Introduction

On 1 May 1940, the bodies of two men washed up on a Colombian beach near the seaport in Barranquilla. The documents that they were carrying identified them as Luis Hornes Sabando and Antonio Corominas Giral. They were taken inland and buried in the city. The following day, another body belonging to Carlos Zumalacarregui was also found drowned, naked and so heavily decomposed that the local authorities had to bury him right there on the shore. He was only identified because someone who had seen him at the port recognised his missing leg, the result of a grenade blast injury during the Spanish Civil War.Footnote 1 News of the incident spread from Buenos Aires to New York as groups and individuals expressed their shock and sorrow at the event.Footnote 2

These three men – two Spanish and one Basque – were part of the mass exodus of refugees from Spain following the victory of the Nationalist forces in the civil war. The increasingly vengeful rhetoric of the triumphant leader Francisco Franco convinced many who had participated in the Spanish Republic – or merely supported it – that their lives would be at risk if they stayed. Pedro A. Vives, Pepa Vega and Jesús Oyamburu have shown that many of these individuals chose Latin America as their place of exile because of perceived language and cultural similarities and because the Americas seemed like a beacon of peace and prosperity in comparison to beleaguered Europe.Footnote 3 On top of this, certain Latin American political parties and populations had openly supported Republican Spain during the conflict and therefore seemed like a hospitable environment for refugees.Footnote 4 However, few studies have focussed on Republican exile in Colombia, and those that do tend to examine the exiles’ experiences in the country rather than the context in which they arrived.Footnote 5 But the fact that, in May 1940, three refugees wound up dead on the Colombian coast raises interesting questions about that country’s relationship with immigration from Spain in the mid-twentieth century. This article will pick up this thread by exploring how the Liberal governments of Alfonso López Pumarejo (1934–8) and Eduardo Santos (1938–42) as well as the wider Colombian public responded to the arrival of Republican refugees between 1936 and 1942.

I argue that race was central to Colombian state-building in this period, and that debates around immigration both reflected and were reinforced by the multiple, evolving ideas of race within the country. Historians are increasingly recognising the plurality of racialised discourses that existed in the 1930s and early 1940s, from official and popular interpretations of mestizaje to racialised conceptualisations of region and ideology.Footnote 6 What follows is an account of the interplay between these discourses and the debate around arrivals from Spain in the development of immigration policy. I therefore use the ‘undesirable immigrant’ as a conceptual tool to understand how racialised notions of ideology and culture came to define inclusion and exclusion in Colombia during the mid-twentieth century. The findings contribute new understandings to the diverse, and sometimes contradictory, ways in which Liberal governments understood citizenship during their four successive terms from 1930 to 1946.Footnote 7

Republican refugees serve as a particularly useful lens through which to understand the racialised ideas of belonging in mid-twentieth century Colombia. Despite Colombia only receiving a small influx when compared to other Latin American nations, the conflict in Spain and the subsequent refugee crisis occurred at a key time for the country.Footnote 8 The newly-inaugurated Liberal regime, concerned with ‘modernising’ the nation, grappled with questions of what place immigrants had in building this new society. Although not consistent across time, space or populations, the general attitude in Latin America towards Spanish immigrants was favourable from the late nineteenth century because they were seen as a potential ‘whitening’ force whose historical ties to the region made them more likely to integrate with local populations.Footnote 9 During the interwar period, however, heightened fear of international movements such as Communism drove many to fear what large contingents of new arrivals, particularly from Europe, might do to domestic politics. In this context, the Spanish Civil War and subsequent refugee crisis represented both an opportunity and a threat, and it loomed heavy in Colombian debates around immigration. Public discussion of and official responses to Republican refugees thus reveal the changes and continuities, conflicts and convergences in approaches to inclusion and exclusion in Colombia during the first half of the twentieth century. By drawing attention to a group that has received scant attention in the historiography on immigration to Colombia, I suggest the need to examine liminal spaces in order to gain greater insights into processes of state formation.

Focussing on Republican refugees also allows me to situate Colombia in a continental history of migration. The country has often been marginal in these histories given the general consensus that it has never been a country of immigrants.Footnote 10 Yet Colombia, like many of its neighbours, faced the prospect of mass arrivals from Spain in the aftermath of the civil war. This article therefore responds to Lina Britto and Ricardo López-Pedreros’ call to ask ‘how Colombia illustrates fundamental questions about the modern histories of the Americas’.Footnote 11 Works on other Latin American countries have shown that official and public anxiety over these immigrants was not unusual across the region. In Cuba, the Batista regime did not open its doors to refugees from Spain despite its sympathy for the Spanish Republic. Yet, unlike in Colombia, this owed more to the precarious economic situation on the island than nationalist sentiment.Footnote 12 Kevan Antonio Aguilar has demonstrated how the Mexican government did welcome Republicans in their thousands but, once these individuals arrived, they became subject to state surveillance as their supposed internationalist activity made them a threat to the country’s national revolution.Footnote 13 What the Colombian case illuminates is how these concerns developed prior to the refugees’ arrival and in ways that spanned the local, national and international levels. In addition, it shows how such anxieties were both informed by and helped inform the plurality of ideas about race within the country.

Indeed, the Republican refugee crisis was not the only such event in 1930s Europe: Nazi occupation of Eastern and Central Europe coupled with its growing antisemitic legislation sparked a mass exodus of Jews, many of whom also looked to Latin America. Luis Roniger and Leonardo Senkman found that the increase in visa applications from European Jews, combined with the notion that these immigrants were racially and culturally distinct from Latin American populations, pushed governments to implement new regulations to block or limit the arrival of Jewish refugees.Footnote 14 As Angélica Alba-Cuéllar has explored most recently, Colombia was no different and the tightening of restrictions in the late 1930s was largely targeted at these ‘undesirable’ immigrants.Footnote 15 Examining immigration from the angle of a different group arriving in Colombia during the period, I trace how concerns about a Jewish ‘invasion’ intersected with anxieties over a ‘red wave’ from Spain so that Republicans who may have previously been considered ‘useful’ were unofficially grouped into the category of ‘undesirable’ and blocked from coming to the country. The article therefore adds to literature in Spanish that has examined different Latin American nations’ approach towards Republican and Jewish immigration in the mid-twentieth century.Footnote 16 Unlike the comparative analysis undertaken in those works, here the emphasis will be on how Colombian ideas about and policy towards both groups developed in tandem.

Throughout the late 1930s, Colombian policy towards immigration from Spain responded to both domestic concerns and international developments. However, the Republican refugees themselves were not mere recipients of these policies. Through continual contact with Colombian officials and other expatriates and exiles, they were aware of both the possibilities for and restrictions against their emigration to Colombia. Republicans then exploited this knowledge and existing networks to navigate Colombian immigration law whilst local and national authorities responded to such action by implementing new policies and procedures. As well as being the object of debate around immigration to Colombia and subject to legislative restrictions, we will see how the refugees themselves helped shape immigration policy in the mid-twentieth century.

Deciding who can be considered a refugee represents a massive methodological issue, and any attempt to classify potential immigrants is going to be flawed. Though applicants increasingly appealed to their refugee status after the Spanish Civil War ended in March 1939, visa records are an imperfect source for determining someone’s political ideology, especially at a time when immigration restrictions centred around nationality. Even where it is possible to identify political leanings, the changing course of the conflict also affected who might fall into the category of refugee. Particularly during the first months of fighting, rightist Spaniards were subject to popular violence and, as battle arenas moved from one location to the next, individuals who were not necessarily vulnerable to direct attacks may have decided to leave their home.

