1. Introduction

While existing empirical research on the relationship between Belgian Dutch (henceforward abbreviated as BD) and Netherlandic Dutch (henceforward ND) has primarily targeted variation in pronunciation (for example, H. Van de Velde Reference Van de Velde1996, H. Van de Velde et al. Reference Van de Velde, van Hout and Gerritsen1997, Reference Van de Velde, Mikhail Kissine, van der Harst and van Hout2010, Adank et al. Reference Adank, van Hout and Van de Velde2007) and the lexicon (see, among others, Geeraerts et al. Reference Geeraerts, Grondelaers and Speelman1999, Grondelaers et al. Reference Grondelaers, Hilde Van Aken and Geeraerts2001, Daems et al. Reference Daems, Heylen and Geeraerts2015), relatively little is known about how the national varieties compare at the level of grammar or morphosyntax. Footnote 1 There are three reasons for that. The first reason is that laymen and analysts alike are for the most part oblivious to natiolectal variation in the grammar of Dutch, unless categorical diver-gences are involved that have been heavily mediatized (a case in point is the rapidly diffusing but stigmatized subject use of the object pronoun hun ‘them’; see Grondelaers et al. Reference Grondelaers, van Gent, van Hout, Christensen and Jensen2022).Footnote 2 For instance, few Lowlanders will realize that the alternation in 1 below is more productive in BD than in ND, where the option in 1a is limited to a small number of verbs of food provision or preparation such as inschenken ‘pour’ or opscheppen ‘dish up’, and on the lectal dimension restricted to speakers from the (south)eastern parts of the language area (Cornips Reference Cornips1998, Colleman & De Vogelaer Reference Colleman and De Vogelaer2002–2003, Colleman Reference Colleman, Geeraerts, Kristiansen and Peirsman2010).Footnote 3

(1)

The low number of categorical differences has led to the belief that BD and ND share the same underlying grammar, with only a handful of minor, that is, “superficial” differences. Typical minor differences cited in the literature (see de Louw Reference Louw2016:119–122 for a recent example) include a BD propensity to insert nonverbal material in the clause-final verb cluster, and the better preserved three-gender system in BD, surfacing mainly in pronominal reference. Regarding this latter aspect, De Vos et al. (Reference De Vos, De Sutter and De Vogelaer2021:56) observe the following:

[W]hereas the North shows generalized use of masculine or common pronouns for simple entities [that is, concrete count nouns; RDT, SG, & DS] irrespective of their gender, neuter nouns referring to inanimates in the South always trigger neuter pronouns. In this respect, southern Dutch agreement more strongly resembles the historical system.

Examples of the two phenomena are given in 2 and 3, with the a-examples being the more frequent option in ND, and the b-examples in BD. (For corpus counts, see Augustinus & Van Eynde Reference Augustinus and Van Eynde2014:166 on the alternation illustrated in 2, and Audring Reference Audring2006 and De Vos et al. Reference De Vos, De Sutter and De Vogelaer2021 on that in 3). The examples in 3 are from the Corpus Gesproken Nederlands (CGN; Corpus of Spoken Dutch).

(2)

(3)

The second reason is ideological in nature. Apart from the involun-tary ignorance of grammatical North–South divergences on the part of lay and expert observers, there is some reluctance on the part of both Dutch and Flemish linguists to recognize natiolectal variation in the grammar. There is a deep-seated but rarely articulated notion among Dutch linguists that BD is nonstandard. For example, van Bergen (Reference Bergen2011:53) uses national provenance as a predictor in her analysis of specific genitive choices: “The z’n-genitive is considered a non-standard variant of the s-genitive: therefore, z’n-genitives are expected to occur more frequently in [BD] than in the Netherlands.” The underlying implication appears to be that BD is not standard, and that nonstandard grammar is not part of ND.

For Flemish observers, the reluctance to accept (a lot of) natiolectal variation in morphosyntax stems from similar doubts, or rather unease, about the standard status of BD. There is wide consensus that the standardization of BD was historically delayed, and that its 20th-century history has been codetermined by an integrationist endeavor to model BD on the (allegedly) more standardized ND variety (see Willemyns Reference Willemyns and Daniëls2003, Reference Willemyns2013 and van der Sijs 2021, among many others, for book-length historical accounts of the standardization of Dutch). While there is empirical evidence that efforts to adapt the BD lexicon to ND usage were partly successful between the 1950s and 1990s (Geeraerts et al. Reference Geeraerts, Grondelaers and Speelman1999, but see Daems et al. Reference Daems, Heylen and Geeraerts2015), BD and ND pronunciation diverged after the 1930s (H. Van de Velde Reference Van de Velde1996, H. Van de Velde et al. Reference Van de Velde, van Hout and Gerritsen1997, Reference Van de Velde, Mikhail Kissine, van der Harst and van Hout2010), and it is unclear to what extent the BD adoption of the ND standard extends to less superficial components, such as morphology and syntax. Natiolectal differences in morphosyntax, arguably the deepest motor of Dutch, are not conducive to the idea that the Flemish have fully acquired ND, and for many professional linguists of the previous generations, who at least implicitly support the integrationist program, such North–South variation is particularly undesirable. This unease is rarely made explicit in the literature—if anything, there seems to be a “let sleeping dogs lie” attitude—and the handful of overt claims by Belgian linguists that there is only one grammar in Dutch offhandedly downplay the differences, but at the same time contain phrasing and hedging that cast some doubt. The following quote by Van Haver (Reference Van Haver1989:41)—who nevertheless advocated tolerance toward certain (lexical) “belgicisms” in the standard language (Janssens Reference Janssens1995:58)—is an interesting case in point:

Een taalsysteem wordt het scherpst gekarakteriseerd door zijn structuren voor verbuiging en vervoeging, voor woord- en zinsvorming. Die structuren zijn voor Vlamingen en Nederlanders zo goed als identiek. Het komt me voor dat hierin een eerste argument kan worden gevonden om (beperkte) verschillen tussen Noord en Zuid als niet fundamenteel te beschouwen.

A language system is most sharply characterized by its declension and conjugation paradigms as well as by its morphological and syntactic structures. These are almost identical for the Flemish and the Dutch. It seems to me that this presents the first argument in favor of considering (limited) differences between North and South as not fundamental.Footnote 4

In this quote, the audacious claims about the alleged equivalence (“almost identical”, “(limited) differences”, and “not fundamental”) are seemingly at odds with the somewhat hesitant hedging: “It seems to me that this presents the first argument…” The impression we get is that the author is convincing himself, rather than concluding that there is little North–South variation in the morphosyntax of Dutch. In the following passage from Haeseryn Reference Haeseryn, van Hout and Kruijsen1996, arguably the most extensive overview of grammatical North–South differences to date (a slightly trimmed-down version in English can be found in Haeseryn Reference Haeseryn2013), similar conclusions about the identical grammar of BD and ND are drawn in spite of the discovery of “aanzienlijk meer gevallen […] dan menigeen geneigd is te denken” [considerably more cases […] than many are inclined to believe] (Haeseryn Reference Haeseryn, van Hout and Kruijsen1996:123):

Ten eerste gaat het hoogst zelden om een absolute tegenstelling tussen noord en zuid, meer bepaald tussen het Nederlands in België en het Nederlands in Nederland. Er is vrijwel niets wat uitsluitend in het ene deel van het taalgebied voorkomt en in het ander deel onmogelijk is. […] In de regel gaat het dus om graduele verschillen tussen de twee grote delen van het taalgebied: iets komt (afgezien van eventuele stijlgebonden verschillen) meer in het ene dan in het andere deel voor. […] Alleen al vanwege het feit dat het in de meeste gevallen een kwestie van meer of minder is, zie ik dus bepaald geen reden om de verschillen, ook al zijn ze reëel, te overdrijven, laat staan om te spreken van een fundamenteel verschil in grammatica. Het overgrote deel van de grammaticaregels hebben noord en zuid gemeenschappelijk.

In the first place, there is hardly ever an absolute opposition between North and South, and, in particular, the opposition between Dutch in Belgium and Dutch in the Netherlands. There is virtually nothing that occurs exclusively in one part of the language area, while being impossible in the other. As a rule, there are gradual differences between the two major parts of the language area: Something occurs (regardless of potential stylistic differences) more in one part than the other. If only because of the fact that it is mostly a question of more or less, I definitely see no reason to exaggerate the differences, even if they are real, let alone to speak of a fundamental difference in grammar. The bulk of grammar rules are shared by North and South. [emphasis added]

As in the previous quote, the conclusions are prudently hedged to convey some modality; at the same time, the author’s attitude again bespeaks a whiff of self-persuasion (in the face of evidence to the contrary—“considerably more cases”) as well as relief that the evidence for grammatical divergence is not stronger. In the quote from Taeldeman (Reference Taeldeman1992:47) below, the assertion that there are not many (conspicuous) North–South differences is posited with more confidence, and comple-mented with an exhortation to the Flemish to align their structures with the ND grammar:

M.b.t. deze gestructureerde component van de taal zijn de Noord/Zuid-verschillen minder talrijk en minder opvallend. Aangezien bovendien uit sociolinguistisch [sic] onderzoek […] blijkt dat Vlamingen op dit vlak best bereid zijn om nog een en ander van de Noordnederlanders [sic] te leren, lijkt stimulering van die principiële wil tot verdere aansluiting bij de Noordnederlandse grammatica voor de hand te liggen.

With regard to this structured component of the language, North–South differences are less numerous and less noticeable. Moreover, since sociolinguistic research […] shows that the Flemish are quite willing to learn a few things from the Northern Dutch in this area, it seems obvious to encourage that principled will to further align with Northern Dutch grammar.

