Around the middle of the sixteenth century, a guest of the French court could expect to be dazzled by the newly expanded and redecorated Château de Fontainebleau. First François I and later his son Henri II spent considerable sums enticing Italian artists to migrate to France, and these artists and craftsmen brought with them knowledge of the latest Italian Renaissance fashions. A visitor treated to an evening of entertainment would marvel at the splendor of the Salle de Bal (Figure 1), the sumptuous grand ballroom featuring a coffered ceiling, pillars wrapped in oak paneling and walls covered in frescoes depicting stories drawn from Classical mythology. This room – a conspicuous show of wealth – was illuminated by sparkling gilded bronze lamps and chandeliers. Upon entering the ballroom, her or his body would be warmed by a monumental fireplace situated at the far western end of the room, ornamented with bronze satyrs copied from Classical Roman statues.Footnote 1 While absorbing the grandeur of these sights, the guest’s sense of hearing would also be stimulated by an instrumental ensemble. The musicians, however, would not be immediately visible to those entering the hall, creating a sense of suspense as sound resonated throughout the substantial room.Footnote 2 Only after entering the ballroom could the visitor turn to see the instrumentalists on the gallery above the main entrance (Figure 2). Guests would then become an active part of the visual and aural spectacle by joining the feasting and dancing. The ballroom offered a multi-sensory experience that sought to impress upon a visitor the wealth of the French crown and to project an image of a culturally refined court. Even today this opulent space retains its power to overwhelm the senses of a visitor. The contributions of the so-called School of Fontainebleau, as the Mannerist style developed by imported Italian artists like Rosso Fiorentino, Francesco Primaticcio and Niccolò dell’Abbate became known, are a persistent reminder of the royal project of attracting artists from Italy to serve France.Footnote 3

Figure 1 The Salle de Bal, Château de Fontainebleau.

Figure 2 The musicians’ gallery, Salle de Bal, Château de Fontainebleau.

A fresco on the wall behind the musicians’ gallery (Figure 2), based on Primaticcio’s design and completed by dell’Abbate between 1552 and 1556, depicts two musicians playing large violes, a visual souvenir of the music that once resounded in this space. While they are not the earliest viols depicted in French iconography, they do parallel a recent change instituted by Henri II to his musique de Chambre. In 1547, the first year of his reign, Henri II added two ‘joueurs de violes’ by reassigning Jean Bellac and Pierre de Champgilbert, alias Pierre d’Auxerre, two players of the violon in the Écurie, as players of violes in the Chambre.Footnote 4 The move from the Écurie to the Chambre was not a lateral move and came with a salary increase for the two musicians.Footnote 5 At the same time that the king was updating the ballroom to reflect contemporary Renaissance trends in architecture, the plastic arts and painting, he was also instituting changes to royal musical establishments to produce modern music on instruments then in vogue among the Italian nobility. As I will show, around the middle of the sixteenth century bourgeois amateurs, following the example of the court, adopted the viol as an instrument of leisure and refinement both in their homes and in educational and spiritual initiatives.

The presence of viols in sixteenth-century France has long fascinated scholars, who have surveyed iconography and analysed treatises and tutors.Footnote 6 Scholars working on musicians and music at sixteenth-century French courts have unearthed court records that flesh out our knowledge of the names of musicians, which instruments they played and when they were active at the court.Footnote 7 Others have identified active luthiers and analysed inventories of instruments.Footnote 8 Even the most exhaustive histories of the viol, however, still treat French Renaissance viols as a tangent to an overarching narrative, and as a result our understanding of the origins of the instrument in France and the roles the instrument played socially at court, with an urban bourgeoisie and in educational initiatives remains murky and piecemeal. This deficiency is not the result of a dearth of source material, but rather due in part to the lack of focussed study of the instrument in sixteenth-century France.Footnote 9 The failure of scholars of the viol to produce such a study has been due to several reasons: the lack of extant historical instruments to study (as opposed to Italian instruments from the same period, even if they have been significantly modified); the absence of dedicated solo and chamber repertoires (such as the English lyra-viol and consort repertoires) or a documented virtuosic improvised tradition for the instrument (such as the practice of viola bastarda in Italy); and the fact that France’s five-string Renaissance viols tuned in fourths do not fit neatly into dominant historiographies of the instrument.Footnote 10

I argue that the viola da gamba, like Renaissance architecture, sculpture, ceramics, garden design and painting, was imported to France from northern Italy. The transalpine migration of instrumentalists and the acquisition of prized Italian string instruments was part of a larger project of adapting the latest Italian Renaissance fashions to the aims of the French court. These policies, which were instituted by François I but continued throughout the sixteenth century, cultivated humanism to change the reputation of the French court from one of barbarism and brutality in arms to one that was civilised, elegant and refined. The collecting of Italian artisans and artworks was shaped by François I’s travels in Italy but also by a strong Italian presence at the French court, especially by the middle of the century under the influence of Catherine de’ Medici.Footnote 11

After examining the strategies employed in the royal project of rejuvenating the image of the French court, I explore two spheres of viol development: at the court and in bourgeois musicking and education.Footnote 12 At court viols and lutes signified noble leisure and refinement, and they were deployed in public spectacles and for diplomatic events. The recruitment of the luthier Gaspar Duiffoprugcar from northern Italy to Lyon suggests that François I or Henri II sought to bring the latest innovations in Italian instrument building to the French court. Through the revival of Neoplatonic philosophy around the middle of the sixteenth century and the foundation of the Académie de poésie et de musique by Jean-Antoine de Baïf and Joachim Thibault de Courville in 1570, the viol became linked to Pythagorean and Platonic cosmology. Learning to play viol and lute became essential for the education of nobles because of the belief that these instruments held the power to elevate the soul through the emulation the ratios present in musica mundana, or harmonic resonances with planetary motion. Also in the middle of the sixteenth century, Philibert Jambe de Fer, in one of the earliest published French music treatises, affirmed that viols were played by both the aristocracy and the bourgeoisie when he claimed it was ‘an instrument played by gentlemen, merchants and other men of virtue’.Footnote 13 For the bourgeoisie – the targeted readership of the earliest published tutors – luthiers, musicians and religious reformers founded music schools to teach lute and viol under a moral philosophy aimed at limiting the idle time of urban youths through humanistic and religious curricula and structuring leisure time. In France, the viol therefore emerged as a symbol of cultural refinement to be played and enjoyed by men of virtue and as a tool to shape bourgeois leisure to reflect noble ideals of a moral and virtuous life.

Importing the Renaissance and Civilising the Court

When François I ascended to the throne, the French court and the realm had a reputation in Western Europe, but especially throughout the Italian peninsula, as being skilled at arms but uncultured. The Italians knew firsthand of the ferocity with which the French waged war. From 1494 until 1559 successive French kings raided and conquered large portions of Italy, campaigns that are known today as the Italian wars or the Habsburg–Valois wars. Italians frequently referred to the French as ‘barbarians’, a word that derived from the Greek for one who stutters but which was often hurled at indigenous peoples of the Americas who lacked written language.Footnote 14 Defending against this reputation, Joachim du Bellay titled the second chapter of his La défense et illustration de la langue Françoyse ‘That the French language should not be called barbarous’. In it he discussed the brilliance of French martial glory, which he claimed the Italians could not withstand, and defended the French language from barbarous accusations by the Italians: ‘not only have they [the Italians] done us wrong by this, but to render us still more odious, they have called us brutal, cruel and barbarous’.Footnote 15 Still, the perception of the French language as barbarous by European elites was echoed by Erasmus in 1530 when in his essay De pueris instituendis he described the ease with which

a German boy could learn French in a few months quite unconsciously while absorbed in other activities. … If one can learn with such ease a language as barbarous and irregular as French, in which spelling does not agree with pronunciation, and which has harsh sounds and accents that hardly fall within the realm of human speech.Footnote 16

Due to a combination of their martial ferocity and perceived lack of interest in letters, accusations of barbarism dogged the French in European discourse throughout the sixteenth century.

