1. Introduction

The aerodynamic performance of high-speed vehicles is dominated by boundary layer (BL) physics. Turbulent BLs cause elevated heat transfer and skin friction drag, which are detrimental to the survivability of high-speed aircraft. Thus, from an engineering perspective, extending the laminar flow over the aircraft is beneficial, as it leads to reduced aerodynamic heating and drag, and helps control the weight of the thermal protection systems (Glass Reference Glass2008). The present work aims to understand the mechanisms governing second-mode dominated turbulent transition in hypersonic flows, which is expected to support the engineering of efficient flow control strategies (Chou, Marineau & Smith Reference Chou, Marineau and Smith2023).

1.1. Transition to turbulence in high-speed flows

Transition to turbulence in external flows is typically caused by the BL receiving various types of external disturbances from the free-stream or internal disturbances from surface irregularities on the aircraft body (Reshotko Reference Reshotko1994). This receptivity mechanism is affected by several factors, including the mean flow, vehicle geometry and the amplitude and frequency content of free-stream disturbances. For high-speed flows, the amplification of dominant instabilities can occur through several mechanisms, as depicted by Morkovin, Reshotko & Herbert (Reference Morkovin, Reshotko and Herbert1994), which can be broadly classified into three paths. For low-amplitude disturbances, the BL encourages the growth of specific unstable eigenmodes. For moderate-level disturbances, transient growth may occur, where otherwise stable BL eigenmodes couple due to mutual non-orthogonality and exhibit short-duration algebraic growth

![]() $({\sim} \textit{te}^{-t})$

(Reshotko Reference Reshotko2001). Both of these pathways eventually lead to nonlinear mechanisms, i.e. intermodal interactions and sub- or super-harmonic resonances, once a critical amplitude level is surpassed. Finally, for higher-amplitude disturbances, bypass mechanisms dominate the transition process as the modal growth pathway is entirely skipped (Morkovin Reference Morkovin1985).

$({\sim} \textit{te}^{-t})$

(Reshotko Reference Reshotko2001). Both of these pathways eventually lead to nonlinear mechanisms, i.e. intermodal interactions and sub- or super-harmonic resonances, once a critical amplitude level is surpassed. Finally, for higher-amplitude disturbances, bypass mechanisms dominate the transition process as the modal growth pathway is entirely skipped (Morkovin Reference Morkovin1985).

The current work focuses on the first path – the amplification of unstable BL eigenmodes. In free-flight conditions, hypersonic vehicles encounter a low-disturbance free-stream, making the modal growth pathway practically relevant (Schneider Reference Schneider2004) especially on slender geometries at low angles of attack. The modal amplification is the precursor to several types of other multi-mode interactions, which eventually cause transition to turbulence. Such nonlinear interactions can involve K-type resonances (Bake, Meyer & Rist Reference Bake, Meyer and Rist2002), where two oblique waves at equal and opposite angles interact with the dominant mode, or H-type resonances (Herbert Reference Herbert1988), where sub-harmonic oblique modes interact with the primary mode.

1.2. Kinematics and mechanics of hypersonic boundary layer transition

Boundary layer instabilities can be broadly categorised into the following: streamwise-convective or longitudinal, cross-flow, centrifugal (Görtler) or of the attachment-line type (Saric, Reshotko & Arnal Reference Saric, Reshotko and Arnal1998). Streamwise-travelling instabilities are the most prominent in BLs over sharp, slender geometries and at low angles of attack. For higher Mach numbers (Ma

![]() $\gt$

5), instability mechanisms are dominated by compressibility effects rather than viscous effects. Consequently, acoustic-like, dilatational instabilities play a more prominent role in high-speed transition under such canonical conditions.

$\gt$

5), instability mechanisms are dominated by compressibility effects rather than viscous effects. Consequently, acoustic-like, dilatational instabilities play a more prominent role in high-speed transition under such canonical conditions.

Lees & Lin (Reference Lees and Lin1946) extended the application of Rayleigh’s incompressible inflection point criterion

![]() $(\partial ^2 u_0/\partial y^2=0)$

to the compressible regime, with

$(\partial ^2 u_0/\partial y^2=0)$

to the compressible regime, with

![]() $u_0$

denoting the base flow streamwise velocity. They proposed the presence of a generalised inflection point

$u_0$

denoting the base flow streamwise velocity. They proposed the presence of a generalised inflection point

![]() $ (\partial /\partial y (\rho _0 \partial u_0/\partial y )=0 )$

as a sufficient condition for the onset of first-mode instabilities, which are dominant in supersonic flows. Here,

$ (\partial /\partial y (\rho _0 \partial u_0/\partial y )=0 )$

as a sufficient condition for the onset of first-mode instabilities, which are dominant in supersonic flows. Here,

![]() $\rho_0$

denotes the base flow density. These were observed to be most unstable when oblique, in contrast to the planar Tollmien-Schlichting waves. Lees (Reference Lees1957) then predicted the first modes to be destabilised by wall heating, whereas cooling was predicted to remove the inflection point from the BL and hence, eradicate the first-mode instabilities. Later, Mack (Reference Mack1969) used compressible linear stability theory (LST) to prove the existence of a new family of instability modes, in addition to the first modes. Stability theory suggested that the existence of these modes only requires a region of supersonic flow relative to the disturbance propagation speed, and does not require the presence of a generalised inflection point. These were identified as acoustic-type instabilities trapped within the BL, which are destabilised by wall cooling instead. The fundamental harmonic of this family, the second-mode wave, is most destabilised when planar (or two-dimensional) and is the most dominant instability in the hypersonic transition process under canonical conditions. Our analysis here shows that the generalised inflection point, denoted as

$\rho_0$

denotes the base flow density. These were observed to be most unstable when oblique, in contrast to the planar Tollmien-Schlichting waves. Lees (Reference Lees1957) then predicted the first modes to be destabilised by wall heating, whereas cooling was predicted to remove the inflection point from the BL and hence, eradicate the first-mode instabilities. Later, Mack (Reference Mack1969) used compressible linear stability theory (LST) to prove the existence of a new family of instability modes, in addition to the first modes. Stability theory suggested that the existence of these modes only requires a region of supersonic flow relative to the disturbance propagation speed, and does not require the presence of a generalised inflection point. These were identified as acoustic-type instabilities trapped within the BL, which are destabilised by wall cooling instead. The fundamental harmonic of this family, the second-mode wave, is most destabilised when planar (or two-dimensional) and is the most dominant instability in the hypersonic transition process under canonical conditions. Our analysis here shows that the generalised inflection point, denoted as

![]() $y=y_i$

throughout this manuscript, plays an important role in facilitating the trapping of acoustic waves in the BL and initiating second-mode resonance.

$y=y_i$

throughout this manuscript, plays an important role in facilitating the trapping of acoustic waves in the BL and initiating second-mode resonance.

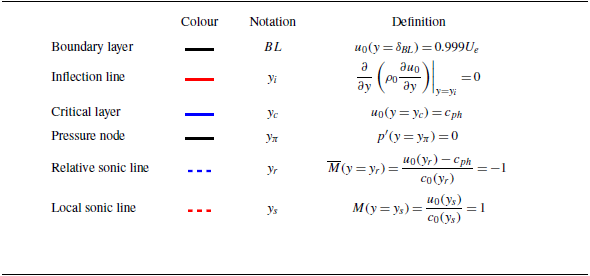

1.2.1. Kinematics of second modes and geometrical acoustics applications

In hypersonic BLs, a region exists where the instability waves propagate supersonically relative to the local mean flow, delineated by the relative sonic line

![]() $(y=y_r)$

. The prevailing notion in the literature is that disturbances can establish standing wave-like patterns within this region

$(y=y_r)$

. The prevailing notion in the literature is that disturbances can establish standing wave-like patterns within this region

![]() $(y\lt y_r)$

, which acts as an acoustic waveguide trapping a discrete family of modes (Mack Reference Mack1984). To the authors’ knowledge, the first schematic of this process was presented by Morkovin (Reference Morkovin1987, figure 3), which was later redrawn by Saric et al. (Reference Saric, Reshotko and Arnal1998, figure 4). They showed the streamwise-convecting second modes to be trapped underneath

$(y\lt y_r)$

, which acts as an acoustic waveguide trapping a discrete family of modes (Mack Reference Mack1984). To the authors’ knowledge, the first schematic of this process was presented by Morkovin (Reference Morkovin1987, figure 3), which was later redrawn by Saric et al. (Reference Saric, Reshotko and Arnal1998, figure 4). They showed the streamwise-convecting second modes to be trapped underneath

![]() $y=y_r$

, which was later highlighted in the schematic shown by Fedorov & Tumin (Reference Fedorov and Tumin2011, figure 2). More recently, Knisely & Zhong (Reference Knisely and Zhong2019, figure 1) provided a detailed schematic of the second-mode instabilities demonstrating them to have a double-deck structure with acoustic waves trapped below the relative sonic line and subsonic rope-like structures at the critical layer above. In the current work, we use the ray-tracing approach to show that acoustic waves get trapped underneath the generalised inflection point

$y=y_r$

, which was later highlighted in the schematic shown by Fedorov & Tumin (Reference Fedorov and Tumin2011, figure 2). More recently, Knisely & Zhong (Reference Knisely and Zhong2019, figure 1) provided a detailed schematic of the second-mode instabilities demonstrating them to have a double-deck structure with acoustic waves trapped below the relative sonic line and subsonic rope-like structures at the critical layer above. In the current work, we use the ray-tracing approach to show that acoustic waves get trapped underneath the generalised inflection point

![]() $(y=y_i)$

, rather than the relative sonic line

$(y=y_i)$

, rather than the relative sonic line

![]() $(y=y_r)$

.

$(y=y_r)$

.

