Introduction

China's history of the last 200 years has been tortuous and paradoxical. During the 19th century and first half of the 20th, China suffered the ‘century of humiliation’, a period of foreign intervention, subjugation, break up and loss of sovereignty which culminated with the Japanese invasion. After Mao Zedong's victory in the civil war against the Kuomintang and the foundation of the People's Republic of China (PRC), the country slowly began to emancipate from this humiliating past. Although the premises for Chinese rise were set by the series of political and economic reforms inaugurated by Deng Xiaoping, it was not until the early 2000s that China consolidated its ‘great power’ status. Today, China is the second greatest world power, with the second economy (World Bank, 2019) and the largest military of the world (IISS, 2019).

As patent challenger of the US-led international order China is currently pursuing a multifaceted revisionist strategy that affects the economic, infrastructural, cultural, diplomatic, and military domains. China's revisionism entails the creation of international institutions and standards alternative to US-led ones. The aim is to promote a more balanced distribution of global power in the frame of the overcoming of post-Cold War unipolarism. Revisionism in the economic and finance sector includes the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), the BRICS-led New Development Bank (NDB), the BRICS Contingency Reserve Agreement (CRA), the global infrastructure to internationalize the yuan, China International payment system (CIPS), China Union Pay, the Shanghai Global Financial Center (GFC), the Universal Credit Rating Group, the Chiang Mai Initiative Multilateral (CMIM), the ASEAN + 3, and the ASEAN + 3 Macroeconomic Research Office (AMRO). The trade and investment sector contemplates the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) and the Free Trade Area of the Asia Pacific (FTAAP). The infrastructural sector comprises long-term projects like the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), the Nicaragua Canal, and the Trans-Amazonian Railway. The cultural sector aims at spreading through a soft power strategy the knowledge of Chinese language, history, and civilization with the Confucius Institutes. The diplomacy sector embraces the BRICS Leaders Summits, the BRICS and IBSA working groups, and the Boao Forum for Asia (BFA). Finally, the security sector takes account of the Conference on Interaction and Confidence Building Measures in Asia (CICA), the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), and the BRICS national security advisors (NSA) meeting.

Washington's most recent strategic documents, including the 2017 National Security Strategy of the United States and the 2021 Interim National Security Strategic Guidance, stress their concern vis-à-vis Beijing's attitude and overtly classify the PRC as a ‘revisionist’ (White House, 2017) and ‘more assertive’ power (White House, 2021).

In considering the military sphere, in the last 20 years China has enhanced a significant naval buildup. History teaches that great power status implies naval buildups: this has been confirmed throughout modern history by the strategies pursued by all major empires including Spain, Portugal, Holland, France, England, Russia, Germany, the United States (US), and Japan.

This article aims at explaining Beijing's naval build up through a geopolitical perspective, speculating that the PRC's naval military development does not trace the naval strategy exposed by Admiral Mahan, namely a quest for global supremacy based on the emulation of the maritime primacy of the hegemon, but instead recalls Admiral Tirpitz's ‘risk theory’ strategy focused on naval buildup for local power projection aimed at deterring and counterbalancing but not replacing the hegemon. In other words, the study posits that the PRC does not wish to replace the US as world maritime hegemon – an objective that Beijing views as neither feasible nor desirable – but rather to counterbalance the US presence in the Pacific, a region of the uttermost importance for Chinese national interest. This would in turn suggest that, since it does not have the capabilities to overtly challenge the US global maritime power, China is pursuing a defensive, limited in scale naval strategy still aimed at a broader revisionist strategy – not on a military-tactic level but on an economic, infrastructural, and diplomatic one, using A2/AD strategies to preserve its areas of interest, avoiding external interference. To substantiate this hypothesis, the article compares in a diachronic fashion contemporary Chinese naval arms race, from the early 2000s to present, with the buildup of Wilhelmine Germany's High Seas Fleet (Hochseeflotte) between 1907 and 1914 vis-à-vis the British Royal Navy. Following Tirpitz, who believed that concentrating a powerful and threatening German battle fleet in the North Sea would compel the Royal Navy to disperse its forces around the British Empire to achieve an Anglo-German balance of force, China is upgrading its fleet to demonstrate sea power in the Pacific and to foster A2/AD strategies against the US, where Beijing's interests and claims are present.

The article is divided as follows. The first section offers a literature review on naval buildups from an International Relations (IR) perspective, questioning what aspect could best explain Chinese contemporary naval strategy. The second section exposes the theoretical postulates of Mahan's naval strategy stressing on its relevance for global hegemony and compares them with Tirpitz's regional strategy based on ‘risk theory’. The third section traces the modes of Wilhelmine Germany's and China's naval buildups, showing how in both cases similar behaviors that recall Tirpitzian naval strategy have occurred. Finally, the conclusions underline the theoretical and empirical findings of the research, arguing that an unrestrained Chinese naval buildup could encourage arms races and direct confrontation due to regional security dilemmas, as occurred between Britain and Germany with the outbreak of World War One.

Investigating the roots of China's naval buildup: quest for world hegemony or regional security concerns?

Since the launch of market reforms, China's economy has grown at unparalleled levels and forecasts suggest that over the next 10 years China could become the leader in the world economy (Bloomberg, 2021). In tandem with its outstanding economic growth, Beijing decided to significantly increase its military spending, allowing it to acquire the technology required to develop sophisticated land, sea, and air power. Since President Obama's ‘Pivot to Asia’ and, above all, President Trump's Chinese strategy, Beijing's simultaneous economic and military growth has been viewed by Washington as a ‘great power rivalry’, depicting China as a typical challenging latecomer. Several scholars of security studies portrayed China's rise to ‘great power’ status as a replica of Wilhelmine Germany's (Friedman, Reference Friedman and Lieber1997), even if others have rejected this comparison (Kang, Reference Kang2013; Shambaugh, Reference Shambaugh2013; Acharya, Reference Acharya2014). The debate between supporters and opposers of China's alleged Mahanian strategy is intense (Holmes and Yoshihara, Reference Holmes and Yoshihara2012; Dossi, Reference Dossi2013, Reference Dossi2014). But why do rising powers pursue arms races and naval buildups? IR scholarly debate suggests different hypotheses.

