Introduction

Infective endocarditis in the paediatric population is uncommon, yet a significant cause of morbidity, mortality, and resource utilisation, particularly in the hospital setting. Reference Ware, Tani, Weng, Wilkes and Menon1 Patients with underlying CHD and infective endocarditis are a uniquely challenging population to diagnose and treat, resulting in significant heterogeneity of management strategies and often prolonged hospitalisations. Certain CHD lesions confer a particularly high risk for infective endocarditis, such as complex conotruncal defects and patients repaired with prosthetic material, yet much remains unknown regarding infective endocarditis risk, including the degree of risk conferred by newly developed prostheses, for instance. Reference Cahill, Jewell and Denne2,Reference Kuijpers, Koolbergen and Groenink3 Further complicating diagnosis, imaging modalities used to evaluate for infective endocarditis with structurally normal hearts may be insufficient in CHD. Reference Fowler, Durack and Selton-Suty4–Reference Li, Sexton and Mick6 Standard treatment of infective endocarditis in this group is complicated by a lack of consensus on medical treatment alone versus addition of surgical or transcatheter intervention, and on what timeframe.

Due to the wide spectrum of lesions, variability in clinical practice, and available resources, traditional research designs have resulted in relatively few clinical answers. The Modified Duke Criteria serve as a starting point for diagnosis, but they do not support the full range of decision-making needed in the current era for those practising in cardiothoracic ICUs and acute-care cardiology units. In this setting, collaborative networks such as the Paediatric Acute Care Cardiology Collaborative are well- positioned to create and disseminate management guidelines based on existing literature and expert clinician opinion. Reference Gal, Clyde and Colvin7,Reference Thompson, Foote and King8 Clinical practice guidelines and clinical pathways have been shown to reduce practice variation, facilitate incorporation of up-to-date research into clinical practice, and improve healthcare quality and outcomes. 9,Reference Rotter, Kinsman and James10 Thus, we sought to create an evidence-based clinical practice guideline for clinicians caring for paediatric patients in the hospital setting with underlying CHD and suspected or confirmed infective endocarditis to improve quality of care and reduce practice variability.

Materials and results

The approach to this clinical practice guideline followed the Paediatric Acute Care Cardiology Collaborative’s previously described methods for clinical practice guideline generation. Reference Gal, Clyde and Colvin7

Panel composition

The Paediatric Acute Care Cardiology Collaborative convened a 22-member panel from 17 United States-based and one Canada-based institutions with expertise in paediatric cardiology and infective endocarditis, including general paediatric cardiologists who practice in outpatient and acute-care settings, advanced imaging cardiologists, heart failure/transplant cardiologists, adult congenital cardiologists, interventional cardiologists, paediatric cardiothoracic surgeons, advanced practice providers, pharmacists with expertise in cardiology and infectious disease, paediatric infectious disease physicians, paediatric intensive care physicians, and a paediatric dentist. This panel was tasked with reviewing the literature and existing infective endocarditis management protocols and then formulating recommendations.

Target audience and scope

The intent of this clinical practice guideline is to provide guidance on hospital-based management of suspected or confirmed infective endocarditis in infants, children, and adolescents with CHD. The intended audience is any healthcare provider who cares for such patients. Infective endocarditis in the absence of CHD, infective endocarditis related to cardiovascular implantable electronic devices or leads (e.g. pacemakers, implantable cardiac defibrillators), infective endocarditis specifically in the cardiac transplantation population, outpatient antimicrobial management, and the specifics of and rationale for infective endocarditis antimicrobial prophylaxis are outside of the scope of this clinical practice guideline.

Evidence review

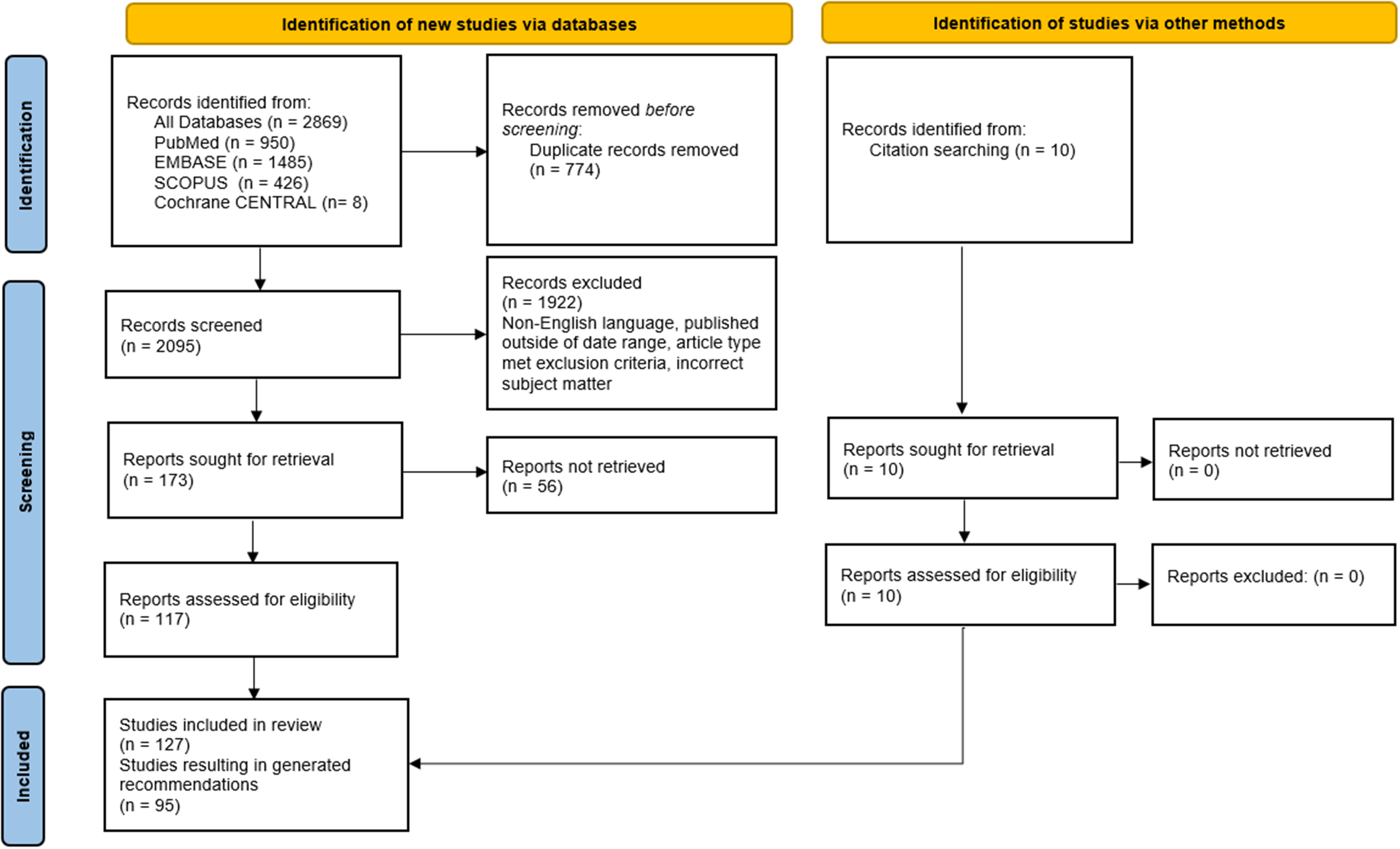

The panel determined the scope, key questions, and inclusion criteria for the evidence review. The literature was searched using PubMed, SCOPUS, EMBASE, and Cochrane CENTRAL (Supplementary Table 1). Articles were excluded if they were published prior to the year 2008 or were not available in English. Case reports, case series, editorials, letters, commentaries, book chapters, and reviews were also excluded. Search results and article retrieval are detailed in Figure 1. Searches were conducted on 6 January 2023. References from searched articles were also considered and included if they met the above criteria. Search criteria included terms related to the paediatric population, but resulting adult data were included if the studies offered reliable, robust data. Articles addressing specifically adult CHD patients were included if they studied topics not addressed in paediatric-only studies. Articles were categorised by broad topics, and each article was reviewed by at least two panellists from different centres. Database searches resulted in 2,869 articles, 774 of which were duplicates. Further screening resulted in 127 eligible articles, which were reviewed in full for inclusion. Delphi rounds were completed over 17 months between January 2023 and June 2024. To ensure that no relevant new evidence had been generated in the period since the initial literature search was performed, the same search was performed following completion of the Delphi rounds on 19 August 2024 (Supplementary Table 1 and Figure 1). After screening titles and abstracts of all resulting articles, only six additional articles met screening criteria and were reviewed in full by the first and senior authors. These articles were deemed to support the Delphi-generated recommendations without new data to support modification of the established recommendations. Citations were included where appropriate to support recommendations or discussion points.

Figure 1. Results of literature search. Date of search: 1/6/2023.

In addition to the published literature review, panellists were contacted and invited to share any existing site-specific protocols at their representative institutions. These protocols were reviewed after completion of the Delphi literature review. Panel members had the opportunity to generate recommendations based on expert opinion including their overall clinical experience, if not otherwise addressed in the literature.

