtained e-books from libraries, and somewhat more likely to have obtained them from Project Gutenberg, Amazon, non-Amazon online retailers and, intriguingly, chain bookshops.60 The library advantage could be due less to some special convenience of library online interfaces than to a comparison (even before the pandemic) to physical libraries, particularly e-books being ‘easier to quickly borrow from the library without attending’ as well as ‘easier to return to the library’.61

The Portable Text and the Flexible Reader

The portability of e-books is perhaps the most frequently mentioned affordance in the free-text boxes of my survey. Movement between devices is a predictably common theme, with respondents appreciative of the ability to ‘change between [their] devices for e-reading, my kindle, laptop and mobile and read the same book and be bookmarked at the same place’ and ‘you can read it on multiple devices and it always takes you to where you were in the book’.62 As one explains, this is not just handy, but wondrous: ‘if I have to get up and go for whatever reason I just put the book down and keep listening…basically, I never have to stop reading, which is wonderful’ [emphasis mine].63 But even more prominent is the role of e-reading in travel and the reader’s movement between spaces. A tremendous number of participants, across all surveys and focus groups, emphasised the value of e-books as a way to be sure of access to chosen reading material when away from one’s home or personal print library, either for daily travel such as a work commute, occasional holiday travel, or (as discussed in relation to ownership in Chapter 3), disruptive changes of residence. In addition to the frequent theme of access to a book (and sometimes to the ease of a one-handed grip on a device rather than a two-handed grip on a codex when on a crowded train), there is a powerful sub-theme of access not to a book but many books. ‘One kindle vs a number of books’ or ‘easy to carry more than 1 book with me’ goes beyond a few physical items in a suitcase, where one device can take the place of ‘taking multiple books on holiday’.64 This replaces a single item of commute reading with any book in one’s device storage – or, if the WiFi is working (not a given while travelling), almost any book in the world. ‘If I’m on the subway and the book I’m reading gets dull’, one explains, ‘I can switch to a short story, or comic, or completely different book without adding any extra weight to my commute!’65 It’s not only the ability to bring enough reading but also far more than enough: not just choice but surfeit, abundance beyond what could possibly be needed. It is ‘not running out of book while travelling’ and enjoying the fact that ‘tablet with a dozen books = no finishing book on bus and not having another’.66 The result is a reassuring plenitude, and freedom from the fear of ‘running out of book’ or being trapped with nothing to read but an inferior book.67

‘Plus you can take [an e-reading device] anywhere, and you always have a new book. So if you go on a train journey with a book you’re really excited about and it’s crap, you’ll probably be able to find another one.’

‘Gone are the days when I felt the need to carry two enormous hardcovers because I was almost done with my book – now I can just slip the kobo in my bag and have a backup that way. Abibliophobia begone!’

There is a specific kind of safety that comes from carrying, in addition to any books one might be reading, the books one is not reading, and are not likely to read. Some respondents very rarely use their device as an e-reader, but value having the reading there in case they ever needed it: ‘I bought a smart phone so I always have a book with me but I rarely use it for reading’.68 This language of ‘backups’ where ‘you always have a new book’ speaks to a conception of the e-book as real book. It recalls iron rations and emergency supplies: spartan, never used if there is a more sumptuous alternative, but adequate. A spare tyre is smaller and less durable and only used for short distances, but it is still a tyre, not a part of a tyre or a representation of a tyre or a tyre-shaped substitute. The e-book as spare book may be reserved for emergencies, but it still rolls down the road. (This kind of safety, and closeness, also represents a new kind of intimacy with books; as I discuss in Chapter 5, this offers a new way to be tied to one’s books and inseparable from one’s reading.)

