Introduction

The aim of this article is to reconstruct lines 75–80 of Tablet V of the Standard Babylonian version of the Epic of Gilgameš (SBG) by a re-reading of all extant sources and by recourse to verses 9–12 in Chapter 4 of the Book of Qohelet (Ecclesiastes).Footnote 1 To achieve this aim, the first section will present the history of scholarship around a shared saying about the three-ply rope in SBG V 76 and Qoh 4:12. It will demonstrate how in the past a verse of Qohelet had served in reconstructing the meaning of a half-preserved line in the Epic of Gilgameš.

The second section will present a textual reconstruction, commentary and translation of SBG V 75–80. In the third section a comparison between SBG V 75–80 and Qoh 4:9–12 will be provided. The closeness of the two sources will be demonstrated. The fourth section will briefly discuss the relationship between the Epic of Gilgameš and the Book of Qohelet.

1. The Three-ply Rope in Gilgameš and the Book of Qohelet

One of the best well-known examples demonstrating the ties between the sources of Gilgameš and the Book of Qohelet is the saying about the three-ply rope.Footnote 2 Qoh 4:12b, SBG V 79 and line 108 of the Sumerian composition Gilgameš and Huwawa (A), upon which the SBG line probably depends, include these phrases.

All sources assess the nature of true friendship between two men. They employ to that effect a particular saying or proverb as a metaphor of the vehicle ‘Friendship’, resulting in a formulation ‘Friendship is X’. The saying claims that friendship is a three-ply cord that cannot be easily cut. The three-ply cord metaphor in all sources is far too particular to be considered accidental.Footnote 3

It was Kramer (Reference Kramer1947) first who rather modestly recognized the similarity of the Qohelet half-verse to the Sumerian source.Footnote 4 Shaffer (Reference Shaffer1967) acknowledging in a footnote Kramer’s observation, arrived at the same conclusion, and most importantly corrected Kramer’s reading of TÚG, ‘cloth’ to ÉŠ, ‘rope’ (see above, Gilgameš and Huwawa (A), 108), leading to a more secure tie with the Qohelet proverb.Footnote 5 In 1969 Shaffer followed up his observation by calling out the appearance of the same saying, but in the Epic of Gilgameš and in Akkadian, although not fully preserved, on the basis of one partly preserved line found in two manuscripts of the Standard Version (SBG), K 3252 ii 23 and Rm 853 rev. 4.Footnote 6 However, Shaffer’s reading was already recognized by Landsberger (Reference Landsberger1968). He reedited the tablet fragments of the SBG, pointed out their relationship, correctly translated the Akkadian words of the said fragments, and, while duly acknowledging Shaffer (Reference Shaffer1967), successfully reconstructed the partial Akkadian proverb on the basis of Qohelet.Footnote 7

Unsurprisingly, Landsberger was not impressed by Shaffer’s Reference Shaffer1967 discovery, given Landsberger’s reluctance to approach all things Biblical, still very much entrenched as he was, one may suspect, at the exit point of his Eigenbegrifflichkeit (Landsberger Reference Landsberger1926). Thus Landsberger (Reference Landsberger1968: 109) says: ‘Aaron Shaffer, der die sumerischen Gilgameš-Schätze der Museen von Philadelphia und London verwaltet, hat eine Art Vorläufer zu unserer Stelle [SB V 79], die schon von Kramer, JCS 1 16, 106–110, bekannt gegeben war, neu behandelt in Eretz Israel, Bd. 9 [sic! Should be ‘Bd. 8’], S. 247.’Footnote 8 He continues in a footnote (ibid. 109, n. 37) as follows: ‘Shaffer versieht seine Beobachtung mit einer pompösen Einkleidung: “Der Mesopotamische Einfluß auf Kohelet 4, 9–12.” Dies kann nicht unwidersprochen bleiben….’Footnote 9

The remaining eight lines of Landsberger’s note are devoted to show why Shaffer was wrong, concluding that the Akkadian phrase ‘… so schwer verständlich sie auch ist, zeigt keine Ähnlichkeit mit Kohelet, bis auf die – allerdings schlagende – Identität mit unserer Zeile [SBG V 79].’Footnote 10 He may have been dismissive, but nonetheless there is no doubt that Landsberger managed to reconstruct the Akkadian proverb in SBG V because of Kramer’s and, consequently, Shaffer’s reading.

