An elevated serum lipid level is widely recognised as a primary risk factor for the development of atherosclerosis, CHD and other CVD( Reference Prakash and Jones 1 ). Accumulating evidence suggests that gut dysbiosis induced by a high-fat diet (HFD) promotes the development of hyperlipidaemia, obesity, insulin resistance and the other metabolic syndromes( Reference Eckel, Grundy and Zimmet 2 , Reference Sekirov, Russell and Antunes 3 ). Recent studies have highlighted the importance of the gastrointestinal microbiome in regulating host health and disease( Reference Marchesi, Adams and Fava 4 , Reference Rooks and Garrett 5 ). Therefore, the gut microbiota represents a therapeutic target with the potential to reverse existing hyperlipidaemia, obesity and the related metabolic syndromes.

Probiotics are defined as live micro-organisms that confer health benefits to the host when present in adequate amounts( Reference Homayouni, Ehsani and Azizi 6 ). A variety of beneficial strains, especially Lactobacillus spp., Bifidobacterium spp. and Streptococcus thermophilus, have been shown to alleviate hyperlipidaemia, obesity, insulin resistance and hepatic steatosis in HFD-fed rodents( Reference Marchesi, Adams and Fava 4 ). However, the delivery of viable probiotic bacteria is impeded by the harsh conditions (e.g. gastric acid in the stomach and bile salts in the small intestine) of the upper gastrointestinal tract (GIT); hence, it is desirable to develop methods that enhance the probiotic cell viability until the lower GIT is reached. The microencapsulation of probiotic bacteria is a potential way to physically protect and deliver the cells along the GIT. Although the bacterial cells are embedded in a solid matrix, diffusion of metabolites and substrates into and out of the capsule continues to ensure a high viability( Reference Anselmo, McHugh and Webster 7 ).

The strain Lactobacillus plantarum LIP-1 was originally isolated from a koumiss sample collected in Inner Mongolia. It exhibits cholesterol-lowering activity. However, LIP-1 has a poor tolerance to acidity( Reference Wang, Zhang and Chen 8 ), which lowers its survival rate when transiting through the host GIT after ingestion. Thus, we microencapsulated LIP-1 in milk protein matrices by means of an enzymatic-induced gelation with rennet. Our in vitro studies have already demonstrated that microencapsulation provides adequate protection for LIP-1 against the harsh acidic environments and the detrimental action of bile salts, and the bacteria could be released completely into the intestinal tract( Reference Tian, Song and Wang 9 ). Most published studies merely evaluate the in vitro performance of probiotic microcapsules without considering the fact that huge differences exist between in vivo and in vitro conditions. Thus, it would be necessary to verify the protective effect of microencapsulation on the viability of probiotic bacteria such as the LIP-1 strain along the GIT transit, and the subsequent functional effect in an animal model. Meanwhile, although early studies of our research group have observed the cholesterol-lowering activity of LIP-1 in a hyperlipidaemic rat model, it remains unclear whether any correlations existed between the dynamics of individual gut microbes and the serum lipid levels during probiotic application.

The main objectives of this study were to use high-throughput sequencing technology and real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) to: (1) verify the protective effect of microencapsulation by comparing the gut colonisation of free and microencapsulated LIP-1 cells using an in vivo model, and (2) explore the modulation of gut microbiota in hyperlipidaemia rats as a mechanism of LIP-1-driven blood-lipid-lowering effect.

Methods

Preparation of free and microencapsulated Lactobacillus plantarum LIP-1 cells

LIP-1 was cultured in de Man, Rogosa and Sharpe (MRS) broth (Oxoid Ltd) and incubated for 18 h at 37°C. Cells were collected by centrifugation at 3000 rpm/min for 10 min (Anhui USTC Zonkia Scientific Instruments Co. Ltd). The cell pellet was suspended in 10 % (w/v) skimmed milk and was frozen for 24 h at −80°C before drying under 90 mTorr vacuum in a freeze-dryer (SANYO Electric Co., Ltd) with a cryoprotective agent that was chemically similar to the microcapsule wall. The addition of such an agent ensured that both the free and microencapsulated cells were comparable in terms of composition.

Microencapsulation of LIP-1 was performed using an emulsion method( Reference Tian, Song and Wang 9 ). The microcapsule slurry was frozen for 24 h at −80°C before drying under 90 mTorr vacuum in a freeze-dryer.

For enumeration of bacteria, the freeze-dried LIP-1 free-cell flour was suspended in 0·85 % sodium chloride solution. Meanwhile, freeze-dried microcapsules were suspended in sterile simulated intestinal fluid and incubated at 37°C with constant agitation at 100 rpm for 2 h. 10-fold serial dilutions of the suspension were performed and plated on MRS agar in triplicate; the plates were cultured at 37°C for 48 h. Both the freeze-dried free-cell flour and the microencapsulated LIP-1 cells were stored at −80°C before use.

Animals and experimental design

Forty-two male Wistar rats (4-week-old, weight, 120–150 g), obtained from Vital River Lab Animal Technology Co., Ltd, were housed individually with 12 h light–12 h dark cycle at 22±1°C and were given water ad libitum. Animals were allowed to acclimatise to the environment for 1 week before the experiment. The rats were randomly divided into four groups: normal group (n 10), HFD control group (without probiotics, n 12), HFD with free LIP-1 group (n 10) and HFD with microencapsulated LIP-1 group (n 10). The normal group was fed the normal diet, whereas the other three groups were fed HFD to induce hyperlipidaemia. The HFD included 15 % (w/w) lard oil, 10 % custard powder, 1·2 % cholesterol, 0·3 % sodium taurocholate, 0·3 %propylthiouracil and 73·2 % normal diet( Reference Zhang, Du and Wang 10 ). The probiotics-receiving groups each received a daily dose of 2 ml (109 colony-forming units/ml) of free LIP-1 and microencapsulated LIP-1, respectively, whereas the normal and the HFD control groups were given an equivalent volume of 0·9 % physiological saline instead. Both the bacterial suspension and saline were given intragastrically for 28 d. The food intake of the rats was recorded daily, whereas their body weights were recorded at the start and the end of the study.

The animals were maintained in accordance with the guidelines of the Ethical Committee for Animal Experiments of Inner Mongolia Agricultural University.

Measurement of serum lipids, faecal bile acids and organic acids

At day 28, the rats were given no food for 12 h. Blood samples were collected from the femoral artery and transferred to non-heparinised vacuum collection tubes, and faeces were also collected. The levels of serum lipids, including TAG, total cholesterol (TC), HDL-cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol and the level of faecal total bile acids (TBA), were measured according to the international standard (Sino-UK Institute of Biological Technology).

