Background

Depression treatment gap

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), depression affects 4.4% of the world's population (WHO, 2017), but less than half are estimated to receive treatment (Kohn et al., Reference Kohn, Saxena, Levav and Saraceno2004). In India, 1 in 20 people meets criteria for depression but fewer than 15% of these report seeking treatment (Gururaj et al., Reference Gururaj, Varghese, Benegal, Rao, Pathak, Singh and Misra2016). There are global efforts underway to reduce this ‘treatment gap’ by integrating mental health care into primary care services, as exemplified by the five-country Programme to Improve Mental Health Care (PRIME) (Lund et al., Reference Lund, Tomlinson, De Silva, Fekadu, Shidhaye, Jordans, Petersen, Bhana, Kigozi, Prince, Thornicroft, Hanlon, Kakuma, McDaid, Saxena, Chisholm, Raja, Kippen-Wood, Honikman, Fairall and Patel2012).

Access to care and geographic accessibility

The geographic accessibility of health services is implicated in most major models of access to care (Aday and Andersen, Reference Aday and Andersen1974; Penchansky and Thomas, Reference Penchansky and Thomas1981; Peters et al., Reference Peters, Garg, Bloom, Walker, Brieger and Rahman2008; De Silva et al., Reference De Silva, Lee, Fuhr, Rathod, Chisholm, Schellenberg and Patel2014). Reducing distance to the nearest mental health service through strategies such as decentralisation and integration is therefore expected to lead to increases in service uptake; a phenomenon known as ‘Jarvis’ Law’ (Hunter and Shannon, Reference Hunter and Shannon1985).

In India, greater distance to facilities has been linked to reduced treatment-seeking for general and maternal health needs, particularly affecting disadvantaged groups such as scheduled tribes and women (Sawhney, Reference Sawhney and Premi1993; Kumar et al., Reference Kumar, Singh and Kaur1997; Vissandjée et al., Reference Vissandjée, Barlow and Fraser1997; Shariff and Singh, Reference Shariff and Singh2002; Ager and Pepper, Reference Ager and Pepper2005; Kumar et al., Reference Kumar, Dansereau and Murray2014). To our knowledge, no studies have tested this association for mental disorders in an Indian context.

Mental health systems in India

India has a great variety of healing systems, including allopathic (biomedical) services, indigenous forms of health care (including Ayurveda, yoga, naturopathy, Unani, Siddha, homoeopathy and local systems of medicine), and spiritual or religious healing (Halliburton, Reference Halliburton2004). Patients' explanatory models of mental illness may align more closely with those of traditional or religious practitioners than biomedical models (Wilcox et al., Reference Wilcox, Washburn and Patel2007) but the parallel use of multiple systems is common (Albert et al., Reference Albert, Nongrum, Webb, Porter and Kharkongor2015; Shankar, Reference Shankar2015).

Private services have also become increasingly dominant in the Indian health system (De Costa and Johannson, Reference De Costa and Johannson2011), with 80% of outpatient consultations now taking place in the private sector (Selvaraj and Karan Reference Selvaraj and Karan2009; Kumar et al., Reference Kumar, Chen, Choudhury, Ganju, Mahajan, Sinha and Sen2011). Much of this sector is composed of small-scale practitioners with little or no formal training (De Costa and Diwan, Reference De Costa and Diwan2007; Ranga and Panda, Reference Ranga and Panda2016), many of whom dispense psychopharmacological treatment (Ecks and Basu, Reference Ecks and Basu2009, Reference Ecks and Basu2014).

Nonetheless, the existence of traditional and informal services is frequently ignored in discourse on mental health care in India (Quack, Reference Quack2012). Both Indian mental health policy (Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, 2014) and WHO-recommended strategies to expand access to mental health treatment (WHO, 2008) focus on public, allopathic services.

PRIME

Through PRIME, a mental health care plan (MHCP) was implemented in 2014 in Sehore district, Madhya Pradesh, in partnership with the state Ministry of Health (Shidhaye et al., Reference Shidhaye, Shrivastava, Murhar, Samudre, Ahuja, Ramaswamy and Patel2016b). The MHCP aimed to reduce the treatment gap for priority mental disorders by integrating services into public primary care facilities, thus making them more geographically accessible to the rural population. Increased accessibility of public, allopathic mental health services (the target of PRIME) was expected to reduce the treatment gap for depression (a key goal of PRIME). While this expectation arguably overlooks the great variety of care systems in the Indian context, it mirrors current accepted wisdom in global mental health that the treatment gap reflects limited access to formal mental health care. We therefore set out to test this hypothesis empirically, to inform future initiatives to reduce the depression treatment gap.

