1. Introduction

This article investigates early modern rural economic practices. The central question is what scope for action emerges when we trace the ways money has been handled. These encompass a wide range of activities, including the transfer of family wealth, investment activities, securing assets, borrowing and lending, and saving. Our aim is to situate probate inventories in their social context and unearth the economic activities beneath the surface. Can a qualitative study of probate material reveal the economic practices in a rural setting, such as pluri-activity, multiple income sources and credit relations, which typically escape a quantitative analysis? Does this approach have the potential to fill gaps in missing information on income and past credit transactions, thereby informing aggregate analyses of credit relations that extend beyond the confines of probate inventories? These questions seek to inject some dynamism into the picture of debt and credit provided by inventories and explore the heuristic potential of credit tracing further. To achieve this, we juxtapose two different historical actors with distinct profiles in early modern southern Tyrol between the sixteenth and the late eighteenth centuries. The county of Tyrol was located within the Central European Habsburg Monarchy, and our research areas in southern Tyrol were predominantly rural yet economically active, with probate inventories surviving for both women and men from the sixteenth century onwards.

Rural economies in early modern Europe remain a research lacuna, not only in terms of consumption patterns and living standards but also with regard to pluri-activity and diverse sources of income, the property situation and its legal context, gender relations and, finally, the legal and practical scope of credit and debt.Footnote 1 This is particularly true if we assume that these aspects are closely interrelated. At the same time, it must be taken into account that the study of credit and debt relations and practices in urban and rural areas indicates institutional differences: in urban areas, a variety of institutions offered or facilitated credit, while in rural areas, land ownership seems to have played a more important role as collateral.Footnote 2 Evidence of diverse income options and consumer credit is often harder to obtain for rural residents due to less in the way of detailed documentation, such as account books. Where documentation exists, probate inventories provide valuable information about the extent of land ownership, the material equipment of houses and farms, the cash available, and claims and liabilities.Footnote 3 While these are important starting points for analysing credit and debt in rural areas, they are limited in scope as they document the situation only at one point in time. Lists of claims and liabilities debts in probate inventories have been used productively to analyse credit and debt. Elise Dermineur, for instance, used her extensive database to track peer-to-peer lending by women and men in early modern France.Footnote 4 Quantitative studies show trends at an aggregate level and highlight non-intermediated credit relations. Yet they only scratch the surface of the inventoried individuals’ comprehensive economic activities.

1.1. Tracing credit and debt among rural entrepreneurs

Historiography on sixteenth to eighteenth centuries European credit has mainly focused on the interrelationship between debt, credit and social relations, particularly with regard to the wider social environment. This has arisen from various forms of socialization through corporations, labour relations, official functions and close neighbourhoods, among others.Footnote 5 This article builds on these studies but goes further in two ways. First, it asks what becomes visible when tracing credit in terms of rights of ownership and usage rights, and the spheres of activity of women and men. Second, it explores how lenders documented outstanding debts and how unrecorded debts were identified and knowledge of them secured. This approach has a common thread: credit and debt act as a lens through which social, economic, legal and administrative contexts and interdependencies become visible. It provides new insights into pluri-activity and how individuals acted in financial matters related to credit and debt.

Another issue addressed in this article is the inclusion of debts arising from marriage and inheritance shares, which are often not considered as part of commercial debt or credit, and are therefore not analysed alongside other loans. This aspect is connected to the methodological difficulty that kinship debts are often only recorded in unrelated documents, which can lead to them being underestimated in credit research.Footnote 6 Research into women and credit is an expanding field which verifies female involvement in credit transactions related to commerce, consumption and kin. However, the available evidence seems to indicate that women were more likely to be creditors than debtors and were more inclined to borrow ‘informally’, that is, within a social context and outside the notarial or court-related environment.Footnote 7 Consequently, we should aim to trace all borrowing and lending practices and identify the specific ways in which they have been documented. Tracing credit, debt and other financial responsibilities requires a broader source basis. As references to credit and credit relationships are often scattered across different sources and not immediately visible, they must be reconstructed by interlinking and interrogating different documents.Footnote 8

In this article, we focus on two individuals and reconstruct the scope of their actions in specific situations involving credit and debt. Our aim is to test a heuristic approach, not to make a comparison. The two case studies chosen are therefore very different from each other in order to explore the potential of credit traces. The area under investigation is present-day South Tyrol in northern Italy, formerly part of the Habsburg Monarchy. Christina Neuhauserin, the first protagonist, lived in the court district of Sonnenburg/Castel Badia in the Puster Valley, in a hamlet called Fassing/Fassine above the village of Sankt Lorenzen/San Lorenzo. The second protagonist, Martin Schenk, owned the Lamb Inn in Kastelruth/Castelrotto, near Bolzano, on a mid-mountain terrace above the Eisack Valley. The widow Christina Neuhauserin was the administratrix of her husband’s large farm in a rural, peasant context at the end of the sixteenth century. She was involved in a network of marital, family and non-kin loans, as well as long-term lending practices. Christina was economically astute and understood social obligations, which enabled her to overcome the gender-specific disadvantages that women faced in accessing credit, as they were much less likely than men to own landed property to use as collateral for loans. But her own wealth may also have played an important role in encouraging her to interact with her neighbourhood as a member of the local elite.

As for Martin Schenk, who died in 1781, he was the second generation to run the Lamb Inn in the eighteenth century. Thanks to the skilful economic actions of both generations, he had achieved a certain level of prosperity compared to his local contemporaries. A characteristic of rural elites was that they acted as lenders – as Martin Schenk did. As he had a large number of debtors, determining the outstanding debts for the inventory was not simply a matter of recording them; it was a lengthy process of ascertaining them.Footnote 9 The inventory also reveals significant additional activities.

A closer look at the ways in which the two protagonists operated suggests rural entrepreneurship in both cases: they were involved in credit and debt relations, a variety of rural activities dependent on land ownership or access to land use and embedded in social and kinship relations. The concept of rural entrepreneurship refers to agricultural producers acting as merchants and traders, an approach advocated by Frank Konersmann and Klaus-Joachim Lorenzen-Schmidt, for example.Footnote 10 They aimed to demonstrate the range of activities available to agriculturalists and to modify the interpretive framework of an urban–rural divide. In this article, we build on this premise and perspective by examining a widow who ran a large farm and an innkeeper involved in trade, focusing on credit, debt and economic activities beyond subsistence. The two case studies acknowledge that rural economies required management skills, as well as pluri-activity and lending and borrowing, and were not only peasant-based but also highly diverse. They also show that women, particularly widows, were able to engage in a wide range of activities – even in a society strongly characterized by male lineage which was strengthened by the inheritance practice and the marital property regime in force.

The article first introduces the main sources used, before discussing the position of widows as interim estate managers and the property situation in early modern Tyrol, which leads into the first case study of a wealthy widow. A discussion of innkeepers as entrepreneurs precedes the second case study of an innkeeper. In the final section, we draw conclusions from the juxtaposition of these two actors from two different areas of present-day South Tyrol and different time periods. Although they belonged to two seemingly different occupational groups, both protagonists were part of the local elite. This approach allows us to explore the potential for tracing and analysing credit and debt relations of both family and commercial origin. By studying two protagonists who differ in terms of gender, marital status and specific situation – a widowed agriculturalist woman and a recently deceased innkeeper – we gain new insights into the scope of their financial options, their visible and hidden lending and borrowing practices, and the procedures for recording and ascertaining debts.

