Introduction

Psychotherapy is a key component of comprehensive mental health care [Reference Locher, Meier and Gaab1], proven effective in treating disorders like depression [Reference Cuijpers, Harrer, Miguel, Ciharova and Karyotaki2] and anxiety disorders [Reference De Ponti, Matbouriahi, Franco, Harrer, Miguel and Papola3], as well as helping individuals cope with loss, trauma, and life challenges. With the integration of evidence-based psychotherapy practices into international treatment guidelines [Reference Parikh, Quilty, Ravitz, Rosenbluth, Pavlova and Grigoriadis4, Reference Kendrick, Pilling, Mavranezouli, Megnin-Viggars, Ruane and Eadon5], training in psychotherapy is essential for psychiatrists to expand their therapeutic skills and lead mental healthcare teams [Reference Brittlebank, Hermans, Bhugra, Pinto da Costa, Rojnic-Kuzman and Fiorillo6]. As a result, most psychiatry training programs set minimum requirements for trainees to develop core competencies in psychotherapy.

Psychotherapy skills are generally categorized into three levels: generic, basic practitioner, and advanced. At the generic level, psychiatrists should form a therapeutic alliance and evaluate their emotional reactions with a nonjudgmental attitude. Basic training equips psychiatrists to deliver supervised psychotherapy in one modality and gain knowledge of other major approaches. Advanced training is designed for those with a strong interest in psychotherapy, helping to identify and nurture potential candidates [Reference Holmes, Mizen and Jacobs7].

The World Psychiatric Association (WPA) recommends that training in basic psychotherapy knowledge in the first year, advanced psychotherapy knowledge in the second year, and gaining the skill to be able to deliver effective medium- to long-term psychotherapy during psychiatry training as core competencies [Reference Belfort, Lopez-Ibor, Hermans and Ng8]. In Europe, the European Union of Medical Specialists (UEMS) Board of Psychiatry considers supervised psychotherapy experience a key competency, defining the first level as “learning in psychotherapy” where psychiatrists gain skills to provide psychologically informed mental health services. Psychiatrists should be resilient practitioners, expert communicators, and motivated therapists, building trust with patients and directing them to appropriate psychological treatments [9]. In the United States, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) requires competence in supportive, psychodynamic, and cognitive-behavioral psychotherapies (CBT) [10]. However, despite well-defined guidelines, research showed that psychotherapy training remains challenging in psychiatric education [Reference Brittlebank, Hermans, Bhugra, Pinto da Costa, Rojnic-Kuzman and Fiorillo6]. The WPA reported that nearly half of the member countries did not require psychotherapy training [Reference Ng, Hermans, Belfort and Bhugra11]. Meanwhile, training hours were decreasing, with limited resources and poor implementation of UEMS recommendations across Europe [Reference Gargot, Dondé, Arnaoutoglou, Klotins, Marinova and Silva12].

In the past decade, accreditation bodies like UEMS have promoted learner- and outcome-focused psychotherapy education and training. Studies on psychiatric trainees’ and early career psychiatrists’ (ECPs) perspectives mainly highlight the opportunities and challenges in the current training models, as well as barriers to accessing psychotherapy training. Key barriers include variability and a lack of standardization in training opportunities, and issues with time, funding, and psychotherapy supervision [Reference Gargot, Dondé, Arnaoutoglou, Klotins, Marinova and Silva12–Reference Van Effenterre, Azoulay, Champion and Briffault14].

Objectives

We aimed to evaluate psychiatric trainees’ and ECPs’ interests, views, and available opportunities for psychotherapy training. Given its importance, we hypothesized that psychiatric trainees and ECPs would demonstrate a high interest in psychotherapy despite the variability and a lack of standardization in training. Our review focused on two key questions:

-

1. Were psychiatric trainees and ECPs interested in psychotherapy training?

-

2. What were the rates of psychotherapy training among psychiatric trainees and ECPs, and which types of psychotherapy were most commonly taught?

Methods

The systematic review protocol was registered with the International Prospective Register for Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) on August 4, 2024 (registration number CRD42024566882) and reported following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [Reference Page, McKenzie, Bossuyt, Boutron, Hoffmann and Mulrow15].

Search strategy

Articles were identified through MEDLINE, Scopus, and PubPsych searches with no date or language restrictions. A manual search of reference lists and gray literature further supplemented the database search. Two main search concepts were psychotherapy training and ECP/psychiatric trainee.

Search terms

The following Boolean search terms were used: (((psychiatrist*) OR (psychiatry trainee*) OR (psychiatric trainee*) OR (psychiatry resident*) OR (early career psychiatrist*)) AND ((psychotherapy training) OR (psychiatry training) OR (psychotherapy) OR (psychotherapy practice) OR (psychotherapy education) OR (psychotherapy residency) OR (psychotherapy competency) OR (talking therapy) OR (supervision))).

Eligibility criteria

The inclusion criteria were survey-based studies reporting ECPs’ or psychiatric trainees’ perspectives on psychotherapy training, published in peer-reviewed journals. Studies had to meet methodological and content criteria, with reviews, review protocols, and purely theoretical articles excluded. Only studies in English, French, or Turkish were included. To maintain relevance, we focused on studies published after 2000. Articles on specific psychotherapy modalities or techniques and surveys solely about training directors or supervisors were excluded. Studies were eligible if they included psychiatrists among the surveyed professionals, even if other categories of professionals were also involved.

Study selection and data extraction

The screening process began with a title and abstract assessment using the inclusion and exclusion criteria via the Covidence tool [16]. The primary reviewer (STK) screened all titles and abstracts, identifying potentially relevant articles. Full-text copies of these articles were retrieved and assessed for inclusion, with further exclusion applied as needed. Additional articles were found through citation searching and a gray literature review. Any discrepancies were resolved through consensus among coauthors. Two authors (STK and MD) were involved in the data abstraction process. The PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1) illustrates the search protocol, screening, eligibility, and final selection process.

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram.

Data synthesis

Due to the heterogeneity of the included studies in terms of methods, participants, and survey instruments, a narrative synthesis approach was used. The evidence was summarized and categorized by data origin, participants, key findings, and recommendations in a literature table organized by World Health Organization (WHO)-defined regions [17]. The study results were analyzed and interpreted based on the review’s initial research questions. A comparison between high-income countries (HICs) and low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) was made regarding the main findings.

