1 Executive summary

This letter sets out the intention to perform a first measurement of vacuum birefringence with real photons as a flagship experiment at the High Energy Density (HED)-Helmholtz International Beamline for Extreme Fields (HIBEF) instrument. Photons from the European X-ray Free Electron Laser (EuXFEL) will be scattered at regions of the quantum vacuum polarized by the optical Relativistic Laser at the XFEL (ReLaX)[ Reference Garcia, Höppner, Pelka, Bähtz, Brambrink, Di Dio Cafiso, Dreyer, Göde, Hassan, Kluge, Liu, Makita, Möller, Nakatsutsumi, Preston, Priebe, Schlenvoigt, Schwinkendorf, Šmíd, Talposi, Toncian, Zastrau, Schramm, Cowan and Toncian 1 ]. Their polarization will be measured and compared to predictions from quantum electrodynamics (QED). Counting the number of scattered photons that have flipped or not flipped their polarization allows experimental determination of the low-energy effective field theory couplings of QED, first calculated over 80 years ago[ Reference Euler and Kockel 2 – Reference Heisenberg and Euler 4 ]. Measurement of vacuum birefringence with real photons can thus be viewed as a first step on the way to harnessing the nonlinearity of the quantum vacuum.

QED predicts a self-interaction of the electromagnetic field that is mediated by virtual electron–positron pairs (some of the constituents of the ‘quantum vacuum’). This effect is purely quantum mechanical in nature: in classical electromagnetism, the electromagnetic field obeys the superposition principle. The self-interaction of the electromagnetic field has been observed in the scattering of gamma rays in the Coulomb field of atomic nuclei (Delbrück scattering)[ Reference Jarlskog, Joensson, Prünster, Schulz, Willutzki and Winter 5 , Reference Akhmadaliev, Kezerashvili, Klimenko, Malyshev, Maslennikov, Milov, Milstein, Muchnoi, Naumenkov, Panin, Peleganchuk, Popov, Pospelov, Protopopov, Romanov, Shamov, Shatilov, Simonov and Tikhonov 6 ] and more recently at the ATLAS and CMS detectors in the generation of two real photons in the collision of two Coulomb fields[ 7 – 9 ]. So-called ‘vacuum polarization’ has also been invoked to describe anomalous polarization of photons measured from strongly magnetized neutron stars[ Reference Mignani, Testa, Caniulef, Taverna, Turolla, Zane and Wu 10 ]. In addition, indirect evidence for vacuum birefringence in the modulation of pairs created via the linear Breit–Wheeler process in the STAR experiment has been noted[ Reference Brandenburg, Seger, Xu and Zha 11 ]. However, the very small cross-section makes direct probing of virtual electron–positron pairs by colliding and scattering only real photons extremely challenging and has yet to be achieved. The high number of photons available in laser beams, and the coherence of their electromagnetic fields over space–time scales much larger than that typically probed by a virtual pair, suggest that colliding focused laser pulses would be a suitable way to measure this effect. Because the leading-order process is a four-photon interaction, many signatures suggested to be probed in laser experiments are similar to those from four-wave mixing. Among others, these include manipulation of the polarization of intense laser pulses, frequency-shifting effects[ Reference McKenna and Platzman 12 – Reference Lundin, Marklund, Lundstrom, Brodin, Collier, Bingham, Mendonca and Norreys 15 ], vacuum diffraction[ Reference Di Piazza, Hatsagortsyan and Keitel 16 – Reference Tommasini and Michinel 18 ] and vacuum self-focusing[ Reference Marklund and Shukla 19 , Reference Kharzeev and Tuchin 20 ]. At the same time, any detection in laser beam collisions is challenged by separating the signal of a modified polarization, momentum or energy in the scattered photons from the large background of the laser fields.

The first direct measurement of vacuum birefringence has been envisioned as a flagship experiment for HED-HIBEF from its initial inception in 2011. HED-HIBEF combines X-rays with an optical pump beam thereby considerably increasing the cross-section, which scales with the centre-of-mass (CM) energy to the sixth power, compared to all-optical setups. High-precision X-ray polarimetry has been developed over the last decade so that it is now possible to generate a beam of X-rays that are polarized in the same state to a degree of better than one in one hundred billion[ Reference Marx-Glowna, Grabiger, Lötzsch, Uschmann, Schmitt, Schulze, Last, Roth, Antipov, Schlenvoigt, Sergueev, Leupold, Röhlsberger and Paulus 21 ]. This allows one to substantially reduce the background for those X-ray photons that scatter into the ‘flipped’ polarization mode as a signal of vacuum birefringence. At the same time the theoretical tools to make quantitatively accurate predictions of quantum vacuum signals in experimentally realistic laser fields have been advancing; see the recent review in Ref. [Reference Fedotov, Ilderton, Karbstein, King, Seipt, Taya and Torgrimsson22] and references therein. In light of these developments, we detail several experimental scenarios that can be realized by combining the EuXFEL with the optical laser ReLaX to measure the birefringence of the vacuum with real photons. One of these scenarios features the ‘dark field’ method of blocking part of the XFEL before it is focused and collides with the optical beam so that in the detector plane in the shadow, there is a region of very few background XFEL photons, which is suitable for detecting a signal[ Reference Karbstein, Ullmann, Mosman and Zepf 23 ]. The actual suppression that can be achieved with the EuXFEL beam will be determined when HED-HIBEF uses its priority access to measure background rates in 2024. In this letter we give details for the experimental implementation of this scenario. Finally, testing QED in an uncharted parameter regime can also constrain the parameter space beyond the Standard Model physics, for instance, that of weakly interacting particles with a small mass[ Reference Baker, Cantatore, Cetin, Davenport, Desch, Döbrich, Gies, Irastorza, Jaeckel, Lindner, Papaevangelou, Pivovaroff, Raffelt, Redondo, Ringwald, Semertzidis, Siemko, Sulc, Upadhye and Zioutas 24 ]. In the summary, the potential of HED-HIBEF experiments to search for new degrees of freedom is discussed.

The fundamental physics prediction of vacuum birefringence represents a prime example of a fascinating and a priori counter-intuitive phenomenon that can happen when a seemingly trivial state (‘the vacuum’) is subjected to extreme conditions (‘ultra-intense electromagnetic fields’). Its detection with state-of-the-art technology constitutes a formidable challenge and is at the edge of what is currently possible. The BIREF@HIBEF collaboration brings together experts in strong-field QED, X-ray optics, high-intensity lasers and laser–plasma physics and thus adopts an interdisciplinary approach to meeting this challenge and performing a discovery experiment.

2 Introduction

The quantum vacuum, that is, the ground state of a quantum field theory such as QED, behaves as a nonlinear, polarizable medium in reaction to strong electromagnetic fields. An electromagnetic wave probing the polarized vacuum may in turn change its polarization state as a result of vacuum birefringence. Microscopically, this is caused by the possibility of light-by-light (LbL) scattering in QED.

2.1 History and status

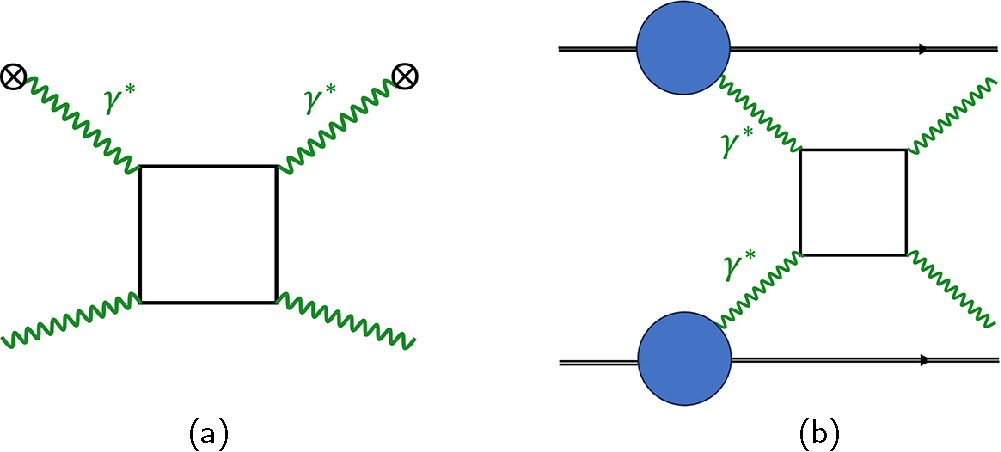

The idea of LbL scattering by now has a venerable history. According to Scharnhorst’s thorough account[ Reference Scharnhorst 25 ], its absence in the classical theory has already been stated by Kepler. In modern terms, this is explained by the linearity of Maxwell’s equations of electrodynamics entailing the superposition principle: electromagnetic field solutions can be added at will and remain solutions. In QED, the situation is different. The presence of vacuum polarization due to virtual pair fluctuations implies the existence of four-photon scattering amplitudes, as first pointed out by Halpern[ Reference Halpern 26 ] and Debye (according to Heisenberg[ Reference Heisenberg 27 ]). The presence of this amplitude, represented by the Feynman diagram in Figure 1, implies that the quantum theory becomes nonlinear and photons (self) interact through an effective four-photon vertex. This fact becomes manifest in terms of the celebrated Heisenberg–Euler (HE) Lagrangian, a low-energy effective field theory for QED[ Reference Heisenberg and Euler 4 ] discussed in more detail below.

Figure 1

![]() $O\left({\alpha}^2\right)$

Feynman diagram for the LbL scattering amplitude implying a four-photon self-interaction.

$O\left({\alpha}^2\right)$

Feynman diagram for the LbL scattering amplitude implying a four-photon self-interaction.

Heisenberg’s students Euler and Kockel did the first calculation of the LbL cross-section at low energy[ Reference Euler and Kockel 2 ], while Landau’s students Akhiezer and Pomeranchuk obtained the high-energy result[ Reference Akhiezer, Landau and Pomeranchuk 28 ]. Due to the four Lorentz indices of the amplitude, the full cross-section is somewhat tedious to work out, and it took until 1950 for a full answer to materialize[ Reference Karplus and Neuman 29 , Reference Karplus and Neuman 30 ] (see also Refs. [Reference De Tollis31,Reference De Tollis32]). Since then, the cross-section has become (advanced) textbook material[ Reference Akhiezer and Berestetskii 33 – Reference Dittrich and Gies 37 ].

As usual in QED, the cross-section for LbL scattering may be constrained via dimensional analysis. The basic QED parameters are Planck’s constant,

![]() $\mathrm{\hslash}$

, and the speed of light,

$\mathrm{\hslash}$

, and the speed of light,

![]() $c$

, which signal the unification of quantum mechanics with special relativity. Henceforth, though, we will choose natural units,

$c$

, which signal the unification of quantum mechanics with special relativity. Henceforth, though, we will choose natural units,

![]() $\mathrm{\hslash}=c=1$

, unless stated otherwise. The remaining parameters are thus the electron mass and charge,

$\mathrm{\hslash}=c=1$

, unless stated otherwise. The remaining parameters are thus the electron mass and charge,

![]() $m$

and

$m$

and

![]() $e$

, respectively. The latter defines the QED coupling strength,

$e$

, respectively. The latter defines the QED coupling strength,

![]() $\alpha ={e}^2/4\pi =1/137$

, which tells us that QED is (normally) perturbative. We may also form the typical QED length scale, given by the electron Compton wavelength,

$\alpha ={e}^2/4\pi =1/137$

, which tells us that QED is (normally) perturbative. We may also form the typical QED length scale, given by the electron Compton wavelength,

![]() ${\lambda}_{\mathrm{e}}:= 1/m \simeq 3.8\times {10}^{-13}\ \mathrm{m}$

, and the typical QED electric field magnitude,

${\lambda}_{\mathrm{e}}:= 1/m \simeq 3.8\times {10}^{-13}\ \mathrm{m}$

, and the typical QED electric field magnitude,

![]() ${E}_{\mathrm{S}}:= {m}^2/e\simeq 1.3\times {10}^{18}\kern0.1em \mathrm{V}/\mathrm{m}$

, also known as the Sauter–Schwinger limit[

Reference Sauter

38

, Reference Schwinger

39

]. Any electric field, when localized within a Compton wavelength, will contain modes above the threshold (

${E}_{\mathrm{S}}:= {m}^2/e\simeq 1.3\times {10}^{18}\kern0.1em \mathrm{V}/\mathrm{m}$

, also known as the Sauter–Schwinger limit[

Reference Sauter

38

, Reference Schwinger

39

]. Any electric field, when localized within a Compton wavelength, will contain modes above the threshold (

![]() ${q}^2>4{m}^2$

) and thus produce pairs with a probability given by a perturbative amplitude (squared)[

Reference Itzykson and Zuber

36

]. If the field magnitude exceeds the Sauter–Schwinger limit, non-perturbative, sub-threshold pair production becomes possible.

