1 A Cleavage Perspective on Contemporary Politics

Is contemporary politics shaped by fundamental social divisions, or by the extraordinary skills of politicians such as Boris Johnson, Marine Le Pen, or Emanuel Macron, who creatively unite heterogeneous electoral coalitions based on the issues of the day, galvanized by populist or emotional appeals? Interpretations of how and why electoral landscapes in Western Europe have transformed over the past decades have come to diverge widely. Emphasizing the role of party agency and strategy, one perspective sees new parties’ issue-based challenges to the dominant position of mainstream parties as evidence of dissolving links between voters and parties and of growing party system fragmentation (e.g., Reference Franklin, Mark Franklin, Mackie and Henry ValenFranklin 1992; Reference Green-PedersenGreen-Pedersen 2007, Reference Green-Pedersen2019; Reference Vries, Catherine and HoboltDe Vries and Hobolt 2020). On the other hand, researchers working in the cleavage tradition and comparative political economy scholars alike highlight the role of long-term structural changes of the economy and society at large that give rise to fundamentally new conflicts across advanced democracies (e.g., Reference Inglehart and FlanaganInglehart 1984; Reference KitscheltKitschelt 1994; Reference Kriesi, Grande and LachatKriesi et al. 2008; Reference BornschierBornschier 2010; Reference Beramendi, Häusermann, Kitschelt and KriesiBeramendi et al. 2015; Reference Häusermann, Kriesi, Beramendi, Häusermann, Kitschelt and KriesiHäusermann and Kriesi 2015; Reference Hooghe and MarksHooghe and Marks 2018; Reference HallHall 2020; Reference Gethin, Martínez-Toledano and PikettyGethin, Martínez-Toledano, and Piketty 2021; Reference Kitschelt and RehmKitschelt and Rehm 2023; Reference Häusermann and KitscheltHäusermann and Kitschelt 2024).

The former perspective paints a fluid, fragmented, more volatile picture of “dealigned” contemporary voters, to whom political actors can strategically and voluntaristically appeal by means of issues or identities (Reference Achen and BartelsAchen and Bartels 2016; Reference Vries, Catherine and HoboltDe Vries and Hobolt 2020). The latter emphasizes patterns of realignment, implying a certain inertia and predictability of twenty-first-century politics that remains socio-structurally embedded. Although concerned with the same empirical reality, these strands of literature have to some extent been talking past each other. Indeed, that politics remains anchored in social divisions does not imply that Boris Johnson, Marine Le Pen, or Emanuel Macron do not matter, but rather, that their leeway in rallying coalitions of social groups is limited by the extent to which these groups share fundamental conceptions of who they are and what they want. In this Element, we present an account that reconciles the view that the structural roots of party systems in society incite stability, and that of an ever-increasing role of political entrepreneurship, which induces change.

This section of the Element lays out our overarching argument. We follow the idea of a cleavage reflecting a durable type of conflict in which a social divide is reflected in antagonistic group identities, and finds expression in a struggle over policies.Footnote 1 We advance the idea that focusing on collective identities as mediators between social structure and political action allows us to make sense of the apparent contradiction that party systems have become more volatile and fragmented, while at the same time remaining anchored in fundamental social divisions. A key to understanding how social structure continues to shape voter alignments and party competition is to think about party systems in terms of ideological blocks, rather than individual parties. While the fortunes of single parties depend ever more on issue emphasis, candidate image, and within-block rivalry, voters seldom switch between ideological party blocks. Focusing on alignments between social groups and ideological party blocks reveals degrees of stability and similarities across contexts that observers focused on fluidity and fragmentation fail to acknowledge.

But this view poses a challenge to established theories of partisanship: How do ideological party blocks rally specific constituencies, if they no longer encapsulate voters based in the dense partisan networks characteristic of the age of the traditional class and religious cleavages? In this Element, we focus on the crystallization of a “second dimension” of party competition that we label the universalism–particularism divide. We are interested in how durable links between social constituencies and party blocks emerge along this divide. While parties in the 1950s and 1960s routinely appealed to social groups in terms of their socio-structural ascription – think of “the working-class” or “Catholics” – contemporary categories used to accurately describe social structure in political sociology and political economy (such as “routine manual workers,” “sociocultural professionals,” or “non-college-educated”) have become increasingly divorced from the appeals political parties use to mobilize these groups. The puzzle, then, is how class, education, or the ramifications of social status – that continue to shape party choice, as a vast literature demonstrates – translate into political alignments.

To shed light on these processes, we introduce two conceptual innovations. One is the role of group identities as the intermediate level connecting social structure and the organizational expression of cleavages. The second is to study alignments between identity-laden social groups and ideological blocks, rather than individual parties. This allows us to disentangle the increase in competition that results from the eroding grip of party organizations on voters from persistent regularities that structure voter alignments across countries and over time. Despite variation resulting from party strategy, we find that party systems are shaped by common divisions in social structure, and that similar group identities account for their translation into broader political alignments.

1.1 Electoral Realignment or Issue Entrepreneurship?

The debate on whether we have been witnessing dealignment and the end of an era in which politics was shaped by fundamental social divisions, or whether processes of realignment between social groups and parties create new cleavages is far from new (e.g., Reference Dalton, Scott, Flanagan and BeckDalton, Flanagan, and Beck 1984; Reference Inglehart and FlanaganInglehart 1984). There is abundant evidence that the traditional class and religious cleavages have weakened dramatically (e.g., Reference Rose and McAllisterRose and McAllister 1986; Reference Franklin, Mackie and ValenFranklin et al. 1992; Reference Kriesi, Grande and LachatKriesi et al. 2008; Reference DassonnevilleDassonneville 2022). There is less of a consensus on how to characterize the post-Lipset–Rokkan age (Reference Lipset, Rokkan, Lipset and RokkanLipset and Rokkan 1967), especially after the rise of populism. Have the waning of classic cleavages, the weakening of the associated group identities, and increasing cross-pressures faced by voters in complex societies given way to a more individualized and volatile form of politics that places issues at the center of politics (Reference Green-PedersenGreen-Pedersen 2007; Reference Spoon and KlüverSpoon and Klüver 2019, Reference Spoon and Klüver2020; Reference DassonnevilleDassonneville 2022), and that offers substantial leeway to populist anti-establishment messages of “issue entrepreneurs” (Reference Vries, Catherine and HoboltDe Vries and Hobolt 2020)? Likewise, the literature on populism suggests that anti-establishment appeals can unite seemingly diverse coalitions of voters who have little more in common than the rejection of the political establishment (e.g., Reference Hawkins, Carlin and KaltwasserHawkins et al. 2018; for discussions, see Reference KriesiKriesi 2014; Reference BornschierBornschier 2017). In a similar vein, influential accounts portray contemporary polarization as detached from social reality and substantive policy preferences. Instead, Reference Achen and BartelsAchen and Bartels (2016) suggest that polarization reflects the effects of politics or partisanship itself (see also Reference Iversen and SoskiceIyengar et al. 2019; Reference Gidron, Adams and HorneGidron, Adams, and Horne 2020; Reference Hobolt, Leeper and TilleyHobolt, Leeper, and Tilley 2021; Reference ReiljanReiljan 2020).

The diagnosis of increasing fragmentation and instability runs counter to the realignment perspective.Footnote 2 This strand of research suggested early on that value change, educational expansion, and economic modernization are reconfiguring the links between voters and parties, rather than disrupting them (Reference Dalton, Scott, Flanagan and BeckDalton, Flanagan, and Beck 1984; Reference Inglehart and FlanaganInglehart 1984; Reference KitscheltKitschelt 1994; Reference Kitschelt and McGannKitschelt and McGann 1995; Reference KriesiKriesi 1998).Footnote 3 In other words, voting behavior and party preferences are still strongly and stably structured by voters’ position in the social structure, but the social groups that are key to voter alignments have changed, and they relate to different parties. Although there tends to be disagreement as to the exact structural basis of the resulting antagonism (Reference Bornschier and RydgrenBornschier 2018), the basic contours of the political divide that results from these social divisions are less disputed. In this Element, we adopt a broad conception of the relevant structural transformations of advanced capitalist democracies, which highlights not only educational expansion and occupational change but also the feminization of labor markets, concentration of high value-added economic activity in cities, as well as the multifaceted process of globalization and supranational integration (Reference BartoliniBartolini 2005a; Reference Kriesi, Grande and LachatKriesi et al. 2008; Reference Kitschelt and RehmKitschelt and Rehm 2014; Reference DaltonDalton 2018; Reference Hooghe and MarksHooghe and Marks 2018; Reference Oesch and RennwaldOesch and Rennwald 2018; Helbling and Jungkunz 2019; Reference De Wilde, Koopmans, Merkel, Strijbis and Zürnde Wilde et al. 2019; Reference Steiner, Mader and SchoenSteiner, Mader, and Schoen 2024). Our analysis will focus on Western Europe, where these transformations toward emerging knowledge economies are most advanced, and which constitutes the region most extensively studied from a cleavage perspective. Although broadly similar dimensions of conflict structure party competition in East-Central Europe, their roots in social structure are likely to be different, given differences in the underlying macro-social processes (see Section 3). Our realignment perspective in electoral sociology concurs with research in comparative political economy showing that class, educational background, and the relative position of social groups in the knowledge economy continue to shape individual preferences and policy outcomes, though in new ways (e.g., Reference Esping-Andersen, Kitschelt, Lange, Marks and StephensEsping-Andersen 1999; Reference RuedaRueda 2005; Reference Beramendi, Häusermann, Kitschelt and KriesiBeramendi et al. 2015; Reference Dancygier, Walter, Beramendi, Häusermann and KitscheltDancygier and Walter 2015; Reference Häusermann, Kemmerling and RuedaHäusermann, Kemmerling, and Rueda 2020; Reference Iversen and SoskiceIversen and Soskice 2019). Finally, the recent literature ever more strongly suggests that subjective social status and cultural worldviews work together in shaping voting behavior (Reference Noam and HallGidron and Hall 2017; Reference Burgoon, van Noort, Rooduijn and UnderhillBurgoon et al. 2019; Reference BoletBolet 2020; Reference Carella and FordCarella and Ford 2020; Reference Engler and WeisstannerEngler and Weisstanner 2021; Reference HallHall 2020; Reference Abou-Chadi and HixAbou-Chadi and Hix 2021; Reference Macarena and van DitmarsAres and Ditmars 2023; Reference Kurer and Van StaalduinenKurer and Staalduinen 2022). As we discuss in more detail in Section 3, these different strands of the literature concur in suggesting that, as structural developments change the composition of society, they benefit some groups more than others, providing political opportunities for party mobilization.

