1.1 Aims

Volcanoes are of many types and behave in different ways. Different behaviour is partly because volcanoes are located in different tectonic environments. Many are associated with divergent plate boundaries, others with convergent plate boundaries, and some with transform-fault plate boundaries. In addition, there are volcanoes located within plate interiors, far from plate boundaries. To understand volcano behaviour with a view of being able to forecast volcanic eruptions we must use a variety of scientific techniques and approaches, primarily those of volcanotectonics. The main techniques and approaches for data collection, analysis, and interpretation are discussed in detail in later chapters, but they are briefly summarised here. The primary aims of this chapter are to:

Provide a definition of a volcano.

Define and explain the scope of the scientific field of volcanotectonics.

Explain briefly how volcanotectonic data are collected and analysed.

Discuss structural geological/tectonic techniques used for understanding volcanoes.

Discuss some main geophysical techniques used in volcanotectonics.

Explain accuracy, significant figures, and rounding of numbers in volcanotectonics.

Summarise the basic units and prefixes used in volcanotectonics.

1.2 Definition of a Volcano

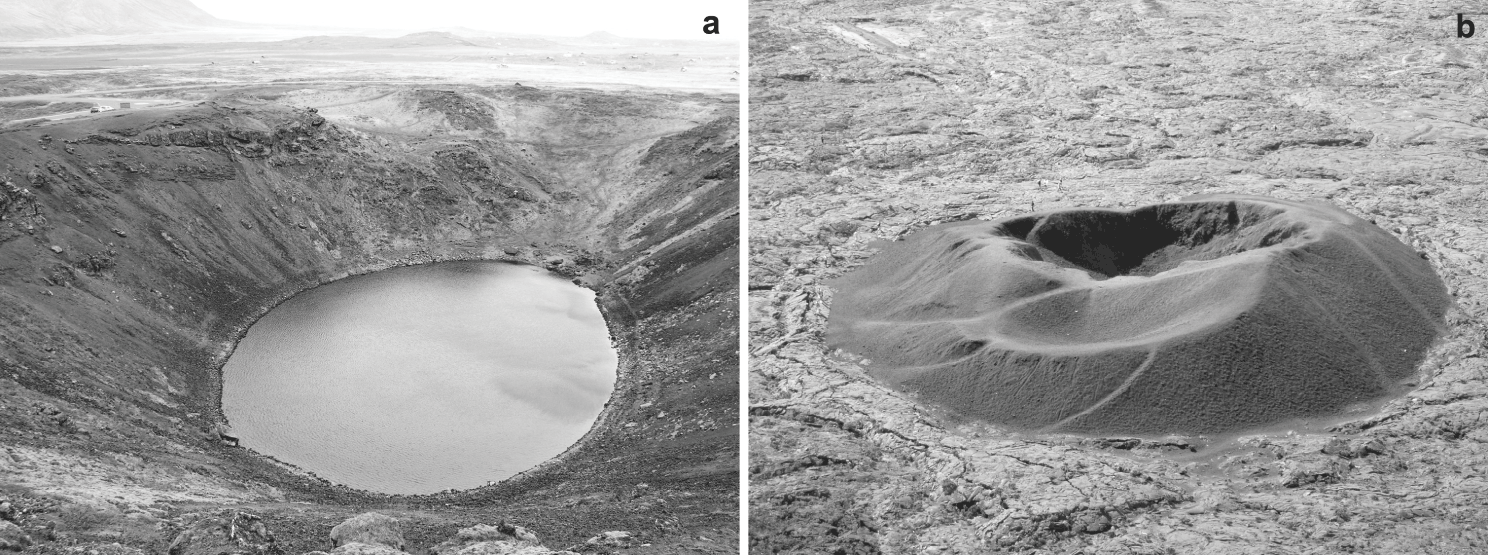

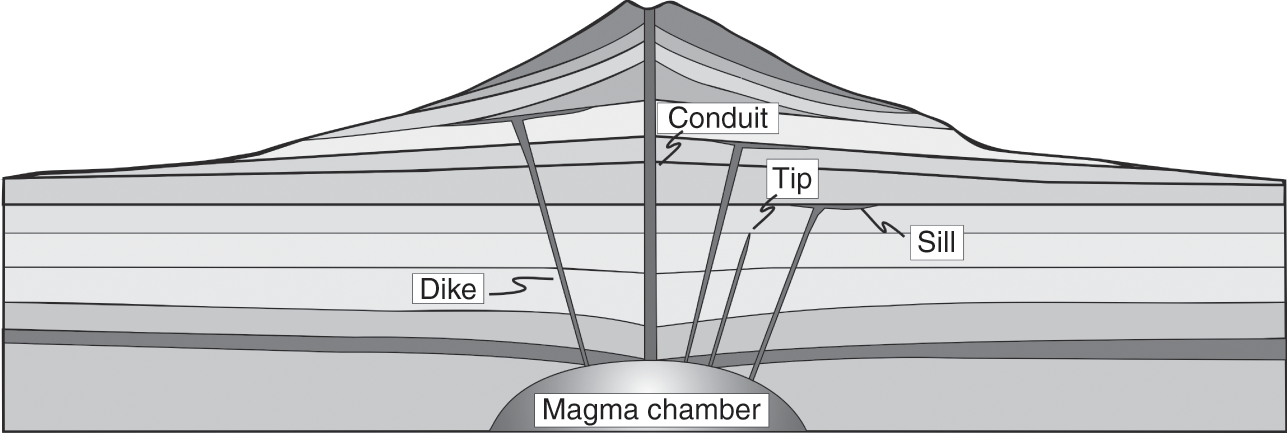

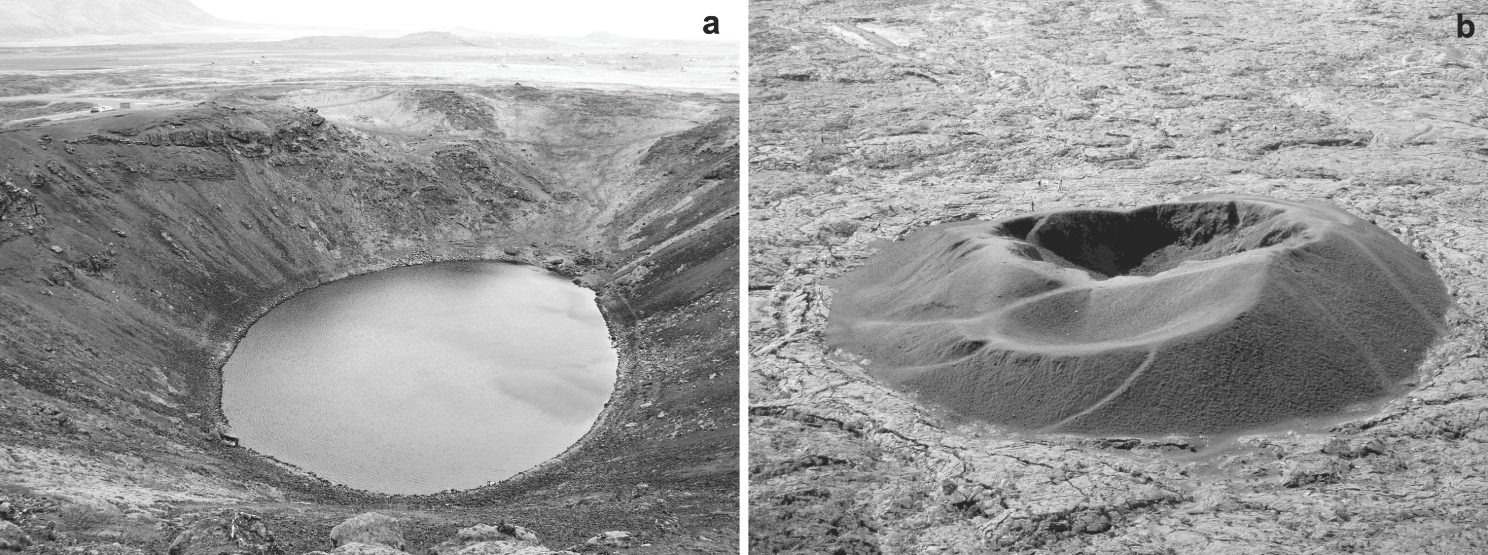

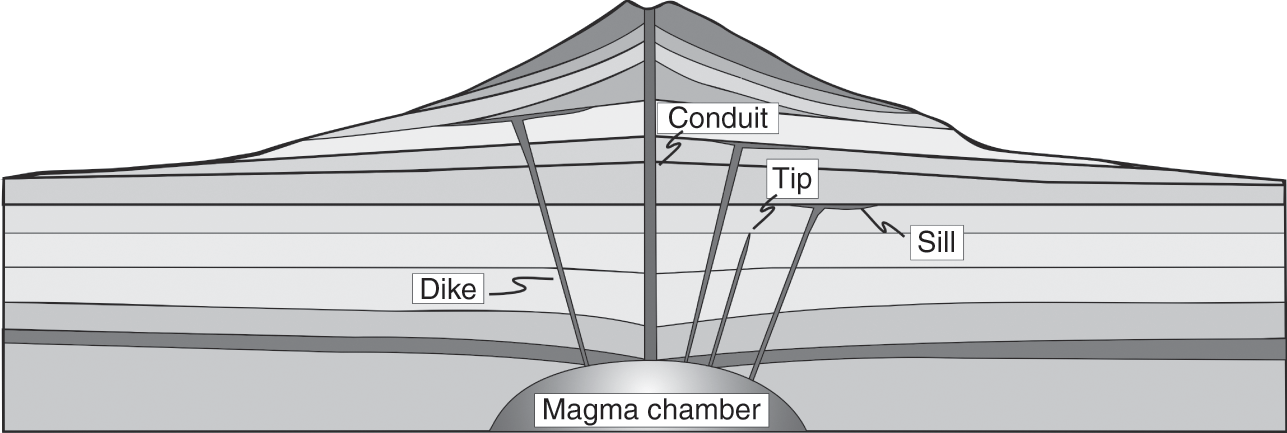

An active volcano is a vent that transports magma and volatiles to the Earth’s surface (Fig. 1.1). The accumulation of volcanic materials around the vent gives rise to a small volcano, commonly a crater cone, either a cinder/scoria cone or a spatter cone, and similar structures. Volcanoes formed in single eruptions are named monogenetic. Many of these are volcanic fissures, composed of many spatter and cinder/scoria cones, while others are single craters (Fig. 1.1a) or cinder cones (Fig. 1.1b). Repeated eruptions through a single or, more commonly, many nearby vents result in the accumulation of volcanic materials into a volcanic edifice (Figs. 1.2, 1.3). Volcanoes formed in many eruptions are named polygenetic. Polygenetic volcanoes forming edifices may be divided into two main types: basaltic edifices and stratovolcanoes (also named composite volcanoes). Well-known examples of basaltic edifices are the volcanoes Mauna Loa and Kilauea, forming part of the Big Island of Hawaii, and Fernandina, forming part of the Galapagos Islands. Well-known stratovolcanoes include Fuji in Japan, Teide on Tenerife (Canary Islands), Semeru in Indonesia, and Augustine in Alaska (Fig. 1.3).

Fig. 1.1 A volcano is vent that transports magma and volatiles to the surface. The volcanic landform may be either negative (a depression) or positive (a hill or a mountain). (a) Kerid, a collapsed scoria-and-spatter cone, formed some 9000 years ago in Iceland, may be regarded as a pit crater. It is elliptical in plan view. It has a maximum diameter of about 300 m and a minimum diameter of about 170 m. It forms a depression, 50 m deep, that is partly filled with groundwater. (b) Cinder (scoria) cone from the Enclose Fouque collapse in Piton de la Fournaise, Reunion. The cone is approximately 150 m wide and 30 m high.

Fig. 1.2 Schematic cross-section through a stratovolcano. Every stratovolcano is supplied with magma from one or more shallow magma chambers. During magma-chamber rupture, a dike (or an inclined sheet) becomes injected into the roof of the chamber. Most dikes/sheets become arrested at contacts between layers, some deflecting into sills, while others thin out (taper away) in vertical sections. A minority of injected dikes reaches the surface to supply magma to eruptions. Some major conduits in stratovolcanoes are partly composed of many dikes (and partly of volcanic breccia).

Fig. 1.3 Stratovolcanoes are formed by repeated eruptions within a limited surface area. They commonly rise high above their surroundings and have a cone shape, as exemplified here by the Augustine Volcano, forming one of the islands offshore Alaska (United States), with an elevation (height above sea level) of 1260 m and a maximum diameter at sea level of about 12 km. A highly active volcano with frequent eruptions, this photograph shows gas rising during the 2005–2006 eruption.

Volcanoes are regarded as active if they have erupted within a certain comparatively recent time period. The length of that period has been variously determined and there is, as yet, no agreed definition. Earlier, a volcano was regarded as active only if it had erupted in historical time. This definition is unsatisfactory for several reasons. First, historical time – which normally refers to the time covered by written documents – varies greatly between different volcanic areas. For instance, historical time spans several thousand years in many volcanically active Mediterranean countries, such as Italy and Greece, but is very short in other volcanically active areas such as western continental United States and Hawaii and the continent of Antarctica. Second, it has happened many times that a volcano which, in the above definition, was regarded as inactive, suddenly erupted. For example, the ice-covered Fourpeaked Mountain in Alaska, located some 100 km south of the highly active Augustine Volcano, had not erupted for some 10 000 years prior to its September 2006 eruption.

In recent years the reference period used is not historical time but rather the Holocene. In this definition, a volcano is active if it has erupted during the Holocene, that is, sometime during the past 11 700 years. This definition can generally be used, but with caution. For example, some very large and powerful volcanoes such as the Yellowstone caldera in the western United States erupt less frequently than once every 11 700 years. The last significant lava-flow eruption in the caldera was about 70 000 years ago, and the most recent (mostly steam) explosions occurred about 14 000 years ago. Yet, the Yellowstone caldera should be regarded as an active volcano.

Volcanoes that are no longer active are referred to as extinct. Another term that is used for an extinct volcano is a fossil volcano. A fossil volcano is normally much eroded so that parts of its internal structure can be observed (Fig. 1.2). When the magma source chamber of a fossil volcano is partly exposed as a pluton, that pluton is referred to as a fossil magma chamber. A volcano known to have erupted in Holocene but which has not erupted for a considerable time and shows little or no unrest is a dormant volcano.

As indicated, there are generally no absolute answers to whether a volcano should be regarded as active or extinct. A volcano may be regarded as potentially active so long as it has a chance of receiving magma from a source. The magma does not have to reach the surface for the volcano to be considered active: magma intrusions, such as dikes and sills (Fig. 1.2), are a clear indication that the volcano is active. To decide if a volcano is active, it is thus not enough to know its eruption frequency and history; we also need to know its magma intrusion frequency. Information on the latter can normally only be obtained from monitoring, primarily geophysical monitoring.

The likelihood that a volcano receives magma is discussed in later chapters. Here we mention this topic mainly to emphasise that there is no clear-cut answer to the question: ‘How many active volcanoes are there in the world?’ Similarly, we cannot answer the question: ‘How many seismically active fault zones are there in the world?’ However, we can and do assess the probability of, say, a 10-million-year-old volcano in Iceland erupting as being very small indeed.

1.3 Volcanotectonics – the Scope and Aims

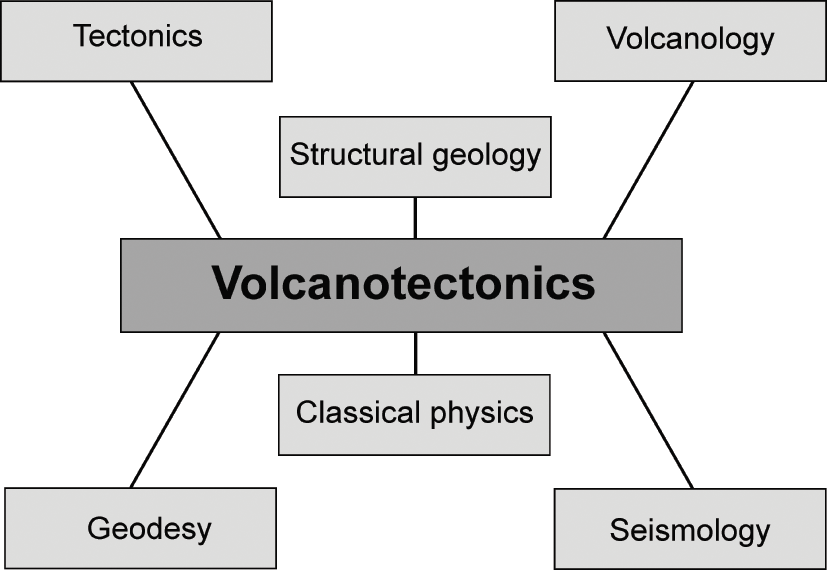

Volcanotectonics is a scientific field that uses the techniques and methods of tectonics, structural geology, geophysics, and physics to collect data on, analyse, and interpret physical processes in volcanoes. More specifically, volcanotectonics covers the following topics:

Collecting and analysing structural-geology, tectonic, and rock-physics data, as well as geodetic, seismic, and stress data, from active volcanoes.

Collecting and analysing structural-geology, tectonic, and rock-physics data from deeply eroded volcanoes, many of which may actually be, or for practical purposes regarded as, extinct. Such data can also be collected from caldera walls, drill holes, and other sections into active volcanoes.

