Introduction

In the dynamic arena of contemporary business, digital transformation (DT) has undoubtedly ascended as a strategic imperative, fundamentally redefining processes, strategies, operations, and business models (Orero-Blat, Jordán, & Palacios-Marqués, Reference Orero-Blat, Jordán and Palacios-Marqués2022; Verhoef et al., Reference Verhoef, Broekhuizen, Bart, Bhattacharya, Dong, Fabian and Haenlein2021; Vial, Reference Vial2019). Integral to leveraging this transformation, big data analytics capabilities (BDAC) serve as foundational constructs, enabling organizations to harness the exponential data growth for informed decision-making and competitive differentiation (Mikalef, Boura, Lekakos, & Krogstie, Reference Mikalef, Boura, Lekakos and Krogstie2019; Mikalef, Krogstie, Pappas, & Pavlou, Reference Mikalef, Krogstie, Pappas and Pavlou2020; Wamba, Queiroz, Wu, & Sivarajah, Reference Wamba, Queiroz, Wu and Sivarajah2020). Such capabilities, encompassing workforce, management, and infrastructure analytics, are essential for actualizing the investment in DT (Kim, Ritchie, & McCormick, Reference Kim, Ritchie and McCormick2012; Mikalef et al., Reference Mikalef, Boura, Lekakos and Krogstie2019; Orero-Blat, Palacios-Marqués, Leal-Rodríguez, & Ferraris, Reference Orero-Blat, Palacios-Marqués, Leal-Rodríguez and Ferraris2024).

While the antecedents of BDAC have been subject to extensive scrutiny, organizational culture (OC) remains a relatively uncharted determinant (Chen, Lu, Wang, & Pedrycz, Reference Chen, Lu, Wang and Pedrycz2024; Upadhyay & Kumar, Reference Upadhyay and Kumar2020). It has been argued that a deep understanding of cultural nuances is essential for a successful digital transition (Firican, Reference Firican2023; Pedersen, Reference Pedersen2022). Therefore, the lack of an adequate culture is also seen as the main obstacle to DT and the main reason why this difficult process often fails (Lunde et al., Reference Lunde, Sjusdal and Pappas2019). Research posits that without a proper cultural bedrock attuned to the exigencies of digital change, efforts to promote DT and BDAC may prove futile (Hemerling, Kilmann, Danoesastro, Stutts, & Ahern, Reference Hemerling, Kilmann, Danoesastro, Stutts and Ahern2018).

Studies like Pradana, Silvianita, Syarifuddin, and Renaldi (Reference Pradana, Silvianita, Syarifuddin and Renaldi2022) concluded that OC becomes a key factor in enhancing digital strategy and performance, but digitalization doesn’t affect culture. For this reason, we focus on the antecedent role of OC in DT. Pfaff, Wohlleber, Münch, Küffner, and Hartmann (Reference Pfaff, Wohlleber, Münch, Küffner and Hartmann2023) have investigated the impact of OC dimensions, based on Hofstede’s model (Hofstede, Reference Hofstede1998), on the process of DT. Nguyen (Reference Nguyen2018) analyzed the impact of OC in big data following Competing Values Framework (CVF) (Quinn and Rohrbaugh, Reference Quinn and Rohrbaugh1983) but it has been demonstrated that without DT and BDAC an organization is not able to fully extract all value of big data (Gupta & George, Reference Gupta and George2016). Steiber and Alvarez (Reference Steiber and Alvarez2023) posited that several values aligned with digital culture (Leal-Rodríguez, Sanchís-Pedregosa, Moreno-Moreno, & Leal-Millán, Reference Leal-Rodríguez, Sanchís-Pedregosa, Moreno-Moreno and Leal-Millán2023) favor DT, but they do not consider in their research BDAC and its key role for organizations. As seen, the literature lacks a detailed exploration of specific cultural typologies that catalyze BDAC and the pivotal role of DT within this interplay. This study aims to close this research gap by exploring in detail how an organization’s cultural typology can be a key antecedent to the successful implementation of DT and the effective promotion of BDAC. So, the research question is: Which is the cultural archetype that favors the most DT and the promotion of BDAC?

Employing the Organizational Culture Assessment Instrument (OCAI) as outlined by Cameron and Quinn (Reference Cameron and Quinn1999), which draws from the CVF (Quinn and Rohrbaugh, Reference Quinn and Rohrbaugh1983), and complemented by Leal-Rodríguez et al.’s (Reference Leal-Rodríguez, Sanchís-Pedregosa, Moreno-Moreno and Leal-Millán2023)digital culture scale, this study endeavors to align the assessment with contemporary organizational realities. This integration is crucial as it introduces the digital culture archetype, characterized by openness to innovation,technological fluency, agility, and data-centric decision-making. Unlike traditional cultural types such as hierarchical, market, and clan cultures, digital culture emphasizes continuous learning, rapid adaptation, and seamless integration of new technologies. The sample is composed by 183 Spanish companies from the point of view of the heterogeneity of the sectors. To do so, we will use the Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) methodology, in line with approaches by Felipe, Roldán, and Leal-Rodríguez (Reference Felipe, Roldán and Leal-Rodríguez2017), Ashrafi, Ravasan, Trkman, and Afshari (Reference Ashrafi, Ravasan, Trkman and Afshari2019), and Leal-Rodríguez et al. (Reference Leal-Rodríguez, Sanchís-Pedregosa, Moreno-Moreno and Leal-Millán2023).

This study contributes to the CVF theory by emphasizing the strategic importance of cultural typologies within organizations for DT and BDAC promotion. It offers novel insights into the domain of TD by meticulously detailing OC and identifying cultural typologies that positively influence the development of BDAC, mediated by DT. This is important because misalignment between OC and DT process could risk employees being unable to identify strategy and resist improvement initiatives (Carvalho, Sampaio, Rebentisch, Carvalho, & Saraiva, Reference Carvalho, Sampaio, Rebentisch, Carvalho and Saraiva2019). Such insights equip managers with the knowledge to effectuate incremental cultural adjustments, propelling organizations toward the successful realization of DT benefits.

Subsequent to this introduction, the ensuing sections delineate the research model, hypotheses, and theoretical foundations, followed by a description of the research methodology. The fourth section presents the empirical findings from the PLS-SEM analysis, and the paper culminates with a discussion of the implications, conclusions, and the broader impact of the study.

Theoretical framework

DT and BDAC

DT is a strategic priority for modern organizations, aiming to enhance technology-related resources to reduce costs, create new business opportunities, and improve organizational processes (Nicolás-Agustín et al., Reference Nicolás-Agustín, Jiménez-Jiménez and Maeso-Fernández2022). However, simply investing in digital technologies is not enough; organizations must also develop the necessary skills and foster the right culture to fully harness the benefits of DT (Coco et al., Reference Coco, Colapinto and Finotto2024).

DT facilitates better information exchange, improves operational efficiency and productivity (Loebbecke & Picot, Reference Loebbecke and Picot2015), and enhances stakeholder value (Choy & Kamoche, Reference Choy and Kamoche2021). A key result of DT is the development of BDAC, which require a certain level of digital maturity within the organization (Pramanik, Kirtania, & Pani, Reference Pramanik, Kirtania and Pani2019). BDAC enable companies to leverage data effectively, turning digital investments into actionable insights and competitive advantages (Mikalef et al., Reference Mikalef, Boura, Lekakos and Krogstie2019).

The synergy between DT and BDAC is essential for organizations to maximize the value of their data, improving decision-making and increasing their agility in dynamic environments (Barlette & Baillette, Reference Barlette and Baillette2022; Ceipek et al., Reference Ceipek, Hautz, De Massis, Matzler and Ardito2021; Wamba et al., Reference Wamba, Gunasekaran, Akter, Ren, Dubey and Childe2017). Without sufficient digital maturity and a strong foundation of DT, organizations may struggle to fully develop BDAC and unlock the full potential of their digital initiatives (Gupta & George, Reference Gupta and George2016).

OC and CVF

Following with the concept of OC, one can say that it can be characterized in various forms; it encapsulates the shared values, beliefs, and practices that unify the members of an organization – essentially, the ‘social glue’ that cements the organization’s collective identity. It encompasses an organization’s commitment to adapt and evolve within the technological milieu, striving to meet or anticipate future demands. This adaptability necessitates that organizations not only protect their core values to maintain strategic, functional, and operational continuity but also sustain their cultural essence amidst change (Leal-Millán, Reference Millán1991; Schein, Reference Schein1985).