Quality assessment

The quality of included studies was assessed using the Quality Assessment Checklist for Survey Studies in Psychology (Q-SSP), with studies receiving an acceptable quality score if they met at least 70% of the applicable criteria [Reference Protogerou and Hagger18]. Two reviewers (STK and MD) independently applied Q-SSP, modifying items as needed for study design (see Supplementary Materials). For qualitative studies, the Evaluation Tool for Qualitative Studies was used [Reference Long and Godfrey19].

Results

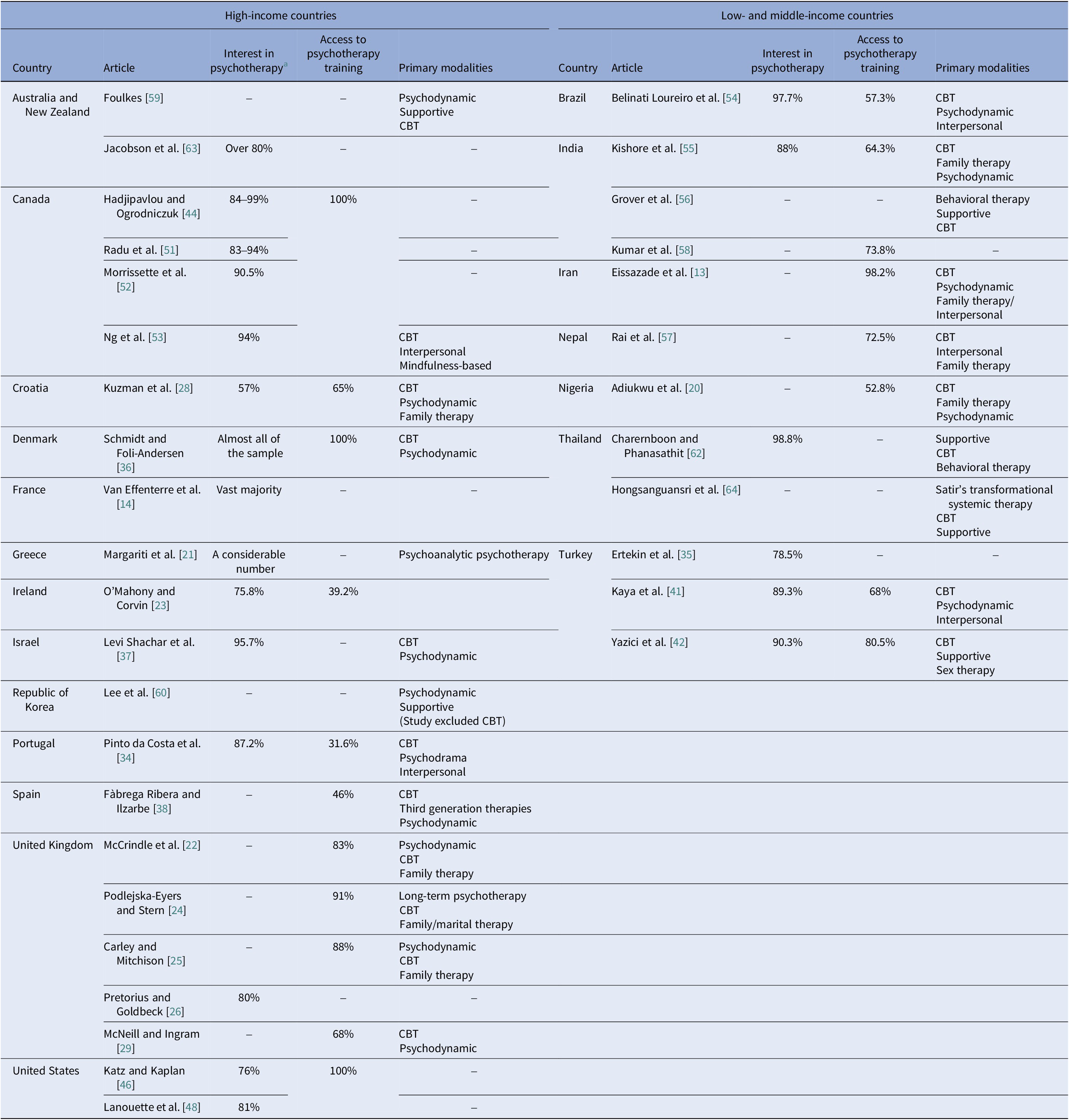

The previously outlined search strategy identified a total of 41,222 articles. After removing 9,994 duplicates, the titles and abstracts of 31,281 studies were screened, and 30,676 were excluded because of irrelevance. Six hundred and five potentially relevant full-text articles were sought for retrieval, among which three were unable to be retrieved. Six hundred and two articles underwent further screening, and 554 were excluded for the following reasons: inappropriate outcomes (n = 126), inappropriate study design (n = 364), or inappropriate participant population (n = 64). Forty-eight articles fulfilled all requirements and were included in this systematic review (Figure 1). Table 1 summarizes the key findings of each included study.

Table 1. Psychotherapy training interest and opportunities literature summary

Abbreviations: CAP, child and adolescent psychiatry; CBT, cognitive behavioral therapy; DBT, dialectical behavior therapy; ECP, early career psychiatrist; EMDR, eye movement desensitization reprocessing; ESCAP, European Society for Child and Adolescent Psychiatry; MDD: major depressive disorder; PT, psychotherapy training; RR, response rate; UEMS, Union Européenne de Médecins Spécialistes-European Union of Medical Specialists.

Among the included studies published between January 1, 2000, and August 1, 2024, 47 reported quantitative results, 3 incorporated qualitative components following the survey [Reference Revet, Raynaud, Marcelli, Falissard, Catheline and Benvegnu40, Reference Katz and Kaplan46, Reference Foulkes59], and 1 had primarily qualitative methodology [Reference Van Effenterre, Azoulay, Briffault and Champion33]. According to the quality assessment of the 47 included studies using Q-SSP, 38 (80.9%) articles demonstrated acceptable quality, while 9 (19.1%) articles had questionable quality (Table 2). Considering a 60% threshold resulting in better consensus between experts [Reference Protogerou and Hagger18], 40 (85.1%) were identified as having acceptable quality. One study with qualitative methodology showed reasonable quality according to the Evaluation Tool for Qualitative Studies. World maps created with mapchart.net demonstrate the results of the quality assessment of each included study (Figure 2).

