Recent advances in Roman archaeology in Greece

The last decade has proven particularly fruitful for Roman studies, especially regarding the archaeology of the Roman period in Greece (Di Napoli et al. Reference Di Napoli, Camia, Evangelidis, Grigoropoulos, Rogers and Vlizos2018). This is largely due to the growing recognition within a segment of the academic community that this field should not be viewed merely as a subset of Classical archaeology – nor simply as a continuation of the Classical and Hellenistic periods – but as a distinct domain with its own questions, dynamics, and material culture. Roman archaeology in Greece is now situated within a broader perspective that extends beyond the traditional boundaries of the Greek world. (Grigoropoulos Reference Grigoropoulos and Burrell2024: 392). Interestingly, there has been a notable shift away from the traditional emphasis on sculpture, which for many years dominated earlier scholarship of Roman archaeology. Scholars are now increasingly focusing on themes such as spatial organization and infrastructure (Aristodemou and Tasios Reference Aristodemou and Tassios2018), urbanization (Karambinis Reference Karambinis, De Ligt and Bintliff2018), the development of rural landscapes (Ketanis Reference Ketanis2024), and the urban landscape (Vitti Reference Vitti2016; Evangelidis Reference Evangelidis2020). This has been accompanied by studies of faunal and human skeletal remains (Vergidou et al. Reference Vergidou, Karamitrou-Mentessidi, Voutsaki and Nikita2021; Reference Vergidou, Karamitrou-Mentessidi, Voutsaki and Nikita2022) as well as investigations into the formation of memory and identity (Dijkstra et al. Reference Dijkstra, Kuin, Moser and Weidgenannt2017). These new research directions are breaking through the constraints of the local archaeological tradition and situating the material culture of the area within wider Mediterranean and provincial frameworks. This emerging body of work highlights the interconnectedness of Greece’s Roman past with larger imperial processes, as well as the localized expressions of these influences. Fieldwork and analysis over the last decade have provided critical insights into how urban and rural settlements were structured and transformed, how identities were negotiated in a dynamic provincial environment, and how the memory of earlier periods was integrated into Roman material and cultural contexts. Such research enriches our understanding of provincial archaeology and, in doing so, fosters a comparative approach that resonates across the Mediterranean world. Macedonia – specifically, part of the territories of the Roman Macedonia that lie within modern Greek border – has played a pivotal role in advancing these new avenues of research (see the overview in Evangelidis Reference Evangelidis and Burrell2024). This is largely due to the abundance of public infrastructure projects, many of which were initiated in the early twenty-first century, alongside more recent undertakings such as the construction of Thessaloniki’s Metro and the Trans Adriatic Pipeline (TAP). These projects have uncovered invaluable archaeological data, casting new light on various aspects of the region’s Roman past. The discoveries span a wide spectrum, revealing insights into the densely built urban fabric of cities, such as Thessaloniki, as well as evidence concerning the rural hinterland. Findings from these projects illuminate the organization of agricultural landscapes, the dynamics of settlements, and the nature of individual sites scattered across the interior of Macedonia.

An influx of new data holds the promise of opening up opportunities to address broader questions of spatial organization, economic networks, and cultural interactions within the Roman province. However, much of this wealth of information has yet to be fully exploited. While there are occasional studies that attempt to harness its richness, a significant portion of this data comes from the Archaiologikon Ergon sti Makedonia kai Thraki (AeMTh)/Αρχαιολογικό Έργο στη Μακϵδονία και Θράκη (ΑEΜΘ), an annual meeting of archaeologists working in Northern Greece. Since its establishment in 1987, this conference has been a cornerstone for scholars seeking a comprehensive understanding of the region’s archaeology.

Despite the challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic, the annual conference has continued without interruption. However, the last published volume dates to 2016 (Adam-Veleni Reference Adam-Veleni2022). The forthcoming volumes are eagerly anticipated, as they will greatly enhance the accessibility and timely use of the valuable data presented at these gatherings – not to mention help to avoid a publishing backlog of nightmarish proportions. Alternative sources of information include (but are not limited to) the reports from the TAP (Skartsis Reference Skartsis2021) and the recently published work of all the Ephorates covering the period 2011–2019 (Antonopoulou and Petrounakos Reference Antonopoulou and Petrounakos2022). These sources provide valuable insights and a broader perspective on the extensive archaeological work carried out during this time.

In what follows, I will explore new projects and fieldwork conducted within the borders of Greece, categorized into two main areas: the urban sites, whether beneath modern cities or part of an ancient urban fabric; and the rural sites (Map 5.1). Inevitably, overlaps occur, as the boundaries between these spheres often intersect. While remarkable discoveries are also being made beyond Greece, such as the spectacular finds at Heraclea Sintiki (Vagalinski Reference Vagalinski2022) and Stobi (Blaževska, Snively and Gebhard Reference Blaževska, Snively and Gebhard2024), these will regrettably fall outside the scope of this report.

Map 5.1. 1. Kleitos; 2. Theodosia; 3. Isoma; 4. Nea Mesimvria; 5. Drymos; 6. Lipochori; 7. Peristerias; 8. Vasileiada; 9. Platamonas Goritsa; 10. Philippi (vicus); 11. Kalamonas; 12. Koronouda, Kilkis; 13. Nea Zichni; 14. Karteres; 15. Symvoli, Serres; 16. Assiros; 17. Thassos; 18. Petres; 19. Longos, Edessa; 20. Morrylos; 21. Europos; 22. Nea Santa; 23. Vergina (Aigai); 24. Dion; 25. Philippi (city); 26. Thessaloniki; 27. Amphipolis; 28. Terpni; 29. Villa Alexandros, Amyntaion; 30. Argos Orestikon; 31. Paralimni; 32. Antigonos; 33. Philotas; 34. Pyrgoi Omaloi; 35. Ilarion dam; 36. Velventos; 37. Agios Georgios; 38. Pontokomi-Vrysi; 39. Nea Kerdylia Strovolos.