From a constructivist perspective, Murray (Reference Murray2010) argues that states carry out naval programs not for strategic reasons, but to ensure the recognition of their identity as world powers. States would need a solid identity to be top actors in world politics and securing identity would imply the need for a strong military. In this sense, China would implement naval power to be identified collectively as a ‘great power’. Some studies (McNeely, Reference McNeely1995; Katzenstein, Reference Katzenstein1996) have outlined a connection between state identity and weapon proliferation, claiming that a criterion for being recognized as a sovereign state by the international community is the ability to preserve territorial integrity and political independence through military might. Other works (Byman and Pollack, Reference Byman and Pollack2001) note that the identity and personality of leaders and their governing style could also contribute to shaping foreign policy decisions. The effects of individual personalities would matter more when power is concentrated in the hands of smaller groups of individuals, like in China, who can control over the foreign policy-making apparatus.

Connected to the explanation centered on recognition, another strand of the literature (Kagan, Reference Kagan1995) posits that naval expansion would be driven by the pursuit of prestige, power, and glory at all costs. Powerful navies have always represented national greatness and a source of international prestige. This argument combines the self-perceived greatness of the Chinese nation with the need for projecting Chinese power through military means. Specifically, Chinese prestige involves the need to delete also through military buildup any reminiscence connected to the shame inflicted by the ‘century of humiliation’.

On the contrary, offensive realists like Mearsheimer (Reference Mearsheimer2001) claim that naval programs reflect a power-maximizing foreign policy intended to augment a state's relative power in the international system. Providing for their own survival, states would be continuously seeking for ways to maximize their relative power to assure their security. However, any act of power maximization like an arms race should be pursued only if the security benefits of arming would outweigh the risks. In this sense, in an anarchic world China would have little choice but to emulate the US by building a powerful navy and consequently Chinese naval buildup would be driven primarily by security concerns (Layne, Reference Layne1993). On the other hand, defensive realism considers other features that could explain naval buildup like offence–defense balance and the security dilemma trap (Taliaferro, Reference Taliaferro2000). The uncertainty stemming from the security dilemma would lead a state to remedy to its relative weakness vis-à-vis a stronger state through the development of its own strength to reach an offence–defense equilibrium. In this respect, China's naval buildup would follow a defensive scheme to create a balance between its power projection and that of the US and its allies in the Pacific.

However, neo-liberals underscore the cooperative aspect when analyzing states' actions. Cooperation, which is implemented within the frame of international regimes or multilateral institutions, would outweigh the benefits of self-help in a win–win scheme. In this frame, Rozman (Reference Rozman2011) claims that, despite its military development, China would only be interested in fostering multilateralism and upholding its economic interests. The Chinese military would thus serve the peaceful purpose of coordinating China's economic and political objectives.

Another interpretation (Sheehan, Reference Sheehan1968) suggests that foreign policy cannot be understood by omitting the impact of domestic political factors. Self-centered groups within the state would seize the foreign policy-making process for pursuing their private interests. China's naval construction would thus serve the interests of heavy industry and shipbuilding companies.

Moreover, Ross (Reference Ross2009) depicts Chinese naval buildup as an example of ‘naval nationalism’. He argues that, like in the case of land powers of the past seeking for ‘great power’ status, nationalism more than security plays the pivotal role in shaping China's naval ambition. Naval nationalism is described as a manifestation of nationalist ‘prestige strategies’ pursued by the governmental apparatus to achieve greater domestic legitimacy and bolster inner consensus. Naval nationalism would be responsible for encouraging land powers to pursue strategies aimed at forging or incrementing sea power. Historically, nationalism and a perception of grandeur would have driven the French naval buildup in the 1860s. Likewise, nationalism would have led Imperial Germany's naval arms race vis-à-vis Britain and Japan's simultaneous pursuit of continental and maritime power in East Asia in the early 20th century. Today, China is following the same scheme – albeit reversed – followed by Japan a century before (Natalizia and Termine, Reference Natalizia and Termine2021) by combining land power with sea power and naval nationalism would explain this trend.

Instead, Chang (Reference Chang2018) views China's naval strategy as an example of ‘naval diplomacy’ aimed at implementing the Maritime Silk Road (MSR) within the frame of the BRI. Naval diplomacy would represent a non-warfare military strategy aimed at settling international disputes and upholding a state's national interests. A close concept would be the one known by traditional naval history as ‘gunboat diplomacy’. The core of naval diplomacy would rest both on dissuasive strategies aimed at averting a third party from taking an action and on more coercive strategies designed to encourage a third party to pursue an action. Naval diplomacy would also be closely linked to a coastal defense strategy for the purpose of regional security, especially in relation to the ‘first island chain’. Therefore, the role of the navy would be to uphold national unity and territorial integrity, deal with potential regional conflict, and avert threats originating from the oceans. Finally, naval diplomacy would be a tool for implementing the MSR, since it would help to solve international controversies – for example, maritime zone delimitation – through peaceful means while ensuring sea lanes' safety.

