Election outcomes shape the actions of elected officials, candidates, bureaucrats, and voters (for example, Ferejohn Reference Ferejohn1986; Besley Reference Besley2007; Adolph Reference Adolph2013). Previous studies have established that campaign donations influence politicians’ actions (Gilens Reference Gilens2012; Powell Reference Powell2012; Weschle Reference Weschle2022), but less attention has been placed on whether and how election results alter donors’ behaviour. If donors support a candidate for office, how does the candidate’s electoral performance affect donors’ future contributions? Does it depend on whether donors expected an economic benefit in return for their support or simply wanted to express their political preferences? We address these questions in the context of developing democracies, where donors’ behaviour has not yet been studied. Knowing how election outcomes shape future contributions is key to understanding how the influence of money in politics evolves over time and how election results affect citizens’ political participation.

We argue that donors’ behaviour and its relationship with election outcomes depend on the electoral context and what motivated them to donate originally. Donors can act as investors seeking economic benefits in return for their contributions, or as consumers if their contributions are not tied to an expectation of such benefits (Francia et al. Reference Francia, Green, Herrnson, Powell and Wilcox2003; Ansolabehere, De Figueiredo and Snyder Reference Ansolabehere, De Figueiredo and Snyder2003; Gordon, Hafer and Landa Reference Gordon, Hafer and Landa2007). A key piece of our argument is that in democracies with weak party systems and non-programmatic races, and where low incomes do not allow citizens to express political support with small donations, the set of consumer donors shrinks to those who have personal ties to the candidate, such as family members or close friends. In such environments, weaker institutional arrangements that fail to prevent corruption could also boost the relative importance of investor donors in political campaigns. Our main contribution is to study how electoral outcomes affect donors’ behaviour in such contexts, where personal loyalties and profit motives dominate partisanship, ideology, and programmatic appeals as drivers of campaign contributions.

Our first theoretical observation is that investor donors will be more likely to continue donating if the initial investment (contribution) brings a return – that is, if they receive a benefit (for example, a government contract) after the supported candidate takes office. This is expected given the increased resources available for future investments or the accrued learning on how to gain benefits by donating that comes from previous successful quid pro quos. Yet, for consumer donors – whose contributions are linked to the personal relationship with the candidate in these contexts – the election outcome determines future donations because this often influences whether the same candidate will run again. If there are term limits and the winner cannot run again, donating to the winner will reduce their likelihood of donating again since personal loyalty, by definition, does not transfer easily to other candidates.

These expectations differ from those derived from extant theories of political participation applied to campaign donations, which implicitly assume institutionalized contexts with stable and ideologically coherent parties. Such theories emphasize how contributing to a winning campaign can increase the perceived importance of the donor’s actions in the electoral process, which in turn incentivizes further donations (Valentino, Gregorowicz and Groenendyk Reference Valentino, Gregorowicz and Groenendyk2009). These arguments support findings from the US context that donors to the election winner are likely to continue donating in the future even if the candidate they previously supported is not running for re-election (Peskowitz Reference Peskowitz2017; Dumas and Shohfi Reference Dumas and Shohfi2020). We believe these explanations account for the observed patterns in the US since most donations are expressive (Ansolabehere, De Figueiredo and Snyder Reference Ansolabehere, De Figueiredo and Snyder2003), partisan, and ideological (Barber Reference Barber2016; Hill and Huber Reference Hill and Huber2017; Barber, Canes-Wrone and Thrower Reference Barber, Canes-Wrone and Thrower2017). We are interested, however, in understanding whether the personalistic nature of campaigns and other characteristics of elections in developing contexts alter current theories’ expectations.

Using data from the 2011 and 2015 mayoral elections in Colombia – a context characterized by non-ideological races, a weak party system, and no re-election, we document that donating to the winner strongly decreases the likelihood that a donor will contribute to a campaign in the next local election. Using a close-election regression discontinuity (RD) design, we find that the fraction of donors to winning candidates in 2011, who donated again in 2015, is 14 percentage points (pp) smaller than that of donors to runners-up. This can be explained by donors moved by personal loyalty to the winner not being able to donate to the same candidate in the next election due to the reelection restriction (as well as donors to the runner-up contributing to the same candidate if s/he runs again) and investor donors to the winner not receiving an expected benefit.

Exploring the mechanisms driving this finding, we study whether consumer and investor donors exhibit donation patterns aligned with our theoretical priors. In particular, the consumer donors, who are moved by personal loyalty to the supported candidate, should be less likely to donate in future races where their previously supported candidate does not run, and investor donors should continue donating if they received an economic benefit from a supported elected official.

To examine these implications, we first need to identify groups of donors in the data that are close to the representative investor and consumer donors. We show that some donors benefit financially from campaign contributions (non-family donors) and identify a separate set of donors who could be relatively more driven by personal ties to the candidate, the candidate’s family donors. We analyze campaign finance and government procurement data that allows us to link public contracts to individual donors and take advantage of rules that prohibit public officials’ family members from contracting with the state. Using a close-elections RD design, we find that while non-family donors to the election winner obtain economic benefits via municipality contracts, family members do not – even though family members make much more generous donations. Because family donors to the winner could benefit financially from having a relative as mayor through other channels, we check whether they are more likely to be awarded contracts from the national, state government, or other municipalities (where mayors have more limited influence), or to run as candidates in the next election than family donors to the runner-up. We find that neither is the case. This evidence cannot completely rule out that mayors’ family donors benefit economically in ways that we cannot observe, but it provides support for the working assumption that family donors more closely resemble representative consumer donors than non-family donors.

Consistent with our proposed mechanism, we find that family members who contribute to narrowly winning candidates are much less likely to make future contributions and that this effect is larger than that of non-family donors (those who benefit via public contracts). Using a selection-on-observables approach, we further show that receiving a contract from the municipality is linked to future donations among non-family member donors to the mayor. A donor to the mayor who receives a contract is 4.4 pp more likely to donate in the next election than one who did not obtain a contract.