One of the first works considering geometrical acoustics for wall shear flows was by Kriegsmann & Reiss (Reference Kriegsmann and Reiss1983), where trapped waves were shown to form caustics inside the BL and a method for analysing such caustic fields was presented. Later, Parziale et al. (Reference Parziale, Shepherd and Hornung2015) analysed the second-mode waves using the ray-tracing approach and showed that cooled walls lead to higher wave trapping in the BL. Kuehl (Reference Kuehl2018) suggested the second-mode trapping to be caused by a fluid layer of higher density, and thus higher specific impedance, residing near the BL edge. Inspired by these findings, we use the ray-tracing approach to analyse the kinematics of acoustic wave trapping and its dependency on the wall temperature. We observe the important role played by the generalised inflection line and discuss the competing effects of density and wall-normal velocity gradient in facilitating the trapping.

1.2.2. Mechanics of second-mode instabilities

Kuehl (Reference Kuehl2018) provided an alternative interpretation of the second modes as thermoacoustically driven instabilities, attributing the resonance formation to the presence of an impedance well between the bottom hard wall and the higher-impedance region near the BL edge. Using an inviscid disturbance energy equation, resonance was shown to be sustained through the term

![]() $-\partial /\partial y ( \rho _0 T'v' + \rho 'T_0v' )$

, denoted a thermoacoustic Reynolds stress production term in the study. In the manuscript, we denote all laminar base flow quantities as

$-\partial /\partial y ( \rho _0 T'v' + \rho 'T_0v' )$

, denoted a thermoacoustic Reynolds stress production term in the study. In the manuscript, we denote all laminar base flow quantities as

![]() $(\cdot)_0$

and fluctuations as

$(\cdot)_0$

and fluctuations as

![]() $(\cdot)'$

, with

$(\cdot)'$

, with

![]() $p,T,\rho,u,v$

denoting the pressure, temperature, density, streamwise and wall-normal velocities. In our previous study (Roy & Scalo Reference Roy and Scalo2025), we derived a second-order disturbance energy equation without neglecting viscous and thermal diffusion, demonstrating closure of the second-mode energy budgets. The total disturbance energy production is due to the term

$p,T,\rho,u,v$

denoting the pressure, temperature, density, streamwise and wall-normal velocities. In our previous study (Roy & Scalo Reference Roy and Scalo2025), we derived a second-order disturbance energy equation without neglecting viscous and thermal diffusion, demonstrating closure of the second-mode energy budgets. The total disturbance energy production is due to the term

![]() $-v's'\partial s_0/\partial y$

with

$-v's'\partial s_0/\partial y$

with

![]() $s^\prime =f(T^\prime ,p^\prime ,T_0,p_0)$

denoting the entropy fluctuations. It peaks at the inflection layer

$s^\prime =f(T^\prime ,p^\prime ,T_0,p_0)$

denoting the entropy fluctuations. It peaks at the inflection layer

![]() $(y=y_i)$

, which lies below the critical layer

$(y=y_i)$

, which lies below the critical layer

![]() $(y_i\lt y_c)$

for cool walls

$(y_i\lt y_c)$

for cool walls

![]() $(\Theta=T_w/T_{ad}\lt1)$

, and coincides

$(\Theta=T_w/T_{ad}\lt1)$

, and coincides

![]() $(y_i\simeq y_c)$

at near-adiabatic conditions. We also showed that thermoacoustic effects, as defined by the coordinated action of pressure and heat flux fluctuations (Rayleigh Reference Rayleigh1894), act as a sink (and not production) for the disturbance energy.

$(y_i\simeq y_c)$

at near-adiabatic conditions. We also showed that thermoacoustic effects, as defined by the coordinated action of pressure and heat flux fluctuations (Rayleigh Reference Rayleigh1894), act as a sink (and not production) for the disturbance energy.

This prompted us to analyse the relative phasing between fluctuating variables in this work, attempting to understand how disturbance energy is produced or dissipated. A similar study was performed by Tian & Wen (Reference Tian and Wen2021), in which the relative phasing between individual terms in the linearised governing equations was examined for a Mach 6 adiabatic flat plate. However, the dependency on the wall-cooling ratio was not analysed. A term involving the wall-normal velocity fluctuations,

![]() $-v'/T_0 \partial T_0/\partial y$

, and a fluctuating conduction term,

$-v'/T_0 \partial T_0/\partial y$

, and a fluctuating conduction term,

![]() $\partial ^2 T'/\partial y^2$

, were observed to drive the temporal rate of change of internal energy at the critical layer. Additionally, the near-wall pressure dilatation was found to be driven by the thermal conduction from the wall. They concluded that the second-mode resonance is analogous to the thermoacoustic mechanisms in a Rijke tube. However, the phase analysis conducted in the current study demonstrates that temperature fluctuations initially induce thermal dilatations away from the wall, which then drive near-wall mechanical dilatation through wall-normal flux transport. Thermoacoustic effects, if any, cause absorption of disturbance energy, rather than production.

$\partial ^2 T'/\partial y^2$

, were observed to drive the temporal rate of change of internal energy at the critical layer. Additionally, the near-wall pressure dilatation was found to be driven by the thermal conduction from the wall. They concluded that the second-mode resonance is analogous to the thermoacoustic mechanisms in a Rijke tube. However, the phase analysis conducted in the current study demonstrates that temperature fluctuations initially induce thermal dilatations away from the wall, which then drive near-wall mechanical dilatation through wall-normal flux transport. Thermoacoustic effects, if any, cause absorption of disturbance energy, rather than production.

1.3. Wall-temperature effects on second-mode growth

The effects of wall cooling on supersonic/hypersonic transition have been considered in numerous investigations (Mack Reference Mack1975; Watson Reference Watson1977; Lysenko & Maslov Reference Lysenko and Maslov1984; Blanchard Reference Blanchard1995; Fedorov et al. Reference Fedorov, Soudakov, Egorov, Sidorenko, Gromyko, Bountin, Polivanov and Maslov2015; Oddo et al. Reference Oddo, Hill, Reeder, Chin, Embrador, Komives, Tufts, Borg and Jewell2021), and it is well known that cooled walls destabilise the second modes. To the best of our knowledge, most studies have focused on combining experimental observations with stability analysis, while first-principles-based mechanistic explanations of varying wall temperatures remain limited.

A detailed investigation of the second-mode structure is performed by Unnikrishnan & Gaitonde (Reference Unnikrishnan and Gaitonde2019) using the momentum potential theory by Doak (Reference Doak1989), which decomposes a flow field into the fluid-thermodynamic modes (acoustic, vortical, and thermal modes). The transition in a Mach 6 flat plate was considered, and the effect of surface cooling was studied. The acoustic and thermal components were demonstrated to stay trapped between the wall and the critical layer, while the vorticity, being the dominant component, stayed concentrated near the generalised inflection line. Later, the study was extended to consider a broader range of wall temperatures, as variations in the structure of the second modes were examined (Unnikrishnan & Gaitonde Reference Unnikrishnan and Gaitonde2021), accounting for three-dimensional mechanisms and free-stream radiation by supersonic modes.

The stronger growth rate observed in cooled walls is commonly attributed to the reduction of thermal and hydrodynamic BL heights. In this work, our goal is to provide a description of the mechanics underlying this relationship. Specifically, by employing the disturbance energy framework (Roy & Scalo Reference Roy and Scalo2025), we assess the influence of the wall temperature on the different components of the total disturbance energy, showing where they are generated, and how they are redistributed within the BL via wall-normal fluxes.

1.4. Manuscript outline

The effect of wall temperature on the second-mode structure is the primary focus of this work. Boundary layer-resolved direct numerical simulations (DNS) and LST analysis are performed, offering the supporting dataset for the theoretical investigations.

The manuscript is structured as follows. In § 2, the flow conditions and the DNS set-up are described, and the spectral LST solver is formulated. In § 3, an overview is given of the fundamental questions we consider in this study, and the theoretical tools used to address the questions. Section 4 demonstrates acoustic wave trapping in the BL from two frames of reference, one stationary and another in the frame of the convecting instabilities. Section 5 analyses the eigenstructure of the instabilities via a phase analysis, serving as a precursor to the following sections, where the disturbance energy flux transport and production mechanisms sustaining the second-mode resonance are studied, and the influence of wall temperature is discussed. The findings are summarised in § 6.

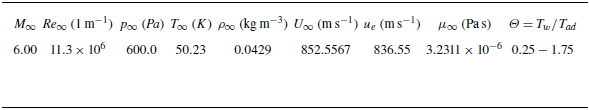

Table 1. Free-stream and wall-temperature conditions considered in this study.

2. Flow conditions and computational set-up

2.1. Base flow definition

The current work considers a transitional hypersonic BL over a slender, sharp-tipped, circular cone of half-angle

![]() $3^\circ$

, spanning

$3^\circ$

, spanning

![]() $L_x=1.2$

m in the streamwise direction (see figure 1). The cone is exposed to a Mach

$L_x=1.2$

m in the streamwise direction (see figure 1). The cone is exposed to a Mach

![]() $6$

flow at

$6$

flow at

![]() $0^\circ$

angle of attack with a free-stream unit Reynolds number

$0^\circ$

angle of attack with a free-stream unit Reynolds number

![]() $( \textit{Re}_{\infty}=\rho_{\infty} U_{\infty} / \mu_{\infty} )$

of

$( \textit{Re}_{\infty}=\rho_{\infty} U_{\infty} / \mu_{\infty} )$

of

![]() $11.3\times 10^6\,\textrm{m}^{-1}$

. The free-stream conditions, given in table 1, are inspired by the experimental set-up (Miller et al. Reference Miller, Jantze, Redmond, Scalo and Jewell2023) at Purdue’s Mach 6 Quiet Tunnel facility, BAM6QT.

$11.3\times 10^6\,\textrm{m}^{-1}$

. The free-stream conditions, given in table 1, are inspired by the experimental set-up (Miller et al. Reference Miller, Jantze, Redmond, Scalo and Jewell2023) at Purdue’s Mach 6 Quiet Tunnel facility, BAM6QT.

