Ever since the publication of Edward Said’s Orientalism, the precise nature(s) of the various Hispanophone Orientalisms have been hotly debated, with literary Orientalism drawing the most attention. In this article, I focus on Orientalist texts of a non-literary form (at least in the stricter sense of the word) that represented various parts of Southeast Asia for the Peruvian reading public. In so doing, this article brings into the discussion a region that has been marginalised in the more East Asia-centred study of Orientalism in Latin America. Through the comparison of these depictions of Southeast Asia with the more ‘mainstream’ Orientalist rhetoric about the immigrant Chinese community in Peru, I argue that Orientalist discourse in Peru in the 1920s was multifaceted, with both ‘modern’ and more ‘medieval-colonial’ strands coexisting: the deciding factor over which strand would take precedence in a given context was the presence or absence of the corresponding Asian community in Peru. In the case of Orientalising discourses regarding Southeast Asia, this article focuses on the circulation of Spanish-language Orientalist pieces, that is, texts produced elsewhere that were deemed worthy of interest for a Peruvian audience and its sensibilities. Furthermore, as we will see, the different strands that emerged even within the Orientalist texts circulated to Peruvian readers regarding Southeast Asia responded to the complex history of Hispanophone Orientalism.

Overall, the careful examination of materials on Southeast Asia yields a more nuanced picture of Peruvian Orientalism, one that signals new directions of research in the rest of Latin America. In this respect, it constitutes a contribution to the global history of Orientalism by proposing a new understanding of Latin American Orientalism looking beyond the usual corpus of sources studied in this endeavour—that is, literary materials written by well-travelled, cosmopolitan writers hailing from Latin America whose interests usually revolved around China, Japan, and the Arab world. In this respect, Peru showcases a particular contrast between being a society with an important history of Asian immigration and yet simultaneously lacking a significant group of officials or travellers who wrote about Asia, and particularly Southeast Asia, in any depth. In a way, it is the reverse image of countries such as Chile or Mexico, which featured smaller Asian communities but produced figures such as Pablo Neruda and Miguel Covarrubias, who left behind important testimonies of their sojourns in Southeast Asia.Footnote 1 A truly global history of Orientalism, however, requires moving beyond these Latin American sophisticates and their sophisticated readers. By examining Orientalist imagery that circulated among wider sectors of Peruvian society, this article takes a step in this direction, while also contributing to the small, but growing, body of scholarship that studies relations, connections, and parallels between Southeast Asia and Latin America beyond the early modern period.Footnote 2

Orientalism, according to Edward Said, refers to three elements: Orientalism as an academic endeavour, Orientalism as an idea based on the insurmountable ontological and epistemological difference between ‘the Orient’ and the West, and Orientalism as a Western impulse to conquer, restructure, and hold authority over ‘the Orient’. While he circumscribed his study to Anglo-French Orientalism, he admitted that while Orientalism(s) existed among Germans, Russians, Portuguese, Italians, Swiss, and Spaniards, it was not as robust as those of the British and French. According to Said, when discussing this hegemonic discourse, we must take into account the tangible power relationship that existed between ‘Orientalist’ experts and the ‘Orientals’ they studied.Footnote 3 Said’s seminal study led to many discussions about the nature of Orientalism and its relationship with colonialism and imperialism in Asia. Understandably, most of the discussion surrounding Orientalism focused on the production of knowledge by governments, officials, or individuals of the countries that colonised Asia or how locals tried to appropriate their methods.Footnote 4 Even if their scholarship is no longer taken at face value,Footnote 5 there are good reasons for studying these groups of people. After all, if Europeans and Americans were to dominate these Asian peoples, their officials had a very strong motivation to study them and produce actionable research about the colonised, research that in turn gives us insight into their prejudices and biases.

The particularities of specifically Hispanophone Orientalism and its differences from the Anglo-French Orientalism that served as Said’s starting point has attracted the attention of a robust cohort of scholars. Julia Kushigian has criticised the notion that other Orientalisms were mere variations of or derivations from Anglo-French Orientalism, arguing that Hispanophone Orientalism in particular had a much longer and richer history than those of its western European neighbours and that, at least in its literary form, it has been characterised by fascination and respect for the Other, rather than by a desire for domination.Footnote 6 Scholars such as Silvia Nagy-Zekmi and Ignacio López-Calvo have indeed focused on the literary representation of the Orient, particularly on the late 19th and early 20th century literary movement known as ‘modernismo’.Footnote 7 Araceli Tinajero argues that modernista writers were informed by a Latin American eclecticism and openness that set their understandings of Asia apart from the tradition studied by Said.Footnote 8 Nagy-Zekmi agrees that Orientalist modernista writers held a fascination for ‘exotic’ (and erotic) Asian cultures, but they still placed Asians at the lower end of the social hierarchy, portraying them as incapable of experiencing progress.Footnote 9 Erik Camayd-Freixas adds that the emergence of racist positivism resulted in a modernismo that was not only ambivalent, but ‘radically bipolar’.Footnote 10 Indeed, while overt racism might have been toned down in recent decades, these exoticising and Orientalist representations of Southeast Asia in Latin America persist in the present.Footnote 11 In fact, Orientalism looms so large that even Asian-Latin American writers have engaged in self-Orientalism in their literary work.Footnote 12

Nevertheless, while Kushigian’s positive valuation of the Hispanophone literary tradition has been nuanced by later literary scholars, my approach in this article eschews the strictly literary and instead focuses on non-fiction texts about Southeast Asia published for mass consumption by the Peruvian reading public. In this respect, my research is comparable to that of Martín Bergel, whose study of Argentinian Orientalism makes use of a wider array of sources than those of literary critics and historicises them with more precision. Bergel focuses on unearthing the trajectories of Argentinian Third World-ism and solidarities with anticolonial movements in Asia and Africa, which meant that the Latin American intellectuals and commentators he studies were drawn to countries like China, India, or Morocco.Footnote 13 Unlike Bergel, my focus lies in disaggregating the broad and often undifferentiated ‘Orient’ of Peruvian readers in the 1920s, instead centring a region that was often overlooked or treated as peripheral within that ‘Orient’, that is, Southeast Asia.