1.2. Approaching credit and debt: the sources

Historical Tyrol, on the southern border of the Habsburg Monarchy, consisted of the County of Tyrol, the Prince-Bishopric of Brixen, mainly German-speaking, and the Prince-Bishopric of Trento, whose population was largely Italian-speaking. In the German-speaking part, which we are investigating, all property matters were governed by the Tyrolean law code (Tiroler Landesordnung), which came into force in 1526. It was considerably expanded in 1532 and further amended in 1573.Footnote 11 The code remained in force until the introduction of the Josephine Code in 1787, which was intended to replace all the provincial laws of the Habsburg lands as the first de facto general civil code in Austria. By the beginning of the sixteenth century, the courts had largely replaced the notary’s office as the most important institution of civil law. Thus, for this research most of the sources related to property, debt and credit come from here. In early modern Tyrol, courts were the central authority for both civil and criminal law and administrative districts. Court districts (Gerichte) were subordinate to the sovereign, rather than the landlords, except in ecclesiastical territories such as the court district of the Benedictine abbey of Sonnenburg.Footnote 12 Although the ecclesiastical courts in German-speaking Tyrol also adhered to the Tyrolean law code, they also applied local customs that could determine specific post-mortem arrangements and debt relations.

The land registry was not introduced in Tyrol until 1900, after almost 150 years of resistance. In the early modern period, therefore, the existence of mortgages on real estate is not immediately visible.Footnote 13 The most important sources for our study of property-related issues, including credit and debt, are the court records (Verfachbücher), which are organized chronologically by court district. They contain various types of legal transaction, including contracts, probate proceedings with inventories, promissory notes and receipts, land purchase deeds and others.

Probate proceedings, in particular, are a valuable source for our contextual approach. They document the steps that had to be taken after a death and who the heirs were, and they contain the contracts (or references to them) that were concluded in this situation: such as those between the siblings, with the widowed spouse or with more distant relatives who took over the property. At the heart of this multi-stage process is the probate inventory. In Tyrol and other areas of central Europe, probate inventories usually also list current claims and liabilities and allow conclusions to be drawn about their origin, such as trade, market participation, consumption or debts owed to relatives. This enables us to look at family debt in conjunction with commercial and consumer debt, as well as their respective sources. This can significantly enhance our understanding of debt and social relations.Footnote 14 Simultaneously, insights into socio-credit relations can provide further information on the use and distribution of credit and debt between women and men, similar to what has been shown for northern Italy, for example.Footnote 15

Crucially for our approach, probate inventories contain references to other documents, such as marriage contracts, wills, purchase or leasehold contracts, earlier inheritance contracts and obligations, which are usually also copied into court records. This makes them an ideal starting point for identifying documents relating to a house, a couple, a widow or a widower. Each of these documents provides new information that can be used to trace complex transactions by reconstructing interactions and financial transactions. In the case of Christina Neuhauserin, the search for such documents is supported by a database containing all the records of the sixteenth-century court district of Sonnenburg. Thus, the analysis of the probate inventory itself could be complemented by a chain of documents from throughout the wealthy widow’s life, showing her prudent and successful management of her first husband’s estate, which she had held in usufruct over many years, how she administered her husband’s debts and how she invested and increased her own assets. The interlinking of the nucleus of the probate inventory also reveals, however, that not all contracts and deeds were copied into the court books, leaving substantial gaps in our understanding. This, in turn, illustrates the various recording practices in different time periods and areas and, of course, the fact that any copying into the court records meant additional expense.

The starting point for the case study of the innkeeper from the court district of Kastelruth is the probate proceedings with the inventory, which is an extremely voluminous bundle of recorded actions, processes and documents bound in the court book. They provide ample information about Martin Schenk’s business and family financial dealings at the time of his death. At the same time, they shed light on the process of inventorying and determining liabilities and outstanding debts, which was not documented for less wealthy and less respected individuals. These documents were drawn up over the course of several weeks after his death in 1781. On the one hand, the detailed material makes it possible to search for traces of the practice of recording debts, which refers to documents that appear in the court records, but also to media of different materiality that have not been preserved in the archive. On the other hand, Martin Schenk’s position as an active lender provides insights into the process of gathering information about debts within the context of the extended probate proceedings. This is because the list of outstanding debts cannot be included in the inventory in a single step, not only because the list is very long but also because some debtors must first be identified. The negotiations and documents relating to both cases reveal the specific use of funds and the nature and use of credit and debt relations, shedding light on the scope of the households’ financial activities.

2. Widows as interim estate administrators

In 2003, Susanne Rouette drew attention to the frequent position of widows in rural areas of German territories in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, who often acted as transitional administrators of their late husbands’ estates, and with this highlighted an important conceptual aspect.Footnote 16 The wealth of research on widowhood and property contracts by Beatrice Moring and others is testament to a burgeoning body of scholarship that emphasizes how widows often continued to manage their late husbands’ estates, either to preserve them for their underage children until they could take succession or to secure their own sustenance through usufruct.Footnote 17 Depending on the prevailing marital property regime, widows in Central Europe received either all or part of their late husband’s property in addition to their own claim, or the entire property in usufruct.Footnote 18 In all cases, the widow assumed responsibility not only for the landed property and its upkeep but also for the liabilities secured on the property. The rules of marital property determined who had incurred these debts and who was responsible for them: the couple or the spouses who borrowed. But the administration of debts formed part of the usufruct agreement.Footnote 19 As the interplay between inheritance practice, marital property regimes, usufruct and tenancy is crucial to understanding the widows’ room for manoeuvre and its limitations, the case study is preceded by a section on the legal context.

2.1. Property and wealth in early modern Tyrol

The Tyrolean law code of 1532 and 1573 did not specify the succession of property. This resulted in regions with variable partible and impartible inheritance practices. In the eastern part of German-speaking Tyrol, where Sonnenburg is located, inheritance practice was characterized by undivided succession. Depending on the manorial context and the composition of the family, the eldest son – if he had not already established himself elsewhere – or the youngest, and also daughters, were usually appointed as the main heirs. Depending on the time period and the economic situation, the so-called ceding siblings received a proportionate share in cash, credit or kind.Footnote 20

Unlike inheritance regulations, the Tyrolean law code clearly defined the marital property regime, stipulating the separation of marital property.Footnote 21 This meant that husbands were able to administer and use their wives’ marriage portion and other contributions during the marriage. However, on the death of either spouse, the assets were divided again. Unlike in other Habsburg territories, there were no provisions for widowhood (Leibgedinge). The records show, however, that retirement arrangements were common: widows received a right of residence and maintenance in the house and left their marriage portion invested in the house or farm. If there were minor children, or if the husband had left a will, the widow could receive her husband’s property in usufruct. This meant that she received the right of use, but not property, and was expected to manage it to the best of her ability and use the yields, but she could not make any changes to the property. Such a usufruct arrangement could last until a son or daughter, or all the children, reached the age of majority. Alternatively, it could be declared for life and then reverted to the children. If there were no children, it would be reverted to the late husband’s next of kin.Footnote 22 Another option was for a widow to remain as the housekeeper until the children reached majority. In some Tyrolean court districts in the sixteenth century, there are occasional records of widows leaving their late husbands’ houses once they had been reimbursed for their marriage portion and other claims. This is reminiscent of the situation in the Italian territories, where the dowry system was strictly regulated by law.Footnote 23 But by the eighteenth century, retirement arrangements had become more common. The outcome of the probate negotiations often depended on negotiations between the children’s guardians and the widow, and on the size of her property, which was mortgaged to the deceased husband’s estate. A widow with a sizeable marriage and inheritance portion thus had much more room for manoeuvre in the probate negotiations.

