8.1 Introduction

Compared to their counterparts in countries such as Denmark, Ireland, and Germany, Italian implementation authorities generally display higher levels of organizational policy triage. Within their daily responsibilities, Italian authorities accountable for the implementation of environmental and social policies often find themselves making significant trade-offs in the allocation of their limited resources toward policy execution. Policy triage in Italy manifests in various forms, which include decisions on handling certain implementation tasks superficially, neglecting them, or delaying them in favor of other duties. This pattern remains consistent across all organizations involved in the implementation of social and environmental policies, with some minor variations.

The main driver of policy triage is the strong growth of sectoral policy stocks that is combined with a very high level of organizational overload vulnerability. The latter primarily results from the fact that Italian policymakers face few limitations to shift the blame for implementation failures to the responsible administrative agencies: Political and administrative costs of unloading additional burdens on implementation bodies are extremely low, while political instability provides strong incentives for policy overproduction (Gratton et al., Reference Gratton, Guiso, Michelacci and Morelli2021).

Given this constellation, it is remarkable that the observed levels of policy triage and the resulting implementation shortcomings are not significantly higher. Despite policy prioritization being a frequent and sometimes highly consequential occurrence, it appears that Italian implementation bodies are still capable, albeit inadequately, of ensuring the execution of tasks they deem essential (Adema et al., Reference Adema, Fron and Ladaique2011; Lynch & Ceretti, Reference Lynch, Ceretti, Mammone, Parini and Veltri2015; Wolf et al., Reference Wolf, Emerson, Esty, de Sherbinin and Wendling2022). How can this be explained?

The answer to this question lies in pronounced and widespread organizational commitment to overload compensation – largely a result of strong organizational policy advocacy in both sectors. The internal commitment to managing overload goes a long way in alleviating some of the adverse impacts on policy performance. However, even with these compensatory efforts in place, both policy sectors still indicate that implementation bodies carry out their tasks under challenging circumstances, with compensation, at best, mitigating the most severe consequences of overburdening.

This overarching observation remains consistent even though policy implementation in Italy spans across multiple organizations, both at the national and subnational levels, often with overlapping responsibilities. Nevertheless, variations do exist within this general pattern, primarily in terms of the frequency and severity of policy triage. Specifically, a distinction can be made between national authorities, which are less susceptible to overload due to their greater capacity to mobilize additional resources, and local implementation bodies operating at the regional, provincial, and municipal levels. While implementation bodies at all levels are actively involved in compensating for overload, these differences in susceptibility to overload lead to slight variations in policy triage.

In the following sections, we will commence with an overview of the fundamental structural features that define the landscape of Italian policy implementation within the two sectors under examination (Section 8.2). Moving forward to Section 8.3, we will explore how the abundance of opportunities for shifting political blame and the limited options for expanding resources contribute to a heightened vulnerability to overload among Italian implementation bodies. Section 8.4 delves into the intricate patterns of organizational policy triage. Transitioning to Section 8.5, we will elucidate how the organizational commitment to managing overload plays a pivotal role in averting the most adverse consequences, thereby ensuring a modest level of functionality in the implementation arrangements. Finally, in Section 8.6, we will draw overarching conclusions and contextualize our findings within the framework of our theoretical argument.

8.2 Structural Overview: Environmental and Social Policy Implementation in Italy

The implementation of public policies in Italy is characterized by several peculiarities that determine the broader context in which implementation bodies operate. First, Italy displays a remarkable discrepancy between its economic and its state capacity. While the country belongs to the most developed economies in the world, it has traditionally been considered a laggard in the development of state and administrative capacity (Hanson & Sigman, Reference Hanson and Sigman2021). Its citizens perceive the quality of public services as rather low, and the Government Effectiveness indicator places Italy at the bottom of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) group of countries (Bulman, Reference Bulman2021).

Second, and related to this aspect, Italian public administration is generally characterized by strong political interference. Although Italian public administration strongly adheres to formalism and legalism in line with the Napoleonic administrative tradition (Ongaro, Reference Ongaro, Painter and Peters2010), these features hardly help to counteract political interference (Cepiku, Reference Cepiku2018). Instead, political patronage paired with a strong domination of politics over the public administration, is prevalent in the Italian state, stalling the development of a functional public administration (Castellani, Reference Castellani2019).

Third, in addition to political interference, policy implementation takes place in the context of highly complex administrative structures, with partially overlapping and unclear competence allocation between authorities at the national and subnational level (including the local communities of the regions, provinces, and municipalities). Constitutionally, Italy is a so-called regional republic, divided into twenty regions with varying degrees of autonomy (Palermo et al., Reference Palermo, Parolari, Valdesalici and Merloni2016). This setup is a result of the administrative and territorial reforms during the 1990s and 2000s that have transformed a unitary state into a hybrid type of multilevel governance and a “quasi-federalist” policy landscape (Lippi, Reference Lippi2011). Despite a formal recognition of institutional pluralism, the Italian system of governance had previously been characterized by a strong centralization of competences and powers (Buoso, Reference Buoso, Sommermann, Krzywoń and Fraenkel-Haeberle2025). Only toward the end of the 1990s did a more marked development of decentralization take off, with the regions being conferred wider and more substantive administrative and regulatory powers alongside the provinces and municipalities (Orlando, Reference Orlando, Alberton and Palermo2012). Yet, this process of progressive enhancement of local authorities implies that in many policy areas, policy implementation is fragmented, inconsistent, and characterized by blurred lines of responsibility, overlap, and duplication of tasks across and within governance levels (Marchetti, Reference Marchetti2010). Powers and competences are ambiguously defined, and they are de facto determined through negotiations between political leaders (Knill et al., Reference Knill, Steinbacher and Steinebach2021b).

The ambiguity of competence allocation has been well recognized as a problem, and a variety of mechanisms have been developed to ensure administrative coordination horizontally (through the conferenza dei servici) and vertically (via the conferenza unificata stato-regioni). Yet, despite these mechanisms of coordination, conflicts continue to arise, in particular between the state and the regions (Orlando, Reference Orlando, Alberton and Palermo2012). Overall, both environmental and social policy developments lack clarification in terms of tools, roles, timeframes, and means for policy formulation, monitoring, and evaluation (Bulman, Reference Bulman2021).

Fourth, the allocation of administrative resources follows a highly centralized pattern, which strongly reduces the opportunities for sectoral bodies (even ministries at the central level) to mobilize additional resources. More specifically, it is the State General Accounting Department within the Ministry of Economy and Finance that is responsible for the economic and financial planning for the public sector. Subsequently, in both the environmental and the social sectors, the decisions regarding the spending of the resources and the recruitment procedures are adopted by each organization or body on the basis of a preapproved three-year needs plan.