Since then the reconstruction and translation offered to the half-phrase of Gilgameš (SBG V 79) have securely entered modern scholarship, appearing in all translations that I know of, whether implicitly or explicitly recognizing Qohelet’s contribution to the reading.Footnote 11 Nonetheless, a degree of caution can still be maintained if nothing beyond the single half-phrase has been proven to show any connection between the Gilgameš text and Qohelet in this locus. There is no certainty that the reading and interpretation of SBG V 89 is secure. This state of affairs exists admittedly because of the poor preservation of the Akkadian sources. But this can change following my new treatment of SBG V 75–80 which takes into consideration the Suleimaniyah Tablet, the most important source of Tablet V ever to be published. A re-edition of two western manuscripts from Emar and Ugarit also contributes to the reconstruction of the SBG lines.

On account of my reconstruction, it will be demonstrated that first, the comparison of the three-ply rope holds, and secondly, that SBG V 75–80 consists of a pericope of several proverbs on the theme of friendship. It will be shown that they are remarkably close to Qoh 4:9–12. Thus, it gives weight to Samet’s (Reference Samet2015: 381–382) suggestion that the SBG V 75–80 passage “reveals several clear parallels to the Biblical source,” although she went no further.Footnote 12 As will be demonstrated, as much as the three-ply rope of Qohelet assisted in the reconstruction of SBG V 79, its verses again can partly assist us in understanding the pericope of SBG V 75–80.

2. A Textual Reconstruction of SBG V 75–80: The Suleimaniyah Tablet and Other Sources

The so-called Suleimaniyah tablet, published a decade ago by Al-Rawi and George (Reference Al-Rawi and George2014), completely transformed our understanding of the content and structure of Tablet V of the SB version of the Epic of Gilgameš. The Neo-Babylonian tablet housed in the Suleimaniyah Museum completes much of what was missing from Tablet V, including a major episode that tells about the heroes’ arrival at the Cedar Forest and their battle with Humbaba. It includes a section of a unique description of the floral and faunal environment of the Cedar Forest (ll. 6–26) and it provides us with details about Humbaba which previously were scarcely understood (Al-Rawi and George Reference Al-Rawi and George2014: 74–75). The Suleimaniyah Tablet also helps re-arrange and re-assign some of the previously known SBG manuscripts.

With a better grasp of Tablet V our view of the western manuscripts of Gilgameš also sharpens. Prior to the publication of the Suleimaniyah Tablet, George (Reference George2007a) had already correctly recognized where two fragmentary pieces, one from Ugarit the other from Emar, are to be fitted in SB V. Now with the Suleimaniyah Tablet available, this article can reaffirm his observation and specifically can offer a textual reconstruction of the poorly preserved, and hence little understood, lines 75–80 of SB V, while integrating the western manuscripts. The reconstruction is achieved by an independent reading of the Gilgameš sources, but it would be foolish to deny that it is not informed by Qoh 4:9–12. The verses from the Book of Qohelet will be given below and subsequently the Epic and Qohelet will be compared.

SBG V 75–80: A Score Edition, Text Reconstruction and Translation

Before offering a text reconstruction and translation of SBG V 75–80 a score edition presenting all testimonies is to be provided. The edition of the SBG lines follows Al-Rawi and George (Reference Al-Rawi and George2014) and the eBL (George Reference George2022); the Ugarit and Emar mss follow George (Reference George2007a). The new readings are given in bold type. It is good to recall that the western manuscripts of Gilgameš are very poorly understood because of their poor state of preservation and inconsistent line division among the verses. We should also note that presently a collation of these sources is impossible.

