“The Return of History” declared Time Magazine on the cover of its 14 March 2022 issue. The headline loomed over an image of a Russian tank rolling into eastern Ukraine, part of Russia’s full-scale invasion a few weeks earlier. In some respects, the headline is problematic. Many places have experienced horrific bloodshed in recent years, with less international attention and certainly less outside intervention. The sub-heading, “How Putin Shattered Europe’s Dreams,” seemed to suggest that Europe, at least, should have outgrown this behavior. But, in an important respect, Time was right to note the unusual nature of this event in the contemporary world. The forcible seizure of territory by one state against another, once a common feature of international politics, has become less prevalent over time, particularly since the end of World War II. Whereas state borders once changed frequently through threat or war, or were shifted around in great power conferences, they have now largely stabilized. A norm of territorial integrity—which prohibits the acquisition of territory through the threat or use of force—is thought to be a core feature of the “postwar liberal order.”Footnote 1

Today, scholars and policymakers express concerns that this trend might reverse, portending the “return of conquest.”Footnote 2 The full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022 followed a limited incursion in 2014, during which Russia annexed the Crimean peninsula. In 2008, Russia invaded Georgia and wrested away two regions, Abkhazia and South Ossetia, that have become part of Russia de facto if not de jure. Earlier that year, Kosovo declared its independence from Serbia, an act recognized by many Western countries. China has in recent years been more assertive in its territorial claims on neighbors, from Taiwan and the South China Sea in the east to the frontiers with India and Bhutan in the west. In Hungary, populist president Viktor Orbán has stoked century-old longings to restore the “Greater Hungary” that was dismembered after World War I.

Developments in the United States have exacerbated these concerns. Some scholars attribute the postwar decline in conquest to US efforts to enshrine and enforce the norm of territorial integrity.Footnote 3 These efforts were most clearly evident in the Persian Gulf War, as well as in military and economic support for Ukraine since the Russian invasion. President Trump, however, has put that commitment in doubt. In 2019, he recognized the Israeli annexation of the Golan Heights and Morocco’s seizure of Western Sahara.Footnote 4 When Trump returned to office in 2025, he not only suggested that Ukraine should cede territory to end the war but also mused about annexing Canada and Greenland.

Do these developments portend a return to an earlier pattern of international politics in which territory was frequently redistributed through the use or threat of force? Here, I review and evaluate different mechanisms through which these developments could threaten the territorial order. The goal is not to make specific predictions but to assess which threats are most plausible in the light of recent events, particularly the prospect of Russian territorial gains in Ukraine, the changing attitude of the United States, and strains on postwar institutions and norms. I delineate several causal channels through which such developments could pose broader challenges to the current territorial order. Set against these concerns is the recognition that most borders in the world today are long settled, and there are sources of stability at the dyadic and regional levels that make settled borders robust to disruption. Escalation of conflicts in already contested areas is possible, but the most destabilizing outcome—widespread contestation of already established borders—is also the least likely.

What Holds the World Together?

The modern international system rests on what Simmons and Goemans call the “sovereign territorial order,” the division of the world into territorially bounded sovereign states.Footnote 5 There are two different ways this order could be challenged: through widespread efforts to revise the distribution of territory or through the promulgation of alternatives to the territorial state. This essay focuses on the former as the most likely threat in the near to medium term. Of course, even in the absence of conflict over territory, borders can be a site of tension for other reasons, such as the flow of illegal goods, refugees, or armed groups—important topics that are nonetheless not the focus here.

Figure 1 shows the frequency over time of forcible changes of borders between independent states, through conquest, annexation, occupation, or coerced transfer of territory.Footnote 6 A decline after World War II is evident, particularly when normalized by the number of contiguous dyads.Footnote 7 Importantly, more changed than just the overall frequency. As Altman shows, later conquests are more likely to implicate small, peripheral territories, such as islands.Footnote 8 They are also more likely to involve grey areas where sovereignty was contested or undetermined. Russian predations against Ukraine stand out from more recent events in part because they involve large areas internationally recognized as Ukrainian. Note also that changes in the pre-1945 period tended to cluster together in time, such as around the two world wars, suggesting processes of contagion that caused borders to fail interdependently.