‘Southeast Asia’ itself as a geographic concept requires some explication. Our current understanding of ‘Southeast Asia’ emerged in the 1940s. It was first used by the Allies as a territorial demarcation for military responsibilities during the Second World War, and was later solidified by Cold War concerns, resulting in a region usually understood to comprise Burma/Myanmar, Laos, Vietnam, Thailand, Cambodia, Malaysia, Singapore, Brunei, Philippines, Indonesia, and Timor Leste.Footnote 14 Shifting focus to Southeast Asia and disaggregating it from East Asia as ‘the Orient’, rather than merely an anachronism, allows us to identify certain contours that have previously gone mostly unnoticed, which in turn leads us to a reassessment of Latin American Orientalism(s) as a whole. To this end, I focus mainly on the Spanish-language periodicals Variedades, Mundial, El Comercio, and La Crónica. The first two were weekly magazines aimed at the Peruvian elite, featuring longer form articles and numerous illustrations and photographs. The latter two were dailies, with El Comercio being the country’s newspaper of record, which, while focusing on news reports, on occasion also made room for longer essays. West Coast Leader, an English-language periodical published a few times per week and aimed at the expatriate community in Lima, is lightly referenced as a contrast to the materials read by the mainstream reading public.

As we will see, Peruvian elites themselves held a complicated positionality regarding Orientalism in the period under study, which at the global level bridges the end of the First World War and the onset of the Great Depression and in Peru matches the Oncenio period (the eleven-year long authoritarian administration by civilian strongman Augusto Leguía). Marked by a keen desire for modernisation and Americanisation, another layer of Westernisation was added to an urban community that had been previously fascinated by western European culture from Spain, France, and the United Kingdom. Indeed, these elites understood themselves as an extension of the Western world and were very willing to align themselves with Orientalist prejudices from the core regions of Europe.Footnote 15 And yet, they did not colonise any Asian peoples, which meant that these prejudices were, for the most part, not actionable—except in the case of Chinese immigrants in Peru, as we will see. However, regarding Southeast Asia, whence no significant immigrant community had arrived, Peruvian readers were supplied with an exoticising portrayal in which impulses for domination were muted—even if not altogether absent.

By putting Peru and Southeast Asia in dialogue through the movement of Orientalist representations, this article answers Matthew Brown’s trenchant call for putting an end to the self-isolation of post-early nineteenth-century Latin American history and integrating it into global history.Footnote 16 In this fashion, it joins a cohort of works, such as those of Mateo Jarquín, Tanya Harmer, and Alberto Álvarez, whose integration of revolutionary Latin American leftism into global Cold War trajectories are recent additions to the growing field of the global history of Latin America.Footnote 17 This article contributes to a more global history of Orientalism as well, by shedding light on representations of Southeast Asia, a region that is oft-overlooked by scholars of Latin American Orientalism.

This article begins with a brief genealogy of Orientalism in Peru stretching back to the colonial period up to the late nineteenth century. It then delves into the more visible strand of Orientalist discourse directed at the Chinese community in Peru, which serves as a baseline comparison to representations of Southeast Asia. Portrayals of the region, in turn, reveal two different strands, one that emphasises Orientalist wonder and another that has little to no traces of Orientalist tropes, as elucidated in the last section.

Orientalism in Peru

A brief overview of the genealogy of Hispanophone Orientalism in Peru may be pertinent. With its point of origin in Spain, Camayd-Freixas noted how the Islamisation of the Iberian Peninsula between 711 and 1492 left a mark of ambivalence on Spanish Orientalism, wherein ‘Orientals’ (read: Muslims), continued to be perceived as both a persistent threat and a source of knowledge and mystery.Footnote 18 Consistent with other strands of Orientalism, Spaniards lumped all ‘Orientals’ together, hence extending this ambivalence to all Asians, including East Asians. This generalised ambivalence towards ‘Orientals’ travelled to the Americas with Spanish colonisers, where Orientalism informed Iberian desires to conquer parts of Asia in the sixteenth century (particularly China and Japan), hoping to gain treasure and converts.Footnote 19 In the reverse direction, while there were several instances of threats coming from Japan and China against the Spanish Philippines during the colonial period,Footnote 20 the Spanish-speaking colonial elite in the Americas never felt directly threatened and hence continued to be fascinated by Asia.Footnote 21 The Manila galleon, which brought Chinese luxury goods to the Americas via Manila and Acapulco, amplified the idea of an opulent Orient,Footnote 22 while also bringing enslaved Asians from East, Southeast, and South Asia, most of whom ended up in Mexico, but some also in Peru.Footnote 23 These very limited numbers of Asians in colonial Peru were not perceived as threats to the social order, nor did they trigger an Orientalist backlash against them—as would be the case in the nineteenth century.

Arguably, whatever ‘Orientalist’ impulse for domination of the Other that was present in the colonial period remained overwhelmingly focused on the natives of the Americas, not Asians.Footnote 24 This trend continued after independence, when the impulse remained focused on the indigenous peoples of the new republics.Footnote 25 In the case of Peru, it was directed towards another, literal ‘Orient’, inasmuch as it lay in an eastward direction: the Amazon rainforest.Footnote 26 Indeed, Peruvian policies and discourses in its own Oriente arguably rhymed with the kinds of rhetoric used by colonisers in Southeast Asia to justify their presence there, such as the French ‘mission civilisatrice’ (‘civilising mission’), the Dutch ‘ethische politiek’ (‘ethical policy’), or American ‘benevolent assimilation’.

With no large group of Spanish-language scholars or colonial bureaucrats engaged in the endeavour of producing Orientalist knowledge and scholarship on Southeast Asia in the nineteenth century,Footnote 27 a peripheral region such as Peru was several degrees removed from easily available Orientalist texts. Perhaps the one public intellectual to wrestle with the topic was Sebastián Lorente, a Spanish-born teacher who migrated to Peru in 1843, where he was incorporated into Lima’s intellectual elite.Footnote 28 A writer of several influential and widely distributed textbooks, his Compendio de la historia Antigua de Oriente para los colegios del Perú (Compendium of Ancient Oriental History for Peruvian Schools), published in 1876, constituted the touchstone of knowledge about Asia for several generations of Peruvian students. A derivative work, his book featured several Orientalist prejudices and crude generalisations: Asian civilisations were characterised by the steady degeneration of family and religious values, which resulted in the caste system, despotism, and the unjustifiable opulence of the elite. Asia’s past was brilliant, but ‘Oriental civilisation is both fragile and unable to achieve unlimited progress. Oriental empires collapse suddenly or become paralysed’.Footnote 29 Lorente’s derivative Orientalism would cast a long shadow in twentieth-century Peru.

