Introduction

Severe childhood adversity accounts for a large portion of psychiatric illness and increases the risk for major depressive disorder (MDD) (Green et al., Reference Green, McLaughlin, Berglund, Gruber, Sampson, Zaslavsky and Kessler2010). Individuals who develop MDD following childhood maltreatment endure a more pernicious illness course characterized by longer chronicity, recurrent episodes, and unfavorable treatment outcomes (Garcia-Toro et al., Reference Garcia-Toro, Rubio, Gili, Roca, Jin, Liu and Blanco2013; Nanni, Uher, & Danese, Reference Nanni, Uher and Danese2012; Wiersma et al., Reference Wiersma, Hovens, Van Oppen, Giltay, Van Schaik, Beekman and Penninx2009; Zlotnick, Mattia, & Zimmerman, Reference Zlotnick, Mattia and Zimmerman2001).

Recent models posit that specific maltreatment subtypes occurring during certain developmental windows have uniquely potent impacts on psychopathological outcomes (McLaughlin & Sheridan, Reference McLaughlin and Sheridan2016; Schaefer, Cheng, & Dunn, Reference Schaefer, Cheng and Dunn2022). These type- and timing-specific effects are corroborated by research on mechanisms underlying the neurobiological embedding of adversity, as critical developmental windows have been identified during which distinct types of maltreatment maximally impact brain development (Pechtel, Lyons-Ruth, Anderson, & Teicher, Reference Pechtel, Lyons-Ruth, Anderson and Teicher2014; Zhu et al., Reference Zhu, Lowen, Anderson, Ohashi, Khan and Teicher2019). Examining the developmental trajectory of maltreatment exposure and identifying these critical exposure periods can also increase our understanding of resilience to future psychopathology. Moreover, identifying ages at which certain adverse experiences are most strongly associated with future depression can have important implications for more targeted and timely prevention and intervention efforts.

Among the different subtypes of maltreatment, childhood sexual abuse (CSA) has emerged as a salient predictor of MDD, with over 60% of adults meeting diagnostic criteria following CSA (Li, D'Arcy, & Meng, Reference Li, D'Arcy and Meng2016; Noll, Reference Noll2021; Teicher, Samson, Polcari, & Andersen, Reference Teicher, Samson, Polcari and Andersen2009). Moreover, women who experienced CSA are more likely to report additional childhood maltreatment subtypes relative to women who did not experience CSA (Lacelle, Hébert, Lavoie, Vitaro, & Tremblay, Reference Lacelle, Hébert, Lavoie, Vitaro and Tremblay2012). This finding is of clinical importance since exposure to multiple concurrent types of childhood maltreatment, particularly in adolescence, has been associated with greater risk, severity, and chronicity of subsequent depression (Lumley & Harkness, Reference Lumley and Harkness2007; Negele, Kaufhold, Kallenbach, & Leuzinger-Bohleber, Reference Negele, Kaufhold, Kallenbach and Leuzinger-Bohleber2015; Widom, DuMont, & Czaja, Reference Widom, DuMont and Czaja2007). CSA was particularly associated with emotional maltreatment from both parents and peers (Bailey, Baker, McElduff, & Kavanagh, Reference Bailey, Baker, McElduff and Kavanagh2016; Kennedy, Font, Haag, & Noll, Reference Kennedy, Font, Haag and Noll2022; Tremblay-Perreault & Hébert, Reference Tremblay-Perreault and Hébert2020). Childhood emotional maltreatment encapsulates both threat (e.g. the child is the target of verbal threats from parents or experiences bullying from peers) and/or deprivation (e.g. parents are emotionally unavailable or do not serve as a source of strength and support to the child) experiences, both of which adversely impact development (McLaughlin & Sheridan, Reference McLaughlin and Sheridan2016; Teicher & Parigger, Reference Teicher and Parigger2015). Like CSA, exposure to emotional maltreatment subtypes has been strongly associated with the development of future depression (Radell, Abo Hamza, Daghustani, Perveen, & Moustafa, Reference Radell, Abo Hamza, Daghustani, Perveen and Moustafa2021; Steine et al., Reference Steine, Winje, Krystal, Bjorvatn, Milde, Grønli and Pallesen2017).

Childhood emotional maltreatment is the most common adverse childhood experience, and its incidence in the US has increased over time; however, its effects have historically been understudied in comparison to sexual and physical abuse (Swedo et al., Reference Swedo, Aslam, Dahlberg, Niolon, Guinn, Simon and Mercy2023; Trickett, Mennen, Kim, & Sang, Reference Trickett, Mennen, Kim and Sang2009). Furthermore, the type- and timing-specific effects of emotional maltreatment subtypes on future depressive symptomatology, specifically in women with CSA, have not been investigated. Given the incidence of childhood emotional maltreatment endorsed by women with CSA, as well as the demonstrated relationship between CSA and emotional maltreatment on future depression, it is important to identify the critical ages during which emotional maltreatment most strongly predicts depressive outcomes in women with CSA.

The present study aimed to investigate the relationship between experiences of childhood emotional maltreatment and CSA on subsequent depressive symptoms in women. First, we examined differences in multiplicity of maltreatment, severity of overall maltreatment, and exposure to distinct emotional maltreatment subtypes (parental verbal abuse, parental non-verbal emotional abuse, peer verbal abuse, and emotional neglect). We predicted that women with depressive symptoms (current or past) who experienced CSA would report greater severity of overall maltreatment characteristics (multiplicity, sum, and duration of maltreatment) as well as greater severity of emotional maltreatment, relative to women with current depressive symptoms without CSA. Second, we characterized the developmental time course of exposure to emotional maltreatment subtypes for women with depressive symptoms (current or past) and with or without CSA. Last, machine learning predictive modeling was used to identify the most important emotional maltreatment subtypes and ages for predicting future depressive symptoms in women with current depressive symptoms with and without CSA.