Our empirical strategy makes it difficult to interpret this last relationship as causal. Because we do not observe donors’ wealth, an alternative explanation for the positive relationship between receiving a contract and future non-family donations to the mayor is that owners of successful businesses are both better positioned to obtain contracts and wealthier individuals inclined to donate in every election. If this is what is driving the results, donors to a losing candidate who receives a public contract should also be likely to donate in the next election. We show, however, that donors to the runner-up candidate who receives a municipality contract are not more likely to contribute to a candidate in the next local election. In line with this finding, a sensitivity analysis (Cinelli and Hazlett Reference Cinelli and Hazlett2020) shows that a confounder three times as strong as the donation in 2011 – arguably the most important control in our regressions – would not change the conclusion that donors to the mayor who receive a municipality contract are more likely to donate in the next election.

In addition to offering an appropriate context to examine our claims, the Colombian case provides empirical advantages for studying donors’ motivations. Recent efforts to increase transparency have made campaign finance and government procurement information available, allowing us to match public contracts to donors using a unique ID. This approach offers at least three advantages to studying donations as investments relative to roll-call-based analyses, common in the literature on money in politics. First, individual contracts directly benefit a particular donor, unlike regulatory or legislative changes that affect entire economic sectors. Second, roll-call analyses fail to account for donors’ influence earlier in the legislative process (Powell Reference Powell2012). Third, legislative changes favouring donors can reflect shared policy preferences between donors and legislators rather than quid pro quo exchanges (Fox and Rothenberg Reference Fox and Rothenberg2011), a less pressing concern with local public procurement.

Our focus on the financing of mayoral campaigns in a developing democracy contributes to a literature that has thus far largely centred on federal elections in industrialized democracies (Samuels Reference Samuels2001; Anzia Reference Anzia2019).Footnote 1 Several studies have explored the drivers of individual donations in the US (Francia et al. Reference Francia, Green, Herrnson, Powell and Wilcox2003; Ansolabehere, De Figueiredo and Snyder Reference Ansolabehere, De Figueiredo and Snyder2003; Gordon, Hafer and Landa Reference Gordon, Hafer and Landa2007; Adam, Richter and Schaufele Reference Adam, Kelleher and Schaufele2013; La Raja and Schaffner Reference Raja2015; Barber Reference Barber2016; Hill and Huber Reference Hill and Huber2017; Barber, Canes-Wrone and Thrower Reference Barber, Canes-Wrone and Thrower2017; Stuckatz Reference Stuckatz2022), but there has been no theoretical or empirical analysis of such determinants in other contexts to date.Footnote 2 To our knowledge, our paper is the first to explore the determinants of donors’ behaviour in developing democracies. Our findings illustrate that individual donations evolve over time differently in such contexts than what prior research in established democracies finds.

Our paper also advances research on the influence of money in politics (for example, Powell Reference Powell2012; Fouirnaies and Hall 2018; Li Reference Li2018)Footnote 3 and campaign finance and corruption (Fazekas and Cingolani Reference Fazekas and Cingolani2017; Figueroa Reference Figueroa2021; Hummel, Gerring and Burt Reference Hummel, Gerring and Burt2019). Similar to recent findings in the literature pointing towards investment motivations driving donations (for example, Kalla and Broockman Reference Kalla and Broockman2016; Stuckatz Reference Stuckatz2022), others have presented evidence that public resource allocation is biased in favour of campaign donors to election winners in developing democracies (for example, Ruiz Reference Ruiz2017; Boas, Hidalgo and Richardson 2014; Gulzar, Rueda and Ruiz Reference Gulzar, Rueda and Ruiz2022). We contribute to this literature by demonstrating that such favouritism can persist over time by making those who benefited from the government more likely to donate in the future. Finally, our findings enhance our understanding of family members’ motivations for donating to relatives’ campaigns.

Election outcomes and future campaign donations

Existing theories of donor behaviour predict that donating to an election winner will encourage future donations. These theories highlight how contributing to a winner may increase an individual’s sense that her actions affect the outcome of the election, which motivates her to continue donating (Valentino, Gregorowicz and Groenendyk Reference Valentino, Gregorowicz and Groenendyk2009). These arguments are supported by evidence that successful political participation increases internal efficacy (Clarke and Acock Reference Clarke and Acock1989) and that greater efficacy induces more participation (Rosenstone and Hansen Reference Rosenstone and Mark Hansen1993).Footnote 4

This behavioural argument provides a plausible explanation for the increased incidence of future individual donations after donating to a winner documented in the US (Dumas and Shohfi Reference Dumas and Shohfi2020) – a country with strong party institutionalization and ideological races, and where most individual donations appear to be expressive and ideological (Ansolabehere, De Figueiredo and Snyder Reference Ansolabehere, De Figueiredo and Snyder2003; Barber Reference Barber2016; Hill and Huber Reference Hill and Huber2017; Barber, Canes-Wrone and Thrower Reference Barber, Canes-Wrone and Thrower2017).Footnote 5 After supporting a winner, a donor could experience a boost in efficacy that encourages a future donation – perhaps to a different candidate from the same party who shares similar policy priorities. It is important to highlight that in such an electoral setting, what encouraged the initial donation (that is, ideological alignment) is still likely present in the future election, but donating to the winner generates an additional utility-efficacy boost. But what are the expectations regarding future donors’ contributions elsewhere?

Where election campaigns are not programmatic, parties do not communicate a consistent message, and citizens’ low incomes prevent them from spending even small amounts to express support for a candidate, the set of consumer donors shrinks to those who have a strong personal connection to the candidate such as family members or friends. Since donations from consumer donors are based on personal loyalty rather than partisanship or policies, the behavioural argument does not offer a clear prediction regarding the effect of donating to the winner in future donation rates in these contexts. This is because giving to the winner might induce an efficacy boost that encourages future donations, but if the winning candidate does not run again because of term limits or other reasons, a consumer donor might not want to donate to anyone else. Whether donating to a winner promotes or hinders future donations depends on whether the efficacy boost outweighs the disutility of not being able to donate to the same candidate. The more important personal connections to the candidate are for consumer donors, the less likely is that those supporting the winner will donate in the future when the same candidate is not running.