Baselines of Peruvian Orientalism: Asians in Peru in the twentieth century

The key variable when determining which kind of Orientalism would predominate in Peru was whether there was a significant community of a given Asian nation present in Peru at the time. Here we focus on the Chinese, whose large numbers conditioned the rise of a hostile strand of Orientalism, resembling the Anglo-French variant studied by Said, which emphasised their degradation and sought to dominate them.Footnote 30 In this respect, the work of scholars like Daisy Saravia and Juan José Heredia give us a first baseline of what non-literary Orientalism looked like. In her analysis of the Peruvian magazine Variedades in the 1910s, Saravia shows that depictions of, and commentary about, the Chinese community in Peru were almost entirely homogenising and negative. Chinese were portrayed as an unassimilable Other who were responsible for a series of social ills, such as gambling and opium abuse. While there was some room to express a grudging fascination for certain aspects of Chinese culture, it quickly reverted to portraying their artforms as incomprehensible and unpleasant to the senses. Heredia, who studies cartoons published in both the mainstream and working-class press, shows how the Chinese were portrayed as grotesque, inscrutable, disease-riddled, opium-addicted Others who came to Peru to steal jobs.Footnote 31 However, it is key that these sharply negative representations were all focused on the Chinese in Peru. The Chinese in China had no role to play.

Negative attitudes towards the Chinese immigrant community in Peru had evolved over time. The first Chinese labourers arrived in Peru in 1849, but as their employers limited their contact with the outside world,Footnote 32 the development of widespread anti-Chinese sentiment was initially contained. As larger numbers of Chinese workers sought opportunities elsewhere as their work contracts ended in the 1860s and 1870s, they often became shopkeepers or restaurateurs. This trend gained momentum over time, as more Chinese immigrants arrived in Peru unencumbered by contracts that bound them as indentured servants.Footnote 33 Their greater exposure to broader Peruvian society, however, triggered the emergence of anti-Chinese attitudes. Portraying them as lackadaisical about their hygiene, Peruvians accused the Chinese of being behind the yellow fever epidemic of 1868 and the bubonic plague epidemic of 1903.Footnote 34 As abject Others, they were even accused of being responsible for Peru’s defeat during the war with Chile in 1881, as ill-treated Chinese labourers had welcomed the invading Chilean army as their liberators.Footnote 35 Wrathful Peruvians retaliated by burning down Lima’s Chinatown and attacking the Chinese in other parts of the country.Footnote 36

By the early twentieth century, Peruvian Orientalism targeting local Asians had ‘caught up’ with the times, so to speak. Colonial Orientalism—the kind that had inherited a certain fascination with the East from medieval Spain—appeared to have been set aside and replaced. While Peruvians still lacked the impulse to conquer the Asian continent itself, they emphasised the degeneracy of the Chinese community in Peru and sought to dominate and reform it. In the 1920s, cartoons in Variedades continued to denigrate the Chinese, one showing several Chinese men hanging by their braids from a ship’s loading hook, accompanied by a limerick saying ‘Importante importación/que desde el Asia se aporta/para agraciar más la raza!…/Si vienen más… pues… ¿qué importa?’ (‘An important import/that comes from Asia/to make the race more graceful/If more come… well… what does it matter?’) (Figure 1).Footnote 37 A cover from the magazine Mundial featured extremely Orientalist imagery of ‘The Mandarin’, including opium consumption (with an unusually shaped pipe), a Buddha figure, and an illustration of a dragon with nonsensical Chinese characters.Footnote 38 The impulse to shape local Chinese was clear in a government measure ordering the evacuation of the Chinese who lived in downtown Lima and their forcible (and dispersed) relocation elsewhere (the concentration of Chinese was seen as a threat to the health and morals of Lima).Footnote 39 Meanwhile, a letter published in Mundial, while favouring Chinese immigration into the country, ended with a call for fines or prison sentences for Peruvians who married Chinese immigrants.Footnote 40 Even radical thinker and iconoclast José Carlos Mariátegui, while not entirely indulging in the kind of ‘scientific racism’ en vogue at the time, still harboured negative stereotypes about Chinese immigrants.Footnote 41 Concern appeared to have replaced ambivalence.Footnote 42

Figure 1. Racialized portrayal of Chinese men. ‘Chirigota: importación’, Variedades, 25 November 1922. Biblioteca Nacional del Perú.

Disaggregating the Orient: Southeast Asia in Orientalist essays circulated in Peru

Coverage of ‘the Orient’ in the Peruvian press was generally geared towards the interests of an ‘educated’ reading public that sought to develop a semblance of a rich ‘cultura general’ (‘general knowledge’) that they could later deploy in sophisticated social settings. Thus, the press would sometimes feature essays addressing various features of ‘Oriental’ cultures, with East Asia garnering the larger share of coverage. Prejudices against local ‘Orientals’, however, would continue to shine through. As shown by Patricia Palma and Maria Montt Strabucchi, even when events were covered in a generally positive light, as was the case with the Chinese Revolution of 1911, the Peruvian and Chilean press still insisted on deriding local Chinese communities.Footnote 43

In contrast with the much larger corpus of texts on East Asia, inspection of the articles published about Southeast Asia reveals that rather than being in harmony with the ‘mainstream’ Orientalism that painted the local Chinese community in a poor light, what emerged were at least two starkly contrasting discourses. While one part of Southeast Asia (the Philippines) was hardly Orientalised at all, the rest instead appeared to be informed by a more medieval-colonial Orientalism, one that viewed the Orient with enchantment and wonder. In this fashion, the former discursive strand appeared to be ahead of its time (inasmuch as it did not Orientalise its subjects), while the latter was behind its time (inasmuch as it did Orientalise its subjects, but did so with fascination rather than loathing, the latter of which had become the norm in Peru by the early twentieth century).