Materials and methods

Sample and study design

Women were recruited in the context of a larger neuroimaging project investigating the functional and molecular effects of CSA between the ages of 11–18 years on depression (R01 MH095809). Women were recruited from the greater Boston area primarily through advertisements on social media platforms and local college job boards. The data for the present analyses came from participants who completed the first stage of the larger neuroimaging project. Participants first completed a self-report survey that included the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) (Beck, Steer, & Brown, Reference Beck, Steer and Brown1996), as well as demographic and other information about their current and past medical and psychiatric history (see online Supplemental Methods for a full list of inclusion and exclusion criteria). Next, eligible participants completed the 75-item Maltreatment and Abuse Chronology of Exposure (MACE) (Teicher & Parigger, Reference Teicher and Parigger2015) to obtain a history of childhood maltreatment. Self-report survey and MACE data were collected using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at Massachusetts General Brigham (MGB) (Harris et al., Reference Harris, Taylor, Thielke, Payne, Gonzalez and Conde2009, Reference Harris, Taylor, Minor, Elliott, Fernandez and O'Neal2019). Prior to enrollment, participants provided electronic informed consent. The study was approved by and conducted in accordance with the MGB and McLean Hospital Institutional Review Board (Protocol Number: 2020P001470).

Based on the BDI-II, MACE, and phone screening, participants were categorized into three groups: (i) current depressive symptoms and CSA between the ages of 11 and 18 years (MDD/CSA), (ii) past depression without current depressive symptoms, and CSA between the ages of 11 and 18 years (rMDD/CSA), and (iii) current depressive symptoms without a history of CSA (MDD/no CSA).

Current and past depressive symptomatology

The BDI-II was used to assess depressive symptoms over the past 2 weeks. Although this instrument has 21 questions, the suicidality question was removed due to the online nature of the questionnaire, so total scores were computed by summing the remaining 20 questions. Participants' current and past depressive symptoms were confirmed in a 30-minute phone screening conducted by trained clinical research assistants at McLean Hospital. Questions regarding current and past depressive symptomatology closely mirrored the MDD module of the mood disorders section of the research version of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 (SCID-5-RV) (First, Williams, Karg, & Spitzer, Reference First, Williams, Karg and Spitzer2015).

Participants with current depressive symptoms endorsed at least five symptoms of MDD at a clinically significant level in the past 2 weeks and had a BDI score ⩾14. Participants with past depressive symptoms reported no depressed mood or anhedonia in the past 2 months, in addition to either (i) one period of at least 2 months or (ii) two separate periods of at least 2 weeks in the past 5 years where the participant endorsed at least five symptoms of MDD at a clinically significant level. They also had a current BDI-II score <14. Importantly, all participants across groups were not taking psychotropic medication at the time of enrollment.

Childhood maltreatment exposure

A detailed maltreatment history between ages 1 and 18 years was assessed using the MACE, which evaluates the severity of the following 10 maltreatment subtypes at each age: sexual abuse, parental verbal abuse, parental non-verbal emotional abuse, parental physical abuse, witnessing abuse of siblings, witnessing interparental violence, peer verbal abuse, peer physical abuse, emotional neglect, and physical neglect.

The following global measures of maltreatment were computed:

i Maltreatment multiplicity (MULT): the number of different significant subtypes of maltreatment which the participant endorsed, ranging from 0 to 9 (sexual abuse was not included in the multiplicity score to enable comparison between women with and without CSA). Each maltreatment subscale has a numerical threshold that indicates significant exposure to that specific subtype (Teicher & Parigger, Reference Teicher and Parigger2015). For every subtype, the severity was computed by summing the number of items endorsed between ages 1 and 18 years. If the severity score reached the threshold for that subtype, it was considered a significant exposure.

ii Total maltreatment severity (SUM): the sum of the severity scores on the MACE maltreatment subscales (excluding CSA) across the ages of 1–18 years, ranging from 0 to 90.

iii Total maltreatment duration: the number of years (ranging from 0 to 18 years) of significant exposure to at least one type of maltreatment, excluding CSA (i.e. the number of years where MULT > 0).

Sexual abuse assessment

The MACE includes 12 items assessing sexual abuse by parents or adults living in the house, adults living outside the house, or peers: 2 items addressing non-contact sexual abuse (e.g. inappropriate sexual comments) and 10 items addressing contact sexual abuse. For this study, the endorsement of any contact sexual abuse item between the age of 11 and 18 years was considered substantial sexual abuse exposure. This age range was selected due to the parent study's focus on the neurodevelopmental impact of maltreatment during adolescence. Note that the MACE's original criteria for significant sexual abuse slightly differ and required endorsement of two items from a smaller subset of questions (Teicher & Parigger, Reference Teicher and Parigger2015) (see online Supplemental Methods).

Duration of sexual abuse was defined as the number of years in which at least one contact sexual abuse item was endorsed between ages 11 and 18. Participants reporting any contact sexual abuse prior to the age of 11 were excluded from analyses.

Chronologies of emotional maltreatment

Chronologies of emotional maltreatment were derived using the MACE severity scores for each age and subtype: parental verbal abuse (PVA), parental non-verbal emotional abuse (NVEA), peer verbal abuse (PEERVA), and emotional neglect (EN). Chronology of total emotional maltreatment severity was created by summing the severity scores for the four subtypes at each age.

Statistical analyses

Sexual abuse characteristics

Differences between MDD/CSA and rMDD/CSA women with respect to number of CSA perpetrators and duration of CSA was endorsed were analyzed using independent-samples t tests. Differences between these two groups with respect to prevalence of CSA perpetrator relationships (i.e. adult in the house, adult outside the house, or peer) were analyzed using χ2 tests.

Between-group differences in maltreatment exposure

Analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 28.0.0.0) (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and R. Differences in the global maltreatment measures were examined using one-way ANCOVA models implemented by a GLM with group as a between-subject factor. Differences in the prevalences of maltreatment subtypes were evaluated using χ2 tests. Differences in total emotional maltreatment severity were evaluated using a two-way mixed ANCOVA with group as a between-subject factor and emotional maltreatment (PVA, NVEA, PEERVA, and EN) as a within-subject factor. Differences in emotional maltreatment severity at each age between 1 and 18 years old were evaluated using a two-way mixed ANCOVA with group as a between-subject factor and age of maltreatment as a within-subject factor. Current age, race, ethnicity, and education were included as covariates.