FIGURE 1. Forcible transfers of territory between independent states, 1816–2025

There is no shortage of explanations for this pattern, and it is helpful to distinguish two broad categories. The first focuses on technological changes that have reduced the importance of territory for economic production and national power and increased the costs of using force. Industrialization and, later, the rise of the service and information economies created sources of prosperity that do not depend on control of territory, weakening the economic motive for expansion.Footnote 9 Declining transportation and communication costs have facilitated trade and investment, allowing actors to profit from economic activity that does not take place within their borders.Footnote 10 Consistent with these claims, Markowitz and colleagues show that states that are less resource dependent and/or more economically developed are less likely to make territorial claims.Footnote 11 The technology of war has also changed, with military power less dependent on the size of a country’s population.Footnote 12 Furthermore, the costs associated with war in the industrial and, later, nuclear age have made conquest less appealing, which might explain why most territorial aggression in the modern era focuses on marginal areas that can be taken with low risk of war.Footnote 13

The second set of arguments focuses on political, institutional, and normative features of the post—World War II international system. Four aspects of this system figure to varying degrees in prominent arguments:

The territorial integrity norm. A norm against conquest emerged in the aftermath of World War I, along with attempts to institutionalize it in the interwar period, most prominently in Article 10 of the Covenant of the League of Nations. This project foundered on the revisionist aims of the Axis powers, which revealed the impotence of the League to uphold its mandate. But the effort was renewed after World War II and enshrined in Article II of the UN Charter, which prohibits the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity of any member state. Numerous regional security organizations that emerged in this period contain the same prohibition.Footnote 14

US leadership. The United States’ own territorial ambitions were satisfied by the early twentieth century, and the experience of two world wars convinced Americans that territorial conflict elsewhere in the world was dangerous and destabilizing.Footnote 15 The United States has not always been consistent in defending the territorial status quo and has at times tolerated territorial seizures by partners, such as Israel in 1967 and Turkey in 1974.Footnote 16 But it also has found the norm useful for building coalitions against aggression, as in the Persian Gulf War.Footnote 17

Economic liberalization. Economic features of the postwar order, particularly the liberalization of trade and protections for foreign investment, created cheaper ways to access and exploit resources in other countries without direct control.Footnote 18 The large benefits of globalization created incentives for states to reduce uncertainty by avoiding or resolving territorial disputes.Footnote 19

The spread of democracy. Zacher argues that liberal democracies came to reject territorial aggrandizement, regarding conquest as a source of major war and anathema to self-determination of people. Other scholars have suggested that democratic institutions limit the benefit leaders get from expansion and increase the costs of politically incorporating new people.Footnote 20

The two sets of explanations are not mutually exclusive, but they have different implications for the future. If a declining appetite for territory stems from economic development and technological change, then it might be expected to persist in the absence of dramatic changes to the sources of economic growth and military power. A possible long-run threat is that climate change could radically alter the distribution of arable land and potable water, rekindling incentives for expansion.Footnote 21 To the extent that territorial order rests on some combination of a normative prohibition on conquest, leadership by territorially satisfied great powers, economic liberalization, and democracy, then current trends are more immediately worrisome. Every one of these factors is under strain with the prospect of Russian conquests in Ukraine, a withdrawal of US leadership, increasing barriers to trade and investment, and the erosion of democracy—often at the hands of nationalist leaders wielding ethnic grievances.Footnote 22 It is easy to envision a future in which greater demand for territorial expansion meets weaker constraints.

Threats to the Territorial Order

To more clearly assess and delineate the risks, we need to consider specific mechanisms that could give rise to widespread challenges to the existing order. I organize these into three channels: one operating through the distribution of power, one through the credibility of actors that want to restrain revisionism, and one through the legal and ethical norms against conquest.