A non-Orientalised Southeast Asia: The Philippines

The most remarkable aspect of how the Philippines was represented in the Peruvian press was how unremarkable it appeared. There were no sweeping generalisations about the backwardness of the Filipinos or their racial traits, about how exotic the lands and peoples were, or how erotic their women. As a matter of fact, the Philippines read essentially like any other Latin American country, with articles mostly focusing on political matters, such as the appointment of a new governor-general,Footnote 44 developments in the independence issue,Footnote 45 geopolitics,Footnote 46 economics,Footnote 47 epidemics,Footnote 48 and even natural disastersFootnote 49 and sports.Footnote 50 The Wood-Forbes report of 1921, in which soon-to-be governor-general Leonard Wood dismissed Filipino grievances out of hand and rejected the idea of independence for the islands in the short term, merited a good amount of coverage as well, none of which employed Orientalist tropes.Footnote 51

What lay behind such non-Orientalist coverage of the Philippines? There are several interconnected explanations. To begin with, the dearth of Spanish Orientalists writing about the Philippines in the nineteenth century meant that there was no significant body of exoticising Spanish-language texts available for easy transmission to Peru.Footnote 52 Instead, due to its history as a Spanish colony, the Philippines could appear as a thoroughly Hispanicised country, with politicians and athletes with recognisably Hispanic names, like Manuel Quezon, Sergio Osmeña, Lope Tenorio, Pedro Guevara, Isauro Gabaldon, Pancho Villa, and Ignacio Fernández, dominating in the press.Footnote 53 Such names carried an implicit message: their bearers could be presumed to share a language and worldview with Peruvian readers.Footnote 54 But above all, they could be imagined as individuals with individual traits and motivations. Another clue lies in an article about the founding of a board that would provide logistical and financial support to both Latin American and Filipino students in Spain.Footnote 55 The casual inclusion of Filipinos in the initiative was one of many signals apprehended by Peruvian readers indicating that Filipinos were, after a fashion, understandable as part of the broader ‘Hispanic family’ rather than mysterious Oriental Others.

Another factor that might be considered was the convergence of United States’ imperialism in the Philippines and Peru. Peru’s Oncenio was characterised by an extreme Americanophilia and official desire to modernise in the mould of the United States.Footnote 56 Thus, there may have been an impulse to portray the United States’ colony, the Philippines, as a modern, non-Orientalised locale: an outcome of precisely the kind of invigorating American modernity that Leguía envisioned for Peru. Yet, despite the ample room for laudatory commentary about American colonialism in the Philippines, such rhetoric does not appear to have left a trace in the Peruvian written record.

In actual fact, the non-Orientalised portrayal of the Philippines that Peruvians readers were exposed to ran counter to Orientalist messaging about the Philippines produced by United States scholars and officials. The St. Louis World’s Fair encouraged the American public to equate the Philippines with the archipelago’s non-Christian peoples (reinforcing the discourse of a civilising mission).Footnote 57 For Peruvian readers, despite references to Filipinos belonging to the ‘Malay race’, the Philippines appeared to be equated with a Catholicism and culture not too unlike their own.Footnote 58 While it is unclear whether Orientalist images and narratives about the Muslim Moro communities or the indigenous Igorot or Lumad peoples made it to Peru, Peruvian readers had an in-built motivation to dismiss them as ‘proof’ of the general Oriental nature of the entire country. These communities are broadly referenced in an article about Josephine Kremser, an American woman campaigning for Philippine independence, in which she is quoted as saying:

It is true that there are some tribes living in a state of complete ignorance; but they do not represent in any way the Philippine people any more so than the Indians of this country represent the people of the United States. In Mexico, Brazil, Chile, Central America, and other Spanish American countries, there are also Indians, and who would dare say that those peoples are incapable of self-government, simply because they have those tribes in their territories?Footnote 59

Peruvian readers could identify themselves among those ‘other Spanish American countries’ that also contained ‘tribes living in a state of complete ignorance’ (especially those living in their own Oriente, i.e. the Amazon rainforest) but who still considered themselves, as a whole, ‘civilised’ nations.Footnote 60 In this sense, their perspective would have been even closer to those Spanish-speaking elites in the Philippines with their Spanish names, who disavowed the indigenous peoples of the archipelago as Others.Footnote 61 Even another image that presumably could have served to make the Filipino appear as an Other to an American public probably backfired when presented to Peruvian readers: the flagellant.Footnote 62 While possibly horrifying a more Protestant readership in the United States, an image of a Catholic Filipino who lacerated his own back during Easter instead probably had the effect of reassuring Peruvian readers that Filipinos practiced the same faith as they did, if perhaps in a slightly old-fashioned way, but nevertheless rendering them as not Oriental.Footnote 63 As will be seen in the next section, this type of matter-of-fact coverage of a Catholic religious practice stood in stark contrast with the exoticising depictions of a startling blend of undifferentiated Hindu and Buddhist religious manifestations and artforms in the Dutch East Indies.

Furthermore, as Paula Park and Kelly Van Acker have shown, Hispanophone Filipino intellectuals went to great lengths to connect the Philippines to a wider Latin American world. They upheld the Spanish language to insert themselves in an anticolonial network alongside the Spanish-speaking republics of the Americas and espoused Latin American writers like the Nicaraguan Ruben Darío and the Peruvian José Santos Chocano as touchstones of Filipino letters. Both scholars admit, however, that it is still unclear whether Latin American thinkers reciprocated these feelings.Footnote 64 While the Philippines remained in the picture in Peru in the nineteenth century, as evidenced by the aborted Peruvian naval expedition of 1866 and a failed anticolonial raid in 1877,Footnote 65 it is still unclear to what degree (if any) the 1896 Philippine revolution and the 1899 Philippine-American War generated a sense of solidarity in Peru. At any rate, Peruvian anti-imperialist intellectuals in the 1920s (including José Carlos Mariátegui, a fierce critic of the Leguía administration’s pro-American policies) appeared to be more interested in developments in India, China, and Türkiye than in the anticolonial struggle in the Philippines against the United States.Footnote 66 At any rate, enough of the history of Spanish colonisation and Hispanic culture in the Philippines remained that Peruvians were not inclined to think of it as culturally ‘Oriental’. Conditions would be very different for the rest of Southeast Asia.

Oriental splendour, wonder, and exoticism: The rest of Southeast Asia

When we get to the rest of Southeast Asia, a different strand emerges, one that reveals the multivalent branches of Orientalist discourse that could coexist in a single society. The essays and articles circulated about other parts of Southeast Asia for the Peruvian reading public stood in stark contrast with the news about the Philippines. They were almost completely decontextualised from matters of politics, geopolitics, and economics. Significant developments like the rise of leftist movements or thought and how they intersected with local societies in French Indochina and the Dutch East Indies remained outside the picture.Footnote 67 Unlike the historically and politically informed portrayal of the Philippines, which stood in the process of seeking its independence in clearly intelligible ways, the rest of Southeast Asia appeared splendorous, exotic, mysterious—and erotic.