For the purpose of this article, any individual from Spain who during the period under study requested a visa for reasons that were not explicitly commercial, transitory or returning home is classed as a refugee. This also reflects the way Colombians perceived Spanish immigration at the time. Though refugees came from diverse backgrounds and left for a variety of reasons, concerns around the number of Republicans looking to emigrate to the Americas, combined with the tendency of groups and individuals within Colombia to conflate Republican Spain with Communism meant that any Spaniard requesting residence in the country during the late 1930s and early 1940s was viewed with suspicion either by the government or by wider society.

Immigration before August 1930

Although a recurrent topic of political discussion, immigration never really became a key issue in Colombia prior to the twentieth century. As the nation changed its name and borders several times throughout the 1800s, each successive regime attempted to encourage immigration as a means of colonising territory. In the process, elites pondered the question of the ‘ideal immigrant’ and introduced sporadic pieces of legislation determining which foreigners could and could not settle in the country. However, in contrast to other Latin American nations, Colombia did not receive a significant number of immigrants during this period, something that Frédéric Martínez attributes to a lack of tangible state support in the context of ongoing internal conflict.Footnote 17 Ana Rhenals Doria and Francisco Javier Flórez Bolívar have further illustrated how those groups that did arrive were not necessarily from the parts of the world that leaders had intended.Footnote 18

Faced with the failure of their European immigration project, and amidst global interest in theories of scientific racism, Colombian governments turned their full attention towards immigration policy in the early twentieth century. During the next two decades, subsequent Conservative governments introduced a series of new laws which sought to better define the ‘ideal immigrant’ and control their arrival into and activity within Colombia. These statutes described ‘ideal’ immigration in ethnic and social terms and introduced provisions to expel foreigners involved in protests or strikes.Footnote 19 Perhaps the most important was Law 48 of 1920 which enshrined the principle of free immigration into law for the first time.Footnote 20 This was 67 years after the Argentinian constitution declared this same principle and the new Colombian rule included some restrictions based in part on the experiences of their regional neighbour. In Argentina, elites started blaming unrestricted immigration – and the immigrants themselves – for their country’s social, political and economic problems from the 1890s onwards.Footnote 21 Article 7 of the Colombian Law 48 (1920) therefore prohibited beggars, the homeless, the unemployed and those without ‘honourable’ jobs, sex traffickers, political agitators and convicted criminals from entering the country. It also included specific provisions to deny entry to anarchists and Communists, likely in response to growing fears about the spread of leftist ideas in the aftermath of the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia as well as the very real surge in anarchism across Latin America, driven in part by immigration from Europe.Footnote 22 As well as reflecting past experiences, these initial attempts to categorise ‘good’ and ‘bad’ immigration, in particular through linkages to occupation and ideology, provided important foundations for the future development of Colombian immigration policy.

The focus on potential arrivals’ social and ethnic characteristics reflected the ongoing debates about the Colombian ‘race’ which were intimately linked to the issue of immigration. In 1920, a group of students organised a series of conferences in Bogotá’s Municipal Theatre to discuss prominent psychiatrist Miguel Jiménez López’s theory that racial mixing combined with a tropical climate had led to the ‘degeneration’ of the Colombian race. Jiménez himself suggested that white immigration offered a solution to this ‘problem’.Footnote 23 In response, the surgeon and public intellectual Jorge Bejarano argued that the way to overcome the country’s perceived backwardness was not by encouraging European immigration but by refining the habits and behaviours of the current citizenry.Footnote 24 He emphasised that high birth rates proved the country would be able to effectively populate its territory, so the government should instead concentrate on creating better defences against poverty and unsanitary conditions.Footnote 25 For this task, Bejarano placed the onus on Colombian women, to whom he addressed this speech: ‘(I)n order to improve the physical condition of your children condemned to premature degeneration and decrepitude … seek in physical education the harmony and beauty of your body and mind.’ He implored: ‘Mothers! Remember that there is no better immigration than that of your own children!’Footnote 26 In doing so, he upheld a gendered view of society advanced by many eugenicists across the world that posited control of women’s bodies as key to ensuring the nation’s future. Although it is beyond the scope of this article to study the issue in depth, there are clear instances of ideas regarding gender influencing Colombian immigration policy. This, in turn, provided opportunities for certain migrants to circumvent the restrictions imposed upon them.

In contrast, those who supported immigration emphasised the vast swathes of ‘unsettled’ national territory in Colombia and the apparent ‘backwardness’ of the ‘Colombian race’ to support their view. Repeating an idea common across Latin America at the time, they advocated for settler colonialism to propel the country forward. Exemplary of this trend, the Colombian consul in Boston, Enrique Naranjo Martínez, published a series of essays on race and immigration in 1927. These were no doubt influenced by the Municipal Theatre conferences earlier that decade but were also shaped by his experience of living in a racially segregated US city. Indeed, he claimed that the United States would have been a ‘mediocre’ nation were it not for ‘the great masses of European settlers’. To follow the US example and ‘make a great and prosperous Nation’, Colombia needed ‘to populate the country’ and ‘attract great masses of well-selected immigration’. According to Naranjo, the benefits of this would be two-fold. On the one hand, the arrival of ‘Europe’s healthy population’ to ‘our uninhabited mountains and plains’ would bring economic development and, on the other, the ‘deficient’ Colombian population ‘would learn very quickly if they come into contact with civilised immigrants’. The consul clearly equated whiteness with progress and the timeline he gave for the policy to produce the desired results – 25 to 50 years – suggested the ‘learning’ he had in mind was more biological than socio-cultural.Footnote 27

Although not representative of all ideas about race, Bejarano and Naranjo’s views do give an idea of the contested and racialised conceptualisations of ‘backwardness’ and ‘modernity’ in early twentieth-century Colombia, as well as the global context within which such contestation occurred. Whilst the former employed neo-Lamarckian ideas to propose ‘uplifting’ the national ‘race’ through health and educational measures, the latter based his argument that European immigration was the only viable solution on Mendelian notions of heredity. In turn, these debates around how to tackle Colombia’s ‘race issue’ reflected wider discussions about the application of eugenics in Latin America.Footnote 28

Liberal Rule, Race and Immigration

It was against this backdrop of increasing regulation and discussion of immigration that the Liberal regime came into power in August 1930. During the following sixteen years of Liberal rule, successive governments embarked on a vast cultural and educational programme that sought to ‘modernise’ Colombia by enhancing political participation and broadening notions of citizenship. The new regime’s cultural policy was articulated as a clear break from previous Conservative administrations’ approach to popular sectors yet, as Catalina Muñoz Rojas has argued, Liberals still defined citizenship in hierarchical terms.Footnote 29 Accordingly, modernity was associated with white/mestizo, urban, Andean, professional men whilst all other groups were categorised as ‘backwards’ and in need of ‘civilisation’. One clear example of the tension between old and new was the emergence of an official discourse of mestizaje which, as Flórez Bolívar illustrates, implied a clear preference for the homogenisation of non-white groups even as it celebrated Colombia’s ‘mixed’ population.Footnote 30 At the same time, however, both authors suggest that the very existence of a narrative of wider citizenship provided popular sectors with both an opportunity and the discourse with which to dispute their place in the nation. In this context, debates around immigration became another way to define belonging relative to others, and immigration policy developed from the interplay of these diverse, racialised notions of citizenship. The restrictions that the different Liberal governments imposed on potential arrivals, in turn, shed further light on the boundaries of inclusion during this period.

