Introduction

According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), crop productivity and the capacity to guarantee food security fall significantly below global benchmarks (FAO, 2020). Projections suggest that this situation may worsen due to factors such as population growth, climate change, declining soil fertility, and environmental degradation. Both the FAO (2020) and the World Bank (2014) indicate a recent decline in global agricultural production, posing a potential threat to sustaining food supply for the growing global population (FAO, 2020). Given these challenges, there is an urgent need for strategies that foster the sustainable intensification of agricultural production. Researchers generally attribute the low agricultural productivity to land and soil fertility degradation, particularly in developing nations (Tully et al., Reference Tully, Sullivan, Weil and Sanchez2015).

Soil fertility is of utmost importance in crop production as it directly affects the availability of essential plant nutrients. In intensive and continuous crop production systems, there is a significant decline in soil fertility due to high rates of soil degradation. Continued farming on the same piece of land, coupled with poor land management and the absence of proper administration of necessary minerals and nutrients, leads to declines in soil fertility and productivity. The structure and composition of the soil are compromised, and soil organisms are destroyed, especially when practices like slash and burn are employed for land preparation. Additionally, the improper application of insecticides and fungicides, along with inadequate timing and administration of fertilizers, as well as failure to adhere to recommended cultural practices such as cover cropping, result in nutrient leaching when it rains. These factors contribute to soil infertility and reduced productivity, ultimately causing a decline in overall agricultural production (Tully et al., Reference Tully, Sullivan, Weil and Sanchez2015; World Bank, 2014; FAO, 2020). Meanwhile, it is neither biologically friendly, economically efficient, nor environmentally sustainable to consistently rely on large quantities of inorganic fertilizers as a solution to improving soil fertility (Jaja and Barber, Reference Jaja and Barber2017).

The case of tomato production in Ghana is no exception to yield decline (Melomey et al., Reference Melomey, Ayenan, Marechera, Abu, Danquah, Tarus and Danquah2022). Tomato (Solanum lycopersicon) remains the foremost significant vegetable in the world due to its increasing dietary value, widespread production as well as serving as a model plant for research (World Bank, 2014). Ghana has set a goal to enhance its food production in order to meet the needs of its expanding population. However, the country intends to shift away from traditional farming practices, opting instead for easily comprehensible methods that currently incorporate environmentally friendly technologies. The reason for this shift is that traditional agricultural practices deplete soil nutrients, resulting in unproductive farming systems (Moswetsi et al., Reference Moswetsi, Fanadzo and Ncube2017). As a result, Ghana is exploring the use of small amounts of mineral fertilizers alongside the use of improved crop varieties and sustainable farming systems, as this combination has the potential to increase crop yields by enhancing the efficiency of nutrient utilization by plants (Schütz et al., Reference Schütz, Gattinger, Meier, Müller, Boller, Mäder and Mathimaran2018).

Integrated Soil Fertility Management (ISFM) refers to a holistic approach to managing soil fertility that combines a variety of techniques and practices to improve soil health and enhance agricultural productivity, particularly in smallholder farming systems. ISFM integrates both traditional and modern methods, focusing on optimizing soil nutrient levels while also improving sustainability, minimizing environmental degradation, and boosting crop yields (Vanlauwe et al., Reference Vanlauwe, Bationo, Chianu, Giller, Merckx, Mokwunye, Ohiokpehai, Pypers, Tabo, Shepherd and Smaling2010; Horner and Wollni, Reference Hörner and Wollni2021; World Bank, 2014; FAO, 2020). It encompasses the development of nutrient management technologies to ensure desired supply of organic and inorganic inputs (Vanlauwe and Zingore, Reference Vanlauwe and Zingore2011; Mugwe et al., Reference Mugwe, Ngetich and Otieno2019). In the context of this research, ISFM refers to the simultaneous use of organic and inorganic fertilizers by smallholder tomato farmers. The overarching goal of ISFM is to boost soil fertility, mitigate land degradation, and enhance agricultural practices for the overall betterment of farm households and the economy. Many countries, including Ethiopia, have successfully employed ISFM to revitalize agricultural production in crops such as maize, wheat, and teff, leading to increased productivity and improved farmer welfare (Horner and Wollni, Reference Hörner and Wollni2021). ISFM contributes to advancements in agronomy, line seeding, timely weeding, and precise administration of inputs, thereby addressing issues of inconsistent crop yield and quality. Efficient coordination and management of activities facilitated by ISFM techniques enable smallholders to meet the growing demand, enhancing competitiveness, income, and market share extension, potentially leading to exports and improved standard of living.

The excessive use of inorganic fertilizers has resulted in soil, air, and water pollution, causing environmental quality and biodiversity loss, particularly in developing countries like Ghana. In such regions, agrochemicals pose hazards to human and livestock health. To tackle these challenges and ensure sustainable food production, a balanced use of organic and inorganic fertilizers is recommended. Organic fertilizers contribute to soil nutrient enhancement, plant growth, and biodiversity. Integrated nutrient management systems are therefore crucial for maintaining soil quality and achieving high yields. Although ISFM has been widely promoted in Africa to enhance crop yields and livelihoods, limited information exists on its impact on yields and household welfare (Danso-Abbeam and Baiyegunhi, Reference Danso-Abbeam and Baiyegunhi2017).

Tomato production is a key economic activity in rural Ghana, yet low yields and post-harvest losses are prevalent due to poor soil fertility from land degradation. Despite these challenges, farmers often neglect soil fertility management, resulting in low incomes and poor welfare. While ISFM adoption is proposed as a solution, its impact remains insufficiently assessed (Lambrecht et al., Reference Lambrecht, Vanlauwe and Maertens2016; Vanlauwe et al., Reference Vanlauwe, Hungria, Kanampiu and Giller2019). This study therefore seeks to investigate the impact of ISFM on the welfare of smallholder tomato farmers using a rigorous inverse probability weighted regression adjustment (IPWRA) approach. Three main questions guide the research, viz. (1) What factors influence the adoption of ISFM practices in tomato production? (2) What factors influence the welfare of adopters and non-adopters of ISFM practices? and (3) What is the impact of adoption of ISFM practices on the welfare of smallholder tomato farmers?

This study contributes to the existing literature on ISFM practices by expanding knowledge on ISFM adoption and its impact. The expected outcomes will influence stakeholder decisions and attitudes toward incorporating ISFM in tomato cultivation, ultimately improving farm productivity, income, and food security. The subsequent sections of the paper include a brief literature review, research methodology, results and discussions, as well as conclusions and policy implications.

Literature review

There is no debate about the role of agricultural innovations in increasing overall farm income. ISFM is one of such innovations. Studies have been conducted to explore effective strategies for the management of soil fertility in Ghana and other countries in SSA, aiming to prevent the risks associated with soil fertility depletion. Danso-Abbeam et al. (2017) examined the complementary nature of soil fertility-enhancing inputs and their impact on integrated soil nutrient management techniques at the farm level. The study revealed that certain interventions designed to improve soil fertility can have spillover effects on other approaches, highlighting the synergistic relationship between different methods of soil fertility management. According to Vanlauwe et al. (Reference Vanlauwe, Hungria, Kanampiu and Giller2019), an environmentally friendly and profitable method for increasing crop productivity is ISFM. According to the study, ISFM helps eradicate rural poverty and the degradation of natural resources in SSA. Lambrecht et al. (Reference Lambrecht, Vanlauwe and Maertens2016) investigated the implementation of ISFM practices on farms, paying special attention to the interconnections among the various components of ISFM. The findings were that the level of soil fertility serves as a motivating factor for adopting ISFM, although the socioeconomic characteristics of households also play a significant role. Sennuga et al. (Reference Sennuga, Fadiji and Thaddeus2020) investigated adoption of improved agricultural management activities and farmer characteristics using Spearman rank influence. The results were that age, gender, educational level, and farming experience positively and significantly influenced the adoption of integrated soil management, aligning with findings in adoption studies like Keelan et al. (Reference Keelan, Thorne, Flanagan, Newman and Mullins2009) and Mwangi and Kariuki (Reference Mwangi and Kariuki2015), which emphasized the impact of farmers’ socioeconomic characteristics on technology adoption.

Age emerges as a crucial factor in smallholders’ adoption decisions, as highlighted by Asante et al. (Reference Asante, Etuah, Faisal, Mensah, Prah, Mensah and Aidoo2023). Younger farmers, identified as more innovative and flexible, tend to explore new approaches and cutting-edge solutions to climatic and economic challenges (Amsalu and De Graaff, Reference Amsalu and De Graaff2007). Additionally, Danso-Abbeam et al. (Reference Danso-Abbeam, Ehiakpor and Aidoo2018) reported a positive correlation between age and the adoption of Integrated Pest Management (IPM), attributing it to older farmers’ greater experience and accumulated physical capital. Gender was found to significantly influence the adoption of ISFM, with male farmers more likely to embrace modern agricultural methods than their female counterparts (Kassie et al., Reference Kassie, Teklewold, Jaleta, Marenya and Erenstein2015). Sennuga et al. (Reference Sennuga, Fadiji and Thaddeus2020) also reported that there exists a relationship between educational level and ISFM adoption, supported by the expectation that more knowledgeable farmers would adopt improved management practices. Other previous studies (Mwangi and Kariuki, Reference Mwangi and Kariuki2015; Caswell et al., Reference Caswell, Chelba and Grangier2019) have also established a connection between education and farmers’ favorable attitudes toward new agricultural management, emphasizing the role of educated individuals in accepting information and management-intensive practices. In addition, Deressa et al. (Reference Deressa, Hassan and Ringler2011) reported that the participation of educated individuals in agriculture fosters a positive attitude toward new agricultural management. Moreover, Ali et al. (Reference Ali, Man and Muharam2019) emphasized the positive association between higher education, larger households, and the adoption of new management practices due to increased exposure to knowledge and labor resources. Essentially, formal education enhances individuals’ capability to acquire and apply new information, increasing the probability of adopting new technologies. Furthermore, Danso-Abbeam and Baiyegunhi (Reference Danso-Abbeam and Baiyegunhi2017) highlighted the positive impact of education on the adoption of IPM among smallholder farmers in Ghana, emphasizing and underscoring the role of education in enabling farmers to comprehend information on fertilizer labels and also follow instructions for machinery operation. Finally, Ansong Omari et al. (Reference Ansong Omari, Bellingrath-Kimura, Sarkodee Addo, Oikawa and Fujii2018) contributed insights into perceptions of organic residue management, soil health indicators, and crop production patterns of farmers.