Grading of the evidence and recommendations

The panel rated the quality of evidence and the strength of recommendation using methods described by the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation Working Group. Reference Guyatt, Oxman and Vist11 The quality of evidence was rated as high, moderate, low, or very low. The strength of the recommendation was rated as strong or weak. Generally, the quality-of-evidence assessment is based on the study design, study limitations, and the criticality of outcomes. Recommendations based on high-quality evidence are unlikely to change in the future, even if new research is published. In contrast, recommendations based on low or very low-quality evidence have a high likelihood of changing in the future based on new evidence. The strength of recommendation is based on how clearly the potential benefits of the recommendation outweigh the potential risks or harms of not following the recommendation. For weak recommendations, choosing whether to follow them must be based on consideration of individual circumstances, including personal preferences and values of patients and clinicians. A strong strength of recommendation does not necessarily correlate with high quality of evidence, and vice versa. If a recommendation is supported by multiple articles with differing levels of quality of evidence or strength of recommendation, the highest quality of evidence and strength of recommendation are reported. For recommendations based on expert opinion, for which there is not any available peer-reviewed literature, the quality of evidence is denoted as “EO,” and the strength of recommendation is based on the panel consensus. No recommendations were based solely on adult data.

Guideline development process

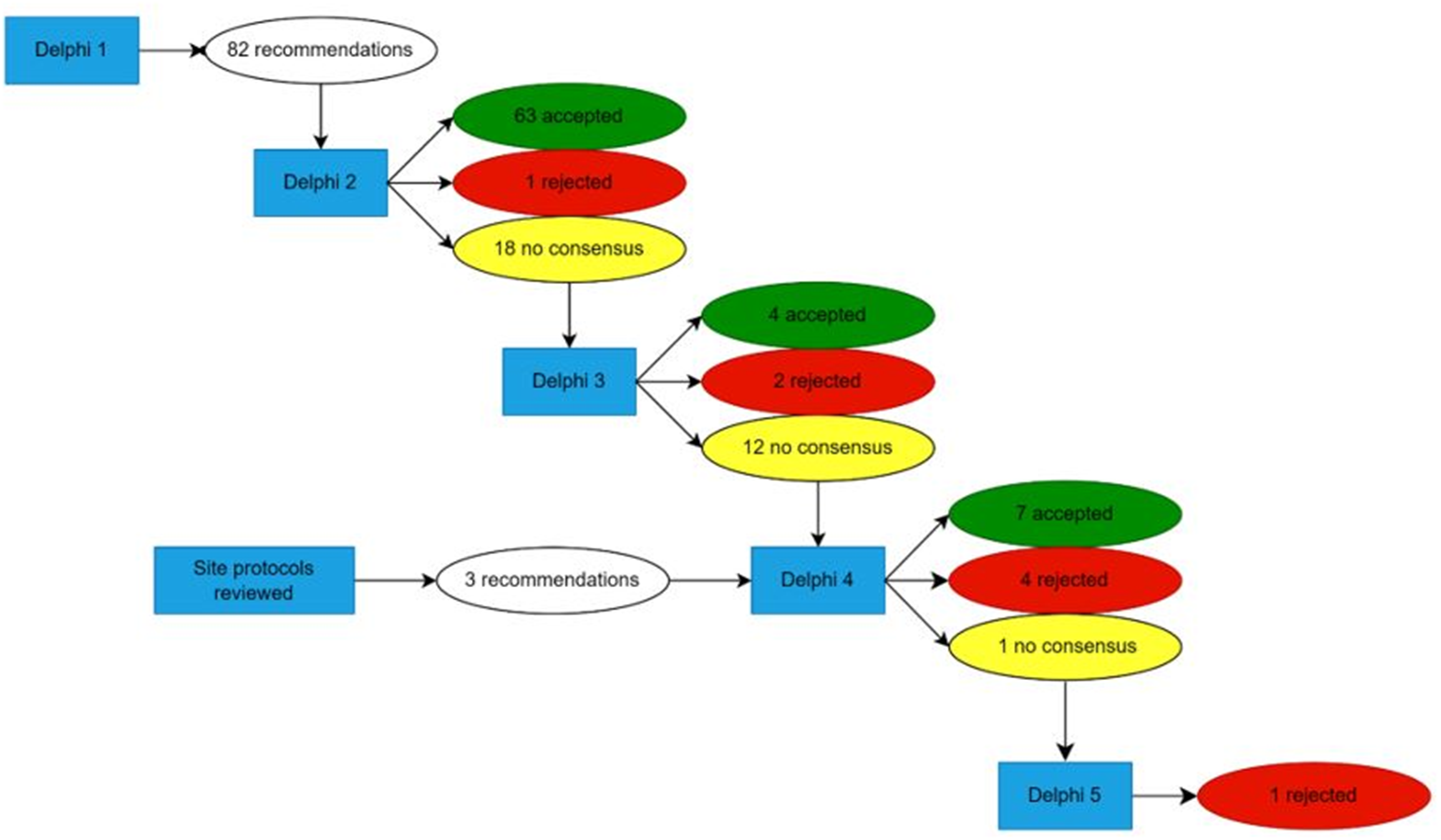

The panel met virtually in December 2022. The scope and key definitions were agreed upon during that meeting. A modified Delphi technique was established. Reference Hasson, Keeney and McKenna12 For Round 1 of the Delphi, panellists reviewed a subset of the identified literature (as described above) and created an initial set of potential recommendations. Of the 127 included articles, 95 served as the basis for potential recommendations, which were voted on in Delphi Round 2. After analysis of the results of Delphi Round 2, site-specific protocols were distributed to panellists. This was intentionally completed after evidence review to limit bias when assessing the literature. Rounds 3 and 4 of the Delphi focused on expert recommendations and literature-based recommendations that had not previously achieved consensus. In each Delphi round, panellists reflected and were asked to vote on recommendation content as well as the quality of evidence and strength-of-recommendation designation. In total, five Delphi rounds were completed, and 73 recommendations were accepted (Figure 2). In subsequent review, 23 recommendations were felt to be repetitive, non-contributory, or outside the scope of the clinical practice guideline and were removed. For all Delphi rounds after Round 1, consensus was defined as greater than two-thirds majority and was required for approval or rejection of recommendations, but the panel aimed for unanimity or near unanimity. Three panellists reported conflicts of interest as consultants and proctors for Edwards Lifesciences and Medtronic. Two panellists reported a conflict of interest related to the review of an article they had authored and, therefore, recused themselves from generating recommendations from said articles. One panellist assisted in generating recommendations following Delphi Round 1 but was excused from further participation due to unrelated circumstances. Otherwise, all panellists voted on all recommendations.

Figure 2. Results of Delphi Rounds. Twenty-three recommendations were removed after completion of the Delphi rounds as they were felt to be repetitive or non-contributory.

The panel finalised the recommendations in June 2024. Once recommendations were finalised, the guideline was drafted and reviewed by all panellists for editing. Once panellists agreed upon the written guideline, it was shared with the Paediatric Acute Care Cardiology Collaborative Executive Committee, comprised of 27 members from 17 centres in North America for peer review. After another round of revisions among the panel, the guidelines were finalised and submitted for external peer review.

Recommendations

General epidemiology and causative pathogens

Abbreviations: IE, infective endocarditis; CHD, congenital heart disease; RHD, rheumatic heart disease.

Generating management protocols for paediatric infective endocarditis is complicated by dynamic shifts in epidemiology in recent decades and variable risk of infective endocarditis based on an individual’s underlying physiology and comobordities. Reference Baltimore, Gewitz and Baddour34 Whereas rheumatic heart disease was previously recognised as the most common underlying heart condition in paediatric patients with infective endocarditis, the relative incidence of infective endocarditis related to CHD is increasing and has surpassed rheumatic heart disease-related infective endocarditis in many regions. Reference Li, Wang, Wang, Pu and Zhao13,Reference Rosenthal, Feja, Levasseur, Alba, Gersony and Saiman14,Reference Baltimore, Gewitz and Baddour34 CHD now represents the most common underlying condition in children with infective endocarditis greater than two years of age in developed countries. Reference Baltimore, Gewitz and Baddour34,Reference Elder and Baltimore35 Longitudinal studies have demonstrated a higher proportion of paediatric patients with infective endocarditis and underlying CHD, attributable in part to advances in percutaneous and surgical CHD interventions leading to improved survival. Reference Li, Wang, Wang, Pu and Zhao13,Reference Rosenthal, Feja, Levasseur, Alba, Gersony and Saiman14,Reference Day, Gauvreau, Shulman and Newburger18 Awareness of this shift in epidemiology is important for clinicians caring for these patients, as it affects not only suspected causative pathogens but also informs counselling and education for families.

Nevertheless, clinicians must still consider the higher prevalence of rheumatic heart disease in low- and middle-income countries and the risk for infective endocarditis it confers, including among patients who have emigrated to high-income countries, irrespective of CHD status. Reference Kumar and Bhatt26,Reference Gupta, Jagadeesan, Agrawal, Bhat and Nanjappa36,Reference Tesfay, Weldu and Ebrahim37 Additionally, the clinical presentation of infective endocarditis may appear different in low- and middle-income countries when compared to high-income countries. Reference Gupta, Jagadeesan, Agrawal, Bhat and Nanjappa36 While these nuances are important for clinicians to consider, this panel did not generate recommendations related solely to infective endocarditis in the context of rheumatic heart disease, as it was outside of the determined scope.