The trope of Oriental splendour emerges in the portrayal of the lifestyle of Khải Định, the emperor of Annam (part of French Indochina) in the magazine Variedades. Photo essays highlighted his luxurious lifestyle, both in Annam and during his visit to France. One set of portraits was accompanied by text that was full of wonder regarding the ‘Orient’:

Our curious graphic information, presents the Emperor, the Empress, and the heirs to the throne in Annam, in various aspects of their pompous life, showcasing the magnificence and ostentation that these Oriental monarchs can enjoy, even in these days of serious, worldwide economic crisis.Footnote 68

Medieval-colonial Orientalist tropes came to the fore in this description. To begin with, the information from Annam is assumed to be ‘curious’, a word that was not used when Variedades covered the families of the monarchs of European states. Behind this presumption of strangeness lay wonder, however. Both sets of photographs emphasised his splendour and reminded Peruvian readers of one of the traits Sebastián Lorente established as distinctive to ‘Oriental civilisation’: luxury. They were invited to wonder at—not dominate—his Oriental pomposity.

The general decontextualisation of images from Southeast Asia could feed into Orientalist enchantment. Unlike the Philippines, where US colonial authority was consistently referenced in the press, Khải Định potentially appeared as a completely sovereign monarch to a vaguely informed Peruvian reader. In this manner, while Aldrich has argued that Khải Định’s visit to France served the purpose of showing to the French population that the exotic ‘Oriental’ king was loyal and subordinated to France, thus buttressing support for the imperial enterprise,Footnote 69 the photos supplied by Variedades may have conveyed a different message. In one picture, Khải Định gave a military salute while wearing an imposing royal outfit in the upper centre of the portrait, while several more modestly (yet still sharply) dressed French civilians and military officers lingered in the lower half of the picture (Figure 2). This reversed the visual hierarchy that Nerissa Balce has pointed out in pictures of dead Filipino combatants during the Philippine-American War, wherein the victorious, superior White American soldiers would appear in the upper part of the photograph, while the defeated, debased Filipino Others appeared at the bottom.Footnote 70 Lacking immediate context of the colonial relationship between Annam and France in the photo essay itself, a Peruvian reader might see Khải Định as a grand, sovereign monarch, perhaps similar in status to other Oriental monarchs, such as the king of Siam.Footnote 71 Yet, unlike the rapidly industrialising and militarising Japan, he was probably understood as unthreatening.

Figure 2. The Emperor of Annam in Paris. ‘El emperador de Annam en París’, Variedades, 12 August 1922. Biblioteca Nacional del Perú.

Peruvian readers were also invited to marvel at mysterious Oriental customs in other parts of mainland Southeast Asia. The Siamese were portrayed as artistic, yet superstitious, lazy, of dubious morals, and physically unattractive. Of course, significant space was devoted to the matters of marriage customs and the way women were traded in such a context—a common Orientalist trope. The Siamese, ‘like many other peoples of the Far Orient, have their particular ideas’ about marriage, and emphasis was placed on the customs of arranged marriages, dowries, and polygamy. From Burma, a Baptist reverend reported that single men were unhappy with the rising price of dowries payable to the father of the bride.Footnote 72 Peruvian readers, with their ‘modern’ marriage rites (although arranged marriage had not truly disappeared among the upper elite), were left to wonder at the strange customs of the ‘peoples of the Far Orient’, to use the words of El Comercio.Footnote 73

For exotic wonders, the Dutch East Indies provided the largest corpus of material for Peruvian readers. I analyse three non-literary essays of significant length: ‘Las danzas javanesas’ (‘Javanese Dances’), ‘El teatro en el extranjero: el teatro javanés’ (‘Theatre Abroad: Javanese Theatre’), and ‘Descubrimiento y captura del famoso “dragón javanés”’ (‘Discovery and Capture of the Famous “Javanese Dragon”’). The only identity known for certain is that of the author of the third article, a Spanish writer and translator named Marcos Rafael Blanco Belmonte. The other two remain anonymous, though it is likely that the author of ‘El teatro en el extranjero’ was Spanish, while it is also highly likely that the author of ‘Las danzas javanesas’ also was not Peruvian.Footnote 74 Rather than trying to deconstruct the mental world of these foreign producers of Orientalist discourse, my focus here lies in reconstructing the picture that Peruvian consumers of Orientalist discourse could put together of Southeast Asia in general, or the Dutch East Indies, in particular.

In various ways, these texts reinforced the medieval-colonial Orientalist outlook of Peruvian readers. To them, Southeast Asia was presented as timeless and amorphous. Its recent history and economic developments were not seen anywhere; it was even unclear who their colonial masters were. The only period presented as being of some interest was its antiquity, an Orientalist trope familiar to Peruvian readers from their reading of Sebastián Lorente.Footnote 75 Spatially, it was shapeless: multiple regions and cultural artefacts from across the Dutch East Indies were labelled ‘Javanese’, a term repeatedly associated with exoticism in these essays. Its arts might be greatly developed, its culture exotic, and its women erotic; but its peoples could also be depicted as lazy and indistinguishable from each other. And yet, the impulse to dominate and restructure the lives of these Asian communities was mostly absent, except when it came to women.