Building upon concerns that free immigration was threatening Colombian national identity, and with a Conservative heading up the Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores (Ministry of Foreign Relations, MRREE), in 1931 the government of Enrique Olaya Herrera introduced a quota system for immigrants from various Eastern European, Asian and Middle Eastern nations.Footnote 31 This mirrored a similar system implemented by the US government in 1924, albeit with much lower numbers. Ten individuals from each of the nationalities covered in the decree were permitted to enter Colombia each year. By implicitly allowing for unrestricted arrivals from all other parts of Europe, the move also satisfied those who felt that select immigration would help modernise the country. Three additional decrees issued over the next four years added more nationalities to the restricted list and reduced the quota for some nationalities to five immigrants per year (it is not clear whether this figure included family members).Footnote 32

Alfonso López Pumarejo had assumed power by the time the final decree was issued. The new Liberal president was more radical than his predecessor and led an explicitly partisan government. It was his domestic programme – the Revolución en Marcha – that most drastically sought to redefine citizenship during the period of Liberal rule.Footnote 33 However, when it came to immigration, López continued Olaya’s overarching approach even as he adapted the means. The president found that the quota system was causing a bureaucratic nightmare because requests exceeded places by ten to one.Footnote 34 His government therefore modified immigration policy by removing all quotas and dividing potential immigrants into two categories: foreigners in general and those belonging to restricted nationalities. Decree 1194 of 1936 dealt with the latter, requiring that successful applications pay a deposit of between 100 and 1,000 pesos depending on their age and sex.Footnote 35 All other foreigners had to pay a reduced deposit of 250 pesos which did not apply to under-17s or unmarried women and for which an exemption would be granted if the individual had a work contract in Colombia.Footnote 36

The two Liberal governments’ stance on immigration highlighted how their vision for Colombia’s future was built on multiple, racialised understandings of who could best contribute to this ‘modern’ nation. Though not an imitation of nineteenth-century ideas of European migration as a source of development – both the presidents’ emphasis on immigrants ‘fitting in’ suggested that they did not necessarily share others’ pessimistic views about the Colombian ‘race’ – immigration policy did signal the tensions within the Liberal cultural programme aimed at enhancing citizenship. Whilst certain politicians and intellectuals espoused discourses of national identity that celebrated Colombia’s ‘mixed’ population, the governments implemented legislation that would prevent the arrival of non-white and non-Christian immigrants into the country lest they taint the national ‘race’. Yet the inclusion of Eastern European nations on the list of ‘undesirable’ nationalities also revealed how Communism itself was becoming a powerful racialised discourse that helped shape mid-twentieth-century immigration policy. These countries – which included Poland, Russia and the Baltic states – were historically Christian and ethnically white but increasingly associated with Bolshevism in the aftermath of the Russian Revolution. As we will see, the plurality of voices contributing to ideas of the ‘undesirable’ immigrant had significant consequences for Colombia’s approach towards Republican refugees in the late 1930s.

Public Concern about a ‘Red Wave’ from Spain

Notwithstanding the growing attention that officials and certain interested parties paid to immigration, the issue did not receive consistent and widespread attention in the country until the mid-1930s. Then, on 20 November 1936, the Barranquilla-based Conservative newspaper La Prensa announced on its front page that ‘29 COMMUNISTS ARRIVED AT PUERTO COLOMBIA FROM SPAIN’.Footnote 37 The story – which was later revealed to be false – was a reaction to the actions of neighbouring governments who were drafting bills to impede the entry of ‘undesirable elements’ from Spain, as well as a continuation of the Conservatives’ broader opposition to President López’s pro-Republican stance.Footnote 38 The journalist who wrote the story complained how the reported arrivals saw Colombia as an ‘ideal’ refuge given that ‘here they do not face the obstacles that other governments of Central and South America have erected as simple measures of social hygiene’.Footnote 39 By using eugenicist language to describe restrictive immigration laws, the author implied that the Spaniards’ presence would be harmful to Colombian society. This pathologisation of migrants was not unusual for the time, indeed, it is a phenomenon that has persisted into twenty-first-century debates around asylum seekers, but it is striking that in this particular case the supposed immigrants did not represent a particularly large contingent and, more importantly, their presence was not even confirmed.

Despite the report’s dubious veracity, it sent shockwaves across the country as it spread to the interior. Armando Carbonell, the Barranquilla correspondent for El Siglo, told readers that Colombia was ‘being invaded by Spanish Communists … without port authorities putting in place the slightest obstacle to such undesirable elements’.Footnote 40 El Tiempo’s daily news columnist referred to the purported arrivals as ‘pernicious travellers’ and ‘professional agitators’ who saw Latin America as fertile land for their corrupting ideologies.Footnote 41 Significantly, these two newspapers were the mouthpiece for moderate Liberals and the Conservative party respectively and so the fears of a ‘Communist invasion’ reflected their views on Republican Spain.Footnote 42

As Conservatives blamed lax government policy for the appearance of the unwanted Spanish guests, local authorities and civil society groups began to petition the government for tighter immigration restrictions. The day after the alleged incident, members of Barranquilla’s municipal council called for a national law to prohibit the entry of ‘an international sect that has engraved into its banners hatred against the concepts of nation, property, home and order’.Footnote 43 In Bogotá, a group of industry owners planned to submit their urgent request for ‘new measures restricting the immigration of dangerous foreigners whose disruptive aims are without doubt’ to top government officials.Footnote 44 Even after a correspondent disproved the particular case of the 29 Spanish extremists three days after the original report surfaced,Footnote 45 newspapers continued to discuss the ‘flood of Communists into Colombia’ for the rest of the year.Footnote 46

The spread and impact of this story underscores the importance of regional levels of analysis when considering attitudes towards immigration in Colombia. News of the supposed arrival of Communists from Spain began in Barranquilla, a city with the busiest seaport in the country during this period and therefore the greatest exposure to immigration flows. Moreover, as Louise Fawcett and Eduardo Posada-Carbó have shown, earlier Middle Eastern and Jewish migration to Colombia had concentrated in Barranquilla.Footnote 47 Although the authors argue that these groups were initially welcomed as a result of the prosperity they brought to the Caribbean region, Flórez Bolívar and Rhenals Doria’s study of Middle Eastern immigration to Colombia posited that they were the principle target of restrictive laws by the 1910s.Footnote 48 These specific historic experiences probably made Barranquilla’s elites and officials more sensitive to new arrivals than those in Bogotá. Yet, Fawcett and Posada-Carbó also trace how a separate wave of Jewish immigration from Europe in the mid-twentieth century shifted to the Colombian interior, which perhaps helps explain the convergences between the capital and the regions during the period under study.Footnote 49 Certainly, we will see how concerns about these new Jewish migrants were prevalent throughout the country and helped inform policy decisions in Bogotá in the late 1930s.