The safety of e-books is, of course, undercut by the vulnerability of a device to theft, breakage, loss, or simply loss of power. While the need for meaningful ownership of e-books focussed on long-term threats such as changes to terms and conditions, retailers going out of business, and problems with inheritance and with download to generations of personal devices, the need for constant and reliable access to one’s reading material leads to concern over short-term threats. Readers place value on the safety net of e-books being there when wanted, ‘I always have my smartphone with me (no need to carry the book)’.69 They noted that ‘[print] removes dependence on power chargers’, that there is ‘no electricity required’, and asked ‘why use expensive electronic technology which requires power to operate, can fail or break?’.70 However, the nightmare scenario of booklessness was rarely realised: vanishingly few gave stories of specific instances where an e-book was unavailable, as with an account from 2020 of ‘I lost power recently and read a paperback for the first time in years’ that stood very nearly alone. Rather, they described hypothetical situations where an electronic device could fail them. This speaks less to the experience of unreliable technology than to the fear of it (though that fear is quite authentic, and a genuine motivation for choosing print as a ‘more reliable technology’).71

Some readers, however, find that carrying books one does not intend to read interferes with enjoyment of the book one is reading, preventing ‘commitment’ to one book.72 In this sense, e-books can be less intimate than print, or at least less monogamous; a young woman in a focus group was joking when she declared that ‘print is the wife and digital is the mistress!’,73 but the comparison does speak to the way in which a primary relationship is affected by the flagrant presence of a backup option. This added burden of a task, the need to select a book and ‘commit’ to that book, requires self-discipline and, for at least some readers, stands in the way of pleasure. (I will discuss the issue of choosing between books an aspect of digital distraction later in the chapter.) As with concerns over failing batteries and dropped devices, shot through the comfort of abundance is worry over the loss of it; new safety comes packaged with new fears.

The Accommodating Book

But a profound source of intimacy with texts is the way in which digital access allows some readers to integrate reading into settings, physical and social, previously incompatible with reading. The most common story is that of night-time reading. (Reading to manage insomnia is such a common theme that e-books as enablers of bed-based reading is a matter of health and well-being as well as pleasure.) The ability to read in the dark is a frequently cited affordance for participants in this study. Sometimes this is for the convenience of an individual, ‘don’t have to wake myself up to turn off a light, even a book light’ or ‘if reading at night I don’t have to have light on’ (or indeed ‘bedtime reading when I might want to switch books without getting up’) but often the light-equipped e-ink reader, or backlit tablet or smartphone, enables reading ‘without having to keep the light on’ so as to not ‘disturb my partner’, ‘disturb others’, ‘disturb anyone else in the room’ – area lighting for a silent activity being evidently disturbing in the extreme.74 The e-book does not bring books into a previously bookless space – the shared bed, where they have long existed – but merely eliminates the need for the exceedingly familiar technology of the bedside lamp or book light. The person being accommodated is not so much the reader as the reader’s partner. In other stories, the person being accommodated is not an equal but a customer, boss, or a beloved dependent. E-books are ‘easier to read between customers at work’ and ‘easier to wrangle while travelling…work travel is becoming quite difficult with print’.75 Nursing infants are particularly prominent as people whose needs can be more easily reconciled with e-reading than print reading: e-books are ‘easier to read during specific situations (when I wouldn’t be able to read a print book, e.g. breastfeeding in funny positions!)’ and ‘[e-books make it] easier to multitask, only needs one hand (for example, can breastfeed)’.76 Baby and toddler care makes the one-handed reading affordance particularly useful: ‘I was not expecting this, but with small children, I find [an e-book] easier to pick up and put down and read when I have limited use of hands’.77 But e-books are also invaluable for reading around childcare when the children are old enough to walk, talk, and take solo train journeys.

‘I know what I loved when the children were at school was I could be reading a book at home, I could leave it by my bed on the iPad and if they were late out of school I could carry on reading it on my phone, or whilst I was waiting for them to get off a train or something.’