${q}^2>4{m}^2$

) and thus produce pairs with a probability given by a perturbative amplitude (squared)[

Reference Itzykson and Zuber

36

]. If the field magnitude exceeds the Sauter–Schwinger limit, non-perturbative, sub-threshold pair production becomes possible.

With the parameters defined, we return to the LbL cross-section. At low energies, the dominant energy scale is the electron mass, so the cross-section (an area) must be proportional to

![]() $1/{m}^2$

. At high energies, masses are irrelevant, and the cross-section is inversely proportional to the square of the total energy

$1/{m}^2$

. At high energies, masses are irrelevant, and the cross-section is inversely proportional to the square of the total energy

![]() ${\omega}_{\ast }$

in the CM frame,

${\omega}_{\ast }$

in the CM frame,

![]() $\sigma \sim 1/{\omega}_{\ast}^2$

. The precise results for the total unpolarized cross-section are as follows[

Reference Berestetskii, Lifshitz and Pitaevskii

35

]:

$\sigma \sim 1/{\omega}_{\ast}^2$

. The precise results for the total unpolarized cross-section are as follows[

Reference Berestetskii, Lifshitz and Pitaevskii

35

]:

The energy dependence of the cross-section is depicted in Figure 2 together with the outcome of some past experiments to be discussed below.

Figure 2 Light-by-light scattering cross-section in microbarns (

![]() ) as a function of photon energy in the centre-of-mass frame,

) as a function of photon energy in the centre-of-mass frame,

![]() ${\omega}_{\ast }$

(calculated from Refs. [Reference De Tollis31,Reference De Tollis32,Reference Costantini, De Tollis and Pistoni40]). The value of the cross-section probed by some past experiments is indicated by coloured dots ‘decorated’ by ‘laser lines’. This labelling of the processes (e.g.,

${\omega}_{\ast }$

(calculated from Refs. [Reference De Tollis31,Reference De Tollis32,Reference Costantini, De Tollis and Pistoni40]). The value of the cross-section probed by some past experiments is indicated by coloured dots ‘decorated’ by ‘laser lines’. This labelling of the processes (e.g.,

![]() $2$

-to-

$2$

-to-

![]() $2$

) refers to the number of real photons in the in and out states (see insert). The

$2$

) refers to the number of real photons in the in and out states (see insert). The

![]() $0$

-to-

$0$

-to-

![]() $2$

measurements (blue) were for a diphoton mass or more than 5 GeV (CMS[

9

]) or more than 6 GeV (ATLAS[

7

,

8

]). These are collectively represented on the plot at

$2$

measurements (blue) were for a diphoton mass or more than 5 GeV (CMS[

9

]) or more than 6 GeV (ATLAS[

7

,

8

]). These are collectively represented on the plot at

![]() ${\omega}_{\ast }/m=\sqrt{s}/2m=5\kern0.22em \mathrm{GeV}$

. The

${\omega}_{\ast }/m=\sqrt{s}/2m=5\kern0.22em \mathrm{GeV}$

. The

![]() $1$

-to-

$1$

-to-

![]() $1$

process of Delbrück scattering off nuclei measured by Jarlskog et al.

[

Reference Jarlskog, Joensson, Prünster, Schulz, Willutzki and Winter

5

] (see also Refs. [Reference Akhmadaliev, Kezerashvili, Klimenko, Malyshev, Maslennikov, Milov, Milstein, Muchnoi, Naumenkov, Panin, Peleganchuk, Popov, Pospelov, Protopopov, Romanov, Shamov, Shatilov, Simonov and Tikhonov6,Reference Schumacher, Borchert, Smend and Rullhusen41]) is shown in green. An energy range is indicated (in cyan) for HED-HIBEF assuming the near head-on collision of an optical beam with central energy

$1$

process of Delbrück scattering off nuclei measured by Jarlskog et al.

[

Reference Jarlskog, Joensson, Prünster, Schulz, Willutzki and Winter

5

] (see also Refs. [Reference Akhmadaliev, Kezerashvili, Klimenko, Malyshev, Maslennikov, Milov, Milstein, Muchnoi, Naumenkov, Panin, Peleganchuk, Popov, Pospelov, Protopopov, Romanov, Shamov, Shatilov, Simonov and Tikhonov6,Reference Schumacher, Borchert, Smend and Rullhusen41]) is shown in green. An energy range is indicated (in cyan) for HED-HIBEF assuming the near head-on collision of an optical beam with central energy

![]() $1.55\kern0.22em \mathrm{eV}$

and XFEL beam with energies between 6 and

$1.55\kern0.22em \mathrm{eV}$

and XFEL beam with energies between 6 and

![]() $12.9\kern0.22em \mathrm{keV}$

. The red cross-dots represent the

$12.9\kern0.22em \mathrm{keV}$

. The red cross-dots represent the

![]() $2$

-to-

$2$

-to-

![]() $2$

laser experiments by Moulin et al.

[

Reference Moulin, Bernard and Amiranoff

42

], Bernard et al.

[

Reference Bernard, Moulin, Amiranoff, Braun, Chambaret, Darpentigny, Grillon, Ranc and Perrone

43

] (both all-optical), Inada et al.

[

Reference Inada, Yamazaki, Yamaji, Seino, Fan, Kamioka, Namba and Asai

44

], Yamaji et al.

[

Reference Yamaji, Inada, Yamazaki, Namba, Asai, Kobayashi, Tamasaku, Tanaka, Inubushi, Sawada, Yabashi and Ishikawa

45

] (both employing an XFEL) and Watt et al.

[

Reference Watt, Kettle, Gerstmayr, King, Alejo, Astbury, Baird, Bohlen, Campbell, Colgan, Dannheim, Gregory, Harsh, Hatfield, Hinojosa, Hollatz, Katzir, Morton, Murphy, Nurnberg, Osterhoff, Pérez-Callejo, Põder, Rajeev, Roedel, Roeder, Salgado, Samarin, Sarri, Seidel, Spindloe, Steinke, Streeter, Thomas, Underwood, Wu, Zepf, Rose and Mangles

46

].

$2$

laser experiments by Moulin et al.

[

Reference Moulin, Bernard and Amiranoff

42

], Bernard et al.

[

Reference Bernard, Moulin, Amiranoff, Braun, Chambaret, Darpentigny, Grillon, Ranc and Perrone

43

] (both all-optical), Inada et al.

[

Reference Inada, Yamazaki, Yamaji, Seino, Fan, Kamioka, Namba and Asai

44

], Yamaji et al.

[

Reference Yamaji, Inada, Yamazaki, Namba, Asai, Kobayashi, Tamasaku, Tanaka, Inubushi, Sawada, Yabashi and Ishikawa

45

] (both employing an XFEL) and Watt et al.

[

Reference Watt, Kettle, Gerstmayr, King, Alejo, Astbury, Baird, Bohlen, Campbell, Colgan, Dannheim, Gregory, Harsh, Hatfield, Hinojosa, Hollatz, Katzir, Morton, Murphy, Nurnberg, Osterhoff, Pérez-Callejo, Põder, Rajeev, Roedel, Roeder, Salgado, Samarin, Sarri, Seidel, Spindloe, Steinke, Streeter, Thomas, Underwood, Wu, Zepf, Rose and Mangles

46

].

We note that the cross-section in Equation (1) is universal in the sense that it is entirely given in terms of QED parameters (

![]() $\alpha$

and

$\alpha$

and

![]() $m$

) and the Lorentz invariant kinematic factor

$m$

) and the Lorentz invariant kinematic factor

![]() $s=4{\omega}_{\ast}^2$

, the total energy (squared) in the CM frame. Thus, measuring the cross-section is indeed another experimental test of QED. The actual observable is the number

$s=4{\omega}_{\ast}^2$

, the total energy (squared) in the CM frame. Thus, measuring the cross-section is indeed another experimental test of QED. The actual observable is the number

![]() ${N}^{\prime }$

of scattered photons given by the following:

${N}^{\prime }$

of scattered photons given by the following:

where

![]() $N$

is the number of incoming (probe) photons,

$N$

is the number of incoming (probe) photons,

![]() ${n}_{\mathrm{L}}={N}_{\mathrm{L}}/V$

is the target photon density and

${n}_{\mathrm{L}}={N}_{\mathrm{L}}/V$

is the target photon density and

![]() $\Delta z$

is the target thickness, that is, the spatial extent of the probed photon distribution.

$\Delta z$

is the target thickness, that is, the spatial extent of the probed photon distribution.

At CM energies of the order of

![]() ${\omega}_{\ast}\sim m\sim 0.5\kern0.22em \mathrm{MeV}$

, the cross-section is of the order of

${\omega}_{\ast}\sim m\sim 0.5\kern0.22em \mathrm{MeV}$

, the cross-section is of the order of

![]() ${10}^{-30}\kern0.1em {\mathrm{cm}}^2$

which, although five orders of magnitude smaller than the Thomson cross-section,

${10}^{-30}\kern0.1em {\mathrm{cm}}^2$

which, although five orders of magnitude smaller than the Thomson cross-section,

![]() ${\sigma}_{\mathrm{Th}}=\left(8\pi /3\right){\alpha}^2/{m}^2$

, is not particularly small. However, in this energy regime, available photon fluxes (i.e.,

${\sigma}_{\mathrm{Th}}=\left(8\pi /3\right){\alpha}^2/{m}^2$

, is not particularly small. However, in this energy regime, available photon fluxes (i.e.,

![]() $N$

and

$N$

and

![]() ${N}_{\mathrm{L}}$

) are too small to lead to a measurable number

${N}_{\mathrm{L}}$

) are too small to lead to a measurable number

![]() ${N}^{\prime }$

of events. At low energies, the situation is reversed. For example, in the optical regime, one has large photon fluxes, but the cross-section is exceedingly small,

${N}^{\prime }$

of events. At low energies, the situation is reversed. For example, in the optical regime, one has large photon fluxes, but the cross-section is exceedingly small,

![]() $\sigma \sim {10}^{-64}\kern0.1em {\mathrm{cm}}^2$

for

$\sigma \sim {10}^{-64}\kern0.1em {\mathrm{cm}}^2$

for

![]() ${\omega}_{\ast}=1.5\kern0.22em \mathrm{eV}$

. Nevertheless, it has been suggested early on that (intense) lasers may be employed to measure this process[

Reference McKenna and Platzman

12

, Reference Kroll

47

, Reference Harutyunian, Harutyunian, Ispirian and Tumanian

48

]. The current bound on the cross-section from an all-optical scattering experiment is

${\omega}_{\ast}=1.5\kern0.22em \mathrm{eV}$

. Nevertheless, it has been suggested early on that (intense) lasers may be employed to measure this process[

Reference McKenna and Platzman

12

, Reference Kroll

47

, Reference Harutyunian, Harutyunian, Ispirian and Tumanian

48

]. The current bound on the cross-section from an all-optical scattering experiment is

![]() $\sigma <1.5\times {10}^{-48}\kern0.1em {\mathrm{cm}}^2$

at

$\sigma <1.5\times {10}^{-48}\kern0.1em {\mathrm{cm}}^2$

at

![]() ${\omega}_{\ast}=0.8\kern0.22em \mathrm{eV}$

[

Reference Bernard, Moulin, Amiranoff, Braun, Chambaret, Darpentigny, Grillon, Ranc and Perrone