Understanding the most implicated causative pathogens is crucial to effective treatment of infective endocarditis in patients with CHD. Despite the aforementioned shifts in incidence of infective endocarditis with underlying CHD, evidence supports that Staphylococcus and Streptococcus species are the most common causative pathogens in infective endocarditis, regardless of geographic location. Reference Cahill, Jewell and Denne2,Reference Rosenthal, Feja, Levasseur, Alba, Gersony and Saiman14,Reference Tseng, Chiu and Shao16–Reference Xu X.Y., Chen, Guo, Fu, Gao and Yu32 Although there is some discrepancy in the literature, several studies support that among patients with CHD, viridans group streptococci are the most commonly implicated pathogens followed by Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus), other Streptococcus species, and then other Staphylococcal species. Reference Gupta, Sakhuja, McGrath and Asmar22,Reference Kelchtermans, Grossar and Eyskens25 While there is insufficient evidence to generate recommendations, it is important to be aware of less commonly implicated causative pathogens, including Enterococcus species, Gram-negative bacilli of the HACEK group (Haemophilus species, Aggregatibacter species, Cardiobacterium hominis, Eikenella corrodens, and Kingella species), and fungal species which can also cause infective endocarditis in CHD. Reference Baddour, Wilson and Bayer38

Infective endocarditis does not affect cardiac structures uniformly in patients with underlying CHD. Underlying anatomy, physiology, and palliation influence which structures are most at risk of infective endocarditis. Particularly, clinicians must consider the role of implanted foreign material, which increases the risk of infective endocarditis in patients with CHD. Reference Weber, Berger and Balmer33 Foreign implanted material is a notably broad term and can include synthetic patches, endovascular stents, occluder devices, vascular plugs, vascular coils, and foreign biologic material ranging from homografts and xenografts to vascular conduits made of varying synthetic materials. One study, which specifically evaluated the risk of infective endocarditis in children with CHD who had undergone intervention with implanted foreign material, found that, unlike those who had not received implantation of foreign material, Staphylococcus species were the most frequently isolated organisms. Reference Weber, Berger and Balmer33 This finding is not surprising given the organism’s known ability to adhere to foreign biologic material and create difficult-to-treat biofilm.

High-risk populations

Abbreviations: CHD, congenital heart disease; IE, infective endocarditis.

Irrespective of an individual’s specific form of CHD, there are additional risk factors which may be considered when assessing risk for infective endocarditis. It is well established that a prior history of infective endocarditis confers an increased risk of recurrent episodes. Reference Snygg-Martin, Giang, Dellborg, Robertson and Mandalenakis39–Reference Fox, Carvajal, Wan, Canter, Merritt and Eghtesady42 Further, large population-based cohort studies from countries with national registries have demonstrated an association between male sex and infective endocarditis in broad populations as well as those specifically with underlying CHD. Reference Thornhill, Jones and Prendergast40,Reference Sun, Lai and Wang43 This may be related to an association between severe forms of CHD and male sex. Reference Pugnaloni, Felici, Corno, Marino, Versacci and Putotto47 Age of the patient may also be considered, with some studies showing that younger patients ages 0–3 years, and particularly infants, are at increased risk of infective endocarditis compared to older paediatric cohorts. Reference Dolgner, Arya, Kronman and Chan45,Reference Rushani, Kaufman and Ionescu-Ittu46 The impact of young age may be multifactorial, including that infants may have prolonged initial hospitalisations, sometimes in intensive care units with exposure to additional infective endocarditis risk factors such as indwelling intravenous catheters. Reference Sun, Lai and Wang43

Bovine jugular vein grafts have been associated with higher rates of infective endocarditis than other types of grafts and conduits. Reference Mery, Guzman-Pruneda and De Leon48 While some consider the presence of this material an independent risk factor, there is controversy regarding whether the material itself is more prone to infective endocarditis than other prosthetic materials or whether the patient population for whom bovine jugular vein grafts have been selected have concomitant infective endocarditis risk factors in and of themselves such as age and size. Reference Haas, Bach and Vcasna49–Reference Hascoet, Bentham and Giugno53 Further discussion on this topic is in the Transcatheter Pulmonary Valve Replacement Considerations section.

Post-procedural and -operative risk

Abbreviations: IE, infective endocarditis.

Individuals who have undergone cardiac surgery and certain transcatheter procedures are at an increased risk for the development of infective endocarditis, particularly within the first 6-12 months following the intervention. Reference Sun, Lai and Wang43,Reference Rushani, Kaufman and Ionescu-Ittu46,Reference Wilson, Taubert and Gewitz55,Reference Morris, Reller and Menashe56 This important risk factor is multifactorial, with the process of surgery itself, including its use of central vascular catheters, for instance, conferring at least some of the increased risk. Implantation of foreign and/or prosthetic material further increases the chance of infection, with the highest risk in the initial six post-procedural months prior to completion of endothelialization around such material. Reference Jortveit, Klcovansky, Eskedal, Birkeland, Dohlen and Holmstrom24,Reference Weber, Berger and Balmer33,Reference Sun, Lai and Wang43,Reference Rushani, Kaufman and Ionescu-Ittu46,Reference Mylotte, Rushani and Therrien54,Reference Wilson, Taubert and Gewitz55 A large population-based cohort study of adults with CHD demonstrated an increased risk of infective endocarditis occurring within six weeks from invasive genitourinary, gastrointestinal, or respiratory tract diagnostic or therapeutic procedures. Reference Mylotte, Rushani and Therrien54 Notably, subacute bacterial endocarditis prophylaxis is not currently recommended prior to these procedures, though remains outside of the scope of this clinical practice guideline. Appropriate counselling to patients and families is therefore strongly recommended pre- and post-operatively to educate on heightened risk and signs and symptoms for which to monitor. While not corroborated by other studies, one single-centre multi-era study in the United States noted an increase in rates of early post-operative infective endocarditis over the last two decades. Reference Rosenthal, Feja, Levasseur, Alba, Gersony and Saiman14

CHD as a risk factor

*Includes dental procedures for which IE prophylaxis is reasonable.

Abbreviations: CHD, congenital heart disease; IE, infective endocarditis; TOF, Tetralogy of Fallot; PVR, pulmonary valve replacement; RV-PA, right ventricle to pulmonary artery; TPVR, transcatheter pulmonary valve replacement; PSG, peak systolic gradient.

It is well established that CHD is a leading risk factor for infective endocarditis. Reference Eleyan, Khan and Musollari19,Reference Johnson, Boyce, Cetta, Steckelberg and Johnson23,Reference Kelchtermans, Grossar and Eyskens25–Reference Mahony, Lean and Pham27,Reference Willoughby, Basera and Perkins30,Reference Xu X.Y., Chen, Guo, Fu, Gao and Yu32,Reference Elder and Baltimore35,Reference Snygg-Martin, Giang, Dellborg, Robertson and Mandalenakis39,Reference Verheugt, Uiterwaal and van der Velde41,Reference Havers-Borgersen, Butt and Ostergaard57,Reference Havers-Borgersen, Butt and Smerup58,Reference Marin-Cruz, Pedrero-Tome and Toral66 The pathophysiology of infective endocarditis in the setting of CHD stems from several factors. Abnormal cardiac structures can generate turbulent high-velocity blood flow, such as with stenotic or regurgitant valves, leading to damaged cardiac endothelium. The subsequent host response of platelet and fibrin deposition on these sites serves as a vulnerable nidus for bacterial or fungal colonisation. Reference Baltimore, Gewitz and Baddour34 Similarly, hyperviscosity and polycythaemia secondary to chronic hypoxia are another possible mechanism. Reference Havers-Borgersen, Butt and Ostergaard57,Reference DeFilippis, Law, Curtin and Eckman67 Alternatively, direct infection of an indwelling device, such as a prosthetic valve or central venous catheter, is a potential source. Understanding CHD as a risk factor for infective endocarditis is complex given the heterogeneity of lesions and the varying risks associated with whether an individual’s defect(s) is repaired, the presence of residual lesions, and whether palliation requires prosthetic materials.

