Introduction

Recent years have seen growing interest in the subject of advance healthcare directives in Ireland, due not only to the abundance of literature to suggest their usefulness in healthcare and psychiatry (Lasalvia et al. Reference Lasalvia, Patuzzo, Braun and Henderson2023), but also their recent inclusion in Irish law. Ireland’s Assisted Decision Making (Capacity) Act, 2015, which commenced in April 2023, replaced the outdated Lunacy Regulation (Ireland) Act, 1871. The new legislation describes three levels of decision-making support for individuals who require them, along with provisions for planning for future loss of decision-making capacity in the form of advance healthcare directives and enduring powers of attorney (Kelly, Reference Kelly2017).

In the 2015 Act, an advance healthcare directive is defined as ‘an advance expression made by the person, in accordance with Section 84, of his or her will and preferences concerning treatment decisions that may arise in respect of him or her if he or she subsequently lacks capacity’ (Section 82). Advance healthcare directives are a welcome inclusion in the legislation because although advance directives existed in Ireland before the 2015 Act, there were no specific laws governing them. Consequently, their implementation was not necessarily systematic (Irish Council for Bioethics, 2006).

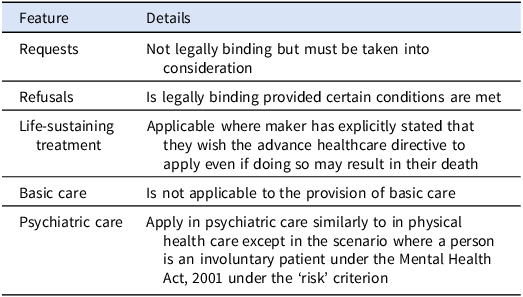

The new legislation specifies that a request for a specific treatment in an advance healthcare directive ‘is not legally binding but shall be taken into consideration’ (Section 84(3)(a)), while a refusal of treatment is generally legally binding, provided certain conditions are met, albeit with some exceptions (Kelly, Reference Kelly2017).

Additionally, ‘an advance healthcare directive is not applicable to life-sustaining treatment unless this is substantiated by a statement in the directive by the directive-maker to the effect that the directive is to apply to that treatment even if his or her life is at risk’ (Section 85(3)), and ‘is not applicable to the administration of basic care to the directive-maker’ (Section 85(4)(a)), which ‘includes (but is not limited to) warmth, shelter, oral nutrition, oral hydration and hygiene measures but does not include artificial nutrition or artificial hydration’ (Section 85(4)(b)).

Advance healthcare directives apply in psychiatric care similarly to in physical health care except in the scenario where a person is an involuntary patient under the Mental Health Act, 2001 under the ‘risk’ criterion (Section 3(1)(a)). In that situation, an advance healthcare directive pertaining to mental health care is not applicable for the duration of their involuntary status (although advance healthcare directives pertaining to physical health care remain applicable) (Kelly, Reference Kelly2017). A condensed explanation of the legislation can be found in Table 1.

Table 1. Features of Ireland’s Assisted Decision-Making (Capacity) Act, 2015 concerning advance healthcare directives

In 2023, the Decision Support Service, which was established under the 2015 Act, published a Code of Practice on Advance Healthcare Directives for Healthcare Professionals which provides a comprehensive guide for healthcare workers in fulfilling their responsibilities concerning advance healthcare directives (Decision Support Service, 2023; p5). Elaborating on the provisions of the legislation, the Code of Practice emphasises the onus on the healthcare provider to ascertain the existence of an advance directive, check its validity, and determine whether it should come into effect (Decision Support Service, 2023). It is, therefore, necessary for healthcare providers to familiarise themselves not only with the provisions of the legislation but also the Code of Practice.

