Introduction

After decades of growing electoral support and policy influence, the far right is experiencing a sharp increase in bottom‐up protests (Mudde, Reference Mudde and Mudde2016, p. 613).Footnote 1 These are no longer occasional gatherings by few activists in small provincial towns, but a rather common occurrence across Europe. This is best illustrated by the sizeable demonstrations by PEGIDA in Germany (Berntzen & Weisskircher, Reference Berntzen and Weisskircher2016), Golden Dawn in Greece (Ellinas, Reference Ellinas2020), as well as the media stunts by Generation Identity across Europe (Virchow, Reference Virchow, Simpson and Druxes2015). Today, almost all countries offer a fertile ground for far‐right collective action – even regions that had been confronted with little mass immigration, defying the notion that migration breeds far‐right mobilisation (Minkenberg, Reference Minkenberg2019). But what explains far‐right mobilisation in the protest arena? The main contribution of our article is to bridge previous research on the far right and social movements to uncover the drivers of far‐right protest mobilisation across Europe.

The scholarship on the far right has generally devoted little attention to the comparative study of grassroots protest mobilisation. In our view, such an oversight risks obfuscating a full understanding of contemporary far‐right politics, for various reasons. First, many contemporary far‐right parties stem from the movement sector (Kitschelt, Reference Kitschelt, Katz and Crotty2006; Pirro, Reference Pirro2019); overlooking far‐right protest mobilisation risks providing only a partial – that is, ‘electoralist’ – account of one of the pressing political phenomena of our time. Second, it downplays the fact that protest mobilisation enhances the public visibility of the far right and the social profile of its claims (Amenta & Elliott, Reference Amenta and Elliott2017). Third, recent developments such as the establishment of the Rassemblement Bleu Marine in France or the cooperation between the Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) and PEGIDA in Germany have shown that the boundaries between the electoral and protest politics of the far right have become more porous (Castelli Gattinara & Pirro, Reference Castelli Gattinara and Pirro2019). Finally, individual‐level studies also confirm the growing relevance of non‐electoral participation among far‐right citizens (e.g., Torcal et al., Reference Torcal, Rodon and Hierro2016; Pirro & Portos, Reference Pirro and Portos2021), calling for greater attention to the non‐electoral side of far‐right politics.

These elements challenge the long‐standing view that extra‐parliamentary action is chief preserve of the (libertarian) left (Bremer et al., Reference Bremer, Hutter and Kriesi2020), and that far‐right protest mobilisation could be reduced to racist and violent activity (Koopmans, Reference Koopmans1996) or other forms of countercultural activism (Veugelers & Menard, Reference Veugelers, Menard and Rydgren2018). Scholars are increasingly acknowledging the effect of protest mobilisation on political conflict (Borbáth & Gessler, Reference Borbáth and Gessler2020). However, no study has so far offered a systematic empirical analysis of the determinants of protest mobilisation by far‐right collective actors in Europe. We claim that cross‐national and longitudinal accounts of far‐right extra‐parliamentary activities are long overdue.

With this article, we attempt to fill this gap in two ways. Theoretically, we bridge previous research on the far right and social movements to advance hypotheses on the drivers of far‐right protest mobilisation based on grievances, opportunities and resource mobilisation models (della Porta & Diani, Reference della Porta and Diani2006; Quaranta, Reference Quaranta2016). Methodologically, we use a unique dataset combining novel data on 4,845 far‐right protest events in 11 East and West European countries (2008–2018) with existing measures accounting for the (political, economic and cultural) context of mobilisation. We find that classical approaches to collective action can be fruitfully applied to the far right. However, neither explanations based on grievances nor those looking at political opportunities can, by themselves, account for the variation in the level of far‐right protest. Indeed, far‐right protest mobilisation is also likely to occur when collective actors possess specific material and symbolic resources linked to their ideology, organisation and networks. These findings have important implications for the understanding of far‐right politics in advanced democracies. They show that far‐right mobilisation in the protest arena not only rests on favourable circumstances, but also on whether far‐right actors can profit from them. This reinstates research on far‐right collective action in the broader fields of political sociology and comparative politics, resonating with notions of the far right as an active shaper of its own fate rather than a simple victim of circumstance (e.g., Art, Reference Art2011; Berman, Reference Berman1997; Carter, Reference Carter2005).

The article proceeds as follows. We first present the theoretical foundations of our work, relying on insights from the study of social movements and far‐right parties. We then introduce the research design and data, and move on to the empirical analysis. Finally, we discuss the main findings and implications of our study.

Towards a far‐right protest mobilisation paradigm

Explanations of political protest, developed in the field of social movement studies, have not been systematically applied to the far right (Caiani et al., Reference Caiani, della Porta and Wagemann2012). While the contemporary far right is a heterogeneous phenomenon with ramifications in both the electoral and protest arenas (Minkenberg, Reference Minkenberg2019), rarely have studies of elections and protests relied on mutual insights (McAdam & Tarrow, Reference McAdam and Tarrow2010). This clashes with the mounting evidence linking political parties and social movements to the reconfiguration of political conflict in the wake of globalisation and the recent European crises (Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Lorenzini, Wüest and Hausermann2020).

Comparative politics scholars have been mostly concerned with the study of far‐right parties and their voters (Golder, Reference Golder2016), often overlooking non‐electoral dynamics (but see Hutter & Borbáth, Reference Hutter and Borbáth2019). Conversely, social movements scholars have long privileged research on the progressive side of politics (della Porta & Diani, Reference della Porta and Diani2006), neglecting the nativist portion of contention (but see Blee, Reference Blee2007; Giugni et al., Reference Giugni, Koopmans, Passy and Statham2005). As a result, far‐right protest mobilisation remains a blind spot in the discipline and the empirical study of its determinants has been sparse at best. We argue that combining classical theories of social movements and research on far‐right political parties might offer valuable insights into the causes of far‐right mobilisation in the protest arena.

We define far‐right protest mobilisation as the set of demonstrative, confrontational, or violent protests in which nativist groups partake.Footnote 2 These forms of grassroots mobilisation refer to the broader set of extra‐parliamentary activities involving far‐right ‘collective actors’ – that is, political parties, ‘movement parties’ and social movements. We therefore keep far‐right collective actors as the prime focus of attention through their (co‐)organisation of, and participation in, protest events (Borbáth & Hutter, Reference Borbáth and Hutter2020; Pirro et al., Reference Pirro, Pavan, Fagan and Gazsi2021). By doing so, we seek to capture the widest possible range of non‐institutionalised or unconventional action forms by the far right, and thus not only account for those events directly sponsored by far‐right parties at the grassroots level (Ellinas, Reference Ellinas2020; Greskovits, Reference Greskovits2020).