Related to the foregoing ideologically motivated inclination to downplay natiolectal variation is the fact that such variation was generally defined from an “essentialist” point of view (see Geeraerts Reference Geeraerts1999:30). That is, early studies were primarily geared toward discovering (near-)categorical differences in the grammatical inventory of BD vis-à-vis ND, without looking at differences in usage in both varieties. As a consequence, probabilistic differences—proportional asymmetries on some variable instead of categorical presence/absence—were often either overlooked or relegated to a marginal position in the discussion. The just-cited passage from Haeseryn Reference Haeseryn, van Hout and Kruijsen1996 also conveys this essentialist conception of natiolectal variation in considering only (near-)categorical oppositions as theoretically valid or descriptively interesting, while giving gradual differences little, if any weight (see also de Rooij Reference Rooij, de Rooij and Jan1972:6 for a similar stance).

A third important reason for our limited understanding of natiolectal variation in Dutch morphosyntax is the absence of sufficiently large and lectally stratified Dutch corpora before the 2000s. It is only with the advent of corpora such as CONDIV (Grondelaers et al. Reference Grondelaers, Katrien Deygers, Van Den Heede and Speelman2000), CGN (Oostdijk Reference Oostdijk, Peters, Collins and Adam2002), and, more recently, the SoNaR corpus (Oostdijk et al. Reference Oostdijk, Reynaert, Hoste, Schuurman, Spyns and Odijk2013) that the relationship between the national varieties of Dutch could be studied “in any responsible data-based fashion” (Grondelaers & van Hout Reference Grondelaers and van Hout2011:200). Previously, primary data were often culled from monumental dialect atlases such as Blancquaert and Pée’s Reeks Nederlandse Dialectatlassen (RND).Footnote 5

Since the 2000s, an ever growing body of (predominantly Flemish) studies has been going beyond impressionistic assessments of (mostly) absolute differences (in particular, Grondelaers, Speelman, & Carbonez Reference Grondelaers, Speelman and Carbonez2001, Grondelaers et al. Reference Grondelaers, Speelman, Geeraerts, Morin and Sébillot2002, Reference Grondelaers, Speelman, Geeraerts, Kristiansen and Dirven2008, De Sutter Reference De Sutter2005, Tummers Reference Tummers2005, Vandekerckhove Reference Vandekerckhove2005, Diepeveen et al. Reference Diepeveen, Ronny Boogaart, Byloo, Janssen and Nuyts2006, Speelman & Geeraerts Reference Speelman, Geeraerts, Sanders and Sweetser2009, Colleman Reference Colleman, Geeraerts, Kristiansen and Peirsman2010, Levshina et al. Reference Levshina, Geeraerts and Speelman2013, Gyselinck & Colleman Reference Gyselinck and Colleman2016, Fehringer Reference Fehringer2017, Pijpops & F. Van de Velde 2018, Pijpops Reference Pijpops2019, Reference Pijpops2020).Footnote 6 Building on careful statistical analysis of corpus data, many of these studies were able to gauge not only the distribution of competing grammatical constructions in BD and ND, but, crucially, also the nature and the significance of the language-internal and language-external factors that determine choices in both varieties and the extent to which they do so.

Yet, in spite of all the work cited in the previous paragraph, our knowledge of natiolectal differences in the grammar of Dutch remains tentative. To begin with, the above-cited studies discuss no more than a handful of patterns (pace Diepeveen et al. Reference Diepeveen, Ronny Boogaart, Byloo, Janssen and Nuyts2006), whose sensitivity to (natiolectal) variation is typically well-known beforehand. The distri-bution of existential er ‘there’ (in the studies by Grondelaers and colleagues cited in the previous paragraph), and the well-known “red–green” word-order alternation, namely, the relative order of the temporal auxiliary and the past participle in the verbal end group (in De Sutter Reference De Sutter2005), are notorious cases in point.

In addition, the cited studies address grammatical variation from different perspectives, using different corpora (for example, spoken versus written) and analytical tools (for example, bivariate versus multi-variate statistics). Neither is there any consistency in the way natiolectal variation is modeled: Some add nationality of the language user as a fixed covariate to their models, others build separate models for each variety, and in many cases it remains unclear to what extent lectal factors interact with internal constraints.Footnote 7 More importantly, however, there is a noticeable lack of interest in natiolectal morphosyntactic variation in studies by—mainly, but not exclusively—Dutch linguists (which is probably related to the aforementioned bias). Many studies that claim to make predictions about “Dutch” are restricted to ND, even when containing preferences that are only marginally acceptable to Belgian users (as in Bouma & de Hoop Reference Bouma and de Hoop2008:670); and while van Bergen & de Swart (2010) and Vogels & van Bergen (Reference Vogels and van Bergen2017) build on a stratified corpus of BD and ND, the national factor is strangely ignored in their statistical modeling.

Most of the aforementioned Flemish studies, by contrast, demon-strate that proportional differences between BD and ND are not just variable externalizations of the same grammatical knowledge; instead, they seem to point to more “structural” divergences, in terms of the nature and prominence of the constraints that fuel variation. To make the latter more concrete, consider the following example from Pijpops Reference Pijpops2019. In both BD and ND, a number of verbs can take either a nominal or a prepositional complement, such as zoeken (naar) ‘search (for)’ or knuffelen (met) ‘cuddle (with).’ Both syntactic choices are thus available to most, if not all, speakers of BD and ND. However, as Pijpops (Reference Pijpops2019) shows, the variation appears to be driven by more clear-cut semantic and lexical distinctions in ND than in BD. Similar observations have been made for presentative er ‘there’ in adjunct-initial sentences (Grondelaers et al. Reference Grondelaers, Speelman, Geeraerts, Morin and Sébillot2002, Reference Grondelaers, Speelman, Geeraerts, Kristiansen and Dirven2008; De Troij et al. Reference De Troij, Grondelaers, Speelman and van den Bosch2021), the causative auxiliaries doen ‘do’ and laten ‘let’ (Speelman & Geeraerts Reference Speelman, Geeraerts, Sanders and Sweetser2009, Levshina et al. Reference Levshina, Geeraerts and Speelman2013), and the alternation between a nominal and a prepositional beneficiary in example 1 above (Colleman Reference Colleman, Geeraerts, Kristiansen and Peirsman2010). Grondelaers et al. (Reference Grondelaers, Speelman, Geeraerts, Kristiansen and Dirven2008:186ff.) have tentatively accounted for this difference by proposing that the advanced standard status of ND vis-à-vis BD transpires not only from planned adaptations (see above), but also from spontaneous optimizations in the grammar, pertaining to what they refer to as functional specialization and lexical conventionalization/fossilization.

All of the above makes it a challenging enterprise to draw general conclusions about the grammatical relationship between BD and ND. We propose that a better understanding of natiolectal variation in the grammar of Dutch requires a two-step programme. We first need an aggregate perspective that would extend beyond the study of single variables in order to pinpoint the number and the nature of the morpho-syntactic alternations that truly reflect north-south variation. As a second step, we need a methodology to investigate the role that lexical conventionalization plays in ND grammar; in this light, we system-atically juxtapose multifactorial methodologies (notably, regression analysis) with learning algorithms that can handle lexical effects (such as memory-based learning algorithms; see Daelemans & Van den Bosch 2005 and De Troij et al. Reference De Troij, Grondelaers, Speelman and van den Bosch2021), in order to investigate whether lexical conventionalization does indeed play a larger role in ND.

In this article, we take the first of these steps and introduce a corpus-based methodology to obtain the desired aggregate view of natiolectal variation in the grammar of Dutch. By combining approaches from earlier studies with more recent corpus-based analyses we are able to scan the grammar of Dutch for alternations that reflect North–South variation and thus gain a bird’s-eye perspective on natiolectal variation. In order to avoid selection bias, that is, an overrepresentation of variables that are known beforehand to exhibit natiolectal sensitivity, with unknown patterns passing unnoticed, we use a fully data-driven compu-tational bottom-up procedure to extract patterns of grammatical variation in Dutch from bilingual parallel corpora. For a representative selection of these patterns (N=20), corpus counts are collected and statistically analyzed in order to lay bare natiolectal differences in the grammar of Dutch.

The remainder of this article is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces two (conceptual) methodological issues that have to be tackled before we proceed to the computational procedure (in section 3) we used to sample patterns of grammatical variation in Dutch. Section 4 forms the backbone of the article, in which we present corpus analyses of 20 variables from various areas of the grammar ranging from inflectional variation to lexically conditioned syntactic variation to pure word order variation. An overview of our most important findings is given in section 5, while section 6 presents a general discussion. Section 7, finally, wraps up with a conclusion and some avenues for further research.

2. Natiolectal Variation and Bona Fide Grammatical Variation

As our aim in this article is to detect natiolectal differences in the grammar of Dutch, we need to make two methodological decisions that are discussed and justified below. More specifically, from a metho-dological perspective, we need to answer two questions: What is natiolectal variation and what counts as bona fide grammatical variation?

With respect to the first question, it is our methodological decision to define natiolectal variation in terms of the Belgian–Dutch state border, which cuts through the easternmost Limburg and the central Brabant dialect areas. Its linguistic relevance may be questionable as it is not a natural border (Bennis & Hermans Reference Bennis and Hermans2013:603). Still, in spite of its relatively late establishment—that is, in 1839—it appears to affect the standard language, according to Bennis & Hermans (Reference Bennis and Hermans2013:605):

This border is starting to exert a clear influence on the standard language as it is spoken on both sides of the border. Very likely, this will have important consequences for the dialects on both sides of the border, even if they belong to the same historical dialect group.