Previous research indicates that service users are generally very supportive of advance healthcare directives (Thom et al. Reference Thom, O.’Brien and Tellez2015; Gergel et al. Reference Gergel, Das, Owen, Stephenson, Rifkin, Hindley, Dawson and Ruck Keene2021; Braun et al. Reference Braun, Gaillard, Vollmann, Gather and Scholten2023). It is suggested that increasing a patient’s sense of agency can help foster greater engagement in treatment and recovery, improve therapeutic relationships and potentially reduce mental health stigma (Lasalvia et al. Reference Lasalvia, Patuzzo, Braun and Henderson2023). In addition, crisis plans which include advance healthcare directives have shown promise in decreasing involuntary admissions (de Jong et al. Reference de Jong, Kamperman, Oorschot, Priebe, Bramer, van de Sande, Van Gool and Mulder2016; Bone et al. Reference Bone, McCloud, Scott, Machin, Markham, Persaud, Johnson and Lloyd-Evans2019; Molyneaux et al. Reference Molyneaux, Turner, Candy, Landau, Johnson and Lloyd-Evans2019).

Despite their usefulness, the rates of advance healthcare directive completion tend to be low. Low rates of completion of advance healthcare directives for physical health conditions have been reported in Ireland (Doolan et al. Reference Doolan, Colfer, O’Connor, Breathnach, Skehan, Lavelle, O’Leary, Reilly, Egan, Barrett, Grogan, Naidoo, Murphy, Cooley, Morris, Greally, Hennessy, Doherty and Breathnach2024) and in other countries (Blackwood et al. Reference Blackwood, Walker, Mythen, Taylor and Vindrola-Padros2019) and for mental health conditions internationally (Swanson et al. Reference Swanson, Swartz, Elbogen, Van Dorn, Ferron, Wagner, McCauley and Kim2006).

Against this background, and in the context of the commencement of Ireland’s 2015 Act, the purpose of our study is to investigate the levels of knowledge and attitudes towards advance healthcare directives among inpatient service users in Ireland.

Methodology

Setting

The study included adult inpatients in the psychiatry wards of Tallaght University Hospital, Dublin, which is one of the two main teaching hospitals of Trinity College Dublin. This psychiatry inpatient facility provides care to adults (over 18 years) with mental illness from the suburban geographical catchment area of the hospital. Service users can be admitted on voluntary basis or an involuntary basis (under Ireland’s Mental Health Act, 2001). This is a public healthcare facility (i.e., it is operated by the Health Service Executive, Ireland’s governmental public health service provider), so treatment is free at point of delivery. There are no private patients (i.e., no patients paying fees or using private health insurance). Service users are admitted following referral from community mental health teams, general practitioners (family doctors), or the hospital’s emergency department.

Participants and recruitment

For inclusion, participants had to be inpatient service users in Tallaght University Hospital, Dublin during the study period, aged 18 years or over, proficient in the English language, and have the capacity to consent to study. We adopted a pragmatic sampling method due to the challenges of conducting the study on acute hospital patients. All service users who met inclusion criteria were considered as potential participants, subject to the consent procedure outlined below. Ward nurse managers were consulted to identify service users whom they deemed were unsuitable to survey (e.g., owing to acute risk of disturbed behaviour); all other service users were invited to participate. To capture the perspectives of service users who regained decision-making capacity during their admission, a record was kept of service users who were initially deemed unsuitable for this reason; if they regained decision-making capacity during the study period, they were then interviewed with additional questions about whether their experience of lacking decision making-capacity had altered their views on advance healthcare directives.

Data collection

An adapted version of the tool used in a previous survey of experiences of and attitudes to advance decision-making among people with bipolar disorder in the United Kingdom was used (Hindley et al. Reference Hindley, Stephenson, Ruck Keene, Rifkin, Gergel and Owen2019) (Appendix A). This tool was previously piloted, validated, and revised with input from people with lived experience of mental illness and researchers. The tool was slightly adjusted for the present study in order to enquire about advance healthcare directives specifically rather than advance care planning in general (and thus align with Irish legislation). We piloted the tool on five patients and made minor adjustments in terms of readability and layout. The tool was otherwise essentially unchanged. Data were collected by face-to-face interviews using the tool between March and August 2024.

Consent

All participants were provided with an information leaflet about the study. Written informed consent was obtained from service users who wished to participate.

Ethics

All participants provided written informed consent before participating in this study. All procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committee on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008 (World Medical Association, Reference World Medical Association2008). The authors assert that the local ethics committee determined that ethical approval for this project and publication was not required. The project was approved by the Clinical Audit and Quality Improvement Department at Tallaght University Hospital, Dublin, Ireland (submission number: 3657; project ID: 4522). Data protection legislation was adhered to and patient confidentiality was protected at all times. Data were stored on a password-protected research computer in a locked research office. Data were irrevocably anonymised and encrypted.