Interpreting these data within the framework of volcanology, structural geology/tectonics, geophysics, and classical physics, particularly continuum physics – such as solid mechanics (including rock physics and fracture mechanics) and fluid mechanics.

Developing models and theories for understanding the processes that generate the data with a view of being able to make reliable forecasts as to the likely course of events or scenarios during unrest periods in volcanoes.

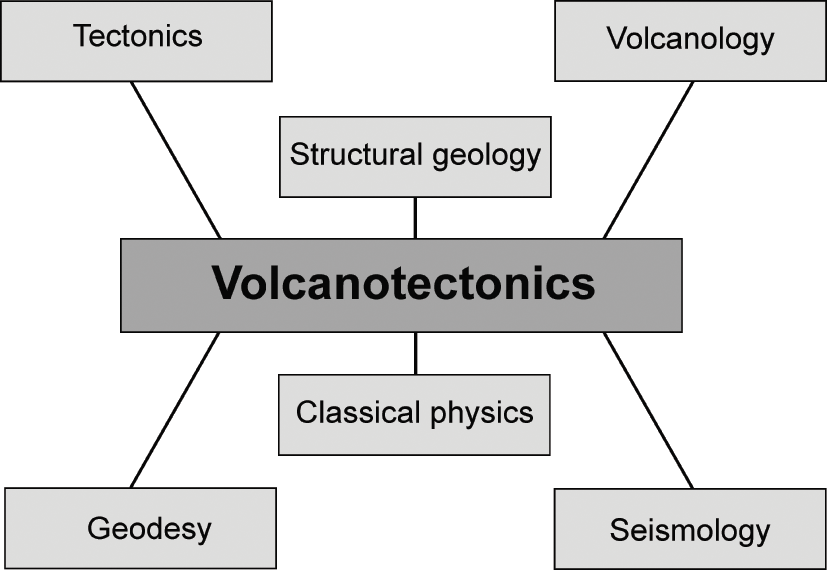

The connection between volcanotectonics and various related scientific fields are indicated schematically in Fig. 1.4. The basic field techniques used are derived from structural geology, for the outcrop scale, and from tectonics, for the regional scale, and are connected to the general field of volcanology. For active volcanoes, geodetic studies, as a part of geodesy, are very important and provide data for understanding some of the processes that occur inside the volcanoes during unrest periods. Similarly, seismological data related to physical processes inside and at the surface of a volcano can be used to monitor fracture development and the propagation of potential feeder-dikes towards the surface of the volcano.

Fig. 1.4 Volcanotectonics uses principles and methods from many scientific fields, the main ones being indicated here. Many of the data from active volcanoes are obtained through the methods of seismology (volcano or volcanotectonic earthquakes), geodesy (geodetic measurements of volcano deformation), and volcanology. Data on extinct and eroded volcanoes (and active volcanoes as well, partly from seismotectonics) are primarily obtained through the methods of tectonics, structural geology, and volcanology. The interpretations of the data in terms of models and theories rest on principles from classical physics (solid mechanics, fluid mechanics, statistical mechanics) and more recent derived fields (fracture mechanics, materials science, and rock physics).

Data, however, are of little use if they cannot be interpreted and understood within the framework of a plausible model or theory of volcano behaviour. Quantitative and testable models must, in the end, be based on physical theories and thus on the principles of physics. In volcanotectonics, like in solid-earth sciences in general, the main physical theories used are those that are derived from classical physics (physical theories that pre-date relativity and quantum mechanics), particularly continuum and classical mechanics. For solid-earth sciences, the theories are mainly from solid mechanics, which provides the foundation of the much more recent scientific fields of rock mechanics, fracture mechanics, and tectonophysics, as well as from fluid mechanics, including the more recent field of fluid transport in rock fractures (data on physical properties of rocks and crustal fluids, including magmas and lavas, are provided in Appendices A–F at the end of the book). Below are given more details on the basic techniques used in volcanotectonics.

1.4 Structural-Geology Techniques and Definitions

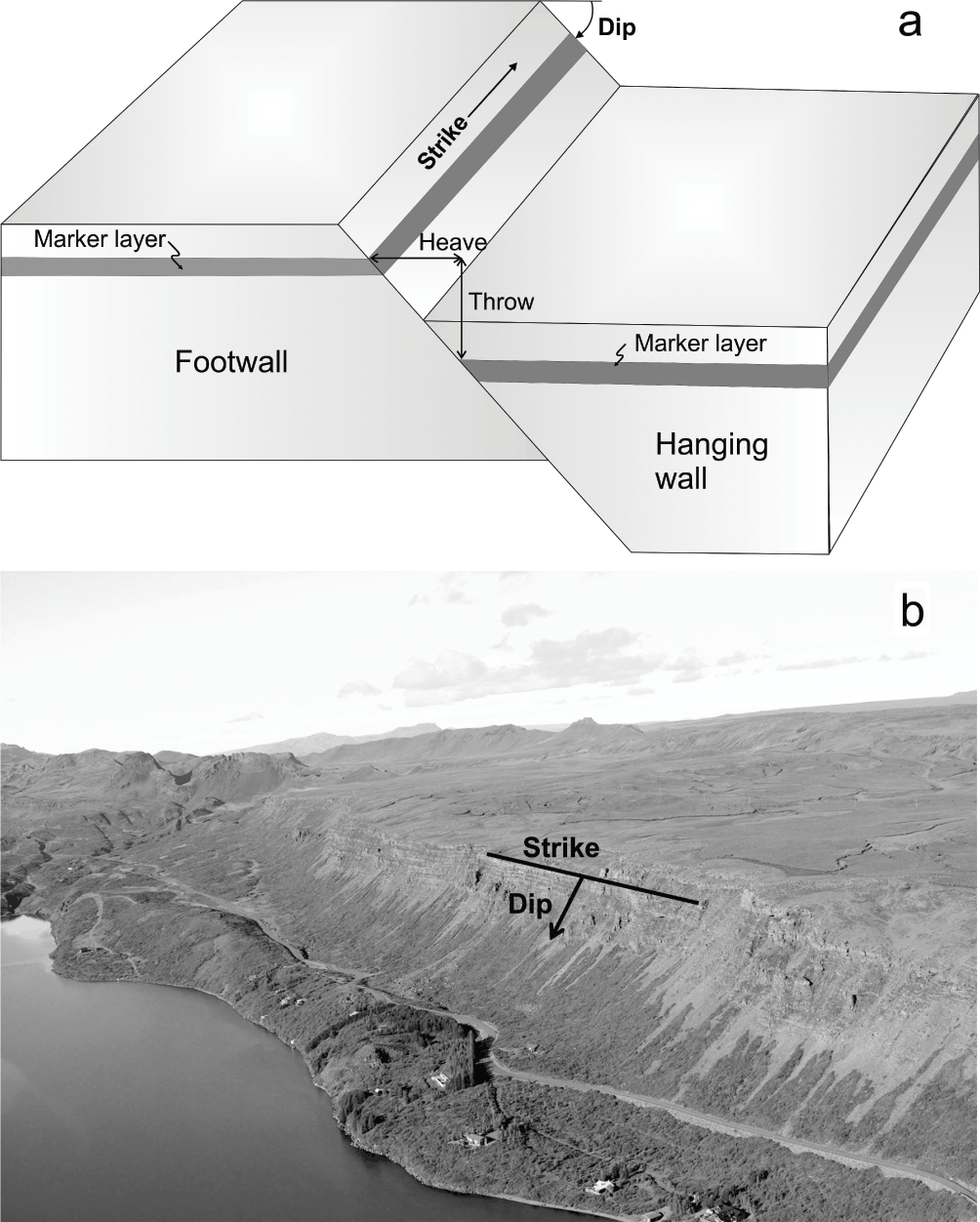

All the standard field methods of structural geology and tectonics are useful and are used in volcanotectonic studies. These include the measurements of the strike and dip of strata and structures, measurements of the dimensions and volumes of rock bodies, and related studies. Most of these topics are covered in textbooks on general field techniques in structural geology, but a brief summary is in order for easy reference.

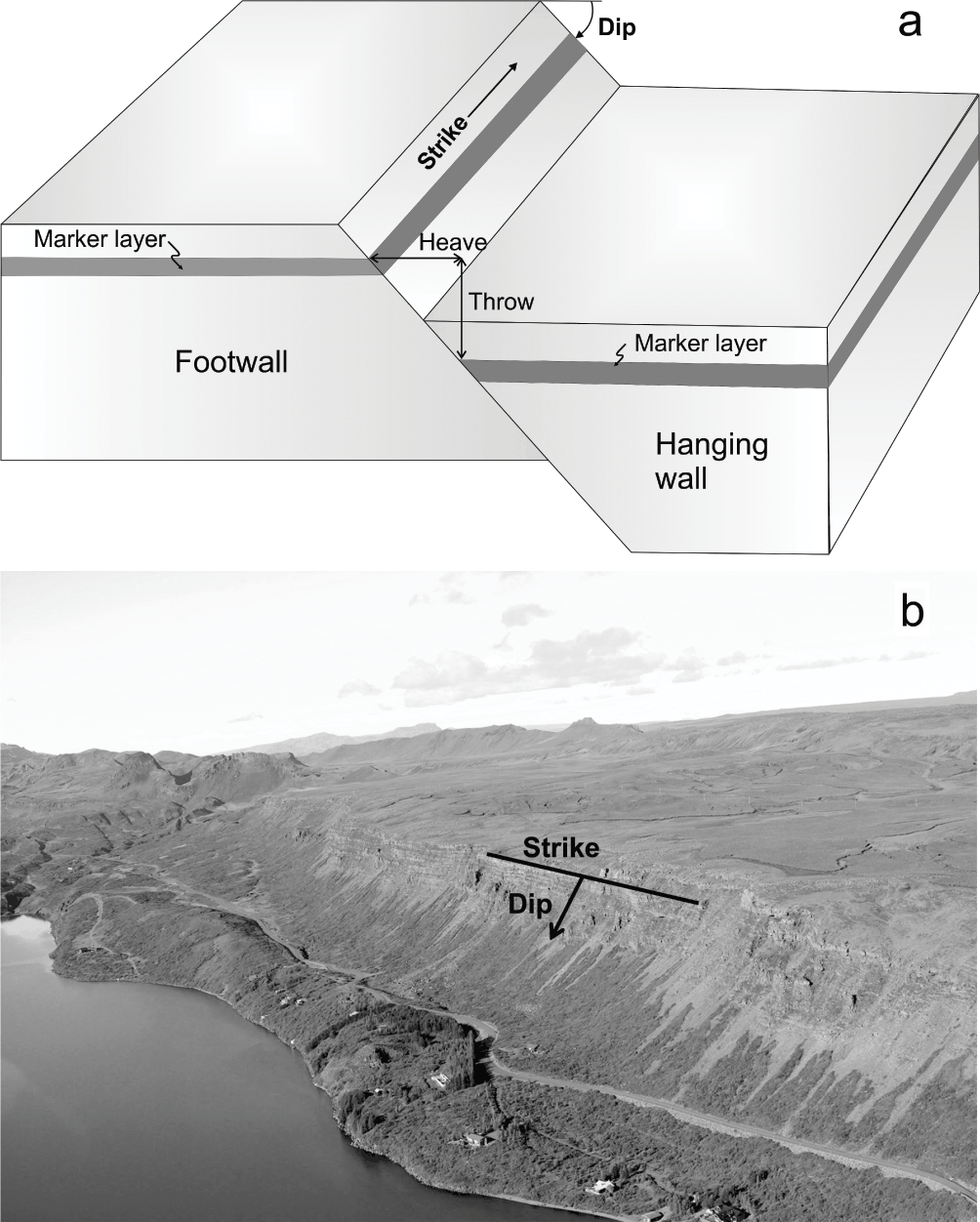

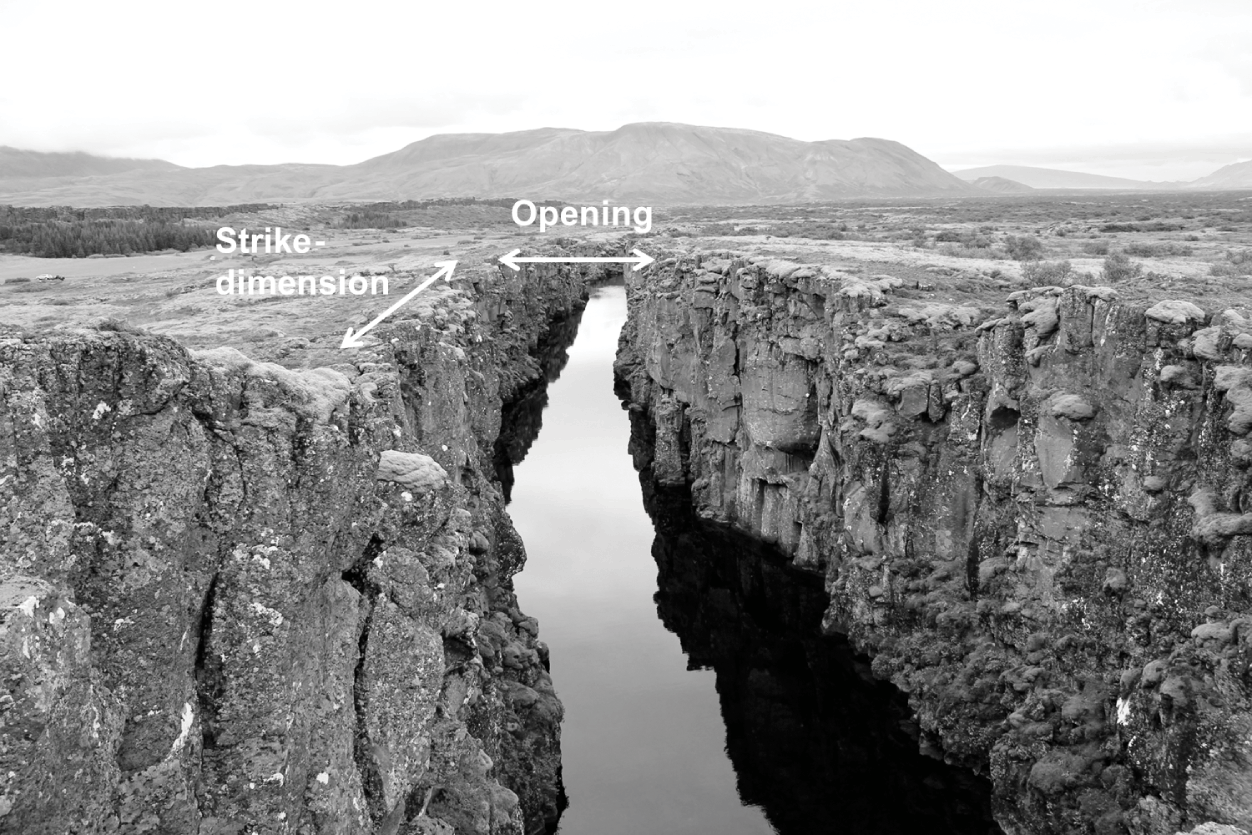

The strike of a rock body or a structure is the direction or trend of the plane of the rock body or the structure, such as a fault (Fig. 1.5). Alternatively, the strike is the direction of the intersection, which forms a line, between the plane of the body or structure and the horizontal plane. In the photographs, such as Fig. 1.5b, the view indicated in the captions is the direction in which the photographer is looking. Thus, view southwest (Fig. 1.5b) means that the photographer was looking (facing) southwest when the photograph was taken.

The dip is the acute angle between the plane of a structure and the horizontal plane (Fig. 1.5). The dip is measured in an imaginary vertical plane whose direction is at 90° to the plane of the structure. Please note that the dip is defined as an angle; it is therefore tautology to refer to the ‘dip angle’.