43

], a considerable improvement of the earlier result[

Reference Moulin, Bernard and Amiranoff

42

]. With the advent of XFELs, the CM energy can be increased by about four orders of magnitude when colliding two XFEL beams (from

${\omega}_{\ast}=0.8\kern0.22em \mathrm{eV}$

[

Reference Bernard, Moulin, Amiranoff, Braun, Chambaret, Darpentigny, Grillon, Ranc and Perrone

43

], a considerable improvement of the earlier result[

Reference Moulin, Bernard and Amiranoff

42

]. With the advent of XFELs, the CM energy can be increased by about four orders of magnitude when colliding two XFEL beams (from

![]() $1\kern0.22em \mathrm{eV}$

to

$1\kern0.22em \mathrm{eV}$

to

![]() $10\kern0.22em \mathrm{keV}$

). Experiments at SACLA (Japan) have produced a bound of

$10\kern0.22em \mathrm{keV}$

). Experiments at SACLA (Japan) have produced a bound of

![]() $\sigma <1.9\times {10}^{-23}$

cm

$\sigma <1.9\times {10}^{-23}$

cm

![]() ${}^2$

at

${}^2$

at

![]() ${\omega}_{\ast}=6.5\kern0.22em \mathrm{keV}$

[

Reference Yamaji, Inada, Yamazaki, Namba, Asai, Kobayashi, Tamasaku, Tanaka, Inubushi, Sawada, Yabashi and Ishikawa

45

]. At this energy, the QED prediction is

${\omega}_{\ast}=6.5\kern0.22em \mathrm{keV}$

[

Reference Yamaji, Inada, Yamazaki, Namba, Asai, Kobayashi, Tamasaku, Tanaka, Inubushi, Sawada, Yabashi and Ishikawa

45

]. At this energy, the QED prediction is

![]() $2.5\times {10}^{-43}\kern0.1em {\mathrm{cm}}^2$

. So, both experiments are off the QED value by about 20 orders of magnitude; see Table 1. For comparison, we note that the cross-section for neutrino electron scattering (for neutrino energies of

$2.5\times {10}^{-43}\kern0.1em {\mathrm{cm}}^2$

. So, both experiments are off the QED value by about 20 orders of magnitude; see Table 1. For comparison, we note that the cross-section for neutrino electron scattering (for neutrino energies of

![]() ${10}^2\kern0.1em \mathrm{eV}$

) is about

${10}^2\kern0.1em \mathrm{eV}$

) is about

![]() ${10}^{-58}\kern0.1em {\mathrm{cm}}^2$

and has not been measured yet[

Reference Formaggio and Zeller

49

].

${10}^{-58}\kern0.1em {\mathrm{cm}}^2$

and has not been measured yet[

Reference Formaggio and Zeller

49

].

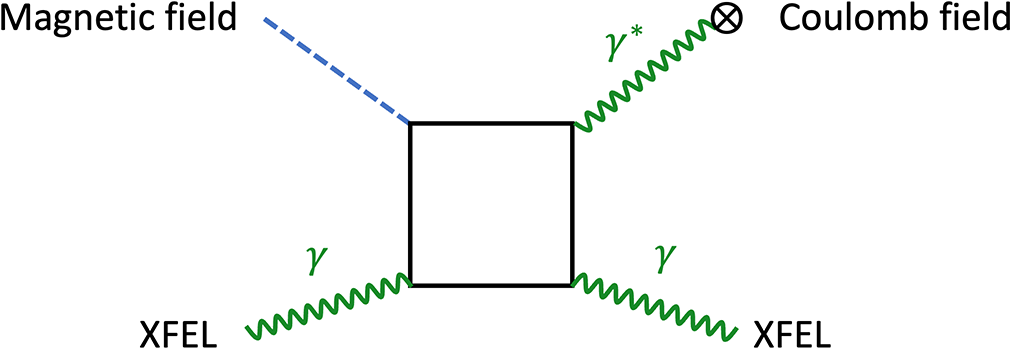

Table 1 Experimental bounds obtained for the LbL scattering cross-section and QED predictions (in historical order). The last row refers to the experiment proposed in this Letter of Intent, which aims to reach the sensitivity for the QED value stated.

Figure 2 also shows some experiments at high energy,

![]() ${\omega}_{\ast}\gtrsim m$

. These have actually observed variants of Delbrück scattering[

Reference Delbrück

50

] where photons couple to nuclear Coulomb fields. This may be realized by scattering photons off nuclei (charge

${\omega}_{\ast}\gtrsim m$

. These have actually observed variants of Delbrück scattering[

Reference Delbrück

50

] where photons couple to nuclear Coulomb fields. This may be realized by scattering photons off nuclei (charge

![]() $Ze$

) (Figure 3(a)) or via ultra-peripheral heavy-ion collisions (Figure 3(b)). In either case, the two intermediate photons are virtual, with their four-momentum

$Ze$

) (Figure 3(a)) or via ultra-peripheral heavy-ion collisions (Figure 3(b)). In either case, the two intermediate photons are virtual, with their four-momentum

![]() $q$

off-shell,

$q$

off-shell,

![]() ${q}^2\ne 0$

. Counting vertices and dimensions, the cross-section for

${q}^2\ne 0$

. Counting vertices and dimensions, the cross-section for

![]() ${\omega}_{\ast }<m$

can be estimated as follows[

Reference Berestetskii, Lifshitz and Pitaevskii

35

]:

${\omega}_{\ast }<m$

can be estimated as follows[

Reference Berestetskii, Lifshitz and Pitaevskii

35

]:

This yields an increase compared to LbL; recall Equation (1), if

![]() ${Z}^2\alpha >{\omega}_{\ast }/m$

, which is easily achieved for

${Z}^2\alpha >{\omega}_{\ast }/m$

, which is easily achieved for

![]() ${\omega}_{\ast }<m$

. In particular, the nuclear charge can be viewed as a coherent enhancement factor, which is also present at larger energies,

${\omega}_{\ast }<m$

. In particular, the nuclear charge can be viewed as a coherent enhancement factor, which is also present at larger energies,

![]() ${\omega}_{\ast }>m$

[

Reference Berestetskii, Lifshitz and Pitaevskii

35

]. As a result, the Delbrück processes of Figure 3 have indeed been measured, both for nuclei at rest (Figure 2, green dots[

Reference Jarlskog, Joensson, Prünster, Schulz, Willutzki and Winter

5

, Reference Akhmadaliev, Kezerashvili, Klimenko, Malyshev, Maslennikov, Milov, Milstein, Muchnoi, Naumenkov, Panin, Peleganchuk, Popov, Pospelov, Protopopov, Romanov, Shamov, Shatilov, Simonov and Tikhonov

6

, Reference Schumacher, Borchert, Smend and Rullhusen

41

]) and in heavy-ion collisions (Figure 2, blue dots[

7

–

9

]). Figure 2 clearly shows that the Delbrück cross-section exceeds the LbL one – by at least five orders of magnitude for

${\omega}_{\ast }>m$

[

Reference Berestetskii, Lifshitz and Pitaevskii

35

]. As a result, the Delbrück processes of Figure 3 have indeed been measured, both for nuclei at rest (Figure 2, green dots[

Reference Jarlskog, Joensson, Prünster, Schulz, Willutzki and Winter

5

, Reference Akhmadaliev, Kezerashvili, Klimenko, Malyshev, Maslennikov, Milov, Milstein, Muchnoi, Naumenkov, Panin, Peleganchuk, Popov, Pospelov, Protopopov, Romanov, Shamov, Shatilov, Simonov and Tikhonov

6

, Reference Schumacher, Borchert, Smend and Rullhusen

41

]) and in heavy-ion collisions (Figure 2, blue dots[

7

–

9

]). Figure 2 clearly shows that the Delbrück cross-section exceeds the LbL one – by at least five orders of magnitude for

![]() ${\omega}_{\ast}\gg m$

. For additional details we refer to the overview presented in the introduction of Ref. [Reference Ahmadiniaz, Lopez-Arcos, Lopez-Lopez and Schubert51].

${\omega}_{\ast}\gg m$

. For additional details we refer to the overview presented in the introduction of Ref. [Reference Ahmadiniaz, Lopez-Arcos, Lopez-Lopez and Schubert51].

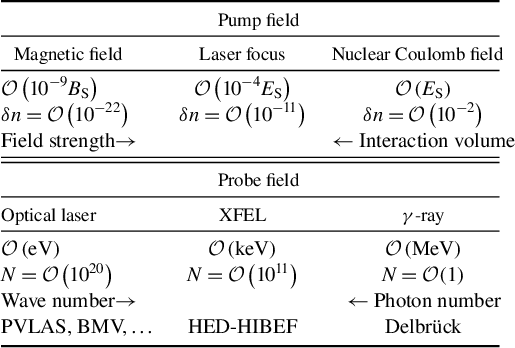

Figure 3 Two variants of Delbrück scattering involving two virtual photons,

![]() ${\gamma}^{\ast }$

. (a) Off a (static) Coulomb potential denoted by crosses. (b) Off a Lorentz boosted Coulomb potential in ultra-peripheral heavy-ion collisions.

${\gamma}^{\ast }$

. (a) Off a (static) Coulomb potential denoted by crosses. (b) Off a Lorentz boosted Coulomb potential in ultra-peripheral heavy-ion collisions.

2.2 Light-by-light scattering with lasers

At BIREF@HIBEF an intense optical laser (

![]() ${\omega}_{\mathrm{L}}=1.55\;\mathrm{eV}$

) will be combined with the EuXFEL (which can run at different frequencies from about

${\omega}_{\mathrm{L}}=1.55\;\mathrm{eV}$

) will be combined with the EuXFEL (which can run at different frequencies from about

![]() $5$

to

$5$

to

![]() $24\;\mathrm{keV}$

, e.g., at

$24\;\mathrm{keV}$

, e.g., at

![]() ${\omega}_{\mathrm{X}}=8766\;\mathrm{eV}$

). This implies a CM energy given by the geometric mean of

${\omega}_{\mathrm{X}}=8766\;\mathrm{eV}$

). This implies a CM energy given by the geometric mean of

![]() ${\omega}_{\ast}={\left({\omega}_{\mathrm{L}}{\omega}_{\mathrm{X}}\right)}^{1/2}=116\;\mathrm{eV}$

. According to Equation (1), the QED cross-section will then be

${\omega}_{\ast}={\left({\omega}_{\mathrm{L}}{\omega}_{\mathrm{X}}\right)}^{1/2}=116\;\mathrm{eV}$

. According to Equation (1), the QED cross-section will then be

![]() $\sigma =1.81\times {10}^{-53}\;{\mathrm{cm}}^2$

. This is still fairly small, but the coherence of the optical laser background drastically enhances the amplitude by a factor proportional to the photon number.

$\sigma =1.81\times {10}^{-53}\;{\mathrm{cm}}^2$

. This is still fairly small, but the coherence of the optical laser background drastically enhances the amplitude by a factor proportional to the photon number.

The calculation of the relevant cross-section thus proceeds in two steps. Firstly, one employs a low-energy approximation by adopting the HE effective Lagrangian with a point-like four-photon vertex. Intuitively, the vacuum polarization loop can no longer be resolved as the effective theory is only valid for distances much larger than the Compton wave length. In a second step, one replaces two of the photon legs in Figure 1 by an external electromagnetic field representing the intense laser focus. The two steps are depicted in terms of Feynman diagrams in Figure 4.

Figure 4 Two-step modification of the QED 4-photon vertex (left) to the Heisenberg–Euler four-point interaction (centre) and coupling to an external field scattering (right).