Statistics

We stored, analysed, and described data using IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 28). For multi-variable analysis, we performed binary logistic regression analysis. Owing to the fact that no study participant had made out an advance healthcare directive, the dependent variable was based on responses to the question: ‘If you were supported by your healthcare provider to make an advance healthcare directive, would you like to make one?’ For the purpose of analysis, responses were recoded as ‘Yes’ (i.e., ‘Yes’ or ‘Probably yes’) and ‘No’ (i.e., ‘Neither yes nor no’, ‘Probably no’, or ‘Definitely no’). Independent variables were ethnicity, gender, age, education, employment status, and prior knowledge of advance healthcare directives.

We tested the model for multicollinearity, which is when two or more variables are so closely related to each other that the model cannot reliably distinguish the independent effects of each. To test for this, we calculated a ‘tolerance value’ for each independent variable; tolerance values below 0.10 would indicate significant problems with multicollinearity (Katz, Reference Katz1999).

Our study included service users who initially lacked decision-making capacity (and therefore could not consent to participate), but later regained decision-making capacity during the study period (and agreed to participate). Owing to the fact that only five service users met these criteria, statistical analysis was not appropriate, so those results are presented in narrative fashion at the end of the Results section.

Results

Demographics

Forty-seven service users participated in the study. Fifteen (31.9%) were female; 31 (66.0%) were male, and one (2.1%) preferred not to say. Mean age was 41.8 years (standard deviation [SD]: 18.4; range: 19.0–90.0). Thirty-one service users (66.0%) were single; 11 (23.4%) were married/in a relationship; three (6.4%) were separated, and two (4.3%) widowed. Eleven service users (23.4%) were living in property they own; 11 (23.4%) living with family or friends in their own room; five (10.6%) in private rented accommodation; nine (19.1%) renting from a local authority or housing agency, and 10 (21.3%) homeless or in unstable accommodation, while one (2.1%) had another living arrangement.

Thirty-one service users (66.0%) identified as White Irish; nine (19.1%) as Other White; two (4.3%) as Black Irish; two (4.3%) as Indian; one (2.1%) as Black African; one (2.1%) as Gypsy/Romany; and one (2.1%) as ‘Other’. Forty-one service users (87.2%) had English as their first language. Eight service users (17.0%) reported having no formal educational qualifications; two (4.3%) had Junior Certificate or an equivalent qualification; 15 (31.9%) had Leaving Certificate or an equivalent qualification; 16 (34.0%) had an undergraduate diploma or degree, and six (12.8%) had a postgraduate qualification.

Fifteen service users (31.9%) were unemployed; nine (19.2%) were working; nine (19.2%) were retired; eight (17.0%) were on social welfare payments for long-term illness or disability; two (4.3%) were students, and four (8.5%) had other arrangements. Sixteen (34.0%) service users chose not to reveal their weekly household income; 22 (46.8%) had a weekly household income less than €400 and nine (19.2%) were greater than €400.

Knowledge of advance healthcare directives

Five service users (10.6%) had heard of advance healthcare directives of whom two (4.3%) had heard about them from family or friends and one (2.1%) from another healthcare professional (not including their general practitioner or hospital doctor).

Experience of advance decision making

None of the service users had ever created an advance healthcare directive, but 12 (25.5%) had either written down (n=4) or verbally told someone (n=8) what they would like to happen when they became unwell. When asked ‘if you were supported by your healthcare provider to make an advance healthcare directive, would you like to make one?’, 16 (34%) responded ‘definitely yes’; 16 (34%) ‘probably yes’; nine (19.1%) ‘neither yes nor no’; four (8.5%) ‘probably no’, and two (4.3%) ‘definitely no’.

Perspectives on advance healthcare directives: content, involvement of others, storage

Regarding who should be involved in writing an advance healthcare directive, 34 (72.3%) would involve a hospital doctor (either consultant or non-consultant); 33 (70.2%) would involve their general practitioner (family doctor); 31 (66%) family and friends; 24 (51.1%) other healthcare professionals; 20 (42.6%) a lawyer; 15 (31.9%) support groups, and one (2.1%) would involve some other person. No service user felt that they should involve nobody else in writing an advance healthcare directive.