Power Channel

History and theory suggest that the greatest threat to territorial order comes from powerful states with expansive territorial ambitions. The pre-1945 clustering of conquests during major power wars reflects this risk.Footnote 23 The most obvious threat from these actors comes directly from their interest and ability to change the status quo. Not only are they in a position to demand or seize territory from neighbors, but conquest might enable further aggression by enhancing a state’s power through the acquisition of resources or strategic location. Cederman and colleagues show that, in Europe during the period between 1490 and 1790, increases in state growth due to war strongly predict subsequent growth, generating a positive feedback from territory to power to more territory.Footnote 24

A revisionist great power could also spur territorial aggression by third parties through two indirect mechanisms: bandwagoning and balancing. First, aggression can fuel contagion if other states join forces with the aggressor in order to satisfy their own territorial ambitions. Schweller invokes the image of smaller revisionist states as “jackals” who feed off the lion’s kill, such as Hungary and Italy in World War II.Footnote 25 The relationship between the lion and jackals can be self-reinforcing because the promise of gain causes bandwagoning, which increases the aggressor’s ability to deliver gains. Conquest can also spur territorial revisionism by rivals seeking to balance or limit the conqueror’s gains. Soviet occupation of the Baltic states in 1940 was driven by this logic.Footnote 26

Note that this mechanism assumes that the revisionist power has expansive territorial aims, so that conquest builds on conquest. If, however, a state has limited objectives, then a successful conquest may satisfy its territorial ambitions.Footnote 27 Thus the main danger is a revisionist state with extensive aims and a willingness to foment territorial instability. These are often associated with grand nationalist projects seeking to restore some past “golden age.”Footnote 28 In the nineteenth century, German, Italian, and Greek unification movements propelled repeated conquest attempts; in the twentieth century, it was imperial projects such as Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan.

In the contemporary period, the greatest threat comes from Russia, where Vladimir Putin has cast doubt on the legitimacy of post–Soviet states and waxed nostalgically about the Russian Empire.Footnote 29 China’s ambitions present a more open question. Like Russia, China can point to a prior era, during the Qing dynasty in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, when its territorial extent was much larger. But although China has dangerous territorial claims on some neighbors—particularly Taiwan, India, and in the South China Sea—it has settled border disputes with many more.Footnote 30 While China’s growing power has made it more assertive in ongoing disputes, a pressing question is whether growing ambitions will disrupt existing deals. Warning signs include a recent expansion of China’s territorial claims against Bhutan and suggestions that it might reassert historic claims against Russia in the Far East.Footnote 31

The Credibility Channel

A second channel of disruption rests on beliefs about the willingness of leading states to preserve the territorial status quo. The territorial integrity of weak states with aggressive neighbors may depend on strong powers to act in their defense, through diplomatic backing, provision of arms, economic sanctions, or military intervention. Whether the prospect of this support successfully deters aggression depends on the potential aggressor’s beliefs about the defender’s willingness and ability to step in.Footnote 32 To this point, Carter and Abramson show that territorial claim making increases when incumbent great powers are weakened or distracted by internal or external challenges.Footnote 33

The attitude of the United States is particularly important. On Ukraine, Trump has suggested that territorial concessions are necessary to end the war and that US willingness to provide support is limited. But Russia’s goals likely extend beyond territory that it would get in a deal, so Ukraine will need credible security guarantees to guard against a resumption of conflict. If the United States is not willing to provide those guarantees, the question is whether other European countries will be able to do so. More broadly, Trump has adopted a transactional view that includes a willingness to recognize territorial changes to cement partnerships and make deals. Although this attitude may be idiosyncratic to a president with a real estate background,Footnote 34 the effects could persist if they create doubt about long-term US global commitments.Footnote 35