Despite murmurings of a potential influx of Communists from Spain, this was far from reflective of reality. Official visa records suggest that very few Spaniards were travelling to Colombia during the first few months of the Spanish Civil War. Less than three per cent (51) of the 1,894 identified requests came from the period July to December 1936, and several of these never actually arrived.Footnote 50 Those who did reach Colombia left for different reasons than later Republican refugees. For example, Ascensión Villalón y Mateo was the Spanish wife of Colombian citizen José Ignacio Sanclemente who was repatriated from Madrid in September 1936.Footnote 51 Sanclemente gave interviews to journalists on his return which implied that he and his wife were not particularly sympathetic towards the Republican cause.Footnote 52 Other arrivals were Republicans but not necessarily escaping the war. Luis de Zulueta, a politician and university professor, had been the Spanish Ambassador to the Vatican when the conflict erupted in Spain. Following a Nationalist campaign to have him expelled from this post, he travelled to Paris from where he wrote to Eduardo Santos enquiring about the possibility of emigrating to Colombia.Footnote 53 Indicative of an opportunism that will be discussed further down, the future president offered Zulueta a contract and even covered his travel expenses, meaning that he came to Colombia without ever having personally witnessed the fighting in Spain.Footnote 54

Notwithstanding the sensationalist nature of press reports about arrivals from Spain, the López government responded to the public outcry by instructing consular officials specifically on Spanish immigration. On 28 December 1936, the MRREE sent a confidential letter to the Colombian consul general in Paris, Leon Gómez, informing him of its decision to ‘restrict the ease with which Spaniards can come to the country’ and requesting that he issue a circular to all diplomats and consuls in Europe instructing them not to issue visas to Spaniards without first consulting with the Madrid Legation or Paris General Consulate.Footnote 55 The justification that the government gave for this action reveals the influence of anti-Spanish immigration campaigns. The measure to limit the arrival of Spaniards, Foreign Minister Gabriel Turbay later declared, was ‘in anticipation of future evils’ given that ‘many of them naturally profess doctrines contrary to our institutions and there is a danger that they will come to propagate these inconvenient doctrines, or simply that there will be many undesirable elements among them’.Footnote 56

However, López did not issue any decrees or legislation against Spanish immigration and his government was seemingly sympathetic towards the plight of the refugees. Hernando Téllez was the Colombian consul in the French port city of Marseille from September 1937 to October 1938. According to his son, Germán, who lived with Téllez in France: ‘Alfonso López Pumarejo named him consul in Marseille with a specific mission: provide a Colombian passport or visa for all European refugees … in particular giving priority to Spanish refugees’.Footnote 57 Certainly, Téllez’s appointment occurred during López’s presidency and the new consul replaced Jorge Castaño Castillo who had written a series of letters to the MRREE in early 1937 expressing his opposition to Republican immigration.Footnote 58 Whether or not López specifically authorised Téllez to accept refugees from Spain is harder to determine. Records from the Marseille consulate are absent from the period June 1937 to March 1938, although all of the 27 visa applications from Spaniards between April and October 1938 were approved. More broadly, 98 per cent of all Spaniards who applied for visas to Colombia between July 1936 and August 1938 when López stepped down had their requests granted (249 of 253).Footnote 59 This suggests that the López administration did look favourably on Spanish immigration despite concerns about ‘inconvenient doctrines’.

The Issue of Assimilation

When Eduardo Santos took office in 1938, he inherited an immigration policy that was still open to Spanish immigration even if it recognised public anxieties around arrivals from Spain. The new Liberal president had been elected amidst widespread opposition to López’s domestic reforms which many felt were auguring Communism in Colombia, so he toned down some of the previous regime’s radical rhetoric even as he continued many of its policies.Footnote 60 Santos’s presidency also coincided with a significant moment in the Spanish Civil War. The Nationalists had just won the Aragón offensive and were looking increasingly likely to win the war.Footnote 61 By February 1939, Franco published the Law of Political Responsibilities which declared as military rebels all Popular Front supporters and those who had opposed the July 1936 coup.Footnote 62 The Nationalist advance and concomitant repression forced an increasing number of Republicans across the French border and into exile.

Colombian visa records reflect this surge in the number of Republican refugees. After August 1938, applications from Spain steadily started to creep up until they exploded the following year. Requests from 1939 account for 52 per cent of all visa applications during the period under study.Footnote 63 A report from Gregorio Obregón, Colombian Minister in Paris, described how the final two months of war, February and March 1939, were ‘an intense period’ in which ‘practically all working hours were absorbed’ by requests for visas from Spanish refugees. Even in June, as he penned the letter to the MRREE, he complained that ‘the demand continues’.Footnote 64 What was a practical problem for Obregón became a public issue in Colombia as the increased demand gave way to greater numbers of arrivals from Spain. Newspapers, particularly in port cities, began to complain about these ‘red refugees’ and local business interests started to worry about the impact of these new immigrants on the economy.Footnote 65

These reports once again brought the issue of immigration into the public sphere. Writing in his regular column for the Bogotá-based El Liberal, Armando Solano complained that ‘every businessman and peddler feels they have the right to demand that a group of foreigners not be received in the country’. He continued, ‘no one wants to think about the economic growth, population betterment and cultural uplifting that would result from the arrival of a certain class of immigrant’. As a result, Colombia ‘stays as it is, without increased consumption, without crop development, without exporting products. Meanwhile, only Argentina and other countries with strong immigration are making solid progress in America.’ Solano thus continued the tradition of linking European immigration to development and comparing Colombia’s record unfavourably with that of its regional neighbours. Turning to the matter of Republican refugees, Solano declared that ‘the bulk of Spanish immigration will undoubtedly be made up of farm labourers, artisans and the middle classes … Those who … claim that all these people are Communists … are wrong. They are simply dignified and loyal men who succumbed in the fight for Spain’s independence and freedom.’Footnote 66

Responding to these comments, El Siglo’s daily news columnist argued that, whilst it was ‘logical that a leftist like Solano requests … that we make space in our nation for all these types of people’, the dangers of such an approach were clear. He considered the ‘two sides of the problem … ideological and material’. The latter related to the inconvenience of ‘hand(ing) over to foreigners our land, that the rural Colombian masses desperately need’ and therefore harked back to previous arguments against immigration in general. The former referred to Republican refugees in particular because ‘they will in one way or another promote leftist ideas’ which would mean ‘the spiritual values of (our) nation may be subject to attack’.Footnote 67 In this way, departing from previous assertions about the desirability of Spanish immigration because of cultural similarities, certain sectors of society considered Republicans to be alien in the same way as the nationalities covered by Decree 1194 of 1936. Concerns about potential immigrants’ ‘inconvenient social characteristics’ that had their roots in early twentieth-century legislation began to concretise in light of the seemingly imminent arrival of refugees from Spain.

Yet Republican refugees were not the only group arriving in Colombia in the late 1930s. Between Santos assuming the presidency and March 1939 when these articles were written, the country had also received many visa requests from Central European Jews who were fleeing Nazi persecution. Indeed, the 1938 census found that of the 56,487 foreign residents in Colombia, approximately 2,300 were Spanish whilst the Jewish population totalled 3,500.Footnote 68 A 1941 study of German Jews in Colombia suggests that many of the new arrivals struggled to effectively integrate as they encountered language barriers and few employment opportunities.Footnote 69 In this context, starting in mid-1938, various Colombians began to consider the issue of ‘desirable’ and ‘undesirable’ immigration more carefully with a particular emphasis on where Jewish groups fit in Latin American society.