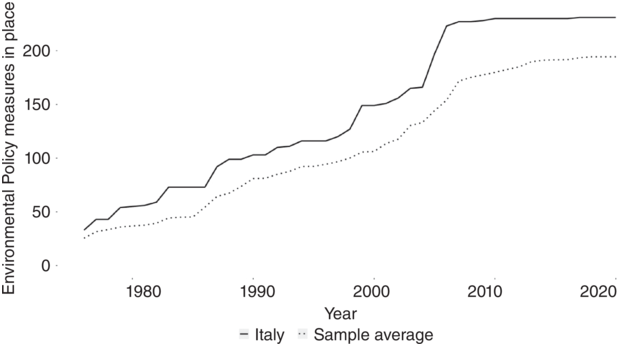

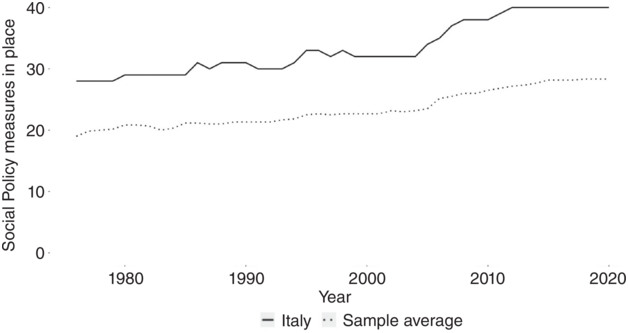

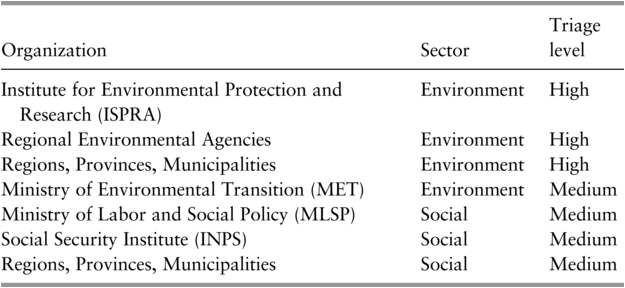

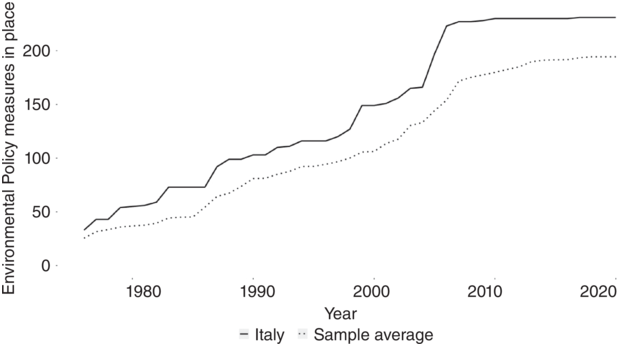

With regard to the two policy areas under study, this broader context in which implementation bodies are operating coincides with strongly pronounced patterns of policy growth that clearly exceed rates of policy accumulation in the other countries under study (Adam et al., Reference Adam, Hurka, Knill and Steinebach2019). For both policy sectors, growth rates surpass the average of our country sample. The gap in the size of the policy portfolios between Italy and the sample average – with a particular increase in the number of policy measures in place – occurred in 2004 (see Figures 8.1 and 8.2).

Figure 8.1 Environmental policy measures in Italy.

Figure 8.2 Social policy measures in Italy.

In the following, we take a closer look at the peculiarities of the implementation arrangements in the two sectors under study and show how the growing implementation burdens associated with policy growth are distributed among the different agencies and authorities.

8.2.1 Competence and Burden Allocation in Environmental Policy

The implementation of environmental policy in Italy is characterized by a complex setup in which administrative bodies at different levels are involved, with partially unclear and disputed competence allocations. Article 117(2) of the Italian constitution reserves the “protection of the environment, the ecosystem, and cultural heritage” to the exclusive legislative competence of the state. The regions, conversely, maintain concurrent regulatory powers in a number of areas related to or overlapping with the environment, such as waste management or environmental impact assessments (Dell’Anno et al., Reference Dell’Anno, Pergolizzi, Pittiglio and Reganati2020).

While regulatory powers are reserved for the state and the regions, constitutional arrangements provide limited guidance on the specific allocation of implementation tasks across the different governance levels (Orlando, Reference Orlando, Alberton and Palermo2012). In practice, responsibilities in the concrete implementation of environmental policies follow a paradigm largely based on the territorial relevance of the interests at stake (Dell’Anno et al., Reference Dell’Anno, Pergolizzi, Pittiglio and Reganati2020). Accordingly, the state level retains primary responsibilities in implementing environmental issues of national relevance and in defining the fundamental principles and guidelines that shall inform public action concerning national territory and the management of natural resources.

In line with this general division of implementation competences, state-level authorities are primarily responsible for setting environmental policy and standards through legislation and regulation, and for overseeing the implementation of these policies at the regional, provincial, and municipal levels (Marchetti, Reference Marchetti2010; Panzeri, Reference Panzeri2018). The principal national authority is the Ministry of Ecological Transition (Ministero della Transizione Ecologica; MET). The main implementation tasks of MET are to monitor the implementation of state legislation by subnational authorities and to ensure the uniform application and interpretation of regulatory requirements. Moreover, MET is in charge of authorizing integrated permits for large-scale industrial plants (integrated prevention and pollution control). The National Institute for Environmental Protection and Research (Instituto Superiore per la Protezione e la Ricerca Ambientale; ISPRA) is in charge of monitoring and enforcing environmental regulations and provides scientific advice to support environmental policy and decision-making. ISPRA coordinates the work of regional-level environmental agencies responsible for collecting the data and monitoring the implementation of the environmental policies. A network of ISPRA’s laboratories covers the overall territory of the regions and is in charge of monitoring the quality of air and water at the local level.

The subnational authorities, by contrast, carry out the bulk of practical implementation tasks. In this regard, the main competences are located at the level of the regions. The latter, however, have delegated many tasks to the provinces and municipalities. In carrying out their work, regional governments are supported by regional environmental protection agencies (Agenzie Regionali per la Protezione dell’Ambiente; ARPA). These offices are responsible for implementing environmental policies and regulations at the regional level and work closely with regional governments. In addition to regional environmental agencies (that are supporting ISPRA), regional government authorities are responsible for developing and implementing regional environmental plans and play a key role in the management and protection of regional parks and other protected areas. Moreover, regional governments are responsible for implementing waste management policies and regulations, the implementation of air quality policies and regulations, including measures to reduce air pollution from industrial and transportation sources, as well as the management of water resources, including the development of policies and regulations related to water quality, water supply, and water conservation.

Provinces, positioned as intermediaries between the regions and municipalities, assume a multifaceted role encompassing various technical and operational responsibilities. These functions align with the geographical dimensions of the interests involved, often including functions of authorization, monitoring, and control. In contrast, municipalities, considered the territorial entities most representative of the local and community interests, are entrusted with operative functions related to the development and use of the territory for the benefit of the local community and the provision of public environmental services, such as waste and sewage disposal, and collection of data concerning noise and atmospheric pollution and soil decontamination (Orlando, Reference Orlando, Alberton and Palermo2012).