Despite some studies focusing on ISFM adoption, determinants and its impacts, there are still gaps in understanding the factors influencing the welfare of adopters and non-adopters of ISFM practices as well as the impact of ISFM on smallholder welfare as few studies (Horner and Wollni, Reference Hörner and Wollni2021; Jabbar et al., Reference Jabbar, Liu, Wang, Zhang, Wu and Peng2022; Martey et al., Reference Martey, Etwire, Kuwornu and Suraj2024) have attempted to provide recommendations aimed at bridging these gaps. This is so, particularly in the context of vegetable production. The present study aims to contribute to helping to fill these gaps by examining the impact of ISFM on smallholder welfare in the context of Ghana’s tomato production.

Methodology

Data

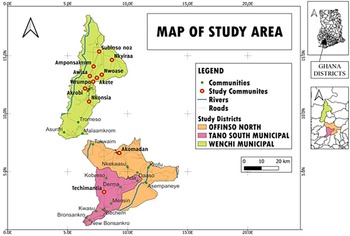

The study was conducted in three towns and their environs located in three districts/municipalities, viz. Akumadan (Offinso North district), Wenchi (Wenchi municipality) and Techiman Tia (Tano South municipality). Akumadan serves as the administrative capital of Offinso North, a district situated in the Ashanti Region of Ghana, with an approximate population of 20,000 residents (Ghana Statistical Service, 2021). The Akumadan Township has gained prominence for its robust engagement in agricultural activities. The surrounding areas of Akumadan are noted for intensive vegetable cultivation, predominantly employing mixed cropping methods. Akumadan is known for its intensive production of tomatoes in commercial quantities, making it the leading producer of tomatoes in Ghana. Although its soils are suitable for various food crops, tomatoes dominate the agricultural landscape, with over 90 percent of inhabitants above 18 years engaged in tomato farming, and tomato cultivation spanning the entire year, in four sub-seasons (Ntow, Reference Ntow2001; Ghana Statistical Service, 2021). The Offinso North district experiences a precipitation pattern of 150 rainy days or more annually, with an average rainfall of about 1400 mm. To counter dry spells, Akumadan is equipped with a dam that facilitates irrigation for some of the adjacent farmlands. Notably, under the leadership of President Akuffo Addo, the government recently inaugurated a Greenhouse project in Akumadan. This initiative aims to provide training in Agriculture Technology to young individuals, reflecting a commitment to advancing agricultural practices in the district.

The Wenchi municipality is one of the twelve districts within the Bono Region of Ghana. According to the 2021 National Population and Housing Census, the estimated population of the Wenchi municipality is 124,758 (Ghana Statistical Service, 2021). The district predominantly features savannah ochrosols, occasionally interspersed with lithosols. Characterized by predominantly low-lying terrain, the area’s soils are primarily sandy loam, with loamy soils prevalent in the valleys. These nutrient-rich soils are conducive to cultivating crops such as maize, yams, cocoyam, and tomatoes. Wenchi municipality is known for its tomato production, with this activity dominating agricultural activities in the municipality. The municipality covers a 3,494 km2 land area. The proximity of Wenchi to Techiman, a significant national market, presents numerous advantages for agricultural production and agro-processing. Farmers in particular, should be sensitized and supported to leverage this strategic opportunity. Notably, the government recently officially reopened the Wenchi Tomato Processing Factory, emphasizing its commitment to revitalizing this economic venture. The factory specializes in processing and packaging various vegetables, prominently tomatoes, garden-eggs, okra, and other fruits, playing a pivotal role in Wenchi’s economic landscape since the 1960s (Ministry of Food and Agriculture (MoFA) & International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) 2020).

Techiman Tia, situated in the Tano South municipality in the Ahafo Region of Ghana, is a town located approximately 14 km away from Bechem, the municipal capital. The economic landscape of Techiman Tia is predominantly driven by agricultural production, establishing it as one of Ghana’s tomato-producing towns, supplying tomatoes to various parts of the country. Figure 1 presents a map of the study area.

Figure 1. Map of the study districts. Source: Ghana Statistical Service, 2022.

The population for this study comprises all the tomato farmers in Akumadan (3245 tomato farmers), Techiman-Tia (300 tomato farmers), and Wenchi (281 tomato farmers) (MOFA, 2021; GSS, 2021). Out of the aforementioned population, a sample of 380 tomato farmers was selected for the study. The sample size determination formula proposed by Yamane (1967) was employed to ascertain the required sample size and specified as:

where

![]() $n$

is the sample size,

$n$

is the sample size,

![]() $N$

is the population of tomato farmers (3826), and

$N$

is the population of tomato farmers (3826), and

![]() $e$

is the margin of error (5%).

$e$

is the margin of error (5%).

A multi-stage sampling technique was employed to select the respondents. In the first stage, purposive sampling was used to sample Akumadan, Techiman-Tia, Wenchi and their environs as the study area because of their predominance in tomato production. The second stage also involved purposively selecting communities within and around each town based on their level of tomato production. These included Akomadan, Nkekaasu, Daaso, and Asempaneye for Akumadan, Tachimantia, Kobreso, and Derma for Tachimantia and Awisa, Nkonsia, and Akrobi for Wenchi. In the third and final stage, lists of tomato farmers from these communities were obtained from extension officers operating in the communities. Individual tomato farmers were then randomly selected, resulting in a sample size of 380 farmers, proportionally allocated as 188 from Akumadan (47 from each community), 114 from Tachimantia (38 from each community), and 78 from Wenchi (26 from each community). This was to capture a balanced representation across the key study areas, viz. Akumadan, Tachimantia, and Wenchi to ensure that the findings reflect insights not just from dominant Akumadan but also from the other producing areas. Data was gathered using a semi-structured questionnaire covering farmers’ engagement in ISFM and inorganic tomato farming. The questionnaire was pre-tested with five (5) tomato farmers from each of the study areas. Farmers were visited in their homes and on their farms during the data collection.

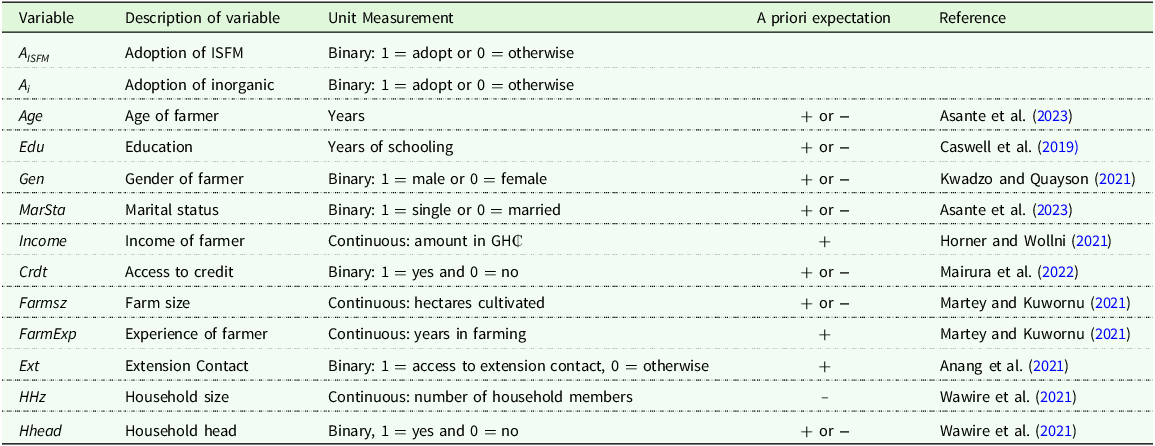

Tables 1 and 2 present descriptions and measurements of variables employed in the study as well as their descriptive statistics. These variables include

![]() ${A_{ISFM}}$

(adoption of ISFM),

${A_{ISFM}}$

(adoption of ISFM),

![]() ${A_i}$

(adoption of inorganic),

${A_i}$

(adoption of inorganic),

![]() $Age$

(Age of farmer),

$Age$

(Age of farmer),

![]() $Edu$

(Education),

$Edu$

(Education),

![]() $Gen$

(gender of farmer),

$Gen$

(gender of farmer),

![]() $MarSta$

(Marital status of farmer),

$MarSta$

(Marital status of farmer),

![]() $Income$

(income of farmer),

$Income$

(income of farmer),

![]() $Crdt$

(access to credit),

$Crdt$

(access to credit),

![]() $Farmsz$

(farm size),

$Farmsz$

(farm size),

![]() $FarmExp$

(experience of farmer),

$FarmExp$

(experience of farmer),

![]() $Ext$

(extension contact),

$Ext$

(extension contact),

![]() $HHz$

(household size), and

$HHz$

(household size), and

![]() $Hhead$

(household head). Each variable is described in terms of its unit of measurement and the a priori expectation of its influence on the outcome variables.

$Hhead$

(household head). Each variable is described in terms of its unit of measurement and the a priori expectation of its influence on the outcome variables.