Scattering off an optical laser background

![]() $F$

yields a coherent enhancement factor

$F$

yields a coherent enhancement factor

![]() ${F}^2$

in the amplitude. This factor is proportional to the photon number

${F}^2$

in the amplitude. This factor is proportional to the photon number

![]() ${N}_{\mathrm{L}}$

of the optical laser, hence analogous to the squared nuclear charge,

${N}_{\mathrm{L}}$

of the optical laser, hence analogous to the squared nuclear charge,

![]() ${Z}^2$

, in Delbrück scattering. Thus, replacing

${Z}^2$

, in Delbrück scattering. Thus, replacing

![]() ${Z}^2$

with

${Z}^2$

with

![]() ${F}^2\sim {N}_{\mathrm{L}}$

in Equation (4), the cross-section is expected to behave as follows:

${F}^2\sim {N}_{\mathrm{L}}$

in Equation (4), the cross-section is expected to behave as follows:

The dimensionless constant of proportionality can be calculated from the low-energy effective field theory of QED:

where

![]() ${\mathrm{\mathcal{L}}}_{\mathrm{HE}}$

is the celebrated HE Lagrangian[

Reference Heisenberg and Euler

4

] to the lowest order in field strengths. Its crucial ingredients are the fundamental Lorentz and gauge invariants:

${\mathrm{\mathcal{L}}}_{\mathrm{HE}}$

is the celebrated HE Lagrangian[

Reference Heisenberg and Euler

4

] to the lowest order in field strengths. Its crucial ingredients are the fundamental Lorentz and gauge invariants:

with the electromagnetic field strength tensor

![]() ${F}^{\mu \nu}={\partial}^{\mu }{A}^{\nu }-{\partial}^{\nu }{A}^{\mu }$

and its dual,

${F}^{\mu \nu}={\partial}^{\mu }{A}^{\nu }-{\partial}^{\nu }{A}^{\mu }$

and its dual,

![]() ${\tilde{F}}^{\mu}=\left(1/2\right){\varepsilon}^{\mu \nu \rho \sigma}{F}_{\rho \sigma}$

, gauge potential

${\tilde{F}}^{\mu}=\left(1/2\right){\varepsilon}^{\mu \nu \rho \sigma}{F}_{\rho \sigma}$

, gauge potential

![]() ${A}^{\mu }$

and low-energy constants

${A}^{\mu }$

and low-energy constants

![]() ${c}_1$

,

${c}_1$

,

![]() ${c}_2$

and

${c}_2$

and

![]() ${c}_{22}$

. The invariant

${c}_{22}$

. The invariant

![]() $\mathcal{S}$

is just the Maxwell Lagrangian, while

$\mathcal{S}$

is just the Maxwell Lagrangian, while

![]() ${\mathcal{S}}^2$

and

${\mathcal{S}}^2$

and

![]() ${\mathcal{P}}^2$

are the leading-order nonlinear corrections first employed in Ref. [Reference Euler and Kockel2]. The ellipsis represents corrections of higher order in both field strength[

Reference Heisenberg and Euler

4

] and derivatives[

Reference Mamaev, Mostepanenko and Eides

52

–

Reference Franchino-Viñas, García-Pérez, Mazzitelli, Vitagliano and Haimovichi

56

]. The low-energy constants are as follows:

${\mathcal{P}}^2$

are the leading-order nonlinear corrections first employed in Ref. [Reference Euler and Kockel2]. The ellipsis represents corrections of higher order in both field strength[

Reference Heisenberg and Euler

4

] and derivatives[

Reference Mamaev, Mostepanenko and Eides

52

–

Reference Franchino-Viñas, García-Pérez, Mazzitelli, Vitagliano and Haimovichi

56

]. The low-energy constants are as follows:

where the powers in

![]() $\alpha$

and

$\alpha$

and

![]() $m$

follow from vertex counting and dimensional analysis. These coefficients receive higher loop corrections that are parametrically suppressed with additional powers of

$m$

follow from vertex counting and dimensional analysis. These coefficients receive higher loop corrections that are parametrically suppressed with additional powers of

![]() $\alpha \ll 1$

. They account for higher-order vacuum polarization effects arising from the interaction of charges in the vacuum polarization loop; cf., for example, Ref. [Reference Gies and Karbstein57].

$\alpha \ll 1$

. They account for higher-order vacuum polarization effects arising from the interaction of charges in the vacuum polarization loop; cf., for example, Ref. [Reference Gies and Karbstein57].

In this context, we also emphasize that the structure of Equation (6) is generic for any nonlinear extension of classical electrodynamics that respects Lorentz covariance, U(1) gauge invariance and a charge conjugation parity symmetry. Hence, a measurement of the QED predictions in Equation (9) inherently also implies a restriction of the parameter space of other potential nonlinear extensions of classical electrodynamics in and beyond the Standard Model of particle physics.

In QED, the last constant,

![]() ${c}_{22}$

, is the weight of the leading-order linear vacuum polarization term and was already calculated by Dirac[

Reference Dirac

58

] and Heisenberg[

Reference Heisenberg

27

] in 1934. Its QED analogue, valid for all energies, implies a scale dependence, hence ‘running’, of the electric charge, which decreases with distance. Intuitively, this corresponds to charge screening caused by the virtual pair dipoles in the vacuum. This implies in turn that the vacuum can be viewed as a polarizable medium with both linear and nonlinear response to an external field. The associated response functions are given by the second derivatives of the effective Lagrangian with respect to

${c}_{22}$

, is the weight of the leading-order linear vacuum polarization term and was already calculated by Dirac[

Reference Dirac

58

] and Heisenberg[

Reference Heisenberg

27

] in 1934. Its QED analogue, valid for all energies, implies a scale dependence, hence ‘running’, of the electric charge, which decreases with distance. Intuitively, this corresponds to charge screening caused by the virtual pair dipoles in the vacuum. This implies in turn that the vacuum can be viewed as a polarizable medium with both linear and nonlinear response to an external field. The associated response functions are given by the second derivatives of the effective Lagrangian with respect to

![]() $F$

(or

$F$

(or

![]() $\mathbf{E}$

and

$\mathbf{E}$

and

![]() $\mathbf{B}$

). Focusing on the nonlinear case we can define macroscopic fields

$\mathbf{B}$

). Focusing on the nonlinear case we can define macroscopic fields

![]() $\mathbf{D}$

and

$\mathbf{D}$

and

![]() $\mathbf{H}$

as the derivatives of the Lagrangian

$\mathbf{H}$

as the derivatives of the Lagrangian

![]() ${\mathrm{\mathcal{L}}}_{\mathrm{eff}}=\mathcal{S}+{\mathrm{\mathcal{L}}}_{\mathrm{HE}}$

:

${\mathrm{\mathcal{L}}}_{\mathrm{eff}}=\mathcal{S}+{\mathrm{\mathcal{L}}}_{\mathrm{HE}}$

:

where the (static) nonlinear response functions are the tensors[ Reference Baier and Breitenlohner 59 ]:

These correspond to the dielectric and permeability tensors, respectively, and thus explicitly show the electric and magnetic response of the vacuum to external fields. In the words of Weisskopf[ Reference Weisskopf and Dan 60 ]: ‘When passing through electromagnetic fields, light will behave as if the vacuum had acquired a dielectric constant different from unity due to the influence of the fields.

From conventional optics, it is known that media with dielectric constant

![]() $\varepsilon$

and permeability

$\varepsilon$

and permeability

![]() $\mu$

have optical properties characterized by an index of refraction,

$\mu$

have optical properties characterized by an index of refraction,

![]() $n\equiv \sqrt{\varepsilon \mu}$

. In view of Equations (12) and (13) it must thus be possible to ascribe a nontrivial refractive index to the vacuum. This can indeed be done by studying the eigenvalues of the dielectric and permeability tensors,

$n\equiv \sqrt{\varepsilon \mu}$

. In view of Equations (12) and (13) it must thus be possible to ascribe a nontrivial refractive index to the vacuum. This can indeed be done by studying the eigenvalues of the dielectric and permeability tensors,

![]() ${\varepsilon}_{ij}$

and

${\varepsilon}_{ij}$

and

![]() ${\mu}_{ij}$

[

Reference Dittrich and Gies

37

, Reference Klein and Nigam

61

, Reference Koch

62

]. One finds that the vacuum is characterized by two nontrivial refractive indices,

${\mu}_{ij}$

[

Reference Dittrich and Gies

37

, Reference Klein and Nigam

61

, Reference Koch

62

]. One finds that the vacuum is characterized by two nontrivial refractive indices,

![]() ${n}_1$

and

${n}_1$

and

![]() ${n}_2$

, so that the vacuum acts like a birefringent medium.

${n}_2$

, so that the vacuum acts like a birefringent medium.

2.3 Vacuum birefringence

A web search for the term ‘vacuum birefringence’ dates its first appearance to the year 1964 when it appeared in the title of a paper by Klein and Nigam[ Reference Klein and Nigam 61 ] who employed the tensors in Equations (12) and (13) stemming from the low-energy HE Lagrangian. However, the vacuum refractive indices were first calculated (for arbitrary photon energies) by Toll in his unpublished PhD thesis[ Reference Toll 63 ] supervised by Wheeler. Other early and important contributions have been made by Erber[ Reference Erber 64 ] (preceding Klein and Nigam), Baier and Breitenlohner[ Reference Baier and Breitenlohner 59 ] and Narozhny[ Reference Narozhny 65 ]. The utilization of lasers was first suggested and analysed in Ref. [Reference Aleksandrov, Ansel’m and Moskalev66]. The HED-HIBEF experiment is based on the optimal scenario of combining an XFEL probe beam with an intense optical laser background. This was first suggested in Ref. [Reference Heinzl, Liesfeld, Amthor, Schwoerer, Sauerbrey and Wipf67].

To avoid confusion we recall that the term ‘vacuum birefringence’ refers to the refractive or dispersive properties of the vacuum (encoded in the real part of the refractive indices), while the term ‘vacuum dichroism’ describes its absorptive properties (encoded in the imaginary part of the refractive indices). In other words, dichroism amounts to a direction dependent absorption of probe photons, hence a reduction of probe intensity[ Reference Klein and Nigam 68 , Reference Heyl and Hernquist 69 ].

A quick way to derive the magnitude of the birefringence effect is to employ the differential cross-section in the CM frame, which for a

![]() $2\to 2$

process (with all masses equal) has the following universal form:

$2\to 2$

process (with all masses equal) has the following universal form:

Here

![]() $\mathfrak{M}$

is the invariant amplitude depending on photon polarizations and momenta while

$\mathfrak{M}$

is the invariant amplitude depending on photon polarizations and momenta while

![]() $f$

is the scattering amplitude for momentum transfer,

$f$

is the scattering amplitude for momentum transfer,

![]() $\mathbf{l}\to {\mathbf{l}}^{\prime }$

, and scattering angle

$\mathbf{l}\to {\mathbf{l}}^{\prime }$

, and scattering angle

![]() $\theta$

. Microscopically, vacuum birefringence corresponds to forward scattering (

$\theta$

. Microscopically, vacuum birefringence corresponds to forward scattering (

![]() $\mathbf{l}={\mathbf{l}}^{\prime }$

,

$\mathbf{l}={\mathbf{l}}^{\prime }$

,

![]() $\theta =0$

) with a polarization flip of a probe photon passing through an intense laser background. We thus assume the involvement of two laser photons with the same polarizations and four vectors, while the probe polarization flips,

$\theta =0$

) with a polarization flip of a probe photon passing through an intense laser background. We thus assume the involvement of two laser photons with the same polarizations and four vectors, while the probe polarization flips,

![]() $\varepsilon \to {\varepsilon}^{\prime }$

with

$\varepsilon \to {\varepsilon}^{\prime }$

with

![]() $\varepsilon \cdot {\varepsilon}^{\prime}=0$

. Choosing the optimal scenario of a 45° angle between probe and laser polarizations, one may use the textbook formulae in Ref. [Reference Akhiezer and Berestetskii33] to find the forward-flip amplitude

$\varepsilon \cdot {\varepsilon}^{\prime}=0$

. Choosing the optimal scenario of a 45° angle between probe and laser polarizations, one may use the textbook formulae in Ref. [Reference Akhiezer and Berestetskii33] to find the forward-flip amplitude