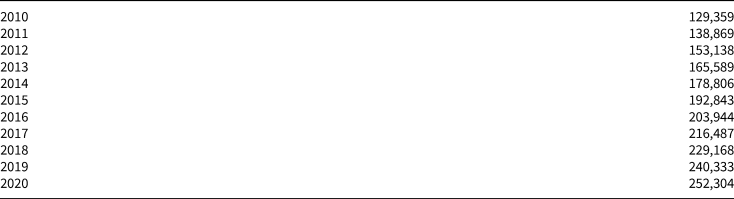

Lastly, the literature on revisionist powers may offer contributions to understand China's naval buildup. International or regional stability is usually altered by the dynamics of power shift, which generates potential dissatisfied challengers that seek to confront the existing status quo. Scholarly debate regarding challengers' dissatisfaction tend to match with China's political strategies, including naval buildups. Kim (Reference Kim1991) and Lemke and Werner (Reference Lemke and Werner1996) maintain that dissatisfaction with the status quo is a more important marker of war than the balance of power. In recent years, China's leadership has directed the People's Liberation Army (PLA) to improve its combat readiness, while it is increasingly evident that the intensity of the PLA's training and the complexity and scale of its exercises is aimed at military revisionism (US Secretary of Defense, 2020). Moreover, Carr (Reference Carr1939) underlines how dissatisfied powers tend to reject the status quo maintained by the satisfied powers through military expenditures. As Table 1 shows, China's military expenditure, which is estimated to have increased of 76% over the decade 2011–2020 (SIPRI, 2021a, 2021b), seems to confirm this thesis. According to power transition theories (Organski and Kugler, Reference Organski and Kugler1980), military revisionism is a typical aspect that characterizes power shifts. Finally, Lemke and Reed (Reference Lemke and Reed1998) link dissatisfaction to the need of crafting alliances. The formation of the Chinese-led SCO, an organization that implies military cooperation, confirms the use of alliance crafting as a tool used by a challenging actor dissatisfied by the status quo.

Table 1. China's military expenditures between 2010 and 2020 in US$ m

Source: SIPRI database on military expenditure by country (2021).

Mahan vs. Tirpitz: theories of sea power projection for maritime hegemony and naval revisionism

The division posited by classical geopolitics describes history as a continual struggle between thalassocracies and tellurocracies (Mackinder, Reference Mackinder1919; Schmitt, Reference Schmitt1942; Pizzolo, Reference Pizzolo2020). The Anglo-Saxon geopolitical approach stressed two fundamental principles: firstly, strategists like Alfred T. Mahan highlighted the primacy of sea power for world hegemony and, secondly, thinkers like Halford J. Mackinder alerted on the perils that sea power would face if land power would acquire an overwhelming continental might. Specifically, Mahan's naval theory postulated that national greatness was indissolubly associated with the rule of the seas, with their commercial use in peacetime and their control in wartime, emphasizing the role of strategic locations and the importance of the fighting power of fleets (Crowl, Reference Crowl, Paret, Craig and Gilbert1986). Mahan's influence in Wilhelmine Germany became paramount: Kaiser Wilhelm II ordered to instruct the German navy officers to study Mahan's works on sea power and Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz used Mahan's strategic thinking to justify the construction of Germany's blue-water fleet – in the same way that Karl Haushofer made use of Mackinder's Heartland theory to justify Germany's continental expansion.

Mahan's hegemonic naval theory

In the fundamental work The Influence of Sea Power upon History, 1660–1783, Admiral Mahan offered the theoretical premises for shaping a nexus between IR, naval power, and world power status (Mahan, Reference Mahan1890). His theory of naval power was aimed at crafting world hegemony. He believed that the complete control of the world's oceans, sea lanes and maritime trade routes along with a powerful fleet would lead to world hegemony. However, he also stated that the potential hegemon should have integrated the possession of a mighty battle fleet with an extensive network of overseas bases, colonies, and depots to operate globally. In acknowledging the opposition between land powers and sea powers, Mahan argued that the latter were by their nature more powerful and privileged.

Mahan's theoretical thoughts stemmed from the historical analysis of Britain's Royal Navy, which he conceived as the model that the nascent US Navy should copy. Mahan viewed Britain as an insular power detached from the rest of Europe, which, during its historical evolution, turned seaward for deterrence and survival (Matzke, Reference Matzke2011: 8). The command of the sea offered Britain the predominance of commerce through the projection of maritime force. Britain's ascension to ‘great power’ status was the consequence of the protection by the Royal Navy of the flow of commerce originating from international sea trade routes. During the 18th and 19th centuries, Britain ensured the command of the seas through its navy, some insular naval bases scattered throughout the globe, and the possession of strategically located colonies.

Following a typical social Darwinist scheme, Mahan believed that the hierarchy of states was constantly in fluctuation and that power competition led to the rise of some states and the decline of others (Kagan, Reference Kagan1995: 135). In this context, naval power represented the pivotal factor for achieving world power status. The essence of naval power was enshrined by the possession of battleships, conceived as floating symbols to ‘demonstrate superiority to domestic and foreign audiences’ (Rüger, Reference Rüger2007: 208). Battle fleets thus came to indicate the political power of the state and the national identity of a population, embodying both world power status and relevance in world affairs (Murray, Reference Murray2010: 666). The Mahanian naval strategy implied that the possession of a noteworthy battle fleet was a precondition to becoming a world power and a respected actor in IR. According to Mahan, sea power rested on the indivisible links of internal development and production, peaceful shipping, and overseas colonies (St. John, Reference St. John1971: 75).

Mahan observed that only those nations with secured internal borders could exercise sea power projection, whereas land powers with insecure internal borders were always exposed by inner threats that impeded complete maritime rise. In crafting their sea power, nations were affected by the nature of their neighbors: a nation that was not forced to defend itself or protect its frontiers by other land powers bore a clear advantage that translated into the possibility of developing sea power (Mahan, Reference Mahan1890: 51). In other words, history demonstrated that a state with even a single continental frontier was disadvantaged to compete in naval development compared to a full-fledged insular power like Britain (Ross, Reference Ross2009: 48). In this regard, land powers like Germany confronted strategic challenges emanating from inner threats to their border security, especially when boundaries were not clearly delimitated by ‘natural frontiers’. On the other hand, Mahan believed that full-fledged sea powers like Britain or Japan enjoyed advantageous geographical-political features like internal border security and effortless access to the seas. After having secured its continental borders vis-à-vis Mexico and British Canada, the US could enjoy the benefits of insularity, which assured its rise as maritime power. In the late 19th-century, the US could turn from a land power to a sea power due to several fortunate factors: the consolidation of domestic stability following the Civil War; the fulfilment of the ‘Manifest Destiny’ with the conquer of its western territories and the adjoining of the Atlantic with the Pacific shores; the neutralization of any potential threat on its northern and southern borders; and the control of insular bases in the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans after the Spanish–American War. Unlike successful sea powers like Britain, Japan or the US, European land powers like France, Germany, or Russia were always threatened by challenges stemming from their continental borders.