Each faecal sample (0·1 g) was mixed with 1 ml of ultrapure water before being centrifuged at 10 000 rpm/min for 10 min. An aliquot of 15 μl of 60 % perchloric acid was added to 900 μl of supernatant, and the final volume was adjusted with ultrapure water to l ml. The mixture was allowed to stand for 24 h at 4°C before filtering through a 0·45-μm filter membrane. The filtrate was analysed with the HPLC system equipped with a multi-wavelength fluorescence detector set. An Agilent Zorbax SB C18 column (Agilent Technologies Co., Ltd) was maintained at 42°C, with the degassed mobile phase of 0·1 m orthophosphoric acid and methanol set at a flow rate of 0·5 ml/min.

Sample processing and DNA extraction

Fresh faecal samples were collected from each of the forty-two rats after 28 d of oral application of the probiotics or saline. Samples were immediately placed in liquid N2 and transferred to −80°C until microbial analysis. Genomic DNA was extracted and purified from the faecal samples using the QIAGEN DNA Stool Mini-Kit (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

An aliquot of the lower colon content was collected using a sterile tube, placed in liquid N2 and stored at −80°C until subsequent microbial analysis. Genome DNA was extracted and purified from the colon samples using the TaKaRa MiniBEST Universal Genomic DNA Extraction Kit (catalog no. 9765; TaKaRa Bio) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

The quality of the extracted genomic DNA was checked by agarose gel electrophoresis and spectrophotometric analysis (optical density at 260:280 nm ratio). All extracted DNA samples were stored at −20°C until further experiment.

High-throughput sequencing

Faecal DNA extracted from the samples collected on day 28 was sent to LC Biotech for PCR amplification and sequencing on an MiSeq instrument with 2×300 bp paired-end reads. A fragment of the V3–V4 hyper-variable region of the bacterial 16S rDNA was amplified by using the 391F (5'-ACTCCTACGGGAGGCA GCAG-3') and 806R (5'-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3') primers. The PCR amplicons were purified with beads for pyrosequencing.

The reads were filtered by Quantitative Insights Into Microbial Ecology quality filters. The filtered sequences were then clustered into operational taxonomic units (OTU) at 97 % sequence similarity using CD-HIT( Reference Fu, Niu and Zhu 11 , Reference Li and Godzik 12 ). The most abundant sequence found in each OTU was picked as the representative sequence using the Ribosomal Database Project classifier( Reference Wang, Garrity and Tiedje 13 ). Alpha and beta diversities were calculated on the basis of the de novo taxonomic tree constructed by the representative chimera-checked OTU set using FastTree. The Shannon, Simpson’s diversity, Chao1 and rarefaction estimators were used for evaluating the sequencing depth and biodiversity richness. The weighted and unweighted principal coordinate analyses (PCoA) based on the UniFrac distances derived from the phylogenetic tree were applied to assess the microbiota structure of different samples. For species-level identification and profile refinement, the LC Biotech in-built software was used in combination with self-developed unique annotation tools.

Real-time quantitative PCR

The quantitative determination of the colonisation of LIP-1 in the colon was performed using qPCR. For constructing the standard curves, the genomic DNA of standard strain (LIP-1) was, respectively, extracted using repeated freezing and thawing method, excised from a 1·5 %agarose gel and purified by Wizard SV Gel and PCR Clean-Up System (catalog A9281; Promega). The strain-specific primers (forward primer, 5'-AAGGCTGAAACTCAAAGG-3'; reverse primer, 5'-AACCCAACATCTCACGAC-3') designed by this study were used to quantify the LIP-1 cells.

qPCR was performed using SYBR Premix Ex TaqTM II (catalog no. RR820A; TaKaRa Bio) on the StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System (Thermo Scientific). The reaction mixture (20 μl) contained 10 μl of SYBR Premix Ex Taq II (Tli RNaseH Plus; TaKaRa Bio Co., Ltd) (2×), 0·4 μl of ROX Reference Dye, 2 μl of template DNA and 10 μm of each of the specific primers. The PCR procedures were performed under the following conditions: 95°C for 30 s, followed by forty cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 5 s, annealing temperature at 53°C for 40 s and extension at 72°C for 50 s. A non-template control was included in each assay to confirm that the C t value generated by the lowest DNA concentration was not an artifact. Melt curve analyses were carried out after each PCR to ensure the specificity of DNA amplification.

Statistical analyses

Differences in alpha diversity and relative abundances of bacterial phyla and genera present between samples were assessed using the Wilcoxon test. PCoA and multivariate ANOVA (MANOVA) were used to evaluate differences in the faecal microbiota between sample groups. Associations between serum lipids and faecal microbiota were identified using Spearman’s correlation analysis. The aforementioned statistical analyses were conducted using Matlab® (The MathWorks).

Results

Effects of Lactobacillus plantarum LIP-1 application on the food intake, weight gain and food efficiency ratio of high-fat diet rats

The food intake and food efficiency ratio were not significantly influenced by HFD administration and LIP-1 treatments (P>0·05; Table 1). However, the food efficiency ratio of LIP-1 groups appeared to be generally higher than that of the HFD control group, although not statistically significant (P>0·05; Table 1). No significant difference was observed in the food efficiency ratio between the HFD rats given free or microencapsulated LIP-1 cells (P>0·05; Table 1).

Table 1 Effects of Lactobacillus plantarum LIP-1 application on food intake, weight gain, and food efficiency ratio of high-fat-diet (HFD) rats (Mean values and standard deviations)

a,b Mean values with unlike superscript letters were significantly different in the food intake, weight gain and food efficiency ratio between different groups (P<0·05).