Here, integrating a digital book with a previously bookless setting is not only a matter of taking advantage of a compact or backlit or portable interface. These stories are accounts of personal control reclaimed. Constraints imposed by the wishes or needs of other people – a supervisor, or a child being cared for – can be circumvented by putting the book in a different container, using a platform that is either physically convenient for the ‘funny positions’ of breastfeeding, physically durable and hence usable around small children, or unobtrusive (and possibly furtive) and able to evade notice. This use of protean reading to evade demands placed on the reader by other obligations and relationships, with its dimensions of gender and class, suggests that digital reading could amplify an existing ‘post-Romantic paradigm that makes reading the recourse of the poor, the lonely, the marginalised, the physically or socially powerless’.78 Those with power shape their environments to suit their needs, while those without power use reading to escape their environments. In contexts where e-books and e-reading devices are costly luxuries (as in 2007, when the first-generation Kindle cost over $400),79 this would represent a means of escape only for the ‘powerless affluent’, those who enjoy some economic advantage but not necessarily autonomy. But as reading-ready devices become less costly and more commonplace (as noted earlier, 85% of American adults, and 96% of American adults younger than age 30, now own smartphones) contexts where e-books become the ‘cheap’ option, particularly for academics and students at institutions where ‘electronic resources have grown as a cost-effective alternative to print resources’, offer a more direct parallel to the falling price of print and transformation of reading, in general, from ‘a sign of economic power’ to ‘the province of those whose time lacks market value’.80 The prominence of caring responsibilities, and possibility of a gendered aspect to this protean reading, also recalls enduring anxieties about women’s reading (especially ‘absorptive’ novel reading)81 as a strategy for escape from domestic duty. Devotion to reading has been depicted as a signal of insufficient devotion elsewhere, including outright neglect of children.82 Hence, centuries-old admonitions that women treat reading as an indulgence that should wait until work (including affective labour) was done, or even limit reading as a practice of healthy self-denial.83

Digital reading could in this context be seen as even more disempowered: while a reader with relatively more power may adapt their environment to enable the preferred print reading, for the reader with relatively less, the choice may be digital or nothing. As with the backlit screen for reading in bed, the text is accommodating, but the reader is not necessarily the one being accommodated. It can be seen in one light as ingeniously outwitting external control and in another as avoiding confrontation with external control, and potentially prolonging the dynamic. These findings problematise ideas of digital reading as appealing specifically because it pampers a reader with personalisation: the Amazon slogan of ‘read books your way’84 would be better described, for many, as ‘read books that get out of other people’s way’.

The e-book as accommodating book is in a curious position with regards to realness. Like the backup book, it does its job: the squeezed reading is still reading. But here, the e-book functions more as incomplete book: it is less the non-perishable, freeze-dried version for consumption in a blizzard than a portable slice, the smallest and least troublesome section taken along for some enjoyment even as all that is obtrusive, anything that might inconvenience others, is left behind.

Ease of Reading

The importance of ease of reading was stable: neither print nor digital varied significantly by survey year. This stability, in the face of advances in reading device technology and the increase in usage of tablets and smartphones over the period, suggests that, like enjoyment of an e-reading device, ease of reading digitally is not simply a matter of features on a particular device.

Ease of reading had intriguing relationships with age. Examining all respondents together, print-only and e-book reading, choosing print because it is easier to read dropped sharply with age (Figure 4.6).

Figure 4.6 Reasons for choosing print: ‘easier to read’, by age.

However, this trajectory was due to e-book-reading respondents, not readers on the whole. Separating e-book readers from print-only readers, the contrast is sharp. For e-book readers, the decline according to age is not a straight line – there is a sudden dip for readers aged 35–44 – but it is a significant correlation, and sees the youngest respondents twice as likely as the oldest respondents to agree. For print-only readers, it is not a steady decline but rather a sudden drop among the oldest respondents (Figure 4.7).

Figure 4.7 Reasons for choosing print: ‘easier to read’, by age, print-only readers versus e-book readers.

Choosing digital because it is easier to read, however, increased with age (Figure 4.8).

Figure 4.8 Reasons for choosing digital: ‘easier to read’, by age.

It’s important not to overstate this effect, as even among the oldest respondents only a minority agree, and conditions such as visual impairment are of course neither limited to nor universal in the oldest group. (For example, in one study cited by Phillips, participants with good vision preferred print for reading, but participants with impaired vision preferred screen reading.)85 Such affordances could be easy to dismiss as belonging to some lower category of pleasure: the means of overcoming a barrier to enjoyment rather than a source of enjoyment. However, the importance to an individual can be profound. As one respondent put it: ‘I have a visual impairment, so the ability to enhance font size etc in Ebooks is a real godsend’.86 Though the removal of difficulty may seem a small reward, ‘pleasure as less pain’ inspired emphatic responses. Fewer than one in ten (7.8%) chose digital because they are ‘helpful for dealing with a health issue that can interfere with my reading’87 – but fewer than one in a hundred print readers (0.8%) chose print for that reason.