While it is imperative for clinicians to recognise the inherent risk of infective endocarditis for their patients with all forms of CHD, certain lesions and interventions may confer an especially high risk of infective endocarditis. Tetralogy of Fallot is one of the highest risk lesions, particularly following pulmonary valve replacement. Reference Havers-Borgersen, Butt and Smerup58 Patients with tetralogy of Fallot may be cyanotic at birth, undergo one or more surgeries during early childhood, and often require pulmonary valve replacement by early adulthood. Further, tetralogy of Fallot is often associated with 22q11 deletion syndrome and associated immunodeficiency. These factors, coupled with the current high survival rate of patients with tetralogy of Fallot into adulthood, create a population with multiple infective endocarditis risk factors at varying time points in their lives. Reference Dennis, Moore, Kotchetkova, Pressley, Cordina and Celermajer68

Additional lesions associated with a particularly high risk for CHD-related infective endocarditis include other conotruncal defects such as truncus arteriosus, transposition of the great arteries, univentricular heart lesions, and atrioventricular septal defects. Reference Rushani, Kaufman and Ionescu-Ittu46 With regard to univentricular lesions, hypoplastic left heart syndrome and other left ventricular outflow obstructive lesions are high risk. Reference Verheugt, Uiterwaal and van der Velde41,Reference Rushani, Kaufman and Ionescu-Ittu46 Cyanosis has been identified as a risk factor for the development of infective endocarditis; however, its precise mechanism remains unclear and may be multifactorial. Reference Rushani, Kaufman and Ionescu-Ittu46 Cyanosis could increase infective endocarditis risk due to the presence of elevated haematocrit and hyperviscosity, the fact that those with cyanosis at birth are more likely to undergo palliation with prosthetic material, and the potential for reduced pulmonary immuno-filtration with residual right-to-left shunting in those with unrepaired cyanotic lesions. Reference Willart, Jan de Heer and Hammad69 In addition, micro-organisms adherent to vegetations on left-sided lesions may be less vulnerable to typical host defences. Reference Wilson, Taubert and Gewitz55 While some CHD lesions confer a higher infective endocarditis risk than others, even simple forms of CHD such as bicuspid aortic valves and unrepaired ventricular septal defects impart a greater risk compared to those without CHD and clinicians should counsel patients and families accordingly. Reference Kazmi, Shah, Kazmi, Kazmi and Hyder59–Reference Mendel and Siagian63,Reference Yang, Ye and Wajih Ullah70

Irrespective of an individual’s underlying CHD lesion, those with valvular disease who undergo primary valvuloplasty, those who have undergone valve replacement with a prosthetic valve, palliation with a shunt, and placement of a conduit in the pulmonary position should be considered high risk. Reference Yakut, Ecevit, Tokel, Varan and Ozkan31,Reference Thornhill, Jones and Prendergast40,Reference Havers-Borgersen, Butt and Smerup58 It is this panel’s expert opinion that clinicians should maintain a particularly high index of suspicion for infective endocarditis in individuals who have undergone placement of a right ventricular to pulmonary artery conduit with a history of prior infective endocarditis, two or more conduit replacements, recent procedure with known risk for infective endocarditis, concomitant skin infection, 22q11 deletion syndrome, transcatheter pulmonary valve replacement at 12 years of age or younger, or post- transcatheter pulmonary valve replacement peak systolic gradient of >15 mmHg. Reference Wilson, Taubert and Gewitz55 The latter risk factors related to transcatheter pulmonary valve replacement will be further discussed in the subsequent section Transcatheter Pulmonary Valve Replacement Considerations.

As more individuals with complex CHD survive into adulthood, it is important for clinicians to acknowledge how the risk of infective endocarditis changes over their lifetime. While patients who undergo complete repair without residual defects may carry standard risk for infective endocarditis over time, those who undergo repair with residual defects or palliated CHD remain at elevated risk. Reference Knirsch and Nadal64 Those with CHD repaired or palliated with prosthetic material including valve-containing prosthetics and/or persistent cyanosis carry the highest risk. Reference Kuijpers, Koolbergen and Groenink3,Reference Baek, Park, Woo, Choi, Jung and Kim65,Reference DeFilippis, Law, Curtin and Eckman67

Transcatheter pulmonary valve replacement considerations

Abbreviations: IE, infective endocarditis; TPVR, transcatheter pulmonary valve replacement; PVR, pulmonary valve replacement; EO, expert opinion; RV-PA, right ventricle to pulmonary artery; TTE, transthoracic echocardiography; RVOT, right ventricular outflow tract; PSG, peak systolic gradient; BJV, bovine jugular vein.

Transcatheter pulmonary valve replacement, first performed in 2000, is an increasingly common non-surgical intervention to treat right ventricular outflow tract obstruction or pulmonary valve regurgitation in anatomically suitable patients. Reference Bonhoeffer, Boudjemline and Saliba75 It is widely accepted that individuals who have undergone pulmonary valve replacement are at increased risk of infective endocarditis. Factors including patient selection, underlying anatomy and hemodynamics, and the material of prosthetic pulmonary valve have made it challenging to definitively determine if the risk of IE is higher for transcatheter placed versus surgically placed pulmonary valve replacement. This topic is a dynamic field, as there is a growing body of prospective studies closely following the incidence of infective endocarditis in those who have undergone transcatheter pulmonary valve replacement. Reference Tanase, Ewert and Hager76,Reference McElhinney, Zhang and Aboulhosn77

Factors to consider in those who have undergone transcatheter pulmonary valve replacement include demographic features such as an individual’s age and size, immune status, and hemodynamic state of the right ventricular outflow tract at the time of transcatheter pulmonary valve replacement. Current literature suggests that younger age, specifically ≤12 years, at the time of transcatheter pulmonary valve replacement increases risk of infective endocarditis following transcatheter pulmonary valve replacement with the Melody® valve. Reference Sadeghi, Wadia and Lluri72 The heightened risk of infective endocarditis in this age group is not completely understood, yet it stands to reason that younger patients are typically smaller in size than adults, which may translate to smaller dimensions of their native pulmonary valve or right ventricular to pulmonary artery conduit valve annulus. A smaller native annulus or conduit size may limit the size of the transcatheter valve to be implanted in the pulmonary position, potentially leading to higher residual gradient post-implantation, which is a risk factor for infective endocarditis. Reference McElhinney, Sondergaard and Armstrong71,Reference Sadeghi, Wadia and Lluri72 Based on the risk in this younger population, this panels finds that it is reasonable to consider clinical interventions aimed at right ventricular to pulmonary artery conduit gradient reduction without transcatheter pulmonary valve replacement where appropriate or consideration of surgical conduit replacement, as an alternative to transcatheter pulmonary valve replacement. Reference McElhinney, Sondergaard and Armstrong71 However, the strength of recommendation remains weak given that restriction of this therapy from this age group may place these individuals at higher risk of other co-morbidities otherwise avoided with percutaneous interventions if ultimately undergoing surgical pulmonary valve replacement.

The role of immune status in the development of infective endocarditis post-transcatheter pulmonary valve replacement is important to consider, although the quality of evidence on this topic is limited. Existing literature suggests that immunocompromised individuals, particularly those with higher residual gradients following transcatheter pulmonary valve replacement are at increased risk for infective endocarditis. Reference Sadeghi, Wadia and Lluri72 The specifics of what forms of immunodeficiency confer what degree of infective endocarditis risk have not been fully delineated, but it is reasonable to consider those with an underlying syndrome predisposing to infection (such as 22q11 deletion syndrome), chronic neutropenia, or use of immunomodulator/immunosuppressive agents to fall within this subgroup. Further, determining the best clinical practices in response to this poorly defined risk factor is challenging. Transthoracic echocardiography is considered the gold standard for initial diagnostic cardiac imaging when evaluating for any form of infective endocarditis, yet screening for vegetations in the right ventricular outflow tract may be challenging. This panel’s recommendation that clinicians may consider heightened vigilance with screening transthoracic echocardiography for immunocompromised patients post-transcatheter pulmonary valve replacement is weak as it may lead to unnecessary testing in a subgroup which remains to be better defined.

Right ventricular outflow tract peak gradient ≥15 mmHg immediately post-transcatheter pulmonary valve replacement appears to be a risk factor for the development of subsequent infective endocarditis in the right ventricular outflow tract. Reference McElhinney, Benson, Eicken, Kreutzer, Padera and Zahn73 This increased risk is due to increased flow velocity, turbulence, and shear stresses across a stenotic valve which can damage valve leaflets and create a nidus for microthrombus deposition and microorganism propagation. Reference Sadeghi, Wadia and Lluri72,Reference McElhinney, Benson, Eicken, Kreutzer, Padera and Zahn73 As such, it is reasonable for cardiac interventionalists to target an immediate post-implant right ventricular outflow tract gradient of <15 mmHg at the time of Melody® transcatheter pulmonary valve replacement. Reference McElhinney, Sondergaard and Armstrong71 Further, clinicians may consider interventions aimed at further gradient reduction when the right ventricular outflow tract peak gradient is ≥15 mmHg. Reference McElhinney, Benson, Eicken, Kreutzer, Padera and Zahn73 Clinicians may consider surgical conduit replacement, if it is unlikely that the post-transcatheter pulmonary valve replacement right ventricular outflow tract gradient will be <15 mmHg. Reference McElhinney, Benson, Eicken, Kreutzer, Padera and Zahn73 Importantly, these recommendations carry a weak strength of recommendation given that there may be significant adverse effects of attempting to decrease a right ventricular outflow tract gradient to <15 mmHg. For instance, the use of aggressive balloon expansion to achieve this gradient may lead to coronary artery compression or conduit rupture, which would necessitate surgical conduit replacement. Multiple studies have suggested an increased incidence of infective endocarditis in bovine jugular vein tissue in the right ventricular outflow tract including the Melody® valve and the Contegra conduit. Reference Houeijeh, Batteux and Karsenty52,Reference Hascoet, Bentham and Giugno53,Reference Lehner, Haas and Dietl78–Reference Van Dijck, Budts and Cools80 It is important to recognise that these valves have been preferentially implanted into small, stenotic right ventricular outflow tract conduits and small, young patients over other types of bioprostheses. The relatively increased risk of infective endocarditis with bovine jugular vein grafts may be a result of selection bias reflecting the hemodynamic and anatomic milieu into which these valves are placed rather than a predilection for infection of the bovine jugular vein tissue itself. Therefore, it is imperative that clinicians consider the multitude of factors that play into the risk of infective endocarditis in a patient who has undergone placement of a valve-containing bovine jugular vein tissue.