Figure 1. Schematic of the flow problem comprising a

![]() $\psi _c=3^\circ$

half-angle axisymmetric cone subjected to a hypersonic free-stream flow (see table 1). The table above shows the free-stream Mach number

$\psi _c=3^\circ$

half-angle axisymmetric cone subjected to a hypersonic free-stream flow (see table 1). The table above shows the free-stream Mach number

![]() $(M_\infty)$

, unit Reynolds number

$(M_\infty)$

, unit Reynolds number

![]() $(Re_\infty)$

, pressure

$(Re_\infty)$

, pressure

![]() $(p_\infty)$

, temperature

$(p_\infty)$

, temperature

![]() $(T_\infty)$

, density

$(T_\infty)$

, density

![]() $(\rho_\infty)$

, velocity

$(\rho_\infty)$

, velocity

![]() $(U_\infty)$

and dynamic viscosity

$(U_\infty)$

and dynamic viscosity

![]() $(\mu_\infty)$

.

$(\mu_\infty)$

.

![]() $(u_e)$

represents the BL edge velocity.

$(u_e)$

represents the BL edge velocity.

![]() $\Theta$

is the ratio between the wall temperature

$\Theta$

is the ratio between the wall temperature

![]() $(T_w)$

and the adiabatic wall temperature

$(T_w)$

and the adiabatic wall temperature

![]() $(T_{ad})$

. In this work,

$(T_{ad})$

. In this work,

![]() $T_w$

is varied uniformly above and below

$T_w$

is varied uniformly above and below

![]() $T_{ad}$

.

$T_{ad}$

.

The cone wall temperature is isothermal and set by varying the ratio between the wall temperature and the adiabatic (recovery) temperature,

![]() $\varTheta =T_w/T_{\textit{ad}}$

. The different ratios considered in this work are shown in figure 2. The recovery temperature for a laminar flow can be estimated as

$\varTheta =T_w/T_{\textit{ad}}$

. The different ratios considered in this work are shown in figure 2. The recovery temperature for a laminar flow can be estimated as

![]() $T_{\textit{ad}} = T_e ( 1 + \sqrt {\textit{Pr}} \, (\gamma-1)/2 M_e^2 )$

, with ‘e’ denoting the BL edge quantities (White Reference White2006). In the current work, we assume a Taylor–Maccoll flow over the cone to obtain the BL edge quantities used to calculate the recovery temperature. The resulting wall temperatures are shown in figure 2. Additionally, an adiabatic wall is also considered for comparison with the isothermal

$T_{\textit{ad}} = T_e ( 1 + \sqrt {\textit{Pr}} \, (\gamma-1)/2 M_e^2 )$

, with ‘e’ denoting the BL edge quantities (White Reference White2006). In the current work, we assume a Taylor–Maccoll flow over the cone to obtain the BL edge quantities used to calculate the recovery temperature. The resulting wall temperatures are shown in figure 2. Additionally, an adiabatic wall is also considered for comparison with the isothermal

![]() $(\varTheta =1.0)$

case; the former imposes the Neumann conditions on the temperature perturbations

$(\varTheta =1.0)$

case; the former imposes the Neumann conditions on the temperature perturbations

![]() $(\partial T'/\partial y=0)$

, while the latter imposes a homogeneous Dirichlet condition

$(\partial T'/\partial y=0)$

, while the latter imposes a homogeneous Dirichlet condition

![]() $(T'=0)$

.

$(T'=0)$

.

Figure 2. Base flow profiles at different wall-temperature ratios. The top row shows the temperature and density profiles, while the bottom row shows the velocity profiles along with the speed of sound. The dashed line represents the adiabatic wall results, and the solid lines represent isothermal walls at temperatures

![]() $T_w=\varTheta \, T_{\textit{ad}}$

. The values of

$T_w=\varTheta \, T_{\textit{ad}}$

. The values of

![]() $\varTheta$

are given in the table above. The profiles are plotted at

$\varTheta$

are given in the table above. The profiles are plotted at

![]() $x=0.9$

m (see figure 1).

$x=0.9$

m (see figure 1).

Figure 2 shows the temperature, streamwise velocity, density and sonic speed profiles of the laminar BL, along with the first and second derivatives of the temperature and velocity. The temperature gradient at the wall is positive, zero and negative for the cooled, adiabatic and heated wall cases, respectively. The magnitude of the velocity and temperature gradients at the wall is higher for colder walls than for hotter walls, resulting in significant thermal loading at the wall, as depicted by the highly negative value of

![]() $\partial ^2 T_0/\partial y^2$

at the wall. For sufficiently cold walls, the density profiles reveal a lighter fluid region trapped between two denser fluid regions at the wall and at the BL edge. These features of the mean flow profiles play a crucial role in controlling the second-mode growth, as examined in this work.

$\partial ^2 T_0/\partial y^2$

at the wall. For sufficiently cold walls, the density profiles reveal a lighter fluid region trapped between two denser fluid regions at the wall and at the BL edge. These features of the mean flow profiles play a crucial role in controlling the second-mode growth, as examined in this work.

2.2. Governing equations

The hypersonic BL is simulated by numerically solving the fully compressible Navier–Stokes equations, which in index notation, read

where

![]() $(x_1,x_2,x_3) = (X,Y,Z)$

denotes the Cartesian system. The system

$(x_1,x_2,x_3) = (X,Y,Z)$

denotes the Cartesian system. The system

![]() $(x,y)$

denotes the two-dimensional, BL-attached coordinate system (see figure 3). The effect of gravity is ignored, and other source terms are not present in the problem considered. The total energy (per unit mass),

$(x,y)$

denotes the two-dimensional, BL-attached coordinate system (see figure 3). The effect of gravity is ignored, and other source terms are not present in the problem considered. The total energy (per unit mass),

![]() $E$

, is the sum of specific internal energy,

$E$

, is the sum of specific internal energy,

![]() $e$

, and specific kinetic energy,

$e$

, and specific kinetic energy,

![]() $E=e + V^2/2$

, where

$E=e + V^2/2$

, where

![]() $V=u_{\kern-1pt j}u_{\kern-1pt j}$

. The viscous stress tensor

$V=u_{\kern-1pt j}u_{\kern-1pt j}$

. The viscous stress tensor

![]() $\tau _{\textit{ji}}$

is given as

$\tau _{\textit{ji}}$

is given as

![]() $\mu ( \partial u_{\kern-1pt j}/\partial x_i + \partial u_i/\partial x_{\kern-1pt j} ) + \lambda (\partial u_k/\partial x_k) \delta _{\textit{ij}}$

, where

$\mu ( \partial u_{\kern-1pt j}/\partial x_i + \partial u_i/\partial x_{\kern-1pt j} ) + \lambda (\partial u_k/\partial x_k) \delta _{\textit{ij}}$

, where

![]() $\delta _{\textit{ij}}$

is the Kronecker delta and

$\delta _{\textit{ij}}$

is the Kronecker delta and

![]() $\lambda =-2/3\mu$

is used assuming that bulk viscosity

$\lambda =-2/3\mu$

is used assuming that bulk viscosity

![]() $\mu _b=0$

(Stokes’ hypothesis). The above equations are written in terms of the total fluid variables, which can be decomposed into a laminar mean state and a perturbation about the mean, as

$\mu _b=0$

(Stokes’ hypothesis). The above equations are written in terms of the total fluid variables, which can be decomposed into a laminar mean state and a perturbation about the mean, as

![]() $(.)=(.)_0+(.)'$

. Hereafter, we use these notations to denote the mean and the perturbation components.

$(.)=(.)_0+(.)'$

. Hereafter, we use these notations to denote the mean and the perturbation components.

The stagnation temperature of the chosen flow remains much below the ionisation point of air. Thus, air has been modelled as an ideal, calorically perfect gas following

![]() $p=\rho \textit{RT}$

, with a specific gas constant,

$p=\rho \textit{RT}$

, with a specific gas constant,

![]() $R=287$

J kg

$R=287$

J kg

![]() $^{-1}$

K

$^{-1}$

K

![]() $^{-1}$

, specific heat ratio,

$^{-1}$

, specific heat ratio,

![]() $\gamma =1.4$

, specific heat capacity,

$\gamma =1.4$

, specific heat capacity,

![]() $C_p=\gamma R / (\gamma - 1)$

, and Prandtl number,

$C_p=\gamma R / (\gamma - 1)$

, and Prandtl number,

![]() $ \textit{Pr}=0.707$

. Viscosity is modelled as a function of temperature, using the low-temperature correction on Sutherland’s law, as given by Mack (Reference Mack1965).

$ \textit{Pr}=0.707$

. Viscosity is modelled as a function of temperature, using the low-temperature correction on Sutherland’s law, as given by Mack (Reference Mack1965).

2.3. Set-up for axisymmetric direct numerical simulations

The numerical simulations are performed using CFDSU, a Fortran-based finite difference solver originally developed by Nagarajan, Lele & Ferziger (Reference Nagarajan, Lele and Ferziger2003) that has been consistently developed and maintained at Purdue University. The solver has been used for various types of flow applications previously, including Large Eddy Simulation modelling (Chen & Scalo Reference Chen and Scalo2021), vortex dynamics (Chapelier, Wasistho & Scalo Reference Chapelier, Wasistho and Scalo2018; Zhao & Scalo Reference Zhao and Scalo2021), hypersonic transitional (Sousa et al. Reference Sousa, Wartemann, Wagner and Scalo2024) and turbulent flows (Toki et al. Reference Toki, Sousa, Chen and Scalo2024). CFDSU solves the Navier–Stokes equations in a structured curvilinear grid using the staggered arrangement. Several time integration and spatial discretisation schemes are available in CFDSU. For the present purposes, a low-storage, fourth-order accurate, 6-stage Runge–Kutta scheme (Allampalli et al. Reference Allampalli, Hixon, Nallasamy and Sawyer2009) and the compact sixth-order scheme by Visbal & Gaitonde (Reference Visbal and Gaitonde2002) are used for time integration and spatial discretisation, respectively. This numerical strategy is expected to achieve spectral-like numerical accuracy with low numerical dissipation, which is required for simulating a transitional hypersonic BL.