Besides the substantial advantages deriving from this definition, our approach improves the common understanding of the far right in at least two ways. On the one hand, we consider multiple forms of action instead of limiting far‐right protest to violent acts only; on the other, we factor in participation at the extra‐parliamentary level instead of interpreting far‐right protest predominantly in terms of protest voting. Sociologists have in fact often equated far‐right protest mobilisation with the use of violent repertoires of action (Koopmans, Reference Koopmans1996), limiting non‐electoral participation to unlawful and subaltern countercultural activities (Veugelers & Menard, Reference Veugelers, Menard and Rydgren2018). Political scientists have instead used the notion of ‘protest’ for the study of far‐right party vote – a display of discontent with political elites (van der Brug et al., Reference Brug, Fennema and Tillie2000) however limited to electoral participation. In our understanding, far‐right protest mobilisation represents a specific, non‐electoral venue for political participation, through which collective actors express their grievances, advance their claims and prompt reactions from politicians and citizens.

Overall, the far‐right scholarship has engaged little with protest mobilisation and its determinants. This notwithstanding, seminal contributions in the field have successfully applied concepts of social movement theory to define processes and factors affecting the fortunes of contemporary far‐right parties (Arzheimer & Carter, Reference Arzheimer and Carter2006; Rydgren, Reference Rydgren2005). Furthermore, a growing strand of literature strived to connect social movements and political parties of the far right, looking at the concomitant engagement of far‐right collective actors in the electoral and protest arenas (Froio et al., Reference Froio, Castelli Gattinara, Bulli and Albanese2020; Minkenberg, Reference Minkenberg2019; Pirro, Reference Pirro2019). We believe that these instances of cross‐fertilisation can be further exploited to formulate hypotheses about the drivers of far‐right protest mobilisation.

Mobilising on grievances

Social movement studies offer valuable insights for the study of far‐right protest mobilisation and its determinants. Research on new social movements has emphasised the combined role of grievances, opportunities and resources in heightening protest levels (Quaranta, Reference Quaranta2016). Despite the little exchange between this strand of research and the literature on party politics, a number of scholars turned to the concepts of discursive and political opportunities to study the far right (Arzheimer & Carter, Reference Arzheimer and Carter2006; Giugni et al., Reference Giugni, Koopmans, Passy and Statham2005). We advance hypotheses on the drivers of far‐right protest and present them in the form of three heuristic models: grievances, opportunities and resource mobilisation. Instead of considering them as alternative explanations, factors linked to discontent, the political context and organisational strength may in combination lead to increased grassroots mobilisation.

Since the 1960s, political sociologists suggested that changes in levels of protest mobilisation can be explained by specific preconditions fostering (or inhibiting) social grievances. So‐called ‘grievance’ models see these factors as altering the social status quo and triggering some form of collective behaviour (Gurr, Reference Gurr1970), in both objective and subjective terms (Klandermans et al., Reference Klandermans, Toorn and Stekelenburg2008; Snow et al., Reference Snow, Cress, Downey and Jones1998). According to this view, protest is just one venue to express frustration and dissatisfaction, so the expectation is that feelings of relative deprivation and injustice will lead people to mobilise to change the status quo. To put it simply, the greater the grievances, such as in periods of worsening economic conditions and stagnation, the higher the level and magnitude of protest (Beissinger et al., Reference Beissinger, Sasse, Straif, Bartels and Bermeo2014). How, though, does this model apply to far‐right mobilisation?

The literature on far‐right parties identifies specific objective and subjective grievances that can spur far‐right protest mobilisation. Research has in fact associated electoral support for far‐right parties to objective socioeconomic grievances, such as rising levels of unemployment in times of economic hardship (Ivaldi, Reference Ivaldi2015) and cultural grievances linked to the presence or increased arrival of migrants (Ivarsflaten, Reference Ivarsflaten2008; Lucassen & Lubbers, Reference Lucassen and Lubbers2012; Stockemer et al., Reference Stockemer, Halikiopoulou and Vlandas2020). While these grievances matter to the extent that they are subjectively perceived and socially constructed (Grasso & Giugni, Reference Grasso and Giugni2016), they can also trigger politically motivated racism, hate crime and grassroots violence against migrants and minorities (Ravndal, Reference Ravndal2017). Previous studies have however shown that the far right also thrives on subjective institutional grievances (Arzheimer, Reference Arzheimer and Rydgren2018; Halikiopoulou & Vlandas, Reference Halikiopoulou and Vlandas2020), such as dissatisfaction with government, democratic institution and existing modes of organised elite‐mass political intermediation (Lamprianou & Ellinas, Reference Lamprianou and Ellinas2016), or ‘the desire to abandon the intermediaries that stand between citizens and rulers’ (Kitschelt, Reference Kitschelt, Mény and Surel2002, p. 179).

Overall, these elements suggest that far‐right protest mobilisation might depend on economic, cultural and institutional grievances (H1). Specifically, we expect that: Far‐right protest mobilisation will be higher in contexts characterised by:

− H1a: negative economic performance (economic grievances).

− H1b: high inflow of migrants and asylum seekers (cultural grievances).

− H1c: high dissatisfaction with democracy (institutional grievances).

Mobilising on political and discursive opportunities

While uncovering some of the crucial drivers of protest, classical grievance models alone have been criticised for neglecting the broader political environment in which mobilisation unfolds (McAdam, Reference McAdam, McAdam, McCarthy and Zald1996). The ‘opportunity structure’ model puts groups’ demands into their political context (McAdam, Reference McAdam1982), focusing on how political opportunities and constraints affect movement interactions with its adversaries, hence prompting or inhibiting collective action (Giugni et al., Reference Giugni, Koopmans, Passy and Statham2005). The intensity of protest might hinge on the political and discursive opportunities at the contextual level, which can be broadly interpreted as the ‘openness’ of the political system to forms of collective action. More precisely, political opportunity structures (POS) correspond to the formal institutional configurations in a political system that might favour mobilisation. Discursive opportunities (DOS) identify the legitimate ideas in the broader political culture, which could facilitate the resonance of specific collective action frames and forms (Koopmans & Statham, Reference Koopmans and Statham1999).