To set SBG V 75–80 in context of the narrative, we start with Enkidu’s address to Gilgameš (SBG V 73–74), after the heroes enter the Cedar Forest and are about to face Humbaba. The SBG mss will be followed by two manuscripts – one from Ugarit and the other from Emar.

Sigla

SBG V

Ugarit

Emar

Textual Comments

SBG V

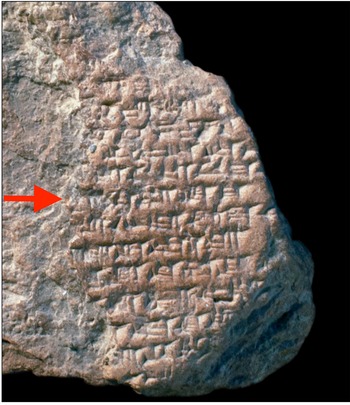

l. 76 NinNA1a ii 21: George (Reference George2022 apud eBL) reads, as in his 2003 edition, lu-ba-ra-ta-ma, ‘garments’, but this is far from certain, because the signs are barely visible. In his translation of the Epic Foster (Reference Foster2001: 73) apparently reads here ubarātu (!), with initial ú, because he offers us ‘strangers (?).’ The Ugarit manuscript, however, has a clear da-ra-ta-mi. Above is an enlarged photo of the line on the Nineveh tablet (fig. 1), K 3252+ rev. ii. We see the end of a ‘lu’ sign and a damaged sign, followed by ‘ra’, ‘tu’ and ‘ma’.

Fig. 1. K. 3252+ rev. ii 76 = P273209 = https://www.ebl.lmu.de/fragmentarium/K.3252

Perhaps we should maintain George’s reading but parse the signs differently: lu ba-ra-tu-ma → *bārâtu, adj. fem. pl., *they will be in good repair’ ← bâru, ‘to be in good health, good repair’. The form (adj. fem. pl.; see below) and sense fit with the whole pericope as with the Ugarit locus, but the reading remains difficult, because it is unattested. It is possible we are looking at a textual corruption so one needs another source to verify the reading. Note that in SBG mss, one can find the writing lu-ú as well as lu.

2-t[a …] = šitta, ‘two’ (fem.), here and passim. Compare, e.g., šitta ubānātiya, ‘my two fingers’ (OB divination), and ana šitta išāt[ātim], ‘for two fire sign[als]’ (Mari); see CAD/Š3: 34b. Throughout, the feminine form šitta, and not the masculine form šina, is employed to designate the friendship of two. Thus, it is to be thought of the numeral ‘two’, but not ‘two’ as an attribute, as in ‘two boys.’ For the sake of comparison one can think of the English proverb, ‘Two’s company, three’s a crowd’. The numerals are treated as a collective substantivized attribute. The numbers agree with the fem.pl. adjectival forms we will meet throughout the pericope.

l. 77: All mss incl. Emar read mušḫalṣītum (← neḫelṣû, ‘to slip, glide’) which means ‘that which causes one to slip’, leading George (Reference George2003: 330) to translate the word as ‘glacis’, and the CAD M/2: 269 to give us ‘slippery ground’. Perhaps given the context of two travellers on the road it is better to translate simply mušḫalṣītum as ‘slippery slope’, as much as dannatum can mean ‘danger’, ‘difficulty’ alongside the concrete ‘fortress’.

After mušḫalṣītumma BabNB1 vi 1. and NinNA1a ii 22 have u [l-, which seems to be the beginning of a verb; consider u [ltēzib], ‘he will have been [saved]’; cf. UgaMB2b, 4’. If this is accepted it means that the formulation is somewhat different from EmrMBI 7′; see below.