Work and research on urban sites

The past decade saw the continuation of work across all major urban sites of the Roman period, focusing on refining earlier research (evident in Thassos, see Trippé Reference Trippé2019), clarifying the function of spaces, and implementing measures for better protection against climatic changes. This was particularly evident in projects such as the Hellenistic city of Petres (Naoum Reference Naoum2022) and the Longos area, the lower part of the walled city of Edessa (Zambiti, Vouvoulis and Maniataki Reference Zambiti, Vouvoulis and Maniataki2019–2020; Tsigarida et al. Reference Tsigarida, Georgiadou, Zambiti and Stalidis2022: 294–97), and also well-known intra-urban archaeological sites such as the walls of Thessaloniki (Tokmakidou and Kaltapanidou Reference Tokmakidou and Kaltapanidou2015) and the city of Beroia (Graikos Reference Graikos2019–2020). Within this new framework of dissemination and public engagement, sites such as Morrylos in Krestonia – an important hub for trade, the movement of goods, and home to a significant Asklepieion – and Europos, a site with evidence of continuous settlement and rich funerary architecture from the Roman period, have gained renewed attention (Poulakakis et al. Reference Poulakakis, Stratouli, Farmaki and Vretzaki2019–2020). These renewed efforts in dissemination, including exhibitions and public outreach initiatives, are bringing these important sites and their histories to a wider audience.

In many areas, new evidence is opening opportunities for studying urban environments; for example, with the discovery of a new fortified site of the Late Hellenistic period near the village of Nea Santa (in the area of Pedino, Kampani) at Kilkis (Stratouli et al. Reference Stratouli, Poulakakis, Papadopoulou, Kayiouli, Vouvoulis, Katsikaloudi and Skreki2023). One key observation is that abandonment is never absolute – sites were rarely, if ever, completely deserted. Even sites such as Vergina (Aigai), traditionally thought to have yielded little Roman-period material, are now revealing significant findings through refined analytical methods. A striking example is a large building complex near the northwest gate of the ancient city (Kottaridi 2019–2020; Reference Kottaridi2022; ID 116312). Originally constructed at the end of the fourth century BCE and destroyed in the mid-second century BCE, parts of the western and eastern wings were later rebuilt. During the Augustan era, a large peristyle (1,000sqm) with a mosaic floor was added to the southeast, demonstrating the site’s continued use and adaptation.

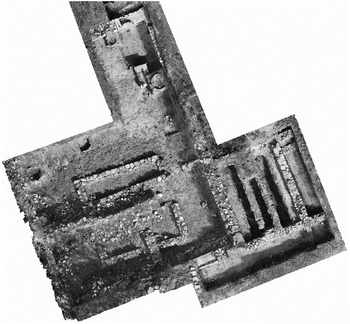

Another important aspect is the increasing emphasis on the continued significance of many sites during Late Antiquity and the Early Christian period, particularly the fourth and fifth centuries CE. Despite occasional setbacks, this era marked a period of development for Macedonia, which lay closer to the new imperial centre of Constantinople, as ongoing archaeological research continues to demonstrate. At the Roman colony of Dion, a site that exemplifies the growing focus on Late Antiquity, the past decade – marked by the passing of the long-time director of the Aristotle University excavation, Professor Dimitrios Pantermalis, and more recently of his successor, Professor Semeli Pingiatoglou – has seen continued excavations, primarily within the fortified city. These efforts have concentrated on previously explored areas, such as the shops along the central street, as well as adjacent sectors like the ’House of Zosas’ (east of the central paved road and north of the fortification wall), aiming to refine the site’s stratigraphy and expand our understanding of its later phases. Key findings include the identification of five main chronological phases within the ‘House of Epigenes’ (ID 11014; an elite residence in the southwestern part of the Roman forum, on a higher terrace south of the Sebasteion, dating to the early fourth century CE) ranging from the late Hellenistic to the late fifth century CE (Pingiatoglou et al. Reference Pingiatoglou, Papagianni, Vasteli, Paulopoulou and Tsiafis2016: 165; Pingiatoglou, Papayianni and Vasteli Reference Pingiatoglou, Papayianni and Vasteli2019–2020). Excavations west of the Central Road and in this residential area revealed important insights into the city’s development. In the middle part of the south stoa/part of the Roman forum, a large rectangular public hall was uncovered, although its specific function remains unknown (Pingiatoglou et al. Reference Pingiatoglou, Papagianni, Vasteli, Paulopoulou and Tsiafis2016: 163). The excavation in the area northeast of the ‘House of Zosas’ (Fig. 5.1) uncovered remains of two building phases, one dating from the third–fourth century CE based on the ceramic evidence, and another related to a zone that had been outside the city’s Late Roman fortifications. This suggests continuous urban expansion and transformation, particularly during the Roman and Late Roman periods. One of the most significant discoveries during this decade was the excavation of a large hall in the sector known as ‘Ereipionas’ (northwest of the Episcopal Basilica) (Fig. 5.2).

Fig. 5.1. The Late Roman house of Zosas at Dion. © Pingiatoglou et al. Reference Pingiatoglou, Papagianni, Vasteli, Paulopoulou and Tsiafis2016: 164.

Fig. 5.2. The Ereipionas sector at Dion.©

The hall’s size (11.2m east–west, 15.8m north–south), frescoes (depicting architectural features), water supply system (via a lead pipe with a stamp bearing the name Heliodoros), and underfloor heating system highlight the economic affluence of its owner/donor, although its exact use remains unknown.

Numismatic evidence points towards a second century CE date, but the hall continued to be used until the fifth century CE, with evidence of its repurposing for storage, as indicated by the presence of pithoi and amphorae. Excavation of the deeper strata revealed that the building had been constructed atop earlier structures, associated with Hellenistic-era finds such as black-glazed sherds and fragments of relief-decorated hemispherical skyphoi dating to the late third century BCE. Since 2017/2018, excavations at Dion have continued under new directorship, with a renewed focus on material from Late Antiquity and the city’s later phases. In 2023, work in the ‘Kanavos’ area (north of the Episcopal Basilica) uncovered a pouch containing 32 bronze coins, helping to date a building, likely a bathhouse, to the late fourth and fifth centuries CE (Papagianni et al. Reference Papagianni, Kasseropoulos, Kyriakopoulou, Rigou and Fragkoulis2024). Coins from the reigns of Emperors Leo (457–74 CE) and Zeno (476–91 CE) provided further chronological insights. Evidence of collapsed walls suggests that one phase of the building’s destruction may have been caused by a major earthquake, a pattern observed elsewhere in the ancient city.