Table 1. Description of explanatory and explained variables

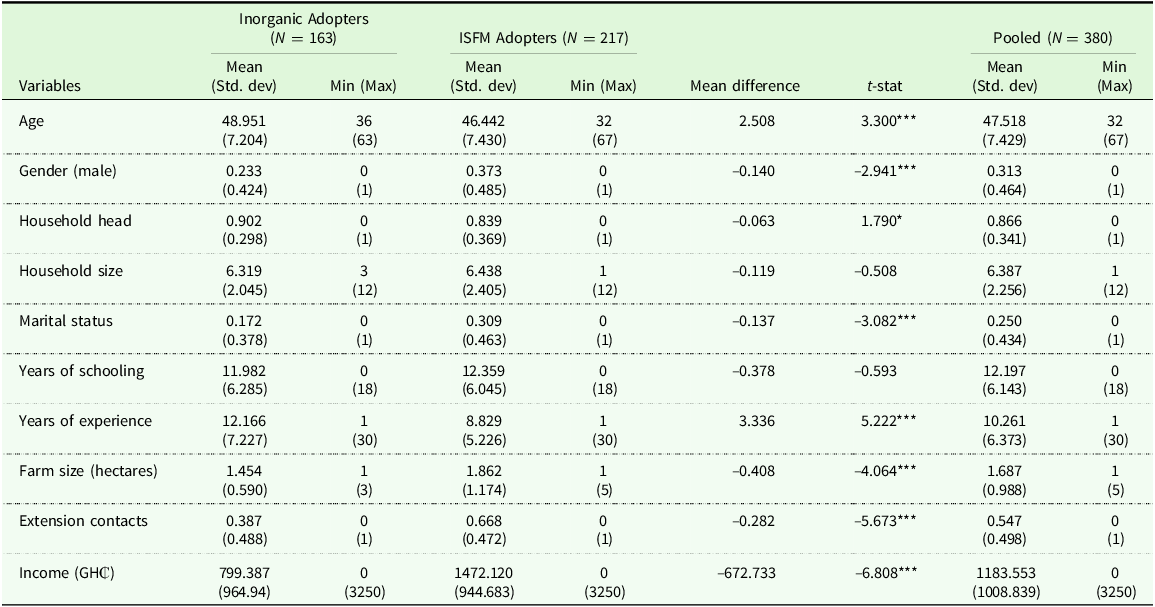

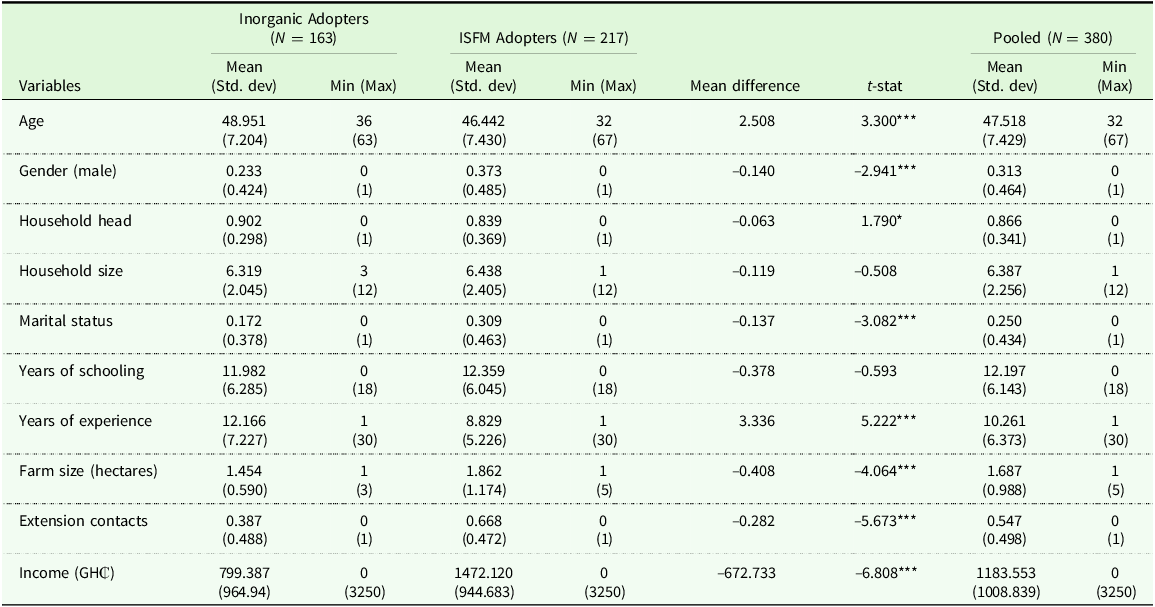

Table 2. Summary statistics of characteristics of respondents

Table 2 provides context for tomato farmers’ sociodemographic characteristics. The sampled tomato producers’ age, gender, education, marital status, household size, years of experience, and formal education are included. Out of the 380 respondents surveyed, 217 (57.1%) were adopters of ISFM, while 163 (42.9%) were adopters of conventional inorganic practices. Hörner and Wollni (Reference Hörner and Wollni2021) also found a higher adoption rate of 64.66% among farmers in Ethiopia, indicating substantial preference for ISFM practices in different African geographic contexts. It was observed that the gender distribution among conventional inorganic production system adopters was skewed toward female farmers, who comprised 76.3% of the respondents in tomato production, contrary to some previous findings (Owolade & Kayode, Reference Owolade and Kayode2012; Mensah, Reference Mensah2020). The finding comes from the growing role of women in agriculture, especially in tomato cultivation in Ghana.

ISFM users had a mean age of 46.4 years, while conventional inorganic fertilizer users were 58.5 years old. According to Hörner and Wollni (Reference Hörner and Wollni2021), in Ethiopia, young farmers show a greater willingness to adopt modern farming techniques, including ISFM. Young growers could have a greater eagerness to welcome contemporary practices and are likely to advance in their farming techniques. More ISFM adopters were married (30.9%), as opposed to the 17.2% married conventional inorganic fertilizer users. Because of the quantity and quality of resources married farmers have, they have more resources at their disposal as compared to single farmers. The study also revealed that married farmers can attract labor within families, and a stable income is helpful in the implementation of new farming practices, including ISFM. Among the ISFM adopters, their number of years of farming experience was 9 years, while that of the conventional inorganic producers was 12 years. This finding however contradicts the findings of Petros et al. (Reference Petros, Abay, Desta and O’Brien2018) and Ali et al. (Reference Ali, Awuni and Danso-Abbeam2018), that reported that experienced and informed farmers employ ISFM. A notable difference exists as more ISFM users (66.8%) utilized extension services more than those adopting conventional inorganic practices (38.7%), showing how crucial those services are for ISFM growth. This finding is consistent with the findings of Hörner and Wollni (Reference Hörner and Wollni2021), indicating substantial differences in access to extension services among ISFM users and conventional inorganic producers. These services are vital for helping farmers learn about the advantages and application of ISFM, thereby encouraging its increased use and adoption. No significant difference was however identified in household size and educational level among ISFM adopters and conventional organic farmers. That is, the education and household composition were remarkably similar for the two groups.