It was under this shadow of barbarism that François I made efforts to ‘civilise’ the French court and project a reputation of cultured brilliance.Footnote 17 Baldassare Castiglione, in Il libro del cortegiano, first published in 1528 but written earlier and ostensibly recounting a conversation that took place over a span of four days in the year 1507, admitted that ‘the French recognise only the nobility of arms and esteem all the rest as nothing; in a way that not only do they not esteem but they abhor letters and consider all men of letters to have little value’. Guidobaldo da Montefeltro, the Duke of Urbino, responds with a positive impression of a changing court culture:

what you say is true (he said); this error has prevailed among the French for a long time, but if good fortune will have it and Monseigneur d’Angoulême succeeds to the crown [as François I], as is hoped, then I think that just as the glory of arms flourishes and shines in France, so must that of letters flourish there also with the greatest splendour. Because when I was at that court not long ago, I saw this prince; and, besides the disposition of his body and the beauty of his face, he appeared to me to have in his majesty such greatness – yet joined with a certain gracious humanity – that the kingdom of France must always seem a petty realm to him. Then later, from many gentlemen, both French and Italian, I heard much of his noble manners, of his virtue and courage, of his valour and liberality; and I was told, among other things, how he loved and esteemed letters and how he held all men of letters in the greatest honour; and how he blamed the French themselves for being so hostile to this profession, especially as they have in their country a noble university like that of Paris.Footnote 18

According to the Duke of Urbino, François I could save France from barbarism through his love of letters. In 1529, François I created the new office of lecteur du Roi (charged with reading aloud to the king), and Jacques Colin was the first to hold this office. At the king’s behest, Colin translated Castiglione’s influential book into French in 1537, suggesting royal recognition of the usefulness of this depiction of the French king in such an influential and widely read work.Footnote 19

Through his mother Louise of Savoy, an avid lover of books and Italian art, François inherited a fascination with advances in arts and sciences in Italy.Footnote 20 He founded a royal library, charged the humanist Guillaume Budé with enlarging its collection, and employed agents in Italy to acquire rare books and manuscripts. In 1527, for one example, he provided an agent with 1,000 écus to purchase ‘livres et antiquailles’ in Rome.Footnote 21 His cultivation of humanism in France led, at the urging of Budé and Du Bellay, to the founding of the Collège des trois langues, dedicated to the study of Latin, Greek and Hebrew. He also became a patron of Italian artists, including the sculptor Juste de Juste, the painters Fiorentino, Primaticcio, Lucca Penni and Antonio Fantuzzi, the polymath Leonardo da Vinci, the furniture maker Francesco Scibec da Carpi, the goldsmith and sculptor Benvenuto Cellini, the ceramist Girolamo della Robbia and the architects Domenico da Cortona dit ‘Boccador’ and Sebastiano Serlio.Footnote 22 The Florentine painter Andrea del Sarto, who briefly visited the French court in 1518, worked as one of François’s many agents in acquiring works of art, although according to Vasari he squandered the money and never returned to France. At Fontainebleau around 1540 François also surrounded the chateau with a new Italian Renaissance garden reflecting classical ideals of beauty and order. On 28 June 1528 he married his cousin and sister-in-law Renée de France to Duke Ercole II d’Este of Ferrara at a ceremony at the Sainte-Chapelle in Paris. Five years later, on 28 October 1533, he married his son Henri (afterwards Henri II) to the Florentine Catherine de’ Medici. These marriages solidified Franco-Italian bonds, created allies for France’s Italian campaigns and insured continued northern-Italian cultural influence at the French court.

The absorption of the Italian Renaissance and support for humanism also shaped royal musical establishments. François I recruited the Milanese lutenist Giovanni Paolo Paladino, known in France as Jean-Paul Paladin, to his court in 1516. In her analysis of court records, Christelle Cazaux has shown that by the end of the 1520s François I’s Écurie (stables) consisted of two bands of jouers d’instruments: a French band consisting of violons and an Italian band consisting of saqueboutes and hautebois.Footnote 23 These ensembles, both the French violons and Italian saqueboutes and hautebois, performed at occasions of state, such as fêtes, solemn entries, banquets, balls, religious processions, and funerals.Footnote 24 The Italian musicians would have brought with them their Italian instruments, thereby shaping the sonic experience of court festivities. By 1529, the same decade in which the Italian band was active at court, the renowned Mantuan virtuoso lutenist Alberto de Ripa (Albert de Rippe) became joueur de luth du Roy.Footnote 25 Cazaux suggests that François I perhaps recruited the celebrated lutenist through Lazare de Baïf, the French ambassador to Venice and father of Jean-Antoine de Baïf.Footnote 26 (The younger Baïf would later become one of the founders of the Académie de Poésie et de Musique.)

In the 1550s, Charles de Guise, cardinal of Lorraine, accelerated the absorption of Italian artistic and musical influences in France. François de Guise, count of Aumale, married Anne d’Este (daughter of Renée de France) in 1548, thereby solidifying a political and familial alliance between the house of Guise and the duchy of Ferrara. Charles de Guise, François’s younger brother, cultivated an interest in the latest Italian fashions. When he departed Rome in 1550 after spending several years residing there, he shipped twenty-five cases of statues back to France.Footnote 27 In 1552, the cardinal de Lorraine purchased the palace of Meudon, which had been the residence of François I’s mistress Anne de Pisseleu d’Heilly, duchess of Étampes. Primaticcio designed a grotto there to house the cardinal’s antique statue collection. Under Primaticcio’s supervision in 1556–7 Italian artists including dell’Abbate, Domenico del Barbiere and Federico Zuccaro completed the work, and the grotto functioned as a private museum for the cardinal’s collection.Footnote 28 Around the same time the singer and composer Alfonso Ferrabosco the elder and his two brothers also entered the service of Charles de Guise in Lorraine.Footnote 29 Charles further had a salon installed on the first floor to house his collection of antiquities. The Guise family, soon to lead the militant and uncompromising Ligue catholique in the Wars of Religion, aligned themselves politically with an Italian faction at the French court, and patronised the Italian artists François I had lured to France. Italian fashions began to shift, to signify not only an interest in humanism and noble refinement but also a political alliance projecting a confessional identity, as increasingly violent conflicts shifted battlefields from the Italian Peninsula to France itself.

The French court likewise continued to accumulate both southern and northern Italian musicians and instruments under the influence of Henri II and Catherine de’ Medici. In 1552, the Italian lutenists and singers Fabrizio and Luigi Dentice came to the French court as part of the entourage of Ferrante Sanseverino, prince of Salerno. Sanseverino accompanied his own singing of Neapolitan songs. A few years later the Neapolitan bass singer Giulio Cesare Brancaccio joined them at the French court.Footnote 30 A disputed legend claims that between 1564 and 1574 the Cremonese luthier Andrea Amati delivered a set of violins to the queen regent of France, Catherine de’ Medici, on behalf of Charles IX, her son with Henri II. These Italian violins, each of which was painted with Charles IX’s coat of arms on the back, would have been played by a band of Italian violinists also brought to the French court.Footnote 31 Some of the Italian violinists working at the French court originated from Cremona, and in 1572 Charles IX gave Nicolas Delinet 50 lire to purchase a violin in Cremona ‘per il servizio del Re’ (for the service of the King).Footnote 32 The Queen’s violin band participated in court spectacles such as the Balet comique de la reine in 1581. Some of the music for this ballet was composed by the bass singer Girard de Beaulieu and was performed by Beaulieu and his wife, the Genoese soprano Violante Doria. Although there were no Italian musicians documented as viol players for the French court (Beaulieu accompanied himself playing what Jeanice Brooks has identified as a lirone), northern Italian influence permeated French musical establishments in the sixteenth century.Footnote 33

Viols at the French Court

Possibly the earliest mention of the viol in France comes from an Italian source. In a letter written in Rome from Cesare Borgia, the illegitimate son of Pope Alexander VI, to Ercole I d’Este, duke of Ferrara, on 3 September 1498, Cesare asked Ercole to lend him his ‘violas arcu pulsantes’ (violas played with a bow) for a diplomatic mission to France, where such instruments, he claimed, were highly regarded.Footnote 34 Under Ercole d’Este’s regime, Ferrara developed into an important center of musical experimentation and performance. Lewis Lockwood has shown that the city ‘supported the growth of a vitally important school, even a dynasty, of viol players’ owing to the presence of the renowned Della Viola family.Footnote 35 It was perhaps players from the first generation of this dynasty that Cesare brought with him on his diplomatic mission to the French court. This letter offers evidence that it could have been Cesare who first introduced viols to the French court.

Only six months before Cesare’s letter Louis XII had abruptly become king of France.Footnote 36 From 1501 to 1504 he was also king of Naples, a prize from the second of three Italian military campaigns during his reign. During this campaign, it was Cesare who occupied both Milan and Naples as condottiero (mercenary leader) for the French crown. On 17 August 1498, Cesare had announced his decision to resign the cardinalate. He then married Charlotte d’Albret, sister of John II of Navarre, and Louis XII named him duke of Valentinois. The diplomatic mission referenced in the letter was probably a trip to France to negotiate his wedding, during which time he was named condottiero. Eager to impress the French court, he spent lavishly on clothes and other finery for this trip, and part of that projection of wealth might have included requesting to borrow the famed Ferraresi viols.

The reign of François I offers the first sustained evidence of the use of viols in France. A copy of ‘L’état des officiers domestiques’ of François d’Angoulême, the future François I, lists four musicians of the chapelle as ‘violeurs’ in 1514, but in all other court documentation they are described as singers.Footnote 37 During this period viols often appear in descriptions of diplomatic events or political celebrations, such as in Cambrai in 1529 when a four-part viol consort from the household of François I performed to entertain Marguerite of Austria at a conference.Footnote 38 Similarly in Rouen in 1532, for the entrée of Éléonore d’Autriche and the Dauphin, the muse of lyric and erotic poetry or hymns, Erato, appeared holding ‘une violle et ung compas’ (a viol and a compass).Footnote 39 In 1543, François I created the musique de la chambre division of the royal household, an independent entity from the musicians in the service of the chapelle. Although dedicated viol players were not added at this time, most musicians performed on multiple instruments, and the creation of the musique de la chambre was an essential step towards Henri II adding two viol players four years later.