Scholars of the far right have used similar models to identify which institutional and discursive conditions make support for these groups more likely (Arzheimer & Carter, Reference Arzheimer and Carter2006). As regards political opportunities, they refer to the availability of potential allies in government and the presence of institutional access points (Kriesi, Reference Kriesi, Porta and Diani2015). On the one hand, parties in public office may qualify as allies or opponents for the far right; the ideological orientation of government, in particular, will affect the political space available to insurgent forces like the far right (Carter, Reference Carter2005). Parties in government may co‐opt the claims of far‐right movements for either opportunistic or substantive ideological reasons; still, right‐wing governments would probably offer a more favourable context as far as the normalisation and legitimation of far‐right protest and demands is concerned. On the other, the number of access points to a political system is relevant for protest mobilisation, because different institutional configurations provide the far right with multiple channels for inclusion (Kitschelt, Reference Kitschelt, Mény and Surel2002). Contexts characterised by divided government – as for conflict between the executive and legislative branches – offer increased access to institutional channels compared to single‐party control and may thus give more space to far‐right collective actors and their views. As regards discursive opportunities, scholars argue that the far right may benefit from the resonance of its discourse in society and access to the public sphere (van Spanje, Reference Spanje2010). Since mobilisation is contingent on the ability to attract citizens to one's cause, far‐right protest mobilisation might be hampered by measures to counter hate speech and by bans on extremist symbols and groups (Laumond, Reference Laumond2020). The presence of strong counter‐movements might also curb the circulation of far‐right messages and ideas in the public sphere as well as their growth and prospects for mobilisation (Ellinas, Reference Ellinas2020).

It follows that far‐right protest mobilisation might rest on the presence of favourable political and discursive opportunities (H2). Specifically, we expect that: Far‐right protest mobilisation will be higher in contexts characterised by:

− H2a: right‐wing cabinets (POS government allies).

− H2b: conflict between the executive and legislative branches (POS access points).

− H2c: low formal sanctions on extremist ideologies and hate speech (formal DOS).

− H2d: low levels of counter‐mobilisation (informal DOS).

Mobilising resources

Neither grievances nor political opportunity models consider the agency of collective actors. They may thus provide only partial explanations for far‐right protest mobilisation. The ‘resource mobilisation’ model complements the theories presented so far, emphasising meso‐level and organisational factors, and focusing on the role of mobilisation structures to turn grievances and contextual circumstances into protest (Gamson, Reference Gamson1975; Tilly, Reference Tilly2004). In doing so, resource mobilisation theory highlights the role of agency and addresses how collective actors use resources available to craft their own fortunes. For example, the social movement literature stresses the importance of a (quasi‐)professional organisation to mobilise public support (della Porta & Diani, Reference della Porta and Diani2006), suggesting that the material and symbolic resources available to collective actors help explain whether and when groups can seize available opportunities and engage in protest mobilisation. While agency‐based accounts have overall played a marginal role in the study of the far right, these aspects reinstate the role of nativist collective actors in defining their own success or failure (de Lange & Art, Reference Lange and Art2011).

Research on far‐right parties has additionally considered organisational features and ‘internal supply‐side’ factors to explain – in combination with grievances and political opportunities – their electoral performance (Art, Reference Art2011; Carter, Reference Carter2005). For the sake of our enquiry, we distinguish between two types of resources facilitating far‐right mobilisation: symbolic resources related to far‐right actors’ ideology, visibility and networks; and material resources deriving from the degree of institutionalisation and its presence in public office. To begin with, ideology can represent an important symbolic resource for mobilisation. Ideological differences between ‘extreme‐right’ actors (that oppose democracy and are openly nostalgic of interwar regimes) and ‘radical‐right’ ones (that subscribe to the rules of parliamentary democracy but are hostile to minority rights) might affect their public legitimacy, and ultimately determine their overall success or failure (Art, Reference Art2011; Carter, Reference Carter2005). In general, the extreme right remains an electorally marginal phenomenon, whereas radical‐right actors have become progressively entrenched in the political mainstream (Albertazzi & Vampa, Reference Albertazzi and Vampa2021; Mudde, Reference Mudde2019).

Visibility constitutes another symbolic resource for social movements (Gamson & Wolfsfeld, Reference Gamson and Wolfsfeld1993). Especially public visibility, interpreted as the ability of a movement to establish itself and its causes in media outlets (Vliegenthart & Walgrave, Reference Vliegenthart, Walgrave, Semetko and Scammel2012), might normalise and legitimise the far right, facilitating the mobilisation of nativist collective actors. Other resources derive from the network in which these actors are embedded. These could, for example, increase the supply of volunteers and members (Quaranta, Reference Quaranta2016) or the influence and support for its initiatives within a consolidated network (Diani, Reference Diani, Diani and McAdam2003). Large networks may also provide the far right with critical resources such as specialised knowledge on how to run meetings and engage in protest activities, access communication networks with other groups (Froio, Reference Froio2018), and coordinate with like‐minded actors in the protest arena (Pirro et al., Reference Pirro, Pavan, Fagan and Gazsi2021).

Finally, material resources increasing far‐right protest mobilisation might depend on internal organisational factors and on the presence of representatives in public office. Social movements can be quite successful in taking people to the streets (Tarrow, Reference Tarrow2010). Compared to political parties, they invest little in the organisational infrastructure of collective action (in terms of definition of membership, roles and contributions), thus relying on a more vital grassroots base – at least, in the short term (Kitschelt, Reference Kitschelt, Katz and Crotty2006). At the same time, representation in public office – especially at the national and supranational level (e.g., in national parliaments and the European Parliament) – provides access to emoluments and increases the availability of material resources (e.g., money, infrastructures, etc.), which can be used to sustain protest activities, notably by far‐right political parties (e.g., Snow et al., Reference Snow, Soule and Cress2005).

Furthermore, on top of binary distinctions between ‘movements’ and ‘parties’, we recognise a third type of collective actor in transition between these two organisational forms, that is, the ‘movement party’. Movement parties can be understood as social movements that have taken the ‘electoral option’ but still preserve their commitment to grassroots politics and engagement in the protest arena (Kitschelt, Reference Kitschelt, Katz and Crotty2006; Pirro, Reference Pirro2019). Far‐right collective actors’ qualification as movement, movement party or party essentially depends on their degree of institutionalisation (Panebianco, Reference Panebianco1988) but privileging movement over party activities should not be interpreted as a zero‐sum game (Castelli Gattinara & Pirro, Reference Castelli Gattinara and Pirro2019, p. 455). Movement parties are neither a marginal phenomenon nor a rare manifestation of the contemporary far right (Froio et al., Reference Froio, Castelli Gattinara, Bulli and Albanese2020; Pirro & Castelli Gattinara, Reference Pirro and Castelli Gattinara2018). While there are potential trade‐offs between ‘ballots and barricades’, we contend that movement parties might get ‘the best of both worlds’ and sustain their vocation for grassroots mobilisation precisely through the resources coming from representation in public office.