Table 2. Quality assessment of included studies with Q-SSP

Abbreviations: A, acceptable quality; Q, questionable quality; Q-SSP, quality assessment checklist for surveys in psychology.

Figure 2. Quality assessment of included studies – World Map Charts.

Three-quarters of the studies reported data across the European region (n = 24, 50%) and the region of the Americas (n = 12, 25%). The remaining ones were collected from the Western Pacific region (n = 6, 12.5%), the South-East Asian region (n = 4, 8.3%), the Eastern Mediterranean region (n = 1, 2%), and the African region (n = 1, 2%). All studies evaluated psychiatry trainees’ and/or ECPs’ experiences with psychotherapy training by applying surveys, questionnaires, or semi-structured interviews. The majority of the studies used different, unvalidated questionnaires, mostly developed by the authors. Five (10.4%) studies applied uniform questionnaires titled the World Psychotherapy Survey as part of broader international research [Reference Eissazade, Shalbafan, Eftekhar Ardebili and Pinto da Costa13, Reference Adiukwu, Adedapo, Ojeahere, Musami, Mahmood and Saidu Kakangi20, Reference Kaya, Tasdelen, Ayık and da Costa41, Reference Belinati Loureiro, Ratzke, Nogueira Dutra, Mesadri Gewehr, Cantilino and Pinto Da Costa54, Reference Rai, Karki and Pinto Da Costa57]. The number of respondents for each article varied from 12 to 869. Reported response rates were highly variable, ranging from 2.9 to 100%. A few studies mentioned attrition rates of 5% [Reference Schmidt and Foli-Andersen36], 4.9% [Reference Grover, Sahoo, Srinivas, Tripathi and Avasthi56], and 4.6% [Reference Petersen, Fava, Alpert, Vorono, Sanders and Mischoulon45]. A total of 7,196 participants were represented across studies, of whom 3,780 and 1,456 were indicated as psychiatric trainees and ECPs, respectively. Seven studies were conducted with only senior trainees or specialist registrars, pointing to an advanced level of training or trainees in their last year of training [Reference McCrindle, Wildgoose and Tillett22, Reference Pretorius and Goldbeck26, Reference Fàbrega Ribera and Ilzarbe38, Reference Khurshid, Bennett, Vicari, Lee and Broquet43, Reference Khawaja, Pollock and Westermeyer47, Reference Foulkes59, Reference Lee, Bahn, Lee, Lee, Lee and Park60]. In five studies, representatives of trainee or ECP associations were surveyed regarding the system in their countries of training [Reference Lotz-Rambaldi, Schäfer, ten Doesschate and Hohagen27, Reference Oakley and Malik30–Reference Simmons, Barrett, Wilkinson and Pacherova32, Reference Barrett, Jacobs, Klasen, Herguner, Agnafors and Banjac39]. Child and adolescent psychiatry (CAP) trainees and/or ECPs were included in four studies focusing on psychotherapy training in CAP. Among those, 728 ECPs and 61 representatives of trainee associations were surveyed [Reference Simmons, Barrett, Wilkinson and Pacherova32, Reference Barrett, Jacobs, Klasen, Herguner, Agnafors and Banjac39, Reference Revet, Raynaud, Marcelli, Falissard, Catheline and Benvegnu40, Reference Hongsanguansri, Charatcharungkiat, Alfonso and Olarte64]. One study reported the views of CAP trainees and ECPs as part of the whole group [Reference Kaya, Tasdelen, Ayık and da Costa41]. In the following sections of the article, the term ECP refers to both psychiatry trainees and ECPs, if not otherwise indicated.

Thirty-one of the included studies reported data regarding ECPs’ interest in psychotherapy training. Overall, 57–80% (minimum–maximum) of the participants were interested in psychotherapy training [Reference Van Effenterre, Azoulay, Champion and Briffault14, Reference Lotz-Rambaldi, Schäfer, ten Doesschate and Hohagen27, Reference Kuzman, Jovanović, Vidović, Margetić, Mayer and Zelić28, Reference Ertekin, Ergun and Sungur35, Reference Schmidt and Foli-Andersen36], and 75.8–99% mentioned the importance of such training in becoming fully competent psychiatrists [Reference Gargot, Dondé, Arnaoutoglou, Klotins, Marinova and Silva12, Reference O’Mahony and Corvin23, Reference Yazici, Turker Mercandagi, Ogur, Kurt Tunagur and Yazici42, Reference Hadjipavlou and Ogrodniczuk44, Reference Radu, Harris, Bonnell and Bursey51, Reference Kishore, Shaji and Praveenlal55, Reference Foulkes59, Reference Charernboon and Phanasathit62, Reference Jacobson, Sketcher and Sergejew63, Reference Morrissette, Fleisher, Anang and Harrington52]. ECPs demonstrated a favorable/positive attitude toward psychotherapy training [Reference Schmidt and Foli-Andersen36, Reference Lanouette, Calabrese, Sciolla, Bitner, Mustata and Haak48], and 76–94% were willing to practice or advance it further [Reference Gargot, Dondé, Arnaoutoglou, Klotins, Marinova and Silva12, Reference Yazici, Turker Mercandagi, Ogur, Kurt Tunagur and Yazici42, Reference Hadjipavlou and Ogrodniczuk44, Reference Katz and Kaplan46, Reference Lanouette, Calabrese, Sciolla, Bitner, Mustata and Haak48, Reference Radu, Harris, Bonnell and Bursey51, Reference Ng, Teshima, Tan, Steinberg, Zhu and Giacobbe53, Reference Charernboon and Phanasathit62]. Moreover, 67–92% of the participants tended to consider being a psychotherapist as an integral and valuable part of their identities as psychiatrists [Reference Gargot, Dondé, Arnaoutoglou, Klotins, Marinova and Silva12, Reference Hadjipavlou and Ogrodniczuk44, Reference Lanouette, Calabrese, Sciolla, Bitner, Mustata and Haak48, Reference Radu, Harris, Bonnell and Bursey51]. A considerable proportion of trainees wished for greater exposure to psychotherapy training (54%) and desired to develop a special interest (65%) [Reference Podlejska-Eyers and Stern24, Reference Pretorius and Goldbeck26]. Psychotherapy interest was identified as one of the main factors in choosing to specialize in psychiatry [Reference Revet, Raynaud, Marcelli, Falissard, Catheline and Benvegnu40, Reference Hadjipavlou and Ogrodniczuk44]. ECPs supported that psychotherapy training should be included in psychiatry training (88–97.7%) and it should be an obligatory part of the curriculum (57.2–87.2%) [Reference Eissazade, Shalbafan, Eftekhar Ardebili and Pinto da Costa13, Reference Pinto da Costa, Guerra, Malta, Moura, Carvalho and Mendonça34, Reference Schmidt and Foli-Andersen36, Reference Levi Shachar, Mendlovic, Hertzberg, Baruch and Lurie37, Reference Kaya, Tasdelen, Ayık and da Costa41, Reference Lanouette, Calabrese, Sciolla, Bitner, Mustata and Haak48, Reference Belinati Loureiro, Ratzke, Nogueira Dutra, Mesadri Gewehr, Cantilino and Pinto Da Costa54]. Among numerous psychotherapy modalities, CBT (62.5–100%), psychodynamic psychotherapy (26.3–71.4%), family/systemic therapy (42.5–71.4%), supportive psychotherapy (65.5%), and interpersonal psychotherapy (34.8–44%) were favored to be included in the curriculum to a variable extent [Reference Eissazade, Shalbafan, Eftekhar Ardebili and Pinto da Costa13, Reference Pinto da Costa, Guerra, Malta, Moura, Carvalho and Mendonça34, Reference Yazici, Turker Mercandagi, Ogur, Kurt Tunagur and Yazici42, Reference Belinati Loureiro, Ratzke, Nogueira Dutra, Mesadri Gewehr, Cantilino and Pinto Da Costa54, Reference Jacobson, Sketcher and Sergejew63]. Studies investigating the awareness of ECPs of psychotherapy training guidelines revealed that 51–84% had notice of competence requirements [Reference Gargot, Dondé, Arnaoutoglou, Klotins, Marinova and Silva12, Reference Carley and Mitchison25, Reference Schmidt and Foli-Andersen36, Reference Khurshid, Bennett, Vicari, Lee and Broquet43]. In all, 33–48.8% reported being accredited or meeting the relevant requirements during the evaluation [Reference Pretorius and Goldbeck26, Reference Kaya, Tasdelen, Ayık and da Costa41]. Participants’ self-perceived psychotherapy competence rates were 47–65% [Reference Katz and Kaplan46, Reference Morrissette, Fleisher, Anang and Harrington52, Reference Ng, Teshima, Tan, Steinberg, Zhu and Giacobbe53].