BabNB1 vi 1: George (Reference George2022 apud eBL) reads 2 m[u- …], following Lambert’s copy; see n. 6. A mu-participle describing the two friends is the obvious reconstruction, but which verbal form was used remains unknown; cf. EmrMBI 7′ and UgaMB2b 4′.

l. 78: BabNB1 vi 2 and NinNA1a ii 23: Read by George as 2-ta taš-ka-a-ti and [ši]t-⸢ta⸣ taš-ka-a-ta for šittā takšâti/ takšâta and translated as ‘two triplets’. Note that apart from here the word taškâti is found only once as a variant for takšu, pl. takšâtu; see CAD T: 88–89. However, the sense is compelling when we translate the phrase as ‘two are in fact like three.’ The word takaš is reconstructed in UgaMB2b, 5′; see below. This means that George’s reading is no doubt correct.

l. 79: All three sources include the verse of the three-ply rope as a metaphor for a bond of everlasting friendship.

l. 80: On the basis of the Ugarit ms, the proverb lacks a predicate and stands as it is, with the predicate implied. See below under Text Reconstruction.

Ugarit

l. 2′: Instead of ku-ú read lu ! -ú which is probably followed by š [ i-(it)-ta. The partial ‘ši’ sign is well enough preserved to ensure the reading. George (Reference George2007a) correctly identified the Ugarit fragment and its place in the Epic, while improving Arnaud’s (Reference Arnaud2007) edition.

l. 3′: Read with the copy [lu]-⸢ ú ⸣ da-ra-ta-mi. The form is reconstructed as dārâtu, a fem. pl. adj. of darû, ‘to be everlasting’. Compare above SBG V 76, *bārâtu, adj. fem. pl., *they will be in good repair’.

The sequence ša-aḫ-⸢DU⸣-⸢ta⸣ was understood by George (Reference George2007a: 249) as ša-aḫ-ṭú-ta, ‘taken off’ ← šaḫāṭu, which fits with his reading of the previous word in the Ugarit ms., as ⸢lu⸣-⸢ba !⸣-ra-ta-mi, although it is not accepted here, sic: ‘a pair of garments taken off’. At any rate having the numeral šitta after a noun is rather difficult, although not impossible. The -mi particle also suggests a shift to a new sentence. Therefore, we suggest the form ša-aḫ-⸢tù⸣-⸢ta⸣, to be a corrupt metathesised form of *šaḫtātu, a fem. pl. adj. of šaḫtu, ‘fearful, afraid’, from the verb šaḫātu (B), ‘to become afraid, to fear’; cf. CAD/Š1: 86ff. and 101, sub šaḫtu, ‘reverent’, in the meaning of fearful (of the gods).

l. 4′: The writing mu-na-an-du is difficult. It is to be taken as a N participle of the verb nadû, ‘to throw, cast’, here as a predicate, i.e., a m. pl.(?) stative with nasalization. We tentatively reconstruct: munnadû → *munaddû → *munandû. The translation is ‘(ones who are) rejected, abandoned, fallen.’ Another option is munaṭṭû, ‘beaters, sluggers’, a D participle of verb naṭû, ‘to hit, to beat’.

The form ul-da-⸢x⸣ cannot be reconstructed, but it is taken as a Middle Babylonian Š or D stem verb matching its subject, which is kabarma.

l. 5′: The signs on the tablet read DA BI; George (Reference George2022 apud eBL) suggests ṭa-bi for stative ṭāb, ‘(is) good’. I suggest, however, to read tá-kaš → takaš, takšu, ‘three-times, triplets’; see CAD T: 88 and above, the commentary on SBG V 78. The form stands in the construct state, as such, takaš TIR×TIR (ninni5), ‘three-ply rope’.

As George (Reference George2007a: 249) noted, the continutation of this line corresponds to SBG V 79, although what is written is not as corrupt as he thought. The logogram TIR×TIR (ninni5) can indeed mean ‘rush, reed’, as George translates the word. However, it can also be found to mean ‘twine’ (CAD A/2: 447, under ašlu B), so there is no contradiction of understanding here ninni5 as ‘rope’ and not as ‘cane-reed’. So takaš ninni5, is followed by an apposition (or gloss) aš-lu ša-lu-ul-tum for ašlu šaluštum ‘three-plyed rope’. This seals the argument that ninni5 is indeed ‘rope’ and what we are looking at is basically the same line as SBG V 79.