Random forest regression with conditional interference trees

Random forest regression with conditional interference trees (‘cforest’ in R package party) (Strobl, Boulesteix, Zeileis, & Hothorn, Reference Strobl, Boulesteix, Zeileis and Hothorn2007) was used to examine the importance of type and timing of emotional maltreatment for current depressive symptom severity in MDD/no CSA and MDD/CSA women. This machine learning strategy is robust for detecting important predictors from a large number of predictors (Breiman, Reference Breiman2001; Liaw & Wiener, Reference Liaw and Wiener2002; Svetnik et al., Reference Svetnik, Liaw, Tong, Culberson, Sheridan and Feuston2003). It has also demonstrated resistance to collinearity, which is important given the substantial collinearity in the severity of maltreatment exposure at adjacent ages (Breiman, Reference Breiman2001). This approach has previously been used in similar analyses of sensitive periods in which maltreatment maximally predicted psychopathology and neurodevelopmental disruption (Gokten & Uyulan, Reference Gokten and Uyulan2021; Herzog et al., Reference Herzog, Thome, Demirakca, Koppe, Ende, Lis and Schmahl2020; Schalinski et al., Reference Schalinski, Teicher, Nischk, Hinderer, Müller and Rockstroh2016, Reference Schalinski, Breinlinger, Hirt, Teicher, Odenwald and Rockstroh2019; Zhu et al., Reference Zhu, Lowen, Anderson, Ohashi, Khan and Teicher2019). This analysis was conducted using in-house software written in R (by M. H. T).

PVA, NVEA, PEERVA, and EN at ages 1–18 were used as predictors. Additional MACE maltreatment subtypes (e.g. physical abuse) were not used as predictors in this model since this investigation specifically focused on emotional maltreatment. Current age, race, ethnicity, and education were accounted for as covariates. Importance was defined as the mean increase in the mean square error of the overall model fit following permutation of each independent variable. Significance was assessed using a non-parametric test that treats the array of predictors as a composite and yields a measure that controls for multiple comparisons.

Relative variable importance (VI) values for each predictor were derived to examine sensitivity by type and timing. The null hypothesis was that the VI of global MACE measures was greater than the VI of exposure to a specific emotional maltreatment subtype at a specific age. This hypothesis would be rejected if the VI of exposure to a specific maltreatment subtype surpassed the VI of both MACE MULT and SUM.

Results

Sample characteristics

Between March 2020 and July 2023, N = 3364 women completed the self-report recruitment survey. Of these respondents, 1081 were invited to complete the phone screening to further assess eligibility, and 567 women completed this assessment. In total, 247 women were eligible on the phone screening and were sent the MACE to gather a detailed maltreatment history, and 234 of these women completed the MACE. Seventeen women were excluded for endorsing CSA before age 11, and three MDD/no CSA women were excluded for endorsing witnessing CSA of their sibling. Five rMDD women were excluded for not endorsing contact CSA. Finally, six women were excluded for incomplete BDI-II scores. A study enrollment chart and detailed parent study exclusion criteria can be found in the online Supplemental Methods. The final analyzed sample comprised 203 women: 69 MDD/CSA, 21 rMDD/CSA, and 113 MDD/no CSA (Table 1). Groups were matched for age, race, ethnicity, and highest level of education completed.

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample

BDI, Beck Depression Inventory II.

MDD/CSA participants reported more severe current depressive symptoms (BDI) than MDD/no CSA women (Sidak; p = 0.007).

Sexual abuse characteristics

Of the participants reporting CSA between 11 and 18 years old (MDD/CSA and rMDD/CSA; N = 90), 61.1% of women (N = 55) reported CSA perpetrated by a peer their own age or older, 56.7% of women (N = 51) reported CSA perpetrated by an adult not living in the house, and 11.1% of women (N = 10) reported CSA perpetrated by parents/adults living in the house. Notably, all women who endorsed CSA from an adult or older individual living in their home were in the MDD/CSA group. Additionally, MDD/CSA women more commonly reported CSA from a peer relative to rMDD/CSA women (76.7 and 23.3%, respectively) (χ2 = 6.11; p = 0.013).

In total, 24.4% of women (N = 22) reported CSA from multiple perpetrators during this age range. MDD/CSA women endorsed having experienced CSA from a greater number of perpetrators compared to rMDD/CSA women (t[85.047] = 3.82, p < 0.001). Finally, 68% of women (N = 53) reported CSA at more than one age. The average duration of CSA was 2.51 ± 1.62 years for MDD/CSA women and 1.86 ± 1.01 years for rMDD/CSA women, which was not significantly different between groups (t[88] = 1.73, p = 0.087). A table of sexual abuse characteristics can be found in online Supplemental Table S1.

Global measures of childhood maltreatment between 1 and 18 years old

Multiplicity of maltreatment (MULT)