Figure 3. Summary of the computational set-up for high-order DNS calculations: (a) a low-order precursor run resolving the shock

![]() $(\psi _s=9.808^\circ )$

is used to drive (b) embedded high-order DNS on a near-wall, BL-focused domain. A grid-independent pseudorandom noise is imposed at the wall to trigger turbulent transition in the embedded DNS calculations.

$(\psi _s=9.808^\circ )$

is used to drive (b) embedded high-order DNS on a near-wall, BL-focused domain. A grid-independent pseudorandom noise is imposed at the wall to trigger turbulent transition in the embedded DNS calculations.

It is known that the second modes, which are the dominant instabilities for hypersonic transition, are predominantly two-dimensional in nature. Over axisymmetric bodies, they evolve into azimuthal streaks due to mean flow distortion (Chynoweth et al. Reference Chynoweth, Schneider, Hader, Fasel, Batista, Kuehl, Juliano and Wheaton2019) before the eventual three-dimensional turbulent breakdown. The present investigation focuses on the initial modal amplification stage of the transition process, which is the primary destabilisation pathway for BL flow under low free-stream disturbance levels. For these purposes, axisymmetric DNS is deemed sufficient. The DNS set-up used here comprises the following three steps, taking special care in removing spurious numerical artefacts:

-

(i) Low-order precursor – the DNS solver requires an initial laminar base flow to start the simulations. For this, we combine the Taylor–Maccoll (TM) inviscid flow approximation for the region between the shock and the BL edge, and the compressible Blasius similarity approximation for the near-wall, BL viscous flow. This is imposed on the left boundary of the computational domain (see figure 3 a). A low-order calculation, using a second-order finite differencing scheme with a centralised stencil, then propagates the TM + Blasius solution downstream. This allows the pressure adjustments that occur due to precision mismatch between the TM + Blasius Ordinary Differential Equation (ODE) solver and the low-order DNS to wash off, leading to a more accurate laminar base flow. The precursor simulations are performed on a larger computational domain, resolving the shock. The shock was captured using the Localised-artificial diffusivity method by Kawai & Lele (Reference Kawai and Lele2008), relying on the addition of artificial bulk and dynamic viscosity, and conductivity to the governing equations. Care is taken not to add artificial diffusion near the wall to avoid contaminating the BL solution.

-

(ii) High-order stationary base flow – the statistically stationary laminar flow from the low-order precursor run is then used to initialise BL-focused high-order DNS calculations (see figure 3 b) that use a quasi-spectral sixth-order scheme in a compact stencil (Visbal & Gaitonde (Reference Visbal and Gaitonde2002)). Additionally, we use a sixth-order Pade filter with filter coefficient

$\alpha =0.49$

to remove spurious high-frequency wavenumbers. As the numerical transients wash off downstream, the thus-obtained stationary flow represents the quiet laminar hypersonic flow solution over the cone, which is used as the base flow for our LST analysis.

$\alpha =0.49$

to remove spurious high-frequency wavenumbers. As the numerical transients wash off downstream, the thus-obtained stationary flow represents the quiet laminar hypersonic flow solution over the cone, which is used as the base flow for our LST analysis. -

(iii) Artificial noise – a controlled perturbation is required to initiate transitional waves in an otherwise numerically quiet laminar flow. Its spectral signature is modulated so that the artificial forcing is independent of the computational grid used. This is achieved by filtering a discretely sampled field in the Legendre spectral space to remove features above a chosen cutoff wavenumber. The analytical form of the noise, resulting from the spectral projection, ensures that the discrete sampling at the grid points remains consistent across different levels of grid refinement. The imposed velocity fluctuations at the wall are given as

(2.2)where \begin{align} v'_w (x, y=0, t) = A_0 \sum _{m=0}^{m_f-1} a(f_m) \textrm{Re} \left ( \bar {\phi }_m(x) e^{-2\pi i f_m t} \right )\!, \end{align}

\begin{align} v'_w (x, y=0, t) = A_0 \sum _{m=0}^{m_f-1} a(f_m) \textrm{Re} \left ( \bar {\phi }_m(x) e^{-2\pi i f_m t} \right )\!, \end{align}

$A_0$

is a dimensional coefficient controlling the overall signal amplitude,

$A_0$

is a dimensional coefficient controlling the overall signal amplitude,

$a(f_m)\in [-1,1]$

is a frequency-dependent normalised amplitude modulation and

$a(f_m)\in [-1,1]$

is a frequency-dependent normalised amplitude modulation and

$\bar {\phi }_m(x)\in [-1,1]$

is the spatially filtered one-dimensional field. A total of

$\bar {\phi }_m(x)\in [-1,1]$

is the spatially filtered one-dimensional field. A total of

$m_f$

such fields, one for each discrete frequency,

$m_f$

such fields, one for each discrete frequency,

$f_m$

, are imposed simultaneously. The forcing has been applied over the time span

$f_m$

, are imposed simultaneously. The forcing has been applied over the time span

$t \in [0,n_{c}/f_0 ]$

in the simulations, where

$t \in [0,n_{c}/f_0 ]$

in the simulations, where

$f_0$

is the lowest frequency considered and

$f_0$

is the lowest frequency considered and

$n_{c}$

represents a certain number of periodic cycles. The forcing is introduced in the region

$n_{c}$

represents a certain number of periodic cycles. The forcing is introduced in the region

$x\in [0.255,0.301]$

m for all cases considered in this work. Discrete frequencies in the range of

$x\in [0.255,0.301]$

m for all cases considered in this work. Discrete frequencies in the range of

$f_m\in [60{-}200]$

kHz at intervals of

$f_m\in [60{-}200]$

kHz at intervals of

$10$

kHz are used. In all the DNS runs, the forcing is applied over

$10$

kHz are used. In all the DNS runs, the forcing is applied over

$n_c=5$

cycles of the lowest frequency,

$n_c=5$

cycles of the lowest frequency,

$60$

kHz, starting from

$60$

kHz, starting from

$t=0$

, with the amplitude

$t=0$

, with the amplitude

$A_0= (10^{-3},\,10^{-2} )$

(m s−1), which corresponds to

$A_0= (10^{-3},\,10^{-2} )$

(m s−1), which corresponds to

$p^\prime _w/p_\infty =5.5\times (10^{-6},\,10^{-5} )$

. For the temporal spectra modulation function,

$p^\prime _w/p_\infty =5.5\times (10^{-6},\,10^{-5} )$

. For the temporal spectra modulation function,

$a(f_m)$

, an inverse-frequency dependence (pink noise) is used, mimicking the free-stream noise present in supersonic/hypersonic wind tunnels (Duan et al. Reference Duan2019). Further details regarding the implementation of the forcing function and the rationale behind the choice for

$a(f_m)$

, an inverse-frequency dependence (pink noise) is used, mimicking the free-stream noise present in supersonic/hypersonic wind tunnels (Duan et al. Reference Duan2019). Further details regarding the implementation of the forcing function and the rationale behind the choice for

$n_c$

are discussed in Roy & Scalo (Reference Roy and Scalo2025).

$n_c$

are discussed in Roy & Scalo (Reference Roy and Scalo2025).

2.4. Laguerre–Galerkin spectral linear stability theory

A companion linear stability analysis is performed to support the DNS results and complement the phase relationship analysis between the flow variables. Linear stability theory involves representing the fluctuating flow variables as normal modes, which, upon plugging into the linearised governing equations, form an eigenvalue problem. For the LST analysis, the fluctuating modes are assumed to be locally parallel, meaning that the mode shapes are functions of the wall-normal coordinate only. LST, however, does not account for the inter-modal interactions and non-parallel effects, i.e. the effect of the BL growth. The non-parallel effects are more prominent near the leading edge, where the BL height increases rapidly. This study concentrates on the linear amplification stage away from the leading edge, where the non-parallel effects are not significant. In fact, excellent agreement is shown between DNS and the present LST formulation by Roy & Scalo (Reference Roy and Scalo2025) for the current free-stream flow conditions at a wall temperature of 300 K

![]() $(\varTheta \approx 0.85)$

.

$(\varTheta \approx 0.85)$

.

Considering the two-dimensional, BL-attached coordinate system

![]() $(x,y)$

(see figure 3), the ansatz used is

$(x,y)$

(see figure 3), the ansatz used is

![]() $\psi '=\hat {\psi }(y)e^{i(\alpha x-\omega t)}$

, where

$\psi '=\hat {\psi }(y)e^{i(\alpha x-\omega t)}$

, where

![]() $\psi '=(p',T',u',v')$

represents the fluctuating variables. The density perturbation terms in the governing equations can be recast in terms of

$\psi '=(p',T',u',v')$

represents the fluctuating variables. The density perturbation terms in the governing equations can be recast in terms of

![]() $p'$

and

$p'$

and

![]() $T'$

using the equation of state. When the governing (2.1) are decomposed into mean and fluctuating states and the above ansatz is substituted in, the resulting system of equations takes the following form:

$T'$

using the equation of state. When the governing (2.1) are decomposed into mean and fluctuating states and the above ansatz is substituted in, the resulting system of equations takes the following form:

where

![]() $L, M$

and

$L, M$

and

![]() $N$

are matrices dependent on the base flow

$N$

are matrices dependent on the base flow

![]() $\psi _0(x,y)$

, the wavenumber

$\psi _0(x,y)$

, the wavenumber

![]() $(\alpha )$

and the angular frequency

$(\alpha )$

and the angular frequency

![]() $(\omega )$

. We note that here we are considering a local one-dimensional linear stability problem, where (2.3) represents a separate stability problem to be solved for each

$(\omega )$

. We note that here we are considering a local one-dimensional linear stability problem, where (2.3) represents a separate stability problem to be solved for each

![]() $x$

location.

$x$

location.

The wall-normal derivatives can be discretised by any finite differencing schemes, as outlined by Malik (Reference Malik1990). When discretised on

![]() $n$

points in

$n$

points in

![]() $y$

, the

$y$

, the

![]() $L,M,N$

matrices have the shape

$L,M,N$

matrices have the shape

![]() $4n\times 4n$

, representing the four conservation equations for mass, x- and y-momenta and energy. Here, a spectral Galerkin approach is used for the spatial discretisation (Shen, Tang & Wang Reference Shen, Tang and Wang2011), in which the mode shapes are expanded using a suitable spectral basis as

$4n\times 4n$

, representing the four conservation equations for mass, x- and y-momenta and energy. Here, a spectral Galerkin approach is used for the spatial discretisation (Shen, Tang & Wang Reference Shen, Tang and Wang2011), in which the mode shapes are expanded using a suitable spectral basis as

![]() $\hat {\psi }(y)=\sum _{k=0}^n \tilde {\psi }_k\phi _k(y)$

. Here,

$\hat {\psi }(y)=\sum _{k=0}^n \tilde {\psi }_k\phi _k(y)$

. Here,

![]() $\phi _k$

represents mutually orthogonal, globally smooth basis functions and

$\phi _k$

represents mutually orthogonal, globally smooth basis functions and

![]() $\tilde {\psi }_k$

the associated weights. The global nature of spectral methods imparts a much superior accuracy than local discretisation schemes. The Galerkin approach to solve for the unknown weights

$\tilde {\psi }_k$

the associated weights. The global nature of spectral methods imparts a much superior accuracy than local discretisation schemes. The Galerkin approach to solve for the unknown weights

![]() $\tilde {\psi }_k$

involves taking an inner product of (2.3) on the spectral space spanned by the basis functions outlined in the following section. The mutual orthogonality of the functions allows the inner product operation to form separate equations for the unknown weights, which can be solved for. The resulting equation from this operation, representing the projection of (2.3) on the spectral space, reads

$\tilde {\psi }_k$

involves taking an inner product of (2.3) on the spectral space spanned by the basis functions outlined in the following section. The mutual orthogonality of the functions allows the inner product operation to form separate equations for the unknown weights, which can be solved for. The resulting equation from this operation, representing the projection of (2.3) on the spectral space, reads

\begin{align} \sum _{k=0}^{n-1} \left [ \big ( L D^2\phi _k, \phi _j \big )_w + \left ( \textit{MD}\phi _k, \phi _j \right )_w + \big ( N \phi _k, \phi _j \big )_w \right ]\tilde {\psi }_k = 0, \quad \forall \,0 \leqslant j \leqslant n, \end{align}

\begin{align} \sum _{k=0}^{n-1} \left [ \big ( L D^2\phi _k, \phi _j \big )_w + \left ( \textit{MD}\phi _k, \phi _j \right )_w + \big ( N \phi _k, \phi _j \big )_w \right ]\tilde {\psi }_k = 0, \quad \forall \,0 \leqslant j \leqslant n, \end{align}

where

![]() $D$

denotes the derivative operator

$D$

denotes the derivative operator

![]() $d/dy$

, and

$d/dy$

, and

![]() $(.,.)_w$

denotes the weighted inner product of two functions. At this point, two types of eigenvalue problems can be formulated – spatial or temporal – depending on whether

$(.,.)_w$

denotes the weighted inner product of two functions. At this point, two types of eigenvalue problems can be formulated – spatial or temporal – depending on whether

![]() $\omega$

or

$\omega$

or

![]() $\alpha$

is considered real, respectively. For the second-mode waves, which are convective instabilities, the spatial and temporal theory results are interrelated (Gaster & Grant Reference Gaster and Grant1975), and solving one or the other imparts the relevant BL stability characteristics. In the present study, the spatial stability eigenvalue problem is solved, which involves finding the complex eigenvalue

$\alpha$

is considered real, respectively. For the second-mode waves, which are convective instabilities, the spatial and temporal theory results are interrelated (Gaster & Grant Reference Gaster and Grant1975), and solving one or the other imparts the relevant BL stability characteristics. In the present study, the spatial stability eigenvalue problem is solved, which involves finding the complex eigenvalue

![]() $\alpha =\alpha _r+i\alpha _i$

for each real frequency

$\alpha =\alpha _r+i\alpha _i$

for each real frequency

![]() $\omega$

. As per the ansatz convention used,

$\omega$

. As per the ansatz convention used,

![]() $-\alpha _i$

represents the amplification rate of the modes.

$-\alpha _i$

represents the amplification rate of the modes.

It is to be noted that the spatial problem involves solving an equation of the form

![]() $\sum _{k=0}^{n-1} (\alpha ^2 M + \alpha C + K)\tilde {\psi }_k=0$

, which results in a quadratic eigenvalue problem for

$\sum _{k=0}^{n-1} (\alpha ^2 M + \alpha C + K)\tilde {\psi }_k=0$

, which results in a quadratic eigenvalue problem for

![]() $\alpha$

. One way to solve this problem is by extending the definition of

$\alpha$

. One way to solve this problem is by extending the definition of

![]() $\tilde {\psi }_k$

to

$\tilde {\psi }_k$

to

![]() $ ( \tilde {\psi }_k, \alpha \tilde {\psi }_k )^T$

so that a generalised eigenvalue problem is recovered of the form,

$ ( \tilde {\psi }_k, \alpha \tilde {\psi }_k )^T$

so that a generalised eigenvalue problem is recovered of the form,

![]() $\alpha B\boldsymbol{v}=A\boldsymbol{v}$

. Upon solving, the eigenvalues

$\alpha B\boldsymbol{v}=A\boldsymbol{v}$

. Upon solving, the eigenvalues

![]() $\alpha$

will provide the exponential growth rates

$\alpha$

will provide the exponential growth rates

![]() $(-\alpha _i)$

and wavenumbers

$(-\alpha _i)$

and wavenumbers

![]() $(\alpha _r)$

. The eigenvectors

$(\alpha _r)$

. The eigenvectors

![]() $\boldsymbol{v}=(\tilde {p}, \tilde {T}, \tilde {u}, \tilde {v})$

, representing the weights of the spectral expansion, ultimately define the wall-normal mode shapes

$\boldsymbol{v}=(\tilde {p}, \tilde {T}, \tilde {u}, \tilde {v})$

, representing the weights of the spectral expansion, ultimately define the wall-normal mode shapes

![]() $\hat {\psi }(y)$

.

$\hat {\psi }(y)$

.

2.4.1. Choice of spectral basis

The present work focuses on the stability of a semi-infinite flow problem, for which the generalised Laguerre functions are a suitable expansion basis (Shen et al. Reference Shen, Tang and Wang2011). Perturbations in the flow quantities due to the presence of the instability modes are expected to decay away from the BL, and by definition, the Laguerre functions decay exponentially in the positive real axis

![]() $[0,\infty )$

, rendering them a natural choice for semi-infinite flows. The nodes and weights are computed using the Laguerre–Gauss–Radau quadrature, and the base flow variables are interpolated at the quadrature nodes using a piecewise cubic spline interpolation. The unbounded domain is suitably scaled by a factor to increase the number of nodes in the BL (see Shen et al. Reference Shen, Tang and Wang2011, pp. 278–281), improving the numerical accuracy.

$[0,\infty )$

, rendering them a natural choice for semi-infinite flows. The nodes and weights are computed using the Laguerre–Gauss–Radau quadrature, and the base flow variables are interpolated at the quadrature nodes using a piecewise cubic spline interpolation. The unbounded domain is suitably scaled by a factor to increase the number of nodes in the BL (see Shen et al. Reference Shen, Tang and Wang2011, pp. 278–281), improving the numerical accuracy.

The spectral basis used for expanding the fluctuation variables is modified so that the homogeneous Dirichlet boundary conditions (BCs) are implicitly satisfied at the wall. The BCs there are no slip

![]() $(u^\prime =0)$

, no penetration

$(u^\prime =0)$

, no penetration

![]() $(v^\prime =0)$

and isothermal

$(v^\prime =0)$

and isothermal

![]() $(T^\prime =0)$

. The algebraic modification required for this is given as

$(T^\prime =0)$

. The algebraic modification required for this is given as

where

![]() $\mathcal{L}_k(y)$

denotes the

$\mathcal{L}_k(y)$

denotes the

![]() $k$

th generalised Laguerre function. For adiabatic walls, a Neumann BC is to be imposed at the wall on temperature fluctuations,

$k$

th generalised Laguerre function. For adiabatic walls, a Neumann BC is to be imposed at the wall on temperature fluctuations,

![]() $(\partial T'/\partial y)_w=0$

. This requires a different algebraic modification to the expansion basis (Shen Reference Shen2000, p. 1126), given as

$(\partial T'/\partial y)_w=0$

. This requires a different algebraic modification to the expansion basis (Shen Reference Shen2000, p. 1126), given as

For the other fluctuation variables, (2.5) is used. For

![]() $p^\prime$

, the Laguerre basis

$p^\prime$

, the Laguerre basis

![]() $(\mathcal{L}_k)$

can be used without modifications, as it is not required to satisfy any BC.

$(\mathcal{L}_k)$

can be used without modifications, as it is not required to satisfy any BC.

3. Theoretical framework and research objectives

This manuscript investigates the fundamental mechanisms governing hypersonic transition in the canonical set-up shown in figure 4(a). The most unstable eigenmodes in this case are the second modes, first predicted by Mack (Reference Mack1969). The second-mode waves are not sustained by viscous mechanisms and behave as inviscid-type waves trapped underneath the BL, forming the characteristic rope-wave structures observed in several experiments (Demetriades Reference Demetriades1974; Stetson & Kimmel Reference Stetson and Kimmel1993). The second-mode mechanics are heavily dependent on the wall temperature, as they are destabilised more over colder walls. This work aims to understand the fundamental mechanisms underlying this wall-temperature dependence.

This study aims to answer the following specific questions:

-

(i) Where are second-mode waves trapped in the BL, and how are they formed?

-

(ii) What fluid dynamic mechanisms cause the production of disturbance energy and its redistribution within the BL?

-

(iii) How does wall temperature influence the production and distribution of energy?

Figure 4. Schematic supporting the formulation of the theoretical questions being tackled in this work: (a) observational window for evaluation of the wavepacket energy during its convective evolution; (b) double-deck structure of second-mode waves with rope-like structures carrying disturbance energy near the critical layer and trapped acoustic modes accumulating energy near the wall; (c) quiver plot of the fluctuating velocity vector field overlaid onto fluctuating pressure field and fluctuating temperature field, indicative of the production mechanisms sustaining second-mode resonance.

We use acoustic ray tracing to examine the trapping of waves in the BL by studying the motion of individual acoustic rays making up a wavefront. A novel disturbance energy equation (Roy & Scalo Reference Roy and Scalo2025) is used to gain insights into the energy production mechanisms fuelling instability growth. We use the flow-field data from DNS (figure 4 c) and LST (figure 4 b) to analyse the phase relationships between fluctuating flow variables and characterise what causes production and dissipation of disturbance energy.

3.1. Disturbance energy equation

To investigate the mechanisms of second-mode growth, we use a second-order closure for the perturbation energy budget, derived in an earlier work (Roy & Scalo Reference Roy and Scalo2025). The equation, inspired by the works of Myers (Reference Myers1991), describes the evolution of perturbation energy in the following conservation form:

where the second-order disturbance energy term,

![]() $E_2$

, representing the energy content of a disturbance wave packet, is given as

$E_2$

, representing the energy content of a disturbance wave packet, is given as

\begin{align} E_2 = \underbrace {\frac {1}{2} \frac {\rho _0 T_0}{C_p}s'^2}_{i} + \underbrace {\rho ' u_{0i}u_i'}_{\textit{ii}} + \underbrace {\frac {1}{2} \rho _0 u_i'^2}_{\textit{iii}}+ \underbrace {\frac {1}{2}\frac {p'^2}{\gamma p_0}}_{\textit{iv}}. \end{align}

\begin{align} E_2 = \underbrace {\frac {1}{2} \frac {\rho _0 T_0}{C_p}s'^2}_{i} + \underbrace {\rho ' u_{0i}u_i'}_{\textit{ii}} + \underbrace {\frac {1}{2} \rho _0 u_i'^2}_{\textit{iii}}+ \underbrace {\frac {1}{2}\frac {p'^2}{\gamma p_0}}_{\textit{iv}}. \end{align}

The above expression represents the disturbance’s contribution to the total instantaneous energy of a fluid element. In (3.2), term

![]() $(i)$

denotes the thermal potential energy stored in the temperature/entropy hot spots, while terms

$(i)$

denotes the thermal potential energy stored in the temperature/entropy hot spots, while terms

![]() $(\textit{ii})$

and

$(\textit{ii})$

and

![]() $(\textit{iii})$

collectively represent the kinetic energy of the perturbation. Since term

$(\textit{iii})$

collectively represent the kinetic energy of the perturbation. Since term

![]() $(\textit{ii})$

arises due to the non-zero base flow, it will be referred to as the mean flow energy term throughout this work to differentiate it from term

$(\textit{ii})$

arises due to the non-zero base flow, it will be referred to as the mean flow energy term throughout this work to differentiate it from term

![]() $(\textit{iii})$

, which will be denoted simply as the disturbance kinetic energy. Finally, term

$(\textit{iii})$

, which will be denoted simply as the disturbance kinetic energy. Finally, term

![]() $(\textit{iv})$

quantifies the acoustic or mechanical potential energy resulting from compression and rarefaction work.

$(\textit{iv})$

quantifies the acoustic or mechanical potential energy resulting from compression and rarefaction work.

The energy flux term,

![]() $I_{2j}$

, quantifies the flux of each of the above-mentioned disturbance energy components and is given as

$I_{2j}$

, quantifies the flux of each of the above-mentioned disturbance energy components and is given as

\begin{align} I_{2j} = \underbrace {\frac {1}{2} \frac {\rho _0 T_0}{C_p}s'^2 u_{0j}}_{i} + \underbrace {\rho _0 u_{0i}u_i' \left ( u_{\kern-1pt j}' + \frac {\rho ' u_{0j}}{\rho _0} \right )}_{ii} + \underbrace {\frac {1}{2} \rho _0 u_i'^2 u_{0j}}_{iii} + \underbrace {p' \left ( u_{\kern-1pt j}' + \frac {\rho ' u_{0j}}{\rho _0} \right )}_{iv}. \end{align}

\begin{align} I_{2j} = \underbrace {\frac {1}{2} \frac {\rho _0 T_0}{C_p}s'^2 u_{0j}}_{i} + \underbrace {\rho _0 u_{0i}u_i' \left ( u_{\kern-1pt j}' + \frac {\rho ' u_{0j}}{\rho _0} \right )}_{ii} + \underbrace {\frac {1}{2} \rho _0 u_i'^2 u_{0j}}_{iii} + \underbrace {p' \left ( u_{\kern-1pt j}' + \frac {\rho ' u_{0j}}{\rho _0} \right )}_{iv}. \end{align}

It is important to note that the acoustic flux

![]() $(\textit{iv})$

is an extension of the commonly known acoustic flux,

$(\textit{iv})$

is an extension of the commonly known acoustic flux,

![]() $p'u_{j}'$

, to a non-zero mean flow.

$p'u_{j}'$

, to a non-zero mean flow.

Finally, the right-hand side source/sink term,

![]() $D_2$

, reads

$D_2$

, reads

\begin{align} \begin{aligned} D_2 =& - \underbrace {\frac {p' u_{0j}}{C_p} \frac {\partial s'}{\partial x_{\kern-1pt j}}}_{I} - \underbrace {\rho ' u_{0i}\left ( u_{\kern-1pt j}' + \frac {\rho ' u_{0j}}{\rho _0} \right )\frac {\partial u_{0i}}{\partial x_{\kern-1pt j}}}_{\textit{II}} + \underbrace {\frac {T'}{T_0}\frac {\partial }{\partial x_{\kern-1pt j}} \left ( \frac {\mu _0 C_p}{\textit{Pr}} \frac {\partial T'}{\partial x_{\kern-1pt j}} + \frac {\mu ' C_p}{\textit{Pr}} \frac {\partial T_0}{\partial x_{\kern-1pt j}} \right )}_{\textit{III}}\\ &- \underbrace {\frac {T'}{T_0} \left ( \rho _0 T_0 u_{\kern-1pt j}' + \rho ' T_0 u_{0j} + \rho _0 T' u_{0j} \right )\frac {\partial s_0}{\partial x_{\kern-1pt j}}}_{\textit{IV}} + \underbrace {\rho _0 u_{0i}u_{\kern-1pt j}' \frac {\partial u_i'}{\partial x_{\kern-1pt j}}}_{V} + \underbrace {\left ( u_i'+\frac {\rho ' u_{0i}}{\rho _0} \right ) \frac {\partial \tau _{\textit{ji}}'}{\partial x_{\kern-1pt j}}}_{\textit{VI}} \\ & - \underbrace {\frac {p'}{\rho _0}\left ( u_{\kern-1pt j}' + \frac {\rho ' u_{0j}}{\rho _0} \right ) \frac {\partial \rho _0}{\partial x_{\kern-1pt j}}}_{\textit{VII}} + \underbrace {s'^2 \frac {\partial }{\partial x_{\kern-1pt j}} \left ( \frac {\rho _0 T_0 u_{0j}}{C_p} \right )}_{\textit{VIII}} + \underbrace {\frac {T'}{T_0} \left ( \tau '_{\textit{ji}}\frac {\partial u_{0i}}{\partial x_{\kern-1pt j}} + \tau _{0ji} \frac {\partial u_i'}{\partial x_{\kern-1pt j}} \right )}_{\textit{IX}}, \end{aligned} \end{align}

\begin{align} \begin{aligned} D_2 =& - \underbrace {\frac {p' u_{0j}}{C_p} \frac {\partial s'}{\partial x_{\kern-1pt j}}}_{I} - \underbrace {\rho ' u_{0i}\left ( u_{\kern-1pt j}' + \frac {\rho ' u_{0j}}{\rho _0} \right )\frac {\partial u_{0i}}{\partial x_{\kern-1pt j}}}_{\textit{II}} + \underbrace {\frac {T'}{T_0}\frac {\partial }{\partial x_{\kern-1pt j}} \left ( \frac {\mu _0 C_p}{\textit{Pr}} \frac {\partial T'}{\partial x_{\kern-1pt j}} + \frac {\mu ' C_p}{\textit{Pr}} \frac {\partial T_0}{\partial x_{\kern-1pt j}} \right )}_{\textit{III}}\\ &- \underbrace {\frac {T'}{T_0} \left ( \rho _0 T_0 u_{\kern-1pt j}' + \rho ' T_0 u_{0j} + \rho _0 T' u_{0j} \right )\frac {\partial s_0}{\partial x_{\kern-1pt j}}}_{\textit{IV}} + \underbrace {\rho _0 u_{0i}u_{\kern-1pt j}' \frac {\partial u_i'}{\partial x_{\kern-1pt j}}}_{V} + \underbrace {\left ( u_i'+\frac {\rho ' u_{0i}}{\rho _0} \right ) \frac {\partial \tau _{\textit{ji}}'}{\partial x_{\kern-1pt j}}}_{\textit{VI}} \\ & - \underbrace {\frac {p'}{\rho _0}\left ( u_{\kern-1pt j}' + \frac {\rho ' u_{0j}}{\rho _0} \right ) \frac {\partial \rho _0}{\partial x_{\kern-1pt j}}}_{\textit{VII}} + \underbrace {s'^2 \frac {\partial }{\partial x_{\kern-1pt j}} \left ( \frac {\rho _0 T_0 u_{0j}}{C_p} \right )}_{\textit{VIII}} + \underbrace {\frac {T'}{T_0} \left ( \tau '_{\textit{ji}}\frac {\partial u_{0i}}{\partial x_{\kern-1pt j}} + \tau _{0ji} \frac {\partial u_i'}{\partial x_{\kern-1pt j}} \right )}_{\textit{IX}}, \end{aligned} \end{align}

where,

![]() $\tau '_{\textit{ji}} = \mu _0 ( \partial u_{\kern-1pt j}'/\partial x_i + \partial u_i'/\partial x_{\kern-1pt j} ) - 2/3\mu _0 (\partial u_k'/\partial x_k) \delta _{\textit{ij}}$