The next word is difficult. I suggest here ḫur-ru-ú [ ṣ ?] (úṣ = uš) → ḫurruṣ, ‘cut off’ from the verb ḫarāṣu, ‘to cut off, etc.’

l. 6′: The word mu-ra-nu-ša, ‘her puppies’ proves that the proverb in SBG V 80 was included in the Ugarit version, bringing the two versions even closer. Note the fem. 3rd sg. suffix -ša. One wonders if the she-dog was marked in any way in the SBG version (the word is broken). In all three copies of SBG V 80, the gender and attribute (dannu) of the dog are non-marked, i.e. ‘male’ and not ‘female’ (dannatu), so in SBG V 80 one assumes 2 mīrā[nūšu], ‘[its] puppies’. Cf. SBG V 61, where the lioness deprived of her cubs is marked as female, sic: neš-ti , ‘lioness’.

After this saying the passage ends with Enkidu directly addressing his friend (6’-7’: e-nen-na a-na ib-ri-ia). This is the case also in SBG V 81ff., as Enkidu turns to addresse his friend directly and the set of proverbs ends.

Emar

l. 5′: Read en-ša-me-e → enšāme, fem. pl. stative of enšu, ‘weak, poor’ + enclitic particle -me. Cf. SBG V 76 ma-ku-ma, ‘he is/they are lacking, poor’. As with the Ugarit ms, George (2003: 329; Reference George2007a: 249) correctly placed the Emar fragment and greatly improved the reading of previous editions and translations. The Emar fragment is included in Tournay and Shaffer (Reference Tournay and Shaffer1994: 118–119), but mistranslated.

l. 6′: George’s (Reference George2003: 330) suggestion that ša-aḫ-na is from the verb šaḫānu ‘to be warm’ is without doubt correct. The form is fem. pl stative šaḫnā ‘are warming, keeping warm’ agreeing with šitta. Incidentally, the Targum uses the same verb when translating the saying in Qoh 4:11, sic: wa-šaḥin, ‘they (the two friends) will be warm.’ See below.

A textual reconstruction and translation of the passage can now be given. Note that what is offered is partly guesswork, because it is difficult to reconcile between the very fragmentary manuscripts.

Before we move to compare SBG V 75–80 and Qoh 4, it is worthwhile to point out that as fragmentary as the Akkadian sources are, one can still conclude that the Emar and Ugarit manuscripts are not that distant from SBG V. Having mušḫalṣītumma 2-t[a in the Emar manuscript and basically two proverbs in the Ugarit fragment (ll. 5′ and 6′) shared with SBG V demonstrates their closeness. Hence, there is a place to reiterate George’s claim (Reference George2007a: 253–254) that the Ugarit manuscripts perserve a Middle Babylonian version of the Epic of Gilgameš. In light of the reconstruction we have offered, George’s (ibid.) suggestion that “[p]erhaps the Gilgameš tablets from Emar are witness to the same [i.e. Middle Babylonian] version of the poem” is most likely to be held as affirmative.

3. The Comparison between SBG V 75–80 and Qoh 4:9–12

After the reconstruction of SBG V 75–80, the four verses from Qoh 4, which are to be considered parallel, are reproduced here.

As noted by the many commentaries on the Book of Qohelet, Qoh 4:9–12 is a pericope introduced by a general observation (v. 9a) which is followed by four short exempla (vv. 9b–12a) meant to demonstrate the benefits of friendship between two comrades probably involved in a business trip. Brought in to clinch the argument, v. 12b is a proverb utilizing the threefold cord metaphor.Footnote 13

Why are two better than one (v. 9a)? To begin with, acting together will ensure they will make bigger profit (v. 9b). Presumably when on a journey, the dangers from falls into a ravine or a pit (v. 10a) can be more easily overcome when you have someone to assist you (v. 10b). And when outside on a cold night (v. 11a), how better to warm up than one against the other (v. 11b)? Being robbed of your wares or money while on a business trip – often reported in ancient Near Eastern sources – is one of the hazards of the journey (v. 12a). However, two against the attacker stand a better chance. To conclude (v. 12b): Friendship is as strong as a three-ply cord that is not easily snapped.