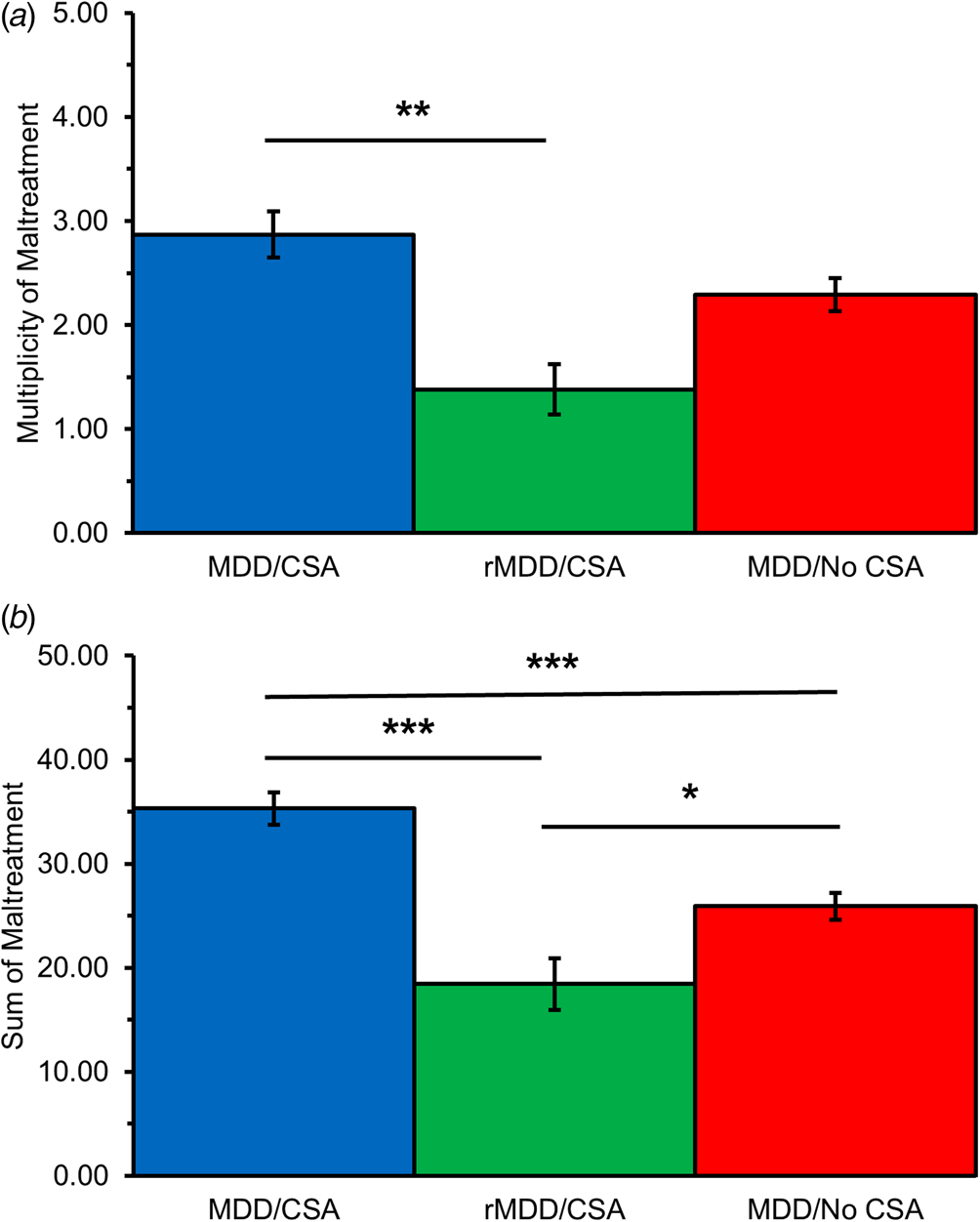

Significant differences in multiplicity of maltreatment between the ages of 1 and 18 years (excluding CSA) were reported among groups (F [2,196] = 5.60, p = 0.004, ηp2 = 0.056) (Fig. 1a). Specifically, MDD/CSA women reported greater multiplicity of maltreatment relative to rMDD/CSA women (Sidak; p = 0.003; 95% CI [3.750–2.399]). Education was a significant covariate (F [1,191] = 9.91, p = 0.002, ηp2 = 0.049).

Figure 1. Between-group differences in MACE global measures of maltreatment. (A) MDD/CSA women reported greater multiplicity of maltreatment than rMDD/CSA women. (B) MDD/CSA women reported greater severity of maltreatment than rMDD/CSA women and MDD/No CSA women. MDD/No CSA women also reported greater severity of maltreatment than rMDD/CSA women. Significance: *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Severity of maltreatment (SUM)

Significant differences in total severity of maltreatment between 1 and 18 years old emerged across groups (F [2,191] = 15.90, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.143) (Fig. 1b). MDD/CSA women reported greater severity relative to rMDD/CSA women (Sidak; p < 0.001; 95% CI [8.462–23.995]) and MDD/no CSA women (Sidak; p < 0.001; 95% CI [3.599–13.404]). In addition, MDD/no CSA women reported greater severity of maltreatment relative to rMDD/CSA women (Sidak; p = 0.031; 95% CI [0.164–15.291]). Race and education were significant covariates (F [1,196] = 4.52, p = 0.035, ηp2 = 0.025 and F [1,191] = 8.34, p = 0.004, ηp2 = 0.042, respectively).

Duration of maltreatment

There were no significant between-group differences in duration of maltreatment. Race and education were significant covariates (F [1,196] = 4.10, p = 0.044, ηp2 = 0.050 and F [1,196] = 10.18, p = 0.002, ηp2 = 0.051, respectively).

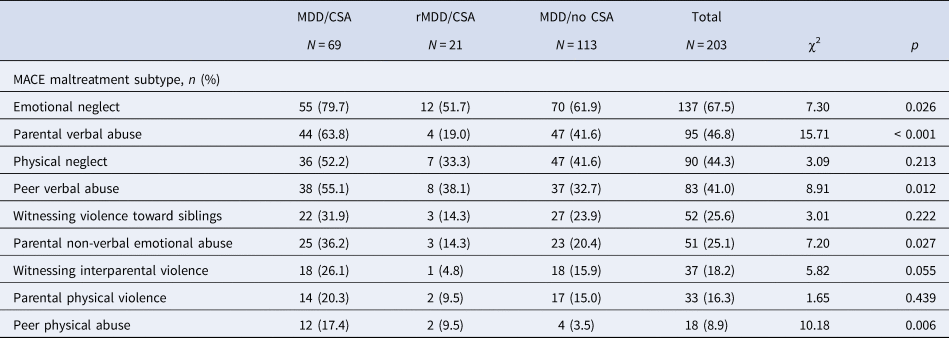

Maltreatment subtype prevalence

Table 2 presents the prevalence of significant exposure to maltreatment subtypes for each group. MDD/CSA women reported higher prevalence of significant exposure to emotional maltreatment subtypes, including PVA (χ2 = 15.71; p < 0.001), PEERVA (χ2 = 8.91; p = 0.012), EN (χ2 = 7.30; p = 0.026), and NVEA (χ2 = 7.20; p = 0.027), in addition to higher prevalence of peer physical abuse (χ2 = 10.18; p = 0.006) compared to MDD/no CSA and rMDD/CSA women.

Table 2. MACE maltreatment subtype prevalence between 1 and 18 years old

Comparisons of significant exposure to nine MACE maltreatment subtypes between groups. MDD/CSA women were more likely to report significant exposure to emotional neglect, parental verbal abuse, peer verbal abuse, parental non-verbal emotional abuse, and peer physical abuse than rMDD/CSA and MDD/no CSA women. Significant exposure was defined as severity meeting or exceeding the severity threshold for each maltreatment subtype on the MACE. MACE, Maltreatment and Abuse Chronology of Exposure.