Conceptual framework

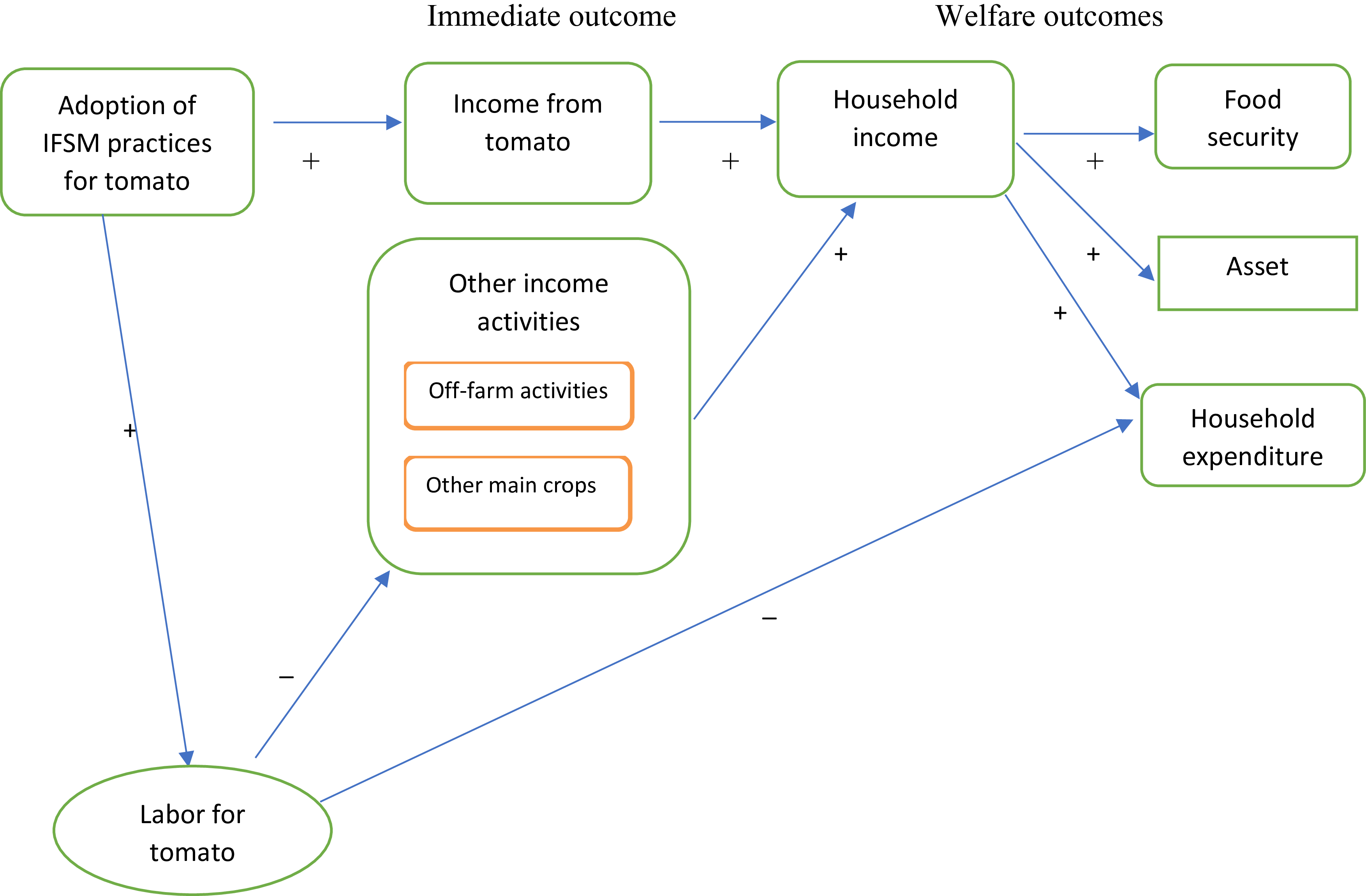

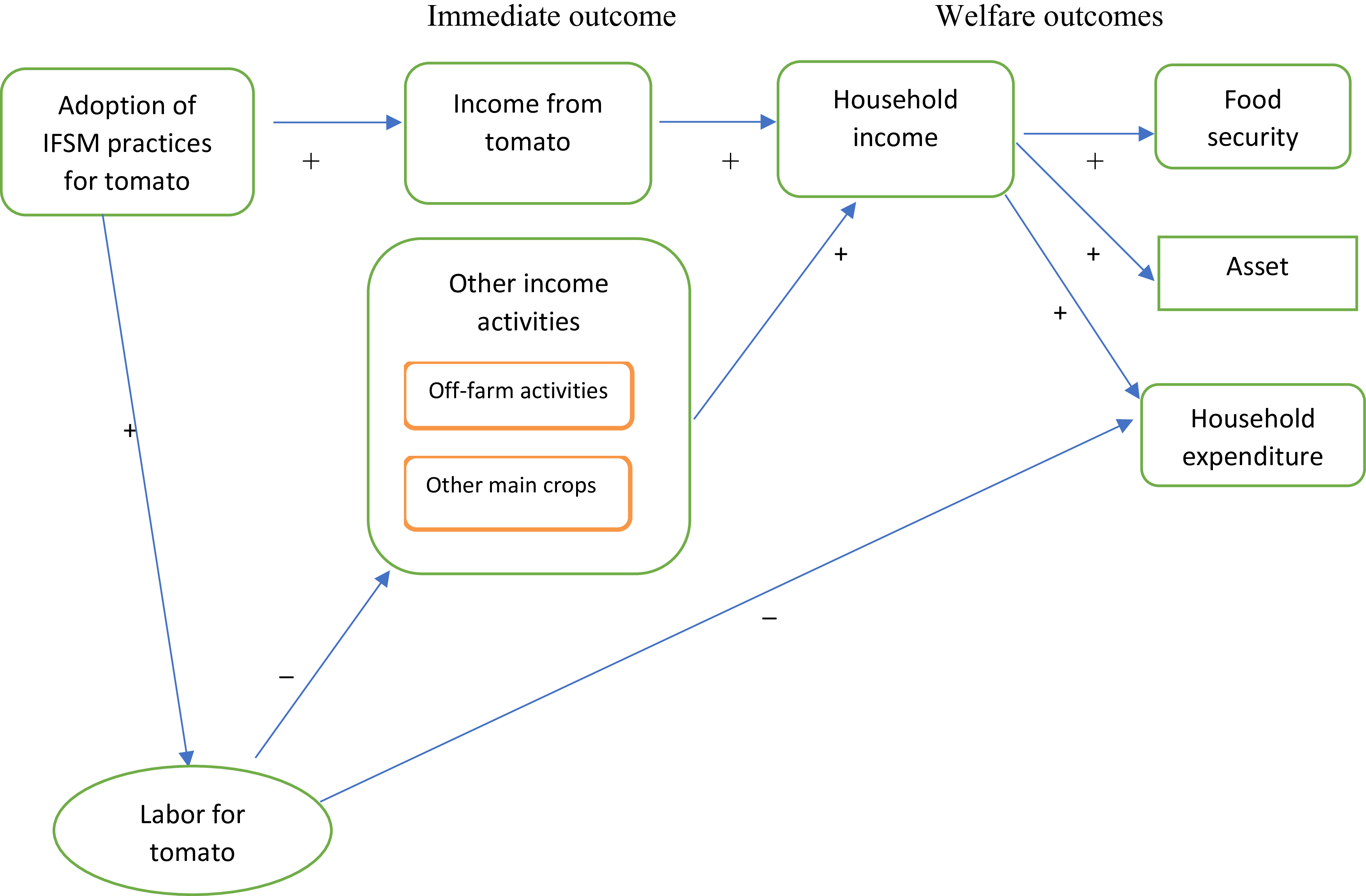

The conceptual framework (depicted in Figure 2) delineates the proposed correlation between ISFM adoption by tomatoes and their welfare outcomes. ISFM enhances soil fertility and agricultural productivity by introducing improved agricultural practices. In developing countries, rural households’ reliant on agriculture as their primary source of livelihood are expected to gain from ISFM by experiencing higher yields and improved welfare. ISFM adoption typically involves acquiring inputs like seeds and fertilizers (both organic and inorganic), as well as additional labor input. Therefore, smallholder welfare will be improved as long as the revenues gained surpass the supplementary production costs.

Figure 2. Conceptual framework of the study. Note: + denotes positive association, - denotes negative association.

Rural households typically engage in various income-generating activities that collectively contribute to their overall welfare (Barrett et al., Reference Barrett, Reardon and Webb2001). The implementation of ISFM practices on specific crops, leading to increased income from those crops, is expected to have a positive correlation with the total income of the household and consequently their welfare. However, the adoption of ISFM may also result in an increased demand for labor, given the labor and time-intensive nature of preparing and applying inputs and implementing enhanced management activities. In rural areas of SSA with imperfect labor markets, the adoption of ISFM technologies could potentially redirect labor away from other on- and off-farm income operations, thereby potentially having adverse effects on the total household income (Dillon and Barret, Reference Dillon and Barrett2017). The success of the relationship between ISFM adoption and smallholder welfare depends on whether the income gains from enhanced crop yields outweigh the potential negative effects on income due to labor reallocation toward ISFM activities.

In addition to income, various indicators such as food security, household expenditure, and assets, are also considered as proxies for assessing household welfare. An increase in income is expected to enhance welfare through alleviation of consumption constraints. Also, with higher incomes, households can allocate more resources to food consumption, thus improving food security. While the enhanced productivity of tomatoes can directly contribute to increased food availability within the household, our primary focus is on income as a critical factor connecting ISFM and food security. This perspective is in line with previous studies emphasizing the substantial role of market-sourced and processed foods in the dietary intake of farm families in SSA (Harrison et al., Reference Harrison, Funk and Peterson2019; Wichern et al., Reference Wichern, van Wijk, Descheemaeker, Frelat, van Asten and Giller2017; Prah et al., Reference Prah, Asante, Aidoo, Mensah and Nimoh2023). Moreover, income plays similarly pivotal roles in driving household food security (Mutea et al., Reference Mutea, Bottazzi, Jacobi, Kiteme, Speranza and Rist2019).

Analytical framework

Descriptive statistics

Descriptive statistics such as frequencies, percentages, means, and standard deviations were used to describe the data and analyze the socioeconomic characteristics of the respondents. The data analysis employed both the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS v21) and STATA software.

Estimation of welfare indicators

In this study, a number of indicators were used as indicators of welfare. These include net income in Ghana cedis (GH₵), household food security estimated using the Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS), monetary value of assets, and household expenditure. The income of both ISFM adopters and non-adopters was determined using income statement, with net profit margins representing their respective incomes. According to the Shaw (Reference Shaw2007), food security is defined as the condition in which “all individuals consistently have the physical and economic means to acquire adequate food to meet their dietary requirements, as well as ensuring a healthy and productive life.” In this research, the food security status of tomato farming households within the four weeks prior to the study was measured using the HFIAS (Pandey and Bardsley, Reference Pandey and Bardsley2019). In analyzing the HFIAS, the food security scores of tomato farmers who adopted ISFM and those who did not adopted ISFM were generated. To assess food security, the standard HFIAS approach developed by USAID was employed and followed (Coates et al., Reference Coates, Swindale and Bilinsky2007). In this approach, respondents were asked a series of nine standardized questions to assess the severity of food insecurity experienced within the 30 days prior to data collection. Each response was assigned a numerical code on a scale of 0 to 3, with 0 denoting “No,” 1 denoting “rarely” (occurring once or twice in the past 4 weeks), 2 denoting “sometimes” (occurring three to ten times in the past 4 weeks), and 3 denoting “often” (occurring more than ten times in the past four weeks). The total score, a continuous measure, was derived by summing the frequencies of the various food insecurity conditions, that ranged from 0 to 27. Higher scores indicated greater household food insecurity, while lower scores indicated the opposite (food security). Additionally, the HFIAS allowed for a categorical classification of households as food secure, mildly food secure, moderately food insecure, or severely food insecure based on the scores computed. From the average scores, the minimum was 0 and the maximum was 16 for adopters. For the non-adopters, the minimum was 0 and the maximum was 18. Using the HFIAS extremes, we categorize the tomato farmers according to the following scale, viz. 0–4 = Food secure, 5–7 = Mildly food secure, 8–10 = Moderately food insecure and 11–27 = Severely food insecure (Coates et al., Reference Coates, Swindale and Bilinsky2007).

The food security index for both adopters and non-adopters of ISFM are compared in order to know those that are more food secured (FAO, 1996; Pandey and Bardsley, Reference Pandey and Bardsley2019). The assets that both the adopters and non-adopters of ISFM have acquired were identified, and their monetary values were determined through assets valuation. Assets in monetary value was given by Initial Value of Asset less Depreciation. Finally, household expenditure for both adopters and non-adopters of ISFM were estimated using their expenditures on food, education, rent, utilities, and other household items.