Bennis & Hermans (Reference Bennis and Hermans2013:605) go on to name a number of morpho-logical and syntactic phenomena that are omnipresent in one country, while being (almost) completely absent in the other. In the same vein, van Bree (Reference Bree2013:116) mentions a number of syntactic southern innovations that “no longer reached the north or did not get a foot-hold there” after present-day Flanders became separated from the present-day Netherlands during the Eighty Years’ War (1568–1648; see Willemyns Reference Willemyns2013:78–79). Thus, while the state border can be claimed to be also an emerging linguistic border that separates Belgian from Netherlandic standard Dutch, our reliance on this political demarcation inevitably blurs some intra-Belgian and intra-Netherlandic variation. A case in point is the southernmost Dutch province of Limburg, which was part of Belgium up to 1839, and which sometimes manifests grammatical preferences that converge more with typical BD than with typical ND choices (see, for example, Koemans & Grondelaers Reference Koemans and Grondelaers2018, who found that Netherlandic-Limburgian preferences in the domain of existential constructions align more with BD than with central ND preferences).

The second question that needs to be addressed is what counts as bona fide grammatical variation. In particular, what kind of grammatical asymmetries count as valid natiolectal differences within the grammar of Dutch, and what is the value of noncategorical gradience for determining the morphosyntactic relationship between BD and ND? The answers to these questions strongly correlate with the scholarly paradigm in which a researcher operates, and there is a noticeable difference on this point between structuralist–generativist conceptions of grammar on the one hand and usage-based conceptions on the other. Scholars like ourselves, who take their inspiration from usage-based approaches, follow the principle articulated by Bybee (Reference Bybee2010:6):Footnote 8

[I]t is important not to view the regularities as primary and the gradience and variation as secondary; rather the same factors operate to produce both regular patterns and the deviations. If language were a fixed mental structure, it would perhaps have discrete categories; but since it is a mental structure that is in constant use and filtered through processing activities that change it, there is variation and gradation.

The importance of noncategorical gradience central to the usage-based enterprise is all the more crucial when one deals with national varieties of a single language involved in an arguably incomplete divergence process. In such ongoing processes, variation and gradience—or nondiscreteness—can be an indication of transience; by ignoring or downplaying such nondiscreteness one would disregard the synchronic evidence of a system in motion:

Grammar is shaped by the language’s history, and as living languages never seem to be in a steady state, but are constantly undergoing change, a synchronic description of the grammar runs the risk of taking a blurry snapshot of a “moving” i.e. transient structure. Especially in cases where there is variation, synchronists may face difficulties coming up with comprehensive descriptions. This often leads to synchronists dismissing variation as “performance noise”, or maybe as “social markers of identity”, and claiming they restrict themselves to core grammar, taking the snapshot with a short shutter time, to stay in the camera metaphor. This is a crucial divide between structuralist–generativist accounts and usage-based accounts.

(F. Van de Velde Reference Van de Velde2017:73)

In view of the latter, we expect to find proportional rather than categorial differences, but we also expect these proportional differences to be meaningful in the context of a diachronic-divergence hypothesis. Considering the arguably obstructed development of BD, for instance, we can expect older constructional variants to be more frequent in BD, whereas newer ones will be more prevalent in ND. In addition, and following up on similar evidence in Grondelaers et al. Reference Grondelaers, Robbert De Troij and van den Bosch2020, we may expect to find a BD tendency to over-code, namely, to prefer prepo-sitional over bare complements, and to prefer stronger deictics (such as proximal demonstratives) over weaker deictics (such as distal demon-stratives; see section 3.2).Footnote 9 Crucially, if we can detect such patterns across individual variables, it is unimportant how large the natiolectal differences on the individual variables are (as long as they are statistically significant). What we anticipate in any case, in view of the clear stylistic-stratification effects reported in previous studies on individual constructional alternations in BD and ND (notably Grondelaers et al. Reference Grondelaers, Speelman, Geeraerts, Morin and Sébillot2002, Reference Grondelaers, Speelman, Geeraerts, Kristiansen and Dirven2008, De Sutter Reference De Sutter2005, Tummers Reference Tummers2005, Speelman & Geeraerts Reference Speelman, Geeraerts, Sanders and Sweetser2009), is that natiolectal skewing in newly found alter-nations will be (much) more noticeable in colloquial, informal sources (such as online materials) than in more formal ones (such as conservative newspapers, where journalists and editors have the time to adapt their grammatical choices to prescriptive exigencies).

3. Identification of Morphosyntactic Alternation Patterns

In this section, we briefly describe the stepwise data-driven procedure we used to detect patterns of variation in Dutch morphosyntax. At this point, we do not yet introduce a distinction between BD and ND, as our procedure builds on parallel corpora that are not labeled for national provenance. Limitations of space preclude us from detailing the entire procedure, so we necessarily gloss over many of the technicalities involved; the interested reader is referred to De Troij (to appear) for more details.

Our approach proceeded in two major steps. The first one was to extract from sizable bilingual parallel corpora a large dataset of Dutch paraphrases, that is, formally different sequences of n word tokens, or (word) n-grams, which coalign with an identical n-gram in some foreign language (Bannard & Callison-Burch Reference Bannard, Callison-Burch, Knight, Ng and Oflazer2005; see Grondelaers et al. Reference Grondelaers, Robbert De Troij and van den Bosch2020 for a first exploration of this technique in a quest for syntactic variation in Dutch). An example may elucidate this. Imagine one has a Dutch–English parallel corpus, and one discovers that two Dutch n-grams, for example, gezien heeft and heeft gezien, translate as the same English n-gram, for example, has seen. One assumes then that these Dutch n-grams convey approximately the same meaning and considers them as paraphrases.

We used three large sentence-aligned parallel corpora from the OpenSubtitles2018 collection (Lison et al. Reference Lison, Tiedemann, Kouylekov, Calzolari, Choukri, Cieri, Declerck, Goggi, Hasida, Isahara, Maegaard, Mariani, Mazo, Moreno, Odijk, Piperidis and Tokunaga2018), namely, Dutch–English, Dutch–French, and Dutch–German, which together total 603.7 million Dutch word tokens.Footnote 10 All Dutch sentences were part-of-speech (POS) tagged with the memory-based NLP suite Frog (van der Sloot et al. Reference Sloot, Hendrickx, van Gompel, van den Bosch and Daelemans2018. Next, the statistical machine translation software Moses (Koehn et al. Reference Koehn, Hieu Hoang, Chris Callison-Burch, Nicola Bertoldi, Wade Shen, Richard Zens, Bojar, Constantin, Herbst and Ananiadou2007) was used to identify and extract exhaustively all translational correspondences between Dutch and foreign n-grams from the three subcorpora, with n ranging between 1 and 7.Footnote 11 This resulted in three translation tables, which store all such translation “snippets” found across the parallel corpora, as well as a number of translation probabilities derived from their relative co-occurrence frequencies (see Koehn Reference Koehn2009, Hearne & Way Reference Hearne and Way2011 for technical details). Statistically implausible entries were removed using Johnson et al.’s (Reference Johnson, Martin, Foster, Kuhn and Eisner2007) pruning algorithm, based on the significance testing of n-gram co-occurrence frequencies in the parallel corpora. This brought about a dramatic reduction of the original translation tables: from 898.7 million entries down to 62.2 million—a decrease of 93%.

From these resulting data we extracted all pairwise combinations of Dutch n-grams that shared the same translation in English, French or German. Unigrams were discarded, as they lack the minimal amount of context required to identify grammatical patterns, so all paraphrases were between 2 and 7 tokens long. For each paraphrase pair, a conditional paraphrase probability was computed on the basis of their translation probabilities, following Callison-Burch Reference Callison-Burch2007:51. This probability quanti-fies the likelihood that both Dutch n-grams are, in fact, good paraphrases.

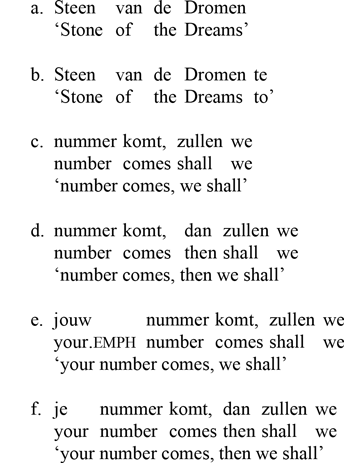

In order to single out paraphrases that manifest grammatical variation, a number of heuristic filters were applied aimed at incre-mentally weeding out noise and various kinds of nongrammatical phenomena. The first set of filters targeted a large proportion of the para-phrases, which exhibited orthographic or purely lexical variation, as in 4. The second set of filters was used to remove redundant paraphrases contained within larger paraphrases (that is, substrings) and to perform “horizontal pruning”, meaning that only the longest possible paraphrases were retained, as in 5b,d,f. Finally, through eyeballing random slices of the resulting dataset, it was decided that instances with a paraphrase probability below 0.05 were too often too low in quality and should therefore be removed from further processing.

(4)

(5)

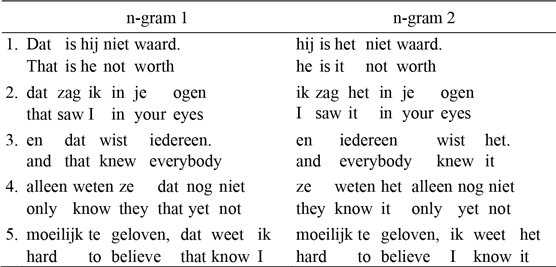

Following this procedure, we were left with 452,828 Dutch paraphrases whose alignment is sufficiently supported by the corpus data, and that are quite likely to exhibit some form of grammatical variation. A slice of our paraphrase dataset is given in table 1.