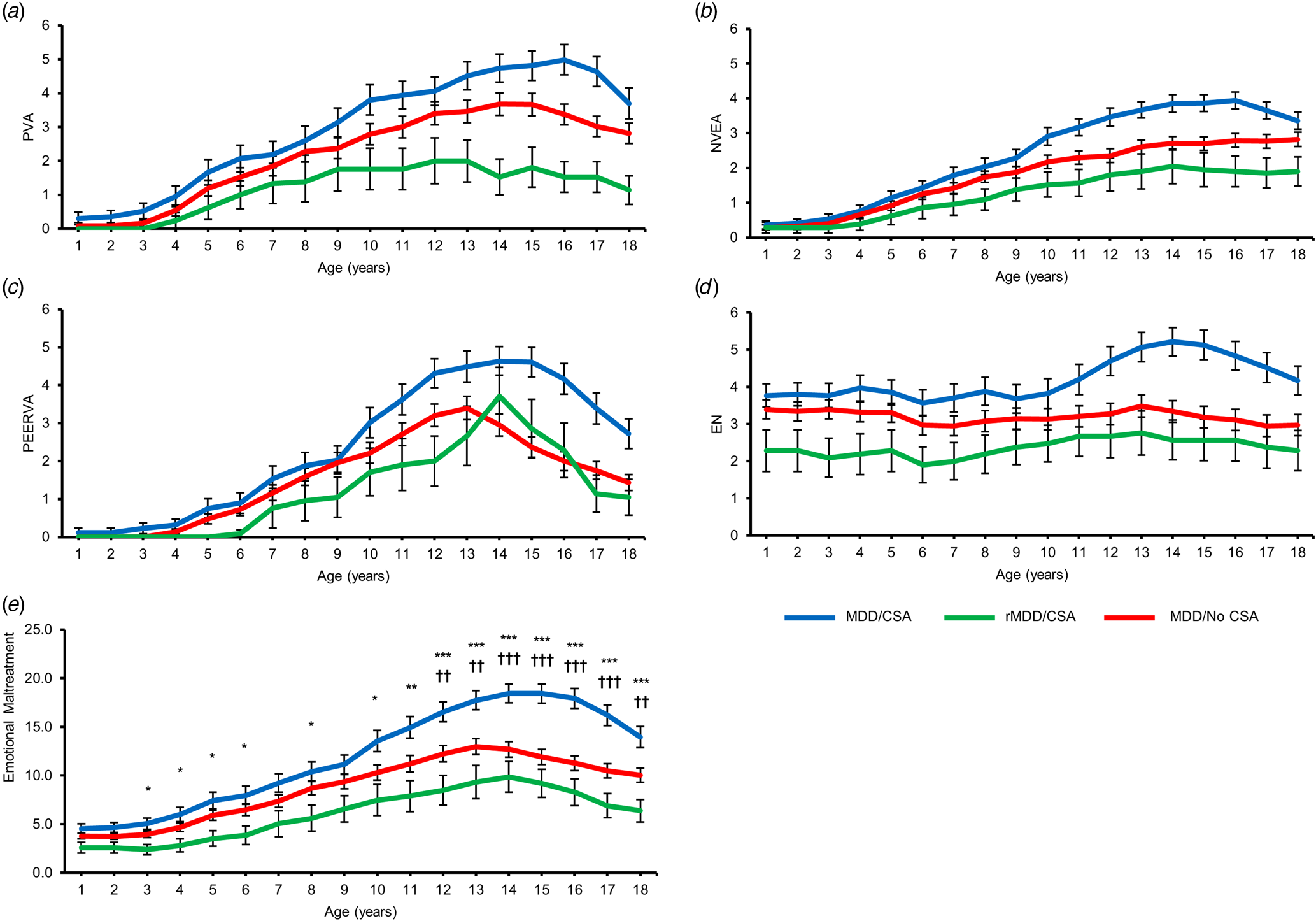

Women with current depressive symptoms and CSA report greater severity of emotional maltreatment

There were significant between-group differences in emotional maltreatment severity (F [2,196] = 17.60, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.152). Across emotional maltreatment subtypes (PVA, NVEA, PEERVA, and EN), MDD/CSA women reported greater emotional maltreatment severity compared to MDD/no CSA women (Sidak; p < 0.001; 95% CI [0.653–2.147]) and rMDD/CSA women (Sidak; p < 0.001; 95% [1.440–3.853]). MDD/no CSA women also reported greater emotional maltreatment severity compared to rMDD/CSA women (Sidak; p = 0.029; 95% CI [0.095–2.397]). Education was a significant covariate (F [1,196] = 9.98, p = 0.002, ηp2 = 0.048).

For total emotional maltreatment, a group-by-age interaction emerged (F [7.619,746.637] = 5.13, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.050) in addition to a significant main effect of group (F [2,196] = 9.33, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.087) (Fig. 2e). MDD/CSA women reported greater total emotional maltreatment relative to rMDD/CSA women (Sidak; p < 0.001; 95% CI [2.263–9.181]) and MDD/no CSA women (Sidak; p = 0.007; 95% CI [0.587–4.868]). A main effect of age was also found (F [3.809,746.637] = 2.50, p = 0.044, ηp2 = 0.013, Greenhouse–Geisser corrected). Sidak-corrected post-hoc tests revealed that MDD/CSA women reported greater emotional maltreatment than rMDD/CSA women at ages 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 10, and 11 and greater emotional maltreatment than both rMDD/CSA and MDD/no CSA women from ages 12 to 18. Online Supplemental Table S1 presents the significant pairwise differences for each age.

Figure 2. Chronology of emotional maltreatment (PVA, NVEA, PEERVA, and EN) severity and age-specific severity differences. (A) Severity of exposure to parental verbal abuse (PVA) between 1-18 years old. (B) Severity of exposure to parental non-verbal emotional abuse (NVEA) between 1-18 years old. (C) Severity of exposure to peer verbal abuse (PEERVA) between 1-18 years old. (D) Severity of exposure to emotional neglect (EN) between 1-18 years old. (E) MDD/CSA women reported greater severity of total emotional maltreatment than rMDD/CSA women (Sidak; p < .001) and MDD/No CSA women (Sidak; p = .007). MDD/CSA women specifically reported greater severity of emotional maltreatment than MDD/No CSA and rMDD/CSA women from ages 12 to 18 years old. Significance for MDD/CSA and rMDD/CSA comparisons: *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001. Significance for MDD/CSA and MDD/No CSA comparisons: †p < .05, ††p < .01, †††p < .001. Abbreviations: PVA = Parental Verbal Abuse, NVEA = Parental Nonverbal Emotional Abuse, PEERVA = Peer Verbal Abuse, EN = Emotional Neglect.