Objectives

This study aimed to:

(1) Compare travel distance by road from the households of individuals with depression to the nearest public depression treatment provider, before and after implementation of the MHCP.

(2) Measure the association between travel distance to the nearest public depression treatment provider and the probability of treatment-seeking for probable depression in rural India.

(3) Assess whether this association varies by gender, caste, symptom severity, socio-economic status (as measured by housing type, employment status, land ownership and education level) and perceived need for healthcare.

Methods

Setting

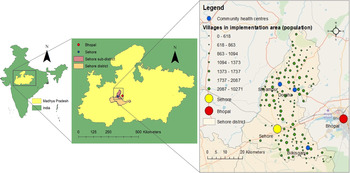

Sehore sub-district, within Sehore district, Madhya Pradesh (Fig. 1) is 74% rural, with a population of 427 432. Fewer than 4% own cars and 34% own scooters/motorcycles, with lower proportions among rural residents (Office of the Registrar General and Census Commissioner, 2011). Prior to MHCP implementation there were two public mental health specialists serving a district population of 1.3 million (Hanlon et al., Reference Hanlon, Luitel, Kathree, Murhar, Shrivasta, Medhin, Ssebunnya, Fekadu, Shidhaye and Petersen2014).

Fig. 1. Map of study area, showing location of villages within implementation area, community health centres, and towns/cities where public depression treatment services were previously available (Bhopal/Sehore).

The study area (Shidhaye et al., Reference Shidhaye, Raja, Shrivastava, Murhar, Ramaswamy and Patel2015), MHCP (Shidhaye et al., Reference Shidhaye, Shrivastava, Murhar, Samudre, Ahuja, Ramaswamy and Patel2016b) and evaluation plan (De Silva et al., Reference De Silva, Rathod, Hanlon, Breuer, Chisholm, Fekadu, Jordans, Kigozi, Petersen, Shidhaye, Medhin, Ssebunnya, Prince, Thornicroft, Tomlinson, Lund and Patel2016) have been previously described. Psychological interventions for depression were delivered by case managers and pharmacological treatments prescribed by medical officers at Community Health Centres (CHCs). Case managers conducted community case-finding and screened patients in CHCs. Some community awareness activities were conducted, such as meetings and film screenings. The term ‘implementation area’ refers to those villages where MHCP activities were fully implemented (see Fig. 1).

Data collection

As part of the PRIME evaluation, we carried out a population-based community survey with two rounds, with the primary aim of measuring a change in the proportion of people with depression and alcohol use disorders who sought treatment. The data collection methods and sampling strategy have been described elsewhere (De Silva et al., Reference De Silva, Rathod, Hanlon, Breuer, Chisholm, Fekadu, Jordans, Kigozi, Petersen, Shidhaye, Medhin, Ssebunnya, Prince, Thornicroft, Tomlinson, Lund and Patel2016; Rathod et al., Reference Rathod, De Silva, Ssebunnya, Breuer, Murhar, Luitel, Medhin, Kigozi, Shidhaye and Fekadu2016). Data collection for the first round took place prior to MHCP implementation, in two waves (May–June 2013, January–March 2014). The second round was conducted after MHCP implementation (October–December 2016). Inclusion criteria were: aged ⩾18, fluency in spoken Hindi, residency in selected households, willingness to provide informed consent and absence of cognitive impairments that would preclude informed consent or ability to participate.

This secondary analysis of the survey data considered residents of the MHCP implementation area with probable depression. Since there was no difference in the proportion of people who sought treatment for depression between rounds (Shidhaye et al., Reference Shidhaye, Baron, Murhar, Rathod, Khan, Singh, Shrivastava, Muke, Shrivastava and Lund2019), we pooled data from both rounds for analysis. Across both rounds, 6201 adults were recruited. A total of 6134 (98.9%) consented to participate. Of these, 4297 resided within the implementation area, of whom 568 had probable depression (round 1: 289, round 2: 279).

Questionnaires were administered orally, in Hindi, by trained local fieldworkers. Fieldworkers recorded participant responses using a questionnaire application programmed on Android tablet devices, which also recorded the interview location's GPS coordinates.