If a widow accepted the right of usufruct, as Christina Neuhauserin did, she became the administratrix of the property and could enjoy the proceeds but was also expected to reinvest a sufficient amount to maintain and farm the land and buildings. This entailed certain obligations regarding the property: she had to take charge of her late husband’s debts secured on the landed property and either repay them or pay interest on them using the proceeds of the property. If she used her own funds to repay the debt, she was technically granting credit and would have to be reimbursed by his family of origin. But since she did not possess the land, she could not use it as collateral in her own name.Footnote 24

The consequence of the separation of marital property was that economic inequality before marriage was not redressed by marriage – unlike with community of marital property, as was the case in rural Lower Austria. This resulted in a clear gender disparity in land ownership, which meant that women had less access to collateral and often found themselves in a potentially precarious situation, especially widows with few assets. One advantage of this system was that women could not be held liable for their husbands’ debts unless they had signed a document to that effect. Unlike the Italian dowry system, the provision of a marriage portion did not result in exclusion from further paternal and maternal inheritance. Tyrol can therefore be seen as a transitional area between German-Austrian and Italian legal cultures – particularly regarding the relatively widespread use of writing from the late Middle Ages, which has resulted in a rich body of records in Tyrolean archives.Footnote 25

Separation of marital property also meant that assets brought in by the non-propertied spouse were mortgaged against the real estate of the propertied spouse. In the majority of cases, it was the husband who was propertied, as fewer women than men possessed land.Footnote 26 Legally, wives or husbands who married into property were guaranteed the security of their marriage portion and assets, such as inheritance portions, but this had to be documented.Footnote 27 At the end of a marriage – due to the death of one of the spouses or the separation of bed and board – the respective assets fell apart again and had to be separated from the husband’s joint administration. If there were children, they inherited their parents’ assets; if they were minors, their access to their portions was delayed and administered by their guardians.Footnote 28

In all cases, the widow’s mortgaged assets took precedence over those of other creditors in order to secure her and her kin’s claims. Both sides, the spouse’s kin and the children’s guardians, had an interest in the precise separation of assets and control of their claims. Marital property was therefore characterized by credit relationships between spouses and kin, and the negotiations for widowhood contracts depended on the financial feasibility of refunding the mortgaged marriage portion and on the negotiating power of the kin members involved. Thus, widows could find themselves in a situation where they were obliged to administer their late husbands’ debts while simultaneously being the main creditors of that property, with their funds mortgaged against it – they were both acting debtors and investors. Numerous such arrangements can be found in the court records.Footnote 29 But we know little about how widows fared as administrators of usufruct. This is therefore a key aspect of our first case study.

2.2. Christina Neuhauserin – an agricultural entrepreneur

The first case study focuses on the consequences of a husband’s death for widows. It concerns the widow of a wealthy peasant from the court district of Sonnenburg in the late sixteenth century, a member of the social elite, and reconstructs her case within its distinct social and economic environment. After the death of Christina Neuhauserin’s husband, his assets were negotiated and existing credit relations were established. Subsequently, she managed his rural holdings and her own assets for approximately 32 years, until her death.

The court district of Sonnenburg was predominantly agricultural, with some rural craftsmen, court officials, millers and innkeepers. Women’s economic and labour participation in agriculture is still under-researched, but research on widows and their administration of their husbands’ estates offers an avenue into their contribution. An analysis of widowhood contracts in the court district of Sonnenburg in the Puster Valley shows that, in the sixteenth century, 11 out of 67 contracts, or more than 16 per cent, granted widows the usufruct, lease or possession of their late husbands’ estates.Footnote 30 Yet the contracts do not indicate whether the women accepted these provisions, how successfully or for how long they administered the estates, or how independent they were in their administration. The course of usufruct claims can only be reconstructed in conjunction with other records.

Can the in-depth analysis of Christina Neuhauserin’s case, based on court records and her probate inventory, reveal a broad range of economic activities and credit relations? Can it illustrate how a widow was able to utilize her claims, invest prudently in her late husband’s agricultural business and even increase her own assets?Footnote 31 Christina was married to Georg Wieland, called Mair, who possessed one part of the Mair Hof (farmstead) in Fassing/Fassine, a substantial property, probably worth more than 2,400 gulden (fl).Footnote 32 This was significantly higher than the median value of a farmstead in this court district, which was around 562 fl.Footnote 33 The German term Hof (farmstead) had a particular meaning and included a coherent group of buildings and land, as well as access to commons, high meadows and shares in the use of the forest.Footnote 34 In Fassing, Höfe (farmsteads) were located at an altitude of 900 metres, not far from the village and the abbey of Sonnenburg. Georg Wieland’s Mair Hof was one of three Höfe in Fassing that were under the lordship of the abbey of Sonnenburg.Footnote 35 The farms in this area were engaged in mixed agriculture, with grain cultivation and animal husbandry. Early modern Tyrol was a grain-importing area, so grain crops were important for both subsistence and the local grain trade.Footnote 36

Georg Mair died before 7 February 1560, according to an entry in Christina’s probate inventory of his estate.Footnote 37 He had drafted a will for his wife in which he bequeathed her all his property as a lifelong usufruct against the administration of all his debts and claims. She accepted the usufruct shortly afterwards, according to a usufruct contract of 15 April 1560.Footnote 38 Their marriage remained childless, and the appointment of the widow as the holder of the estate’s usufruct was unusual – not only because they had no children but also because she must have been relatively young at the time (she died in 1592) – thus significantly delaying the inheritance of his next of kin.Footnote 39 Unfortunately, his will was not copied into the court records, but a court hearing with her late husband’s relatives mentions some of the conditions of his bequest: his widow should receive the usufruct of his estate (calculated after deducting debts) against the payment of debts and other legacies; after her death, all her expenses should be returned to her heirs, and the estate was to go to his brother Sebastian’s daughter Ursula or her descendants.Footnote 40 Where such delays were expected, the next of kin usually tried to intervene, but – as will be shown – in this case they must have chosen to cooperate. One possible reason for this is that the estate could not finance a refund of the widow’s assets, and thus the continued administration of the Hof by the widow was the most economical solution. Another possibility is that the will offered a guarantee for the relatives by determining the exact succession in case of the widow’s death.

In 1567, Christina Neuhauserin remarried.Footnote 41 Hans Stocker, her second husband, was an ‘einfahrender Geselle’ (paraphrased as a journeyman marrying into property), an unpropertied man who nonetheless brought a significant marriage portion and assets of over 1,000 fl.Footnote 42 He may have been a ceding heir, bringing in his inheritance share. Documents show that Christina oversaw the usufruct during her second marriage. In 1571, she negotiated the payment of a 200 fl inheritance claim to one of her first husband’s female heirs, which had been secured on the property. This shows that she administered his outgoing debts.Footnote 43 She also collected debts. In 1574, for example, Christina called in a loan she had advanced to her first husband’s relatives as part of the restitution of a fief that was incorporated into the Mair Hof. Although her second husband acted as her advisor alongside her legal gender guardian, she must also have acted in the interest of her first husband’s kin by securing the fief as part of the property. Later documents show that she left the administration of the fief to his relatives, who were vassals of the fief.Footnote 44

Christina’s second husband died on 7 October 1587. Their marriage also remained childless.Footnote 45 The ensuing inheritance proceedings had to unravel a complicated property situation: Stocker had married into property that was held as usufruct by his wife.Footnote 46 Both had assets of their own, and the challenge lay in separating the various properties from the usufruct so that the deceased’s next of kin could claim their inheritance as principal heirs and the widow could claim her usufruct and widow’s rights. The proceedings show that Stocker had administrated his wife’s assets: for example, he had collected her paternal inheritance portion of 450 fl, which was now secured on his property. For the widow, the situation was extremely delicate, as she had to reclaim all her own assets from her second husband’s estate and face his relatives and their demands. She appeared with a very strong group of advisors, including her gender guardian and an advisor who were both office holders of a local elite family called Goldwurm, along with her brother Peter Neuhauser and another guardian. She presented her first husband’s will, their marriage contract and the inventory drawn up after his death, in order to prove her right to usufruct and defend her own assets, which were partly mortgaged on her second husband’s estate, against his heirs, consisting of his brothers and sisters, as well as the nieces and nephews of his deceased siblings.Footnote 47 Legal documents ascertaining possession and claims were significant and were carefully kept by their holders.