Type- and timing-specific effects of emotional maltreatment subtypes

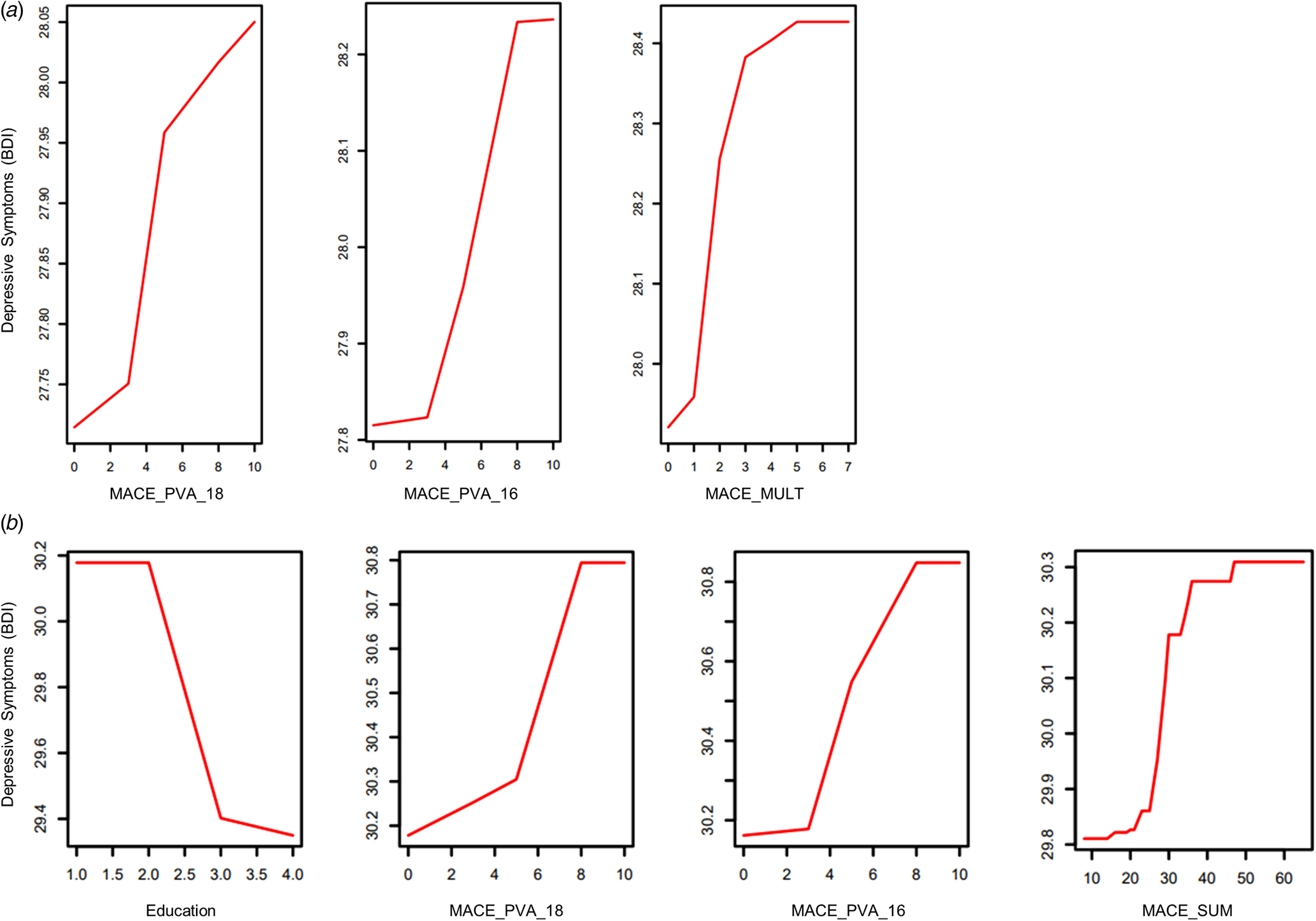

Figure 3 presents the dose–response curves of emotional maltreatment severity and depressive symptoms for the most important predictors identified by the random forest model. For MDD/no CSA women, the strongest predictor for depressive symptoms was parental verbal abuse at age 18 (VI = 0.68; p = 0.004), followed by parental verbal abuse at the age of 16 (VI = 0.56; p = 0.007) (Fig. 3a). Notably, this was a more important predictor than both MULT and SUM, although MULT was also a significant predictor for this group (VI = 1.09; p = 0.014).

Figure 3. Strongest predictors of depressive symptoms in MDD/No CSA and MDD/CSA women. Dose-response curves of emotional maltreatment severity and current depressive symptoms indicating importance of type and timing of maltreatment on current depressive symptoms derived from the random forest regression with conditional interference trees. (A) For MDD/No CSA women, the strongest predictors of depressive symptoms were PVA at age 18 (VI = 0.68; p = .004), PVA at age 16 (VI = 0.56; p = .007), and MACE MULT (VI = 1.09; p = .014). Depressive symptoms increased as severity of each of these maltreatment predictors increased. (B) For MDD/CSA women, the strongest predictors of depressive symptoms were highest level of education completed (VI = 1.34; p = .005), PVA at age 18 (VI = 1.08; p = .006), PVA at age 16 (VI = 1.14; p = .009), and MACE SUM (p = .012). Depressive symptoms decreased as the level of education completed decreased. Depressive symptoms increased as severity of maltreatment predictors (MACE_PVA_18, MACE_PVA_16, and MACE_SUM) increased. Abbreviations: PVA = Parental Verbal Abuse; MULT = Multiplicity; SUM = Total Severity.

For MDD/CSA women, the most important predictor for depressive symptoms was education (VI = 1.34; p = 0.005), with women who have completed a higher level of education reporting lower depressive symptoms (Fig. 3b). The second and third strongest predictors were parental verbal abuse at age 18 (VI = 1.08; p = 0.006) and at age 16 (VI = 1.14; p = 0.009). These were more important predictors than both MULT and SUM, although SUM was also a significant predictor for this group (VI = 1.09; p = 0.012).

Discussion

The current investigation aimed to delineate the developmental trajectory of exposure to emotional maltreatment and identify at which ages certain emotional maltreatment subtypes most strongly predict future depressive symptoms in women with CSA. Our results highlight significant exposure to emotional maltreatment from both parents and peers in both early childhood and throughout adolescence among women with CSA who later develop depressive symptoms. Importantly, parental verbal abuse in late adolescence had the strongest predictive strength of future depressive symptoms in women with current depressive symptoms with and without CSA.