A case in point would be the experiences of readers who use their chosen technology to overcome barriers presented by dyslexia. Dyslexia was cited as both a reason to use e-books instead of print (‘dyslexia’, ‘due to having both Dyslexia and ADHD…I have trouble reading hardback book due to the font’) and a reason to use print instead of e-books. (‘I believe my mild dyslexia also impacts on how much easier I find it to read hard copy text’).88 Studies of dyslexia and screen reading have found that there are aspects that may hinder as well as aspects that may help, indicating that two individuals, even two individuals with the same form of dyslexia, could have drastically different screen reading experiences depending on device and device settings. For example, glare from a backlit screen may exacerbate fatigue and reduce speed and comfort,89 but adjustable text and shorter line length,90 and larger characters and more space between characters, have been demonstrated to increase comprehension and comfort.91 Commercial screen reading products promise benefits, but these promises are not always supported by evidence. Amazon offers ‘Open Dyslexia’ font as an option for its Kindle app, though some independent studies have found no benefit from either Open Dyslexia92 or proprietary versions such as Dyslexie.93 What the respondents in this study have in common is that medium matters for their reading experiences, and choosing print or choosing digital is part of individual dyslexia management strategies.

Ease of reading, in print and digitally, had few links to device choice. When they do read on screen, e-book readers who choose print for ease of reading are more likely to have read an e-book on laptop (48.9% vs 30.8%). It could be that people who read on laptops are frustrated by the interface and hence are more likely to prefer print, or it could be that people who prefer print are less likely to bother with dedicated devices or even dedicated apps, and make do with browser windows. (Those who choose digital for ease of reading are more likely to read on smartphone, at 56.1% vs 44.4%, but have no other meaningful connection to choice of device).

‘Read Books Your Way’: Convenience as Power and Agency

Amazon sells Kindles (however misleadingly) as a means to ‘read books your way’. While e-book retailers (as discussed in Chapter 3) may at times be unacceptably controlling, e-books themselves are accommodating. They change their shape when readers ask it, altering font, text size, page turn animations, colour scheme, lighting, and so on. Many common dissatisfactions with e-books, such as inconsistent pagination and unwanted advertisements and comments, are ways in which an e-book changed when they did not want it to: the pliability of e-books is a benefit when the reader is in control, but a liability when the reader is not. (This, again, recalls the central role of control in relationships with e-books.) Many respondents in my own study noted ‘e-book adjustability functions re: serif/non-serif and font size’ and the ‘search function…for long/complex texts’ as exceptionally useful (particularly in relation to non-fiction reading), ‘attractive’ and ‘really nice’.94 Responses in this vein were particularly powerful when linked to disability or age-related impairments: ‘convenience’ in this sense is nothing less than equal access to books. The customisation affordances of digital are judged in the context of diminishing accommodation by mainstream print publishing. Some participants observed that ‘when it comes to magazines and newspapers they are making the print smaller (odd given the aging audience)’ and ‘as an avid reader with a visual impairment, eBooks have become increasingly valuable to me as print standards decline. Mass-market paperbacks are often badly printed and use a too-small font size’.95

Customisation: Comfort at the Cost of Ceremony

E-books offer tremendous opportunities for customisation. Some readers take full advantage of this affordance by personalising in ways reminiscent of commissioned binding:

‘I tend to specifically organise and convert [e-books] into the right file formats and procure the covers I like. Like fan-made alternative Game of Thrones covers and things because that’s much more fun, and the Penguin-style Harry Potter covers96 are great [note: participant showed samples on her personal iPad]’

But such flexibility is, to others, unsettling: one respondent found that ‘changing titles is a bit disrespectful of other people’s books, so I’m not quite sure’.97 Flexibility can be irritating, as when readers are confronted with disliked generic covers, or find that a book has become detached from a cover without their permission:

‘When I’m looking at my e-reader I really dislike it when I get a book down and they haven’t included the front cover [murmurs of agreement]…you’ve just got this Penguin logo or something and they haven’t put the front cover on.’