Although viols were known in France during François I’s reign, evidence of their broad use begins to accumulate during the reign of his son Henri II. As mentioned above, in 1547, the first year of his reign, Henri II reassigned Jean Bellac and Pierre de Champgilbert, alias Pierre d’Auxerre, two players of the violon in the Écurie, as players of violes in the musique de chambre. The following year, as part of Henri II and Catherine de’ Medici’s sumptuous entrée, the Florentine community of Lyon staged a performance of Cardinal Bibbiena’s Calandria. These expats, beaming with civic pride at the new Florentine queen of France, summoned a famed theatrical troupe from Florence. In the play, a song is performed ‘by a single voice accompanied by five lutes, a violone da gamba and a spinet’. Later another song is performed ‘to the sound of two spinets, four transverse flutes and four violoni da gamba’.Footnote 40 As early as 1548, Henri II had arranged the betrothal of his son François II to Mary, Queen of Scots. The marriage occurred at Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris on 24 April 1558. The Discours du grand et magnifique triumphe was published in Paris in May to commemorate and publicise the wedding ceremonies and festivities. A large ensemble of musicians dressed in red and yellow livery performed outside of Notre Dame. The festival book names ‘Trompettes, Clairons, Haulxbois, Flageolz, Violes, Violons, Cistres, Guiternes & autres infinis’ (trumpets, bugles, shawms, recorders, viols, violins, citterns, gitterns and infinite others) playing together melodiously.Footnote 41 Viols in sixteenth-century France are consistently associated with Italians, with political or diplomatic maneuvering, and with public ceremonial and courtly display.

Henri II died in 1559 from a wound inflicted during a jousting tournament held to celebrate the Treaty of Cateau-Cambrésis, which formally concluded the Italian Wars. In an undated letter offering condolences for his untimely death, one of the king’s former servants addresses Catherine de’ Medici, now Queen Regent of France. The retired servant claims that the king took great delight in singing the psalms, as translated by into metrical verse by Clément Marot, to the accompaniment of ‘lutes, viols, spinets and flutes’.Footnote 42 Musicians capable of performing on these instruments, of course, were all employed by the royal household and placed in the musique de Chambre. Less evidence of viols survives from the fourteen-year reign of Charles IX, possibly due to the raging Wars of Religion. During his reign, however, Léonor d’Orléans, the duke of Longueville, visited Berne, where he was entertained by ‘the viols of Lausanne’.Footnote 43

During the reign of Henri III viols continued to appear as part of diplomatic and political festivities. In 1573, the year before he would be crowned king, three viols are depicted on a tapestry commemorating a ball held by Catherine de’ Medici at the Tuileries Palace in honor of Polish envoys.Footnote 44 These envoys were visiting to present the throne of Poland to Catherine’s son Henri, duke of Anjou, the future Henry III of France. Upon the death of his brother Charles IX, Henri III abandoned the Polish throne, traveling back to France through Venice. During his stay in Venice, 17–27 July 1574, accounts of his expenses include a gift of 40 écus to ‘the German Martha and her husband, who were twice sent for to sing and play the lute and viol’.Footnote 45 Four years later the ‘viols et violons de Poitiers’ provided incidental music for a tragedy, a comedy and a farce performed by les Enfants de la ville (an umbrella association of festive societies) in the Halle neuve. The performances were attended by ‘plusieurs gentilshommes, damoiselles et autres estrangers’ (Several gentlemen, damsels and other foreigners).Footnote 46 In 1584, following the path forged by his colleagues Jean Bellac and Pierre d’Auxerre in 1547, Jean Fourcade was promoted by Henri III to serve as a ‘violiste de la Chambre’.Footnote 47

Henri IV, owing in part to his Huguenot faith, has been depicted as less of a melomaniac than his Valois predecessors and Bourbon successors.Footnote 48 Florence Gioanni, however, has discovered payment records for broken string replacements suggesting that Henri IV learned to play the lute. She has further discovered evidence of ‘a little viol without strings and a little broken’ in an inventory from the Château de Nérac.Footnote 49 Marin Mersenne, in his Harmonie universelle, recounts an anecdote that occurred sometime after 1589, when Henri IV ascended to the throne, and before 1600, when the viol player Granier died. In the household of Henri IV’s wife, Marguerite de Valois, Granier, playing the bass viol, enclosed a young page inside his instrument. The page sang the soprano part while Granier sang the tenor and played the bass line on his viol.Footnote 50 While historians have been puzzled as to how a child singer could have fit inside of the body of a bass viol, no one has observed that this probably would have been a large Renaissance viol. If replicating string lengths close to northern Italian viols of the time, this instrument would have a body length (a better indicator of size than string length) of roughly 93 cm, which using modern terminology would be classified as a violone. As Jean Rousseau reminisced in his 1687 Traité de viol:

The first viols that were played in France had five strings, were very large, and were used for accompaniment. The bridge was very low and was positioned below the sound holes. The bottom of the fingerboard almost touched the table, the strings were very thick, and they were tuned in fourths throughout.Footnote 51

Mersenne’s context makes it clear that he is discussing a six-string viol. These large types of French Renaissance viols could easily conceal a young page singing the dessus.

Jacques Mauduit, according to Mersenne, was the viol player responsible for adding the sixth string to French viols. After the death of Jean-Antoine de Baïf in 1589, Mauduit continued to offer concerts in the tradition of the Académie de Poésie et de Musique, but he began to focus increasingly on instrumental music. The Huguenot poet Agrippa d’Aubigné, a self-professed member of the Académie, claims in an undated letter sent to Odet de la Noue to have heard in Paris ‘un excellent consert de guitare, de douze violes, quatre espinettes, quatre luts, deux pandores & deux tuorbes’ (an excellent ensemble of guitar, twelve viols, four spinets, four lutes, two pandoras and two theorbos).Footnote 52 Sauval claims that Mauduit’s concerts ordinarily had between sixty to eighty people, sometimes as many as 120.Footnote 53 Mauduit spent time in Italy, and it is possible that he brought the Italian six-string viol and its tuning to France during this time.

Evidence from Henri IV’s reign also suggests that viol consorts appeared regularly with theatrical troupes, especially with the comédiens du roi (Actors of the King), a theatrical troupe that performed at the Hôtel de Bourgogne. In March 1598, two theatrical companies – one represented by Valleran Le Conte and called comédiens du roi and another led by Adrien Talmy and called the compagnie de comédiens français – signed a three-year contract ‘to perform together comedies, tragedies, tragicomedies, pastorals and other works agreed upon in this city of Paris, as well as elsewhere in this kingdom of France’. According to the terms of the contract, Le Conte provided costumes, stage properties and a chest of viols with which his viol quintet would perform entr’actes. On 22 March, Fiacre Boucher leased from the Confrères a loge des dépendances, a balcony from which the viol consort would perform.Footnote 54 In March, Valleran Le Conte, leader of the comédiens du roi, contracted to teach the fifteen-year-old Nicolas Gasteau ‘the science of acting … to learn to play the spinet, the viol, and to sing music’. The contract was dissolved five weeks later.Footnote 55 In Saint-Maxent in 1599 a company run by Adrien Talmy performed ‘plusieurs histoires, tragédies et comédies avecq Musicque et voix, violes et regales’ (several histories, tragedies and comedies with music and voices, viols and regals).Footnote 56 Back in Paris on 3 May 1606, Valleran Le Conte, in order to pay his actors, was forced to sell his chest of viols, his wardrobe of costumes and eleven painted backdrops to one of his actors.Footnote 57 On 1 December of the following year, Le Conte founded a new company with Nicolas Gasteau, Estienne de Ruffin, Hugues Gueru (later known as ‘Gaultier-Garguille’), Savinian Bony, Loys Nyssier, Jullien Doielles, Gasteau de Rachel Trépeau and an unnamed second female actress. Le Conte furnished the costumes, viols and backdrops suitable for the aforesaid performances of comedies, tragicomedies, pastorals and other plays’.Footnote 58 On 8 April 1609, Jacques Le Messier, the father of Pierre le Messier (later known as Bellerose), contracted an apprenticeship for his son with Valleran Le Conte, which included viol lessons. In addition to providing him lodging, food and clothing, Le Conte promised to teach Pierre ‘la science et industrie de représenter tous trage-comédyes, comédyes, pastoralles et autres jeux, ensemble à jouer de la violle’ (the science and industry [required] to represent all tragicomedies, comedies, pastorals and other plays, together with how to play the viol).Footnote 59 The use of viol consorts in the French theater has been an understudied aspect of the history of the viol in France, yet strong documentation survives of their persistent connection to theatrical performances.