Effect of Lactobacillus plantarum LIP-1 application on the serum lipid levels of high-fat diet rats

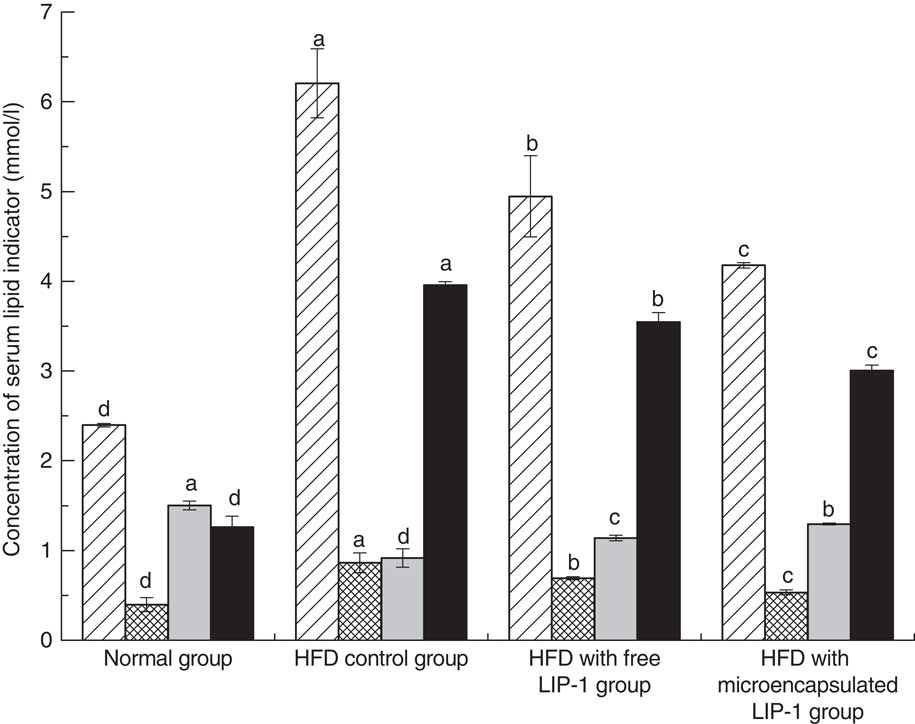

The serum lipid levels, including TAG, TC and LDL-cholesterol, of the HFD control group were significantly higher than that of the normal group (P<0·05; Fig. 1), indicating that the hyperlipidaemic rat model was successfully established.

Fig. 1 Effect of Lactobacillus plantarum LIP-1 application on the serum total cholesterol (TC, ![]() ), TAG (

), TAG (![]() ), HDL-cholesterol (

), HDL-cholesterol (![]() ) and LDL-cholesterol (

) and LDL-cholesterol (![]() ) levels of hyperlipidaemic rats. Values are means and standard deviations represented by vertical bars. Serum samples were taken after 28 d of the corresponding treatment. a,b,c,d Mean values with unlike letters were significantly different in the same serum lipid indicator between different groups (P<0·05).

) levels of hyperlipidaemic rats. Values are means and standard deviations represented by vertical bars. Serum samples were taken after 28 d of the corresponding treatment. a,b,c,d Mean values with unlike letters were significantly different in the same serum lipid indicator between different groups (P<0·05).

Compared with the HFD control group, the rats fed either free or microencapsulated LIP-1 had significantly less serum TC, TAG and LDL-cholesterol, accompanied with an increment in HDL-cholesterol (P<0·05; Fig. 1). Although both probiotic treatments failed to reduce the serum lipid levels of the hyperlipidaemic rats to that of the normal group, the rats fed microencapsulated LIP-1 had significantly lower values of blood TC, TAG and LDL-cholesterol compared with those given free LIP-1 cells (P<0·05; Fig. 1), suggesting that the microencapsulation of LIP-1 cells enhanced the serum lipid reduction effect.

Effect of Lactobacillus plantarum LIP-1 treatment on the faecal total bile acid levels of high-fat diet rats

The TBA levels were significantly reduced in the HFD control group compared with the normal group (P<0·05; Table 2). Compared with the HFD control group, the administration of microencapsulated or free LIP-1 for 28 d significantly elevated the faecal TBA levels (P<0·05; Table 2). Moreover, a stronger effect was observed with the application of the microencapsulated LIP-1 cells compared with the free LIP-1 cells.

Table 2 Effect of Lactobacillus plantarum LIP-1 application on the faecal bile acid concentrations of high-fat-diet (HFD) rats (Mean values and standard deviations)

a,b,c Mean values with unlike superscript letters were significantly different in the same bile acid between different groups (P<0·05).

Effect of Lactobacillus plantarum LIP-1 treatment on the faecal organic acid levels of high-fat diet rats

The levels of lactic acid, acetic acid and propionic acid were significantly reduced in the HFD control group compared with the normal group (P<0·05; Table 3). Compared with the HFD control group, the administration of microencapsulated or free LIP-1 for 28 d significantly elevated the rat faecal organic acid contents (P<0·05; Table 3), which even exceeded the levels of the normal group. Moreover, a stronger effect was observed with the microencapsulated LIP-1 cells compared with the free LIP-1 cells.

Table 3 Effects of Lactobacillus plantarum LIP-1 application on the faecal organic acids concentrations of high-fat-diet (HFD) rats (Mean values and standard deviations)

a,b,c,d Mean values with unlike superscript letters were significantly different in the same organic acid between different groups (P<0·05).

Sequencing coverage and estimation of bacterial diversity

To investigate the effect of LIP-1 administration on the gut microbiota structure, we analysed the faecal bacterial microbiota compositions of the forty-two samples collected at day 28 by sequencing the 16S rRNA V3–V4 region (469 bp) in paired-end mode using the MiSeq system. We generated a data set consisting of 770 409 filtered high-quality and classifiable 16S rDNA gene sequences, and an average of 26 424 sequences was obtained for each sample (range: 11 401–35 973, sd 7334). After PyNAST sequence alignment and 100 % sequence identity clustering, a total of 581 328 representative sequences were identified. All sequences were clustered with representative sequences with a 97 % sequence identity cut-off, leading to 2951 OTU for further analysis.

The Shannon diversity, but not rarefaction, curves for all samples plateaued (online Supplementary Fig. S1). This suggests that the current analysis had already captured most microbial diversity, although more phylotypes might still be found by increasing the sequencing depth.

In terms of the alpha diversity, the microbial richness (Chao1 and Shannon) was not significantly improved by the LIP-1 treatment with or without microencapsulation. Shannon diversity index is as follows: normal group, 5·75 (sd 0·74); HFD model group (no probiotics), 5·89 (sd 0·50); HFD with free LIP-1 group, 5·78 (sd 0·42;) and HFD with microencapsulated LIP-1 group, 6·07 (sd 0·48) (online Supplementary Table S1). Chao1 index is as follows: normal group, 963·06 (sd 171·38); HFD model group (no probiotics), 1071·32 (sd 133·99); HFD with free LIP-1 group, 881·59 (sd 109·62); HFD with microencapsulated LIP-1 group, 832·95 (sd 115·71) (online Supplementary Fig. S2).