This interference with what is perceived as the normal and expected situation, with ‘normal’ defined with relation to print (where ‘the physical book…means that each book has a different cover’, unique and appropriate to that book even if elements of design are dictated by publisher or series)98 speaks further to a conception of e-book as incomplete book. Aspects such as Kindle popular highlights can be switched on and off by the reader, though in practice the means of doing do can be obscure, leaving readers the choice of either investing time in mastering the intricacies of Kindle settings or acquiescing to Amazon’s default choice. But customisation does help to combat what some readers describe as an inherent weakness of e-books: an ‘impersonalness’, ‘something that all looks the same’, lacking the distinctive annotations and even distinctive damage (‘I even like the occasional chocolate, bath water or similar stains on books’), where ‘there’s nothing different between your copy of [the book] and mine’.99

The pleasure of a compliant book is countered by a loss of pleasure where aspects of the print book experience functioned, for an individual, not as chores but as rituals. Some readers celebrate and enjoy the e-book’s transformation according to their needs, but others lament the loss of a sense of occasion, even ceremony. Some reminisced about treasured rituals of pre-order (for a few exceptionally awaited books, not everyday purchases) where they ‘had the pre-order form… “I want my Harry Potter book”…and then you would go in and queue up and the counter and get your book. In a nice little envelope’.100 Purchasing an e-book was in comparison, lacking.

‘It’s not as…special? You know when you go into a bookshop and buy a book, and you get it home and you’re really excited? [‘yes’, murmurs of agreement from group]…when you get a book though the post, that’s exciting? Whereas downloading a book is just like ‘eh’.’

Even the ‘the thump of a package on my doorstep’101 offers some excitement, compared to the ‘eh’ of online purchase, and this lack – another way in which the e-book is, to these participants, incomplete – further influences book-buying behaviour. As one put it, ‘the books I would hope for a sense of ceremony wouldn’t be the ones I’d be buying [in digital form] anyway’.102 Even settling down in a favoured reading spot ‘snuggled up with tea and a blanket!’ with a print book has the satisfactions of ritual for these readers: ‘There’s something extremely soothing and wonderfully visceral about settling down with a physical book’ one explained, ‘that I don’t think e-books will ever be able to emulate’.103

As Price notes, William Morris designed for non-compliance, creating awkwardly luxurious, luxuriously awkward tomes; ‘high-end, high-volume volumes’ that ‘offered conspicuous inconvenience’ to the discerning customer who enjoyed the money to buy them, the space to open and read them, and the time (as McGann argues) to decelerate and give the material object due attention.104 With e-books, readers do not have to approach literature; the literature comes to them, figuratively and literally. Not only do they no longer have to journey to bookshops, they no longer have to set aside a specific time for reading, or to return home, sit in a suitable chair, set down their coffee, or wait until the baby is asleep. Reading ‘when lying on the sofa or in bed’, buying or borrowing books while on a moving train to ‘get a book whenever I want’, and being able to ‘switch books without having to get up’ is a reading experience unrecognisable to even the most affluent (or lavishly supplied with personal servants) reader from an earlier era.105 The question is in how this affects their perception and experience of the literature: not only of the book-object (as with Morris’s volumes) but also of the text. If the reader no longer has to meet a text on its terms, but may expect it to adapt and meet them on theirs, does the reader’s relationship to a text fundamentally change? If an accommodating text grants new power to the reader, that might lead to a diminished power differential between readers and the publisher/authors, even reduction of reverence and deference, or indeed of esteem and respect. However, fan studies consider the effects of hierarchy on properties (textual and otherwise) where readers and other cultural consumers appropriate and remix; this kind of customisation facilitates intimacy and affect106 but does not necessarily disrupt hierarchy or diminish the distance between creators and fans.107 Choosing to access a book in print is often linked to esteem: most participants in this study find print better for collecting and better for giving, and some (as I will discuss later in the chapter) find it better suited for sustained concentration, and print books are hence often the ‘good books’ they honour with special attention and dedicated space.108 However, the link between print and esteem does not automatically translate into the reverse, a link between digital and disdain. As one survey respondent put it, digital is their format of choice for ‘things [they] think of as « lighter » reading (not lesser, mind) such as romance or funny books’109 specifically because such books are not of the types they usually collect, not because they are in some debased category of ‘lesser’ reading. It is worth remembering that if much digital reading, especially of novels, is ‘light’, so is much print reading. In a recent large-scale face-to-face survey of book purchasers in UK high street bookshops, Frost found that most buyers had chosen their print novels to gain ‘entertainment, escape, and relaxation’, with very few seeking ‘an intellectual challenge or for an aesthetic experience’.110 As one participant put it (to emphatic agreement from her focus group cohort), ‘the choice of [print] novels in the supermarket, they’re really all beach reads or best sellers’.111 I asked all focus group and interview participants whether they agreed with the statement that ‘digital is for “light” reading,’ but serious reading requires print. They were unanimous in considering that as a sweeping statement this was ‘rubbish’.112 They noted that while there were many instances where they and people they knew used digital for ‘light’ reading (including ‘beach read’ novels and ‘airport novels’),113 there were also many instances where they chose digital for ‘serious’ reading, especially when the book to which they needed quick or on-the-go access was not light entertainment to help pass the time on a commute (as much of their digital reading is) but an essential work of such importance that they could not be without it. This could be the ‘handapparat’ of a scholar who keeps her core texts to hand on a tablet or laptop at all times,114 but also a great work of literature that they could, or already do, own in print, yet download in digital form because easy access will help them pursue reading they consider important.115 It can even be the Bible, especially where it is ‘easier to take an electronic bible [sic] along to meetings’.116 Hutchings’s work on digital reading of devotional texts confirms that while some scholars express concern that digital access will change the nature of reading scripture, for example, by facilitating the reading of short sections with less emphasis on sequence or context, they are not concerned that digital access equates with disrespect.117 For Bible publishers (frequently distributing e-book and app versions for free) and readers that have made the Bible so successful on e-reading platforms, all access is good access: lower barriers means more time with scripture. According to Bible app developers YouVersion, ‘a striking 77% of users in a recent survey claim to “turn to the bible more” because it’s available on their mobile device’.118 If an individual considered digital formats in any way diminishing, they would probably not have chosen digital for their own sacred text. Accessing a book in digital form is not in itself an expression of contempt for that book. Further, there is not compelling evidence in these data for a link between an accommodating text and reduced reverence, deference, or respect: though one participant described someone else’s cover-altering customisation as potentially ‘disrespectful’, no one characterised their own customisation as in any way disrespectful, or as action that either generated or expressed contempt.