In emphasizing the crucial role of the sea lanes for the transport of commodities and the relation between the wealth of nations and their maritime assets, Mahan believed that the decisive strategic goal of naval power did not rest upon a sea-denial strategy but rather upon a sea-control one. Whereas sea-control entails the capacity of a nation to interrupt economic and military maritime activities of a hostile nation while maintaining its own, sea-denial consists in the ability of a nation to interrupt all activities of a foe without maintaining its own (Wiegand, Reference Wiegand2008: 7).

Mahan viewed the world's oceans as the economic and geo-strategic big spaces where much of global trade was conducted (Mahan, Reference Mahan1890: 25). In this context, the navies represented a crucial tool for oceanic nations to safeguard their commerce. To become credited maritime powers, states had to be situated on or close to the sea, possess a network of commercial harbors, and enjoy a wide territorial and colonial extension (MacHaffie, Reference MacHaffie2020: 2). At the same time, to be a successful maritime power, a nation was affected by its demographic growth, its national character, and its form of government (Mahan, Reference Mahan1890: 61–75).

Tirpitz's anti-hegemonic ‘risk theory’

Admiral von Tirpitz, Secretary of State of the German Imperial Navy from 1887 to 1916, promoted an alternative maritime strategy to Mahan's that focused on regional sea power. Unlike Mahan, Tirpitz theorized his naval power postulates from Germany's perspective, that is from the view of a rising, challenging power and not a hegemon. While Mahan considered the Royal Navy a force that the US should emulate to achieve global hegemony, Tirpitz conceived it as a vital menace.

Tirpitz perceived his naval building program as more than just a military tool. In his opinion, navies were instruments through which express military might and develop economic policy, national unity, and diplomacy (Coppola, Reference Coppola2013: 199). In terms of trade, Tirpitz agreed with Mahan's view based on the idea that seaborne commerce represented for a state the core of its power, the assurer of its credit, and the pursuer of its comfort (Mahan, Reference Mahan1902: 145). As a rapidly industrializing country, Imperial Germany required access to raw resources and markets. However, the Royal Navy, while guaranteeing Britain access to raw resources and global markets, denied admission to rival powers. Until a divided Germany epitomized a subordinated attachment of the British global trading system, no serious threat to the status quo could appear; however, after its unification and rise into an industrial superpower, the challenge to British-led world economy became an inevitable fact. In this context, the lack of proper navy to protect its economy would have left Germany in the hands of an increasingly envious British Empire (Tirpitz, Reference Tirpitz1919: 229). In other words, it was only through the construction of a blue-water navy that Germany could safeguard its blooming overseas commercial assets.

In this regard, Tirpitz's plans for the construction of a German fleet represents a defensive reaction typical of a newly rising industrial state that wishes to challenge the status quo. The crucial aspect of his naval theory is that Tirpitz did not believe in the need to replace the world hegemon's fleet with a bigger and stronger fleet, but rather to counterbalance the former at a regional level. This strategy was based on the principles of deterrence and risk theory. When Tirpitz claimed that the German navy was not to be maintained on a bigger or a smaller scale than that of the Royal Navy, he intended to make an attack against the German fleet seem too risky and to dissuade it from happening (Tirpitz, Reference Tirpitz1919: 160).

The essence of Tirpitz's ‘risk theory’ – also known as ‘the Tirpitz Plan’ (Steinberg, Reference Steinberg1973) – assumed that if the German navy reached a sufficient level of strength, the Royal Navy would avoid direct confrontation with Germany, which constituted a threat for the mere fact of possessing a fleet. In case of open combat, the German navy would inflict such a damage on the Royal Navy that Britain would run the risk of losing its naval primacy. Therefore, the Tirpitzian strategy was based on a form of ‘mutual assured destruction’ scheme based on an a ‘balance of terror’, relying on the deterrent role of Germany's ‘risk fleet’ (Risikoflotte). Tirpitz believed that Britain would oppose an open confrontation with Germany to maintain its naval supremacy and thus protect its empire rather than lose the empire for averting Germany from becoming a world power. Clearly, Tirpitz was aware that Germany could not reach naval parity with Britain and believed that the only option for Germany was to construct enough battleships to dissuade Britain to engage them in battle. Britain would not risk a military confrontation because even in the case of victory, its naval losses would undermine the control over the international sea lanes upon which rested the survival of its empire. Moreover, Tirpitz believed that in the event of the destruction of the German navy, Britain would be powerless vis-à-vis the combined fleets of Russia and France.

Tirpititz's theory is essentially a regional strategy conceived for revisionist, anti-hegemonic challengers based on sea-denial tactics and deterrence principles. In contrast with Mahanian theories, the German fleet was meant to be kept in the regional waters of the North Sea and was not used for overseas sea power projection. Nonetheless, the buildup of the German fleet led to the foreseeable result of starting a worrisome arms race between Germany and Britain.

Apart from deterrence, Tirpitz believed that a navy would confer prestige on the international stage. International prestige would, in turn, stimulate the allure of other powers to conclude alliances. Thus, a mighty fleet, international prestige and alliance formation represented a logical equation (Tirpitz, Reference Tirpitz1919: 120). Moreover, Tirpitz recognized that technological revolutions that led to the creation of more sophisticated warships constituted some real gamechangers. For instance, the launching of HMS Dreadnought compelled Germany to reevaluate its naval construction program, avoiding its obsolescence.