Because investor donors seek to achieve other goals when contributing, electoral outcomes impact their future contributions differently. They will keep donating to political campaigns as long as their contributions continue to yield the expected financial benefits. For them, donating to the winner is not a sufficient motivation to make future contributions if the supported candidate does not reciprocate with a beneficial action. Although this expectation also applies to established democracies, weaker formal and informal norms against corruption boost the importance of investor donors in weakly institutionalized settings.

A positive donation experience motivates investor donors to contribute again for several reasons. First, when an investor donor is uncertain about which politicians are willing to engage in a quid pro quo, donating to one of them will increase her assessment of the probability of encountering another, encouraging more investment-motivated donations. Second, an investor donor may gain experience in a quid pro quo exchange that facilitates future similar engagements even with a different politician. For example, a donor who receives a public contract could learn how to better circumvent procurement rules that aim to limit politicians’ discretion in awarding contracts. A mayor interested in favouring their donors could provide information on how to increase the chances of the donor’s proposal being chosen, which can also be used in the future.Footnote 6 Lastly, receiving a financial reward increases the resources available for future donations. This is particularly important in countries where resources are scarce, as investor donors want to donate generously to outbid other donors competing for favours from future elected officials.

The previous discussion explains why we should not expect to find that donating to the winner of an election unconditionally encourages further donations. If the supported candidate wins and does not run again, donating to the winner could decrease the probability that consumer donors who are strongly moved by personal loyalty will make future donations, while for investor donors, receiving a financial reward should incentivize future donations. The following sections present evidence that is consistent with these expectations. Our analysis examines donations over time in municipal elections in Colombia, where parties are weak, ideology plays a limited role in local races, and mayors cannot run for reelection.

Colombian electoral context

Mayors in Colombia are elected under simple plurality rule every four years and cannot run for immediate re-election.Footnote 7 They oversee the execution of the municipality budget and the implementation of the annual development plan. Most public goods and services are provided through third parties that contract with the mayor’s office, which creates opportunities for mayors to repay donors by awarding them public contracts. The average value of public contracts awarded to donors is much larger than the average donation. A donor to the mayor receives on average 64 million Colombian pesos (MCOP) in public contracts from the municipality but has an average donation of 5.7 MCOP.Footnote 8 Contracts, however, cannot be given to parents, siblings, children, children-in-law, grandparents, in-laws, spouses, or grandchildren of the mayor, and the data reflect compliance with this rule. Only 0.81% of family members in our dataset of donors to mayoral races in 2011 received a contract.

Donors to mayoral candidates in Colombia’s 2011 elections generally contributed a large amount to a single candidate. Only 138 non-family donors (2.1%) gave money to more than one candidate and only 8 out of 2,850 family member donors contributed to multiple candidates. Unlike in the US, campaigns in Colombia do not rely on numerous contributions from small donors. Nearly three-quarters (72.4%) of non-family donors in our data set contributed more than the average monthly wage in the municipality; this percentage is even higher for family members (91%). These large donations are concentrated among a small number of individuals and represent an important share of total campaign revenues for the top candidates. The average campaign of the top two candidates in Colombia has five donors, and 59% of the campaign revenue comes from contributions (from family and nonfamily members).Footnote 9 In only 6% of these campaigns (mostly concentrated in the big cities), there are 10 or more donors. Low incomes also help explain why campaign donations are not a typical form of expressive political participation. In 2011, the average monthly wage was 1.19 MCOP ($609 US in 2011).Footnote 10

A weak party system and the nature of local policymaking make it difficult for ideological or partisan considerations to be drivers of donations in mayoral races. Local concerns and institutional constraints on municipal governments generally make ideology less important in local races (see, for example, Oliver Reference Oliver2012), a pattern that is even more pronounced in rural areas and small municipalities that are more prevalent in our sample. In Colombia, this is compounded by the fact that parties are not ideologically coherent (Botero and Alvira Reference Botero, Alvira, Wills-Otero and Batlle2012; Botero, Losada and Wills-Otero Reference Botero, Losada, Wills-Otero and Flavia2016). Reforms that introduced an open-list proportional representation electoral system in the 1990s and early 2000s encouraged intra-party competition and dramatically increased the number of parties (Pachón and Shugart Reference Pachón and Shugart2010; Shugart, Moreno and Fajardo Reference Shugart, Moreno and Fajardo2007). Moreover, a simultaneous process of fiscal decentralization gave mayors more resources, allowing them to create personal political organizations (Dargent and Muñoz Reference Dargent and Muñoz2011).

The weakness of the party system is reflected by the fact that only 25% of respondents identified with a political party in 2011 (LAPOP 2011), and only 33% of parties that ran candidates in the 2011 mayoral race did so again in 2015 in the same municipality. There are also high levels of party switching. Of the candidates who ran for mayor in 2011 and again in any local race in 2015, only 27% represented the same party.

Runner-up candidates are likely to run again in any local race in the next election (54.6%), while far fewer candidates who placed lower than second are likely to do so (28.3%). Moreover, runners-up have a high chance of winning if they run again. Of all runners-up in 2011 who ran again in the 2015 mayoral race, 56.5% won the election.

The previous observations are consistent with informal accounts of those involved in Colombian local races: in the average (small) municipality, donors to mayoral races tend to be family members, close friends, local small business owners, or independent contractors seeking municipality-level public contracts. Unlike the more studied US (federal) context, consumer donors in Colombia tend to have close personal connections to the candidate; they are not generally regular citizens who like the candidate and express their support with small contributions. The Colombian donors in each campaign are not ideological zealots or moved by partisanship, yet they give large donations in a context where incomes are low.Footnote 11

Data

We use the campaign funding information available on the National Electoral Commission’s website to identify donors who contributed to mayoral campaigns in 2011 and 2015. Electronic campaign finance reporting has been mandatory since 2009, and the National Electoral Commission fines candidates who do not comply with this rule.Footnote 12 Compliance is high: 89% of the 4,460 mayoral candidates in 2011 reported their campaign funding information, including all election winners. In addition, the dataset includes information on whether donors are family members of the candidate (candidates must disclose this information).