Van Effenterre et al. found that psychiatry trainees viewed psychotherapy as central to their psychiatric identity and saw it as ranging from a strong therapeutic alliance to formal interventions. The psychotherapeutic orientation was diverse, with various modalities enriching psychiatry practice. Trainees expressed a desire for advanced theoretical and practical knowledge to maintain effective psychotherapy skills [Reference Van Effenterre, Azoulay, Briffault and Champion33].

Psychotherapy training rates and opportunities in psychiatry training varied widely across countries, regions, institutions, and even within the same institution. Half of the studies were from Europe, where most countries considered psychotherapy training essential, although its inclusion in programs varied. It was mandatory in Denmark, Germany, Ireland, the Netherlands, Norway, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom [Reference O’Mahony and Corvin23, Reference Pretorius and Goldbeck26, Reference Lotz-Rambaldi, Schäfer, ten Doesschate and Hohagen27], while it was optional in Belgium, France, and Portugal [Reference Fiorillo, Luciano, Giacco, Del Vecchio, Baldass and De Vriendt31, Reference Pinto da Costa, Guerra, Malta, Moura, Carvalho and Mendonça34]. Austria, Israel, Spain, and Turkey recommended it as a core competence and included it in the training to some extent [Reference Lotz-Rambaldi, Schäfer, ten Doesschate and Hohagen27, Reference Levi Shachar, Mendlovic, Hertzberg, Baruch and Lurie37, Reference Kaya, Tasdelen, Ayık and da Costa41]. The most accessible psychotherapy training modalities were CBT and psychodynamic psychotherapy, followed by family/systemic, supportive, and interpersonal psychotherapy [Reference McCrindle, Wildgoose and Tillett22, Reference Podlejska-Eyers and Stern24, Reference Lotz-Rambaldi, Schäfer, ten Doesschate and Hohagen27, Reference McNeill and Ingram29, Reference Oakley and Malik30, Reference Simmons, Barrett, Wilkinson and Pacherova32, Reference Fàbrega Ribera and Ilzarbe38, Reference Kaya, Tasdelen, Ayık and da Costa41, Reference Yazici, Turker Mercandagi, Ogur, Kurt Tunagur and Yazici42]. In studies reporting data from Europe, CBT training was available for 18–95% of the participants [Reference Gargot, Dondé, Arnaoutoglou, Klotins, Marinova and Silva12, Reference McCrindle, Wildgoose and Tillett22, Reference Podlejska-Eyers and Stern24, Reference Lotz-Rambaldi, Schäfer, ten Doesschate and Hohagen27–Reference Oakley and Malik30, Reference Simmons, Barrett, Wilkinson and Pacherova32, Reference Pinto da Costa, Guerra, Malta, Moura, Carvalho and Mendonça34, Reference Ertekin, Ergun and Sungur35, Reference Fàbrega Ribera and Ilzarbe38, Reference Kaya, Tasdelen, Ayık and da Costa41, Reference Yazici, Turker Mercandagi, Ogur, Kurt Tunagur and Yazici42]. Psychodynamic psychotherapy training rates were 8–91% [Reference Gargot, Dondé, Arnaoutoglou, Klotins, Marinova and Silva12, Reference Margariti, Kontaxakis, Madianos, Feretopoulos, Kollias and Paplos21, Reference McCrindle, Wildgoose and Tillett22, Reference Podlejska-Eyers and Stern24, Reference Carley and Mitchison25, Reference Lotz-Rambaldi, Schäfer, ten Doesschate and Hohagen27, Reference Kuzman, Jovanović, Vidović, Margetić, Mayer and Zelić28, Reference Oakley and Malik30–Reference Simmons, Barrett, Wilkinson and Pacherova32, Reference Pinto da Costa, Guerra, Malta, Moura, Carvalho and Mendonça34, Reference Fàbrega Ribera and Ilzarbe38, Reference Barrett, Jacobs, Klasen, Herguner, Agnafors and Banjac39, Reference Kaya, Tasdelen, Ayık and da Costa41], whereas 8.7–81.8% of the samples reported receiving training in systemic/family therapy [Reference Gargot, Dondé, Arnaoutoglou, Klotins, Marinova and Silva12, Reference McCrindle, Wildgoose and Tillett22, Reference Podlejska-Eyers and Stern24, Reference Carley and Mitchison25, Reference Lotz-Rambaldi, Schäfer, ten Doesschate and Hohagen27, Reference Kuzman, Jovanović, Vidović, Margetić, Mayer and Zelić28, Reference Oakley and Malik30–Reference Simmons, Barrett, Wilkinson and Pacherova32, Reference Pinto da Costa, Guerra, Malta, Moura, Carvalho and Mendonça34, Reference Fàbrega Ribera and Ilzarbe38, Reference Barrett, Jacobs, Klasen, Herguner, Agnafors and Banjac39, Reference Kaya, Tasdelen, Ayık and da Costa41]. Other modalities like interpersonal psychotherapy, supportive psychotherapy, group therapy, cognitive-analytical therapy, integrative/eclectic therapy, sex therapy, psychodrama, dialectical behavior therapy, and third-generation psychotherapies were offered to a more limited extent in European programs.