In these essays, Peruvian readers would find confirmation of Lorente’s claims about the Orient’s great ancient past but present stagnation or degeneration—even if the value judgement on such paralysis could be radically different. ‘El teatro en el extranjero’, while purportedly aiming to build interest in Javanese theatre, opened with a backhanded compliment that was harsh enough to be a front-handed insult:

Javanese theatre is a popular art, so ancient that it should be included among the oldest Asian traditions, and it has not been transformed nor developed by later concepts that may approach our modern culture …. It remains today like the remnant of a paralysed civilisation. And much like other expressions of a primitive and puerile culture, it is of extraordinary interest to our most refined artists.Footnote 76

The author of ‘Las danzas javanesas’, while holding a more positive valuation of Javanese artforms, operated within the same framework. Javanese dance had an ancient and dazzling origin, and it had survived intact the onslaught of foreign threats: ‘neither Hindu art nor Islamism, when this religion was introduced partially in the island, were able to dissipate this practice that is so ingrained in this race and is so very rooted in the heart of the people’.Footnote 77 We can thus see a contrast between a view that wished for (Western) modernisation of Javanese performance art and another that valued its resistance to outside influences. Nevertheless, they both agreed that Javanese performance was an ancient tradition that remained frozen in time, a typical Orientalist trope that Peruvian readers were eager to consume.Footnote 78

It is in the appreciation of Javanese artforms that we can see just how jumbled the geography of the region could get and the power the word ‘Java’ had among the Orientalist consumer public. ‘El teatro en el extranjero’ conflated Java and Bali (two separate islands with distinct cultures) rather egregiously: ‘What has arrived in Europe until now is the mechanics of the puppet theatre of Bali. We have seen the silhouettes of characters cut from leather … and, above all the hindustanic deities, whose heroic acts, that always contain myths, are the basis for Javanese puppetry.’Footnote 79 The same mixing of Java and Bali appeared in Blanco’s ‘Descubrimiento y captura del famoso “dragón javanés”’, wherein, after a successful hunt for the Komodo dragon, the members of the expedition headed out to ‘Bali to study its volcanoes, gather rare samples of fauna and flora, and to photograph its curious islanders, among whom the Javanese dancer stands out, who, beating the wings of the queen of the skies, and to the rhythm of a melopoeia, performs the picturesque “eagle dance”’.Footnote 80 Geographic precision was beside the point; ‘local’ artistic expressions anywhere in the Dutch East Indies needed to be ‘Javanised’ for consumption abroad. This was consistent with the reception of all things Java among the American consumer public, for whom the exact location of Java was nowhere as important as it being a byword for remoteness and exoticism.Footnote 81

Going even farther afield geographically—and deeper textually—when the author of ‘Las danzas javanesas’ explained the origin of Javanese dance, they relied on older, Indian versions of the Mahabharata but tried to pass them off as a more Javanese Arjunawiwaha. In the author’s telling of Arjunawiwaha, once the divine nymphs (bidadari) were created, Siva sprouted four faces to contemplate them.Footnote 82 There is a discrepancy here, however: in the Javanese Arjunawiwaha, composed by eleventh-century court scholar Mpu Kanwa, the one who actually sprouted four faces was Brahma.Footnote 83 As shown by Zoetmulder, this was Mpu Kanwa’s innovation; in the Mahabharata, it was indeed Siva who experienced the emergence of multiple faces.Footnote 84 Clearly, the author of ‘Las danzas javanesas’ based their narrative on the Mahabharata, but tried to tap into the more Javanese legitimacy of Arjunawiwaha. In this fashion, they went against the grain of the Dutch Orientalist quest for authenticity. Dutch scholars sought it in older, Indian texts, rather than in those from Java, which were often seen as degraded variants.Footnote 85 This more popular strand of Orientalism visible in the Peruvian press, however, was more focused on Java than on the intricacies of scholarly Orientalism, hence the displacement of the source.

As to the culture and arts that dominated much of the essays, one can see how the Orientalist trope of a radical ontological difference between Western and Oriental civilisation was presented. ‘Las danzas javanesas’ stated that:

A considerable difference separates the fundamental principles of Asiatic and Western dance. While in the West, dance, be it theatrical or mere social expansion, has, but for a few exceptions, the sole aim of visual grace [gracia plástica], be it individual or collective, but never psychic expression … in Asiatic dance, on the contrary, the visual is always subordinated to the spiritual. … The Javanese does not dance to entertain or distract himself, but rather to exteriorise ideas and sensations of beauty. In the Orient, dance is extremely meaningful: in Hindu mythology certain gods dance and in their dances, religious, scientific, and aesthetic ideas are entangled. … Those who have not seen a Javanese dancer move, will hardly be able to get a notion of the harmonious grace that guides the movement of those swarthy arms, accentuated by the extraordinary elasticity of her hands, that gyrate, vibrate, extend and withdraw with unimagined tremblings. The head, in the meantime, remains impassible, the body static and the legs moving slowly, sliding with feline agility.Footnote 86