That said, there are limits to this credibility channel. Actors do not mechanistically draw inferences from one case to the next, nor should they unless those cases are sufficiently similar.Footnote 36 A reluctance to support Ukraine suggests a weakening of the US security guarantees to Europe; this is no small matter given the possible extent of Russian ambitions. But it does not imply that the United States would also be unwilling to back Guyana against Venezuela, which has pressed long-standing claims to two-thirds of the former’s territory. Elsewhere, Trump has followed the footsteps of past administrations in offering mediation and inducements to broker agreements, such as in the conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan.Footnote 37 Furthermore, if withdrawing support for Ukraine permits Washington to shift resources to East Asia, the results would be enhanced deterrence of China, rather than the opposite.Footnote 38 Pulling out more broadly, there are many people around the world who do not regard the United States as their protector—indeed, quite the opposite—for whom this consideration is largely irrelevant.Footnote 39

The Normative Channel

A final mechanism of disruption hinges on the breakdown of the legal and normative prohibition on conquest. In this view, serious violations and diminished commitment to the norm by leading states weaken its constraining power, hamper coordinated responses, and create precedents that put territorial expansion back on the menu. To this point, Aksoy, Enamorado, and Yang show that Chinese respondents primed to think about the Russian invasion of Ukraine were more likely to think the use of force against Taiwan would be morally justified.Footnote 40 Successful territorial aggression may also call into question the effectiveness of global and regional security organizations that instantiate these rules. As the literature on norm robustness shows, violations can lead to the strengthening of norms, rather than their erosion.Footnote 41 But Brunk and Hakimi suggest that the latter is more likely in the current geopolitical context. Not only are challenges coming from powerful revisionists, but also the United States has declining credibility as an advocate—not just in a material sense, but also in a normative sense, given its own violations of the “rules-based order.”Footnote 42

Sources of Stability

Although these threats are important, fears of renewed conquest rest on an implicit assumption that the territorial order is brittle and large numbers of potential challenges have been held back by systemic and/or normative constraints. An alternative possibility is that, holding aside a number of active and long-standing disputes, revisionism is held at bay because governments see meager benefit and significant costs to challenging the status quo. Indeed, set against the concerns raised before are sources of stability at the dyadic and regional levels.

Institutionalization

A significant body of research shows that the longer a border remains in place, the more it becomes routinized and institutionalized in a way that brings gains to both states. To some extent, this stability arises from the functional benefit of having a line whose location is well defined, commonly recognized, and expected to remain unchanged. Boundaries do not simply allocate territory; they also create expectations about where the jurisdiction of one state ends and another begins.Footnote 43 They tell people at both the local and national levels which state’s laws apply at a given location, which state’s police are responsible for providing order, and to which state people must pay taxes and seek services.Footnote 44 This coordination creates benefits that are jeopardized if the location of the boundary becomes contested.

The settlement of borders can also create feedbacks that reinforce the equilibrium. Stability and jurisdictional clarity reassure economic actors concerned about the political risks of conflict. The resulting increase in trade and financial flows creates benefits that further incentivize stability.Footnote 45 Institutions can arise to manage border problems, making them less likely to escalate.Footnote 46 Several processes have also reduced mismatches between political boundaries and identity-based boundaries due to ethnicity, religion, or language. Particularly in Europe, irredentism and secession have tended to move political borders in line with demographic borders.Footnote 47 Meanwhile, ethnic cleansing, population exchanges, internal settlement, and voluntary migration have shifted demography in line with political borders.Footnote 48 And where ethnic kin still live across the border in large numbers, their assimilation and influxes of other groups have reduced the incentives for irredentism.Footnote 49 Changing political dynamics associated with these developments can help states acclimate to lost territory over time.Footnote 50