Thirty-five service users (74.5%) said they would include requests for specific medications or other treatments in an advance healthcare directive; 28 (59.6%) would include where they want to be treated; 26 (55.3%) would include a description of the condition they would expect themselves to be in when they can no longer make decisions for themselves and need treatment; 25 (53.2%) would include where they do not want to be treated; 24 (51.1%) would include refusals of specific treatments; 24 (51.1%) would include requests for hospitalisation in certain circumstances; 23 (48.9%) would include whether their refusal of treatment is to be respected even if it results in their death, and 20 (42.6%) would include plans for discharge.

Concerning where they thought advance healthcare directives should be stored, 31 (66%) felt they should be stored in hospital notes; 31 (66%) in a centralised database accessible to healthcare professionals; 32 (68.1%) in general practice notes; 21 (44.7%) with family or friends; 18 (38.3%) on their person; nine (19.1%) with a support group; four (8.5%) somewhere else, and three (6.4%) did not know.

One service user (2.1%) was aware of the concept of the designated healthcare representative. Thirty-five service users (74.5%) thought this was a good idea; two (4.3%) did not, and ten (21.3%) were not sure.

Attitudes towards barriers to advance healthcare directives

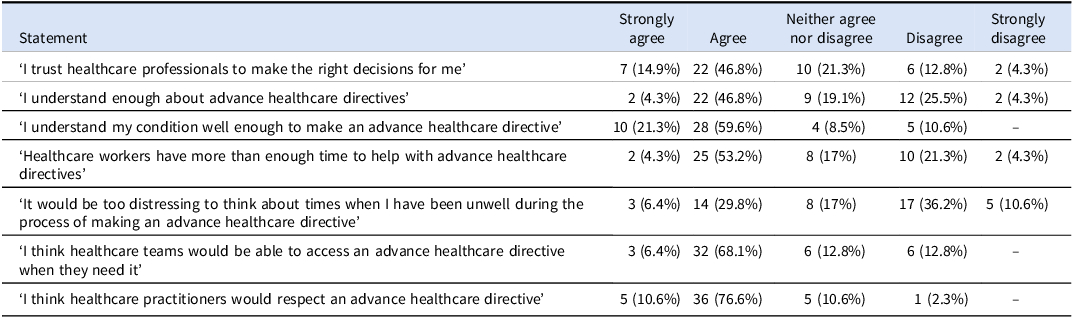

Service users were asked to what extent they agreed with several statements about advance healthcare directives and to rate their answers on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from ‘strongly agree’ to ‘strongly disagree’ (Table 2). Most service users trusted healthcare staff to make the right decisions for them, believed staff have sufficient time to help with advance healthcare directives, that staff would respect them, and that staff would be able to access the advance healthcare directive when needed to. Most service users believed that they understood their condition well enough to make an advance healthcare directive. Although majorities endorsed feeling that they understood advance healthcare directives sufficiently and did not feel it would be too distressing to think about times when they have been unwell (in the process of making an advance healthcare directive), these majorities were lower than those supporting other statements.

Table 2. Psychiatry inpatients’ attitudes towards advance healthcare directives

When asked ‘How important is it to you that you are involved in decisions about your healthcare?’, 25 service users (53.2%) responded ‘extremely important’; 15 (31.9%) ‘very important’; three (6.4%) ‘moderately important’; three (6.4%) ‘slightly important’; and one (2.1%) ‘not important at all’. Asked, ‘How important is it to you that an advance healthcare directive is legally binding’, 17 (36.2%) responded ‘extremely important’; 15 (31.9%) ‘very important’; eight (17%) ‘moderately important’; five (10.6%) ‘slightly important’; and two (4.3%) ‘not important at all’. Twenty-four (51.1%) service users said they would prefer an advance care plan that wasn’t legally binding but would still include their will and preferences; 23 (48.9%) would not.