Table 1. Examples of Dutch paraphrases (English glosses added, POS labels removed for legibility).

The paraphrases in table 1 do not have much in common from a syntactic perspective: Some manifest a change in word order (for example, instances 1 and 2), others the insertion of an extra element (for example, instances 4 and 5). At that point, the dataset was essentially an unordered “bag” of Dutch paraphrases that contained some sort of function word or morphosyntactic alternation.

While it would, in theory, be possible to manually scan all 452,828 paraphrases to detect commonalities among them (as was done in a proof-of-concept study in Grondelaers et al. Reference Grondelaers, Robbert De Troij and van den Bosch2020, albeit for a much smaller dataset), this would hardly be feasible in this case. The second step of our procedure, then, aimed at automatically identifying classes of n-gram pairs that shared the same abstract pattern, or “schema”, as we may call it. Specifically, this was done by abstracting away from the specific lexical items in them and establishing whether the two n-grams within any given pair differed due to substitution, insertion or permu-tation of specific items, or any combination thereof. Let us illustrate this with example 6 (POS labels: LET=punctuation, VG=conjunction, VNW=pronoun, and WW=verb).

(6)

As part of the first step as described above, identical sequences of items within each of the two n-grams were automatically identified and indexed, so that items that do not occur in both n-grams could be separated out. For the paraphrases in 6 that would be dat/VNW and het/VNW, which only occur in n-gram 1 and n-gram 2, respectively. The result is shown in 7; identical (sequences of) items in both n-grams are captured in square brackets, item indices are typeset in subscript. Example 7 shows that not only is there a substitution of items (that is, dat/VNW in n-gram 1 versus het/VNW in n-gram 2), but that the word order is different as well, as becomes clear from the order of the indexed items (that is, 0–1–2 in n-gram 1 versus 0–2–1 in n-gram 2).

(7)

Then we were able to devise a linguistically informed layered classi-fication at two levels of abstraction, as illustrated in 8. The low-level schema in 8a captures all paraphrases whose variable items are all identical (that is, dat/VNW in one n-gram and het/VNW in the other), while the more abstract, high-level schema in 8b groups together all paraphrases whose variable items have the same POS tag(s) (that is, all items tagged as VNW). The feature [+order] indicates that in addition to a lexical substitution, there is also a permutation of items.

(8)

By applying this procedure to all paraphrase pairs in the dataset, larger classes with similar variation patterns can be identified and grouped together. Table 2 comprises a sample of all paraphrase pairs that share the same low-level abstract pattern in 8a. Using tables like these, it is fairly easy to identify patterns of grammatical variation. For instance, in this table, one can easily see that all instances but the fourth one exhibit one variant with sentence-initial dat with verb–subject inversion, and one with postverbal het.Footnote 12

Table 2. Paraphrases featuring sentence-initial dat ‘that’ versus postverbal het ‘it’.

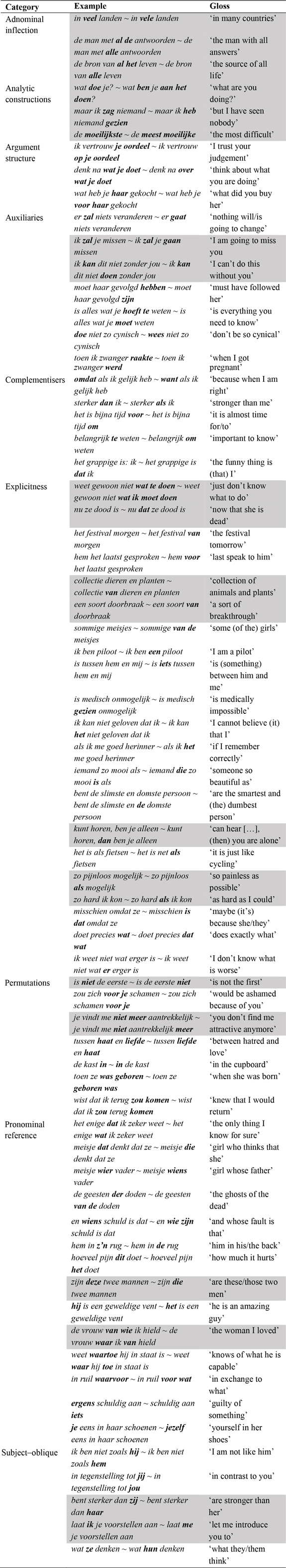

Applying this procedure to the list of paraphrases resulted in 10,734 high-level schemata such as 8b above. These roughly follow a Zipfian distribution, with a few top-ranking ones capturing thousands of para-phrases, while many of the bottom-ranking ones only represent a single paraphrase pair. The 200 most populated high-level schemata, which together contain 400,647 out of the total number of 452,828 paraphrase pairs (88.5%), were eyeballed for well-known and lesser-known patterns of morphosyntactic variation. Examples of each of these are given in the table in the Appendix, manually arranged in a number of categories (for example, adnominal inflection, Analytic constructions, etc.). Note that this arrangement does not reflect any theoretical claims about the internal organization of grammar: It is merely meant as an intuitive foothold for a more orderly exposition of the results. The individual cases in section 4.2 below represent our unit of analysis. That said, it is perfectly possible to read each case study separately.

In the following section, we present corpus studies for 20 alternation patterns, drawn from a number of these categories (the alternations we analyzed are shaded in grey in the Appendix). The patterns were selected on the basis of three primary considerations—two theoretical and one practical. As the first and most important theoretical concern, we were particularly interested in new variables. As “new”, we considered all phenomena whose sensitivity to North–South bias has not, to our knowledge, been the subject of systematic corpus analysis. Thus, section 4.2 features a number of cases which, to the best of our knowledge, have not been sufficiently explored: Either nothing has been claimed or even suggested in the literature thus far, or some tentative claims may have been made, but without the support of satisfactory empirical evidence in the form of corpus analysis. As a second theoretical concern, the variables were selected in such a way that different “corners”, or areas of the grammar are covered, ranging from adnominal inflection over lexically conditioned syntactic phenomena to pure word order variation.

Our third—practical—concern pertained to the feasibility of retriev-ing corpus frequencies to gauge each alternation’s sensitivity to North–South variation. So, in addition to instantiating different types of morphosyntactic variation, we wanted candidate patterns to be fairly cleanly extractable. The 20 variables discussed below are all patterns that could straightforwardly be counted in the corpus using queries that neither underspecified the alternation too much, nor yielded a large proportion of spurious hits. For each case study below, we explicitly mention on which queries the corpus frequencies are based.

As far as the data and method are concerned, we tapped into the 500-million-word SoNaR corpus, which comprises materials from a wide array of text types from both Flanders and the Netherlands (Oostdijk et al. Reference Oostdijk, Reynaert, Hoste, Schuurman, Spyns and Odijk2013).Footnote 13 More specifically, we selected the Flemish and Dutch newspapers and discussion lists components, the details of which are given in table 3.

Table 3. Sizes (in words) of the corpus components used in this study.

By distinguishing between the newspapers and the discussion lists, we implemented a diaphasic dimension in addition to the diatopic dimension introduced previously. We did this because BD and ND are not monostratal entities but display internal heterogeneity (Grondelaers & van Hout Reference Grondelaers and van Hout2011, Grondelaers et al. Reference Grondelaers, van Hout and van Gent2016), and previous research has shown that natiolectal divergences tend to be more pronounced in the “lower” stylistic strata (see Geeraerts et al. Reference Geeraerts, Grondelaers and Speelman1999; Grondelaers et al. Reference Grondelaers, Speelman, Geeraerts, Morin and Sébillot2002, Reference Grondelaers, Speelman, Geeraerts, Kristiansen and Dirven2008; Tummers Reference Tummers2005; Speelman & Geeraerts Reference Speelman, Geeraerts, Sanders and Sweetser2009 for empirical evidence on the lexicon and morphosyntax).

In the following section, we systematically discuss each of the 20 variables arranged in seven parts, reflecting the above-mentioned categories (see also the Appendix).

4. Tracking Natiolectal Variation: Case Studies

4.1. Adnominal Inflection

The first category comprises a number of phenomena exhibiting variable adnominal inflection. Two such phenomena are scrutinized here: inflection of the degree modifier veel ‘many’, as in 9, and the use of inflected alle ‘all’ as opposed to uninflected al ‘all’ followed by a definite article, as in 10.Footnote 14 In the latter case, we discern two constructions, namely, one in which al occurs with the article de and a plural noun, al de + N.c(m/f).pl, shown in 10b, and one in which al occurs with the article het and a singular neuter noun, al het + N.n.sg, illustrated in 10d. To our knowledge, the possibility of natiolectal variation has never been explored for either alternation (see, among others, van der Horst Reference Horst, Schermer-Vermeer, Klooster and Florijn1992, Broekhuis Reference Broekhuis2013:282–283 on veel and vele, and Broekhuis & den Dikken Reference Broekhuis and den Dikken2012:§7.1 on alle and al).