History showed that Tirpitz's strategy was doomed to fail. The need to concentrate a stronger fleet against the German threat led Britain to conclude agreements with other powers – for example, the 1902 Anglo-Japanese treaty and the 1904 Entente Cordiale with France – that enabled it to return the bulk of its naval forces to its territorial waters overlooking Germany's coasts; moreover, the destruction of the Russian fleet by Japan in the Russo-Japanese War helped Britain in concentrating its naval might mainly against the German rival.

Admiral Tirpitz's legacy: tracking the modes of Chinese contemporary naval strategy

As seen in the section on the literature, while China's naval buildup may be interpreted through Mahanian lenses as a tool aimed at replacing the hegemonic rule of the US, following the debate on A2/AD tactics (Tangredi, Reference Tangredi2013; Biddle and Oelrich, Reference Biddle and Oelrich2016), this article suggests that China's strategy recalls a Tirpitzian scheme based on sea-denial strategies, regional balance, and dissuasion tactics. To corroborate this hypothesis, in the following section Germany's pre-World War One naval buildup (1907–1914) is compared diachronically with that of contemporary China, from the early years 2000s to present. Based on the comparison of primary and secondary sources, the findings underscore that both powers pursued a similar naval strategy vis-à-vis the corresponding hegemon.

Wilhelmine Germany's ‘Risikoflotte’ and the race toward doomsday

After its unification in 1871, Germany emerged as leading European continental power. When Chancellor Bismarck was forced to resign in 1890, the Kaiser and his entourage reoriented German foreign policy toward an assertive Weltpolitik aimed at colonial expansionism in search for a ‘place in the sun’. Although Wilhelmine Weltpolitik represented a concrete challenge to British world dominance, being aware of the impossible task of matching British sea power, Germany opted for a regional maritime strategy that compelled Britain to keep a constant guard in the North Sea: through this standoff strategy, Berlin sought to defy London's global dominance. Britain understood straightforwardly the danger stemming from the combination of an unmatched German terrestrial army with the building of a navy (Langhorne, Reference Langhorne1971: 361). Although Britain argued that a German fleet would put at stake the protection of British sea communications, Germany conceived a British encirclement (Einkreisung) of its coasts as a menace to its growth. Germany believed that a display of naval military might overlooking the British shores would represent a constant gun pointed at Britain's head that would oblige London to consider Berlin as an affirmed world power (Murray, Reference Murray2010: 657). By 1899, Bülow described the German naval buildup as a necessity in the pursuit of world power, stressing that the German people had to decide whether to become a hammer or an anvil in the 20th century (Murray, Reference Murray2010: 682).

Admiral Tirpitz was the undisputable architect of Imperial Germany's naval buildup. He believed that only through the building of a High Seas Fleet could Germany rise as a world power. As an outspoken supporter of naval might, Kaiser Wilhelm II advocated the building of the fleet, believing it to be the key instrument by which he could pursue his imperialist foreign policy based on overseas possessions (Wilhelm, Reference Wilhelm1926). As mentioned, Tirpitz's strategy pivoted on the idea that amassing a mighty battlefleet in the North Sea would require the Royal Navy to disperse its forces around the British Empire, which would lead to Germany's achievement of a balance of force that could injure or threaten British naval hegemony. The core of Tirpitz's ‘risk theory’ and the intrinsic role of the ‘Risikoflotte’ rested on the assumption that Britain would not challenge Germany if its fleet posed such a substantial threat to its own, especially in the event of warfare. In other words, without resorting to total war, Tirpitz believed that the mere existence of a German fleet stationing in the North Sea would represent a bargaining asset and imply major power transition in world politics by shifting the relative balance to Germany's favor and downgrading Britain's leading position. The very existence of the Risikoflotte was in direct conflict with Britain's two-power standard since it implied the idea that the German Navy was meant to be strong enough to avoid that the British Navy could face a naval conflict with another country at the same time (Gordon, Reference Gordon1996: 19). From a defensive perspective, Britain would not dare to attack the German Navy as it would not be able to guarantee its security based on the definition of the two-power standard (Keegan, Reference Keegan1988: 100). From an offensive standpoint, the Risikoflotte would represent a deterrent and a sea-denial instrument that would compel the Royal Navy to station a permanent fleet to supervise the North Sea.

The German naval construction was governed by the 1897 memorandum, navy bills passed in 1898 and 1900, and ensuing amendments enacted in 1906, 1908, and 1912. These acts offered the legal frame for the ambitious building program, whose ultimate goal was the creation of a German battle fleet rivaling, at least at a regional level, that possessed by Britain (Lambi, Reference Lambi1984). In promoting naval expansion through juridical tools and parliamentary approvals, Tirpitz wished to create an image of Germany as a defensive-oriented, status quo power. More than for economic or military purposes, the German fleet was designed for the political purpose of altering the existing balance of power in the world in Germany's favor and to achieve parity political status with Great Britain as a world power (Woodward, Reference Woodward1935). In essence, Germany's strategy pivoted on the idea that a naval balance and stalemate would promote cooperation in the short term and confirm Germany's status as world power in the long. Moreover, the German governmental entourage close to the Kaiser, including the chancellors Bülow and Bethmann-Hollweg, believed that a German mighty fleet would represent a useful bargaining tool to gain political concessions from Britain. Specifically, they assessed that in return for a confinement of German naval building, Britain might offer its neutrality in case Germany would be engaged in a continental war with France and Russia, and, secondly, that Britain might accept Germany's colonial claims (Woodward, Reference Woodward1935).