![]() $\mathfrak{M}(0)$

and hence the forward-scattering amplitude:

$\mathfrak{M}(0)$

and hence the forward-scattering amplitude:

$$\begin{align}f\left(\mathbf{l},\mathbf{l},0\right)\equiv f(0)=\frac{\mathfrak{M}(0)}{8\pi \sqrt{s}}=\frac{4{\alpha}^2}{15\pi }{\left(\frac{\omega_{\ast }}{m}\right)}^3\frac{1}{m}. \end{align}$$

$$\begin{align}f\left(\mathbf{l},\mathbf{l},0\right)\equiv f(0)=\frac{\mathfrak{M}(0)}{8\pi \sqrt{s}}=\frac{4{\alpha}^2}{15\pi }{\left(\frac{\omega_{\ast }}{m}\right)}^3\frac{1}{m}. \end{align}$$

Another textbook formula (see e.g., Ref. [Reference Newton70], Chap. 1.5) relates the index of refraction to the forward-scattering amplitude. The flip amplitude, in particular, defines the difference of the vacuum refractive indices:

$$\begin{align}\Delta n=\frac{2\pi {n}_{\mathrm{L}}}{\omega_{\ast}^2}f(0)=\frac{8{\alpha}^2}{15}\frac{I_{\mathrm{L}}}{m^4}.\end{align}$$

$$\begin{align}\Delta n=\frac{2\pi {n}_{\mathrm{L}}}{\omega_{\ast}^2}f(0)=\frac{8{\alpha}^2}{15}\frac{I_{\mathrm{L}}}{m^4}.\end{align}$$

Here we have used that the laser photon density,

![]() ${n}_{\mathrm{L}}={N}_{\mathrm{L}}/V={I}_{\mathrm{L}}/{\omega}_{\ast }$

, is proportional to intensity,

${n}_{\mathrm{L}}={N}_{\mathrm{L}}/V={I}_{\mathrm{L}}/{\omega}_{\ast }$

, is proportional to intensity,

![]() ${I}_{\mathrm{L}}$

, measured in the CM system. This result is consistent with the intensity scaling that led to Equation (5) and the calculation[

Reference Narozhny

65

] of the refractive indices in terms of the vacuum polarization tensor (the covariant unification of dielectric and permeability tensors):

${I}_{\mathrm{L}}$

, measured in the CM system. This result is consistent with the intensity scaling that led to Equation (5) and the calculation[

Reference Narozhny

65

] of the refractive indices in terms of the vacuum polarization tensor (the covariant unification of dielectric and permeability tensors):

This may be written in a more covariant way as follows. One introduces the probe four-vector

![]() $k=\omega \mathrm{\ell}$

with frequency

$k=\omega \mathrm{\ell}$

with frequency

![]() $\omega$

and a dimensionless null-vector

$\omega$

and a dimensionless null-vector

![]() $\mathrm{\ell}$

,

$\mathrm{\ell}$

,

![]() ${\mathrm{\ell}}^2=0$

. One then forms the ‘null-energy projection’[

Reference Shore

71

],

${\mathrm{\ell}}^2=0$

. One then forms the ‘null-energy projection’[

Reference Shore

71

],

![]() ${T}_{\mathrm{\ell \ell }}\equiv {\mathrm{\ell}}_{\mu }{T}^{\mu \nu}{\mathrm{\ell}}_{\nu }$

, of the Maxwell energy-momentum tensor,

${T}_{\mathrm{\ell \ell }}\equiv {\mathrm{\ell}}_{\mu }{T}^{\mu \nu}{\mathrm{\ell}}_{\nu }$

, of the Maxwell energy-momentum tensor,

![]() ${T}^{\mu \nu}={F}^{\mu \alpha}{F}_{\alpha}^{\nu }-{g}^{\mu \nu}\mathcal{S}$

, the traceless part of the squared field strength. For any field configuration,

${T}^{\mu \nu}={F}^{\mu \alpha}{F}_{\alpha}^{\nu }-{g}^{\mu \nu}\mathcal{S}$

, the traceless part of the squared field strength. For any field configuration,

![]() ${F}^{\mu \nu}$

, one can thus write the following:

${F}^{\mu \nu}$

, one can thus write the following:

$$\begin{align}\frac{\Delta n}{T_{\mathrm{\ell \ell }}}={c}_2-{c}_1=\frac{2{\alpha}^2}{15{m}^4},\end{align}$$

$$\begin{align}\frac{\Delta n}{T_{\mathrm{\ell \ell }}}={c}_2-{c}_1=\frac{2{\alpha}^2}{15{m}^4},\end{align}$$

which obviously just measures the difference of the leading-order low-energy constants in the HE Lagrangian. The difference

![]() $\Delta n$

in refractive indices induces an ellipticity

$\Delta n$

in refractive indices induces an ellipticity

![]() $\delta \equiv {k}_{\mathrm{X}}z\Delta n/2$

for a linearly polarized probe beam of wave number

$\delta \equiv {k}_{\mathrm{X}}z\Delta n/2$

for a linearly polarized probe beam of wave number

![]() ${k}_{\mathrm{X}}$

traversing the polarized vacuum across a distance

${k}_{\mathrm{X}}$

traversing the polarized vacuum across a distance

![]() $z$

. The experimental signature is then the flip probability:

$z$

. The experimental signature is then the flip probability:

with the Sauter–Schwinger intensity

![]() ${I}_{\mathrm{S}}={E}_{\mathrm{S}}^2={m}^4/4\pi \alpha =4.7\times {10}^{29}\kern0.1em \mathrm{W}/{\mathrm{cm}}^2$

. Equation (19) shows explicitly that an optimal scenario will maximize the target intensity

${I}_{\mathrm{S}}={E}_{\mathrm{S}}^2={m}^4/4\pi \alpha =4.7\times {10}^{29}\kern0.1em \mathrm{W}/{\mathrm{cm}}^2$

. Equation (19) shows explicitly that an optimal scenario will maximize the target intensity

![]() ${I}_{\mathrm{L}}$

and its spatial extent,

${I}_{\mathrm{L}}$

and its spatial extent,

![]() $z$

, while simultaneously minimizing the (reduced) probe wave length,

$z$

, while simultaneously minimizing the (reduced) probe wave length, ![]() [

Reference Heinzl, Liesfeld, Amthor, Schwoerer, Sauerbrey and Wipf

67

]. At HED-HIBEF this is realized by combining a high-intensity optical laser with an XFEL. A rough estimate with

[

Reference Heinzl, Liesfeld, Amthor, Schwoerer, Sauerbrey and Wipf

67

]. At HED-HIBEF this is realized by combining a high-intensity optical laser with an XFEL. A rough estimate with

![]() ${I}_{\mathrm{L}}={10}^{21}\kern0.1em \mathrm{W}/{\mathrm{cm}}^2$

,

${I}_{\mathrm{L}}={10}^{21}\kern0.1em \mathrm{W}/{\mathrm{cm}}^2$

,

![]() $z=10\;\unicode{x3bc} \mathrm{m}$

and

$z=10\;\unicode{x3bc} \mathrm{m}$

and ![]() (for

(for

![]() ${\omega}_{\mathrm{X}}=10\kern0.22em \mathrm{keV}$

) yields

${\omega}_{\mathrm{X}}=10\kern0.22em \mathrm{keV}$

) yields

![]() ${N}^{\prime }/N\approx {10}^{-12}$

. Obviously, such a minuscule flip probability demands a very high accuracy of the required polarization measurements. Indeed, the original suggestion to employ XFEL beams as a probe[

Reference Heinzl, Liesfeld, Amthor, Schwoerer, Sauerbrey and Wipf

67

] has been an incentive to improve the polarization purity of X-rays by several orders of magnitude to a current record of

${N}^{\prime }/N\approx {10}^{-12}$

. Obviously, such a minuscule flip probability demands a very high accuracy of the required polarization measurements. Indeed, the original suggestion to employ XFEL beams as a probe[

Reference Heinzl, Liesfeld, Amthor, Schwoerer, Sauerbrey and Wipf

67

] has been an incentive to improve the polarization purity of X-rays by several orders of magnitude to a current record of

![]() ${10}^{-11}$

[

Reference Schulze, Grabiger, Loetzsch, Marx-Glowna, Schmitt, Garcia, Hippler, Huang, Karbstein, Konôpková, Schlenvoigt, Schwinkendorf, Strohm, Toncian, Uschmann, Wille, Zastrau, Röhlsberger, Stöhlker, Cowan and Paulus

72

]. A topical review of the technical difficulties involved and how they are being addressed is given in Ref. [Reference Yu, Xu, Shen, Cowan and Schlenvoigt73].

${10}^{-11}$

[

Reference Schulze, Grabiger, Loetzsch, Marx-Glowna, Schmitt, Garcia, Hippler, Huang, Karbstein, Konôpková, Schlenvoigt, Schwinkendorf, Strohm, Toncian, Uschmann, Wille, Zastrau, Röhlsberger, Stöhlker, Cowan and Paulus

72

]. A topical review of the technical difficulties involved and how they are being addressed is given in Ref. [Reference Yu, Xu, Shen, Cowan and Schlenvoigt73].

2.4 Previous experiments

As early as 1929, Watson[

Reference Watson

74

] tried to measure a vacuum refractive index

![]() $n$

depending linearly on a static magnetic field,

$n$

depending linearly on a static magnetic field,

![]() $B$

. He used an interferometer to measure a small induced frequency shift, but did not find any effect and thus produced the upper bound of

$B$

. He used an interferometer to measure a small induced frequency shift, but did not find any effect and thus produced the upper bound of

![]() $\left(n-1\right)/B<4\times {10}^{-7}\kern0.1em {\mathrm{T}}^{-1}$

(in modern notation). In 1960 Jones[

Reference Jones

75

] measured the velocity of light in a magnetic field to high precision and found no deviation from its vacuum value. A year later, Erber[

Reference Erber

64

] discussed a number of settings (including Watson’s) that might allow measurement of a quadratic dependence of the vacuum refractive indices, hence a Cotton–Mouton effect[

Reference Cotton and Mouton

76

, Reference Cotton and Mouton

77

], as predicted by QED. Klein and Nigam[

Reference Klein and Nigam

61

] suggested using a static electric field inside a plane capacitor, but ruled the birefringence effect to be way too small. In 1979, Iacopini and Zavattini pointed out that one may use strong static magnetic fields and optimize the geometric factor

$\left(n-1\right)/B<4\times {10}^{-7}\kern0.1em {\mathrm{T}}^{-1}$

(in modern notation). In 1960 Jones[

Reference Jones

75

] measured the velocity of light in a magnetic field to high precision and found no deviation from its vacuum value. A year later, Erber[

Reference Erber

64

] discussed a number of settings (including Watson’s) that might allow measurement of a quadratic dependence of the vacuum refractive indices, hence a Cotton–Mouton effect[

Reference Cotton and Mouton

76

, Reference Cotton and Mouton

77

], as predicted by QED. Klein and Nigam[

Reference Klein and Nigam

61

] suggested using a static electric field inside a plane capacitor, but ruled the birefringence effect to be way too small. In 1979, Iacopini and Zavattini pointed out that one may use strong static magnetic fields and optimize the geometric factor

![]() ${\left(z/\lambda \right)}^2$

. To this end, one should propagate a stable optical laser beam through a magnetic cavity and increase the optical path length

${\left(z/\lambda \right)}^2$

. To this end, one should propagate a stable optical laser beam through a magnetic cavity and increase the optical path length

![]() $z$

through multiple reflections. This idea has been realized in the PVLAS experiment, which recently celebrated its 20th anniversary[

Reference Ejlli, Valle, Gastaldi, Messineo, Pengo, Ruoso and Zavattini

78

]. There are also a number of competing or complementary experiments, for which an overview may be found in Ref. [Reference Battesti, Beard, Böser, Bruyant, Budker, Crooker, Daw, Flambaum, Inada, Irastorza, Karbstein, Kim, Kozlov, Melhem, Phipps, Pugnat, Rikken, Rizzo, Schott, Semertzidis and Zavattini79] together with an extensive list of references. Figure 5, reproduced with permission from Ref. [Reference Ejlli, Valle, Gastaldi, Messineo, Pengo, Ruoso and Zavattini78], presents the historical evolution of the experimental results, the most recent of which are still about an order of magnitude above the QED prediction. (The error bars represent an uncertainty of one sigma.) The current best value has been reported by the PVLAS-FE experiment as follows:

$z$

through multiple reflections. This idea has been realized in the PVLAS experiment, which recently celebrated its 20th anniversary[

Reference Ejlli, Valle, Gastaldi, Messineo, Pengo, Ruoso and Zavattini

78

]. There are also a number of competing or complementary experiments, for which an overview may be found in Ref. [Reference Battesti, Beard, Böser, Bruyant, Budker, Crooker, Daw, Flambaum, Inada, Irastorza, Karbstein, Kim, Kozlov, Melhem, Phipps, Pugnat, Rikken, Rizzo, Schott, Semertzidis and Zavattini79] together with an extensive list of references. Figure 5, reproduced with permission from Ref. [Reference Ejlli, Valle, Gastaldi, Messineo, Pengo, Ruoso and Zavattini78], presents the historical evolution of the experimental results, the most recent of which are still about an order of magnitude above the QED prediction. (The error bars represent an uncertainty of one sigma.) The current best value has been reported by the PVLAS-FE experiment as follows:

Figure 5 Historical evolution of the results for vacuum birefringence experiments employing static magnetic fields (reproduced with permission from Ref. [Reference Ejlli, Valle, Gastaldi, Messineo, Pengo, Ruoso and Zavattini78], where more details can be found). The green horizontal line represents

![]() ${k}_{\mathrm{CMV}}\equiv {c}_2-{c}_1$

.