The literature identifies several waves through which the dimension of party competition resulting from these structural transformations gained political traction, with the New Social Movements of the 1970s and 1980s finding expression in the emergence of the New Left and Green party family (Reference KitscheltKitschelt 1988, Reference Kitschelt1994; Reference KriesiKriesi 1989, Reference Kriesi1998, Reference Kriesi, Kitschelt, Lange, Marks and Stephens1999), followed by a countermobilization on the part of the Far Right (Reference IgnaziIgnazi 1992; Reference MinkenbergMinkenberg 2000; Reference BornschierBornschier 2010; Reference Häusermann, Kriesi, Beramendi, Häusermann, Kitschelt and KriesiHäusermann and Kriesi 2015). Leaving aside more fine-grained distinctions, we use the term “Far Right” as an umbrella term to encompass parties that have been referred to as “Radical Right,” “Populist Radical Right,” and “Extreme Right” based on their distinctive programmatic position regarding socioculturally traditionalist, nativist, and authoritarian stances (Reference GolderGolder 2016, Reference PirroPirro 2023). Similarly, we use the term “New Left” to denote parties that combine progressive stances on both economic-distributive and sociocultural policies. Hence, the New Left can encompass radical left, green, left-libertarian or social democratic parties (Reference Häusermann and KitscheltHäusermann and Kitschelt 2024).

We conceive the conflict resulting from the sequential mobilization of the New Left and the Far Right as opposing universalistic and particularistic values, as well as their corresponding conceptions of community. The adoption of these labels reflects the gradual broadening of the issues and struggles associated with the new cleavage: Originally conceived as an antagonism between materialism and post-materialism or “new” and “old” political issues and styles (Reference Inglehart and FlanaganInglehart 1984), the political expression of the new cleavage has subsequently been described as opposing libertarian and authoritarian values (Reference KitscheltKitschelt 1994), or, with an emphasis on differing conceptions of community, as libertarian-universalistic versus traditionalist-communitarian (Reference BornschierBornschier 2010), or cosmopolitanism-communitarianism (Reference De Wilde, Koopmans, Merkel, Strijbis and Zürnde Wilde et al. 2019). The integration-demarcation label, on the other hand, explicitly highlighted the transnational component of the divide, driven by the weakening of nation-states by supranational integration (Reference BartoliniBartolini 2005a) and the multifaceted process of globalization (Reference Kriesi, Grande and LachatKriesi et al. 2008), resulting in an encompassing transnational cleavage expressed in terms of GAL-TAN (Reference Hooghe and MarksHooghe and Marks 2018). More recently, it has become evident that the “second dimension” structuring party competition in knowledge economies encompasses distributive conflicts as well (see, for example, Reference Beramendi, Häusermann, Kitschelt and KriesiBeramendi et al. 2015; Reference AttewellAttewell 2021: 20; Reference Enggist and PinggeraEnggist and Pinggera 2021; Reference Häusermann, Abou-Chadi and BürgisserHäusermann et al. 2022a; Reference Philip and BusemeyerRathgeb and Busemeyer 2022; Reference ZollingerZollinger 2022). We refer to the universalism–particularistic conflict to reflect the value-based as well as material foundations of the new cleavage.

1.2 Changes in Party Appeals and Organization

Despite providing robust evidence on persistent links between socio-structural groups and political parties, the realignment perspective leaves us with a puzzle: How are the links between social structure and political parties fostered and perpetuated in a world in which parties’ ideological appeals address broad segments of the electorate, and where party organizations no longer encapsulate specific classes or groups? Indeed, those postulating the emergence of new cleavages have tended to ignore the important literature analyzing how the organization of parties has evolved, putting in evidence a dramatic erosion of parties’ links to their core constituencies (Reference Katz and MairKatz and Mair 1994; Reference Poguntke, Luther and Müller-RommelPoguntke 2002; Reference Katz and MairKatz and Mair 2018; Reference IgnaziIgnazi 2020). This development is mirrored in a trend of declining party identification (Reference Dalton and WattenbergDalton and Wattenberg 2002). Not surprisingly, then, aggregate party system volatility has been on the rise (e.g., Reference Dassonneville and HoogheDassonneville and Hooghe 2017; Reference DassonnevilleDassonneville 2022), in part due to the more frequent emergence of completely new parties (Reference Emanuele and ChiaramonteEmanuele and Chiaramonte 2018).

Reference Katz and MairKatz and Mair (2018: 14–15) plausibly argue that parties have evolved from being the political expression of social groups to becoming brokers that build coalitions between social groups on ideological grounds. These changes imply their declining ability to encapsulate voters in the way they did in the age of Reference Lipset, Rokkan, Lipset and RokkanLipset and Rokkan’s (1967) classical cleavages. Historically, close ties between parties and trade unions, the church, and related social clubs had embedded voters in political networks that linked identities and organizations (Reference Gingrich and LynchGingrich and Lynch 2019). In step with this trend, the strategic action of party leaders has gained more weight (Reference Garzia and De AngelisGarzia, Ferreira da Silva, and De Angelis 2022), although the extent to which this has occurred is debated (Reference Poguntke and WebbPoguntke and Webb 2005; Reference Kriesi, Grande and DolezalKriesi et al. 2012; Reference Marino, Martocchia Diodati and VerzichelliMarino, Martocchia Diodati, and Verzichelli 2022). Recent scholarship on issue competition and political entrepreneurs interprets the ability of new actors to enter party competition as (indirect) evidence that voters no longer base their vote choice on stable cleavage lines (e.g., Reference Green-PedersenGreen-Pedersen 2019; Reference Hobolt, Leeper and TilleyHobolt, Leeper, and Tilley 2021).

Relatedly, a dynamically expanding strand of research studying how parties use group appeals and how they combine them with policy appeals also tends to adopt a more short-term strategic perspective, focusing on individual campaigns, on appeals to voters beyond parties’ core electorates, on valence politics, and typically on mentions of narrowly defined sociodemographic groups (such as “employees,” “the highly educated,” or “women”) rather than on the emergence of long-term party–group relations or on the political construction of new forms of collective consciousness. This includes research on identity frames, which can be viewed as explicit efforts to cast grievances and issues in terms of in-groups and out-groups (an example is the discussion of populist identity frames in Reference Bos, Schemer and CorbuBos et al. 2020). Over time, such strategies might cumulatively contribute to the formation of “groups” in the more strictly political-sociological sense encompassing collective mobilization – and this is how this work connects to our argument (see also Reference Stuckelberger and TreschStuckelberger and Tresch 2022). However, this perspective is not per se at the core of the burgeoning literature on the strategic use of group appeals (e.g., Reference Robison, Stubager, Thau and TilleyRobison et al. 2021; Reference HuberHuber 2022).

By contrast, we suggest that a focus on the role of social identities in connecting social structure and partisan alignments can reconcile the seemingly contradictory findings between the long-term realigned voter–party links and an increased role of short-term party agency. To understand the success of specific group appeals used by political parties, we need to understand how voters think of themselves and of their group belongings in relation to others. We contend that appeals only resonate with individuals when they fall on “fertile soil,” that is, when individuals share a collective identity, or at least frameworks of understanding and worldviews that can provide the basis for one. In that sense, studying the social structuration of collective group identities is a precondition for understanding the differential effects of politicians’ use of appeals.

1.3 The Argument: The Role of Group Identities and Ideological Party Blocks

Two contributions of this Element help us make sense of the puzzling coincidence of realignment and fragmentation in contemporary party politics. First, building and expanding on classical cleavage approaches, we suggest that social identities are important to understanding how party systems are rooted in social structure. We commonly use the concept of identities to describe who we are and what is important to us. The degree to which social groups share such conceptions shapes the extent to which the framing of contemporary conflicts by political parties resonates with them. Second, the fact that allegiances to individual parties and their organizations have eroded, and the resulting increase in competition, implies that we should find more regularities across space and time if we focus on ideological blocks, rather than individual parties. In what follows, we begin by elaborating on the first contribution of our Element. Afterward, we explain the analytical leverage we gain by distinguishing between party competition within and across ideological blocks.