This research adopts the CVF by Cameron and Quinn (Reference Cameron and Quinn1999), a seminal and widely applied model in the study of OC. The CVF outlines two key dimensions: one contrasting the focus on stability, order, and control with a focus on flexibility, dynamism, and adaptability; the other juxtaposing an external orientation – marked by differentiation, competition, and rivalry – with an internal orientation that promotes integration, unity, and collaboration. Intersecting these dimensions yields four distinct, yet complementary, cultural typologies: clan, adhocratic, market, and hierarchy, each with its own defining characteristics. Furthermore, recognizing the evolution of organizational environments, recent scholarship has introduced a digital cultural archetype. Pedersen (Reference Pedersen2022) and Leal-Rodríguez et al. (Reference Leal-Rodríguez, Sanchís-Pedregosa, Moreno-Moreno and Leal-Millán2023) have substantiated this with a validated psychometric scale.

The study of Zhang, Khan, Wang, and Tang (Reference Zhang, Khan, Wang and Tang2023) about open government data highlights the profound influence of national culture on technological adoption, suggesting that similar cultural dimensions within organizations can significantly impact the successful deployment of DT and BDAC, due to the great importance of corporate values as predictors of the behavior and attitudes of the people who form the company (Clouet, Leal-Rodríguez, Sanchís-Pedregosa, & Orero-Blat, Reference Clouet, Leal-Rodríguez, Sanchís-Pedregosa and Orero-Blat2024). However, despite the established influence of OC on various organizational processes, knowledge about its specific role as a catalyst or barrier in the context of DT remains limited (Nicolás-Agustín, Jiménez-Jiménez, & Maeso-Fernández, Reference Nicolás-Agustín, Jiménez-Jiménez and Maeso-Fernández2022). The current literature on cultural archetypes provides the groundwork from which we draw inferences and postulate our research hypotheses, particularly concerning the alignment of cultural micro foundations and values with the nurturance of BDAC.

Research model and hypotheses development

In this section of the literature review, the five hypotheses of this research and finally the research model derived from them will be presented in a concise form.

The impact of clan culture on DT and BDAC

According to the model proposed by Cameron and Quinn (Reference Cameron and Quinn1999), some of the values that characterize the clan cultural archetype are cohesion, commitment, participation, integration and teamwork. Teamwork, collaboration, and team cohesion have been shown in several studies to be HRM practices favorable to DT (Bartsch et al. 2020). Collaboration and data sharing across business services also foster flexibility and responsiveness (Ciacci, Balzano, & Marzi, Reference Ciacci, Balzano and Marzi2024). The development of BDAC requires greater collaboration, but also fosters this necessary collaboration that clan culture has intrinsic to its core values (Barlette & Baillette, Reference Barlette and Baillette2022). Mutual trust between the firm and its employees is essential in today’s increasingly digital workplace (Akhtar et al., Reference Akhtar, Frynas, Mellahi and Ullah2019). Working from home and having flexible hours are becoming norms, yet these conveniences call for the organization to have faith in its members’ dedication to the organization’s mission. Clan culture groups also foster a culture that is tolerant of failure and promotes knowledge sharing (Nanayakkara, Wilkinson, & Halvitigala, Reference Nanayakkara, Wilkinson and Halvitigala2021), which is a necessary condition for creativity (Kane, Palmer, Phillips, Kiron, & Buckley, Reference Kane, Palmer, Phillips, Kiron and Buckley2015).

However, clan culture is typical of family businesses where the CEO is the owner, who acts as a guide and mentor, but where there is no room for large investments in DT due to the size or possibilities (Barlette & Baillette, Reference Barlette and Baillette2022). This creates some inconsistencies in the literature regarding the impact of clan culture in DT and BDAC. Nonetheless, when the relationship between clan culture and BDAC is mediated by DT, this cultural archetype’s positive influence on BDAC is likely to increase, as supported by previous studies (Pramanik et al., Reference Pramanik, Kirtania and Pani2019; Troisi, Grimaldi, & Loia, Reference Troisi, Grimaldi, Loia, Visvizi, Lytras and Aljohani2021). We hypothesize the following assumptions:

Hypothesis 1: Clan culture has a positive and significant effect on DT.

Hypothesis 2: Clan culture has a positive and significant effect on BDAC.

Hypothesis 3: DT mediates the effect of clan culture on BDAC.

The impact of adhocratic culture on DT and BDAC

Adhocratic culture is the cultural archetype best suited to facilitate an organization’s DT, according to Cameron and Quinn (Reference Cameron and Quinn1999). This archetype is characterized by values such as dynamism, creativity, autonomy, boldness, and the ability to embrace change. Organizations with an adhocratic culture typically display high levels of risk tolerance (Fitzgerald, Kruschwitz, Bonnet, & Welch, Reference Fitzgerald, Kruschwitz, Bonnet and Welch2014), active employee engagement in strategic decision-making (Nicolás-Agustín et al., Reference Nicolás-Agustín, Jiménez-Jiménez and Maeso-Fernández2022), and desire and propensity for adopting new ideas and continuous improvement (Leso, Cortimiglia, & Ghezzi, Reference Leso, Cortimiglia and Ghezzi2023; Xie, Wu, Xie, Yu, & Wang, Reference Xie, Wu, Xie, Yu and Wang2021).

A key strength of this culture is its organizational agility, which involves the ability to detect changes in the environment and mobilize resources quickly to respond (Felipe, Leidner, Roldán, & Leal‐Rodríguez, Reference Felipe, Leidner, Roldán and Leal‐Rodríguez2020). In the context of DT, this agility is crucial, as it enables organizations to rapidly adapt to external threats and opportunities, making timely decisions that maximize the value of data analytics (Barlette & Baillette, Reference Barlette and Baillette2022). The leadership in adhocratic cultures tends to be visionary and bold, characteristics that align well with a data-driven orientation and contribute positively to both DT and the development of BDAC (Akhtar et al., Reference Akhtar, Frynas, Mellahi and Ullah2019; Troisi, Grimaldi, & Loia, Reference Troisi, Grimaldi, Loia, Visvizi, Lytras and Aljohani2021).

Furthermore, the adhocratic culture’s openness to new knowledge is a fundamental component of BDAC (Mikalef et al., Reference Mikalef, Boura, Lekakos and Krogstie2019). Overall, this cultural archetype views change as a positive force and a source of opportunity in today’s dynamic environment (Felipe et al., Reference Felipe, Roldán and Leal-Rodríguez2017), positioning it as an ideal environment for fostering both DT and BDAC.

From the previously literature discussed, we hypothesize the following:

Hypothesis 4: Adhocratic culture has a positive and significant effect on DT.

Hypothesis 5: Adhocratic culture has a positive and significant effect on BDAC.

Hypothesis 6: DT mediates the effect of adhocratic culture on BDAC.

The impact of market culture on DT and BDAC

The market culture is characterized by values such as result-orientation, excellence, competitiveness, pragmatism, and ambition (Cameron & Quinn, Reference Cameron and Quinn1999). This cultural archetype is often found in multinational corporations, consultancies like the ‘big 4,’ and investment banks, where leaders take on managerial and producer roles, driving productivity and emphasizing achievement feedback to workers. Market culture promotes high control, stability, and aggressive competition, which can hinder the DT process and the development of BDAC (Troisi, Grimaldi, & Loia, Reference Troisi, Grimaldi, Loia, Visvizi, Lytras and Aljohani2021; Verhoef et al., Reference Verhoef, Broekhuizen, Bart, Bhattacharya, Dong, Fabian and Haenlein2021).

The core values of stability and control are generally at odds with the flexibility and risk tolerance required for effective DT. The focus on winning, reputation, and success may conflict with the principles of experimentation and failure tolerance that are essential for fostering DT and, subsequently, BDAC. Leal-Rodríguez et al. (Reference Leal-Rodríguez, Sanchís-Pedregosa, Moreno-Moreno and Leal-Millán2023)also argue that values such as competitiveness, pragmatism, and ambition can act as barriers to DT.

However, some literature suggests that market culture’s focus on predicting market trends and understanding competition can enhance organizational agility, aiding in faster decision-making and improving knowledge management (Barlette & Baillette, Reference Barlette and Baillette2022; Felipe et al., Reference Felipe, Roldán and Leal-Rodríguez2017). This, in turn, can reduce uncertainty and improve team effectiveness through control and adherence to deadlines, although the relationship between market culture and DT remains inconsistent across studies.