(9)

(10)

For the alternation between veel and vele in 9, we retrieved all instances of either variant preceded by a preposition, so as to exclude contexts where only one of the two forms is possible (as in mijn vele/*veel vrienden ‘my many friends’). Also, we allowed up to one adjective between the quantifier and the following noun. The absolute (N) and relative (%) frequencies of both variants in the four subcorpora are listed in table 4. To assess whether the distribution of the construc-tional alternatives differed in the BD and ND materials, we used a χ2 test of homogeneity (with the customary α level of 0.05); in addition, Cramér’s V was computed as a measure for the association strength (with 0≤V≤1; 0 indicating no association and 1 maximal association).

Table 4. Inflected vele versus uninflected veel ‘many’.

The figures in table 4 reveal that, overall, there is a significantly higher BD preference for the inflected variant vele (χ 2 =457.88, df=1, p<0.001, Cramér’s V=0.15), and that this preference is more pronounced in the discussion lists (χ 2 =270.92, df=1, p<0.001, Cramér’s V=0.26) compared to the newspapers (χ 2 =203.77, df=1, p<0.001, Cramér’s V=0.11). Intrigu-ingly, while the BD discussion lists feature comparatively more instances of inflected vele than the BD newspapers (42.6% versus 30.4%), the converse is true for ND, where the uninflected variant is by far the preferred choice in the discussion lists (10.2% versus 20.8%). This dif-ference in usage may reflect a difference in perception: Flemish writers perceive the uninflected variant as the more formal one, while Dutch writers consider the inflected variant as more apt for formal writing.

Turning to the alternation between alle + N.c(m/f).pl and al de + N.c(m/f).pl, we also restricted our query to instances preceded by a preposition; here, too, allowing up to one adjective before the following noun. From the results listed in table 5, it is clear that inflected alle vastly outnumbers uninflected al de, both in BD and ND. As F. Van de Velde (Reference Van de Velde2014:93–95) argued on the basis of real-time data from the 19th and 20th centuries, al de has been on a steady decline since at least the first half of the 19th century. In this light, its slightly higher present-day proportion in BD (χ 2 =152.21, df=1, p<0.001, Cramér’s V=0.05) should probably be interpreted as a historical remnant, reflecting the fact that the ongoing rise of alle at the expense of al de has progressed somewhat further in ND (newspapers: χ 2 =88.53, df=1, p<0.001, Cramér’s V=0.04; discussion lists: χ 2 =35.62, df=1, p<0.001, Cramér’s V=0.05).

Table 5. Inflected alle versus uninflected al de ‘all (the)’

Finally, let us consider the related alternation between alle + N.n.sg and al het + N.n.sg. Instances were retrieved in a fashion similar to the previous pattern; the results are given in table 6.

Table 6. Inflected alle versus uninflected al het ‘all (the)’.

Unlike al de, al het does not appear to be on the verge of extinction (as its relatively higher proportional frequencies vis-à-vis those of alle reveal). In fact, one sees the opposite picture of al de: The uninflected variant is significantly more frequently used in ND than in BD (χ 2 =295.55, df=1, p<0.001, Cramér’s V=0.25), and the effect is stronger in the discussion lists (χ 2 =101.56, df=1, p<0.001, Cramér’s V=0.28) than in the newspapers (χ 2 =191.31, df=1, p<0.001, Cramér’s V=0.23). Like veel versus vele, preferences for alle versus al het are mirrored for Flemish and Dutch writers when one compares the newspapers and the discussion lists: While in the Flemish discussion lists uninflected forms are used less frequently (12.7% versus 8.7%), they are slightly more frequent in the Dutch discussion lists (34.7% versus 39.3%).

4.2. Analytic Constructions

The second category covers what one may term analytic constructions. Coined by Schlegel in 1818, the notions synthetic and analytic have been employed in “widely different” ways in the literature, as pointed out by Anttila (Reference Anttila1989:315). We adopt Haspelmath & Michaelis’s (2017:8) definition of an analytic pattern as “a morphosyntactic pattern that was created from lexical or other concrete material and that is in functional competition with (and tends to replace) an older (synthetic) pattern.” We focus on two alternations that may be qualified as such. The first one is the competition between morphological superlatives (that is, Adj + st, the synthetic form), shown in 11a, and periphrastic ones (that is, meest ‘most’ + Adj, the analytic form), shown in 11b.

(11)

According to van der Horst (Reference Horst2008:1091, 1647–1648), the periphrastic superlative in 11a is a fairly recent innovation (from a long-term diachronic perspective, that is; the author’s earliest examples date from the 18th century). He asserts that the construction has been gaining momentum especially rapidly during the 20th century, without, however, providing satisfactory evidence for this claim. Additionally, he cites Willem De Vreese’s (1899) book on gallicisms in BD, where it is claimed that periphrastic superlatives are more typical of BD due to a more intensive language contact with French (see De Vreese Reference De Vreese1899:452–459, cited in van der Horst Reference Horst2008:1648—though van der Horst himself questions the validity of this claim). As far as we know, this latter claim has never been the object of empirical research.Footnote 15

The second analytic pattern is the simplex present tense form used to express progressive aspect, as in 12a, which is in competition with the older synthetic construction aan het ‘at the’ + bare infinitive, as in 12b.Footnote 16

(12)

Compared to the previous case, the simplex present tense form constitutes a less typical example of analyticization because it is not clear whether the form in 12b is diachronically “encroaching” on the form in 12a. Moreover, the form in 12a does not feature any overt (morpho-logical) marker of progressive aspect (like the -st suffix in morphological superlatives). Nonetheless, given that the pattern in 12b is made up of complex lexical material and is in a functional competition with the form in 12a (with the adjuncts dag na dag ‘day after day’ and verder ‘further, increasingly’ triggering a progressive reading)—thus complying with most of Haspelmath & Michaelis’s criteria of analyticity—we treat this case in the present subsection.

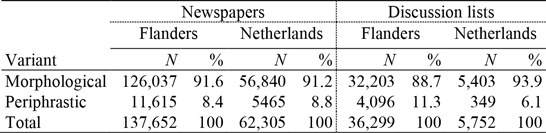

Starting off with the superlatives, we searched for all forms of attributively used adjectives—either a positive form preceded by meest ‘most’ or a morphological superlative except for achterste ‘back, hind-most’, benedenste ‘down(most)’, beste ‘best’, binnenste ‘inner(most)’, bovenste ‘upper(most)’, buitenste ‘outer(most)’, eerste ‘first’, laatste ‘last’, middelste ‘middle(most)’, minste ‘least’, naaste ‘nearest’, onderste ‘bottom’, opperste ‘upper(most)’, uiterste ‘utmost’, and voorste ‘fore-most,’ as these have no periphrastic counterpart (Haeseryn et al. Reference Haeseryn, Kirsten Romijn, de Rooij and van den Toorn1997:416). The results are given in table 7.

Table 7. Morphological versus periphrastic superlatives.

As to the overall distribution of the two variants in the BD and ND materials, the statistical test reaches significance, but the effect size is very weak (χ 2 =14.44, df=1, p<0.001, Cramér’s V<0.01). This is especially the case if one looks only at the newspapers (χ 2 =6.10, df=1, p=0.013, Cramér’s V<0.01); in the discussion lists, however, the difference is somewhat larger, with Flemish writers using slightly more periphrastic forms (χ 2 =142.93, df=1, p<0.001, Cramér’s V=0.06), which dovetails with De Vreese’s claim and parallels De Smet’s findings regarding Präteritumschwund in spoken Dutch (see note 15).

Moving on to the two forms that express the progressive aspect, we refrained from calculating the proportion of aan het + bare infinitive vis-à-vis the simplex present tense form, because the latter is used in a wide range of contexts in which a progressive reading is not possible. Instead, we computed the text frequency in the four subcorpora (that is, the rate of occurrence per million words) of the pattern aan het preceded by a form of the verb zijn ‘to be’ within a span of five words and followed by an adjacent bare infinitive. This rate of occurrence provides a measure of the construction’s prevalence in the Flemish and Dutch sources, irrespective of the present tense construction with progressive reading.

The results are listed in table 8 (see also table 3 for the total sizes of the subcorpora).

Table 8. Aan het ‘at the’ + bare infinitive (per million words).

The isolated frequencies in table 8 inevitably paint a less clear picture than the variant distributions that were hitherto used. In addition, they show widely different rates of occurrence in the four subcorpora. Overall, it appears that aan het + bare infinitive is somewhat more prevalent in the discussion lists, especially in the ND materials.Footnote 17 By contrast, its text frequency is higher in the Flemish newspapers than in the Dutch ones.

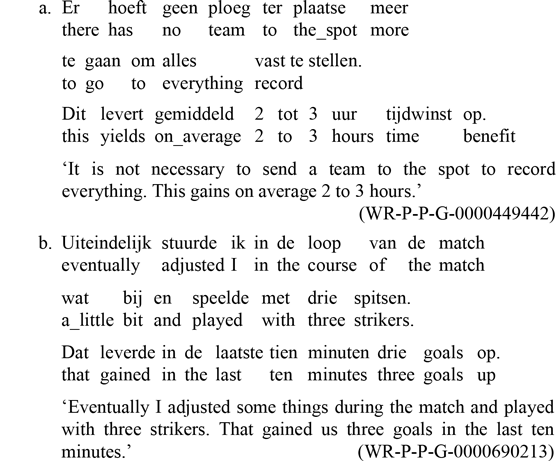

4.3. Auxiliaries

The third category in this overview pertains to auxiliation. Two phenomena are investigated here. The first one is the use of gaan ‘go’ as a complement of the future auxiliary verb zullen ‘will’, as illustrated in 13. According to Haeseryn et al. (Reference Haeseryn, Kirsten Romijn, de Rooij and van den Toorn1997:979f.), this combination of zullen and gaan is “definitely not uncommon.” No regional differences are mentioned, although it is well known that gaan itself as a future marker is more productive in BD (for example, Colleman Reference Colleman, De Tier, Devos and Van Keymeulen2000, Fehringer Reference Fehringer2017). The second one involves complementation of modal verbs such as kunnen ‘can, be able to’ and mogen ‘may, be allowed to’. In some cases, there is no main verb following the modal, and so the modal seems to act as the main verb, as in 14a (see Nuyts Reference Nuyts2014 on “autonomously” used modals). In other cases, the modal verb occurs with a semantically underspecified doen ‘do’ as the main verb, as shown in 14b. This particular case of variation is rarely addressed in the literature, and at first glance it is not clear whether one should expect natiolectal variation.