It is evident how similar the verses of the Epic of Gilgameš and Qohelet are. This calls for a closer examination and detailed comparison. However, there are two issues to consider before going into details. First the structure and grammar of the two sources are to be treated.

It is obvious that the two pericopes deal with the same topic, which is the worthiness of friendship, an apt theme for the Epic of Gilgameš, although a strange one for Qohelet, who overall is dismissive of practical or positive wisdom, that is to say, wisdom meant improving upon one’s circumstances.Footnote 14 Both the Epic and Qohelet open with a general statement, which is then developed. Friendship is to be preferred to a solitary life. The theme of friendship is well-known in ancient Near Eastern wisdom literature, but such a contrast as seen in both sources between single and couple, which are eventually are compared to three, is unknown to me.Footnote 15

The Akkadian proverbs advance in gradation, from one (ištēn), to two (šīna or šitta), and finally trice (takšu or taškâtu and šušlušu). Gradation in the Hebrew Bible, including Qohelet, is well-recognized and needs no further elaboration. Suffice it to note the gradation in the Qohelet pericope is from one, to two, to three.Footnote 16 The Qohelet verses end with the three-ply rope, but as its concluding line the Gilgameš passage returns to one and two – a dog and two pups.Footnote 17

Then there is grammar. The Akkadian shows verbless predicative constructions (adj. / participles as statives, i.e. as predicates) opening with lū and contrasted with the enclitic -ma, which are to be taken as assertions or rhetorical questions. The style is terse and truncated.Footnote 18 In Emar and Ugarit, we also have the enclitic -mi or -me, typical of the period.

The Biblical Hebrew of Qohelet uses strings of ki-’im, ki, ‘as if, if’ and i’lu, ‘when’ (or ‘is it not?’, as understood by some commentators), to open the phrases and the contrastive waw or resultative waw to join between the members of the verses. Additional research is required but at this point it should suffice to say that in the two sources the discourse is marked as a ‘proverb’, which naturally incline towards wisdom compositions.

We come now to the content of the two passages and juxtapose SBG V 75–80 to Qoh 4:9–12.

Qoh 4:9a, ‘Two are better than one’, uses the formula ‘better than’ (-טוב מ), which is well-known in the book.Footnote 19 The Akkadian proverb (75) repeats each constituent to form a contrast, ‘One is one, but two are two’. The meaning is the same in both the Epic and Qohelet.

Qoh 4:9b, ‘Because they have a profit for their toil’, is reflected in the Akkadian verse (76a) somewhat differently: ‘[One – ] what can he gain? Two, however [ … ].’ The verb epēšu is used in the sense of ‘to make (a profit)’; CAD E: 230.

The question or assertion that two can be poor or wanting (76a) is not reflected in Qohelet. As per our reconstruction, ‘But (the two) are everlasting and although the two may be frightened …’ (76b) also does not seem to find a parallel with Qohelet.

The placement of the next line ‘they will be warm’ (76c), partly preserved and only in the Emar ms, is not certain. Regardless of the sequence of lines, it parallels Qoh 4:11: ‘Again – if two lie together, they are warm together. How can one be warm alone?’ Is the proverb an allusion to what some claim, that Gilgameš and Enkidu were more than just buddies in Babylonia?Footnote 20 This is hardly likely, since the words are spoken as gnomic wisdom, serving to boost Enkidu’s and Gilgameš’s fighting spirit as the two are about to encounter Humbaba. However, two men warming against each other certainly caused unease for the ancient (and modern) commentators of Qohelet, especially when they are said to ‘lie down’ and when the verb ‘to warm’ can be used as a euphemism for intercourse. The Targum explains that Qoh 4:11, lest one be confused, refers not to two buddies but to a man and his wife warming each another: ‘Also if two sleep together – a man and his wife (gever weattiya), they will be warm in the winter. How can a single person be warm?’Footnote 21