Similar to Dion is the other great Roman colony of Macedonia, Philippi, where recent archaeological work highlights a renewed emphasis on re-examining earlier evidence while integrating new discoveries to refine our understanding of the site’s history and development (Sève and Weber 2022; Reference Sève and Weber2023). Between 2018 and 2023, Michel Sève (Université de Lorraine – Metz) and his team (Sève, Weber and Biard Reference Sève, Weber and Biard2018) focused on the western side of Philippi’s forum, including the curia and eastern temple (ID 19566). Their research refined the architectural timeline of these monuments and revealed the lower level of their pronaos, built in ashlar masonry. They also examined the impact of a great earthquake around 500 CE, particularly on the forum’s western side, identifying emergency wooden supports for the curia (assembly house used by the ordo decurionum) a later-added doorway in the five-column room, and the reuse of honorific bases for structural reinforcement. Additionally, their analysis of the roofing structures led to a proposed reconstruction of the superstructure, emphasizing a cohesive yet adaptable architectural design applied across key monuments.

Ceramic studies have complemented these architectural investigations. From 2020, Catherine Abadie-Reynal (Université Lumière-Lyon 2, UMR 5189-HiSoMA) and her team (Abadie-Reynal and Daszkiewicz Reference Abadie-Reynal and Daszkiewicz2020; Abadie-Reynal and Giannaki Reference Abadie-Reynal and Giannaki2023) re-examined Roman ceramics from earlier excavations, focusing on the abundant common wares and the prominence of Italian imports and their imitations from the second century CE, providing valuable insights into regional trade networks and cultural exchanges, bolstered by an ongoing comparative study with Thasian ceramics (ID 17442).

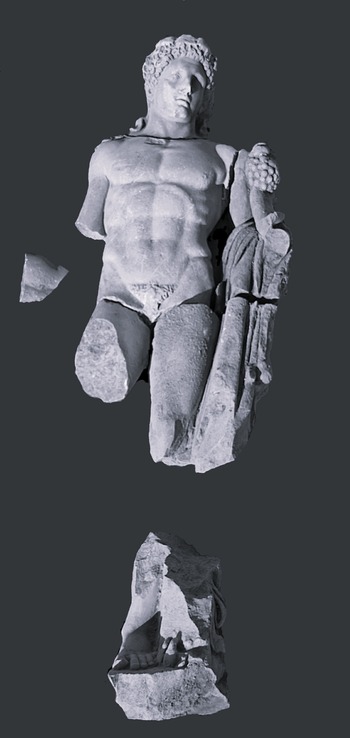

Meanwhile, excavations conducted by Aristotle University of Thessaloniki – led by Natalia Poulou, with Anastasios Tantsis and Aristotelis Mentzos (Poulou, Tantsis and Mentzos Reference Poulou, Tantsis and Mentzos2021; Tantsis and Poulou Reference Tantsis and Poulou2019–2020) – in the areas east of the forum continue to reveal new evidence regarding the urban development and monumentality of the Early Christian city, a monumentality that persisted until the eight century CE; this later date is based on the discovery of a bronze follis of Leo I (457–74 CE), which further demonstrated the prolonged use of these spaces into the Byzantine period (ID 19209). Within this context, a particularly impressive find is a monumental building located at the intersection of two roads, with its façade facing a public square. Here, the convergence of the two streets appears to create an open space (a plaza?), dominated by a richly decorated architectural structure – possibly a fountain adorned with reused statues. The fountain featured elaborate architectural ornamentation, fragments of which have been uncovered. Among the most striking discoveries in the site of the fountain is a large Roman-era statue depicting Heracles. The statue, larger than life-size, portrays the hero as a youthful, beardless figure with a muscular body (Fig. 5.3). His identity is confirmed by the presence of a club, found in fragments, and a lion skin draped over his extended left arm. Additionally, the figure wears a wreath of vine leaves, held in place at the back of his head by a ribbon whose ends fall onto his shoulders. The statue dates to the second or early third century CE. Another significant find is a sculpted head, which appears to belong to a statue of the god Apollo. These discoveries provide valuable insights into the continued monumentality and artistic traditions of the Early Christian city, illustrating how elements of the Classical past were integrated into the later urban and public space.

Fig. 5.3. The reassembled statue of Hercules at Philippi. © University Excavation of Philippi / Hellenic Ministry of Culture.

Metro excavations in the heart of Thessaloniki

It is impossible to compose an archaeological report on Roman Macedonia without referencing the extensive work carried out by the local Ephorates of Antiquities, supported by dozens of contract archaeologists, within the framework of the Thessaloniki Metro construction (Adam-Veleni et al. Reference Adam-Veleni, Skiadaresis, Vasileiadou, Antonopoulou and Petrounakos2022). This project, one of the largest urban archaeology endeavours in Greece, has engaged the city for years and stands as a landmark example of the intersection between modern development and cultural heritage (Adam-Veleni and Mylopoulos Reference Adam-Veleni and Mylopoulos2018). It also sparked significant controversies over the decision to relocate the antiquities uncovered during the construction works instead of preserving them in situ. At the time of writing this report, the Metro has finally been inaugurated – a milestone for the city’s transportation infrastructure that also symbolizes the remarkable archaeological contributions made throughout its development. The fierce debates surrounding the project – an indicator of an engaged and responsive local community – did not overshadow the transformative impact of the Metro excavations. These investigations have profoundly enriched our understanding of Late Roman and Early Christian Thessaloniki (fourth–sixth century CE), revealing a thriving metropolis (Makropoulou Reference Makropoulou2013). Among the most notable findings was the monumental design of the city’s main decumanus (east–west street), flanked by vibrant neighbourhoods, workshops, and commercial establishments that attest to the city’s dynamic commercial activity.

The chronological horizon of most of the finds extends from the fourth century CE – a period of great prosperity for the city – to the seventh century CE. The excavations revealed the monumental configuration of the central decumanus, along with various structures, both private and public, that lined the road. Extensive archaeological work was conducted at all Metro stations within the fabric of the ancient city. While significant finds were uncovered across nearly every station along the 9km course of the Metro, notable discoveries include monumental architecture at the Venizelou and Hagia Sophia stations (ID 8155; 6610; 6654; 2704; 4586; 2937; 2266) and cemeteries at the New Railway Station and Syntrivani stations.