(13)

(14)

For the zullen + gaan case, we searched for all instances of a finite present tense form of the verb zullen immediately followed by either an infinitive that is not gaan or gaan and another immediately adjacent infinitive. The results are given in table 9.

Table 9. Zullen ‘will’ (+ gaan ‘go’) + infinitive.

The figures show—contra Haeseryn et al. Reference Haeseryn, Kirsten Romijn, de Rooij and van den Toorn1997—that the combination of zullen and gaan is quite marginal in comparison to the highly frequent zullen without gaan, at least in the newspapers and the discussion lists we excerpted. Overall, the zullen + gaan pattern is somewhat more prevalent in ND, but the effect size is very small (χ 2 =479.73, df=1, p<0.001, Cramér’s V=0.06). Again, the effect is slightly larger in the discussion lists (χ 2 =228.44, df=1, p<0.001, Cramér’s V=0.10) than in the newspapers (χ 2 =384.41, df=1, p<0.001, Cramér’s V=0.06).

For the modal + doen case, like the progressive constructions treated above, we took a different approach. A search for any form of the modals kunnen ‘can’, moeten ‘must’, willen ‘want’, and mogen ‘may’ followed by a demonstrative pronoun dat ‘that’ and optionally the negator niet ‘not’ yielded too many cases that do not feature the alternation at hand (for example, Alleen in Zelzate mag dat niet ‘Only in Zelzate that is not allowed.’ [WR-P-P-G-0000683457]). Therefore, we calculated the rate of occurrence of the pattern modal + dat (+ niet) + doen in each of the subcorpora; table 10 displays the results.

Table 10. Modal (+ doen ‘do’) (per million words).

Unfortunately, this pattern appears to be highly infrequent in our selection of SoNaR, with an average of only one occurrence per million words. Hence, we are at present not able to assess whether there are differences between BD and ND (for example, in terms of the individual modals that can combine with doen, or the linguistic contexts in which either variant is preferred); this is an area for future research.

4.4. Explicitness

The fourth category comprises a heterogeneous set of alternations for which one of the variants can be considered the syntactically more explicit option featuring additional elements. The sentences in 15 exem-plify the use of an expletive dat ‘that’ after subordinating conjunctions. Haeseryn et al. (Reference Haeseryn, Kirsten Romijn, de Rooij and van den Toorn1997:361) and Taeldeman (Reference Taeldeman2008:36) mention that expletive dat following interrogative pronouns and pronominal adverbs is a typical feature of colloquial BD.Footnote 18 For this case study, we shift the focus to temporal conjunctions, in particular, nu (dat) ‘now’, toen (dat) ‘then’, and sinds (dat) ‘since’, all featuring frequently in the OpenSubtitles2018 paraphrases. According to van der Horst (Reference Horst2008:983–1016), these subordinating conjunctions have grammaticalized from so-called correlative uses of adverbs (compare present-day Dutch Toen er niemand bleek te zijn, toen gingen ze maar naar huis ‘When it appeared that no one was there, then they just went home.’), with dat probably being added in a later stage as a marker of subordination, possibly by analogy with conjunctions such as zodat with incorporated dat (< zo ‘so’ + dat ‘that’) and terwijl (dat) ‘while’ (< ter + wilen + dat lit. ‘to the while that’). At some point, the adverb (or adverbial phrase) probably assumed the function of the subordination marker, such that dat essentially became vacuous and was increasingly dropped.Footnote 19 Again, the fact that the expletive dat still features heavily in present-day (colloquial) BD (see De Decker & Vandekerckhove Reference De Decker and Vandekerckhove2012) tallies with the idea that obsolescent features of the grammar are retained longer in BD (see also the slightly better preservation of al de in BD; section 4.1).

(15)

Table 11 gives the frequencies of sentence-initial occurrences of the three temporal conjunctions, nu ‘now’, toen ‘then’, and sinds ‘since’, optionally followed by dat and immediately followed by a personal pronoun (to avoid cases in which nu (dat) is not a temporal conjunction, as in Nu dat weer ‘Now that again’ [WR-P-P-G-0000176199]).

Table 11. Expletive dat ‘that’ after conjunctions nu ‘now’, toen ‘then’, and sinds ‘since’.

Overall, there is no statistically significant difference between BD and ND (χ 2 =1.95, df=1, p=0.162), due to the near absence of the expletive variant in the newspaper materials (χ 2 =0.83, df=1, p=0.364; the four Flemish cases are all instances of nu dat). In the discussion lists, by contrast, the expletive dat occurs significantly more frequently in BD than in ND, albeit still rather sparingly, in only 1.6% of the cases (χ 2 =11.78, df=1, p<0.001, Cramér’s V=0.06).Footnote 20

The second variable captures various complementation patterns of weten wat ‘know what’, which can be a te-infinitive, as in 16a, or a finite construction with the modal auxiliary moeten ‘must’ and a bare infinitive, as in 16b. The variant in 16b may be considered the more explicit one, because it features a repeated subject in the subordinate clause and an extra finite verb. Haeseryn et al. (Reference Haeseryn, Kirsten Romijn, de Rooij and van den Toorn1997:1104) mention a third variant with a past participle, which, moreover, is allegedly restricted to BD (as in Verzamelaars weten wat gedaan ‘Collectors know what done’ [WR-P-P-G-0000586437]). There is even a fourth variant with a bare infinitive (as in Je weet wat doen ‘You know what [to] do’ [WR-P-P-G-0000281111]). However, neither of these latter two variants cropped up in the OpenSubtitles2018 data, so for the present analysis we restricted ourselves to the two alternatives in 16.

(16)

We searched for all forms of weten ‘know’ that were preceded or followed by a pronominal subject (so as to include inverted word order as well), optionally followed by the negator niet ‘not’ and up to one other unspecified word, followed by the wh-word wat and either a te-infinitive or a personal pronoun, a form of moeten ‘must’, and an infinitive (the red order) or the other way round (the green order). We made sure the matrix subject and the subject of the subordinate clause were coreferential. The counts are given in table 12.

Table 12. Complement of (niet) weten wat ‘(don’t) know what’.

Across the newspaper and discussion list materials, complementation with a te-infinitive is significantly more frequent in BD (χ 2 =12.01, df=1, p<0.001, Cramér’s V=0.19). While this difference is also clearly mani-fested in the newspapers (χ 2 =4.86, df=1, p=0.027, Cramér’s V=0.15), it is even more pronounced in the discussion lists, where it is used in over half of the cases (χ 2 =9.47, df=1, p=0.002, Cramér’s V=0.27). Taking into consideration that a construction with a past participle as well as one with a bare infinitive can also be used in BD (van der Horst Reference Horst2008:1803)—both allegedly absent in ND—one may hypothesize that Flemish speakers have a preference for more compact non-finite comple-mentation patterns, whereas speakers of ND prefer longer structures with an extra finite verb in the form of the modal auxiliary moeten ‘must’.

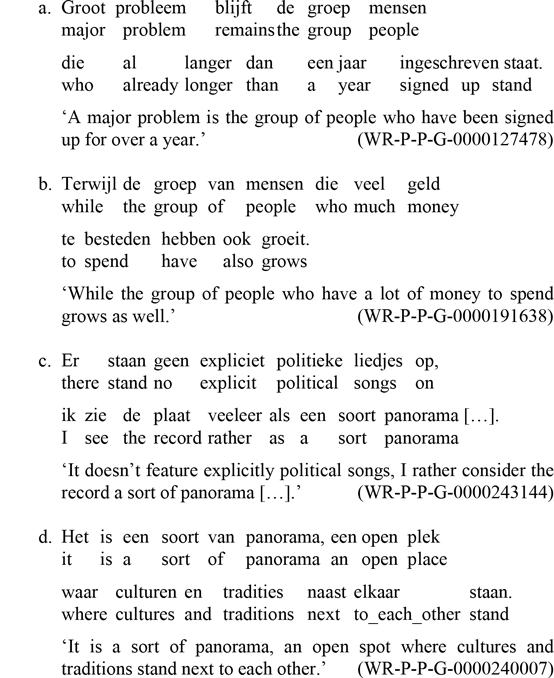

Moving on, the sentences in 17 illustrate an alternation between what one may term bare binominal NPs, that is, NPs consisting of two adjacent nouns (N1 and N2), as in 17a,c, and prepositional binominal NPs, in which N1 and N2 are separated by the preposition van ‘of’, as in 17b,d. We further distinguish between quantifying binominals, with a collective noun as N1 (groep ‘group’ and collectie ‘collection’), as in 17a,b, and qualifying binominals, with a type noun as N1 (soort ‘sort’ and type ‘type’), as in 17c,d (see Broekhuis & den Dikken Reference Broekhuis and den Dikken2012:575, 631–637).