We use electoral data compiled by Pachón and Sánchez (Reference Pachón and Sánchez2014), gathered from the Colombian electoral authority, the Registraduría Nacional. This register contains the results of the 2011 elections for all municipalities and those of all local races in 2015. The data include key variables for the analysis, such as information on the winners, and allow us to examine the history of participation in elections and the record of candidates’ previous electoral victories, which we use in auxiliary analyses.

To gather evidence on donors’ investment rationale, we use public procurement data from Datos Abiertos, an online portal created to increase government transparency. These data contain the universe of public procurement contracts, including job contracts. We match each donor’s unique ID to the ID of the contractors in the municipality in which the candidate ran, which creates a link between the donor and a beneficiary of public resources or jobs (Ruiz Reference Ruiz2017). Since donors may receive contracts through associates, we discuss how such mismatches can affect our findings below.

We use mayoral candidates’ history of disciplinary sanctions from the Office of the Inspector General. Information on previous illegal voting practices (for example, impersonating a dead person to vote, registering to vote in a municipality where the voter does not reside, or trying to vote while underage) is taken from the National Registrar’s Office. Data from the Office of the Comptroller General also provide a record of sanctions for donors. Finally, data on candidates’ ideological leanings come from Fergusson et al. (2021).

Research design and estimation

We are interested in comparing the rate of future donations among donors to winning versus losing mayoral candidates. A challenge of interpreting such a comparison is that election winners and losers – and their donors – might differ in other characteristics that determine subsequent donations. For example, if election winners tend to be more corrupt, honest candidates could be deterred from running in the future, making those who donated to ‘cleaner’ but unsuccessful candidates less enthusiastic about contributing in the next election. Moreover, systematic differences between candidates who won versus those who lost might translate into systematic differences among their donors that correlate with their propensity to donate. We employ a close-elections RD design to address these concerns. Our forcing variable is the difference in vote shares of the top two candidates in the 2011 mayoral race.Footnote 13 If the determinants of future donations are smooth at the cutoff, the RD design allows us to estimate the average treatment effect at the cutoff of donating to the winner of the 2011 mayoral election on future donations.

Following recent recommendations in the literature (de la Cuesta and Imai Reference de la Cuesta and Imai2016; Cattaneo, Idrobo and Titiunik Reference Cattaneo, Idrobo and Titiunik2020), we report treatment effects estimated by taking the difference of (local) linear polynomial approximations of the average control and treatment responses at the cutoff. We use triangular kernels, which give more weight to observations near the cutoff. To manage the trade-off between reduced bias and larger variance associated with using samples closer to the cutoff, our baseline estimates use the bandwidth that minimizes the asymptotic mean squared error (MSE). Following Calonico, Cattaneo and Titiunik (Reference Calonico, Cattaneo and Titiunik2014), we report confidence intervals and p-values that account for the polynomial approximation and clustering at the municipality level. All main tables also include the results of global linear parametric estimates, Appendix F reports the parametric global quadratic specifications, and Appendix E presents local linear estimates computed using alternative bandwidths. Appendix D presents local and global RD plots where we use quantile-spaced bins and fit a third-degree polynomial (Calonico, Cattaneo and Titiunik Reference Calonico, Cattaneo and Titiunik2015).

To test some of our hypotheses, which rely on distinguishing family from non-family donors, our sample includes all top-two candidates in the 2011 mayoral race who had family or non-family donors (n = 1,150).Footnote 14 Of these candidates, 823 have non-family donors and 778 received contributions from family members. When we study the downstream effects of donating to the election winner on outcomes defined for only one type of donor, we use the sample of candidates with that type of donor. A concern is that bias could be introduced if the top two campaigns differ in the type of donors they seek, based on their anticipated contributions or what donors expect in return for their donations. However, Appendix A Table A1 verifies that there are no discontinuities at the victory cutoff in the probability of having either family or non-family donors. All RD regressions are run at the level at which the treatment is assigned, the candidate level. In Appendix G, we also report all RD results at the donor level. The results are substantively similar. Because there are mass points in the running variable at the donor level, however, this could affect the properties of the local linear estimator (Cattaneo and Titiunik Reference Cattaneo and Titiunik2022). A correction that increases the bandwidth precludes the use of optimal MSE bandwidths, an issue we do not have with the candidate-level results. In the same appendix, we also include results obtained using a selection on observables approach (controls are listed below) and run a similar analysis but comparing donors to the winner and the third-placed candidate. This last analysis helps us assess whether our claims generalize to comparisons of the winner and other loser candidates. While the main conclusions hold, we discuss differences in results in the appendix.

If continuity of potential outcomes – the main identification assumption – holds, we should not see ‘jumps’ in determinants of future donations at the cutoff. We apply the described estimation strategy with predetermined covariates as outcomes to verify this is the case and present the results in Table C1. Candidates who narrowly won or lost are on average similar in their electoral experience, whether they have held elected office in the past, campaign size, and prior malfeasance. We can also check for potential discontinuous jumps in many pre-treatment variables related to how campaigns are funded – variables not frequently available in other close-elections RD designs. This is an advantage, as it is possible that donors, who have better information than researchers regarding differences between the winning candidates and runners-up, reflect such differences in their contributions. Table C1 reports no significant discontinuities around the electoral victory threshold in campaign revenues, the number of donors, or the weight of donations in campaign revenues. We also check that the characteristics of the average donor to winners and runners-up are similar in close elections, and find that average individual donations and the fraction of donors sanctioned by the comptroller general do not jump at the victory threshold. The fact that we have this large set of pre-determined covariates and the results of the prior tests makes us more confident that our results are not subject to criticisms raised about other applications of RD designs in close elections.Footnote 15 Finally, we use a test of no manipulation of the density proposed by Matias D. Cattaneo and Ma (2020) to verify that the number of treated and control units is not significantly different at the cutoff (see Figure C1).