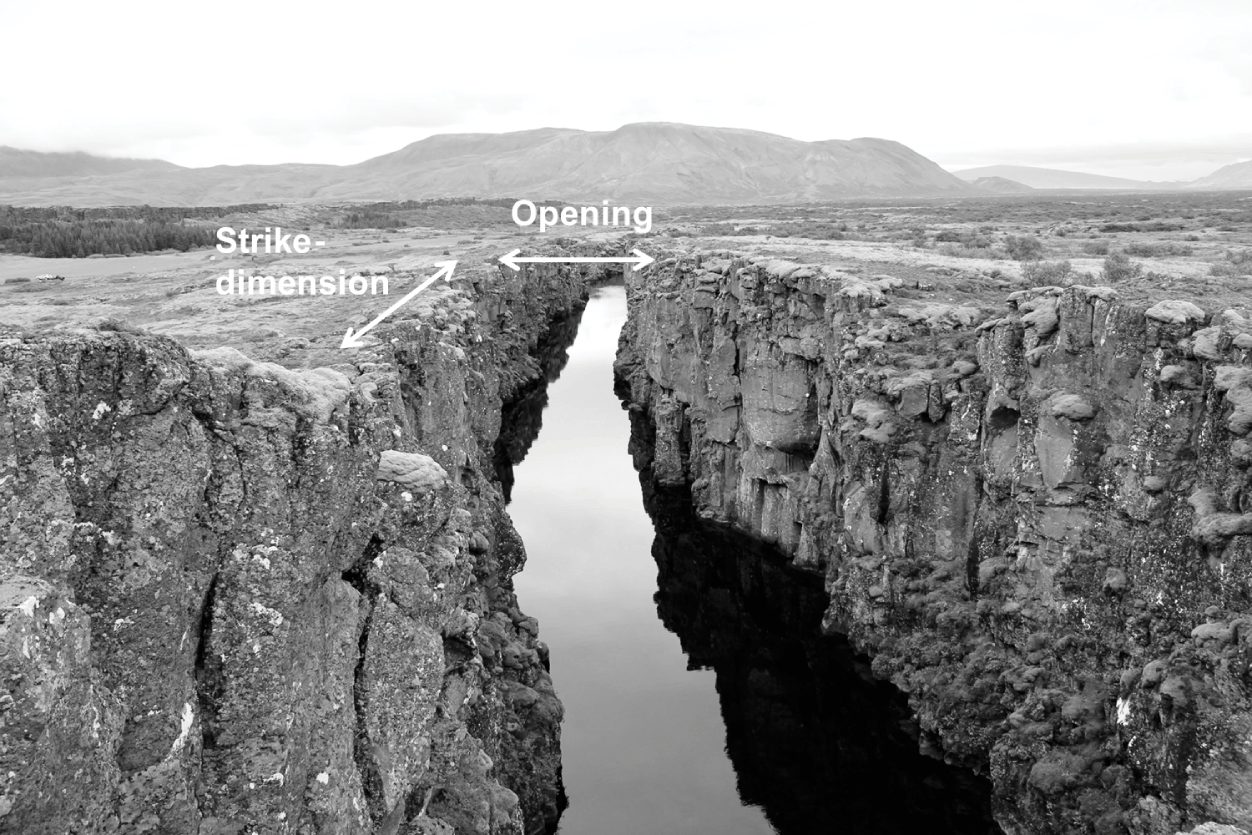

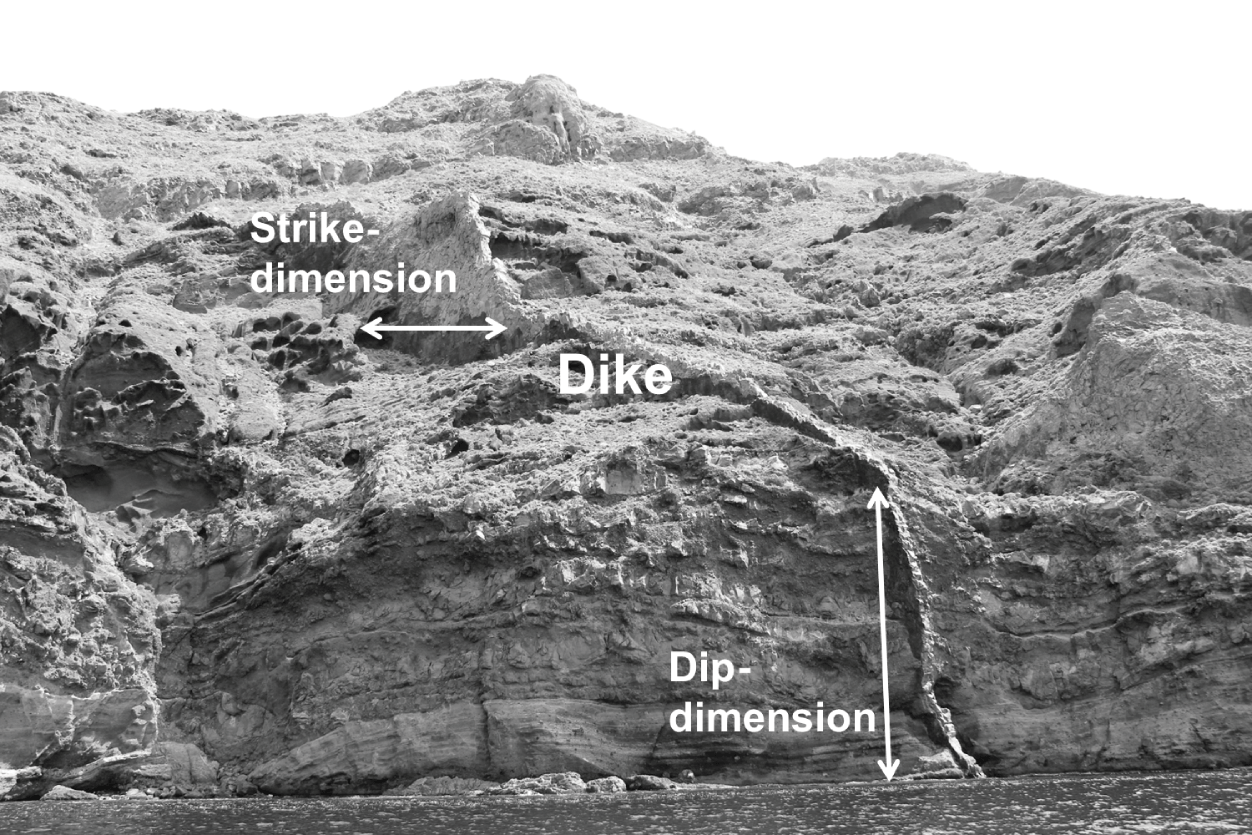

The strike-dimension (the dimension along the strike) of a body or structure is the length or dimension of the body or structure in the direction of its strike.

The dip-dimension (the dimension along the dip) of a body or structure is the length or dimension of the body or structure in the direction of its dip.

Together, the strike and dip define the attitude (sometimes named the orientation) of the structure or rock body.

Mechanically, there are two basic types of rock fractures: extension fractures and shear fractures. An extension fracture propagates or advances in a direction that is parallel with the maximum compressive principal stress, σ1 (and parallel with the intermediate principal stress, σ2), and perpendicular to the minimum compressive (maximum tensile) principal stress, σ3. The fracture opening displacement is thus parallel with the direction of σ3. There is no relative movement parallel with the fracture walls, only perpendicular to the walls (opening). When an extension fracture is opened or driven by internal fluid overpressure it is known as a hydrofracture (a fluid-driven fracture), but when it is opened by tectonic tensile stress, that is, by negative σ3, it is known as a tension fracture. A shear fracture forms by shear stress and shows clear evidence of fracture-parallel relative movement of the fracture walls. In geology, shear fractures are normally referred to as faults. Thus, all faults are shear fractures.

For an extension fracture, the opening is of fundamental importance and should be measured whenever possible. For a tension fracture, that is, a fracture opened by tensile stresses, the opening is referred to as an opening displacement (or just opening) and is the shortest distance between matching notches and jogs on the fracture walls (Fig. 1.6).

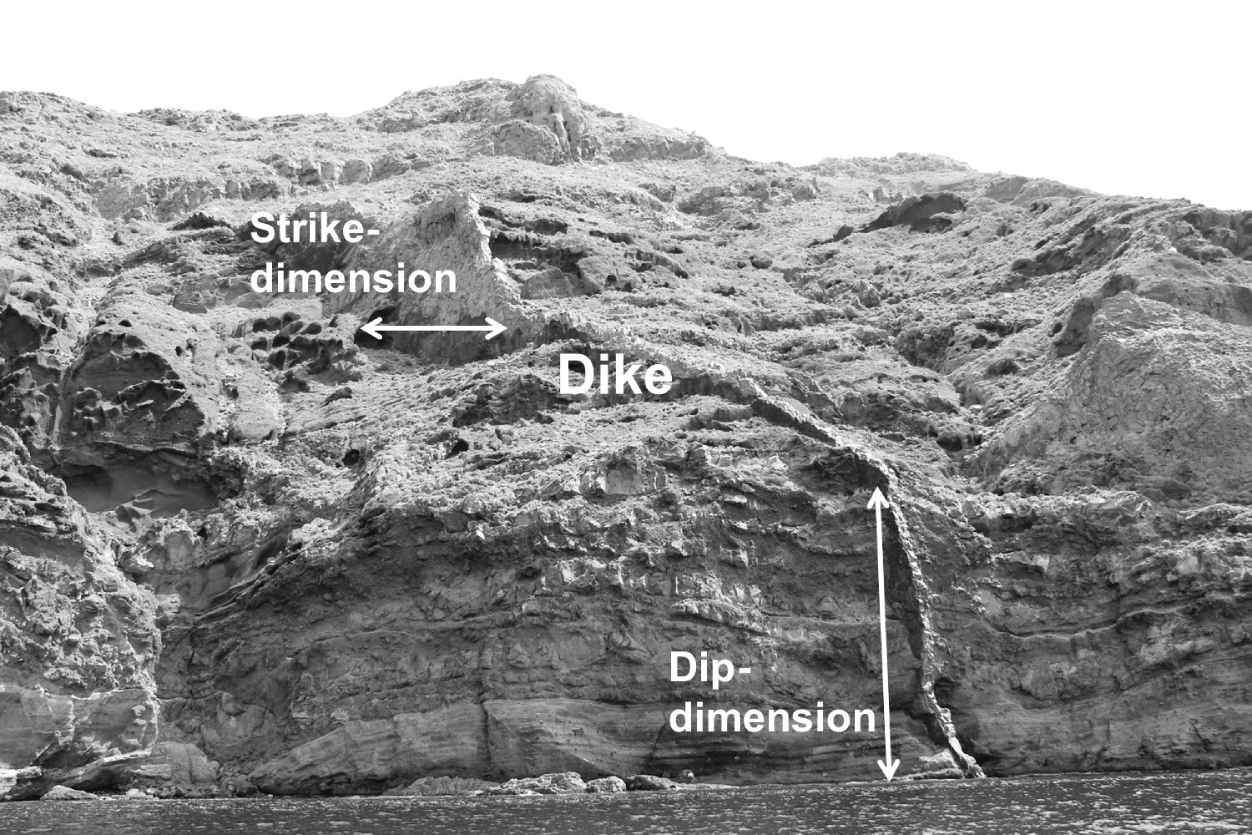

For a solidified or ‘frozen’ magma-filled fracture, namely an intrusive sheet such as a dike, an inclined sheet, or a sill, the measured opening is the palaeoaperture, which is measured as the thickness of the intrusive sheet (Fig. 1.7). Strictly, the opening of the magma-filled fracture when the magma was fluid may have been somewhat larger than the present thickness of the solidified intrusion. This follows because when a magma body solidifies it contracts or shrinks. However, the density difference between fluid and solidified magma is generally small, suggesting that the shrinkage is normally less than 10%. For mineral-filled extension fractures, known as mineral veins, the opening displacement is also the palaeoaperture and is measured as the vein thickness (Fig. 1.8).

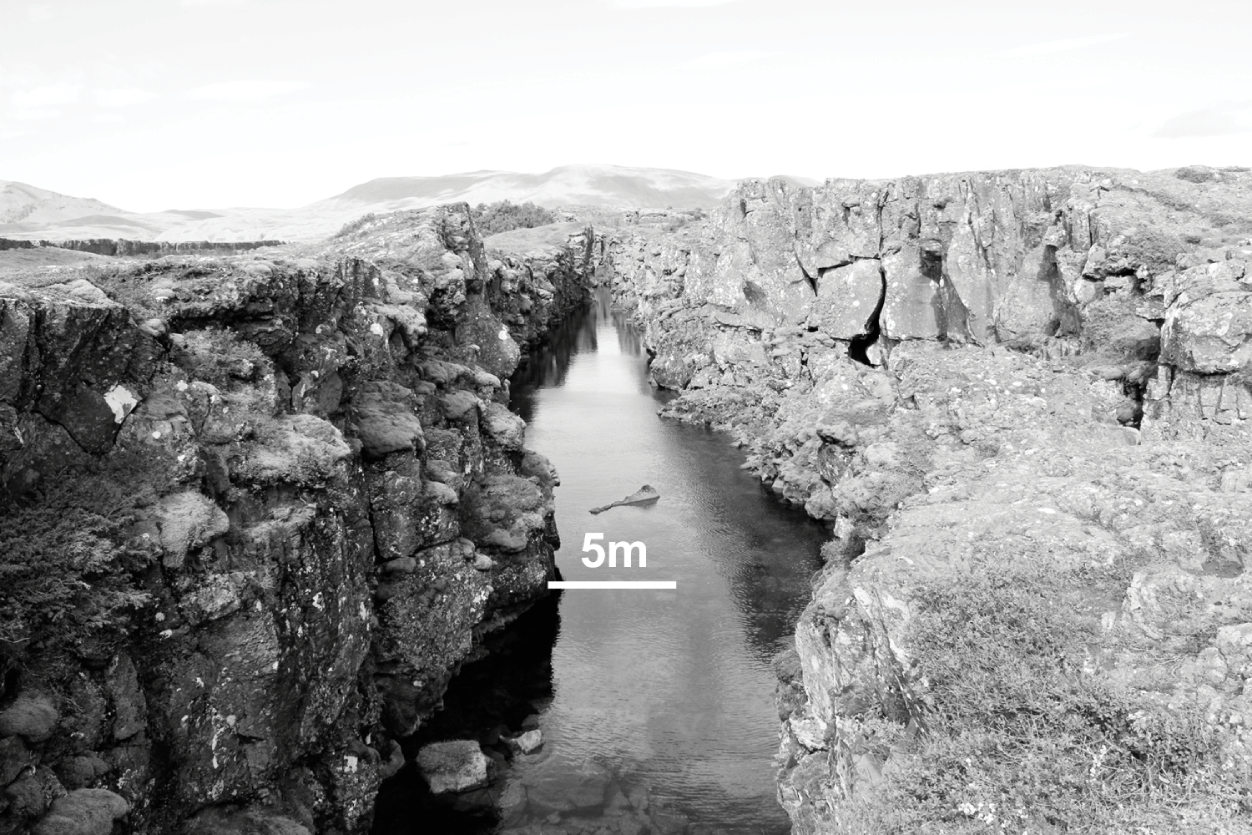

The aperture means simply the opening (usually the maximum or average opening) of a fracture. For an extension fracture, such as a tension fracture (Figs. 1.6 and 1.9) and a dike (Fig. 1.7), the aperture corresponds to the opening displacement and can be explained in terms of the theory of fracture mechanics (Chapter 5). For a shear fracture such as a fault (Figs. 1.5 and 1.10), however, the aperture has normally no relation to the displacement on the fault and cannot be forecast or explained in terms of the theory of fracture mechanics. Apertures of both extension fractures and shear fractures are important for understanding the permeability and general fluid transport in volcanoes, not only of magma but also of geothermal water (Fig. 1.8) and groundwater (Fig. 1.9).