Inverse Probability Weighting Regression Adjustment

The research utilized the doubly robust Inverse Probability Weighting Regression Adjustment (IPWRA) method introduced by Wooldridge (Reference Wooldridge2010), to assess the impact of ISFM on the welfare of smallholder tomato farmers. This approach aimed to address issues related to self-selection. The IPWRA method combines inverse probability weighting (IPW) and regression adjustment (RA). The IPW helps to understand the adoption decision-making process, while RA focuses on the outcome equation to effectively address selection bias and uncontrolled attributes in both stages. We specified the probability of adopting ISFM using IPW as:

where

![]() $ISF{M_i}$

= ISFM adoption status,

$ISF{M_i}$

= ISFM adoption status,

![]() $W$

= set of covariates (household, farm level, and institutional factors) and

$W$

= set of covariates (household, farm level, and institutional factors) and

![]() $F\{ .$

}=cumulative distribution function. The RA technique involves fitting adopters and non-adopters’ distinct linear regression models and predicting covariate-specific outcomes based on their adoption status. We therefore compute the mean differences of predicted outcomes

$F\{ .$

}=cumulative distribution function. The RA technique involves fitting adopters and non-adopters’ distinct linear regression models and predicting covariate-specific outcomes based on their adoption status. We therefore compute the mean differences of predicted outcomes

![]() $\left( {ISF{M^A}} \right)$

for adopters and non-adopters. Following Manda et al. (Reference Manda, Gardebroek, Kuntashula and Alene2018), Wongnaa et al. (Reference Wongnaa, Abudu, Abdul-Rahaman, Akey and Prah2023), Wooldridge (Reference Wooldridge2010), and Yeboah et al. (Reference Yeboah, Balcombe, Asante, Prah and Aidoo2023), the

$\left( {ISF{M^A}} \right)$

for adopters and non-adopters. Following Manda et al. (Reference Manda, Gardebroek, Kuntashula and Alene2018), Wongnaa et al. (Reference Wongnaa, Abudu, Abdul-Rahaman, Akey and Prah2023), Wooldridge (Reference Wooldridge2010), and Yeboah et al. (Reference Yeboah, Balcombe, Asante, Prah and Aidoo2023), the

![]() $ISF{M^A}$

of the

$ISF{M^A}$

of the

![]() $RA$

model is specified as:

$RA$

model is specified as:

$$ISFM_{RA}^A = N_A^{ - 1}{\sum_{i = 1}^{N}}{H_i}\left( {{r_A}\left( {W,{\gamma _A}} \right) - {r_N}\left( {W,{\gamma _{NA}}} \right)} \right)$$

$$ISFM_{RA}^A = N_A^{ - 1}{\sum_{i = 1}^{N}}{H_i}\left( {{r_A}\left( {W,{\gamma _A}} \right) - {r_N}\left( {W,{\gamma _{NA}}} \right)} \right)$$

where

![]() ${N_A}$

is the number of adopters,

${N_A}$

is the number of adopters,

![]() ${r_i}\left( W \right)$

represents adopters

${r_i}\left( W \right)$

represents adopters

![]() $\left( A \right)$

and non-adopters

$\left( A \right)$

and non-adopters

![]() $\left( {NA} \right)$

regression models, and

$\left( {NA} \right)$

regression models, and

![]() ${\gamma _i}$

are coefficients to be estimated. The IPWRA estimator is specified as:

${\gamma _i}$

are coefficients to be estimated. The IPWRA estimator is specified as:

$$ISFM_{IPWRA}^A = N_A^{ - 1}\sum _{i = 1}^N{H_i}\left( {r_A^*\left( {W,\gamma _A^*} \right) - r_{NA}^*\left( {W,\gamma _{NA}^*} \right)} \right)$$

$$ISFM_{IPWRA}^A = N_A^{ - 1}\sum _{i = 1}^N{H_i}\left( {r_A^*\left( {W,\gamma _A^*} \right) - r_{NA}^*\left( {W,\gamma _{NA}^*} \right)} \right)$$

in which the parameters

![]() $\delta _A^*$

and

$\delta _A^*$

and

![]() $\delta _{NA}^*$

are obtained from weighted regression procedures. Furthermore, an over-identification test is conducted to assess the equilibrium of the sample after applying inverse probability weighting. Normalized differences were also computed for each covariate (Imbens and Wooldridge, Reference Imbens and Wooldridge2009; Yeboah et al., Reference Yeboah, Balcombe, Asante, Prah and Aidoo2023). The IPWRA method is predicated on the assumption that, given the covariates, every observation has a positive likelihood of being an adopter. This is known as the overlap assumption. It is crucial to ensure the existence of a non-adopting respondent with similar attributes for each adopting respondent. To address this, a tolerance level ranging from

$\delta _{NA}^*$

are obtained from weighted regression procedures. Furthermore, an over-identification test is conducted to assess the equilibrium of the sample after applying inverse probability weighting. Normalized differences were also computed for each covariate (Imbens and Wooldridge, Reference Imbens and Wooldridge2009; Yeboah et al., Reference Yeboah, Balcombe, Asante, Prah and Aidoo2023). The IPWRA method is predicated on the assumption that, given the covariates, every observation has a positive likelihood of being an adopter. This is known as the overlap assumption. It is crucial to ensure the existence of a non-adopting respondent with similar attributes for each adopting respondent. To address this, a tolerance level ranging from

![]() $p = 0.001$

and

$p = 0.001$

and

![]() $p\; = \;0.999$

was established for the likelihood of adoption. Violation of this assumption can lead to the estimator’s sensitivity to model specification resulting in inaccurate estimations.

$p\; = \;0.999$

was established for the likelihood of adoption. Violation of this assumption can lead to the estimator’s sensitivity to model specification resulting in inaccurate estimations.

Following Wongnaa et al. (Reference Wongnaa, Abudu, Abdul-Rahaman, Akey and Prah2023) and Yeboah et al. (Reference Yeboah, Balcombe, Asante, Prah and Aidoo2023), we computed the average treatment effect on the treated (ATT) as the difference in the predicted outcome of adopters and non-adopters as follows:

where

![]() $E\left\{ . \right\}$

is operator expectation,

$E\left\{ . \right\}$

is operator expectation,

![]() $Y_{iA}$

is potential outcome of ISFM adopters,

$Y_{iA}$

is potential outcome of ISFM adopters,

![]() ${Y_{iNA}}$

is potential outcome of ISFM non-adopters, and

${Y_{iNA}}$

is potential outcome of ISFM non-adopters, and

![]() $ISF{M_i}$

is treatment status (thus 1 if a farmer adopts ISFM and 0 otherwise).

$ISF{M_i}$

is treatment status (thus 1 if a farmer adopts ISFM and 0 otherwise).