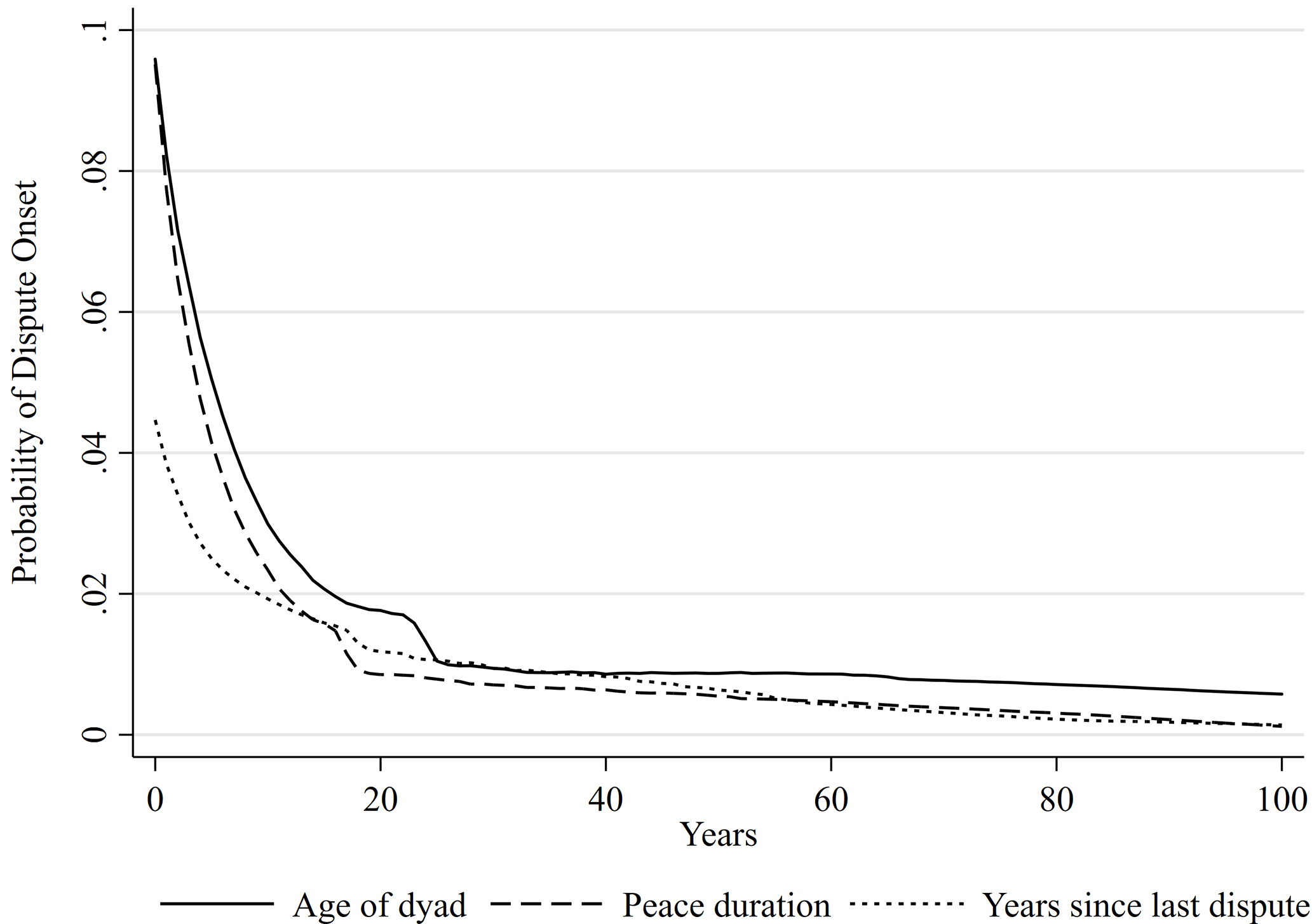

Thus there is a pronounced tendency for borders, once settled, to remain settled. Figure 2 shows how the probability of territorial dispute onset in a contiguous dyad varies with the age of the dyad, how long the dyad has gone without a territorial dispute, and the number of years since the most recent dispute ended, if any.Footnote 51 For each indicator, there is a strong downward effect, and new dispute onsets become exceedingly rare after two decades of peace.