Overall, these elements suggest that far‐right protest mobilisation might depend on the material and symbolic resources available to nativist collective actors (H3). Specifically, we expect that: Far‐right protest mobilisation will be higher when:

− H3a: far‐right collective actors endorse a radical (rather than extreme) ideology (ideology).

− H3b: far‐right collective actors enjoy high public visibility (exposure).

− H3c: far‐right collective actors are embedded in large networks (network).

− H3d: far‐right collective actors take the form of movement parties (organisation).

− H3e: far‐right collective actors are represented in public office (representation).

In this section, we provided an encompassing framework bridging studies on the far right and social movements to predict the effects of grievances, opportunities and resources on far‐right protest mobilisation. Although these explanations have been separated for analytic clarity, we acknowledge that they may come at the cost of simplifying the reality surrounding collective action. The factors underlying these processes may be thus more blurred in practice and jointly help us understand the drivers of far‐right protest mobilisation. Testing these models on 11 European countries should highlight the relevance of these factors, individually and collectively considered.

Research design and data

We test our hypotheses using an original dataset combining novel data on far‐right protest events with existing country‐level measures from the OECD International Migration Database (OECD, 2020), Eurobarometer data (European Commission, 2018), the Parliaments and Governments database (Döring & Manow, Reference Döring and Manow2020) and the Varieties of Democracy (V‐DEM) database (Coppedge et al., Reference Coppedge2020) for 11 European countries between 2008 and 2018. We focus on all those protest events in which far‐right collective actors have partaken. Our collective actors of interest are those far‐right social movements, movement parties and political parties engaging in extra‐parliamentary mobilisations. Observations derive from the coding of 4,845 protest events of far‐right collective actors in Bulgaria, Estonia, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Poland, Slovakia, Sweden and the United Kingdom. All countries were members of the European Union (EU) during the timeframe of this study; however, they differ in terms of institutional opportunities faced by far‐right parties and the rules that regulate electoral competition. The case selection is motivated by our ambition to cover different countries across the EU, account for the variation in the general prevalence of protest activity in these countries and include different types of far‐right collective actors exhibiting a particular vocation for grassroots mobilisation. Among these differences, we are interested in teasing out common patterns of far‐right protest mobilisation across countries. The time period of analysis allows us to control for changing contextual circumstances, including economic conditions during and after the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers in late 2008 and the beginning of the so‐called ‘Great Recession’, changing rates of immigrant populations before and after the peak of the migration policy crisis in 2015, while also controlling for the institutional settings of individual countries. The dependent variable refers to the yearly number of protests in each country, including years in which no protest events took place in one or more countries under scrutiny. Since the distribution of the dependent variable is skewed, we use negative binomial regressions. This accounts for over‐dispersion, given that the variance of the dependent variable is much larger than their means (Cameron & Trivedi, Reference Cameron and Trivedi2013, see Annex B in the Appendix).

Dependent variable

Our dependent variable is the number of protest events in which far‐right collective actors have participated. The quantification of such events is a standard indicator of protest mobilisation in social movement research. One of the main reasons as why far‐right protest mobilisation has not yet been studied comparatively is the lack of large‐scale protest event data covering multiple countries and actors over time. In response to this gap, we have built a unique protest event dataset allowing for the quantitative analysis of protest mobilisation across time and space. Protest event analysis (PEA), a type of quantitative content analysis of media sources, has become a key method of social movement research for its ability to measure the characteristics of protest and protest organisations (Hutter, Reference Hutter and della Porta2014) – that is, the main foci of our study.

Data were collected through a semi‐automated procedure within the framework of the project Far‐Right Protest in Europe (FARPE). Our dataset is the first comparative dataset systematically accounting for far‐right protest mobilisation in Eastern and Western Europe after the breakout of the Great Recession. Protest data were collected from two sources. First, we looked at the main quality newspapers in each country, in light of their nationwide distribution, high reputation and for the fact that they report more extensively on political issues compared to other types of outlets (Hutter, Reference Hutter and della Porta2014).Footnote 3 We limited our selection to one outlet in order to maximise cross‐country comparability, relying on independent newspapers with a nationwide coverage and readership. These sources are particularly suited for comparative studies as they mirror national debates in detail and influence the editorial decisions of other media outlets (Hutter, Reference Hutter and della Porta2014).Footnote 4 Second, we integrated these sources with protest events retrieved from the website of far‐right collective actors themselves. These can be considered a reliable, albeit partisan, source for the measurement of mobilisation: they provide official information on the occurrence of protest events to followers and external observers (including journalists), while often also reproducing the bulk of information shared by the far right via social media (Kruikemeier et al., Reference Kruikemeier, Aparaschivei, Boomgaarden, Van Noort and Vliegenthart2015; Nitschke et al., Reference Nitschke, Donges and Schade2016).

Our ‘actor‐centred’ approach combines systematic data gathered from multiple sources (Castelli Gattinara & Froio, Reference Castelli Gattinara and Froio2019; Pirro et al., Reference Pirro, Pavan, Fagan and Gazsi2021), presenting at least two advantages compared to extant work based on PEA. First, we combine partisan as well as non‐partisan sources – that is, news items from the websites of far‐right collective actors and national quality newspapers, respectively. This strategy is meant to overcome potential sources of bias deriving from selective media reporting on protest events (Davenport, Reference Davenport2009) and capture the largest and/or most accurate number of protest events in which the far right has participated. Second, we do not restrict our data collection or analysis to circumscribed time periods. We are here concerned with covering the entire 2008–2018 period and the largest set of events involving far‐right collective actors.

Data derived from these sources delivered 4,845 protest events from the 11 countries mentioned above.Footnote 5 The identification and coding of each protest event followed the procedures established in previous cross‐national comparative projects, including tests for intercoder reliability (Berkhout et al., Reference Berkhout, Ruedin, Brug, D'Amato, D'Amato, Brug, Ruedin and Berkhout2015; see Annex A in the Appendix).