1.3.1 Group Identities and Cleavage Formation

The importance of social identities is implicitly acknowledged in classical cleavage accounts (Reference Lipset, Rokkan, Lipset and RokkanLipset and Rokkan 1967; Reference Bartolini and MairBartolini and Mair 1990; Reference WeakliemWeakliem 1993; Reference Knutsen, Scarbrough, Jan and ScarbroughKnutsen and Scarbrough 1995; Reference BartoliniBartolini 2005b). Yet those who insist that cleavages continue to matter have not devoted much attention to answering the question of what constitutes the “glue” linking social groups and political parties. While we have learned a lot about the socio-structural groups underlying the universalism–particularism divide, as well as on the discourse of the political actors mobilizing it,Footnote 4 the link between structure and consciousness is far from evident. This is of course an idea as old as the social sciences themselves: a “class in itself” is not yet a “class for itself’ (cf. Reference MarxMarx 1937 [1852], 192), and “categories of analysis” (e.g., based on socio-structural conditions) are potentially far from being “categories of practice” (through which people experience group belonging) (Reference BourdieuBourdieu 1985).

There are also specific reasons for focusing on collective identities when it comes to the universalism–particularism cleavage. We argue that a focus on group identities can help us make sense of some particularities in the emergence of this cleavage. In the absence of a clear-cut link between political discourse and the markers of socio-structural position we use to describe these groups, the link between the two still represents something of a black box. This is particularly true for the (counterintuitive) working-class realignment in favor of the Far Right (see, for example, Reference RydgrenRydgren 2007, the contributions in Reference RydgrenRydgren 2013, and Reference Evans and TilleyEvans and Tilley 2011), as well as with respect to recent work that relates subjective structural position, such as status anxiety (e.g., Reference CramerCramer 2016; Reference GestGest 2016; Reference HochschildHochschild 2016; Reference Noam and HallGidron and Hall 2017; Reference FitzgeraldFitzgerald 2018; Reference BoletBolet 2020), relative economic deprivation (e.g., Reference Rooduijn and BurgoonRooduijn and Burgoon 2018; Reference KurerKurer 2020; Reference Kurer and Van StaalduinenKurer and Staalduinen 2022; Reference ZollingerBreyer, Palmtag, and Zollinger 2023), or the perception of economic and social opportunities (Reference ZollingerHäusermann, Kurer, and Zollinger 2023) to Far Right support. Why exactly do such feelings and perceptions of grievance and vulnerability translate into support for the Far Right, rather than for other parties that cater to economic vulnerability more directly? To understand why culturally connoted appeals resonate with economically defined groups, the next section draws centrally on psychological and sociological approaches that highlight the importance of positive group identifications for individuals (Reference Bornschier, Häusermann, Zollinger and ColomboBornschier et al. 2021; Reference ZollingerZollinger 2022). This accounts for the propensity of the “losers” of economic and social change to seek identification based on categories that correspond only loosely to their objective social position.

The construction of a positive self-image is more self-evident for the relative “winners” of the social changes of the past decades. Indeed, in the initial mobilization of the New Social Movements of the 1970s and 1980s, personal and group identity in the quest for the recognition of difference in terms of gender, sexual orientation, as well as the free choice of lifestyles were closely linked. In a process corresponding to what Reference Snow, McAdam, Stryker, Owens and WhiteSnow and McAdam (2000) have called the “general diffusion” of movement identities, solidarity with the drivers of protest then expanded within broader universalistically minded sectors of society. As movement activists flocked into the emerging Green parties, bottom-up and top-down processes of mobilization and identity construction were intimately related.Footnote 5 But explaining the inclination of parts of the middle class to vote for the New Left is by no means trivial either. While the literature has identified education and work logic as determinants of universalism (Reference KriesiKriesi 1998; Reference OeschOesch 2006a; Reference Kitschelt and RehmKitschelt and Rehm 2014), an ethnographic approach reveals how these groups’ economic preferences are embedded in broader, culturally defined worldviews of deservingness and fairness, as well (Reference WestheuserWestheuser 2021; Reference Damhuis and WestheuserDamhuis and Westheuser 2023).

In a nutshell, then, the key question is how the winners and losers of the social transformations of the past four to five decades see and describe themselves. We believe such a perspective can go a long way in explaining why certain party appeals resonate with specific social groups, while others fail to do so.

1.3.2 The Role of Agency

Creating and reproducing these nonevident links between social groups and parties obviously assigns a nontrivial role to political agency.Footnote 6 We believe that the level of social identities – the intermediate level in Reference Bartolini and MairBartolini and Mair’s (1990) much-noted threefold conception of cleavages – is a good place to study agency.Footnote 7 It is here that the self-definitions of social groups intersect with the appeals by political parties to give meaning to grievances. In grasping this link, we can draw on the literature on social movements that highlights how collective action frames point to injustices and combine them with a definition of the group or social category in question (Reference Gamson, Aldon and MuellerGamson 1992; Reference Klandermans and JudithKlandermans 2001).Footnote 8 Reference Klandermans and JudithKlandermans (2001) theorizes two processes that translate the “raw material” of a cleavage into collective action. On the one hand, meaning is constructed bottom-up at the interface between networks of personal interaction and media-based public discourse. On the other hand, these interpretations are reinforced during campaigns, where social actors undertake deliberate attempts to persuade voters and where they stake out who the group’s antagonists are. The latter process is crucial because the social movement literature as well as the more classical sociological literature both highlight the group-binding effects of conflict (Reference CoserCoser 1956; Reference StrykerStryker 1980; Reference MarksMarks 1989; Reference Gamson, Aldon and MuellerGamson 1992). Combined, these two processes result in what Reference Snow, Burke Rochford, Worden and BenfordSnow et al. (1986) refer to as “frame alignment,” meaning in our case that individuals’ and parties’ interpretations of grievances come to overlap. Incorporating the idea that party appeals resonate with the way groups would describe themselves also helps us understand how Far Right parties succeed in mobilizing diverse structural groups (as emphasized in the recent literature on different logics of Far Right voting, for example, Reference DamhuisDamhuis 2020; Reference Harteveld, Van Der Brug, De Lange and Van Der MeerHarteveld et al. 2022).

Both the bottom-up processes in which group identities are constructed, as well as the role of political agency in reinforcing and nourishing these identities, lead us to expect fundamental similarities between countries:

(a) Similarities in Terms of the Raw Materials for a New Cleavage. We start here from the insight that each individual holds multiple identities with the potential of being politically relevant. Building on Reference Stryker, Stryker, Owens and WhiteStryker (2000), as well as the classical literature on cross-cutting cleavages (e.g., Reference LijphartLijphart 1979; Reference Rokkan, Flora, Kuhnle and UrwinRokkan 1999), the relative salience of these identities should determine which of them will shape political alignments. Identity salience increases, according to Reference StrykerStryker (1980), as individuals interact with members of the same group. Because our personal interactions are patterned by social structural position – chiefly in terms of class, education, and urban-rural residence – identity salience is not entirely voluntaristic. Instead, it is biased toward those identities that are most strongly reinforced at the workplace and in everyday life. The resulting expectation is that the grievances resulting from the transition to a knowledge economy will lead to similar identity potentials across the set of advanced democracies that we study.

(b) Convergence of Mobilization Frames. Framing constitutes a creative, collective effort at meaning construction. It “draw[s] on the cultural stock of images of what is an injustice, of what is a violation of what ought to be” (Reference Zald, McAdam, McCarthy and ZaldZald 1996: 266). At the anti-universalistic pole of the cleavage, the Far Right has converged on a particularistic frame that emphasizes the preservation of traditional (national) communities and status hierarchies (e.g., Reference AntonioAntonio 2000; Reference MinkenbergMinkenberg 2000; Reference BetzBetz 2004; Reference BornschierBornschier 2010; Reference Elgenius and RydgrenElgenius and Rydgren 2019). One of the core elements of the Far Right’s ideology is indeed its nostalgic component, as several scholars have highlighted (Reference Betz and JohnsonBetz and Johnson 2004; Reference DuyvendakDuyvendak 2011; Reference Elgenius and RydgrenElgenius and Rydgren 2019, Reference Elgenius and Rydgren2022). This discourse can be expected to resonate strongly with social groups that feel deprived relative to a supposedly better past (e.g., Reference Elchardus and SpruytElchardus and Spruyt 2012; Reference Burgoon, van Noort, Rooduijn and UnderhillBurgoon et al. 2019; Reference Engler and WeisstannerEngler and Weisstanner 2021). Combined with the large literature that has pointed to a fundamental similarity in the competitive spaces in West European party systems (e.g., Reference KitscheltKitschelt 1994; Reference Marks, Hooghe, Nelson and EdwardsMarks et al. 2006; Reference Kriesi, Grande and LachatKriesi et al. 2008; Reference BornschierBornschier 2010; Reference Kriesi, Grande and DolezalKriesi et al. 2012; Reference Hutter and KriesiHutter and Kriesi 2019) this again leads us to expect a fundamental similarity in terms of the group identities underlying the universalism–particularism cleavage.