A quarter of the studies included were from the region of Americas. In Canada and the United States, psychotherapy training was a required competency [Reference Zisook, Mcquaid, Sciolla, Lanouette, Calabrese and Dunn49, Reference Morrissette, Fleisher, Anang and Harrington52]. Ng et al. [Reference Ng, Teshima, Tan, Steinberg, Zhu and Giacobbe53] reported that 83% of Canadian trainees received adequate CBT exposure, followed by 39% with interpersonal psychotherapy. In Brazil, psychotherapy training was mandatory in the core curriculum for psychiatry, with 78.6% of participants confirming its inclusion. The most accessible modalities were CBT, psychodynamic, and interpersonal psychotherapy [Reference Belinati Loureiro, Ratzke, Nogueira Dutra, Mesadri Gewehr, Cantilino and Pinto Da Costa54].

Six studies from the Western Pacific Region provided data on psychotherapy training in Australia, New Zealand, the Republic of Korea, Singapore, and Thailand. In Australia and New Zealand, psychotherapy training varied by region and institution [Reference Foulkes59, Reference Jacobson, Sketcher and Sergejew63], with psychodynamic psychotherapy, supportive psychotherapy, and CBT being the most accessible modalities [Reference Foulkes59]. In the Republic of Korea, psychotherapy was a requirement for certification, with 67.4% of the respondent trainees practicing insight-oriented psychodynamic psychotherapy, 28.5% supportive psychotherapy, and 4.2% psychoanalysis [Reference Lee, Bahn, Lee, Lee, Lee and Park60]. Singapore had high trainee interest but lacked standardized competency assessments [Reference Tor, Ng and Kua61]. In Thailand, psychotherapy training availability varied by institution, exacerbating challenges like heavy workloads, lack of confidence, and inadequate training [Reference Charernboon and Phanasathit62]. Notably, Satir’s systemic therapy and Buddhist therapy were among the unique modalities practiced. The most common therapies were supportive psychotherapy (82.9%), CBT (39%), behavioral therapy (35.4%), and Satir’s systemic psychotherapy (32.9%).

Four studies from the South-East Asian region (three from India and one from Nepal) were included. In India, the National Medical Commission highlighted psychotherapy training as essential, but 64.3–73.8% of ECPs reported receiving it [Reference Kishore, Shaji and Praveenlal55, Reference Kumar, Somani, Chandran, Kishor, Isaac and Visweswariah58]. The most common modalities included behavior therapy (90.3%), supportive psychotherapy (87.6%), CBT (86.5%), and motivational interviewing (85.7%) [Reference Grover, Sahoo, Srinivas, Tripathi and Avasthi56]. In Nepal, postgraduate psychiatry training lacked a uniform curriculum, and 67.6% of ECPs reported receiving mandatory psychotherapy training [Reference Rai, Karki and Pinto Da Costa57]. The most accessible modalities were CBT, interpersonal psychotherapy, and family therapy.

There was one study for each region that included the African and Eastern Mediterranean regions. Psychotherapy training was an integral rotation in psychiatry training in Iran [Reference Eissazade, Shalbafan, Eftekhar Ardebili and Pinto da Costa13]. In contrast, in Nigeria, it was not considered one of the mandatory rotations, with limited structured programs to incorporate psychotherapy into psychiatry training [Reference Adiukwu, Adedapo, Ojeahere, Musami, Mahmood and Saidu Kakangi20].

Four studies focused on psychotherapy training during CAP training programs. Revet et al. [Reference Revet, Raynaud, Marcelli, Falissard, Catheline and Benvegnu40] mentioned that 52.8% of CAP trainees chose the specialization due to their interest in psychotherapy. Simmons et al. [Reference Simmons, Barrett, Wilkinson and Pacherova32] reported that 19 of 28 European countries, namely Croatia, Czechia, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Hungary, Ireland, Israel, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, and the United Kingdom, included mandatory psychotherapy training in CAP, with 82% offering both theoretical and practical experience. In Romania, there was no psychotherapy experience available at the time of that study. The most available modalities were CBT (78%), psychodynamic psychotherapy (67%), and systemic therapy (64%) [Reference Simmons, Barrett, Wilkinson and Pacherova32]. The CAP-STATE study showed that 90% of countries taught theoretical psychotherapy topics, with 12 countries requiring practical training in individual psychotherapy with children. Systemic therapy training was provided by almost all countries (n = 27) [Reference Barrett, Jacobs, Klasen, Herguner, Agnafors and Banjac39]. In Thailand, psychotherapy training varied across institutions, with Satir’s transformational systemic therapy (76.3%), CBT (72.9%), and supportive psychotherapy (72.9%) being the most common modalities [Reference Hongsanguansri, Charatcharungkiat, Alfonso and Olarte64].