A Marketplace for French Viols: Viol Luthiers and Bourgeois Amateurs

Although nobles commissioned ornate instruments made from exotic materials direct from luthiers, playing the viol was not confined to noble amateurs and professional musicians in courtly settings. Around the middle of the sixteenth century, a marketplace for viols emerged to cater in part to bourgeois amateur musicians. Inventories of instrument shops and luthiers reveal a stock of new and used instruments available for sale to the public. Gaspard Duiffoprugcar, the most celebrated luthier in sixteenth-century France, was recruited to build instruments for the French court. He set up his instrument shop in Lyon, however, at a time in which viol tutors, often including intabulated music such as four-part Parisian chansons, became available to amateurs who played consort music in their leisure time. Duiffoprugcar, although Bavarian by birth, was probably recruited from northern Italy, and he maintained business links with other luthiers of his extended family in Padua and Venice. Through his recruitment to France, he therefore served as an agent of the transfer of instrument-building techniques from northern Italy, and his relocation must be understood within the broader context of successive French kings collecting Italian artists and artisans.

Inventories of instrument shops from the middle of the century demonstrate that luthiers offered viols of all sizes for sale to the public – both professional musicians and bourgeois amateurs. On 23 March 1551, an inventory made after the death of Philippe de la Canessière, facteur d’instruments, lists ‘Item deux grand viollons garniz de leurs estuitz, une violle et ung petit viollon garniz de leurs archetz prisez ensemble L s.t.’ (Also two large violins furnished with their cases, a viol and a little violin furnished with their bows; valued together, 50 sous tournois).Footnote 60 On 27 November 1553, François Bonnin or Bonvin, aged 15, son of Antoine Bonnin or Bonvin, enters into an agreement to become a servant and apprentice at the shop of Denis Viger, ‘faiseur de guitares, luths, violes et autres instruments’ (maker of guitars, lutes, viols and other instruments), in the rue Saint-Victor. Viger agrees to provide Bonvin with food and a salary.Footnote 61 On 2 June 1556, in an inventory made after the death of Yves Mesnager, facteur d’instruments, lists ‘Item une bassecontre de violle de deux tailles non parfaictes prisez ensemble X l. tz.’ (Also a bass viol in two imperfect sizes; valued together, 10 L.t.).Footnote 62 These inventories and others often specify when an instrument is Italian in origin, which is always listed by city or region of manufacture. Northern Italian instruments were appraised at higher values than domestic instruments. On 1 October 1587, an inventory created after the death of Claude Denis, facteur d’instruments, includes bows, strings from Florence and Siena, a ‘bass viol from Brescia’, a ‘double bass viol from Cambrai’ and two old ‘dessus de violles’.Footnote 63 These inventories demonstrate a thriving marketplace for viols, bows and strings. The growing French viol marketplace, however, relied not only on importing instruments from Italy, but also on recruiting luthiers like Gaspard Duiffoprugcar to relocate to Lyon.

Gaspard Duiffoprugcar (Tieffenbrucker) was a member of a family of instrument builders from the village of Tieffenbruck, near Roßhaupten in Bavaria.Footnote 64 In 1810, Choren and Fayolle, in their Dictionnaire historique des musiciens, provided a biographical portrait of Duiffoprugcar’s early career in France:

DUIFFOPRUGCAR, (Gaspard), famous luthier, born in the Tyrol region of Italy towards the end of the fifteenth century. After traveling to Germany, he came to settle in Bologna in the first years of the sixteenth century. François I, King of France, having come to that city in 1515 to conclude a treaty with Pope Leo X, heard of Duiffoprugcar’s superior talents and made such advantageous offers to that artist as to convince him to come and settle in Paris that the latter accepted them. It appears that the plan of the French monarch was to have the instruments necessary for the service of his chambre and his chapel made in a manner worthy of his age and of his magnificence. It further seems that the cloudy climate of the capital did not suit this artist, as he asked for and obtained permission to retire to Lyon, where he probably ended his career. He was still there in 1520.Footnote 65

François I met Pope Leo X in Bologna in 1515. During this sojourn the French king recruited Leonardo da Vinci, who lived in France until his death in 1519. Duiffoprugcar’s birth in 1514, however, invalidates the legend of François I recruiting the luthier from Bologna in 1515 (or his being in Lyon in 1520). Branches of the Duiffoprugcar family had workshops in Venice, Padua and Bologna, so Gaspard Duiffoprugcar’s relocation to northern Italy would have been a logical choice for the young luthier seeking to establish himself while relying on family connections.Footnote 66 Ian Harwood and Giuio Ongaro postulate that Gaspar was a close relative or son of Ulrich (I), who, as I will discuss below, was a luthier who worked in both Bologna and Venice.Footnote 67 Dates conflict as to when Duiffoprugcar settled in Lyon; both 1533 and 1546 have been suggested,Footnote 68 but archival evidence survives only from 1548 when he rented a house from Maître Pierre Pelu and is referred to as an ‘Honorable homme Gaspard Duifobrocard faiseur de luth’ (Honorable man Gaspard Duifobrocard, maker of lutes).Footnote 69 Dell’Abbate completed the fresco that depicts two musicians playing large violes on the wall behind the musicians’ gallery (Figure 2) at Fontainebleau between 1552 and 1556, after Duiffoprugcar had relocated to France and probably after he had produced instruments for the French court.

Henri II issued ‘Lettres de naturalité pour Gaspard Dieffenbruger’ (Naturalisation papers for Gaspard Dieffenbruger) from Paris in January 1558 thereby making Duiffoprugcar a French subject. The ‘Lettres de naturalité’ begin:

Henri, by the grace of God, King of France, to all present and to come, health. Knowing that we received the humble supplication of our dear and well-beloved Caspar Dieffenbruger (German, maker of lutes, native of Fressin, imperial city in Germany) containing that it has been a long time since he left the place of his birth to come to live in our city of Lyon, where he is at present residing with firm and entire deliberation to live there and to end his days under our obedience and as our true and natural subject if our good pleasure is to consider as such and to receive …Footnote 70

Henri II, the second son and successor of François I, referring to him as ‘dear and well-beloved’ suggests a royal connection to the Duiffoprugcar workshop and approbation of Duiffoprugcar’s talents as a luthier.Footnote 71 The archival evidence therefore suggests that perhaps Henri II rather than François I spurred Duiffoprugcar’s relocation.