Independent variables

The independent variables measure grievances, opportunities and resources. To study the effect of grievances on far‐right protest mobilisation, we use both objective and subjective measures. As per the objective indicators, we address economic grievances in terms of the state of the national economy,Footnote 6 using the Economic Performance Index (EPI) (Khramov & Lee, Reference Khramov and Lee2013), a standard indicator offering a composite weighted measurement of the state of the economy accounting for inflation, unemployment, deficit and growth. When the index is above 95, economic performance is ‘excellent’, above 90 is ‘good’, above 80 is ‘fair’, above 60 is ‘poor’ and below 60 is ‘bad’. Cultural grievances are then measured by means of the annual inflow of migrants (measured as the total annual inflow of foreign population, in thousands).Footnote 7 We measure subjective institutional grievances as the level of satisfaction with democracy in each country.Footnote 8

As regards political opportunity structures, we differentiate between the availability of potential allies and institutional access points. On the one hand, we consider the left‐right orientation of national governments; right‐wing cabinets might constitute an ally for far‐right protest groups. We used PARLGOV indicators to identify the ideological orientation of parties in government, weighted by the share of seats held by each party.Footnote 9 On the other, we measured the availability of institutional access points using the divided party control index from V‐DEMFootnote 10, based on the general notion that divided systems offer more opportunities for protest actors and claims. Positive values indicate divided government, whereas negative ones mean that a single party controls the executive and legislative branches. In addition, we consider two indicators of discursive opportunity structures. First, we anticipate that opportunities will be scarcer in contexts that enforce bans on extremist parties and far‐right groups, and use a specific item on yearly party bans available in the V‐DEM dataset.Footnote 11 In addition, we account for the more informal constraints on far‐right mobilisation by including an item measuring, for each year and country, the share of far‐right protests that elicited some form of counter‐mobilisation (0 = events with no reaction), further differentiating between events that prompted verbal reactions only and those that triggered contentious counteractions, such as boycotts and confrontation.

Finally, we include five items measuring the resources available to the far right. First, in order to account for the ideological orientation of far‐right collective actors, we rely on theoretical and substantive knowledge of the cases and distinguish between radical‐right (= 0) and extreme‐right (= 1) collective actors on the basis of their varying allegiances to the (liberal) democratic status quo (e.g., Ellinas, Reference Ellinas2020). Radical‐right collective actors by and large abide by the rules of parliamentary democracy, whereas extreme‐right collective actors are outright anti‐democratic. Second, we account for the visibility enjoyed by each of these groups, since public exposure represents a crucial resource in contemporary media democracies (de Jonge, Reference Jonge2019). Accordingly, we used Google Trends data for an item capturing the relative visibility (Mellon, Reference Mellon2013)Footnote 12 of each far‐right collective actor included in the study (per year and country), with values ranging from 0 (no searches for a given actor) to 100 (maximum popularity) (for a similar strategy, see Andretta & Pavan, Reference Andretta, Pavan and della Porta2018). Third, we address the size of the far‐right network in which each group is embedded. We use PEA data to measure, for each collective actor, the yearly share of events in which additional actors have participated, with codes ranging from 0 (when collective actors operate in full isolation) to 1 (when actors systematically collaborate with at least another organisation). Fourth, we distinguish collective actors based on their organisational type. We differentiate between far‐right collective actors that mobilise exclusively at the grassroots level (i.e., never ran for elections: social movements = 0); actors that engage in both the protest and the electoral arena (i.e., ran for office at least once in the period 2008–2018: movement parties = 1); and actors primarily geared towards elections (i.e., consistently fielded candidates for national/European elections in the period analysed: political parties = 2). This tripartite distinction resonates with recent work on movement parties of the far right (Pirro & Castelli Gattinara, Reference Pirro and Castelli Gattinara2018) and it is based on case knowledge regarding the degree of institutionalisation of these collective actors. Fifth, we use data from the EJPR Political Data Yearbook to define the representation of each collective actor in public office, reporting on far‐right representatives in the national/European parliament through their share of MP and MEP seats each year.

Controls

As the dependent variable refers to the cumulative number of far‐right protest events, larger countries are likelier to return more protest events and get exposed to wider media attention. Therefore, the models control for population size (millions of inhabitants). To account for regional differences, the models include a dummy variable distinguishing between Central and Eastern European (as reference category) and Western European countries. These should highlight potential unobserved factors related to geographical proximity, modes of state organisation and other historical, cultural and political legacies. The descriptive statistics are reported in Annex C in the Appendix.

Explaining far‐right protest mobilisation: Grievances, opportunities and resources

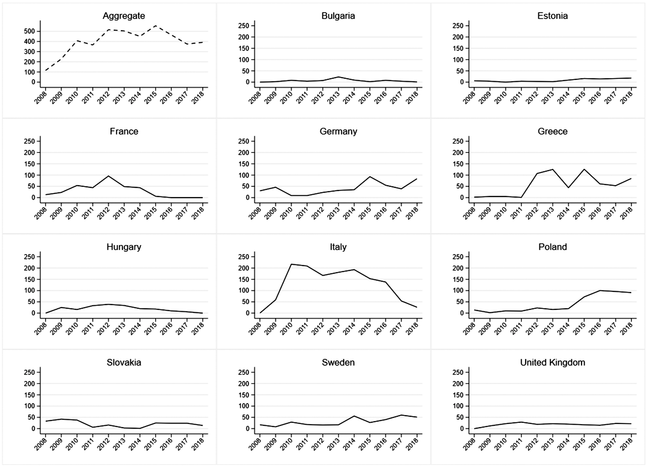

Figure 1 shows the evolution of far‐right protest mobilisation over time. Here we report the aggregate number of protest events in which the far right has partaken in the period 2008–2018, and then break down the figures by country. The aggregate graph on the top left corner shows that far‐right protest mobilisation has increased sharply between 2008 and 2013, only to decrease in 2014 and reach new heights in 2015, substantiating the guiding assumption of this article, that is, that far right protest mobilisation has increased in recent years.

Figure 1. Yearly number of far‐right protest events, by country (2008–2018).