Multivariate analyses of the faecal microbiota of different groups

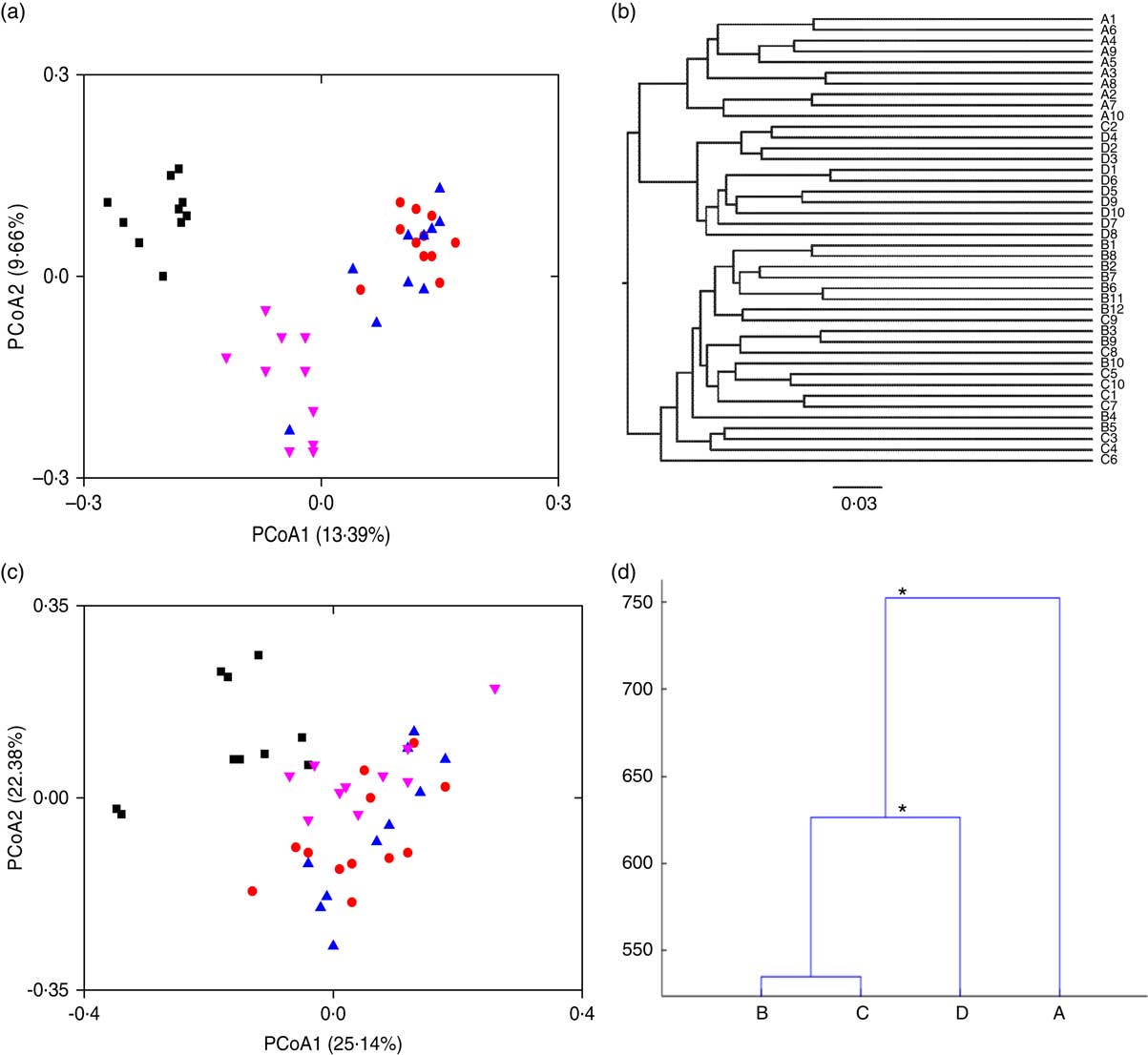

To visualise the differences in faecal microbiota communities of the four rat groups, PCoA, clustering of Unweighted Pair Group Method with Arithmetic Means (UPGMA) and MANOVA were performed. Symbols representing the normal group were clearly separated from those of the HFD groups on the unweighted UniFrac PCoA score plot (Fig. 2(a)). Symbols representing the HFD control and the free LIP-1 groups partly overlapped on the score plot, suggesting that these two groups shared a more similar faecal microbiota structure. Symbols representing the microencapsulated LIP-1 group were again clearly separated from all other groups including rats receiving free LIP-1 cells, suggesting that the microencapsulated LIP-1 cells exerted a stronger modulatory effect on the faecal microbiota. Such patterns were consistent with the results generated by UPGMA (Fig. 2(b)). Moreover, the cluster formed by the microencapsulated LIP-1-fed rats exhibited a lower dissimilarity compared with the other two HFD groups (control without probiotics and rats fed free LIP-1 cells). When we used the weighted UniFrac to perform PCoA, no obvious clustering pattern could be observed (Fig. 2(c)). Yet, significant differences between sample groups could be identified by MANOVA (Fig. 2(d)). Statistically significant separation was observed between the HFD control group and HFD rats fed microencapsulated LIP-1 cells, but not the HFD rats fed free LIP-1 cells (Fig. 2(d)). These results together confirm that the treatment with microencapsulated but not free LIP-1 cells was able to partially recover the disruption of gut microbiota induced by HFD.

Fig. 2 Effect of Lactobacillus plantarum LIP-1 application on the faecal microbiota in hyperlipidaemic rats. Fecal microbiota of the samples were analysed with (a) principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) based on unweighted UniFrac distances, (b) clustering of Unweighted Pair Group Method with Arithmetic Mean, (c) PCoA based on weighted UniFrac distances and (d) multivariate ANOVA, as represented by a dendrogram constructed with the Mahalanobis distance. For PCoA plots, each symbol represents the faecal microbiota of a rat. a and c – group A: normal (![]() ); group B: high-fat diet (HFD) model without probiotics (

); group B: high-fat diet (HFD) model without probiotics (![]() ); group C: HFD with free LIP-1 cells (

); group C: HFD with free LIP-1 cells (![]() ); and group D: HFD with microencapsulated LIP-1 cells (

); and group D: HFD with microencapsulated LIP-1 cells (![]() ). * P<0·05.

). * P<0·05.

Effect of Lactobacillus plantarum LIP-1 treatment on the gut microbiota composition of high-fat diet rats

Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes, Proteobacteria and Verrucomicrobia were the four most dominant bacterial phyla (contributing to 55·8, 32·5, 8·7 and 1·9 % of the total amount of sequences, respectively), whereas the minor phyla were Actinobacteria, Tenericutes, Cyanobacteria and Deferribacteres.