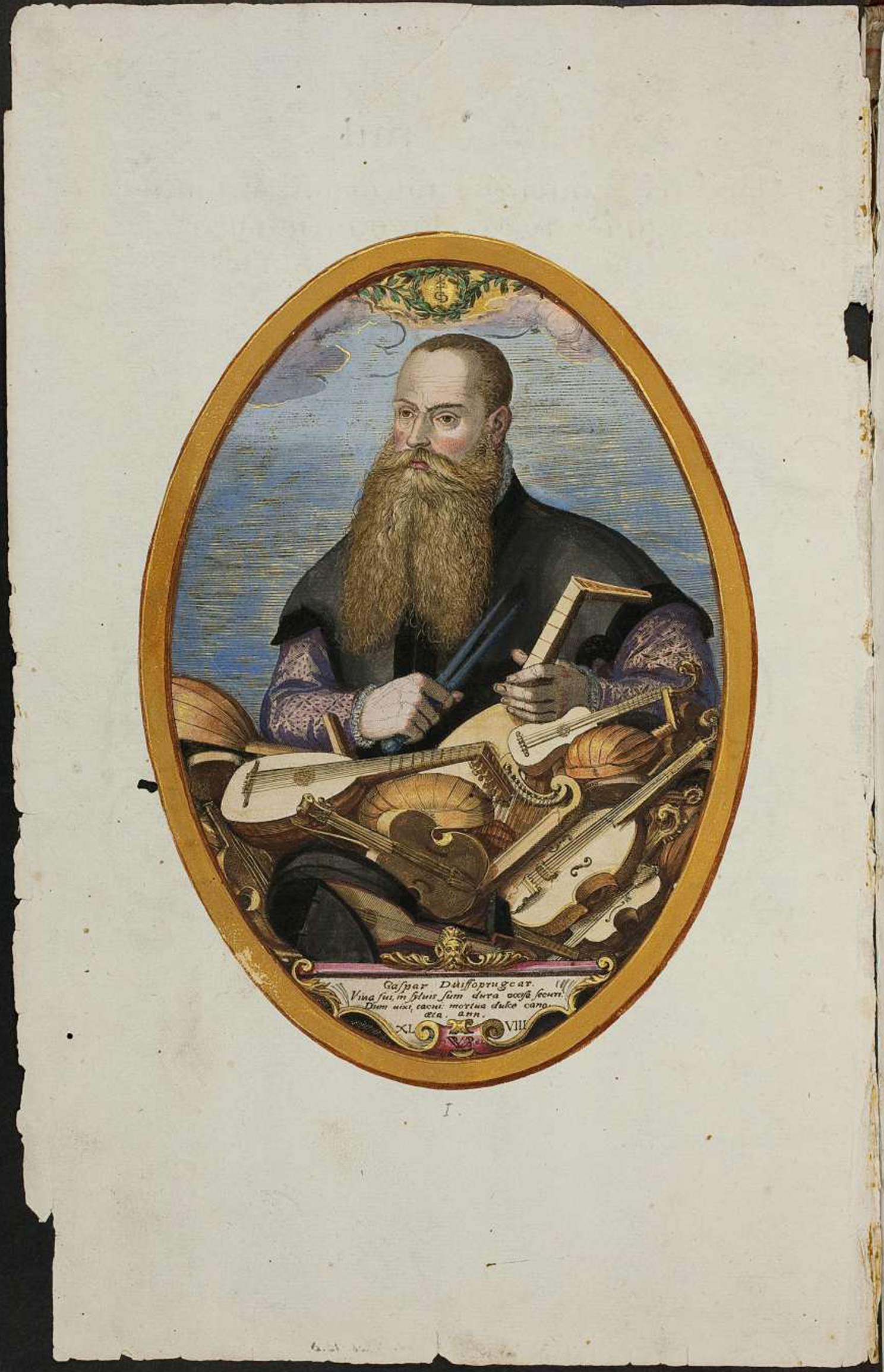

Pierre Woeiriot de Bouzey engraved a portrait of Duiffoprugcar in 1565 (Figure 3 Footnote 72 ), six years before the luthier’s death. Among the cluttered pile of string instruments depicted in his portrait is at least one five-string viol with turned-out corners – a distinctive feature of many French Renaissance viols – in the lower right of the image.Footnote 73 It is possible that Duiffoprugcar became acquainted with five-string viols before he relocated to Lyon. Both German and French sources describe five-string viols, albeit with different tuning systems. In the first edition (1529) of Martin Agricola’s treatise Musica instrumentalis deudsch, he presents fretted ‘grossen Geigen’ (large fiddles) with either five or six strings tuned in fourths with a third.Footnote 74 After multiple reprints, Agricola released an extensively revised edition of his treatise in 1545. In it he introduces the ‘grosse welsche Geigen’ (large Italian fiddles), a family of instruments with frets and four or five strings tuned in fourths with a third.Footnote 75 Hans Gerle, in his Musica teusch (German Music), first published in 1532, likewise claims that the fretted ‘grossen Geygen’ (i.e. viols), have five or six strings tuned in fourths with a third.Footnote 76 Gerle included a woodcut depicting both a five-string viol and a six-string viol.

Figure 3 Portrait of Gaspar Duiffoprugcar, engraved by Pierre Woeiriot de Bouzey. Courtesy of the Herzog August Bibliothek.

These German tutors were all marketed to bourgeois amateur musicians, and each included intabulated polyphonic music, thereby allowing beginner musicians to play ensemble music socially without a prolonged period of study to learn to read mensural notation. In 1523 or 1524, a Bavarian merchant named Jorg Weltzell, for example, intabulated music ‘auff der Geygenn’ (on fiddles).Footnote 77 Weltzell’s manuscript preserves intabulations in German lute tablature of songs and dances in four and five parts suitable for musicking with his bourgeois peers. The extended title of the first edition of Agricola’s treatise makes clear that he was providing instruction for amateur musicians ‘how to convert [music] according to properly founded tablature for … all kinds of instruments and strings’. Gerle’s complete title likewise suggests that publications in tablature were aimed at amateurs who could quickly get up to speed to play consort music: ‘Music in German, on the Instruments of Large and Small Fiddles as well as Lutes, Showing How it Should be Converted from a Song to Tablature, Following the Basis and Kind of Their Composition; Combined with a Secret Application and Art that Allows any Amateur or Beginner to Easily Achieve an Exceptional Mastery on the Said Instrument, if so Included Gradually through Daily Practice’.Footnote 78 Following his introductory treatise, Gerle includes intabulations (in German lute tablature) of German Tenorlieder and Psalm settings for consorts of four viols. He responded to changing tastes of bourgeois consumers in his 1546 publication Musica und Tabulatur, this time intabulating Parisian chansons.Footnote 79

The earliest known French tutor for the viol is Premier livre de violle contenant dix chansons avec l’introduction de l’acordes, et apliquer les doits selon la manière qu’on a acoutume de joüer, le tout de la composition de Claude Gervaise (First Book of the Viol, Containing Ten Songs with an Introduction of Tuning and Fingering According to the Way We Are Used to Playing, the Whole Composed by Claude Gervaise) from around 1547.Footnote 80 Although no known exemplar survives, we know of some of its contents because the seventeenth- and eighteenth-century composer and bibliophile Sébastien de Brossard owned a copy of the second edition. In a catalog of his extensive music library created in 1724, Brossard documented his ownership of Gervaise’s tutor, which was published by Marie Lescallopier-Attaingnant, the widow of the recently deceased Parisian music publisher Pierre Attaingnant. This ‘curious collection’ (‘recueil curieux’), to use Brossard’s term for the bound volume in his collection, began with an introduction that included instructions for tuning and fingering the viol and concluded with ten chansons first presented in French tablature and then in staff notation. Brossard’s catalog includes the following annotation for his entry for Gervaise’s Premier livre de violle: ‘All of these chansons are first presented in tablature using a, b, c, d & e for the viol, and then the subject is very well noted in music and ordinary notes. 32 folios or 64 pages’.Footnote 81 In this instance Gervaise was an innovator by publishing the first viol tablature in France and for adopting French lute tablature for his project.

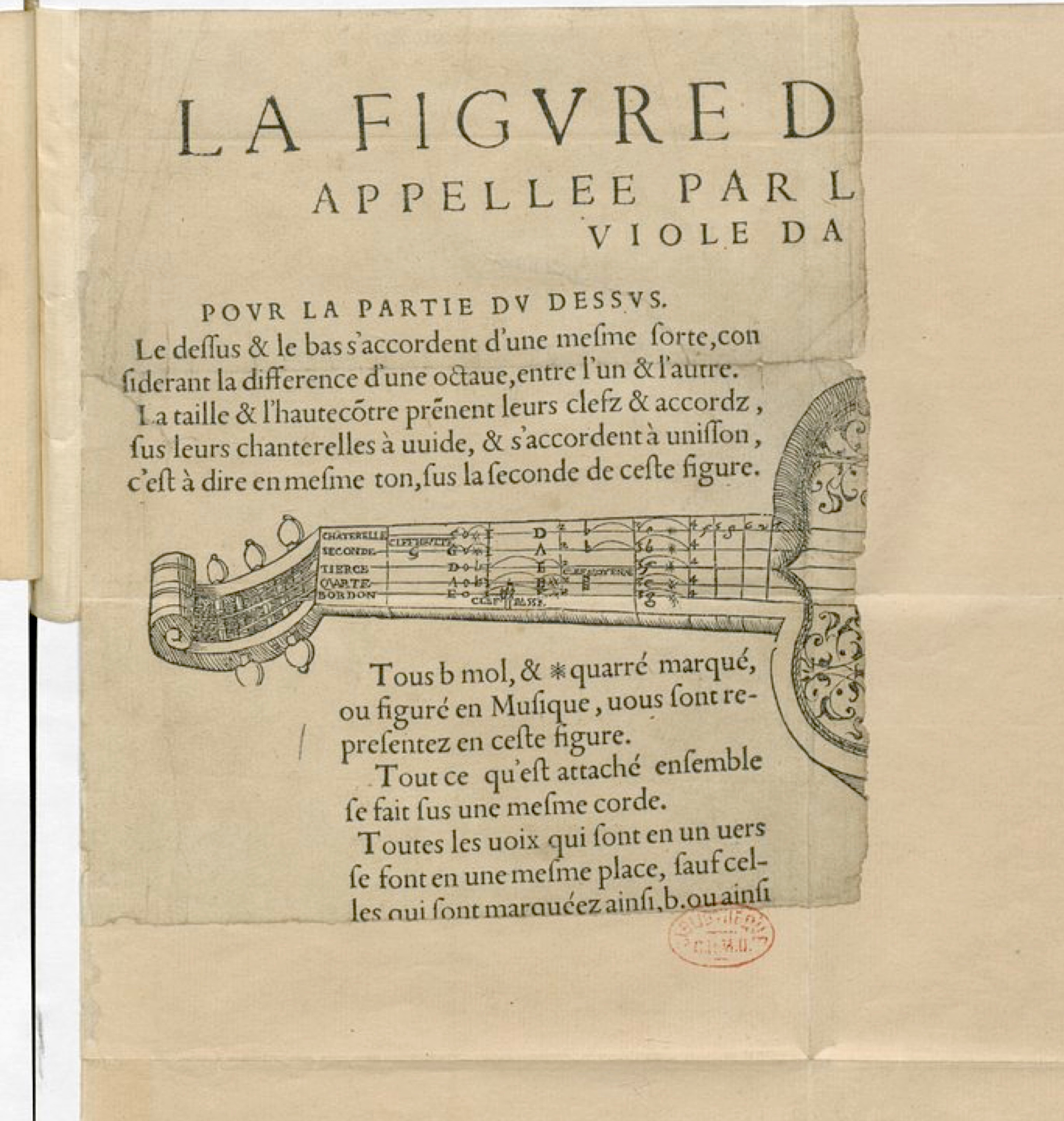

Duiffoprugcar was living in Lyon when the Lyonnais composer Philibert Jambe de Fer published his Épitome musical: Des tons, sons et accordz, es voix humaines, fleustes d’Alleman, fleustes à neuf trous, violes, & violons (Musical Epitome: On Tones, Sounds, and Tunings, for Human Voices, German [transverse] Flutes, Nine-Holed Flutes [recorders], Viols & Violins) in 1556. In the chapter about ‘violes’, he asserts that it was ‘an instrument with which gentlemen, merchants and other men of virtue pass their time’.Footnote 82 Once again the amateur status of the instrument is affirmed. Jambe de Fer dedicated his tutor to ‘the virtuous and honorable’ (‘vertueux et honorable’) Jean Darud ‘marchant es franchises de Lyon’. Darud was from a bourgeois family of spice and linen importers and a Huguenot like Jambe de Fer.Footnote 83 On two pages describing how to tune viols individually and in consorts, Jambe de Fer first provides notes on a staff and then gives fingerings (a form of tablature using numbers and lines to identify strings by name) ‘for those who do not understand musical notation’.Footnote 84 With his shop in Lyon and a renowned family name of lute and viol builders, Duiffoprugcar would have been positioned to sell five-string viols to the bourgeois ‘men of virtue’ described by Jambe de Fer. Perhaps the viol with ornate marquetry depicted in Jambe de Fer’s treatise (Figure 4) was modeled after one of the renowned luthier’s instruments.Footnote 85

Figure 4 Dessus de viole: Jambe de Fer, Épitome musical, first unpaginated fold-out at end. Courtesy of the Bibliothèque nationale de France.