In studies reporting on psychotherapy training, theoretical training rates ranged from 41.6 to 97.6%, while practical training took place for 35.3–96% of participants [Reference Gargot, Dondé, Arnaoutoglou, Klotins, Marinova and Silva12, Reference Eissazade, Shalbafan, Eftekhar Ardebili and Pinto da Costa13, Reference Adiukwu, Adedapo, Ojeahere, Musami, Mahmood and Saidu Kakangi20, Reference McCrindle, Wildgoose and Tillett22, Reference Podlejska-Eyers and Stern24, Reference Carley and Mitchison25, Reference Lotz-Rambaldi, Schäfer, ten Doesschate and Hohagen27, Reference McNeill and Ingram29, Reference Simmons, Barrett, Wilkinson and Pacherova32, Reference Barrett, Jacobs, Klasen, Herguner, Agnafors and Banjac39, Reference Kaya, Tasdelen, Ayık and da Costa41, Reference Yazici, Turker Mercandagi, Ogur, Kurt Tunagur and Yazici42, Reference Ng, Teshima, Tan, Steinberg, Zhu and Giacobbe53, Reference Belinati Loureiro, Ratzke, Nogueira Dutra, Mesadri Gewehr, Cantilino and Pinto Da Costa54, Reference Rai, Karki and Pinto Da Costa57, Reference Kumar, Somani, Chandran, Kishor, Isaac and Visweswariah58]. Psychotherapy training outside the psychiatry training institute occurred for 24.3–52% of trainees [Reference Gargot, Dondé, Arnaoutoglou, Klotins, Marinova and Silva12, Reference Eissazade, Shalbafan, Eftekhar Ardebili and Pinto da Costa13, Reference McCrindle, Wildgoose and Tillett22, Reference Podlejska-Eyers and Stern24, Reference Carley and Mitchison25, Reference Kuzman, Jovanović, Vidović, Margetić, Mayer and Zelić28, Reference Simmons, Barrett, Wilkinson and Pacherova32, Reference Levi Shachar, Mendlovic, Hertzberg, Baruch and Lurie37, Reference Barrett, Jacobs, Klasen, Herguner, Agnafors and Banjac39, Reference Kaya, Tasdelen, Ayık and da Costa41, Reference Belinati Loureiro, Ratzke, Nogueira Dutra, Mesadri Gewehr, Cantilino and Pinto Da Costa54, Reference Rai, Karki and Pinto Da Costa57, Reference Kumar, Somani, Chandran, Kishor, Isaac and Visweswariah58]. Van Effenterre et al. [Reference Van Effenterre, Azoulay, Champion and Briffault14] stated that 95% of the psychiatry trainees preferred a two-phase training model, combining general theoretical training with in-depth training in a preferred modality, although current models were incompatible. Numerous training techniques, such as case formulations, reading materials, videos, logbooks, and workshops, were reported [Reference Fiorillo, Luciano, Giacco, Del Vecchio, Baldass and De Vriendt31, Reference Khurshid, Bennett, Vicari, Lee and Broquet43]. Kovach et al. [Reference Kovach, Dubin and Combs50] noted that trainees ranked supervision highest among teaching modalities, followed by psychotherapy practice, didactic instruction, readings, and personal psychotherapy.

Funding for psychotherapy training was also a key issue. In Nigeria, 56.5% of ECPs self-funded their training [Reference Adiukwu, Adedapo, Ojeahere, Musami, Mahmood and Saidu Kakangi20]. In Europe, Lotz-Rambaldi et al. [Reference Lotz-Rambaldi, Schäfer, ten Doesschate and Hohagen27] reported that 48% of centers covered all (27%) or part (22%) of the costs, while 46% of training was publicly funded. Where not fully publicly funded, trainees often paid between 2,500 and 10,000 Euros, with some centers charging over 10,000 Euros (in Austria, Switzerland, and Germany) [Reference Lotz-Rambaldi, Schäfer, ten Doesschate and Hohagen27].

Interest in, accessibility to, and training modalities of psychotherapy training were compared between HICs and LMICs using results from 34 studies (Table 3). Others were excluded due to the lack of comparable country data and the fact that they were regional. Our results showed that, despite small discrepancies between countries, there were no significant differences in terms of interest in psychotherapy between HICs and LMICs.

Table 3. Psychotherapy training in high-income versus low- and middle-income countries

Abbreviation: CBT, cognitive behavioral therapy.

a Includes interest in psychotherapy in terms of mentioning the importance of the topic, demonstrating a favorable/positive attitude, willingness to practice, or advance further.

Discussion

Our review of research from the past quarter century confirmed our hypothesis: psychiatry trainees and ECPs exhibit high interest in psychotherapy, which is consistent across different years and healthcare systems globally. However, opportunities for training were inadequate. Despite many ECPs advocating compulsory psychotherapy training in psychiatry, it was not consistently included as a required competency in curricula, except in a few HICs. Even where training was mandatory, significant variations in implementation across institutions and a lack of standardized education were common. Cognitive behavioral therapy and psychodynamic psychotherapies were the primary modalities offered in training.

Psychiatrists are uniquely positioned to integrate the biological and psychosocial aspects of healthcare, with psychotherapy knowledge, skills, and practices being essential to their professional identity. While psychopharmacological treatments have vastly advanced, current treatment algorithms recommend various evidence-based psychotherapy methods for common mental disorders, such as anxiety and depressive disorders [Reference Kendrick, Pilling, Mavranezouli, Megnin-Viggars, Ruane and Eadon5]. Despite the diversity of these different approaches, there is a relatively similar efficacy effect size between psychotherapies. CBT, for instance, is as effective as medication in the short term and more effective in the longer term for depression [Reference Cuijpers, Miguel, Harrer, Plessen, Ciharova and Ebert65]. Psychotherapy is also important for the treatment of severe mental disorders like schizophrenia [Reference Brus, Novakovic and Friedberg66].

Psychotherapy in training guidelines

Psychotherapy training is integral to building therapeutic relationships, which are vital for treatment success, as outlined in UEMS, European Psychiatric Association, and WPA guidelines [Reference Belfort, Lopez-Ibor, Hermans and Ng8, 9, 67]. On the other hand, the UEMS and ACGME guidelines differ significantly in their psychotherapy training requirements. The ACGME mandates psychodynamic therapy, CBT, and supportive therapy for adult psychiatrists but does not require group therapy, systemic therapy, or family therapy [10]. For CAPs, CBT and family therapy are mandatory, while other therapies are recommended. In contrast, UEMS guidelines require all these therapies – psychodynamic therapy, CBT, systemic therapy, group therapy, supportive therapy, and family therapy – for both adult and CAPs [9]. This suggests that UEMS adopts a comprehensive approach, aiming to make therapists proficient in multiple treatment methods, whereas the ACGME provides more flexibility, allowing individual training programs to determine their psychotherapy training.