At both the Hagia Sophia (Vasileiadou and Tzevreni Reference Vasileiadou and Tzevreni2020) and Venizelou (Konstantinidou and Miza Reference Konstantinidou and Miza2020) stations, excavations have confirmed the presence of the Hippodamian grid plan in Thessaloniki’s lower section, originating in the Hellenistic era. This organized urban layout, with its systematic, porticoed streets, continued through the Roman and Late Roman periods, persisting into the seventh, eighth, and even the ninth century CE. Central to this plan was the decumanus maximus, the main east–west street, known in the Byzantine period as Mesi Leoforos (ID 3065). This thoroughfare remained a vital artery of the city, connecting the Kassandreotiki Gate in the east with the Golden Gate in the west. Following the mid-fourth century, during the period of the successors of the emperor Constantine (306–37 CE) and later during the reign of Theodosius I (379–95 CE) (Vasileiadou and Tzevreni Reference Vasileiadou and Tzevreni2020: 55), the decumanus maximus underwent significant reconstruction.

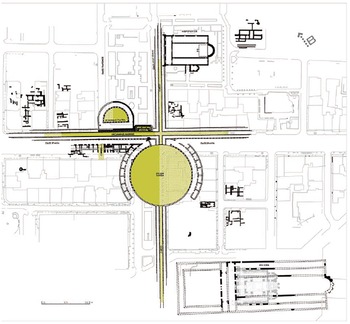

The road (Konstantinidou and Miza Reference Konstantinidou and Miza2020: 10) is impressively preserved at the Venizelou station (see Fig 5.4), where a 77-metre segment of the decumanus maximus was uncovered, intersecting with a north-south cardo (lying under the modern day Venizelou street). A twentieth-metre portion of this cardo was excavated, revealing its connection between the city’s northern walls and the harbour, a vital infrastructure built during the reign of Constantine. Both the decumanus maximus and the cardo were paved with large irregular marble slabs, bordered by marble sidewalks, and flanked by colonnaded porticoes. The preserved stylobates (bases for columns) from the fourth and fifth centuries remain visible today, offering a glimpse into the city’s architectural grandeur. Beneath the cardo ran a central vaulted drainage pipe, highlighting emphasis on practical urban infrastructure. The decumanus maximus measured four metres in width, expanding to 17 metres when including pavements and porticoes. The cardo, slightly narrower, measured between 2.8 and 3.3 metres in width, expanding to around 15 metres with its porticoes. A particularly significant discovery at the intersection of these streets was a previously unknown monumental tetrapylon – a four-way arch (Konstantinidou and Miza Reference Konstantinidou and Miza2020: 33) that served as a focal point of the urban grid. Within the excavation area, 12 of the 16 piers supporting the tetrapylon were uncovered. Four central piers formed the structure’s core, while additional pairs integrated into the colonnaded porticoes. The southernmost piers had an L-shaped design, likely mirrored in the north, merging seamlessly with the porticoes. Four more piers at the intersection’s inner corners adjoined surrounding buildings, creating a sophisticated layout with three parallel porticoes along each axis. When viewed in the broader context of Thessaloniki’s urban landscape, this intersection, with its impressive tetrapylon, complements the Tetrapylon of Galerius to the east. Together, they form a unique and cohesive urban vista, unparalleled in Greek urban design, underscoring the city’s monumental character and its emphasis on ceremonial passageways and pedestrian movement. This monumentality is further supported by other findings, such as the impressive architectural remains of a grand Early Christian building at the intersection of Stratigou Doumpioti and Philotas streets featuring a peristyle marble-paved courtyard, a monumental staircase, and water management structures that incorporated marble spolia sourced from a monumental structure dating back to the Late Archaic period (early fifth century BCE) in the wider area (Skiadaresis Reference Skiadaresis2022: 177).

Fig. 5.4. Venizelou Station. Ground plan of the archaeological site. © Ephorate of Antiquities of Thessaloniki City.

Evidence of monumentality also emerged from the Hagia Sophia station, where excavations revealed a grand fountain or nymphaeum at the intersection of the decumanus maximus and the cardo of Hagia Sophia Street to the east (Vasileiadou and Tzevreni Reference Vasileiadou and Tzevreni2020: 40–43). This U-shaped nymphaeum, featuring a theatrical façade (scaenae frons), underwent modifications during the fifth and sixth centuries and remained in use until the seventh century, when earthquakes caused significant damage. The fountain was not an isolated structure. Excavations uncovered evidence of grand urban mansions, including one on the eastern side of the street that spanned approximately 300 square metres (Vasileiadou and Tzevreni Reference Vasileiadou and Tzevreni2020: 43–48). This luxurious residence featured an atrium surrounded by porticoes, two-story rooms, and a private bathhouse with a well-preserved hypocaust heating system. Renovations in the early fifth century added rooms, a cistern, and intricately patterned mosaic floors, dated by coins embedded in the mosaic substrates. The atrium’s mosaic was especially elaborate, with a multi-coloured marble frame surrounding an impluvium and mosaic bands depicting Aphrodite and Eros. In addition to these elite residences, the northern side of the main street was lined with shops and workshops for metalworking and glass production, which became centres of bustling urban life following the gradual abandonment of the agora.

As someone moves away from the central stations and the margins of the ancient city, the excavations in other stations, such as the New Railway Station or the Syntrivani station, brought into light a wealth of new features linked to the extensive necropoleis that framed the east and western gates of the city (Acheilara Reference Acheilara2011; ID 19676). Excavations at the New Railway Station uncovered a 750m2 section of the western necropolis, in use from the late fourth century BCE to the fourth century CE (Misailidou-Despotidou Reference Misailidou-Despotidou2017). The Hellenistic phase revealed 48 graves – mostly trench, pit, tile-covered, and box-shaped – dominated by inhumations with occasional cremations. Notable finds include a second-century BCE burial (Tf164) of a woman adorned with gold headdress decorations. In the Roman period, the cemetery became more structured, with 31 graves organized within stone-walled enclosures, possibly reflecting social stratification. Grave goods included coins, glassware, ceramics, and jewellery, with one burial containing a dog, hinting at ritual practices. Further excavations at the Dimokratias metro station revealed 218 additional graves, also arranged within enclosures, along with wells and refuse pits linked to funerary customs, underscoring the cemetery’s vast extent (Misailidou-Despotidou Reference Misailidou-Despotidou2017: 299–304). To the east, workshops and warehouses from the second to seventh–eighth centuries CE, likely serving burial-related needs, were abruptly abandoned after a fire. Key finds include coins from Justinian I (527–65 CE) a treasure from Justin II (685–711 CE), and Late Roman 2 amphorae, providing valuable chronological insights.