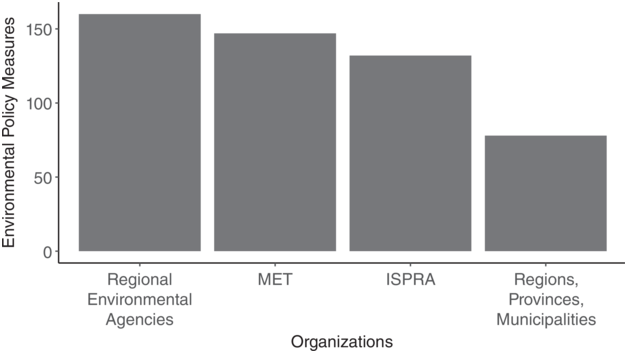

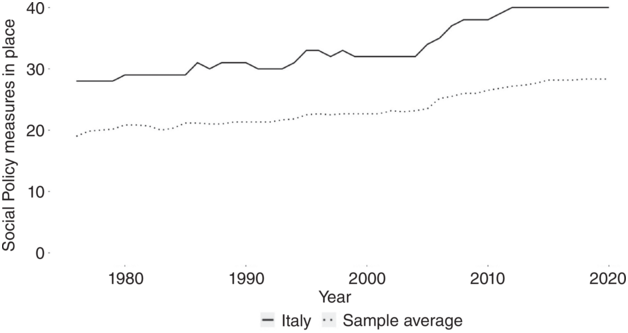

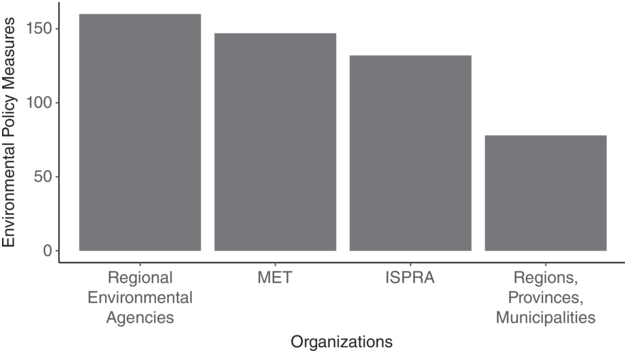

Figure 8.3 illustrates how environmental implementation tasks are distributed across different agencies. It is clearly visible that the national-level organizations (MET and ISPRA), as well as subnational government bodies, have been affected by the increasing workload emerging from accumulating policies up for implementation (Knill et al., Reference Knill, Steinbacher and Steinebach2021b; Lynch & Ceretti, Reference Lynch, Ceretti, Mammone, Parini and Veltri2015).

Figure 8.3 Distribution of implementation tasks in environmental policy.

8.2.2 Competence and Burden Allocation in Social Policy

Similar to the environmental sector, the implementation of social policy is also based on a distribution of tasks between state and subnational authorities. While pension, unemployment, and child benefits are regulated at the national level, decentralization reforms since the late 1990s have significantly dispersed social policy responsibilities (Graziano & Winkler, Reference Graziano and Winkler2012). With the constitutional reform ratified in 2001, regional levels of government were entrusted with primary responsibility in three social policy fields: health care, social assistance, and active labor market policies (Fargion, Reference Fargion, McEwen and Moreno2005). Although Italy (along with Spain) has been characterized as a “regionally framed welfare system” (Kazepov, Reference Kazepov2010: 60), social insurance, including pension schemes and unemployment benefits, is still controlled by central authorities. This holds even though certain regions have enacted regulations governing the establishment of territorial funds. In response, regional social partners have entered into contractual agreements to establish closed funds dedicated to specific groups of workers, with the backing of regional support (Ferrera, Reference Ferrera and Ferrera2005).

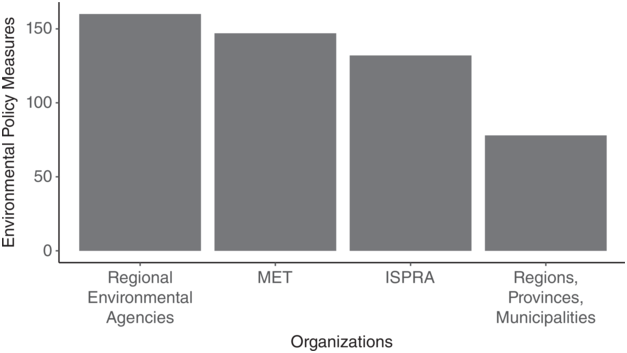

Figure 8.4 provides an overview of the organizations responsible for the implementation of Italy’s social policy portfolio. At the state level, the National Institute for Social Security (Istituto Nazionale della Previdenza Sociale; INPS) and the Ministry of Labour and Social Policies (Ministero del Lavoro e delle Politiche Sociali; MLPS) are the key implementation authorities. The ministry is responsible for developing and implementing policies related to employment, social security, and other social services (Del Pino & Pavolini, Reference Del Pino and Pavolini2015). INPS is an independent agency operating under the supervision of MLPS and manages the Italian social security system for the majority of self-employed workers and public and private sector employees. Its regional-, provincial-, and municipal-level offices represent contact points for the citizens entitled to pension, childcare, family, and unemployment benefits. INPS also manages the health insurance system for workers in the country and is a key player in the implementation of social policies in Italy.

Figure 8.4 Distribution of implementation tasks in social policy.

Regions have their own offices dedicated to planning, programming, implementing, and monitoring a variety of social policies that provide social protection mainly in the form of service-oriented programs for children, families, minors, and young people, as well as support for risk of poverty (Ferrera, Reference Ferrera and Ferrera2005; Kazepov, Reference Kazepov2010). Indeed, with the Constitutional Law 3/2001, the regions were given the sole responsibility for the selection of social assistance objectives, principles, and planning; and only the establishment of national minimum standards (“essential levels”) was left to the central government so as to guarantee homogeneity across the entire national territory (Catalano et al., Reference Catalano, Graziano and Bassoli2015). Although Italian regions have been given increasing spending and taxation powers from the 1980s onwards, in developing and implementing their policies, regional governments are strongly dependent on central funds, as became apparent in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, where regions were constrained to accept significant cuts and loss in control over their budgets (Del Pino & Pavolini, Reference Del Pino and Pavolini2015).

The provincial level is mainly responsible for managing labor-related services, particularly the implementation of active labor policies. The municipalities, by contrast, are the main providers of social assistance policies. According to the principle of subsidiarity, municipalities are primarily in charge of service and social benefits delivery, as well as with the design and implementation of the overall network of social services (Catalano et al., Reference Catalano, Graziano and Bassoli2015; Citroni et al., Reference Citroni, Lippi, Profeti, Wollmann, Koprić and Marcou2016).

Given our particular focus on unemployment, pensions, and child benefits policies, it is hardly surprising that the major increase in implementation burdens associated with our policies under investigation has affected the authorities at the central level (including their local branches), while subnational government levels have been involved to a lesser extent. Of course, this does not mean that the subnational level did not face substantial increases in implementation burdens (Catalano et al., Reference Catalano, Graziano and Bassoli2015). Yet, these increases are beyond the scope of the underlying study.

8.3 At the Mercy of Policy Triage: Exorbitant Overload Vulnerability of Italian Implementation Bodies

From the different countries under study, Italy can clearly be characterized as a case in which sectoral implementation organizations are extremely vulnerable to being overloaded with constantly growing policy tasks. This can be traced back to two factors: First, Italian policymakers face hardly any limitations in shifting the blame for implementation failures. Second, implementation bodies have limited opportunities to mobilize additional resources in order to enhance their implementation capacities.

8.3.1 A Free Lunch for Policymakers: Blame Attribution for Implementation Failure

As we have shown in Chapter 2, policy growth constitutes a phenomenon that can be observed across all advanced democracies. Yet, its essential drivers are particularly pronounced in the Italian political system. In fact, Italy is the country with the highest rates of policy growth in both sectors under investigation (Adam et al., Reference Adam, Hurka, Knill and Steinebach2019; Fernández-i-Marín et al., Reference Fernández-i-Marín, Hinterleitner, Knill and Steinebach2023b; Hinterleitner et al., Reference Hinterleitner, Knill and Steinebach2023). Why is this the case? We argue that Italian policymakers are in a very comfortable situation to deflect the blame for implementation problems. While they have strongly pronounced incentives to engage in excessive policy production, policymakers face very few political or administrative cost limitations for unloading the implementation burdens associated with policy growth.