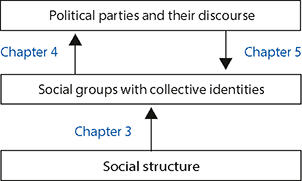

Figure 1 summarizes the discussion so far (also foreshadowing the focus of subsequent sections of this Element). It illustrates how we can think of cleavages becoming consolidated. As party narratives give meaning to existing group boundaries, these politicized identities inform voters’ preferences within specific ideological schemas (also see Reference HuddyHuddy 2001; Reference StubagerStubager 2009). Once formed, they may also shape party politics in lasting ways as mobilization markets are “narrowed” (c.f. Reference MairMair 1997; Reference Rokkan, Flora, Kuhnle and UrwinRokkan 1999) by salient us-versus-them distinctions into which voters are socialized. Put differently, existing interpretations of what conflict is about limit the receptiveness of voters to new political appeals. Hence, even in light of ongoing socio-structural change and party entrepreneurship, collective identity antagonisms generate a certain inertia to party system change, confining the effects of idiosyncratic shocks or individual election campaigns.

Figure 1 Processes of cleavage formation: social closure and political mobilization

An important question concerns the proper level of abstraction to study group identities. Rather than studying broad political identities that are defined by party ideology (e.g., Reference Sartori and StammerSartori 1968; Reference Bartolini and MairBartolini and Mair 1990; Reference Knutsen, Scarbrough, Jan and ScarbroughKnutsen and Scarbrough 1995; Reference MairMair 1997), we suggest focusing on an intermediate level of specificity.Footnote 9 These identities – for example, feeling close to “cosmopolitans,” or to “rural people” – are more specific than the broad political allegiances that cleavage theorists have traditionally focused on. At the same time, the identity categories we develop are sufficiently abstract to study the degree to which group identities antagonize New Left and Far Right voters. We elaborate on the choice of these groups in Section 2.

1.3.3 The Transformation of Party Systems and Ideological Party Blocks

Looking at the process of realignment through the lens of ideological party blocks is central to our approach. If transformations in the structure of society create social groups with a common identity, then these potentials inevitably play out quite differently depending on the specific configuration of the party system in different countries. Combined with our focus on group identities, studying party competition in terms of ideological blocks implies a higher level of abstraction that allows us to discern similar patterns underlying varying political entrepreneurship. It allows us to reconcile the structuralist core of our argument with the ever more apparent leeway that actors enjoy in tapping into and giving coherence to raw and often rather diffuse political potentials. Our contention, then, is that politicians and “issue entrepreneurs” for the most part move within the ideological space without fundamentally altering its basic contours or the group divisions underlying competitive dimensions.

This perspective is very much in line with classical cleavage theory (e.g., Reference Rokkan, Flora, Kuhnle and UrwinRokkan 1999). It is also consistent with individual-level accounts developed by cleavage theorists, who distinguish between volatility comprised of voters crossing cleavage lines from within-block movements (Reference Bartolini and MairBartolini and Mair 1990). While the former indicates electoral change signaling either dealignment or realignment, the latter accounts for struggles within ideological blocks over strategies to achieve goals, the rivalries between leaders, and the disappointments that partisans may experience with respect to their government’s policy record. In this way, cleavage theory has always assigned room for voters to make choices based on nuances in issue positioning and emphasis, the profiles and the charisma of specific candidates, or even economic voting.

We revive the analytical perspective of cleavage formation because it allows us to incorporate two aspects of political agency that are central for our purposes. For one thing, we seek to distinguish (a) country variation that reflects fundamental differences in the timing and the strength of the structural manifestation of the universalism–particularism cleavage from (b) more superficial and situational differences caused simply by the fact that the agents of mobilization differ by country. The prime example of the latter is that the mobilization of the universalistic pole of the new cleavage was spearheaded by Green parties in some countries and their established Social Democratic or Socialist counterparts in others (Reference KitscheltKitschelt 1994; Reference Häusermann and KitscheltHäusermann and Kitschelt 2024). The impact of these differences in the division of labor on the political left on competitive policy spaces has been relatively minor compared to that variation triggered by competition between mainstream Right and Far Right parties over the particularistic potential (Reference Kriesi, Grande and LachatKriesi et al. 2008, Reference Kriesi, Grande and Dolezal2012; Reference BornschierBornschier 2010; Reference Bremer, Schulte-Cloos, Hutter and KriesiBremer and Schulte-Cloos 2019; Reference Jasmine, van Ditmars, Hutter and KriesiLorenzini and van Ditmars 2019). This is also mirrored in the far more extensive literature on strategic competition between the established Right and its Far Right challengers (the literature is too large to quote in full, but see, e.g., Reference IgnaziIgnazi 1992; Reference MeguidMeguid 2008; Reference BornschierBornschier 2012; Reference Abou-Chadi and KrauseAbou-Chadi and Krause 2018; Reference van Spanje and de Graafvan Spanje and de Graaf 2018; Reference Spoon and KlüverSpoon and Klüver 2020; Reference Bale and KaltwasserBale and Rovira Kaltwasser 2021; Reference De JongeDe Jonge 2021).

The higher level of abstraction in studying party competition at the level of ideological blocks also helps us to reconcile the two contrasting developments that have spurred diametrically opposing interpretations of contemporary party competition: First, the rise of instability and fragmentation due to an increasing role of agency, and second, the idea of a realignment suggesting that politics remains anchored in fundamental cleavages. While voters remain committed to broader political block ideologies, their choice set – composed of parties that differ with respect to specific issues or issue emphasis, but that align in their basic cleavage positions (Reference Steenbergen, Hangartner and De VriesSteenbergen, Hangartner, and De Vries 2015; Reference Oskarson, Oscarsson and BoijeOskarson, Oscarsson, and Boije 2016) – expands. There is also evidence that affective polarization transcends the partisan level and divides ideological blocks, rather than just parties (Reference BantelBantel 2023).

Theoretically, based on the discussion in Section 1.1, we would expect the mobilization of the New Left and the Far Right to sequentially introduce a division within the Left and the Right. Since the 1980s, Social Democratic parties have competed with the Greens (and sometimes other challengers) over the support of voters holding universalistic group identities. On the political right, as first manifested in France in the early 1980s, established conservative parties increasingly faced competition from the Far Right in rallying voters that more strongly endorse particularistic group identifications. In the meantime, as the last bastions of resistance against the Far Right challenge are falling, we see this competition throughout Western Europe. Theoretically, we would thus expect the existence of up to four blocks along the universalism–particularism cleavage: The traditional Left and the New Left on the one side of the political spectrum, and the traditional Right and the Far Right on the other.

1.4 Plan of the Element

The next section lays out how we study collective identities theoretically and empirically. It also introduces our main data source of four original online surveys fielded in France, Germany, Switzerland, and the UK. In conceptual terms, the section develops a list of seventeen social groups that we use to measure people’s social identities and identifies the three ideological party blocks our analysis is based on using a Gaussian mixture model in combination with the 2019 Chapel Hill Expert Survey. Drawing on an analysis of volatility, we also substantiate the appropriateness of focusing on these ideological party blocks, rather than individual parties. While Section 2 outlines our overarching approach, subsequent sections include discussions of theory and empirics more specific to the analyses they present.

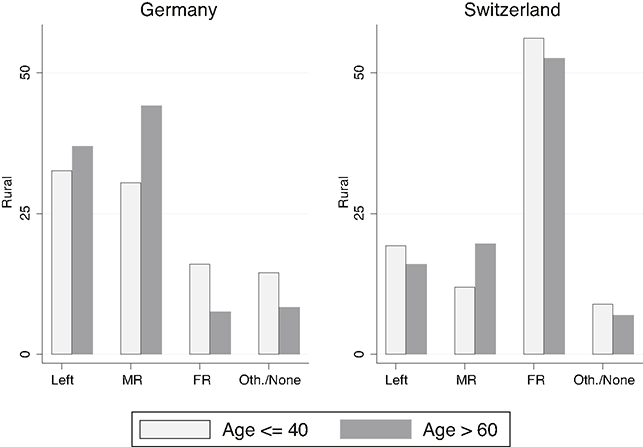

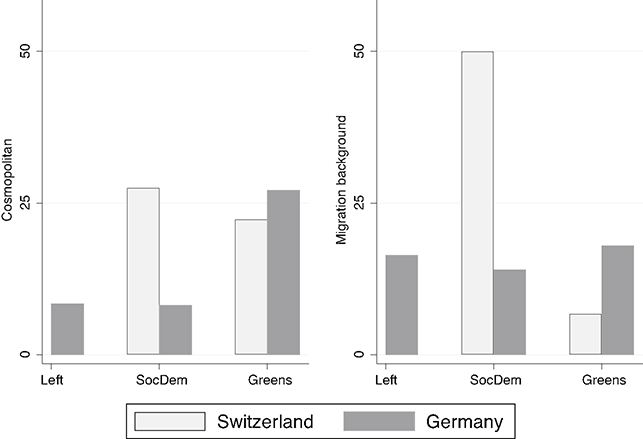

Section 3 deals with the link between social structure and collective identities. It explains why the emergence of the knowledge economy leads to education, class, and urban-rural residence constituting key socio-structural foundations of group identities. Empirically, it establishes two main insights: first, the “objective” socio-structural characteristics of voters relate consistently to their corresponding “subjective” group. Second, more culturally connoted group identities also have clearly identifiable structural roots. The section then shows how education in particular contributes to cleavage formation via culturally connoted identities.