Proposed research hypotheses regarding market cultural archetype are as follows:

Hypothesis 7: Market culture has a negative and significant effect on DT.

Hypothesis 8: Market culture has a negative and significant effect on BDAC.

Hypothesis 9: DT mediates the effect of market culture on BDAC.

The impact of hierarchy culture on DT and BDAC

According to Felipe, Roldán, and Leal-Rodríguez (Reference Felipe, Roldán and Leal-Rodríguez2016), some attributes related to the hierarchical culture archetype such as the stress on controlling, standardized processes and bureaucratic approaches lead an organization to have more organizational agility. As commented, different studies confirmed the positive relationship between the organizational agility and BDAC (Barlette & Baillette, Reference Barlette and Baillette2022; Dubey et al., Reference Dubey, Bryde, Graham, Foropon, Kumari and Gupta2021), which in turn is also related to a higher level of DT as it enables the option to change, to deal with uncertain environmental factors, and to better adapt to every contingency that the process entails (Ashrafi et al., Reference Ashrafi, Ravasan, Trkman and Afshari2019).

Hierarchy culture is also characterized by its efficiency, and leaders often take on the role of organizers and coordinators of activities and validation of processes. Also, this cultural archetype hides a high level of knowledge management, which can be beneficial for DT in times of crisis and uncertainty, according to Felipe et al. (Reference Felipe, Roldán and Leal-Rodríguez2017). However, there are many values intrinsic to a hierarchical culture that contradict everything previously studied about DT, especially about its micro-foundations and the values needed to achieve it such as formality, coordination, stability, and responsibility (Leal-Rodríguez et al., Reference Leal-Rodríguez, Sanchís-Pedregosa, Moreno-Moreno and Leal-Millán2023). Hierarchical culture has an internal orientation, stability, and is based on power and tradition. It is difficult to change the status quo or processes in companies that base their culture on hierarchy as delegation of tasks, collaboration or speed in processes is not favored (Trenerry et al., Reference Trenerry, Chang, Wang, Suhaila, Lim, Lu and Oh2021). According to some studies such as Hemerling et al. (Reference Hemerling, Kilmann, Danoesastro, Stutts and Ahern2018), innovative firms and digital-oriented firms were less likely to exhibit control and internal direction, fundamental values of this type of culture.

From the previously discussed effects of the relationship between hierarchical culture, DT, and BDAC, we propose the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 10: Hierarchy culture has a positive and significant effect on DT.

Hypothesis 11: Hierarchy culture has a positive and significant effect on BDAC.

Hypothesis 12: DT mediates the effect of hierarchy culture in BDAC

The impact of digital culture on DT and BDAC

The digital cultural archetype was developed based on numerous studies that examined the values of ‘born-digital’ companies and start-ups, which demonstrated strong adaptability to DT and digital environments (Leal-Rodríguez et al., Reference Leal-Rodríguez, Sanchís-Pedregosa, Moreno-Moreno and Leal-Millán2023; Pradana et al., Reference Pradana, Silvianita, Syarifuddin and Renaldi2022; Steiber & Alvarez, Reference Steiber and Alvarez2023). This archetype reflects the characteristics necessary for thriving in a fast-paced digital landscape, including openness to change, risk-taking, agility, entrepreneurship, cooperation, an analytical mindset, and a digital orientation (Firican, Reference Firican2023; Steiber & Alvarez, Reference Steiber and Alvarez2023; Upadhyay & Kumar, Reference Upadhyay and Kumar2020).

Research shows that companies born in the digital era or with disruptive business models often exhibit a high tolerance for risk and failure, which is critical for successfully navigating DT and also to create BDAC. These organizations are built around values that align with rapid adaptability to environmental changes, which is essential for harnessing digital opportunities (Ciacci et al., Reference Ciacci, Balzano and Marzi2024; Hemerling et al., Reference Hemerling, Kilmann, Danoesastro, Stutts and Ahern2018) and maximizing the value of BDAC (Mikalef et al., Reference Mikalef, Krogstie, Pappas and Pavlou2020). Companies with a digital culture emphasize collaboration, sharing information and experiences, and continuous learning, which aligns with the key behaviors needed to adapt to both internal and external demands (Kane et al., Reference Kane, Palmer, Phillips, Kiron and Buckley2015; Vial, Reference Vial2019).

Flexibility and knowledge are crucial in this current historical period. Culture generates knowledge, in this case, digital culture, means entering the renewal process. A successful DT is facilitated by dynamic capabilities and a digital culture (Kane et al., Reference Kane, Palmer, Phillips, Kiron and Buckley2015; Vial, Reference Vial2019), and for BDAC to succeed, a digital culture is crucial (Mikalef et al., Reference Mikalef, Boura, Lekakos and Krogstie2019).

An organization will only acquire the benefits of BDA if the invest sufficient in digital culture and a proper DT framework (Hemerling et al., Reference Hemerling, Kilmann, Danoesastro, Stutts and Ahern2018; Upadhyay & Kumar, Reference Upadhyay and Kumar2020; Wamba et al., Reference Wamba, Queiroz, Wu and Sivarajah2020). The values of this archetype, along with behaviors like adaptability and data interpretation, position organizations for success in a digital environment.

Hypothesis 13: Digital culture has a positive and significant effect on DT.

Hypothesis 14: Digital culture has a positive and significant effect on BDAC.

Hypothesis 15: DT mediates the effect of digital culture on BDAC.

The role of DT on the generation of BDAC

It has been extensively researched that the creation of BDAC is impossible without a specific degree of DT, which is indicated by the amount of digital maturity that a firm achieves (Pramanik et al., Reference Pramanik, Kirtania and Pani2019; Troisi et al., Reference Troisi, Grimaldi, Loia, Visvizi, Lytras and Aljohani2021). This is because, after a minimum of openness, technology, digital mindset, collaboration, and procedures with the necessary infrastructure are in place, the organization must be ready to acquire and cultivate specific competencies linked to BDA such as in Loebbecke and Picot (Reference Loebbecke and Picot2015), Choy and Kamoche (Reference Choy and Kamoche2021) and Orero-Blat et al. (Reference Orero-Blat, Palacios-Marqués, Leal-Rodríguez and Ferraris2024). We may formulate the following study hypothesis and even go so far as to say that DT is a prerequisite for BDAC promotion.

Hypothesis 16: DT has a positive and significant effect on BDAC.