Political Costs: Policy Production as Highly Rewarding, Yet Costless Activity

Politicians in democratic systems generally have strong electoral incentives to engage in policy production in order to demonstrate their responsiveness to societal demands, while the parallel engagement in the termination of existing policies is much less rewarding (Bauer et al., Reference Bauer, Jordan, Green-Pedersen and Héritier2012). As emphasized by Gratton et al. (Reference Gratton, Guiso, Michelacci and Morelli2021), these electoral incentives are particularly pronounced in the Italian case. The main reason for this pattern lies in the very short time horizons of Italian politicians that emerge from short legislative terms, as they unfolded in particular with rising political instability since the early 1990s. Italian national-level government coalitions are highly unstable – the current government headed by Prime Minister Georgia Meloni is the sixty-eighth government since World War II, averaging a new government every thirteen months. To maximize their chances for reelection, Italian politicians have strong incentives to engage in the production of policies, even if the latter are weakly designed. What counts from a politician’s perspective is to demonstrate responsiveness; even adopting useless measures by the end of the term signals competence.

By contrast, the risk of being blamed for ineffective policies is very low in view of short political time horizons. There is a high likelihood that implementation will take place in subsequent political terms, implying that the incompetence of policy proponents will not be revealed. This pattern also entails that politicians prefer the adoption of new policies over the adjustment of existing measures: “At the political level, they prefer to introduce something new instead of using what is already on the ground. This is a big problem,” as emphasized by an officer in the Social Ministry (ITA21). Or as one interviewee from the regional government office for the environment puts it:

There is the habit of regulating everything. It is with this defect we find ourselves in the presence of many regulations that are still valid but are from the early 1900s, and that are not adjusted to the new regulations on the environment, so we have a whole series of processes that overlap and do not bind with each other and therefore […] make us waste time.

From this follows that – regardless of formal responsibilities for legal or technical oversight – Italian policymakers have ample opportunities to shift the blame for ineffective policies to the implementation level. Due to the fragility of governing coalitions, it is highly likely that office periods are much shorter than implementation periods; that is, policymakers that are responsible for the adoption of ill-designed policies and bureaucratic overload can no longer be held accountable (Gratton et al., Reference Gratton, Guiso, Michelacci and Morelli2021). “[Politicians] make us pass the term, waste time, in the sense that there is so much smoke for the outside but there is little substance” (ITA11). Interviewees from implementation bodies in both sectors confirm this pattern:

At the political level, there is not enough attention on implementation. They are concerned with the design of the policies and with the definition of the law, as if writing down something into law was enough. They don’t have enough concern about the fact that implementation is time consuming and requires the right attention.

As soon as they arrived and because we frequently change from left to right, from right to up or down, and in the first year, because they won the election, they promise to cancel, to do this and that, more environment, no environment, environment is too strong or too weak, it depends. [They promise] to change what the previous political level has done. But normally, they arrive as newcomers, they know nothing, nothing of technical, nothing of administrative understanding, nothing of nothing.

The factual absence of political accountability for policy implementation is reinforced by complex and overlapping formal arrangements in the allocation of responsibility across government levels (Cepiku, Reference Cepiku2018; Knill et al., Reference Knill, Steinbacher and Steinebach2021b). In the environmental sector, this is particularly relevant regarding the competences of the national- and regional-level authorities. Unclear specifications have resulted in several, not yet fully resolved proceedings before the Constitutional Court (Orlando, Reference Orlando, Alberton and Palermo2012). With regard to the system of environmental agencies, accountability has increased since 2008 when ISPRA clarified obligations between the national level and the branches at the regional level (Palermo et al., Reference Palermo, Parolari, Valdesalici and Merloni2016). Regardless of these developments, no clear and generally accepted delineations of responsibilities for policy formulation and implementation between the national and regional levels have been established, making it hard to pinpoint who would actually be responsible for the policy implementation results. Unclear accountability arrangements further reduce the political costs for policymakers to unload implementation burdens: “There is no limit as to what politicians can ask us to do. This is very dangerous. This gives the impression to the political level that they can make commitments without taking care of what happens below” (ITA24).

Although for social policy there is a somewhat clearer allocation of political and administrative responsibilities between different levels of government (Catalano et al, Reference Catalano, Graziano and Bassoli2015), considerable blame-shifting leeway for policymakers exists. The latter primarily results from the discrepancies between centrally defined policies that require transposition and specification at the regional level (Ongaro & Valotti, Reference Ongaro and Valotti2008). In this regard, policymakers at the national level typically ignore the social realities and practical challenges of policy implementation. As one interviewee from the regional authority for social policy states:

In reality then our central level, when it does all the programming part through decrees, when it launches a public policy, an experiment, in reality the central government is very much accompanied by outsourcing, that is, the central level is very supported and helped not only by officials from ministries but also by officials of development agencies, consultancy agencies, trainers, that is, many people who make their thoughts available to national politics. So when a policy arrives here in the region, we get a broad policy, designed with a 360 degrees view, and therefore we cannot make things easy because central programming asks us to make them complicated, complex, articulated, complete, and therefore it is then up to us to try to recover the gap between what the state requires and what we can do.

Shifting the blame for policy failure on the organizations in charge of policy implementation is furthermore facilitated by the widespread – and often politically articulated – criticism of the Italian public administration as being responsible for policy delays and policy failure resulting from legalism, lacking transparency, and problems of corruption (OECD, 2013). While administrative reforms have largely failed because of political instability and the legalist administrative tradition (Cepiku & Meneguzzo, Reference Cepiku, Meneguzzo, Bouckaert and Jann2020), the weak reputation of public administration – which is further enhanced by excessive policy production and resulting overload – makes it easy to declare political failures as bureaucratic pathologies. As stated by an INPS official, “the reputation of INPS is deliberately a bit muddy because it is still comfortable as a scapegoat of other problems” (ITA37). As a result, the political level can distance itself even further away from the responsibility for the success of policy implementation.

Administrative Costs: The Comfortable Shadow of Austerity and Decoupled Resource Allocation

Italian policymakers not onlyface very low political costs associated with policy growth; they also do not have to carry the administrative costs that are caused by the implementation of the policies they are producing. Usually, these costs are shifted to those organizations that are in charge of policy implementation.

As a result of the efforts to downsize the public administration and to cut administrative spending in the aftermath of the Great Recession (Di Mascio & Natalini, Reference Di Mascio and Natalini2014), it has been increasingly difficult to ensure sufficient human resources for the implementation of new policies at all levels of government. For authorities at the national level, this is reinforced by the fact that decisions about recruitment of staff and spending of resources are decoupled from the sectoral ministries but fall under the responsibility of the State General Accounting Department within the Ministry of Economy and Finance (see Section 8.2). National authorities can allocate their resources only within the limits defined by the planning specified by the accounting department.

In addition, new policies often explicitly prohibit the allocation of new funding for their implementation, making it rather easy for the formulators to adopt new policies (ITA12). The hiring of the new personnel, as one employee from the Ministry of Labor and Social Policy (MLSP) puts it, “depends on juridical interventions that would allow to increase the number of staff for the Ministry. We cannot decide autonomously to increase the number of workers, if there isn’t a law that decides that our Ministry needs more workers” (ITA21). Similar complaints on the very limited, say, national-level implementation bodies have in the distribution of administrative resources are made by MET officials, stating that “public administration does not have the autonomy in this field, they cannot decide to take people on board to increase the staff without the political will, without political decision that gives money and resources” (ITA24).