The Duiffoprugcar workshop in Lyon maintained strong ties to an Italian branch of this family of luthiers and instrument wholesalers. Due in part to the propensity of family members to name their sons after themselves and in part to an incomplete historical record, the family lineage has been the topic of much debate and confusion. The elder Ulrich (I) (Odorico, Rigo) Tieffenbrucker (d. before 1560) established an Italian branch in Venice and Bologna. Ulrich (I) had three sons: Magno (I), Ulrich (II) (Odorico, Rigo) and Jacob.Footnote 86 Ulrich (II) Tieffenbrucker was described as a ‘liuter’ (luthier) in a 1567 document and had an instrument workshop in Venice called ‘all’Albero verde’ (The Green Tree). Magno (I) had a workshop named ‘all’Aquila negra’ (The Black Eagle) in Venice and produced three sons: Magno (II), Moisé and Abraam. After the death of Magno (I), his two sons Magno (II) and Moisé ran the Black Eagle workshop.

The two brothers bought Abraam out of the family business because he seems to have been as poorly suited to handling his personal finances as he was talented at attracting legal trouble. Although all three brothers were accused of Lutheran heresy by a servant in 1565, they were not subjected to any consequences at that time. Abraam, however, was again accused of Lutheran heresy by the Inquisition in 1575, and witnesses stated that he travelled regularly to ‘French lands’ carrying several hundred ducats worth of lutes. This time Abraam was accused by the family of the painter Domenico Misani of marrying and abandoning Misani’s daughter. He appears to have gone into hiding, and a Father Inquisitor charged with locating Abraam corresponded to the court of Venice in a letter about the matter:

With the most secrecy and diligence of which I am capable, and in response to the orders given to me by you in two of your most affectionate letters, I have looked and looked for Abraam the luthier but never found him. It is true, however, that nineteen or twenty days ago someone alerted me to the presence of a lute player, not a maker, who trades lutes with Lyon and transports five or six hundred scudi of them there at a time. His name is Simonetto, a small and false man, and from what I hear he does not have a good reputation with regards to his faith. It could be him, the one about whom you have written me, having changed his name. In my opinion it would be better that you not only write his name, as you already did, but his features, where he comes from, and if he has family and where, because that is how we will find information about him. If he is the one you are looking for, we can arrest him on his way back from Lyon. I write this offering from my heart and I return in order the [?] of Your Illustriousnesses. Vicenza, 6 August 1575.Footnote 87

Relying on this letter and other documentary evidence, Stefano Pio has argued that Abraam was using the false identity of Simonetto, which he appropriated from a deceased trader of lutes known as Simone of Vicenza or Simone Cerdonis. While living, Simone was both a commercial partner and a friend of the Tieffenbrucker family. In 1545 Magno (I) had purchased land near Vicenza through Simone Rossi, whose was referred to as a ‘suonatore’ (player).Footnote 88 According to Pio’s argument, then, Simonetto/Abraam was avoiding Venice by exporting lutes by land routes from Vincenza to Lyon, where he had family connections through his uncle Gaspard’s shop, by traveling through Padua. Although Gaspard Duiffoprugcar had died in Lyon in 1570/1, his son Johann (Jean) continued to operate the workshop from his father’s death until at least 1585.Footnote 89 Another of Gaspard’s sons, also named Gaspard, moved to Paris upon the death of his father, married the sister of the Parisian instrument maker Jacques Delamotte and established a workshop on the rue Pot-de-Feu. If the two branches of the family maintained a working relationship, then it is probable that the Duiffoprugcars living in France imported instruments or wholesale parts from their relatives in northern Italy and sold them in their shops.Footnote 90 A document from 1580 demonstrates that Claude Denis, the Parisian instrument builder and dealer discussed above, had ordered 200 lutes from Padua from a ‘Symon de Lus’ in Lyon.Footnote 91 ‘Symon de Lus’ was probably the same Simonetto/Abraam who made a living selling wholesale lutes from his family in northern Italy to various French instrument shops. Seven years later, at the time of his death, Claude Denis still had 35 lutes from Padua, 14 lutes from Lyon and 9 lutes from Venice in his inventory. When his son Robert died two years later, his shop’s inventory included an ‘old lute’ from ‘old Gaspartt’.Footnote 92

Pio has further discovered two Brescian documents indicating that Simonetto/Abraam, while en route from Vicenza to Lyon, stopped in Brescia to purchase bowed string instruments from Gasparo da Salò. Both documents identify Simone dal Liuto as purchaser of two violins from Gasparo da Salò in 1580, five years after the letter between the Inquisitor and the court of Venice.Footnote 93 Gasparo da Salò further lamented in 1588 that ‘my business does not go to France as usual’ (‘per non andar l’arte mia nella Franza secundo il solito’) suggesting that the death of Simone dal Liuto around 1580 interrupted this trade route of instruments between Brescia and France.Footnote 94 If it is true that Abraam Tieffenbrucker, in hiding from the Inquisition, adopted the name of his deceased lute-playing friend Simone dal Liuto, and if it is true that Abraam was the purchaser of bowed string instruments from the shop of Gasparo da Salò, then it is likely that Gaspard Duiffoprugcar (and after his death, his sons) sold Venetian lutes and Brescian bowed instruments in France. Comparing appraised values for northern Italian instruments to domestic instruments in dealer inventories suggests that northern Italian stringed instruments were prized in sixteenth-century France, especially lutes from Venice and bowed instruments from Brescia.

While many lutes attributed to the Tieffenbrucker family survive, only three viols attributed to Gaspard Duiffoprugcar have survived, and all three have been discredited as fraudulent. One of these instruments is known as the ‘Plan de Paris’ (‘Map of Paris’) viol, which is today part of the collection of the Musical Instrument Museum (MIM) in Brussels. The luthier and restorer Shem Mackey has offered convincing evidence that ‘the shape and construction details of this viol place it firmly in the second half of the 1600s and within the French/English style of making’.Footnote 95 The two other viols attributed to Duiffoprugcar also both have similar elaborate ornamentation and are likewise misattributed. The ‘Plan de Paris’ viol includes a handwritten inscription inside the back: ‘This viola da gamba, made by Duiffoprugcar in Paris in 1515, belonged to François I. From the Dictionnaire of Choron and Fayolle. 1830’ followed by the signature of the nineteenth-century French luthier Jean-Baptiste Vuillaume.Footnote 96 The inscription in pencil is difficult to read today, and Mackey relies on an exhibition catalog, in which the last part of the inscription was plainly misread. It became fashionable in the nineteenth century for French luthiers like Vuillaume to put false labels in violins reading ‘Gaspard Duiffoprugcar’; some luthiers even carved a scroll in his likeness based on the bearded engraving produced in the sixteenth century. French scholars also contributed to the construction of Duiffoprugcar’s legend: ‘a totally fantasist biography was built up, amplified, repeated, watered down’.Footnote 97 While no viols survive from Duiffoprugcar’s hand, he became a symbol of French nationalism in the nineteenth century, a tumultuous century when some in France gazed backwards to the Ancien Régime as a source of stability and patriotic pride.

An Instrument of Virtue: Viol Education to Train Bodies and Souls

Because by the early sixteenth century viols and the lutes emerged as instruments suitable for nobles to perform for their leisure, educational programs for princes included instruction on how to read mensural notation, sing, and perform on these instruments. Castiglione connects these two instruments in the Cortegiano. He advises courtiers that ‘Singing extempore polyphony … seems to me a beautiful kind of music …, but singing to the lute is even better’ because it is easier to understand the words. He then continues to note that ‘no less delectable is the music of four bowed viols, for it is very sweet and artificial’.Footnote 98 The iconographic record from the sixteenth century supports Castiglione’s claim; plucked and bowed instruments are depicted performing together at affairs of the French court.