Mayoral races in Colombia are very competitive. This is an advantage, given that our design identifies the causal effects of donating to the winner only in municipalities where the runner-up barely lost and because we require more observations near the victory threshold for estimation. In 72% of the municipalities in our sample, elections were won by less than 10% of the top two candidates’ votes.Footnote 16 To assess how the municipalities used in our estimations differ from other Colombian municipalities, we compare their characteristics. Table C2 shows that in only 5 of the 25 variables considered we would reject equality of means at the 5% level. Close-election municipality governments have a smaller share of their resources in total revenues (about 8 pp difference) and a larger share of the population living in rural areas (5 pp). Also, their campaigns tend to be smaller in terms of donors and campaign revenue (by about 1 donor and 20 MCOP). These differences do not affect the study’s internal validity, but confirm that our findings are more directly applied to rural areas that cover most municipalities.

Result: donating to the winner reduces the likelihood of future donations

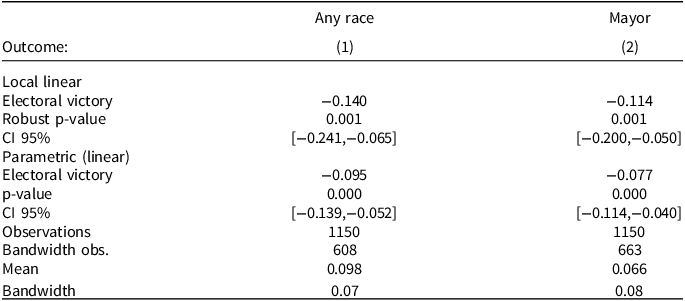

Column 1 of Table 1 illustrates that the fraction of donors to the mayor elected in 2011 who donated in 2015 to any local race is 14 pp smaller than that of donors to the runner-up. This is a large difference considering that the fraction of donors to the top two candidates who donated in 2015 is 9.8%. Column 2 reports similar results for models that only consider future donations to mayoral races in 2015 – that is, whether a donor in 2011 is more likely to contribute to a candidate in the same type of race in 2015.

Table 1. Effect of donating to an election winner on future donations

Local linear estimates of average treatment effects at the cutoff are estimated with triangular kernel weights and optimal MSE bandwidths. 95% robust confidence intervals and robust p-values with clustering at the municipality level are computed following Calonico, Cattaneo and Titiunik (Reference Calonico, Cattaneo and Titiunik2014). Parametric linear model specification includes the running variable and the interaction of the running variable with the treatment. Bandwidth obs. denotes the number of observations in the optimal MSE bandwidths.

If there is a boost in the perception of efficacy brought about by donating to the winner, these findings suggest such a boost does not compensate for the fact that the winner cannot run in the future and that someone who donated based on personal loyalty to that candidate will not want to donate again. Similarly, donors to the runner-up who are motivated by personal loyalty will be more likely to donate again if their favoured candidate runs in the next election, especially if she has a good chance of winning.Footnote 17 The finding could also reflect the fact that many investor donors to the winner are not receiving the financial benefits they expected. We now provide evidence in line with these interpretations.

Non-family donors and investment motivations

To examine whether our explanations of donor behaviour account for the negative relationship between donating to the winner and donating in the next election, we must 1) establish that some donors benefit financially from campaign contributions and 2) identify a set of donors who are not driven in the same way by financial incentives. This allows us to determine whether those who benefit economically after contributing to an election winner are more likely to donate in the future – and whether those who are not are driving the negative relationship found between contributing to the winner’s campaign and future donations.

This section shows that while non-family donors to the election winner obtain economic benefits in return for their contributions, family donors to mayors do not appear to receive such benefits – even though family members in our sample contribute 9 MCOP, on average, which is 50% more than the average contribution of a non-family member. We, therefore, consider family donors to more closely resemble a representative consumer donor – who is driven by personal attachments to the candidate – than non-family members when examining our theoretical expectations.