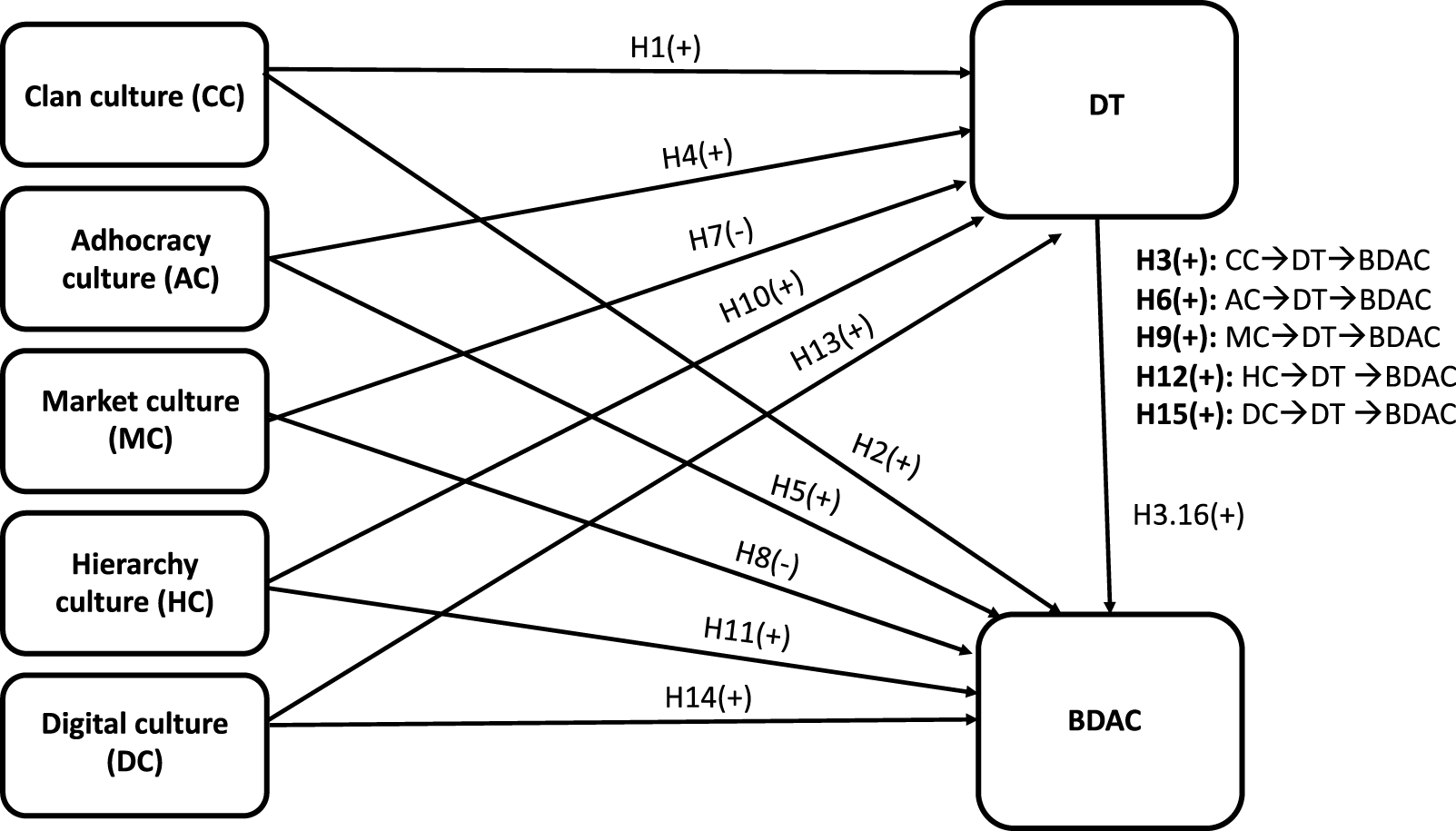

The relationships between the above variables and hypotheses are then graphically represented, resulting in the subsequent research model (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Research model.

Methodology

The research process for this study conducted several steps:

1. Study target definition: To ensure the relevance and accuracy of the data, we established specific criteria for organizations eligible to participate in our survey. Given the early stage of DT among many Spanish companies, we implemented a filter to exclude organizations that were not sufficiently advanced in their DT efforts. Therefore, we set the requirement of an annual turnover exceeding €7 million and a significant engagement in the DT process. Additionally, to ensure the respondents had the necessary expertise, we required that they held managerial roles with proficiency in big data and DT tools. This ensured that both the organization and the respondent were equipped to address the complexities of DT.

2. Sampling: A non-probabilistic convenience sampling method was employed, drawing participants from various Spanish sectors, with a predominance in information technology (28.42%), financial services (15.3%), and logistics (12.02%), followed by non-financial services (6.56%), the metal-mechanical industry (4.37%), and traditional sectors including footwear, textiles, wood, and toy manufacturing (3.83%), as well as tourism (3.83%).

3. Questionnaire development and measures: We used the CVF (Cameron & Quinn, Reference Cameron and Quinn1999) to measure OC, extensively applied across diverse organizational dimensions including agility, human resources, quality management, learning capabilities, and innovation outcomes (Cameron & Quinn, Reference Cameron and Quinn1999; Felipe et al., Reference Felipe, Roldán and Leal-Rodríguez2017; Leal-Rodríguez, Albort-Morant, & Martelo-Landroguez, Reference Leal-Rodríguez, Albort-Morant and Martelo-Landroguez2017). It was supplemented with the digital culture scale by Leal-Rodríguez et al. (Reference Leal-Rodríguez, Sanchís-Pedregosa, Moreno-Moreno and Leal-Millán2023) to incorporate attributes of digital culture. For DT and BDAC, use scales from Nicolás-Agustín et al. (Reference Nicolás-Agustín, Jiménez-Jiménez and Maeso-Fernández2022) and Kim et al. (Reference Kim, Ritchie and McCormick2012), respectively. All scales are detailed in Annex I.

4. Data collection: A total of 183 valid survey responses were collected in July 2022, using a 1- to-7-point Likert scale questionnaire. The demographic distribution was 46% female, 54% male, with 55% aged between 18 and 39 years and 45% between 40 and 66 years. Within the organizational hierarchy, 18.03% were CEOs or general managers, 12.57% were CIOs, and 16.94% were dedicated DT managers, alongside other executive or middle management positions, including COO, CMO, or CFO.

5. Analysis tools: Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM) was used for hypothesis testing. The software SmartPLS v3.2.9 (Ringle, Da Silva, & Bido, Reference Ringle, Da Silva and Bido2015) was employed to estimate the measurement, structural, and predictive model. PLS-SEM is particularly effective for exploring interrelations among latent constructs such as attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors within complex frameworks, making it well-suited for this study’s focus on digital culture’s predictive influence (Hair, Ringle, & Sarstedt, Reference Hair, Ringle and Sarstedt2011). Moreover, it fits perfectly with the exploratory nature of our paper’s objectives among the OC, DT, and BDAC constructs. According to Hair, Sarstedt, Hopkins, and Kuppelwieser (Reference Hair, Sarstedt, Hopkins and Kuppelwieser2014), it is a good fit for examining the connections between latent categories like attitudes, beliefs, and actions in complex systems. Its robustness in handling models with composite constructs has been reinforced through empirical simulations (Felipe et al., Reference Felipe, Leidner, Roldán and Leal‐Rodríguez2020; Leal-Rodríguez et al., Reference Leal-Rodríguez, Sanchís-Pedregosa, Moreno-Moreno and Leal-Millán2023) and previous scholarship (Henseler et al., Reference Henseler, Dijkstra, Sarstedt, Ringle, Diamantopoulos, Straub and Ketchen2014; Rigdon, Sarstedt, & Ringle, Reference Rigdon, Sarstedt and Ringle2017), with its neutrality (Sarstedt, Hair, Ringle, Thiele, & Gudergan, Reference Sarstedt, Hair, Ringle, Thiele and Gudergan2016) and consistency (Rigdon, Reference Rigdon2016) being particularly noted. PLS-SEM is a suitable tool for analysis, since this study also attempts to evaluate the prediction capacity of important components in connection to digital culture.

6. Hypothesis testing: Finally, we analyze the relationships between OC, BDAC, and DT, using PLS-SEM to explore how these constructs interrelate. This could be seen in the following section.