While no comparative studies directly assess the implementation of UEMS and ACGME criteria, certain challenges in applying both guidelines have been noted. In some European countries, psychotherapy training was still not mandatory, and the high costs associated with training were identified as a major barrier [Reference Lotz-Rambaldi, Schäfer, ten Doesschate and Hohagen27]. Expensive training may deter young psychiatrists from pursuing psychotherapy practice. To address this, psychotherapy training should be integrated into regular working hours, and training costs should be covered by the training institutions or relevant authorities. Ensuring a high standard of education and enhancing the effectiveness of UEMS at the national level are essential steps in improving psychotherapy training. Despite significant variability in the quality and availability of psychotherapy education, the integration of this training into psychiatry programs in many European countries is a notable achievement of the UEMS [Reference Lotz-Rambaldi, Schäfer, ten Doesschate and Hohagen27].

The applicability of the ACGME criteria indeed varied across institutions, highlighting a gap between theoretical guidelines and practical implementation [Reference Khurshid, Bennett, Vicari, Lee and Broquet43]. While most trainees were aware of the qualification criteria, only about one-third believed these criteria were adequately incorporated into the specialty training curriculum. A study focused on psychiatric trainees’ expectations indicated a strong preference for more clinical psychotherapy experience, theoretical training, and supervision activities [Reference Kovach, Dubin and Combs50]. This underscores the need for further work in adapting these criteria to real-world training settings and ensuring that they are effectively implemented. Tailoring the criteria to the realities of psychiatry training programs could enhance the quality of psychotherapy education for trainees.

Global challenges in psychotherapy training

Psychotherapy training faces similar barriers in both high-income HICs and LMICs, although the causes may differ [Reference Jain, Mazhar, Uga, Punwani and Broquet68]. In LMICs, challenges include limited resources, insufficient numbers of psychotherapy instructors, high training costs, and inadequate infrastructure. Psychiatry trainees reported inadequate supervision and discontinuity in training [Reference Hongsanguansri, Charatcharungkiat, Alfonso and Olarte64], and many lacked sufficient support due to financial and time limitations, as well as insufficient supervisory resources [Reference Yazici, Turker Mercandagi, Ogur, Kurt Tunagur and Yazici42]. Cultural and systemic barriers exacerbate these challenges in LMICs. The absence of standardized psychotherapy curricula results in disparities in training quality, adversely affecting clinical practice. For instance, in Nigeria, psychotherapy training often remained insufficient and largely theoretical [Reference Adiukwu, Adedapo, Ojeahere, Musami, Mahmood and Saidu Kakangi20]. In India, many psychiatrists faced gaps in their educational needs, frequently having to complete psychotherapy training independently [Reference Kishore, Shaji and Praveenlal55]. Socioeconomic factors also restrict the practice of psychotherapy after graduation; in Thailand, limited postgraduation supervision led to low confidence among psychiatry trainees, while cultural norms could further impede the acceptance of psychotherapy, reducing patient engagement [Reference Hongsanguansri, Charatcharungkiat, Alfonso and Olarte64].

In HICs, similar obstacles persist, including variability in training curricula, lack of supervised practice, and heavy clinical workloads [Reference Gargot, Dondé, Arnaoutoglou, Klotins, Marinova and Silva12, Reference Van Effenterre, Azoulay, Champion and Briffault14]. In Ireland, while a significant proportion of psychiatry trainees received formal psychotherapy training, it was primarily theoretical, with limited opportunities for supervised practice [Reference O’Mahony and Corvin23]. In the United States, psychiatry trainees valued psychotherapy training, but time and resource limitations prevented them from fully benefiting [Reference Khurshid, Bennett, Vicari, Lee and Broquet43, Reference Katz and Kaplan46]. In Canada, while trainees expressed satisfaction with the quality of supervision, they face difficulties developing therapeutic skills due to heavy clinical workloads and time constraints [Reference Hadjipavlou and Ogrodniczuk44]. In addition, it was observed in the United States that psychiatry trainees’ interest in psychotherapy decreased as they progressed through their training, which was often attributed to institutional barriers, such as lack of supervision and high patient loads [Reference Zisook, Mcquaid, Sciolla, Lanouette, Calabrese and Dunn49]. These findings are in line with decreasing empathy during medical school and residency, which might compromise striving for professionalism that eventually threatens the quality of health care [Reference Neumann, Edelhauser, Taschel, Fischer, Wirtz and Woopen69].

Overall, regardless of the economic context, psychotherapy training is hampered by several systemic challenges, including a lack of supervision, intensive clinical schedules, time limitations, and insufficient funding. These factors hinder psychiatry trainees’ ability to effectively apply psychotherapy skills in their clinical practice postgraduation, thereby affecting their motivation and competence [Reference Lotz-Rambaldi, Schäfer, ten Doesschate and Hohagen27, Reference Simmons, Barrett, Wilkinson and Pacherova32].

Interest in psychotherapy during training

A recently published review article reported that psychiatry trainees tended to lose interest in psychotherapy during the years of training. Dissatisfaction with the quality of psychotherapy curricula, a lack of support, and low self-perceived competence in psychotherapy were among the factors associated with a decreased interest in psychotherapy training [Reference Salgado and von Doellinger70]. In our review, two studies mentioned similar results, indicating that the percentage of trainees interested in psychotherapy or who planned to practice psychotherapy decreased with psychiatry training [Reference Hadjipavlou and Ogrodniczuk44]. This rate was even higher among senior trainees [Reference Zisook, Mcquaid, Sciolla, Lanouette, Calabrese and Dunn49]. Decreased interest in psychotherapy was correlated with personal factors like a lower endorsement of seeing psychotherapy as integral to one’s professional identity, not planning to provide a great deal of psychotherapy to patients, and not planning to pursue additional psychotherapy training. Institutional factors related to decreased interest in psychotherapy included negative attitudes toward the training program and dissatisfaction with the curriculum [Reference Zisook, Mcquaid, Sciolla, Lanouette, Calabrese and Dunn49]. Trainees who felt satisfied with their psychotherapy training were more likely to anticipate practicing psychotherapy after graduation [Reference Hadjipavlou and Ogrodniczuk44]. Moreover, lower self-perceived competence in CBT and psychodynamic psychotherapy correlated with decreased interest in psychotherapy.