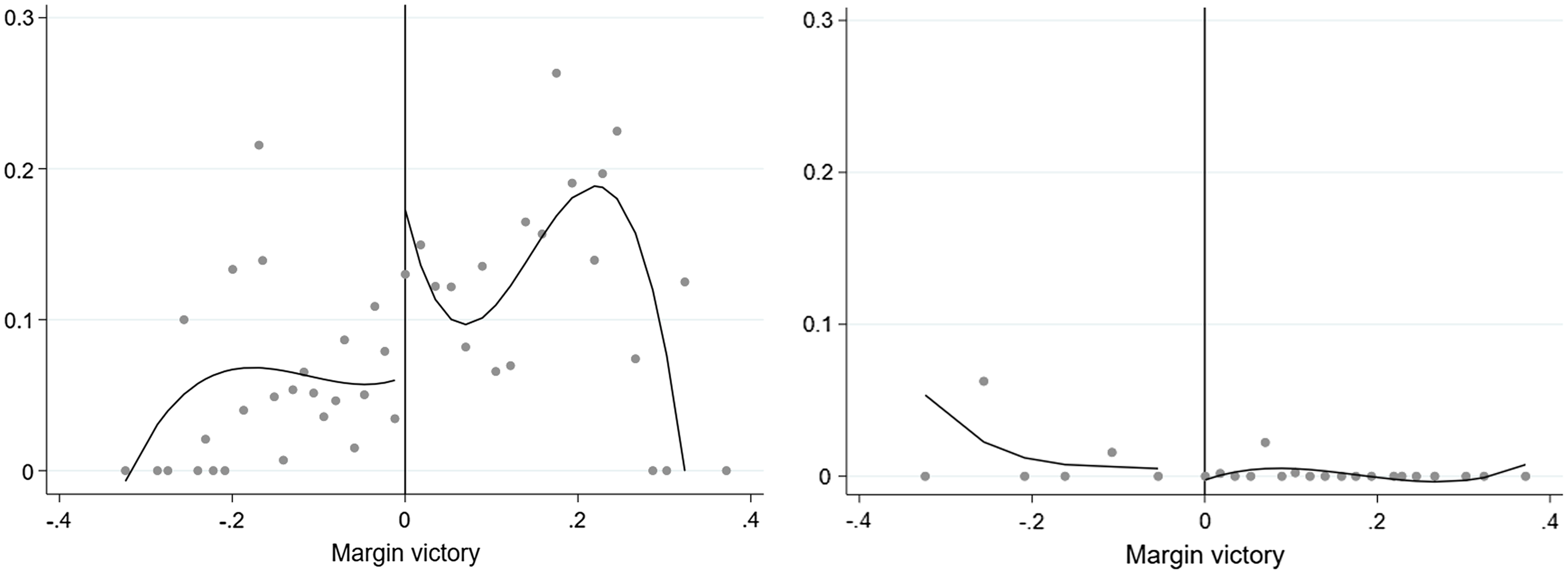

The left panel of Figure 1 displays the fraction of non-family donors who received a contract in a municipality as a function of the margin of victory. Dots to the right of the threshold (zero) represent the average fraction of donors to the winner who contracted with the municipality within a bin, while those on the left represent the same average fraction but for donors to the runner-up. There is a jump around the zero margin of victory, and more donors to the winner obtain contracts than donors to the runner-up. This is in line with what has been found in Brazilian legislative elections (Boas, Hidalgo and Richardson Reference Boas, Daniel Hidalgo and Richardson2014). The panel on the right presents the equivalent figure for family member donors. It shows that family donors to the winner are not more likely to receive contracts than family donors to the runner-up in close races; neither is likely to be awarded contracts.

Figure 1. Donating to the winner and public contracts (non-family and family).

Each dot represents the average fraction of donors receiving contracts in a bin. The line gives a polynomial fit of order 3.

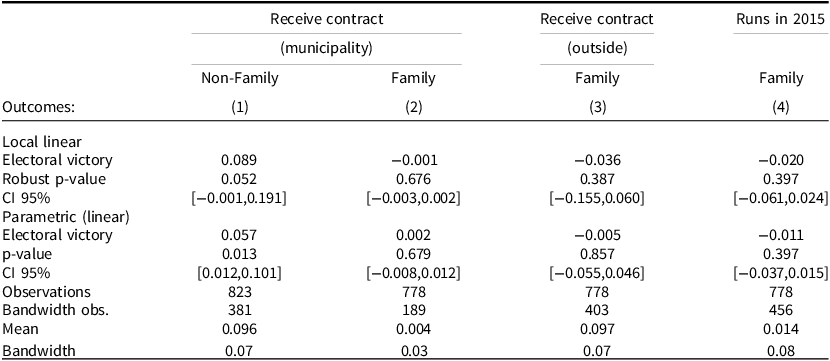

Table 2 presents RD estimates of the differences in economic benefits by donor type. The first column shows that non-family donors to the winner benefit via public contracts. The most conservative estimate indicates that 5.7 pp more donors to the winner receive a contract than donors to the runner-up. This is a large effect, as 9.6% of non-family donors to the top candidates receive contracts. There is no difference for family members.

Table 2. Effect of electoral victory on benefits to donors

Local linear estimates of average treatment effects at the cutoff are estimated with triangular kernel weights and optimal MSE bandwidth. Robust p-values with clustering at the municipality level and 95% robust confidence intervals are computed following Calonico, Cattaneo and Titiunik (Reference Calonico, Cattaneo and Titiunik2014). The parametric linear model specification includes the running variable and the interaction of the treatment with running variable.

Measurement errors and our inability to perfectly match all donors to public contracts are unlikely to explain these findings. For instance, mayors might try to hide payments to their donors by awarding the contracts to their donors’ associates. This incentive to conceal a quid pro quo is weaker when the mayor signs contracts with donors to the runner-up candidate, which suggests that the previous estimates could understate the true effect. The previous findings are also unlikely to be explained by family members of mayors not reporting themselves as such when registering their donations. For this to be the case, family members of the winner would have to conceal their family connection with the candidate more frequently than family donors to the runner-up in a close election. Since donations must be registered before the election, they cannot be changed after the result is announced. Furthermore, in close races, it is more difficult to anticipate which candidate will win, and family members of both winners and runners-up would have similar incentives to disclose their ties to the candidate. Finally, systematic differences in reporting campaign finance information between narrow winners and losers should be reflected in differences in the number of donors or campaign revenues, but such variables are smooth at the cutoff (see Table C1).

These results do not rule out the possibility that some family members donate in anticipation of receiving financial rewards. Since legal restrictions prevent mayors from assigning contracts to family members, family donors could find alternative ways to obtain a return on their donations. We explore this possibility by estimating the effect of donating to the election winner on the likelihood of receiving a public contract assigned by the national, the state (departamento) or other municipality governments. The intuition for this test is that although a mayor cannot directly contract with a family donor, they can influence other government agencies with fewer or no restrictions on assigning such contracts. As column 3 shows, we find no evidence in favour of that idea.

Election winners could also compensate family members for their donations by assisting them with their own political aspirations. However, the model in column 4 shows that there are no significant differences between the fraction of family donors to the winner who ran in any race in the 2015 elections (governor, department assembly, municipal council, or mayor) and that of family donors to the runner-up.

These patterns suggest that non-family (but not family) donors to the mayor reap economic benefits via municipality contracts. These findings are robust to alternative bandwidths for estimation, and to quadratic polynomial global RD parameterizations (see Appendices E and F). Since expressive motivations are likely to be stronger for family than for non-family donors, given these patterns, we expect family members’ donation behaviour to more closely resemble that theorized for consumer donors, who, in this context, are mainly driven by personal loyalty to the candidate.