Measures

The screening tools and other measures are described in detail elsewhere (Rathod et al., Reference Rathod, De Silva, Ssebunnya, Breuer, Murhar, Luitel, Medhin, Kigozi, Shidhaye and Fekadu2016). Briefly, we measured current depression symptoms using the Patient Health Questionnaire, 9-item version (PHQ-9), using the standard cut-off point of ⩾10 (Manea et al., Reference Manea, Gilbody and McMillan2012). In an international meta-analysis, the PHQ-9 had a pooled sensitivity of 0.77 (95% CI 0.66–0.85) and specificity of 0.85 (95% CI 0.79–0.90) to detect major depressive disorder with this criterion (Manea et al., Reference Manea, Gilbody and McMillan2015). The main outcome of interest was treatment-seeking for depression symptoms, measured by asking: ‘Did you seek any treatment for these problems at any time in the past 12 months?’ Participants who responded affirmatively were asked to specify from whom they had sought treatment. These were divided into formal providers (generalist and specialist health workers, in the public or private sector) and complementary providers (traditional and alternative healers). Case managers, who were available in round 2 only, were categorised as formal providers. Additionally, we collected data on socio-demographic characteristics and barriers to health care use (Rathod et al., Reference Rathod, De Silva, Ssebunnya, Breuer, Murhar, Luitel, Medhin, Kigozi, Shidhaye and Fekadu2016).

Geographic measures

Household coordinates were missing for 62.8% of round 1 data and 17.6% of round 2 data. In these cases, we substituted coordinates for the village centre from India Place Finder (Mizushima Laboratory, 2013). These are based on geographic information from the 2001 Census of India, which we cross-referenced with mean GPS coordinates for households in the village. For households with GPS coordinates, the mean difference between households and their respective village centres was 935 metres (s.d. = 746 m).

The primary distance measure used was the shortest distance by road to the nearest public depression treatment provider (referred to as ‘travel distance’), calculated using network analysis in ArcGIS 10.5 (Esri, 2011). This is a recommended measure of geographic accessibility in contexts where most travel is vehicular (Delamater et al., Reference Delamater, Messina, Shortridge and Grady2012), as in 77.8% of recent health care visits reported by participants. We defined the nearest public depression treatment provider as the nearest of: Sehore city or Bhopal city only (rounds 1 and 2), plus any of the three CHCs (round 2 only). We used Open Street Maps (© OSM contributors) road network data to calculate travel distance, after cleaning these data to ensure connectivity. Since some households were located at a distance from the nearest road, we added straight line distances to the nearest road to estimate total travel distance.

Analysis strategy

We first described the socio-demographic characteristics of the sub-sample, stratified by travel distance (0 < 5 km, 5 < 10 km, 10 < 20 km, ⩾20 km).

We then compared the median travel distance from cases to a public depression treatment provider by round using the Mann–Whitney test.

Next we estimated the change in odds of treatment-seeking associated with travel distance (in kilometres) to the nearest public depression treatment provider. We considered the following covariates as potential confounders in a logistic regression model; age, education level, gender, marital status, economic status (using housing type and employment status as proxy measures), symptom severity, disability, perceived need for health care, survey round and 12-month exposure to mental health communications. We excluded covariates from the final model after checking for collinearity with variance inflation factors and a correlation matrix of all variables. Regression analyses were repeated using two alternative outcomes: (a) any depression treatment and (b) treatment from the formal health sector only.

Next we used the final regression model to test for interaction effects. We hypothesised that the effect size would be larger for women and disadvantaged castes, those with milder symptoms, individuals with lower socio-economic status and those with a perceived need for health care, based on previous Indian and international literature. Stratum-specific effects are presented when a Wald test for all interaction terms had p < 0.10.

With the exception of counts, all figures were adjusted for the multi-stage sampling design and village-level clustering. Stata 14.2 (StataCorp, 2015) was used to conduct all analyses.

Ethics

All participants were provided with an information sheet in Hindi, which was read aloud if required. After any questions were answered, they indicated informed consent with a signature or thumb print. The original survey, including the collection and analysis of GPS coordinates as part of the PRIME evaluation, was approved by the institutional review boards of Sangath, Goa, India; the Indian Council of Medical Research, New Delhi, India; WHO, Geneva, Switzerland and the University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa. The current analyses form part of the work that was approved by these committees. Ethical approval for these analyses was additionally provided by London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, London, UK (LSHTM Ethics Ref: 10439).