The next line of the Akkadian (77) is very difficult to reconstruct, and admittedly a recourse must be made to Qoh 4:12 to even begin to understand what is going on. On the basis of the Emar ms, it starts as lū mušḫalṣītumma šitta …, ‘Should there be a slippery slope (on the road), two (will help each other) (77a). The parallel to the causative Š participle mušḫalṣītumma, lit. ‘something which causes one to fall’, is Qoh 4:12a wa-yatqifo, ‘And if one will attack one of the two’, with t.q.f in the causative Hiphil stem.Footnote 22 Qoh 4:12b continues with ‘the two still can withstand him (the attacker)’, with ‘two’ corresponding to -ma šitta, ‘but the two’ (77a), after which the Emar tablet breaks. The SBG mss are also broken at this point, and may have been formulated somewhat differently, but in all probability the sense was the same.

There now comes another saying, perhaps in the same line (77b), if our placement is correct, reading lū munnadû lū kabarma ul-da[- …], ‘even if they have fallen, the stronger one will cause (the other one to get up).’ This is parallel with Qoh 4:10, ‘For if they fall, one will lift up his fellow.’ There exists a possibility that Ugarit munnadû replaces the SBG and Emar mušḫalṣītumma, although note that the Ugarit saying is differently formulated (without šitta as the following sentence), leading one to suspect it is an additional saying, which is not preserved in the other testimonies. If we read the Ugarit form as *munaṭṭû, ‘beaters, sluggers’, it may be parallel with Qoh. 4:12a, ‘If one is attacked’, lit. ‘If somebody attacks one?’

The next saying ‘two are as threefold’ (78) is not found in Qohelet, but it fittingly introduces the proverb about the three-ply rope (79), which, as has been shown, parallels Qoh 4:12.

The last saying in the Epic is ‘a single dog is mighty enough. But his two pups?’ (80). The implication is that two are mightier than one, even if younger. One can speculate that since the Hebrew Bible has nothing positive to say about dogs the proverb was rejected. For Mesopotamian eyes at least, the image of two puppies playing with each other, and when grown-up, of two dogs roaming around in search of food were compelling metaphors for a strong bond of friendship.

In sum, the Epic of Gilgameš and Qohelet share the following proverbs, roughly paraphrased: two are better than one (SBG V 75/Qoh 4:9a), there is profit in friendship (SBG V 76a/Qoh 4:9b), two can warm each other on the road (SBG V 76c/Qoh 4:11), in peril during a journey one can help the other (SBG V 77a/Qoh 4:12a), if the two fall, one can lift up the other (SBG V 77b/Qoh. 4:10), and the three-ply rope cannot be easily snapped or cut (SBG V 79/Qoh 4:12). In sum, there are six shared sayings in both pericopes.

4. The Epic of Gilgameš and the Book of Qohelet

There may not be a complete agreement between the textual reconstruction offered for SBG V 75–79 and its subsequent comparison to Qoh 4. Nonetheless, an overall assessment can permit us to state confidently that the two texts are very close, at times parallel. The comparison reaffirms what has already been demonstrated about the ties of the Epic and the Book of Qohelet and invites one to briefly discuss the topic, without however entering a full-length presentation and discussion.Footnote 23

How is one to explain the relationship between the two works which are separated from one another in time of composition, geography, and language. Two basic approaches can be imagined.

One approach is to claim an indirect contact between Gilgameš and the Book of Qohelet, perhaps by an intermediary in the form of an Aramaic Gilgameš.Footnote 24 This scenario is possible, but it involves supposing that someone actively translated one composition, as well-known as it may have been, into another language. A transmission and subsequent reception of texts being translated as far as we can understand happened in the context of cuneiform scribal schools outside of Mesopotamia, often at Hattuša, where Hittite and Hurrian translations of Mesopotamian literature of all kinds were found. Scribal schools were common in the second half of the 2nd millennium, but after the fall of the empires, cuneiform retreated to its core heartland and became largely confined to Mesopotamia. There it was used, as it had been done for centuries, to write Akkadian and Sumerian, which but for rare cases was the only language ever translated into Akkadian.