Results and discussion

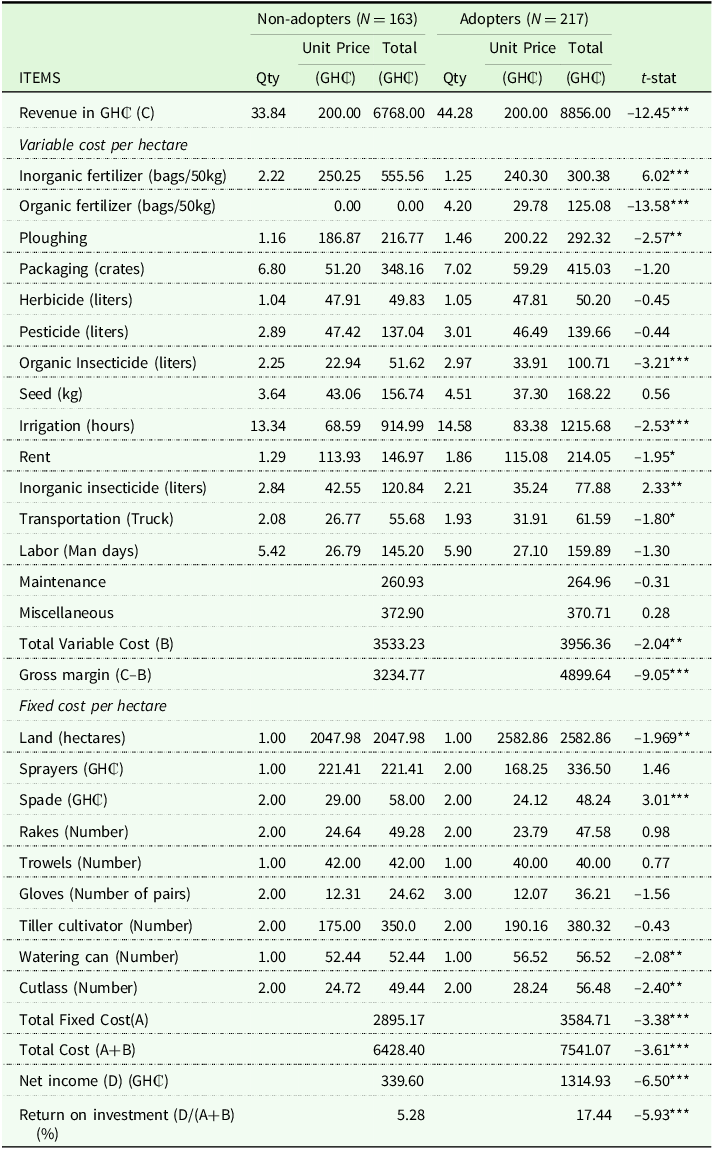

Welfare outcomes

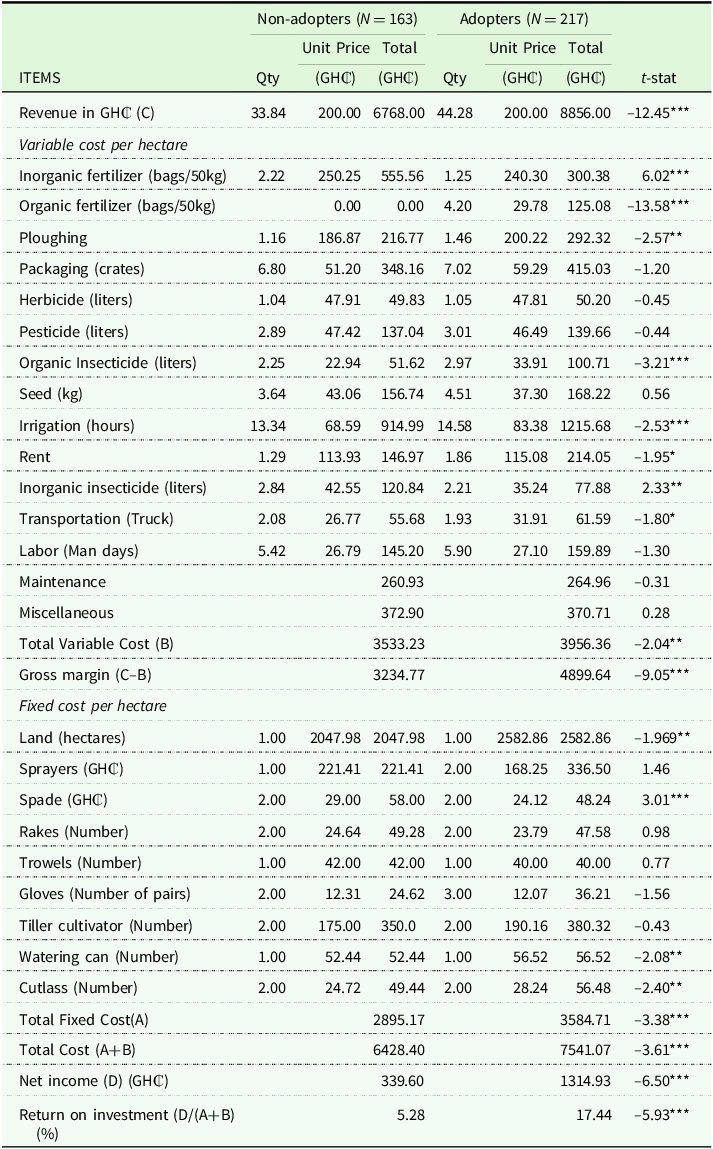

The study employed IPWRA in analyzing the impact of adoption of ISFM on the welfare of tomato farmers. The welfare indicators were net income, household food security, consumption accounting year, it is considered as fixed cost, hence spread over the years of its life. In Table 3, we find that the total fixed cost amounted to GH₵3584.71 per hectare for the adopters and GH₵2895.17 per hectare for the non-adopters. The net income of adopters was GH₵1314.93 resulting in 17.44% return on investment per hectare while that of non-adopters was GH₵339.60 resulting in 5.28% return on investment per hectare.

Table 3. Income Statement of adopters and non-adopters of ISFM

Note: ***, **, and * indicate significant levels at 1%, 5% and 10% respectively. T–tests are on respective total costs and revenues.

$1 = GH₵7.23 as at March 2022Footnote 1 .

Source: Field survey, 2022.

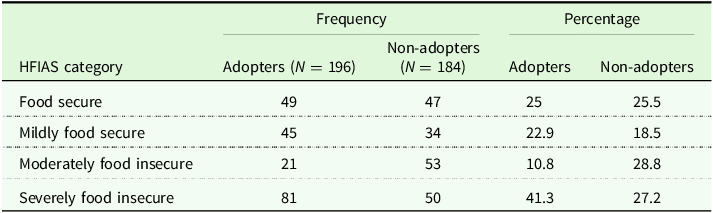

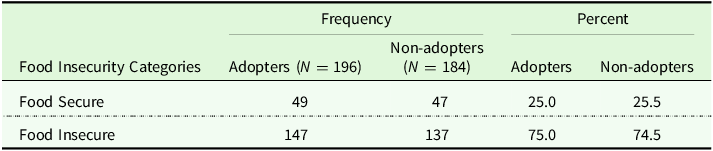

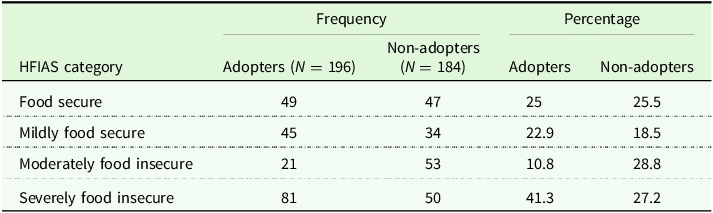

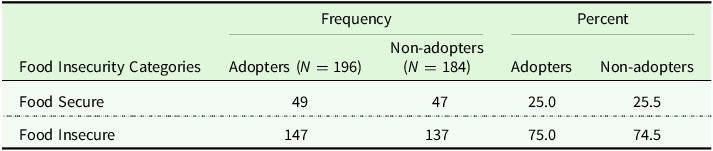

Based on the results shown in Tables 4 and 5, 49 adopters are classified as food secure, accounting for 25% of the total adopter population and 147 adopters classified as food insecure, representing 75% of the total adopter population. There are 47 non-adopters classified as food secure, accounting for 25.5% of the total non-adopter population and 137 non-adopters classified as food insecure, representing 74.5% of the total non-adopter population.

Table 4. HFIAS status

Source: Field survey, 2022.

Table 5. Food Security Status of respondents

Source: Field survey, 2022.

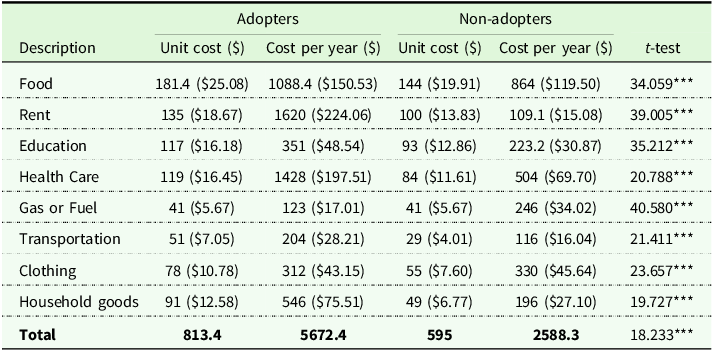

From Table 6, we find that total household expenditure per year for adopters was GH₵5672.4 and that of non-adopters was GH₵2588.3. The increase in household expenditure of adopters was as a result of the higher revenue they generated.

Table 6. Household expenditure

Note: $1 = GH₵7.23 as at March 2022. *** at 1%, ** at 5%, and * at 10%, respectively.

Source: Field survey, 2022.

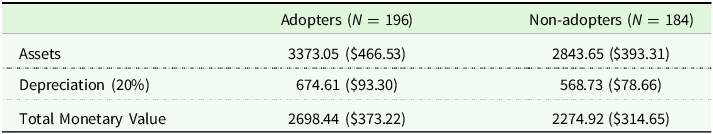

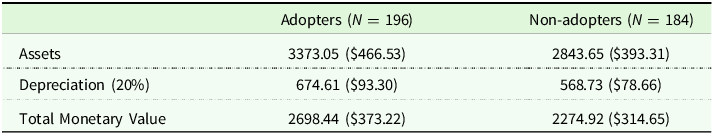

Table 7 presents the Monetary Value of Assets for adopters and non-adopters of ISFM, highlighting their respective average values. Among adopters, the average Asset Monetary Value is GH₵ 2698.44, while for non-adopters, it is GH₵2274.92. The difference in average asset values between adopters and non-adopters suggests that adopters have higher assets compared to non-adopters. This increase in assets among adopters can be attributed to their higher revenue generation resulting from adoption of ISFM practices.

Table 7. Asset Monetary Value

Note: $1 = GH₵7.23 as at March 2022.

Source: Field Survey, 2022.

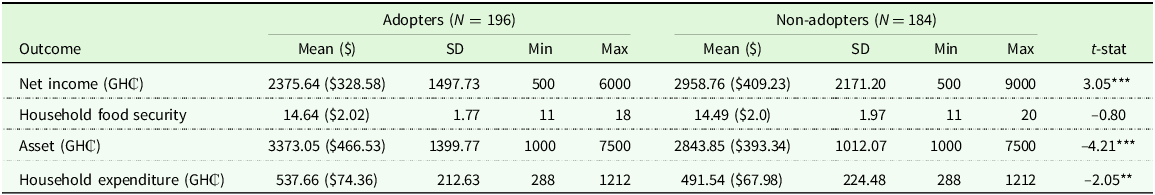

Table 8 presents a comparison of adopters and non-adopters’ welfare. We find that there was no significant difference between adopters and non-adopters in terms of their household food security. Also, it was discovered that there was a significant difference between the net income of non-adopters and adopters. The difference between the net income of non-adopters and adopters was 3.05. Also, it was discovered that the difference between the monetary value of assets of non-adopters and adopters was –4.21. Lastly, it was found that the difference between the household expenditure of adopters and non-adopters was –2.05. Of these, while net income and value of assets were statistically significant at 1%, household expenditure was significant at the 5% level.

Table 8. Comparison of welfare indicators

Note: $1 = GH₵7.23 as at March 2022. *** at 1%, ** at 5%, and * at 10%, respectively. SD is standard deviation.

Source: Field survey, 2022.