While decisions about new policies and decisions about the allocations of resources are rather decoupled at the national level, in principle, a more integrated scenario applies to the formulation and implementation of policies at the level of the regions. Yet, the regions strongly depend on central government funding and have limited opportunities to generate their own financial resources via municipal property taxes. As a result, in particular poorer regions heavily depend on the central government to supplement funding policy (Citroni et al., Reference Citroni, Lippi, Profeti, Wollmann, Koprić and Marcou2016; Knill et al., Reference Knill, Steinbacher and Steinebach2021b). This dependence has led to considerable differences in the generosity of regional welfare policies relating to social assistance and active labor market policies (Catalano et al., Reference Catalano, Graziano and Bassoli2015).

The strong limitations for compensating implementation bodies with administrative resource expansions in exchange for their growing workload have only very recently been slightly improved. In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, a National Recovery and Resilience Plan has been adopted, introducing new opportunities for hiring additional personnel (Cotta & Domorenok, Reference Cotta and Domorenok2022). Organizations at the national level have already been benefiting from this development: “Thanks also to this plan, there is new staff being hired recently, including staff that is highly qualified and therefore able to withstand the excessive workloads” (ITA27).

Despite these recent improvements, however, Italian implementation bodies in the two sectors under study can be considered as extremely vulnerable to being overloaded by excessive policy growth. Policy producers hardly face any political or administrative costs associated with the adoption of new regulations and laws. As will be shown in the Section 8.3.2, implementers have very limited opportunities to counterbalance this trend by mobilizing for administrative resource expansion.

8.3.2 Weak Political Voice: The Limits of Organizational Resource Mobilization

Sectoral implementation bodies at the national and subnational level have very weak possibilities to mobilize for an expansion of their administrative capacities to handle their growing burden load. Implementation bodies have not only problems to articulate joint positions but also lack effective consultation channels.

Although representative organizations at the subnational level (for regions and municipalities) exist, interest articulation by subnational governments has been historically ineffective due to fragmentation, a lack of agreement and commitment, and very weak horizontal coordination (Baldini & Baldi, Reference Baldini and Baldi2014; Mussari & Giordano, Reference Mussari, Giordano, Cepiku, Jesuit and Roberge2013). These problems are reinforced by the fact that administrative expertise is underdeveloped (with education levels in the Italian public administration being comparatively low), and union representation being fragmented (Cepiku & Meneguzzo, Reference Cepiku, Meneguzzo, Bouckaert and Jann2020). Despite some attempts to unite the voices of subnational implementers, the shortcomings prevail. Particularly, very disparate street-level situations and issue perspectives block any streamlining of policy positions upfront (Bolgherini et al., Reference Bolgherini, Casula and Marotta2018). In both sectors under investigation, the articulation of common positions of implementation bodies suffers from organizational heterogeneity and fragmentation as well as conflicts of interest (Cavatorto & La Spina, Reference Cavatorto and La Spina2020), while collaborative institutions like the River Basin Authorities, are institutionally weak and do not initiate bottom-up feedback (Balzarolo et al., Reference Balzarolo, Lazzara, Colonna, Becciu, Rana, Junier, El Moujabber, Trisorio-Liuzzi, Tigrek, Serneguet, Choukr-Allah, Shatanawi and Rodríguez2011).

Articulation problems are reinforced by the absence of effective consultation procedures. Despite decentralization and quasi-federalization, the central government maintains its top-down management approach, preferably via bilateral central–local relations. It remains inattentive to implementation concerns, even when being confronted with massive resistance (Baldini & Baldi, Reference Baldini and Baldi2014; Marchetti, Reference Marchetti2010). Accordingly, the State-Regions, the State-Municipal, and the Unified Conference for all subnational governments are weak consultative channels, with little formal powers and depend on central command. Other formal and informal consultative arrangements are “very weak” and “limited in scope” (Bolgherini et al., Reference Bolgherini, Casula and Marotta2018; Palermo & Wilson, Reference Palermo and Wilson2014: 511, 521). Neither in environmental nor in social policy do existent platforms provide effective subject-specific feedback mechanisms for implementation organizations (Mussari & Giordano, Reference Mussari, Giordano, Cepiku, Jesuit and Roberge2013; Secco et al., Reference Secco, Favero, Masiero and Pettenella2017).

Interviewees suggest that the central-level policies are made without taking subnational context and resource limitations into account (ITA15): “It is the government that decides what kind of law to do,” and the subnational level needs to “adapt to the choices of managing the work that ‘rains’ from above” (ITA10; ITA12). “We often find things within a law, things that concern us, that we will need to implement, for which we were never consulted” (ITA21). The ineffectiveness of the consultation mechanism becomes particularly apparent when it comes to the communication of administrative capacity limitations, as outlined by interviewees from the social security agency on a regional level:

We expose our problems especially with regard to the staff [at the regional level]. They know there are people who retire, they know it. But these are things that are in the hands of [central-level] INPS, so what is the decision on hiring, when and how to do it and how to distribute staff, it is not a choice of [a regional office], but it starts from Rome.

Because our resources are what they are, so it’s true that on the other side they don’t care, but sometimes we can’t afford to put in place some government provisions that are given in a short time. So, in my opinion, we need the possibility of communication, so to listen to us too.

While subnational bodies are hence hardly able to mobilize for administrative resource expansions, the authorities at the national level – due to their higher proximity to political decision-makers – are in a somewhat better position to communicate such demands. Yet, these demands remain unsuccessful in most instances and hence are merely symbolic in nature, given the overall constraints characterizing the allocation of additional administrative resources (see the discussion in Section 8.3.1.2). Even though there are formal channels through which the agencies can signal the need for more resources, predominantly their requests for more resources are acknowledged but not approved (ITA01). At the sectoral ministries, demands for capacity expansion have higher chances to be met with partial supply at least, as long as resources are actually available:

Demands are made by the general manager about the number of resources needed, and then the administration, when it has these resources, tries to allocate them in the most equitable way possible, however, this thing does not happen very quickly.

In sum, we have seen that – regardless of the policy sector in question and despite minor variation between national and subnational levels of government – Italian implementation bodies display an extremely high vulnerability to being overloaded by ever-growing burdens. In the Section 8.4, we take a closer look at the extent to which this challenge manifests itself in organizational policy triage.

8.4 Organizational Policy Triage: Sewn to the Edge

Political blame-shifting opportunities and limited chances for resource mobilization render Italian implementation bodies highly susceptible to overload. It is therefore hardly surprising that implementation bodies – across the board – complain about growing burden loads that are not matched by corresponding expansions of their administrative capacities. As a result, policy triage is a rather frequent and severe pattern characterizing implementation activities in both policy sectors under study. When considering that implementation bodies are extremely exposed to being overloaded, it is almost surprising that triage levels are not even much higher.

8.4.1 The Growing Gap Between Implementation Burdens and Administrative Capacities

Our empirical findings impressively demonstrate that Italian implementation bodies are confronted with a double challenge of growing workload and stagnating or even declining administrative capacities. This scenario applies to national and subnational authorities in both sectors.