Such considerations were expressed via the concept of ‘assimilation’ and often drew on international experiences. For instance, the leading Conservative newspaper in Cali, Diario del Pacífico, expressed its support for immigration but stated that ‘assimilation is fundamental’ because ‘it is not just about populating but populating with assimilable elements’. Once again framing the issue of immigration in Colombia within a regional context, the author of the piece on ‘Immigration and racial conflict’ pointed to the US example and asked: ‘if a country with the United States’ imposing greatness has not managed to unite the diverse racial elements … what can the less progressive nations of America expect?’ Interestingly, given other Conservatives’ stance on Spanish immigration, the Diario del Pacífico article concluded that Colombia should ‘resoundingly reject’ all unassimilable races and only accept those who were racially similar such as Spaniards and Italians.Footnote 70

The idea that certain ‘races’ were undesirable in Colombia was not limited to Conservative groups. The Cartagena-based Liberal newspaper El Heraldo published an editorial entitled ‘About Immigration’ in June 1938. Though the editorialist reassured readers that he was not calling for ‘a banner of persecution against immigrants from a particular nationality or race’, he did declare the need for ‘each country (to) encourage the immigration that most suits their international, commercial and even racial interests’.Footnote 71 He did not refer specifically to Jewish immigrants in the editorial, but given that the newspaper had published a front-page story two days prior about ‘200 Jews illegally entering the country each month’, it was clear who the author considered unsuitable.Footnote 72 Crucially, the department of Valle and the Caribbean region had the second and third largest Jewish populations respectively in 1939, which possibly explains why journalists in Cali and Cartagena were particularly concerned with the assimilability of these new arrivals.Footnote 73

Both articles, along with a slew of other antisemitic ones published in response to news stories about Jewish immigration, called for the government to implement tighter restrictions. Santos was clearly aware of these demands because he made immigration policy one of his top priorities after assuming the presidency in August 1938. On 10 September, the MRREE sent a circular to all diplomatic and consular officials informing them of new dispositions on immigration that would come into place on 1 November. These included fines for consuls who issued visas to ‘dangerous foreigners’ and new authority for port captains to block any immigration whose visa did not detail the precise date of MRREE authorisation.Footnote 74 Within Colombia, the new Foreign Minister Luis López de Mesa made the Immigration Office its own administrative department within the ministry (previously it had been part of the consular section). He also set up an immigration board that oversaw all visa requests and automatically rejected those from individuals who had no ties to Colombia.

The government tightened restrictions again on 23 September 1938 when it issued Decree 1723, which ruled that only consuls with Colombian nationality could issue visas and these were obliged to inform their diplomatic representative about every application they approved. Further, where the applicant belonged to one of the nationalities covered by Decree 1194 or had lost their nationality, only the MRREE had the authority to authorise a visa. Finally, the new disposition doubled the deposit for the restricted group so that the fees now ranged from 200 to 2,000 pesos and it also set harsher conditions for the return of these deposits.Footnote 75

The addition of those who had lost their nationality to the list of restricted groups was significant because, since 1935, the Nazi party in government had stripped German Jews of their citizenship. The move was undoubtedly facilitated by the fact that, two months earlier, the Évian Conference to discuss Jewish refugees fleeing Germany and Austria, in which Colombia had participated, failed to implement any international agreement on accepting these individuals. Chillingly, the decree also came into effect on the same day that the Nazi regime invalidated all German passports held by Jews. Then, at the end of October 1938, Liberal Senator Max Grillo submitted a draft bill on immigration which sought to turn Decree 1723 into law.Footnote 76 Jewish immigrants had officially been defined as ‘undesirable’ in Colombia, highlighting the prevalent antisemitism within the Liberal Party and the country more generally.Footnote 77 This antisemitism, in turn, exposed the underside of official, celebratory discourses of mestizaje: Colombia’s ‘mixed’ population was being defined in relation to racialised ‘others’ who were then categorised as being outside of the nation and subjected to discrimination.