Factors influencing adoption of ISFM practices in tomato production

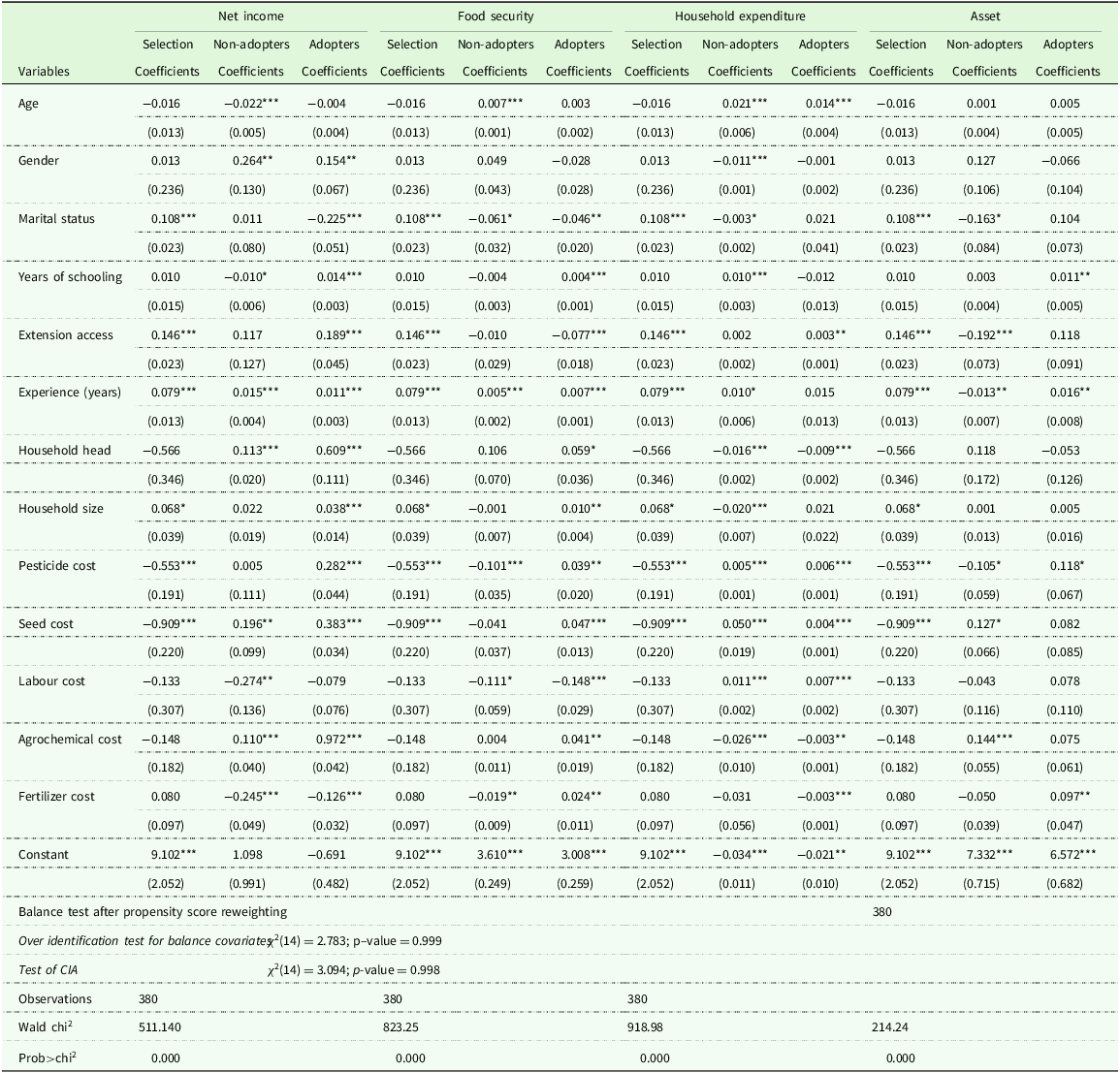

Table 9 presents the estimates of the IPWRA model. The validity of these results hinges on the soundness of the overlap assumption. To ensure this, only observations with adopter probabilities ranging from 0.001 to 0.999 are considered. No observation falls outside these bounds, indicating sufficient overlap in our sample. Additionally, the adopters and non-adopters in the inverse-probability-weighted sample need to be evenly distributed. Identification test was conducted to test the null hypothesis of balanced covariates. The over-identification test results suggested balanced weighted samples and that Conditional Independence Assumption (CIA) was satisfied (Table 9). The study computed normalized differences by applying weights to each control variable, with a maximum allowable difference of 0.25. All covariates remained below this threshold.

Table 9. Determinants of adoption and its impact on welfare of farmers

Note: Robust standard errors in parentheses. *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.01.

Source: Field survey, 2022.

The results from the selection equation in Table 9 indicate that marital status, extension access, farming experience, pesticide cost, and seed cost influence adoption of ISFM. Marital status has a positive influence on ISFM adoption. This suggests that married tomato farmers are more inclined to adopt ISFM. Similarly, the variable for access to extension service is positively related to adoption of ISFM, indicating that farmers with regular contact with extension agents will more likely adopt ISFM. This is consistent with the findings of Maertens et al. (Reference Maertens, Michelson and Nourani2021) and underscores the role of information in mitigating uncertainty about technology. Farming experience also has a positive influence on ISFM adoption, implying that farmers with more years in tomato farming will more likely adopt ISFM. This finding corroborates similar ones reported by Mwaura et al.’s (Reference Mwaura, Kiboi, Bett, Mugwe, Muriuki, Nicolay and Ngetich2021). Conversely, the variables for seed and pesticide costs, while statistically significant, carry negative coefficients, suggesting that farmers will less likely adopt ISFM when seed and pesticide costs are high.

Factors influencing welfare of adopters and non-adopters

Table 9 presents the findings on the factors influencing the net income of adopters and non-adopters of ISFM. Gender has a positive and significant impact on the net income of both farmer groups, indicating that irrespective of whether or not a tomato farmer adopts ISFM, being male corresponds to higher farm incomes. Marital status, on the other hand, has a negative and significant influence on the net income of ISFM adopters. This implies that married farmers practicing ISFM are more likely to experience lower net profits compared to their unmarried counterparts. Access to extension services has a positive and statistically significant influence on the net income of ISFM adopters, suggesting that access to agricultural extension increases the net profit of adopters. The coefficients of farming experience and being a household head are positively and significantly related to the net incomes of both adopters and non-adopters of ISFM, indicating positive impacts of these variables on net profits of both groups. Household size positively and significantly influences the net income of ISFM adopters. Pesticide and seed costs also have positive and significant impacts on the net incomes of both adopters and non-adopters. Labor cost, however, exerts a negative and significant influence on the net income of non-adopters, indicating that higher labor costs decrease the net income of farmers who do not practice ISFM. Agrochemical cost has a positive and statistically significant influence on the net income of both adopters and non-adopters. Conversely, fertilizer cost has a negative and significant influence on the net income of both groups, suggesting that an increase in fertilizer cost is associated with a decrease in the net income of both adopters and non-adopters.

Concerning food security, age is positive and statistically significant for non-adopters, indicating that aged non-adopters are more food secure than the youth. The marital status of farmers has a negative and significant influence on the food security of the tomato farmers. This suggests that whether or not a tomato farmer adopts ISFM, being married makes farmers food insecure. Years of schooling has positive and significant influence on food security of adopters. This implies that higher levels of education are likely to contribute to improved food security among farmers who practice ISFM. Access to extension is negative and statistically significant at the 1% level for adopters. This indicates that an increase in extension access is associated with a significant negative influence on food security of adopters. The variables for farming experience have positive and significant influence on food security of both groups. This indicates that an increase in years of farming experience is associated with significant positive influences on food security of all tomato farmers. The household head variable is positive and statistically significant at the 10% level for adopters in relation to food security. This suggests that being a household head and a farmer who practices ISFM has the probability of increasing food security. The household size variable is positive and statistically significant at the 5% level in relation to food security of adopters. This indicates that an increase in household size corresponds to a higher likelihood of improved food security for farmers who adopt ISFM. Pesticide cost has a negative and significant influence on the food security of non-adopters, suggesting that higher pesticide costs are associated with a decrease in food security among farmers who do not practice ISFM. However, for adopters, pesticide cost has a positive and statistically significant influence on food security. This finding suggests that farmers who practice ISFM and invest more in pesticides, despite the associated costs, are still able to maintain or even increase their level of food security. It implies that the benefits of practicing ISFM, such as improved soil fertility, enhanced crop productivity, and reduced reliance on external inputs, may offset the potential negative impact of pesticide cost on food security. The seed cost variable has a positive and significant relationship with food security among adopters. This suggests that farmers who practice ISFM are able to increase their food security level despite the increase in seed cost. Labor cost has a negative and significant influence on food security of both groups. This implies that as labor costs increase, there is a corresponding decrease in food security levels of both adopters and non-adopters. This suggests that higher labor costs pose a challenge to achieving and maintaining food security, regardless of whether farmers practice ISFM or not. The fertilizer cost variable exerts a positive and significant influence on the food security of adopters, indicating that adopters who invest more in fertilizer experience higher levels of food security. This positive relationship suggests that the use of fertilizers, when practiced within the context of ISFM, contributes to improved food security of adopters. This could be due to the positive synergistic effect of adoption of a combination of both organic and inorganic inputs. Conversely, for non-adopters, the fertilizer cost variable depicts a negative and statistically significant influence on food security at the 5% level. This implies that non-adopters who spend more on fertilizer tend to have lower levels of food security. The negative relationship suggests that fertilizer costs may pose a financial burden or inefficiency for non-adopters, leading to a negative impact on their food security.

For household expenditure, age is positive and statistically significant at the 1% level among the two groups. Gender has a negative and statistically significant influence on household expenditure of non-adopters, indicating that male farmers who have not adopted ISFM tend to have lower household expenditure levels. This finding suggests that there may be gender-based disparities in resource allocation and financial decision-making within non-adopter households. The marital status variable is negative and statistically significant in relation to household expenditure at the 10% level for non-adopters. This indicates that farmers who are not married and have not adopted ISFM tend to have lower levels of household expenditure. The negative relationship between marital status and household expenditure suggests that being unmarried, in the context of non-adopters, is associated with reduced financial resources allocated to household expenses. The years of schooling variable has a positive and statistically significant influence on household expenditure at the 1% level for non-adopters. This indicates that farmers who have not adopted ISFM but have spent more years in formal education tend to have higher levels of household expenditure. The extension access variable exerts a positive and significant influence on household expenditure of adopters at the 5% level. This suggests that farmers who practice ISFM and have access to extension services tend to exhibit higher levels of household expenditure. The variable for experience is positive and significant at the 10% level in relation to household expenditure of non-adopters. This suggests that the level of experience among non-adopting farmers has a positive association with their household expenditure. The household head variable exerts a negative and statistically significant influence on household expenditure for both groups at 1% levels. This indicates that the characteristics or attributes of the household head have an impact on the level of household expenditure. The household size variable is negative and statistically significant in relation to household expenditure of non-adopters. This suggests that as the household size increases, the level of household expenditure tends to decrease among farmers who do not practice ISFM. The variables for costs of pesticide, seed, and labor are all positive and statistically significant at 1% levels for both adopters and non-adopters in relation to household expenditure. This suggests that increases in essential inputs such as pesticides, seeds, and labor are associated with higher levels of household expenditure regardless of the farmer practicing ISFM or not. Conversely, the Agrochemical cost variable has a negative and statistically significant influence on household expenditure at the 1% and 5% levels for non-adopters and adopters respectively. This suggests that an increase in agrochemical costs is associated with lower levels of household expenditure. Similarly, the fertilizer cost variable has a negative and significant influence on household expenditure of adopters at the 1% level. That is, as the cost of fertilizer increases, farmers who practice ISFM tend to have lower levels of household expenditure.