Results

Measurement model

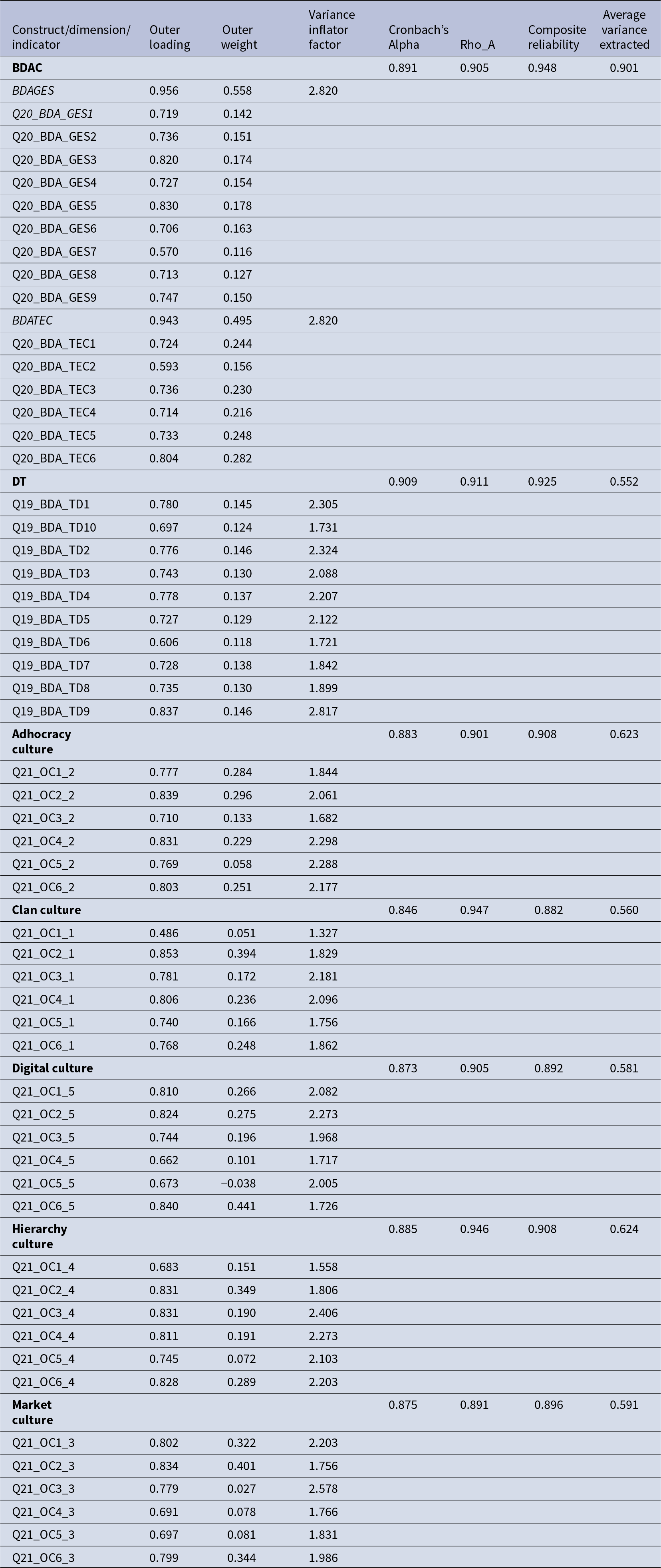

The evaluation of the measurement model should comprise for such constructs the following steps: individual item reliability, composite reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity. Table 1 reveals that most of the items achieve outer loadings of at least 0.891. Construct level assessment confirms that the Cronbach’s α, composite reliability, and Rho A indicators surpass the 0.7 threshold (Hair et al., Reference Hair, Sarstedt, Hopkins and Kuppelwieser2014), substantiating composite reliability. Notwithstanding a few items within the OC falling below this benchmark, the retention of these items is justified in deference to the established validity of the classical OC scale (Cameron & Quinn, Reference Cameron and Quinn1999).

Table 1. Measurement model

Source: Own elaboration from SmartPLS software version 3.2.9 (Ringle et al., Reference Ringle, Da Silva and Bido2015).

Besides, the average variance extracted exceeds 0.5, and therefore the constructs satisfy convergent validity according to the criteria of Fornell and Larcker (Reference Fornell and Larcker1981), which postulates that more than 50% of indicator variance should be accounted for by the construct. Finally, the model attains discriminant validity by applying the Heterotrait-Monotrait (HTMT)approach (Henseler et al., Reference Henseler, Dijkstra, Sarstedt, Ringle, Diamantopoulos, Straub and Ketchen2014).

In the conceptual model, the constructs shaping cultural archetypes as well as BDAC are modeled in formative mode (mode B), while DT is articulated in reflective mode (mode A). This approach aligns with Leal-Rodríguez et al. (Reference Leal-Rodríguez, Sanchís-Pedregosa, Moreno-Moreno and Leal-Millán2023) and is consistent with precedent research that has applied Mode B estimation for cultural archetypes within the OCAI framework (Roldán & Sánchez-Franco, Reference Roldán and Sánchez-Franco2012; Felipe et al., Reference Felipe, Roldán and Leal-Rodríguez2017). Accordingly, discriminant validity analysis is not requisite for formative constructs; however, an assessment of potential collinearity is imperative. The model’s Variance Inflation Factor satisfies the stringent criterion posited by Petter, Straub, and Rai (Reference Petter, Straub and Rai2007), remaining below the benchmark of 3.3. Subsequently, an examination of the weights illustrates the significance and magnitude of each indicator’s contribution to the composite construct (Chin, Reference Chin and Marcoulides1998). This analysis permits a hierarchical classification of indicators based on their contribution magnitudes.

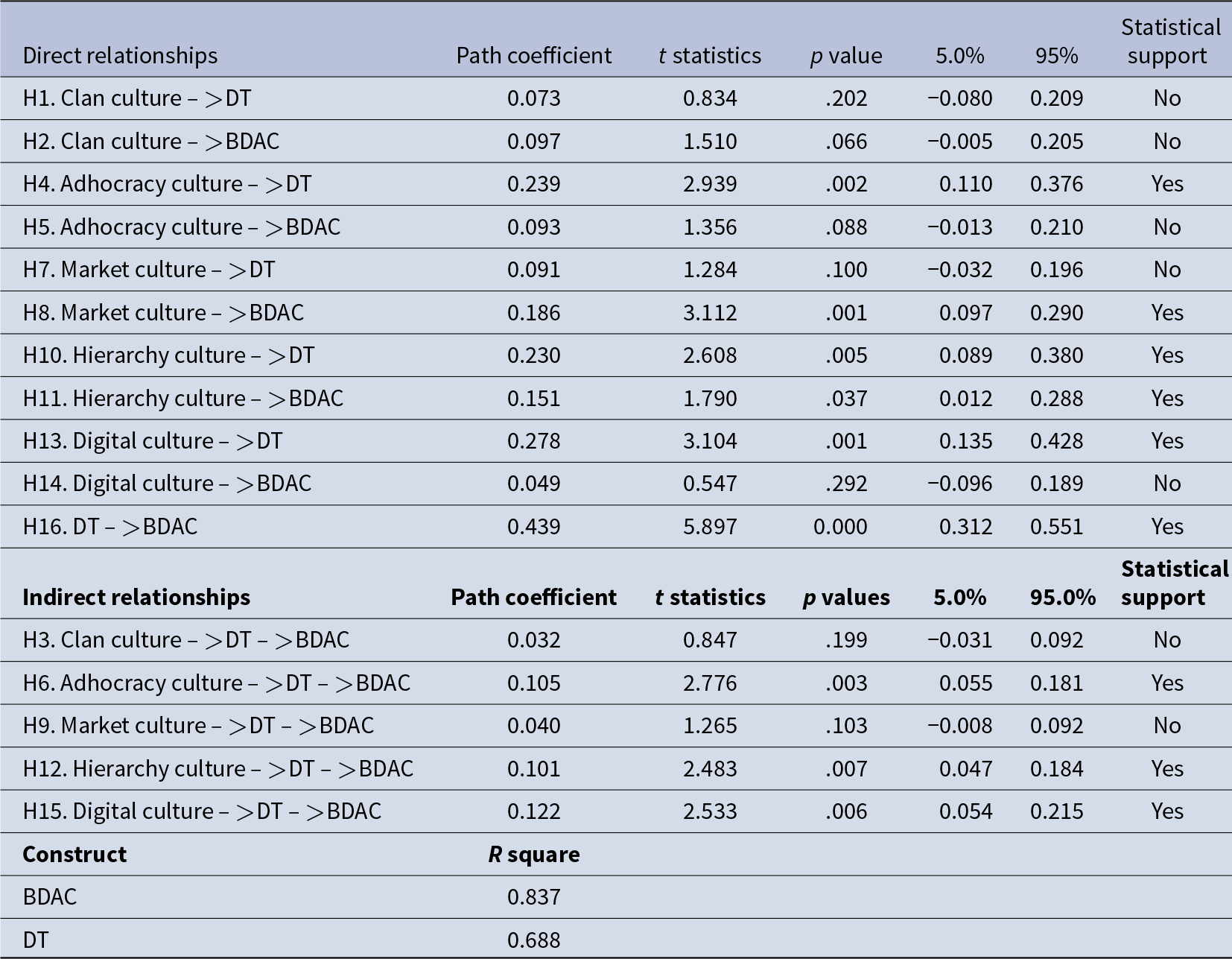

Structural model

Table 2 encapsulates the necessary parameters for the structural model’s evaluation. An initial examination reveals the coefficient of determination (R 2), a measure of the variance explained and indicative of model efficacy, which ideally approaches unity for augmented explanatory power (Chin, Reference Chin and Marcoulides1998). The R 2 values in our study surpass the 0.6 benchmark stipulated by Chin (Reference Chin and Marcoulides1998), denoting a robust explanatory mode.

Table 2. Structural model

Source: Own elaboration from SmartPLS software version 3.2.9 (Ringle et al., Reference Ringle, Da Silva and Bido2015).

The evaluation progresses with an examination of the structural relationships between constructs, scrutinizing the sign, magnitude, and statistical strength of the coefficients. Following the criterion set forth by Hair et al. (Reference Hair, Ringle and Sarstedt2011), a p-value below .05 is indicative of a statistically significant relationship. The analysis confirms significant statistical support for the direct influences of adhocratic culture on DT, market culture on BDAC, hierarchy culture on both DT and BDAC, and digital culture on DT. Additionally, DT demonstrates a significant positive effect on BDAC.