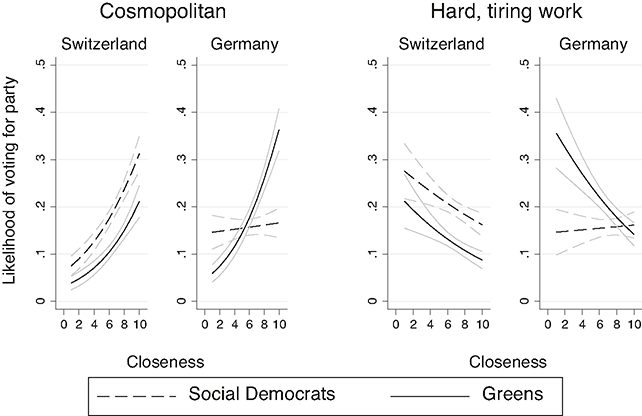

Having demonstrated how identities consistently relate to different socio-structural groups, Section 4 focuses on how these identities are politicized, that is, which of them structure political antagonisms, especially between voters of the New Left and the Far Right. We thus switch perspective by looking at group identities through the lens of party electorates. We identify the most important in-groups and out-groups of the different electorates and show that these in-groups and out-groups are important predictors of vote choice. We also consider to which degree individual group identities coalesce into broader social divisions.

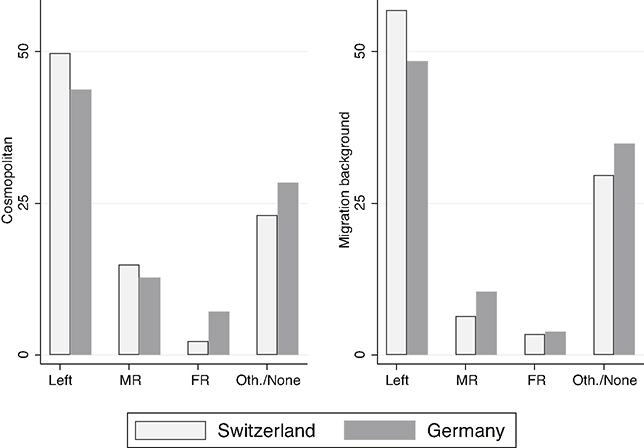

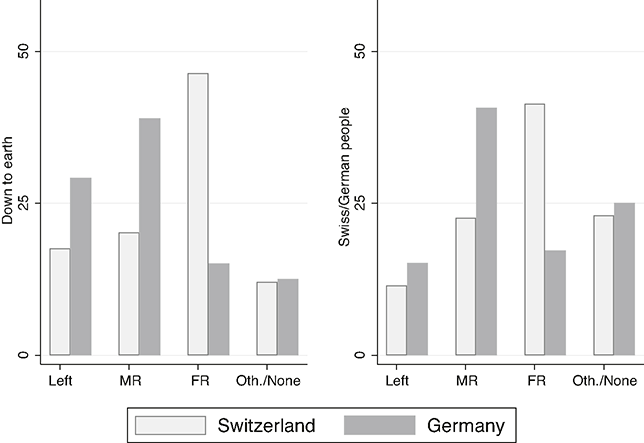

Section 5 focuses on the role of political parties in activating the identity potentials that emerge through processes of social closure and in translating them into the political realm. When a cleavage is fully mobilized, parties are perceived as representing one side of that cleavage even by voters who support other parties. We therefore study whether respondents consistently link groups to specific political parties. Moreover, in this section, we explicitly pick up the cross-country dimension. In particular, we find that voters in early realigned Switzerland have more congealed perceptions of the link between certain identities and parties than voters in Germany, where this cleavage was only politicized more recently.

Based on the findings of the three empirical sections, the final section scrutinizes the evidence for the existence of the new cleavage relative to alternative interpretations of European politics. It also discusses the implications of our findings for cleavage theory and how that theory helps us make sense of how grievances are translated into electoral politics.

2 How We Study Collective Identities

The introductory section outlined a tension between two strands of literature: One that focuses on fundamental structural transformations of society in increasingly knowledge-based economies, and another focusing on the increasing fragmentation and instability of electoral landscapes. We propose that collective identities make it possible to detect and map fundamental, systematic, and potentially durable transformations of the electoral space beneath fragmentation and seeming instability. Studying identities, we argue, is key to assessing to what extent the disruption we see in European party systems obscures and is maybe even a symptom of changing cleavage structures. Concretely, we address the question of whether a new cleavage complete with structural, political, and identity elements is emerging from the upheaval that European party systems have seen in the past decades. We will argue and show that a new universalism–particularism cleavage is indeed forming across various European countries.

This section lays out how we go about substantiating this claim, theoretically and empirically. We first develop our argument, highlighting why identities matter from the perspective of cleavage theory, and why a lack of attention to them represents a gap in existing work on changing electoral landscapes. We also integrate insights from sociology and social psychology that deepen our understanding of why identities help make sense of people’s political preferences. Second, we describe our empirical, comparative survey-based approach for studying identities and cleavage formation.

2.1 Theoretical Argument

2.1.1 The Relevance of Cleavage Formation in the Knowledge Economy

The political landscapes of Western Europe are widely considered to have been historically shaped by a small number of key conflicts, triggered by the “critical junctures” of the national and industrial revolutions. These changed the fabric of society and became durably articulated by parties and related organizations, such as unions, churches, or associated social clubs. Building on Reference Lipset, Rokkan, Lipset and RokkanLipset and Rokkan’s (1967) seminal work, traditional cleavage theory expanded on the role that collective identities played in this translation of structural disruption into political competition: A sense of shared identity is central to collective action, and it mediates the nonobvious step from objective group belonging to political mobilization. Strong existing identities, cemented by embeddedness in social organizations, also constrain new forms of political mobilization. They partly stabilize existing conflicts even when structural conditions change (e.g., where Catholic workers were historically unavailable for mobilization as members of the working class) (Reference Rokkan, Flora, Kuhnle and UrwinRokkan 1999; Reference BartoliniBartolini 2000; Reference BornschierBornschier 2010). For these reasons, an identity component or “normative element” became an established part of the most influential definition of a “cleavage” as comprised of structural, political, as well as identity divides.

Over the past decades, researchers have studied how the “old” cleavage structures have profoundly loosened, focusing on both structural and political change, but largely neglecting the question of how voters perceive their place in this transformed landscape. We place identities center stage in the study of contemporary politics. Taking traditional cleavage theory as a starting point, we conceptualize collective identities as located at an intermediary level between structure and politics (Reference Bartolini and MairBartolini and Mair 1990; Reference BartoliniBartolini 2005b; Reference BornschierBornschier 2010; Reference Bornschier, Häusermann, Zollinger and ColomboBornschier et al. 2021; Reference ZollingerZollinger 2024). Cleavages become consolidated at the identity level as conflict potentials arising from social structure become activated by political actors.

Much existing work points to new potentials for conflict emerging from the structural shift from an industrial to a knowledge society, which we treat as similarly disruptive as the Lipset–Rokkanian “revolutionary” junctures. While the cleavages which characterized West European party systems for decades have lost much of their structuring power, new tensions have arisen from rapid educational expansion, occupational change, feminization of labour markets, concentration of high value-added economic activity in cities, and exposure to the multifaceted process of globalization (Reference KitscheltKitschelt 1994; Reference OeschOesch 2006a; Reference Kriesi, Grande and LachatKriesi et al. 2008; Reference StubagerStubager 2008; Reference Bornschier and RydgrenBornschier 2018; Reference Hooghe and MarksHooghe and Marks 2018; Reference Iversen and SoskiceIversen and Soskice 2019; Reference Garritzmann, Häusermann and PalierGarritzmann, Häusermann, and Palier 2022a; Reference HallHall 2022). These developments change the composition of society, and they benefit some groups more than others (e.g., the higher educated compared to the lower educated; or workers in knowledge-intensive and creative jobs compared to those in routine work). They do so materially, but also more broadly in terms of status, outlook, or the rise and demise of worldviews and ways of life (Reference CramerCramer 2016; Reference GestGest 2016; Reference HochschildHochschild 2016; Reference Noam and HallGidron and Hall 2017; Reference FitzgeraldFitzgerald 2018; Reference KurerKurer 2020; Reference BoletBolet 2021; Reference Kurer and Van StaalduinenKurer and Van Staalduinen 2022; Reference ZollingerHäusermann, Kurer, and Zollinger 2023).

While the timing, strength, and scope of structurally driven societal change has differed across Western Europe, these countries can today broadly be classified as postindustrial, globally integrated, knowledge-based economies. In other words, the “raw material” for a new cleavage (or cleavages) in terms of structural divides has likely emerged across these contexts. In all these countries, structural transformations of social patterns and norms have raised questions related to cultural liberalism and changing gender roles, immigration and multiculturalism, minority rights, or the boundaries of community. These topics have by now been widely taken up by socially liberal parties (especially the Greens) and nativist parties (especially Far Right, but also established conservative parties).