Further, chronic anti-platelet therapy following transcatheter pulmonary valve replacement may mitigate the risk of infective endocarditis. While this mechanism remains unclear, a prospective study of patients undergoing transcatheter pulmonary valve replacement found a significant prevalence of infective endocarditis among those who had abrupt discontinuation of their anti-platelet therapy, typically related to an upcoming invasive procedure. Reference Malekzadeh-Milani, Ladouceur and Patel81

Diagnostic considerations in the Modified Duke criteria

Abbreviations: MDC, Modified Duke Criteria; IE, infective endocarditis; CHD, congenital heart disease; TTE, transthoracic echocardiography; TEE, transesophageal echocardiography; PET/CT, positron emission tomography/computerised tomography; ICE, intracardiac echocardiography; RV-PA, right ventricle to pulmonary artery; RVOT, right ventricular outflow tract.

Diagnosing infective endocarditis can be challenging, particularly in individuals with CHD. The Duke criteria, originally published in 1994, modified in 2000, and most recently updated in 2023, were initially intended to be utilised for research and epidemiology; however, this document now serves as contemporary consensus diagnostic criteria for clinicians. Reference Fowler, Durack and Selton-Suty4–Reference Li, Sexton and Mick6 The most recent updates highlight several topics also addressed in the creation of this clinical practice guideline, notably the important diagnostic role of advanced imaging modalities in conjunction with echocardiography. The 2023 Duke-International Society for Cardiovascular Infectious Diseases Infective Endocarditis Criteria now include cardiac CT findings of “vegetation, valvular/leaflet perforation, valvular/leaflet aneurysm, abscess, pseudoaneurysm, or intracardiac fistula” as Imaging Major Criteria, identical to those findings found by echocardiography. Reference Fowler, Durack and Selton-Suty4 Similarly, findings of “abnormal metabolic activity involving a native or prosthetic valve, ascending aortic graft (with concomitant evidence of valve involvement), intracardiac device leads, or other prosthetic material” greater than three months following cardiac surgery by positron emission tomography/CT imaging are included in Imaging Major Criteria and considered equivalent to positive findings by echocardiography. Reference Fowler, Durack and Selton-Suty4 This panel additionally wishes to recognise that in patients who have undergone transcatheter pulmonary valve replacement, the Modified Duke Criteria may underperform due to the poor sensitivity of transthoracic echocardiography alone, and thus utilisation of transesophageal echocardiography, positron emission tomography/CT, and intracardiac echocardiography may increase the sensitivity of the Modified Duke Criteria. Reference Bos, De Wolf and Cools74 Further recommendations and discussion regarding advanced cardiac imaging modalities are included in subsequent sections.

Careful consideration of the heightened risk of infective endocarditis in those who have undergone implantation of a surgical or transcatheter pulmonary valve replacement is important. Recognising that the quality of evidence is very low, this panel recommends that in patients with a right ventricular to pulmonary artery conduit or pulmonary valve bioprosthesis and possible infective endocarditis, clinicians should not exclude the diagnosis of infective endocarditis if the Modified Duke Criteria are not fully satisfied. This panel proposes that, in addition to the already established Imaging Major Criteria, positive findings identified by CT, positron emission tomography/CT, or intracardiac echocardiography should be included, if transthoracic echocardiography or transesophageal echocardiography is negative. Reference Bos, De Wolf and Cools74 Further, this panel proposes including the presence of new or increased right ventricular outflow tract gradient across an existing right ventricular to pulmonary artery conduit/bioprosthesis unexplained by a structural complication, such as stent fracture, as an additional minor criterion in the Modified Duke Criteria. Reference Bos, De Wolf and Cools74,Reference Malekzadeh-Milani, Ladouceur and Patel81 This recommendation stems from the strong association described between right ventricular outflow tract infective endocarditis and elevated right ventricular outflow tract gradients in those who have undergone transcatheter pulmonary valve replacement. Reference Malekzadeh-Milani, Ladouceur and Patel81 It should be acknowledged that in addition to structural complications, transient changes in hemodynamics (including tachycardia, changes in pulmonary vascular resistance, volume status, etc.) may also alter right ventricular outflow tract gradients. Nevertheless, because infective endocarditis confers high potential for morbidity and a high degree of clinical suspicion is needed, it is important to consider infective endocarditis in the setting of an increased gradient, even if other entities may be contributing.

It is also important for clinicians to weigh the additional diagnostic value of advanced cardiac imaging modalities when Modified Duke Criteria have already been met by echocardiography. One single-centre study of adults with a definitive diagnosis of left-sided infective endocarditis confirmed by perioperative inspection evaluated the diagnostic agreement between transesophageal echocardiography and cardiac CT for detection of valvular and paravalvular lesions. Reference Sifaoui, Oliver and Tacher83 This study found that transesophageal echocardiography performed better than cardiac CT for detection of vegetations and similar to cardiac CT for the detection of paravalvular abscesses and pseudoaneurysms. Reference Sifaoui, Oliver and Tacher83 These findings may be explained by the higher temporal resolution and contribution of colour Doppler in transesophageal echocardiography which improves detection of vegetations and valvular erosion, respectively. Reference Sifaoui, Oliver and Tacher83 Although significantly limited by quality of evidence, this panel recommends clinicians consider whether cardiac CT is necessary to make the diagnosis or alter treatment of infective endocarditis, particularly when weighing the potential risks of radiation exposure. Importantly, though, clinicians must consider which specific cardiac structures or extracardiac structures are suspected to be involved in a case of infective endocarditis when determining which imaging modalities are appropriate to utilise, especially in surgical planning. For instance, cardiac or chest CT may also be useful in the identification of vascular phenomena such as septic thromboembolism or to evaluate for complications such as lung abscesses. In these instances, cardiac CT may not be necessary for diagnosis, but it is additive in the comprehensive evaluation of a patient. This panel does not wish to devalue diagnostic modalities such as cardiac CT, which may be valuable in surgical decision-making and planning. The Modified Duke Criteria in its current form does not include the role of abnormal biomarkers such as C-reactive protein or procalcitonin in the diagnosis of infective endocarditis. Given the existing challenges of diagnosis of infective endocarditis in those with CHD, additional research regarding the utility of biomarkers in prognostication of infective endocarditis in paediatric patients with CHD should be pursued. Reference Sahulee and Chakravart84,Reference Verhagen, Hermanides and Korevaar85 Importantly, the Modified Duke Criteria are designed for broad application across all patient populations, while this panel and clinical practice guideline focused on those with CHD. It is unsurprising that there are additional considerations not addressed by the Modified Duke Criteria.

Diagnostic challenges

Abbreviations: BCNE, blood culture-negative infective endocarditis; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; IE, infective endocarditis; BJV, bovine jugular vein.

When positive, blood cultures are one of the best methods to identify causative pathogens and tailor treatment of infective endocarditis. As such, blood cultures, specifically systems with antibiotic-binding resins, should be utilised in the diagnosis of infective endocarditis. Reference Camitta, Geme, Li, Da Cruz DI and James88 Nevertheless, blood culture-negative infective endocarditis is common and accounts for up to a third of all cases of infective endocarditis. Reference Zahringer, Konijn, Baliga and Munro89 Such cases pose significant management challenges given the inability to tailor antimicrobial treatment to a specific organism. A large prospective study evaluating blood culture-negative infective endocarditis cases found that polymerase chain reaction analysis on valvular biopsies, when possible, significantly improved detection of micro-organisms otherwise not identified by culture or polymerase chain reaction blood samples. Reference Fournier, Thuny and Richet86 While not specific to those with underlying CHD, emerging evidence suggests that in the setting of blood culture-negative infective endocarditis, serologic analysis using immunofluorescence assays should be utilised given their high return of diagnoses, predominantly for Coxiella burnetii or Bartonella species. Reference Fowler, Durack and Selton-Suty4,Reference Fournier, Thuny and Richet86

Though it is challenging to attribute infective endocarditis risk specifically to bovine jugular vein tissue rather than to underlying hemodynamic and anatomic factors, a large single-centre study identified bovine jugular vein material in valved right ventricular to pulmonary artery conduits to be a significant risk factor for infective endocarditis. Reference Mery, Guzman-Pruneda and De Leon48 Further, among cases of infective endocarditis with bovine jugular vein valved conduits, 40% of cases had negative blood cultures. Reference Mery, Guzman-Pruneda and De Leon48 Therefore, even in the setting of negative blood cultures, those who have undergone pulmonary valve replacement with bovine jugular vein material should be considered at a heightened risk for infective endocarditis. Reference Kelchtermans, Grossar and Eyskens25,Reference Mery, Guzman-Pruneda and De Leon48,Reference Sharma, Cote, Hosking and Harris50,Reference Dixon and Christov87

Diagnostic cardiac imaging-echocardiography, CT, MRI, positron emission tomography, intracardiac echocardiography

Abbreviations: TTE, transthoracic echocardiography; IE, infective endocarditis; TEE, transesophageal echocardiography; CT, computerised tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PET/CT, positron emission tomography/computerised tomography; ICE, intracardiac echocardiography.