These ‘convenience’ pleasures are real pleasures, even if they are not universally shared; for some readers, the part of the book that is left is still capable of offering profound enjoyment. A further question is in how the unreal-because-incomplete e-book – flexible and accommodating, instantly available, spoken of as immaterial even when its materiality is beyond question – can or cannot offer a particularly treasured form of pleasure: the feeling of being ‘lost in a book’.119

‘Lost in a Book’: Distraction, Immersion, and Narrative Engagement

Deep engagement with a text requires not only overcoming external distractions but also achieving a state of focus, concentration, and connection. For a subset of participants in this study, digital reading presents considerable, even insurmountable, barriers to both.

Viewed through the lens of pleasure, distraction is not necessarily a problem. Though the possibility that the internet era presents critical threats to the concentration required for certain cognitively demanding reading practices,120 to ‘literary reading’,121 or to coherent thought,122 makes many commentators examine distraction as a danger to literature or literary culture, an individual reader might find distraction perfectly enjoyable. For at least some readers, especially those who enjoy switching between books and between reading and other tasks during travel, movement between media may be part of the fun, and books can be the thing that distracts as easily as the thing distracted from. But for many in my study, distraction was unpleasant, a thing that interfered with their enjoyment of books, and a reason to avoid digital reading.

For some, part of the pleasure of reading was to offer escape from the ubiquity of screens and digital interaction in daily life: an opportunity to ‘unplug’ and ‘get away from electronics’ after ‘spend[ing] all day staring at computer screens’.123 This ‘break from looking at a screen + does not involve using a potentially distracting electronic device’ only became more important during pandemic lockdowns, when participants reported they ‘have actively been choosing print books…to counteract all the zoom screen time’ and find it ‘nice to look at real pages during the pandemic, when we spend so much time on a screen’.124

For others, however, it was not the device but the unwanted opportunity to access alternative reading material. ‘Bringing ONE physical book to the coffee shop to read with [their] latte’ is sometimes essential as it ‘prevents literary multitasking: skipping from e-book to e-book on my Kindle’:125 a form of distraction where the competition is between e-books, a dark mirror of the pleasure of choice discussed earlier. ‘With e-books’, one focus group participant explained, ‘you can switch between them really, really quickly. Whereas if you’re out and about on a train, with a print book, you’re stuck with a print book, so you might get over the hill with the text’.126 Agreeing, another added that they feel they ‘have more of a commitment to a print book than an e-book’.127 Or, it could be a broader form of multitasking, with competition from non-book reading or non-textual digital entertainment. When on screen means online (as is the case for most reading devices) the ‘communication network’ can serve as an active antagonist to concentration:

‘When I read I am doing an activity that is specifically not screen time. In our Black Mirror society our entertainment is consumed in tandem with a communication network that doesn’t want you to ever get off of it. My nontech hobbies allow me to disconnect.’