The other side of the coin is that so far, no cuneiform work has been demonstrated to have been translated into other languages, such as Aramaic or Greek.Footnote 25 No doubt one can see through the dim light of the ages a degree of transmission, but whether this was achieved by a written translation of a given text is not known.

This leads us to examine another approach that looks at the wider context of genre and the transmission of wisdom.Footnote 26 Although The Epic of Gilgameš is not a wisdom composition, it became a piece that was equally adaptive to wisdom themes, as George (Reference George, Azize and Weeks2007b) has argued.Footnote 27 Siduri’s speech and, in the SB version, Utnapištim’s words of wisdom are prime examples, but so are the many proverbs interspersed through the Epic which are usually delivered by both heroes to one another.Footnote 28 The heroes’ discourse is to be seen as a gathering of sayings chosen to heighten emotions within the narrative structure. The very same theme of friendship which Enkidu develops in SBG V 75–80 is expressed earlier on in SBG V 45–50 by a different set of proverbs, although this time articulated by Gilgameš.

It can be said, with all due caution, that the proverbs or sayings in the Epic were not, or at least not all, composed by its author, but rather wisely strung from other sources, possibly oral. That such a composition technique was operated can be gathered from other wisdom compositions. Recent studies of Babylonian wisdom literature have revealed an interconnectivity between Mesopotamian wisdom texts under which lies a patch-work composition technique extensively borrowing and readapting existing materials. The picture is still very fragmentary, but this patch-work composition technique can be detected among several key wisdom works, such as the Ballad of Early Rulers, šimā milka, and several disputation poems.Footnote 29 This inter-borrowing or interconnectivity happens because having no strict narrative or plotline wisdom works lend themselves to stretch and change.

Turning to Qohelet and its relationship with the Epic of Gilgameš, we can say that Qohelet is a wisdom book and that it is because of its genre, like other works of wisdom, that it too can collect from other sources. Thus, it can be argued that it is not a fully independent work, but rather that it incorporates proverbs and sayings from without. These usually contribute to the main idea of ‘vanity’ which is of course the driving argument of the Book. However, other proverbs in the Book may seem less than an obvious fit. The theme of ‘vanity’ in Siduri’s speech fits perfectly with the ideas that Qohelet has about the meaning of life. But how is one to explain Qohelet’s compassionate defence of friendship, which, as many commentators were at loss to explain, hardly agrees with his sense of irony? It is one puzzle piece which does not fit into the larger puzzle, hence it was picked out, so I argue, from a different puzzle box altogether. Its very difference points to the Book’s adaptive technique.

The Book of Qohelet and the Epic of Gilgameš are probably not related in any direct way and I doubt that Qohelet, whoever may have been behind his persona, ever knew about Gilgameš, let alone the Epic in whatever version. What the two works shared though was a world in which wisdom, in the form of collected proverbs, travelled through time and space, easily memorized, adapted, and changed because of their universal nature and value for basically everyday life.

This article provided a reconstruction of SBG V 75–80, which was demonstrated to include a string of proverbs about the theme of friendship. In the course of the discussion, it has been shown that the Emar and Ugarit manuscripts preserved a version which can be called Middle Babylonian and which, with all the problems of transmission, was a precursor of the SBG version. It was also demonstrated that as the history of scholarship has taught us the Book of Qohelet preserves wisdom materials which are found in the Epic of Gilgameš and that they can assist us in reconstructing the Akkadian text where broken. Lastly, a short discussion about Qohelet and the Epic sought to examine the nature of the ties between the two works. It was suggested that rather than assume an indirect contact between the two through an intermediary translation, it is the genre of wisdom literature that permitted the transmission and reception of long-existing and widely circulating proverbs. The transmission of singular proverbs throughout the Mediterranean basin and the near East has been proven time and again.Footnote 30 However, in this article it was shown how an entire thematic set of proverbs tied to each another by the literary device of gradation served both the Epic of Gilgameš already at the end of the second millennium and the Book of Qohelet, which was put into writing many centuries later.Footnote 31