${k}_{\mathrm{CMV}}\equiv {c}_2-{c}_1$

.

where

![]() $B$

denotes the external static magnetic field being probed. To compare with the QED result, we note that for a static magnetic field probed at the right angle,

$B$

denotes the external static magnetic field being probed. To compare with the QED result, we note that for a static magnetic field probed at the right angle,

![]() ${T}_{\mathrm{\ell \ell }}={B}^2$

. Introducing the magnetic Sauter–Schwinger field strength,

${T}_{\mathrm{\ell \ell }}={B}^2$

. Introducing the magnetic Sauter–Schwinger field strength,

![]() ${B}_{\mathrm{S}}={m}^2/e=4.41\times {10}^9\ \mathrm{T}$

, the general result in Equation (18) leads to the following:

${B}_{\mathrm{S}}={m}^2/e=4.41\times {10}^9\ \mathrm{T}$

, the general result in Equation (18) leads to the following:

$$\begin{align}{k}_{\mathrm{CMV}} &\equiv \frac{\Delta {n}^{\mathrm{stat}}}{B^2} ={c}_2-{c}_1=\frac{2{\alpha}^2}{15{m}^4}=\frac{\alpha }{30\pi}\frac{1}{B_{\mathrm{S}}^2} \nonumber \\ &=4\times {10}^{-24}\ {\mathrm{T}}^{-2}.\end{align}$$

$$\begin{align}{k}_{\mathrm{CMV}} &\equiv \frac{\Delta {n}^{\mathrm{stat}}}{B^2} ={c}_2-{c}_1=\frac{2{\alpha}^2}{15{m}^4}=\frac{\alpha }{30\pi}\frac{1}{B_{\mathrm{S}}^2} \nonumber \\ &=4\times {10}^{-24}\ {\mathrm{T}}^{-2}.\end{align}$$

This constant, containing only the basic QED parameters, has been called the Cotton–Mouton constant of the vacuum (hence the acronym CMV) in Ref. [Reference Battesti, Beard, Böser, Bruyant, Budker, Crooker, Daw, Flambaum, Inada, Irastorza, Karbstein, Kim, Kozlov, Melhem, Phipps, Pugnat, Rikken, Rizzo, Schott, Semertzidis and Zavattini79]. The same value is obtained for the HED-HIBEF scenario of probing an optical laser background, cf. Equations (16) and (18), as

![]() ${T}_{\mathrm{\ell \ell }}=4{F}^2=4{I}_{\mathrm{L}}$

(assuming a head-on collision). Hence

${T}_{\mathrm{\ell \ell }}=4{F}^2=4{I}_{\mathrm{L}}$

(assuming a head-on collision). Hence

where CF stands for ‘crossed field’ with

![]() $F=E=B$

and

$F=E=B$

and

![]() $\mathbf{E}\cdot \mathbf{B}=0$

.

$\mathbf{E}\cdot \mathbf{B}=0$

.

Strong-field vacuum polarization effects also play an important role in astrophysics and cosmology. For instance, extreme field magnitudes can be found in the magnetosphere of neutron stars and magnetars. Several years ago it was claimed that measurements of the polarization degree of such neutron stars provide evidence for an active role of vacuum birefringence[ Reference Mignani, Testa, Caniulef, Taverna, Turolla, Zane and Wu 10 ]. The subsequent scientific debate[ Reference Capparelli, Damiano, Maiani and Polosa 80 ] highlights the necessity of a controlled laboratory verification of the effect, which in turn should provide input for improved models of neutron star environments.

Very recently the STAR collaboration has reported the observation of (linear) Breit–Wheeler pair production[

Reference Adam, Adamczyk and Adams

81

], that is, the process

![]() $\gamma +\gamma \to {e}^{+}+{e}^{-}$

. As this was realized in ultra-peripheral heavy-ion collisions, the pair production is actually proceeding via the Landau–Lifshitz process[

Reference Landau and Lifshitz

82

] at low photon virtualities; see Figure 6(a). Via the optical theorem, this process is related to Delbrück scattering as observed by the ATLAS collaboration – upon ‘cutting’ the fermion loop in Figure 3(b). It has been shown that polarization flips induced by this diagram lead to modulations in the angular pair spectra, as shown in Figure 6(b) reproduced with permission from the recent review[

Reference Brandenburg, Seger, Xu and Zha

11

]. The authors of Ref. [Reference Brandenburg, Seger, Xu and Zha11] have interpreted this as an indirect signal for vacuum birefringence.

$\gamma +\gamma \to {e}^{+}+{e}^{-}$

. As this was realized in ultra-peripheral heavy-ion collisions, the pair production is actually proceeding via the Landau–Lifshitz process[

Reference Landau and Lifshitz

82

] at low photon virtualities; see Figure 6(a). Via the optical theorem, this process is related to Delbrück scattering as observed by the ATLAS collaboration – upon ‘cutting’ the fermion loop in Figure 3(b). It has been shown that polarization flips induced by this diagram lead to modulations in the angular pair spectra, as shown in Figure 6(b) reproduced with permission from the recent review[

Reference Brandenburg, Seger, Xu and Zha

11

]. The authors of Ref. [Reference Brandenburg, Seger, Xu and Zha11] have interpreted this as an indirect signal for vacuum birefringence.

Figure 6 The STAR experiment. (a) Landau–Lifshitz process. (b) Modulation signalling vacuum birefringence by means of the optical theorem (reproduced with permission from Ref. [Reference Brandenburg, Seger, Xu and Zha11]).

Figure 7 Overview of different collision geometries: (a) the conventional head-on two-beam scenario; (b)–(e) three-beam scenarios where the XFEL is collided with two optical lasers. In (c) one of the optical beams is frequency doubled[ Reference Ahmadiniaz, Cowan, Grenzer, Franchino-Viñas, Garcia, Šmid, Toncian, Trejo and Schützhold 83 ].

3 Prospective scenarios

As detailed in the previous section, real LbL scattering has a very small cross-section. Any prospective scenario must be able to deliver a signal that can be distinguished from the noise of the background photons. At the moment, three different proposals – and viable combinations thereof – are available that constitute prospective routes towards a first measurement of the effect at HED-HIBEF. All these proposals are intimately related and look very similar at first glance. However, they differ decisively in the details and thus come with different experimental challenges. Two of these are two-beam scenarios using the collision of the XFEL with the intense ReLaX beam, and the third one summarizes three-beam scenarios requiring the XFEL to collide with two intense laser beams, generated by splitting the original ReLaX beam into two beams. (See Figure 7 for an overview of different collision geometries.) Focusing only on the essentials (see Sections 3.1–3.3 below for a detailed discussion of each of these scenarios), the two-beam scenarios are as follows.

-

(1) The conventional vacuum birefringence scenario[ Reference Heinzl, Liesfeld, Amthor, Schwoerer, Sauerbrey and Wipf 67 , Reference Schlenvoigt, Heinzl, Schramm, Cowan and Sauerbrey 84 ] that envisions the collision of the two beams in a counter-propagation geometry. It uses exclusively the polarization flip of X-ray probe photons. This small quantum vacuum signal needs to be separated from the large background of probe photons traversing the high-intensity pump focus without interaction. A key parameter for the measurement of this effect is the quality of the employed polarimeter, which is typically quantified in terms of its polarization purity

$\mathcal{P}$

. This represents the fraction of background photons registered in the ideally empty, perpendicularly polarized mode[

Reference Marx, Schulze, Uschmann, Kämpfer, Lötzsch, Wehrhan, Wagner, Detlefs, Roth, Härtwig, Förster, Stöhlker and Paulus

85

]. For the XFEL and intense laser parameters attainable at HED-HIBEF the signal is found to be background dominated[

Reference Schulze, Grabiger, Loetzsch, Marx-Glowna, Schmitt, Garcia, Hippler, Huang, Karbstein, Konôpková, Schlenvoigt, Schwinkendorf, Strohm, Toncian, Uschmann, Wille, Zastrau, Röhlsberger, Stöhlker, Cowan and Paulus

72

]. However, by an appropriate choice of beam waists, the divergence of the signal can be made wider than that of the probe, such that angular cuts can be used to improve the signal-to-background ratio at the expense of reduced absolute photon numbers[

Reference King, Di Piazza and Keitel

17

, Reference King, Di Piazza and Keitel

86

–

Reference Karbstein, Gies, Reuter and Zepf

88

].

$\mathcal{P}$

. This represents the fraction of background photons registered in the ideally empty, perpendicularly polarized mode[

Reference Marx, Schulze, Uschmann, Kämpfer, Lötzsch, Wehrhan, Wagner, Detlefs, Roth, Härtwig, Förster, Stöhlker and Paulus

85

]. For the XFEL and intense laser parameters attainable at HED-HIBEF the signal is found to be background dominated[

Reference Schulze, Grabiger, Loetzsch, Marx-Glowna, Schmitt, Garcia, Hippler, Huang, Karbstein, Konôpková, Schlenvoigt, Schwinkendorf, Strohm, Toncian, Uschmann, Wille, Zastrau, Röhlsberger, Stöhlker, Cowan and Paulus

72

]. However, by an appropriate choice of beam waists, the divergence of the signal can be made wider than that of the probe, such that angular cuts can be used to improve the signal-to-background ratio at the expense of reduced absolute photon numbers[