Mechanisms

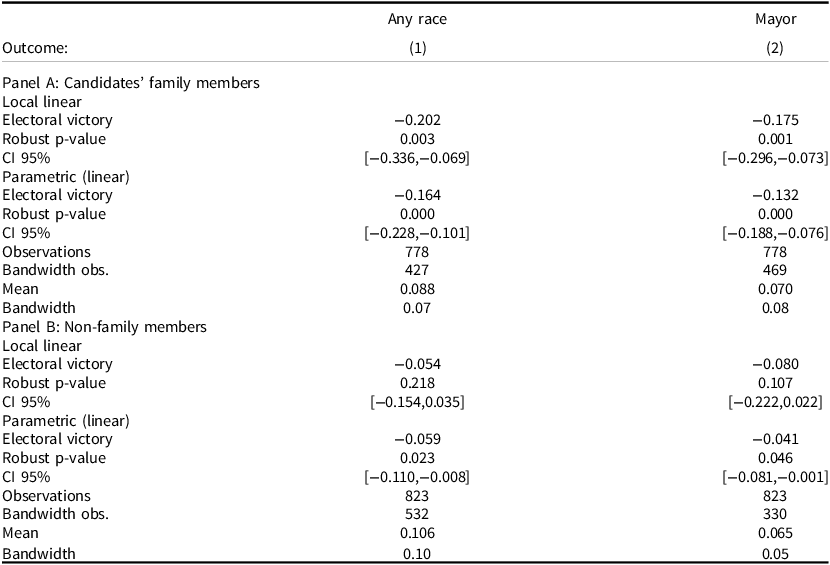

To examine whether differences in donors’ motivations account for observed donation patterns, we estimate the future donations model separately for family and non-family donors. Our argument implies that the difference in future donation rates between donors to the winner versus those to the runner-up reported above should be driven by those who donate based on personal loyalty. Consistent with this, we find that family members who donated to the mayor are 20.2 pp less likely to donate to any 2015 race than family members who contributed to the runner-up’s campaign. On the other hand, the (non-significant) point estimate is just 5.4 pp for non-family members, the donors who can (and do) benefit through contracts (see Table 3 column 1). We observe a similar pattern if we use the fraction of donors in 2011 who donated again to mayoral races in 2015 as an outcome (column 2). Appendix F Tables F4 and F5 demonstrate that the differences in the effects of donating to the winner between family and non-family donors are statistically significant using a global parametric approach.

Table 3. Effect of donating to an election winner on future donations (candidates’ family members vs. non-members)

Local linear estimates of average treatment effects at the cutoff are estimated with triangular kernel weights and optimal MSE bandwidth. Robust p-values with clustering at the municipality level and 95% robust confidence intervals are computed following Calonico, Cattaneo and Titiunik (Reference Calonico, Cattaneo and Titiunik2014). Parametric linear model specification includes the interaction of the treatment with the running variable and the running variable. Bandwidth obs. denote the number of observations in the optimal MSE bandwidth.

The negative effect of donating to the winner on future donations among family donors indicated that any positive impact of donating to the winner linked to an increase in perceived efficacy is outweighed by the disutility of not being able to donate again to the same term-limited candidate. Our analysis, however, does not tell us whether the efficacy boost exists in the first place. In Appendix H, we leverage the fact that (unlike mayors) municipality local councillors can run for immediate reelection (with no term limits) and that bare-seat winners and losers run again in the next election at similar rates to examine whether there is a positive effect of donating to the winner on future donations. Using a similar RD strategy as the one used so far with data from the 2011 local council race (held the same day as the mayoral race), we find no such effect. If anything, donors to the winner are weakly less likely to donate in the future. Together with the findings of Table 3, this suggests that donating to the winner determines future donations among consumer donors mainly because an electoral victory influences whether a term-limited candidate runs again.

Turning our attention to investor donors, our finding that donating to the mayor has a weaker impact on future donations for non-family donors is consistent with an investment rationale. This is because some investor donors to the winner should be encouraged to donate again if they receive a contract from the municipality. Receiving a contract then mediates the causal path between donating to the winner and future donations. Since we have already established that non-family donors to the winner are more likely to benefit from government contracts, we now explore whether those donors who receive contracts are indeed encouraged to donate again. We focus on the sample of non-family donors to the election winner in 2011 and test whether receiving a municipality contract during the mayor’s term affects the individual likelihood of future donations. We follow a selection of observables strategy and estimate linear probability models.Footnote 18

To estimate the impact of receiving a public contract on the probability that a donor to the mayor will contribute to a campaign in the future, we adjust for donor and mayor characteristics that might confound this relationship. For instance, wealthier donors can afford to contribute in the future and might own larger businesses that are better positioned to win government contracts. Although we do not have information on donors’ personal wealth, all of our models control for the size of the 2011 donation as well as proxies for donors’ malfeasance, such as whether the Office of the Comptroller General sanctioned them for violating laws governing public resources and whether they donated more than the legal limit. We also control for how the donor’s contribution ranks relative to all contributions to that candidate to capture his or her relative influence. Similarly, the characteristics of the elected candidate can also influence the type of candidate who runs in the next election and, therefore, future donations and contract assignments. For example, ‘clean’ candidates might be deterred from running where corrupt candidates are frequently elected, and corrupt candidates could raise more donations from those seeking to profit from their contributions. We, therefore, control for whether the candidate has engaged in illegal voting practices, has been sanctioned by the Office of the Inspector General, ran in previous elections, the number of elected posts previously held, the share of donations received as a percentage of campaign revenues, and whether she belongs to a party without a clear ideological leaning.

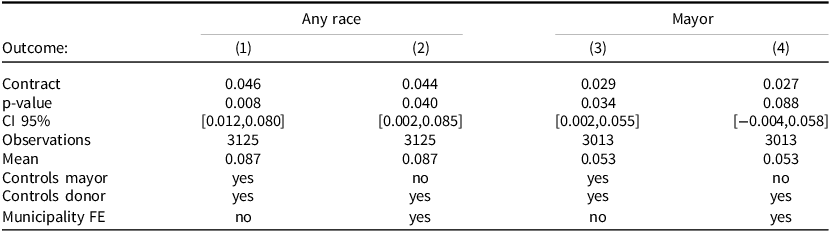

Column 1 of Table 4 shows a significant positive association between receiving a contract and donating to any race in 2015 among donors to the winner of the 2011 mayoral race. Receiving a contract is associated with a 4.6 pp increase in the probability that a donor to the mayor in 2011 will donate again in 2015. Column 2 reports the results of a regression that includes municipality fixed effects. This model accounts for unobserved municipality characteristics that can determine contract assignment and political participation, such as the level of development, state capacity, and democratic culture. Importantly, because the sample only includes donors to the mayor, these models allow us to compare donors to the same mayor with similar donation and malfeasance levels while varying whether they received a contract. The point estimates barely change.

Table 4. Effects of contracts on next election donations (non-family members)

Ordinary least squares (OLS) estimates of the effect of receiving a contract on donating in the next election. The sample includes non-family donors to the mayor. ‘Controls mayor’ denotes the candidate’s illegal registration of ID, being sanctioned by the Office of the Inspector General, elected posts, ran as a candidate in past elections, the party is not left-wing or right-wing, and non-family donations as a fraction of campaign revenue. ‘Controls donor’ denotes the logged value of the donation, donated above the legal limit, sanctioned, and rank of donation among all family and non-family donors. Confidence intervals and p-values with clusters at the municipality level.

The differences in the strength of the association between contracts and future donations by electoral race type are also consistent with an investment rationale. The positive association between receiving a contract and donating in any 2015 local race is maintained when the outcome is donating to a mayoral race in 2015 (columns 3 and 4), but the coefficients are smaller and less precisely estimated. Since donors in 2011 mostly supported only one mayoral candidate, and the likely 2015 mayoral race winner is the (unsupported) runner-up from 2011, an investor donor would have more reasons to donate to races other than the mayoral race. This is because elected mayors who want to reward their donors could prioritize loyal donors who had not previously supported a rival. The results in Appendix A Table A5 support this interpretation. When the outcome is a dummy that takes a value of 1 when a donor from 2011 contributed exclusively to the 2015 mayoral race (and not to a race for governor, department assembly, or council), the coefficient on receiving a contract is smaller and insignificant.

We face several challenges to conclude from these results that receiving a contract caused the increase in the likelihood of donations because of a donation-investment rationale. The first is that we might not be able to link contracts to donations perfectly, which creates measurement errors in our explanatory variable. However, if a donor to the mayor receives a contract through an associate (to avoid the appearance of a quid pro quo), it would appear in our dataset as a donor who did not receive a contract. This would underestimate the coefficient of receiving a contract when receiving a contract encourages future donations.

A separate concern is that although we included the 2011 donation as a control, the relationship we observe is explained by more successful business owners being wealthier and better able to win public contracts, and not by investor donors seeking another quid pro quo. If this was the case, we should also find a positive relationship between contracts and donations in 2015 for contract recipients who did not donate to the 2011 election winner but to another candidate. Table A4 shows that when we use the sample of donors to the runner-up, the coefficient on receiving a contract is either negative or much closer to zero, and is not significant. An alternative way to assess whether wealth or other potential unobservables are driving the positive association between receiving a contract and future donations is to conduct a sensitivity analysis (Cinelli and Hazlett Reference Cinelli and Hazlett2020) (results reported in Table B1). We find that confounding that is three times as strongly associated with contract assignment as the 2011 donation does not change the conclusion that receiving a contract makes a non-family donor more likely to donate to any race in 2015. The donation size in 2011 is perhaps the most important determinant of future donations, and it could determine contract assignment if the mayor rewards donors based on how much they contributed.Footnote 19

Conclusions

In this paper, we investigated how electoral outcomes impact campaign donors’ behaviour – a key aspect of understanding how elections affect citizens’ future political participation and how money’s influence in politics evolves over time. Prior research on the US case has shown that donors to winning candidates are encouraged by their candidate’s victory to continue contributing in future elections, even in non-reelection cycles. The explanations for these findings implicitly rely on the presence of strong parties and ideological races.

Where parties are weak, ideology does not play a significant role in elections, incomes are low, and institutional anti-corruption tools are not always effective; the set of consumer donors shrinks to those who donate based on personal loyalty, and the relative importance of donors seeking to profit from their contributions increases. As a result, campaign donors are either investors or citizens with a strong personal connection to the candidate. Given the composition of the donor pool, we should not expect the supported candidate’s electoral victory to unconditionally encourage future donations by her donors. If the supported candidate does not run again or investor donors do not profit from the election winners’ actions, future donations from those who supported the winner might be less likely.

We examine a dataset that links individual donors to contractors and find that donors to Colombia’s term-limited winners of the 2011 mayoral election were less likely to donate in the next election than donors to the runner-up. This pattern is weaker among non-family donors, who could legally receive economic benefits via municipality contracts during the mayor’s term. Importantly, non-family donors to the election winner are more likely to donate again if they receive a public contract than if they do not. In essence, a biased allocation of public resources favouring donors encourages them to seek similar benefits again.

There are some questions informed by our findings that future work could address. What determines the strength of perceptions of efficacy when donating to an election winner? Our auxiliary analysis of local councils revealed that even when bare seat winners and bare losers run at similar rates in the next election, donors to the bare winner are not more likely to donate in the next election. This suggests that the perceived sense of efficacy gained by donating to the winner could be moderated by characteristics of the electoral environment. A second unanswered question is how important it is for elected officials to reciprocate favours from their donors. Would reciprocal politicians be more likely to succeed? Are they more likely to run for and win higher-level elections? Answering these questions would give us a better understanding of the full role of money in politics.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S000712342400036X.

Data availability statement

Replication materials for this article can be found in Harvard Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/TQLONO.

Acknowledgements

We thank Leonardo Arriola, Brian Palmer-Rubin, Guillermo Rosas, and seminar audiences at the 2021 APSA panel on campaign finance in developing democracies, the 2022 Danish Political Science Association Annual Meeting, Emory, Essex, the 2021 EPSA panel on discontinuities in politics, Georgia Institute of Technology, Latin American Polmeth 2021, CBS Money in Politics Conference 2022, the 2022 MPSA panel on Clientelism, Programmatic Policies, and Local Politics, NYU, University of Gothenburg, Universidad de San Andrés, and Universidad Torcuato Di Tella. The comments from the editor and three anonymous reviewers also significantly improved this article.

Financial support

Nelson A. Ruiz acknowledges the support of the Leverhulme Trust. This research was funded in part by the Leverhulme Trust: Leverhulme Early Career Fellowship (Grant No. ECF-2021-258).

Competing interests

None.