For the environmental field, an interviewee from the MET provides a concise summary of this development: “I am used for 24 years to see that every year we have fewer human resources and more burden. And there is no end to this process” (ITA24). Similar claims are made by ISPRA officials: “Not only tasks are always growing, there are increasing challenges: money that is less, and less funding” (ITA04). Aside from additional workload associated with the implementation of European Union (EU) directives (ITA05; ITA08; ITA07), subnational implementation bodies emphasize growing coordination needs that emerge from growing policy interdependencies – “It’s not only because of direct workload, but because of workload caused by other units” (ITA08).

At the same time, there is a clear pattern of dramatically increasing capacity bottlenecks. This applies in particular to subnational organizations. Limitations include not only lacking personnel but also missing expertise and the absence of appropriate organizational structures: “There is a lack of staff, lack of resources and also a certain lack of organization. We have many directives from above, so it is increasingly difficult to be efficient in performing many different types of work” (ITA02). While national-level authorities – within strict limits and delays – might apply for modest resource expansions (ITA24), the situation for subnational bodies at the regional, provincial, and municipal level is much more difficult: “But we can do nothing and there are no possibilities, and we have many, many times, in many occasions, we have asked for another person, but in vain” (ITA05; ITA25). One environmental sector manager says that she meets once a week with her political counterpart and often brings up resource issues, but the answer is that all departments are facing the staff problem and that nothing can be done (ITA11). As a consequence, “we’re a little on the edge, a bit at the limit in the sense that I do not know how it can continue to grow the load” (ITA04). In this regard, a particular problem that has been mentioned in most of the interviews is the aging workforce and the lacking replacement of retiring staff: “Every time that we try to hire one or two or three new people, in the meanwhile, one or two or three retire” (ITA02). This implies not only “an enormous increase in the workload of those who stayed” (ITA01), but also problems in terms of appropriate education and expertise (e.g. with regard to technical and computational skills), as “time comes when it’s not easy to learn how to do new things” (ITA10). As one interview partner puts it:

When I started working in 1994, we were 12 only for air quality. [Now] we are only 4, […] but we are old, with a lot of experience. But we don’t have time because of the increase in the directives, the issues increase. We have a lot of administrative burden for things that 20 years ago we were able to do with a simple letter.

When turning to social policy, the picture is essentially the same. At the national level, MLSP interviewees complain that “workload is indeed always increasing,” implying that “the situation of crisis, or emergency is constant” (ITA18). This claim is reinforced by INPS representatives: “The officials had to get used to making not one product [i.e., service] or two, but to make ten. […] As it once was, that everyone had one service to do, that does no longer exist” (ITA14). Also, the bodies operating at the subnational levels emphasize that “we have certainly recorded a very, very significant workload increase” (ITA12), resulting from the growing number and complexity of policies: “For us today, the legislation that was initially fairly simple and straightforward has become very tangled” (ITA10).

I would say that in the last five years, there was a large shift of policies from the state to the regions. And with it came an exponential growth in demands and requirements from the state to the regions. The burden and therefore the trouble is also due to the fact that, at the central level, the demands are more pressing and more complex.

Yet, similar to the environmental field, these massive increases in burden load are not matched by capacity expansions. The general situation is summarized by an MLPS official, claiming that “with the decrease in staff and the ever-increasing new services, we find ourselves in a situation where this workload could no longer be handled,” implying that “we are quite down to the bone on human resources; it becomes very difficult” (ITA18). Major problems emerge from lacking new recruitments in exchange for retirements, as emphasized by INPS officials: “Our headquarters are in a dramatic situation. Having 40 percent of people over 60 is very serious because a lot of people are going to leave, and we don’t expect to get new entries in the next one or two years” (ITA10; ITA12). A particular challenge in this regard is the lack of technical knowledge: “We really need young people and young officials. And this is crucial […] I find myself with a person who has already worked 30 years who can’t make a jump to manage complex [and digitalized] practices” (ITA14). This overall impression is also shared by regional authorities: “Many people are retiring and are not being replaced. So, it is clear that workloads are getting heavier, and people are facing more issues and workloads, so indeed, this problem exists, and we feel it” (ITA15; see also ITA17).

8.4.2 Organizational Policy Triage

In view of the situation described, it is hardly surprising that the routine activities of Italian implementation bodies in both sectors under study display high degrees of policy triage. At all levels of governments, triage occurs very frequently, and in particular at the subnational level, triage is rather severe.

Organizations regularly need to prioritize certain tasks and deadlines, but throughout the interviews it is maintained that the essential aspects of policies are implemented, even if only superficially and with delays. Tasks are prioritized on the basis of deadlines, emergencies, and societal value, following budgetary, but also political reasons.

In the environmental sector, national-level organizations – MET and ISPRA – show significant signs of overload-induced triage. For the MET, triage is a frequent, albeit rarely severe phenomenon. Triage becomes apparent by the fact that tasks are overall handled less precisely than required. Moreover, there is a clear priority attached to the implementation of EU policies over national policies. Triage means “[…] overloading the people [to implement tasks] but with less attention. So in a less accurate way, but at the end, we cannot miss a schedule, we cannot avoid tasks that are that we are in charge for”; “[…] every part that is coming from European Union has a maximum priority” as it is “very often more prioritized than that from national level, because we know that colleagues from European Union are stricter in rules and in schedule and so on, more than offices at the national level” (ITA24). For ISPRA, a rather similar pattern applies: “The shortage of time necessarily leads to simplifying procedures as much as possible […what suffers] is the quality of the in-depth study that is buried in that specific investigation” (ITA01). At the same time, ISPRA prioritizes certain tasks (EU policies as well as “emergencies”): “We have to cope with limited resources, limited to a set of tasks. We go to concentrate on some situations that are considered more problematic, neglecting other tasks. It is obvious that here lies the risk of neglecting situations that then become problems” (ITA01; ITA19; ITA04). Despite highly frequent triage, however, routine tasks can still be implemented (ITA04), however, at the expense of many other activities:

We only can carry out the routine. [There is no] space for research. Absolute zero. There are no more projects, nothing, just this very heavy core […]. Specific investigations, we don’t do it anymore. We limit ourselves to comparisons with the legal limits on the limits set, parameters set. Full stop. Nothing else is done. And this is not nice. It is not nice because investigations and screening should also be carried out on these new emerging pollutants. […] Before we had a broader vision, a little more knowledge of the territory, too. Now, we are very, very specialized and we do our little piece and then we pass the ball on to the others.

The picture looks gloomier as soon as we turn to the subnational level, where triage is not only frequent but also partially more severe, entailing cases of de facto non-implementation. For instance, implementation bodies are in many instances unable to fulfill their monitoring tasks. “We should do a whole series of technical monitoring activities also relevant in the field and we don’t have the strength to do them or the resources. […] But these are things we should have started ten years ago and therefore we are very late” (ITA11). The situation is quite grave as “[…] the infringements are raining on us […] we always run behind the emergencies. Then there are environmental disasters, floods, so let’s say that the priorities are given by emergencies and after it is handled, comes the rest” (ITA03). This implies that “there are some jobs that we have been talking about for years with regional officials who tell us this is what we have to do, but we haven’t done it yet, because they are the ones who don’t give us the input to move forward” (ITA23).

The lack of resources is very much felt by the regional environmental protection agencies as “[…] there is no longer a concern only about [quality] but often more about staying on time” (ITA23). This means that the employees “carry out institutional activity that by law must be carried out but can’t do anything else” (ITA25). However, “sometimes, we are not able to do all the things we have scheduled” (ITA03). “Even [prioritizing] is quite impossible because we have no facultative activities, but we have to focus on the most important activities” (ITA07).