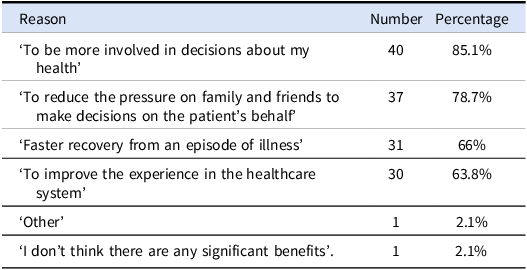

Asked about the most important reasons to make an advance healthcare directive, the majority of service users endorsed being more involved in decisions about their health, reducing the pressure on family and friends, faster recovery from an episode of illness, and improving their experience in the healthcare system (Table 3). When asked ‘How easy do you think it is to make an advance health care directive?’, one (2.1%) responded ‘very easy’; 12 (25.5%) ‘easy’; five (10.6%) ‘neither difficult nor easy’; nine (19.1%) ‘difficult’; two (4.3%) ‘very difficult’, and 18 (38.3%) ‘I don’t know’.

Table 3. Inpatient service users main reasons for making advance healthcare directives

When asked ‘How worried are you that you would not be able to change the contents of an advance healthcare directive even when you are well and able to make decisions for yourself ?’, 13 (27.7%) were ‘not worried at all’; 13 (27.7%) ‘slightly worried’; 11 (23.4%) ‘moderately worried’; six (12.8%) ‘very worried’, and four ‘extremely worried’.

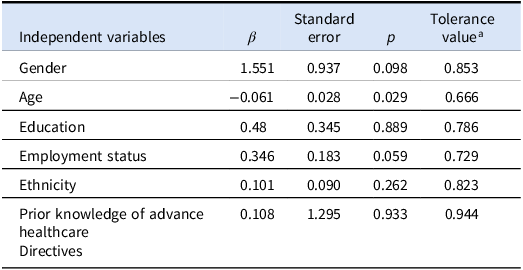

Multivariable binary logistic regression analysis

On binary regression analysis, future willingness to make an advance healthcare directive was significantly associated with younger age (Table 4). This model was statistically significant and accounted for 29.7% of the variance. All tolerance values were > 0.25 indicating no problems with multicollinearity.

Table 4. Binary regression analysis of correlates of willingness to make advance healthcare directive if supported in the future among inpatient service users

This table presents a binary regression analysis of willingness to make an advance healthcare directive if supported in the future as the dependent variable; r 2 = 29.7%; p < .015.

a All tolerance values were >0.10 indicating no problems with multicollinearity.

Participants who initially lacked decision-making capacity but later regained decision-making capacity

We wanted to capture the views of those who sometimes lack decision-making capacity as they are perhaps the most important group to target when discussing advance healthcare directives. However, due to ethical restrictions, we were unable to survey this group. Instead, we noted individuals who we were advised not to survey by the ward managers due to capacity concerns. We interviewed them later in their admission if they regained that decision-making capacity. Most of the patients in this group were involuntary and tended to be rapidly discharged once they regained capacity and were made voluntary, therefore we were only able to capture five patients in this subgroup. Since only five service users met these criteria, statistical analysis was not appropriate, so these results are presented in narrative form only.

Two of these five service users were female; three were white Irish, and four were single (not in a relationship). None had heard of advance healthcare directives, but two had previously verbally expressed what they would like to happen to them when they became unwell, and another one had done so in writing. Four would either probably or definitely like to make an advance healthcare directive if they were supported in doing so.

These service users were asked, ‘How has your experience in the hospital changed your viewpoint on advance healthcare directives?’ One service users said that advance healthcare directives ‘offer more opportunities to express your difficulties’ because in hospital ‘there is not enough time to express your experiences. I think they would give you more time to express your difficulties. In hospital you don’t have enough time to express your difficulties’. Another service users said, that ‘because I was involuntary, it’s really about patient autonomy. I didn’t feel that as an involuntary patient, my autonomy was respected’. All five of these service users said they had more positive views on advance healthcare directives from their current admission.

Discussion

Key results

Just over one in ten (10.6%) psychiatry service users had heard of advance healthcare directives. None had ever created an advance healthcare directive, but over a quarter (25.5%) had either written down or verbally told someone what they would like to happen when they became unwell. When asked, ‘if you were supported by your healthcare provider to make an advance healthcare directive, would you like to make one?’, over two-thirds responded either ‘definitely yes’ (34%) or ‘probably yes’ (34%). On multi-variable testing, future willingness to make an advance healthcare directive was significantly associated with younger age but not with ethnicity, gender, education, employment status, or prior knowledge of advance healthcare directives. All respondents would involve someone else in making an advance healthcare directive; e.g., hospital doctor (72%), general practitioner (family doctor) (70%) or family and friends (66%). There was a high level of confidence that healthcare practitioners would respect an advance healthcare directive (87%).