Women with current depressive symptoms and CSA reported greater overall severity of maltreatment compared to both women with remitted depressive symptoms and CSA and women with current depressive symptoms without CSA. Women with current depressive symptoms and CSA specifically endorsed greater severity of emotional maltreatment from both parents and peers, which persisted from early childhood into adolescence. Significant childhood maltreatment spanning several developmental periods – as demonstrated by this sample – has been found to have stronger and more negative consequences cross-diagnostically (Manly, Kim, Rogosch, & Cicchetti, Reference Manly, Kim, Rogosch and Cicchetti2001; Russotti et al., Reference Russotti, Warmingham, Duprey, Handley, Manly, Rogosch and Cicchetti2021; Thornberry, Ireland, & Smith, Reference Thornberry, Ireland and Smith2001). Our findings bolster previous research indicating that women with CSA are more likely to report a multiplicity of maltreatment and specifically heightened emotional maltreatment compared to women without history of sexual abuse (Carey, Walker, Rossouw, Seedat, & Stein, Reference Carey, Walker, Rossouw, Seedat and Stein2008; Lacelle et al., Reference Lacelle, Hébert, Lavoie, Vitaro and Tremblay2012). Notably, our findings add to previous literature by identifying the specific ages of heightened emotional maltreatment for women with CSA who developed later depressive symptoms.

An effect of the current depressive state emerged for both global and emotional maltreatment, where women with current depressive symptoms reported greater maltreatment. One possible explanation is mood-congruent memory bias, where women are appraising their maltreatment experiences in light of their current depressive state, which is an important consideration given this study's association between current depressive symptoms and retrospective maltreatment experiences. However, self-reports of childhood maltreatment have demonstrated consistency over time and across major depressive episodes in young women, with changes in reporting unattributable to changes in psychological symptoms (Goltermann et al., Reference Goltermann, Meinert, Hülsmann, Dohm, Grotegerd, Redlich and Dannlowski2023; Pinto, Correia, & Maia, Reference Pinto, Correia and Maia2014). These findings are corroborated by a recent meta-analysis demonstrating the reliability of retrospective accounts of maltreatment compared to prospective accounts (Baldwin, Coleman, Francis, & Danese, Reference Baldwin, Coleman, Francis and Danese2024). Thus, a more likely possibility is that the impact of CSA on future depressive outcomes is worsened by exposure to emotional maltreatment and attenuated by strong relationships with both parents and peers. Although sexual abuse has been associated with non-remission from MDD and the persistence of chronic MDD (Enns & Cox, Reference Enns and Cox2005; Garcia-Toro et al., Reference Garcia-Toro, Rubio, Gili, Roca, Jin, Liu and Blanco2013; Hovens, Giltay, Van Hemert, & Penninx, Reference Hovens, Giltay, Van Hemert and Penninx2016), other studies have found that emotional maltreatment subtypes emerge as more important predictor variables for determining risk for MDD and symptom severity in women than both physical and sexual abuse (Martins, Von Werne Baes, De Carvalho Tofoli, & Juruena, Reference Martins, Von Werne Baes, De Carvalho Tofoli and Juruena2014; Teicher, Samson, Polcari, & McGreenery, Reference Teicher, Samson, Polcari and McGreenery2006). Positive familial and peer relationships have been associated with more rapid recovery as well as psychological resilience particularly following CSA (Domhardt, Münzer, Fegert, & Goldbeck, Reference Domhardt, Münzer, Fegert and Goldbeck2015; Fuller-Thomson, Lacombe-Duncan, Goodman, Fallon, & Brennenstuhl, Reference Fuller-Thomson, Lacombe-Duncan, Goodman, Fallon and Brennenstuhl2020; Marriott, Hamilton-Giachritsis, & Harrop, Reference Marriott, Hamilton-Giachritsis and Harrop2014). Specifically, peer social support in adolescence has been associated with lower levels of depression following childhood emotional maltreatment (Dong, Dong, Chen, & Yang, Reference Dong, Dong, Chen and Yang2023; Glickman, Choi, Lussier, Smith, & Dunn, Reference Glickman, Choi, Lussier, Smith and Dunn2021). The significant differences found here in the severity of diverse emotional maltreatment subtypes between women with current and remitted depression with CSA, particularly during adolescence, necessitate additional research on the mechanisms through which emotional maltreatment worsens depressive outcomes for women with history of CSA.

Highest level of education completed was identified as the strongest predictor of depressive symptoms in women with CSA, above emotional maltreatment at any specific age. Previous investigations of CSA and higher education have identified that the psychological consequences of CSA specifically at earlier ages of onset are associated with lower levels of educational achievement (Hardner, Wolf, & Rinfrette, Reference Hardner, Wolf and Rinfrette2018). Alternatively, adult women with the history of CSA have regarded their higher education as an important part of their healing process (LeBlanc, Brabant, & Forsyth, Reference LeBlanc, Brabant and Forsyth1996). Thus, earlier psychological intervention for CSA victims may minimize or alleviate these developmental disruptions such that they can attain the potential psychological benefits of higher education. Additional research is necessary to elucidate the specific relationships between psychological development and educational outcomes in women with CSA.

The endorsement of severe parental verbal abuse by women with depressive symptoms with and without CSA may have important implications for treatment of MDD. Although parental verbal abuse has been previously suggested to confer risk for internalizing disorders and other emotional problems (Sachs-Ericsson et al., Reference Sachs-Ericsson, Gayman, Kendall-Tackett, Lloyd, Raines, Rushing and Sawyer2010) as well as neurodevelopmental abnormalities (Tomoda et al., Reference Tomoda, Sheu, Rabi, Suzuki, Navalta, Polcari and Teicher2011), the impact of emotional maltreatment experience on psychological outcomes is understudied compared to physical and sexual abuse. Parental support has previously been indicated as a strong predictor of psychological resilience and fewer emotional difficulties following CSA (Spaccarelli & Kim, Reference Spaccarelli and Kim1995; Yancey & Hansen, Reference Yancey and Hansen2010). However, previous research focusing on parent–child relationships among CSA survivors has focused on the impact of parental interactions and support following CSA rather than that of parental maltreatment occurring before and during these experiences. Our identification of late adolescence as a sensitivity period where parental verbal abuse is maximally associated with future depressive symptoms in women with CSA has important implications for the timing of interventions addressing parental maltreatment.