The heated competition between Europe's two leading powers in the building of battleships represented one of the most relevant features of world politics between 1906 and 1914, appearing as a clear struggle for mastery in Europe and a race for the control of the world's oceans (Maurer, Reference Maurer1997: 285). This Anglo-German competition has been interpreted as an escalating 15-year contrast between the two countries (Kennedy, Reference Kennedy1980). Britain promoted constant diplomatic attempts to decrease Anglo-German rivalry and foster arms control, including the discussions at the Hague Conference in 1907, the efforts during the summer of 1908 to initiate direct bilateral talks, the prolonged negotiations between 1909 and 1911, the Haldane mission of early 1912, Winston Churchill's pleas during 1912 and 1913 for a naval moratory, and final attempts by in the spring of 1914 (Maurer, Reference Maurer1992: 286; Maurer, Reference Maurer1997: 286). Although in 1906 and again in 1907, the Liberal government decided to cut the battleship-building program inherited from the outgoing Unionist government, not only did Germany refuse to reciprocate, but – apart from the proposal to promote tacit arms control in 1913 – the German government enlarged its shipbuilding program. If Germany would accept an agreement with Britain on arms reduction the benefits would have been several: a pro-German sentiment among British policymakers and public opinion would soar; Germany could improve his diplomatic position vis-à-vis Britain, weakening its ententes with France and Russia; Germany's rise as the world's second largest power would not have been perceived as risky; and, by accepting the accord, Britain too would undersize its naval building programs (Maurer, Reference Maurer1997: 293–295). Tirpitz never advocated any reduction of his military program but was willing to use arms control negotiations to boost his fleet buildup (Tirpitz, Reference Tirpitz1924). At the Hague Conference, Tirpitz ridiculed Britain claiming that a power that was four times as strong as Germany, in alliance with Japan and probably so with France, was demanding that Germany, the pygmy, would disarm (Hoerber, Reference Hoerber2011: 76). After this conference it became clear that Germany had no intention of containing its naval construction: the 1911 Agadir Crisis confirmed Berlin's animosity toward the established colonial powers of France and Britain.

The German admiral was essentially opposed to the arms reduction negotiations proposed by Britain for several reasons: first, he believed that the overall naval balance was turning against Britain, since every warship constructed anywhere in the world apart from Britain was ultimately an advantage for Germany because it adjusted the maritime balance of power (Tirpitz, Reference Tirpitz1919); secondly, he assumed that Germany could realistically achieve a rough parity in battle-fleet strength with Britain; and thirdly, he feared that, for matters of prestige, arms control negotiations could affect negatively the domestic political consensus and public opinion at Britain's benefit (Tirpitz, Reference Tirpitz1919).

A turning point in Anglo-German naval rivalry occurred in 1906, when Britain launched the first dreadnought, setting new standards of power, protection, and propulsion and rendering pre-dreadnought battleships obsolete (Norris, Reference Norris2012: 85–86). Although Britain conceived the dreadnought as a tool for deterrence, ironically its creation fueled an even more intense arms race that would eventually lead up to World War One (Kennedy, Reference Kennedy1980; Hoerber, Reference Hoerber2011: 66). The introduction of the dreadnought reprioritized Germany's naval military program. Tirpitz priority was now to interrupt the construction of pre-dreadnought units and, instead, to build as many dreadnoughts as possible. At the eve of World War One, the German Navy reached a ratio of 15 dreadnoughts to 22 vis-à-vis the Royal Navy (Sondhaus, Reference Sondhaus2001: 205).

The German naval race contributed to the outbreak of World War One. Since both Germany and Britain defined their political and strategic aims in stark and stubborn terms, a deflagration of a general conflict was inevitable. In this sense, the mere existence of capabilities was not decisive to determine the outcome of the Anglo–German rivalry, but the agents of governmental policies – both the Kaiser's entourage and a part of the English Cabinet – contributed through their obstinacy and mistrust to turn it into open war. To avoid this, Britain should not have responded to Germany's naval program with complete suspicion and an intensified arms race which culminated with the construction of dreadnoughts, while Germany should have reduced its shipbuilding program and abandon its attempts to threaten Britain's maritime supremacy and to weaken its ententes with France and Russia (Table 2).

Table 2. Anglo-German naval military comparison in August 1914

Source: Halpern (Reference Halpern1994). A Naval History of World War I. London: UCL Press.

China's Tirpitzian strategy and the quest for a regional balance in the pacific

The pre-World War One Anglo-German naval rivalry could represent today a worst-case scenario for Chinese-US relations. The parallels between Wilhelmine Germany's naval buildup and that of contemporary China are conspicuous. For much of its existence the People's Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) epitomized a neglected coastal defense force like the German Navy before Tirpitz's naval program; however, today, the PLAN is the largest navy in Asia (US Department of Defense, 2016). The history of China's naval modernization has been thoroughly investigated by the literature. For instance, Cole (Reference Cole2012, Reference Cole2016) has compared in historical perspective Chinese swinging inclinations toward continental and maritime power. At the same time, the Chinese internal academic debate on sea power vs. land power – embodied respectively by the ‘maritime faction’ and the ‘continentalist faction’ has introduced suggestive, often conflicting viewpoints (Erickson and Goldstein, Reference Erickson, Goldstein, Erickson, Goldstein and Lord2009). China's contemporary naval doctrine is the result of unique historical developments. While China's ancient maritime power come to an end between the 16th and 19th centuries (Kondapalli, Reference Kondapalli2000: 2037–2038), after the communist victory in 1949, the retreat of the Kuomintang to Taiwan led to the formulation of the naval strategy for the nascent PLAN, which was conceived as a tool for coastal defense. However, in 1979 Deng Xiaoping called for the construction of a strong navy with modern combat capability. Through the 1980s, the PLAN evolved from a navy aimed at coastal defense to one for offshore defense. At the time, Chinese officials envisioned a three-phase development plan that would transform the PLAN into a major sea power projector with blue-water capability within 2040 (Kondapalli, Reference Kondapalli2000: 2040). During the early 2000s, like Wilhelmine Germany, China gradually developed a stark naval nationalist mentality aimed at the construction of a large blue-water navy supported both by governmental officials and public opinion (Ross, Reference Ross2009: 60–65). The 2013 White Paper issued by the Information Office of the State Council announced the intention to construct a strong national defense and powerful armed forces commensurate with China's international posture (Information Office of the State Council, 2013). Analysts like Kaplan (Reference Kaplan2010) claim that in the 21st century, China will project hard power abroad primarily through its navy. East Asia's geography is the key factor in shaping the PLAN's maritime strategy. China perceives itself as encircled by major rivals. Along its southwestern border lays India, one of its major rivals; to the southeast and east lay two nation-state archipelagos, respectively the Philippines and Japan, which create a fence against China's main access in the South and East China Seas. The archipelagic line that connects Japan to the Philippines and Indonesia is commonly called the ‘first island chain’ (Chieh-Cheng Huang, Reference Chieh-Cheng Huang1994) – the second being the chain that connects the Aleutian Islands with New Guinea and eastern Australia. The PLAN views the first island chain as a potential tool from which the US and its allies could encircle China (MacHaffie, Reference MacHaffie2020: 4). In this regard, the PLAN's chief strategic goals are to ensure the control of Taiwan, safeguard its sea lines of communication, ward its strategic depth, and deter attacks (Tayloe, Reference Tayloe2017: 5). At the same time, Beijing aims at preventing the US and its allies from gaining access between the first and second island chains (Basu and Chatterji, Reference Basu and Chatterji2016).