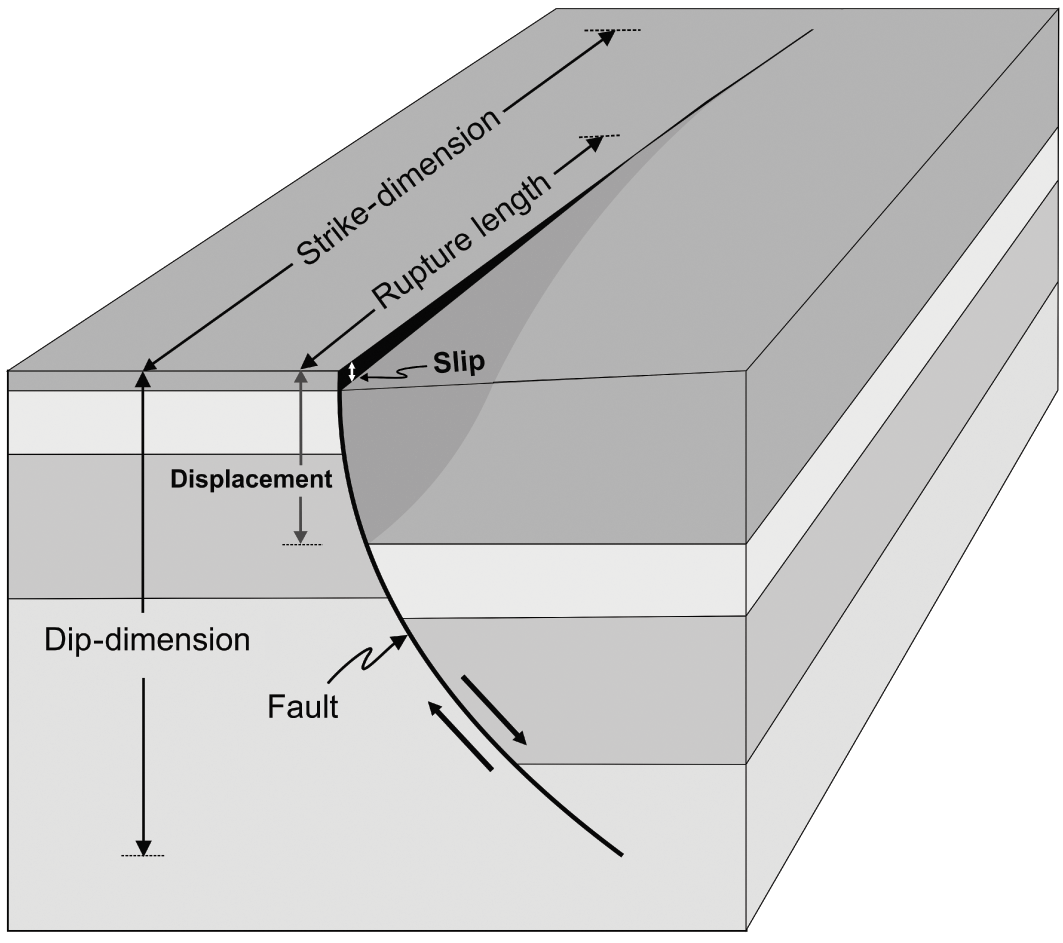

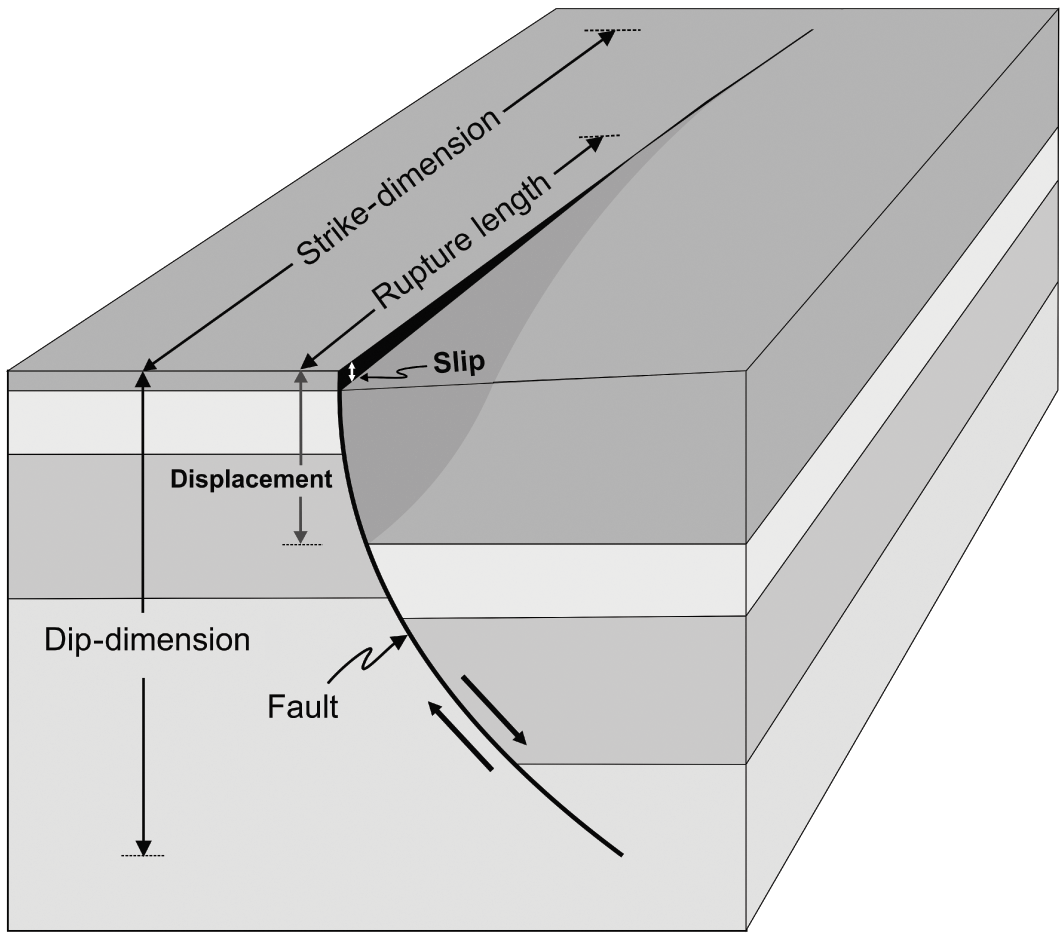

For faults and other shear fractures, the displacements can commonly be measured. Fault displacement is a measure of the relative movement of the fault walls. There are two main types of displacement measured in the field. One is the cumulative or total displacement, the other is the slip (Fig. 1.10).

The total fault displacement or just the fault displacement is the maximum (although some use the mean) relative fracture-parallel movement of the fracture walls. In this book, displacement is normally the total cumulative displacement; not the co-seismic slip in individual earthquakes.

The co-seismic fault slip or simply fault slip is the displacement associated with a single (earthquake) rupture. It is either measured at the surface, particularly for a large earthquake (many small earthquakes do not rupture the surface), inferred from the inversion of geodetic data, or both. The fault slip does not strictly have to be co-seismic; many faults and fault segments slip aseismically (creep), that is, without measured earthquakes – hence the parentheses around the word ‘earthquake’.

The fault length is the along-strike or strike-dimension of the fault/extension fracture, as seen at the surface (Figs. 1.5 and 1.10) or as inferred or calculated for the subsurface part of the fault from (mostly geodetic and seismic) data.

The fault width is the dip-dimension of the fault (Fig. 1.10) as observed in the field (for very small faults) or as inferred or calculated from (mostly geodetic and seismic) data. Notice that the use of the term ‘fault width’ in this sense is very common in seismology and earthquake mechanics, but less so in structural geology and tectonics where ‘width’ sometimes refers to fracture opening or thickness (of a dike). The latter use should be avoided. We do not speak about the ‘width’ of a lava flow when we mean its thickness; neither should we speak about the width of a dike when we mean its thickness.

The co-seismic rupture length, or simply rupture length (Fig. 1.10), refers to the strike-dimension of the part of an active fault (or fault zone) that ruptures during a particular slip and (commonly) an associated earthquake. The rupture length is normally much shorter than the total length of the fault/fault zone within which the rupture (and earthquake) occurs.

The co-seismic rupture width, or simply rupture width, refers to the dip-dimension (Fig. 1.10) of the part of an active fault (or fault zone) that slips during a particular (co-seismic) rupture. For large faults/fault zones, the total width is the thickness of the seismogenic layer (some 10–20 km at many plate boundaries). The rupture width of small to moderate earthquakes in large fault zones is normally much smaller than the total width of the fault/fault zone within which the rupture and earthquake occur.

The dike length normally refers to the strike-dimension of the dike (Fig. 1.11); the same applies to other extension fractures, such as tension fractures (Fig. 1.9) – length mostly means strike-dimension. When modelling fluid flow along a dike, the dike length can, however, refer to the distance from the source magma chamber to the surface. This distance may correspond neither to the strike-dimension nor the dip-dimension of the dike (Fig. 1.11). This difference in the meaning of the term ‘dike length’ is clear from the context and explained as such when needed.

The dike thickness is the thickness of the dike as measured directly (using a measuring tape) in the field (Fig. 1.7). Alternatively, the dike thickness may be (crudely) inferred from measurements made – during the dike emplacement – through geodetic (e.g. InSAR and GPS) techniques, such as are explained below.

The dike aperture is the opening of a magma-filled dike (cover photograph and Fig. 7.19). The aperture may be somewhat larger than the eventual thickness of the solidified dike, because the dike material contracts or shrinks as it solidifies. As indicated above, the shrinkage is normally about 10% or less, which is similar to common error estimates for dike-thickness measurements.

The controlling dimension, as used in fault/dike/tension fracture modelling, is the smaller one of the strike- and dip-dimensions. It is the dimension that largely controls the displacement on the fracture for given rock properties and driving stresses/pressures.

Fig. 1.5 (a) The attitude of a rock fracture is defined by its strike and dip. For a dip-slip fault like the one here (a normal fault) the wall above the fault plane is known as the hanging wall, whereas the wall below the fault plane is known as the footwall. The vertical displacement, here measured using a marker layer (a layer that is easily recognised on both sides of the fault plane), is known as throw and the horizontal displacement is known as heave. (b) Part of a normal fault in the Hengill Volcanic System of the rift zone in Southwest Iceland, with the strike and dip indicated schematically. When the horizontal black line (strike) is extended along the entire fault, it measures the fault strike-dimension. Similarly, when the black arrow (dip) is extended to the lower end of the fault (deep inside the crust), it measures the dip-dimension of the fault. View southwest, the normal fault forms the western boundary of the main graben of the rift zone in Southwest Iceland (Gudmundsson, Reference Gudmundsson2017). The strike and dip dimensions of the segmented fault are in the order of 10–20 km and the vertical displacement or throw about 200 m.

Fig.1.6 Extension fractures are of two main types: tension fractures and fluid-driven fractures, referred to as hydrofractures. This one is a tension fracture, with matching jogs and notches on the opposite fracture walls. The opening (displacement) or aperture is indicated by the white arrow. The diameter of the camera lens cap is about 6 cm.

Fig. 1.7 Dike thickness is measured as indicated by the black horizontal line. This dike, in the caldera wall of the island of Santorini, Greece, is about 1.5 m thick.

Fig. 1.8 Mineral vein of calcite in limestone in the Bristol Channel, Britain. The vein is multiple (composed of many thinner veins). The diameter of the camera lens cap is about 6 cm.

Fig.1.9 Tension fracture with the aperture (opening displacement) shown. The direction of the strike-dimension (the horizontal fracture length) is indicated. The maximum fracture opening is about 15 m.

Fig. 1.10 Illustration of some geometric parameters associated with active fault zones. Strike-dimension (length), dip-dimension (width or height), displacement (cumulative fault displacement), rupture length (co-seismic rupture length), and slip (co-seismic slip). Here the fault zone is a listric (curved) normal fault. The slip is recent and seen at the surface, while much of the cumulative displacement is buried (we are supposed to see into the uppermost part of the crust and thereby see the cumulative displacement). The recent fault slip adds to the earlier displacement, so that the displacement does not refer to the same marker layer in the footwall as in the hanging wall. The surface layer is much thicker in the hanging wall (right) of the fault zone than in its footwall (left). This difference is common in active volcanotectonic rift zones, where, for example, lava flows tend to become thicker in the hanging walls of normal faults (inside the graben if the fault forms a boundary of a graben). The approximate scale is so that the maximum displacement is about 100 m and the maximum slip is about 8 m. Only parts of the strike-dimension and the rupture length are shown. The rupture length is considerably shorter than the total length of the fault.

Fig. 1.11 Parts of the strike- and dip-dimensions of a well-exposed dike in the island of Santorini, Greece

1.5 Geophysical Techniques and Definitions

The significant improvement in monitoring volcanic unrest periods and eruptions in the past decades is largely attributable to the advancement in monitoring instrumentation, primarily geophysical techniques. All the standard geophysical methods are used for volcano monitoring. In addition, geochemical methods, such as monitoring changes in the chemistry and volumetric flow rates of fluids (gas, groundwater, streams), are routinely being used. While geochemistry is largely beyond the scope of this book, brief outlines are given of the main geochemical monitoring methods. More details on volcano deformation and seismicity and the associated techniques are provided in Chapter 3 and Chapter 4 as well as by Zobin (Reference Zobin2003), Dzurisin (Reference Dzurisin2006), Janssen (Reference Janssen2008), Segall (Reference Segall2010), and Lu and Dzurisin (Reference Lu and Dzurisin2014). What follows here is just a brief summary of some of the main techniques and definitions.

1.5.1 Volcano Deformation

When a volcano becomes subject to loading (stress, strain, pressure, or displacement) the rock units and layers constituting the volcano become deformed. The deformation is partly elastic, that is, it is recoverable once the loading is relaxed or removed (Chapter 3). Partly, however, the deformation is inelastic or permanent, that is, it results in the formation of fractures such as tension fractures, faults, and dikes. The permanent part of the deformation is not recoverable; when the load is relaxed the permanent part of the deformation is maintained, as discussed below. The most common large-scale deformation of active volcanoes is either inflation or deflation of the volcano (Fig. 1.12).

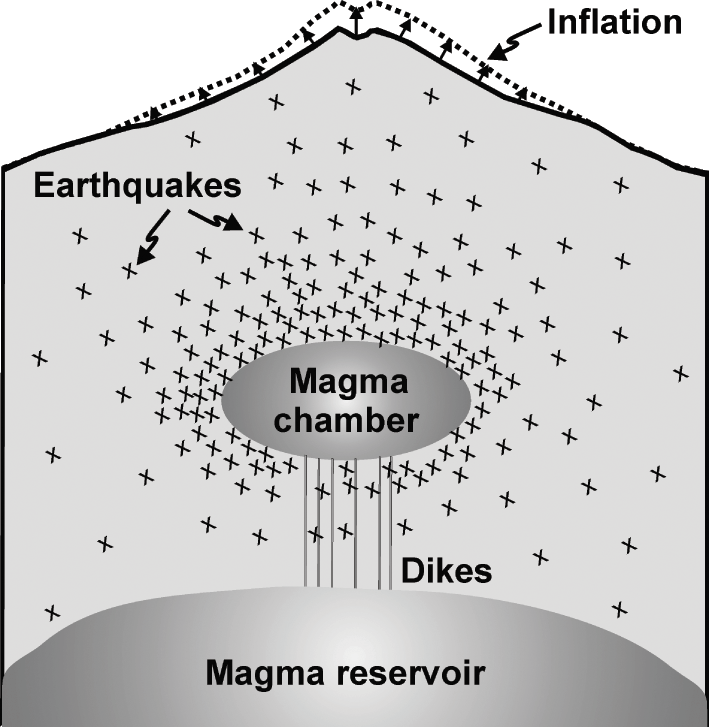

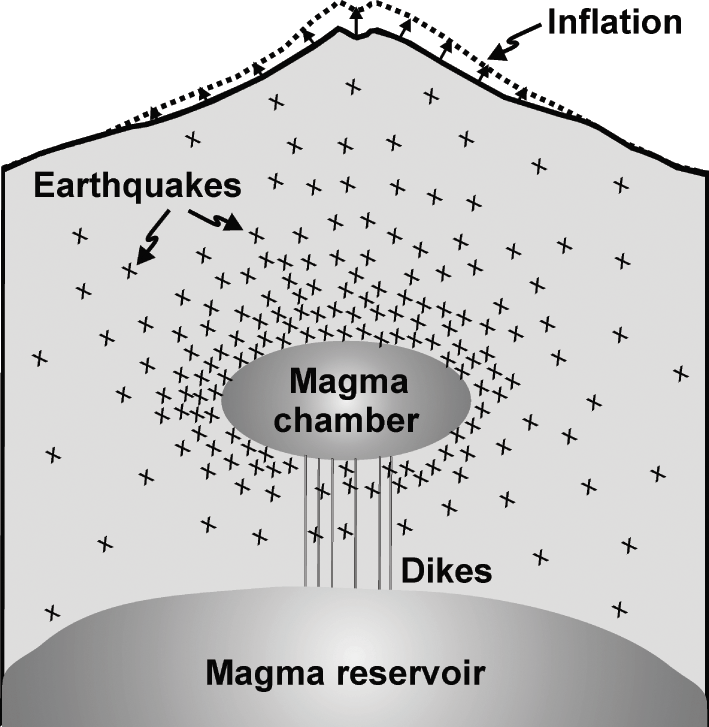

Fig. 1.12 Schematic illustration of an inflation (much exaggerated) and associated earthquakes (each cross indicates the location or focus of an earthquake). The inflation is due to magma-chamber expansion, which, in turn, is related to the shallow chamber receiving new magma (through dikes) from a deeper and much larger source reservoir.

Inflation refers to the uplift or doming of the surface of a volcano (or a volcanic system or a volcanic zone). Inflation is generally due to increased fluid pressure within the volcano (Fig. 1.12). The pressure increase may be related to the accumulation or expansion of water (increase in pore-fluid pressure), particularly geothermal water in a reservoir, but it is most often attributed to magma being added to the associated magma chamber (Fig. 1.12). Other causes of inflation include tectonic stresses, particularly when the volcano happens to be within an area of compression. Inflation is also a measure of the elastic energy (Chapters 7 and 10) stored in the volcano before eventual magma-chamber rupture, dike injection, and (sometimes) eruption.

Deflation refers to the lowering or subsidence of the surface of the volcano as the fluid pressure in the associated magma chamber (or other pressure sources) decreases. Subjecting the volcano to horizontal extension, such as commonly happens in volcanoes in rift zones, may also cause deflation. When the deflation is associated with a pressure decrease in the magma chamber, the standard interpretation is that magma has left the chamber. Normally, the magma leaving the chamber is injected as a dike (or an inclined sheet) into the host rock of the chamber (Figs. 1.2 and 1.11). It does not necessarily follow that the dike reaches the surface to feed an eruption; many, probably most, dike injections do not result in eruptions – the dike propagation stops, the dike becomes arrested, at some depth below the surface (Chapter 7). But the magma volume that goes into forming the dike and, if the dike reaches the surface, sustaining the eruption results in a decreasing magma volume in the chamber and thus in a pressure decrease, magma-chamber contraction or shrinkage, and deflation. Even if there is a magma flow from a deeper reservoir into the shallow chamber at the same time (Fig. 1.12), the inflow is normally at a much lower rate than the outflow through the dike and cannot sustain the pressure in the chamber, hence the deflation.

The crustal deformation associated with inflation and deflation is, to a large degree, elastic and thus essentially recoverable (Chapter 3). However, part of the deformation, particularly during inflation and dike injection, is permanent. The permanent deformation, sometimes referred to as plastic or inelastic, is exemplified by dikes, inclined sheets, and sills as well as by faults (primarily normal faults and grabens but also strike-slip faults), tension fractures, and volcanic fissures, as are commonly seen at the surface of the volcano. Large-scale inelastic deformation can be studied by the structural geological methods and techniques discussed above. On currently active volcanoes, crustal deformation, both elastic and inelastic, can also be studied by various geophysical methods, some of which are briefly described below.

Volcanic unrest (sometimes called volcano unrest) is the general name used for an increase in various detected geophysical, geochemical, and geological signals indicating changes in the rates or styles of associated physical processes within the volcano. Common signals are changes in seismicity, ground deformation (inflation/deflation), emission of volcanic gases (fumarole activity), flow and chemistry of groundwater and geothermal water, melting of snow/ice, and magnetic and gravity fields. Volcanic unrest is often partly caused by new magma being injected into the magma chamber of the volcano (Fig. 1.12), resulting in its expansion and volcano inflation. The unrest may result in magma-chamber rupture and dike injection, but most unrest periods do not result in a volcanic eruption.