While some have studied the rise of the Far Right and green/left-libertarian parties from the vantage point of political entrepreneurship, the literature on electoral realignment provides a basis for thinking about them as expressions of a new cleavage. This literature links newly arising issue conflicts to the structural changes previously outlined, tracing the emergence of stable new alignments between voters and parties. By now, most observers of party system change in Western Europe will agree on the emergence of a “second dimension” of politics (clearly distinct from the traditional class cleavage), centered around predominantly sociocultural questions of individual liberties, societal organization, and community boundaries. In mobilizing this conflict, parties of the New Left and the Far Right garner disproportionate support, respectively, among a highly educated “new” middle class versus among lower-educated members of the working and “old” middle class (Reference KitscheltKitschelt 1994; Reference Kriesi, Grande and LachatKriesi et al. 2008; Reference BornschierBornschier 2010; Reference Gingrich and HäusermannGingrich and Häusermann 2015; Reference Häusermann, Kriesi, Beramendi, Häusermann, Kitschelt and KriesiHäusermann and Kriesi 2015; Reference Hooghe and MarksHooghe and Marks 2018; Reference Oesch and RennwaldOesch and Rennwald 2018; Reference De Wilde, Koopmans, Merkel, Strijbis and ZürnDe Wilde et al. 2019).

There is cross-country variation regarding exactly how the structural “raw material” has been mobilized, issues bundled and politicized, and how strongly new conflicts have gained expression within party systems. The literature identifies several waves in which the “universalism–particularism” dimension gained political traction, with the New Social Movements of the 1970s and 1980s finding expression in the emergence of the New Left and Green party family, followed by countermobilization driven by the Far Right (e.g., Reference Häusermann, Kriesi, Beramendi, Häusermann, Kitschelt and KriesiHäusermann and Kriesi 2015). These waves of mobilization and countermobilization have played out somewhat differently across countries: especially the conditions for new party entry are well-known to differ (Reference Vries, Catherine and HoboltDe Vries and Hobolt 2020); established parties on the Left did not equally adopt universalist positions early on (Reference KitscheltKitschelt 1994; Reference Rennwald and EvansRennwald and Evans 2014); Far Right countermobilization varied across countries in terms of strength and timing (Reference CarterCarter 2005; Reference Kriesi, Grande and LachatKriesi et al. 2008;); and varying reactions from mainstream right parties to Far Right mobilization have also impacted the salience of second dimension issues (Reference MeguidMeguid 2008; Reference van Spanjevan Spanje 2010; Reference BornschierBornschier 2012; Reference Abou-Chadi and KrauseAbou-Chadi and Krause 2018;).

We contend that bringing in the identity element is crucial to looking past such country variation, and ultimately to assessing whether a new cleavage is emerging. An identity perspective can shed light on the “stickiness” of new group-party alignments, as well as provide important insights into what motivates voters in terms of their perceptions and worldviews.

2.1.2 Identity and Cleavage Formation in Contexts of Realignment

Conceptualizing collective identities as located on an intermediary level between structure and political agency allows us to avoid structural determinism without viewing social identities as entirely socially constructed. It is especially important to make clear that subjective notions of group belonging need not correspond to the objective (educational, class, etc.) categories with which political scientists typically operate. This point also relates directly to a long-standing debate about whether the drivers of political transformations are primarily “economic” or “cultural” (cf. Reference ManowManow 2018; Reference Norris and InglehartNorris and Inglehart 2019): identities can provide the link from conflicts between (objectively defined) “winners” and “losers” of the knowledge economy to what can (mistakenly, we believe) be taken for “mere” culture wars or identity politics conjured up by political elites. To theorize which types of identity contrasts are likely to inform voters’ worldviews and preferences, complementing cleavage theory with insights from sociological and social psychological work on identities is insightful.

Sociologists in Weberian or Bourdieusian traditions have shown how groups monopolize privileges and resources by constructing “symbolic boundaries” of who belongs and who does not (Reference LamontLamont 2000; Reference Lamont and MolnárLamont and Molnar 2002; Reference Savage, Devine and CunninghamSavage et al. 2013; Reference RidgewayRidgeway 2019; Reference DamhuisDamhuis 2020; Reference WestheuserWestheuser 2021; also see Reference BartoliniBartolini 2005b). Material interests can motivate the drawing of (cultural, moral) in-group and out-group boundaries, but so can the quest for maintaining dignity and status. In this vein, especially ethnographic work in the past years provides key insights into the specific group understandings around which a new cleavage may well crystallize: pride in national or rural communities, identification with hard work, or adherence to traditional, conservative, more patriarchal moral standards of success provide a path to positive identity even for objective “losers” of economic and social change (the lower-educated, routine workers, etc.) (Reference CramerCramer 2016; Reference HochschildHochschild 2016; Reference DamhuisDamhuis 2020; Reference WestheuserWestheuser 2021). By contrast, cultural capital is becoming increasingly associated with the cosmopolitan, urban, culturally diverse lifestyles and consumption patterns of the highly educated middle class (Reference FloridaFlorida 2012; Reference Savage, Devine and CunninghamSavage et al. 2013; Reference Flemmen, Jarness, Rosenlund, Blasius, Lebaron, Roux and SchmitzFlemmen, Jarness, and Rosenlund 2019).

Social psychology further provides rich insights into individual-level psychological motivations of identity formation. Work building on social identity theory documents people’s innate tendency to simplify the social world by categorizing and stereotyping into “us” and “them.” A psychological desire to positively distinguish one’s own group fosters in-group bias and the derogation of out-groups (Reference Henri, Turner, William and WorchelTajfel and Turner 1979; Reference TajfelTajfel 1981; Reference HuddyHuddy 2001; Reference Roccas and BrewerRoccas and Brewer 2002; Reference StubagerStubager 2009; Reference MasonMason 2018; Reference Mason and WronskiMason and Wronski 2018). This aligns, in many ways, with sociological work concerned with the status concept (Reference LamontLamont 2000; Reference ShayoShayo 2009; Reference ZollingerZollinger 2022). Similarly, recent social psychological work that documents identity sorting and reduced “identity complexity” chimes with a notion from cleavage theory (Reference Roccas and BrewerRoccas and Brewer 2002; Reference MasonMason 2018): a lack of cross-cutting identities (e.g., today, if educational, class, and geographical divides align) intensifies identity conflict (Reference Bornschier, Häusermann, Zollinger and ColomboBornschier et al. 2021). This body of work especially highlights the affective component of identity antagonisms, which has recently entered issue-based/spatial accounts of political conflict via the concept of “affective polarization” (Reference Iyengar, Sood and LelkesIyengar, Sood, and Lelkes 2012; Reference Gidron, Adams and HorneGidron, Adams, and Horne 2020; Reference ReiljanReiljan 2020; Reference WagnerWagner 2021; Reference Hobolt, Leeper and TilleyHobolt, Leeper, and Tilley 2021; Reference Hegewald and SchraffHegewald and Schraff 2022).

Integrating these various strands of work results in a model of voting behavior in which cleavage identities mediate between individuals’ socio-structural position and their political behavior. Both in-groups and out-groups are relevant here, as are cognitive and affective aspects of group identification. These subjective self-perceptions correspond imperfectly to objective group belonging, because they serve the social and psychological goals of orientation and a positive self-understanding in a changing world. Identities thus conceptualized provide an entry for studying the “glue” of cleavage formation in the twenty-first-century knowledge economy environment. Comparing against the most pillarized, encapsulated, formally organized manifestations of traditional cleavages, stable and recurring patterns of electoral realignment in today’s fast-paced, individualized, politically volatile societies are somewhat puzzling at first glance. Indeed, the decline in actual partisan identity (not to mention party membership) is a key factor that complicates the study of contemporary cleavages. Our expectation is that studying the intermediary level of identities can reveal regularities and cross-national patterns that are hidden when looking at voting and partisanship alone. We expect voters to have a clearer understanding of the broader political blocks or camps where “people like them” belong (or do not belong) politically. Group identities that clearly link structural divides in the knowledge economy to political options that represent universalism versus particularism would be strongly indicative of a new, fully-fledged cleavage taking shape.

2.2 Empirical Strategy

2.2.1 Survey Design

To study identities associated with a universalism–particularism cleavage, we fielded a bespoke online survey in France, Germany, Switzerland, and the UK. The surveys were implemented by the survey company Bilendi between November 2020 and January 2021. We recruited 2,000 participants each in France and Germany and 3,000 participants each in Switzerland and the UK. In Switzerland, we only recruited participants from the German and French speaking parts. In the UK, we only recruited participants from England, to avoid capturing conflicts over national identity (Scottish, Welsh, etc.) more specific to the UK context. The samples are population-representative in terms of education, age, and gender.

We selected these four countries because they are part of the same historical area of political cleavage formation but are at different stages of electoral realignment. While France and Switzerland are representative of countries that experienced early and strong realignment, Germany and the UK are cases of late and less consolidated realignment (Reference Kriesi, Grande and LachatKriesi et al. 2008; Reference BornschierBornschier 2012). The former two countries saw the early establishment of a strong “particularist” Far Right. Switzerland’s major left parties further jointly represent a particularly extreme articulation of the “universalist” New Left side of a new divide (Reference Rennwald and EvansRennwald and Evans 2014; Reference Bornschier, Häusermann, Zollinger and ColomboBornschier et al. 2021). Meanwhile, the Far Right in Germany made a much later breakthrough (including for institutional and historical reasons), and in the UK, the party system constrained the articulation of new divides in the political arena (although the Brexit referendum seems to have been a substitute and catalyst in this respect, cf. Reference Hobolt, Leeper and TilleyHobolt, Leeper, and Tilley 2021).