On the provincial level, things follow a similar pattern. The number of employees in the provinces has been reduced to a drastic extent – “we practically canceled the administrative power of the provincial level in Italy” (ITA02). This reduction in personnel was not followed by a reduction in tasks (ITA08). The local-level laboratories of the environmental agency are going through the same trend of workforce reduction – “what three laboratories did before is now all in our laboratory where the staff has more than halved over time” (ITA09) while the tasks increased. The situation is dire as “[…] every year some new task arrives when they assign goals, every year they add because this is missing, that is missing. And yet the workload has dropped very little, very little” (ITA09). As in the ISPRA offices, there is “space for zero research, absolute zero” and the standardization of the type of the tests has “led to a very flattening of the work because we have become […] like the hens closed in the cage that every day make the same egg, the same, that is there is no more space for anything but work routine” (ITA09). Overall, subnational bodies frequently rely on policy triage, entailing in many instances that tasks are not implemented at all:

We are working on it like an accordion in the sense that we’re throwing acoustics on it. And then we leave for a moment, and the times are dilating, people are waiting for us to move to air pollution, we compress time, like Einstein’s general relativity, yes, we try to distribute the inefficiency, we distribute it to make everyone a little unhappy.

In the social sector, patterns of triage are comparable to the environmental field. Bodies operating at the national level frequently resort to policy triage; yet, triage is less severe than for subnational authorities. This holds in particular for the MLPS, where interviewees say that essential tasks are basically fulfilled, although “everything is done a little less thoroughly. […] Certainly, we could do better without a doubt” and the administration is working at its limits: “with no more space; we are reaching saturation” (ITA18). In addition to the fact that tasks are generally addressed less thoroughly, the lack of sufficient personnel implies that certain more pressing tasks are prioritized:

We are too few. I mean, working on this measure in my office, there are three people, and it’s totally inadequate. I have to provide indications, clarifications and whatever to 8,000 municipalities, to 20 regions, and many employees, that work on the measure […]. This inevitably means that we continuously choose some priorities, leaving something else behind […]; we try to follow the real priority rather than formal indicators of productiveness.

INPS offices also report a shortage of personnel and are forced to prioritize “the most imminent deadlines” but are in general able to complete all tasks, even if sometimes with delays and with strong needs for prioritizing tasks according to social needs (ITA37). This sentiment is echoed by the regional and provincial level INPS offices that “[…] are already struggling for the current [workload], where all resources are fully committed” and carry out triage by putting “more emphasis on the services for the people who are most in need, therefore on situations of poverty, marginalization, social exclusion” (ITA36). The triage process starts becoming very grave as:

We’re always behind important things, which we can’t keep up with, both ourselves and colleagues from other locations. Lately it is becoming – now, not in terms of performance, because we cannot compare ourselves with a hospital, with doctors, for goodness’ sake, they do a very important job that we cannot even think of – however, unfortunately, we now look like an emergency room, we work for emergencies.

Regional government authorities face a similar situation, and “[…] since you can’t do everything, we have to continually see what the most important thing at that time is. So, work on the basis of urgencies” (ITA13). In this regard, further problems emerge from coordination with subnational INPS offices and resulting in triage spillovers:

We have to coordinate, follow the [provincial] offices, respond to the external user. And so it’s a whole chain. So, if we are unable to coordinate the work on the territory of the offices, because the work changes, because the benefits are so many and increasingly evolving, automatically even our [provincial] offices are unable to give adequate answers.

This means all the tasks are implemented, but sometimes with a delay, which the employees have learned to accept. As one interviewee puts it: “There is no choice […]. We’ll take longer sometimes, but we decided it’s okay. We’ll take on the onslaught of angry people at the counter as instead of paying in 30 days, we’ll pay in four months. We don’t have tools and we can’t hire ourselves” (ITA10). Provincial and municipal authorities face an identical situation (ITA20). Yet, in spite of delays and prioritization, “to date, [it] has not emerged that we should do something, but we do not because we can’t” (ITA13). While tasks are being completed, the activities are carried out in a somewhat superficial manner, so the quality of the output is lacking. One interviewee sums it up as follows: “We have not yet touched the point of no return. Because […] we are still alive and we are still in a position to be able to devote ourselves to it, with a dose of effort that – I will repeat – is not visible from the outside” (ITA15).

In conclusion, our empirical findings show a pattern of relatively high policy triage in Italian implementation organizations. Across both policy sectors under study, national and subnational authorities frequently resort to triage routines; triage has become the standard mode of organizational behavior. Yet, triage to a considerable extent manifests itself via delays and less through assessments that are equally distributed across tasks, as well as prioritization of issues that are obligatory or pressing over facultative tasks. At the same time, however, especially for subnational bodies, this comes with more severe trade-offs, implying that certain – nonetheless important tasks – are largely neglected. Despite these drawbacks, overall implementation deficits seem to be much less pronounced as one would have expected in view of the extremely high overload vulnerability of Italian implementation bodies. As will be shown in Section 8.5, this surprising finding can be explained by pronounced efforts of overload compensation that help to mitigate the need for triage decisions.

8.5 Preventing the Worst: Organizational Commitment to Overload Compensation

Implementation bodies in both sectors under study display pronounced efforts to internally compensate for overload. In this regard, different approaches prevail, including, in particular, outsourcing, the recruitment of temporary staff via internal or external funding, as well as the mobilization of working commitment of organizational staff.

At the ministerial level, both MET and MLPS heavily rely on external expertise in order to compensate for the lack of internal capacities: “We are taking people hired on a temporary basis from outside. So, the strategy that this specific ministry has adopted is when there is an increase of burdens is to increase the utilization of external assistance” (ITA24).

Outsourcing is a very important factor throughout the Italian public administration. Many of my tasks are outsourced, especially with regard to the monitoring part of policies, or the management of IT platforms, of technical tools. And in outsourcing there is the whole part of training on the territories regarding the projects already started, because in any case we are unable to guarantee, at least to date, internal technical assistance.

Yet, interviewees are well aware of the challenges related to the outsourcing of services, “which has worsened the quality of the Italian public administration because it has forced a lot of knowledge and many skills outside the perimeter of the public administration, binding us and also opening us to being ‘blackmailed’ by the entities that take care of the outsourced services” (ITA18).

In addition to outsourcing, in particular, implementation bodies at the regional level are strongly engaged to fund additional temporary staff by applying for EU-funded or World Bank–funded projects and to rely on this staff also for the implementation of non-project–related policies (ITA02; ITA21; ITA19). This way, implementation authorities partially compensate for the fact that regular hiring for public administration positions has largely been halted in the past three decades: “It has been a long time since the concorsi have been made. We are talking about 1996, 1998, 2000, 2002 […]” (ITA10).

Yet, the main compensation approach that characterizes more or less all implementation bodies under study is the exploitation of existing resources, with staff voluntarily working overtime. As ISPRA interviewees note, for example, overload is mainly managed through extreme personal sacrifices on behalf of the staff:

[…] the activities are done, but in absurd conditions, in really harsh conditions and with personal sacrifices. For example, two of my colleagues who have a contract were precarious and part-time, they worked for free while waiting for the new contract because the times are long, [and] you can’t stop. Then if you stop for three months or four months to get a new contract, things get stuck. Except then you find it all on yourself later, but everything collapses if there is an infringement procedure and companies have very high penalties. These people […] they worked practically in five years, one year for free without being paid. This is the reality if we talk about a public institution.