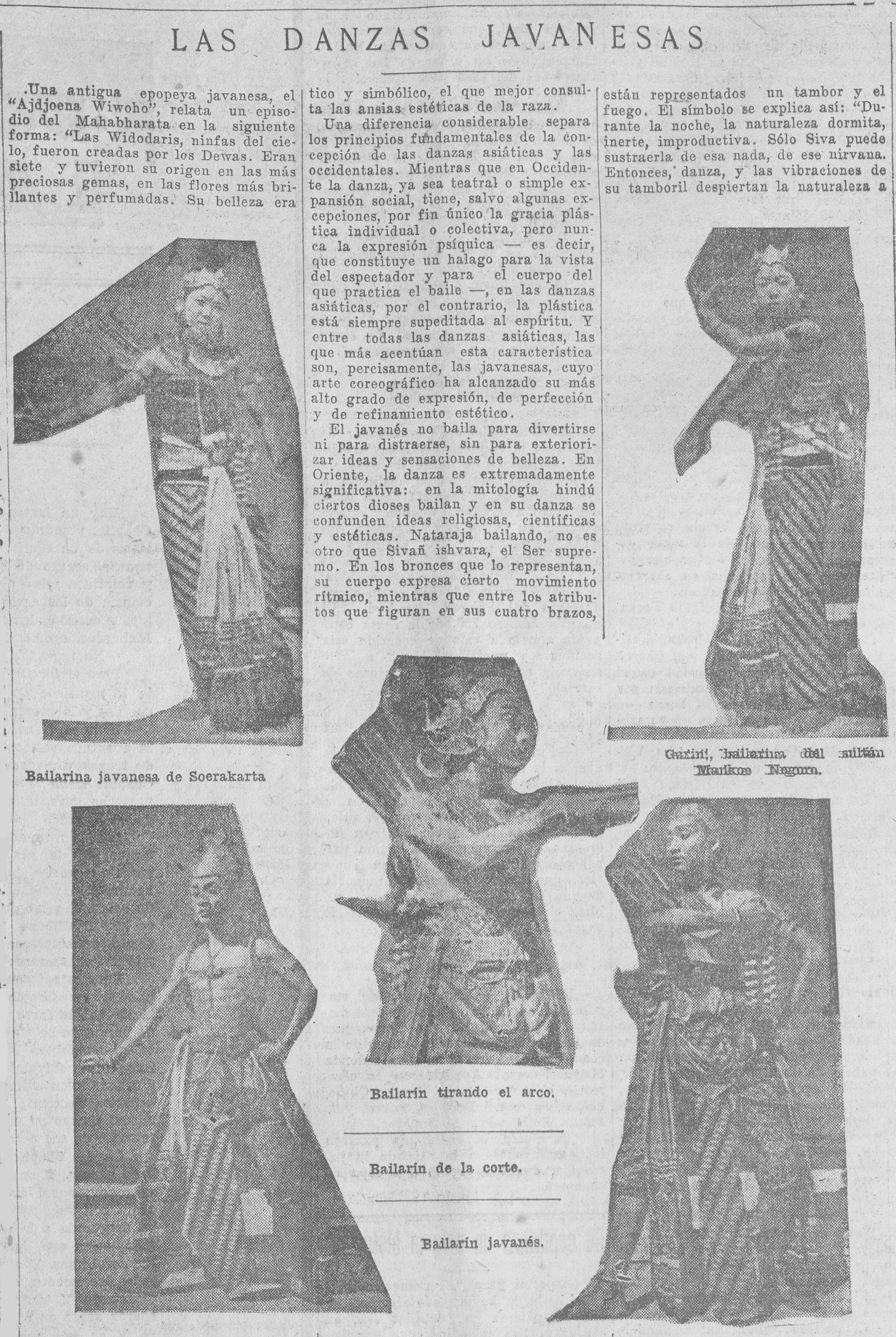

The author also went into further detail regarding the symbolism of the dancers’ hand positions and how they related to the Buddha, thus underscoring the incommensurability of Javanese and Western performance while also blending Hinduism and Buddhism into a single mélange of exoticism and Otherness. Perhaps as a way to compensate for their readers’ inability to see the dancers themselves, the article included several images of Javanese dancers in different poses, inviting the reader to imagine them in motion (Figure 3). The author of ‘El teatro en el extranjero’ also highlighted the religious nature of Javanese shadow theatre, focusing on the representation of the Buddha, Prajnaparamita, and other ‘Hindustanic idols’, who, due to the pernicious influence of local ‘Pagan ideas’, were depicted with ‘a horrific aspect, with eyes shaped like lotus flowers, threatening teeth and bristling claws and hair’.Footnote 87 Nevertheless, and despite the backhandedness of their opening salvo, they found much to praise in Javanese performing arts, a reflection of those ‘radically bipolar’ modernista writers that Camayd-Freixas writes about.Footnote 88 In their writing, the dalang (puppeteer) handled the wayang (puppets) ‘dexterously’, and the brightly coloured puppets were deemed ‘true works of art’. They praised the depictions of horses, elephants, turtles, and other animals, as well as the luxuriously painted textiles. They even commended the Javanese audience, which they described as ‘one of the most attentive and respectful in the world’.Footnote 89 In this respect, it is unclear whether the author had actually attended a performance, as they made no reference to the bawdy jokes that the dalangs often included in their plays—or perhaps they discreetly overlooked them.Footnote 90

Figure 3. Javanese dances. ‘Las danzas javanesas, El Comercio, 18 March 1928, 13. Biblioteca Nacional del Perú.

While these texts might not have encouraged their readers to identify with the colonisers of the Dutch East Indies, there were two fields in which a latent desire for domination manifested itself, the first of which was the longing for eroticised Oriental women. As previously established, one of the traits of modernismo was the impulse to eroticise Asian culture and reference the sensuality of Asian women. In this sense, while such eroticism was indeed present in passages of Arjunawiwaha (and Mahabharata),Footnote 91 the author of ‘Las danzas javanesas’, by choosing to insert it into their very concise summary of Arjunawiwaha, reinforced their readers’ Orientalist prejudices. Thus, they described the bidadaris as ‘dressed only in transparent fabrics that flowed from their perfect bodies’ and commented on ‘their soft motions and gestures’.Footnote 92 The Spanish author of ‘El teatro en el extranjero’ described a ‘Java, where the bodies of women have a serpentine agility and the men carry daggers in the form of a serpent …’, and where ‘there are also erotic images and goddesses—reminiscent of Venus—surrounded by nymphs who play the main role in the imagination of both male and female spectators’.Footnote 93

As part of the Orientalist imagination, it is the female body that attracts the male gaze, a female body that is presumed to welcome the sexual advances of Western men. Asian men have objects (such as the kris), but the female Asian body is the object to be described in detail. Naturally, depictions of both share an essentialist outlook of sex, neither addressing the matter of cross-gender performance.Footnote 94 Asian women were reconstituted as consumer goods for Western men. There certainly is a continuity between this rhetoric and that used by Pablo Neruda when describing his sexual assault of an Asian woman, whom he described as ‘a dark, walking statue, the most beautiful woman I had seen till then in Ceylon. She wore a red and gold sari … Her incredibly thin waist, her full hips, the full cups of her breasts made her the same as the thousand-year-old statues of southern India’.Footnote 95 Sensuous descriptions of erotic Asian women were not just that: they encouraged a Western male imagination of possessing such bodies.

The other field in which domination of the Oriental was unleashed was that of its exotic fauna. The author of ‘El teatro en el extranjero’ matched the perceived exoticism of the tropics with an equally flowery language:

Java, the prodigious isle, the most florid oasis where the heart—according to a phrase by the Russian Balmont—sings in unison with the nighttime fireflies, undulating clarities that offer to the eyes a concert of visions, where the soul trembles when the lizards elevate their cries of crepuscular gnomes: ‘Gueekko!’Footnote 96

Blanco’s ‘Descubrimiento y captura del famoso “dragón javanés”’ revealed the greatest exoticisation of ‘Javanese’ fauna and its interaction with tropes of White male agency and indigenous indolence and anonymity. In Blanco’s chronicling of the Douglas Burden expedition, which sought to capture a Komodo dragon, the eponymous Burden recruited a series of determined fellow White men, namely a Professor Dunn and a dashing French hunter named Monsieur Defosse. Burden’s wife appeared in the role of her husband’s assistant, while a Chinese Singaporean photographer went unnamed. The tale was full of wonder for the exotic wildlife of the Dutch East Indies, but the emphasis lay on the decisiveness and ease with which the White protagonists achieved their objectives; they even discovered Komodo dragon eggs immediately upon disembarking on the beach. Soon thereafter, they shot the first specimen, upon which Dr. Burden, displaying his Western expertise, brought the species into existence by uttering its new name out loud, ‘Varanus Komodoensis’. Afterwards, despite never having seen the animal before, he shared several facts about the Komodo dragon, namely, its agility, courage, carnivorousness, and claws, never mentioning his sources. He added that there are two subspecies of Komodos, those that inhabit the shore and those who inhabit the sea.Footnote 97