Interpretation

Our headline findings are consistent with those of a 2024 study of Irish oncology patients which found that none had made an advance healthcare directive but a majority (87%) would consider doing so (Doolan et al. Reference Doolan, Colfer, O’Connor, Breathnach, Skehan, Lavelle, O’Leary, Reilly, Egan, Barrett, Grogan, Naidoo, Murphy, Cooley, Morris, Greally, Hennessy, Doherty and Breathnach2024). Similarly, a 2023 systematic review of mental health service users’ views on psychiatric advance directives demonstrated that more than 60% of service users support them (Braun et al. Reference Braun, Gaillard, Vollmann, Gather and Scholten2023). Two Irish studies were included in that review and both demonstrated substantial interest in advance healthcare directives among psychiatry patient cohorts (O’Donoghue et al. Reference O’Donoghue, Lyne, Hill, O’Rourke, Daly and Feeney2010; Morrissey, Reference Morrissey2015).

In one of those studies, only 27% of service users said they were familiar with and understood advance healthcare directives (Morrissey, Reference Morrissey2015). That study was conducted before Ireland’s new system of advance healthcare directives came into operation, but our study, conducted after commencement in 2023, shows that it remains the case that very few service users are aware of advance healthcare directives (10.6%), despite the new system. This need not necessarily be the case: one survey of service users and clinicians in New Zealand found that 84% of service-user respondents had heard of advance directives and 47% had been involved in developing or using one (Thom et al. Reference Thom, O.’Brien and Tellez2015).

Similarly, in Hindley et al’s study from which we adapted our survey tool, high levels of interest in advance care planning among respondents were demonstrated; most would prefer a non-legally binding advance care plan and interest in advance decision-making was associated with younger age but not with education or gender (Hindley et al. Reference Hindley, Stephenson, Ruck Keene, Rifkin, Gergel and Owen2019). In that study, only 50% of the respondents who had engaged in advance decision-making reported feeling that their plans were respected either highly or completely. This is perhaps at odds with majorities in our study believing that healthcare practitioners would respect advance healthcare directives. The implied high confidence around implementation is not necessarily supported by evidence, which has demonstrated that numerous obstacles interfere with the implementation of advance directives in psychiatric care (Zelle et al. Reference Zelle, Kemp and Bonnie2015). At present there is a real risk of disappointing service users whose documents aren’t implemented, and in doing so undermining trust in the system.

Regarding the notable number of service users, nearly 50% who expressed a wish for their decisions to be respected even if it results in their death, we hypothesise that many of these service users had physical health outcomes in mind as the use of advance healthcare directives in end of life care remains more well-established (Olsen, Reference Olsen2016). However, their use in suicidal behaviours is a source of anxiety for clinicians and is worth considering in this context. The existing evidence in this area is largely based on cases and is indicative that this kind of presentation is uncommon. A 2019 systematic review of management of cases where advance decision-making was used prior to suicidal acts revealed variations in views and rationale for acting in these situations (Nowland et al. Reference Nowland, Steeg, Quinlivan, Cooper, Huxtable, Hawton, Gunnell, Allen, Mackway-Jones and Kapur2019). Given the clinical and ethical implications here, further research is indicated in this area to explore clinical and service user perspectives on this important topic.

Generalisability

This is the first study of Irish service users knowledge of and attitudes towards advance healthcare directives since the commencement of Ireland’s Assisted Decision Making (Capacity) Act, 2015 in 2023. The present study is, therefore, a timely, relevant examination of an important topic. The generalisability of our findings, is, however, limited by the fact that our study includes only inpatients, rather than outpatients. Future research could usefully focus on service users in the community who might not be in the midst of an acute crisis and might be therefore in a better position to consider the merits of advance healthcare directives.

Limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine this topic in a cohort of service users who initially lacked decision-making capacity (and therefore could not consent to participate), but later regained decision-making capacity during the study period (and agreed to participate). While this is a unique aspect of the present study, it is limited by the fact that only five service users could be included in this category, owing to both the need to wait until they regained decision-making capacity and the high turnover of service users in acute inpatient psychiatry. Nevertheless, these results are presented in a narrative fashion in our paper, if only to indicate the potential value of future research involving this difficult-to-research group.

Conclusions

There are high levels of interest in advance healthcare directives, but low levels of knowledge and use, among service users in Ireland. Importantly, knowledge has not increased since the commencement of Ireland’s Assisted Decision-Making (Capacity) Act, 2015 in 2023; if anything, awareness has fallen. Nevertheless, some of the positive findings from our work include the facts that, once they became aware of them, all respondents would involve someone else in making an advance healthcare directive (e.g., doctor, family, friends) and there is a high level of confidence that healthcare practitioners would respect advance healthcare directives. The latter finding necessitates the need for greater implementation efforts so as not to undermine the trust of service users.

Overseas the Advance Choice Documents Implementation project at Kings College London is specifically focussing on implementationFootnote 1 . They have an education programme of simulation training sessions for healthcare professionals and have funding to train independent facilitators to support service users in making documents. Similar efforts locally are indicated to generate momentum in Ireland.

Similarly to some other jurisdictions (Thom et al. Reference Thom, O.’Brien and Tellez2015), the laws governing advance healthcare directives in Ireland apply to both physical and mental health treatments albeit with some exceptions in mental health. However, in contrast to England and Wales where they are included in the Mental Health Act 1983: Code of Practice (Department of Health, 2015) or New Zealand where the Mental Health Commission supports them, advance healthcare directives are not strongly promoted within Irish mental health services. This fact may offer some explanation to the lag in momentum in their implementation in psychiatric care in Ireland.

Previous research in other jurisdictions has shown that legislative reform in this area is insufficient in generating interest and increasing use of advance healthcare directives in clinical practice (Blackwood et al. Reference Blackwood, Walker, Mythen, Taylor and Vindrola-Padros2019; Swanson et al. Reference Swanson, Swartz, Elbogen, Van Dorn, Ferron, Wagner, McCauley and Kim2006). More is needed. In New Zealand, in addition to the inclusion of advance directives in legislation, the New Zealand Mental Health Commission strongly advocated for their use in mental health services (Thom et al. Reference Thom, O.’Brien and Tellez2015). This is consistent with other evidence that educational and facilitation programmes for advance healthcare directives enhance uptake (Swanson et al. Reference Swanson, Swartz, Elbogen, Van Dorn, Ferron, Wagner, McCauley and Kim2006; Sudore et al. Reference Sudore, Schillinger, Katen, Shi, Boscardin, Osua and Barnes2018).

The www.advancechoices.org video website is a recent example of one such initiative. This website is designed for an international audience and offers a straightforward, freely available set of instructional videos including insights on what advance healthcare directives are, how they can help, and how to create one (Redahan et al. Reference Redahan, Kelly and Gergel2024). Another useful resource is the National Resource Centre on Psychiatric Advance Directives websiteFootnote 2 .

Further research is indicated which may include qualitative interviews of focus groups from similar cohorts of service users which could usefully look at refusals of all treatments which is a source of anxiety for clinicians. Additionally, we are conducting a mirror survey of staff from within the same inpatient setting in order to compare staff attitudes. Our findings indicate a need for similar initiatives and educational resources to those described above to be developed locally to increase public awareness of advance healthcare directives in Ireland. Such initiatives are needed to increase understanding of advance healthcare directives and facilitate advocacy for their use by clinicians. Such efforts could usefully focus especially on the appropriate use of advance directives in psychiatric care and thus seek to bridge the gaps between evidence of benefit, legislative reform, and practical use in mental healthcare.

Acknowledgements

The authors are very grateful to the editor and reviewers for their comments and suggestions.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests

None.

Ethical standard

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committee on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. The authors assert that the local ethics committee has determined that ethical approval for this project and publication was not required by their local ethics committee. The project was approved by the Clinical Audit and Quality Improvement Department at Tallaght University Hospital, Dublin, Ireland (submission number: 3657; project ID: 4522).