1.5.2 Geophysical Techniques

The main geophysical techniques and methods used to monitor volcanoes are volcano seismology and ground deformation or geodetic studies. Volcanoes and their unrests are also monitored using geochemical methods, such as through gas and hydrological monitoring, as well as gravimetric and magnetic studies. These latter are outside the scope of the book, but geochemical monitoring is briefly discussed for the sake of completeness.

Volcano Seismicity Monitoring

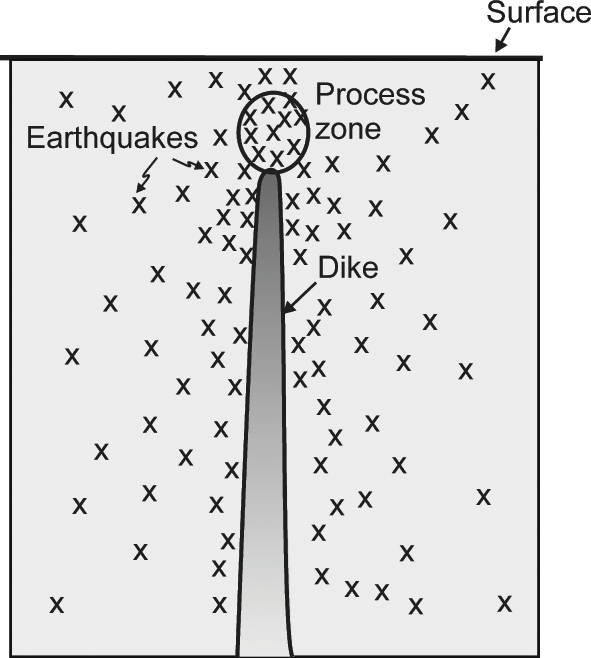

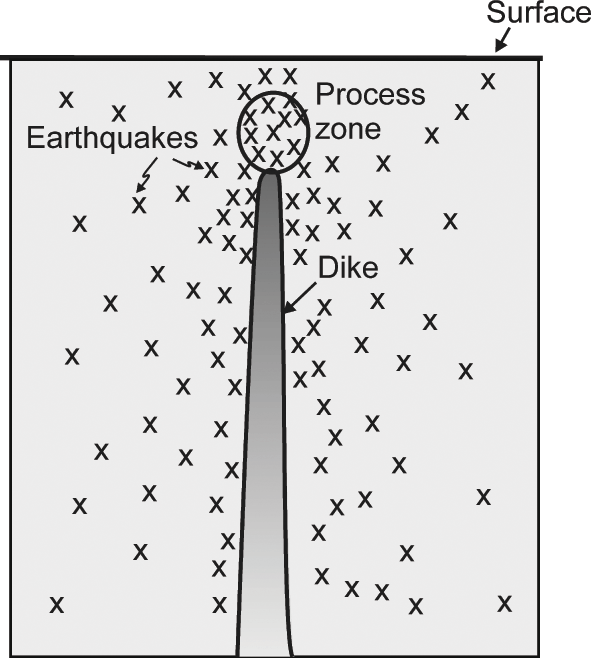

When the magma pressure in a chamber increases, the local stresses in the volcano also change and generally increase, resulting in earthquakes. The seismicity is normally widely distributed within the volcano, but tends to be most concentrated around the magma chamber (Fig. 1.12). When, however, the magma chamber ruptures and a dike (or an inclined sheet) is injected and begins to propagate up into the roof of the chamber, the seismicity becomes more local, generating a swarm that can often be used to trace the propagation of the dike within the volcano (Fig. 1.13; Chapter 4). Many of the dike-induced earthquakes occur at and above the propagating tip of the dike, whereas others – presumably the majority – occur along existing fractures and weaknesses (joints, faults, contacts) in the host rock on either side of the dike. Volcanic gases also increase the fluid pressure within certain parts of the volcano, namely along the paths of the migrating gases; the increased pore-fluid pressure commonly triggers earthquakes.

Fig. 1.13 Schematic illustration of the distribution of induced earthquakes (indicated by crosses) around a propagating dike. The process zone, indicated schematically by an ellipse above the tip of the dike, is where the most intense microfracturing and, partly, plastic deformation takes place during the dike (or any fracture) propagation.

Seismometers are employed for detecting and monitoring the earthquakes. Commonly, during unrest periods, many seismometers are installed on the volcano and in the surrounding area. The seismic network thus established allows the typically small earthquakes associated with the inflation and dike propagation to be detected and their focal mechanisms determined. Volcanic earthquakes are normally small, mostly less than magnitude M3.

The earthquakes can often be used to determine the depth to the magma chamber, and also the depth to a propagating dike (Figs. 1.12 and 1.13). If, eventually, the dike reaches the surface, or close to it, there will be a volcanic tremor (Chapter 4). The tremor is related to low-frequency earthquakes, generated during continuous vibration or shaking of the ground and thought to be caused by subsurface movement of magma and gas. While a tremor is generally accepted as an indication of an imminent eruption, some tremors occur without an eruption eventually happening. Thus, when a volcanic tremor happens there is a high likelihood, but no certainty, of an eruption.

Ground-Deformation Monitoring

Besides monitoring volcano seismicity, measuring the ground deformation is today perhaps the most commonly used technique for monitoring active volcanoes. There has been great progress in this technique in the past decades, primarily through the use of satellites that provide data for GPS and InSAR techniques (the acronyms are explained below). In addition, there are various other ground-deformation methods used, such as levelling, tiltmeters, electronic distance meters, and strainmeters. These techniques are also used to monitor active fault zones as well as to general plate movements – topics that are largely outside the scope of this book.

GPS stands for Global Positioning System, which is composed of a total of 32 satellites orbiting the Earth at a distance of about 20 200 km above the surface. The system was developed by the United States Department of Defense, but is currently used for many purposes, including monitoring and measuring volcanic and earthquake deformation. Using five–eight satellites in view (anywhere from the Earth’s surface), the position of measurement points or benchmarks (metal nails fastened into the surface of solid rocks, such as outcrops at the surface of a volcano) can be estimated very accurately. For maximum accuracy, where changes in position (displacements) of the benchmarks are of the order of centimetres or less, data are collected from the satellites over periods of 8–24 hours. Using various corrections (such as for atmospheric delay of the signals from the satellites), the measurements provide means of detecting slight inflations and deflations of volcanoes. From these it is possible to infer whether magma (or other fluids) are accumulating and building up pressure within the magma chamber of the volcano or, alternatively, leaving the magma chamber (through a dike), thereby decreasing the pressure. The latter is common, for example, during lateral dike propagations, many of which do not result in eruptions.

InSAR stands for Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar and is a technique used worldwide to measure surface deformation, such as on volcanoes and in earthquakes zones, but also general ground subsidence and ice flow, among other processes. As the name implies, it is a radar technique where use is made of synthetic aperture radar images to map the surface deformation. The basic data are derived from the difference in the known phase of the wave or signal sent by the satellite (the outgoing wave) and the phase of the return wave or signal, reflected from the Earth’s surface. Like GPS data, InSAR data can be used to measure surface deformation as small as centimetres, over periods from days to years, in volcanoes and earthquake zones.

Strainmeters are also used for monitoring volcanic (and earthquake) deformation. All these meters measure strain, that is, changes in a dimension such as length divided by the original dimension. The measured strain therefore has no unit (Chapter 3). For surface deformation, the most common strainmeter is an extensometer, where the changes in the distance between two points are measured and divided by the original distance. There are various types of these meters, which use either optical methods or the stretching of wire to measure the change in distance. The simplest meters, however, use metal rods, such as have been used to measure the dilation or extension across fractures during rifting events. Fluid-filled boreholes (wells) are also sensitive strainmeters. When they are subject to compression, the water level in the wells rises, and when subject to extension, the water level falls. These have been particularly useful in active seismic areas, which often contain numerous groundwater or geothermal wells.

Tiltmeters (also known as inclinometers) are useful for measuring the surface deformation of volcanoes. Tiltmeters measure very small changes in the slope angle of the free surface of the volcano at certain specific points. The tilts are measured in radians. Recall that a radian is equal numerically to an arc whose length is the same as the radius of the circle, and thus equal to an arc of about 57.3°. Because the tilts on volcanoes during inflation and deflation periods are usually very small, the measurements are normally given in microradians, that is, in units of 10–6 radians. One microradian is about 6 × 10–5 degrees. For tiltmeters on volcanoes, the smallest tilt that can be measured in a day is around 10–3 microradians.

Electronic distance meters are also used to monitor active volcanoes. These meters send and receive electromagnetic signals. By comparing the phase of the sent and received (reflected) signal, the changes in distances between points at the surface of the volcano can be measured with an accuracy of less than a centimetre. The distance changes can then be related to lateral and/or vertical displacements of the surface of the volcano.

Geochemical Techniques

Active volcanoes and their internal processes can also be monitored by geochemical methods, such as through gas and hydrological monitoring. Changes in gas composition or the rate of flow, primarily of CO2 (carbon dioxide) and SO2 (sulphur dioxide), from magma, is an indication of processes taking place inside the volcano. The gases can be measured directly on site, that is, at fumaroles or vents; or remotely, either from the ground or from aircrafts. Changes in the gas flux (the rate of flow of gas) can be interpreted as being related to changes in the volume of magma in its chamber and/or to changes in the associated geothermal system. Gas monitoring is currently routinely made on many active volcanoes.

There may also be changes in the chemistry of the springs and rivers associated with active volcanoes. These are commonly monitored; for example, in glacial rivers associated with some active (largely ice-covered) volcanoes in Iceland.

1.6 Interpreting the Data

1.6.1 General Interpretation

The first aim of volcanotectonic data collection is to provide information for developing a theoretical framework for understanding volcano behaviour. Such an understanding is a necessary condition so as to be able to forecast with any accuracy what is likely to happen during an unrest period. A second aim is to test existing or new theoretical models, the cornerstones of the theoretical framework, on volcanotectonic processes in volcanoes. Here, field data, primarily structural and geophysical, play a crucial role. It is easy to come up with ideas or conceptual models on volcanotectonic processes and principles. But to be useful in the sense of advancing our understanding of the real processes, the ideas must be testable, that is, make some predictions or forecasts that can be checked against existing or, preferably, new data.

Data analysis involves all the standard statistical techniques and modes of presentation used in structural geology and tectonics. These include histograms, rose diagrams, and stereoplots of the strike and dip (attitude) of the measured structures, particularly faults, dikes, inclined sheets, volcanic fissures (for which dip measurements do not normally exist), and tension fractures and joints (Chapter 2), as well as histograms/bin plots of dimensions and displacements (for faults) and thicknesses and other dimensions (for dikes).

For an earthquake, the focus or hypocentre and the focal mechanism or fault-plane solution (for earthquakes occurring on faults) are normally calculated and analysed (Chapter 4). The focus is simply the site or place within the crustal segment (or the volcano) where the fault rupture begins. The focus thus indicates the site of earthquake nucleation and initiation, which is normally the location of the greatest shear-stress (and strain) concentration prior to the earthquake. Focal mechanisms indicate the type of fault that generates the earthquake, that is, whether the earthquake occurs on a strike-slip or a dip-slip (normal, reverse, thrust) fault. Many earthquakes, of course, occur on faults that are oblique-slip, that is, partly strike-slip and partly dip-slip, and some may also have a large opening component (extension-fracture component). Such faults are referred to as mixed-mode (Gudmundsson, Reference Gudmundsson2011). Some earthquakes, particularly in volcanoes, are not generated by slip on faults but rather by vibration or shaking of the ground, such as in volcanic tremors. Earthquakes related to slip on faults (as most are) are also known as double-couple, whereas those that are not so formed are known as non-double-couple.

Geophysical deformation data are usually inverted so as to infer the depth to the main source or sources. The process is analogous to finding the ‘best fit’ to a data set on a plot using regression analysis, the best known of which is the linear regression. When the geodetic data are inverted the aim is to find the ‘best-fit source’ of the deformation. For a double-couple tectonic earthquake rupture, the source is a fault, whereas for volcano deformation the source is normally a magma chamber and/or a dike (or an inclined sheet or a sill).

The first thing to keep in mind when interpreting volcano deformation is that there are no unique solutions as regards the deformation sources (Chapter 3). Several sources with various geometries, fluid pressures, and depths in crustal segments whose mechanical properties are poorly known may fit the deformation data equally well. The second thing to keep in mind is that even when the ‘best-fit’ source has been selected, its physical characteristics (such as geometry, depth, fluid pressure) are normally poorly constrained.

As regards the lack of a unique solution, the similarity with fitting a line through data is instructive. For a reasonably large set of data points, an infinite number of functions can theoretically be fitted to the data. Well-known possible functions include various polynomials. One drawback of using polynomials as functions is that such a fit rarely has much physical meaning. That is, while the polynomial fit may be very good, its connection with the underlying physics of the processes that generate the data is commonly obscure or absent (cf. Hamming, Reference Hamming2004). Fourier series can also fit many data sets. The interpretation of such a fit in terms of physics of the processes producing the data is normally much better than for a polynomial fit.

We tend to choose straight lines to fit data, partly because of their perceived ‘simplicity’. There are, however, no accepted rigorous simplicity criteria for selecting functions that fit the data. Consider, for example, the following equations:

where a, b, and c are constants. Which of these two equations, both of which may fit the same data set, is the simpler one? Many would say that Eq. (1.1) is simpler because it is linear. Both equations contain the same number of terms, however, so that there is no clear-cut reason as to why Eq. (1.1) should be regarded as simpler than Eq. (1.2).

Coming back to the inversion of deformation data, there are many reasons why there are no unique solutions as regards the deformation sources. The main ones may be listed as follows:

Surface deformation data are essentially two-dimensional. This means that they are data in a plane or a surface. To infer a three-dimensional source such as a magma chamber or a dike from two-dimensional data cannot result in a unique solution. For example, the commonly used ‘Mogi model’, a nucleus of strain in an infinite elastic half-space (Chapter 3; Dzurisin, Reference Dzurisin2006; Segall, Reference Segall2010), cannot distinguish between the size and overpressure of the source magma chamber. Half-space models assume that the crustal segment is isotropic and homogeneous, that is, that it contains no layers with contacts and different mechanical properties.

The crustal segment hosting the volcano and its magma chamber, and the volcano itself, are composed of numerous layers, with contacts as well as faults and other discontinuities (Figs. 1.7 and 1.11; Chapter 7). The layers and contacts commonly have widely different mechanical properties, so that the stresses and strains (or displacements) in these layers vary widely, even when the loading, such as the magmatic overpressure in the associated shallow magma chamber, may be constant. When using simple elastic half-space models, the surface deformation thus commonly gives a poor indication of the actual geometry and depth of the source chamber (Chapters 3 and 10; Masterlark, Reference Masterlark2007).

The half-space models are also poor for determining the geometries and paths of injected dikes. Dikes commonly open up joints, contacts, and other discontinuities ahead of the dike tips, resulting in surface deformation and stresses that do not allow simple inversion of the geodetic data to determine the dike depth or geometry (Chapters 3, 7, and 10). Simple elastic dislocation models normally use uniform elastic properties for the entire elastic half-space. For a layered crust, the estimated dike thicknesses from such models may easily be in error of 50–100%.

While inversion models are, necessarily, inaccurate as to the determination of the depth and geometry of magma chambers and injected dikes and inclined sheets, they are currently the most widely used models we have for such determinations. One theme that will be explored in the book is how to improve our knowledge of the interiors of volcanoes so as to make our understanding of the real processes and structures that generate the surface deformation more reliable. We will briefly introduce these topics below (Section 1.6.3), but first we turn to a general classification and description of models, particularly those used in volcanotectonics.

1.6.2 Models

The interpretation and use of scientific data is normally through scientific models. Existing and new data are then used to construct, develop, and test the models. Generally, we make models to help us understand the natural processes or principles with which we are working. For example, in volcanotectonics we make various types of models to improve our understanding of the physical processes that happen inside volcanoes. In physical science in general, and in earth sciences in particular, there are five basic types of models, namely conceptual, statistical/probabilistic, analogue, analytical, and numerical. Let us now briefly describe and discuss the main characteristics of these models with application to earth sciences in general and volcanotectonics in particular.

1. Conceptual Models.

These are basically ideas about some structures or processes that are expressed through words, illustrations, or physical models. Examples include geological maps, cross-sections, and physical models of volcanoes (Fig. 1.14). Other examples include general sketches of geological structures and the processes that generate them.