China's naval buildup presents some stark analogies with that of Wilhelmine Germany. Like Tirpitz's Risikoflotte, the PLAN is also a regional navy with limited force projection capabilities conceived to deter aggression. Following a Tirpitzian strategy, China is not seeking to replace the US as global sea power, but it is focusing on local A2/AD capabilities, which are largely defensive mechanisms characterized by maritime denial rather than maritime control (Le Mière, Reference Le Mière2014: 139–140). Specifically, anti-access capabilities, which include satellite and missile technology, aim to prevent the adversaries form entering a theater of operations, while area-denial operations, which comprise integrated air-defense capabilities, mines, submarines, and missiles, aim to prevent the adversaries' freedom of action in an area under an enemy's direct control. Largely relying on ballistic defense, standoff weapons, and hypersonic missiles, A2/AD capabilities are essentially defensive, Tirpitzian in nature, and often adopted by the weaker party to benefit from asymmetrical or stand-off devices. Moreover, A2/AD would also include highly effective asymmetric weapons and non-kinetic threats such as information and cyber warfare (Le Mière, Reference Le Mière2014: 143). China's is fostering A2/AD capabilities through the buildup of three main naval assets: an ever-growing quiet submarine force equipped with air-independent propulsion and armed with wake-homing torpedoes; advanced anti-ship missiles launched from technological advanced surface assets, like guided missile destroyers or Houbei missile boats; and conventional DF-21 anti-ship ballistic missiles designed to counter US aircraft carriers. Moreover, the Chinese possession of two full-fledged aircraft carriers may be consistent, paradoxically, with its Tirpitzian strategy. Although the possession of aircraft carriers seems to be characteristic of a Mahanian strategy based on power projection in distant theaters, the PLAN's aircraft carriers are conceived specifically as a Tirpitzian-inspired deterrent to avoid an encirclement from the first island chain rather than as a Mahanian-inspired power projection, like the US utilizes its own (Rubel, Reference Rubel2011).

Although the US–China competition in the Pacific appears like an arms race, China describes its buildup as naval modernization and the US as a part of its pivot to Asia that targets no specific country. However, ongoing attempts by China to strengthen its A2/AD capabilities and the US efforts to counter them recall a typical tit-for-tat arms race dynamic in a zero-sum game perspective. Clearly, like in the Anglo-Germany, the hegemon's navy enjoys far more financial, material, and political support than that of the challenger. This asymmetry can be easily detected by confronting the overall US defense budget in 2020 to that of China as percentage of their respective nominal gross domestic product (GDP), that is respectively $778 billion (3.7%) and $252 billion (1.7%) (SIPRI, 2021a, 2021b). Considering these figures, China understands that it is neither feasible nor desirable to challenge globally the US naval might. However, in a Tirpitzian-inspired design, Beijing understood that the US Navy, like the Royal Navy before it, has global responsibilities that may leave it vulnerable to regional sea power projection, which, in China's case means investing in A2/AD assets such as submarines, long-range missiles, and mines. Moreover, the US–China arms race will probably remain asymmetric, since Beijing's objective is not to replicate the US Navy but rather to exploit available technologies to weaken US sea control in the Western Pacific (Gompert, Reference Gompert2013). In essence, the core of China's A2/AD strategy is to assure that the costs of power projection would be unacceptable to an attacker, which is an objective that does not require Beijing to attain military equality with Washington (Gormley, Erickson, and Yuan, Reference Gormley, Erickson and Yuan2014). In other words, China is seeking for naval military balance in the Pacific region. China's A2/AD capability has the potential to weaken the network of US supporters in East Asia. For instance, if Chinese strategies compel the US Navy to withdraw farther out into the Pacific, for example, in Guam or in the Hawaii, then its Pacific allies left behind will feel unprotected and exposed. This is the reason why the Chinese Navy can pose even at peacetime a danger to US interests and change the regional order if it convinces Pacific states like South Korea, Japan, the Philippines, or Indonesia to bandwagon with Beijing instead of balancing against it. Furthermore, following the theoretical scheme of Tirpitz's Risikoflotte, China considered the immense risks that the US Navy would have to face if it decided to engage militarily against the PLAN.