The proportions of the two most abundant phyla, Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes, were not significantly different between any groups (online Supplementary Fig. S4 and Table S2), whereas significantly more Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria and Verrucomicrobia were found in the HFD control group than the normal group (P<0·05; online Supplementary Fig. S4 and Table S1). Compared with the HFD control group, the HFD-induced hyperlipidaemic rats fed free LIP-1 did not show obvious shift in their gut microbiota at the phylum level. However, rats fed with microencapsulated LIP-1 had significantly less Proteobacteria and Verrucomicrobia contrasting to the HFD control group (P<0·05; online Supplementary Fig. S4 and Table S1). Inter-individual variability was also apparent at the phylum level across all groups (online Supplementary Fig. S1).

HFD, 4 weeks, feeding without probiotics led to widespread changes in the gut microbial community structure at the genus level, with increases in the relative abundances of twenty genera, whereas decreases in twenty-five other genera (online Supplementary Fig. S5 and Table S2). Compared with the HFD control group, the administration of free LIP-1 cells caused a significant increase in the relative abundance of only one genus – that is Bacillus. In contrast, feeding rats with microencapsulated LIP-1 had a more pronounced effect on the gut microbiota composition of hyperlipidaemic rats. Specifically, some of the bacterial genera within the phylum Firmicutes increased (including Lactobacillus, Turicibacter and Clostridium), whereas the genus Lachnospira decreased drastically (online Supplementary Fig. S5 and Table S3). Moreover, the relative abundances of Alistipes, Alloprevotella, Clostridium IV, Ruminococcus and Bacteroides significantly increased, whereas other taxa such as Bilophila, Akkermansia muciniphila, Sutterella and Oscillibacter showed an opposite trend (P<0·05; online Supplementary Fig. S5 and Table S3).

The treatment with microencapsulated LIP-1 cells but not free LIP-1 cells resulted in an increase in the relative abundance of the L. plantarum species from 0·0001 (sd 0·0000) to 0·0012 (sd 0·0014) %. Similarly, significantly more Bifidobacterium animalis was found only in the faecal samples of the microencapsulated LIP-1 group (P<0·01) (data not shown).

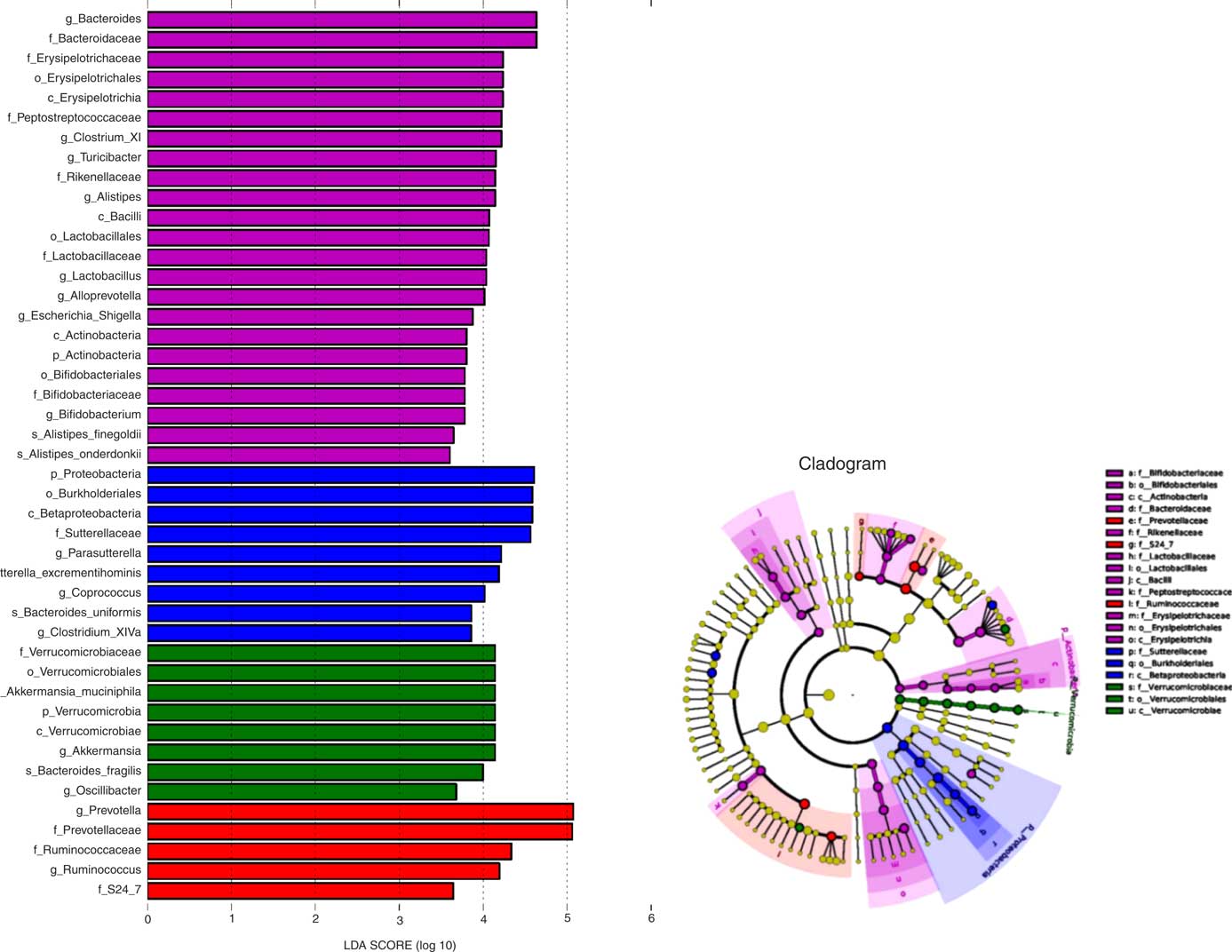

Identification of differentially enriched taxa by linear discriminant analysis effect size

To further explore differences in the microbial community associated between the four sample groups, we analysed the faecal microbiota composition using linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe). The LEfSe analysis revealed a range of enriched taxa at different taxonomic levels (Fig. 3(a)). The cladogram represents the structure of the sample gut microbiota, highlighting the differentially enriched taxa in each group (Fig. 3(b)). Bacteroides, Lactobacillus, ClostridiumXI, Alloprevotella, Bifidobacterium and Turicibacter were enriched in HFD rats fed microencapsulated LIP-1 cells, whereas Parasutterella, Clostridium XlVa and Coprococcus were enriched in HFD rats fed free LIP-1 cells. The genera Akkermansia and Oscillibacter were enriched in the HFD control group. The relative abundance of Escherichia coli increased in the faecal samples of the microencapsulated LIP-1 treatment group.