. Hereafter, the various terms in

$\tau '_{\textit{ji}} = \mu _0 ( \partial u_{\kern-1pt j}'/\partial x_i + \partial u_i'/\partial x_{\kern-1pt j} ) - 2/3\mu _0 (\partial u_k'/\partial x_k) \delta _{\textit{ij}}$

. Hereafter, the various terms in

![]() $D_2$

will be referred to using the corresponding underscored roman numerals. The entirety of

$D_2$

will be referred to using the corresponding underscored roman numerals. The entirety of

![]() $D_2$

captures all disturbance energy production and dissipation mechanisms of any fluctuating mode, thus identifying the causes of instability growth. Note that we have used the linear approximation to replace the expression

$D_2$

captures all disturbance energy production and dissipation mechanisms of any fluctuating mode, thus identifying the causes of instability growth. Note that we have used the linear approximation to replace the expression

![]() $(\gamma -1)/\gamma \,(p'/p_0) + s'/C_p$

in Roy & Scalo (Reference Roy and Scalo2025, see p. 15) with

$(\gamma -1)/\gamma \,(p'/p_0) + s'/C_p$

in Roy & Scalo (Reference Roy and Scalo2025, see p. 15) with

![]() $T'/T_0$

in terms

$T'/T_0$

in terms

![]() $\textit{III},\textit{IV}$

and

$\textit{III},\textit{IV}$

and

![]() $\textit{IX}$

, to highlight the role of temperature fluctuations in the modal growth phase of the second modes. The reader is directed to Roy & Scalo (Reference Roy and Scalo2025) for calculations related to the terms

$\textit{IX}$

, to highlight the role of temperature fluctuations in the modal growth phase of the second modes. The reader is directed to Roy & Scalo (Reference Roy and Scalo2025) for calculations related to the terms

![]() $\partial s'/\partial x_{\kern-1pt j},\,\partial s_0/\partial x_{\kern-1pt j}$

or

$\partial s'/\partial x_{\kern-1pt j},\,\partial s_0/\partial x_{\kern-1pt j}$

or

![]() $s'$

.

$s'$

.

The definition of a suitable energy norm has been the subject of much debate, and many definitions of disturbance energy have been suggested, aimed at highlighting specific energy components (George & Sujith Reference George and Sujith2012). In particular, the inclusion of the mean flow effects (term

![]() $iii$

in (3.2)) has received much scrutiny, as this term is not strictly positive definite, rendering the chosen perturbation energy definition inappropriate as a norm. An energy norm, especially in the context of assessing the stability of a dynamical system, is a measure of how much a disturbed state deviates from an equilibrium state, and by definition, it is positive definite. However, our aim is to describe the mechanisms of instability growth, and thus, our focus is on capturing all the relevant physics contributing to the energy of a disturbance wavepacket. Our prior work demonstrated that the mean flow effects dominate the growth of instabilities in a high-speed BL, and therefore, should be included in a disturbance budget metric (Roy & Scalo Reference Roy and Scalo2025). There, we used the perturbation energy (3.1) to close the second-mode energy budgets and described the saturation of instability growth due to nonlinear effects. In the present work, we use this equation to gain a deeper insight into the mechanisms by which second-mode instabilities gain energy and how these mechanisms depend on the wall temperature.

$iii$

in (3.2)) has received much scrutiny, as this term is not strictly positive definite, rendering the chosen perturbation energy definition inappropriate as a norm. An energy norm, especially in the context of assessing the stability of a dynamical system, is a measure of how much a disturbed state deviates from an equilibrium state, and by definition, it is positive definite. However, our aim is to describe the mechanisms of instability growth, and thus, our focus is on capturing all the relevant physics contributing to the energy of a disturbance wavepacket. Our prior work demonstrated that the mean flow effects dominate the growth of instabilities in a high-speed BL, and therefore, should be included in a disturbance budget metric (Roy & Scalo Reference Roy and Scalo2025). There, we used the perturbation energy (3.1) to close the second-mode energy budgets and described the saturation of instability growth due to nonlinear effects. In the present work, we use this equation to gain a deeper insight into the mechanisms by which second-mode instabilities gain energy and how these mechanisms depend on the wall temperature.

3.2. Mathematical framework for acoustic ray kinematics

Here, we describe the acoustic ray-tracing method used to describe the trapped nature of second-mode instabilities. The prevailing notion in the community is that the presence of a region where the second modes propagate supersonically relative to the base flow traps the modes by acting as a waveguide (Mack Reference Mack1975; Saric et al. Reference Saric, Reshotko and Arnal1998; Fedorov & Tumin Reference Fedorov and Tumin2011). In this work, we aim to investigate this phenomenon further and determine the characteristics of the base flow that are responsible for the entrapment of the second modes.

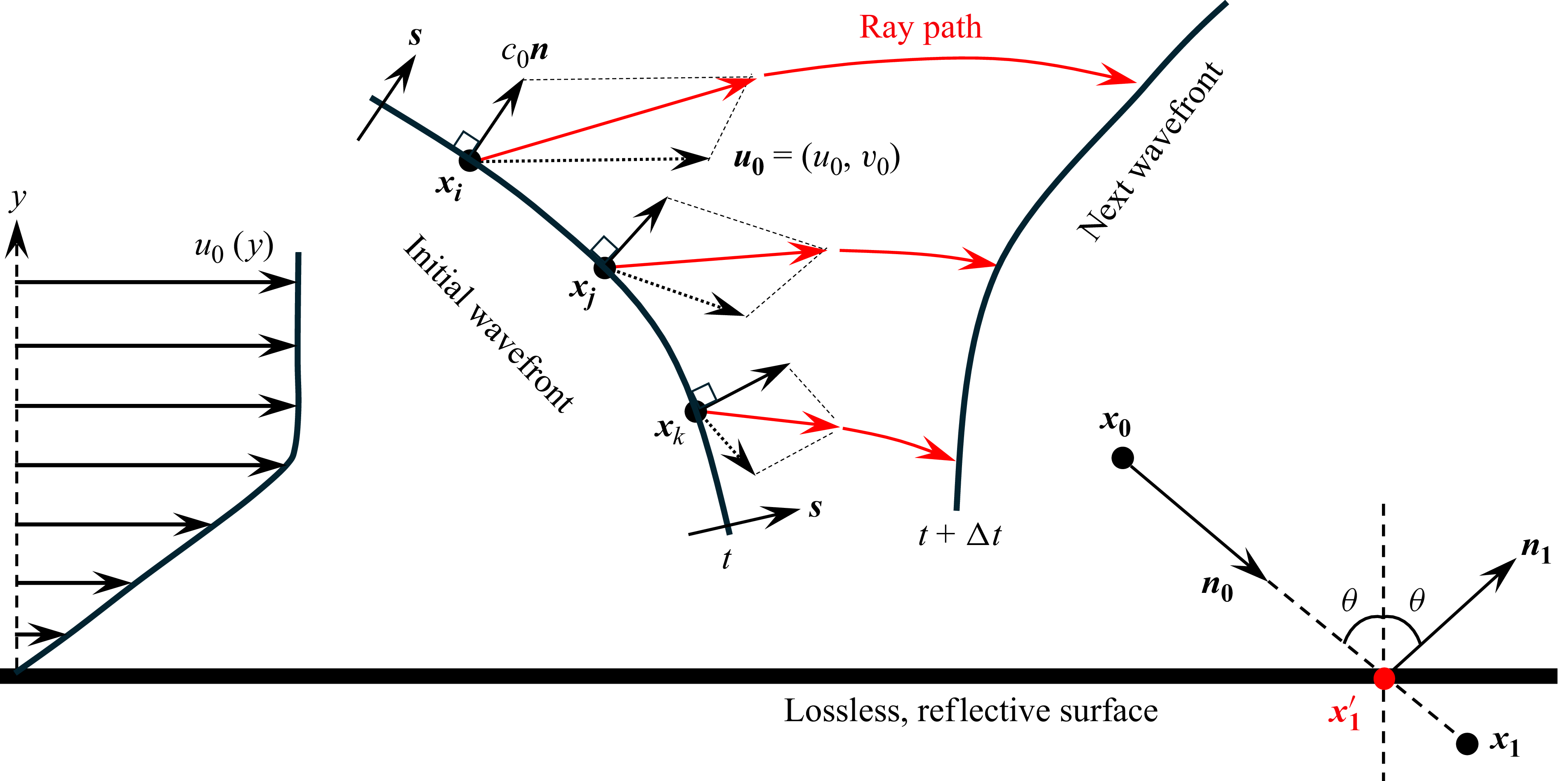

The theory of wavefront propagation assumes that acoustic rays propagate with the local sound speed relative to an inertial reference frame moving with the ambient flow (Pierce Reference Pierce2019), as shown in figure 5. The kinematic expression describing a ray path in a moving medium is given as

![]() ${\rm d}\boldsymbol{x}/{\rm d}t=\boldsymbol{u_0}+c_0\boldsymbol{n}$

, where

${\rm d}\boldsymbol{x}/{\rm d}t=\boldsymbol{u_0}+c_0\boldsymbol{n}$

, where

![]() $\boldsymbol{u_0} (\boldsymbol{x})$

describes the mean flow vector, and

$\boldsymbol{u_0} (\boldsymbol{x})$

describes the mean flow vector, and

![]() $\boldsymbol{n}(\boldsymbol{x})$

is the normal vector representing the direction of the ray. This is applicable for any medium moving at subsonic or supersonic speed (Uginčius Reference Uginčius1972). At any point