The individual country graphs further confirm that far‐right protest mobilisation varies across time and space (Figure 1). In absolute numbers, the highest levels were recorded in Italy (an average of 98 events per year) and the lowest in Estonia (4 events per year). Some countries also experienced an increase in far‐right protest mobilisation since 2011 (e.g., France, Greece, Italy and Hungary), suggesting a possible impact of the Great Recession, others show an upward trend only after 2014 (e.g., Germany, Poland, Slovakia and Sweden), which might be linked to the crisis in the European asylum system. Since countries also vary considerably in terms of number of inhabitants, we also report per‐capita rates of far‐right protest events. The average yearly number of events per million inhabitants ranged from 4 in Greece to 0.14 in the United Kingdom. While the results do not highlight a specific pattern across Eastern and Western Europe, we control for population size and note that far‐right protest mobilisation is much higher in the former than in the latter.Footnote 13

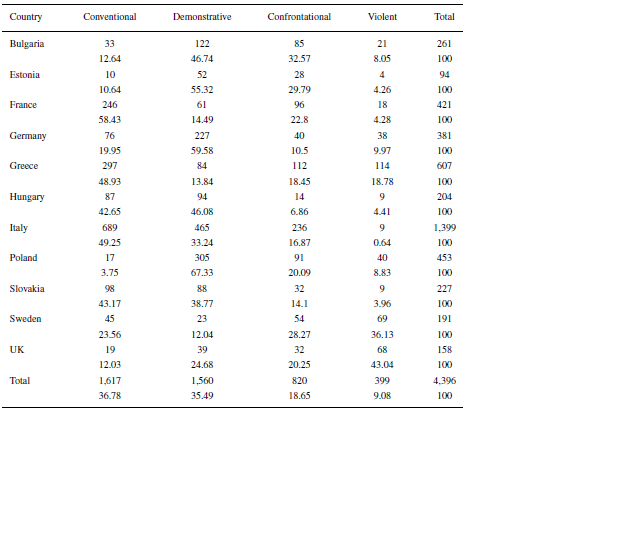

Tables 1 and 2 offer an overview of the characteristics of far‐right collective action over time, zooming in on cross‐national variation in the action repertoire and issue focus of protest. The data show that non‐electoral mobilisation by the far‐right is not limited to unlawful and violent activities. In general, most of the protests in which far‐right collective actors participate are conventional gatherings such as small public meetings and assemblies, but far‐right mobilisation also features a considerable number of confrontational actions and blockades, especially but not exclusively in Central and Eastern Europe. Even though collective actors seldom claim responsibility for unauthorised events or, worse, violent acts, these account for a large share of the events involving groups such as the Nordic Resistance Movement in Sweden and the English Defence League in the United Kingdom.

Table 1. Action repertoires in far‐right protest mobilisation across Europe (2008–2018), absolute numbers and percentages

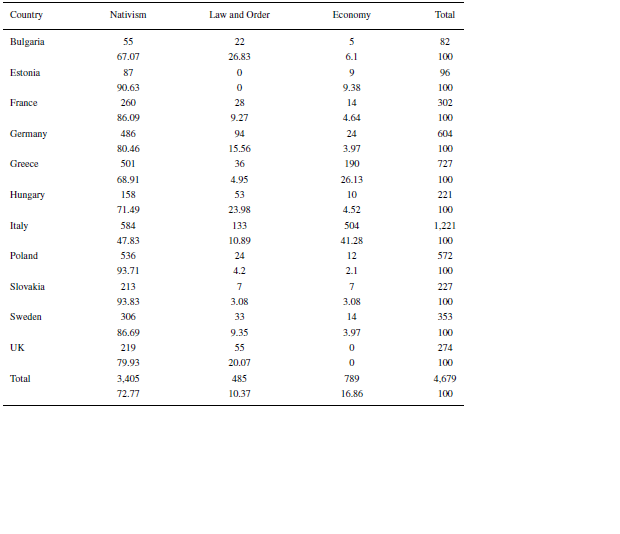

Table 2. Issue focus of far‐right protest mobilisations across Europe (2008–2018), absolute numbers and percentages

Across all countries surveyed, extra‐parliamentary activities involving far‐right collective actors focus overwhelmingly on nativist issues (i.e., migration, national identity and the presence of ethnic or religious minorities) and to a lesser extent on security and law and order. Still, in countries most affected by the Great Recession (notably, Italy and Greece), far‐right protest mobilisation also revolved around economic and welfare issues. Overall, the descriptive results show a sharp increase in far‐right protest mobilisation across Europe, a substantial variation in the repertoires of action across countries, and different issue foci somewhat indebted to contextual specificities. Far from simply increasing over time, the characteristics of far‐right protest mobilisation show distinct patterns of longitudinal and cross‐country variation,Footnote 14 confirming the opportunity to approach non‐electoral mobilisation by the far right comparatively.

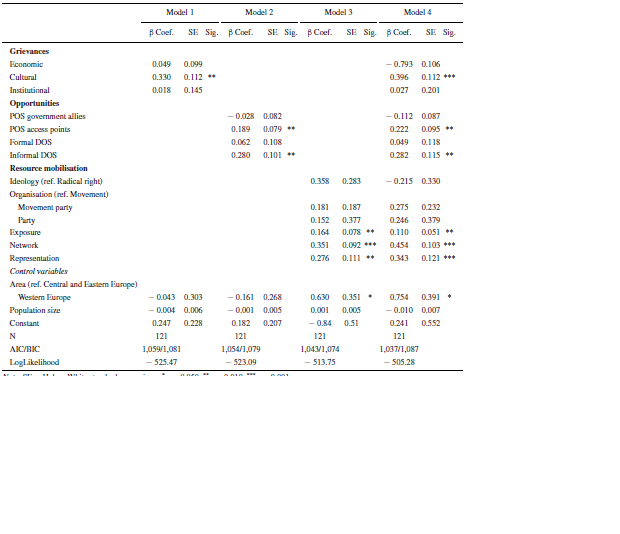

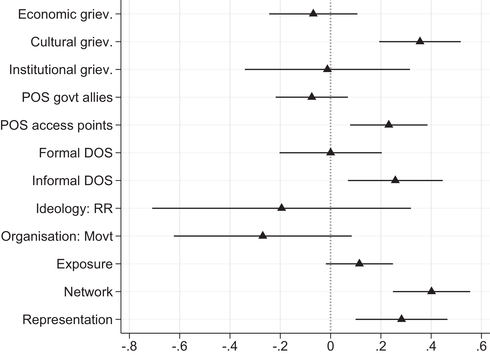

To what extent and how do country‐level grievances, political opportunities and resources account for observed differences in far‐right protest mobilisation? We ran negative binomial regression models with the number of far‐right protest events as the dependent variable. To ease the interpretation, Table 3 presents the regression results and Figure 2 the coefficient plots for the full model (Model 4). The table reports the estimates of negative binomial regression coefficients with random standard errors for each of the explanatory models (grievances, opportunities and resource mobilisation). To assess the robustness of our findings, we examine the three alternative models separately and then together as a full model (Model 4), and we use the Akaike and Bayesian information criteria (AIC‐BIC) to provide measures of model performance that account for model complexity. While both measures are penalised‐likelihood criteria, the comparison between the parsimonious models and the full model confirms that grievances, opportunities and resource mobilisation are best understood as complementary rather than competitive explanations for far‐right protest mobilisation. The results from all robustness tests (including fixed‐effects specifications and time‐invariant predictors) are included in Annex D in the Appendix. Figure 2 presents average marginal effects of a one‐unit increase in each explanatory variable on the yearly level of far‐right mobilisation. The effects of all explanatory variables are reported in standardised units.