Results

Sample characteristics, by distance

Table 1 shows the characteristics of adults with probable depression, stratified by travel distance. A total of 69.6% of participants living <5 km from the nearest depression treatment provider were female, compared to 49.9% of those living more than 20 km away (p = 0.08). As shown in the table, the following sample characteristics varied by travel distance to the nearest facility: employment status; land ownership and religion.

Table 1. Demographic and health-related characteristics of adults with probable depression by travel distance to the nearest public health facility offering depression services, Sehore sub-district, Madhya Pradesh, India, 2013–2016

p-Values are calculated using χ2. Counts are unadjusted for sampling design; percentages are adjusted for sampling design.

The productive non-income group consisted of students and housewives.

Objective 1: travel distance by survey round

Implementation of the MHCP reduced the median travel distance to a public depression treatment provider from 26.9 km in round 1 (25th and 75th percentiles: 16.0 km, 36.2 km; skewness 2.40) to 9.7 km in the second round (25th and 75th percentiles: 6.5 km, 16.8 km; skewness 4.29), (p < 0.0001).

Objective 2: travel distance and treatment-seeking for depressive symptoms

As previously reported (Shidhaye et al., Reference Shidhaye, Baron, Murhar, Rathod, Khan, Singh, Shrivastava, Muke, Shrivastava and Lund2019), of the 568 people with probable depression in both rounds, 75 (13.9%) sought treatment for these symptoms.

There was no evidence of an association between treatment-seeking and distance to a public depression treatment provider, either in unadjusted or adjusted models, with any provider or only formal providers (see Table 2). We checked for differences between rounds and found no evidence of an association at either time point (round 1: OR 1.00, 95% CI 0.99–1.01; round 2: OR 0.97, 95% CI 0.93–1.02).

Table 2. Travel distance to nearest public depression treatment provider and odds of seeking treatment for adults with probable depression (n = 568) in Sehore sub-district, Madhya Pradesh, India, 2013–2017

Odds ratios, 95% CIs and p-values calculated using logistic regression.

Formal services include specialist doctors, generalist doctors, other mental health professionals (psychologists, counsellors and mental health nurses), other generalist health workers (social workers, community health workers, nurses, ANMs, ASHAs and AWWs) and case managers. Excludes ojha/guni/dev maharaj, traditional healers, herbalists, spiritualists or other providers.

Adjusted models include the following covariates: education level, marital status, symptom severity, gender, land ownership, employment, round, exposure to mental health communications, age group.

Objective 3: treatment-seeking and travel distance among sub-groups

Table 3 shows the association between travel distance and treatment-seeking by the sub-group (where Wald p-values for interaction terms <0.10; full table in online Supplementary material). There was evidence of interaction with caste, employment status and perceived need for health care, weak evidence of interaction with age, but no evidence of any interaction effects by gender, education level, religion, marital status, housing type, land ownership, symptom severity or exposure to mental health communications.

Table 3. Sub-group analysis for distance to depression treatment provider and odds of treatment-seeking for adults with probable depression (n = 568) in Sehore sub-district, Madhya Pradesh, India, 2013–2017

Odds ratios, p-values and confidence intervals were calculated with logistic regression.

Besides the interaction term, each model was adjusted for education level, marital status, symptom severity, gender, land ownership, employment, round, exposure to mental health communications and age group.

The effect sizes by caste and perceived need for health care were small and in the opposite direction from expected; e.g. for every 1 km increase in travel distance to the nearest treatment provider, individuals from scheduled castes had 4% higher odds of seeking treatment. There was a larger effect for the unemployed sub-group, with a 27% reduction in the odds of seeking treatment for every 1 km increase in travel distance.

Discussion

Principal findings

Travel distance to the nearest public depression treatment provider was significantly reduced after the implementation of the MHCP, but the proportion of people with probable depression who sought treatment remained low regardless of distance to services. To our knowledge, this is the first study from India to examine associations between travel distance and treatment-seeking for mental disorders.

The lack of evidence of an association between travel distance and treatment-seeking contrasts with literature from high-income countries (HIC) on ‘Jarvis’ law’ in mental health care (Bille, Reference Bille1963; Davey and Giles, Reference Davey and Giles1979; Stampfer et al., Reference Stampfer, Reymond, Burvill and Carlson1984; Shannon et al., Reference Shannon, Bashshur and Lovett1986; Almog et al., Reference Almog, Curtis, Copeland and Congdon2004; Zulian et al., Reference Zulian, Donisi, Secco, Pertile, Tansella and Amaddeo2011; Packness et al., Reference Packness, Waldorff, dePont Christensen, Hastrup, Simonsen, Vestergaard and Halling2017). The narrow range of the confidence intervals indicates that this finding is unlikely to be due to low statistical power.