The proceedings reveal further social and credit relations. During both marriages, the couple brought up foster sons: Hans Stocker raised a cousin who was also his ward and made him a donation of 300 fl, which was still secured on this property. Georg Mair raised Lorenz and bequeathed him 50 fl, which were also pledged. Lorenz remained on the Hof after Georg Mair’s death and worked as a servant for Stocker. Lorenz also entrusted Stocker with his saved wages of 15 fl for safekeeping. During the proceedings, both foster sons claimed payment of their deposits plus interest. Stocker had kept the bonds on his property, along with the deposits, wages, savings and interest payments from them. This probably ensured his continued control in familial and work relationships.Footnote 48

The contentious negotiations continued, but consensus was eventually reached to preserve ‘peace and friendship’.Footnote 49 Christina’s claim was confirmed: an inventory of Hans Stocker’s assets was drawn up and, on the other side, Christina presented the inventory of her first husband plus accounts of all her debt repayments and expenses to prove that these were not part of Hans Stocker’s property.Footnote 50 The two inventories were then balanced. Stocker’s inventoried possessions were withdrawn, and all movables that were missing or used up according to Mair’s inventory were replaced by Stocker’s heirs. Christina was entitled to all of her first husband’s movables ‘on profit and loss’: she could keep any surplus but had to replace any losses.Footnote 51 She remained the beneficiary of the now disentangled usufruct. All of her own assets and her widow’s claims, amounting to 2,300 fl, were released from the administration of her late husband’s estate and reimbursed: 400 fl in cash and 1,900 fl in bonds.Footnote 52 We know that 450 fl of this sum was an inheritance portion from her parents, but we do not know how much of the remainder came from her marriage portion. This was probably close to the remaining sum of 1,850 fl, making her marriage portion exceptionally large for the time and place.Footnote 53 Christina’s assets were mostly invested in interest-bearing bonds, both within and outside the court district. The amount suggests that, at the time of her first husband’s death, a refund of her assets was almost impossible, and that usufruct was the only solution, as it almost equalled the value of the estate. With such a large sum secured against the Hof, Christina was effectively the main creditor of her first husband’s estate and gained a very strong bargaining position. Stocker’s heirs shared his estate and the principal heir also took over the administration of all his debts, especially the widow’s claims. Christina kept the usufruct in firm hands and successfully fought for the restitution of all her claims.

Christina Neuhauserin remained widowed. In 1592, she drew up her will with the help of Wilhelm Goldwurm, a court clerk in Sankt Lorenzen and the same gender guardian she had used in 1587.Footnote 54 In her will she stated that she was old and weak and that she had considerable paternal, maternal and acquired assets. For the salvation of her soul, she left a bequest of 100 fl to the poor and a bestowment of 100 fl to the parish church of Sankt Lorenzen for her and her ancestors’ requiems (for stipends and bread for the poor). Religious bequests were rare at this time and in this place, and her relatively large legates were exceptional.Footnote 55 For the siblings and children of a late maternal nephew of hers, Gregor Raucher, she set aside 700 fl in case they were unable to prove their relationship to her mother and claim maternal inheritance.Footnote 56 In doing so, she showed responsibility for her relatives. Similarly, she bequeathed 20 fl to her sister’s son Niclas and 20 fl to Martin, her first husband’s cousin’s son, who was in her care at the time. She also made a special bequest to Lorenz Mair, now called Tagwerker (day labourer), the same who had previously received a bequest from her first husband, which he claimed after her second husband’s death. She left him an annuity in cash and grain worth at least 24 fl. This can be viewed as a settlement of an outstanding debt, as she noted that he had never received any wages from her.Footnote 57 She bequeathed 100 fl to her gender guardian, Wilhelm Goldwurm, and a cupboard to his wife. As he owed her 100 fl, this was tantamount to forgiving his debt. She stressed that, as her long-standing advisor, he had never received any compensation. Similarly, she forgave her other gender guardian, Georg Oberhamer, 15 fl and the outstanding interest on his debt of 50 fl. Both debts dated back to 1587, and by law a gender guardian could not receive any compensation for his advice. By cancelling or reducing the debt-relationship after her death, she expressed her gratitude.Footnote 58 Finally, she left 10 fl to her maidservant. Christina’s extensive list of legates is reminiscent of urban testamentary practice. But even in nearby Brixen/Bressanone, for example, there were few comparably elaborate wills from widows at the time.Footnote 59

Overall, her bequests amounted to an astonishing 1,089 fl. She appealed to the court to respect her last will and, if the bequest should exceed half of her acquired goods, to take the remainder from her parental estate. The background to this was that the law only allowed a person to bequeath up to half of all acquired goods and a third of their inherited goods.Footnote 60 She built in a security by ensuring that if the bequests exceeded the limit of one-half, there was still the one-third of her parental estate to draw on. Together with her gender guardian, she knew exactly how to use her legal leeway. She also guaranteed the execution of her will by asking two of her second husband’s relatives to act as witnesses. Her will resembles an account of her social debts: using bequests, she settled debts with her relatives, for whom she wanted to secure part of the maternal inheritance and for services received that had never been rewarded. These social debts were the basis of long-term relationships that would only end with her death, after which they could be financially compensated for and released from their mutual legal and economic obligations.Footnote 61

Christina died a few months later, on 12 May 1592. During the ensuing legal proceedings, all those with a claim to her estate appeared in court: including all her legates, her maternal and paternal collateral heirs and the heirs of her first husband, who had a claim to the estate she held in usufruct.Footnote 62 The task was to disentangle her assets from those of her first husband’s estate. This procedure reveals how Christina had administered the usufruct: she had leased the Hof to Georg Wieland, a relative of her first husband and a prospective heir himself. The leasehold contract and inventory are listed in her probate inventory, but no date is given. We can assume that the lease was agreed shortly after the death of her second husband in 1587.Footnote 63 After Christina’s death, Georg Wieland returned the lease, including an outstanding sum of 68 fl. This sum was used to compensate for wear and tear of the estate during usufruct. The estate was divided between two groups of heirs, among them Georg Wieland. Christina had made a clever move: by leasing the Hof to one of its future successors, she not only solved the problem of labour supply but also guaranteed that it would be managed responsibly in view of his future property. The fact that only 68 fl were paid for wear and tear of the Hof after over 25 years of the widow’s administration of the usufruct shows that this solution was successful.