In an analysis of binominals with soort, De Troij & F. Van de Velde (2020) show that over the past 170 years or so, the bare variant has rapidly ousted the prepositional variant, which used to be the only form before ca. 1850 but is the marked option nowadays. In this regard, Schermer-Vermeer (Reference Schermer-Vermeer2008:12, note 17) hypothesizes, based on judgments of a small panel of informants, that the prepositional variant in qualifying binominals might (still) be more common in BD. The correctness of this hypothesis again would be in line with the idea that in some cases, BD holds on to obsolescent material longer than ND.

(17)

For the quantifying binominals, we retrieved all instances of the nouns groep and collectie (and their plural forms), both with and without van, and a plural N2, optionally preceded by one adjective. Corpus counts are given in table 13. Overall, the proportional frequency of the prepositional variant is significantly higher in BD (χ 2=82.33, df=1, p<0.001, Cramér’s V=0.08), and once again the association is stronger in the discussion lists (χ 2 =15.02, df=1, p<0.001, Cramér’s V=0.09) than in the newspapers (χ 2 =51.15, df=1, p<0.001, Cramér’s V=0.07).

Table 13. Quantifying (collective) binominals

For the qualifying binominals (soort and type), instances were gathered in an identical fashion, except that N2 could also be a singular noun, as shown in table 14. One can observe a similar picture as with the quantifying binominals, with the prepositional variant being generally more frequent in BD, but here, the overall difference is slightly larger (χ 2 =541.43, df=1, p<0.001, Cramér’s V=0.12). Moreover, the prepo-sitional variant is very infrequent in the Dutch newspapers, accounting for a mere 1.7% of the cases (χ 2 =285.23, df=1, p<0.001, Cramér’s V=0.11). In the discussion lists, the prepositional variant is again somewhat more common, and the difference between BD and ND is slightly larger (χ 2 =168.90, df=1, p<0.001, Cramér’s V=0.12). These findings concur with the hypothesis expounded above, namely, that BD holds on to older variants longer than ND.

Table 14. Qualifying binominals.

Next, we turn to the sentences in 18, which showcase the variable insertion of dan ‘then’ in the apodosis of a conditional clause (that is, syntactic integration in 18a versus resumption in 18b; see Renmans & Van Belle Reference Renmans and Van Belle2003 with reference to König & van der Auwera Reference König, van der Auwera, Haiman and Thompson1988).

(18)

We retrieved from SoNaR all sentences starting with als ‘if’ and a main verb within a span of ten words, optionally followed by dan ‘then’, another main verb, and a subject personal pronoun. Table 15 reveals that, overall, syntactic resumption is slightly more frequent in BD, but the association strength is weak (χ 2=87.31, df=1, p<0.001, Cramér’s V=0.04). Once more, the difference is more pronounced in the discussion lists (χ 2 =86.31, df=1, p<0.001, Cramér’s V=0.06)—where resumption is more common both in BD and ND—than in the newspapers (χ 2 =44.01, df=1, p<0.001, Cramér’s V=0.03).

Table 15. Integration versus resumption with dan ‘then’.

As the final case of what we have been referring to as explicitness, consider the sentences in 19. In degree adverbials like these, an extra conjunction als can appear between the adverb and the modal, as in 19a and 19b. A provisory investigation of this variable (Grondelaers et al. Reference Grondelaers, Robbert De Troij and van den Bosch2020:85–86) suggested that the variant with als may be proportionally preferred in ND, but in that analysis, register was not taken into account.

(19)

Here, we extracted all occurrences of the degree adverb zo ‘so’ + an adjective, optionally als ‘as’, and finally a subject personal pronoun and a form of the modals kunnen ‘can’, moeten ‘must’, mogen ‘may’, or willen ‘want’. Table 16 gives the distribution of each variant in the SoNaR components.

Table 16. Zo ‘so’ + adverb (+ als ‘as’) + modal verb.

Overall, the earlier findings from Grondelaers et al. Reference Grondelaers, Robbert De Troij and van den Bosch2020 are replicated: The als variant is comparatively more frequent in ND than in BD (χ 2 =11.88, df=1, p<0.001, Cramér’s V=0.11). Looking at the newspapers and discussion lists separately, one can observe that there is a stronger preference to use the variant without als in the discussion lists, both in BD and ND, suggesting that als is more typical of formal writing in both varieties (newspapers: χ 2 =4.68, df=1, p=0.030, Cramér’s V=0.09; discussion lists: χ 2 =4.00, df=1, p=0.046, Cramér’s V=0.10).

4.5. Word Order Alternations

The fifth category groups a number of phenomena exhibiting a word order alternation. We analyze two alternations involving the negator niet ‘not’. The first case pertains to the relative position of niet to predicative definite NPs following the copula zijn ‘to be’: It either occurs in prenominal position, as in 20a, or in postnominal position, as in 20b. The second case pertains to the continuous versus discontinuous realization of niet meer ‘not anymore’: Either both elements occur before the negated constituent—we restrict the analysis here to adjectives—as in 21a, or the constituent can be placed in between both elements, as in 21b.

(20)

(21)

It has been pointed out in some older work (Koelmans Reference Koelmans1970, Braecke Reference Braecke, Devos and Taeldeman1986:36–38) that a rightmost placement of niet in the midfield of the sentence is more typical of BD, irrespective of the scope of the negation (see also Haeseryn et al. Reference Haeseryn, Kirsten Romijn, de Rooij and van den Toorn1997:1342).Footnote 21 Based on this tendency, we expect a higher proportion of postnominal niet in BD. Regarding the variation in 20c,d, no clear hypothesis can be formulated on the basis of Haeseryn et al.’s (Reference Haeseryn, Kirsten Romijn, de Rooij and van den Toorn1997:1343) statement that the “preference for one of both variants can differ individually and/or regionally.”Footnote 22

For the alternation exemplified in 20, we searched for a (pro)noun, followed by a form of the copula zijn ‘to be’, followed by a definite NP (that is, a sequence of a definite article, possibly one adjective, and a noun); niet could occur either before or after the NP. The results are given in table 17. Starting again by looking at the overall distribution of both variants, there is no statistically significant difference between the Flemish and Dutch materials (χ 2=1.63, df=1, p=0.201). This result is due to the newspapers, where the BD and ND distributions are almost identical (χ 2=0.75, df=1, p=0.387). In the discussion lists, by contrast, there is a statistically significant difference, with postnominal niet being proportionally more frequent in ND (χ 2=6.58, df=1, p=0.010, Cramér’s V=0.11). The latter is a surprising finding in light of the hypothesis that rightmost placement of niet is more typical of BD (see section 4.4).

Table 17. Prenominal versus postnominal niet ‘not’.

For the second alternation, shown in 21, we searched for instances of niet meer followed by an adjective—the continuous variant—and instan-ces in which an adjective occurs between niet and meer—the discontinuous variant. The results appear in table 18.

Table 18. Continuous versus discontinuous niet + meer ‘not (…) anymore’.

Overall, there is no statistically significant difference between BD and ND (χ 2 =2.71, df=1, p=0.100). Looking at the newspapers and discussion lists separately, one can see that the former manifest no differences (χ 2 =0.70, df=1, p=0.404), but the latter do, with the discontinuous variant being more frequent in ND (χ 2 =15.60, df=1, p<0.001, Cramér’s V=0.06).

4.6. Pronominal Reference

The sixth category contains several phenomena that have to do with pronominal reference. We address three cases of variation. First, the use of dat as opposed to wat as a relative pronoun referring to neuter singular nouns, as illustrated in 22. This variation is reflecting the end stage of a long-term shift from d-relativizers to w-relativizers in Dutch, which is assumed to have taken off in and around the 13th century (van der Horst Reference Horst1988:198). At present, the variant in 22b is widely used, especially in spoken informal ND, while it is allegedly rather marginal in BD (Haeseryn et al. Reference Haeseryn, Kirsten Romijn, de Rooij and van den Toorn1997:339), which suggests that this shift has progressed further in ND than in BD. This seems to be another case where BD holds on longer to obsolescent features of the grammar.

(22)

Second, we look at proximal versus distal anaphoric pronouns in sentence-initial position exemplified in 23. Kirsner (Reference Kirsner1979:73) argues that proximal forms such as deze and dit more strongly urge the hearer to find a referent than the distal forms die and dat (see also Ariel Reference Ariel1990:51, 73). In light of the BD over-coding hypothesis introduced in section 2, we expect the option with the stronger deictic in 23a to feature more frequently in BD (see also Haeseryn et al. Reference Haeseryn, Kirsten Romijn, de Rooij and van den Toorn1997:308).

(23)

Third, we investigate the use of Prep + wie ‘who’ versus a pro-nominal adverb, that is, waar-Prep in reference to a human antecedent, as illustrated in 24. So far as we know, no reference to natiolectal variation is made in the literature, and Haeseryn et al. (Reference Haeseryn, Kirsten Romijn, de Rooij and van den Toorn1997:496) mention that 24b is primarily restricted to informal language. As such, it could be expected that the stylistic dimension will turn out to be the most important one here, rather than the natiolectal dimension.

(24)

Starting with the variation between dat and wat exemplified in 22, we searched for sentence-initial occurrences of a neuter noun, except for feit ‘fact’, moment ‘moment’, gevoel ‘feeling’, and idee ‘idea’ as these are frequently used in combination with an invariable conjunction dat in the OpenSubtitles2018 data. The relative pronouns dat or wat had to be followed by a personal pronoun. The results are presented in table 19. We find that, overall, there is a statistically significant difference between BD and ND (χ 2 =89.89, df=1, p<0.001, Cramér’s V=0.22), but this difference is largely due to the discussion lists (newspapers: χ 2 =6.46, df=1, p=0.011, Cramér’s V=0.07; discussion lists: χ 2 =91.08, df=1, p<0.001, Cramér’s V=0.45): While wat is prevalent in the writing by the Dutch writers, it is (still) quite infrequent among the Flemish (39.4% versus 4.1%). Once again, the obsolescent form holds out longer in BD.