Mechanisms and methodological differences

There are several potential explanations for the difference in findings compared to studies from HIC.

Threshold effects

Research from HIC has pointed to a ‘zone of indifference’, beyond which distance ceases to affect rates of mental health service use (Shannon et al., Reference Shannon, Bashshur and Lovett1986; Stampfer et al., Reference Stampfer, Reymond, Burvill and Carlson1984). However, we found no evidence of such threshold effects in our data.

Over-utilisation

Distance decay effects in HIC primarily affect those with milder symptoms (Joseph and Boeckh, Reference Joseph and Boeckh1981) and may reflect over-utilisation of services by those in the vicinity of health services (Davey and Giles, Reference Davey and Giles1979). Since the current analysis was restricted to people with probable depression, treatment-seeking by those without clinical need was largely excluded.

Population-based v. facility-based samples

Unlike most previous research on this topic, this study used a population-based sample. In facility-based studies, geographic differences in prevalence complicate the interpretation of utilisation data. Furthermore, it appears that the decision to seek any care may be influenced by different factors than the choice of provider among those who seek help (Fortney et al., Reference Fortney, Rost and Zhang1998). In the Indian setting, where public services are not the only option, the location of public services may therefore influence the choice of provider but not the overall likelihood of treatment-seeking.

Differences in health systems

Perhaps most importantly, the context of medical pluralism in India means that, unlike countries with more homogeneous health systems, access to services is far more complex than the availability or accessibility of public, allopathic health services (Halliburton, Reference Halliburton2004). The current findings clearly undermine the assumption that reducing travel distance to public mental health services will reduce the overall treatment gap for depression in India and comparable settings, and suggest that future research should focus on the role of the wider health sector in influencing treatment-seeking for depression, including private and complementary providers (Quack, Reference Quack2012).

Implications

Both international and Indian mental health policies advocate the integration of mental health services into primary care (WHO, 2008; WHO & WONCA, 2008; Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, 2014), partly on the basis that this improves the geographic accessibility of services. However, this study found that those living in the immediate vicinity of public mental health services are no more likely to seek care than those facing longer journeys, demonstrating that distance to the nearest public depression service is not a primary factor in explaining low treatment-seeking rates.

One interpretation of this finding is that increased accessibility of services is insufficient to reduce the treatment gap in areas where demand for these services is very low. The Vidarbha Stress and Health Program, another depression programme in central India, included village-level demand generation activities and reported a six-fold increase in treatment-seeking in the implementation area (Shidhaye et al., Reference Shidhaye, Murhar, Gangale, Aldridge, Shastri, Parikh, Shrivastava, Damle, Raja, Nadkarni and Patel2017), in contrast to PRIME.

An alternative interpretation is that the accessibility of public, allopathic mental health services is of little relevance to treatment-seeking behaviour, since these represent a minority of services and are not the preferred choice of healthcare for many (De Costa and Diwan, Reference De Costa and Diwan2007; De Costa and Johannson, Reference De Costa and Johannson2011). The finding that the location of public, allopathic mental health services has negligible effects on the treatment gap in this context should prompt us to re-examine the sole focus on these in current mental health policy, and to take into account the complexity of the health system in future initiatives to improve access to care (Dalal, Reference Dalal2005).

Caution is needed in interpreting the results of the sub-group analyses, since multiple tests were performed, increasing the likelihood of chance findings, and the effect sizes were small. The preliminary finding that for some groups, those living further from public health services were slightly more likely to seek treatment, could indicate that other mechanisms, such as stigmatisation, might be involved. Further investigation and replication of these results are necessary to understand the processes involved in decisions around treatment-seeking for depression. Unemployed adults may be more sensitive to travel distance to public services as an obstacle to treatment-seeking than the rest of the population, although this group represents only 4.2% of individuals with probable depression.