It is widely accepted that two-dimensional echocardiography should be performed in all patients as the first-line cardiac imaging modality in the evaluation of suspected infective endocarditis. Reference Baltimore, Gewitz and Baddour34 Transthoracic echocardiography is non-invasive, widely available where paediatric acute care is delivered, poses no significant risk to the patient, and can identify potentially severe complications of infective endocarditis. While transthoracic echocardiography has limited sensitivity in detecting infective endocarditis complications in adults, it can effectively detect findings of infective endocarditis in children with up to 97% sensitivity in those weighing <60 kg. Reference Kini, Logani and Ky97,Reference Penk, C., Shulman and Anderson98 Transthoracic echocardiography can be used to identify vegetations, evaluate for valvular involvement, and evaluate for complications such as chordae tendinea rupture, valve perforation, and paravalvular abscess. Reference Yuan, Liu, Hu, Zeng, Zhou and Chen90

In one relatively small single-centre retrospective review of largely paediatric patients who underwent surgical pulmonary valve replacement, the majority of patients with a bioprosthetic pulmonary valve and infective endocarditis had evidence of vegetation by transthoracic echocardiography, with only a small percentage requiring additional evaluation via transesophageal echocardiography to identify a vegetation. Reference Robichaud, Hill and Cohen91 While transesophageal echocardiography generally provides better visualisation of cardiac structures as compared to transthoracic echocardiography, transthoracic echocardiography may have advantages in imaging more anterior structures such as the right ventricular outflow tract, and these imaging modalities should be used to complement each other in the evaluation of suspected pulmonary valve infective endocarditis. Reference Miranda, Connolly and Bonnichsen99 Nevertheless, a systematic review of nine studies investigating infective endocarditis following transcatheter pulmonary valve replacement with the Melody® valve found that vegetations were detected by transthoracic echocardiography and transesophageal echocardiography in only 34% of cases. Reference Abdelghani, Nassif and Blom92

Transesophageal echocardiography remains a critical tool in the diagnosis of infective endocarditis in the paediatric population, particularly in those with limited transthoracic echocardiography views due to suboptimal acoustic windows, congenital anomalies affecting the thoracic cage, or chest wall deformities. Reference Baltimore, Gewitz and Baddour34,Reference Yuan, Liu, Hu, Zeng, Zhou and Chen90 Even in the absence of such limitations of transthoracic echocardiography, when there is a high clinical suspicion for infective endocarditis yet transthoracic echocardiography is negative, transesophageal echocardiography should be pursued. Reference Xie, Liu, Yang, Xu and Zhu93

While two-dimensional echocardiography is the first-line imaging tool in cases of suspected infective endocarditis, clinicians may consider cardiac cross-sectional imaging to further aid in diagnosis when echocardiography is not definitive. Reference Abdelghani, Nassif and Blom92 As advanced cardiac imaging modalities such as cardiac CT, cardiac MRI, and positron emission tomography/CT become more readily available and studied in paediatric CHD populations, their use in the evaluation of suspected infective endocarditis has gained popularity. While transthoracic echocardiography and transesophageal echocardiography remain clear first-line imaging modalities in suspected paediatric infective endocarditis, cardiac CT and cardiac MRI are reasonable alternatives or adjuncts depending on the underlying CHD. A single-centre retrospective study of paediatric patients with CHD found that cardiac CT played a complimentary role to echocardiography in the evaluation of suspected infective endocarditis, with cardiac CT able to eliminate the false negative diagnosis rate in their study population and reclassify a significant proportion of cases as definite infective endocarditis. Reference Nagiub, Fares and Ganigara100 Further, while transesophageal echocardiography is considered superior for visualisation of vegetations and valvular-related lesions, cardiac CT may be more sensitive for detection of paravalvular-related lesions such as pseudoaneurysm. Reference Sifaoui, Oliver and Tacher83,Reference Salman, Huynh and More101 As with transthoracic echocardiography, cardiac CT may better visualise more anterior cardiac structures such as the right ventricular outflow tract when compared to transesophageal echocardiography, which is of particular relevance to patients with tetralogy of Fallot who comprise a large proportion of CHD patients with infective endocarditis. Reference Miranda, Connolly and Bonnichsen99,Reference Nagiub, Fares and Ganigara100

The use of cardiac MRI in the workup and diagnosis of infective endocarditis has been overall less studied. One observational study found that cardiac MRI may be able to detect vegetations and antegrade and retrograde dissemination of infection, paravalvular tissue extension, and subendocardial and vascular endothelial involvement caused by shunt jets on delayed contrast-enhanced images. Reference Dursun, Yilmaz and Yilmaz102 Notably, findings by cardiac MRI were not corroborated by histopathology and metallic artefact from the presence of prosthetic valves may significantly limit diagnostic value of cardiac MRI in many CHD subsets. Nevertheless, in scenarios in which patients are unable to undergo transesophageal echocardiography testing, this panel finds cardiac CT and cardiac MRI to be appropriate alternative diagnostic imaging tools.

As previously outlined, findings by positron emission tomography/CT are now included in the updated Imaging Major Criteria of the 2023 Duke-International Society for Cardiovascular Infectious Diseases Infective Endocarditis Criteria. Reference Fowler, Durack and Selton-Suty4 While cardiac fludeoxyglucose uptake alone is not specific for the diagnosis of infective endocarditis, as it can be seen with other disease processes with increased glucose metabolism such as cardiac tumours, the combination of fludeoxyglucose positron emission tomography and cardiac CT is emerging as a modality which can provide anatomic localisation of infective endocarditis, differentiate between thrombus and vegetation, and evaluate for septic emboli. Reference Meyer, Fischer and Koerfer94 Use of this modality is also attractive as there may be otherwise limited visualisation of stented valves or isolated stents by transthoracic echocardiography or transesophageal echocardiography alone. One retrospective study found that positron emission tomography/CT was highly sensitive in localising valvular infective endocarditis across a range of CHD lesions, with a high impact on subsequent antimicrobial management. Reference Meyer, Fischer and Koerfer94 Further, a French retrospective multicenter study found that positron emission tomography/CT has a 92% positive predictive valve in the evaluation of suspected prosthetic valve or conduit infective endocarditis, as well as strong ability to detect embolic complications which were otherwise clinically silent. Reference Venet, Jalal and Ly95 Nevertheless, these potential added benefits must be weighed against radiation exposure, poor negative predictive value, and required preparatory fasting which may not be feasible for certain patient populations. Reference Venet, Jalal and Ly95

Intracardiac echocardiography also has emerging evidence for its role in the diagnostic evaluation of infective endocarditis. This modality has previously been described as a safe and effective method of visualising transcatheter pulmonary valve replacements with the Melody® valve. Reference Whiteside, Pasquali, Yu, Bocks, Zampi and Armstrong103 One small single-centre retrospective study found that intracardiac echocardiography was useful in confirming a diagnosis of infective endocarditis via visualisation of vegetations when transthoracic echocardiography or transesophageal echocardiography were otherwise inconclusive. Reference Cheung, Vejlstrup and Ihlemann96 It is important to weigh this potential added value with limitations of the modality, including being invasive and higher cost. Reference Cheung, Vejlstrup and Ihlemann96

Inpatient considerations and treatment

Abbreviations: IE, infective endocarditis; CHD, congenital heart disease.

The decision of medical alone versus combined medical and surgical management in paediatric cases of infective endocarditis is often challenging. The ideal timing of when to proceed with surgery is not clearly defined and is impacted by many factors including lesion site, causative pathogen, associated complications, and underlying co-morbidities. Reference Pettersson, Coselli and Writing107 While challenging, these decisions regarding surgical timing impact mortality and are critical in the inpatient management of infective endocarditis. Reference Khoo, Buratto and Fricke104 One single-centre retrospective review of paediatric patients and predominantly CHD patients with infective endocarditis who underwent surgery found that an increased delay for pre-operative antimicrobial treatment correlated with increased mortality. Reference Khoo, Buratto and Fricke104 Recommendations regarding indications for and timing of surgery will be further discussed in subsequent sections, however this panel recommends that a multidisciplinary team with representation from cardiology, cardiothoracic surgery, and infectious disease specialists collaborate when making decisions about medical versus surgical management of paediatric patients with CHD and infective endocarditis. Reference Khoo, Buratto and Fricke104–Reference Pettersson, Coselli and Writing107

In addition to deciding the method of treatment, clinicians caring for patients with infective endocarditis and underlying CHD must recognise risk factors for clinical decompensation and counsel patients and families accordingly. One retrospective review utilising a large paediatric health system database in the United States found that paediatric patients hospitalised for infective endocarditis with underlying CHD had a higher prevalence of cardiac arrest, mechanical ventilation, vasoactive medication use, and need for cardiac surgery as compared to those without underlying CHD. Reference Ware, Tani, Weng, Wilkes and Menon1 While acknowledging the limitations to quality of evidence in studying outcomes via a large administrative database, based on the potential heightened risk for critical care and morbidity, this panel recommends that institutions develop risk stratification tools and/or early warning systems for this patient population to detect early signs of clinical decompensation. Unsurprisingly, the need for mechanical ventilation, antiarrhythmic use, and vasoactive medication use in those with underlying CHD has also been associated with poor outcomes including the need for mechanical cardiac support, stroke, and death. Reference Ware, Tani, Weng, Wilkes and Menon1 With these identified risk factors in mind, caregivers and families of paediatric patients with underlying CHD receiving treatment for infective endocarditis should be educated and counselled accordingly.