Practical recommendations to bridge the treatment gap

Despite the sizable evidence base and all the recommendations in treatment guidelines, there is a significant gap between the availability of effective psychotherapies and the delivery of such interventions in the community [Reference Cook, Schwartz and Kaslow71]. The WHO estimated that 76–85% of people with severe mental illnesses in LMICs and 35–50% in HICs receive no treatment for their conditions, and coverage of evidence-based mental health promotion and prevention approaches is even lower [Reference McGinty, Alegria, Beidas, Braithwaite, Kola and Leslie72]. It can be argued that the burden of health systems on psychiatrists, economic, cultural, and political factors, as well as variations in psychotherapy training, might be prominent factors in this gap. In our study, we found that evidence-based psychotherapies ranked first among the prominent modalities in psychotherapy training worldwide. In addition, types of therapies integrated with each country’s own culture, such as Satir’s systemic therapy and Buddhist therapy in Thailand [Reference Charernboon and Phanasathit62] or family therapy in Iran [Reference Eissazade, Shalbafan, Eftekhar Ardebili and Pinto da Costa13], were among the therapies that were of interest and at the forefront of the relevant training. From a broader perspective, it is recommended that CBT be applied in a culturally adapted way. In this context, one of the essential factors that should be considered for psychotherapy training in psychiatric education is the use of culturally adapted psychotherapy techniques and appropriate training methods.

Recent studies have reported that many psychotherapy methods are effective in the treatment of common mental illnesses and that there are no significant differences in effectiveness between evidence-based therapy modalities despite great differences in the quality of evaluation of this evidence [Reference Cuijpers, Miguel, Ciharova, Harrer, Basic and Cristea73]. To disseminate, develop, and sustain these practices, there is a need for psychotherapy training to continue its existence in institutions providing psychiatric education and to increase standardization by improving the training content. Considering that the need for training and supervision does not end after becoming a specialist, there is a need for programs that can ensure continuity. Perhaps an equally important task falls on professional organizations and associations that support continuous psychiatric education. Contributions of professional organizations in this context include organizing online or face-to-face seminars and workshops, journal clubs, case presentation sessions, regular psychotherapy training programs, or providing training materials, such as the online guidebook of the European Federation of Psychiatric Trainees [74], online courses of the European Psychiatric Association [Reference Gargot, Arnaoutoglou, Costa, Sidorova, Liu-Thwaites and Moorey75, 76], or the WPA’s online learnbook [77]. Keeping training and supervision focused on types of psychotherapy that are effective for mental health conditions is vital in terms of ensuring patients’ access to evidence-based treatment services and preventing potentially harmful practices [Reference Schmidt and Foli-Andersen36]. Initiatives aiming to influence the learning outcomes of future psychiatric specialists, such as the European Board Examination in Psychiatry, which was held for the first time in 2025, could help achieve the goal of better and more accessible psychotherapy education for psychiatrists [Reference Brittlebank, De Picker, Krysta, Seker, Riboldi and Hanon78]. Future studies might evaluate the accessibility, adequacy, and effectiveness of such educational activities.

The limitations of our study include the cross-sectional study designs, medium-low response rates, and potential survey respondent bias, as self-reports may attract those more interested in psychotherapy. The variability in assessment tools and the evolving nature of psychiatric education over the last 25 years made it difficult to draw unified conclusions. In addition, the limited response rates and database selection may have reduced sample diversity, and the exclusion of non-English, French, or Turkish articles may have limited global applicability. Due to the heterogeneity of the data, a meta-analysis with sensitivity analysis was not included, which in turn may have limited the statistical robustness of the conclusions, even though most of the articles consistently reported high interest rates. Publication bias might have occurred in favor of promoting access to and training in psychotherapies, since these surveys could have been made by researchers most interested in psychotherapy and would be filled out by respondents with a similar profile. However, the studies were not funded by commercial interests. Preregistration, as was done by this review, can limit this bias. Beyond reported data, providing administrative teaching and training data would be useful to better understand real-life implementation [Reference McGinty, Alegria, Beidas, Braithwaite, Kola and Leslie72].

Despite these limitations, to our knowledge, this is the first systematic review mapping psychotherapy training opportunities and highlighting possible areas for improvement. It is important to continue psychotherapy training in evidence-based modalities since they have the most evidence in terms of effectiveness across a wide spectrum of mental health conditions. It may also be useful to emphasize training for improving interpersonal skills and nonspecific factors independent of the psychotherapy modality. Further studies may focus on what can be done to increase feasibility and training in evidence-based therapies. Investigating the role of professional organizations and the effectiveness of online training could further enhance education in this field.

Conclusion

Our review highlights a consistent interest in psychotherapy among psychiatry trainees and ECPs. However, despite this interest, the availability and quality of psychotherapy training remain highly variable across countries, regions of the countries, and institutions. This inconsistency poses a significant barrier to equipping future psychiatrists with the necessary skills to deliver evidence-based and culturally appropriate psychotherapeutic interventions.

Addressing this gap requires a coordinated effort. Formal training institutions, regulatory bodies that establish and monitor educational standards, and professional organizations responsible for continuing professional development all play critical roles. It is essential that these actors work together to ensure that psychotherapy training becomes an integral and standardized component of psychiatric education.

In an increasingly globalized world marked by growing mental health needs and complex societal challenges, it is essential to strengthen psychotherapy training. Doing so will not only enhance the competencies of future psychiatrists but also ensure better access to comprehensive mental health care for diverse populations.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1192/j.eurpsy.2025.10044.

Data availability statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this systematic review are available within the article and its Supplementary Materials.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to extend their gratitude to the European Psychiatric Association’s Psychotherapy Section for providing this valuable opportunity and support to collaborate on this work.

Author contribution

Conceptualization: Selin Tanyeri Kayahan, Thomas Gargot, and Jesper Nørgaard Kjær. Methodology: Thomas Gargot and Jesper Nørgaard Kjær. Investigation: Selin Tanyeri Kayahan and Mustafa Dinçer. Writing – original draft: Selin Tanyeri Kayahan. Writing – review and editing: Mustafa Dinçer, Thomas Gargot, and Jesper Nørgaard Kjær. Supervision: Thomas Gargot and Jesper Nørgaard Kjær.

Financial support

The authors have no funding to declare regarding this manuscript. PROSPERO Registration Date and Number: August 4, 2024, CRD42024566882.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.