However, the analysis extends beyond direct relationships to consider the nuanced interplay where DT acts as a mediating variable. It is in the investigation of these indirect relationships where the cultural archetypes’ impact on BDAC, as mediated by DT, becomes particularly salient. All hypotheses, save for two concerning clan and market cultures, garner empirical support. This exception suggests that the intrinsic values associated with clan and market cultures do not inherently facilitate DT, nor do they foster the genesis of BDAC within the organization.

It is therefore posited that adhocratic, hierarchical, and digital cultures, when embedded within an organization that has undergone DT, significantly enhance BDAC. These results not only resonate with but also expand upon the findings of prior studies by Felipe et al. (Reference Felipe, Roldán and Leal-Rodríguez2017), Upadhyay and Kumar (Reference Upadhyay and Kumar2020), Wamba et al. (Reference Wamba, Queiroz, Wu and Sivarajah2020), and Leal-Rodríguez et al. (Reference Leal-Rodríguez, Sanchís-Pedregosa, Moreno-Moreno and Leal-Millán2023), providing fresh insights into the academic dialogue. A comprehensive discussion of these findings and their broader implications is forthcoming in the concluding section of this paper.

Predictive analysis

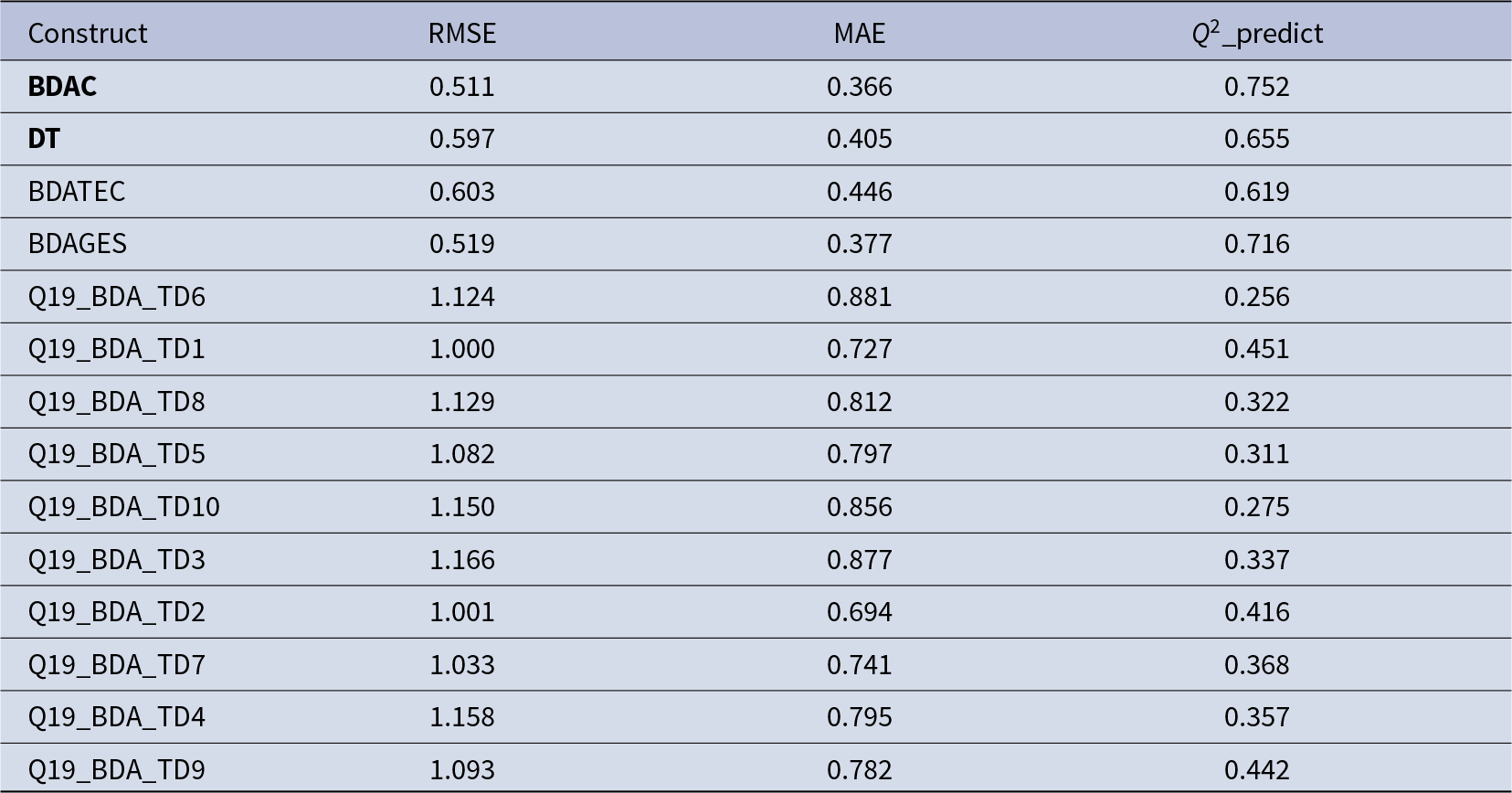

In the concluding segment of our empirical analysis, we appraise the predictive capability of the conceptual model. This evaluation addresses the influence of varying cultural archetypes on DT and BDAC, offering a valuable theoretical and practical contribution. The ability to forecast organizational performance in DT and BDAC creation based on a diagnostic of their OC stands as a significant advancement. To measure the model’s predictive ability, we adhere to the methodology proposed by Shmueli and Koppius (Reference Shmueli and Koppius2011), which advocates for a positive Q2 coefficient at both the construct and indicator levels as evidence of model robustness. Table 3 reveals that this is met in all cases, reaching levels of 0.752 as in the case of BDAC. Thus, the posited model raises predictive ability both at the constructs and indicators levels.

Table 3. Predictive ability

Source: Own elaboration from SmartPLS software version 3.2.9 (Ringle et al., Reference Ringle, Da Silva and Bido2015).

Discussion

Following the line of Warner and Wäger (Reference Warner and Wäger2019), Duerr et al. (Reference Duerr, Holotiuk, Wagner, Beimborn and Weitzel2018), and Pfaff et al. (Reference Pfaff, Wohlleber, Münch, Küffner and Hartmann2023), our findings imply that transformation is a continuous process, demanding ongoing commitment from organizations to cultivate a digital OC conducive to overcoming future challenges. Moreover, our results underscore the necessity for OC to evolve toward managing organizational barriers and structural modifications (Martínez-Caro, Cegarra-Navarro, & Alfonso-Ruiz, Reference Martínez-Caro, Cegarra-Navarro and Alfonso-Ruiz2020; Vial, Reference Vial2019), thereby enabling companies to harness the extensive benefits that arise from DT that could foster innovation.

The results draw attention to the influence each cultural archetype exerts on DT and the promotion of BDAC. A nuanced analysis at the disaggregated level of OC reveals that while all cultural archetypes endorse values conducive to DT and BDAC, the degree of impact varies. Values act as a compass guiding decisions and behaviors within organizations (Clouet et al., Reference Clouet, Leal-Rodríguez, Sanchís-Pedregosa and Orero-Blat2024), and it is the particular values intrinsic to certain cultural archetypes that propel the DT process and the enhancement of BDAC. It is the particular values intrinsic to certain cultural archetypes that propel the DT process and the enhancement of BDAC. Through an analysis of the direct and indirect relationships between cultural archetypes, DT, and BDAC, we conclude that adhocratic, hierarchical, and digital cultures significantly advance BDAC, contingent on the mediating role of DT. These findings diverge from those of Leal-Rodríguez et al. (Reference Leal-Rodríguez, Sanchís-Pedregosa, Moreno-Moreno and Leal-Millán2023) but are in line with different studies such as Ashrafi et al. (Reference Ashrafi, Ravasan, Trkman and Afshari2019), Baiyere, Salmela and Tapanainen (Reference Baiyere, Salmela and Tapanainen2020) and Pradana et al. (Reference Pradana, Silvianita, Syarifuddin and Renaldi2022).

Hierarchical culture leads, thanks to its intrinsic values, to a more agile and adaptable organization, especially in scenarios with high uncertainty or crisis (Felipe et al., Reference Felipe, Leidner, Roldán and Leal‐Rodríguez2020, Reference Felipe, Roldán and Leal-Rodríguez2017), such as the current situation after the COVID-19 crisis and the DT ecosystem. Adhocratic culture is undoubtedly synonymous with openness, dynamism, creativity, agility, and change. Leaders here tend to be visionary and innovative, and the people who form it have training adapted to the needs of the organization (Troisi, Grimaldi, & Loia, Reference Troisi, Grimaldi, Loia, Visvizi, Lytras and Aljohani2021; Xie et al., Reference Xie, Wu, Xie, Yu and Wang2021; Leal-Rodríguez et al., Reference Leal-Rodríguez, Sanchís-Pedregosa, Moreno-Moreno and Leal-Millán2023) that are continuously reviewed and contribute to an increase in organizational capabilities.