Another important inpatient consideration for those caring for paediatric patients with infective endocarditis and underlying CHD includes antimicrobial selection. Choosing appropriate antimicrobial regimens for patients with infective endocarditis is critical in the successful eradication of infection, regardless of whether surgery is ultimately required. Bacterial resistance patterns are variable based on location, and clinicians should evaluate local antibiograms when selecting empiric antimicrobial therapy for treatment of infective endocarditis. Reference Eleyan, Khan and Musollari19,Reference Esposito, Mayer and Krzysztofiak20,Reference Johnson, Boyce, Cetta, Steckelberg and Johnson23,Reference Kelchtermans, Grossar and Eyskens25,Reference Willoughby, Basera and Perkins30

Further, due to traditional infective endocarditis antimicrobial management consisting of prolonged courses of intravenous antibiotics, there are increasing strategies aimed at improving patient quality of life and cost containment in adult populations. For example, it is commonplace for adults to be discharged with peripherally inserted central catheters to complete antibiotic courses as outpatients. However, peripherally inserted central catheters can be associated with specific complications in the setting of CHD and in those with smaller vessels. While many centres routinely discharge paediatric patients to complete extended courses of intravenous antibiotics at home, it is important to recognise that these patients require significant outpatient support, which may not exist or may be prohibitively difficult to access for children in many parts of the United States. Additionally, emerging evidence shows that dalbavancin, a long-acting antibiotic derived from a vancomycin analogue, is well tolerated, effective in adult infective endocarditis treatment, and associated with shorter hospital length of stay and reduced cost in infective endocarditis management. Reference Fazili, Bansal, Garner, Gomez and Stornelli108–Reference Wunsch, Krause and Valentin110 For some paediatric patients, particularly older adolescents, dalbavancin may be a helpful consideration but there is inadequate data to support formal recommendations from this panel.

Finally, there is increasing support within adult literature that enteral antibiotics may be appropriate for some eligible patients for the treatment of infective endocarditis. Reference Wald-Dickler, Holtom and Phillips111 While this form of therapy is an understandably attractive option as it avoids placement of a peripherally inserted central catheter and its associated complications, the panel did not find sufficient data on this topic specifically with regards to children or adolescents with underlying CHD to include as formal recommendations at this time.

Adverse events, complications, and mortality risk

Abbreviations: IE, infective endocarditis; CHD, congenital heart disease; TOF, Tetralogy of Fallot; NYHA, New York Heart Association.

Infective endocarditis in children and adolescents with underlying CHD is relatively rare; however, it carries a mortality rate as high as 5–15%. Reference Day, Gauvreau, Shulman and Newburger18,Reference Baltimore, Gewitz and Baddour34,Reference Thom, Hanslik and Russell114 It is therefore critical for clinicians to be aware of features that increase risk for complications and mortality related to infective endocarditis.

Neurologic complications related to infective endocarditis are important to consider, given the risk for significant morbidity as well as implications for timing of cardiac surgery, if warranted. Stroke is uncommon in the general paediatric population; however, it is an important complication to consider in patients with infective endocarditis due to the potential for septic emboli, particularly in those with left-sided infective endocarditis and a visible vegetation on the mitral or aortic valve. Reference Cao and Bi112 Further, a single-centre retrospective review of paediatric infective endocarditis cases found that embolisation occurs most commonly to the brain in the cases of native valve and left-sided lesions, and that evidence of embolic phenomenon is a commonly cited indication for surgery. Reference Carrillo, Duenas, Blaney, Eisner, Nandi and McConnell105 Specific guidelines for perioperative neurologic evaluation and neuroimaging are better defined in adults with infective endocarditis, with clear recommendations regarding timing of cardiac surgery depending on type of identified neurologic lesion (haemorrhagic vs ischaemic) and presence of neurologic deficits. Reference Pettersson, Coselli and Writing107 While not specific to the CHD population and thus not included in our recommendations, evidence supports pre-operative neuroimaging and evaluation by a paediatric neurologist in children with infective endocarditis and neurologic complications. Reference Carrillo, Duenas, Blaney, Eisner, Nandi and McConnell105,Reference Pettersson, Coselli and Writing107

The risk of complications is also affected by the causative pathogen. One retrospective multi-centre South Korean study found that S. aureus infective endocarditis was associated with more complications compared to infective endocarditis caused by viridans group streptococci. Reference Song, Bang and Han15 Notably, complications were described broadly, with cardiac complications loosely defined as the development of heart failure or abscess formation, and other complications defined as septic emboli, central nervous system complications, hepatic congestion, septic shock, septic arthritis, chylothorax, and mediastinitis. Reference Song, Bang and Han15

While outside of the scope of this clinical practice guideline, for adults underlying CHD and infective endocarditis, acquired co-morbidities such as diabetes, hypertension, coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, and renal insufficiency are the main predictors for adverse outcomes and prolonged intensive care unit stays. Reference Maser, Freisinger and Bronstein60,Reference Huang, Wen, Lu, Yang and Li116 For these adult patients, poor outcomes include myocardial infarction, stroke, pulmonary embolus, sepsis, dialysis, respiratory failure, and death. Reference Maser, Freisinger and Bronstein60,Reference Huang, Wen, Lu, Yang and Li116 While most paediatric patients have not developed these acquired illnesses at present, obesity and obesity-related illnesses are increasing in the paediatric population and it is possible paediatric providers may see similar impact of acquired illness on infective endocarditis morbidity and mortality in paediatric CHD patients. Reference Hampl, Hassink and Skinner117 Quality of evidence is very low, but one Turkish series of largely adult patients found that patients with NYHA class II or greater heart failure, elevated serum creatinine, and C-reactive protein on hospital admission to be higher risk of in-hospital mortality regardless of whether they were treated medically versus medically and surgically. Reference Elbey, Kalkan and Akdag115 Additionally, although it is outside of the scope of this clinical practice guideline to provide a related recommendation, elderly adults with CHD palliated with shunts or conduits who develop infective endocarditis are at high risk of infective endocarditis-related death. Reference Thornhill, Jones and Prendergast40

All patients with infective endocarditis and underlying CHD should be considered at high risk of mortality, and certain forms of CHD may confer additional risk. Reference Day, Gauvreau, Shulman and Newburger18,Reference Jortveit, Klcovansky, Eskedal, Birkeland, Dohlen and Holmstrom24,Reference Sun, Lai and Wang43 Specifically, individuals with tetralogy of Fallot and pulmonary atresia are considered to carry the highest risk of mortality related to infective endocarditis due to the potential for previously discussed disease-mediated features such as the need for right ventricular to pulmonary artery conduit, pulmonary valve replacement, cyanosis, and association with 22q11 deletion syndrome. Reference Day, Gauvreau, Shulman and Newburger18,Reference Verzelloni Sef, Jaggar, Trkulja, Alonso-Gonzalez, Sef and Turina118

Additional features which clinicians should consider to be risk factors for increased mortality in patients with infective endocarditis and underlying CHD include the presence of large vegetations (>15 mm) regardless of infection site, age less than one year, presence of heart failure, and S. aureus as a causative agent. Reference Cahill, Jewell and Denne2,Reference Song, Bang and Han15,Reference Gupta, Sakhuja, McGrath and Asmar22,Reference Yoshinaga, Niwa and Niwa113,Reference Thom, Hanslik and Russell114,Reference Schuler, Crisinel and Joye119,Reference Huang, Lu, Wen, Yang, Li and Lu120 Large vegetations may be associated with more significant valvular destruction, greater embolic risk, and less vulnerability to antibiotic penetration. Reference Yoshinaga, Niwa and Niwa113,Reference Thom, Hanslik and Russell114 Age less than one year has been described as a risk factor for the development of infective endocarditis in those with underlying CHD, yet their increased mortality with infective endocarditis has not been well explained. Reference Song, Bang and Han15,Reference Yoshinaga, Niwa and Niwa113 Moderate–severe congestive heart failure is known to be a risk factor for increased mortality in adult patients with infective endocarditis. Reference Thuny, Di Salvo and Belliard121 Contemporary paediatric studies also endorse heart failure in the setting of infective endocarditis in paediatric patients with CHD as a mortality risk factor. Reference Yoshinaga, Niwa and Niwa113,Reference Thom, Hanslik and Russell114 Causes of acute heart failure include perforation of valve leaflets, acute increases in valvular regurgitation, and development of ventricular dysfunction. There is opportunity for future research to better delineate this association however as existing studies of heart failure and mortality in this setting have loosely defined heart failure as either a condition requiring heart failure therapy or simply a designation confirmed by cardiologist. Reference Yoshinaga, Niwa and Niwa113,Reference Thom, Hanslik and Russell114 Lastly, given the increased rates of complications with infective endocarditis due to S. aureus, it is not surprising that S. aureus as a causative pathogen is also associated with increased mortality. Reference Cahill, Jewell and Denne2,Reference Song, Bang and Han15,Reference Gupta, Sakhuja, McGrath and Asmar22,Reference Yoshinaga, Niwa and Niwa113,Reference Schuler, Crisinel and Joye119

Some data suggest that surgical intervention during hospitalisation for infective endocarditis may impact mortality. Reference Verzelloni Sef, Jaggar, Trkulja, Alonso-Gonzalez, Sef and Turina118 A database review of paediatric and adult cases of infective endocarditis in the setting of underlying CHD found that surgical intervention was a predictive factor for lower rates of in-hospital mortality, favouring an earlier decision towards surgical intervention. Reference Yoshinaga, Niwa and Niwa113 Notably, there is emerging data within adult CHD populations suggesting equivalent mortality rates between medical and surgical management of infective endocarditis. Reference Byrne, Lopez, Broda and Dolgner122

Surgical considerations

Abbreviations: IE, infective endocarditis; CHD, congenital heart disease; TPVR, transcatheter pulmonary valve replacement.