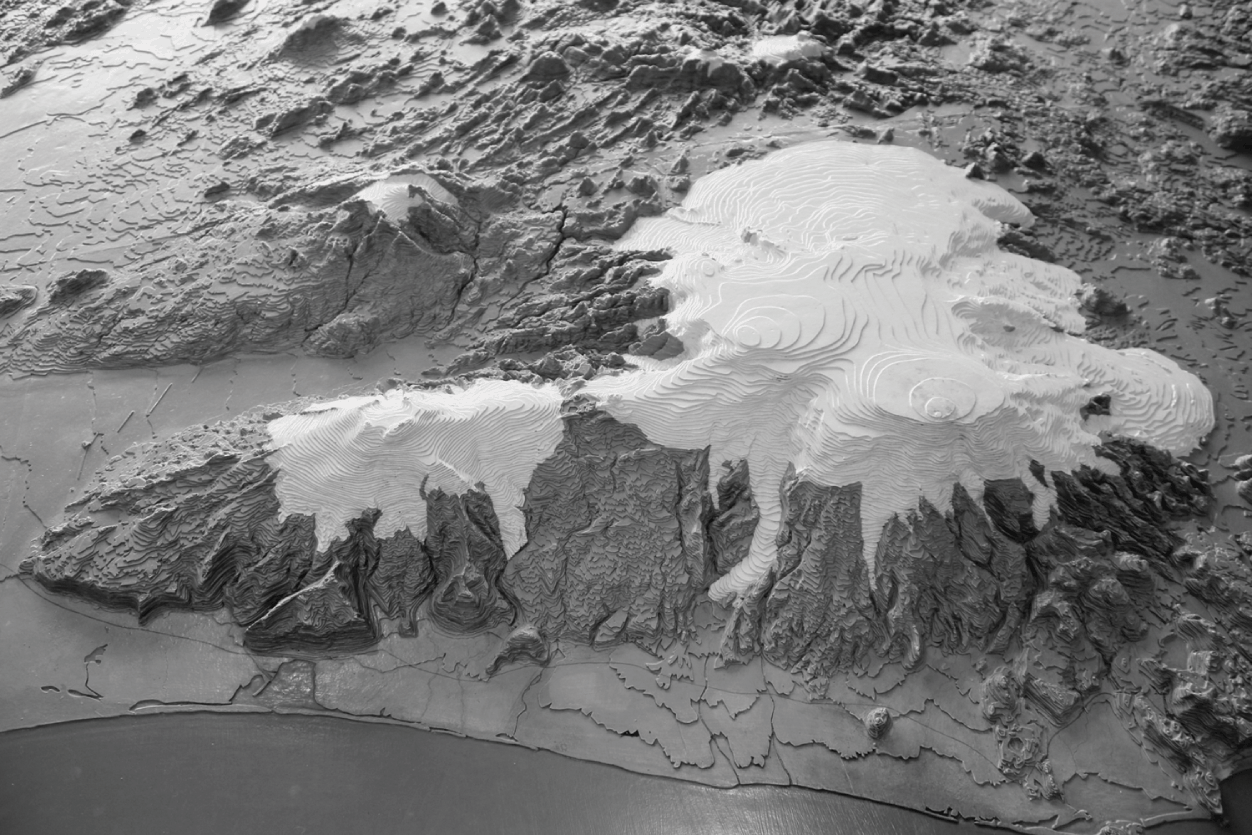

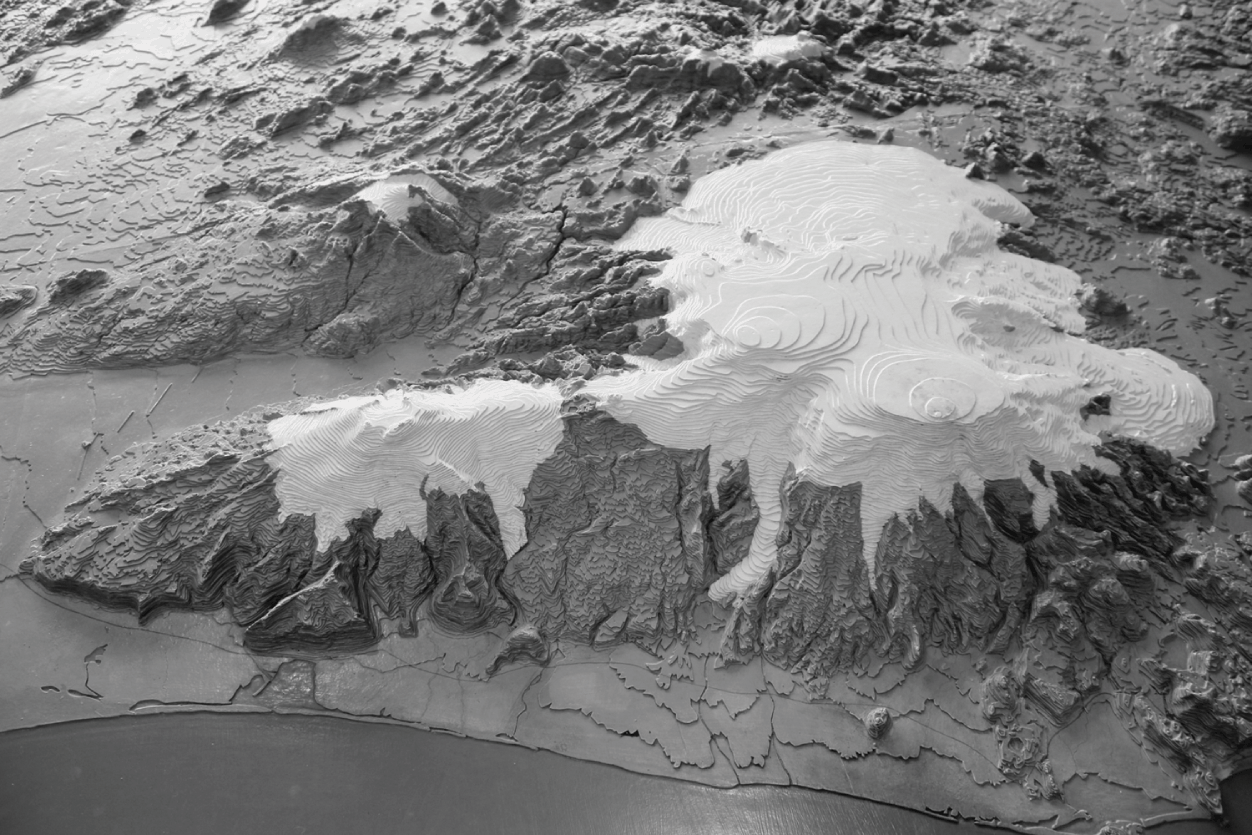

Fig.1.14 Physical model of the volcanoes Eyjafjallajökull (to the left, erupted in 2010) and Myrdalsjökull (to the right, erupted in 1955) in south Iceland. The main volcano in Myrdalsjökull is Katla. The white tops denote ice caps and glaciers. This is a part of a general physical model of Iceland in the City Hall of Reykjavik.

2. Statistical/Probabilistic Models.

As applied in volcanotectonics, these models indicate the likelihood that a randomly selected structure or event will have a certain value. For the strike or orientation of volcanic fissures in a particular volcanic zone or a single volcano, such a model would indicate the purely probabilistic likelihood that the fissure that formed during the next eruption would strike between, say, N20°E and N30°E. That likelihood would depend on the available data, using the frequency theory of probability. If we have additional information, such as the inferred state of stress in the volcano, its mechanical layering, and the location of the most recent volcanic fissure in the volcano/volcanic zone, then the Bayesian probability approach (Stone, Reference Stone2013) might be warranted. Similar models can be made of the likelihood of values falling within certain class limits or range, such as regarding the length of the next volcanic fissure, its number of crater cones, and so forth. These types of models apply to any types of fractures – including dikes, normal faults, and tension fractures (Chapter 2).

3. Analogue Models.

These are also referred to as scale models since they draw an analogy between small-scale processes or structures in the laboratory and large-scale processes or structures in nature. Among the earliest analogue models in tectonics were those that used wet clay under tension to develop fracture patterns similar to those seen in rift zones and grabens. In current analogue models, use is made of sand, powder, clay, silicone, jelly, or other materials which have properties that, through scaling factors, can be correlated with the materials (rocks, crustal fluids) which we want to model. Analogue models have been used extensively in volcanotectonics in recent years, primarily to model the emplacement of dikes and sills (Kavanagh et al., Reference Kavanagh, Menand and Sparks2006, Reference Kavanagh, Boutelier and Cruden2015; Menand et al., Reference Menand, Daniels and Benghiat2010; Daniels and Menand, Reference Daniels and Menand2015) as well as the formation of collapse calderas and related structures (Chapter 5).

4. Analytical Models.

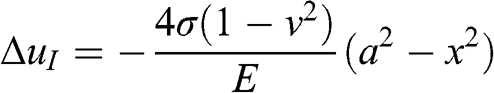

These are essentially equations or formulas that express certain relations between volcanotectonic parameters and constants, loading, and associated processes. For example, the variation in aperture (opening displacement), ΔuI, along the tension fracture in Fig. 1.9 can be modelled analytically as a mode I crack through the formula:

(1.3)

(1.3)

where σ is the tensile stress applied to the rift zone during fracture formation, ν is Poisson’s ratio, E is Young’s modulus, a is the half length (half strike-dimension) of the fracture which coincides with the x-axis of the coordinate system. The minus sign is because tensile stress is recognised as negative (compressive stress as positive) so that, in order to get a positive or zero aperture (ΔuI ≥ 0), as it should be, there must be a minus sign before the stress symbol (Chapter 3). In Eq. (1.3) it is assumed that the tension fracture is a through crack, that is, it extends from one free surface (rock surface in contact with fluid, for example air, water, or magma) to another free surface. There are many analytical volcanotectonic models presented in the book, some of which are derived and discussed in greater detail by Gudmundsson (Reference Gudmundsson2011). In analytical models we normally find the general solution to a problem ‘by hand’, although there are available several computer programs for finding analytical, closed-form solutions. Analytical models apply to many specific boundary conditions so that the effects of changes in the conditions can be evaluated to provide solutions at any point in the rock. However, analytical solutions can be found only for simple geometries and are normally restricted to small strains and essentially homogeneous and isotropic rock properties.

5. Numerical Models.

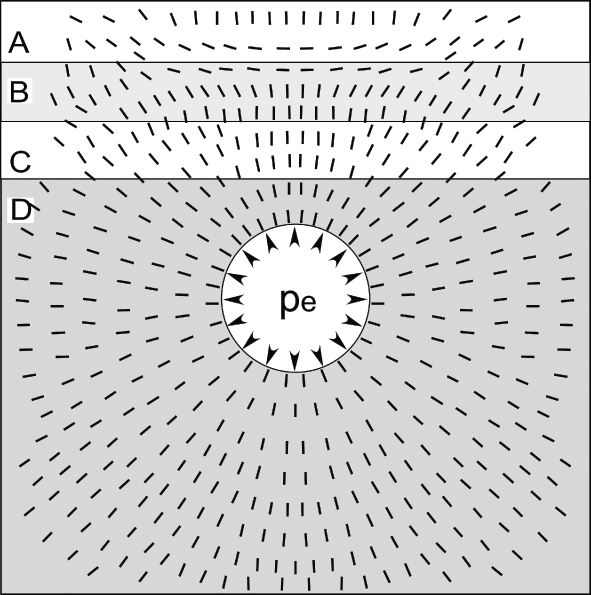

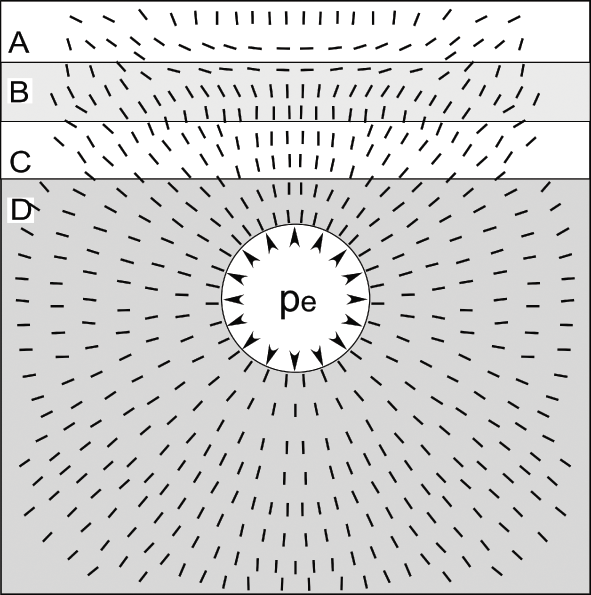

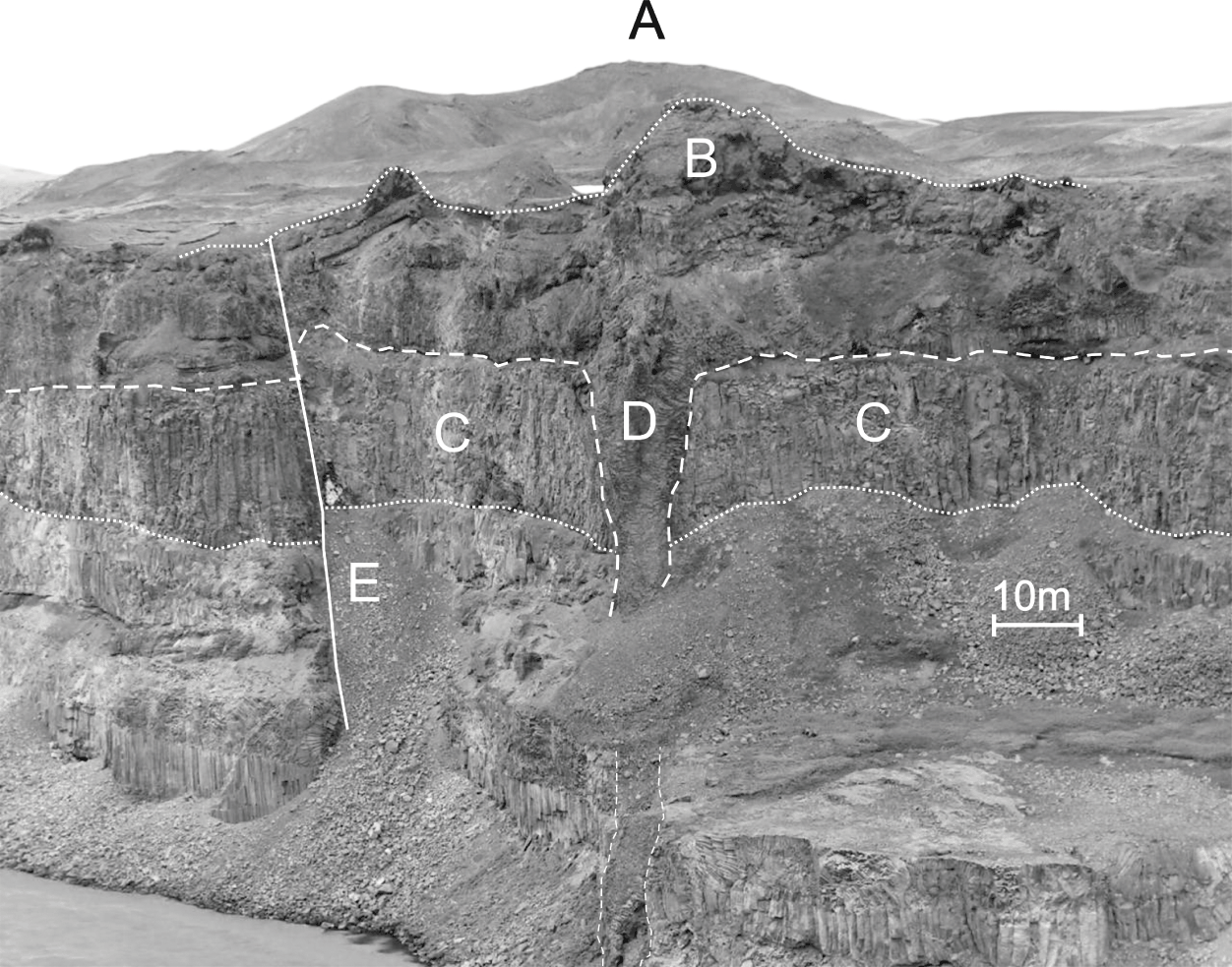

These are used for volcanotectonic structures and processes where the geometries, mechanical properties, and boundary conditions make the problem too complex or tedious to solve analytically. The volcanotectonic problem is then rewritten as mathematical statements that can be solved numerically. In numerical models we divide or ‘discretise’ the problem into an equivalent system of small units or ‘elements’, solve simultaneous algebraic equations (resulting in numerical approximations) for each element, and then combine them into a solution for the entire body or process under consideration (cf. Reddy, Reference Reddy2005; Deb, Reference Deb2006). These are specific solutions to a particular set of conditions and provide solutions only for the specified points in the body which may, for example, be a crustal segment or a collapse caldera. Numerical solutions can be found for any complex geometries and boundary conditions that we wish to analyse, and are particularly suitable for analysing large strains as well as bodies with heterogeneous and anisotropic mechanical properties. Numerical models, especially when presented as animations, are also referred to as numerical simulations. An example of a very simple numerical modelling result is the stress field around a magma chamber for given boundary conditions and host-rock properties (Fig. 1.15).

Fig. 1.15 Simple two-dimensional numerical model of the local stress field around a shallow magma chamber of a circular cross-section. The stress field is generated by an excess fluid pressure (pe), that is, pressure above the lithostatic pressure (Chapter 3) of 10 MPa in the magma chamber. Layer D has a stiffness or Young’s modulus of 10 GPa; layer C, 100 GPa; layer B, 1 GPa, and layer A, 100 GPa. The short lines (the ticks) show the directions (the trajectories) of the maximum compressive principal stress σ1, along which ideal sheet intrusions (dikes, inclined sheets, sills) injected from the chamber would propagate.