Reference King, Di Piazza and Keitel

17

, Reference King, Di Piazza and Keitel

86

–

Reference Karbstein, Gies, Reuter and Zepf

88

]. -

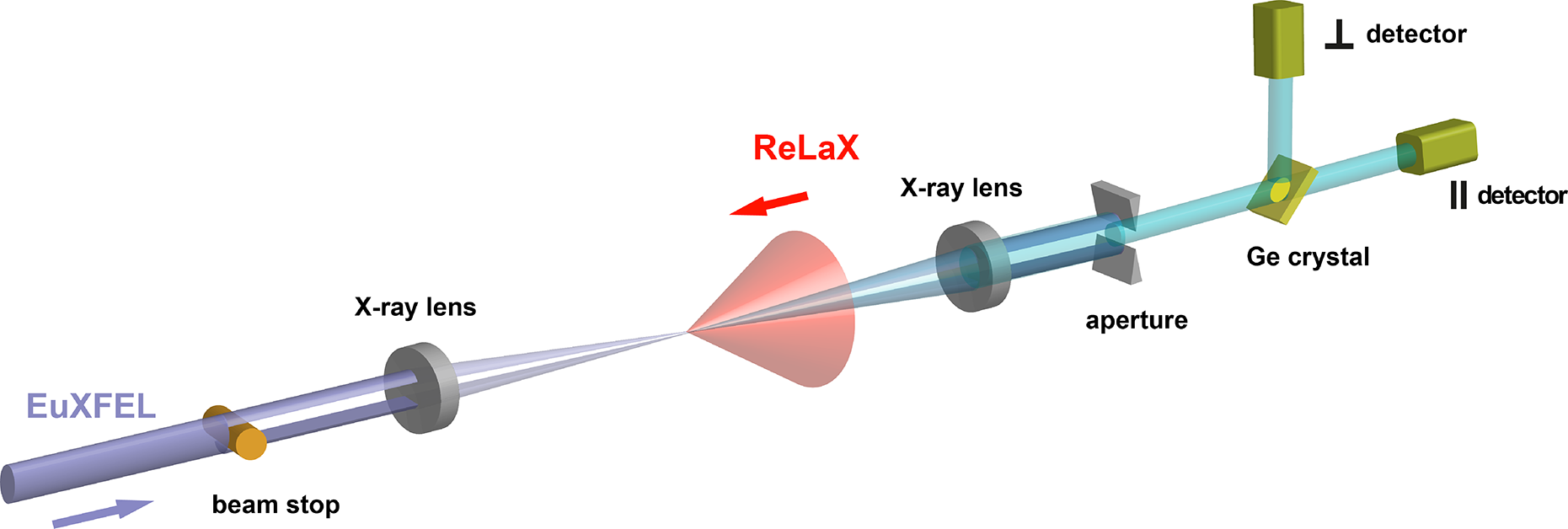

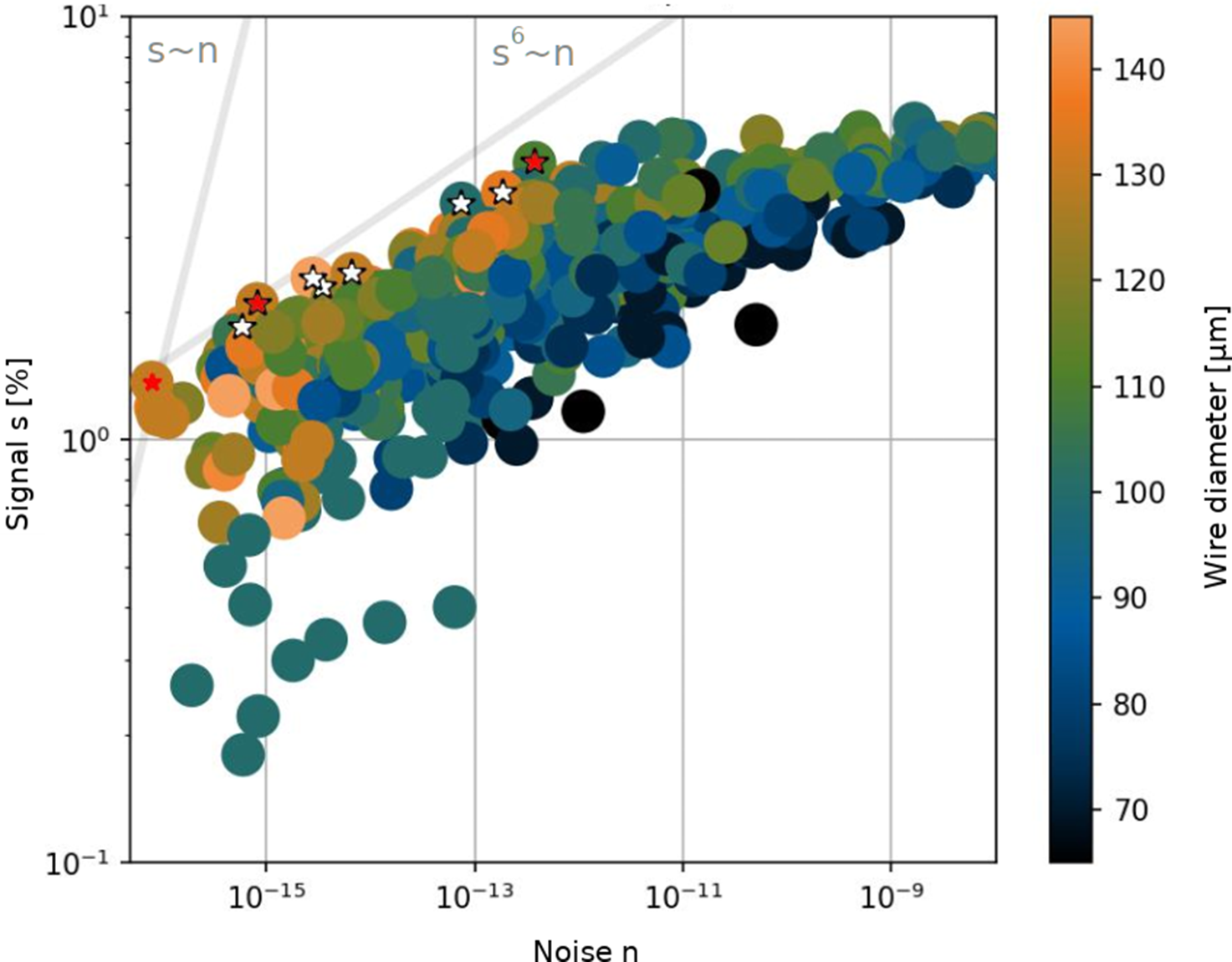

(2) A dark-field approach[ Reference Karbstein, Ullmann, Mosman and Zepf 23 ] based on modifying the probe beam with a well-defined beam stop so as to exhibit a shadow in both the converging and expanding beams while retaining a peaked focus profile. This should allow access to both the parallel and perpendicular polarized components of the nonlinear vacuum response scattered into the shadow where the background is significantly reduced. In this scenario, the key parameter is the quality of the shadow, which can be quantified in terms of the unwanted background measured within the shadow. It remains to be shown that a sufficiently good shadow quality

$\mathcal{S}$

ensuring a signal-to-background ratio above unity can be realized in experiments for the XFEL and intense laser parameters available at HED-HIBEF. However, the outcome of an elementary proof-of-concept experiment at an X-ray tube[

Reference Karbstein, Ullmann, Mosman and Zepf

23

] and the results of numerical diffraction simulations performed by our collaboration look sufficiently promising that this scenario is the one we have selected to first explore experimentally; cf. also Section 4 below.

$\mathcal{S}$

ensuring a signal-to-background ratio above unity can be realized in experiments for the XFEL and intense laser parameters available at HED-HIBEF. However, the outcome of an elementary proof-of-concept experiment at an X-ray tube[

Reference Karbstein, Ullmann, Mosman and Zepf

23

] and the results of numerical diffraction simulations performed by our collaboration look sufficiently promising that this scenario is the one we have selected to first explore experimentally; cf. also Section 4 below.

Finally, the three-beam scenarios aim at verifying quantum vacuum nonlinearity in the following.

-

(3) Four-wave-mixing processes[ Reference Lundstrom, Brodin, Lundin, Marklund, Bingham, Collier, Mendonca and Norreys 14 , Reference Lundin, Marklund, Lundstrom, Brodin, Collier, Bingham, Mendonca and Norreys 15 , Reference Ahmadiniaz, Cowan, Grenzer, Franchino-Viñas, Garcia, Šmid, Toncian, Trejo and Schützhold 83 , Reference Gies, Karbstein, Kohlfürst and Seegert 89 – Reference Berezin and Fedotov 92 ] where the XFEL is collided with two intense optical laser beams that are derived from the same source and are focused to the same spot. Since the optical beams have the same frequency and propagate in different directions, this enables a new kind of quasi-elastic scattering signal at the XFEL photon frequency, the generation of which involves the absorption of a field quantum from one of the intense beams and emission into the other. Due to the associated finite momentum transfer, this signal is scattered into a well-defined direction away from the forward direction of the XFEL. Moreover, three-beam setups can also induce sizeable signals characterized by a frequency shift. While an enlarged phase space seems beneficial, it remains to be shown that the additional challenges coming with the experimental control of three laser beams can be mastered in such a way as to benefit from the additional signal photon channels facilitated by three-beam scenarios.

For the experimental implementation of a given scenario, the central interest is in the number of X-ray signal photons that can be discerned from the typically large background of the EuXFEL beam. Only these constitute a signature of quantum vacuum nonlinearity that is detectable in an experiment. To address this theoretically, we model the near-infrared (NIR) high-intensity and XFEL beams driving the nonlinear quantum vacuum signals as paraxial solutions of the wave equation, supplemented with a Gaussian pulse envelope. In general, the electric field of a paraxial beam can be expanded as

![]() $\mathbf{E}={\mathbf{E}}^{(0)}\left(\varsigma \right)+\varsigma \kern0.1em {\mathbf{E}}^{(1)}\left(\varsigma \right)+\cdots$

, that is, in powers of the small parameter

$\mathbf{E}={\mathbf{E}}^{(0)}\left(\varsigma \right)+\varsigma \kern0.1em {\mathbf{E}}^{(1)}\left(\varsigma \right)+\cdots$

, that is, in powers of the small parameter

![]() $\varsigma ={w}_0/{z}_{\mathrm{R}}$

, where

$\varsigma ={w}_0/{z}_{\mathrm{R}}$

, where

![]() ${w}_0$

is the beam waist and

${w}_0$

is the beam waist and

![]() ${z}_{\mathrm{R}}=\omega {w}_0^2/2$

is the Rayleigh length of the fundamental Gaussian beam solution;

${z}_{\mathrm{R}}=\omega {w}_0^2/2$

is the Rayleigh length of the fundamental Gaussian beam solution;

![]() $\omega =2\pi /\lambda$

is the oscillation frequency of a beam with central wavelength

$\omega =2\pi /\lambda$

is the oscillation frequency of a beam with central wavelength

![]() $\lambda$

. Throughout this work, we truncate the paraxial expansion at leading order and use

$\lambda$

. Throughout this work, we truncate the paraxial expansion at leading order and use

![]() $\mathbf{E}\approx {\mathbf{E}}^{(0)}\left(\varsigma \right)$

. For the XFEL beam focused to waist sizes much larger than its diffraction limit this is clearly a well-justified approximation. For the high-intensity laser we only consider waists fulfilling

$\mathbf{E}\approx {\mathbf{E}}^{(0)}\left(\varsigma \right)$

. For the XFEL beam focused to waist sizes much larger than its diffraction limit this is clearly a well-justified approximation. For the high-intensity laser we only consider waists fulfilling

![]() ${w}_0\ge 1.1\kern0.22em \unicode{x3bc} \mathrm{m}$

, which translates into

${w}_0\ge 1.1\kern0.22em \unicode{x3bc} \mathrm{m}$

, which translates into

![]() $\varsigma \le 0.23$

for the employed wavelength. A good indication that the leading-order paraxial approximation is sufficiently accurate also in this case is the good agreement of the analytical estimates based exclusively on the leading-order paraxial approximation with the corresponding outcomes of a Maxwell-consistent numerical simulation demonstrated in an all-optical setup where the colliding beams are focused close to the diffraction limit[

Reference Blinne, Gies, Karbstein, Kohlfürst and Zepf

93

, Reference Schütze, Doyle, Schreiber, Zepf and Karbstein

94

]. Apart from the probe beam featuring a central shadow in the dark-field scenario, the description of which requires the superposition of several Laguerre–Gaussian or Hermite–Gaussian modes, we model all laser fields as linearly polarized fundamental Gaussian beams. For a beam propagating in a positive

$\varsigma \le 0.23$

for the employed wavelength. A good indication that the leading-order paraxial approximation is sufficiently accurate also in this case is the good agreement of the analytical estimates based exclusively on the leading-order paraxial approximation with the corresponding outcomes of a Maxwell-consistent numerical simulation demonstrated in an all-optical setup where the colliding beams are focused close to the diffraction limit[