Decisions regarding whether to pursue medical therapy alone versus surgical therapy for infective endocarditis are often challenging. In the most recent update to the American Heart Association Scientific Statement on Infective Endocarditis in Childhood, it is recommended that “the degree of illness not be considered a limitation to surgical intervention, because the alternative, to delay or defer surgery, can have dire consequences.” Reference Baltimore, Gewitz and Baddour34 This statement underscores the importance of weighing the decision to proceed with surgery carefully and recognising that early surgical intervention is sometimes warranted, even in the active phase of infective endocarditis. The active phase of infective endocarditis is generally considered to be while a patient has evidence of ongoing infection such as continued fever, persistent elevation of inflammatory markers, positive blood cultures, or prior to completion of a therapeutic course of antimicrobials. Reference Pettersson, Coselli and Writing107,Reference Hanai, Hashimoto and Mashiko127 Early surgery should be considered when valve repair, as opposed to replacement, is an option. Reference Shamszad, Khan, Rossano and Fraser123–Reference Xiao, Yin, Lin, Zhang, Wu and Wang125

Several retrospective reviews have also endorsed early surgery as necessary in patients with certain complications including perivalvular abscess, those who required a change in antimicrobial regimen, and infective endocarditis caused by notoriously destructive or resistant micro-organisms such as S. aureus or fungi. Reference Shamszad, Khan, Rossano and Fraser123,Reference Murakami, Niwa, Yoshinaga and Nakazawa126 These associations are not surprising given the inability of antimicrobials to penetrate and eradicate abscesses. The need to change antimicrobial therapy suggests a resistant organism not treated with traditional empiric regimens. Further, S. aureus is invasive and can create impenetrable biofilms, making treatment difficult. Although intended for the adult population, the executive summary of the 2016 American Association for Thoracic Surgery consensus guidelines on surgical treatment of infective endocarditis corroborates associations identified in retrospective paediatric studies and strongly supports early surgical intervention in the presence of perivalvular abscesses and heart failure symptoms. Reference Pettersson, Coselli and Writing107 Once symptoms of heart failure related to infective endocarditis have developed, the degree of valvular destruction and regurgitation is often too severe to address with medical therapy alone. Reference Pettersson, Coselli and Writing107

Additional features which may suggest need for early surgical therapy include recurrent embolism or recanalization of septal defects. Reference Wu, Buratto and Schulz124,Reference Hanai, Hashimoto and Mashiko127,Reference Chistyakov, Medvedev, Sobolev and Khubulava128 One large retrospective review of paediatric patients who underwent mitral valve repair in the setting of infective endocarditis found that larger vegetation size was associated with an increased risk of embolic events, both pre- and post-operatively. Reference Wu, Buratto and Schulz124 Therefore, clinicians may consider recurrent embolism in their decision-making about timing of early surgery to prevent serious neurologic sequelae. Further, one primarily adult-focused retrospective review in Russia described a median time from diagnosis of infective endocarditis to surgery of three days with favourable outcomes, even in the setting of recanalization of a septal defect with active infective endocarditis. Reference Chistyakov, Medvedev, Sobolev and Khubulava128

Once the decision to proceed with surgery is made, it is important to consider the type of surgical repair required. In children undergoing surgery for native valve infective endocarditis (with or without underlying CHD), it is reasonable to consider primary valve repair. Reference Hickey, Jung and Manlhiot129,Reference Zhu, Buratto and Wu133,Reference Wu, Zhu, Buratto, Brizard and Konstantinov134 For children with infective endocarditis involving the aortic valve, aortic root replacement with a pulmonary autograft (Ross procedure) has been shown to be a reasonable option in centres with appropriate experience when the aortic valve is not amenable to repair. Reference Ringle, Richardson and Juthier130,Reference Russell, Johnson, Wurlitzer and Backer131,Reference Wu, Zhu, Buratto, Brizard and Konstantinov134

Emerging evidence from certain CHD populations suggests that there are specific criteria clinicians can consider regarding medical therapy alone versus surgery. A large multicentre cohort study evaluating all patients who underwent transcatheter pulmonary valve replacement found that while those presenting with sepsis or severe right ventricular dysfunction had higher mortality, approximately half of patients with infective endocarditis were successfully managed with medical therapy alone without subsequent surgical valve replacement. Reference McElhinney, Zhang and Aboulhosn77 Further, a systematic review of studies investigating infective endocarditis following transcatheter pulmonary valve replacement with the Melody® valve found that antimicrobial therapy alone was sufficient in approximately one third of patients, largely those without right ventricular outflow tract obstruction. Reference Abdelghani, Nassif and Blom92 Therefore, it is reasonable to favour medical therapy in those without significant right ventricular outflow tract obstruction and stable hemodynamics. Importantly though, in the case of infective endocarditis following transcatheter pulmonary valve replacement, infective endocarditis caused by S. aureus has been shown to require high rates of explantation with associated high rates of mortality as opposed to non-staphylococcal cases. Reference Davtyan, Guyon and El-Sabrout132 Therefore, early surgical explant of transcatheter pulmonary valve replacement in the setting of S. aureus infective endocarditis should be considered. Reference Davtyan, Guyon and El-Sabrout132

Counselling for patients, families, and other health professionals

Abbreviations: IE, infective endocarditis; CHD, congenital heart disease; RHD, rheumatic heart disease; BJV, bovine jugular vein; PVR, pulmonary valve replacement; TPVR, transcatheter pulmonary valve replacement.

Maintaining good dental hygiene is critical to infective endocarditis prevention, and patients with poor dental hygiene should be considered at higher risk for the development of infective endocarditis. Reference Mendel and Siagian63 The pathophysiology of dental plaque biofilm formation and propagation in the setting of poor oral hygiene has been previously well described. Reference Baltimore, Gewitz and Baddour34 Dental procedures can cause transient bacteraemia with pathogenic microbes and ultimately lead to infective endocarditis. Reference Baltimore, Gewitz and Baddour34 Recommendations regarding antimicrobial prophylaxis prior to dental procedures is beyond the scope of this clinical practice guideline and are well-established; however, shared acknowledgment of risk factors among inpatient clinicians caring for patients with CHD and their primary dental providers is critical in infective endocarditis prevention. Reference Wilson, Taubert and Gewitz55 Dentists and paediatricians in the community should be aware that poor dental health increases risk of infective endocarditis in children with CHD and rheumatic heart disease. Reference Moges, Gedlu and Isaakidis135,Reference Tasdemir, Erbas Unverdi and Ballikaya139–Reference Karikoski, Sarkola and Blomqvist141 This speaks to the importance of understanding a patient’s prior medical history and assessing their ongoing risk for infective endocarditis with dental procedures.

Given the increased risk of infective endocarditis in all individuals with CHD, it is imperative for clinicians to appropriately counsel their patients on infective endocarditis prevention, clinical presentation, and when to seek medical attention. Certain high-risk groups within the CHD population, specifically those who have undergone placement of valve-containing prostheses or who have undergone procedures with bovine jugular vein material, warrant a heightened degree of awareness and level of counselling by clinicians. Reference Kuijpers, Koolbergen and Groenink3,Reference Verheugt, Uiterwaal and van der Velde41,Reference Albanesi, Sekarski, Lambrou, Von Segesser and Berdajs136–Reference Malekzadeh-Milani, Houeijeh and Jalal138,Reference Wijesekera142 Infective endocarditis may occur shortly after pulmonary valve replacement or any time thereafter Reference Kuijpers, Koolbergen and Groenink3 As such, education for patients and families within this group should be provided and reinforced regularly. Further, we recommend that prior to transcatheter pulmonary valve replacement of any kind, patients should be thoroughly evaluated for dental clearance and followed closely to ensure maintenance of good dental hygiene. Reference Malekzadeh-Milani, Ladouceur and Patel81

Limitations

Panellist recruitment occurred via the Paediatric Acute Care Cardiology Collaborative and only centres with Paediatric Acute Care Cardiology Collaborative affiliation were represented. However, the Paediatric Acute Care Cardiology Collaborative has never previously undertaken research or quality improvement work on infective endocarditis, so it is unlikely that this affiliation influenced recommendations. To ensure broad representation of clinical stakeholders in the management of infective endocarditis, panellists were invited to participate based on their professional backgrounds, academic interests, and clinical expertise, though they were not required to have recently published articles or completed research related to infective endocarditis.

Another important limitation of this work is the quality of evidence pertaining to infective endocarditis. Specifically, the panel identified numerous gaps in the available evidence and found that the quality of existing evidence was overall low. Only five of the 50 recommendations have a high quality of evidence, and many have a low or very low quality of evidence.

Conclusions