Moreover, in our analysis, digital culture emerges as the main driver in fostering BDAC via DT. This is attributed to its foundational values: an openness to change, a learning orientation, an acceptance of failure as a growth mechanism, a focus on analytics, and a strong customer-centric strategy (Leal-Rodriguez et al., Reference Leal-Rodríguez, Sanchís-Pedregosa, Moreno-Moreno and Leal-Millán2023). Such values, hallmarks of digitally native companies, serve as a beacon for those embarking on DT – as in the case study of Steiber and Alvarez (Reference Steiber and Alvarez2023) – and seeking to elevate their analytical capabilities. Yet, it is critical to underscore that the infusion of digital values into a company’s ethos contributes to BDAC generation only when predicated by established DT – thereby positioning DT as a mediating variable in this dynamic.

Innovative and digital cultures are characterized by their emphasis on creativity, flexibility, and a willingness to embrace change. This alignment fosters an environment where continuous improvement, customer feedback, and adaptive learning are integral to successful DT and BDAC (Ciacci et al., Reference Ciacci, Balzano and Marzi2024).

In contrast, market and clan cultures exhibit no marked or significant correlation with BDAC when mediated by DT. Following the work of Akhtar et al. (Reference Akhtar, Frynas, Mellahi and Ullah2019), our results are in line with the results of coercive and manipulative powers who do not favor BDA to impact on increasing innovation. Despite this, the goal-oriented nature of market culture maintains a direct and significant correlation with BDAC. Organizations ingrained with market culture, endeavoring to embark on DT, must recognize the potential complexities of such a transformation. To mitigate these challenges, a concerted effort to foster a learning environment, team development, and, fundamentally, a culture that endorses such transformation is recommended (Leal-Rodríguez et al., Reference Leal-Rodríguez, Sanchís-Pedregosa, Moreno-Moreno and Leal-Millán2023).

Conversely, clan culture is the one that exhibits no favorable association with DT, therefore rejecting hypotheses 1–3. According to Cameron and Quinn (Reference Cameron and Quinn1999), some of the values that characterize the clan cultural archetype are cohesion, organizational commitment, participation, integration, or teamwork. Although these values are typically conducive to HRM innovations that support DT (Bartsch et al. 2020), this premise is not always met. A people-centric archetype, commonly observed in family-run businesses, may be deeply entrenched in tradition, potentially obfuscating strategic foresight. This allegiance to the past can thwart the effective implementation of technological investments and impede the successful initiation of DT and subsequent BDAC creation.

Conclusions

Our study contributes to the academic literature by providing new insights into the relationship between OC and DT. By integrating the digital culture archetype into the CVF, we advance the understanding of how specific cultural traits influence DT and BDAC. Practically, this research highlights the importance of cultural assessment and strategic action planning to foster a conducive environment for DT. This significantly contributes to innovation management, addressing why innovation and digitalization processes often fall short of expectations, and demonstrating how culture can be a lever for change and a key to success if certain recommendations are followed.

This study elucidates several practical implications. First, it emphasizes the importance of diagnosing OC and values to align them with DT requirements. Recognizing the fluid and ongoing nature of corporate culture, conducting an initial cultural assessment and maintaining vigilance through ongoing evaluation are pivotal for digitalization success (Leal-Rodríguez et al., Reference Leal-Rodríguez, Sanchís-Pedregosa, Moreno-Moreno and Leal-Millán2023). This method, based on the concept of competing values (Quinn and Rohrbaugh, Reference Quinn and Rohrbaugh1983), allows professionals to assess their current culture and pinpoint areas that require cultural change as part of the DT process (Pedersen, Reference Pedersen2022).

Once the OC has been diagnosed, the imperative shifts to action planning. This involves identifying and cultivating cultural elements within the organization that are conducive to DT and fostering BDAC. It is important to see whether there are values in the current culture that support digitalization and to establish an action plan. Managing the transition from traditional to innovative and digital cultures requires a strategic approach. According to Cameron and Quinn (Reference Cameron and Quinn2011) and Nanayakkara et al. (Reference Nanayakkara, Wilkinson and Halvitigala2021), recommendations for cultural change can be followed depending on the predominant cultural archetype. For instance, in organizations where clan culture prevails, fostering a reciprocal evaluation ecosystem between management and staff can propel innovation and adaptability. Encouraging intrapreneurship may lead to enhanced performance and spur organizational innovation.

Additionally, following the recommendations of Coco et al. (Reference Coco, Colapinto and Finotto2024), practices associated with open innovation and design thinking (such as workshops and networking events for idea exchange) can be adopted to overcome resistance to DT and BDAC. Employees’ feedback and ideas should be incorporated into strategic decision-making, for example, by creating innovation committees or cross-functional data analytics programs. The creation of multidisciplinary teams and personal training programs is also encouraged for employees based on their aspirations, motivations, and market requirements. In organizations with high market or goal-oriented culture values, practices such as interviewing employees and customers to discover their aspirations and expectations for the company can be introduced. Encouraging openness to the market and implementing a total quality management system will help ease cultural change.

This study, while providing valuable insights, is not without limitations. The use of a non-probabilistic sample poses constraints on the generalizability of our findings, so they should be interpreted with caution. Furthermore, the geographical limitation confines our conclusions to Spanish organizations. Cultural, economic, and technological dynamics can vary significantly across different regions and countries. Therefore, the extent to which these results can be extrapolated to organizations outside of Spain is uncertain. Variations in digital maturity, OC, and the business environment in other regions may lead to different interactions between DT, BDAC, and OC.

To mitigate the issues associated with non-probabilistic sampling, future research could employ probabilistic sampling techniques, ensuring a more representative demographic spread and potentially more generalizable results. Comparative studies across different geographical areas could provide a more comprehensive understanding of the cultural dynamics at play in DT. This would allow exploration of how regional and national cultures impact the adoption and integration of digital technology in business practices.

Future research could focus on the examination of digital mindset as a moderating force in the relationship between employees’ technological skills and proficiency. This inquiry would probe the extent to which a digital mindset, with its intrinsic values of innovation and continuous learning, predicts and enhances the technological competencies of the workforce. By quantifying the influence of digital values on employees’ ability to navigate and master new technologies, scholars could elucidate the symbiotic relationship between cultural environment and technological acumen. Such an investigation might involve longitudinal studies to track the development of technical skills over time within varying digital cultures or cross-sectional analyses to compare proficiency levels across different OCs and contexts (Dąbrowska et al., Reference Dąbrowska, Almpanopoulou, Brem, Chesbrough, Cucino, Di Minin and Ritala2022). Ultimately, this line of research promises to reveal how deeply ingrained digital values within an organization can equip its members to excel in a technology-driven business landscape, offering strategic insights into workforce development and DT policies.

Data availability statement

All data and materials as well as software application or custom code support their published claims and comply with field standards.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Maria Orero-Blat, Antonio Leal Rodríguez and Daniel Palacios Marqués and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding statement

The data collection of this study was funded by ‘Cátedra de Empresa y Humanismo’ of University of Valencia, and the authors want to acknowledge Prof. Tomás Gonzalez Cruz for his help and support along the development of this research.

Conflicts of interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Appendix 1: Questionnaire

For cultural archetypes:

The Organizational Culture AssessmentInstrument (OCAI) allows to capture the underpinning structure of psychological archetypes by identifying key values and assumptions of the enterprise regarding six main dimensions (Cameron & Quinn, Reference Cameron and Quinn1999)

(1) Dominant characteristics: what does the culture look like?

(2) Organizational leadership style

(3) Talent management, how the employees are treated and how is the organizational climate

(4) Organizational glue that holds the enterprise together

(5) Strategic emphasis driving the organizational strategy

(6) Criteria defining parameters for success and rewards policies

The combination of the above-mentioned dimensions explains the big picture of the organizational culture reflected in an enterprise. Numerous studies have been confirming the reliability and validity of OCAI instrument. The psychometrically validated Leal-Rodriguez et al. (Reference Leal-Rodríguez, Sanchís-Pedregosa, Moreno-Moreno and Leal-Millán2023) scale, which reflects the values of digital culture, has been added to this method. Below is the scale used to measure organizational culture in this study, which is measured from 1 to 7.