During the proceedings, the court instructed that the probate inventory of her goods be drawn up.Footnote 64 Apart from a large amount of movables worth 720 fl, she had about 430 fl in cash, 35 fl in silver and jewellery, and bonds amounting to 2,310 fl, most of which paid 6 per cent interest – slightly above the customary 5 per cent.Footnote 65 Her total wealth was therefore more than 3,030 fl. She had also kept a personal archive of all her important documents evidencing her entitlements, including her marriage contract, will, inheritance contracts and transfers of obligations. She knew this archive would serve her well in the event of a legal dispute.Footnote 66

However, her inventory did not list any liabilities. There could have been several reasons for this: she did not own the land but held it in usufruct. Therefore, she could not use it as collateral to take out mortgages. It is possible that Christina Neuhauserin used the land in usufruct directly as collateral for investments in the Hof. These would appear not in her inventory but in the accounts of the estate which have not survived. As administrator, Christina had to act as an intermediary: she decided on the necessary investments, probably together with her leaseholder, Wieland. He also represented her first husband’s kin, who oversaw her administration through him, as was customary with usufruct.Footnote 67 Christina’s inventory also did not list any outstanding consumption debts or wages. She may have settled these in cash – which seems plausible given her remaining cash of 430 fl – or she may have kept a separate register for them. Smaller debts may have been recorded in a daybook, but these rarely survive. Another reason for this could be the way probate inventories were recorded: the listing was often amended during and after the probate proceedings.Footnote 68

However, the absence of debts in her inventory is consistent with those of other married or widowed women without landed property. In theory, women could incur consumption debts or borrow smaller amounts, but the documentation of such debts is conspicuously absent in probate inventories of other married or widowed women without landed property between 1590 and 1612.Footnote 69 Although married women retained property rights over their assets, these were administered by their husbands. Household expenses were technically also administered by the husband, although wives could incur small consumption debts in their husbands’ name.Footnote 70 Consequently, the only debts listed were those relating to funeral and probate expenses, and occasionally to medical care towards the end of a person’s life. This contrasts with the probate inventories of landowning women, which list both secured and unsecured debts.Footnote 71

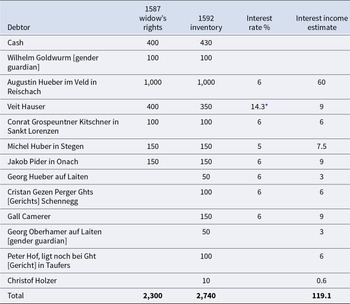

Yet, Christina had many claims. The fact that she held financial assets was not unusual for an early modern woman in Tyrol. Because few women were landowners, the wealth they held was mostly in the form of financial assets stemming from marriage portions and inheritances. Consequently, they frequently appear as creditors lending their financial assets against interest.Footnote 72 However, the amount of over 2,300 fl in debt owed to her and the 6 per cent interest rate is unusual. How could she hold such a substantial fortune in bonds without drawing on them? There are four possible sources of income: the careful management of initial funds, such as marriage portions and inheritances; prudent lending practices to trustworthy creditors at interest, which could have yielded around 119 fl per year, as shown in Table 1; revenues from agriculture, including trade in grain, cattle and dairy, and rent from the leasehold, which varied in this area between 18 and 40 fl per annum, plus shares in crop yields for comparable Höfe without maintenance contracts; and possibly textile production and trade. Having multiple sources of income, or pluri-activities, was a common feature of early modern households, and in this case it indicates the widow’s resourcefulness.Footnote 73

Table 1. Christina Neuhauserin’s claims in cash and bonds in gulden (fl) from her 1587 widowhood settlement and her 1592 probate inventory

Sources: Südtiroler Landesarchiv , Verfachbücher Sonnenburg 1587, 17 December 1587, no fol., no title; SLA VB Sonnenburg vol. 10 1590–1612, no date [inheritance proceedings 10 June 1592], no fol.

* This could also be the outstanding interest rate on the original capital of 800 fl of which 350 fl remained.

Her initial capital and lending practice indicate a sound economic base, and we believe that, through the interplay of all these sources of income, and especially the trade in grain and animal products, she was able to maintain and increase her capital.

The table shows that Christina was able to make considerable gains of more than 440 fl over time. She reinvested the 400 fl she received in cash in 1587 and had as much as 430 fl in cash at the time of her death. She never had to eat into her bonds and enjoyed above-average interest income. Christina maintained the same credit relations – within the parish district of Sankt Lorenzen and also across different court districts – and expanded her credit network over time. Her assets made her one of the wealthier widows in our sample, where the median wealth of deceased widows was 96.5 fl and the mean was 451 fl.Footnote 74 Her account is unusual for her time and area: although women could profit from interest payments, they could not make larger investments without land as collateral. Although this was also true of landless men, women lacked the same income opportunities. Even with their entitlements, widows were rarely able to increase their wealth – if they could survive on their assets or income at all, as occupational and income options for women were smaller. Social and wealth differences were decisive for widows’ living standards. In Christina’s case, we can see how her wealth enabled her to overcome gender-specific restrictions on the separation of marital property, allowing her to negotiate the best possible outcome: she was probably able to demand higher interest rates thanks to her strong bargaining position, which was based on her substantial wealth and her relative financial independence due to her usufruct entitlement.

Proceeds from the agricultural business, including rental income from the leasehold, may have contributed to her wealth. As the probate inventory provides no information on the source of these proceeds or the proportion of her assets that relied on the Hof’s yields, it is unclear how significant this contribution was. The inventory does not contain a list of grain or other agricultural produce, which would have been listed in the inventory of the Hof. The inventory does list a leasehold contract and a leasehold inventory, but the contents and terms, including the annual rent due, remain unknown. Only Christina’s personal assets and her own household goods were listed. Therefore, we can only speculate about the contribution of the Hof’s yields to her wealth.Footnote 75 Any debts secured on the land would not appear in her inventory, so we do not know whether and how many investments she made, how many servants she owed outstanding wages, or whether she and Georg Wieland, the leaseholder, traded with their agricultural produce. Thus, it is impossible to reconstruct her financial involvement in the running of the farm from the surviving records. While we can tentatively assume, on the basis of her financial dealings, that she was proficient in numeracy and literacy, no account book of hers survives.Footnote 76 But judging by the small sum allocated for wear and tear, and the amount of cash she owned, Christina, as the administratrix of the farm, must have been heavily involved in its financial and agricultural operation. It was clearly a profitable agricultural business.

Her inventory contains evidence of an additional source of income: textile production and trade. It lists 386.5 ells (about 309 linear metres) of cloth, mostly linen.Footnote 77 This is a substantial amount of cloth and much more than was needed for domestic consumption. Christina also owned 25.5 lb of yarn, 60 lb of flax and 11 lb of werg (oakum).Footnote 78 However, there is no mention of wool or woollen cloth in her inventory.Footnote 79 The question is where this amount of cloth came from. She had only one spinning wheel, so she may have spun some of her own flax. She also had four flax heckles and could have grown her own flax on plots of usufruct land.Footnote 80 But in order to obtain so much fabric, she must either have employed others to spin and weave for her, or have bought some of the cloth, maybe to trade in textiles. Unfortunately, this cannot be verified as no outstanding wages are recorded in her inventory.

2.3. Visible credit and hidden debts

Starting from Christina Neuhauserin’s probate inventory, which references other documents, it was possible to reconstruct her case by cross-linking it to these documents. This allowed us to uncover the scope of her financial activities and her role as a creditor, through which she was able to generate enough income to leave her capital untouched. But while her credit relations were revealed, her debts remained hidden due to her property situation. Her will, however, revealed the idea of social debts. Christina Neuhauserin took advantage of the opportunity for lifelong usufruct, held on to it during a second marriage, defended it against her second husband’s heirs, leased it to a relative of her first husband and continued to act as creditor and investor, yielding a substantial annual sum in interest payments, cash and possibly agricultural proceeds. She took charge of her own wealth and, in her will, provided for her poorer relatives and anyone else to whom she felt she owed gratitude in the form of legates or social debts. Given the absence of any children, she made full use of the legal testamentary limits to achieve this. In this respect and in terms of her wealth, she was a particular but not unique case in early modern Tyrol, whether considered as a widow, an agricultural entrepreneur or an interim administratrix. The transfer of familial wealth was crucial for women and men of all social statuses. But since women had less access to landed property, the size of their own wealth in relation to the value of their husbands’ real estate on which it was secured formed the basis of their financial scope and bargaining power. In Christina’s case, her wealth was almost equal to that of her husband, giving her considerable economic freedom and lifelong usufruct. Usufruct offered a unique opportunity for women, who were otherwise less likely than men to possess land. She could use the land and administer the debts secured on it, but she could not sell it or use it as collateral for her own purposes. However, she could use and keep the proceeds from the land’s yield and build up savings in cash and bonds. Christina Neuhauserin exploited pluri-activity to master this in an exemplary manner: engaging in lending, saving, agricultural entrepreneurship, textile production and trading, and the independent management of business and legal affairs in close cooperation with her gender guardians. This touches on the question of how far gender guardianship affected women’s legal and financial activities and contributed to their legal inequality.Footnote 81 Gender guardians were supposed to act as advisors, but also to represent women in court and monitor any proceedings affecting their property situation that might affect their scope of action. Our findings for this area suggest that gender guardianship did not necessarily limit women’s legal and financial involvement, and that they could even choose their own gender guardian to some extent.Footnote 82 However, the sources do not allow an assessment of the precise impact of this institution on women’s involvement, although references such as Christina’s bequests to her gender guardians provide valuable insights into their relationships.

Her case also confirms findings from other areas that show how widows acted as creditors and farm managers – although, unfortunately, she left no account book.Footnote 83 Christina does not appear to have left any financial debts other than the social debts documented in her will. This may indicate a preference for cash and credit similar to that of women in other areas. Elise Dermineur raises the question of whether women were less active as borrowers and finds for eighteenth-century France a proportionally lower participation of unmarried and widowed women borrowers in the notarial records, while married women increasingly borrowed together with their husbands. Widows of all social statuses did borrow, but they often lacked the collateral required to secure credit.Footnote 84 Evidence from pawnbrokers in Barcelona shows that women borrowed smaller amounts, but the creation of a Mont de Pietat for widows illustrates that their need for credit was acknowledged. Carbonell-Esteller finds that although only a fifth of all borrowers were women, half of them were widows using objects as collateral.Footnote 85 These findings suggest two things: widows had legal and financial capacity and needed credit but were often unable to offer collateral for larger loans. In Christina’s case, it is difficult to see how she could have run a farm without investing in it and leaving it in such good condition. She probably mortgaged the larger debts on the estate she held in usufruct – with the permission of her husband’s kin – while settling her other obligations in her will. Here, the documents conceal her activities as a borrower: these would have been recorded in the accounts and inventory of the estate (which have not survived) and not in her own.

This observation shows the importance of including property situations in tandem with gender relations in the analysis of credit and debt. In this research area, women possessed less landed property than men due to the prevailing succession practice and marital property law. This resulted in women also having fewer opportunities to take out mortgages as they rarely had the collateral to do so. Although marital status did make a difference in terms of women’s legal capacity, it did not make a difference in terms of property and the ability to borrow: a wife’s property status changed little upon widowhood – in both cases, she was less likely to have land as collateral. Even when women were granted properties in usufruct, as Christina Neuhauserin was, the restrictions on its use meant that they could not use this property as collateral to raise funds for themselves and their own business, but only for the benefit of the property in usufruct. Therefore, the lower level of debt among women might point not only to their credit practice but also to an unequal distribution of land ownership.

3. Innkeepers as pluri-active entrepreneurs

In the early modern period, inns were of crucial importance for the exchange of information, communication and local sociability, especially for men. They were also places where people gathered for consumption during events such as weddings or after town council meetings. Thus far, they have been mainly studied from socio-cultural and socio-political perspectives.Footnote 86 But inns were also central places for all those on the move: peddlers, carters and muleteers, merchants, mounted messengers, travelling artists, pilgrims and others. Thus, innkeepers were an important occupational group, but one that has been rather neglected in social history, especially in the context of early modern rural areas.Footnote 87 A few local studies examine individual innkeeper families in Tyrol, and a few focus on the hospitality industry, but with a stronger emphasis on the nineteenth century.Footnote 88 This is all the more surprising as innkeepers provided essential logistics and infrastructure, especially in regions where trade and transit traffic played a significant role. This was the case in Tyrol, where trade and transit traffic were extremely important economic sectors throughout the early modern period.Footnote 89 While trade relations, merchants and goods are traditional research topics, transport, as well as the necessary infrastructure and logistics, have not yet been systematically analysed – except for the transportation of timber.Footnote 90 In addition to local cooperatives that organized stage transportation of goods and freight forwarding, of which very little is known for Tyrol, innkeepers were heavily involved in providing the necessary facilities. In Tyrol, they were known as ‘Tafernwirte’ or ‘Gastgeb’ (hospes), and they ran an extensive business that included not only the tavern but also overnight accommodation for travellers of all kinds and their horses, even on country roads and in small market towns. Innkeepers had to obtain an official licence (Gerechtsame) to operate these usually large establishments.Footnote 91 They often also owned a larger farm or vineyard and carried out other activities: as butchers or bakers, traders or freight forwarders.

One of the most famous Tyroleans, Andreas Hofer, who led the 1809 uprising,Footnote 92 was an innkeeper at the Sandhof Inn in the Passeier Valley (at an altitude of 640 metres), just as his great-grandfather Kaspar Hofer almost 100 years earlier. He also traded in horses – as far as Verona and Bergamo (Italy) – and cattle, in wine, spirits and salt and was a freight forwarder and a mule-trader over the Jaufen Pass (2,094 metres) and the Timmelsjoch (at 2,474 metres) – the shortest routes between Meran/Merano and the Brenner Pass (1,370 metres) and today’s North Tyrol. In 1794, he owned 16 horses and ‘transported, collected and delivered most of the goods’ by himself.Footnote 93 With this pluri-active profile, he was a typical innkeeper of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries in this region. However, very few invoices and no bookkeeping records have survived from these extensive economic activities. Several writing slates appear in an earlier inventory of the inn.Footnote 94

The privilege granted by Claudia de Medici in 1635 in connection with the commercial jurisdiction of the Bolzano fairs mentions wine, grain, livestock and leather as goods traded by local operators, including innkeepers.Footnote 95 From a local perspective, innkeepers of this sort usually had considerable wealth and belonged to the elite. The fact that inns on transit routes were considered a good source of income at the time is also evident from taxation. In a 1634 house tax list, the ‘noble inns near the main roads (Landstraße) and villages’ were assessed at a multiple of 25 fl, whereas the ‘noble farmhouse’ was taxed at 4 fl.Footnote 96

3.1. Martin Schenk – Innkeeper in Kastelruth

There is no doubt that the owners of larger inns were literate and numerate. Three findings support this: firstly, references to account books in inventories and some of the innkeepers’ account books preserved in archives; secondly, the provisions in the wills of fathers of minor children that their sons should learn to read, write and do arithmetic; and thirdly, the frequent appearance of innkeepers in court records as holders of public office, including as guardians who administered the assets of their wards and had to present accounts for them.Footnote 97 They also appear to have been involved in buying and selling property and acting as local lenders. One innkeeper with the skills to carry out all these activities was Martin Schenk from Kastelruth, situated at an altitude of over 1,000 metres at a connecting route between Grödental/Val Gardena and Bolzano.Footnote 98 The fact that, on his death in 1781, debts owed to him by others totalling 8,000 fl were offset by 3,000 fl of debts that he owed to others, as well as the numerous and regular entries in the annual court books, suggests that he was very active in economic terms. It is also noteworthy that the record of the probate proceedings in the court book, including the inventory, subsequent negotiations and contracts, comprises almost 140 folios, or just under 280 pages.Footnote 99 A not inconsiderable part of this is devoted to clarifying the debts and the debtors. Following some of the documented money flows and examining the practices used to record and track them also reveals what scope for action becomes apparent. The comprehensive documentation allows us to trace this iterative process ‘up close’.

Martin Schenk, the innkeeper at the Lamb Inn in Kastelruth, died on 15 February 1781 at the age of 42, in the middle of his life and his economic activities. He left behind his widowed wife Ursula Schenkin, who was also an innkeeper’s daughter, and three minor children, two sons and a daughter: Johann (12), Martin (6) and Anna (14). He had taken over the inn from his father in 1766, 15 years earlier, upon his marriage. The inventory does not contain any luxury items: nothing in velvet and silk, but some items that indicate a respectable lifestyle. For example, he owned silver cutlery and a silver salt cellar, 60 ells (about 48 metres) of fine linen and other items typical of the eighteenth century: a ‘Comodkasten’ (chest of drawers) – in French spelling with a C rather than a K, a ‘new fashion’ brass pendant lamp, six black leather armchairs, pillowcases and bedcovers with blue print.Footnote 100 The innkeeper’s trade is reflected in the inventory, which includes a large quantity of beds, tables and bed linen, as well as stocks of over 200 pounds of salted ox meat, over 100 pounds of salted meat and a rich wine cellar. Martin Schenk also left behind a comparatively large amount of cash in the form of various gold and silver coins – a total of over 1,700 fl – as well as a gold assay balance.Footnote 101

The inventory also lists debts both owed to and owed by Martin Schenk. As mentioned in the introduction, the debts listed in the inventories are, of course, only a snapshot. What is not visible, however, is everything that was already paid during the 15 years from 1766 to 1781. Several documents relating to Martin Schenk appear in the court records almost every year. In the case of loans and debts, these are usually receipts from creditors – both men and women – who repaid him, or promissory notes detailing the repayment terms. In one case, a promissory note was transferred from one debtor to another. In 1769, the court in present-day East Tyrol was tasked with collecting a debt. A certificate of indebtedness from 1754, originally issued to Martin Schenk’s then deceased father, was transferred to Martin Schenk in 1771. Conversely, Martin Schenk junior appears in a 1767 confirmation as owing 50 gulden to his father.Footnote 102

As Craig Muldrew has pointed out, when assessing the significance of inventories, age or stage of life should always be included as an aspect that makes a difference.Footnote 103 In addition, and particularly important in this case, social status must also be taken into account. In comparison with other inventories and probate proceedings, Martin Schenk’s inventory was in itself an act that demonstrated his social status and affluence. The inventory was recorded very accurately, with much more detailed information than usual. More care was taken not only in describing the items and outstanding debts but also in describing the entire inventory procedure. Similarly, the process of clarifying the outstanding debts in court was made explicit at each stage: which appraisers came to the inn and when; what was recorded; what was negotiated and agreed, and with whom in court and when, etc. This makes the case particularly well-documented and therefore ideal for tracing how debts were ascertained and made visible. The focus here is therefore on the process of identifying and making visible the debts, especially those owed to him as a creditor – which has many facets – with the aim of clarifying the scope of action more clearly.

The outstanding debts to be collected are listed at 8,095 fl. The sum he owed to others was much less at 2,958 fl. The total value of the real estate was estimated at 9,978 fl, and together with the movable goods, valued at 3,904 fl, the total assets amounted to 21,978 fl. The debts had to be deducted from this sum, as well as the widow’s marriage portion and her other assets, worth 1,620 fl. This left assets of 17,400 fl on his side, which was a considerable fortune in those days, especially in a rural context.Footnote 104 At the same time, his widow’s wealth was substantially lower, and she was his main creditor. His own debts are recorded as ‘good’ debts. He had used the money to buy fields and, in 1775, the Spissegg Gut farm for 5,200 fl.

In the course of the probate proceedings, many details of loans and debts were provided. It is mentioned that Martin Schenk himself recorded smaller outstanding debts in small account books known as Aufschreibbüchlein. Unfortunately, these have not survived. Reference is made to a list of documents he kept at home, including some promissory notes and a bill. In addition to documents relating to ownership issues, the debts that appeared here are also listed in the inventory. This includes a bill of sale for a field he bought from his ‘cousin’ Annanias Paul Kerschbaumer, a local court representative and the innkeeper at the Wolf Inn; a bill of sale from 1767 for a meadow; the bill of sale of the Spissegg Gut farm in Kastelruth – which he acquired after Domenikus Planner’s death in 1775 – and the corresponding ‘debt transfer’ document, a specification of how the purchase was to be financed; several promissory notes for 100 and over 200 fl, including a debt transfer from Martin Schenk to his brother Matthias. Remarkable is the ‘avowal of debt’ by Johann Brosliner (Prossliner) from the Thomasett Gut in Kastelruth,Footnote 105 dated 3 February 1781 – shortly before Martin Schenk’s death. Schenk was ill, and his death was not entirely unexpected. Perhaps he felt that these debts were risky, which is why he wanted them documented in writing.

4.1. After Martin Schenk – clarifying debts in a complex procedure

The inventory procedure began on 5 March 1781 in the inn’s tavern, and two days later, on 7 March, the description of Martin Schenk’s papers was due. The financial records, as well as documents relating to property rights, were kept in a desk in the best room (Stubenkammer), usually the master bedroom above the heated living area. A writing slate is also mentioned. The first of the 23 paper items in the inventory for this day was ‘a large folio account book’, in which the wine contracts were recorded at the beginning and some ‘debts’ at the end. There is also a smaller account book ‘in quarto’, in which various ‘current debts and wine debts’ were recorded, as well as a ‘paquet’, a package, with 13 calendars, which again contained various wine debts, as well as ‘other smaller debts’. The calendars cover the period from 1766, when Martin Schenk took over the inn from his father, to 1780.Footnote 106 As the successor to the estate, he was in a strong position to begin his entrepreneurial activities. However, succession also meant that he assumed the debts and the terms negotiated with his father. As we will see, the debts recorded in the ‘account books and calendars’, as well as on the ‘writing slate’, amounted to a total of 453 fl.Footnote 107 At this point in the proceedings, Anton Gasser, the innkeeper at the Cross Inn and the children’s guardian, was involved in dealing with the debts.Footnote 108 The two account books and the calendars were handed over to him ‘for better information’, as he was assigned the task of collecting the outstanding debts recorded there within four weeks, after which he was to return the books. He was married to Maria Schenkin, the sister of Martin Schenk, and was therefore the deceased’s brother-in-law.

The pending debts recorded in the account books were entered in the court book as part of the inventory, alongside a description of his real estate and the sums of money to which Martin Schenk was entitled.Footnote 109 Unlike many other inventories of the time and region, this part is not a simple list of persons and amounts with a few sparse specifications but rather a very detailed documentation of the debt situation and how the debts were determined. Each item takes up one or two pages, and in the most complicated case, even more. This record was made at the court on 28 March 1781, two weeks after the inventory of documents was taken. The purpose was to clarify the children’s assets and their status as principal heirs to their father’s estate. Relatives from both sides were present: the guardian of the children from the Cross Inn, Martin Schenk’s uncle Johann Schenk, a braid maker who very often appears alongside Martin Schenk in documents relating to financial matters, the widow with her gender guardian and her father, an innkeeper from the neighbouring village of Gufidaun.