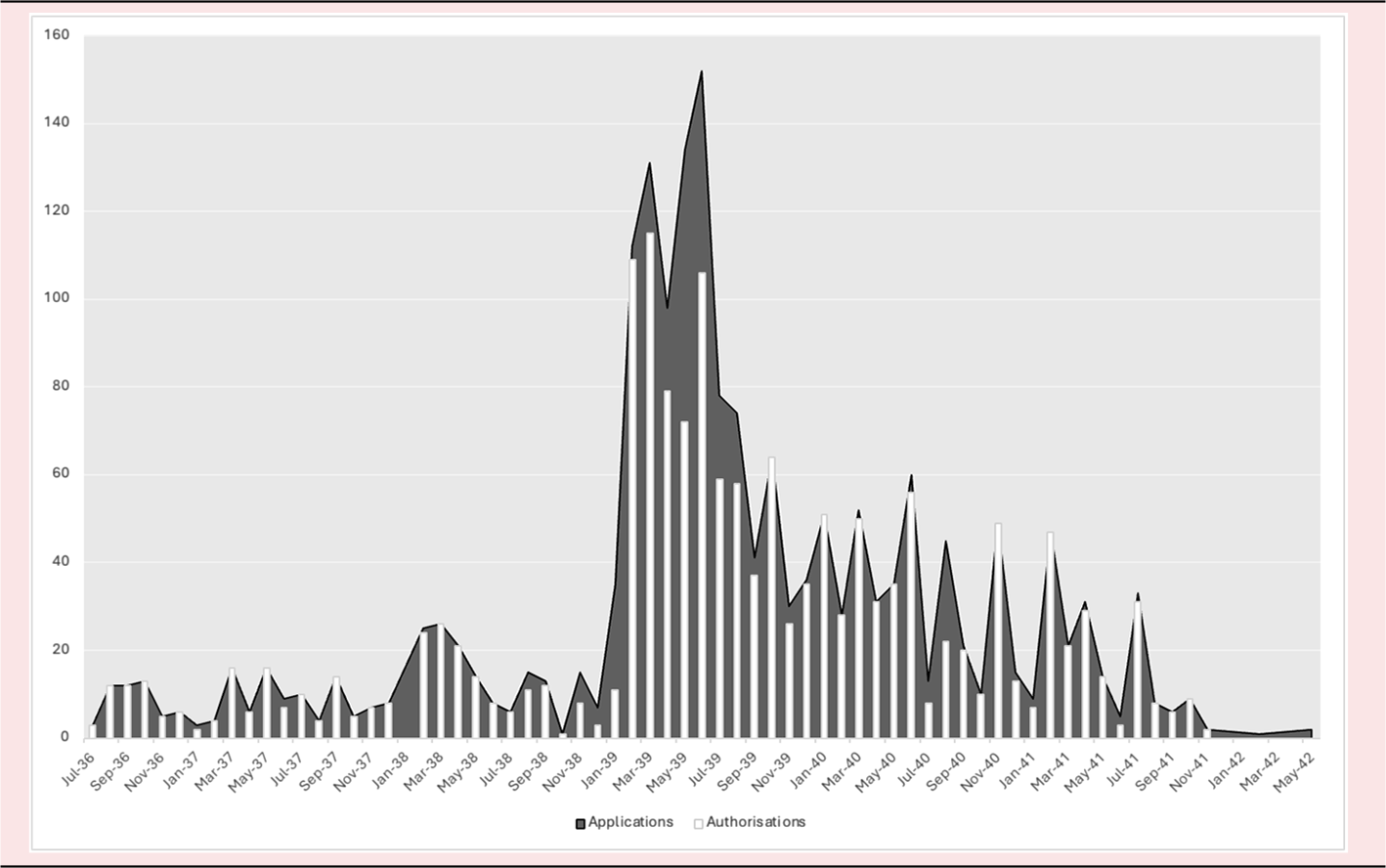

Concerns about the assimilability of Republican refugees therefore need to be understood within the broader framework of Colombian constructions of the ‘undesirable immigrant’. Given the politicisation of the Spanish conflict in Colombia, Republicans were increasingly lumped into this category. Indeed, Figure 1 suggests that the introduction of Decree 1723 affected the percentage of visa authorisations for applicants from Spain, which began to fall in November 1938. From the initial fears about the ‘Spanish Communists’ discussed above, different sectors of Colombian society developed wider anxieties about Republican Spain whose proponents on the peninsula and in Colombia were seen to have abandoned traditional Spanish values. Though the sense of what these values were varied – ruling Liberals equated the Second Spanish Republic with democracy and liberty whilst Conservative leaders celebrated the religiosity, morality and hierarchy of imperial Hapsburg Spain – all agreed that they formed part of a shared Spanish-Colombian heritage.Footnote 78 By departing from this sense of Spanish identity through their purported association with Communism, Republicans were no longer suited to Colombia’s racial and international interests. Given that the legal framework was already in place to exclude ‘undesirables’, officials began to use these dispositions to block mass Spanish immigration even as Spaniards were never officially defined as a restricted nationality.

Figure 1. Visa applications to Colombia from Spanish citizens and authorisations, July 1936 to May 1942

In February 1939, López de Mesa received a telegram from the consul in Paris asking for instructions on the reach of Article 1 of Decree 1723 in light of the growing number of visa requests from Republican refugees.Footnote 79 The article in question was that which prohibited consuls from issuing visas to anyone who had lost their nationality or was suffering limitations to their political and civil rights. Although no disposition at the time included restrictions against Spanish citizens, we have seen how increasingly restrictive immigration laws were already affecting their chances of getting a visa. López de Mesa decided to formalise this process. In June, as Obregón reported on the situation of Republican refugees in Paris, he noted a recent requirement to submit visa requests from Spain to the same legal requirements as those from persecuted minorities. Obregón, reaffirming his desire to ‘harmonise humanitarian concerns with our national interest’, declared that he had not issued a single visa to any Republican refugee since receiving the new decree.Footnote 80

The declining rates of visa authorisations in Figure 1 above bear witness to this shift in policy. From May 1939, the MRREE started rejecting visa applications en masse on the basis that ‘there are already a hundred or so Spanish refugees (in Colombia) who do not have a job, thus creating a serious problem for the government’.Footnote 81 The following month, the ministry officially suspended immigration of those referred to in Decree 1723 whilst they reformed the existing dispositions. Although Spaniards were still not formally covered by this decree, many visa requests from Republican refugees in the latter half of 1939 were rejected on these grounds. Then, in October, the MRREE began to inform applicants that it had been forced to change its policy on Spanish immigration, allowing this only when potential immigrants had an economic connection in Colombia.Footnote 82 From May to December, the authorisation rate for Republican refugees requesting visas fell to 73 per cent. Of the 457 individuals who did obtain permission, nearly a third were required to pay a deposit and even those who were exempted received emphatic warnings about the potential economic difficulties they might face.Footnote 83 Thus, where the MRREE could find no legal reason to block visa applications from Spanish citizens, it sought alternative ways to discourage them from travelling to Colombia.

A Dual Approach to Republican Immigration

Of course, the government’s approval of the majority of visa requests shows that some Republican refugees were still welcome in Colombia. The high acceptance rate reflected the practice of many consuls who, like Obregón, turned potential immigrants away without ever submitting their requests to the MRREE. It also responded in part to the aforementioned loophole which meant that even individuals from ‘undesirable’ nationalities could come to Colombia if they had an economic connection in the country. There is evidence that Republican refugees were both aware of and tried to exploit these opportunities. An MRREE circular from 13 October 1938 drew consuls’ attention to the fact that certain foreigners already in Colombia were drawing up fake work contracts in order to facilitate the entry of family members and friends into the country.Footnote 84 This article’s final section will examine in more detail how Republican refugees were able to navigate the restrictions against them.

The continued arrival of Republican refugees despite increasing restrictions against Spanish immigration was also a result of a dual policy of preventing the Republican masses from entering Colombia following the defeat of their government, whilst allowing for the cherry-picking of a select few exiles who would be able to contribute towards the Santos government’s cultural, educational and agricultural programmes. As López de Mesa told Congress in 1939, the government ‘had to take special measures to impede the arrival (of thousands of Spanish citizens) to Colombia … limiting favourable resolutions to individual cases’.Footnote 85 This dual policy required a conceptual divide between the ‘undesirable’ masses and the ‘cultured’ few, and both the president and foreign minister helped construct this division. The latter had long been concerned with the issue of immigration as an extension of his preoccupation with ‘uplifting’ the Colombian ‘race’. Indeed, López de Mesa had been one of the proponents of immigration during the Municipal Theatre conferences in 1920. However, he reiterated and further refined these ideas in his Disertación sociológica, published in 1939. By then foreign minister, López de Mesa explored how other Latin American countries, particularly Chile, Argentina and Brazil, had been able to temper the presence of Indigenous and Black populations by encouraging European immigration. Drawing upon these experiences, he concluded that Colombia ‘would benefit from the targeted injection of select immigration in certain regions’ to counteract the high levels of ‘immigrants of dubious racial and cultural benefit’.Footnote 86 Here, the foreign minister referred to the racialised interpretations of Colombian regions that had become naturalised in the mid-nineteenth century and were subsequently used to measure the relative progress and modernity of different parts of the country.Footnote 87

The key term in López de Mesa’s conclusion was ‘select’ and, in his response to the Republican refugee crisis, the foreign minister made clear what type of immigration he felt the government should be choosing. As head of the Immigration and Colonisation Committee, established on 14 March 1939, he led a detailed investigation into existing immigration legislation and potential areas for foreign settlement. He thus wrote to the National Audit Office requesting census data on existing arts, trades and professions so that he could study ‘the possibility of using the services of technicians and other workers qualified in trades, professions or industries that do not exist in Colombia but whose development could be beneficial for the country’s economy’.Footnote 88 The fact that the committee was established as the Spanish Civil War was drawing to a close and more and more Republicans were fleeing abroad suggests that the government saw the refugee crisis in Europe as an opportunity for Colombia. López de Mesa implied as much in his correspondence with the education minister in July: ‘As you well know, Minister, in France there are a great number of Spanish refugees, amongst whom are many professors and teachers qualified to improve the education systems in this country, and who would happily come to undertake such a mission should it be entrusted to them. Professors of natural and exact sciences, languages, etc., which our provincial schools lack and who could be contracted on favourable terms.’Footnote 89 Various historians have examined the consequences of this policy for mid-twentieth century Colombian cultural and educational programmes, but the point here is that this was only one side of Colombian policy towards Spanish immigration.Footnote 90 Whilst López de Mesa actively sought intellectuals from Spain that he believed could contribute towards Colombia’s cultural development, his department considered the majority of Republican refugees undesirable and blocked them from entering the country.