Table 3. Impact of grievances, opportunities, and resources on far‐right protest mobilisation in Europe

Note: SE = Huber–White standard error; sig. = *p < 0.050, **p < 0.010, ***p < 0.001.

The panel structure of the data in the full model is supported by likelihood‐ratio test comparing the panel estimator with the pooled estimator. The final model includes random effects based on Hausman test. See full models using standard country fixed‐effects specification – excluding time‐invariant predictors – in the Appendix (Annex D).

Figure 2. Average marginal effects from negative binomial regression (Model 4).

Note: Coefficients and 95 per cent confidence intervals from negative binomial regression models. Standard errors clustered by country. The panel structure of the data in the full model (Model 4) is supported by likelihood‐ratio test comparing the panel estimator with the pooled estimator. Model 4 includes random effects based on Hausman test. See full models using standard country fixed‐effects specification – excluding time‐invariant predictors – in the Appendix (Annex D). The model also includes population size and country fixed effects. See the corresponding regression in the Appendix (Annex D).

We begin by considering H1a and H1c, which address the relationship between economic and institutional grievances and far‐right protest mobilisation. Models 1 and 4 in Table 3 illustrate that the economic outlook and levels of satisfaction with democracy have no discernible effect on far‐right protest mobilisation. Model 4 shows that mobilisation is lower when a country does well in economic terms, but the effect is not statistically significant, which is against our expectation for H1a. Similarly, institutional grievances (linked to subjective satisfaction with democracy) are not statistically significant for far‐right protest mobilisation, and prompt us to reject H1c. By contrast, Models 1 and 4 show that cultural grievances (linked to the inflow of migrants in the country) are associated with far‐right protest mobilisation; the association is strong and significant in the full model. In line with H1b, countries experiencing an increase in the number of migrants are significantly more likely to experience an increase in far‐right protest mobilisation. Figure 2 shows the main effects for standardised β coefficients. Holding other predictor variables constant, far‐right protest mobilisation increases by about 0.4 for a one‐unit increase in the inflow of migrants in the country. While these findings certainly owe to our dataset spanning the EU asylum policy crisis, when immigration was at the top of public agendas and citizen concernsFootnote 15, they resonate with previous research on the importance of migration in explaining support for the contemporary far right beyond all other possible sources of conflict (Halikiopoulou & Vlandas, Reference Halikiopoulou and Vlandas2020).

In order to assess the mechanisms related to the political and discursive context, we now turn to H2, expecting that far‐right protest mobilisation rests on a certain set of favourable opportunities. Let us first consider the availability of government allies, operationalised by the presence of cabinets with a right‐wing ideological orientation (H2a). Model 2 and Model 4 suggest that the effect of ideological proximity of the parties in government on far‐right protest mobilisation is negative and not significant, prompting us to reject our hypothesis. This also holds if we include interaction effects to account for differences in party competition in Eastern and Western Europe (not shown in the table). By contrast, we find that far‐right protest mobilisation increases in countries where there are institutional access points for far‐right collective actors (i.e., contexts characterised by divided government). In line with H2b, Figure 2 shows that a one‐unit increase in the degree of conflict between the executive and legislative branches is associated to an increase of about 0.2 units in far‐right protest mobilisation.

As regards discursive opportunities, we find that the presence of formal bans on extremist activity does not yield a significant effect on protest, leading us to reject H2c. High levels of counter‐mobilisation are instead positively and significantly associated with far‐right protest, but in the opposite direction than hypothesised in H2d. The far right strongly mobilises in contexts characterised by high levels of counter‐mobilisation, suggesting that far‐right protest mobilisation, and counter‐mobilisation in reaction to them, tend to feed each other. This finding echoes the patterns detected in Greece during the 2007–2016 decade, which show a strong correlation between Golden Dawn activism and antifascist mobilisation (Ellinas, Reference Ellinas2020, Ch. 9).Footnote 16

We finally turn to the mechanisms related to the resource mobilisation model, which posits that far‐right protests rest on symbolic and material resources available to collective actors (Model 3). In terms of symbolic resources, we find that ideology does not explain differences in the levels of protest mobilisation across countries: while radical‐right actors tend to mobilise more than extreme‐right ones, the difference is not statistically significant, prompting us to reject H3a. However, Models 3 and 4 demonstrate that protest mobilisation is higher when far‐right collective actors enjoy high public visibility (thus, confirming H3b) and when their initiatives involve a wide network of actors (in line with H3c). While a one‐unit growth in the exposure of far‐right collective actors is associated with an increase in protest mobilisation of 0.1, the same growth in a collective actor's network yields an increase of more than 0.4. With regard to the impact of material resources on far‐right protest mobilisation, we find no evidence of an effect of the type of organisation (i.e., political party, movement party or social movement) as posited in H3d. Essentially, the organisational type of far‐right collective actors does not seem to affect their prospects of protest mobilisation. We consider this result particularly telling insofar as neat distinctions between collective actors operating in the protest arena (social movements) and the electoral arena (political parties) are concerned. We however see a significant effect of representation in public office on far‐right protest mobilisation, indicating that the resources deriving from having MPs or MEPs elected spill over into grassroots participation (in line with H3e).

Discussion and conclusions

The article presented the first large‐scale comparative analysis of far‐right protest mobilisation. In our attempt to explain the drivers of far‐right protest mobilisation, we sought to give full prominence to a neglected aspect of nativist politics, that is, the extra‐parliamentary mobilisation of far‐right collective actors. We feel we have contributed to the literature in three ways: first, we mapped far‐right protest mobilisation in Europe, using novel data covering 11 East and West European countries, and spanning 11 years (2008‐2018); second, we bridged existing scholarship on political parties and social movements; and third, we showed that far‐right protest mobilisation rests not only on country‐level grievances and political opportunities, but also on the resources available to far‐right collective actors themselves.