Finally, like Wilhelmine Germany's, Chinese naval buildup underscores a nationalist rhetoric behind it. Naval nationalism, international prestige, and the aspirations for the construction of a powerful navy are expressed by major publications, media outlets, think tanks, and academic debate (Ross, Reference Ross2009: 65). In this respect, China's claim is an explicit request for status, prestige, and respect enjoyed by great powers throughout history, including by dynastic China. In other words, in the same way that Imperial German officials and public opinion expressed their dissatisfaction vis-à-vis affirmed world powers and demanded for Germany's ‘place in the sun’, today China wishes to gain full international parity with the world's great powers and cancel any shameful memory connected with the ‘century of humiliation’.

Conclusions

This article was driven by the interest for understanding the reason behind contemporary Chinese naval buildup vis-à-vis the US maritime hegemonic role. Its attempt was to add a geopolitical dimension to the current debate, based on a theoretical comparison between the Mahanian and Tirpitzian strategies and an empirical comparison between contemporary China and Wilhelmine Germany.

The section on the literature review offered a nuanced categorization of the reasons behind China's military buildup and IR scholarly debate is divided on the topic. Constructivists tend to attribute the buildup to the recognition of the identity as world power and as a social quest for international status. On the contrary, offensive realists attribute it to a power-maximizing foreign policy to assure security benefits, whereas defensive realists consider it a consequence of the offence–defense balance and the security dilemma trap. Furthermore, neo-liberals believe that it is aimed at fostering multilateral initiatives and coordinating economic and political objectives. Other strands of the literature pay attention respectively on domestic political factors, the pursuit of prestige, ‘naval nationalism’, or ‘naval diplomacy’. Finally, some authors focus on the revisionist discourse on dissatisfied powers and their allure for power transition.

The theoretical section wished to compare two antithetical maritime strategies, namely Mahan's hegemonic naval theory and Tirpitz's regional risk theory. The theoretical findings contributed to understanding that a Mahanian strategy can be pursued only by a hegemon that possesses the economic and structural capacities for controlling the oceans. At the same time, challenging powers are more likely to implement a Tirpitzian local strategy based on dissuasion, deterrence, standoff, and sea-denial capabilities. However, the findings have also highlighted that, without the active role of agents and strategies, capabilities alone are not enough to determine the outcome of rivalries. As previously underscored, it was not the military buildup per se that ignited World War One, but rather its coupling with the leaders' mistrust and stubbornness.

The empirical section provided a comparison between the naval buildups of Wilhelmine Germany and contemporary China. In comparing the two cases, the findings observe a similar evolution. Specifically, in building up their navies both countries pursued a regional, Tirpitzian strategy based on sea-denial and deterrence capabilities to counter the respective hegemon. The relative inferiority vis-à-vis the hegemon was challenged not through the replacement of the hegemon's sea power, but with the pursue of calculated dissuasive risk strategies. Inspired by nationalist rhetoric, both Imperial Germany and China believed in the need to overcome their rank as ‘minor’ international powers following a prestigious military buildup in line with the self-perceived ‘world power’ status.

Further suggested research could focus on analyzing the US point of view vis-à-vis China's naval buildup. Specifically, it could examine on one hand what may be called the US ‘prestige dilemma’, namely the need for the US to intervene in averting China's military rise, lest it loses international prestige, and, on the other, Washington's credibility in providing extended deterrence to its Pacific allies – chiefly Taiwan, Japan, and South Korea.

Today, Chinese sea power is still far from posing a serious threat to that of the US and its Pacific or NATO allies. Moreover, despite its maritime rise, China remains essentially a continental power. Unlike the US, it shares borders with fourteen countries, four of which possess nuclear weapons. China's Silk Road Economic Belt (SREB) initiative pivots entirely on continental Eurasian projection, whereas the MSR's full-sized realization is still doubtful and uncertain. The prospect of Sino-Russian competition in Central Asia requires China to focus its attention on its western and northern borders. Moreover, the tensions with India, mainly related to both disputed borders and the Kashmir issue, are always a source of concern for Beijing. At the same time, China's internal borders – from Afghanistan to Mongolia – are difficult to defend. Central Asian and Inner Asian geopolitical challenges threaten constantly China with the specter of terrorism and separatism. In this sense, as Mahan suggested, a country that cannot secure its internal borders will not be able to develop full-fledged sea power. However, if Beijing will unceasingly continue its naval buildup, this could both bolster arms races and lead to direct confrontation due to regional security dilemmas.

What are the strategic consequences of China's Tirpitzian strategy in the Pacific? Will they increase or diminish the chance of the outbreak of a conflict? Although this is difficult to forecast, the existence of a Chinese fleet that bases its strategy on A2/AD deterrence mechanisms contributes to creating a balance of forces in the Pacific region, discouraging hostile initiatives. However, at the same time it spreads mistrust and fear among the US Eastern Asia and Pacific allies: the credibility of the US as a security provider also entails the need to support those allies that are menaced by rivalrous military buildups.

To conclude, US–China naval competition has the potential to include the full agenda of US–China relations, challenging cooperation on a wide range of issues including nuclear nonproliferation in the Korean Peninsula, the Taiwan issue, bilateral economic ties, and the problem of human rights vis-à-vis Xinjiang, Tibet, or Hong Kong. Indeed, US–China economic interdependence suggests that the costs of a direct confrontation would be higher than the benefits, however, can this be enough to avert a direct confrontation? After all, in 1914 Anglo-German economic relations, albeit conspicuous, did not stop Britain and Germany from engaging in a mortal combat. However, a direct confrontation, as in the case of the Anglo-German rivalry, will not be just a byproduct of system and capabilities, but the result of the agency's choices.

Funding

The research received no grants from public, commercial or non-profit funding agency.

Data

The replication dataset is available at http://thedata.harvard.edu/dvn/dv/ipsr-risp

Conflict of interest

None.

Dr Paolo Pizzolo is a Research Fellow in International Relations. He holds a Ph.D. in Political Science and International Relations at LUISS University, Rome, Italy. He is Fellow at the Centre for the Cooperation with Eurasia, the Mediterranean, and Sub-Saharan Africa (CEMAS) of La Sapienza University of Rome.