1.6.3 Improving the Models and Monitoring of Volcanoes

The fundamental aim of modelling volcanotectonic processes is to be able to forecast with accuracy the most likely course of events during unrest periods in volcanoes. Volcanic unrest normally includes some or all of the following factors and processes: inflation or deflation, earthquakes, changes in water wells and composition of the water in nearby rivers, as well as changes in gas flux (the rate of flow of gas). Given the sophisticated and dense networks of various geophysical and geochemical instruments on many active volcanoes, one might perhaps expect that we could routinely forecast how an unrest period is going to end – in particular, if it is going to result in an eruption – but normally we cannot. Here, I briefly explain this lack of success, and suggest ways to improve the present modelling and eruption forecasting methods. The points raised and discussed here are elaborated in the subsequent chapters of the book.

All scientific models, including those in volcanotectonics, aim at providing results that improve our understanding of the world and allow us to forecast events. In volcanotectonics, the events of concern include large landslides (lateral collapses, Chapter 5), caldera formation (vertical collapses, Chapter 5), volcanotectonic deformation (Chapter 3), volcanic earthquakes (Chapter 4), and eruptions (Chapters 7, 8, and 10). The forecasts can be either deterministic or probabilistic. Deterministic forecasts specify the location, time, and magnitude of an event, whereas probabilistic forecasts specify the probability of these parameters within certain ranges. In much of classical physics and derived engineering fields, deterministic forecasting is the rule and has been very successful. Modern physics, however, is largely statistical in nature (quantum mechanics, statistical mechanics), and so are most scientific fields that deal with complex structures and large numbers of entities where stochastic (random) elements play a significant part in processes and events. The same applies to volcanotectonics. Not only are the internal structures and properties of volcanoes complex, but there are always stochastic elements that play a role in the unrest periods, making probabilistic forecasting the only viable method.

So how can we refine our volcanotectonic models with a view to improving the reliability of forecasts? There are several aspects that should and could be bettered at this stage, including the following:

1. Use numerical models rather than the nucleus-of-strain models (such as the Mogi model). This follows because the nucleus-of-strain models assume homogeneous, isotropic elastic half-spaces and therefore can never provide accurate depth estimates of the sources (magma chambers). Furthermore, the nucleus-of-strain models cannot distinguish between the size of the source and its internal fluid (magma) overpressure. And these models provide no information about the state of stress in the host rock. Nucleus-of-strain models thus cannot be used to infer the likely paths of injected dikes, their chances of reaching the surface as feeders, or the likelihood of lateral or vertical collapses during unrest. By contrast, as is discussed in later chapters, numerical models can, provided the appropriate data are available, determine reasonably accurately the likely depth, size, and shape of the source, the state of stress in the host rock, and the likely paths of injected dikes following magma-chamber rupture.

2. Take the heterogeneity and anisotropy of the volcano and the hosting crustal segment into account. This implies using mechanical layering in the models. There are a lot of data available on mechanical layering in volcanoes through drilling and direct field observations (Fig. 1.16). Taking layering into account refines the models in two principal ways. First, the interpreted surface deformation then reflects much more accurately the depth, size, and shape of the source (a chamber or a dike, for example). Second, reasonably accurate forecasts as to likely paths of injected dikes (or inclined sheets or sills) during the unrest period depend on taking layering into account. This has been demonstrated in many eruptions in well-monitored volcanoes such as in the 2010 Eyjafjallajökull eruption in Iceland (Sigmundsson et al., Reference Sigmundsson, Hreinsdottir and Hooper2010; Gudmundsson et al., Reference Gudmundsson, Thordarson and Hoskuldsson2012), the 2011 El Hierro eruption in the Canary Islands, Spain (Becerril et al., Reference Becerril, Galindo, Gudmundsson and Morales2013; Marti et al., Reference Marti, Pinel and Lopez2013), the 2013 eruption in Etna, Italy (Falsaperla and Neri, Reference Falsaperla and Neri2015), and the Bardarbunga 2014–2015 eruption in Iceland (Gudmundsson et al., Reference Gudmundsson, Lecoeur, Mohajeri and Thordarson2014; Sigmundsson et al., Reference Sigmundsson, Hooper and Hreinsdottir2015). In all these eruptions, the comparatively complex paths of the feeder-dikes were partly the result of the heterogeneity and anisotropy (mainly layering) of the volcano and the hosting crustal segment.

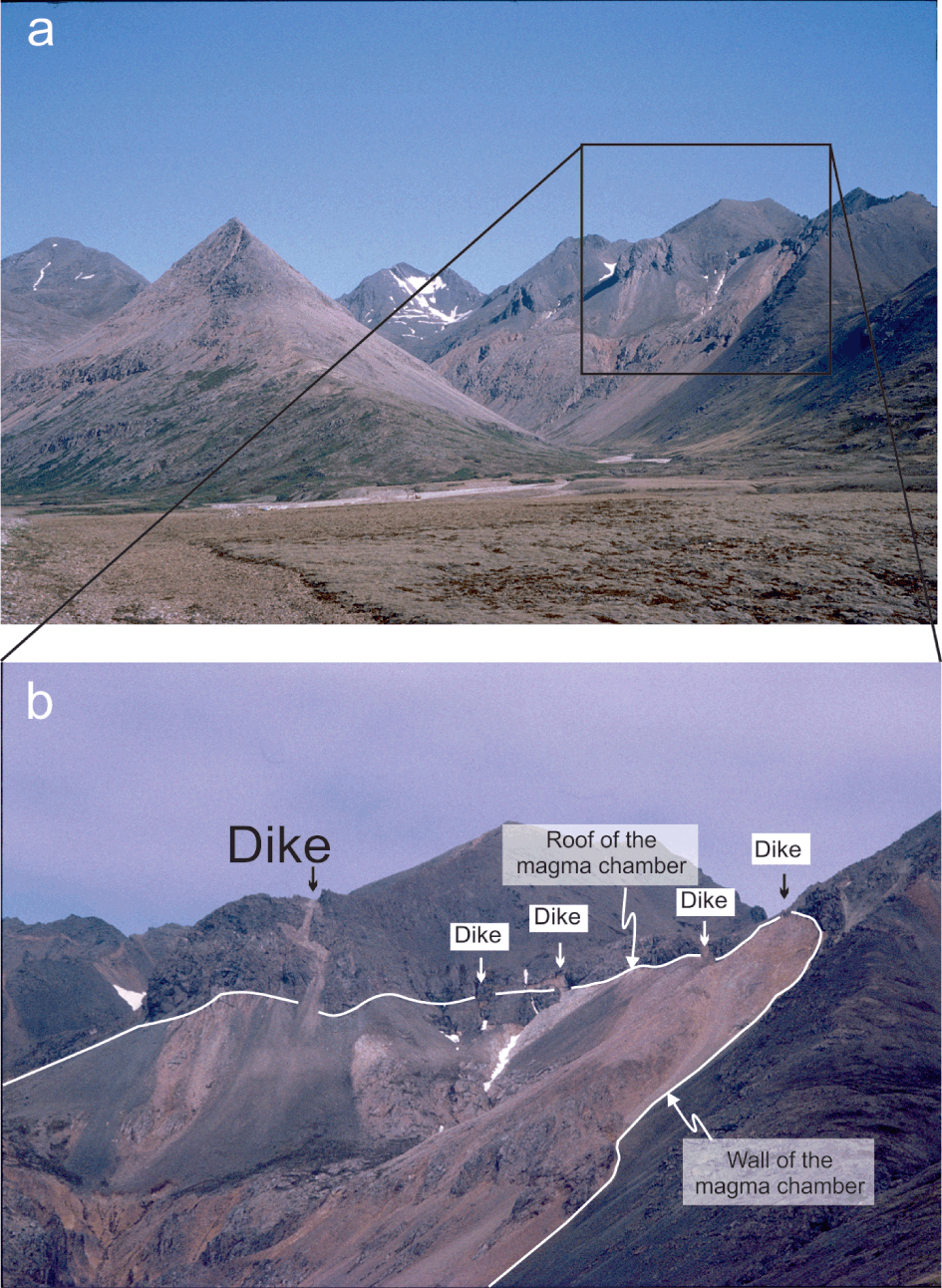

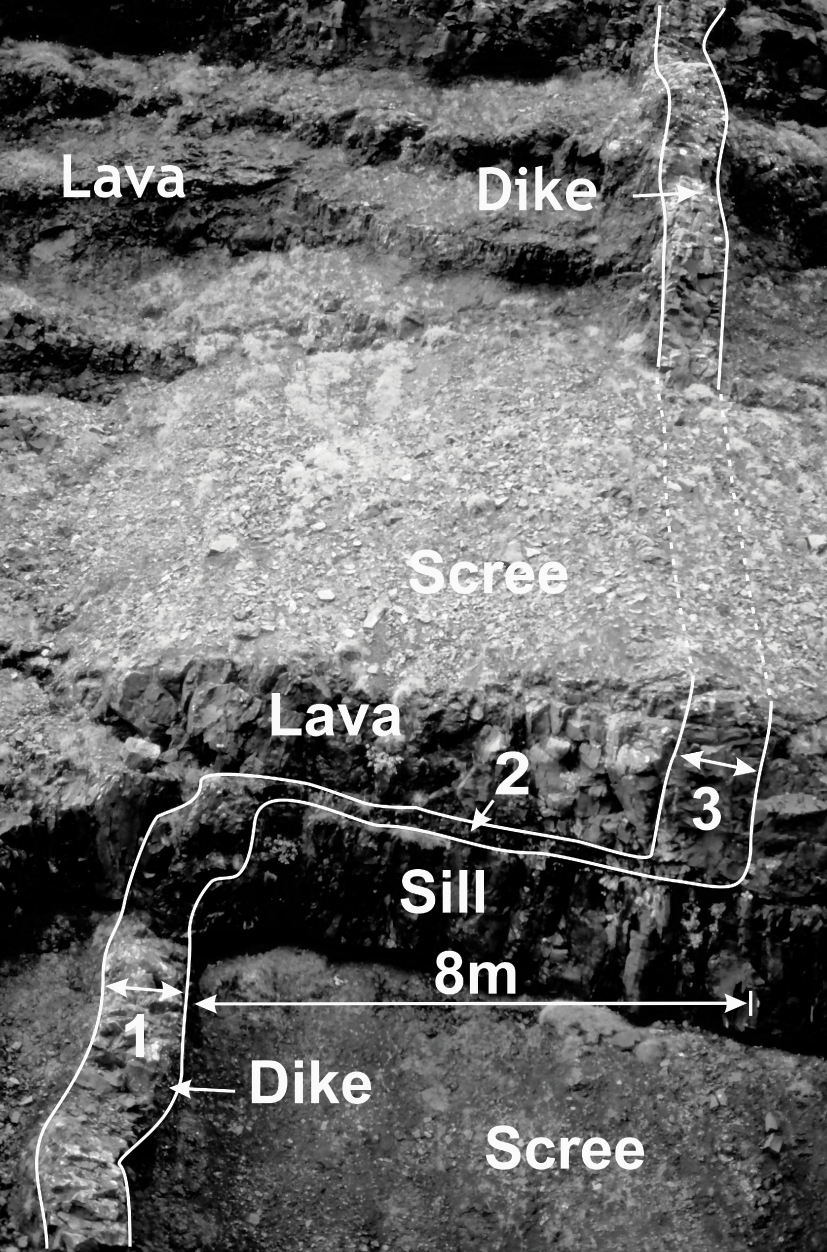

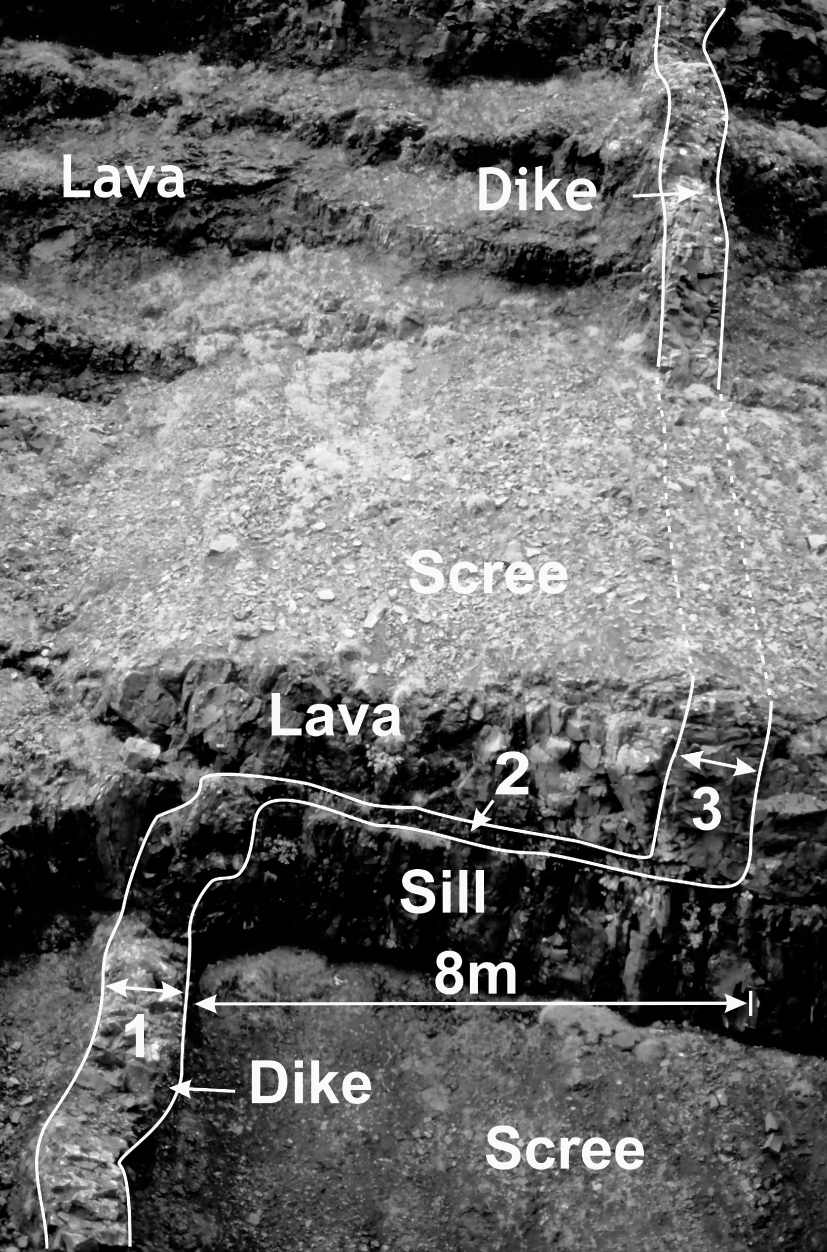

3. Use data on the geometry of fossil magma chambers and dikes, inclined sheets, and sills in eroded volcanoes to provide constraints on typical and likely geometries of chambers and paths of sheet-like intrusions. Some fossil magma chambers are particularly well exposed, so well, in fact, that the roof and the dikes dissecting the roof can be explored in great detail (Fig. 1.17). Similarly, many dikes can be traced in the field (Fig. 1.18), thereby providing constraints on and an understanding of the dike paths that can be inferred from earthquake swarms and deformation during unrest periods in active volcanoes. Vertical dikes are commonly seen to change into inclined sheets or horizontal sills along parts of their paths. In addition, dikes, sheets, and sills show great variations in thicknesses along their paths, commonly being thicker where dissecting soft (low Young’s modulus or compliant) layers than when dissecting stiff (high Young’s modulus) layers (Chapter 2; Geshi et al., Reference Geshi, Kusumoto and Gudmundsson2010). Data on actual dike paths should be incorporated into the numerical models used to interpret the surface deformation during unrest periods, as well as the models on the seismicity associated with the dike propagation.