Table 19. Relative pronoun dat ‘that’ versus wat ‘what’ in reference to singular neuter nouns.

For the use of proximal versus distal anaphors, we searched for all sentence-initial occurrences of either a proximal (dit, deze, dees) or a distal (die, dat, da) form, followed by a main verb. Table 20 shows that distal forms are the majority variant in both BD and ND, but proximal forms are slightly more frequent in ND than in BD (χ 2 =277.63, df=1, p<0.001, Cramér’s V=0.03). In fact, the proportional difference between both varieties is slightly larger in the newspapers (χ 2 =706.68, df=1, p<0.001, Cramér’s V=0.05), than in the discussion lists, where there is hardly any difference (χ 2 =13.90, df=1, p<0.001, Cramér’s V=0.01).

Table 20. Proximal versus distal anaphors.

Table 21 lists the frequencies for the third variable. The analysis is based on four frequent human antecedents attested in the OpenSubtitles2018 data, namely, iemand ‘someone’, man ‘man’, vrouw ‘woman’, and persoon ‘person’, followed by one of the prepositions om ‘to, for’, voor ‘for’, met ‘with’, and op ‘on’. Either these were followed by wie ‘whom’, or they were preceded by waar- ‘where’.

Table 21. Relativization of human antecedents.

The overall difference between the BD and ND distribution of both variants is statistically significant (χ 2 =34.29, df=1, p<0.001, Cramér’s V=0.20). The association strength is higher in the discussion lists (χ 2 =7.41, df=1, p=0.006, Cramér’s V=0.16) than in the newspapers (χ 2 =9.82, df=1, p=0.002, Cramér’s V=0.13). As table 21 reveals, the variation in 24 is indeed determined by style, with the informal option (Haeseryn et al. Reference Haeseryn, Kirsten Romijn, de Rooij and van den Toorn1997) being the majority choice in the discussion lists. Crucially, though, there is also a clear natiolectal factor, with 24b being systematically more frequent in BD sources than in ND ones.

4.7. Subject–Object Alternations

Finally, the seventh category subsumes what we refer to as subject–object alternations, from which we investigate two alternation patterns. First, a well-known phenomenon from the prescriptive literature, namely the use of subject versus object personal pronouns following a comparative, as shown in 25.Footnote 23 The variant in 25b is rejected by prescrip-tive grammarians, on account of an elided zijn ‘to be’ (compare ouder dan ik/*mij ben ‘older than I/*me am’). As such, we expect first and foremost a register difference, with the norm-sensitive newspapers banning 25b almost completely.

(25)

Second, we consider the so-called hortative construction with laten ‘let’ in sentence-initial position, which can either occur as a plural laten, with the 1st person plural subject, as in 26a, or as a singular imperative laat, with the 1st person plural object, as in 26b. With regard to the laten alternation, Haeseryn et al. (Reference Haeseryn, Kirsten Romijn, de Rooij and van den Toorn1997:1020) mark the variant in 26b as more typical of formal language use, which F. Van de Velde (Reference Van de Velde2017:69) explains as “due to the fact that there is [an] ongoing shift in which [26b] loses terrain to [26a], and that this leads to a predictable register difference with the old form regarded as more formal.”

(26)

Table 22 lists the results of a corpus search for instances of a comparative followed by dan or als or, alternatively, the form (net) (zo-) als ‘(just) like’ followed by a subject or object personal pronoun. The instances featuring an object pronoun were manually checked to ensure that instances in which the object pronoun actually functioned as object were excluded. As is clear from table 22, object pronouns following comparatives are overall more frequent in BD than in ND (χ 2=193.64, df=1, p<0.001, Cramér’s V=0.17). As expected, this variant features more frequently in the discussion lists than in the newspapers, but in both text types it is used more by Flemish writers (newspapers: χ 2=80.74, df=1, p<0.001, Cramér’s V=0.15; discussion lists: χ 2=104.79, df=1, p<0.001, Cramér’s V=0.18).

Table 22. Subject versus object pronouns following comparatives.

For the laten alternation, we searched for all occurrences of sentence-initial laat ons or laten we, followed by an infinitive and a conjunction (so as to avoid permissive or causative constructions of the type Laat ons weten wat u voortaan anders gaat doen ‘Let us know what you’re from now on going to do differently’ [WR-P-P-G-0000379571]). Table 23 lists the results.

Table 23. Hortative laten ‘let’ with subject or object pronoun

The figures show that, while laat ons is hardly used in ND, it is the majority choice in BD (χ 2 =147.59, df=1, p<0.001, Cramér’s V=0.37). Comparing the two types of texts across the two subcorpora, we can see that this difference is even larger in the newspapers (χ 2 =137.65, df=1, p<0.001, Cramér’s V=0.45) than in the discussion lists (χ 2 =22.24, df=1, p<0.001, Cramér’s V=0.23). The fact that laat ons is more frequent in at least the Flemish newspapers is in line with what we expect on the basis of F. Van de Velde’s quote above. That laat ons is rapidly on its way out in ND—or at least substantially narrowing down its former lexical and semantic coverage—is not only apparent from the low token frequencies, but also from the fact that the two occurrences in the Dutch sources are instantiations of the highly grammaticalized expression laat ons hopen (dat) ‘let us hope (that)’.

5. Overview of the Main Findings

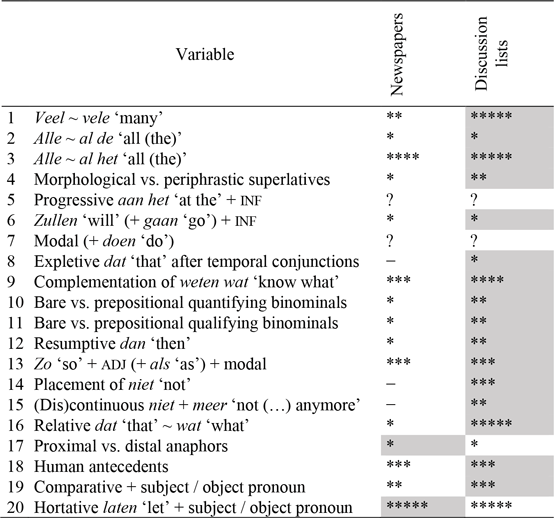

In this paper, we applied an unsupervised machine translation procedure to extract from bilingual parallel subtitle corpora nonlexical and nonidio-matic Dutch paraphrase pairs that align with English, French, or German n-grams (see section 3). After weeding out as much nonessential information as automatically possible, we ended up with over 10,000 basic alternation schemata (that is, high-level schemata; see example 8b in section 2), the 200 most frequent of which (representing 88.5% of the paraphrases originally extracted) were subsequently scrutinized for theoretically and practically representative patterns that could further be examined for their natiolectal sensitivity. The 20 variables eventually analyzed are listed in table 24, which reports, per alternation pattern, the magnitude of the proportional differences between BD and ND in both the newspapers and the discussion lists, indicated with one or more asterisks (with * for<5%, ** for≥5 and<10%, *** for≥10 and<20%, **** for≥20 and<30%, and ***** for≥30%). When there is no significant difference or when the effect size is negligibly low, we use a minus sign (“−”). The question marks for cases 5 and 7 indicate that at present, we were unable to gather sufficient evidence to make any claims about potential natiolectal differences. Finally, we also indicate, by means of grey shading, in which text type the differences are most pronounced (in terms of the largest Cramér’s V).

Table 24. Overview of the results.

Recall that our initial pattern identification method was automatic and unsupervised, and—as such—ideologically and theoretically completely neutral. The 20 alternation patterns that were retained for further natiolectal investigation were selected in function of newness, representativeness, and extractability (not, again, in terms of any potential sensitivity to North–South variation). Still, all of the investigated alternations, except for two inconclusive ones, manifested significant natiolectal skewing; for three variables (8, 14, and 15), there were no real differences in the most formal newspaper materials, with the North–South skewing being situated at more informal levels.

If anything, the data in table 24 explicitly endorse Haeseryn’s (1996:123) conclusion that there are “considerably more cases” of natiolectal variation in the grammar of Dutch than is commonly assumed. The fact that asymmetries are always probabilistic and tend to be comparatively modest in more formal sources, such as newspapers, is offset by typically (much) larger differences in more informal settings, such as online discussion fora. Since, in the latter case, the data reflect unpremeditated spontaneous constructional choices (rather than careful conscious decisions), the conclusion that BD and ND are morphosyn-tactically (much) more divergent than hitherto anticipated is inescapable. In this respect, the variables in table 24 confirm the correlation between contextual informality and increasing North–South divergence attested in earlier studies—for example, on the distribution of the presentative er ‘there’ (Grondelaers et al. Reference Grondelaers, Speelman, Geeraerts, Morin and Sébillot2002, Reference Grondelaers, Speelman, Geeraerts, Kristiansen and Dirven2008), adjectival inflection with neuter nouns (Tummers Reference Tummers2005), as well as on the alternation between the causa-tive auxiliaries doen ‘do’ and laten ‘let’ (Speelman & Geeraerts Reference Speelman, Geeraerts, Sanders and Sweetser2009).