Fig. 3 Identification of differentially enriched taxa by linear discriminant analysis (LDA) effect size. ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() , Enriched taxa identified in normal, high-fat diet (HFD) control, HFD with free Lactobacillus plantarum LIP-1 and HFD with microencapsulated LIP-1 groups, respectively. The length of the horizontal bar represents the LDA score in log scale; and only taxa with a significant LDA score >3 are plotted. The dots on the cladogram represent the enriched bacterial taxa in the specific group, represented by a specific colour. The size of the dot corresponds to the extent of enrichment.

, Enriched taxa identified in normal, high-fat diet (HFD) control, HFD with free Lactobacillus plantarum LIP-1 and HFD with microencapsulated LIP-1 groups, respectively. The length of the horizontal bar represents the LDA score in log scale; and only taxa with a significant LDA score >3 are plotted. The dots on the cladogram represent the enriched bacterial taxa in the specific group, represented by a specific colour. The size of the dot corresponds to the extent of enrichment.

Associations between intestinal microbiota and serum lipids

Our next goal was to identify correlations between the differentially regulated bacterial taxa mediated by microencapsulated LIP-1 treatment and serum lipids at day 28 (Table 2), as well as correlations among these taxa. Positive correlations were observed between Bilophila and LDL (r 0·397, P<0·05), Escherichia and TC (r 0·057, P=0·737) and Sutterella and TC (r 0·054, P<0·01). Negative correlations were observed between Prevotella and TC (r −0·568, P<0·001), Alloprevotella and TAG (r −0·560, P<0·001), Lactobacillus and TC (r −0·379, P<0·05), Akkermansia and HDL (r −0·411, P<0·05), Bacteroides and LDL (r −0·634, P<0·001) and Alistipes and TAG (r −0·054, P=0·752).

In addition, negative correlations were observed between the genera Akkermansia and Lactbacillus (r −0·532, P<0·001), Bilophila and Lactobacillus (r 0·612, P<0·001) and Sutterella and Lactobacillus (r −0·612, P<0·001). Positive correlations were observed between Turicibacter and Bacteroides (r 0·613, P<0·001) and Akkermansia and Parasutterella (r 0·521, P<0·001).

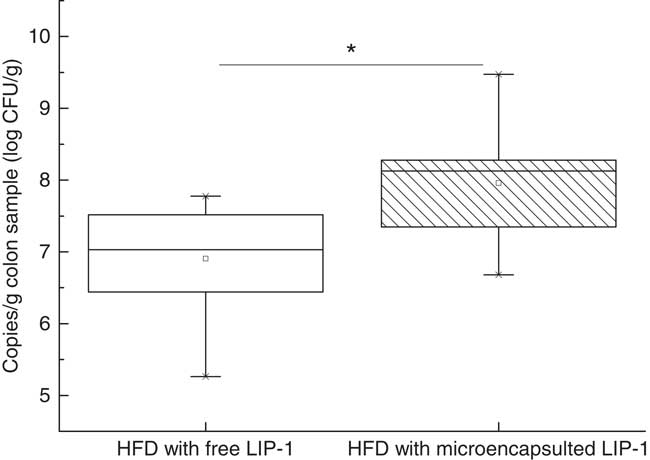

Real-time quantitative PCR

Real-time PCR analysis targeting to the colon content LIP-1 cells revealed a significantly higher level of LIP-1 colonisation in the microencapsulated LIP-1 group compared with that receiving free LIP-1 cells (P<0·05) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4 Quantities of Lactobacillus plantarum LIP-1 in colon samples at day 28, determined by quantitative PCR. Values of the box plot are one-quarter (upper hinges)/three-quarter (lower hinges), median values (middle line), and the maximum and minimum values represented by vertical bars. HFD, high-fat diet. CFU, colony-forming units. * P<0·05.

Discussion

Recent studies have highlighted the significance of a healthy host–gut microbe balance, and gut dysbiosis may play an important role in the development of hyperlipidaemia and related metabolic diseases( Reference Tilg and Kaser 14 , Reference Scott, Antoine and Midtvedt 15 ). Oral delivery of probiotic bacteria has been used as a gut-microbiota-targeted strategy to improve the health conditions relating to gut dysbiosis( Reference Delzenne, Neyrinck and Bäckhed 16 , Reference Chen, Yang and Chen 17 ). However, the effects of administering probiotics on the host gut microbiota composition, as well as the correlations between the changes in probiotics-driven microbiota and serum lipid levels, are poorly characterised. In this study, Spearman’s correlation analysis was also performed to identify correlations between specific gut bacterial taxa and serum lipids. Our results suggest that LIP-1 could modulate the intestinal microbiota of HFD rats, and it is possible that the levels of serum lipids of hyperlipidaemic rats were regulated via such action.

To confer health benefits to the host effectively, probiotics must be able to survive and passage through the stomach and upper intestine. A high viability is also required to ensure that enough bacteria reach the colon to exert the effect and modulate the local microenvironment( Reference Homayouni, Ehsani and Azizi 6 ). Several studies have demonstrated that microencapsulation serves as a physical barrier to protect the bacterial cells and thus enhances the viability of target cells( Reference Tian, Song and Wang 9 , Reference Tomaro-Duchesneau, Saha and Malhotra 18 ). However, published studies mainly assessed the in vitro protective effect of microencapsulation. Therefore, it would be necessary to validate the in vivo effect of microencapsulation.

We compared the quantities of LIP-1 cells in the colon luminal content obtained from rats fed free and microencapsulated LIP-1 cells. The results of real-time PCR showed that the latter group had a higher count (P<0·05; Fig. 4) and thus a higher extent of gut colonisation. At the same time, a more obvious lipid-lowering effect was seen in the hyperlipidaemic rats given microencapsulated LIP-1 than those receiving free LIP-1 cells (P<0·05; Fig. 1), suggesting that the lipid-lowering effect of hyperlipidaemic rats was improved, which might be related to the physical protection of the administered LIP-1 cells. Our results suggest that microencapsulation can be a valid strategy to improve the gut delivery and colonisation of probiotics, which in turn enhances the in vivo probiotic effects, such as cholesterol-lowering in this case. A previous study has also demonstrated that the beneficial effect of probiotics was positively correlated with the number of colonised cells( Reference Ooi and Liong 19 ), which is consistent with our results.