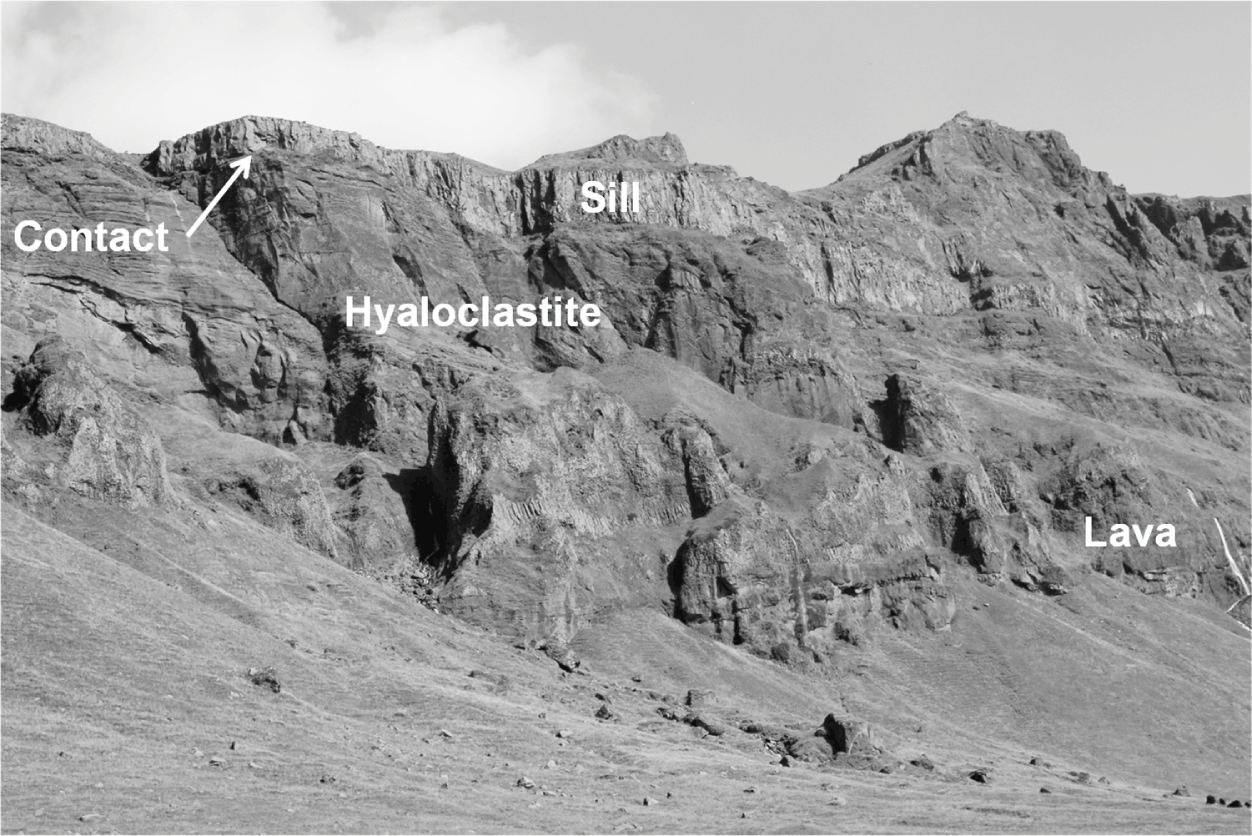

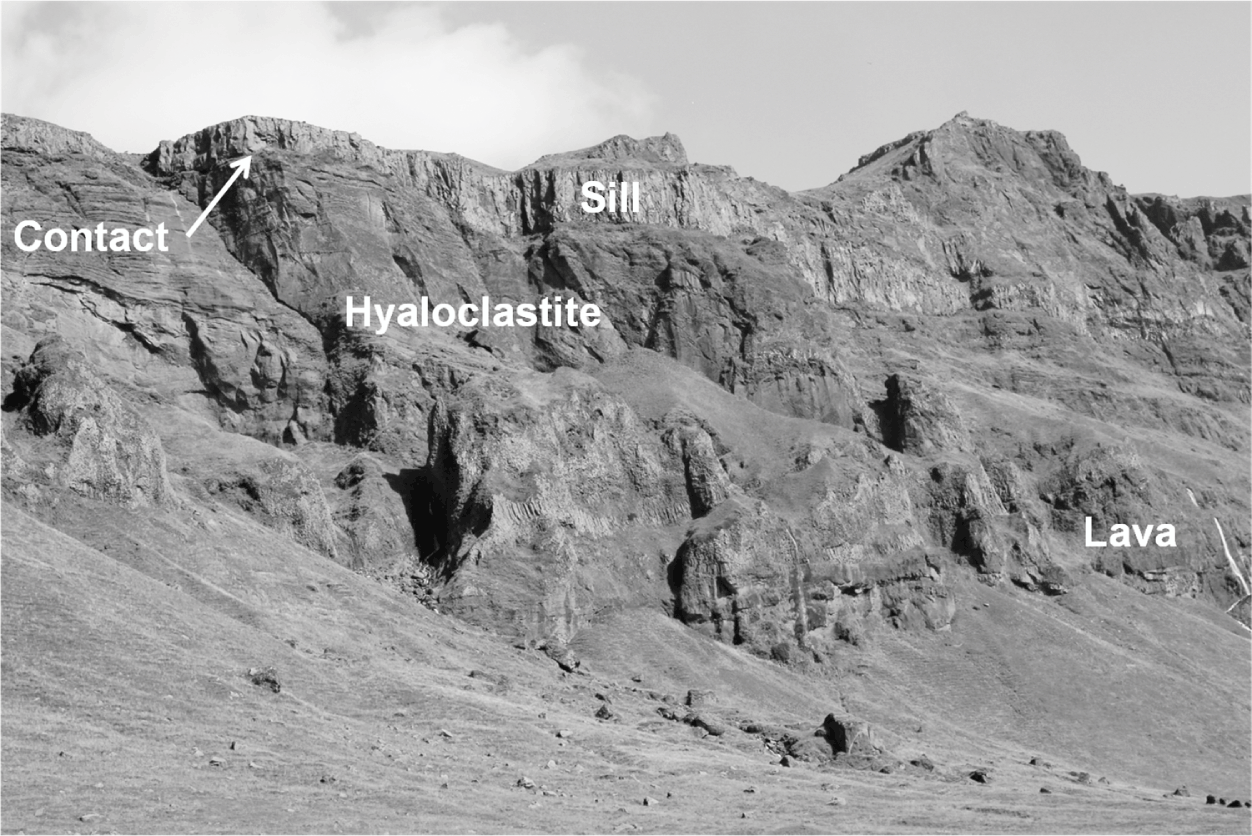

Fig. 1.16 South slopes of the volcano Eyjafjallajökull in South Iceland (Fig. 1.14) are composed of a variety of layers with different mechanical properties. During the 2010 eruption of Eyjafjallajökull, several sills, presumably similar to the one seen here, were emplaced at great depths within the volcano.

Fig. 1.17 Part of the exceptionally well-exposed fossil shallow magma chamber (now a pluton) of Slaufrudalur in Southeast Iceland (located in Fig. 3.15). The walls and the roof of the chamber are exposed, and many dikes (as extension fractures) cut the roof. The pluton is made of granophyre and is hosted by a pile of basaltic lava flows.

Fig. 1.18 Deflection of a dike into a sill along part of its path. The deflection occurs at the contact between mechanically dissimilar rocks, with the contact itself being composed of scoria. The vertical dike (1) changes into a thin sill for about 8 m (2), and then back to vertical dike (3).

1.7 Summary

An active volcano is a vent through which magma and volatiles are transported to the Earth’s surface. The volcanic materials around the vent pile up into a small volcano – a crater cone, normally a cinder/scoria cone or a spatter cone. During many eruptions through one or many nearby vents, the erupted material builds up into a volcanic edifice, most commonly a stratovolcano or a basaltic edifice.

An active volcano is commonly defined as one that has erupted at least once during the Holocene, that is, during the past 11 700 years. This definition should be treated with caution, however. There are many volcanoes, particularly large collapse calderas, which have not erupted for tens of thousands of years but are still active and need to be monitored. Generally, a volcano is potentially active so long as it has a chance of receiving magma from a source.

A volcano that is thought to be unable to erupt is regarded as extinct or fossil. When a fossil volcano is also deeply eroded, its fossil shallow magma chamber (or, at least, its top part), a pluton, is commonly exposed.

Volcanotectonics is the scientific field that combines tectonics, structural geology, volcanology, geodesy, and seismology with theories from classical physics and their modern extensions (including rock mechanics and fracture mechanics) to analyse and interpret processes in active and fossil volcanoes. More specifically, volcanotectonic studies include collecting tectonic, rock-physical, geodetic, seismic, and stress data from active and fossil volcanoes. These data are then interpreted, using particular theories from physics, to provide reliable deterministic and probabilistic models (as in statistical physics) for understanding processes inside volcanoes and for forecasting scenarios and events at active volcanoes.

Tectonic and structural-geology techniques used in volcanotectonics include all the standard methods such as measurements of strike, dip, length, aperture, and displacement of tension fractures and faults, as well as the thicknesses and other dimensions of dikes, sheets, and sills.

Geophysical techniques used in volcanotectonics include measurements of volcano deformation (inflation, deflation) and seismicity using methods/equipment such as GPS, InSAR, strainmeters, tiltmeters, distance meters, and seismometers. The data are inverted using standard statistical techniques; for example, to infer the dimensions and location of a subsurface fault, or the dimensions and location of an active magma chamber.

For understanding, interpreting, and forecasting volcanotectonic processes and events, including eruptions, models are used. The basic types of models are conceptual, statistical/probabilistic, analogue, analytical, and numerical.

1.8 Main Symbols Used

1.9 Worked Examples

Problem

The fracture in Fig. 1.19 is at the surface of Holocene lava flow in a rift-zone volcanic system in Iceland.

(a) What type of fracture is this?

(b) Estimate the aperture of the fracture.

(c) If its strike-dimension (length) is 600 m, the dip-dimension or depth 300 m, and the fracture is located in a 20-km-thick crustal segment, which would be its controlling dimension?

Fig. 1.19 Tension fracture in the Holocene lava flows of the rift zone in Southwest Iceland.

Solution

(a) The type of fracture is an extension fracture. This follows because the only displacement is an opening (there is no apparent fracture-parallel movement of the walls). More specifically, since the fracture is at the surface of a Holocene lava flow in a rift zone and shows no evidence of being formed as a result of internal fluid pressure, it is classified as a tension fracture.

(b) Using the scale provided on the photograph, the aperture or opening of the tension fracture is about 10 m.

(c) Since the dip-dimension is smaller than the strike-dimension and the fracture does not extend through the entire crustal segment, the controlling dimension is the dip-dimension. The controlling dimension is the one that mainly controls the displacement on a fracture, here the opening displacement (the aperture).

Problem

The orthogonal structures in Fig. 1.20 dissect a pile of Tertiary (Neogene) lava flows in Iceland.

(a) What are the general geological names of the structures/fractures?

(b) To which mechanical types of fracture do the structures belong?

(c) Which of the fractures is the youngest one?

(d) What are the thicknesses of the structures?

(e) How do the measured thicknesses of the structures relate to the original apertures of the fractures?

Fig. 1.20 Orthogonal structures/fractures dissecting the Tertiary lava pile in southeast Iceland.

Solution

(a) The vertical structure on the photograph is a dike, the horizontal structure a sill (or, possibly, an inclined sheet, depending on the dip, which cannot be inferred from the photograph).

(b) Both dikes and sills are extension fractures. Since they are driven open by magma pressure, that is, the pressure of the magma breaks or ruptures, the host rock, dikes, and sills are the type of extension fracture referred to as hydrofractures.

(c) The sill clearly dissects (cuts through) the dike and is therefore the younger fracture. The dike is thus the older fracture.

(d) Using the person (about 1.7 m) as a scale, the sill is about 1.4 m thick. The dike thickness changes from about 0.9 m in the lower part (close to the person) to about 0.6 m at its contact with the sill.

(e) The thickness as seen in the field is normally somewhat less than the original aperture of the magma-filled fractures during emplacement. This follows because, on solidification of the magma, the dike/sill volume reduces or shrinks by about 10%.

Problem

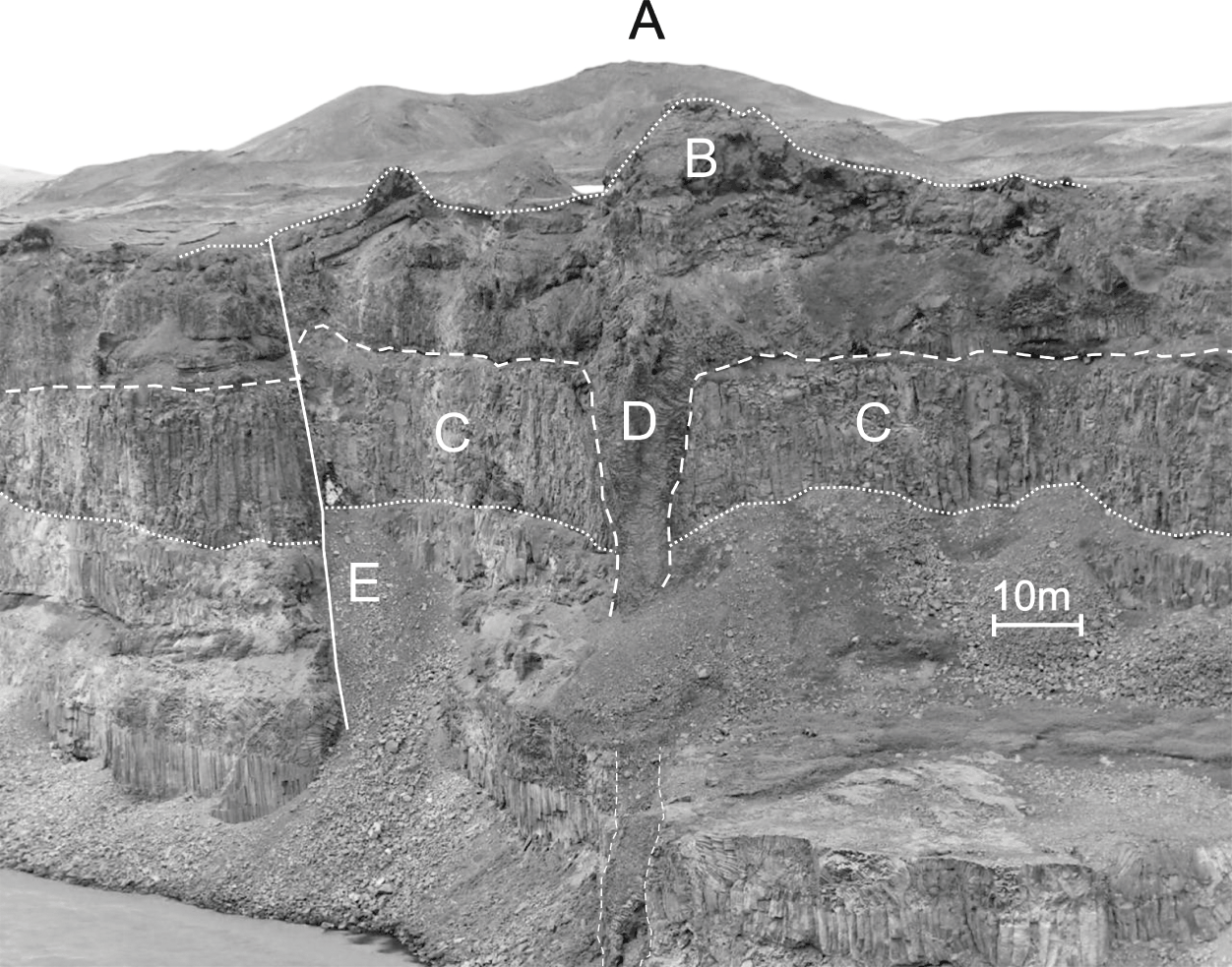

The walls seen in Fig. 1.21 form a part of a large north–south striking river canyon, of Holocene age, in North Iceland. View northeast, the top part of the canyon dissects Holocene layers; the lower part, late Pleistocene layers. Name and describe briefly the structures marked A to E in the photograph.

Fig. 1.21 Various volcanotectonic structures and units (A to E) in a canyon of a glacier river in Northeast Iceland.

Solution

(a) Structure A is a cinder/scoria cone, several tens of metres in diameter, and similar to (though smaller than) the one seen in Fig. 1.1b.

(b) Structure B is a Holocene spatter cone that forms part of the surrounding lava flow. The lava flow is mostly about 20 m thick, but reaches about 30 m where the spatter cone is located. These cones form part of a 75-km-long and 8000-year-old crater row or a volcanic fissure (Gudmundsson et al., Reference Gudmundsson, Friese, Galindo and Philipp2008).

(c) Structure C is a Pleistocene (interglacial) lava flow, 15–20 m thick. It has particularly well-developed sets of columnar joints, mostly vertical.

(d) Structure D is the feeder-dike to the spatter cone (B) and the cinder cone (A). The dike thickness is about 13 m at its contact with the Holocene lava flow (and the spatter cone, B) but 4.5 m in the lowermost parts of the cliff section, close to the river.

(e) Structure E is a reverse fault. Using the Pleistocene lava flow (C) as a marker layer, the fault displacement is about 5 m. The reverse fault is most likely a reactivated normal fault, forming part of a 20-km-long and 0.5–1-km-wide graben. The reactivation is attributed to the horizontal compressive stress generated by the magmatic pressure of the feeder-dike (D) at its time of emplacement (cf. Gudmundsson et al., Reference Gudmundsson, Friese, Galindo and Philipp2008).

1.10 Exercises

1.1 Define an active volcano and a potentially active volcano.

1.2 Define an extinct or fossil volcano.

1.3 Define a monogenetic volcano and a polygenetic volcano.

1.4 Define volcanotectonics as a scientific field.

1.5 What is meant by the attitude of a rock structure?

1.6 In what way is the relationship between aperture and displacement for extension fractures different from that for shear fractures?

1.7 What terms are used in volcanotectonics and structural geology for the terms fault length and fault width in seismology?

1.8 Define the term inflation as used in volcanotectonics and provide a standard interpretation of the processes giving rise to inflation.

1.9 Define the term deflation as used in volcanotectonics and provide a standard interpretation of the processes giving rise to deflation.

1.10 Is the volcanotectonic deformation seen in Figs. 1.7 and 1.9 elastic or permanent? Explain why.

1.11 Explain the acronyms GPS and InSAR and discuss briefly the use of the associated techniques in volcanotectonic studies.

1.12 What is a volcanic tremor?

1.13 What are the main geochemical techniques used to monitor active volcanoes?

1.14 Define the terms earthquake focus (hypocentre) and focal mechanism.

1.15 Define and explain the use of analogue models in volcanotectonics.

1.16 Define and explain the use of probabilistic (statistical) models in volcanotectonics.

1.17 Discuss the main difference between using an analytical model for a magma source (magma chamber) and a numerical model.

1.18 What is a crater row?

1.19 What is a feeder-dike?

1.20 Define volcanic unrest.