Excavations at the Syntrivani metro station uncovered a 950m2 section of Thessaloniki’s eastern necropolis (Acheilara Reference Acheilara2015), revealing 442 graves spanning from the Hellenistic to Late Roman periods (Fig. 5.5; ID 19770). The cemetery saw dense, continuous use, with overlapping and reused burials. Only nine Hellenistic tombs were found – five built and four pit graves – containing inhumations, cremations, and typical grave goods such as clay vessels, figurines, and jewellery. In contrast, the Roman phase yielded 433 graves of various types, including a vaulted tomb, with many featuring stone-built altars for libations. Inhumation was dominant, often with multiple burials or reburials, and 47% contained grave goods such as pottery, coins, and gold danakes (Charon’s obol), reflecting social diversity (for jewellery findings in both the eastern and western cemeteries, see Nikakis Reference Nikakis2019). Nearby, a large 7.2m-deep circular stone structure, dated to the fourth century CE by a coin of Constans I (337–50 CE) suggests significant Roman-era storage, possibly for grain or water. A unique discovery in the Syntrivani area, near the nineteenth-century Ottoman fountain, and within Thessaloniki’s eastern cemetery, is a three-aisled Early Christian basilica dating to the fifth century CE (Païsidou Reference Païsidou2010). The basilica features an apse with a synthronon, a framed sanctuary, the basement of a trapeza (refectory), and an enkainion (a small cist under the altar holding relics, likely associated with a martyrion or locus commemorationis. Notably, the south aisle contains two rows of pre-existing vaulted tombs, one of which held the remains of an individual (professional soldier?) buried with a bent sword, a spearhead, and a shield boss (Maniotis Reference Maniotis2023).

Fig. 5.5. Syntrivani Station. Eastern cemetery. Acheilara Reference Acheilara2015. © Ephorate of Antiquities of Thessaloniki City.

New fieldwork projects

Despite the scale and significance of the Thessaloniki Metro excavations, they were not the only major fieldwork initiatives. The decade from 2014 to 2024, despite economic challenges and the disruptions of the COVID-19 pandemic, saw a resurgence of archaeological projects. While these may not rival the scope of earlier excavations at sites such as Dion, Philippi, or Thassos, they emphasize innovative methodologies, holistic data integration, and the use of geospatial technologies and advanced mapping, yielding important new insights. A significant project at the Acropolis of Amphipolis (Malamidou Reference Malamidou2022: 433), led by Dinitris Damaskos (University of Patras) in collaboration with the Ephorate of Serres and Dimitria Malamidou (Ephorate of Serres), aimed to reassess excavations from the 1960s–70s (Damaskos et al. 2019–2020; Reference Damaskos, Malamidou, Eleftheraki, Varsanis and Ginoudis2024). Earlier finds included city walls, four Early Christian basilicas, a Roman villa with mosaics, a public Roman building, and Classical houses. The current project employs ground-penetrating radar to detect subsurface remains and documents architectural elements from Classical and Hellenistic structures, many repurposed in later constructions. This emphasis on advanced mapping and meticulous recording of existing materials exemplifies a forward-thinking approach to archaeological research, setting a standard for future projects by integrating modern technology with traditional fieldwork. Excavations focused on a stoa-like structure near (and partially under) the Basilica C, where vessels such as pithoi and trefoil jugs suggest liquid storage. Measuring 4.5 metres in width and at least 8.5 metres in length, the structure features interior beam sockets and preserved iron fittings that suggest the presence of doors or trapdoors. Within subterranean space, a variety of vessels were discovered, including clay plates, cups, large pithoi (storage jars), and impressive trefoil jugs, likely used for storing liquids such as wine. A major 2022 find was a cuirassed statue torso (Fig. 5.6), intricately decorated with a victory trophy, Nike, and a bound captive, likely from the Augustan period. A similar torso, discovered in the 1970s at the Marmario tower, reinforces the region’s use of imperial imagery.

Fig. 5.6. Cuirassed statue Amphipolis. © Ephorate of Antiquities of Serres.

The excavation at the low hill of Paliokastro Terpni – near the modern village of Terpni (Tserpista) in the municipality of Bisaltia (Nigrita), located in the lower valley of the Strymon River – was undertaken by the French School at Athens in collaboration with the Ephorate of Serres. Malamidou et al. (Reference Malamidou, Martinez-Sève, Bastide, Blond, Boubounelle, Chalazonitis, Crépy, Déderix, Delahaye, Guay, Lucas, Ralli, Rizos, Tzankov and Zidarov2023) and Boubounelle et al. (Reference Boubounelle, Chalazonitis, Guillaume, Malamidou, Martinez-Sève, Ralli, Rizos and Rueff2024), has set similar objectives with a strong focus on geospatial tagging and digital mapping (ID 19750; 18550). This approach aims to build on earlier findings from a brief excavation campaign in the 1990s (Karamberi 1994: fig. 190c; Reference Karamberi1999), which uncovered a large five-aisled basilica near a thermal bath complex, dating from the second to mid-fourth centuries CE, with evidence of reoccupation into the sixth century CE. Earlier levels, particularly from the Hellenistic period, were also revealed. Pottery finds indicate that the hill may have been inhabited as early as the sixth century BCE. An inscription from the second–third century CE suggests that the settlement was a polis, although its name is unknown. The investigations, conducted across three main zones, have revealed significant architectural, ceramic, and metallic finds that illuminate the site’s stratigraphy and community activities. Zone 1 revealed mudbrick and stone domestic structures with pottery, tools, and storage pits, indicating economic activity from the Classical to Early Christian periods. Zone 2 exposed a well-preserved defensive wall with habitation layers, yielding coins, ceramics, and an iron arrowhead. Zone 3 revealed a three-aisled Christian church with an opus sectile floor (Fig. 5.7) comparable to those at Philippi and Amphipolis, and finds dating its use to the fourth–seventh centuries CE. Earlier walls suggest a pre-existing structure. The discovery of two churches – the Zone 3 basilica and another found in 1993 (see above) – highlights the site’s religious importance (Boubounelle, Chalazonitis and Ralli Reference Boubounelle, Chalazonitis, Ralli and Ralli2024). Architectural, ceramic, and numismatic evidence point to a prosperous settlement, with future research aiming to refine its chronology and regional significance.