We demonstrated that cross‐fertilisation between the study of social movements and far right parties is indeed a possible and fruitful endeavour, ending up refining and qualifying a number of previously held notions on the basis of our results. First, as far as grievances are concerned, far‐right protest mobilisation was strongly linked to immigration, especially in the wake of the European asylum policy crisis. This is in line with classical social movement explanations for collective action, which suggest that people protest when their expectations are not met (Gurr, Reference Gurr1970), but also with research in the field of party politics, which emphasise the importance of cultural grievances in the success of the far right (van der Brug & van Spanje, Reference Brug and Spanje2009). In this respect, we observed that objective grievances linked to the inflow of migrants in Europe are a crucial driver of far‐right protest mobilisation. Future research should complement these findings by testing for the effect of individual‐level perceptions of increasing immigration on people's propensity to participate in far‐right protest events, disentangling the differential impact of grievances across social groups, such as people in economically insecure positions and/or those with little interest in politics.

Second, political and discursive opportunities were found to affect the protest mobilisation of nativist collective actors. Protests are influenced by the political context in which they occur (Kriesi, Reference Kriesi, Porta and Diani2015). We noted that far‐right protest mobilisation is higher in contexts characterised by divided governments; in this case, the dispersion of power across representative institutions might increase prospects of access to far‐right collective actors. Regarding discursive factors, we noted a strong association between far‐right protest mobilisation and counter‐mobilisations, suggesting that the two tend to feed each other. While partly questioning whether political opponents are able to curb far‐right activism at the grassroots level, these findings call for further investigation into movement‐countermovement dynamics, and the role of societal responses to illiberal or anti‐democratic collective action (Bernhard, Reference Bernhard2020).

Third, our findings further substantiate the importance of resources for protest mobilisation. We have shown that protest mobilisation is more likely to occur when far‐right collective actors can count on symbolic resources (in the form of public visibility) and organisational‐material resources (in the form of networks of actors involved in protests as well as elected officials). This resonates not only with classical social movement theory, but also with research on the far right, which deems ‘internal supply‐side’ factors able to explain far‐right electoral success (Art, Reference Art2011; de Lange & Art, Reference Lange and Art2011). At the same time, our results essentially challenge long‐standing notions on the neat distinctions between social movements operating outside institutions and political parties active inside of them. Our findings conversely demonstrate that far‐right social movements, movement parties and political parties partake in protest mobilisations, in one way or the other, regardless of their degree of institutionalisation. We contend that these findings on the agency and the production structure of the far right are central to appreciate this phenomenon in full.

Finally, although we have distinguished between grievances, opportunities and resources for analytical clarity, we acknowledge the possible blurring of these aspects in practice. Previous research on progressive movements and the electoral performance of far‐right parties already demonstrated that the role of these factors is complex and often interrelated, and far‐right protest mobilisation is, in this sense, no exception.

While our article has been concerned with far‐right protest mobilisation in Europe, there is certainly room to develop broader comparative designs expanding our framework of analysis to better equipped far‐right collective actors and other contexts. Further enquiry should take stock of differences at the global level, and dig into the specific factors that can make far‐right protest mobilisation spill over across arenas, and transpose it from the countercultural fringes to the political mainstream, as in the cases of Donald Trump in the United States, Narendra Modi in India and Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil.

These findings have important implications for our understanding of one of the most pressing phenomena of our time. They show that far‐right protest mobilisation depends both on favourable external circumstances and on the agency of nativist collective actors. Just as several far‐right parties have thrived in periods of high volatility and decreasing turnout, far‐right movements might benefit from the growing mistrust in party politics and the opening of new arenas of contention. Recent political developments, such as the storming of the US Capitol or the spread of anti‐masks demonstrations during the COVID‐19 pandemic, confirm that we can no longer ignore the growing interpenetration between the protest and electoral arenas, and that comprehending the causes and consequences of far‐right protest mobilisation is a crucial matter for democratic quality worldwide.

Acknowledgments

Earlier drafts of this article were presented at seminars at Bocconi University, the Université Libre de Bruxelles, and the University of Siena. We would like to thank the participants to these events for the engaging discussions as well as Martín Portos and Jan Rovný for their invaluable feedback on earlier drafts of this manuscript. A special thanks goes out to Adam Fagan, Dávid Gazsi and the incredible team of research assistants involved in the Far‐Right Protest in Europe (FARPE) project: Kaidi‐Lisa Kivisalu, Måns Lundstedt, Nikolaos Saridakis, Katarzyna Ster, Eva Svatoňová and Bozhin Traykov. We finally wish to extend our gratitude to the three anonymous reviewers for their careful reading and perceptive comments on our work.

Open Access Funding provided by Scuola Normale Superiore within the CRUI‐CARE Agreement.

Funding information

This work has received funding from the Center for Research on Extremism (C‐REX), University of Oslo. Pietro Castelli Gattinara's work was supported by the Horizon 2020 ‐ Marie Skłodowska‐Curie grant agreement [883620 ‐ FARMEC project].

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Table A1. Main collective actors, newspapers and websites used for data collection

Table A2. Main collective actors included in the analysis

Table A3. Protest events by country

Table A4. Media coverage of far‐right groups in different newspapers

Table A5. Protest events by country (PolDem data vs. FARPE data, newspapers only)

Figure A1. Cross‐country and overtime distribution of protest events, PolDem data (left) and FARPE data (right)

Figure B1. Distribution of the dependent variable (mobtot)

Table B1. Test for Poisson distribution of the dependent variable (mobtot) with goodness of fit

Table B2. Likelihood‐ratio test of alpha for negative binomial distribution

Table B3. Likelihood‐ratio test on panel structure of the data (panel vs. pooled estimator)

Table C1. Descriptive statistics of dependent and independent variables

Figure C1. Cross‐national and overtime variation in counter‐mobilisation variable (yearly percentage of events facing reaction)

Figure C2. Cross‐national and overtime variation in network variable (yearly percentage of joint events)

Figure C3. Cross‐national and overtime variation in representation variable (percentage of elected officials)

Figure C4. Cross‐national and overtime variation in exposure variable (Google Trends figures)

Table D1. Poisson regression specification

Table D2. Correlation matrix

Table D3. Regression coefficients, excluding Italy (full model)

Table D4. Regression coefficients, excluding Hungary (full model)

Table D5. Regression coefficients, excluding France (full model)

Table D6. Regression coefficients, excluding Estonia (full model)

Table D7. Regression coefficients with separate items for the share of verbal/contentious reactions (full model)

Table D8. Regression coefficients controlling for migration crisis effect, excluding the year 2015 (full model)

Table D9. Regression coefficients controlling for migration crisis effect, excluding the year 2016 (full model)

Table D10. Regression coefficients controlling for migration crisis effect, excluding the years 2015 and 2016 (full model)

Table D11. Regression coefficients excluding data from websites (full model)