Importantly, despite this variation in party system change, the structural transformations expected to generate new identity potentials have occurred in all four countries. The fact that the last bastions of resistance against the Far Right have fallen in most Western European party systems suggests that the space for political agency is limited, certainly in fully preventing the emergence of this divide. The strategic action of established political parties helps explain why Far Right parties were able to break into party systems earlier in places like France, Switzerland, Flanders, and the Netherlands, and much later in Germany, Britain, as well as a parts of Southern Europe. As a result, the electoral realignment of educational groups or classes along the second dimension, shifts of dimension salience, and the association of specific bundles of issues with New Left and Far Right parties is more entrenched in some countries than others (differences we address in Section 5). However, while their political expression may vary somewhat, we expect to see similar identity divides anchored in structural divisions across all four countries.

In the survey, we ask respondents about their sociodemographic characteristics, political attitudes, and party preferences. However, the center piece of the survey are novel questions on group identity (building on Reference Bornschier, Häusermann, Zollinger and ColomboBornschier et al. 2021). We work mainly with a series of closed-ended questions in which we ask respondents about perceived closeness to different social groups (“Of the following groups, how close do you feel towards them? By ‘close’ we mean people who are most like you in terms of their ideas, interests, and feelings.”), on a ten-point scale ranging from “not at all close” to “very close.” We consider this survey item a good starting point to extend research in cleavage theory to encompass group identities. The validation of this measure is discussed extensively in the appendix to Section 2.

2.2.2 Selection and Measurement of Identities

The survey asked about belonging to seventeen specific groups, in randomized order. Our aim was to tap into group categories that are closer to the structural foundations of a new divide according to the literature (education, class, place of residence) and others that are closer to the sociocultural distinctions through which these divides become manifest (e.g., conationals versus cosmopolitans). We also aimed to include both identities theorized to be newly emerging and others that were already associated with traditional cleavages. In selecting group categories and developing the wordings, we drew inspiration from qualitative work (e.g., Reference LamontLamont 2000; Reference SavageSavage 2015; Reference CramerCramer 2016), built on a previous Swiss study (Reference Bornschier, Häusermann, Zollinger and ColomboBornschier et al. 2021), and on results from open-ended survey questions (Reference ZollingerZollinger 2024).

Concretely, the survey asked about the following groups (the distribution of responses is shown in appendix Figure A2.2):

Education: We use three categories, namely, people with a higher education degree, people with medium-level education (vocational training in Germany and Switzerland), and people with lower-level education. Already associated with traditional class divides (Reference BourdieuBourdieu 1984), education has become recognized as the primary structural divide underpinning a new universalism–particularism conflict, especially in knowledge-based economies (Reference StubagerStubager 2008; Reference Kriesi, Grande and LachatKriesi et al. 2008; Reference Iversen and SoskiceIversen and Soskice 2019).

Class: To tap into the traditional vertical class dimension, we asked respondents how close (or distant) they felt to wealthy people and people with humble financial means. Targeting more horizontal class divisions (Reference OeschOesch 2006b; Reference Savage, Devine and CunninghamSavage et al. 2013) as well as work more versus less associated with the knowledge economy, we further asked about people who do hard, tiring work, people who do creative work, and people who work in the social and education sector.

Residence: We asked about closeness to urban and rural people, given the geographical dimension of emerging divides in the knowledge society (Reference CramerCramer 2016; Reference FitzgeraldFitzgerald 2018; Reference MaxwellMaxwell 2019; Reference Iversen and SoskiceIversen and Soskice 2019; Reference PatanaPatana 2022).

National (nativist) identity: The survey asked about closeness to German/Swiss/French/British people and about closeness to people with a migration background. Asking about people with a migration background also allows us to partly tap the ethnic and racial component of divides over diversity in a European context.

Parochialism/communitarianism versus universalism/cosmopolitanism: Here, we asked about cosmopolitans and people who are down-to-earth and rooted to home. We further asked about self-perceived belonging to culturally interested people, given milieu studies that indicate “cultural capital” becoming increasingly linked to cosmopolitan (urban) lifestyles (Reference SavageSavage 2015; Reference Flemmen, Jarness, Rosenlund, Blasius, Lebaron, Roux and SchmitzFlemmen, Jarness, and Rosenlund 2019).

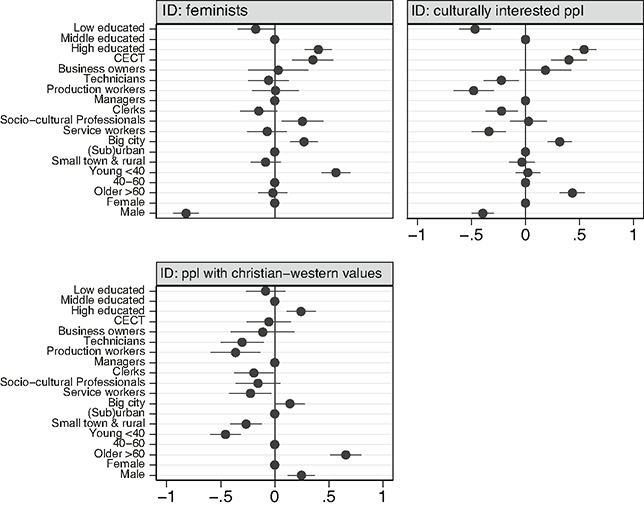

Gender/Feminism: An item about closeness to feminists is designed to capture the gender component of new conflicts, with especially the women’s movement having contributed to the emergence of the New Left.

Religion: Lastly, we ask about closeness to people with Christian-Western values. Traditionally associated with the religious cleavage and Christian Democracy, transformed aspects of this divide could also feed into a newer universalism–particularism divide.

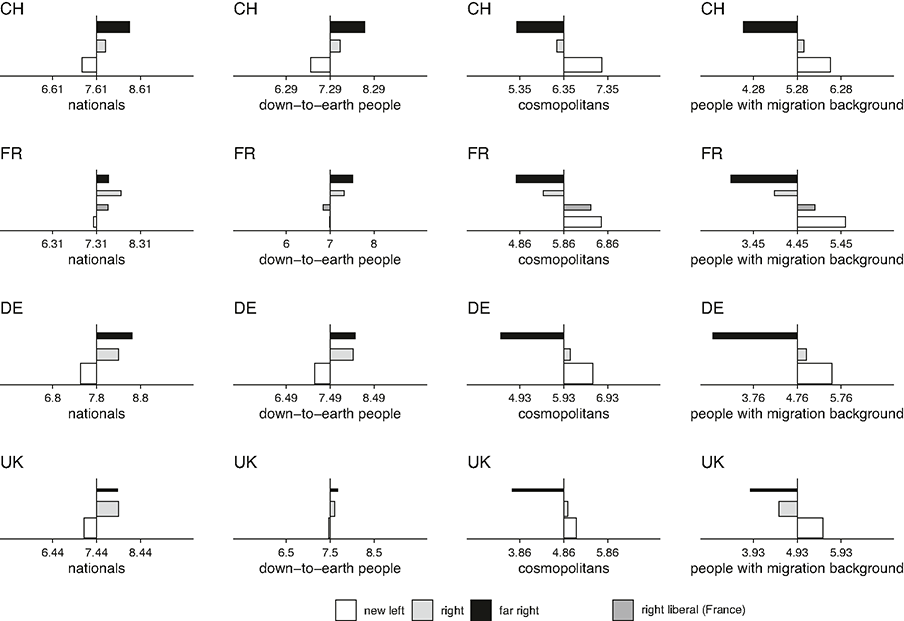

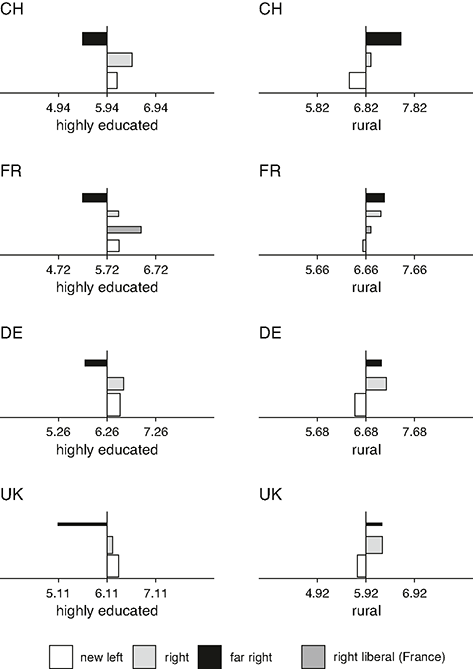

Throughout this Element, the following groups will turn out as differentiating most effectively between the two extremes of the universalism–particularism dimension: nationals, people with a migration background, cosmopolitans, and people who are down-to-earth and rooted to home. We will therefore zoom in on these groups in many of the analyses. Further items designed around the related concepts of identity, social closure, and political mobilization inquired into respondents’ networks or social interactions, perceived overlaps between different types of group boundaries, or voters’ associations of groups with specific parties. The survey also included a conjoint experiment that asked respondents to choose identity profiles to which they felt closer. The exact wording and operationalization of identity-related concepts based on these items will be detailed in the subsequent sections, along with the presentation of results.