This section is also exceptionally detailed. It begins with Martin Schenk’s claims, which he had inherited from his father. These claims were based on the probate proceedings of 1768, drawn up 13 years earlier on the occasion of Martin Schenk senior’s death. The total value of the claims amounted to less than 1,000 fl, while the estimated value of the property taken over was almost 10,000 fl.Footnote 110 Item by item, the details were gone through, updated and – where necessary – extensively researched. Some debts had remained the same as interest had been paid annually; some had grown considerably in the meantime; others had undergone complex shifts to other debtors through a process known as ‘debt transfer’ (Schuldenüberbindung); and some had been paid off. There are repeated references to promissory notes and receipts as the documents on which they relied. All references to official documents are dated and can be traced in the court records.

Court records were also consulted on various occasions, but the knowledge of those present at the time of the proceedings seems to have been very important too, particularly with regard to debts that had already been paid. In the most complicated case, it was revealed that the wrong debtor had been recorded in the small account book: Michael Mulser instead of his brother, Johann Mulser. The money was Martin Schenk’s maternal inheritance, which he had originally advanced to Michael Mulser so that his wife could buy a house for 500 fl on the basis of a repurchase right linked to kinship. Clarifying this ‘clerical error’ was a very complex procedure. Both brothers were summoned one after the other. It is noted that ‘every effort was made to resolve this error by searching through various court records’. In addition, ‘multiple investigations’ into the financial damages that had occurred in the meantime are reported. As a result, the damages could finally be ascertained. Yet it was not until the end of the proceedings that a receipt dated 14 February 1775 was found, showing that Michael had paid his brother Johann Mulser 445 fl in cash.

The claims from Schenk’s time as an innkeeper were dealt with the next day, on 29 March 1781. It is evident that he had repeatedly stepped into existing loans and taken over larger sums – there was a telling expression in the sources that captured this practice perfectly: ‘following in one’s footsteps’. The largest debt owed to him was from the buyers of the Zulend Gut farm, which Martin Schenk had inherited from his father and sold for 3,600 fl in 1775 – the same year he bought the aforementioned Spissegg Gut farm. Also included were a number of ‘avowals of debt’ (Schulds-Einbekenntnisse) recorded on this court day, some of which were due on two specific saints’ days: Jacobi and Georgi. There were also debts owed to him and unpaid interest from the 1770s, including for wine.Footnote 111 The proceedings continued on 30 March with the irrecoverable debts owed to him, a total of 275 fl and 11 kreuzer, the already mentioned outstanding debts from the little notebook, Aufschreibbüchlein, which were considered recoverable, many without specification, and outstanding payments for ‘enjoyed food and drink’ (Zehrung), for a wedding feast or a baptism – a total of 453 fl 49 kreuzer.Footnote 112

Carefully reconstructing the debts that had to be repaid to Martin Schenk or his heirs reveals various practices relating to the recording of and dealing with debts. Three modes of recording can be identified. Debts were, first, recorded by Martin Schenk himself in books of different sizes. These were presumably intended for different types of debt: wine debts were recorded in the calendars, debts incurred at the tavern were noted in the Aufschreibbüchlein and other debts were entered in the larger books. Only their description has survived, unless the originals surface in the archives one day.Footnote 113 Second, he kept bills and promissory notes in a desk, and third, debts appear in the inventory, as well as the procedure for establishing them. It is clear that debts were expected to be paid, often in instalments and over a long period of time, even spanning generations, but there were also debts that were considered irrecoverable and written off. Therefore, the time frame of debts could range from short term to intergenerational, and they had to be kept on record. Payments and debts were also written down between relatives, including those very close to the wife’s marriage portion. In 1767, one year before Martin Schenk’s father died, we find an acknowledgement of debt by his son, our protagonist, to his father for 50 fl.Footnote 114

Depending on how debts were documented, the effort required to determine them varied greatly. Some promissory notes and receipts were drawn up in court and included in the court registers. Others were simply kept at home in a drawer or chest, and, not least, there were also verbal agreements. The logic behind these different modes is difficult to grasp. It can be assumed that official documentation was primarily created in cases where it was considered useful or necessary to secure the matter in court. Martin Schenk is referred to in the sources only as ‘innkeeper at the Lamb Inn’, but the debt records clearly indicate that he also traded in wine. He was able to start his economic activity by taking over the property that his parents had built up. The debts he inherited from his father again point to the procedural nature of debt.

4. Concluding remarks: rural entrepreneurs and credit management

An in-depth contextualization of the probate inventories of two individuals revealed a large scope of financial activities. Tracing how money was handled showed their pluri-activities and explained their credit relations beyond the list of claims and liabilities. Their legal and gender contexts also provided insight into the reasons behind missing debts and the property situation of these two individuals, which would have been overlooked in an aggregate analysis of listed debts and credits. The results from our integrated approach to the rural economy can reveal scope for action that cannot be retrieved from other sources, thus filling the gap of missing information on past financial transactions. This approach identifies debts and credits for which no documents have survived, but which have been recorded in other contexts. It can point to ‘social debts’ settled in wills and to the possibility of settling debts in cash, either formally, by letter, as in the case of the innkeeper, or informally, as was probably the case for the widow Neuhauserin. Contextualization can further indicate the possibility of mortgaging land held in usufruct. An integrated approach can also uncover other activities of the actors that are not mentioned elsewhere, such as the trade in wine or textiles. Finally, focusing on the ownership situation can clarify whether hypothecary debts were possible or if such credit sources were absent. Debt and credit in context can thus open a window into the further economic spheres of rural women and men, their gender-specific differences and their complex credit and debt relations. This can inform and substantiate results from the aggregate analysis of credit and debt.

The findings challenge and enhance existing concepts of rural economies. The two case studies have shown that tracing credit and debt among female and male entrepreneurs, and reconstructing their financial domains and social statuses, can significantly enrich and expand existing concepts of rural economies, such as the ‘integrated peasant economy’, or the idea of agricultural producers as merchants and traders. The ‘integrated peasant economy’ concept assumes ‘multiple sources of income’, particularly in ‘upland areas’, but it obscures the concept of pluri-activity.Footnote 115 Christina Neuhauerin was most probably primarily a farmer, but the prosperity of her family and the farm she married into can only be explained by her trading activities and financial acumen. Martin Schenk, the innkeeper, also owned a farm, traded in wine and granted loans. Both had lent out far more than they owed.

Aleksander Panjek, Jesper Larsson and Luca Mocarelli, proponents of the ‘integrated peasant economy’ approach, primarily argue from the perspective of economic necessity in relation to peasant market integration. However, we advocate taking a closer look at the multiple entrepreneurial activities that cannot be attributed solely to existential necessity, which involve not only men but also women, as the two case studies show. In rural Tyrol, where grain cultivation, animal husbandry, trade and transit traffic shaped the early modern economy much more than manufacturing, areas close to the trade routes between the valleys may have offered excellent income opportunities, most likely through trade in grain, livestock, dairy and wine. This has not yet been clearly demonstrated for Tyrol.

Our results also show that we need to consider the ways in which loans and debts were documented. This can be achieved by correlating chains of documents spanning several decades and by examining a comprehensive inventory that listed both the ways in which debts were recorded and the material forms they were kept in at the house, and also described in detail the various types of assets, outstanding debts and the search for unrecorded debts. Thus, the results of the qualitative contextualization of probate inventories broaden our understanding of the use of law and writing in early modern rural society. A more dynamic view of this source material is also supported by considering their references to other documents of various kinds, as well as to account books and other media used for recording, even if these have not survived.