Reference Blinne, Gies, Karbstein, Kohlfürst and Zepf

93

, Reference Schütze, Doyle, Schreiber, Zepf and Karbstein

94

]. Apart from the probe beam featuring a central shadow in the dark-field scenario, the description of which requires the superposition of several Laguerre–Gaussian or Hermite–Gaussian modes, we model all laser fields as linearly polarized fundamental Gaussian beams. For a beam propagating in a positive

![]() $z$

direction, this implies the following electric field profile:

$z$

direction, this implies the following electric field profile:

$$\begin{align}E & ={E}_0\kern0.1em \exp \left(-{\left(\frac{t-z}{\tau /2}\right)}^2-{\left(\frac{r}{w}\right)}^2\right) \nonumber \\ &\quad \times \cos \left(\omega \left(t-z\right)-\frac{z}{z_{\mathrm{R}}}{\left(\frac{r}{w}\right)}^2+\arctan \frac{z}{z_{\mathrm{R}}}\right),\end{align}$$

$$\begin{align}E & ={E}_0\kern0.1em \exp \left(-{\left(\frac{t-z}{\tau /2}\right)}^2-{\left(\frac{r}{w}\right)}^2\right) \nonumber \\ &\quad \times \cos \left(\omega \left(t-z\right)-\frac{z}{z_{\mathrm{R}}}{\left(\frac{r}{w}\right)}^2+\arctan \frac{z}{z_{\mathrm{R}}}\right),\end{align}$$

where

![]() ${E}_0$

is the field amplitude,

${E}_0$

is the field amplitude,

![]() $\tau$

is the phase pulse duration,

$\tau$

is the phase pulse duration,

![]() $r=\sqrt{x^2+{y}^2}$

and

$r=\sqrt{x^2+{y}^2}$

and

![]() $w={w}_0\sqrt{1+{\left(z/{z}_{\mathrm{R}}\right)}^2}$

. This, in particular, implies that the peak intensity

$w={w}_0\sqrt{1+{\left(z/{z}_{\mathrm{R}}\right)}^2}$

. This, in particular, implies that the peak intensity

![]() ${I}_{\mathrm{peak}}$

of the optical laser pulse is related to the pulse energy

${I}_{\mathrm{peak}}$

of the optical laser pulse is related to the pulse energy

![]() $W$

via

$W$

via

![]() ${I}_{\mathrm{peak}}=8\sqrt{2/\pi}\kern0.1em W/\left(\pi {w}_0^2\tau \right)= 2 \times 10^{23}\ \mathrm{W}\ \mathrm{cm}^{-2} (W\ \mathrm{in}\ \mathrm{J}, w_0\ \mathrm{in}\ \unicode{x3bc} \mathrm{m}^{-2}, \tau\ \mathrm{in}\ \mathrm{fs}^{-1})$

. The focal width and pulse duration are related to the full-width-at-half-maximum (FWHM) parameters via

${I}_{\mathrm{peak}}=8\sqrt{2/\pi}\kern0.1em W/\left(\pi {w}_0^2\tau \right)= 2 \times 10^{23}\ \mathrm{W}\ \mathrm{cm}^{-2} (W\ \mathrm{in}\ \mathrm{J}, w_0\ \mathrm{in}\ \unicode{x3bc} \mathrm{m}^{-2}, \tau\ \mathrm{in}\ \mathrm{fs}^{-1})$

. The focal width and pulse duration are related to the full-width-at-half-maximum (FWHM) parameters via

![]() ${w}_0=0.85\kern0.22em {w}_{\mathrm{FWHM}}$

and

${w}_0=0.85\kern0.22em {w}_{\mathrm{FWHM}}$

and

![]() $\tau =1.7\kern0.22em {\tau}_{\mathrm{FWHM}}$

. Standard parameters to be available at HED-HIBEF are given in Table 2. For related activities at the Station of Extreme Light (SEL), which is currently under construction in Shanghai, China, see Refs. [Reference Shen, Bu, Xu, Xu, Ji, Li and Xu95–Reference Jin, Shen and Xu98].

$\tau =1.7\kern0.22em {\tau}_{\mathrm{FWHM}}$

. Standard parameters to be available at HED-HIBEF are given in Table 2. For related activities at the Station of Extreme Light (SEL), which is currently under construction in Shanghai, China, see Refs. [Reference Shen, Bu, Xu, Xu, Ji, Li and Xu95–Reference Jin, Shen and Xu98].

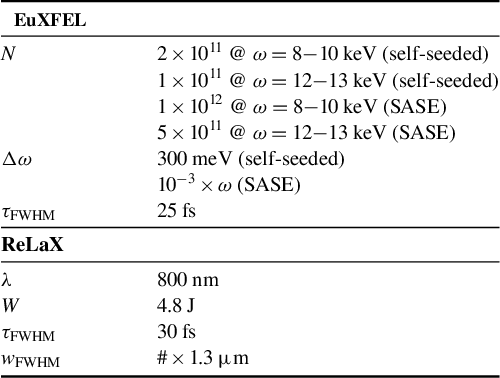

Table 2 EuXFEL and ReLaX parameters. The ReLaX focal width given here is for

![]() $f/\#$

focusing.

$f/\#$

focusing.

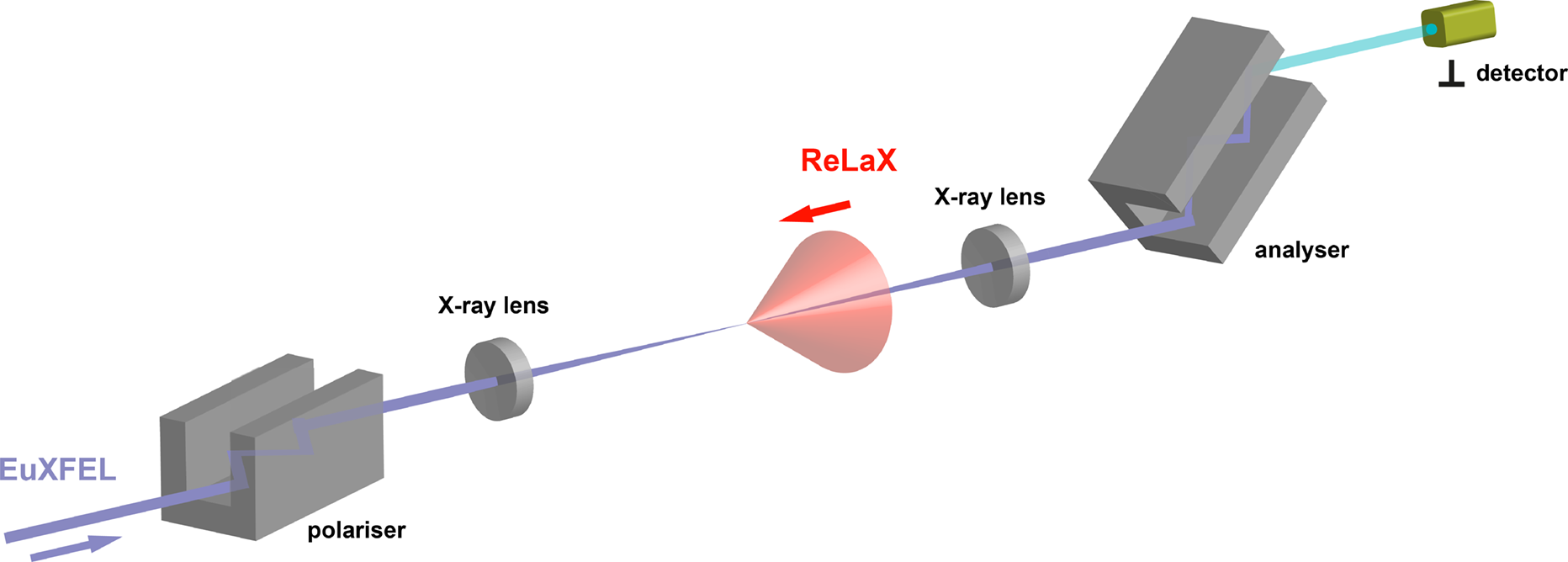

Figure 8 Schematic layout of the conventional scenario to measure vacuum birefringence. The XFEL beam is polarized with a channel-cut crystal, focused down to the interaction point with the counter-propagating high-intensity laser, recollimated and analysed with a second channel-cut crystal in a crossed position, such that only the

![]() $\perp$

-polarized component reaches the detector.

$\perp$

-polarized component reaches the detector.

3.1 Conventional two-beam scenario

The most extensively studied scenario in the present context is the conventional two-beam scenario[

Reference Aleksandrov, Ansel’m and Moskalev

66

], which envisions the head-on collision of the XFEL beam acting as probe and an NIR high-intensity pump[

Reference Heinzl, Liesfeld, Amthor, Schwoerer, Sauerbrey and Wipf

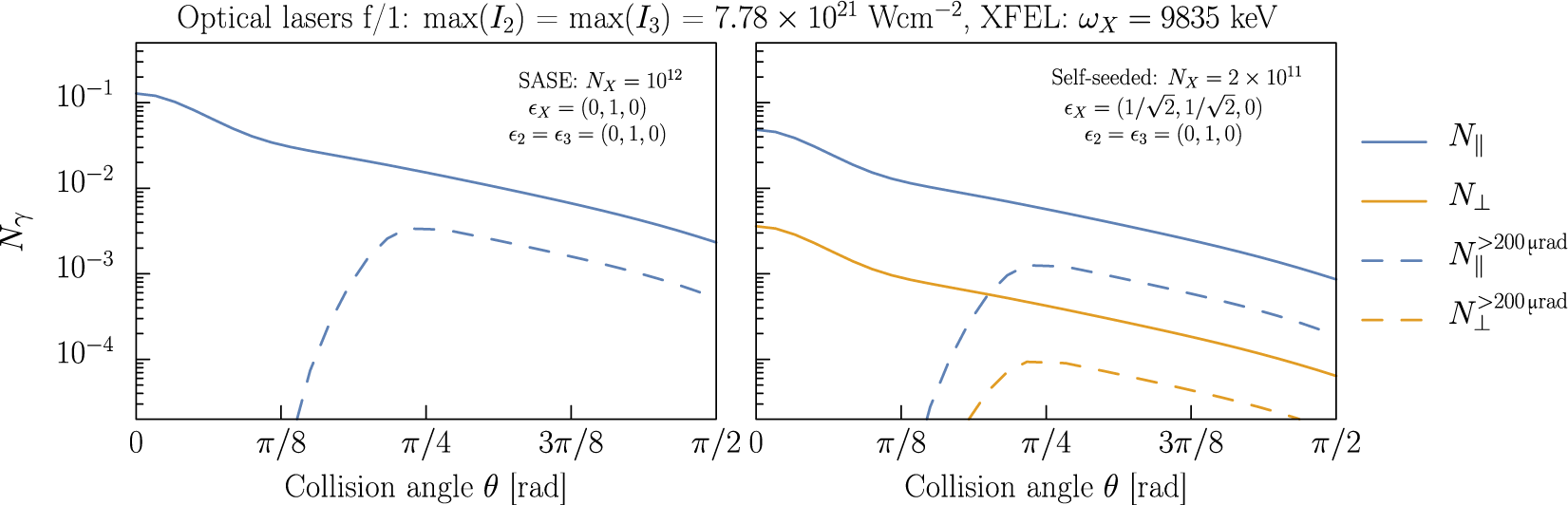

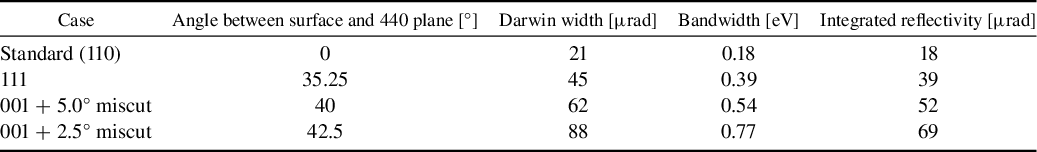

67