On asset of farmers, the marital status variable is negative and statistically significant at the 10% level for non-adopters. This suggests that non-adopters who are married tend to have higher levels of assets compared to non-adopters who are not married. Married individuals may benefit from the pooling of resources, joint decision-making, and shared financial responsibilities within the household, which can contribute to the accumulation of assets. The years of schooling variable has a positive and significant influence on asset of adopters, suggesting that farmers who spend more years in acquiring formal education and practice ISFM tend to have more assets. The variable for access to extension is negative and statistically significant at the 1% level in relation to assets of non-adopters. This suggests that there is a negative relationship between access to extension services and asset accumulation among farmers who do not practice ISFM. The experience variable exerts a negative and significant influence on the asset of non-adopters but a significantly positive influence on the asset of adopters at the 5% levels. This indicates that experience plays a beneficial role in asset accumulation for farmers who practice ISFM unlike the non-adopters. The positive effect of experience on assets among adopters could be attributed to the cumulative knowledge, skills, and expertise gained through years of practicing ISFM techniques, which contributes to higher productivity and income levels. Pesticide cost has a negative and significant relationship with assets of non-adopters but a positive and significant relation with asset of adopters at the 10% levels. This suggests that as pesticide costs increase, non-adopters tend to have lower levels of assets. This could be due to the financial burden imposed by pesticide costs, which may limit their ability to invest in and accumulate assets. In contrast, for adopters, it suggests that adopters who practice ISFM may be able to effectively utilize pesticides to enhance their agricultural productivity, resulting in increased income and asset accumulation. Seed cost has a positive and significant influence on the assets of non-adopters at the 10% level. This suggests that non-adopters who are willing to incur higher costs of seeds may experience better agricultural outcomes, resulting in greater asset accumulation. The agrochemical cost variable has a positive and significant influence on assets of non-adopters at the 1% level, suggesting that higher agrochemical costs are associated with increased asset levels among non-adopters. This result implies that non-adopters who invest more in agrochemicals tend to accumulate more assets over time. Fertilizer cost has a positive and statistically significant influence on the asset of adopters at the 5% level, suggesting that higher fertilizer costs are associated with increased asset levels among adopters. This indicates that investment in fertilizer may lead to higher agricultural productivity and profitability, which, in turn, contributes to the accumulation of assets.

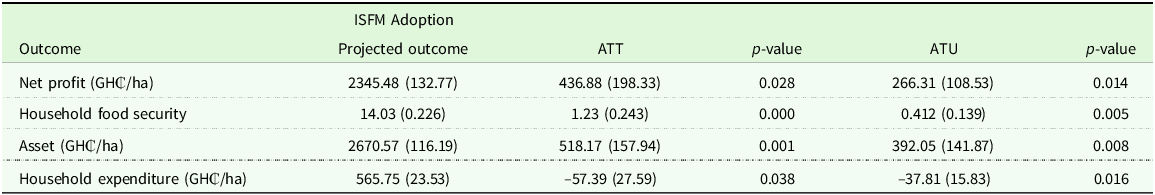

Impact of adoption of ISFM practices on the welfare of smallholder tomato farmers

Table 10 presents the results of the impact of adoption of ISFM on various welfare indicators, viz. net income, household food security, asset levels, and household expenditure. From the table, the calculated ATT value for net income is 436.88 and this is statistically significant at the 5% level. This indicates that adoption of ISFM leads to additional net profit of GH₵ 436.88 for tomato farmers. Similar findings were reported by Wu (Reference Wu2022) which revealed that adoption of new technology increased farmers’ incomes. For food security, ATT of 1.23 was obtained, and this is significant at the 1% level. This implies that adoption of ISFM is likely to increase household food security by 1.23 units. The ATT value for asset is 518.17, suggesting that adoption of ISFM has the tendency to increase asset accumulation by GH₵ 518.17. The ATT value for household expenditure is GH₵-57.39, and this is significant at the 5% level. This indicates that adoption of ISFM reduces household expenditure by GH₵57.39. The findings from Table 10 indicate the positive impact of adopting ISFM on various welfare outcomes. That is, adopters of ISFM tend to experience higher net incomes, improved household food security, increased asset levels, and reduced household expenditure compared to non-adopters. These results suggest that adoption of ISFM practices can contribute to improved agricultural productivity, income generation, and overall well-being of farming households. This is consistent with Horner and Wollni (Reference Hörner and Wollni2021) that reported a positive impact of adoption of ISFM on household welfare in Ethiopia. Harrison et al. (Reference Harrison, Funk and Peterson2019) also reported that adoption of ISFM improved farmers’ welfare in Zambia. Furthermore, our results reveal that if non-adopters were to adopt ISFM, they would have significant gains in income (GH₵266.31), food security (0.412 units), asset accumulation (GH₵392.05), and a reduction in household expenditure (GH₵37.81). These improvements highlight the potential of ISFM to enhance economic stability, increase food self-sufficiency, and reduce household expenditure.

Table 10. Impact of adoption of ISFM on welfare

Standard errors are in parenthesis. ATT is average treatment effect on treated. ATU is average treated effect on untreated.

Source: Field survey, 2022.

Conclusion and policy implications

ISFM refers to a holistic approach to managing soil fertility that combines a variety of techniques and practices to improve soil health and enhance agricultural productivity, particularly in smallholder farming systems. Despite the associated higher labor and other input demands associated with ISFM adoption, there is limited empirical evidence regarding the positive outcomes of these investments at the household level. Using data from 380 tomato farmers in three regions of Ghana, we explore the relationship between ISFM adoption and household welfare.

The results showed that in terms of finances, adopters of ISFM incurred a total fixed cost of GH₵3584.71 per hectare, significantly higher than the GH₵2895.17 spent by non-adopters. This discrepancy underscores the economic commitment required for ISFM adoption. The higher investment by adopters however resulted in a noteworthy net income of GH₵1314.93 per hectare, which yielded a substantial 17.44% return on investment relative to total cost. In contrast, non-adopters achieved a lower net income of GH₵339.60, which translated to a 5.28% return on investment relative to total cost. The aforementioned figures underscore the economic advantages associated with adoption of ISFM, highlighting its potential as a lucrative agricultural practice.

Age emerged as an important factor influencing ISFM adoption. The study reports a negative correlation, revealing that as the age of tomato farmers increased, the probability of adopting ISFM decreased. This underscores the need for targeted interventions and incentives to encourage adoption among older farmers, considering the potential benefits. Access to extension services proved to be another influential economic determinant. A positive relationship was identified, indicating that increased access to extension services increased the likelihood of ISFM adoption. This underscores the importance of enhancing extension services to help facilitate the dissemination of information and knowledge regarding ISFM, thereby promoting its adoption among smallholder tomato farmers. Household size and household headship status were also identified as significant factors influencing ISFM adoption. Larger household sizes were found to increase the probability of adoption, suggesting potential economic benefits associated with collective decision-making and labor resources within larger households. Conversely, being a household head exerted a negative impact on ISFM adoption, signaling the need for targeted strategies to address potential barriers faced by household heads in adopting ISFM. Farming experience exerted an interesting economic impact, as an increase in experience was related to a decrease in ISFM adoption. This unexpected finding prompts further exploration into the reasons behind the reluctance of more experienced farmers to adopt ISFM, potentially uncovering barriers or misconceptions that hinder its adoption.

The economic benefits of ISFM adoption were further substantiated by our findings. Adopters experienced a significant increase in net income by GH₵436.88, underscoring the positive economic impact of ISFM adoption on individual farmers. Additionally, household assets and food security showed notable improvements following ISFM adoption, with increases of GH₵518.17 and 1.23, respectively. These economic enhancements highlight the potential of ISFM adoption not only in improving individual financial well-being but also in bolstering broader household economic stability and food security. Finally, the study found a GH₵57.39 reduction in expenditure following ISFM adoption. This suggests that ISFM adoption can contribute to cost-effectiveness and resource optimization, further reinforcing its positive impact on the economic aspects of smallholder farming. In conclusion, our comprehensive economic analysis affirms that adoption of ISFM in Ghana has multifaceted positive impacts. These include increased net income, improved household assets, enhanced food security, and reduced expenditure. That is, ISFM adoption could contribute significantly to poverty reduction and sustainable agricultural development.

Based on the findings of the study, the economic policy recommendation is to actively promote and support the widespread adoption of ISFM practices among smallholder farmers. Policy makers should consider implementing measures to help facilitate access to enhanced seeds as well as organic and inorganic fertilizers, by making them more affordable and available to farmers. Additionally, awareness campaigns and training programs tailored to local contexts should be instituted to educate farmers about the benefits of ISFM adoption and how to effectively implement these practices. Moreover, agricultural policies should aim to reduce the cost of pesticides through subsidies or bulk purchasing schemes, especially for non-adopters, to enhance their welfare outcomes. Additionally, training programs should be implemented to improve the efficient use of pesticides among all farmers, emphasizing the benefits of integrating these inputs into ISFM practices to maximize productivity and minimize negative financial impacts. Finally, policy makers should prioritize investment in rural education, focusing on formal education and targeted agricultural training programs. Extension services should also incorporate educational components tailored to ISFM adoption, ensuring that farmers, regardless of their adoption status, are equipped with the necessary skills to enhance productivity and welfare. Providing scholarships or incentives for young farmers to pursue agricultural education could further bolster these efforts.

Policy makers should prioritize the aforementioned interventions as part of a comprehensive economic strategy aimed at enhancing the economic well-being of smallholder farmers and fostering long-term agricultural sustainability.

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request.

Funding statement

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.