But more than instruments signifying leisure and refinement, learning to play lutes and viols persisted as part of the education of princes and their urban emulators because of the belief that these instruments held the power to balance a soul by mirroring ratios present in musica mundana, or the harmony of the spheres.Footnote 99 By reproducing the proportions of the movements of celestial bodies through audible music (musica instrumentalis, or terrestrial music created by voices or instruments), noble musicking, according to the Neoplatonic philosophy in vogue by the middle of the sixteenth century, could mould princes to live a moral life and to rule through the equitable dispensation of justice. The relationship between audible and celestial music was also mediated through musica humana, or the internal harmony of the human body, which regulated the body–soul relationship. The proportions reflected in this threefold system could therefore shape princes into just rulers, heal the body and soul and mystically bind the earthly realm to the spiritual. Through a Pythagorean and Neoplatonic lens, music, in short, connected the incomprehensible beauty of God to human flesh by linking the carnal to the soul and the soul to the universe. By playing divinely attuned music, nobles were mirroring divine perfection.Footnote 100

The Académie de poésie et de musique, founded in 1570 by the poet Jean-Antoine de Baïf and the musician Joachim Thibault de Courville, pursued a humanistic revival of Greek and Roman poetry and music to unlock their combined power.Footnote 101 By composing French poetry using ancient poetic metres (vers mesurés à l’antique) and setting this measured poetry to measured music (musique mesurée à l’antique), Baïf and his collaborators believed they could induce a structured social order that was moral and just. The profound power of music, they argued, would serve the beleaguered French crown in creating a revitalised and more harmonious France to prop up a monarch weakened by recent outbreaks of confessional violence.

One enduring legacy of Baïf’s Académie stems from its influence on the Balet comique de la Royne, an elaborate court spectacle performed at the Hôtel de Bourbon in 1581.Footnote 102 Created under the auspices of Queen Catherine de Médicis, the ballet featured Baïfian measured music and dances tracing geometric shapes regulated to the ratios of celestial harmony. On one side of the hall stood the voûte dorée, an elongated wooden vault concealed by radiant billowing clouds gilded with stars. Inside the clouds ten concerts de musique (combinations of instrumentalists and vocalists) echoed the musique mesurée performed in the spectacle. Although the composition of these ensembles remains elusive, on the basis of court records of instruments available in royal musical establishments and iconographic depictions of suitable celestial instruments, viols could have been included. In the program, Baltasar de Beaujoyeulx, a violinist and the author of the text, describes the voûte dorée as representing the ‘true harmony of heaven by which all things that exist are preserved and maintained’.Footnote 103 The geometric figures of the dances combined with the voûte dorée echoing the musique mesurée of the singers unlocked, for the ballet’s creators and its informed spectators, music’s ability to shape moral and spiritual life at court, which reverberated throughout the realm.

The plot of the Balet comique is concerned with the establishment of the harmony and order of the soul. It unfolds through the presentation of a series of mythological characters with musical powers.Footnote 104 During the first intermède, a Triton and three Sirens – known for the alluring power of voices – enter through one of the trellised arches and perform a song in musique mesurée in praise of King Henry III. The musicians in the voûte dorée respond to each couplet with a refrain, symbolising sympathetic resonance with the heavens. The queen and her ladies-in-waiting next enter on a cart decorated as a giant fountain drawn by two sea horses and accompanied by eight of the king’s musicians dressed as Tritons, who sing in praise of the queen (Figure 5). According to the image in the printed program, the tritons self-accompanied their song with a viol, lute, harp and trumpet. While the viol and lute are instruments that signified aristocratic leisure and harmonic proportions, the harp (played by King David, the composer of the Psalms) and trumpet (played by celestial choirs of angels) represent biblical musical power. The divine power of music in both ancient Greco-Roman and Judeo-Christian traditions are thus melded in a single vignette.

Figure 5 ‘Figure des Tritons’: Beaujoyeulx, Balet comique de la Royne, fol. 16v. Courtesy of the Bibliothèque nationale de France.

Painted nearly three decades before the performance of the Balet comique de la Royne, the fresco behind the musicians’ gallery in the Salle de Bal at the Château de Fontainebleau (Figure 2 above) also depicts viols as instruments with cosmic symbolism. As analysed by Anne-Marie Lecoq and Luisa Capodieci, the doorway ruptures the space into contrasting halves with distinct groups of musicians.Footnote 105 On the left, according to Capodieci, the concert takes place in a clearing protected by an enclosure of rocks and massive trees reminiscent of Parnassus.Footnote 106 In support of this reading, multiple drawn and engraved copies of this half of the fresco bear the title ‘Concert of the Gods’.Footnote 107 Lecoq argues that the left half of the fresco should be read as a celebration of love and celestial harmony. She highlights Amor, Venus and the Graces dancing in a circle, which represents the Platonic concept of love serving as the current that animates the cosmos and binds the soul of man to God. The female and male viol players, cloaked in classical drapery, gaze tenderly into each other’s eyes while seated in a hierarchically superior position on a platform, which, argues Capodieci, mirrors the placement of the king on a raised platform at the opposite end of the ballroom.Footnote 108 In the other half of the fresco, four beautiful young ladies assemble around a musician playing a lute and a faun playing a tambourine. Lecoq argues that this half of the fresco represents worldly music as a foil to celestial harmony. This concert appears at a lower visual plane than the transmundane viol players, and the king’s musicians performing from the balcony would appear lower still to the vantage point of the spectators in the hall. My own Neoplatonic reading of the fresco would rework and expand Lecoq’s interpretation with musica mundana represented by the concert of the gods on the left, musica humana depicted in the humans and faun on the right, and, I would add, musica instrumentalis present in the sounds produced by the terrestrial musicians performing in front of the fresco. This interpretation resonates with the overarching mythological plan of the other frescos around the ballroom, which Lecoq reads as the balance between concord and discord.

Understanding that celestial harmony could forge the philosopher king into a just and equitable ruler, harnessing its power could heal a kingdom divided by confessional violence. The bowed viol, in this iconological reading, symbolised cosmic order and the power of terrestrial music to both mirror and tap into the divine beauty of the heavens. Performing terrestrial music and understanding its proportions were the mechanisms through which humans could contemplate the divine. The ballroom was therefore not merely a space for royal entertainment but also a portal between realms, with the royal musicians taking an active part in enacting elaborate ceremonies of cosmic order.

Because learning to play the viol and the lute came to signify good manners and education, artisans, merchants and anyone with aspirations to be perceived as a person of quality pursued a basic musical education. In 1546, the city of Marseille subsidised a school founded by the luthier Barthelemé de la Crous to teach the young children of the city ‘viols, lutes and other instruments’. To convince the city leaders of the value of his endeavor, De la Crous crafted a moral argument. He suggested that if the children devoted their energies to learning the science of instruments such as viols and lutes, they would not have idle time and would stay away from vice.Footnote 109 Playing music, especially on the viol and lute, was a suitable way to pass their leisure time. By January 1548, only two years after the school opened in Marseille, viol players had dethroned the local minstrels, who were forced to earn their keep by dispersing to neighboring villages.Footnote 110 Gervaise published his Premier livre de violle in Paris around 1547, and Jambe de Fer published his Épitome musical in Lyon in 1556, both of which targeted bourgeois amateurs by offering guidance on issues such as tuning, holding the instrument and fingering, and Gervais included intabulated chansons to facilitate the performance of four-part polyphony. Some with the financial means could also contract for private instruction. On 6 September 1555, Michel Dales, a Parisian musician living in the rue Charretière near the Hôtel de Coqueret in the house called the Green Trellis, entered into a contract with Pierre Nepveu, instructor at the university, living in the rue Saint-Nicolas-de-Chardonneret. For a payment of 12 livres, Dales agrees to teach Nepveu to sing from musical notation and play the viol in his home for one hour every day beginning on 7 September for a period of four months.Footnote 111 Whether through formal schooling or private lessons, the bourgeoisie had access to musical instruction for their children. The rapid acceleration of printed material targeting amateur musicians suggests that many, Catholics and Huguenots alike, availed themselves of the opportunity to emulate the nobility. That the language of Neoplatonism was legible to the bourgeoisie is demonstrated by Jambe de Fer’s dedication to his Épitome musical, in which he wishes to the merchant dedicatees, ‘God keep you both and yours in continual good friendship, concord and the consonant harmony of your virtuous affections.’