This statement is exemplary for similar information and assessments provided by interviewees from varying organizations. The overall spirit seems that there is no other way as to maximize internal efforts as much as possible: “We do it; we struggle, but we do it” (ITA12) and “fortunately, the colleagues, who are ready to make overtime, pull up their sleeves” (ITA18), implying that “outside [of the administration], these difficulties are not apparent. Because anyway we, on the inside, always try to respond to any request” (ITA15).

Yet, what accounts for this strong commitment within implementation bodies to engage in overload compensation? We argue that development is mainly due to strong policy advocacy. Italian organizations in charge of social and environmental policy implementation have developed internal routines that place strong emphasis on the quality, internal consistency, and effectiveness of the policies up for implementation.

In the environmental field, common professional backgrounds are a strong driver of policy advocacy. Most of the staff in the environmental sector comes from natural science, predominantly chemistry, chemical engineering, and biology. There is a strong professional ethic displayed as the interviewees take pride in their technical skills and referring to themselves as “the technicians” (ITA03; ITA04; ITA11). Statements such as “It is needless to do superficial things, that it is the only thing we have, our technical value and doing well as technicians. And if this takes a little more time, we are willing to take it” (ITA03) are often expressed as a reason for hard work. One of the ISPRA interviewees described that the initiatives to streamline the processes and to reduce slack come directly from the employees and the team spirit they feel: “[…] it’s up to us to make the activities run. It’s bottom-up, it is up to us to organize ourselves to complete the work within the deadlines. So, we were not told to start cooperating with the other units, but just speaking with colleagues, they say ‘I need this kind of data,’ then I’m able to produce such information. So, it’s a bottom-up process” (ITA19).

Especially on the regional level, it is the professionalism and dedication to the environmental goals that push the staff to go on “[…] despite what people say about public administration, we work a lot, especially because we believe in nature, we believe in our work. And we believe that we can make the difference, sometimes small, small difference, but sometimes it happens” (ITA05). The dedication to work in the environmental sector translates to “[…] working during the night, working during the weekend, without problem, even if in Italy, the salary for service is not so high. But in environment, this is common. Because we like, no, we love the work that we do because we consider it important” (IT21042302). However, if the period of overburden extends over a prolonged period, “[…] there is a bit of bad mood, there is a bit of fatigue” (ITA22).

Strong advocacy can also imply that implementers – for the sake of policy effectiveness – deliberately ignore ill-designed policies. Disagreement with the policies can be such that employees engage in passive sabotage of policies: “The politicians request every time that you have to do everything, but my reply is immediately that everything is not feasible. What is feasible, I do, what is not feasible, I don’t spend time to do 50% of the job and produce nothing” (ITA02; see also ITA05).

In social policy, degrees and backgrounds are mostly social science related, with a concentration in social care. However, the uniformity of professional backgrounds is perhaps not the main driver behind overload compensation. Instead, as interviewees from MLPS and INPS put it:

[…] there is precisely the feeling, that we help people receive the services they have asked for and that we solve situations that were stuck. So there’s a big social aspect. Perhaps this is the thing that, personally, makes me appreciate this work, that you are useful, there is a certain usefulness.

INPS as a body that, if it works, moves hundreds of thousands not only of euros, but also of benefits, disbursements, liquidations, so if things go wrong, the INPS is responsible for the distress of many citizens who do not receive money, who may not know how to go on, because they are not receiving what is due to them, so certainly yes. If the INPS works, society is happier.

A similar sentiment is expressed at the regional social security office: “[…] what keeps me going is the satisfaction of what I do and the fact that the person is happy, […] the fact that I was able to unlock that thorny situation, which prevented that person from receiving what was rightly due” (ITA39). Teamwork is also employed to handle emergencies. As one employee of the regional social policy office puts: “Here we are in an organizational situation where we know what the deadlines are. We know what the important activities are. If there is an immediate deadline, it means that everyone is focused, not only individually” (ITA13). Also provincial-level employees are very much dedicated to societal values. As a rule, interviewees feel “passionate about work and I know that regardless of the feedback that I may or not have, I know my social usefulness and that this department can have an impact on my provincial reality” (ITA10).

The motivation to work for the cause – protection and care for the most vulnerable groups – is what drives the staff to work extra hours, weekends, and holidays (ITA12; ITA16; ITA39), while branch managers also process benefit claims in addition to their managerial work (ITA10). Digitalization and automation of services play an important role in facilitating the overload in the social policy sector (ITA10; ITA11; ITA37). Building up on these processes, the so-called subsidiarity approach has been developed where all the services of a certain type can be taken over by another provincial office, if it happens that any of the offices lacks time or personnel to handle all the tasks within given deadlines (ITA11).

8.6 Conclusion

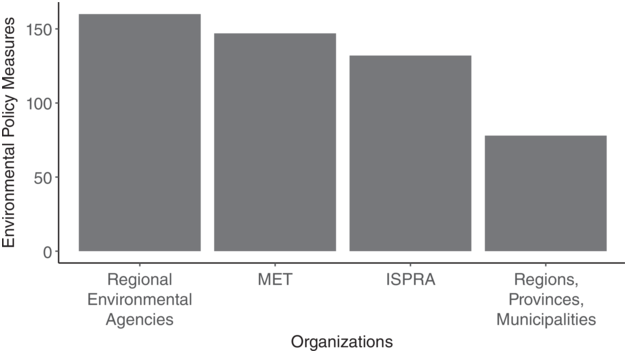

The case of Italy provides strong support for the theoretical considerations developed in Chapter 2. All Italian implementers surveyed are confronted with either high or medium levels of triage (see Table 8.1). On the one hand, in both social and environmental policy, implementation bodies are extremely vulnerable to being overloaded by the strong growth of sectoral policies. Politicians who have strong incentives to engage in policy production face basically no constraints to shift the blame for implementation failures to sectoral authorities. The latter, by contrast, have very few opportunities to mobilize additional resources. On the contrary, austerity pressures even implied that – by not replacing retired staff – overall personnel capacities and expertise are in decline.

| Organization | Sector | Triage level |

|---|---|---|

| Institute for Environmental Protection and Research (ISPRA) | Environment | High |

| Regional Environmental Agencies | Environment | High |

| Regions, Provinces, Municipalities | Environment | High |

| Ministry of Environmental Transition (MET) | Environment | Medium |

| Ministry of Labor and Social Policy (MLSP) | Social | Medium |

| Social Security Institute (INPS) | Social | Medium |

| Regions, Provinces, Municipalities | Social | Medium |

On the other hand, we have seen that strong and widespread internal efforts of sectoral organizations to compensate overload via outsourcing, temporary recruitments through external funding, and, in particular, engaging in working overtime partially mitigates the need to engage in policy triage. Although – compared to the other countries under study – triage routines are a highly frequent, more or less regular phenomenon, trade-off decisions only sometimes (and in particular at the subnational level) have more severe consequences, especially, when certain tasks (e.g., emission monitoring) are completely neglected because of lack of capacities. Yet, despite this pattern, overall implementation effectiveness still reaches a level that is surprisingly good in view of the given incentives for policy overproduction and the parallel shrinking of bureaucratic capacities. Yet, it is also obvious that there are clear limits to overload compensation. While, overall, it seems that policy implementation in Italy takes place under precarious conditions, there are clear indications that in some cases, overload compensation has not only reached but also clearly exceeded its limits.