FIGURE 2. The effect of time on the incidence of dispute onset

Regional Equilibria

There are also regional equilibria that limit the reach and effect of shocks elsewhere in the system. In the postwar period, Europe benefited from the reassuring presence of the United States, as well as Moscow’s efforts to dampen ethnic nationalism in its own sphere. Even if those recede, deep political and economic integration guard against a return to pre-1945 patterns of irredentism. Hungary presents the hardest test: Led by a nationalist who has played on irredentist sentiment and is ideologically aligned with Russia, it is also embedded within European security and economic institutions.

Latin America experienced numerous territorial disputes in the century following independence, many owing to unclear colonial borders. But most of those conflicts were resolved by the 1930s. Schenoni and colleagues describe the crystallization of a “norm complex” built around territorial integrity and nonintervention that reduced the frequency and intensity of territorial claims and militarized disputes.Footnote 52 Despite the global instability associated with World War II, no previously settled border in Latin America was recontested during this period, suggesting that regional equilibria can be robust to disruption elsewhere in the system.Footnote 53

Similarly, standard accounts of postindependence Africa emphasize the regional equilibrium that grew out of inherited borders, multiethnic societies, and state weakness.Footnote 54 In this view, the newly independent states recognized that efforts to change the territorial status quo threatened to unleash chaos: irredentist claims by groups partitioned by borders and separatist claims by groups seeking their own state. This danger to the new states and their leaders underpinned early agreement to respect the colonial borders and enshrine the territorial integrity norm in the Organization of African Unity. As Herbst notes, this stability predated the construction of the postwar order and did not need the United States or others to create or maintain it.Footnote 55

Looking Ahead

What do these considerations imply for the future? Most borders in the world today are long settled. Updating data from ICOW and other sources, I estimate that 80 percent of contiguous dyads in 2025 never experienced a territorial dispute or resolved their most recent dispute at least twenty years ago. Another 6 percent resolved disputes in the last twenty years. Seven percent have an unresolved claim that has not been militarized for at least two decades. Another 7 percent, constituting twenty-four dyads, have active disputes that have been militarized in that time frame.Footnote 56 These figures contain both bad news and good.

Borders with active disputes are the most dangerous, but that has always been true, and most active disputes have been ongoing for decades. For these, the question is whether already violently contested borders will become even more violent. Escalation is certainly possible where dissatisfied states perceive weaker constraints or greater power to impose a military outcome. But we also need to guard against inferring connections where there may be none. The escalation of existing disputes is often driven by domestic political considerations within challenger states. Altman and Lee, for example, show that conquest attempts within ongoing disputes are strongly predicted by diversionary incentives and careerist motives in the military.Footnote 57 The marginal contribution of systemic developments will be tricky to discern. Moreover, some of the most dangerous possibilities, such as a Chinese invasion of Taiwan or an India-Pakistan war over Kashmir, constitute serious threats to international security, but not necessarily to the broader territorial order.Footnote 58

The bigger threat to territorial order would arise if settled borders start to unravel or latent disputes reawaken. The cases of greatest concern are states with a “longing” for lost territory that could give rise to a new claim if conditions permitted—just as Russia’s longing for Crimea sat dormant until an opportunity arose. Many people around the world can look across their borders and see territory that was once theirs (or imagined to be once theirs) or occupied by ethnic or religious kin. Most of those longings lie dormant under long settled borders, where institutionalization at the dyadic and regional levels create stability and cushion against shocks. Disruption of these equilibria is less likely—but would be a harbinger of worse to come.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material for this essay is available at <https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818325101173>.

Acknowledgments

Given the short time available to write this essay, I did not have an opportunity to circulate it for comments. However, the ideas presented here have benefited from fruitful conversations and collaborations with Hein Goemans, Jamie Hintson, and Richard Maass. I am grateful to Yara Elian and Amelie Haworth for research assistance and to the anonymous referees for suggestions.