Given that López de Mesa was foreign minister during this key period for immigration policy, he has often been considered the sole mastermind behind the restrictive laws. The fact that he was openly antisemitic and often referred to Republican refugees as anarchists does nothing to invalidate this view.Footnote 91 Santos, on the other hand, is seen as a proponent of Republican immigration because he was in contact with various refugees from his time in Paris and so, in many cases, was the person who facilitated their arrival. He also participated in many of their activities in Colombia after the end of the Spanish Civil War, particularly once he had stepped down as president. However, the documentary evidence suggests that López de Mesa and Santos actually shared very similar views on mass arrivals from Spain. Moreover, their stance was shaped by the much longer trend of successive Colombian governments limiting immigration which stretched back to the late nineteenth century.

In September 1938, after the new government began to tighten immigration restrictions, El Liberal reported that the decrees responded to Santos’s ‘express determination’ to limit the amount of ‘undesirable immigration’. The newspaper also claimed that the president himself ordered the confidential circular that prohibited consuls from issuing visas to individuals from specific nationalities.Footnote 92 Certainly, Santos seems to have taken a personal interest in ensuring new immigration laws were effectively communicated. On 24 September, he telegrammed Obregón informing him that he had issued Decree 1723 the previous day and explaining its provisions.Footnote 93 A month later, Santos asked the minister to ‘urgently and quickly’ order all consuls to ascertain how many tickets had already been sold to immigrants whose visas were issued before the decree and invalidate all those whose revocation would not open the government up to claims or complaints. He also requested that consuls send statistical, detailed reports with names and concrete information about all visas issued in the previous 20 months.Footnote 94

As the end of fighting in Spain appeared imminent, Santos increasingly turned his attention to the issue of Republican refugees. In February 1939, he once again cabled Obregón:

With respect to the requests from intellectuals to come to Colombia, we would need to study the cases individually. Some of them … have my respectful sympathy and could carry out great work in Colombia. I fear that Spain is entering into a period in which intellectuals will be persecuted … and we could benefit from the services of Spanish professors who, as Republicans, could not in all fairness be branded as Communists. Especially amongst the Basque and Catalan communities there are many spotless individuals, even from the religious point of view, who are persecuted only because of their liberalism and love for their respective regions. In any case, we will not resolve anything except for special cases that have been specifically studied, rejecting any possibility of immigration for militant revolutionaries who could cause dire problems here.Footnote 95

The president, whilst sensitive to some of the differences in the Republican camp, implicitly categorised the majority of refugees as ‘militant revolutionaries’ by reducing the instances of ‘spotless individuals’ to specific cases. Moreover, the telegram indicates that Santos was not only aware of restrictions against Spanish immigration but actively identified with them, suggesting he played a central role in their formulation.

Later that month, Santos sent another cable to Paris emphasising that:

We are deeply concerned about requests from Spaniards but my sincere sympathies for Republicans cannot prevent me from seeing all kinds of problems (we would have) if we allowed uncontrolled Spanish immigration … A penniless Spaniard relocating here would only cause resentment and I do not see where we could put him. For professionals of a different order and professors, we are prepared to study each case individually and see what we can do, on the basis that our laws severely prohibit any intervention in politics.Footnote 96

This last line was probably the president’s recognition of previous controversies surrounding the activities of certain individuals from Spain who were frequently accused of meddling in national affairs. It reveals how his concern for domestic convivencia (peaceful coexistence) which had heavily influenced his Spanish policy also overrode any sympathies he may have for Republican refugees. Ultimately, Santos did not want to allow individuals to enter the country who could then be used by Conservatives and Catholic groups to claim that the Liberal government was exposing the country to Communism. The president therefore played a key role in constructing a divide between the ‘undesirable’ Republican masses and ‘desirable’ individuals, even if his reasons for doing so were more practical than ideological.

Republican Agency in the Development of Immigration Policy

The duality of Colombian immigration policy offered a chance for potential immigrants to navigate the restrictions imposed upon them. Oftentimes, those best placed to do so were refugees who were already in Colombia and could petition the government on behalf of their friends and relatives. Twenty-one per cent of visa requests in the period covered by this article fell into this category.Footnote 97 Some exiles used their privileged position to recommend individuals. Fernando Martínez Dorrien, for instance, landed in Colombia in April 1938. He brought with him considerable capital with the view to setting up a publishing house in the country. Shortly after his arrival, Martínez opened Editorial Bolívar and, by November, he and his Colombian collaborators had published the first edition of Estampa magazine which would run until 1966.Footnote 98 His position gave him access to high-level Colombian officials, many of whom were also involved in the press industry.

On 17 February 1939, Martínez wrote to Santos recommending Ricardo Baeza who was in France with his wife and two children. He emphasised how Baeza’s knowledge of the arts would make him a valuable asset for Colombian universities and suggested that the president ‘contract Baeza as a general teacher, with a monthly salary of 200 pesos. His work as a journalist would allow him to better these conditions and make government aid more feasible’.Footnote 99 The appeal to Baeza’s value played into the government policy of only selecting Republican refugees who could contribute to Colombian society. It clearly worked: five days later, Santos personally sent a telegram to the Colombian legation in Paris authorising Obregón to issue visas for the family.Footnote 100 Baeza did not end up coming to Colombia, instead opting to travel to Buenos Aires, but his example shows how certain Republican refugees were able to leverage contacts within Colombia to obtain visas for their compatriots.

Most exiles in Colombia did not share Martínez’s privileged position, however. They therefore needed to prove their solvency to the Colombian government before inviting others to the country. The case of the Larrauri y Landaluce brothers is exemplary. Antonio and Felix arrived in Colombia in early 1938 having been invited by Spanish citizen Eugenio de Gamboa.Footnote 101 Over a year later, after establishing a farm in El Espinal, Tolima, they wrote to the MRREE requesting authorisation for their mother and three sisters to come to the country. Their father had died the previous year and ‘there being no other men in the family who can protect and look out for them … we find ourselves with the pressing need, in pursuance of our most sacred duties, to bring our elderly mother and unmarried sisters here to live with us’.Footnote 102 The emphasis on the age of their mother and the marital status of their sisters highlights the brothers’ awareness of the gendered nature of Colombian immigration law which, since late 1938 and as part of the attempt to further restrict immigration from Europe, only authorised requests from the elderly parents of individuals already in the country or their female and child dependents.Footnote 103 Yet this also meant that they had to prove that they were well established, honourable, law-abiding, beneficial to their local community and with sufficient resources to sustain themselves and their family. To that end, Felix and Antonio had to submit two references from Colombian citizens as well as a certificate from the local mayor. Only after the MRREE received all this documentation did it approve the visas on 5 May 1939.Footnote 104