Strengths

This study used a community-based sample, and therefore reflects the general population better than facility-based studies. The sample size compares favourably with previous international (Roberts et al., Reference Roberts, Miguel Esponda, Krupchanka, Shidhaye, Patel and Rathod2018) and India-based studies of treatment-seeking for mental disorders (Lahariya et al., Reference Lahariya, Singhal, Gupta and Mishra2010; Mishra et al., Reference Mishra, Nagpal, Chadda and Sood2011; Jain et al., Reference Jain, Gautam, Jain, Gupta, Batra, Sharma and Singh2012; Andrade et al., Reference Andrade, Alonso, Mneimneh, Wells, Al-Hamzawi, Borges, Bromet, Bruffaerts, De Girolamo and De Graaf2014; Mathias et al., Reference Mathias, Goicolea, Kermode, Singh, Shidhaye and San Sebastian2015; Shidhaye et al., Reference Shidhaye, Gangale and Patel2016a). We chose network analysis measures as a rigorous method of calculating travel distance (Fortney et al., Reference Fortney, Rost and Warren2000; Apparicio et al., Reference Apparicio, Abdelmajid, Riva and Shearmur2008; Nesbitt et al., Reference Nesbitt, Gabrysch, Laub, Soremekun, Manu, Kirkwood, Amenga-Etego, Wiru, Höfle and Grundy2014).

Limitations

GPS coordinates were missing for some households, including a large proportion in round 1. However, we believe that the error introduced by substituting village centroid coordinates in these cases is relatively small, given the size of villages in the implementation area. When we excluded those with missing coordinates, we found no difference in our results for either round.

Our exposure of interest was an estimate of travel distance, but we lacked data on access to transportation to convert these to travel time estimates, which may be of greater relevance to treatment-seeking decisions. Future research should generate more nuanced estimates of travel time and cost for this setting.

The data were cross-sectional, meaning that some factors (e.g. symptom severity, perceived needs) may have changed over the period asked about. Recall bias is possible since we used self-reported outcome data (Bhandari and Wagner, Reference Bhandari and Wagner2006), although this affects binary measures of treatment-seeking less than measures of volume or frequency (Raina et al., Reference Raina, Torrance-Rynard, Wong and Woodward2002; Carroll et al., Reference Carroll, Sutherland, Kemp-Casey and Kinner2016). Differential misclassification is possible if longer journeys lead to greater recollection of treatment-seeking, which could explain the apparent positive association between distance and treatment-seeking among some groups.

We did not have data on the location of private or complementary providers in order to calculate travel distance to these, since these are highly numerous and no official register of these services exists. Future studies might usefully attempt to map these to generate more context-specific measures of geographic accessibility.

It would also have been useful to investigate whether distance to the nearest public provider affected the likelihood of consulting a public rather than private or complementary provider, among those who sought depression treatment. However, the number who sought treatment was too small to enable this. Finally, the low rate of treatment-seeking overall limits the chances of finding an association between distance and treatment-seeking, although the narrow confidence intervals suggest a relatively high degree of precision in our estimates.

Conclusion

The current study identified no association between travel distance to the nearest public depression treatment provider and treatment-seeking for probable depression, except for the small sub-group of unemployed adults. Low geographic accessibility of public, allopathic services does not explain the treatment gap for depression in this context, and decentralising public mental services to reduce travel distance will not of itself reduce the treatment gap for depression in rural India. Future research should examine alternative measures of geographic accessibility of mental health services, taking into account the health systems context of India which includes many private and complementary service providers.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S204579601900088X.

Data

Interested parties may notify the PRIME investigators of their interest in collaboration, including access to the data set analysed here, through the following website: http://www.prime.uct.ac.za/contact-prime.

Acknowledgements

This study used data from the Programme for Improving Mental health care (PRIME), which is a Research Programme Consortium led by the Centre for Public Mental Health at the University of Cape Town (South Africa) and funded by the UK government's Department for International Development (DFID). Partners and collaborators in the consortium include Sangath, the Public Health Foundation of India and Madhya Pradesh State Ministry of Health (India), Addis Ababa University and Ministry of Health (Ethiopia), Health Net TPO and Ministry of Health (Nepal), University of Kwazulu-Natal, Human Sciences Research Council, Perinatal Mental Health Project and Department of Health (South Africa), Makerere University and Ministry of Health (Uganda), BasicNeeds, Centre for Global Mental Health (London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine and Kings Health Partners, UK) and the World Health Organisation (WHO).

Financial support

This study used data from the Programme for Improving Mental health care (PRIME) (http://www.prime.uct.ac.za). This work was supported by the United Kingdom Department for International Development (Grant number 201446). The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the UK Government's official policies. The first author was funded by a PhD studentship from the Bloomsbury Colleges (University of London) and subsequently by an ESRC post-doctoral fellowship (ES/T007125/1). The funders had no role in the design or execution of this study, nor in the decision to submit the results for publication.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.