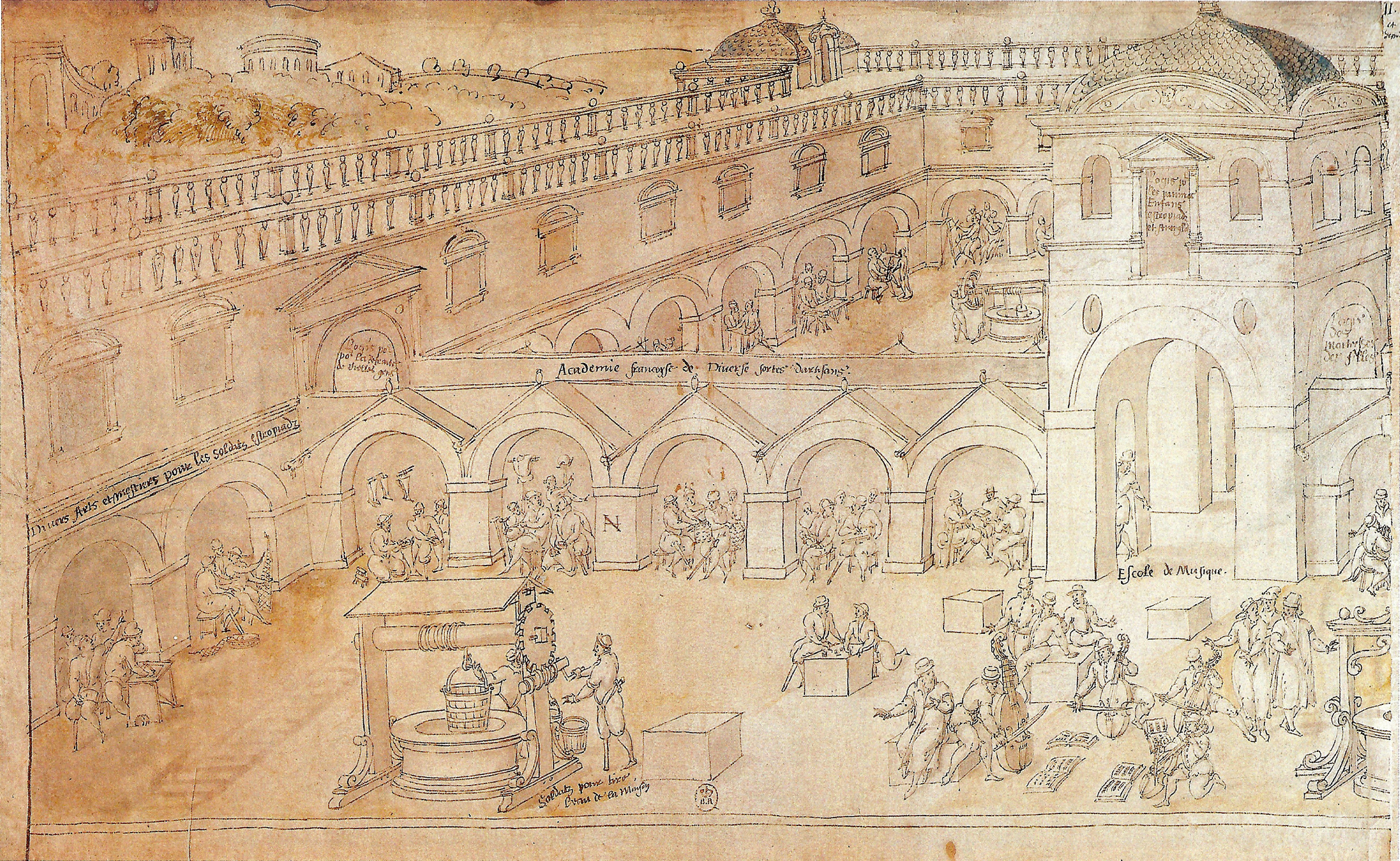

One rare example of a sixteenth-century French image portraying a consort of viols performing together – as opposed to the mixed consorts featuring one or two viols more commonly found in contemporary iconography – originates from a moral, spiritual, and pedagogical initiative. In the eleventh and last of a series of drawings depicting his Maison de la Charité chrétienne (House of Christian Charity), the Parisian apothecary Nicolas Houël exhibits a school of music (Figure 6).Footnote 112 In the right foreground four students play large five-string viols while reading from published part books like those of Parisian chansons produced by the Attaingnant firm. This image demonstrates the connection between musical recreation and morality for ‘men of virtue’.

Figure 6 School of music: Houël, ‘Procession de Louise de Lorraine’, drawing 11. Courtesy of the Bibliothèque nationale de France.

Houël envisioned his Maison de la Charité chrétienne as a charitable foundation that would provide ‘education in the profession of apothecary … for the instruction of poor orphan children and for the shameful poor, priests, schoolboys, gentleman, merchants and artisans of the city and suburbs of Paris’. The boys would be charged with maintaining a medicinal botanical garden and with dispensing the medicine they grew to the urban poor of Paris.Footnote 113 As Houël envisioned the curriculum, boys would ground their education on a humanistic foundation in languages and letters. The Maison, with financial support from the crown and wealthy bourgeois Parisians, would order social relations and provide the destitute with opportunity to learn a trade.Footnote 114 In return for royal support Houël’s institution would serve as the spiritual home for the Queen’s soul.Footnote 115

Houël was part of a growing number of Catholics who grew weary from decades of the Wars of Religion and turned to the doctrine of ‘good works’ and charity as a means to demonstrate Christian values while supporting those ‘faithful Christians’ who suffered ‘the dangerous and pernicious effects of civil wars’.Footnote 116 The Council of Trent had recently affirmed the practice of seeking salvation through charity and other good works as official Counter-Reformation church doctrine.Footnote 117 Charity was a means to counter the aggression and violence of the religious wars, and it was also seen as an effective weapon wielded against Huguenot heresy. Jean Martin, the governor of Paris’s Grand Bureau des Pauvres, made the same point in his 1580 treatise when he claimed that ‘almsgiving keeps and battles like a strong spear against our enemy’.Footnote 118 Charity was therefore central to Counter-Reformation Catholic theology and was a necessary response to the countless orphans created by decades of bloody violence.

Besides housing and educating orphans, growing medicinal botanicals and administering medicine to Paris’ poor, Houël emphasised the establishment of a chapel where divine service would be conducted for the health and prosperity of the Maison’s royal patrons. The chapel would have four chaplains who are ‘learned men and well versed in good letters’.Footnote 119 These chaplains would take some of the children to serve the chapel and learn music and plainchant, while others would study the art and science of apothecary in order to treat the sick poor in their homes.Footnote 120 Some of the children would therefore repay the financial support of the royal family by singing and praying for them in the chapel. As part of their training, they would learn to read music, which in their leisure hours could be applied to performances of music on viols, lutes and other instruments played by ‘gentlemen, merchants and other men of virtue’. The viol, like the lute, was therefore propagated from aristocratic circles to aspirational bourgeois amateurs down to well-born but impoverished orphans who were trained in a craft and provided an opportunity for a respectable future. Even if Houël’s ‘Escole de Musique’ never became a reality, the chapel was created as a crucial component of his spiritual project. Civic and religious leaders at the Maison and other charitable organisations saw performing on the viol and lute as part of moral and spiritual project to reduce idle time of youths and focus their energy on training and uplifting their bodies and souls with activities that kept them away from vice.

Conclusion

In sixteenth-century France, the viol came to symbolise a virtuous life. Early in the century, alongside artworks and artisans, viols were imported from northern Italy by French kings as part of a project to fashion a vision of the court that was both skilled in arms and refined in social mores. The French court used the viol, alongside the lute, as sonic symbols of a new humanistic lettered culture and of noble leisure and wealth. Musical institutions at the French court were therefore reworked to incorporate professional Italian musicians and viol players, and noble amateurs began to learn the instrument. Throughout the century the instrument appears featured in court and diplomatic festivities, especially when Italians were connected to celebrations. As Neoplatonic philosophy came into vogue in the middle of the sixteenth century, viols and lutes became entangled with discourse about the music of the spheres and as instruments capable of producing the proportions that bound terrestrial to celestial harmony. Playing the viol therefore contributed to the training of the minds, bodies and souls of young members of the elite.

By the middle of the century, bourgeois amateurs adapted the viol as an instrument suitable for social musicking. Gervaise published his Premier livre de violle in Paris around 1547, and Jambe de Fer published his Épitome musical in Lyon in 1556. Alongside the publication of these viol tutors, amateur and professional musicians intabulated polyphonic music to allow amateur musicians quick access to social musical exchanges without requiring lengthy study to learn to read mensural notation. Although the luthier Gaspard Duiffoprugcar was recruited to France by the king, his workshop in Lyon and his familial connections to wholesalers and instrument makers in northern Italy positioned him to take advantage of a thriving marketplace for viols. Aspirational bourgeois amateurs, Catholic and Huguenot alike, saw the viol as a suitable instrument with which to pass their leisure hours. The viol was further adopted in moral educational initiatives that sought to limit the exposure of youths to vice. In Marseille and Paris schools were founded that in part educated youths on playing viols and lutes.

The French court was effective in its efforts to shed its reputation of barbarism. Throughout the sixteenth century, the Valois monarchy refashioned itself and forged a new identity in the fire of decades of the Wars of Religion. Adopting the viol as a symbol of noble refinement played but a small part in this endeavor, and it remained a potent symbol of the Bourbon monarchy throughout the seventeenth and most of the eighteenth centuries. French viol players added a seventh string to the instrument, and indigenous traditions of viol lutherie and solo performance thrived into the eighteenth century. The viol, with its sweet and subtle timbre, proved to be an enduring symbol of cultural refinement, and aspirational bourgeois amateurs embraced it as a means of social elevation.