Fig. 5.7. The EC basilica at Terpni, Serres. © Ephorate of Antiquities of Serres.

The discoveries at Terpni highlight urban development in small cities across the province, and the same sophistication can be found in other areas, such as the incredible domestic elite residence that was found near Lake Vegoritida (Ziota Reference Ziota2022: 379). Excavated by Panikos Chrysostomou (Ephorate of Florina) (Reference Chrysostomou2018), this second-century CE mansion covered more than 1.2 acres and featured 96 rooms, corridors, baths, and courtyards. Lavish interiors included multi-coloured marble, statues, and mosaics spanning 360m2. Notable spaces include the so called ‘Europa Hall’, with mythological mosaics and an inscription naming the owners, Alexandros and Memmia, and the so called ‘Nereids’ Hall’, a grand reception space adorned with mosaics of sea nymphs (Fig. 5.8), dolphins, and seasonal personifications. The villa also housed statues of Hermes, Athena, and Poseidon, a stele dedicated to Zeus, and various luxury artifacts. Another hall, the ‘Beast Warrior Hall’, is named from a mosaic of a lion attacking a man. The villa’s opulence provides valuable insights into elite Roman-period lifestyle, underscoring the widespread presence of grand residences in rural Macedonia, even in places far from large urban areas like the area of Lake Vegoritida. However, distinguishing between true villas and high-status peri-urban estates remains a challenge.

Fig. 5.8. Mosaic detail from Villa Alexandros, Amyntaion. © Ephorate of Antiquities of Florina.

Similar to the area of Amyntaion, Vegoritida, the excavation led by Dimitris Damaskos (University of Patras) and D. Plantzos (National Kapodistrian University of Athens) uncovered a remarkable public building in Upper Macedonia (Fig. 5.9), possibly serving as an assembly hall for the tribal centre of the Orestai. This well-preserved structure consists of an apsidal assembly hall (17.5 × 12m) and a larger, rectangular colonnaded court (52.4 × 33.2m). The interior, in the form of a basilica with an apse and built benches along the walls, was richly decorated. Excavations revealed fragments of high-quality marble veneer from various sources, including verde antico, Thasian, Chian, and Prilep marble, reflecting the architectural refinement of this remote region.

Fig. 5.9. Ballon photo of the building – assembly hall at Argos Orestikon. © Dimitris Damaskos, University of Patras.

The work in Upper Macedonia underscores the progress made on new sites and highlights the diffusion of urban forms and architecture across diverse settings within the province. It suggests a more widespread adoption of empire-wide architectural models, extending beyond major urban centres into smaller regional hubs.

Work and research on rural sites

The execution of large-scale public works, such as the TAP, has provided opportunities for excavations in areas outside urban centres, bringing to light significant data on the organization of the rural landscape and life beyond the major cities of the province. A substantial portion of these findings pertains to cemeteries, typically small to medium in size, with burial numbers ranging from 10–50 to 120–150 graves.

These cemeteries, such as the Late Roman cemetery of 45 burials that was discovered at Kleitos in Kozani and recently published (Vrachionidou Reference Vrachionidou2017), are often not definitively associated with nearby settlements. Some of these burial sites have been tentatively linked to villas or large agricultural installations, but others, like the above-mentioned in Kleitos, seem to relate to settlements that have not been discovered yet. However, research on these cemeteries has, understandably, concentrated primarily on the study of grave goods. This focus provides valuable insights into burial practices, material culture, and social structures within the rural context of Roman Macedonia; yet, there remains considerable potential to further explore the relationship between these cemeteries and their associated communities, as well as the broader economic and social networks in which they operated.

Two recently researched cemeteries that provide key insights into rural burial practices during the second and third centuries CE are the cemeteries at Theodosia and Isoma at Kilkis (Keramaris et al. Reference Keramaris, Kotzampopoulou, Daraviga, Avgeros and Lazopoulou2017; Skartsis Reference Skartsis2021: 145–49). The Theodosia cemetery (250m2) contained 48 graves, including tile-roofed, pit, and kalyvites (tile-covered tomb type) graves, with cremation as the dominant rite (Fig. 5.10). Grave goods – pottery, glass vessels, jewellery, and over 600 coins, often in leather pouches (Fig. 5.11) – reflect burial customs and economic ties in this semi mountainous rural community. The neighbouring, and larger, third-century CE Isoma cemetery (600m2) featured 42 burials, mainly pit and tile-covered graves, with a notable marble cist grave. Cremations were common, and offerings included pottery, jewellery, and a rare gold aureus of Severus Alexander (222–35 CE). The built cist grave stood out for its elaborate construction with fine marble slabs. Grave goods included pottery (skyphoi, cups, oinochoe), glass vessels, coins, and jewellery, such as gold earrings and bronze bracelets (Fig. 5.12). The cremation practices and grave goods in both cemeteries reflect rural communities’ cultural and economic ties to the Roman Empire. Similarities with urban burial customs, including the use of coins, pottery, and jewellery, highlight the integration of these populations into broader Roman traditions.

Fig. 5.10. Photo of the Roman cemetery at Theodosia Kilkis. © Ephorate of Antiquities of Kilkis.

Fig. 5.11. Coin hoard from the same cemetery. Bronze coins hoard. The horn cap of the leather pouch has survived, in Skartsis Reference Skartsis2021: 153, fig. 10–11. © Ephorate of Antiquities of Kilkis.

Fig. 5.12. Silver spoon, pendants, and ring from the Roman cemetery at Isoma, Kilkis, © Ephorate of Antiquities of Kilkis.