As more refugees arrived in the country and requested visas for friends and family members abroad, the MRREE introduced even more stringent requirements. For example, on 7 April 1941 Julián Barbero López applied for visas for his wife and young daughter who were in Mexico. The MRREE initially rejected Barbero’s application on the basis that he ‘only just entered the country last October and neither his actions nor his solvency have been sufficiently proven’. He therefore reapplied a month later with references from José María España and Marino López Lucas – two other Republican refugees who had established in Colombia a biochemistry institute and a Spanish college respectively – and his request was finally granted on 27 May 1941.Footnote 105 That Barbero’s family were in Mexico reflected the changing patterns of Spanish immigration after the Spanish Civil War. The outbreak of the Second World War provoked new situations that made it more difficult for refugees to leave Europe, such as the Nazi occupation of France in May 1940, or find direct routes to Colombia, particularly during the Battle of the Caribbean. Visa requests from France thus fell to 54 per cent of total applications in 1940 and to 26 per cent the following year. Even those who had managed to flee the continent before these events began to reconsider their options as the focus switched from escaping persecution to building a future in exile. Consequently, after 1940, requests from the Americas and the Caribbean gradually outnumbered those from France.Footnote 106 The involvement of España and López Lucas in Barbero’s request also illuminates the networks that Republican exiles established within Colombia to facilitate the arrival of more refugees. These networks – whether within or outside of the country – also shaped Colombian immigration policy. As the October 1938 MRREE circular illustrated, the government responded to refugees’ attempts to find loopholes in existing legislation by implementing additional rules and requirements aimed at maintaining or strengthening immigration restrictions.

Not all Republican refugees had access to such networks and so some resorted to more drastic measures for entering Colombia. In July 1937, the customs officer at Barranquilla seaport, Enrique Gómez Latorre, complained to the MRREE about the ‘many cases of foreigners who enter the country without paying the necessary deposit by pretending to be “in transit” or “travelling agents” when in reality they are coming as immigrants’.Footnote 107 At least thirteen Republican refugees arrived in Colombia as tourists and later requested leave to remain in the country. One of these, Santiago Sentís Melendo who entered Colombia in May 1939, explained in his application for residency that the Colombian consul in Le Havre recommended he apply for a tourist visa given that he did not have sufficient funds to pay the immigration deposit.Footnote 108 Clearly, despite the restrictions against Spanish immigrants, particularly those without resources, some consular authorities were still sympathetic towards the plight of Republican refugees and helped them travel to Colombia. Generally, the MRREE took a lenient approach to Spaniards who entered the country under these conditions, eventually granting all of them leave to remain. However, in January 1940 the government did issue a decree which made it harder for foreigners to obtain tourist visas.Footnote 109

Others who attempted to evade immigration restrictions were less lucky. Returning to the three Republicans who opened this article, they were part of a larger group of nine refugees who had been imprisoned in the Panama Canal zone after trying to enter Panama illegally. The group were being sent back to the Dominican Republic, a country from which they had attempted to escape the hunger and hardship that many exiles from Spain faced after the dictatorship of Rafael Trujillo abandoned them to their fate. On 29 April 1940, the Dutch steamer carrying the nine stowaways docked in Barranquilla and four of the men attempted to negotiate with port authorities so that they could remain in Colombia. Unsurprisingly, given the construction of the ‘undesirable immigrant’ explored here, their request was refused and so, as the vessel pulled out of the harbour, the four men jumped overboard and attempted to swim to shore. We know the fate of three of these individuals; the fourth, Francisco Perez Arecho, reportedly survived and remained under the protection of unknown persons who sheltered him from the police. The story of these four men therefore emphasises what a simple study of immigration policy can often obscure: the Republican refugees were individuals who suffered greatly in the aftermath of the Spanish Civil War. Yet, as governments in Colombia and elsewhere sought to impose restrictions on their futures, they continued to struggle, sometimes risking their lives, against the barriers that had been constructed around them. Their actions, in turn, helped shape these policies as authorities scrambled to fill the gaps in immigration laws.

Conclusion

Renán Silva argued that, whilst Republican exiles’ contribution to Colombian society was significant relative to their number, the government’s restrictive policy on immigration from Spain limited the possibility of greater impact.Footnote 110 This article has shown how the co-constitution of ‘red Republicans’ and ‘undesirable immigrants’ enabled the Liberal administrations of López and Santos to stem the flow of Spanish immigration as a result of the Spanish Civil War. However, at the same time as it sought to exclude the majority of Republican refugees from entering Colombia, Santos’ government in particular saw the European refugee crisis of the late 1930s as an opportunity to bring over certain groups and individuals that they considered beneficial for Colombia’s cultural and economic development. In that sense, the contribution of Republican exiles to Colombia in the 1930s and 1940s was conditioned by widespread anxieties about the types of immigrants that could be assimilated into Colombian society as well as by officials’ understandings of their country’s requirements.

This invites us to reflect on the significance of Republican refugees for Colombian immigration policy. Even though emigration from Spain during the 1930s and 1940s was relatively low when compared to other Latin American countries, the fact that the Spanish Civil War coincided with the introduction of Colombia’s first twentieth-century Liberal regime means that the subsequent refugee crisis had a disproportionate impact on immigration policy in that country. The successive governments’ stance on immigration emerged at the intersection of various, racialised discourses which helped frame ideas about who could best contribute to the ‘modern’ nation they wanted to build. Such ideas contributed to the categorisation of Republican refugees as ‘undesirable’ immigrants, at the same time as concerns about a mass influx from Spain catalysed a powerful, racialised language that defined Communist individuals as a threat (‘el peligro rojo’, ‘the red danger’) to the national ‘race’. These ideas developed from earlier Conservative legislation which sought to define ‘ideal’ immigration in both racial and social terms, thus exposing the continuities in racialised notions of citizenship. Such continuities point to the tensions that existed between the Liberal governments’ immigration policies and their domestic cultural programme which they claimed marked a new era of popular participation in political life.

An examination of the ways in which the two governments from 1936 to 1942 sought to both control and exploit immigration from Spain as a way to further their country’s progress resituates Colombia within a hemispheric history of immigration and national identity. Indeed, both official policy and public debate on immigration were framed in a regional context. However, in a break from nineteenth-century regional ideas of white migration as a source of development, the political polarisation of the mid-twentieth century exemplified most clearly for Colombians in the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War meant that ethnic origin was no longer the most important defining characteristic of the ‘desirable’ immigrant. Instead, race became entangled with ideology in such a manner that certain Spaniards were no longer considered assimilable in a Colombian and broader Latin American context and were therefore blocked from entering the country.

The Colombian case also shows how the different European refugee crises in the late 1930s and early 1940s cannot be considered separately. As an assimilationist discourse developed in the context of heightened interwar racial and ideological tensions, Colombian leaders, journalists and the public viewed both Jewish and Republican immigrants as potentially harmful elements. Accordingly, laws put in place to block the arrival of Jews were also used to prevent Republicans from coming to the country. Future research into both phenomena could benefit from analysing this interrelationship to understand how the experiences of one group also helped shape those of the other. This is not limited to structural questions of policy. Evidence suggests that many refugees from Central Europe and Spain travelled together within and eventually out of Europe. An examination of their interactions could shed new light on refugee agency as well as interrefugee solidarity and conflict during the mid-twentieth century.

Acknowledgements

I want to thank Tanya Harmer and Anna Cant for their thorough engagement with earlier drafts. I am also grateful to the members of the Americas in the World cluster at LSE’s Department of International History for their suggestions on how to improve the manuscript. Finally, thank you to the two anonymous reviewers whose generous feedback helped make this a better article. The research for this article was carried out with the support of the London School of Economics and the Universidad del Rosario in Bogotá.