The tale was full of Orientalist tropes that flew in the face of reality. To begin with, local peoples were well aware of the existence of the Komodo dragon: they brought its existence to the attention of Dutch officials in the 1910s. Furthermore, the Dutch colonial government itself had sent an expedition to Komodo to ‘discover’ the animal, which had already resulted in a scientific article.Footnote 98 The Dutch Governor General even offered Burden material aid.Footnote 99 Burden’s ‘discovery’ was no such thing, but consumer demand for Orientalist narratives required Blanco to frame it within the expected trope of brave White men discovering a previously unknown species. Readers were encouraged to identify with the Western man who daringly explored the wonders of the world. Indigenous peoples’ knowledge was either ignored or presumed to be non-existent, which was in turn predicated on the assumption of their indolence in exploring even their immediate surroundings.Footnote 100

These narratives about dance, theatre, and wildlife in ‘Java’, especially when contrasted with the news coming out of the Philippines, give us insight into the ways in which Southeast Asian subjects were Orientalised. Southeast Asians were rarely, if ever, named; by remaining anonymous, they were cast, at best, as keepers of ancient traditions but with no individuality or innovation of their own. As full of praise as they may have been for Javanese dance, the author of ‘Las danzas javanesas’ did not name a single Javanese dancer or choreographer in their text; only in the captions for attending pictures (most of which simply said ‘Javanese dancer’ or some variation thereof) did one of them appear by name: Garini. Yet she displayed no individuality; she was an afterthought. For their part, the author of ‘El teatro en el extranjero’ was also full of praise for the dalangs of ‘Javanese’ wayang, but they did not name a single one. Blanco was particularly egregious in this respect, naming all the members of the Burden expedition except Lee Fai, the Singaporean photographer.Footnote 101 The labourers who were coerced into accompanying the expedition, and who arguably did most of the work, were also homogenised and anonymised, with Blanco referring to them all simply as ‘indigenous Javanese’. (The original report identified them as Labuan Bajau, Sulawesi, and Sapi—much like culture or fauna, these individuals were also ‘Javanised’.)Footnote 102 The silencing of names and identities reinforced among Peruvian readers the idea that most Asians were, indeed, an indistinguishable mass with little individuality. Even the isolated case of Garini made little impact. Who was she as an artist? What were her contributions to Javanese dance? Those were left unstated. This stood in stark contrast with Filipinos with Hispanic names, whose specific contributions to the Philippine independence movement could be pictured by readers in Peru.

Conclusions

Peruvian Orientalism was not monolithic. Its multiple strands were conditioned by specific historical phenomena: the presence of significant Asian communities in Peru and the historical trajectories of Spanish colonisation. In this manner we have seen how the most visible Asian immigrant community in Peru, the Chinese, triggered the rise of the predominant strain of Peruvian Orientalism, one that was characterised by hostility and which targeted local Chinese for derision and reform. With no significant Southeast Asian community in Peru, however, stark contrasts emerged. Regarding the Philippines, its shared history of Spanish colonisation led to an image that did not appear Oriental at all to Peruvian readers. Their elites had Spanish-sounding names that the Peruvian reading public could access and imagine as educated Catholics much like themselves. Even Orientalising imagery distributed by the United States, such as those of fanatical Catholics or of the non-Christian peoples of the Philippines, would not necessarily move the needle for fellow Catholic Peruvians who were also engaging in their own ‘civilising mission’ in the country’s eastern rainforests. The rest of Southeast Asia, however, would give way to an older ‘medieval-colonial’ tradition of an Orientalism of enchantment that leaned into fascination with the wonders of the Orient. Peruvian readers were invited to marvel at the opulence of emperor Khải Định, the refinement of Javanese performing arts, the eroticism of Southeast Asian women, and the exotic tropical wildlife of the region. At the same time, as much fascination as may have been encouraged, most of these Southeast Asians were homogenised, flattened, and made anonymous in these writings.

While many literary writers may have, as pointed out by Kushigian, shown fascination and respect for the Oriental other, it is in the press where we see how variegated responses could be, whereby medieval-colonial Orientalism could coexist with the more modern, domineering Orientalism. These various strands of Orientalism (or lack thereof) came together in a way that allows us to further nuance our understanding of the articulation of popular Orientalism in those regions that did not colonise or intervene significantly in Asia, yet whose elites often identified themselves as ‘Western’ and could sympathise with the colonial powers’ ‘civilising mission’.

While the post-early modern global history of Latin America is a growing field, Peru may still be lagging somewhat in this respect. By bringing the country into the discussion of the global history of Orientalism through a focus on the oft-overlooked region of Southeast Asia, this article contributes to filling that gap. The study of essays and reports in the press allows us to gain a clearer understanding of how broader Peruvian reading publics engaged with global trends of representation of the ‘Orient’ in general and Southeast Asia in particular. By showing how specific historical conjunctures of migration and colonisation could lead to the coexistence of different strands of Orientalisms (or non-Orientalism) within a single society, this article points out research directions in other Latin American societies in which these factors intersected in different ways. A broader, more nuanced history of Orientalism in Latin America, one that reaches beyond the literary production of brilliant individuals, may result from these efforts.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to acknowledge the institutional support of the Asia Research Institute of the National University of Singapore, where a large part of the work for this article was completed, as well as that of the Center for Southeast Asian Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. He would also like to thank Desiana Pauli Sandjaja and Kelly Van Acker for their valuable feedback on this article.

Financial support

None to declare.

Competing interests

The author declares none.

Jorge Bayona is a profesor-investigador at the rank of Assistant Professor at the Centro de Estudios de Asia y África at El Colegio de México. He received his PhD in History from the University of Washington, Seattle, and held a post as a Postdoctoral Fellow at the Asia Research Institute of the National University of Singapore.