Similar small cemeteries, typically dated between the second century CE and Late Antiquity (fifth and sixth century CE), have been found along the course of the pipeline, including sites at Nea Mesimvria (Skartsis Reference Skartsis2021: 163–65) in Thessaloniki (21 graves covering 225m2, Fig. 5.13), Drymos in Thessaloniki (Panti Reference Panti2022: 248; see Fig. 5.14), Assiros (Panti Reference Panti2022: 248), Lipochori in Pella, Peristerias in Pentapoli Serres (Skartsis Reference Skartsis2021: 136), Symvoli in Serres (74 burials pit graves; see Malamidou, Malama and Pylarinou Reference Malamidou, Malama and Pylarinou2022: 443–44), and Vasileiada in Kastoria (Sarigiannidou Reference Sarigiannidou2022: 426). The level of material culture varies, ranging from relatively modest yet well-furnished cemeteries, such as that of Nea Mesimvria, where 19 of the 21 graves contained grave goods, to much simpler and poorer burial sites such as Lipochori in Pella. The cemetery at Peristerias, dating to the third–fourth centuries CE, consisted of 10 graves (eight pit graves and two cist graves) that utilized natural rock cavities. The skeletal remains were poorly preserved, and the modest grave goods – including oinochoai, cups, and coins issued by emperors from Probus (276–82 CE) to Constantius II (337–61 CE) – reflect a lower level of material culture.

Fig. 5.13. Triple burial in the cemetery of Nea Mesimvria. © Ephorate of Antiquities of Thessaloniki region.

Fig. 5.14. Grave finds from the LR cemetery at Drymos. Thessaloniki. © Ephorate of Antiquities of Thessaloniki Region.

Excavations continue to reveal Roman phases in areas previously thought unlikely to yield significant Roman artifacts. One notable discovery is a cemetery with 57 graves (first–fourth century CE) near Platamonas (ancient Heraclea) at the Goritsa hill (Papadopoulou, Koromila and Karagianni Reference Papadopoulou, Koromila and Karagianni2015; Gatzolis Reference Gatzolis2022: 252). The site, with continuous habitation and proximity to the Hellenistic farmstead of Tria Platania (Gerofoka Reference Gerofoka2016), features mostly simple pit burials. Only two constructed tombs were found, with modest grave goods, including ceramic cups, glassware, and coins from local mints (Thessaloniki and Dion), often found in hoards. This cemetery clearly belongs to a modest community, yet it demonstrates remarkable resilience over time, suggesting, if nothing else, a stable and enduring economy.

Research on rural settlements and land use is advancing through studies such as Kostas Ketanis’ (University of Thessaly) doctoral research (Reference Ketanis2024), which synthesizes data on northern Greek villas, shedding light on land organization, labour, and architectural complexity. Smaller settlements are revealed through rescue excavations, such as those near the Roman colony of Philippi. Excavations during the construction of the TAP (Skartsis Reference Skartsis2021: 87–95) uncovered three modest dwellings (first–second century CE) with timber roofs, suggesting a small rural cluster rather than a vicus (Fig. 5.15). Their alignment and proximity to a cobbled road, possibly linked to the Via Egnatia or the nearby vicus of Satriceni (Collart Reference Collart1930), indicate pre-existing infrastructure. Earlier road use and a grave from the Hellenistic period suggest that Roman settlers integrated into an already-inhabited landscape.

Fig. 5.15. Aerial view of rural building I at Philippi. © Ephorate of Antiquities of Kavala.

Finds like those at Philippi highlight the gaps in our understanding of rural organization. However, new discoveries, such as the Kalamonas site (Skartsis Reference Skartsis2021: 121–27) near Via Egnatia, reveal a well-structured countryside with artisanal activity dating back to the Hellenistic period. Excavations uncovered a pottery workshop (Fig. 5.16) serving settlements west of Philippi until the fourth century CE, including a kiln, clay processing facilities, and storage pits. Notable finds include moulds with vegetal and narrative motifs, such as Euripides’ Iphigenia in Aulis, one inscribed with the potter’s name ‘Simos’. The remarkable longevity of its function reflects the enduring needs of a rural society that, despite the challenges faced by every farmer, was able to sustain the demand for such an artisanal site.

Fig. 5.16. Kalamonas, Hellenistic workshop. Stone bench. © Ephorate of Antiquities of Drama.

Similar Late Roman sites have been uncovered in rural Macedonia, including one in Kilkis at the site Koronouda (third–fifth century CE; see Keramaris and Farmaki Reference Keramaris and Farmaki2016), near Nea Zichni in Serres (Skartsis Reference Skartsis2021: 134), Vasileiada in Kastoria, and Karteres in Thessaloniki (Skartsis Reference Skartsis2021: 270), where an installation containing millstones, loom weights, and spindle whorls has been interpreted as a tannery dating from the first century BCE to the first century CE. The precise function of these spaces remains uncertain – whether they were part of settlements, shared facilities serving multiple communities, or belonged to large agricultural estates is still debated. These discoveries continue to illuminate the complexity of rural economic and social structures, challenging the conventional model of the villa economy.

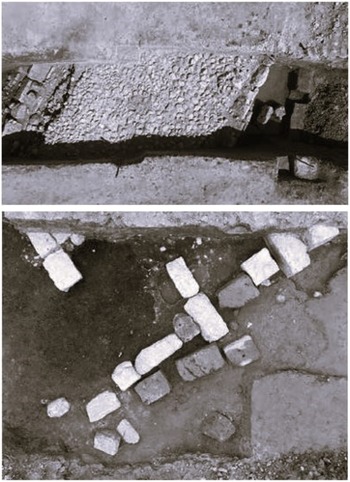

The excavations revealed not only settlements and sites but also significant road infrastructure, including a well-preserved Late Roman road and bridge near Paralimni in the Giannitsa region, 6km southwest of ancient Pella (Skartsis Reference Skartsis2021: 179–81). The 7m-wide road (Tsigarida et al. Reference Tsigarida, Georgiadou, Zambiti and Stalidis2022: 293–94), dating to the late fourth–early fifth century CE, featured a pebble surface supported by curbs of large stone blocks and incorporated water runoff engineering (Fig. 5.17). Nearby, a monumental arched bridge over the Loudias River was partially excavated, revealing ashlar blocks and associated artifacts such as pottery and coins from the same period. This remarkable find demonstrates that even local roads, not directly linked to the Via Egnatia but serving regional needs, were carefully constructed and maintained, even during periods of instability such as the early fifth century CE.