2.2.3 Identification and Operationalization of Party Blocks

As already explained, our aim in studying collective identities is partly to look beyond country specificities in party competition to common patterns of cleavage formation. We are not primarily interested, for instance, in the role that social democratic (versus Green/left-libertarian parties) play in mobilizing the universalist side of a cleavage; or in whether a specific mainstream conservative party dabbles in the particularist Far Right field. Our interest lies in more overarching identity divides that provide voters with the cues of where they belong in the political landscape.Footnote 10

Following this logic, we investigate the political articulation of a new cleavage from a perspective of party blocks. We derive these blocks empirically and validate them theoretically. Starting from an empirical classification makes sense here because, as mentioned, parties’ ideological positions matter more than their belonging to historically grown party families. Our party classification is based on mixture models fitted to the 2019 Chapel Hill Expert Survey (CHES) data on all Western and Southern European countries, excluding Eastern Europe. The mixture model allows for a clear identification of clusters and their structures based on the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC). Moreover, it probabilistically assigns parties to clusters, which makes it easier to handle parties with amorphous profiles.

We proceed in two steps: First, based on the economic left-right and GAL-TAN dimensions of the CHES, we start with an initial clustering of parties. As per the BIC, this results in three clusters: one that is economically and socially left-wing, one that is economically right-wing and socially progressive, and another that is economically right-wing and socially conservative (roughly conforming to a tripolar model of the political space, but with the third cluster reaching beyond what is typically discussed as the Far Right party family). In a second step, we refine each first-stage cluster based on the issues on which it is most heterogeneous (considering sixteen issues available in the CHES). Note that the BIC does not indicate sub-clustering to be necessary for all first-stage clusters, but we consider within-cluster differences to gain further insights. This second step produces six narrower clusters:

1. Green left, consisting of pro-environmental, economically left, and culturally progressive parties.

2. Traditional left, consisting of economically left and culturally progressive parties that take more moderate environmental positions.

3. Left liberals, consisting of parties that take pro-environmental stances, favor civil rights over law and order, and tend to cater more to urban interests.

4. Right liberals, who are more moderate on the environment, tend more to law and order positions, and have a more rural focus than the left-liberals.

5. Traditional right, consisting of economically right and culturally conservative parties. Those parties, however, favor open societies and are more moderate on moral issues than the radical right.

6. Far Right, who are economically conservative, favor a closed society, and traditional mores.

In subsequent analyses, we focus on three party blocks based on this differentiated perspective: one based on the Far Right cluster, one on the traditional right cluster, and a New Left block that combines the green left and traditional left clusters (both of which are broadly left-wing economically as well as culturally, in line with the tripolar model of political competition, Reference Oesch and RennwaldOesch and Rennwald 2018). We opt to disregard the left liberal cluster (which only concerns the Swiss Green Liberals in the countries we study), and we go on to consider the right liberal cluster specifically for France, where we would otherwise exclude Macron’s La République En Marche as well as the Mouvement Démocrate (MoDem). Table 1 shows the final classifications of parties in our sample.Footnote 11

Table 1 Classification of parties into party blocks

| Party blocks | CH | DE | FR | UK |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| New Left | SP, GPS, PdA, AL | SPD, die Grünen, die Linke, Piratenpartei | EELV, PS, LO, NPA, FI | Labour, Greens, LibDem |

| Right | FDP, CVP, BDP, CSP, EVP | CDU/CSU | LR, DLF | Conservatives |

| Far Right | SVP, Lega, EDU | AfD, NPD | RN | UKIP, Brexit party |

| Right Liberal | – | FDP | LREM, MODEM | – |

An important question concerns electoral volatility. Here, we followed Reference Steenbergen and WilliSteenbergen and Willi (2019) and derived consideration sets from our respondents’ stated propensities to vote for different parties (full details are in the online appendix). For each respondent, we identified the list of parties they consider voting for. We then determined whether those parties are mostly situated within one of the blocks we identified, or whether there is a great deal of cross-block consideration. Our methodology suggests that the average consideration set size was greater than one party, suggesting a potential for volatility. However, this volatility appears to have been limited. The percentage of consideration sets that included only parties from one of the four blocks in Table 1 were 66.0 in England, 73.6 in France, 71.9 in Germany, and 65.3 in Switzerland. We conclude that there is constrained electoral volatility in the four countries. In addition to measuring propensities to vote, we also asked respondents for their party choice, that is, which party they would vote for if national elections were held next Sunday. We use the latter measure for most analyses conducted in the following sections.

Having introduced our survey design and established our definition of party blocks, we are now in a position to evaluate our theoretical claims empirically. In the following section, we first study the link between social structure and social identities, before we bring in party choice in Section 4.

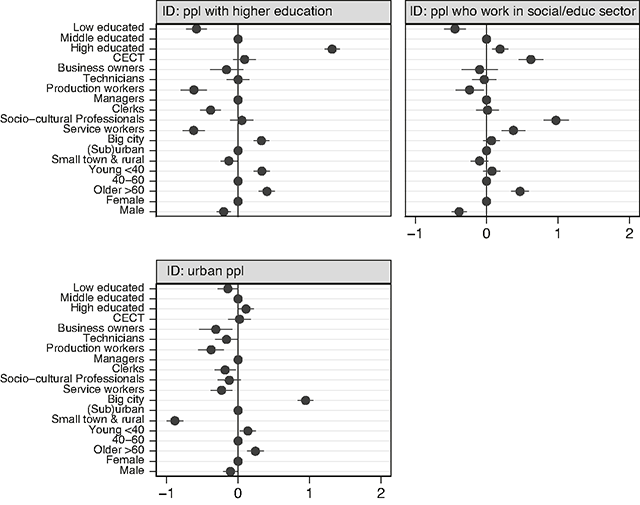

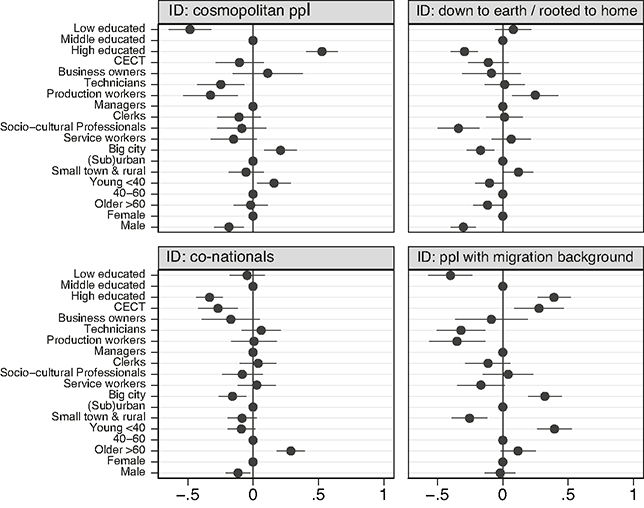

3 How Social Structure Shapes Social Identities

In this section, we argue that newly emerging political identities and antagonisms are firmly rooted in processes of profound socio-structural transformation. To substantiate this contention, we start this section by theorizing the emergence of knowledge economies and the attributes that shape opportunities and challenges in these economies. We then also briefly discuss why economic-material life circumstances are likely to shape socioculturally connoted identities, before turning to empirics, documenting (i) the structural rootedness of identities, (ii) the importance of education in structuring antagonistic sociocultural identities, and (iii) substantiating our claim about an emerging cleavage through analyses of social networks and the antagonistic nature of identity formation at the poles of the new cleavage.

3.1 Knowledge-Based Economies: Structuration and Identities

All existing accounts of the formation of a new party-political cleavage between universalism and particularism in Europe link this development to important societal transformations as key drivers of cleavage formation. A key distinction can be drawn between approaches that emphasize the role of economic and social structural change – linked to tertiarization, globalization or new inequalities (e.g., Reference KitscheltKitschelt 1994 as an earlier example and Reference Iversen and SoskiceIversen and Soskice 2019 as a more recent one), and approaches that see political and institutional developments of international integration and the weakening of the nation-state as crucial in this process (e.g., Reference BartoliniBartolini 2005a or Reference Hooghe and MarksHooghe and Marks 2018). As we explain in this section, our perspective is closer to the former approach. We insist on the emergence of the knowledge economy as the main structural driver of political realignment. While the politicization of borders and immigration is clearly a very important dimension of current cleavage formation, the focus on international integration and the nation-state alone cannot account for the fact that universalistic and particularistic voters and parties diverge on many additional issues that are not related to international integration, such as gender or cultural liberalism.

Our focus on economic and social structural change in driving the antagonism between universalistic and particularistic political positions does not imply, however, that we conceive of the drivers of cleavage formation in purely materialistic terms. Rather, we re-connect with the understanding of structural change as an encompassing transformation of people’s economic, social, and cultural life circumstances and perspectives – as introduced, for example, by Betz’s emphasis on “modernization” (Reference Betz1994). Given the encompassing nature of this change, it affects both material preferences and cultural values that people hold. Related and later contributions have also adopted such an encompassing perspective on the implications of economic and social change (e.g., Reference KitscheltKitschelt 1994, Reference Kriesi, Grande and LachatKriesi et al. 2008, Reference BornschierBornschier 2010).