The only recourse, for some, is to stop reading on screen.

‘I can’t read on my computer…I’ve tried, and I have the attention span of a newt… [general chuckles, agreement] Even if I like it, I struggle? To concentrate? [agreement] There’s just too much else to do, there’s too many tabs open, flashing at you. [agreement, ‘yeah, that’s true’]’

Devising an e-reading interface to combat such distraction could, in theory, be as simple as altering device settings. As the ‘slow reading’ movement manifesto would have it, turning off the WiFi is enough to meaningfully change the e-reading experience (though using a dedicated e-ink reader whenever possible also helps).128 But other research investigates the possibility that the screen itself presents serious barriers to concentration and engagement. This explores distraction in the sense of the reader/viewer/listener’s ‘mind wandering’, the competing demands on attention not as alternative information or entertainment options on a multi-use or network-connected device, but as ‘thinking about other things’, with distraction defined as ‘the presence of thoughts that are unrelated to the narrative’.129 Empirical studies of the experience of reading immersion are, like reading research in general, carried out in a wide range of fields. Some current enquiries into potential differences between print and digital reading (of which e-book reading is a subset) build on studies of reading speed and comprehension, and consider immersion largely from a perspective of minimising barriers such as physical demands imposed by an interface (e.g. eye strain from backlit screens or delays in transfer between pages) or cognitive demands imposed by an interface (e.g. keeping track of one’s place in a text presented on a scrolling page, or managing non-intuitive navigation) or by the text itself (e.g. hyperlinks, enhanced text features such as sound or embedded video, Amazon features options such as popular highlights or X-ray, etc.). These often examine e-book reading in terms of general internet use, with its preponderance of factual and short-form information and material framed as ‘journalism’ rather than ‘books’. Others draw on studies of narrative engagement, considering e-books in terms of stories told via film, television, text, and, more recently, interactive media. This perspective groups many forms of non-fiction with novels and short fiction, approaching story as ‘a mental representation…not tied to any particular medium and…independent of the distinction between fiction and non-fiction’.130 This grouping excludes many examples of e-books, including non-narrative poetry, many forms of reference, and some books under a general ‘non-fiction’ umbrella (though the role of narrative in books such as academic monographs is a matter of debate).

Hou, drawing on her own past work on gaming and on Wittmer and Singer’s work on virtual environments,131 defines immersion as ‘a sense of engagement or a sense of losing oneself in an environment’.132 Busselle and Bilandzic also evoke the sense of being lost in an environment, but theirs is ‘transportation into a story world’, building not on human–computer interaction theory but media, film, and literary studies and ‘the literature on narrative experiences’ (following theorists such as Green and Brock) and connecting explicitly with Csikszentmihalyi’s conception of flow as ‘a complete focus on an activity accompanied by a loss of conscious awareness of oneself and one’s surroundings’.133 For all, achieving the desired state requires not gain but loss: a situation where the reader may ‘lose track of time, fail to observe events going on around them’,134 to be temporarily free of self-awareness and rid of unrelated thoughts. Scholars also order the terms differently, with some, like Hou, describing engagement as a component of immersion, and others, like Busselle, Bilandzic, and Green, describing immersion as a component of engagement. Pleasure is described as an ‘outcome’ of engagement,135 and not necessarily an important outcome.

Unlike empirical studies of reading comprehension and speed in print versus on screen, which are numerous and broadly in agreement,136 empirical studies of print versus screen reading in terms of immersion or engagement are recent and comparatively few.137 (It is also important to note that while any study finding no difference between screen and print reading in terms of immersion would be very valuable, negative results are not always published or reported widely.) The studies that do exist can offer contradictory conclusions regarding the meaning of their results.