Fig. 5.17. Paralimni GIannitsa. Late Roman road. Layer of fallen blocks from the Late Roman bridge. © The credits on the depicted monument belongs to the Ministry of Culture (Ν. 4858/2021). Ephorate of Antiquities of Pella-Hellenic Ministry of Culture | Hellenic Organization of Cultural Resources Development.

Landscapes

The most valuable insight gained from these excavations is the realization that many sites – likely settlements – such as Antigonos and Philotas in Florina, Pyrgoi Omaloi in Kozani, and the site of Paralimni in Pella (adjacent to the former Lake Giannitsa; see Georgiadou et al. Reference Georgiadou, Eleutheriadi, Ioannidou and Lothetidou2024), exhibit continuous diachronic habitation. This enduring occupation underscores the stability and adaptability of rural communities, revealing a landscape where settlements thrived for centuries despite political and economic fluctuations. It points to a resilient rural economy, where agricultural production, artisanal activities, and infrastructure were sustained and adjusted to meet evolving needs. Rather than a countryside marked by abandonment or decline, these findings highlight the long-term viability of rural life in Macedonia. The overall picture that emerges is far denser and more dynamic than the idyllic vision of grand villas suggests. The landscape was interwoven with cobbled roads, small cemeteries, agricultural installations, and settlements of varying sizes, many with deep historical roots. Workshops and industrial facilities further emphasize a countryside that was not empty but vibrant, serving as the economic and social backbone of the region. Archaeological discoveries across Macedonia, far from major urban centres, reveal a rich and continuous history of occupation. While a full account of these findings is beyond the scope of this report, several key sites stand out. Near the course of the Egnatia in Florina, excavations uncovered a fortified hamlet from the time of Cassander (305–297 BCE), occupied until the third century CE (Ziota Reference Ziota2022: 378–79). Nearby, Roman-period farms were built atop a cemetery with an extraordinary continuity from the Bronze Age to Byzantine times (Ziota Reference Ziota2022: 381). Investigations near the Ilarion dam have revealed a high density of sites, many bridging the Hellenistic and Roman periods. Among them is an Early Christian villa near Velventos (Chondrogianni-Metoki Reference Chondrogianni-Metoki, Antonopoulou and Petrounakos2022: 304), perched above the river and displaying remarkable architectural sophistication. South of Philotas, excavations uncovered a large Late Roman peristyle building (27m2), while a nearly 2-km zone teems with domestic and artisanal sites, including evidence of wine production and iron ore processing (Tsiokanou Reference Tsiokanou2022: 398).

With advancements in interdisciplinary research, particularly approaches that integrate multiple fields and expertise, we now have the opportunity to move beyond conventional models of rural countryside organization and economy. A prime example is the recent integrated geoarchaeological survey in Grevena and Upper Macedonia (Apostolou et al. Reference Apostolou, Mayoral, Venieri, Dimaki, Garcia-Molsosa, Georgiadis and Orengo2024), which combines remote sensing, geomorphological mapping, litho-stratigraphic analysis, radiocarbon dating, and archaeological fieldwork to provide new insights into the region’s landscape and human activity during the Roman period. The survey has revealed that numerous short-lived sites, dating from the second to fourth centuries CE, emerged in the countryside of Grevena (Apostolou et al. Reference Apostolou, Mayoral, Venieri, Dimaki, Garcia-Molsosa, Georgiadis and Orengo2024: 18). These were primarily farmsteads established in previously unexploited areas, indicating a reorganization of the landscape and an increase in agricultural activity. Pollen records from nearby lakes (Orestias, Prespa, and Doiran) point to significant human-induced environmental changes, including the expansion of cereal cultivation, a reduction in woodland coverage, and extensive landscape clearance for agropastoral practices. In areas such as Agios Georgios and Xerolakkos, the Roman period saw the highest density and distribution of sites (Apostolou et al. Reference Apostolou, Mayoral, Venieri, Dimaki, Garcia-Molsosa, Georgiadis and Orengo2024: 20).

Interestingly, this period of intensified settlement and land use coincides with soil formation and reduced alluvial deposition in floodplains, suggesting the implementation of effective land management strategies such as terracing to control soil erosion and runoff (Apostolou et al. Reference Apostolou, Mayoral, Venieri, Dimaki, Garcia-Molsosa, Georgiadis and Orengo2024: 18–20). The proliferation of rural sites and the intensification of agricultural activity likely reflect an economic reorganization aimed at optimizing productivity to meet both local and supra-regional market demands. This may have involved improved agricultural techniques and strategies to ensure surplus crop production.

These findings align with broader patterns of Roman economic and agricultural expansion, highlighting the integration of Upper Macedonia into the empire’s economic network and demonstrating the dynamic adaptation of its rural landscape. Meanwhile, new bioarchaeological approaches allow us to gain deeper insights into the living conditions of people in rural areas (Ganiatsou et al. Reference Ganiatsou, Vika, Georgiadou, Protopsalti and Papageorgopoulou2022). A series of studies from the University of Groningen (Vergidou Reference Vergidou2024) is shedding light on the dietary habits and social dynamics of ancient populations, particularly the ‘common’ people, whose lifestyles are often overlooked due to limited or biased textual evidence. By combining macroscopic analysis, palaeopathology, and stable isotope analysis of human skeletal remains, this research provides valuable data on dietary variation within two Roman Macedonian communities: Pontokomi-Vrysi and Nea Kerdylia Strovolos. The findings emphasize how local micro-ecological factors and region-specific agricultural practices influenced food choices, with no significant dietary differences observed based on sex or age within these communities. Special mention should also be made of the ERC-funded Laboratory of Biological Anthropology (https://anthropologylab.classic.duth.gr) in Komotini whose research focuses, among other topics, on the skeletal remains and nutritional habits of the inhabitants of Roman Thessaloniki.

Epilogue

Despite the setbacks and challenges of the COVID-19 period, the past decade proved remarkably productive for archaeology in the region. It allowed for a deeper exploration of urban complexes such as Thessaloniki, a more nuanced understanding of the rural landscape – revealed to be far denser and more complex than the traditional image of a sparsely populated countryside dominated by isolated villas – and a significant embrace of advanced mapping technologies. These developments not only enriched current interpretations but also opened promising new avenues for future research.