$\boldsymbol{n}(\boldsymbol{x})$

is the normal vector representing the direction of the ray. This is applicable for any medium moving at subsonic or supersonic speed (Uginčius Reference Uginčius1972). At any point

![]() $\boldsymbol{x}=(x,y)$

on the wavefront, knowledge of

$\boldsymbol{x}=(x,y)$

on the wavefront, knowledge of

![]() $\boldsymbol{n}$

will allow one to trace the paths of individual rays constituting the wavefront (see figure 5). The equations governing the ray kinematics (Pierce Reference Pierce2019) are given as

$\boldsymbol{n}$

will allow one to trace the paths of individual rays constituting the wavefront (see figure 5). The equations governing the ray kinematics (Pierce Reference Pierce2019) are given as

where the vector,

![]() $\boldsymbol{s}=\boldsymbol{n}/ ( c_0 + \boldsymbol{u_0}\boldsymbol{\cdot } \boldsymbol{n} )$

, is parallel to the normal vector

$\boldsymbol{s}=\boldsymbol{n}/ ( c_0 + \boldsymbol{u_0}\boldsymbol{\cdot } \boldsymbol{n} )$

, is parallel to the normal vector

![]() $\boldsymbol{n}$

and inversely proportional to the phase speed of the ray. The two equations above represent the time rate of change of the position

$\boldsymbol{n}$

and inversely proportional to the phase speed of the ray. The two equations above represent the time rate of change of the position

![]() $\boldsymbol{x}$

and the direction

$\boldsymbol{x}$

and the direction

![]() $\boldsymbol{s}$

of the ray. The ray paths are the characteristic curves of the eikonal approximation to the wave equation. The eikonal equation, a partial differential equation (PDE) derived from the acoustic wave equation, describes the evolution of phase fronts of acoustic waves using Fermat’s principle. The characteristics of the eikonal PDE are the ray trajectories, and (3.5) represents the characteristic ODE obtained from the eikonal PDE. It is worthwhile to note that (3.5) is purely kinematic, with no thermodynamic effects accounted for.

$\boldsymbol{s}$

of the ray. The ray paths are the characteristic curves of the eikonal approximation to the wave equation. The eikonal equation, a partial differential equation (PDE) derived from the acoustic wave equation, describes the evolution of phase fronts of acoustic waves using Fermat’s principle. The characteristics of the eikonal PDE are the ray trajectories, and (3.5) represents the characteristic ODE obtained from the eikonal PDE. It is worthwhile to note that (3.5) is purely kinematic, with no thermodynamic effects accounted for.

Figure 5. Schematic of the ray kinematics-based wavefront tracking methodology. From the frame of reference of the moving base flow

![]() $(\boldsymbol{u_0})$

, sound waves will travel at the local speed of sound

$(\boldsymbol{u_0})$

, sound waves will travel at the local speed of sound

![]() $(c_0(\boldsymbol{x_i})\boldsymbol{n})$

. Based on this principle, the ray kinematics approach tracks the propagation of a wavefront in time. A lossless, specular reflection is assumed when the rays hit the bottom wall.

$(c_0(\boldsymbol{x_i})\boldsymbol{n})$

. Based on this principle, the ray kinematics approach tracks the propagation of a wavefront in time. A lossless, specular reflection is assumed when the rays hit the bottom wall.

Thus, starting from an initial position

![]() $\boldsymbol{x_0}=(x_0,y_0)$

and an initial direction

$\boldsymbol{x_0}=(x_0,y_0)$

and an initial direction

![]() $\boldsymbol{n_0}=(n_x,n_y)$

, one can integrate (3.5) for all the subsequent ray positions

$\boldsymbol{n_0}=(n_x,n_y)$

, one can integrate (3.5) for all the subsequent ray positions

![]() $(\boldsymbol{x})$

and directions

$(\boldsymbol{x})$

and directions

![]() $(\boldsymbol{s})$

. For the present study, the ray kinematics equations are solved in two dimensions due to the axisymmetric nature of the base flow. Special care is taken to account for the reflection of the rays at the bottom wall. Due to the discrete numerical integration, a ray, located at

$(\boldsymbol{s})$

. For the present study, the ray kinematics equations are solved in two dimensions due to the axisymmetric nature of the base flow. Special care is taken to account for the reflection of the rays at the bottom wall. Due to the discrete numerical integration, a ray, located at

![]() $\boldsymbol{x_0}$

at time step

$\boldsymbol{x_0}$

at time step

![]() $t^n$

, may be estimated at the next time step

$t^n$

, may be estimated at the next time step

![]() $t^{n+1}$

to cross the cone surface and occur at

$t^{n+1}$

to cross the cone surface and occur at

![]() $\boldsymbol{x_1}$

with

$\boldsymbol{x_1}$

with

![]() $y_1\lt 0$

. The ray is then retraced back from

$y_1\lt 0$

. The ray is then retraced back from

![]() $\boldsymbol{x_1}$

, to find a new point

$\boldsymbol{x_1}$

, to find a new point

![]() $\boldsymbol{x^\prime _1}$

, where

$\boldsymbol{x^\prime _1}$

, where

![]() $y^\prime _1=0$

(see figure 5). If the initial ray direction is given as

$y^\prime _1=0$

(see figure 5). If the initial ray direction is given as

![]() $\boldsymbol{n_0}=(\sin \theta , -\cos \theta )$

, the direction of the reflected ray will be

$\boldsymbol{n_0}=(\sin \theta , -\cos \theta )$

, the direction of the reflected ray will be

![]() $\boldsymbol{n_1}=(\sin \theta , \cos \theta )$

, assuming regular reflection. The ray travel time is accordingly updated, and the integration is continued using the post-reflection updated ray parameters

$\boldsymbol{n_1}=(\sin \theta , \cos \theta )$

, assuming regular reflection. The ray travel time is accordingly updated, and the integration is continued using the post-reflection updated ray parameters

![]() $(\boldsymbol{x^\prime _1},\boldsymbol{n_1})$

.

$(\boldsymbol{x^\prime _1},\boldsymbol{n_1})$

.

The application of the acoustic ray-tracing approach is limited to short-wavelength waves, i.e. waves with wavelengths much lower than the characteristic length scale of the problem. This is because wave phenomena, such as diffraction and scattering, which lead to wavefront distortion, are more prominent at lower frequencies and cannot be accounted for using this approach. As the wavelengths of the second-mode waves are comparable to the BL height (the characteristic length scale in this context), the short-wavelength approximation is therefore questionable, challenging the validity of ray acoustics. However, the absence of surface aberrations, the slow growth of the BL, and the smooth variation of the mean flow across the BL allow the rays to experience a gradual change in their trajectories without encountering abrupt diffraction and scattering effects. Thus, the short-wavelength limit, typically required to avoid the wavefront distortion effects, is not strictly necessary in the present analysis.

Another limitation of the ray-tracing approach is the formation of caustics, i.e. locations where individual rays cross paths. Kriegsmann & Reiss (Reference Kriegsmann and Reiss1983) showed that caustic formation leads to a larger acoustic field, which is underpredicted by the geometrical acoustics approach. However, in this study, the ray-tracing method is not used to predict the entire acoustic field in the BL, given the availability of DNS data. We use the ray-tracing approach to describe the kinematic behaviour of individual acoustic rays and how the hypersonic mean flow affects their trapping. Since caustic formation does not influence the trajectory of individual rays, it is not expected to affect the present analysis. In § 4, we show that ray acoustics effectively describes the entrapment of acoustic rays in the BL.

4. Kinematics of second modes: wave trapping and resonance formation

This section analyses the trapping of acoustic rays in the BL using the wavefront tracking approach outlined above.

4.1. Trapped acoustic waves in a hypersonic boundary layer

The second-mode instabilities have a distinct signature, forming rope-like structures near the BL edge. These structures have been observed in numerous experimental investigations (Demetriades Reference Demetriades1974; Stetson & Kimmel Reference Stetson and Kimmel1993; Laurence, Wagner & Hannemann Reference Laurence, Wagner and Hannemann2016), as they arise from the high magnitude density gradients associated with temperature fluctuations. In figure 6

![]() $(a{-}c)$

, the temperature fluctuation contours of the convecting second-mode instabilities are presented for three successive times. The contours reveal a double-deck structure, with a layer of temperature disturbances concentrated near the BL edge (associated with the rope-like structures) and another layer beneath it.

$(a{-}c)$

, the temperature fluctuation contours of the convecting second-mode instabilities are presented for three successive times. The contours reveal a double-deck structure, with a layer of temperature disturbances concentrated near the BL edge (associated with the rope-like structures) and another layer beneath it.

Figure 6. Evolution of the second-mode instabilities at three successive times

![]() $(a-c)$

showing the double-deck structure, along with the corresponding temporal

$(a-c)$

showing the double-deck structure, along with the corresponding temporal

![]() $(d)(i)$

and spatial

$(d)(i)$

and spatial

![]() $(d)( \textit{ii})$

power spectra of the wall-pressure fluctuations. Data are taken from the cooled wall case

$(d)( \textit{ii})$

power spectra of the wall-pressure fluctuations. Data are taken from the cooled wall case

![]() $(\varTheta =0.25)$

, with a forcing amplitude of

$(\varTheta =0.25)$

, with a forcing amplitude of

![]() $A_0=10^{-2}$

(m s−1). The instabilities being trapped underneath the BL cause their wavenumber to lock to the BL thickness

$A_0=10^{-2}$

(m s−1). The instabilities being trapped underneath the BL cause their wavenumber to lock to the BL thickness

![]() $(k\delta _{\textit{BL}}\approx 0.5)$

resulting in the frequency

$(k\delta _{\textit{BL}}\approx 0.5)$

resulting in the frequency

![]() $(f)$