Some previous studies have shown that HFD treatment could alter the composition of gut microbiota and result in intestinal dysbiosis( Reference Tilg and Kaser 14 , Reference Scott, Antoine and Midtvedt 15 ), which was also observed in this work (Fig. 2). Although several studies have reported that the gut microbiota of hyperlipidaemic humans or mice had a significantly greater ratio of members of the phylum Firmicutes:Bacteroidetes (the F:B ratio) compared with their ortholiposis counterparts( Reference Park, Ahn and Park 20 , Reference Wang, Tang and Zhang 21 ), we found no significant difference in the F:B ratio between the normal and the HFD control groups. In contrast, some other studies reported an opposite trend of F:B ratio in hyperlipidaemic individuals( Reference Duncan, Lobley and Holtrop 22 , Reference Schwiertz, Taras and Schäfer 23 ). Such contradictions indicate that the F:B ratio may not reflect the physiological condition of human hyperlipidaemia, and it is yet hard to conclude whether the F:B ratio is directly related to diet intake( Reference Jumpertz, Le and Turnbaugh 24 ). Therefore, these phylum-wide changes in the gut microbiota composition may not be considered as accurate biomarkers for hyperlipidaemia.

It is now known that HFD-induced inflammation and related metabolic disorders are linked to lipopolysaccharide (LPS)( Reference Poggi, Bastelica and Gual 25 , Reference Tsukumo, Carvalho-Filho and Carvalheira 26 ). Lindberg et al.( Reference Lindberg, Weintraub and Zähringer 27 ) reported that the LPS from members of the families Enterobacteriaceae and Desulfovibrionaceae (both belonging to the phylum Proteobacteria) exhibits an endotoxin activity that is 1000-fold that of LPS from the family Bacteroideaceae (phylum Bacteroidetes; members of this phylum are the main LPS producers in the gut).

Previous studies showed that mucosa-damaging bacteria could damage the intestinal mucosa barrier and reduce the expression of genes coding for the tight junction proteins ZO-1 and occludin, which in turn enhance intestinal permeability, leakage of the LPS into the blood and low-grade inflammation related to dyslipidaemia and the other metabolic syndromes( Reference Poggi, Bastelica and Gual 25 , Reference Tsukumo, Carvalho-Filho and Carvalheira 26 ). We found that the HFD control group had higher levels of gut LPS-producing bacteria, especially Bilophila, Sutterella, Oscillibacter and Proteus (member of the phylum Proteobacteria), and mucosa-damaging bacteria (Bilophila and Akkermansiamuciniphila) (P<0·05; online Supplementary Fig. S5). Although Caesar et al.( Reference Caesar, Reigstad and Bäckhed 28 ) reported that the administration of Akkermansia muciniphila reversed HFD-induced metabolic disorders, Ijssennagger et al. ( Reference Ijssennagger, van der Meer and van Mil 29 ) found that Akkermansia muciniphila was induced by HFD and led to abnormal serum lipid metabolism. Similar to the findings of Ijssennagger et al., our results also observed a marked increase in the relative abundances of Bilophila and Akkermansia muciniphila in hyperlipidaemic rats given LIP-1 (both free and encapsulated form) (online Supplementary Fig. S5). Moreover, LPS-producing bacteria of the microencapsulated LIP-1 group were significantly reduced (P<0·05; online Supplementary Fig. S5), accompanied by a more obvious lipid reduction compared with the free LIP-1 group. Caesar et al.( Reference Caesar, Reigstad and Bäckhed 28 ) also demonstrated that probiotic bacteria can significantly reduce the levels of gut-derived LPS and repair the destructive intestinal mucosa, as well as decrease the inflammatory and related metabolic diseases. Results from the Spearman’s correlation analysis showed positive correlations between some of these bacteria and dyslipidaemia (Table 4).

Table 4 Spearman’s correlation coefficient of microencapsulated Lactobacillus plantarum LIP-1 modulated taxa and serum lipid levelsFootnote †

TC, total cholesterol.

* P<0·05, ** P<0·001, # P<0·01.

† Only microencapsulated LIP-1 differentially modulated taxa are included in the table. Rat serum lipid levels were determined after 28 d of treatment of microencapsulated LIP-1.

Probiotics have been shown to regulate intestinal disorders( Reference Delzenne, Neyrinck and Bäckhed 16 , Reference Lahti, Salonen and Kekkonen 30 ). In our study, a 4-week treatment of microencapsulated but not free LIP-1 cells was able to partially recover the HFD-induced dysbiosis, as the overall gut microbiota structure of rats receiving microencapsulated cells resembled more to that of the normal group rats (P<0·05; Fig. 2). At the same time, LIP-1 can beneficially modulate some gut bacteria that are known to associate with serum lipid metabolism (Table 4). These gut microbial changes may play a pivotal role in reducing blood lipids.

Bile acids are steroid acids that are produced in the liver from cholesterol and secreted in bile to facilitate the metabolism of dietary fat( Reference Ridlon, Kang and Hylemon 31 ). Interestingly, the modulation of the bile salt hydrolase (BSH) activity is deemed as an effective strategy in managing metabolic diseases( Reference Jones, Begley and Hill 32 ), as the deconjugation of bile acids in the small intestine may increase the intestinal bile acid excretion. Particularly, free bile acids are excreted more rapidly than the conjugated forms. In our study, the faecal TBA content significantly decreased in the HFD control group compared with that of the normal group, with a significant decrease in the relative abundance of some gut bacteria (Eubacterium, Escherichia and Lactobacillus) (P<0·05; online Supplementary Fig. S5). However, compared with HFD control group, the relative abundance of some gut bacteria (namely Bacteroides, Clostridium, Eubacterium,Escherichia and Lactobacillus) increased in rats given LIP-1 cells (in free or microencapsulated) (online Supplementary Fig. S5), especially for the microencapsulated LIP-1 group (P<0·05; online Supplementary Fig. S5). In addition, a higher faecal TBA content in the microencapsulated LIP-1 treatment group was detected (P<0·05; Table 2). Some gut bacterial commensals (including Bacteroides, Clostridium, Eubacterium, Lactobacillus and Escherichia) are also known to possess BSH activity( Reference Blasco-Baque, Coupé and Fabre 33 ). These bacteria deconjugate bile salts in the gut and enhance bile acid excretion, which help to replenish the bile acids within the enterohepatic circulation( Reference Manzoni, Mostert and Leonessa 34 ). Several studies have also observed that more Escherichia were present within the gut microbiota of hyperlipidaemic mice than their ortholiposis counterparts( Reference Matsui, Ito and Nishimura 35 , Reference Blasco-Baque, Coupé and Fabre 33 ). Armougom et al.( Reference Armougom, Henry and Vialettes 36 ) reported an important role of Escherichia in conferring BSH activity, which is in line with the current findings. Nevertheless, the exact function of Escherichia in regulating hypolipidaemia may need to be further studied. Negative correlations were found between the spectrum of BSH-positive bacteria and dyslipidaemia (Table 4). Several previously published works about lactic acid bacteria have shown that the administration of lactic acid bacteria could modulate the bile acid metabolism in the gut, influence metabolic pathways involved in energy and lipid metabolism, leading to alterations in lipid peroxidation by modifying the gut microbiota composition( Reference Hu and Yue 37 – Reference Wang, Zhang and Guo 39 ).

Some studies have shown the involvement of SCFA produced by gut bacterial fermentation in blood lipid regulation. For example, propionate inhibits localised epithelial cells from absorbing intestinal lipids, stimulate intestinal mucosa epithelial cell proliferation and repair damaged colonic mucosa( Reference Marcil, Delvin and Garofalo 40 , Reference Nishina and Freedland 41 ), whereas butyrate reduces the level of liver cholesterol, as well as liver pyruvate dehydrogenase activity, and thus decreases fatty acid synthesis( Reference Trautwein, Rieckhoff and Erbersdobler 42 , Reference Stappenbeck, Hooper and Gordon 43 ). We found that the faecal SCFA (mainly acetate, propionate and butyrate) content significantly decreased in the HFD control compared with the normal group (Table 3), with significant decreases in the relative abundances of some strains belonging to the genera Prevotella, Lactobacillus, Alloprevotella and Eubacterium (P<0·05; online Supplementary Fig. S5). In contrast, the relative abundances of some other strains from the same or different genera (Lactobacillus,Alloprevotella, Eubacterium, Coprococcus and Ruminococcus) increased in rats given LIP-1 cells (in free or microencapsulated) compared with rats of the HFD control group, especially for the microencapsulated LIP-1 group (P<0·05; online Supplementary Fig. S5). The microencapsulated LIP-1 group had 10-fold more Lactobacillus compared with the LIP-1 free-cell group (online Supplementary Table S4). Moreover, a higher faecal SCFA content was detected in the microencapsulated LIP-1 treatment group (Table 3), which could be a result of an increase in the gut SCFA-producing strains. Common butyric acid and propionate acid producers include Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and certain genera of Eubacterium, Prevotella, Alloprevotella, Coprococcus, Lactobacillus and Ruminococcus ( Reference Sekirov, Russell and Antunes 3 , Reference Marchesi, Adams and Fava 4 , Reference Moore and Moore 44 , Reference Zhong, Marungruang and Fåk 45 ). Zhong et al.( Reference Zhong, Marungruang and Fåk 45 ) found strong correlations between butyric acid and the abundance of the butyrate-producing strains. Thus, it is likely that the administration of LIP-1 promotes the growth of SCFA-producing strains that beneficially help repair any intestinal mucosal damages, inhibit the synthesis and assimilation of lipid and hence lower the serum lipids in hyperlipidaemic rats. Furthermore, negative correlations were found between these strains and dyslipidaemia (Table 4). Lactobacillus paracasei CNCM I-4270 application could modulate the host microbiota, particularly increase the proportion of SCFA-producing strains in gut and hence lower the serum lipids in hyperlipidaemic rats( Reference Wang, Tang and Zhang 21 ). Similar mechanisms in lipid reduction have been reported by Park et al.( Reference Park, Ahn and Park 20 ).

By LIP-1 treatment (particularly the microencapsulated group), we additionally found an increase in some taxa that are generally considered beneficial to the host (especially Alistipes, Turicibacter and members of Erysipelotrichaceae) and a reduction in some harmful bacteria (Enterobacter and Bilophila) (P<0·05; Fig. 3 and online Supplementary Fig. S5). Obese humans who succeeded in weight loss had an enriched abundance of Alistipes ( Reference Everard, Lazarevic and Gaïa 46 , Reference Louis, Tappu and Damms-Machado 47 ). Some studies showed that Turicibacter decreased markedly in mice given HFD, whereas several studies further observed the reduction of Turicibacter in animal models of inflammatory bowel disease; thus, this genus may be anti-inflammatory( Reference Rossi, Pengo and Caldin 48 , Reference Jones-Hall, Kozik and Nakatsu 49 ). Some specific taxa within the family Erysipelotrichaceae are highly immunogenic and may provide promising microbial targets to combat metabolic disorders( Reference Labbé, Ganopolsky and Martoni 50 , Reference Palm, De Zoete and Cullen 51 ). Our data revealed that these potentially beneficial taxa (Alistipes, Turicibacter and members of Erysipelotrichaceae) negatively correlated with the blood lipid levels in hyperlipidaemic rats (Table 4). Additionally, negative correlations were also observed between these potentially beneficial taxa with Akkermansia and Bilophila that have previously been reported to be harmful( Reference Ijssennagger, van der Meer and van Mil 29 ). A previous study has indicated that probiotics may colonise along the gut epithelial cells and compete with harmful bacteria for adsorption sites on the mucosal cells; thus, they may encourage the growth of other beneficial bacteria( Reference Jones and Versalovic 52 ).

In summary, we have shown that gut dysbiosis occurred in HFD-induced hyperlipidaemic rats, and that the supplementation of LIP-1 could lower the serum lipids of these HFD rats, accompanied by beneficial modulation of the gut bacterial microbiota. The microencapsulation enhances the colonisation of LIP-1 in the gut, which also resulted in a more pronounced hypolipidaemic effect. Some taxa that are associated with the host serum lipid levels (namely TC, TAG, LDL-cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol) were also modulated after LIP-1 treatment. Our work not only confirms that microencapsulation protects the probiotic cells in vivo and enhances their colonisation in the host gut, but also demonstrates the feasibility of gut-microbiota-targeted probiotic intervention in the management of hyperlipidaemia.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported financially by the Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos 31160315,31660456, 31460389), the Natural Science Foundation of Inner Mongolia (grant no. 2015MS0306), the ‘Western Light’ Talent Cultivation Program of CAS and the China Agriculture Research System (grant no. CARS-36).

The authors thank L.-Y. K., W. Y. L., Y. N. S., B. M. and G. W. for their contribution to the study.

The authors’ contributions were as follows: J. G. W. and B. M. conceived and designed the experiments; J. J. S., W. J. T., Y. L. W. and Y. N. S. performed the experiments; J. J. S., W. J. T. and L.-Y. K. analysed the data and drafted the manuscript.

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material/s referred to in this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114517002380