CSA and emotional maltreatment were found to substantially overlap during late adolescence. These findings highlight the importance for future research investigating how emotional maltreatment experiences from parents and peers interact and exert synergistic effects in CSA survivors, including poorer emotional regulation (Amédée, Tremblay-Perreault, Hébert, & Cyr, Reference Amédée, Tremblay-Perreault, Hébert and Cyr2019) and impaired establishment of healthy relationships (Noll, Reference Noll2021). It is additionally worth noting that, relative to rMDD/CSA women, a significantly greater number of MDD/CSA women endorsed CSA from multiple perpetrators as well as CSA perpetrated by peers. Experiencing CSA from multiple perpetrators has been previously associated with a greater number of lifetime depressive episodes (Liu, Jager-Hyman, Wagner, Alloy, & Gibb, Reference Liu, Jager-Hyman, Wagner, Alloy and Gibb2012). Recent attention has been given to sexual victimization and dating violence occurring in adolescent romantic partnerships, which has been associated with both depression (Taquette & Monteiro, Reference Taquette and Monteiro2019) and revictimization in young adulthood (Manchikanti Gómez, Reference Manchikanti Gómez2011).

The present study has several limitations. First, depressive symptoms were not assessed using a structured clinical interview; thus, information regarding MDD illness course (e.g. duration, number of previous episodes) was not collected, as well as whether the participant met diagnostic criteria for current or remitted MDD. Replicating these findings using structured clinical interviews would allow investigations of the predictive strength of emotional maltreatment characteristics on other clinical features in women with CSA. Moreover, it would allow for a more comprehensive picture of the course of depressive illness, including recurrent episodes or sustained remission. Second, this study specifically focused on the impact of CSA experienced between 11 and 18 years old; however, more than half of the women reporting CSA on the initial self-report recruitment survey reported their first CSA exposure before the age of 11. Moreover, data were not collected on sexual revictimization occurring after age 18, which is associated with more severe depression (Najdowski & Ullman, Reference Najdowski and Ullman2011). Finally, this investigation only explored the impact of emotional maltreatment and CSA in women. CSA is also associated with heightened depressive symptoms in men which can be mitigated by social support (Easton, Kong, Gregas, Shen, & Shafer, Reference Easton, Kong, Gregas, Shen and Shafer2019). Future research should investigate specific maltreatment experiences that demonstrate predictive strength for later affective psychopathology in men to inform the development of appropriate and inclusive maltreatment prevention and intervention efforts.

Conclusions

Emotional maltreatment from parents and peers is a salient component of the maltreatment histories of women who later develop depressive symptoms, and specifically those who have experienced CSA. Our results highlight vulnerability periods in late adolescence during which parental verbal abuse maximally impacts future development of depressive symptoms in CSA victims. This sensitivity period provides evidence for type- and timing-specific models of the effects of childhood maltreatment on psychopathological development. These findings necessitate future research on the mechanisms through which psychological and other adverse health consequences can be attenuated through treatments specifically targeting the potential impact of parental relationships in women with CSA.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S003329172400268X

Author contributions

L. M. H.: conceptualization, data collection, formal analysis, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing, visualization; R. D.: conceptualization, supervision, formal analysis, writing – review and editing; A. R. B.: data collection, writing – review and editing; S. M. E.: data collection, writing – review and editing; V. R.: data collection, writing – review and editing; E. J.: data collection, writing – review and editing; K. E. N.: data collection, writing – review and editing; K. O.: formal analysis, writing – review and editing; A. K.: formal analysis, writing – review and editing; F. D.: conceptualization, writing – review and editing, funding acquisition. M. H. T.: formal analysis (random forest regression), visualization, writing – review and editing; D. A. P.: conceptualization, writing – review and editing, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition.

Funding statement

This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (MH095809 awarded to D. A. P. and F. D.).

Competing interests

Over the past 3 years, Dr Pizzagalli has received consulting fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, Compass Pathways, Engrail Therapeutics, Karla Therapeutics, Neumora Therapeutics (formerly BlackThorn Therapeutics), Neurocrine Biosciences, Neuroscience Software, Sage Therapeutics, Sama Therapeutics, and Takeda; he has received honoraria from the American Psychological Association, Psychonomic Society and Springer (for editorial work), and Alkermes; he has received research funding from the Bird Foundation, Brain and Behavior Research Foundation, Dana Foundation, Millennium Pharmaceuticals, NIMH, and Wellcome Leap; he has received stock options from Compass Pathways, Engrail Therapeutics, Neumora Therapeutics, and Neuroscience Software. No funding from these entities was used to support the current work, and all views expressed are solely those of the authors. Dr Teicher created the MACE scale used to collect data on type and timing of exposure to maltreatment used in this study. However, there is no financial conflict as this scale was placed into the public domain and it is fully available and free to use. Dr Teicher has received funding from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, as well as funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, the Juvenile Bipolar Research Foundation, the ANS Foundation, and the Harvard Brain Science Initiative. Dr Teicher is a Trustee of the Dr Robert E. and Elizabeth L. Kahn Family Foundation (unpaid). He serves on the Board of Directors for the Trauma Research Foundation and on the Scientific Advisory Boards for the Penn State P50 Childhood Adversity CAPSTONE Center, the Juvenile Bipolar Research Foundation, the Words Matter Foundation, and SMARTfit™ (all unpaid). He has received honoraria, and in some cases, travel expenses for presentations from the following organizations: The Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute, University of North Carolina; Sarah Peyton Resonance Summit; Princeton Health, Penn Medicine; The Trauma Research Foundation; Applied Neuroscience Society of Australasia; McGill-Douglas Hospital; University of Turku, Finland; and the Centre for Child Mental Health, London. Dr Teicher receives royalties from Harvard Health Publishing, and he has received gifts of research equipment from SMARTfit™, All.health, and greenTEG AG. Dr Teicher has provided expert testimony for Romanucci & Blandin, LLC, The Reardon Law Firm, PC, Sgro & Roger, Marci A. Kratter, PC, Deratany & Kosner, and Douglas, Leonard & Garvey, PC. All other authors have no conflicts of interest or relevant disclosures.