1 My organization is characterized as..

- A very personal place, almost an extension of my family (OC1_1)

- A very dynamic and entrepreneurial entity. People are willing to bet on their ideas and take risks (OC1_2)

- A very results-oriented entity. People are very competitive and achievement oriented (OC1_3)

- A very hierarchical, formalized, and structured entity. Any activity has pre-established standards and procedures (OC1_4)

- An entity that is very open to change and technological advances (OC1_5)

2 Leadership in my organization..

- It is generally identified with guidance (mentoring), facilitation and support (OC2_1)

- It is characterized by encouraging entrepreneurship, innovation and risk-taking (OC2_2)

- It is characterized by a practical, aggressive, and results-oriented approach (OC2_3)

- It is characterized by promoting coordination, organization, smooth running (operation) and efficiency (OC2_4)

- It is characterized by encouraging analytical thinking and digitalization (OC2_5)

3 The management of people in my organization..

- is characterized by a management style based on teamwork, consensus, and participation (OC3_1)

- It is characterized by promoting individual initiative, risk-taking, innovation and uniqueness (OC3_2)

- It is characterized by promoting a competitive spirit, high demands, and a clear achievement orientation (OC3_3)

- It is characterized by job security, compliance, predictability, and stability in relationships (OC3_4)

- It is characterized by a high willingness to share knowledge (OC3_5)

4 The values shared by the staff of my organization are..

- Loyalty and mutual trust. Commitment to the organization is highly valued (OC4_1)

- Commitment to innovation, development, and continuous change (OC4_2)

- Emphasis on the achievement and attainment of goals or objectives (OC4_3)

- Respect for and compliance with formal standards and policies to maintain the smooth running of the firm (OC4_4)

- Tolerance for failure and data-driven decision making (OC4_5)

5 The strategic priorities in my organization are..

- Individual development, trust, honesty, and participation (OC5_1)

- Acquiring new resources and creating new challenges. Originality and the search for opportunities are appreciated (OC5_2)

- Competitive actions and achievements. Gaining market share is seen as predominant (OC5_3)

- Permanence, stability, efficiency, control, and smoothness of operations are important (OC5_4)

- Extracting value from acquired knowledge and continuous learning (OC5_5)

6 The success criteria in my organization are based on.

- Human Resource development, teamwork, employee commitment and concern for people (OC6_1)

- The development of unique and innovative products or services. We aim to become leaders in production and innovation by. (OC6_2)

- Gaining market share and displacing the competition. Becoming the market leader is the key (OC6_3)

- Efficiency, reliable delivery, refined scheduling and low cost are key (OC6_4)

- Adapting to customer needs and requirements (OC6_5)

For digital transformation:

1. A flexible organizational structure that allows us to deal with the changes brought about by the digital transformation (TD1)

2. Digital components in the products and services offered to customers (TD2)

3. Digital communication channels with our employees, such as corporate portals, WhatsApp groups, digital newsletters, or corporate social networks (TD3)

4. Digital communication channels with our suppliers: digital orders, centralized purchasing, EDIs, etc. (TD4)

5. Digital order forms (EDIs) (include B2B or B2C) of digital applications for internal financial statements or blockchain (TD5)

6. Internal and external digital documentation (TD6)

7. Extraction of information from big data analytics for decision-making (TD7)

1 8 Use of digital surveys to measure customer satisfaction (TD8)

8. Use of digital metrics to measure customer satisfaction: CRM, web visits, visits to digital channels, social media interactions, etc. (TD9)

9. Use of dashboards to analyze the company’s performance (TD10)

For BDAC:

Measuring organization’s technology infrastructure:

1. If we have multiple offices or employees working outside the head office (teleworking, branch offices and mobile devices), they are all connected to the head office to share analytics information (BDA_TEC1)

2. There are no identifiable communication bottlenecks within our organization for sharing analytical information (BDA_TEC2)

3. Software applications can be used simultaneously on multiple analytics platforms (BDA_TEC3)

4. Information is shared seamlessly across our organization, regardless of location (BDA_TEC4)

5. Generic software modules are widely used in the development of new systems (BDA_TEC5)

6. We continually examine innovative opportunities for the strategic use of business analytics (BDA_TEC6)

Measuring management capability:

1. We carry out business analytics planning processes in a systematic way (BDA_GES1)

2. We frequently adjust business analytics plans to better adapt to changing environmental conditions (BDA_GES2)

3. When we make business analysis investment decisions, we estimate the effect they will have on employee work productivity (BDA_GES3)

4. When we make business analytics investment decisions, we project how much these choices will help end users make faster decisions at lower cost (BDA_GES4)

5. In our organization, business analysts and line staff meet regularly to discuss important issues and coordinate efforts (BDA_GES5)

6. In our organization, information is shared widely between business analysts and line staff, so that those making decisions or performing work have access to all available information (BDA_GES6)

7. In our organization, accountability for analytical development is clear (BDA_GES7)

8. We constantly monitor the performance of the analytics function (BDA_GES8)

9. Our company is better than the competition at connecting parties, providing analytical methods, or incorporating detailed information into a business process (BDA_GES9)

Measuring people’s skills:

1. Our analytics staff are very capable in data management and maintenance (BDA_PERS1)

2. Our analytics staff is highly capable in decision support systems (for example in expert systems, artificial intelligence, data warehousing, mining, markets, etc.) (BDA_PERS2)

3. Our analytics staff shows a high capacity to learn new technologies and follow technology trends (BDA_PERS3)

4. Our analytics staff is very knowledgeable about the factors critical to our organization’s success (BDA_PERS4)

5. Our analytics staff is very knowledgeable about the role of business analytics as a means, not an end (BDA_PERS5)

6. Our analytics staff is very capable of interpreting business problems and developing appropriate solutions (BDA_PERS6)

7. Our analytics staff is very knowledgeable about the business environment.

8. Our analytical staff are very capable of executing work in a collective environment and of teaching others (BDA_PERS7)

9. Our analytical staff works closely with clients and maintains productive user-client relationships (BDA_PERS8)

Maria Orero-Blat, PhD, is a Researcher and Lecturer in the Department of Business Management of University of Valencia. She holds an international double degree in International Business and a Master in Innovation Management and Entrepreneurship and Digital Business. Her research focuses on the fields of digital transformation, HR analytics, organizational culture. She has published some research in high-impact journals and participated in international conferences. She has completed international research stays as Visiting Professor in University of Turin (Italy), Napier University Edinburgh (UK) and TEC Costa Rica. Moreover, she is working in international entrepreneurship activities and teaching innovation projects, and she’s also business consultant in collaboration with the spin-off Cultural Fit Solutions.

Antonio L. Leal Rodríguez has more than 35 papers published in high impact scientific journals indexed in the Journal Citation Reports (JCR). His most recent research papers have been published in Decision Sciences, Journal of Knowledge Management, Journal of Business Research, The International Journal of Human Resource Management, Technological Forecasting & Social Change, International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, and International Journal of Project Management, among others. He has presented more than 40 contributions to the most important national and international conferences in his lines of research, such as Academy of Management (AOM), Production and Operations Management Society (POMS), Innovation, Entrepreneurship and Knowledge Academy (INEKA), European Conference on Knowledge Management (ECKM), International Symposium on Partial Least Squares Path Modeling, ACEDE, International Conference on Partial Least Squares and Related Methods, etc. He has a 6-year research period recognized by the CNEAI (ANECA). He has participated as a researcher in four competitive research projects and is co-Director of another one. Conference co-chair of the I Ibero-American Congress of Young Researchers in Economics and Business Management (AJICEDE) held from 22 to 23 November 2018 in Seville (Spain). Visiting researcher at the following universities: Lancaster University Management School (Lancaster, UK), Surrey Business School (Guilford, UK), University of Twente (Enschede, The Netherlands), Universitat Politècnica de València.

Daniel Palacios Marques is Professor of Management at the Technical University of Valencia, Spain. He has published articles in journals such as Tourism Management, Annals of Tourism Research, Small Business Economics, Management Decision, International Journal of Technology Management, Cornell Quarterly Management, Services Industries Journal, Service Business, International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, Journal of Knowledge Management, Journal of Intellectual Capital, International Journal of Computational Intelligence Systems, International Journal of Innovation Management, and International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, Human Resource Management, International Journal of Project Management, Technological and Economic Development of Economy, Journal of Organizational Change Management. He is the Associate Editor of the International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal.